Abstract

This study examined whether sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) inattention (IN) symptoms demonstrated cross-setting invariance and unique associations with symptom and impairment dimensions across settings (i.e., home SCT and ADHD-IN uniquely predicting school symptom and impairment dimensions, and vice versa). Mothers, fathers, primary teachers, and secondary teachers rated SCT, ADHD-IN, ADHD-hyperactivity/impulsivity (HI), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), anxiety, depression, academic impairment, social impairment, and peer rejection dimensions for 585 Spanish third-grade children (53% boys). Within-setting (i.e., mothers and fathers; primary and secondary teachers) and cross-setting (i.e., home and school) invariance was found for both SCT and ADHD-IN. From home to school, higher levels of home SCT predicted lower levels of school ADHD-HI and higher levels of school academic impairment after controlling for home ADHD-IN, while higher levels of home ADHD-IN predicted higher levels of school ADHD-HI, ODD, anxiety, depression, academic impairment, and peer rejection after controlling for home SCT. From school to home, higher levels of school SCT predicted lower levels of home ADHD-HI and ODD and higher levels of home anxiety, depression, academic impairment, and social impairment after controlling for school ADHD-IN, while higher levels of school ADHD-IN predicted higher levels of home ADHD-HI, ODD, and academic impairment after controlling for school SCT. Although SCT at home and school was able to uniquely predict symptom and impairment dimensions in the other setting, SCT at school was a better predictor than ADHD-IN at school of psychopathology and impairment at home. Findings provide additional support for SCT’s validity relative to ADHD-IN.

Keywords: sluggish cognitive tempo, ADHD, attention deficit disorder, cross-setting validity

The sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) construct has been of interest to researchers for several decades (Becker, Marshall, & McBurnett, 2014). Initially researchers viewed this problem of attention as a symptom dimension that might improve the validity of the attention-deficit/hyperactivity (ADHD) subtypes, especially the ADHD predominantly inattentive subtype. Given research generally failed to demonstrate that the SCT symptom dimension could improve the validity of ADHD subtypes (e.g., Willcutt et al., 2014), research shifted to the study of the SCT symptom dimension in its own right. This new research on SCT has primarily focused on the question of whether the SCT symptom dimension has internal and external validity, especially relative to the ADHD-inattention (IN) symptom dimension (Becker, Leopold et al., 2015), with accumulating findings leading investigators to suggest SCT may be its own psychiatric disorder (Barkley, 2014) or a construct of transdiagnostic utility (Becker, Leopold et al., 2015).

The SCT construct is characterized by inconsistent alertness, slow thinking/behavior, and drowsiness (Becker, 2013). Research also appears close to the identification of a common set of SCT symptoms (Becker, Leopold et al., 2015). Traditional psychometric procedures, for example, have recently resulted in the development of two self-report measures of SCT (Barkley, 2012; Becker, Luebbe, & Joyce, 2015) as well as several parent and teacher SCT rating scales (Barkley, 2013; Lee, Burns, Snell, & McBurnett, 2014; McBurnett et al., 2014; Penny, Waschbusch, Klein, Corkum, & Eskes, 2009; Willcutt et al., 2014). The SCT symptoms on these measures are largely the same (Barkley, 2014), thus allowing for a summary of the internal and external validity of the SCT construct (Becker, Leopold et al., 2015). We now note the most central results from Becker and colleagues’ (2015) meta-analysis on the internal and external validity of SCT to indicate how the current study makes a unique contribution to these findings.

Internal and External Validity of the SCT Symptom Dimension

Cross-sectional research indicates the SCT dimension is different from the ADHD-IN dimension (Barkley, 2012, 2013; Becker, Langberg, et al., 2014; Becker, Luebbe et al., 2014; Burns, Servera, Bernad, Carrillo, & Cardo, 2013; Garner et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2014; McBurnett et al., 2014; Penny et al., 2009; Willcutt et al., 2014). This cross-sectional research also indicates that (1) the SCT dimension differs from anxiety and depression dimensions; (2) the SCT dimension has a negative (or nonsignificant) relationship with externalizing problems after controlling for ADHD-IN whereas ADHD-IN has a positive relationship with externalizing problems after controlling for SCT; and (3) the SCT dimension still predicts academic and social impairment even after controlling for ADHD-IN. These findings have been replicated in four (6- to 24-months) longitudinal studies (Becker, 2014; Bernad, Servera, Grases, Collado, & Burns 2014; Bernad, Servera, Becker, & Burns, 2015; Servera, Bernad, Carrillo, Collado, & Burns, 2015), with SCT also demonstrating invariance and stability over a ten-year period (Leopold et al., 2016).

Since the negative (or nonsignificant) association between SCT and externalizing behaviors when controlling for ADHD-IN involves a suppression effect (Kline, 2016, p. 36), it is useful to explain the importance of this effect for the validity of SCT in more detail. While both SCT and ADHD-IN dimensions show a positive first-order relationship (correlation) with externalizing problems, SCT and ADHD-IN show opposite relationships with externalizing problems (negative for SCT and positive for ADHD-IN) after controlling for the other (i.e., a double dissociation, Barkley, 2014). More specifically, variance in SCT that was independent of ADHD-IN shows a negative relationship with externalizing problems while variance in ADHD-IN that was independent of SCT shows a positive relationship with externalizing problems. Importantly, this finding has clear clinical implications. For instance, Becker, Luebbe et al. (2014) found that, when controlling for ADHD symptoms, SCT symptoms predicted fewer time-outs administered due to aggressive or dysregulated behavior in children admitted to an acute psychiatric inpatient unit. As noted by Barkley (2014), “[t]his represents an important demonstration of a double dissociation essential to arguing that SCT is a distinct disorder from ADHD and not a proxy for it or subtype of it” (p. 117). At this point, however, it remains unclear how SCT should be optimally conceptualized (Becker & Barkley, in press; Becker, Leopold et al., 2015), underscoring the importance of additional research examining the validity of the SCT construct.

Cross-Setting External Validity of SCT Symptom Dimension relative to ADHD-IN Symptom Dimension

Although extant studies support the validity of SCT (Becker, Leopold et al., 2015), none of these studies directly evaluated SCT’s validity across settings. Two studies have examined cross-rater effects between parents and teachers of adolescents with ADHD (Becker & Langberg, 2014; Langberg et al., 2014). These studies found parent-rated SCT to predict metacognitive executive functioning (EF) deficits and overall academic impairment as rated by teachers, but teacher-rated SCT did not significantly predict EF deficits or academic impairment as rated by parents (Becker & Langberg, 2014; Langberg et al., 2014). However, these studies were specific to two domains of functioning (i.e., daily life EF and academics), did not focus specifically on cross-setting validity (e.g., analyses were not consistent across settings which limits the cross-setting conclusions that can be drawn), and included only a small sample of adolescents diagnosed with ADHD. It thus remains almost entirely unknown if SCT in one setting (home or school) predicts psychopathology and impairment in the other setting independent of ADHD-IN.

Information on the cross-setting external validity of SCT symptom dimension relative to ADHD-IN symptom dimension is important for several reasons. First, if SCT has unique and different correlates relative to ADHD-IN across settings (i.e., home to school and school to home), such across setting validity would provide much stronger support for the theoretical and clinical importance of SCT (e.g., SCT as not a setting-bound clinical phenomenon and has cross-setting occurrence and impairment aspects similar to ADHD). Such a result would also establish the external validity of SCT as being source independent (i.e., parent ratings of SCT predicting teacher ratings of impairment; teacher ratings of SCT predicting parent ratings of impairment). Second, such cross-setting validity would suggest the importance of the assessment of SCT in both home and school settings as is the current recommendation for the assessment of ADHD (e.g., American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry guidelines). Third, a cross-setting validity study with parents providing ratings in the home and teachers in the school could also indicate if either set of ratings has more validity than the other (e.g., who is the best judge of the occurrence of SCT?). Fourth, with two sources in the home (mothers and fathers) and two sources in the school (primary teachers and secondary teachers), it is possible to determine the invariance of the SCT construct within and across settings (i.e., is the SCT construct the same within and across settings?). These four reasons are why a cross-setting validity study can further determine the theoretical and clinical importance of SCT.

Objectives of the Study

The study involved a secondary and primary objective. The secondary objective was to replicate previous research by examining the associations of SCT and ADHD-IN symptom dimensions with other symptom and impairment dimensions within the same setting (i.e., within the home and within the school associations). The primary objective was to conduct the first examination of the associations of SCT and ADHD-IN dimensions from one setting with symptom and impairment dimensions in the other setting (i.e., home to school and school to home). Ratings by mothers, fathers, primary teachers, and secondary teachers of Spanish third grade children were used to investigate associations of SCT and ADHD-IN dimensions with other symptom and impairment dimensions within and across home and school settings. We now describe the hypotheses associated with each objective.

Secondary objective: Within-setting associations of SCT and ADHD-IN symptom dimensions with other symptom and impairment dimensions.

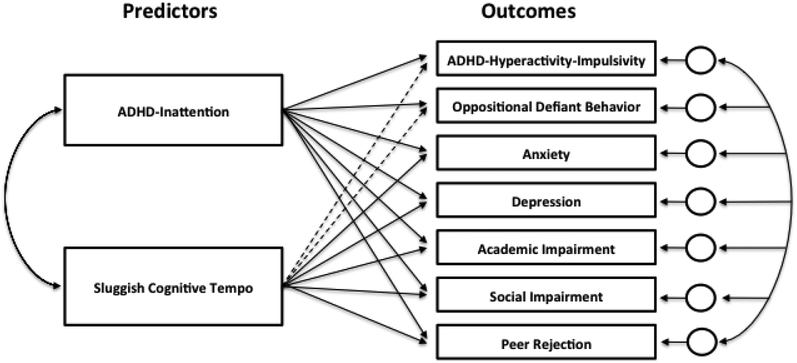

The first hypothesis was that higher levels of SCT and ADHD-IN would be bivariately associated with higher levels of ADHD-HI, ODD, anxiety, depression, academic impairment, social impairment, and peer rejection. The second hypothesis was that ADHD-IN would have a stronger bivariate association than SCT with ADHD-HI and ODD while ADHD-IN and SCT would have equal bivariate associations with anxiety, depression, academic impairment, social impairment, and peer rejection. The third hypothesis dealt with the unique associations of SCT and ADHD-IN with the other measures. Higher levels of SCT were expected to predict lower levels of ADHD-HI and ODD and higher levels of anxiety, depression, academic impairment, social impairment, and peer rejection after controlling for ADHD-IN, while higher levels of ADHD-IN were expected to predict higher levels of all psychopathology (including ADHD-HI and ODD) and impairment dimensions after controlling for SCT. Figure 1 shows the path analytic model for this analysis (i.e., all the outcomes were regressed on the two predictors simultaneously using the robust maximum likelihood estimator). These results would replicate and extend earlier within-setting findings (e.g., Barkley, 2013; Becker, 2014; Becker, Langberg et al., 2014; Bernad et al., 2014; Burns et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2014; Lee, Burns, & Becker, in press; Servera et al., 2015).

Figure 1.

Path analytic model for the within (home to home, school to school) and across (home to school, school to home) setting analyses. Manifest variables (mean scores) used in the model. Dashed lines represent regression coefficients expected to be negative (suppression). Error terms were allowed to correlate.

Primary objective: Cross-setting associations of SCT and ADHD-IN symptom dimensions with other symptom and impairment dimensions.

The first across-setting hypothesis was the same as the first within-setting hypothesis (higher scores on SCT and ADHD-IN in one setting would be bivariately associated with higher scores on ADHD-HI, ODD, anxiety, depression, academic impairment, social impairment, and peer rejection in the other setting). The second across-setting hypothesis was also the same as the second within-setting hypothesis (ADHD-IN would have a stronger bivariate association than SCT with ADHD-HI and ODD across setting with ADHD-IN and SCT being equally associated with anxiety, depression, academic impairment, social impairment, and peer rejection across settings). The third across-setting hypothesis was the same as the third within-setting hypothesis. More specifically, we wanted to determine if the unique effects of SCT and ADHD-IN within settings (home and school) would be the same across settings (home to school and school to home). Finally, as a more stringent test of this third hypothesis, any significant across setting unique effects were further evaluated by also controlling for the within setting effects of SCT and ADHD-IN (e.g., would school SCT still uniquely predict home symptom and impairment measures even after controlling home SCT and home ADHD-IN in addition to school ADHD-IN?).

This study provides the first rigorous test of the cross-setting validity of SCT. Results supporting the cross-setting hypotheses would indicate that SCT is not a source-bound phenomenon (and earlier findings cannot be only attributed to within-rater variance), nor a setting-bound clinical phenomenon. As such, findings from this study have important theoretical (e.g., pervasiveness across settings) and clinical (e.g., assessment of SCT) implications for the study of SCT.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

The participants were mothers, fathers, primary teachers, and secondary teachers of 585 (53% boys) third grade children from 22 randomly selected schools on Majorca (Spain) and eight additional schools from Madrid. The eight schools from Madrid were included to increase sample size given the expectation of participant loss over assessments (resources only allowed the recruitment of 22 schools on Majorca). Primary teachers were the children’s main instructors with secondary teachers being responsible for more specific subjects (English, Catalan language, physical education, and music). The current assessment represented the third assessment with prior assessments in first (n = 758) and second grades (n = 718; Bernad et al., 2014, 2015; Burns et al., 2013; Servera et al., 2015 for studies on assessments one and two).

For third grade assessment, 504 mothers, 460 fathers, 63 primary teachers, and 57 secondary teachers participated in the study. Each primary teacher rated an average of 8.92 (SD = 4.38, n = 561) children and each secondary teacher rated an average of 8.96 (SD = 4.21, n = 508) children. The approximate age of children was nine years with little variation with approximately 90% of the children Caucasian and 10% North African (ethnicity was not collected on individual children with these percentages representing the demographics of the 30 schools). A cover letter was given to parents and with parental written approval a similar cover letter was given to the teachers. Written informed consent was obtained from teachers as well. The protocol was approved by the IRB of the University of the Balearic Islands.

Measures

Child and Adolescent Disruptive Behavior Inventory (CADBI; Burns, Lee, et al., 2014).

The participants completed the parent and teacher versions of the CADBI. The CADBI measures SCT (eight symptoms), ADHD-IN (nine symptoms), ADHD-HI (nine symptoms), ODD toward adults (e.g., argues with adults; eight symptoms), ODD toward peers (e.g., argues with peers; eight symptoms), anxiety (six symptoms), depression (six symptoms), academic impairment (four items: completion of homework, reading skills, arithmetic skills, and writing skills), and social impairment (four items: quality of interactions with parents [teacher], quality of interactions with adults other than parents [other adults at school], quality of interactions with brothers and sisters [peers in the classroom], and quality of interactions with other children in the home and community [peers outside of the classroom at school].

The symptoms were rated on a 6-point frequency of occurrence scale (i.e., almost never [never or about once per month], seldom [about once per week], sometimes [several times per week], often [about once per day], very often [several times per day], and almost always [many times per day]). A 7-point scale was used for the four academic and four social impairment items (severe difficulty, moderate difficulty, slight difficulty, average performance [average interactions] for grade level, slightly above average, moderately above average, and excellent performance [excellent interactions] for grade level). The academic and social impairment items were reversed keyed so higher scores represent higher impairment. Mothers and fathers were instructed to base their ratings on the child’s behavior at home and in the community (not school) and make their ratings independently. Primary and secondary teachers were instructed to based their ratings on the child’s behavior at school and also asked to make their ratings independently.

The wording of the eight SCT symptoms is shown in Table 1. The wording of the ADHD and ODD symptoms was based on the DSM-5 descriptions. The two ODD scales were combined into a single ODD scale. Table 1 in Bernad et al. (2015) shows the six anxiety and six depression symptoms. Earlier studies support the reliability (i.e., high reliability coefficients [range: .76 to .98], good inter-rater factor correlations [mothers with fathers range: .67 to .86; primary teachers with secondary teachers range: .53 to .79], and good stability coefficients for one month [.67 to .85], six weeks [.75 to .90], and 12 months [.57 to .78]) as well as the validity of the scores from the CADBI scales (Belmar et al., 2015; Bernad et al., 2014, 2015; Burns, Servera, Bernad, Carrillo, & Geiser, 2014; Burns, Walsh, et al., 2013; Khadka, Burns, & Becker, 2015; Lee et al., 2014; Lee, Burns, Beauchaine, & Becker, 2015; Lee, Burns, & Becker, in press; Servera et al., 2015). Lower values were for anxiety with the SCT and ADHD-IN scale values being similar.

Table 1.

Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Items on Parent Scale

|

Note. The phrase “homework and home activities” was replaced with classroom activities on the teacher scale.

Dishion Social Acceptance Scale (DSAS; Dishion, 1990).

The DSAS is a three-item teacher rating scale that assesses a child’s peer rejection. Primary and secondary teachers rated the proportion of classmates who “dislike,” “like,” and “ignore” the child on a 5-point scale (very few [less than 25%]; some [25 to 49%]; about half [50%]; many [51 to 75%]; and almost all [greater than 75%]). The three items were used to create a peer rejection measure (“like” item reversed). Earlier studies report reliability coefficients (omega values) from .66 to .83 (M = .75, SD = .07) and a teacher with teacher factor correlations of .76 for the measure (Belmar et al., 2015; Bernad et al., 2015; Khadka et al., 2015). Additional studies support the validity of the DSAS, including studies demonstrating significant associations with peer sociometric nominations (Dishion, 1990; Lee & Hinshaw, 2006) and sensitivity in differences between children with and without ADHD (Lahey et al., 2004).

Analytic Strategy

Estimation.

The analyses used the Mplus statistical software (Version 7.4, Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). For analyses on individual items, items were treated as ordered-categorical manifest variables (i.e., robust weighted least squares estimator [WLSMV]). For analyses with summary scores (i.e., mean scores on the measures, see Figure 1), the estimator was the robust maximum likelihood estimator (i.e., MLR).

Clustering.

Given the children were clustered within classes (teachers), the Mplus type = complex option was used to take into account the clustering. All the analyses were repeated with the clustering unit being schools and results were unchanged. The within and across setting path analytic analyses were also repeated as two level regression analyses with the same results.

Model fit and criteria for invariance tests.

For invariance analyses on SCT and ADHD-IN symptoms across sources, global model fit was evaluated with the comparative fit index (CFI, study criterion ≥ .95, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI, study criterion ≥ .95), and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA, study criterion ≤ .05). If the decrease in CFI was less than 0.01 and TLI and RMSEA showed little change, then constraints on like-item loadings and like-item thresholds were considered invariant (Little, 2013, chap. 5). The purpose of these invariance analyses was to determine if our two predictors (SCT and ADHD-IN) had the same measurement properties for the four sources.

Item level and summary score analyses.

A series of confirmatory factor analyses were first performed on the individual items on the CADBI and DAS. The purpose was to provide the justification to use summary scores on the measures as manifest variables in the path analytic models to test the within and across setting hypotheses (i.e., the number of items were too many to use items as manifest variables given the sample size). The item level analyses are first described followed by a description of the summary score analyses.

Convergent and discriminant validity of SCT and ADHD-IN symptoms.

The first set of analyses applied an exploratory two-factor model to SCT and ADHD-IN symptoms. These analyses allowed the SCT symptoms to cross-load on the ADHD-IN factor and the ADHD-IN symptoms to cross-load on the SCT factor. These four analyses (i.e., a separate analysis for mothers, fathers, primary teachers, and secondary teachers) sought to identify SCT symptoms with convergent validity (high loadings on the SCT factor) and discriminant validity (higher loadings on the SCT factor than the ADHD-IN factor). The goal here was to identify a common set of SCT symptoms with convergent validity as well as discriminant validity the ADHD-IN factor for the four sources. The same procedure was applied to ADHD-IN symptoms. A common set of SCT symptoms with convergent validity and discriminant validity with ADHD-IN was necessary to meaningfully test the within and across setting predictions.

Reliability of measures.

The second set analyses used confirmatory factor analytic (CFA) procedures to determine the reliability coefficients (omega values) for the measures for each source separately, mothers and fathers combined, and primary teachers and secondary teachers combined. For the combined analyses, mothers’ and fathers’ ratings were combined to created one SCT and one ADHD-IN factor for home with the same procedure used to create one SCT and one ADHD-IN factor for school (i.e., the SCT factor for the home was defined by the SCT items for mothers and fathers [i.e., the ten SCT items assigned to a single SCT factor] and the ADHD-IN factor for the home was defined by the IN items for mothers and fathers; the SCT factor for the school was defined by the SCT items for primary and secondary teachers and the ADHD-IN factor for the school was defined by the IN items for primary and secondary teachers). The third set of analyses used CFA procedures to determine the correlations for the same factors (i.e., inter-rater reliability) for mothers with fathers, primary teachers with secondary teachers, and home with school settings. For the home with school analysis, the home and school ratings were combined in the same manner as for the second set of analyses.

Invariance of SCT and ADHD-IN symptoms across sources.

The fourth and fifth sets of analyses used CFA procedures to evaluate the invariance of like-item loadings and like-item thresholds for SCT and ADHD-IN symptoms between mothers and fathers as well as primary teachers and secondary teachers (two separate analyses). The sixth set of analyses evaluated the invariance of like-item loadings and like-item thresholds between home and school. This invariance analysis involved one SCT and one ADHD-IN factor for the home and one SCT and one ADHD-IN factor for the school. Like-item loadings and thresholds were constrained equal within and across settings for this analysis.

First-order associations of SCT and ADHD-IN measures with other symptom and impairment measures within and across settings.

The seventh set of analyses calculated the correlations of SCT and ADHD-IN measures with ADHD-HI, ODD, anxiety, depression, academic impairment, social impairment, and peer rejection measures within and across settings. These correlations were based on summary scores (mean scores on the measures).

Unique associations of SCT and ADHD-IN measures with other symptom and impairment measures within and across settings.

The eighth set of analyses determined the unique associations of SCT and ADHD-IN measures with ADHD-HI, ODD, anxiety, depression, academic impairment, social impairment and peer rejection measures within and across settings. Path analytic models were used to obtain the partial standardized regression coefficients (i.e., the outcomes were simultaneously regressed on the predictors, see Figure 1). These analyses also used summary scores as manifest variables (mean scores on the measures).

Across setting unique associations of SCT and ADHD-IN with symptom and impairment measures controlling for within setting SCT and ADHD-IN.

These analyses determined if any of the across setting unique effects of SCT and ADHD-IN remained significant after controlling for SCT and ADHD-IN within setting as well (i.e., regression of home symptom and impairment measures on school SCT and school ADHD-IN also controlling for home SCT and home ADHD-IN; regression of school symptom and impairment measures on home SCT and home ADHD-IN also controlling for school SCT and school ADHD-IN). These analyses allowed a very stringent test of the unique associations of SCT and ADHD-IN across settings.

Results

Missing Information

For the item level analyses, covariance coverage for mothers, fathers, primary teachers, and secondary teachers was 83% to 100%, 83% to100%, 92% to 100%, and 76% to 100%, respectively. The analyses at the item level used the WLSMV estimator, with this estimator using a pairwise approach to missing information. For the correlational and path analytic analyses with manifest variables (mean scores on the measures), covariance coverage for home to home, school to school, home to school, and school to home analyses was 84% to 100%, 94% to 100%, 82% to 97%, and 71% to 97%, respectively. These analyses used the MLR estimator, with this estimator using a full information maximum likelihood approach to missing data.

Convergent and Discriminant Validity of SCT and ADHD-IN Symptoms

For ratings by mothers, SCT symptoms 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 showed convergent validity (loadings higher than 0.57 on the SCT factor) and discriminant validity (loadings lower that .33 on the ADHD-IN factor, see Table 1 for SCT symptoms). For fathers, all eight SCT symptoms showed convergent (loadings higher than .73 on the SCT factor) and discriminant validity (loadings less than .21 on the ADHD-IN factor). For primary teachers, SCT symptoms 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 showed convergent validity (loadings higher than .57 on the SCT factor) and discriminant validity (loadings less than .33 on the ADHD-IN factor). For secondary teachers, SCT symptoms 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 showed convergent (loadings higher than .69 on the SCT factor) and discriminant (loadings less than .31 on the ADHD-IN factor) validity. For mothers and fathers, all nine ADHD-IN symptoms showed convergent (loadings greater than .61 on the ADHD-IN factor) and discriminant validity (loadings less than .30 on the SCT factor). For primary and secondary teachers, all nine ADHD-IN symptoms also showed convergent (loadings higher than .80 on the ADHD-IN factor) and discriminant validity (loadings less than .20 on the SCT factor).

Operationalization of the SCT Construct

To determine if SCT has unique associations with other symptom and impairment dimensions relative to ADHD-IN, SCT symptoms must have convergent validity (high loadings on the SCT factor) and, even more importantly, discriminant validity with the ADHD-IN factor (higher loadings on the SCT factor than the ADHD-IN factor). In other words, if SCT symptoms do not show discriminant validity with the ADHD-IN factor, it is impossible to know if the failure to find unique correlates for SCT relative to ADHD-IN is due to a lack of such unique correlates or failure of SCT symptoms to have discriminant validity with the ADHD-IN factor. In addition, given our purpose to test for unique correlates of SCT within and across settings, the SCT measure had to be defined by the same SCT symptoms for mothers, fathers, primary teachers, and secondary teachers. The SCT measure was thus defined by the five symptoms (i.e., 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8, Table 1) that showed convergent and discriminant validity for all four sources.

Reliability Coefficients

Internal consistency.

Table 2 shows reliability coefficients (omega values) for the measures for the four sources. These values ranged from good to excellent. Table 2 also shows the reliability coefficients for combining mothers with fathers and combining primary and second teachers. The values range from .86 to .96 for mothers combined with fathers and .88 to .94 for primary teachers combined with secondary teachers. The single set of measures for home and school thus showed excellent reliability.

Table 2.

Reliability Coefficients (Omega Values) and Inter-Rater Factor Correlations for Sources and Settings

| Omega Values | Inter-Rater Factor Correlations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | Fathers | Home | Tl | T2 | School | Mothers with Fathers | Tl with T2 | Home with School | |

| SCT | .89 | .88 | .93 | .93 | .94 | .94 | .80 | .74 | .38 |

| ADHD-IN | .94 | .94 | .96 | .97 | .97 | .97 | .85 | .82 | .49 |

| ADHD-HI | .93 | .92 | .96 | .96 | .96 | .97 | .81 | .79 | .49 |

| ODD | .95 | .95 | .96 | .97 | .97 | .97 | .78 | .66 | .39 |

| Anxiety | .78 | .74 | .86 | .85 | .91 | .88 | .74 | .53 | .21 |

| Depression | .84 | .84 | .90 | .90 | .93 | .92 | .85 | .68 | .30 |

| Academic impairment | .92 | .92 | .95 | .95 | .96 | .96 | .88 | .79 | .65 |

| Social impairment | .89 | .93 | .94 | .95 | .95 | .92 | .76 | .60 | .22 |

| Peer rejection | --- | --- | --- | .82 | .76 | .89 | --- | .76 | --- |

Note. Confirmatory factor analytic procedures were used to calculate the omega values along with the inter-rater factor correlations. Only teachers completed the peer rejection measure. All correlations significant were significant at p < .001. T1 = primary teachers; T2 = secondary teachers; SCT = sluggish cognitive tempo; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; IN = inattention; HI = hyperactivity/impulsivity; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder.

Inter-rater reliability.

Table 2 also shows the inter-rater factor correlations for mothers with fathers, primary teachers with secondary teachers, and home (mothers combined with fathers) with school (primary teachers combined with secondary teaches). The within-setting factor correlations were all fairly substantial (i.e., mothers with fathers range: .74 [anxiety] to .88 [academic impairment]; primary teachers with secondary teachers range: .53 [anxiety] to .82 [ADHD-IN]). The home with school factor correlations for the same factors ranged from .22 for social impairment to .65 for academic impairment.

Invariance of SCT and ADHD-IN Symptoms

Mothers with fathers.

The baseline model yielded a good fit across mothers and fathers, χ2 (330) = 610, CFI = .991, TLI = .990, and RMSEA = .041 [.036, .046]. The model with the constraints on like-item loadings and thresholds did not result in a meaningful decrement in fit, χ2 (411) = 759, CFI = .989, TLI = .990, and RMSEA = .041 [.036, .046]. The SCT and ADHD-IN factor means also did not differ significantly between mothers and fathers (ps > .05).

Primary teachers with secondary teachers.

The baseline model also resulted in a good fit across primary and secondary teachers, χ2 (330) = 771, CFI = .994, TLI = .993, and RMSEA = .049 [.044, .053]. The model with the constraints on like-item loadings and thresholds did not result in a meaningful decrement in fit, χ2 (416) = 912, CFI = .993, TLI = .994, and RMSEA = .046 [.042, .050]. The SCT and ADHD-IN factor means also did not differ significantly between primary and secondary teachers (ps > .05).

Home with school.

The baseline model resulted in a good fit across home and school, χ2 (1464) = 2970, CFI = .978, TLI = .977, and RMSEA = .042 [.040, .044]. The model with the constraints on like-item loadings and thresholds within and across settings did not result in a meaningful decrement in fit, χ2 (1691) = 3172, CFI = .978, TLI = .980, and RMSEA = .039 [.037, .041]. The SCT and ADHD-IN factor means were significantly (ps < .05) higher in the home than school setting (i.e., SCT: Difference = 0.33, SE = .13, Cohen’s latent d = 0.27; ADHD-IN: Difference = 0.68, SE = .12, Cohen’s latent d = 0.55).

Measures for Within and Across Setting Analyses

Given the results from the above analyses (i.e., high reliability coefficients for a single set measures for home and school, high factor correlations for the same factors for mothers with fathers and primary teachers with secondary teachers, and invariance of like-item loadings and thresholds for SCT and ADHD-IN items within settings), summary scores (mean scores on the measures) were used for the path analytic models to test the within and across setting hypotheses (Figure 1). As noted earlier, mean summary scores were used because the number of items was too large relative to the number of children for latent variable regression analyses. Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics for the home and school measures.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics for Home (Mothers and Fathers) and School (Primary Teachers and Secondary Teachers) Measures

| Home | School | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| SCT | 0.67 | 0.73 | 1.45 | 2.13 | 0.63 | 0.85 | 1.50 | 1.66 |

| ADHD-IN | 1.03 | 0.91 | 1.20 | 1.07 | 0.71 | 0.93 | 1.58 | 2.08 |

| ADHD-HI | 0.93 | 0.91 | 1.38 | 1.57 | 0.53 | 0.85 | 2.40 | 6.51 |

| ODD | 0.84 | 0.70 | 1.45 | 2.35 | 0.34 | 0.57 | 2.82 | 9.91 |

| Anxiety | 0.66 | 0.62 | 1.48 | 2.69 | 0.33 | 0.51 | 2.31 | 6.92 |

| Depression | 0.26 | 0.42 | 3.07 | 12.45 | 0.29 | 0.54 | 3.06 | 12.07 |

| Academic impairment | 3.83 | 1.27 | 0.12 | −0.80 | 3.76 | 1.37 | 0.13 | −0.93 |

| Social impairment | 3.87 | 1.16 | 0.25 | −0.36 | 3.43 | 1.02 | 0.49 | 1.59 |

| Peer rejection | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.67 | 0.67 | 1.59 | 3.09 |

Note. Symptoms ratings (SCT, ADHD-IN, ADHD-HI, ODD, anxiety, and depression) were on a 0 to 5 scale. Academic and social impairment ratings were on a 0 to 6 scale with peer rejection on a 1 to 5 scale. Only teachers completed the peer rejection measure. SCT = sluggish cognitive tempo; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; IN = inattention; HI = hyperactivity/impulsivity; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder.

Within and Across Setting SCT and ADHD-IN Correlations with Symptom and Impairment Dimensions

Table 4 shows the within and across setting correlations of SCT and ADHD-IN with ADHD-HI, ODD, anxiety, depression, academic impairment, social impairment, and peer rejection. Higher levels of SCT and ADHD-IN were significantly (ps < .05) associated with higher levels of ADHD-HI, ODD, anxiety, depression, academic impairment, social impairment, and peer rejection within and across settings with one exception. School ADHD-IN was not related to home anxiety (p > .05). In addition, as predicted, ADHD-IN showed a stronger relationship than SCT with ADHD-HI and ODD within and across settings (ps < .05). Also, as predicted, SCT and ADHD-IN were equally associated (ps > .05) with anxiety, depression, academic impairment, social impairment, and peer rejection within and across settings with two exceptions. Within the school setting, ADHD-IN was more strongly associated than SCT with peer rejection (p = .045) and for school to home SCT was more strongly associated than ADHD-IN with anxiety (p = .04). The Mplus model constraint procedure was used to determine if the correlations differed significantly.

Table 4.

Within and Across Setting Pearson Correlations of Sluggish Cognitive Tempo and ADHD-IN with ADHD-HI, ODD, Anxiety, Depression, Academic Impairment, Social Impairment and Peer Rejection

| Predictors | HI | ODD | Anxiety | Depression | Academic Impairment | Social Impairment | Peer Rejection | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | SE | r | SE | r | SE | r | SE | r | SE | r | SE | r | SE | |

| Home Outcomes | ||||||||||||||

| SCThome | 0.44** | 0.05 | 0.41** | 0.04 | 0.33** | 0.06 | 0.46** | 0.06 | 0.48** | 0.04 | 0.28** | 0.04 | --- | --- |

| INhome | 0.65** | 0.04 | 0.57** | 0.04 | 0.29** | 0.06 | 0.44** | 0.05 | 0.52** | 0.04 | 0.26** | 0.04 | --- | --- |

| SCTschool | 0.22** | 0.05 | 0.19** | 0.05 | 0.13** | 0.06 | 0.30** | 0.07 | 0.43** | 0.04 | 0.23** | 0.05 | --- | --- |

| INschool | 0.35** | 0.05 | 0.28** | 0.05 | 0.07ns | 0.05 | 0.24** | 0.06 | 0.40** | 0.04 | 0.22** | 0.06 | --- | --- |

| School Outcomes | ||||||||||||||

| SCTschool | 0.10* | 0.04 | 0.12* | 0.06 | 0.10* | 0.05 | 0.23** | 0.06 | 0.37** | 0.04 | 0.26** | 0.05 | 0.26** | 0.05 |

| INhome | 0.31** | 0.05 | 0.21** | 0.05 | 0.16** | 0.05 | 0.26** | 0.05 | 0.40** | 0.03 | 0.30** | 0.04 | 0.29** | 0.06 |

| SCTschool | 0.34** | 0.04 | 0.36** | 0.05 | 0.49** | 0.05 | 0.66** | 0.03 | 0.62** | 0.03 | 0.37** | 0.04 | 0.47** | 0.04 |

| INschool | 0.59** | 0.04 | 0.50** | 0.05 | 0.46** | 0.05 | 0.63** | 0.04 | 0.62** | 0.03 | 0.41** | 0.03 | 0.54** | 0.04 |

Note. SCT = sluggish cognitive tempo; IN = inattention; HI = hyperactivity/impulsivity; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder. Peer rejection was only a school setting measure.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Within and Across Setting Unique Associations of SCT and ADHD-IN with Symptom and Impairment Dimensions

Table 5 shows the within and across setting unique associations (standardized partial regression coefficients) of SCT and ADHD-IN with the symptom and impairment dimensions. The coefficients represent the associations of SCT with the symptom and impairment dimensions after controlling for ADHD-IN and the association of ADHD-IN with the symptom and impairment dimensions after controlling for SCT. Table 6 shows the amount of variance in the symptom and impairment measures accounted for jointly by SCT and ADHD-IN (the R2 values).

Table 5.

Within and Across Setting Unique Associations of Sluggish Cognitive Tempo and ADHD-IN with ADHD-HI, ODD, Anxiety, Depression, Academic Impairment, Social Impairment and Peer Rejection

| Predictors | ADHD-HI | ODD | Anxiety | Depression | Academic Impairment | Social Impairment | Peer Rejection | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| Prediction of Home Outcomes with Home SCT and Home ADHD-IN Predictors | ||||||||||||||

| SCThome | −0.14* | 0.07 | −0.05ns | 0.08 | 0.28* | 0.09 | 0.31** | 0.09 | 0.21* | 0.07 | 0.18* | 0.07 | --- | --- |

| INhome | 0.75** | 0.07 | 0.61** | 0.08 | 0.07ns | 0.09 | 0.20* | 0.08 | 0.36** | 0.06 | 0.12+ | 0.07 | --- | --- |

| Prediction of School Outcomes with School SCT and School ADHD-IN Predictors | ||||||||||||||

| SCTschool | −0.45** | 0.10 | −0.19+ | 0.11 | 0.34** | 0.10 | 0.45** | 0.08 | 0.36** | 0.05 | 0.12+ | 0.07 | 0.08ns | 0.10 |

| INschool | 0.96** | 0.10 | 0.66** | 0.11 | 0.18+ | 0.10 | 0.25* | 0.09 | 0.32** | 0.05 | 0.31** | 0.07 | 0.47** | 0.09 |

| Prediction of School Outcomes with Home SCT and Home ADHD-IN Predictors | ||||||||||||||

| SCThome | −0.33** | 0.09 | −0.10ns | 0.11 | −0.07ns | 0.10 | 0.07ns | 0.11 | 0.17* | 0.07 | 0.07ns | 0.07 | 0.09ns | 0.09 |

| INhome | 0.56** | 0.10 | 0.29* | 0.10 | 0.21* | 0.09 | 0.21* | 0.09 | 0.27** | 0.06 | 0.25** | 0.06 | 0.22* | 0.10 |

| Prediction of Home Outcomes with School SCT and School ADHD-IN Predictors | ||||||||||||||

| SCTschool | −0.24* | 0.09 | −0.16+ | 0.09 | 0.23* | 0.09 | 0.30* | 0.10 | 0.32** | 0.07 | 0.15* | 0.07 | --- | --- |

| INschool | 0.55** | 0.08 | 0.41** | 0.09 | 0.12ns | 0.08 | −0.0lns | 0.08 | 0.14* | 0.08 | 0.09ns | 0.09 | --- | --- |

Note. SCT = sluggish cognitive tempo; IN = inattention; ADHD-HI = hyperactivity/impulsivity; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder. Peer rejection was only a school setting measure.

p < 0.10.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Table 6.

Variance Accounted for Values (R2) for the Within and Across Setting Regression of ADHD-HI, ODD, Anxiety, Depression, Academic Impairment, Social Impairment and Peer Rejection on SCT and ADHD-IN

| ADHD-HI | ODD | Anxietv | Depression | Academic Impairment | Social Impairment | Peer Reiection | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | SE | R2 | SE | R2 | SE | R2 | SE | R2 | SE | R2 | SE | R2 | SE |

| Prediction of Home Outcomes with Home SCT and Home ADHD-IN Predictors | |||||||||||||

| .43 | .05 | .32 | .05 | .11 | .04 | .23 | .05 | .29 | .04 | .08 | .02 | --- | --- |

| Prediction of School Outcomes with School SCT and School ADHD-IN Predictors | |||||||||||||

| .41 | .06 | .26 | .05 | .25 | .05 | .46 | .04 | .42 | .04 | .17 | .03 | .29 | .04 |

| Prediction of School Outcomes with Home SCT and Home ADHD-IN Predictors | |||||||||||||

| .14 | .05 | .05 | .02 | .03ns | .02 | .07 | .03 | .17 | .03 | .09 | .03 | .09 | .03 |

| Prediction of Home Outcomes with School SCT and School ADHD-IN Predictors | |||||||||||||

| .14 | .03 | .09 | .03 | .02ns | .02 | .09 | .04 | .19 | .03 | .05 | .03 | --- | --- |

Note. SCT = sluggish cognitive tempo; IN = inattention; ADHD-HI = hyperactivity/impulsivity; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder. Peer rejection was only a school setting measure. Peer rejection measures were only available for the school setting. All correlations were significant at p < .05 unless noted as non-significant (ns).

Home-to-home analyses.

Higher levels of home SCT predicted significantly (ps < .05) lower levels of home ADHD-HI and higher levels of home anxiety, depression, academic impairment, and social impairment after controlling for home ADHD-IN, while higher levels of home ADHD-IN predicted significantly (ps < .05) higher levels of home ADHD-HI, ODD, depression, and academic impairment after controlling for SCT. As predicted, home SCT was not uniquely related to home ODD. In contrast to expectations, home ADHD-IN was not uniquely related to home anxiety (p > .10) and only marginally related to social impairment (p = .068).

School-to-school analyses.

Higher levels of school SCT predicted significantly (ps < .001) lower levels of school ADHD-HI and higher levels of school anxiety, depression, and academic impairment after controlling for school ADHD-IN, while higher levels of school ADHD-IN predicted significantly (ps < .05) higher levels of school ADHD-HI, ODD, depression, academic impairment, social impairment, and peer rejection after controlling for school SCT. There was a tendency, however, for higher levels of school SCT to uniquely predict lower (as expected) levels of school ODD (p = .08) and higher levels of school social impairment (p = .10). There was also a tendency for higher levels of school ADHD-IN to uniquely predict higher levels of school anxiety (p = .07).

Home-to-school analyses.

Higher levels of home SCT predicted significantly (ps < .05) lower levels of school ADHD-HI and higher levels of school academic impairment after controlling for home ADHD-IN, while higher levels of home ADHD-IN predicted significantly (ps < .05) higher levels of school ADHD-HI, ODD, anxiety, depression, academic impairment, social impairment, and peer rejection after controlling for home SCT. Home SCT was not uniquely related to school ODD, anxiety, depression, social impairment, and peer rejection.

School-to-home analyses.

Higher levels of school SCT predicted significantly (ps < .05) lower levels of home ADHD-HI and higher levels of home anxiety, depression, academic impairment, and social impairment after controlling for school ADHD-IN, while higher levels of school ADHD-IN predicted significantly (ps < .05) higher levels of home ADHD-HI and ODD after controlling for school SCT. There was also a tendency for higher levels of school SCT to uniquely predict lower levels of home ODD (p = .08) and for higher levels of school ADHD-IN to uniquely predict higher levels of home academic impairment (p = .07). School ADHD-IN was not uniquely related to home anxiety, depression, and social impairment.

Across Setting Unique Associations of SCT and ADHD-IN with Symptom and Impairment Measures Controlling for Within Setting SCT and ADHD-IN

These two analyses sought to determine if the significant unique across-setting associations of SCT and ADHD-IN would remain significant even after also controlling for the within settings effects of SCT and ADHD-IN. For the first analysis, home SCT still predicted significantly lower levels of school ADHD-HI (β = −0.24, SE = 0.08, p = .003) and higher levels of school academic impairment (β = 0.12, SE = 0.06, p = .03) even after controlling for home ADHD-IN, school SCT, and school ADHD-IN, while home ADHD-IN still predicted significantly higher levels of school ADHD-HI (β = 0.21, SE = 0.09, p = .02) even after controlling for home SCT, school SCT, and school ADHD-IN.

For the second analysis, higher scores on school SCT still predicted lower scores on home ADHD-HI (β = −0.22, SE = 0.07, p = .001) and ODD (β = −0.16, SE = 0.08, p = .04) and higher scores on home anxiety (β = 0.16, SE = 0.08, p = .05), depression (β = 0.23, SE = 0.09, p = .01), and academic impairment (β = 0.26, SE = 0.08, p = .001) even after controlling for school ADHD-IN, home SCT, and home ADHD-IN, while school ADHD-IN still predicted higher levels of home ADHD-HI (β = 0.22, SE = 0.07, p = .001) after controlling for school SCT, home SCT, and home ADHD-IN.

Discussion

Research increasingly supports the internal and external validity of SCT (Becker, Leopold, et al., 2015). A limitation of this research, however, involves the general absence of any information on the cross-setting external validity of SCT relative to ADHD-IN. In other words, does parent-rated SCT in the home predict teacher-rated symptom and impairment dimensions at school independent of parent-rated ADHD-IN in the home? In a similar manner, does teacher-rated SCT in the school predict parent-rated symptom and impairment dimensions independent of teacher-rated ADHD-IN in the school? If SCT has unique correlates relative to ADHD-IN across settings, such results would significantly strengthen the validity of the SCT construct with important theoretical and clinical implications. While our primary purpose was to evaluate the cross-setting external validity of SCT relative to ADHD-IN, we conducted invariance analyses prior to conducting the cross-setting analyses, and in line with our secondary purpose we examined within-setting associations in order to replicate findings from previous within-setting studies. We summarize the within-setting findings first, then the cross-settings findings, followed by a discussion of the theoretical and clinical implications of the cross-setting and invariance and external validity findings.

Within-Setting External Validity of SCT

Within home and school settings, higher levels of SCT was associated with lower levels of ADHD-HI and ODD (or was no longer related to ODD) along with higher levels of anxiety, depression, academic impairment, and social impairment after controlling for ADHD-IN. Teacher-rated SCT was not, however, uniquely associated with teacher-rated peer rejection after controlling for ADHD-IN. These results replicated and extended the findings from the first and second grade studies with these children (Bernad et al., 2014; Burns et al., 2013; Servera et al., 2015) and also were consistent with other studies on SCT’s external validity (Becker, Leopold et al., 2015). Although other aspects of within setting external validity of SCT relative to ADHD-IN still need to be investigated (see Becker, Leopold et al., 2015), our within-setting results add to a growing body of research supporting the external validity of SCT.

Cross-Setting External Validity of SCT

From home to school, higher levels of parent-rated SCT were associated with lower levels of teacher-rated ADHD-HI and higher levels of teacher-rated academic impairment after controlling for ADHD-IN. These home-to-school significant effects for SCT even remained significant after controlling for teacher-rated SCT and ADHD-IN as well as parent-rated ADHD-IN. SCT in the home was thus uniquely related to lower levels of ADHD-HI and higher levels of academic impairment in the school even after controlling for teachers’ own ratings of SCT and ADHD-IN in addition to parents’ ratings of ADHD-IN.

From school to home, higher levels of teacher-rated SCT were associated with lower levels of parent-rated ADHD-HI and ODD along with higher levels of parent-rated anxiety, depression, academic impairment, and social impairment after controlling teacher-rated ADHD-IN. Importantly, with the exception of social impairment, all of these significant unique effects remained significant after controlling for not only teacher-rated ADHD-IN but also parent-rated SCT and ADHD-IN. Teacher-rated SCT thus predicted important outcomes at home even after controlling for parents’ own ratings of SCT and ADHD-IN in addition to teachers’ ratings of ADHD-IN.

Theoretical and Clinical Implications of Cross-Setting Invariance and External Validity of SCT

The cross-setting invariance and external validity results for SCT relative to ADHD-IN have important theoretical and clinical implication for the usefulness of the SCT construct. First, although most SCT studies to date have relied on parent and teacher ratings (Becker, Leopold et al., 2015), this is the first study to demonstrate that parent and teacher ratings of SCT are invariant. Our findings demonstrate that the SCT construct is indeed equivalent as measured using parent and teacher ratings, extending previous studies demonstrating invariance across males and females (Becker, Langberg et al., 2014) and temporal invariance for parent ratings of SCT over a 10-year period (Leopold et al., 2016). These findings are critically important in order to make sure findings from studies using parent and/or teacher ratings are comparable at the construct level.

Moreover, our cross-setting findings indicate that, similarly to ADHD, SCT is not a setting-bound clinical phenomenon but rather demonstrates cross-setting occurrence and associations with impairment. The cross-setting results also indicate that the external validity of SCT is source independent, an outcome also similar to the characteristics of ADHD. Although additional research is needed in order to establish evidence-based guidelines for assessing SCT, the cross-setting results of this study indicate that the clinical assessment of SCT should likely include information from home and school settings, another outcome similar to the recommendations for the assessment of ADHD. Where SCT and ADHD may part ways, however, is in regards to self-report of SCT (Becker, Luebbe, et al., 2015). Although children’s self-report of ADHD is not considered evidence-based best practice, there is some indication that children can – and should – report on their own experience of SCT symptoms (Becker, Luebbe, et al., 2015). This is consistent with guidelines for assessing internalizing symptoms (Klein, Dougherty, & Olino, 2005; Silverman & Ollendick, 2005), and internalizing symptoms are strongly associated with SCT (Becker, Leopold et al., 2015). We were unable to include children’s self-report of SCT in this study, and this is an important priority for future research.

Nevertheless, the current study makes an important contribution in demonstrating that, overall, teachers’ ratings of SCT are more clearly associated with parents’ ratings of psychopathology and impairment dimensions than vice versa. To be clear, after controlling for ADHD-IN, parent-rated SCT did remain significantly associated with two domains of teacher-rated functioning (lower ADHD-HI and higher academic impairment), but teacher-rated SCT was significantly associated with five domains of parent-rated functioning (lower ADHD-HI and higher anxiety, depression, academic impairment, and social impairment). These findings suggest that when teachers do observe SCT in children, those children are especially likely to experience poorer functioning not only in school, but also at home. Although parent-rated SCT remained significantly negatively associated with teacher-rated ADHD-HI and positively associated with teacher-rated academic impairment, much clearer evidence was found for teacher-rated SCT being significantly associated with functioning in the home setting. Why might this be?

Interestingly, although studies clearly demonstrate that both parents and teachers are able to identify a set of SCT symptoms that are distinct from ADHD-IN symptoms (see Becker, Leopold et al., 2015, for a review), two factor analytic studies indicate that teachers may be especially able to distinguish SCT from ADHD-IN (Garner et al., 2010; McBurnett et al., 2001). Our study aligns with and extends these findings to the domain of external validity. Teachers observe children across a range of academic tasks and social situations, and children with elevated rates of SCT are especially likely to struggle in the larger peer group activities that are central to academic and social demands of elementary school given that SCT is associated with lower rates of leadership (Marshall et al., 2014) and higher rates of loneliness (Becker, Luebbe et al., 2015), shyness (Becker et al., 2013), and peer withdrawal (Carlson & Mann, 2002; Marshall et al., 2014; Willcutt et al., 2014). Thus, teachers may be more likely than parents to notice the reticent and socially isolated behaviors that are characteristic of SCT. In line with this possibility, two studies found SCT symptoms to be associated with poorer social skills when teacher ratings were used, but not parent ratings (Bauermeister et al., 2012; McBurnett et al., 2014). We do not intend to suggest that parent rating of SCT are either invalid or not useful – indeed, a sizable body of research suggests quite the contrary (Becker, Leopold et al., 2015) – but our results do speak to the apparent value and importance of incorporating and considering teacher ratings when assessing for SCT.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

Strengths of the study included the use of four sources. We also used advanced statistical modeling to examine within- and across-setting associations across levels of analysis, including bivariate associations, regression models controlling for within-setting ADHD-IN symptoms, and regression models controlling for both within-setting ADHD-IN symptoms in addition to across-setting SCT and ADHD-IN symptoms. This latter analysis is a stringent test of associations and bolsters confidence in our findings. Nevertheless, the cross-sectional design, broad measures of impairment, and limited age range were each a limitation. Longitudinal studies are needed in addition to studies that include individuals from various developmental periods (e.g., adolescents, adults) as well as other external validity domains (e.g., grades, sociometric status). As noted above, it is particularly important to determine whether parents, teachers, or children themselves (Becker, Luebbe et al., 2015) are optimal reporters of SCT (i.e., a study with ratings by mothers, fathers, and teachers in conjunction self-ratings by children and adolescents to determine the relative strength of each source’s rating within and across source symptom and impairment measures). Studies that take into account these limitations would further advance of our understanding of SCT (see also Becker, Leopold et al., 2015).

Conclusion

This is the first study to specifically evaluate the invariance and cross-setting impact of SCT and ADHD-IN symptoms on other psychopathology dimensions and impairment domains in children. Findings provide important additional support for the external validity of SCT and also point to SCT as observed at school as especially linked to internalizing symptoms and impairment at home. It will be especially important in future studies to use a longitudinal design and to understand better SCT’s link to internalizing symptoms.

Acknowledgments

A Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness grant PSI2011–23254 (Spanish Government) and a predoctoral fellowship co-financed by the European Social Fund and the Balearic Island Government (FPI/1451/2012) supported this research. We thank Cristina Trias and Cristina Solano for their help in data collection.

Contributor Information

G. Leonard Burns, Washington State University.

Stephen P. Becker, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

References

- Barkley RA (2012). Distinguishing sluggish cognitive tempo from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121, 978–990. doi: 10.1037/a0023961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA (2013). Distinguishing sluggish cognitive tempo from ADHD in children and adolescents: Executive functioning, impairment, and comorbidity. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 42, 161–173. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.734259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA (2014). Sluggish cognitive tempo (concentration deficit disorder?): Current status, future directions, and a plea to change the name. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 117–125. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9824-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JJ, Barkley RA, Bauermeister JA, Martínez JV, & McBurnett K (2012). Validity of the sluggish cognitive tempo, inattention, and hyperactivity symptom dimensions: Neuropsychological and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 683–697. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9602-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP (2013). Topical review: Sluggish cognitive tempo: Research findings and relevance for pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38, 1051–1057. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP (2014). Sluggish cognitive tempo and peer functioning in school-aged children: A six-month longitudinal study. Psychiatry Research, 217, 72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, & Barkley RA (in press). Sluggish cognitive tempo. To appear in Zuddas A, Coghill D, & Banaschewski T (Eds.), Oxford Textbook of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Fite PJ, Garner AA, Stoppelbein L, Greening L, & Luebbe AM (2013). Reward and punishment sensitivity are differentially associated with ADHD and sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms in children. Journal of Research in Personality, 47, 719–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2013.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, & Langberg JM (2014). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and sluggish cognitive tempo dimensions in relation to executive functioning in adolescents with ADHD. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 45, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10578-013-0372-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Langberg JM, Luebbe AM, Dvorsky MR, & Flannery AJ (2014). Sluggish cognitive tempo is associated with academic functioning and internalizing symptoms in college students with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70, 388–403. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Leopold DR, Burns GL, Jarrett MA, Langberg JM, Marshall SA, … Willcutt EG (2015). The internal, external, and diagnostic validity of sluggish cognitive tempo: A meta-analysis and critical review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Luebbe AM, Fite PJ, Stoppelbein L, & Greening L (2014). Sluggish cognitive tempo in psychiatrically hospitalized children: Factor structure and relations to internalizing symptoms, social problems, and observed behavioral dysregulation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 49–62. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9719-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Luebbe AM, & Joyce AM (2015). The Child Concentration Inventory (CCI): Initial validation of a child self-report measure of sluggish cognitive tempo. Psychological Assessment, 27, 1037–1052. doi: 10.1037/pas0000083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Marshall SA, & McBurnett K (2014). Sluggish cognitive tempo in abnormal child psychology: An historical overview and introduction to the Special Section. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9825-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmar M, Servera M, Becker SP, & Burns GL (2015). Validity of sluggish cognitive tempo in South America: An initial examination using mother and teacher ratings of Chilean children. Journal of Attention Disorders. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/1087054715597470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernad MM, Servera M, Grases G, Collado S, & Burns GL (2014). A cross-sectional and longitudinal investigation of the external correlates of sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD-IN symptom dimensions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 1225–1236. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9866-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernad MM, Servera M, Becker SP, & Burns GL (2015). Sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD inattention as predictors of externalizing, internalizing, and impairment domains: A 2-year longitudinal study Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0066z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns GL, Lee S, Becker SP, Servera M, & McBurnett K (2014). Child and Adolescent Disruptive Behavior Inventory—Parent and Teacher Versions 5.0. Pullman, WA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Burns GL, Servera M, Bernad MM, Carrillo JM, & Cardo E (2013). Distinctions between sluggish cognitive tempo, ADHD-IN and depression symptom dimensions in Spanish first grade children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 42, 796–808. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.838771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns GL, Servera M, Bernad MM, Carrillo JM, & Geiser C (2014). Ratings of ADHD symptoms and academic impairment by mothers, fathers, teachers, and aides: Construct validity within and across settings as well as occasions. Psychological Assessment, 26, 1247–1258. doi: 10.1037/pas0000008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns GL, Walsh JA, Servera M, Lorenzo-Seva U, Cardo E, & Rodríguez A (2013). Construct validity of ADHD/ODD rating scales: Recommendations for the evaluation of forthcoming DSM-V ADHD/ODD scales. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 15–26. doi: 10.1007/s1082-012-9660-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson CL, & Mann M (2002). Sluggish cognitive tempo predicts a different pattern of impairment in the attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, predominantly inattentive type. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31, 123–129. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3101_14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, (1990). The peer context of troublesome child and adolescent behavior In Leone PE (Ed.), Understanding Troubled and Troubling Youth: Multiple Perspectives (pp. 128–153). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Garner AA, Marceaux JC, Mrug S, Patterson C, & Hodgens B (2010). Dimensions and correlates of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and sluggish cognitive tempo. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 1097–1107. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9436-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khadka G, Burns GL, & Becker SP (2015). Internal and external validity of sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD inattention dimensions with teacher ratings of Nepali children Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s10862-015-9534-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Dougherty LR, & Olino TM (2005). Towards guidelines for evidence-based assessment of depression in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 412–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RA (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Loney J, Kipp H, Ehrhardt A, Lee SS, … Massetti G (2004). Three-year predictive validity of DSM–IV attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children diagnosed at 4–6 years of age. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 2014–2020. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langberg JM, Becker SP, & Dvorsky MR (2014). The association between sluggish cognitive tempo and academic functioning in youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 91–103. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9722-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, & Hinshaw SP (2006). Predictors of adolescent functioning in girls with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): The role of childhood ADHD, conduct problems, and peer status. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35, 356–368. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Burns GL, Beauchaine TP, & Becker SP (2015). Bifactor latent structure of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)/oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) symptoms and first-order latent structure of sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms Psychological Assessment. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/pas0000232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Burns GL, Snell J, & McBurnett K (2014). Validity of the sluggish cognitive tempo symptom dimension in children: Sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD-Inattention as distinct symptom symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 7–19. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9714-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Burns GL, & Becker SP (in press). Towards establishing the transcultural validity of sluggish cognitive tempo: Evidence from a sample of south Korean children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold DR, Christopher ME, Burns GL, Becker SP, Olson RK, & Willcutt EG (2016). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and sluggish cognitive tempo through childhood: Temporal invariance and stability from preschool through ninth grade Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. Advance online publication. doi: 10.111/jcpp.12505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little T (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall SA, Evans SW, Eiraldi RB, Becker SP, & Power TJ (2014). Social and academic impairment in youth with ADHD, predominately inattentive type and sluggish cognitive tempo. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 77–90. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9758-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBurnett K, Pfiffner LJ, & Frick PJ (2001). Symptom properties as a function of ADHD type: An argument for continued study of sluggish cognitive tempo. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29, 207–213. doi: 10.1023/A:1010377530749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBurnett K, Villodas M, Burns GL, Hinshaw SP, Beaulieu A, & Pfiffner LJ (2014). Structure and validity of sluggish cognitive tempo using an expanded item pool in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 37–38. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9801-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th Ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Penny AM, Waschbusch DA, Klein RM, Corkum P, & Eskes G (2009). Developing a measure of sluggish cognitive tempo for children: content validity, factor structure, and reliability. Psychological Assessment, 21, 380–389. doi: 10.1037/a0016600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servera M, Bernad MM, Carrillo JM, Collado S, & Burns GL (2015). Longitudinal correlates of sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD-inattention symptom dimensions with Spanish children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1004680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, & Ollendick TH (2005). Evidence-based assessment of anxiety and its disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 380–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt EG, Chhabildas N, Kinnear M, DeFries JC, Olson RK, Leopold DR, Keenan JM, & Pennington BF (2014). The internal and external validity of sluggish cognitive tempo and its relation with DSM-IV ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 21–35. doi: 10.1007/210802-013-9800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]