Abstract

Paraquat (PQ) is an agricultural chemical used worldwide. As a potential neurotoxicant, PQ adversely affects neurogenesis and inhibits proliferation of neural progenitor cells (NPCs). However, the molecular mechanistic insights of PQ exposure on NPCs remains to be determined. Herein, we determine the extent to which Wnt/β-catenin signaling involved in the inhibition effect of PQ on mouse NPCs from subventricular zone (SVZ). NPCs were treated with different concentrations of PQ (40, 80, and 120 μM). PQ exposure provoked oxidative stress and apoptosis and PQ inhibited cell viability and proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner. Significantly, PQ exposure altered the expression/protein levels of the Wnt pathway genes in NPCs. In addition, PQ reduced cellular β-catenin, p-GSK-3β, and cyclin-D1 and increased the radio of Bax/Bcl2. Further, Wnt pathway activation by treatment with LiCl and Wnt1 attenuated PQ-induced inhibition of mNPCs proliferation. Antioxidant (NAC) treatment alleviated the inhibition of PQ-induced Wnt signaling pathway. Overall, our results suggest significant inhibitory effects of PQ on NPCs proliferation via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Interestingly, our results implied that activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway attenuated PQ-induced autophagic cell death. Our results therefore bring our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of PQ-induced neurotoxicity.

Keywords: Paraquat, Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, Neural progenitor cells, Apoptosis, Proliferation inhibition, Autophagic cell death

1. Introduction

Paraquat (1, 1-dimethyl-4, 4-bipyridium dichloride; PQ) is a worldwide used agricultural chemical, especially in developing countries (Jones et al., 2014). Some studies have shown that PQ may cross the blood brain barrier (BBB) through a neutral amino acid carrier due to it structurally comparable to amino acids (Shimizu et al., 2001; Widdowson et al., 1996). Accumulating evidence suggests that PQ inhibited hippocampal neurogenesis and impaired spatial learning and memory in adult mice (Hogberg et al., 2009; Li et al., 2017). Combined exposure to PQ and Maneb alters transcriptional regulation of neurogenesis-related genes in C57/B6 mice subventricular zone (SVZ) and hippocampus (Desplats et al., 2012). Moreover, our previous in vitro study suggested that PQ could inhibit proliferation and induced apoptosis in human embryonic neural progenitor cells (hNPCs) (Chang et al., 2013). However, the underlying molecular mechanisms of PQ inhibition on NPCs proliferation remain to be determined.

Adult neurogenesis includes critical processes such as proliferation, differentiation, migration, expansion of axons and dendrites, synapse formation, myelination, and apoptosis. More importantly, NPCs proliferation is the fundamental event (Yuan et al., 2015). These processes require the coordinated cellular and molecular events in a spatial and temporal manner. Several growth factors and signal transduction cascades have been implicated in controlling NPC behavior in adult neurogenesis (Desplats et al., 2012). Wnt signal pathway is one of the critical pathways involved in proliferation regulation of NPCs. Wnt ligand binds to Fzd receptor and LRP5/6 (low-density-lipoprotein-related protein 5 or 6) co-receptors to activate signaling. The binding event triggers the recruitment of Dishevelled and Axin to the membrane, and this recruitment causes the dissociation of the destruction complex that is composed of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β), adenomatosis polyposis coli (APC), Axin and casein kinase 1α. This dissociation results in the inhibition of GSK-3β and stabilization of β-catenin. β-catenin’s accumulation and translocation to the nucleus modulate the expression of genes encoding cell cycle protein and apoptosis protein via its binding to transcription factors TCF (T-cell transcription factor)/LEF (lymphoid enhancer-binding factor) (Varela-Nallar and Inestrosa, 2013). Similarly, extensive research has confirmed that Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway critically contributes to the reparation of nigrostriatal DAergic neurons and regulation of adult neurogenesis (L’Episcopo et al., 2011; Shruster et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011).

The generation of ROS and oxidative stress was suggested as one of the primary mechanisms of PQ induced neurotoxicity (Martins et al., 2013), leading to cellular injury signaling and apoptosis in the nervous system (Case et al., 2016; Mitra et al., 2011; Niso-Santano et al., 2010; Yuan et al., 2015). Our previous studies indicated that PQ exposurecaused oxidative stress was involved in hNPCs apoptosis and proliferation inhibition (Chang et al., 2013). On the other hand, as one of the important endogenous antioxidant pathway, autophagy has a neuroprotection effect in neurodegenerative and neurogenesis (Levine and Kroemer, 2008; Meng et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2016). More importantly, autophagy could play a role in cell death under pathological conditions. For example, inhibition of autophagy could prevent the cell death of irradiation-induced neural stem and progenitor cells in the hippocampus of juvenile mouse brain (Wang et al., 2017). Intriguingly, autophagy and apoptosis have been linked by studies demonstrating that ROS can induce apoptosis in neuron cells through activating of GSK-3β, a critical molecular of Wnt signaling pathway and autophagy (Lin et al., 2014; Shin et al., 2006).

Therefore, we hypothesize that Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway involves in the toxicity induced by PQ. We isolated NPCs from C57BL/6J mice SVZ and examined the adverse effects of PQ by treating the NPCs with various concentrations of PQ. Because Wnt pathway plays a critical role in cell proliferation and apoptosis, we primarily focused on alteration of Wnt signaling pathway in PQ-induced injury in NPCs. Our findings demonstrate that PQ provokes oxidative stress, inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis through down-regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Intriguingly, the activation of Wnt pathway is able to dampen autophagic cell death, therefore improving our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of PQ-induced neurotoxicity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. NPCs isolation from SVZ of newborn C57BL/6J mice

Newborn C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Department of Laboratory Animals of Fudan University. All experimental procedures were approved by institutional animal care committee and were conducted in accordance with Fudan University ethical guidelines. Briefly, the SVZ were cut under a microscope as previously described (L’Episcopo et al., 2013). Harvested tissues were incubated in DMEM/F12 medium, containing 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 3 min at 37 °C. After digestion, cells were centrifuged and washed twice with DMEM/F12 (1:1 v/v, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), then cultured as described below.

2.2. Cell culture conditions

The isolated NPCs were seeded in Poly-D-lysine and laminin precoated 3 cm plates in DMEM/F12 medium containing 2% B27 supplement, 1% N2 supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc, Rockford, IL), 10 ng/mL fibroblast growth factor (b-FGF) and 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF) (PeproTech, Rockville, NJ, USA). Then cells were cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2 and refreshed medium every day. Seven days after plating, primary NPCs were treated with ESGRO Complete Accuase (Millipore, USA) to passage to 6 cm plates pre-coated with Poly-D-lysine and laminin. Cells from the 3th passage were used for the following experiments.

2.3. Cell treatments

PQ (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy) dissolved in DPBS was administered at concentrations ranging from 0 to 1000 μM for 24 h when the cells were approximately 70%–80% confluent. To observe the effects of oxidative stress, Wnt signaling pathway and autophagy in 80 μM PQexposed NPCs, N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China), Wnt1 (human recombinant Wnt1 protein, PeproTech, Rockville, NJ, USA) and LiCl (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy), and 3-MA (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy) were selected as intervention of anti-oxidative stress, Wnt pathway activator and anti-autophagy, respectively. The indicated dose of NAC and 3-MA were cultured for 4 h and 1 h apart before 80 μM PQ exposure, while Wnt1 and LiCl were added together with PQ for 24 h.

2.4. Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assayed using the CCK8 kit (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Kumamoto, Japan). Briefly, 3.5 × 105 cells/mL were seeded in a 96-well plate containing a final volume of 100 μL. After confluence of 70%–80%, cells were treated with PQ, PQ + NAC, PQ + Wnt1, PQ + LiCl or PQ+3-MA for 24 h. Then, 10 μL CCK8 was added to each well for 4 h at 37 °C. The absorbance of the samples was read in a SYNERGY microplate reader (BioTek, Vermont, USA) at 490 nm. Cell viability was expressed as a percentage of the absorbance from control cells.

2.5. 5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine incorporation assay and cell proliferation

Cell proliferation was determined by the Edu incorporation assay. In brief, after treatment with PQ, PQ + Wnt1, or PQ + LiCl for the indicated times, 50 μM 5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (Edu) was subjected to NPCs for 2 h. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and Edu visualization was performed using Cell-Light TM EdU kit (Ribobio, Guangzhou, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The azide-conjugated Apollo dye reaction buffer was added to react with the Edu for 30 min. Subsequently, cell nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 for 30 min. Images were acquired with an Olympus microscope system (lx81) and all experiments were executed in triplicate.

2.6. Apoptosis by flow cytometry

Apoptosis was assessed by Annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide (PI) double staining using an Alex Fluor 488 AnnexinV/PI Dead Cell Apoptosis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacture’s protocol. After 24 h PQ, PQ + LiCl, PQ + Wnt1 and PQ+3-MA treatment, NPCs were dissociated and incubated in 300 μL 1 × binding buffer containing 1 μL Annexin V-FITC and 1 μL PI at room temperature for 15 min in the dark. Cells were then measured by flow cytometry (FACS Calibur system, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA).

2.7. Cell cycle analysis

The effect of PQ on cell cycle was determined by flow cytometry. Briefly, cells were treated with PQ, PQ + LiCl, or PQ + Wnt1 for 24 h; harvested and washed with DPBS; and then fixed with 70% ethanol at −20 °C for at least 24 h. Cells were then stained with propidium iodide (PI) and RNaseA staining buffer (BD Biosciences, NJ, USA) for 15 min at 4 °C in the dark. Following, the fluorescence intensity was determined with a FACS Calibur instrument (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and the data obtained were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA).

2.8. Reactive oxygen species by flow cytometry

The conversion of non-fluorescent DCFH-DA to fluorescent DCF was adopted to monitor intracellular ROS production by flow cytometric. Thus, the fluorescence intensity was proportional to the amount of ROS produced by the cells. After treatment with the tested agents as indicated above, cells were detached with Accutase and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min. Subsequently, cells pallet were resuspended with the medium containing 1 μM DCFH-DA (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China) and incubated at 37 °C in the dark for 30 min. The fluorescence was assessed by comparing two fluorescence excitation/emission 485–495 nm/525–530 nm using flow cytometry (FACS Calibur system, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, UAS). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA).

2.9. Transmission electron microscope analysis

Following 24 h of PQ, PQ + Wnt1 and PQ + LiCl treatment, the cells were scraped off and harvested into a 15 mL Eppendorff tube via centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 15 min. After the supernatant was removed, 2.5% glutaraldehyde was slowly added into the tube. Then were sent to Electronic microscope laboratory of Fudan University for detection of autophagic vacuole using JEM-1400 plus electronic microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

2.10. RNA extraction, reverse transcription and q-PCR

Total RNA was extracted with Tripure RNA Isolation Reagent (Roche, Switzerland) from NPCs and reverse transcribed into cDNA with cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. We performed qPCR quantification of mRNA levels for genes belonging to Wnt signaling pathway (Axin1, β-catenin, Dvl2, Fzd1, Fzd4, LEF1, and TCF3), autophagy (Atg5, Beclin1, mTOR, and mTORC1), cell cycles (c-Myc, CyclinD1 (CCND1), and apoptosis (Bax and Bcl2). The mRNA amplifications were conducted using a q-PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vantaa, Finland) according to the previously study (Chang et al., 2013). Data were normalized to housekeeping gene (PPIA) expression. Each sample was done in triplicate and the 2−△△Ct was applied for RNA relative expression quantification. The primers for various amplified genes are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used in RT-PCR.a

| Primer name | Forward (5′−3′) | Reverse (3′−5′) |

|---|---|---|

| PPIA | CATACAGGTCCTGGCATCTTGTC | AGACCACATGCTTGCCATCCAG |

| Axinl | GTCCAGTGATGCTGACACGCTA | GCCCATTGACTTGGATACTCTCC |

| β-catenin | GTTCGCCTTCATTATGGACTGCC | ATAGCACCCTGTTCCCGCAAAG |

| Dvl2 | CCTCATCCTTCAGCAGTGTCAC | CCACAATGGAGATGCCCAGGAA |

| Fzd1 | GTGCTCACGTACCTAGTGGACA | TCCTCCAACAGAAAGCCAGCGA |

| Fzd4 | ACTTTCACGCCGCTCATCCAGT | TCTCAGGACTGGTTCACAGCGT |

| LEF1 | ACTGTCAGGCGACACTTCCATG | GTGCTCCTGTTTGACCTGAGGT |

| TCF3 | CCTCTCATCACCTACAGCAACG | CTGGAGACAGTGGGTAATACGG |

| Bax | AGGATGCGTCCACCAAGAAGCT | TCCGTGTCCACGTCAGCAATCA |

| Bcl2 | CCTGTGGATGACTGAGTACCTG | AGCCAGGAGAAATCAAACAGAGG |

| c-myc | TCGCTGCTGTCCTCCGAGTCC | GGTTTGCCTCTTCTCCACAGAC |

| CyclinDl | GCAGAAGGAGATTGTGCCATCC | AGGAAGCGGTCCAGGTAGTTCA |

| Atg5 | CTTGCATCAAGTTCAGCTCTTCC | AAGTGAGCCTCAACCGCATCCT |

| Beclin1 | CAGCCTCTGAAACTGGACACGA | CTCTCCTGAGTTAGCCTCTTCC |

| mTOR | AGAAGGGTCTCCAAGGACGACT | GCAGGACACAAAGGCAGCATTG |

| mTORC1 | CCACCTTGTCTTCCATCACTCAG | GCAACTGCTGTAGAGACTTTGGG |

Primers sequence were from OriGene Technology (Beijing, China).

2.11. Western blot analysis

After treating the cells with the tested agents as indicated above, the protein extraction and Western blot process were operated as described previously (Chang et al., 2013). The immunoreactive proteins were visualized with Tanon High-sig ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Tanon Shanghai, China) and the density of the bands were quantified using a densitometer system (Syngene G:BOX, UK) and expressed as IOD (integrated optical density). β-Tubulin was used as an internal control for equivalent protein loading and the target protein densitometry values were normalized to expression from the control sample. The antibodies for various proteins are list in Table 2.

Table 2.

Antibodies used in Western blot.

| Antibody | Dilution | Vendor |

|---|---|---|

| β-Tubulin (9F3) Rabbit mAb | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| DVL2 antibody | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| β-catenin antibody | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| Phospho-GSK-3β (Ser9) (5B3) Rabbit mAb | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| GSK-3β (27C10) Rabbit mAb | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| LC3B Antibody | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| phosphor-mTOR (Ser2448) antibody | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| Bax (D3R2M) Rabbit mAb | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| Bcl2 antibody | 1:1000 | Beyotime |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG(H + L) (HRP) | 1:2500 | Abcam |

2.12. Data analysis

All experiments were performed with at least three biological replicates. The data were expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD) of three experiments and statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 19.0 statistic program. All data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA), followed by LSD-t test for variance heterogeneity. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

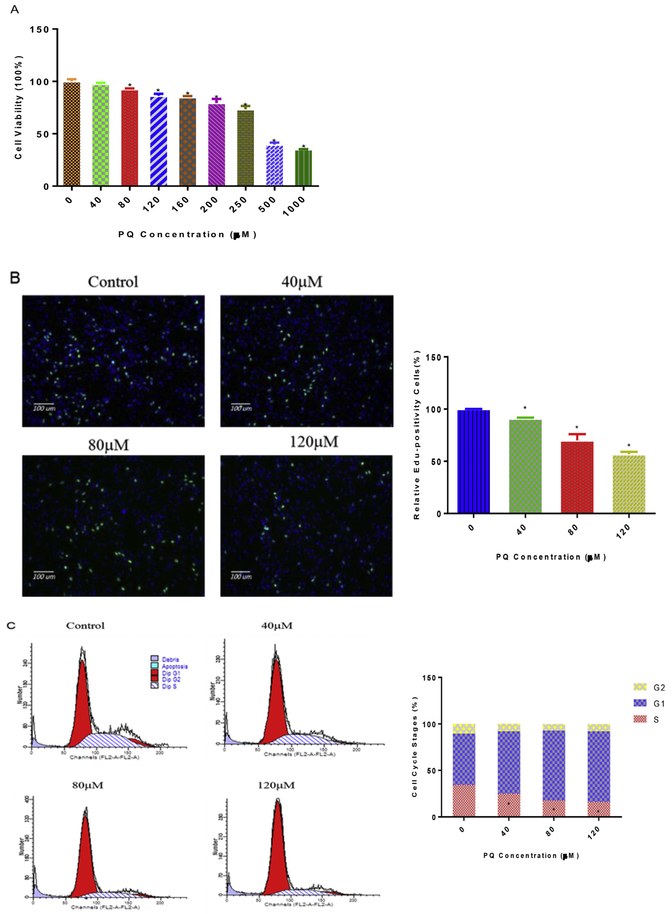

3.1. PQ provokes oxidative stress and apoptosis, and inhibits cell viability and proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner in NPCs

NPCs were treated with PQ at concentrations ranging from 0 to 1000 μM for 24 h. We then assessed the cell viability by CCK8 assay. PQ exposure resulted in a dose-dependent decrease of cell viability in NPCs. At 80 μM PQ treatment, we observed the significant decreases by 5% (Fig. 1A). The IC50 of PQ was calculated as 508 μM, based on the data of CCK8 assay.

Fig. 1.

PQ provokes oxidative stress, apoptosis and inhibits cell viability, proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner in NPCs. Experiments were run in parallel as the protocol describes. Cell viability was measured by CCK8 (A). Cell proliferation was analyzed by Edu and nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue), cells stayed in proliferation were stained with Apollo dye reaction buffer (green) (B) and data were normalized as % control. Cell cycles (C), apoptosis (D) and the production of ROS (E) were measured by flow cytometry, and fluorometrically positive cells were reported as percentage of total cells analyzed. *p < 0.05 compared to control. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

To further characterize PQ-induced toxicity we next examined the effect of PQ on cell proliferation and cell cycle using the Edu incorporation assay and flow cytometry, respectively. NPCs were separately incubated for a 24 h period with PQ (0, 40, 80, 120 μM) (Fig. 1B, C, D). We observed PQ can be a dose dependent manner decreased the number of Edu-positive cells and the number of S-phase cells in NPCs (Fig. 1B and C). In addition, apoptosis was measured with AnnexinV/PI probe by flow cytometry, the proportion of apoptotic cells was increased in the PQ-treated NPCs in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1D).

Because ROS generation and the subsequent oxidative stress are suggested as one of the primary mechanisms for PQ induced neurotoxicity (Drechsel and Patel, 2008), we examined the production of ROS after 24 h treatment of PQ (0, 40, 80, 120 μM) with flow cytometry. We found that PQ provoked a concentration-dependent increase in ROS generation (Fig. 1E).

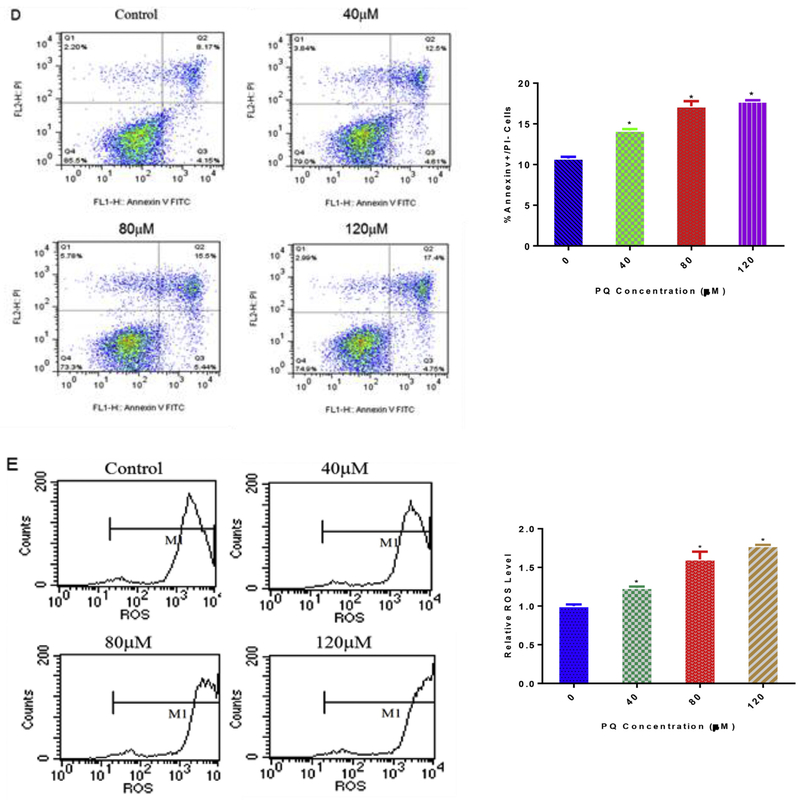

3.2. PQ-induced oxidative stress inhibited Wnt signaling pathway in NPCs

To elucidate the underlying mechanisms of PQ induced cytotoxicity on NPCs, NPCs were treated with 80 μM PQ for 24 h, and cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against GSK-3β, p-(Ser9)-GSK-3β, DVL2, and β-catenin (Table 2). Treatment with PQ reduced the phosphorylated form of GSK-3β, DVL2 and β-catenin. However, pre-incubation with NAC (5 mM), a well-known antioxidant, for 4 h significantly reduced the production of ROS and prevented the reduction in DVL2, β-catenin and p-(Ser9)-GSK-3β expression due to PQ exposure (Fig. 2A and B). These data suggest that PQ-induced oxidative damages on NPCs are probably due to the inhibition of Wnt pathway genes.

Fig. 2.

Cytoprotection of NAC after 4 h pre-incubation period against Wnt/β-catenin pathway suppression elicited by PQ. Flow cytometry analysis of the production of ROS after treatment with PQ (80 μM) and PQ (80 μM)+NAC (5 mM) (A). Western blot were performed using DVL2, β-catenin, p-(Ser9)-GSK-3β and GSK-3β antibodies, and β-Tubulin was used to normalized the Western blots (B). *p < 0.05 compared to control to PQ in the presence of NAC. *#p < 0.05 compared to control and PQ treatment.

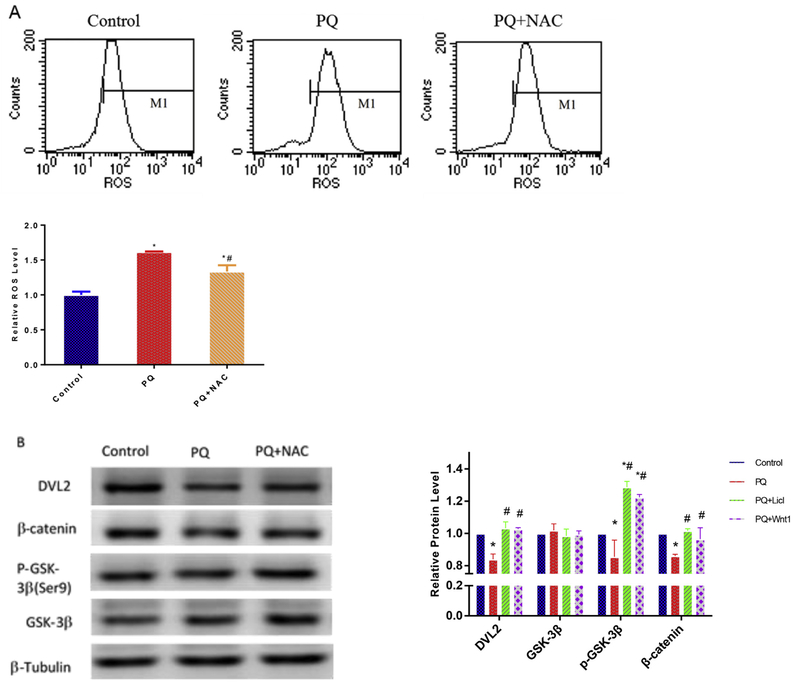

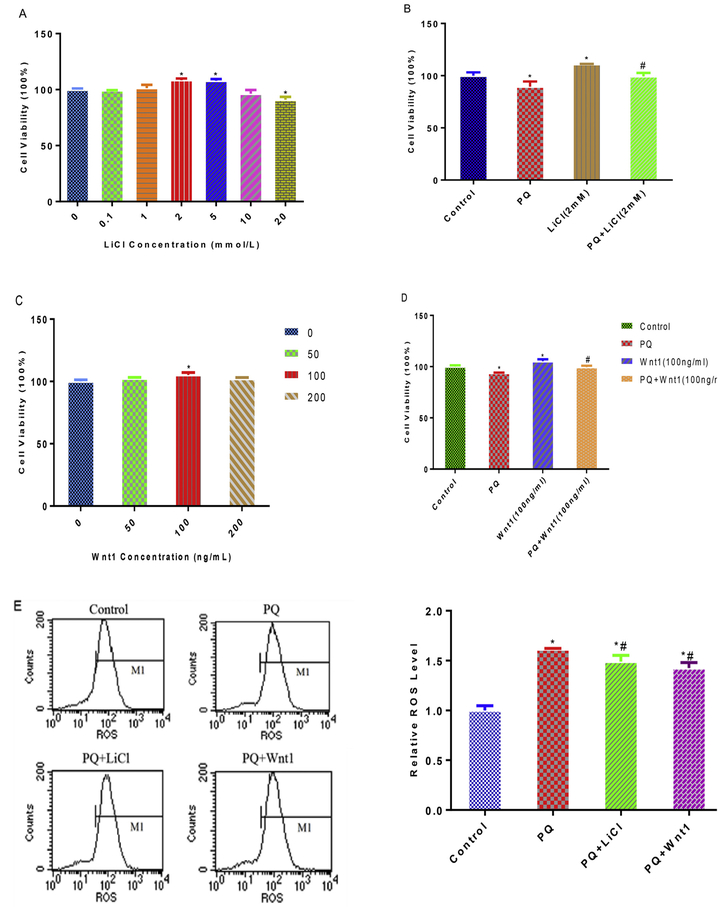

3.3. Activation of the Wnt signaling pathway attenuates PQ-induced toxicity in NPCs

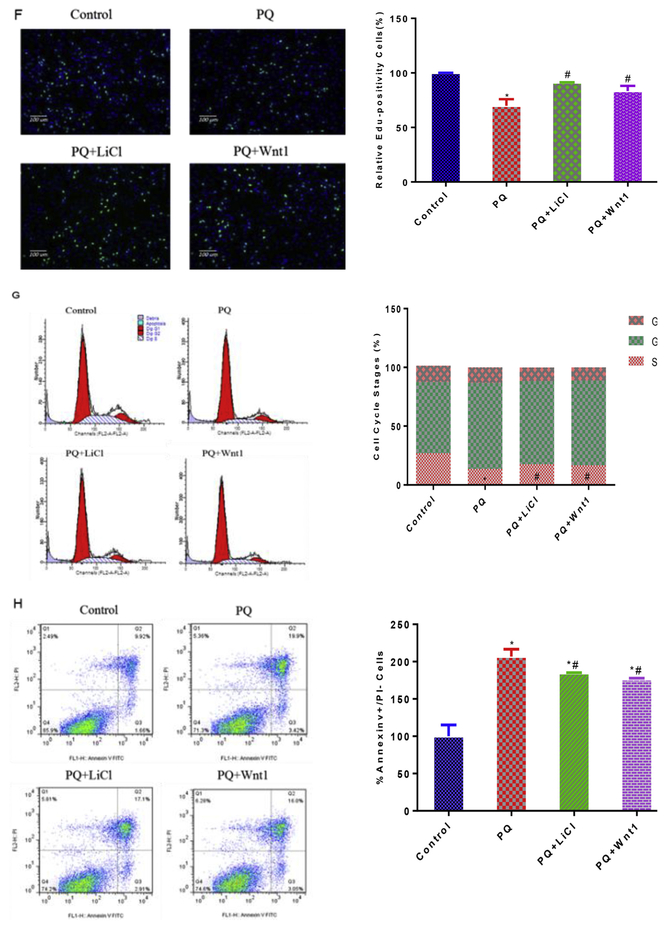

To further determine the extent to which Wnt signaling pathway involves in PQ-induced cytotoxicity, we mimicked Wnt pathway activation by treatment with LiCl and Wnt1. LiCl inhibits GSK-3β activity and increase β-catenin’s nuclear translocation (Meffre et al., 2015), andWnt1 binds the Frizzled receptor involving in the canonical β-catenin dependent transduction pathway (Arenas, 2014; Bengoa-Vergniory and Kypta, 2015). We observed that 2 mM LiCl and 100 ng/mL Wnt1 treatment alleviated the decrease in cell viability caused by PQ (Fig. 3A, B, C, D), indicating they could be used as Wnt signaling pathway activator.

Fig. 3.

Activation of Wnt/β-catenin with LiCl or Wnt1 attenuate PQ-induced oxidative damages in NPCs. Effect of various concentration LiCl and Wnt1 on cell viability after 24 h exposure (A, C). The cytoprotection role of LiCl (2 mM) and Wnt1 (100 ng/mL) were measured as cell viability improvement, against cell death elicited by PQ (B, D). After treatment with PQ, PQ + LiCl and PQ + Wnt1, flow cytometry analyzed of ROS production (E), cell cycles (G) and apoptosis (H); Edu analyzed of proliferation in NPCs, nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue), cells stayed in proliferation were stained with Apollo dye reaction buffer (green) (F). *p < 0.05 compared to control. #p < 0.05 compared to PQ treatment. *#p < 0.05 compared to control and PQ treatment. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

To test the hypothesized reduction of ROS via Wnt activation, we then incubated NPCs with PQ, PQ + LiCl (2 mM) and PQ + Wnt1(100 ng/mL). Indeed, the production of ROS was lowered in PQ + LiCl group and PQ + Wnt1group, compared with PQ group (Fig. 3E). Correspondingly, the proliferation suppression and apoptosis provoked by PQ were ameliorated in PQ + LiCl group and PQ + Wnt1group (Fig. 3F, G and H).

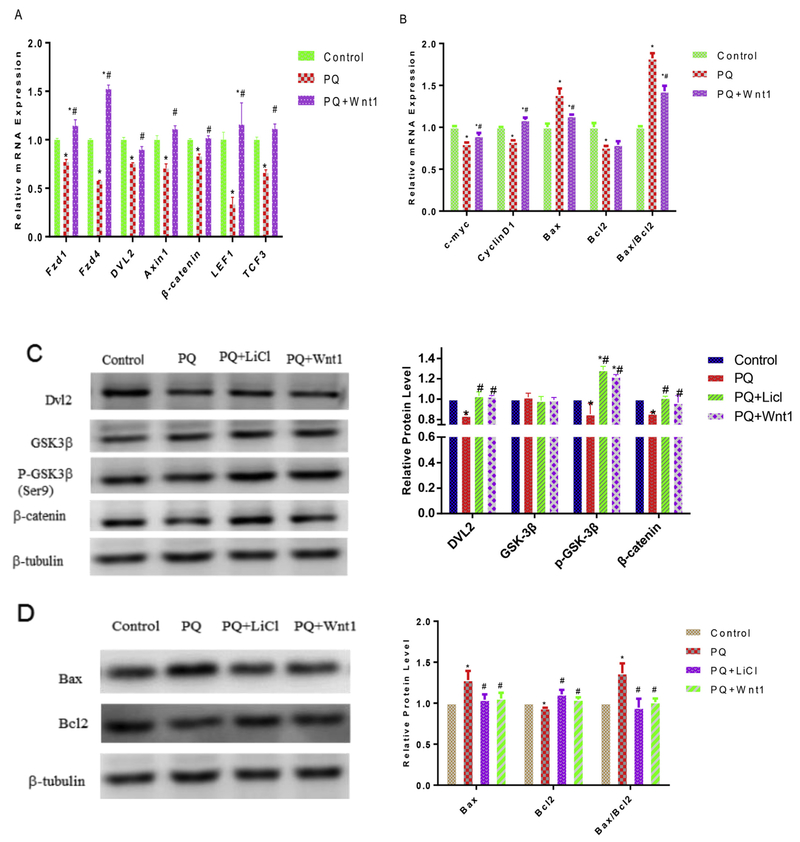

3.4. PQ induced apoptosis and inhibited proliferation via disturbing Wnt/β-catenin pathway

Having shown the amelioration of antioxidant treatment, we aimed to further elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms via examining the effect of PQ on the expression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway genes and Wnt target genes. We used quantitative real-time PCR analysis to reveal that PQ indeed altered expression of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway genes in mNPCs. PQ treatment significantly diminished the expression of genes, including Fzd1/4, DVL2, Axin1 and β-catenin, as compared to these of control (P < 0.05, Fig. 4A). Further, PQ significantly reduced the expression of nuclear transcription factor (LEF-1, TCF) and Wnt target gene (c-myc, cyclin-D1 and Bcl2 (Fig. 4B). Immunoblot analysis showed that PQ significantly reduced the levels of Wnt pathway proteins (DVL2, p-(Ser9)-GSK-3β and β-catenin) as compared to control (P < 0.05, Fig. 4C). Similarly, PQ-induced reduction of the protein levels of DVL2, p-(Ser9)-GSK-3β and β-catenin, which correlated with the elevation after added LiCl and Wnt1(Fig. 4C). Treatment with PQ induced an increase in the mRNA and protein level of Bax and a decrease in those of Bcl2 (Fig. 4B, D). Furthermore, the ratio of Bax/Bcl2 increased approximate 1.6-fold in PQ-treated cells compared with that in control cells (Fig. 4B, D), which correlated with the reduction after added LiCl and Wnt1(Fig. 4D). Taken together, our results indicate that Wnt pathway is involved in PQ-induced inhibited proliferation and apoptosis in NPCs.

Fig. 4.

PQ induces Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway inhibition. Post-treatment of Wnt signaling pathway activators (LiCl or Wnt1), the mRNA level of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway genes Fzd1/4, DVL2, Axin1, β-catenin, LEF1, TCF3 (A) and its downstream targets, c-myc, CyclinD1, Bcl2 and Bax (B) were measured by q-PCR. The protein expression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, DVL2, GSK-3β, p-(Ser9)-GSK-3β and β-catenin, and its downstream targets Bcl2 and Bax were measured by Western blot, β-Tubulin was used to normalized the Western blots (C, D). Then quantitative analysis of the above mentioned genes were normalized by PPIA. *p < 0.05 compared to control. #p < 0.05 compared to PQ only. *#p < 0.05 compared to control and PQ treatment.

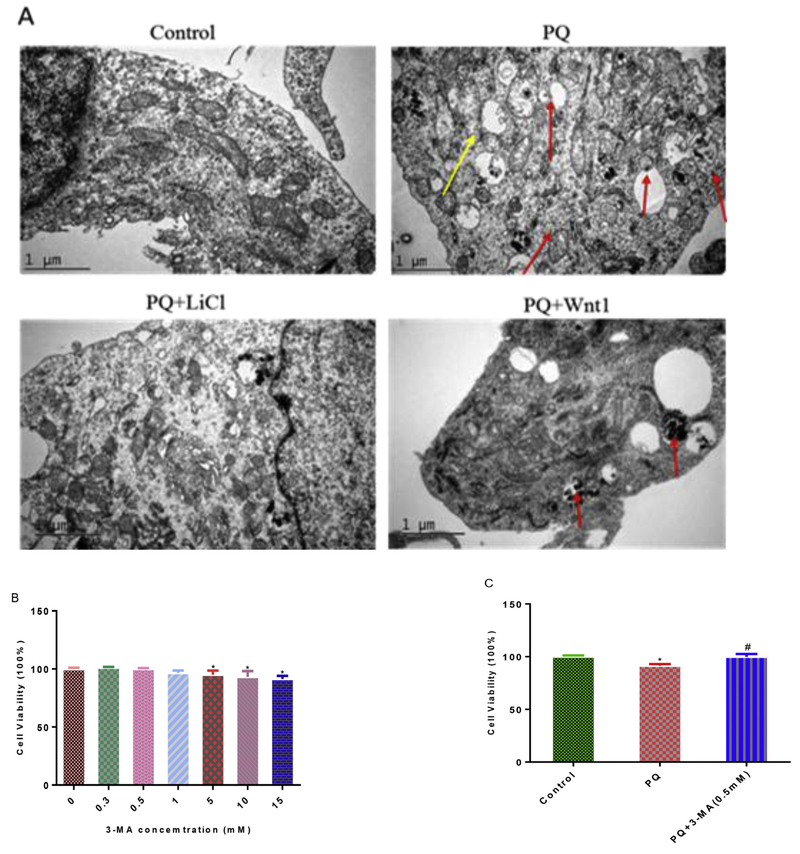

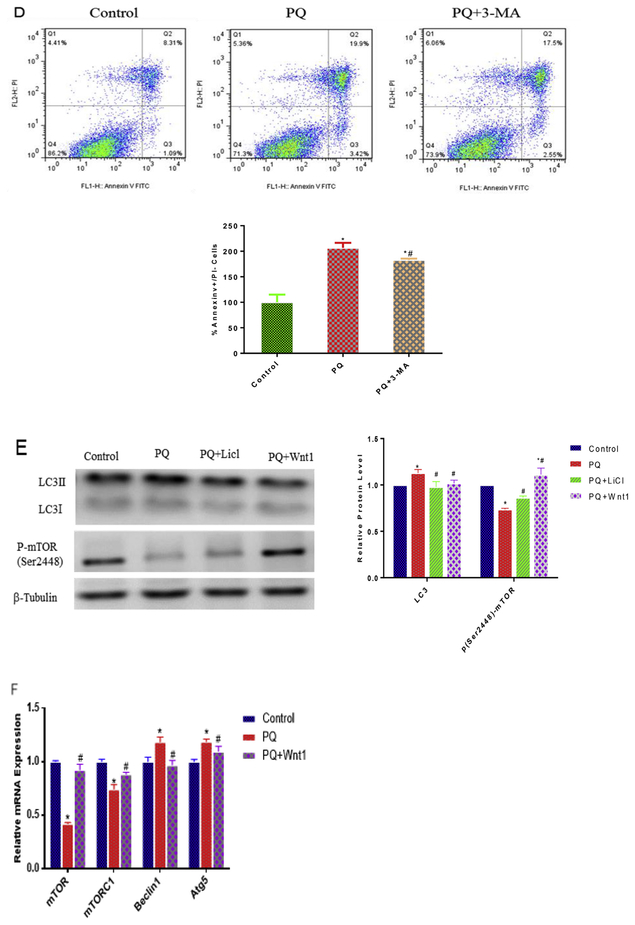

3.5. Activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway attenuates PQ-induced autophagic cell death

Autophagy is an important endogenous defensing pathway, which plays an important role in neurodegeneration, neurodevelopment and neurogenesis (Levine and Kroemer, 2008; Meng et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2016). To test the extent to which autophagy is involved in PQ-induced cytotoxicity, we examined autophagic vacuole using electronic microscope. Indeed, PQ exposure significantly increased the number of autophagic vacuole and mitochondrial swelling after 24 h treatment by transmission electron microscope observation (Fig. 5A). Intriguingly, activation of Wnt pathway with LiCl or Wnt1 both reduced the production of autophagosome and mitochondrial swelling caused by PQ (Fig. 5A). To elucidate the role of autophagy in PQ-induced cytotoxicity, we next assessed the extent of cell death after NPCs undergoing PQ and pharmacological agent by which autophagy is regulated. The results showed that 3-MA (0.5 mM) (Fig. 5B, C), a classical inhibitor of autophagy, attenuated cell death in NPCs after 1 h pre-treatment (Fig. 5D), which is consistent with the activation of Wnt signaling pathway (Fig. 3H). Finally, we performed Western blot and q-PCR analyses to determine the action of Wnt signaling pathway on autophagic cell death at the molecular level. Data showed that PQ up-regulated the LC3II/I protein level and Beclin1 (1.2 fold), Atg5 (1.2 fold) transcriptional levels, as it significantly reduced the expression of mTOR, mTORC1 and p-(Ser248)-mTOR by 59%, 26% and 26%, respectively (Fig. 5E and F). What’s more, the expression of autophagy molecular that were disturbed after PQ treatment were brought back to normal levels after LiCl or Wnt1 treatment (Fig. 5E and F). Taken together, these data provided several lines of evidences that activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway could attenuate PQ-induced autophagic cell death.

Fig. 5.

Activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway attenuate PQ-induced autophagic cell apoptosis. Post-treatment of Wnt signaling pathway activators (LiCl or Wnt1), the autophagic vacuole (red arrow) and swollen mitochondria (yellow arrow) were examined using TEM (A). Scale bar = 1 μM. Effect of various concentration 3-MA on cell viability after 1 h treatment (B) and the protective role of 3-MA (0.5 mM) pre-treatment on cell viability decline induced by PQ (C). The protective effect of 3-MA pre-treatment against cell death induced by PQ was measured using flow cytometry (D). Analysis of LC3II/I, p-(Ser 2448)-mTOR protein expression were explored by Western blot (E) and the mRNA expression of mTOR, mTORC1, Beclin1, Atg5 were determined by q-PCR (F) after the activation of Wnt signaling. β-Tubulin and PPIA were used to normalize the Western blots and q-PCR, respectively. *p < 0.05 versus control and #p < 0.05 versus PQ treatment. *#p < 0.05 versus both control and PQ treatment. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

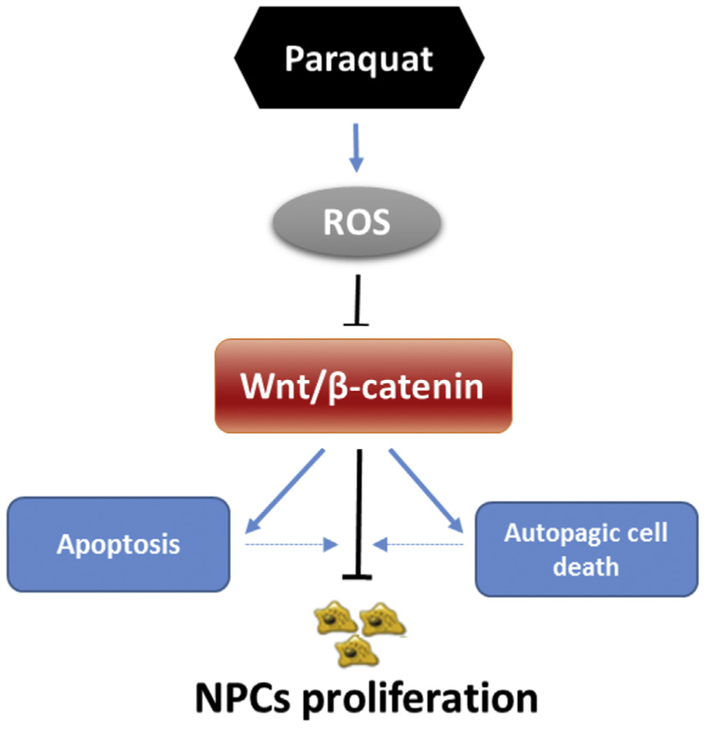

Adult neurogenesis is mainly restricted to SVZ of the lateral ventricles and the subgranular zone (SGZ) in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. NPCs in those areas continuously generate new neurons in the adult brain (Zhao et al., 2008). Cells born in the SVZ migrate through the rostral migratory stream towards the olfactory bulb, where they differentiate and functionally integrate as GABA-ergic and dopaminergic interneurons for an important role in nigrostriatal dopaminergic system (Winner et al., 2009). As one of the risk factors causing PD, we herein found that PQ could induce anti-proliferation and apoptosis via enhancing oxidative stress in mouse NPCs derived from SVZ. What’s more, we showed for the first time that Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays a critical role for NPCs protection against PQ-induced cell proliferation inhibition and cell death through crosstalk with mTOR pathway, which means activation of Wnt signaling pathway is able to dampen autophagic cell death effect of PQ (Fig. 6.).

Fig. 6.

Proposed mechanism of PQ cytotoxicity in marine NPCs. PQ exposure causes oxidative stress, which downregulates Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Downregulation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway in turn evokes apoptosis and autophagic cell death, leading to the NPCs inhibition of proliferation.

Several in vitro studies have found that PQ could induce oxidative damage to various neurocytes like NPCs and mature neurons (Takizawa et al., 2007; Yang and Tiffany-Castiglioni, 2005). Our study also indicated that PQ treatment reduces cell proliferation and induces apoptosis via enhanced oxidative stress in hNPCs (Chang et al., 2013). Similarly, the current report revealed that PQ treatment resulted in the induction of early apoptosis, G1 cell arrest and cellular proliferation and viability inhibition in a dose-dependent manner, which is consistent with the production of ROS in mice NPCs. These results indicate that oxidative stress is involved in PQ-induced cytotoxicity in mouse NPCs.

Wnt signaling inhibits GSK-3β activity by the phosphorylation of serine 9 (Ser9), therefore or thereby increasing the amount of β-catenin. β-catenin enters into the nucleus, and associates with TCF/LEF transcription factors, leading to the transcription of Wnt target genes involved in cell survival and proliferation (Gordon and Nusse, 2006). The role of Wnt signaling pathway in adult neurogenesis has been have confirmed in recent studies. For example, Wnt/β-catenin activation effciently protects adult NPCs of the SVZ against MPTP-induced neurogenic impairment (L’Episcopo et al., 2012). Activated astrocyte promote neurogenesis from adult neural progenitor cells and increase cell proliferation in the SVZ also via activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (Marchetti et al., 2013). With these finding in mind, we quantified the levels of mRNA and proteins involved in the regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. We observed that exposure to PQ inhibited Wnt/β-catenin pathway in NPCs as was evidenced by the down-regulation of the mRNA or proteins of Wnt signaling pathways, including Fzd1, Fzd4, Axin1, DVL2, β-catenin, LEF1, TCF3 and its target CyclinD1, c-myc, and Bcl2. Wnt signaling pathways involved in cell proliferation, survival and neurogenesis. In line with this, PQ treatment mice decreased the mRNA amount of several genes of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway such as TCF1/3, DVL2, Axin2 and β-catenin (Hichor et al., 2016). As a central negative regulatory factor of Wnt/β-catenin pathway, GSK-3β mediated inhibition of β-catenin potentially results in decreased NPCs survival (L’Episcopo et al., 2012). Next, we chose LiCl that inhibits GSK-3β by phosphorylation of Ser9 and the Wnt ligands (Wnt1) as the Wnt pathway activator to explore whether the stimulation of this pathway could counteract the deleterious effects of PQ. The results showed that PQ-induced activation of GSK-3β by the downregulation of p-(Ser9)-GSK-3β significantly reduced β-catenin cytosolic protein level. Activate Wnt/β-catenin pathway using LiCl or Wnt1 effectively restored the PQ-induced Wnt-related molecular changes mentioned above and attenuated the cell apoptosis, cycle arrest and proliferation inhibition induced by PQ. Those revealed that Wnt/β-catenin pathway involves in PQ-induced NPCs cytotoxicity. In addition, as an important second messenger involved in regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and signal transduction the overload of ROS will perturb various cellular signal such PI3K/Akt, p38 MAPK, JNK, and mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, which determine the cell fate (Lee et al., 2014; Yuan et al., 2015). Studies also indicate that Wnt signaling pathway may be inhibited by oxidative stress in various disease models (Almeida et al., 2009; Wei et al., 2015). For example, 6-OHDA treatment could down-regulate Wnt/β-catenin pathway via oxidative stress in SH-SY5Y (Wei et al., 2015). Our present data showed the production of ROS and down-regulation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway after PQ treatment. Pretreated with NAC, a free radical scavenger which acts as a cysteine donor to maintain or even increase the intracellular levels of glutathione (Romero et al., 2016), was able to dampen the Wnt/β-catenin pathway down-regulation effect of PQ as was evident by the up-regulation of Wnt proteins such as DVL2, β-catenin and p-(Ser9)-GSK-3β in NPCs. What’s more, the inhibition of GSK3β was reported to be related to the inhibition of oxidative stress (Li et al., 2011). The current report revealed that activation of Wnt signaling pathway inhibited the activity of GSK-3β by increasing the phosphorylation at site Ser9 and reduced the production of ROS and the subsequent oxidative damages induced by PQ in NPCs. Consistently, activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway could attenuate 6-OHDA-induced neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y via reducing ROS production (Wei et al., 2015). Those data indicated that activation of Wnt pathway by LiCl and Wnt1 could attenuate PQ-induced oxidative damages in NPCs.

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved lysosomal pathway involving physiological turnover of cellular long-lived proteins and dysfunctional organelles, which plays an important role in development, differentiation, and cellular homeostatic functions (Levine and Kroemer, 2008; Mizushima et al., 2008). Proper autophagy serves as an adaptive role to protect organisms against diverse pathologies and positively regulates cellular processes for survival (Hara et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2015). However, excessive autophagy will result in autophagic cell death (Amaravadi et al., 2011). Inhibiting autophagy has been reported to be beneficial in several cells (Lin et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2017). For example, inhibition of autophagy prevents irradiation-induced NPCs death in the dentate gyrus and cerebellum in juvenile mice (Wang et al., 2017), and inhibition of mTOR signaling increases neuronal apoptosis in vitro induced by rotenone (Zhou et al., 2016). In this study, our results showed the stimulated autophagy, as evident by the increased autophagic structures in cytoplasm, down-regulation of mTOR, mTORC1, p-mTOR, up-regulation of Beclin1, Atg5 and the ratio of LC3II/I, and the increased apoptosis after PQ treatment. What’s more, pre-treatment with 3-MA attenuated cell apoptosis, indicating that autophagic cell death was involved in PQ-induced NPCs death.

As both Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and autophagy have several roles in cell development, differentiation and survival, and sharing the same critical molecule GSK-3β, which has a central role in determine cell survival and apoptosis (Gordon and Nusse, 2006; Lin et al., 2014; Shin et al., 2006). There may exist a connection between Wnt/β-catenin signaling and autophagy. Recent studies have shown that Wnt/β-catenin signaling acts as a negative regulator of both basal and stress-induced autophagy (Fu et al., 2014), and activation of Wnt signaling could attenuate autophagic cell death in glutamate excitotoxicity injury (Yang et al., 2017). In line with this, our studies found that activating Wnt pathway with Wnt1 or LiCl attenuated PQ-induced cell autophagy as was evident by the reduced autophagic vacuole in cytoplasm and mitigated changes of autophagy-related molecule.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings indicate that PQ could induce apoptosis and anti-proliferation in NPCs through inducing the oxidative stress to inhibit Wnt/β-catenin signaling and activate autophagic cell death for the first time. Intriguingly the activation of Wnt pathway by LiCl or Wnt1 is able to mitigate oxidative damages and autophagic cell death caused by PQ. For a better understanding of the underlying mechanism of Wnt-mTOR pathway and its significance in cell death after PQ treatment, further investigations are required. Because NPCs is critical for cell renewal and injury reparation in adult neurogenesis, our results opens a new potential therapeutic avenue for PD.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Funds (NSFC 81472996, 81773472 China). The laboratory of Z.W was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health (R01ES25761, U01ES026721 opportunity fund, and R21ES028351) and Johns Hopkins Catalyst Award.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

ZW serves as a consultant for CUSABIO (CusAb) Company, Wuhan, China. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2018.08.064.

References

- Almeida M, Ambrogini E, Han L, Manolagas SC, Jilka RL, 2009. Increased lipid oxidation causes oxidative stress, increased peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma expression, and diminished pro-osteogenic Wnt signaling in the skeleton. J. Biol. Chem 284, 27438–27448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaravadi RK, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Yin XM, Weiss WA, Takebe N, Timmer W, DiPaola RS, Lotze MT, White E, 2011. Principles and current strategies for targeting autophagy for cancer treatment. Clin. Canc. Res 17, 654–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas E, 2014. Wnt signaling in midbrain dopaminergic neuron development and regenerative medicine for Parkinson’s disease. J. Mol. Cell Biol 6, 42–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengoa-Vergniory N, Kypta RM, 2015. Canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling in neural stem/progenitor cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 72, 4157–4172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case AJ, Agraz D, Ahmad IM, Zimmerman MC, 2016. Low-dose aronia melanocarpa concentrate attenuates paraquat-induced neurotoxicity. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2016, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang X, Lu W, Dou T, Wang X, Lou D, Sun X, Zhou Z, 2013. Paraquat inhibits cell viability via enhanced oxidative stress and apoptosis in human neural progenitor cells. Chem. Biol. Interact 206, 248–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desplats P, Patel P, Kosberg K, Mante M, Patrick C, Rockenstein E, Fujita M, Hashimoto M, Masliah E, 2012. Combined exposure to Maneb and paraquat alters transcriptional regulation of neurogenesis-related genes in mice models of Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener 7, 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drechsel DA, Patel M, 2008. Role of reactive oxygen species in the neurotoxicity of environmental agents implicated in Parkinson’s disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med 44, 1873–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Chang H, Peng X, Bai Q, Yi L, Zhou Y, Zhu J, Mi M, 2014. Resveratrol inhibits breast cancer stem-like cells and induces autophagy via suppressing Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. PLoS One 9, 2102535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MD, Nusse R, 2006. Wnt signaling: multiple pathways, multiple receptors, and multiple transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem 281, 22429–22433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T, Nakamura K, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakahara Y, Suzuki-Migishima R, Yokoyama M, Mishima K, Saito I, Okano H, Mizushima N, 2006. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature 441, 885–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hichor M, Sampathkumar NK, Montanaro J, Borderie D, Petit PX, Gorgievski V, Tzavara ET, Eid AA, Charbonnier F, Grenier J, Massaad C, 2016. Paraquat induces peripheral myelin disruption and locomotor defects: crosstalk with LXR and Wnt pathways. LID. 10.1089/ars.2016.6711. [doi]. Antioxidants & redox signaling). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogberg HT, Kinsner-Ovaskainen A, Hartung T, Coecke S, Bal-Price AK, 2009. Gene expression as a sensitive endpoint to evaluate cell differentiation and maturation of the developing central nervous system in primary cultures of rat cerebellar granule cells (CGCs) exposed to pesticides. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 235, 268–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BC, Huang X, Mailman RB, Lu L, Williams RW, 2014. The perplexing paradox of paraquat: the case for host-based susceptibility and postulated neurodegenerative effects. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol 28, 191–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L’Episcopo F, Serapide MF, Tirolo C, Testa N, Caniglia S, Morale MC, Pluchino S, Marchetti B, 2011. A Wnt1 regulated Frizzled-1/beta - Catenin signaling pathway as a candidate regulatory circuit controlling mesencephalic dopaminergic neuronastrocyte crosstalk: therapeutical relevance for neuron survival and neuroprotection. Mol. Neurodegener 6, 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L’Episcopo F, Tirolo C, Testa N, Caniglia S, Morale MC, Deleidi M, Serapide MF, Pluchino S, Marchetti B, 2012. Plasticity of subventricular zone neuroprogenitors in MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) mouse model of Parkinson’s disease involves cross talk between inflammatory and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathways: functional consequences for neuroprotection and repair. J. Neurosci 32, 2062–2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L’Episcopo F, Tirolo C, Testa N, Caniglia S, Morale MC, Impagnatiello F, Pluchino S, Marchetti B, 2013. Aging-induced Nrf2-ARE pathway disruption in the sub-ventricular zone drives neurogenic impairment in parkinsonian mice via PI3K-Wnt/beta-catenin dysregulation. J. Neurosci 33, 1462–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JE, Lim MS, Park JH, Park CH, Koh HC, 2014. Nuclear NF-kappaB contributes to chlorpyrifos-induced apoptosis through p53 signaling in human neural precursor cells. Neurotoxicology 42, 58–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Moon JH, Kim SW, Jeong JK, Nazim UM, Lee YJ, Seol JW, Park SY, 2015. EGCG-mediated autophagy flux has a neuroprotection effect via a class III histone deacetylase in primary neuron cells. Oncotarget 6, 9701–9717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Kroemer G, 2008. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 132, 27–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Cheng X, Jiang J, Wang J, Xie J, Hu X, Huang Y, Song L, Liu M, Cai L, Chen L, Zhao S, 2017. The toxic influence of paraquat on hippocampal neurogenesis in adult mice. Food Chem. Toxicol.: Int. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc 106, 356–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Luo F, Wei L, Liu Z, Xu P, 2011. Knockdown of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta attenuates 6-hydroxydopamine-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells. Neurosci. Lett 487, 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CJ, Chen TH, Yang LY, Shih CM, 2014. Resveratrol protects astrocytes against traumatic brain injury through inhibiting apoptotic and autophagic cell death. Cell Death Dis. 5, e1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti B, L’Episcopo F, Morale MC, Tirolo C, Testa N, Caniglia S, Serapide MF, Pluchino S, 2013. Uncovering novel actors in astrocyte-neuron crosstalk in Parkinson’s disease: the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling cascade as the common final pathway for neuroprotection and self-repair. Eur. J. Neurosci 37, 1550–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins JB, Bastos Mde L, Carvalho F, Capela JP, 2013. Differential effects of methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion, rotenone, and paraquat on differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. J. Toxicol 2013, 347312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meffre D, Massaad C, Grenier J, 2015. Lithium chloride stimulates PLP and MBP expression in oligodendrocytes via Wnt/beta-catenin and Akt/CREB pathways. Neuroscinece 284, 962–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y, Yong Y, Yang G, Ding H, Fan Z, Tang Y, Luo J, Ke ZJ, 2013. Autophagy alleviates neurodegeneration caused by mild impairment of oxidative metabolism. J. Neurochem 126, 805–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra S, Chakrabarti N, Bhattacharyya A, 2011. Differential regional expression patterns of alpha-synuclein, TNF-alpha, and IL-1beta; and variable status of dopaminergic neurotoxicity in mouse brain after paraquat treatment. J. Neuroinflammation 8, 163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ, 2008. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature 451, 1069–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niso-Santano M, Gonzalez-Polo RA, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Gomez-Sanchez R, Lastres-Becker I, Ortiz-Ortiz MA, Soler G, Moran JM, Cuadrado A, Fuentes JM, 2010. Activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 is a key factor in paraquat-induced cell death: modulation by the Nrf2/Trx axis. Free Radic. Biol. Med 48, 1370–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero A, Ramos E, Ares I, Castellano V, Martinez M, Martinez-Larranaga MR, Anadon A, Martinez MA, 2016. Oxidative stress and gene expression profiling of cell death pathways in alpha-cypermethrin-treated SH-SY5Y cells. Arch. Toxicol 91, 2151–2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K, Ohtaki K, Matsubara K, Aoyama K, Uezono T, Saito O, Suno M, Ogawa K, Hayase N, Kimura K, Shiono H, 2001. Carrier-mediated processes in blood–brain barrier penetration and neural uptake of paraquat. Brain Res. 906, 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SY, Chin BR, Lee YH, Kim JH, 2006. Involvement of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in hydrogen peroxide-induced suppression of Tcf/Lef-dependent transcriptional activity. Cell. Signal 18, 601–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shruster A, Eldar-Finkelman H, Melamed E, Offen D, 2011. Wnt signaling pathway overcomes the disruption of neuronal differentiation of neural progenitor cells induced by oligomeric amyloid beta-peptide. J. Neurochem 116, 522–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa M, Komori K, Tampo Y, Yonaha M, 2007. Paraquat-induced oxidative stress and dysfunction of cellular redox systems including antioxidative defense enzymes glutathione peroxidase and thioredoxin reductase. Toxicol. Vitro 21, 355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela-Nallar L, Inestrosa NC, 2013. Wnt signaling in the regulation of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Front. Cell. Neurosci 7, 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhou K, Li T, Xu Y, Xie C, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Rodriguez J, Blomgren K, Zhu C, 2017. Inhibition of autophagy prevents irradiation-induced neural stem and progenitor cell death in the juvenile mouse brain. Cell Death Dis. 8 e2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L, Ding L, Mo MS, Lei M, Zhang L, Chen K, Xu P, 2015. Wnt3a protects SHSY5Y cells against 6-hydroxydopamine toxicity by restoration of mitochondria function. Transl. Neurodegener 4, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdowson PS, Farnworth MJ, Simpson MG, Lock EA, 1996. Influence of age on the passage of paraquat through the blood-brain barrier in rats: a distribution and pathological examination. Hum. Exp. Toxicol 15, 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winner B, Desplats P, Hagl C, Klucken J, Aigner R, Ploetz S, Laemke J, Karl A, Aigner L, Masliah E, Buerger E, Winkler J, 2009. Dopamine receptor activation promotes adult neurogenesis in an acute Parkinson model. Exp. Neurol 219, 543–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Fleming A, Ricketts T, Pavel M, Virgin H, Menzies FM, Rubinsztein DC, 2016. Autophagy regulates Notch degradation and modulates stem cell development and neurogenesis. Nat. Commun 7, 10533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Tiffany-Castiglioni E, 2005. The bipyridyl herbicide paraquat produces oxidative stress-mediated toxicity in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells: relevance to the dopaminergic pathogenesis. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 68, 1939–1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Luo P, Xu H, Dai S, Rao W, Peng C, Ma W, Wang J, Xu H, Zhang L, Zhang S, Fei Z, 2017. RNF146 inhibits excessive autophagy by modulating the Wnt-beta-catenin pathway in glutamate excitotoxicity injury. Front. Cell. Neurosci 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan TF, Gu S, Shan C, Marchado S, Arias-Carrion O, 2015. Oxidative stress and adult neurogenesis. Stem Cell Reviews and Report 11, 706–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Yang X, Yang S, Zhang J, 2011. The Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in the adult neurogenesis. Eur. J. Neurosci 33, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Deng W, Gage FH, 2008. Mechanisms and functional implications of adult neurogenesis. Cell 132, 645–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Chen B, Wang X, Wu L, Yang Y, Cheng X, Hu Z, Cai X, Yang J, Sun X, Lu W, Yan H, Chen J, Ye J, Shen J, Cao P, 2016. Sulforaphane protects against rotenone-induced neurotoxicity in vivo: involvement of the mTOR, Nrf2, and autophagy pathways. Sci. Rep 6, 32206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]