Abstract

A stem cell-mediated bioengineered tooth root (bio-root) has proven to be a prospective tool for the treatment of tooth loss. As shown in our previous studies, dental follicle cells (DFCs) are suitable seeding cells for the construction of bio-roots. However, the DFCs which can only be obtained from unerupted tooth germ are restricted. Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHEDs), which are harvested much more easily through a minimally invasive procedure, may be used as an alternative seeding cell. In this case, we compared the odontogenic characteristics of DFCs and SHEDs in bio-root regeneration.

Methods: The biological characteristics of SHEDs and DFCs were determined in vitro. The cells were then induced to secrete abundant extracellular matrix (ECM) and form macroscopic cell sheets. We combined the cell sheets with treated dentin matrix (TDM) for subcutaneous transplantation into nude mice and orthotopic jaw bone implantation in Sprague-Dawley rats to further verify their regenerative potential.

Results: DFCs exhibited a higher proliferation rate and stronger osteogenesis and adipogenesis capacities, while SHEDs displayed increased migration ability and excellent neurogenic potential. Both dental follicle cell sheets (DFCSs) and sheets of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHEDSs) expressed not only ECM proteins but also osteogenic and odontogenic proteins. Importantly, similar to DFCSs/TDM, SHEDSs/TDM also successfully achieved the in vivo regeneration of the periodontal tissues, which consist of periodontal ligament fibers, blood vessels and new born alveolar bone.

Conclusions: Both SHEDs and DFCs possessed a similar odontogenic differentiation capacity in vivo, and SHEDs were regarded as a prospective seeding cell for use in bio-root regeneration in the future.

Keywords: Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth, Dental follicle cell, Cell sheet, Treated dentin matrix, Bio-root, Periodontal regeneration

Introduction

Tooth loss, a common condition encountered in the clinic, not only affects pronunciation and mastication but also leads to a series of physiological and psychological problems. Cell-based tissue engineering techniques have achieved great progress in the field of tooth regeneration 1-5. They are a more efficient and predictable procedure due to the participation of cells in the formation of new tissues, which play an essential role in tissue engineering research 6, 7. However, the regeneration of an entire tooth has proven quite difficult. Compared to whole tooth regeneration, tooth root regeneration is proposed as a more practical and promising method for tooth restoration 8. The tooth root is a complex apparatus consisting of hard and soft tissues, including dentin, cementum and periodontium. It also plays an important role in chewing and maintaining the stability of tooth, which is the structural basis of a functional tooth. Based on this information, the bio-root was designed to simulate the anatomical structure of the natural root and to withstand the mastication pressure.

In 2005, the Morsczeck group successfully isolated dental follicle cells (DFCs) from the impacted third molar, confirming its mesenchymal source and multidifferentiation capability in vitro 9. DFCs are a type of young mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) that are present in developing periodontal tissues, which form the periodontal structures during tissue differentiation and maturation 10. According to Yokoi et al., immortalized DFCs isolated from mouse incisor tooth germs have the capacity to generate periodontal tissue in vivo 11. Additionally, as shown in our previous studies, DFCs possess eminent odontogenic potential to develop new dentin-pulp-like tissues and cementum-periodontal complexes when combined with a treated dentin matrix (TDM) scaffold in vivo 3, 12, 13. This bio-root complex was also confirmed to perform the masticatory function and maintained a stable structure for three months after crown restoration 14. In this case, DFCs are considered a suitable seeding cell for bio-root construction. Traditionally, DFCs are isolated from the unerupted dental germ of the third molar. However, during human evolution, the jawbones have decreased in size and a large number of people lack the third molar. In this case, alternative cell sources are required.

Since the isolation of dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in 2000 15, various types of seeding cells have been acquired from different dental tissues, such as periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs) 16, stem cells from apical papilla (SCAPs) 17, gingival mesenchymal stem cells (GMSCs) 18 and jaw bone mesenchymal stem cells (JBMSCs) 19. After a comparison and selection, we noticed stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHEDs). As a cell type that almost everyone possesses, SHEDs are an abundant tissue source for clinical applications. SHEDs exhibit a much higher proliferation rate than DPSCs, adult MSCs, and PDLSCs 20, 21. The unique nature of the SHEDs results from their character as immature DPSCs, and SHEDs have a cell population doubling ability that is comparable to permanent DPSCs while expressing embryonic stem cell markers 20, 22, 23. DPSC sheets were suggested to be appropriate therapies for periodontal bone and soft tissue regeneration in swine 24, which proved to be a promising cell source for periodontal regeneration. In this regard, SHEDs, which are isolated from the dental pulp of retained deciduous teeth, are much younger than DPSCs and are predicted to possess the potential to regenerate periodontal tissues. Considerable research efforts have been devoted to application of SHEDs for hard and soft tissues restoration in periodontitis. Gao et al. found that local delivery of SHEDs attributed to the induction of M2 macrophage polarization and reduction of periodontal tissue inflammation in a rat periodontitis model 23. Moreover, SHEDs exhibit tremendous angiogenesis and neurotization potential 25. Additionally, SHEDs possess high biosecurity as they are autologous and nonimmunogenic, and the harvesting procedure is noninvasive or minimally invasive, with fewer controversies associated with morality and ethics 26, 27, 28. Accordingly, all the aforementioned advantages make SHEDs an appropriate candidate for bio-root regeneration.

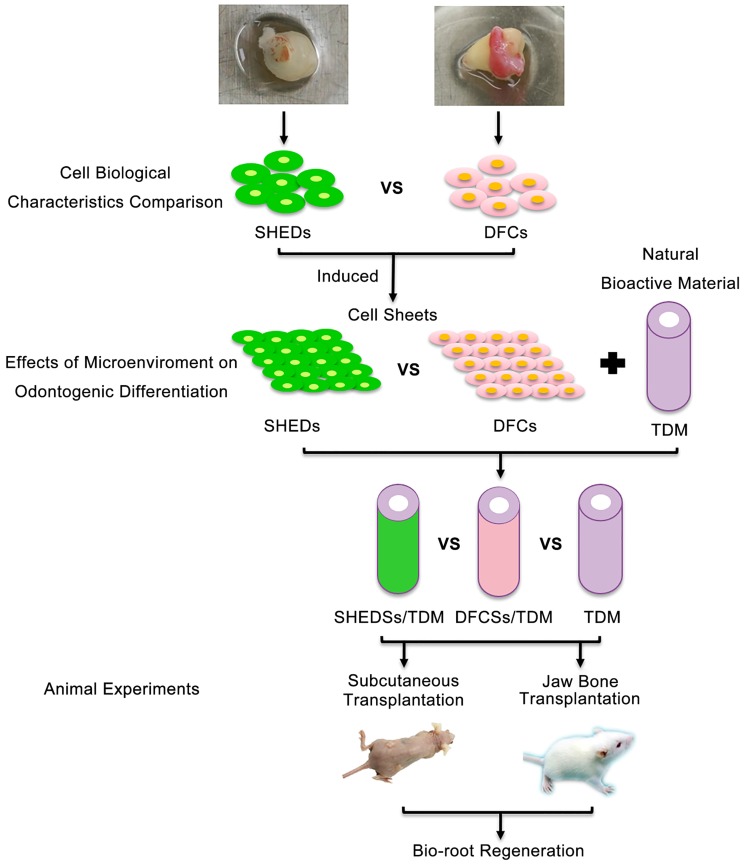

Thus, in this study, we explored the potential of SHEDs in bio-root regeneration and used DFCs as a control group to compare the biological characteristics of DFCs and SHEDs in vitro. Then, their odontogenic differentiation abilities were analyzed under the same inductive microenvironment of extracellular matrix (ECM). We combined the cell sheets with TDM for subcutaneous transplantation in nude mice and orthotopic jaw bone implantation in Sprague-Dawley rats to further compare the periodontal differentiation characteristics of SHEDs and DFCs in vivo (Figure 1). Thus, this study aims to investigate the effect of SHEDs on bio-root regeneration and explore a new cell source for bio-root construction and its future clinical applications.

Fig 1.

Schematic of the experimental design. DFCs: dental follicle cells; DFCSs: dental follicle cell sheets; DFCs/TDM: DFCs combined with TDM; SHEDs: stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth; SHEDSs: sheets of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth; SHEDSs/TDM: SHEDSs combined with TDM; TDM: treated dentin matrix.

Materials and methods

Isolation and culture of DFCs and SHEDs

Impacted third molars obtained from 16-20-year-old healthy young patients (n=12) and retained deciduous teeth from 6-10-year-old children (n=12), whose teeth were extracted for clinical reasons, were collected for cell isolation. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the ethical protocol approved by the Committee of Ethics of the Sichuan University, and written informed consent was obtained from all guardians on behalf of the children and teenagers enrolled in this study. Dental follicles of impacted third molars and dental pulp of retained deciduous teeth were dissected 3, 20 and rinsed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The tissues were cut into 1×1 mm blocks and incubated in α-MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, HyClone, USA) in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. The cell culture medium was replaced every 2 days. Then, we mixed the primary cells from different individuals at the beginning of the study, and the mixed DFCs and mixed SHEDs were used at passages 2-4 in all experiments to minimize the impact of individual differences.

Immunofluorescence staining and microscopy

A total of 1×105 DFCs and SHEDs were seeded into each well of a six-well plate and fixed with 4% polyoxymethylene for 15 min after 24 h of culture. The cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X100 for 15 min at room temperature. After 3 rinses with PBS, the cells were blocked with normal goat serum at 37 °C for 30 min in the dark. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies (anti-Vimentin, 1:200 dilution, Thermo, USA; anti-Cytokeratin 14, 1:200 dilution, Millipore, USA) at 4 °C in a humidified chamber overnight. Following 3 rinses with PBS, the cells were incubated with secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated goat anti-mouse, 1:200 dilution, Invitrogen, USA) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Next, cells were incubated with 100 ng/ml DAPI for 2 min to stain the nuclei. All samples were examined under a fluorescence microscope (OLYMPUS Corporation, Japan).

Colony-forming unit-fibroblast (CFU-F) assay

DFCs and SHEDs were seeded in a 100 mm dish at a density of 1×10 3 cells and cultured for 10 days. Cells were fixed with 4% polyoxymethylene for 15 min, washed 3 times with PBS and stained with 1% crystal violet. Colonies containing more than 50 cells were counted. The experiment was repeated at least three times.

Cell migration assay

Cell migration was determined using a Chemotaxicell chamber (8 μm pore size, Costar, USA). SHEDs and DFCs resuspended in α-MEM were added to the upper chamber at a density of 1×105 cells per well, and α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber and incubated for 18 h. Cells that migrated to the lower surface of the membrane were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 1% crystal violet. The experiment was repeated at least three times.

Cell proliferation assay

The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo, Japan) was used to quantitatively evaluate the proliferation of the DFCs and SHEDs. Cells were cultured in a 96-well plate at a primary density of 2×10 4 cells/ml for 9 days. The culture medium was replaced with 100 μl of α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 10 μl CCK-8 every two days. After an incubation at 37 °C for 3 h, all solutions were transferred from each well to a new 96-well plate. Four parallel replicates were prepared and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The test was repeated at least three times.

Then, the cells were labeled with BrdU (Invitrogen, USA) to further investigate the proliferation profiles of DFCs and SHEDs. A total of 5×10 3 DFCs and SHEDs were seeded into each well of a 6-well plate. Upon reaching 70% confluence, the culture medium was replaced with complete α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 30 μg/ml BrdU labeling reagent. Cells were incubated for 48 h, the labeling medium was removed and cells were gently washed with PBS twice. Cells were fixed with 75% acid alcohol for 20 min and washed with PBS 3 times. Next, immunocytochemical staining was performed. The primary antibody was anti-BrdU (1:200 dilution, Millipore, USA) and the secondary antibodies was Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:200 dilution, Invitrogen, USA). The cells were incubated with 100 ng/ml DAPI for 2 min to stain the nuclei. All samples were examined under a fluorescence microscope (OLYMPUS Corporation, Japan).

Tubule formation assay

A total of 1×10 5 DFCs and SHEDs were seeded into each well of a 6-well plate. After reaching 70% confluence, the culture medium was replaced with complete medium, and cells were cultured for an additional 48 h. Then, the conditioned media (CM) were collected for tubule formation assays with 2×10 4 human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) seeded in each Matrigel-coated well of 96-well plates. Endothelial cell medium served as the control group. After a 6 h incubation, phase-contrast images were acquired using an inverted microscope (Olympus, Japan). The numbers of nodes, junctions and meshes within each field were measured using Image-Pro Plus software.

Adipogenic differentiation

A total of 1×10 5 DFCs and SHEDs were seeded into each well of a 6-well plate. When the cells reached 70% confluence, the culture medium was replaced with complete α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM insulin (Sigma, USA), 0.5 mM isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX; Sigma, USA), and 10 nM dexamethasone (Sigma, USA) 29. α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS served as the negative control. The medium was refreshed every 2 days. After 15 days of culture, the cells were washed three times with PBS after fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and then incubated with a 0.3% Oil Red O (Sigma, USA) solution for 15 min. After 3 rinses with PBS, cells were routinely observed and photographed under a phase-contrast inverted microscope (Olympus, Japan). The expression of adipogenic genes PPARγ2, LPL and adiponectin was analyzed using real-time PCR. The primer sequences are listed in Table 1. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method 30 and normalized to the reference GAPDH gene. The experiment was repeated three times.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primer sequences.

| Target cDNA | Primer sequence (5 ' -- 3 ') | Target cDNA | Primer sequence (5 ' -- 3 ') |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPARγ2 | F GACCACTCCCACTCCTTTGA R CAGGCTCCACTTTGATTGC |

Nestin | F AGGAATGCCGCTAGTCTCTGA R GGACTCTCTATCTCCTTCCCTCTG |

| LPL | F CTAAGGACCCCTGAAGACACAGC R GGCACCCAACTCTCATACATTCC |

Tubb 3 | F GAAGACGACGAGGAGGAGTC R GGAGGACGAGGCCATAAATA |

| Adiponectin | F CCCATTCGCTTTACCAAGAT R GGCTGACCTTCACATCCTTC |

COL-1 | F AACATGGAGACTGGTGAGACCT R CGCCATACTCGAACTGGAATC |

| BSP | F CGAACAAGGCATAAACGGCACCAG R TTCTCCATTGTCTCCTCCGCTGCT |

Integrin β1 | F TTGTGAAGCCAGCAACGGACAG R CAAGGCAGGTCTGACACATCTCAC |

| ALP | F TAAGGACATCGCCTACCAGCTC R TCTTCCAGGTGTCAACGAGGT |

DMP-1 | F CTCGCACACACTCTCCCACTCAAA R TGGCTTTCCTCGCTCTGACTCTCT |

| OCN | F CTCACACTCCTCGCCCTATTG R CTCCCAGCCATTGATACAGGTAG |

GAPDH | F CTTTGGTATCGTGGAAGGACTC R GTAGAGGCAGGGATGATGTTCT |

| GFAP | F CAACCTGCAGATTCGAGAAA R GTCCTGCCTCACATCACATC |

Osteogenic differentiation

A total of 1×10 5 DFCs and SHEDs were seeded into each well of separate 6-well plates. Upon reaching 70% confluence, cells were cultured in osteogenic medium containing 10% FBS, 10 mM L-glycerophosphate (Sigma, USA), 100 μM dexamethasone (Sigma, USA), and 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid (Sigma, USA) 31 for 21 days. α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS served as the negative control. The medium was refreshed every 2 days. After 3 weeks, cells were washed twice with PBS after fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and then incubated with a 0.1% alizarin red solution (Sigma, USA) in Tris-HCl (pH 8.3) at 37 °C for 30 min. After 2 washes with PBS, cells were observed and photographed under a phase-contrast inverted microscope (Olympus, Japan). The expression of the osteogenic genes BSP, ALP and OCN was analyzed using real-time PCR. The primer sequences are listed in Table 1. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method and normalized to the reference GAPDH gene. The experiment was repeated three times.

Neurogenic differentiation

A total of 1×10 5 DFCs and SHEDs were seeded into each well of a 6-well plate. Upon reaching 70% confluence, cells were cultured in neurogenic medium containing 2% dimethyl sulfoxide, 200 μM butylated hydroxyanisole (Sigma, USA), 25 mM KCl (Kelong, China), 2 mM valproic acid (Sigma, USA), 10 μM forskolin (Sigma, USA), 1 μM hydroxycortisone (Sigma, USA), and 5 μg/mL insulin (Gibco, USA) 3. Cells grown in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS served as the negative control. After 4 h, cells were analyzed using immunofluorescence staining to determine the expression of the neural cell marker nestin (Abcam, USA). Images were captured and staining was analyzed under a fluorescence microscope (OLYMPUS, Japan). The expression of neurogenic genes GFAP, nestin and βIII-tubulin was analyzed using real-time PCR. The primer sequences are listed in Table 1. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method and normalized to the reference GAPDH gene. The experiment was repeated three times.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

DFCs and SHEDs were separately harvested and centrifuged (3000 g, 10 min, 4 °C) to form pellets, fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3) for 1 h at room temperature and postfixed with aq. 2% (v/v) osmium tetroxide for an additional 1 h. Following dehydration in a series of ethanol solutions (50, 70, 95 and 100%), the cells were embedded in Epon 812 resin. The cell pellets were cut into ultrathin sections, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and photographed under a transmission electron microscope (HT7700, Hitachi, Japan).

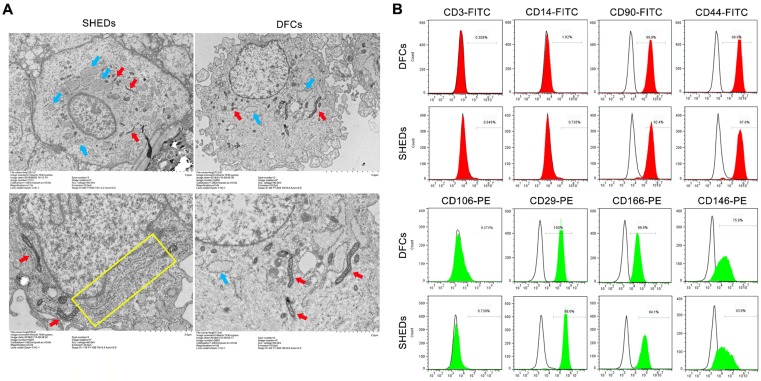

Flow cytometry analysis

DFCs and SHEDs were trypsinized and incubated with FITC-conjugated antibodies against CD3, CD14, CD44, and CD90 and PE-conjugated antibodies against CD146, CD166, CD106 and CD29 to determine the expression of cell surface markers. After washes with PBS, cells were suspended in PBS for analysis. All antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (CA, USA). Flow cytometry was performed using the Beckman Coulter Cytomics FC500 MPL system (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA). The experiment was repeated at least three times.

Culture of DFCSs and SHEDSs

DFCs and SHEDs at passage 3 were seeded in a 6-well plate at a density of 1×105 cells/well and cultured at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere until they reached 70% confluence. Then, 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid was added to the culture medium (Sigma, USA), which was replaced every 2 days. After an additional 14 days of culture, DFCSs and SHEDSs were observed and evaluated.

Histological examination of DFCSs and SHEDSs

The harvested DFCSs and SHEDSs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated in a series of ethanol solutions (50, 70, 95 and 100%), cleared with xylene and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson's trichrome (Baso Diagnostic Inc., China), and antibodies according to the manufacturer's recommended protocols.

Primary antibodies against COL-1 (1:200 dilution, Abcam, UK), DSP (1:200 dilution, Santa Cruz, USA), Fibronectin (1:200 dilution, Abcam, UK) and CAP (1:200 dilution, Santa Cruz, USA) were used for immunohistochemistry in the present study. PBS was used in place of the primary antibodies as a negative control, and secondary antibodies were visualized using the DAB kit (Gene Tech, China). This experiment was repeated three times.

Real-time PCR analysis

Real-time PCR was used to detect changes in the expression of odontogenic-related genes before (0 days) and 7 and 14 days after ascorbic acid induction to investigate the induction effect of extracellular matrix on DFCSs and SHEDSs. The RNAiso Plus kit (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Japan) was used to extract RNA from the DFCSs and SHEDSs according to the manufacturer's protocol. The cDNAs were synthesized and used for PCR as described in a previous study 32. The resulting cDNAs were amplified with SYBR Premix ExTaq (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Japan) using a QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). We measured the expression of the following genes: BSP, COL-1, Integrinβ1, ALP, OCN, DMP-1 and GAPDH. Primer sequences for those genes are listed in Table 1. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔ CT method and normalized to the reference GAPDH gene. This experiment was repeated at least three times.

Western blotting

The levels of odontogenic-related proteins were detected before (0 day) and after ascorbic acid induction using Western blotting. Total cellular proteins were extracted from DFCSs and SHEDSs using the Total Protein Extraction Kit (KeyGEN, China). Aliquots of 20 μg of each cell lysate were separated on polyacrylamide gels and blotted onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with 5% milk for 1 h and then incubated with primary antibodies (COL-1, Arigo, China; Integrinβ1, Abcam, UK; DMP-1, Millipore, USA; ALP, Zenbio, China; OCN, Zenbio, China; GAPDH, Zenbio, China) overnight followed by the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG antibodies (ZSGB-BIO, China). The labeled proteins were visualized using an ImageQuant LAS 4000 mini instrument (GE Healthcare).

Fabrication of human TDM

Human TDM was fabricated according to a well-established protocol described in a previous study 3. Briefly, after removing the crown, dental pulp, predentin and cementum using a mechanical method, the dentin was treated with 17% ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid (EDTA, Sigma, USA) for 12 min, 10% EDTA for 12 min, and 5% EDTA for 20 min. For sterilization, TDM was immersed in sterile PBS supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin for 24 h in 37 °C, then washed with sterile deionized water for 10 min in an ultrasonic cleaner, and finally stored in α-MEM at 4 °C. A scanning electron microscope (SEM; Inspect F, FEI, The Netherlands) was used to observe the morphology of human TDM.

Animals

All animal experiments described in this study were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the Ethics Committee of Sichuan University. The immunodeficient mice were purchased from KC BIO Co. Ltd. and the Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from DS Experimental Animals Co. Ltd.

Subcutaneous transplantation in nude mice

Cell sheets combined with human TDM were transplanted into the dorsum of immunodeficient mice (8-week-old males, n=9) under general anesthesia to further compare the odontogenic capacities of SHEDs and DFCs in vivo. Nine immunodeficient mice were randomly divided into three groups: (1) SHEDSs combined with TDM, (2) DFCSs combined with TDM, and (3) TDM alone. Each mouse was implanted with two samples. Eight weeks later, all samples were harvested from the immunodeficient mice, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, demineralized with 10% EDTA (pH 7.6) at 37 °C for 3 months, and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin sections were prepared and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson's trichrome, and immunohistochemical staining.

Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry included DMP-1 (1:250 dilution, Millipore, USA), DSP (1:200 dilution, Santa Cruz, USA), COL-1 (1:200 dilution, Abcam, UK), OCN (1:500 dilution, Zenbio, China), Periostin (1:500 dilution, Santa Cruz, USA), TGF-β1 (1:200 dilution, Abcam, UK) and β-tubulin III (1:200 dilution, Millipore, USA). All antibodies were used according to the manufacturers' protocol. PBS was used in place of the primary antibodies as the negative control and secondary antibodies were visualized using the DAB kit (Gene Tech, China).

In situ jaw bone transplantation in Sprague-Dawley rats

Nine Sprague-Dawley rats (12-week-old males) were randomly divided into three separate groups with three rats per group. After the rats were anesthetized, the gums were incised from the neck of the lower incisor and a mucoperiosteal flap was created to expose the edentulous area of the mandible. The surgical defects, which were approximately 2×2 mm holes in both left and right sides of mandible, were generated on the buccal side of the edentulous area. Then, human TDM wrapped with SHEDSs and DFCSs was implanted into the defect. Implanted TDM alone served as the negative control, while the normal natural tooth served as the positive control. The gingiva was carefully sutured after surgery, and the animals received antibiotics for 3 days after surgery. Sprague-Dawley rats were sacrificed after 8 weeks, and the mandibles were harvested and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. All samples were then demineralized for more than three months, embedded and sectioned into 5 µm thick sections for histological analyses according to the manufacturer's recommended protocols. The sizes of periodontal ligament tissues in each group were measured quantitatively. The thickness of fibers was calculated by measuring the average distance from the bone to TDM surface. The fiber angle was the inclination angle between the long axis of the fibers and the tangent to the surface of TDM 33. The number of vessels was defined as total number of vessels per square millimeter.

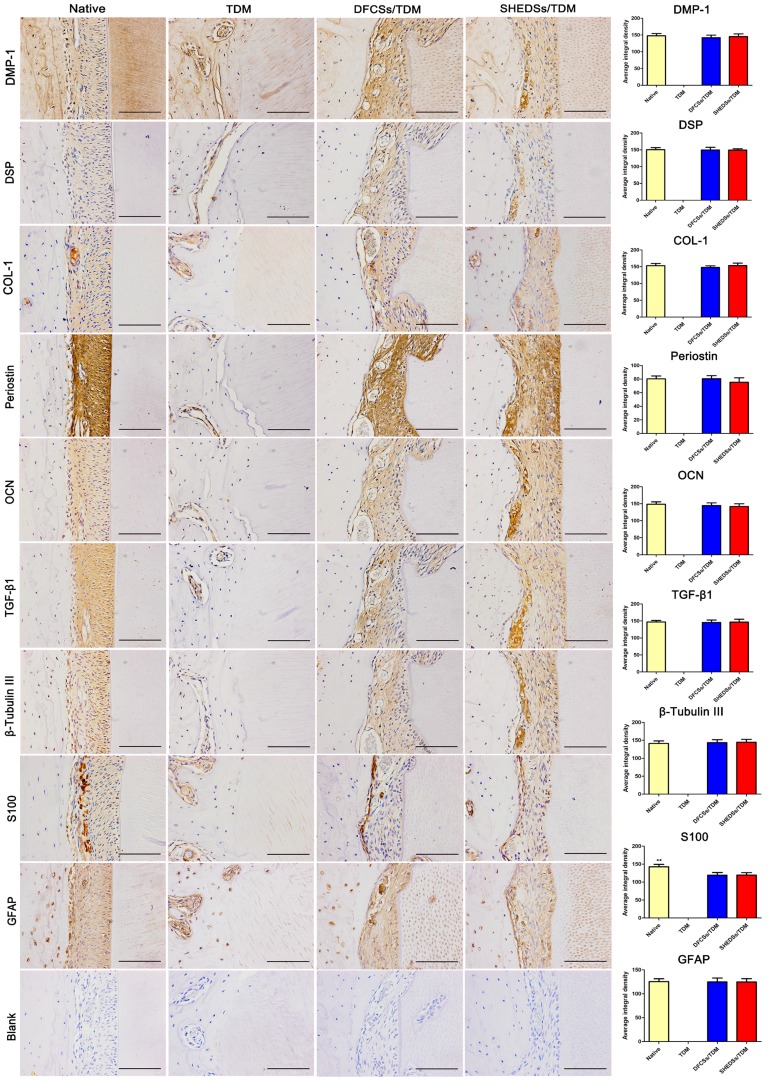

Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry included DMP-1 (1:250 dilution, Millipore, USA), DSP (1:200 dilution, Santa Cruz, USA), COL-1 (1:200 dilution, Zenbio, China), OCN (1:500 dilution, Zenbio, China), Periostin (1:500 dilution, Santa Cruz, USA), TGF-β1 (1:200 dilution, Abcam, UK), β-tubulin III (1:200 dilution, Millipore, USA), GFAP (1:200 dilution, Abcam, UK), and S100 (1:200 dilution, Abcam, UK). All antibodies were used according to the manufacturers' protocol. PBS was used in place of the primary antibodies as the negative control and secondary antibodies were visualized using the DAB kit (Gene Tech, China). Then, a quantitative analysis of IHC staining was conducted. The average integrated density was measured using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as means ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed using SPSS 11.5 software (SPSS, USA). Student's paired t-test and one-way ANOVA were used to determine the level of significance. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Culture, identification and characterization of DFCs and SHEDs

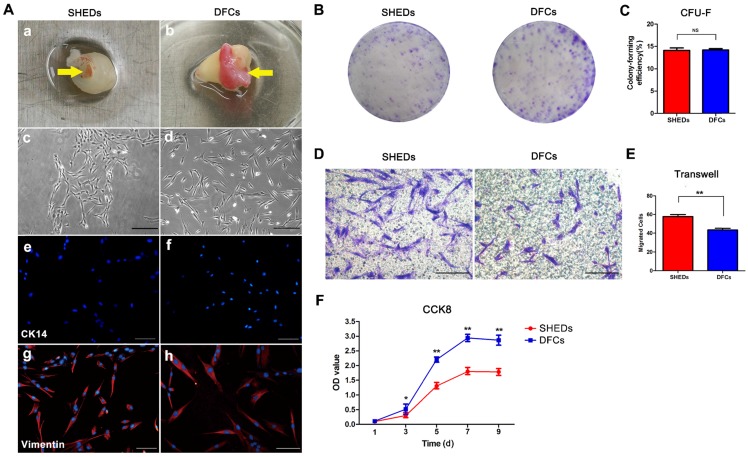

Primary DFCs and SHEDs were successfully obtained from the dental pulp of retained deciduous teeth (Figure 2A a) and dental follicles of impacted third molars (Figure 2A b), respectively, and cultured to passage 3. Both DFCs and SHEDs showed similar morphologies, as evidenced by the typical morphology of mesenchymal cells with a spindle shape (Figure 2A c and d). Immunofluorescence staining revealed the expression of the mesenchymal cell marker vimentin in both cell types (Figure 2A g and h), but the cells did not express CK14 (Figure 2A e and f), which are characteristic proteins expressed in epithelial cells. Crystal violet staining of colony-forming unit-fibroblasts (CFU-Fs) confirmed that all cultures contained the clonogenic proliferating cells that were able to generate clonal units from a single cell (Figure 2B) and had the similar colony formation efficiency of 14.08 ± 1.42% for SHEDs and 14.20 ± 0.72% for DFCs (Figure 2C). After 18 h of culture in the wells of a transwell plate, cells that migrated to the lower surface of the membrane were stained with 1% crystal violet (Figure 2D). More SHEDs migrated to the opposite side of the membrane than DFCs (Figure 2E), indicating an increased migration ability of SHEDs. Growth curves of SHEDs and DFCs were analyzed using the CCK-8 assay and showed that DFCs at passage 3 displayed greater proliferation than SHEDs (Figure 2F). The BrdU assay also produced similar results. The percentage of BrdU-positive DFCs was 83.59 ± 2.82%, a value that was higher than it was for SHEDs at 68.88 ± 2.66% (Figure 3A and B).

Fig 2.

Morphology and biological characteristics of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHEDs) and dental follicle cells (DFCs). Dental pulp from the retained deciduous teeth and dental follicles of impacted third molars (yellow arrows) was dissected (A a and b) and cultured to passage 3. Both DFCs and SHEDs showed the typical morphology of mesenchymal cells with a spindle shape (A c and d). Immunofluorescence staining revealed vimentin expression (A g and h), but negative staining for CK-14 in both cell types (A e and f). Crystal violet staining of colony-forming unit-fibroblasts (B) indicated that both SHEDs and DFCs contained the clonogenic proliferating cells that were able to generate clonal units. The colony formation efficiency was not significantly different between the two groups (C). After 18 h of culture in transwells, crystal violet staining (D) showed that more SHEDs migrated to the opposite side of the membrane than DFCs (E). Growth curves were analyzed using the CCK-8 assay and showed that DFCs displayed a higher proliferation capacity than SHEDs (F). Scale bars =100 μm, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, and NS not significant.

Fig 3.

BrdU incorporation and tubule formation assays using DFCs and SHEDs. Immunofluorescence staining after an incubation with BrdU for 48 h (A). More DFCs displayed BrdU-positive staining, suggesting a higher proliferation rate than SHEDs (B). In vitro tube formation by HUVECs in Matrigel induced by conditioned media from DFCs and SHEDs (C). Typical tube-like structures in different groups are shown. The numbers of nodes (D), junctions (E) and meshes (F) per field of view in the three groups were analyzed. Scale bars =200 μm, * p<0.05 and ** p<0.01.

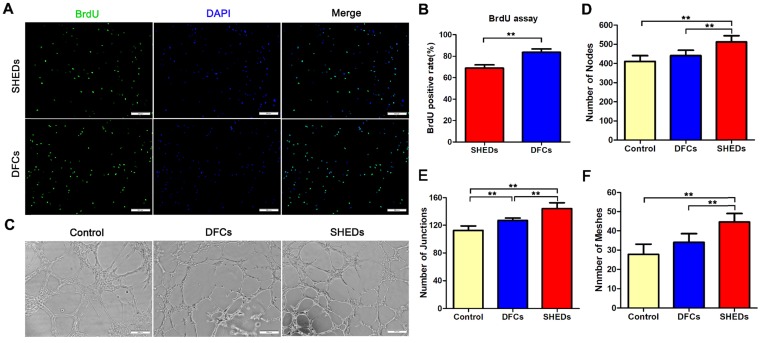

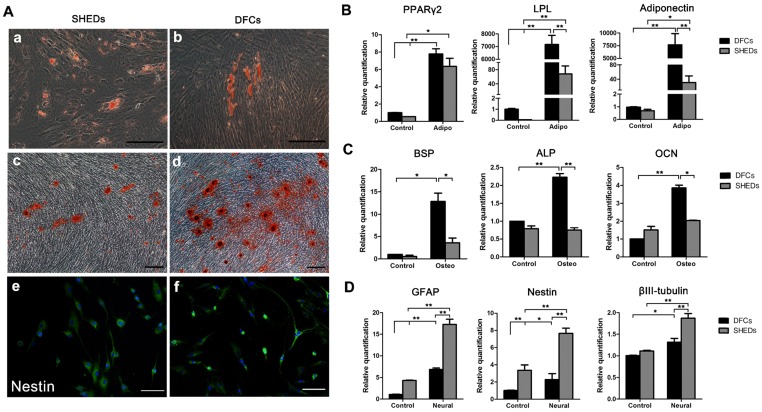

Angiogenic effects of DFCs-CM and SHEDs-CM on HUVECs were evaluated. After induction for 6 h, all groups successfully formed typical tubular structures (Figure 3C). Greater numbers of nodes, junctions and meshes were observed within each field in the SHEDs-CM group than in the DFCs-CM and control groups (Figure 3D-F). After culture under adipogenic conditions for 15 days, lipid droplets were positively stained with oil red O in both groups (Figure 4A a and b). Real-time PCR revealed increased expression of relative quantification to adipogenic genes PPARγ2, LPL and adiponectin in the DFC group (nearly 10-fold higher than the SHED group) after induction (Figure 4B). After 21 days of culture in osteogenesis induction medium, both cell types were positive for alizarin red staining, which is implicated in the formation of mineralized tubules (Figure 4A c and d). Both the number of mineralized tubules and the expression of osteogenic-related genes were higher in DFCs than in the SHED group (Figure 4C). Positive staining for the neurogenic marker nestin was observed in SHEDs and DFCs at 4 h after the induction of neural differentiation (Figure 4A e and f), but SHEDs expressed GFAP, βIII-tubulin and nestin at higher levels than DFCs (Figure 4D).

Fig 4.

Characteristics of the multidifferentiation potential of dental follicle cells (DFCs) and stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHEDs). Oil red O staining of lipid clusters in SHEDs and DFCs after culture under adipogenic conditions (A a and b). Real-time PCR was also used to detect the expression of relative quantification to adipogenic genes before and after induction (B). Mineralized nodules were observed in both groups after 21 days of osteogenic induction (A c and d). Both the numbers of mineralized nodules and the expression of relative quantification to osteogenic genes were higher in DFCs than in the SHED group (C). Positive staining for the neurogenic maker nestin was observed 4 h after neural induction in SHEDs and DFCs (A e and f), but SHEDs expressed more GFAP, βIII-tubulin and nestin than DFCs (D). Scale bars =100 μm, * p<0.05 and ** p<0.01.

In the ultrastructural comparison (Figure 5A), both DFCs and SHEDs exhibited a similar cytoarchitecture, as large numbers of mitochondria, vesicles, and primary and secondary lysosomes were observed. However, a greater amount of rough endoplasmic reticulum was observed in the cytoplasm of SHEDs.

Fig 5.

Analysis of the ultrastructure and expression of cell surface markers. Transmission electron microscopy analysis of SHEDs and DFCs (A). Both DFCs and SHEDs exhibited similar cytoarchitectures, as large numbers of mitochondria (red arrows), vesicles (blue arrows), and primary and secondary lysosomes were observed. A greater number of rough endoplasmic reticulum (yellow rectangle) were observed in the cytoplasm of SHEDs. Flow cytometry indicated that SHEDs and DFCs possessed similar immuno-phenotypic characteristics (B). The cells all expressed CD90, CD44, CD29, CD146 and CD166, but did not express CD3, CD14 and CD106.

According to the flow cytometry analysis of stem cell surface markers, SHEDs and DFCs displayed similar immuno-phenotypic characteristics (Figure 5B). Both of them expressed the mesenchymal stem cell markers CD146 and CD166, adhesion molecule CD29, receptor molecule CD44 and extracellular matrix protein CD90, but they did not express the hematopoietic lineage markers CD3, CD14 and CD106.

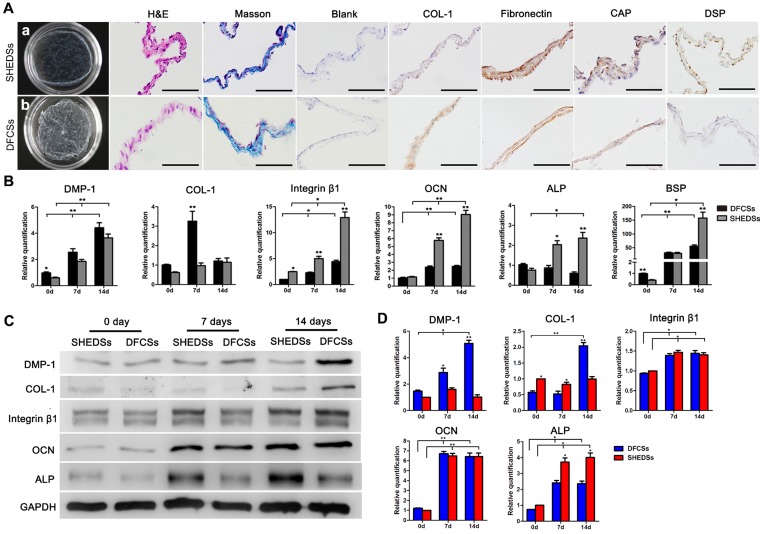

Culture and characteristics of DFCSs and SHEDSs

After 14 days of culture with ascorbic acid-containing medium, both DFCSs and SHEDSs formed translucent membranes that were able to be mechanically scraped from the edge of the dishes (Figure 6A a and b). H&E and Masson's trichrome staining revealed that both DFCSs and SHEDSs consisted of 2-3 layers of cells and contained blue-stained collagen fibers (Figure 6A). Immunocytochemical staining revealed the expression of the cementum-specific protein CAP, dentin-specific protein DSP and COL-1 and fibronectin, proteins that are mainly found in ECM and play important roles in intercellular signal connection, in both sheets (Figure 6A).

Fig 6.

Cell sheet characteristics and in vitro differentiation of both cell types induced by ECM. Macroscopic view of the cell sheets after culture for 15 days in vitro (Aa and b). HE staining showed that both sheets consisted of 2-3 layers of cells and Masson's trichrome staining indicated that the membranes were rich in collagen fibers (A). Immunocytochemical staining revealed the expression of the ECM proteins COL-1 and fibronectin and odontogenic proteins CAP and DSP in both DFCSs and SHEDSs (A). The expression of odontogenic genes in DFCSs and SHEDSs after ascorbic acid induction for 0, 7 and 14 days was detected using real-time PCR, and relative quantification (RQ) values were calculated (B). Western blotting was also utilized to detect the levels of related proteins, with GAPDH serving as internal control (C) and the relative levels were quantified (D). After forming the cell sheets, DFCSs expressed the DMP-1 and COL-1 proteins at higher levels, while SHEDSs expressed ALP at higher levels. The levels of the OCN and Integrin β1 proteins were not statistically significantly different between the two groups from days 7 to 14. Scale bars =200 μm, * p<0.05 and ** p<0.01.

The results of real-time PCR demonstrated a significant upregulation of the expression of the odontogenic genes DMP-1, integrinβ1, OCN, ALP and BSP during the process of forming the cell sheet compared with the control group (0 days) that peaked on day 14 (Figure 6B). Moreover, OCN, ALP, BSP and integrin β1 were expressed at much higher levels in SHEDSs than in DFCSs on days 7 and 14, whereas DMP-1 expression was slightly increased in DFCSs during this period. In DFCSs, COL-1 expression peaked on day 7 and was followed by a decline thereafter. Meanwhile, in the SHEDSs group, COL-1 expression gradually increased from day 0 to day 14, with no significant difference from the DFCSs group on day 14. Protein levels were detected using Western blotting and were statistically quantified (Figure 6C and D). On day 7, DFCSs expressed DMP-1 at higher levels, but the protein levels of COL-1 and ALP were increased in the SHEDSs group. The levels of nearly all of the proteins expressed in both groups were increased from days 7 to 14. On day 14, DFCSs expressed more DMP-1 and COL-1, while ALP was still expressed at higher levels in SHEDSs. The levels of the OCN and integrinβ1 proteins were not significantly different between the two groups on both day 7 and day 14.

In vivo periodontal regeneration induced by DFCSs and SHEDSs combined with human TDM

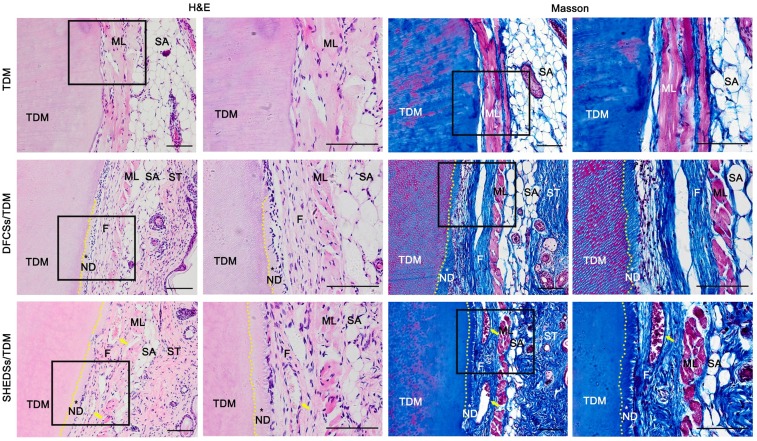

Nude mice subcutaneous model

Samples were collected 8 weeks after the subcutaneous transplantation of the composites in nude mice. H&E and Masson's trichrome staining (Figure 7) revealed newly formed dentin and periodontal fiber-like structures that displayed a dense and well-aligned arrangement between the TDM surface and subcutaneous muscle layer in mice in both the SHEDSs/TDM and DFCSs/TDM groups. However, the control group (TDM alone) did not present either neo-dentin or collagen fiber structures, and the TDM was directly covered by the subcutaneous muscle layer and its fascia.

Fig 7.

Odontogenic differentiation of DFCSs and SHEDSs combined with human TDM in nude mice. The composites were transplanted into subcutaneous sites and allowed to grow for 8 weeks. No new tissue was observed in the control group, and the TDM was directly covered by the subcutaneous muscle layer and its fascia. However, newly formed predentin and periodontal ligament-like fibers between the TDM surface and mouse subcutaneous muscle layer were successfully generated in both the DFCSs/TDM and SHEDSs/TDM groups. Masson staining also further confirmed the same results. Scale bars =100 μm. (F: periodontal ligament-like fibers; ML: muscle layer; ND: new dentin; SA: subcutaneous adipose tissue; ST: skin tissue; TDM: treated dentin matrix; yellow arrow: blood vessel).

Immunohistochemistry was used to evaluate the regenerated periodontal tissue (Figure S1). Both the SHEDSs/TDM and DFCSs/TDM groups expressed the dentin-specific proteins DSP and DMP-1, indicating that dentin formed in the human TDM. Meanwhile, COL-1 and Periostin, which are regarded as the main components of periodontal ligament fibers, were also expressed by the regenerated tissues in the two experimental groups. The expression of the osteogenic-related marker OCN indicated mineralization in the newly formed predentin. In addition, TGF-β1 and β-Tubulin III, which are regarded as markers that induce the formation of connective and nerve-like tissues, were also expressed in both experimental groups. However, in the control group, only murine subcutaneous muscle tissues were positively stained, but no newly formed tissues were observed.

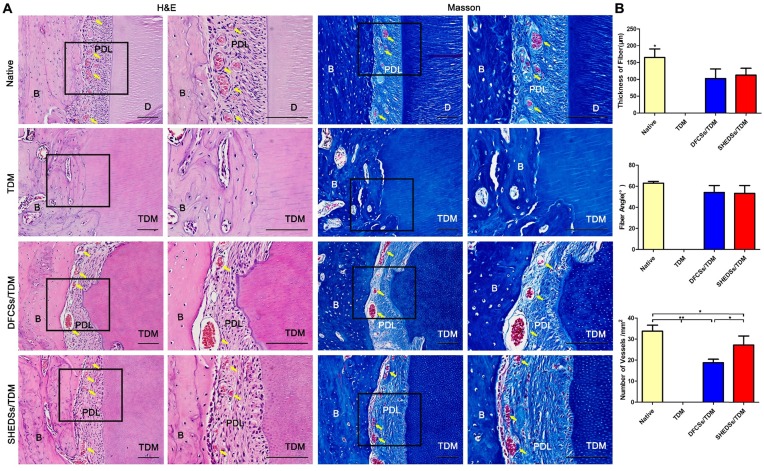

Sprague-Dawley rat Orthotopic model

In the nude mice subcutaneous model, we have already verified that SHEDs possessed a similar periodontal regeneration capacity to DFCs. However, the subcutaneous microenvironment differs substantially from the alveolar bone. SHEDSs/TDM and DFCSs/TDM were implanted in jaw bones for 8 weeks to further verify their potential in periodontal and bio-root regeneration. Histological staining showed the presence of soft tissues between the TDM surface and jaw bone in both the SHEDSs/TDM and DFCSs/TDM groups (Figure 8A). An obvious difference was not detected between SHEDSs/TDM and DFCSs/TDM groups, and the regenerated soft tissues observed in the two experimental groups were all composed of fibroblasts and collagen fibers, which were densely arranged and well-organized. Notably, part of the fibers on the TDM side were arranged perpendicular to the surface of the TDM, which was very similar to the native periodontal ligament fibers. Additionally, blood vessels were observed in the periodontal clearance in the two experimental groups, suggesting that a good nutrient supply was available. However, in the control group (TDM alone), neither clearance nor periodontal ligament structures were observed. Instead, the TDM was directly surrounded by the jaw bone.

Fig 8.

Orthotopic implantation of bio-root composites in the jaw bones of Sprague-Dawley rats for 8 weeks. H&E staining verified that both the SHEDSs/TDM and DFCSs/TDM groups possessed a clearance between the TDM and jaw bone, which exhibited similar characteristics to native tooth root, including dense collagen fibers, fibroblasts, and blood vessels (yellow arrow) contributing to the formation of periodontal ligament tissues (A). However, in the TDM alone group, neither clearance nor periodontal ligament-like structures were observed between the TDM surface and jaw bone. Masson's trichrome staining also further confirmed the same results. The sizes of regenerated periodontal tissues in vivo were measured (B), including the fiber thickness, the fiber angle and the number of vessels in four groups. Scale bars =100 μm. (B: jaw bone; D: dentin; PDL: periodontal ligament tissue; TDM: treated dentin matrix).

In addition, the sizes of periodontal ligament tissues in each group were analyzed quantitatively (Figure 8B). A statistically significant difference in the average fiber thickness was not observed between the experimental groups, but all fibers were thinner than those of the natural tooth. The fiber angle was 53.3 ± 6.8 ° in the SHEDSs/TDM group and 54.2 ± 5.8 ° in the DFCSs/TDM group, while it was 63.0 ± 1.5 ° in natural tooth group. Although the results of the statistical analysis did not reveal a significant difference between three groups, the fiber angle of the natural tooth was more uniform with a smaller standard deviation, while the two experimental groups exhibited a larger standard deviation. The total number of vessels was increased in the SHEDSs/TDM group compared with the DFCSs/TDM group, consistent with the results of tubule formation assay in vitro.

Furthermore, immunohistochemistry was used to identify the newly formed periodontal ligament tissues in the SHEDSs/TDM and DFCSs/TDM groups (Figure 9). The regenerated tissues in both the SHEDSs/TDM and DFCSs/TDM groups expressed the dentin markers DMP-1 and DSP, the periodontal ligament marker COL-1, Periostin and the osteogenic-related markers OCN, with the same patterns observed in native periodontal tissue. In addition, TGF-β1, which is regarded as a marker that promotes the reconstruction of connective tissues, was also expressed in both experimental groups and the native group. More importantly, positive staining for specific nerve tissue markers β-Tubulin III, GFAP and S100 was detected in the two experimental groups, similar to the native tooth root. However, in the TDM alone group, no periodontal ligament fibers were observed, and the staining for the aforementioned markers was all negative, except for DMP-1. Based on these observations, SHEDSs maintained same odontogenic capacity as DFCSs in the jaw bone microenvironment. The quantitative analysis of IHC staining (Figure 9) did not reveal significant differences between the native root and the two experimental groups in the average integrated density of staining in periodontal tissues, except for S100. S100 was expressed at lower levels in both experimental groups than in natural teeth, indicating that the nerve fibers existed in newborn periodontal tissues, but a gap with the natural tooth root existed.

Fig 9.

Immunohistochemical evaluation of the odontogenic and neurogenic differentiation of bio-root composites in jaw bones after 8 weeks. Similar to native periodontal tissues, the regenerated periodontal ligament fibers in both the SHEDSs/TDM and DFCSs/TDM groups displayed positive staining for the related markers DMP-1, DSP, COL-1, Periostin and OCN. Positive staining for TGF-β1, which is regarded as a marker of the reconstruction of connective tissues, was also observed in both experimental groups and the native group. The specific nerve tissue markers β-Tubulin III, GFAP and S100 exhibited positive staining in two experimental groups, similar to the native tooth root. In the TDM alone group, no PDL-like fibers were observed and the staining for the markers was all negative, except for DMP-1. The PBS negative control did not produce staining in the harvested tissues (Blank). A quantitative analysis was also performed by measuring the average integrated density of periodontal tissues. Scale bars =100 μm.

Discussion

The selection of seeding cells plays an essential role in tissue engineering research, as these cells participate in the regeneration of new tissues 6, 7. As shown in our previous study, DFCs regenerate periodontal and dental pulp-like tissues and is a promising seeding cell for bio-root regeneration 12, 13, 32. However, one major drawback of using DFCs is that the patient must have an unerupted third molar with a developing tooth root. Therefore, new cell sources for root regeneration are required.

SHEDs, as cell type that exists in almost everyone, possess the advantages of abundant sources, convenient access and excellent odontogenic differentiation potential 25-27, 34. The results of the comparison of ultrastructures in the present study showed that both DFCs and SHEDs were involved in active cell metabolism and autophagy processes, which are crucial for stem cell immune defense, self-renewal and apoptosis 35, 36. Meanwhile, SHEDs possessed more powerful protein synthesis and secretion functions than DFCs, leading to the formation of a local microenvironment that is conducive to tissue repair and regeneration, which has been highlighted in the field of nerve regeneration 37-39. SHED-derived exosomes inhibit neuronal apoptosis induced by 6-hydroxydopamine, thereby protecting injured nerve 40. Meanwhile, SHEDs exhibited excellent neurogenesis and angiogenesis potential and increased migration compared with DFCs in the present study. These results might be attributed to the fact that SHEDs are derived from the neural crest ectoderm and has the advantage of being able to differentiate into ectodermal tissues, such as nerve tissues 20. Other researchers also demonstrated that SHEDs possess the potential to differentiate into dopaminergic neurons, which have been used to treat central and peripheral nervous system lesions 41. All the results described above implied the promising application potential of SHEDs in functional periodontal regeneration, which requires abundant teleneurons and baroreceptors. However, in this comparative study, DFCs still exhibited a higher proliferation rate and stronger osteogenesis capacity than SHEDs. This finding is probably explained by the fact that DFCs were derived from a developing tissue and are progenitor cells that participate in the development of alveolar bone around the apical surface 42. Thus, we conducted further experiments to confirm the potential utility of SHEDs in the field of periodontal and bio-root regeneration.

Actually, except for the inherent characteristics of seeding cells, the regional microenvironment is also an indispensable factor for maintaining regular cell proliferation, differentiation, metabolism and functions 43. In this regard, cell sheeting technology possesses unique advantages in providing the appropriate microenvironment for the proliferation and differentiation of cells, such as promoting the abundant secretion of ECM and retaining growth factors and cell surface receptors 44, 45. Due to the high cell inoculation rate, uniform distribution and good operability, cell sheeting technology has shown prominent potential in periodontal tissue engineering regeneration 45, 46. In the present study, ascorbic acid 47 was utilized to promote the secretion of extracellular matrix and fabricated SHEDSs and DFCSs that contained multiple layers of cells rich in ECM. The expression of ECM genes and proteins was increased in both groups, and the expression of osteogenic and odontogenic genes and proteins were also upregulated after 14 days of culture. Thus, the secretion of ECM promoted the formation of cell sheets and increased the osteogenesis and odontogenesis potential of cells. This result also illustrated that cell sheeting technology represents an attractive periodontal regeneration approach because it simulates the anatomical features of the periodontal ligament 48. In addition, SHEDSs exhibited better osteogenesis activity during this induction process than DFCSs by upregulating the expression of the ALP, OCN and BSP mRNAs and proteins, which are considered markers of osteogenic differentiation at the mineralization stage 49. Actually, this result contradicts the previous results from osteogenic induction. A potential explanation is the difference between the components of the osteoblast medium and the cell sheet medium. Ascorbic acid, a component of osteogenic induction medium, is an antioxidant that inhibits or reduces apoptosis and is also beneficial to the autocrine and paracrine functions of cells 50. In the process of forming a cell sheet, SHEDs might be more sensitive to ascorbic acid than DFCs and tend to differentiate into osteoblast precursor cells that spontaneously promote bone formation. Briefly, the results described above confirmed the potential applicability of SHEDs in periodontal and bio-root regeneration.

SHEDSs and DFCSs combined with TDM were transplanted subcutaneously into nude mice to further verify their performance in vivo. Our previous studies have confirmed that TDM, which is regarded as a natural acellular matrix scaffold, is a suitable scaffold material for dentin and periodontal regeneration 3, 13, 31. Moreover, TDM also contains abundant dentinogenesis-related factors and proteins that provide an induced microenvironment for the construction of the tooth root 3. Therefore, we selected TDM as the appropriate scaffold in this study. Both combinations had the ability to regenerate dentin and periodontal ligament-like fibrous tissues. All regenerated tissues in the two groups expressed periodontal proteins (DMP-1, DSP, OCN, COL-1, Periostin, and TGF-β1) and a neural marker (β-Tubulin III), confirming the typical features of periodontal fibers in the regenerated tissues. The odontogenic differentiation potentials of SHEDs and DFCs were comparable in vivo. However, in this animal model, the microenvironment at the transplant site differs substantially from the alveolar bone and lacks the sufficient odontogenic stimulus. Thus, the newly formed fibers in both groups were tenuous, and the majority of regenerated fibers were oriented parallel to the surface of the dentin rather than anchoring or inserting in it, which is an important feature of the functional periodontal tissues 51. Therefore, SHEDSs/TDM and DFCSs/TDM complexes were orthotopically transplanted into the jaw bones to further validate the periodontal regeneration capacity of SHEDs.

Eight weeks after in situ implantation, both groups exhibited a soft tissue clearance between the TDM and jaw bone, which displayed similar characteristics to the native tooth root, including dense and well-aligned collagen fibers, fibroblasts, and blood vessels contributing to periodontal ligament tissue formation. Most importantly, the regenerated fibers near the TDM surface were oriented perpendicularly and inserted into the TDM in both experimental groups. These fibers were very similar to the native periodontal ligament fibers, which are known to insert into the tooth root at a certain angle, and this structure would enhance the maintenance of tooth root in the jaws and provide the necessary structure for mechanical loading 52. The positive expression of the dentin-specific proteins DSP and DMP-1 verified the occurrence of the biomineralization process in dentin 53, 54. Positive staining for COL-1, which is regarded as one major ECM protein of the connective tissue matrix 55, was detected in the periodontal ligament fibers of the two groups; this is consistent with that of the native tooth root. Periostin is an ECM protein that is specifically expressed in collagen-rich connective tissues under constant mechanical stress, such as the periodontal ligament, tendon, and periosteum 56. It plays an important role in the development and eruption of teeth and is also essential for the integrity and function of the periodontal ligament 57. Therefore, numerous studies of periodontal regeneration regard Periostin as one of the specific markers of PDLSCs and a key factor to evaluate when characterizing periodontal ligament tissues. In the present study, increased Periostin expression was observed in both the experimental groups and the native tooth root, suggesting that the newly formed tissues were indeed periodontal ligament fibers. The expression of the osteogenesis-related marker OCN suggested the formation and mineralization of nodules and new bone 49. All these results confirmed the successful regeneration of the periodontal ligament-alveolar bone complex. More importantly, more vessels were observed in the SHEDSs/TDM group. Thus, SHEDSs promoted the reconstruction of blood vessels in the regenerated collagen fibers, which is very important in functional periodontal tissue regeneration. SHEDs were induced to differentiate into functional vascular smooth muscle cells and form vascular-like structures in vitro in a previous study, implying that SHEDs also represent a feasible source of perivascular cells for in vivo angiogenesis 58,59. Moreover, except for the newly formed blood vessels, neuroid tissues were positively stained for β-Tubulin III, GFAP and S100 in both groups. β-Tubulin III is a microtubule protein that is exclusively expressed in neurons and is a specific marker of neurons in nervous tissue 60. GFAP is a unique intermediate filament component of mature astrocytes that plays an important role in neurophysiological functions and pathological processes 61. S100 is a characteristic marker of Schwann cells in peripheral nerve 62. In the natural periodontal tissue, S100 is distributed in the apical segment of tooth root and is located close to the alveolar bone, presenting an oval lamellar hyperchromatic structure. The positive staining for these markers indicated that the regenerated periodontal tissues in both experimental groups were characterized by the growth of new nerve fibers. All of these results illustrated the efficient perfusion of nutrients and the appropriate extension of nerve into the regenerated periodontal ligament tissues, similar to the native tooth root 63. In conclusion, both the SHEDSs/TDM and DFCSs/TDM groups successfully regenerated periodontal tissues, without an obvious difference between two composites.

While DFCs and SHEDs exhibited different differentiation patterns in vitro, no differences in neurogenic and odontogenic differentiation were observed in vivo. First, SHEDSs/TDM did not exhibit stronger neurogenic ability than DFCSs/TDM. We hypothesized that this difference may be due to the strong induction of neurogenic differentiation by the microenvironment in vitro, but this stimulus was very rarely encountered in the jaw bone. Second, a significant difference in osteogenesis was not observed between the two groups. Actually, we created a 2×2 mm bone defect in SD rats, which does not meet the requirement of a critical size bone defect 64, to reduce the detachment of the implant. This approach allowed the rats to heal the bone defects on their own. In subsequent experiments, rhesus monkeys will be selected as the animal model to produce a sufficiently large bone defect, and some neural growth factors will be added to promote the neurogenic differentiation of SHEDs.

In conclusion, this study confirmed that both cell strategies are feasible, and SHEDs represent an alternative cell source for use in periodontal and bio-root regeneration. SHEDs maintained their stem cell characteristics but exhibited a substantial proliferation capacity in vitro. SHEDs were also induced to differentiate into dentin and periodontal ligament tissues in vivo. From the perspective of tooth development, SHEDs and DFCs employ similar molecular regulation and signaling pathways throughout tooth root formation, but each has its own strengths. DFCs produce the cementum, periodontal ligament and alveolar bone through the signaling networks mediated by Gli1, Nfic, FGF, BMP/ TGFβ, WNT and PTHrP/PPR 65. Starting with the migration of DFCs, a number of cytoplasmic processes are projected and begin secreting collagen fibers. The proper secretion and distribution of these collagen fibers contribute to the correct orientation and attachment of the PDL, which is required to connect the root and alveolar bone by stabilizing and preparing the tooth for mastication 66,67. Combining the developmental process with the results of previous experiments, DFCs are considered a suitable seeding cell type for bio-root construction. However, functional periodontal tissues still acquire adequate nutrient perfusion and a sympathetic nerve supply. DFCs show slight defects in these processes. SHEDs are derived from neural crest cells and are capable of forming integrated dental pulp tissue containing the odontoblast layer, blood vessels, and nerve cells. Based on accumulating evidence, by activating the BMP-4/ TGFβ, WNT, and AKT pathways and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase, SHEDs also regulate biomineralization 28. The endogenous basic fibroblast growth factor secreted by SHEDs might participate in colony formation and osteogenic differentiation 68. This information provides a clue to the use of SHEDs in periodontal regeneration. After induction, SHEDs also promote the migration and differentiation of endogenous neural stem cells and induce angiogenesis and neurogenesis through paracrine signaling 38,59. Notably, SHEDs are easier and more convenient to obtain, with little or no trauma 27, 28. Additionally, an international SHED bank is already established and provides a perfect opportunity for clinical patients to benefit from this convenient source of stem cells 69. People typically have 20 deciduous teeth, providing more opportunities for patients to store SHEDs than umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (UCMSCs) or placental mesenchymal stem cells (pMSCs), which can only be obtained once in a lifetime. A study has also verified that the cryopreservation of intact exfoliated deciduous teeth appears to be a useful method for preserving SHEDs 26. Thus, SHEDs are a promising seeding cell for clinical applications in treating oral diseases, and the combination of SHEDSs with TDM may be available for future clinical applications.

However, although the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone were successfully regenerated, several problems remain to be solved. The SHEDs/TDM strategy must be investigated further in rhesus monkeys, whose alveolar bone microenvironments are more similar to humans. Immunoregulation is another major issue, as the irregular absorption of TDM also occurred. Further studies are needed to examine methods to regulate the balance between the osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis processes. Additionally, a series of standardized operation procedures and a safety evaluation system must be established to guarantee the feasibility of the clinical application of SHEDs.

Conclusions

As shown in the present study, similar to DFCs, SHEDs exhibited excellent cytobiological characteristics in vitro and contributed to the regeneration of dentin and periodontal tissues when combined with TDM in vivo. Our findings contribute to the improvement of current dental tissue engineering protocols using cell-based approaches and indicate that SHEDs represent a promising seeding cell for bio-root construction therapies and future clinical applications.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figure.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31600789), National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFA0104800), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2016SCU11051).

Contributions

Xueting Yang: Performed the experiments and wrote the article; Yue Ma: proofread the article; Weihua Guo: provided the method for preparing the TDM; Bo Yang: designed the study, guided the experiments and revised the article; Weidong Tian: reviewed the article.

Abbreviations

- CM

conditioned media

- DFCs

dental follicle cells

- DFCSs

dental follicle cell sheets

- DPSCs

dental pulp stem cells

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- GMSCs

gingival mesenchymal stem cells

- HUVECs

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- JBMSCs

jaw bone mesenchymal stem cells

- PDLSCs

periodontal ligament stem cells

- pMSCs

placental mesenchymal stem cells

- SCAPs

stem cells from apical papilla

- SHEDs

stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth

- SHEDSs

cell sheets of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth

- TDM

treated dentin matrix

- UCMSCs

umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells

References

- 1.Zang S, Jin L, Kang S, Hu X, Wang M, Wang J. et al. Periodontal wound healing by transplantation of jaw bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in chitosan/anorganic bovine bone carrier into one-wall infrabony defects in beagles. J periodontol. 2016;87:971–81. doi: 10.1902/jop.2016.150504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ding G, Liu Y, Wang W, Wei F, Liu D, Fan Z. et al. Allogeneic periodontal ligament stem cell therapy for periodontitis in swine. Stem cells. 2010;28:1829–38. doi: 10.1002/stem.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li R, Guo W, Yang B, Guo L, Sheng L, Chen G. et al. Human treated dentin matrix as a natural scaffold for complete human dentin tissue regeneration. Biomaterials. 2011;32:4525–38. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alqahtani Q, Zaky S, Patil A, Beniash E, Ray H, Sfeir C. Decellularized swine dental pulp tissue for regenerative root canal therapy. J Dent Res. 2018;97:1460–67. doi: 10.1177/0022034518785124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang C, Narayanan R, Alapati S, Ravindran S. Exosomes as biomimetic tools for stem cell differentiation: Applications in dental pulp tissue regeneration. Biomaterials. 2016;111:103–15. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen F, Sun H, Lu H, Yu Q. Stem cell-delivery therapeutics for periodontal tissue regeneration. Biomaterials. 2012;33:6320–44. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morsczeck C, Reichert T. Dental stem cells in tooth regeneration and repair in the future. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18:187–96. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2018.1402004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao Z, Hu L, Liu G, Wei F, Liu Y, Liu Z. et al. Bio-root and implant-based restoration as a tooth replacement alternative. J Dent Res. 2016;95:642–9. doi: 10.1177/0022034516639260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morsczeck C, Gotz W, Schierholz J, Zeilhofer F, Kuhn U, Mohl C. et al. Isolation of precursor cells (PCs) from human dental follicle of wisdom teeth. Matrix Biol. 2005;24:155–65. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ten Cate AR. The development of the periodontium-a largely ectomesenchymally derived unit. Periodontol 2000. 1997;13:9–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yokoi T, Saito M, Kiyono T, Iseki S, Kosaka K, Nishida E. et al. Establishment of immortalized dental follicle cells for generating periodontal ligament in vivo. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;327:301–11. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0257-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang B, Chen G, Li J, Zou Q, Xie D, Chen Y. et al. Tooth root regeneration using dental follicle cell sheets in combination with a dentin matrix - based scaffold. Biomaterials. 2012;33:2449–61. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo W, He Y, Zhang X, Lu W, Wang C, Yu H. et al. The use of dentin matrix scaffold and dental follicle cells for dentin regeneration. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6708–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo X, Yang B, Sheng L, Chen J, Li H, Xie L. et al. CAD based design sensitivity analysis and shape optimization of scaffolds for bio-root regeneration in swine. Biomaterials. 2015;57:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gronthos S, Mankani M, Brahim J, Robey PG, Shi S. Postnatal human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13625–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240309797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seo BM, Miura M, Gronthos S, Bartold PM, Batouli S, Brahim J. et al. Investigation of multipotent postnatal stem cells from human periodontal ligament. Lancet. 2004;364:149–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16627-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Fang D, Yamaza T, Seo BM, Zhang C. et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated functional tooth regeneration in swine. PloS one. 2006;1:e7–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Q, Shi S, Liu Y, Uyanne J, Shi Y, Shi S. et al. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from human gingiva are capable of immunomodulatory functions and ameliorate inflammation-related tissue destruction in experimental colitis. J Immunol. 2009;183:7787–98. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsubara T, Suardita K, Ishii M, Sugiyama M, Igarashi A, Oda R. et al. Alveolar bone marrow as a cell source for regenerative medicine: differences between alveolar and iliac bone marrow stromal cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:399–409. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miura M, Gronthos S, Zhao M, Lu B, Fisher LW, Robey PG. et al. SHED: stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5807–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937635100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu X, Jin L, Ma P, Fan Z, Wang S. Allogeneic stem cells from deciduous teeth in treatment for periodontitis in miniature swine. J Periodontol. 2014;85:845–51. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.130254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaukua N, Chen M, Guarnieri P, Dahl M, Lim ML, Yucel-Lindberg T. et al. Molecular differences between stromal cell populations from deciduous and permanent human teeth. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:59. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0056-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao X, Shen Z, Guan M, Huang Q, Chen L, Qin W. et al. Immunomodulatory role of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth on periodontal regeneration. Tissue Eng Part A. 2018;24:1341–53. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2018.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu J, Cao Y, Xie Y, Wang H, Fan Z, Wang J. et al. Periodontal regeneration in swine after cell injection and cell sheet transplantation of human dental pulp stem cells following good manufacturing practice. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7:130. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0362-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xuan K, Li B, Guo H, Sun W, Kou X, He X. et al. Deciduous autologous tooth stem cells regenerate dental pulp after implantation into injured teeth. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:eaaf3227. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf3227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee HS, Jeon M, Kim SO, Kim SH, Lee JH, Ahn SJ. et al. Characteristics of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED) from intact cryopreserved deciduous teeth. Cryobiology. 2015;71:374–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2015.10.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arora V, Arora P, Munshi A. Banking stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED): saving for the future. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2009;33:289–94. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.33.4.y887672r0j703654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinez Saez D, Sasaki RT, Neves AD, da Silva MC. Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth: a growing literature. Cells Tissues Organs. 2016;202:269–80. doi: 10.1159/000447055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pispa J, Thesleff I. Mechanisms of ectodermal organogenesis. Dev Biol. 2003;262:195–205. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo W, Gong K, Shi H, Zhu G, He Y, Ding B. et al. Dental follicle cells and treated dentin matrix scaffold for tissue engineering the tooth root. Biomaterials. 2012;33:1291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu G, Deng Z, Fan X, Ma Z, Sun Y, Ma D. et al. Odontogenic potential of mesenchymal cells from hair follicle dermal papilla. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:583–9. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park CH, Rios HF, Jin Q, Sugai JV, Padial-Molina M, Taut AD. et al. Tissue engineering bone-ligament complexes using fiber-guiding scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2012;33:137–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosa V, Zhang Z, Grande R, Nör J. Dental pulp tissue engineering in full-length human root canals. J Dent Res. 2013;92:970–5. doi: 10.1177/0022034513505772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guan J, Simon A, Prescott M, Menendez J, Liu F, Wang F. et al. Autophagy in stem cells. Autophagy. 2013;9:830–49. doi: 10.4161/auto.24132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boya P, Codogno P, Rodriguez-Muela N. Autophagy in stem cells: repair, remodelling and metabolic reprogramming. Development. 2018;145:dev146506. doi: 10.1242/dev.146506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taghipour Z, Karbalaie K, Kiani A, Niapour A, Bahramian H, Nasr-Esfahani MH. et al. Transplantation of undifferentiated and induced human exfoliated deciduous teeth-derived stem cells promote functional recovery of rat spinal cord contusion injury model. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:1794–802. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yukiko S-W, Wataru K, Masashi O, Takamasa K, Kenichi O, Kohei S. et al. Peripheral nerve regeneration by secretomes of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24:2687–99. doi: 10.1089/scd.2015.0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inoue T, Sugiyama M, Hattori H, Wakita H, Wakabayashi T, Ueda M. Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous tooth-derived conditioned medium enhance recovery of focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:24–9. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jarmalavičiūtė A, Tunaitis V, Pivoraitė U, Venalis A, Pivoriūnas A. Exosomes from dental pulp stem cells rescue human dopaminergic neurons from 6-hydroxy-dopamine-induced apoptosis. Cytotherapy. 2015;17:932–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang J, Wang X, Sun Z, Wang X, Yang H, Shi S. et al. Stem cells from human-exfoliated deciduous teeth can differentiate into dopaminergic neuron-like cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:1375–83. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tian Y, Bai D, Guo W, Li J, Zeng J, Yang L. et al. Comparison of human dental follicle cells and human periodontal ligament cells for dentin tissue regeneration. Regen Med. 2015;10:461–79. doi: 10.2217/rme.15.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang G, Li F, Zhao X, Ma Y, Li Y, Lin M. et al. Functional and biomimetic materials for engineering of the three-dimensional cell microenvironment. Chem Rev. 2017;117:12764–850. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang J, Yamato M, Kohno C, Nishimoto A, Sekine H, Fukai F. et al. Cell sheet engineering: recreating tissues without biodegradable scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6415–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwata T, Washio K, Yoshida T, Ishikawa I, Ando T, Yamato M. et al. Cell sheet engineering and its application for periodontal regeneration. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2015;9:343–56. doi: 10.1002/term.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang J, Zhang R, Shen Y, Xu C, Qi S, Lu L. et al. Recent advances in cell sheet technology for periodontal regeneration. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014;9:162–73. doi: 10.2174/1574888x09666140213150218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ishikawa I, Iwata T, Washio K, Okano T, Nagasawa T, Iwasaki K. et al. Cell sheet engineering and other novel cell-based approaches to periodontal regeneration. Periodontol 2000. 2009;51:220–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dan H, Vaquette C, Fisher A, Hamlet S, Xiao Y, Hutmacher D. et al. The influence of cellular source on periodontal regeneration using calcium phosphate coated polycaprolactone scaffold supported cell sheets. Biomaterials. 2014;35:113–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.09.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aubin J, Liu F, Malaval L, Gupta A. Osteoblast and chondroblast differentiation. Bone. 1995;17:77S–83S. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00183-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang ZH, Zhang XJ, Dang NN, Ma ZF, Xu L, Wu JJ. et al. Apical tooth germ cell-conditioned medium enhances the differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells into cementum/periodontal ligament-like tissues. J Periodontal Res. 2009;44(2):199–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2008.01106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nanci A, Bosshardt DD. Structure of periodontal tissues in health and disease. Periodontol 2000. 2006;40:11–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang L, Liu B, Cha JY, Yuan G, Kelly M, Singh G. et al. Mechanoresponsive properties of the periodontal ligament. J Dent Res. 2016;95:467–75. doi: 10.1177/0022034515626102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Padovano JD, Ravindran S, Snee PT, Ramachandran A, Bedran-Russo AK, George A. DMP1-derived peptides promote remineralization of human dentin. J Dent Res. 2015;94:608–14. doi: 10.1177/0022034515572441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li W, Chen L, Chen Z, Wu L, Feng J, Wang F. et al. Dentin sialoprotein facilitates dental mesenchymal cell differentiation and dentin formation. Sci Rep. 2017;7:300. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00339-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim S, Turnbull J, Guimond S. Extracellular matrix and cell signalling: the dynamic cooperation of integrin, proteoglycan and growth factor receptor. J Endocrinol. 2011;209:139–51. doi: 10.1530/JOE-10-0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fortunati D, Reppe S, Fjeldheim A, Nielsen M, Gautvik V, Gautvik K. Periostin is a collagen associated bone matrix protein regulated by parathyroid hormone. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rios H, Ma D, Xie Y, Giannobile W, Bonewald L, Conway S. et al. Periostin is essential for the integrity and function of the periodontal ligament during occlusal loading in mice. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1480–90. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu J, Zhu S, Heng B, Dissanayaka W, Zhang C. TGF-β1-induced differentiation of SHED into functional smooth muscle cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8:10. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0459-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim J, Kim G, Kim J, Pyeon H, Lee J, Lee G. et al. Angiogenic capacity of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth with human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Mol Cells. 2016;39:790–6. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2016.0131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Popova D, Jacobsson SO. A fluorescence microplate screen assay for the detection of neurite outgrowth and neurotoxicity using an antibody against βIII-tubulin. Toxicol In Vitro. 2014;28:411–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Middeldorp J, Boer K, Sluijs J, De Filippis L, Encha-Razavi F, Vescovi A. et al. GFAPdelta in radial glia and subventricular zone progenitors in the developing human cortex. Development. 2010;137:313–21. doi: 10.1242/dev.041632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gonzalez-Martinez T, Perez-Piñera P, Díaz-Esnal B, Vega J. S-100 proteins in the human peripheral nervous system. Microsc Res Tech. 2003;60:633–8. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Popova D, Jacobsson S. A fluorescence microplate screen assay for the detection of neurite outgrowth and neurotoxicity using an antibody against βIII-tubulin. Toxicol In Vitro. 2014;28:411–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rudert M. Histological evaluation of osteochondral defects: consideration of animal models with emphasis on the rabbit, experimental setup, follow-up and applied methods. Cells Tissues Organs. 2002;171:229–40. doi: 10.1159/000063125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li J, Parada C, Chai Y. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of tooth root development. Development. 2017;144:374–84. doi: 10.1242/dev.137216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cho M, Garant P. Development and general structure of the periodontium. Periodontol 2000. 2000;24:9–27. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2000.2240102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Palmer R, Lumsden A. Development of periodontal ligament and alveolar bone in homografted recombinations of enamel organs and papillary, pulpal and follicular mesenchyme in the mouse. Arch Oral Biol. 1987;32:281–9. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(87)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nowwarote N, Pavasant P, Osathanon T. Role of endogenous basic fibroblast growth factor in stem cells isolated from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. Arch Oral Biol. 2015;60:408–15. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Annibali S, Cristalli MP, Tonoli F, Polimeni A. Stem cells derived from human exfoliated deciduous teeth: a narrative synthesis of literature. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:2863–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figure.