INTRODUCTION

The last several decades have seen significant advances in the evaluation and treatment of coronary artery disease. Multiple non-invasive methods for the diagnosis of coronary atherosclerosis have matured and are in wide clinical practice. Improving risk factors and primary1,2 and secondary prevention strategies3 have resulted in a decline in cardiac mortality and myocardial infarction.4,5 The focus of these diagnostic methods and treatment strategies has been on the identification and treatment of atherosclerotic lesions of the epicardial coronary arteries, particularly obstructive, ischemia causing lesions. While there is no doubt that this approach has been tremendously successful, it must be noted the coronary arterial circulation extends from large epicardial conduit arteries through resistance arterioles (i.e., the microvasculature) to the intra-myocardial capillary bed. Dysfunction of the microvasculature and pre-obstructive disease of the epicardial arteries can not only cause typical anginal symptoms but also may be harbingers of adverse prognosis. In the following paragraphs, we will discuss current approaches to the quantification of coronary vascular function and the evidence supporting its potential diagnostic and prognostic implications with a particular focus on ischemic heart disease.

DIAGNOSIS OF OBSTRUCTIVE CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

In addition to clinical history and symptoms, stress testing modalities are an integral part of the standard evaluation for epicardial coronary atherosclerotic disease among intermediate risk patients.6 Addition of imaging to identify stress-induced perfusion abnormalities substantially improves sensitivity for diagnosing obstructive stenosis. A recent meta-analysis has demonstrated excellent diagnostic performance of both SPECT and PET myocardial perfusion imaging (radionuclide MPI, R-MPI)7 with sensitivities of 88% and 84% and specificities of 61% and 81%, respectively. Stress R-MPI can be performed in a wide array of patients including those in whom other methods may be limited due to obesity or lung disease. Although nuclear methods result in radiation exposure, the effective doses can be substantially limited with modern equipment and protocols.8

While the overall per patient sensitivity of these methods is excellent, it is well known that the ability of semi-quantitative myocardial perfusion imaging to delineate the full extent of atherosclerosis remains limited.9 This may be, in part, due to the implicit assumption that the best perfused segments are normal when perfusion images are interpreted semi-quantitatively. As a result, the sensitivity for prospective identification of multi-vessel disease remains limited. Incorporation of additional signs such as multi-vessel myocardial perfusion defect pattern,10 transient ischemic dilation (TID),11–13 pulmonary uptake,14–17 right ventricular uptake,18 and decline in stress left ventricular ejection fraction (EF)19,20 can improve diagnostic sensitivity for left main and three-vessel coronary artery disease. In one series of patients with left main coronary artery disease, no combination of diagnostic criteria could reliably identify all patients (Figure 1).21 Further-more, semi-quantitative perfusion imaging is inherently unable to identify regions where diffuse atherosclerosis is not sufficiently severe to limit tissue perfusion.

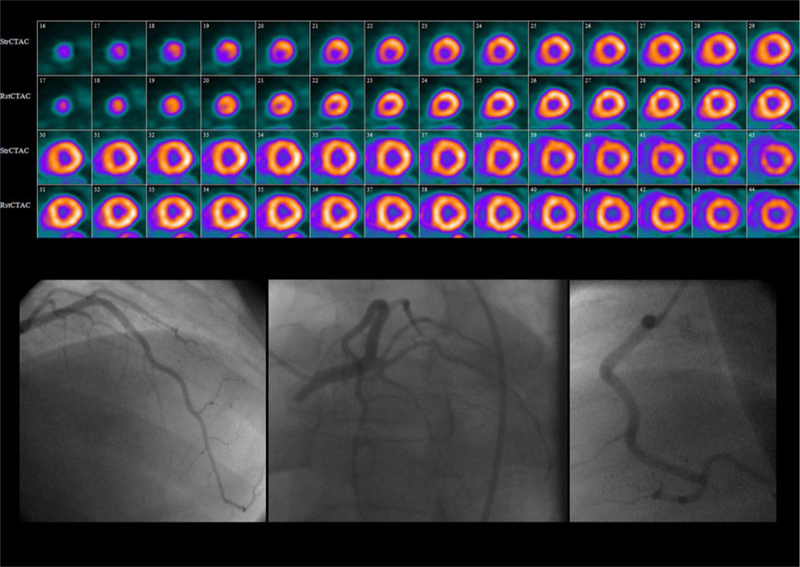

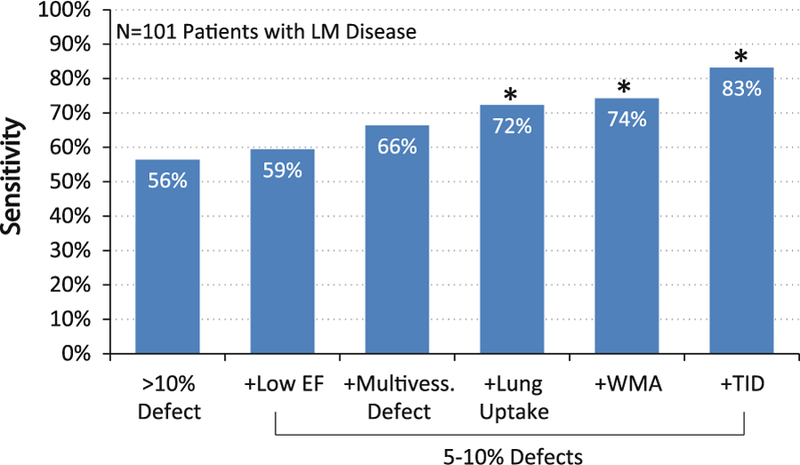

Figure 1.

Underestimation of extent of CAD by R-MPI. Despite excellent overall per patient sensitivity for the presence of disease, traditional relative myocardial perfusion imaging (R-MPI) often underestimates disease extent and is unable to reliably distinguish patients with severe CAD from those with milder disease. Even addition of ancillary signs of advanced CAD such as decreased EF, defects involving multiple vessel territories, lung uptake, wall motion abnor-malities and TID were not able to capture all cases of left main disease. Adapted with permission from Berman et al.21 *P <.05 compared to >10% defect.

Several other imaging modalities also have well-established data supporting their use for the diagnosis of obstructive coronary artery disease. Echocardiography can be performed during exercise or administration of inotropic agents (typically dobutamine) to identify stress-induced regional wall motion abnormalities as markers of ischemia with overall per patient sensitivity 81.2% and specificity of 82.2% for obstructive CAD on angiography.22 Interpretation of results is complicated in patients with prior myocardial infarction due to resting wall motion abnormalities and leads to suboptimal diagnostic performance in this setting.22 This method requires excellent acoustic windows for optimal diagnostic performance, which are often unavailable in patients with obesity or lung disease. Furthermore, image quality is highly operator dependent and may limit test accuracy. As for R-MPI, findings which suggest the presence of extensive CAD such as cavity dilation and decline in global LVEF are frequently absent.23–25

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be used to identify stress-induced perfusion defects and/or wall motion abnormalities.9 A large prospective single-center evaluation of stress MRI has demonstrated a sensitivity of 86.5% and a specificity of 83.4% for the identification of angiographic CAD,26 although other multi-center studies have suggested considerably lower diagnostic performance.27 Assessment of myocardial perfusion with MRI, at present, requires the use of gadolinium-based contrast media, which are contraindicated in patients with severe renal dysfunction. Obese patients often cannot be accommodated inside the standard-bore or, in some cases, even in wide-bore scanners. Patients who experience claustrophobia or who have difficulty in holding their breath may not be able to tolerate cardiac MRI examinations. Most importantly, at present, many centers lack adequate instrumentation and/or expertise to reliably perform stress cardiac MRI. Finally, MRI is contraindicated in patients using many types of implanted medical devices including most pacemakers and all defibrillators currently approved. However, off-label studies suggest that these studies can, in select cases, be performed safely.28

Computed tomography (CT)-based methods such as coronary CT angiography can detect both obstructive and non-obstructive epicardial atherosclerosis.29 Although the full anatomic extent of atherosclerotic changes can be readily delineated by CT angiography, this method is unable to reliably assess whether this disease is sufficient to cause myocardial ischemia.30 This distinction is critical to determine whether a patient’s symptoms are related to CAD.

QUANTIFICATION OF MYOCARDIAL BLOOD FLOW (MBF) AND FLOW RESERVE

As discussed above, two important limitations of myocardial perfusion imaging arise from semi-quantitative interpretation: the underestimation of the extent of ischemia when all three coronary territories are affected and inability to identify patients with non-obstructive stenosis. Quantitative assessment of MBF offers the opportunity to add important information to semi-quantitative assessments of R-MPI and potentially overcome these limitations. Both absolute stress MBF and flow reserve, expressed as the ratio of stress over rest MBF, have been proposed for this application. A number of invasive and non-invasive methods have been employed to quantify MBF and flow reserve and are briefly discussed below.

Invasive Methods

The gold standard method remains invasive evaluation of coronary flow velocity with a Doppler wire to measure coronary flow reserve (CFR) by comparing rest flow velocity with that during vasodilator stress. More commonly, fractional flow reserve is assessed using a pressure wire to compare the pressure gradient across an area of luminal narrowing before and after administration of adenosine. Semi-quantitative assessments of coronary blood flow and myocardial perfusion such as the TIMI frame count and blush score have largely been confined to research applications and used only for assessing myocardial perfusion at rest.31,32 Finally, intra-coronary thermodilution can be used to quantify coronary blood flow using the Fick principle, but is rarely performed in practice. A more detailed comparison of these methods has been undertaken in recent studies33 and reviews.34

PET Imaging

Similar measurements can be made non-invasively with positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. Advances in software tools have enabled these measurements to be incorporated into routine PET stress testing.35 Initial studies were performed using 13N ammonia or 15O water. 13N ammonia is approved for clinical applications in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration. Because of its first-pass myocardial extraction is high even at high blood flow rates, accurate quantification across a wide range of MBF is possible. This tracer also offers excellent image quality for relative myocardial perfusion assessment. However, because the half-life of 13N is 9.97 minutes, the tracer must be produced at an onsite or nearby cyclotron facility. 15O water is freely diffusible, also permitting highly accurate quantification of myocardial perfusion. However, its clinical use is limited due to regulatory constraints (it is not approved by the FDA) and also because it is cumbersome to obtain images for semi-quantitative myocardial perfusion assessment. Furthermore, the 122-second half-life of 15O requires a cyclotron immediately adjacent to the PET facility.

82Rubidium is a potassium analog with a half-life of 75 seconds, which is actively transported across myocyte cell membranes. The advent of commercially available generators for onsite production of rubidium-82 has enabled the widespread use of PET imaging without the need for an onsite cyclotron facility. One limitation of this radiotracer is the fact that the maximum kinetic energy of positrons emitted during 82Rubidium decay is significantly higher than that of 18F or 13N. Consequently, the spatial uncertainty in the location of the decaying nucleus—which depends on the distance traveled by the positrons before their annihilation (positron range)—is greater for 82Rubidium (2.6 mm FWHM) than for 18F (0.2 mm FWHM) or 13N (0.7 mm FWHM). Although

82Rubidium imaging yields excellent image quality with current PET technology, its longer positron range and its short half-life, which requires significant image smoothing to suppress noise, both mitigate somewhat the improved spatial resolution of PET.36 Although the relatively low and nonlinear extraction of 82Rb37 make quantification more challenging, advances in methodology35,38 now permit rapid and reproducible quantification of blood flow with this tracer. However, due to the high cost of rubidium-82 generators, this technology is confined to a relatively small number of high volume centers at present.

Flurpiridaz is a novel 18F-labeled mitochondrial complex I inhibitor with excellent tracer characteristics39–41 currently undergoing phase 3 clinical investigation. This tracer has extremely high first-pass extraction42 allowing accurate flow quantification across the entire range of clinically relevant flows using traditional40 and simplified methods.43 The longer 109.7-minute half-life of the 18F radioligand permits centralized production and unit dose delivery of this agent. Lower barriers to entry, simplified logistics, and most importantly early indications of excellent safety and efficacy44 likely portend improved availability of PET myocardial perfusion imaging once this tracer garners regulatory approval.

Other Non-Invasive Methods

MRI can also be utilized to quantify myocardial perfusion in a similar manner,45,46 but remains cumbersome and restricted to research applications. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy can also be utilized to identify downstream myocardial metabolic changes, which may result from acute or chronic changes in tissue perfusion, but technically challenging to perform and consequently is largely confined to research applications. Doppler echocardiography of the left anterior descending coronary artery can be used to quantify perfusion in the territory subtended by this vessel at rest and stress in persons with excellent echocardiographic windows.47 Quantitative assessment of myocardial perfusion with contrast echocardiography is also possible48; however, at present no FDA approved agents are available in the United States for this application, analytical tools remain immature and application is constrained to those individuals with adequate sonographic windows. Dynamic CT can also be used to estimate MBF49,50 but is largely limited to research applications due to substantial radiation doses required.

Perhaps the greatest hope for a broadly available non-invasive method for quantification of myocardial perfusion would be to apply SPECT imaging for this purpose. Traditional rotating single- or multi-head SPECT cameras lack the ability to acquire time resolved tomographic volume data required for flow quantification. However, newer dedicated cardiac SPECT cameras utilize high sensitivity CZT detectors permitting acquisition of dynamic (multi-frame) imaging data and quantification of myocardial perfusion.51 Further investigations will be required to validate these measures.

QUANTITATIVE MBF FOR DIAGNOSIS OF OBSTRUCTIVE CAD

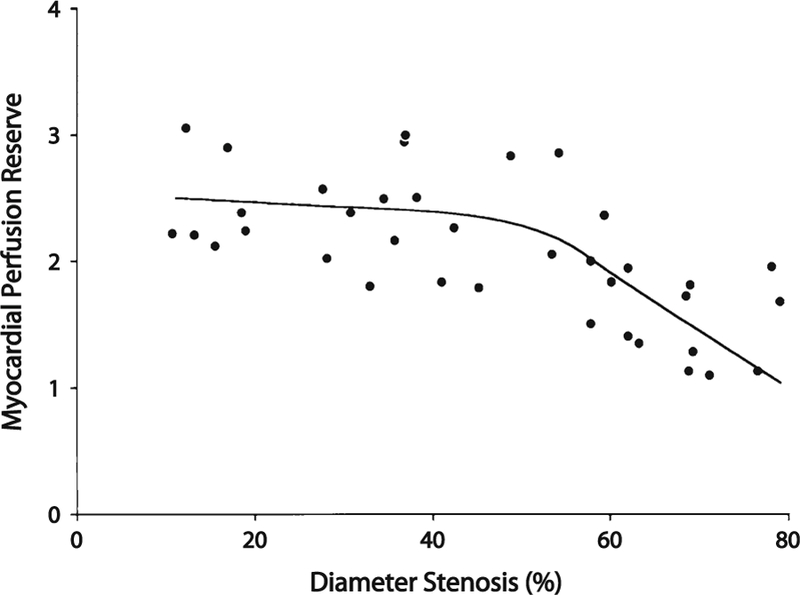

A number of studies have demonstrated that among relatively young patients with modest coronary risk factor burdens and predominantly single-vessel CAD, a relationship exists between MBF or flow reserve and percent diameter stenosis on angiography (Figure 2).52–55 These studies demonstrate that myocardial vasodilator capacity is relatively preserved for lesions with <50% stenosis. With increasing severity of stenosis beyond this level, there is progressive worsening of CFR. This observation has been utilized to improve identification of patients with severe CAD involving the left main coronary artery or all three coronary arteries with modest improvements in diagnostic performance56–58 compared to semi-quantitative myocardial perfusion assessments.

Figure 2.

Relationship between MPR and epicardial stenosis severity plot demonstrating that MPR determined by 13N ammonia PET declines rapidly for stenoses with >50% diameter stenosis on quantitative coronary angiography. Adapted with permission from Di Carli et al.53

The modest improvement in diagnostic accuracy is likely multi-factorial. In addition to fixed epicardial obstructive lesions, abnormalities of coronary arterial vasodilation may be due to underlying endothelial and/ or vascular smooth muscle dysfunction in large epicardial and/or downstream resistance vessels (the so-called microvascular dysfunction). Furthermore, coronary vascular dysfunction may occur in the absence of any angiographically detectible epicardial atherosclerosis.52,59,60 Abnormalities of coronary vascular function have been demonstrated in a variety of disease states known to be associated with accelerated coronary atherosclerosis without overt cardiovascular disease including hypertension,61 dyslipidemia,62,63 tobacco abuse,64,65 obesity,66,67 metabolic syndrome,68 diabetes,69–71 and renal dysfunction.72 As such, vascular dysfunction represents the earliest form of atherosclerosis, preceding the development of obstructive stenoses that are detectible by traditional imaging modalities,64,70,73,74 including coronary calcium scoring.75

Coronary risk factors alone, which are highly prevalent in patients referred for diagnostic testing, may result in decreases in peak MBF and flow reserve comparable to that caused by severe coronary artery stenoses.59 In some cases, such failure to adequately vasodilate may be sufficient to cause myocardial ischemia even in the absence of epicardial obstructive disease.76–78 Because the underlying process in these cases is diffuse atherosclerosis and/or endothelial dys-function, affecting all or most of the coronary tree, regional perfusion abnormalities may be difficult in identifying traditional semi-quantitative approaches. In contrast, non-invasive measures of coronary vascular function provide an integrated measure of the effects of obstructive epicardial stenosis with those of diffuse atherosclerosis and vessel remodeling and microvascular dysfunction.

Consequently, the differentiation of multi-vessel epicardial CAD from diffuse non-obstructive athero-sclerosis and/or microvascular dysfunction causing a global reduction in MBF and flow reserve in a patient without regional perfusion defects can be quite challenging, especially because in many patients these conditions may co-exist to varying degrees. As discussed below, this has important implications for decisions regarding referral for cardiac catheterization. It is unclear that this distinction can be made using a single severity threshold, as many patients often show profound reduction in myocardial flow reserve even in the absence of obvious epicardial stenosis (Figure 3).

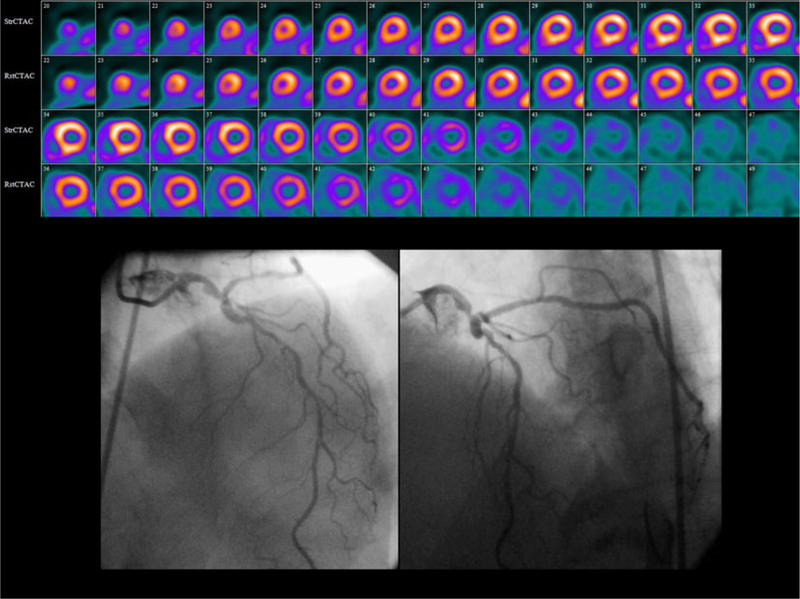

Figure 3.

Severely reduced MPR in the absence of severe epicardial stenosis relative perfusion images (top) from a 37-year-old man with diabetes, chronic kidney disease requiring hemodialysis, dyslipidemia hypertension, and past smoking referred for evaluation of chest pain and ST-segment depression on exercise testing show a small region of moderate stress-induced perfusion abnormality in the apex. The CFR measured with 82Rb PET was severely diminished at 1.22. Coronary angiography (bottom) showed no hemodynamically significant epicardial coronary lesions.

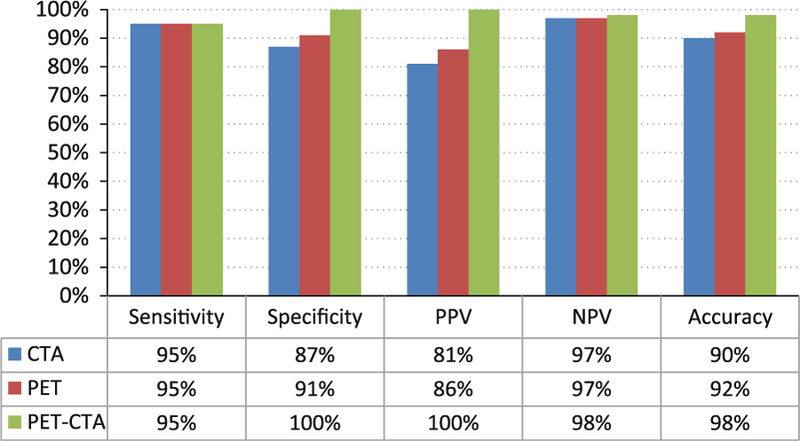

The addition of coronary CTA can be quite helpful to identify obstructive stenosis, which may contribute to reduced flow reserve. Indeed, Kajander et al79 demon-strated that the addition of information concerning the presence of epicardial coronary stenosis with CTA was able to increase the specificity of the quantitative PET findings (Figure 4). With state-of-the-art scanners and modern protocols, hybrid PET MPI and coronary CTA examinations to simultaneously identify obstructive and non-obstructive epicardial atherosclerosis and define its physiologic significance can be accomplished at a relatively low radiation exposure (6–10 mSv), or perhaps less using combined PET/MRI scanners. Conversely, by defining flow-limiting disease quantitative myocardial flow reserve measures improve the specificity of coronary CTA findings. On the other hand, the presence of a regional perfusion defect by semi-quantitative visual analysis combined with diffusely reduced myocardial flow reserve can be quite helpful for identification of multi-vessel CAD (Figures 4, 5).

Figure 4.

Addition of CTA to quantitative PET improves diagnostic accuracy sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and overall diagnostic accuracy for coronary CT angiography (CTA), quantitative 15O water PET stress perfusion or both among 107 prospective patients compared to quantitative invasive coronary angiography and fractional flow reserve assessments. Addition of CTA to PET significantly improved overall diagnostic accuracy compared to CTA alone (P = .004) or PET alone (P = .01). Adapted with permission from Kajander et al79.

Figure 5.

MPR is abnormal in occult multi-vessel CAD relative perfusion images (top) from a 64 year-old man referred for evaluation of substernal chest pain at rest showed only a small region of stress-induced perfusion abnormality in the inferolateral wall. Angiography (bottom) performed the next day demonstrated a complex 80% left main stenosis involving the ostia of the left circumflex and left anterior descending coronary arteries. The CFR measured with 82Rb PET was decreased at 1.63.

PROGNOSTIC IMPLICATIONS OF CORONARY VASCULAR DYSFUNCTION

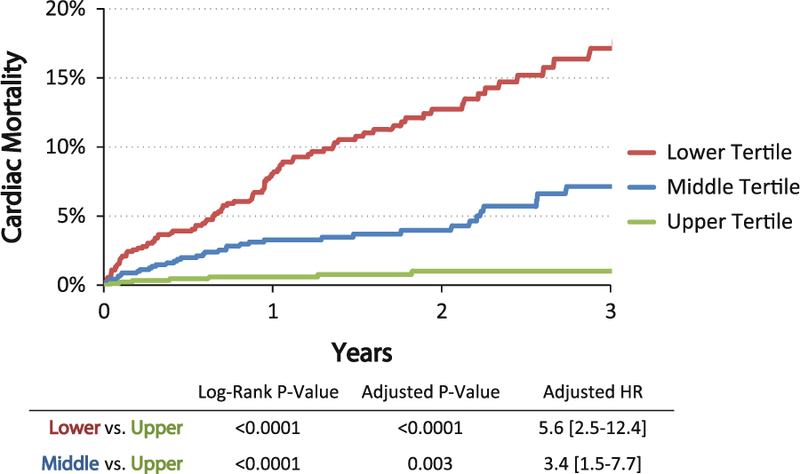

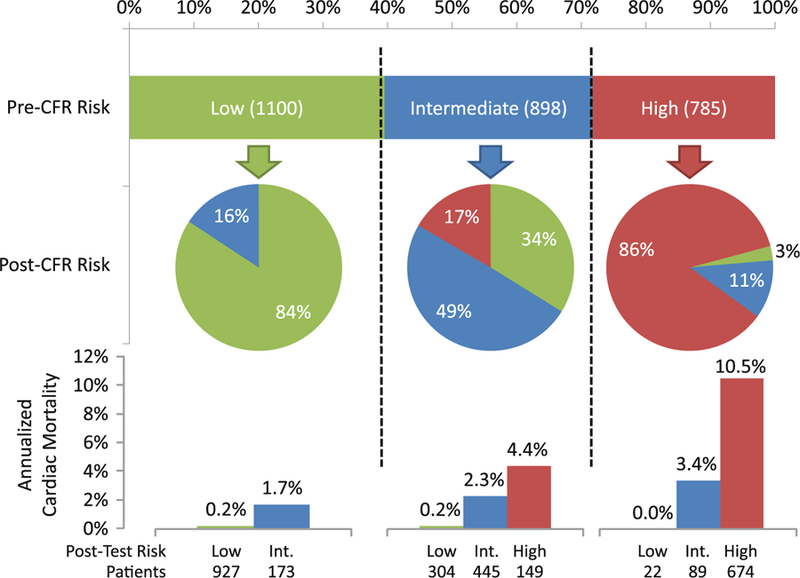

Because quantitative measures of coronary vascular function integrate the fluid dynamic effects of athero-sclerosis throughout the coronary arterial tree including epicardial stenoses with early changes to endothelial and/or smooth muscle function, quantitative myocardial flow reserve may be a superior measure of overall vascular health that provides unique information about clinical risk. Five studies have demonstrated that PET measures of myocardial flow reserve improve cardiac risk assessment (Table 1).80–84 The largest of these studies80 demonstrated that among 2,783 patients with known or suspected CAD evaluated with 82Rb PET, patients with CFR < 1.5 were at nearly 16-fold increased risk of death from cardiac causes compared to patients with CFR > 2.0. After adjustment for a wide array of risk factors and rest and stress imaging findings, these patients remained at nearly 6-fold increased risk of cardiac mortality (Figure 6). Furthermore, approximately half of patients who would be classified as intermediate risk based on clinical risk factors, systolic function and combined scar and ischemia extent are reclassified as either low or high risk (Figure 7).

Table 1.

Studies of prognostic impact of myocardial perfusion reserve (MPR)

| Study | Number of subjects | Follow-up duration (years) | Primary endpoint | Radiotracer | Adjusted covariates | Hazard ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herzog82 | 256 | 5.4 | MACE (cardiac death, non-fatal mi, late revascularization, cardiac hospitalization) | 13N Ammonia | Age, diabetes, smoking, abnormal perfusion (binary) | 1.6 (MFR <2.0 vs ≥2.0) |

| Tio83 | 344 | 7.1 | Cardiac death | 13N Ammonia | Age, sex | 4.1 (per 0.5 MFR) |

| Murthy80 | 2,783 | 1.4 | Cardiac death | 82Rb | Age, sex, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, family history of premature cad, tobacco use, history of cad, BMI, chest pain, dyspnea, early revascularization, rest LVEF, summed stress score, LVEF reserve | 5.6 (MFR <1.5 vs >2.0) |

| 3.4 (MFR 1.5–2.0 vs [2.0) | ||||||

| Fukushima81 | 224 | 1.0 | MACE (cardiac death, non-fatal mi, late revascularization or catheterization, hospitalization for heart failure) | 82Rb | Age, summed stress score (dichotomized >4) | 2.9 (MFR <2.11 vs ≥2.11) |

| Ziadi84 | 677 | 1.1 | MACE (cardiac death, non-fatal mi, late revascularization, cardiac hospitalization) | 82Rb | History of MI, stress LVEF, summed stress score (dichotomized ≥4) | 3.3 (MFR <2.0 vs >2.0) |

MACE, Major adverse cardiac events; MI, myocardial infarction; CAD, coronary artery disease; BMI, body mass index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MFR, myocardial flow reserve.

Figure 6.

Cardiac mortality by MPR unadjusted Kaplan-Meier cardiac mortality by tertiles of MPR in 2,783 patients referred for PET stress testing. Patients with the lowest perfusion reserve (red <1.5) and intermediate perfusion reserve (blue 1.5–2.0) had a 5.6-fold increased rate of cardiac mortality compared to those with preserved flow reserve (green >2.0) after adjustment for age, sex, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, family history of premature CAD, tobacco use, prior history of CAD, BMI, chest pain, dyspnea, and early revascularization. Adapted with permission from Murthy et al.80 HR, Hazard ratio.

Figure 7.

Risk reclassification by MPR illustration of risk reclassification by addition of MPR to a model containing clinical risk factors, rest and stress imaging findings. The upper horizontal bar graph represents the distribution of risk across categories of <1 (green), 1–3 (blue), and >3% (red) per year risk of cardiac death as estimated by a model containing clinical risk factors, rest LVEF, LVEF reserve and the combination of myocardial scar and ischemia. The pie graphs represent the proportions of patients in each pre-MPR category reassigned to each risk category after the addition of MPR to the risk model. The vertical bar charts at the bottom represent the annualized rates of cardiac mortality in each of the post-MPR risk categories. Adapted with permission from Murthy et al.80

Importantly, an abnormal CFR identified increased risk of cardiac death even among those normal scans by semi-quantitative visual analysis. This likely reflects the observation that vasomotor dysfunction abnormalities are manifested in patients with the earliest stages of atherosclerosis without overt CAD and angiographically normal coronary arteries,85 and have been linked to both disease progression86 and adverse cardiovascular events including sudden death, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and coronary revascularization.87–90

MEDICAL TREATMENT OF CORONARY VASCULAR DYSFUNCTION

Despite growing understanding of the pathophysiologic basis and prognostic significance of coronary vasomotor dysfunction, the treatment implications of this condition remain uncertain. Several standard treatments which have been proven to reduce risk in persons with atherosclerosis including statins91–98 and multiple classes of antihypertensive medications99–117 have been shown to improve CFR with short- to medium-term use. Similarly, exercise118 and weight loss119 have also been shown to improve CFR. All these interventions are already indicated in persons with overt atherosclerosis. However, the impact of these treatments on prognosis in patients with vasodilator abnormalities without overt epicardial coronary atherosclerosis remains uncertain and merits further investigation.

Importantly, in assessing response to treatment, either in the clinic or as part of investigational protocols, regression of plaques is usually modest.120 Improvement of myocardial ischemia by stress perfusion imaging typically demonstrates very small improvements with treatment.121–123 Coronary calcifications are unlikely to regress even in the face of treatments with proven benefit from adverse outcome reduction. Conversely, because vasodilator function is a more dynamic marker of vascular health it may be useful to assess early response to therapies in persons with atherosclerosis, guide further intensification of therapy and encourage sustained patient adherence. The correlation between improvement in vasodilator capacity and decreased risk of adverse cardiac outcomes should be studied further.

IMPLICATIONS FOR ANGIOGRAPHY AND REVASCULARIZATION

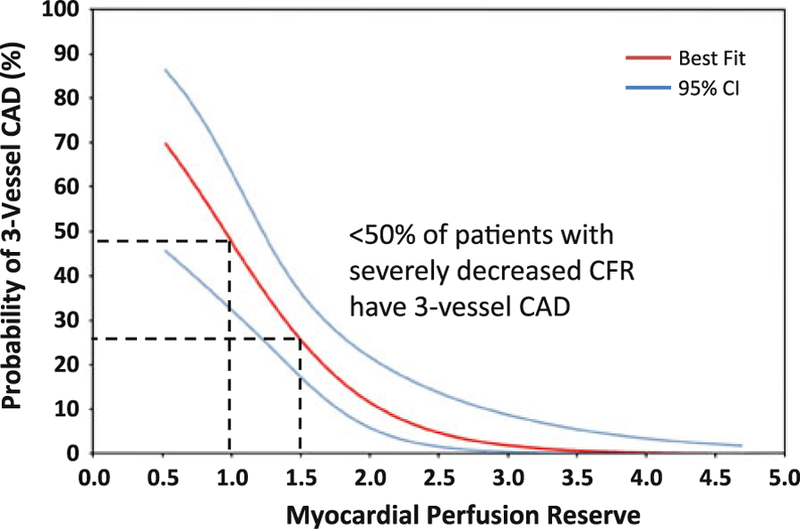

While the use of CFR to identify candidates for medical therapy remains untested, even less certainty exists about how to incorporate CFR into decision making for angiography and revascularization. As discussed above, addition of CFR to other high-risk findings on stress testing may improve identification of patients with high-risk coronary anatomy (i.e., left main or three-vessel coronary disease).56,57 However, because diffuse atherosclerotic changes and microvascular dysfunction can also lower CFR, improvements in sensitivity are likely to be accompanied by loss of specificity and subsequent increase in false positives (Figure 8).57,58 Thus, to avoid unnecessary referrals to angiography, careful consideration must be made of clinical history and imaging findings prior to each referral. Furthermore, the optimal diagnostic thresholds remain undefined and commonly cited values of <2.0 and <1.8 are largely unvalidated. As discussed above, addition of CT coronary angiography may be quite useful as a screen to identify patients in whom the cause of low CFR is obstructive epicardial stenosis as opposed to diffuse atherosclerosis and/or microvascular dysfunction.79

Figure 8.

Probability of three-vessel CAD by MPR unadjusted probability of three-vessel CAD (red line) as a function of MPR with 95% confidence intervals (CI, blue lines). Although there is a clear increase in the proportion of patients with three-vessel CAD as MPR declines, even among patients with severely reduced MPR between 1.0 and 1.5, only a minority have three-vessel disease. Thus, the positive predictive value of reduced MPR is modest. Adapted with permission from Ziadi et al.57

Conversely, increasing evidence124 shows that revascularization guided by ischemia as determined by fractional flow reserve evaluated with a pressure wire in the cardiac catheterization lab leads to better outcomes when compared to angiography-driven revascularization. As such, current guidelines recommend objective documentation of ischemia prior to percutaneous revascularization.125 Potentially, addition of CFR may improve selection of patients who would benefit from angiography and revascularization compared to overt ischemia alone, thereby simultaneously reducing complications and cost of unnecessary angiography while also improving the benefit accrued to those who do undergo revascularization. Data from one large study,80 suggest that even among patients with moderate-to-severe ischemia, global CFR can identify patients with relatively favorable prognosis. Conceivably, these patients may have less benefit (but equal risk) from revascularization. This too deserves further investigation.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite major progress in the evaluation and treatment of coronary artery disease, focus has largely been on epicardial atherosclerosis. Methods to evaluate coronary vasodilator function are rapidly maturing and are complementary to current standard of care. These tools offer the potential to identify earlier stages of atherosclerotic coronary disease as well as to improve risk stratification and selection and titration of medical and revascularization therapies.

Acknowledgments

The work was funded in part by Grants from the National Institutes of Health (RC1 HL101060–01, T32 HL094301–01A1).

Disclosures

Dr Murthy owns equity in General Electric. Dr Di Carli receives research funding from Toshiba.

References

- 1.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001;285:2486–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, et al. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension 2003;42:1206–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith SC, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, Braun LT, Creager MA, Franklin BA, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other athero-sclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update. Circulation 2011;124: 2458–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circu-lation 2012;125:e2–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Labarthe DR, Kottke TE, et al. Explaining the decrease in US deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2388–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Timothy Bricker J, Chaitman BR, Fletcher GF, Froelicher VF, et al. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for exercise testing: Summary article: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (committee to update the 1997 exercise testing guidelines). Circulation 2002;106:1883–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaarsma C, Leiner T, Bekkers SC, Crijns HJ, Wildberger JE, Nagel E, et al. Diagnostic performance of noninvasive myocardial perfusion imaging using single-photon emission computed tomography, cardiac magnetic resonance, and positron emission tomography imaging for the detection of obstructive coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59: 1719–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cerqueira MD, Allman KC, Ficaro EP, Hansen CL, Nichols KJ, Thompson RC, et al. Recommendations for reducing radiation exposure in myocardial perfusion imaging. J Nucl Cardiol 2010;17:709–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salerno M, Beller GA. Noninvasive assessment of myocardial perfusion. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:412–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nygaard TW, Gibson RS, Ryan JM, Gascho JA, Watson DD, Beller GA. Prevalence of high-risk thallium-201 scintigraphic findings in left main coronary artery stenosis: Comparison with patients with multiple- and single-vessel coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 1984;53:462–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss AT, Berman DS, Lew AS, Nielsen J, Potkin B, Swan HJ, et al. Transient ischemic dilation of the left ventricle on stress thallium-201 scintigraphy: A marker of severe and extensive coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1987;9:752–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaughlin MG, Danias PG. Transient ischemic dilation: A powerful diagnostic and prognostic finding of stress myocardial perfusion imaging. J Nucl Cardiol 2002;9:663–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abidov A, Bax JJ, Hayes SW, Cohen I, Nishina H, Yoda S, et al. Integration of automatically measured transient ischemic dilation ratio into interpretation of adenosine stress myocardial perfusion SPECT for detection of severe and extensive CAD. J Nucl Med 2004;45:1999–2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boucher CA, Zir LM, Beller GA, Okada RD, McKusick KA, Strauss HW, et al. Increased lung uptake of thallium-201 during exercise myocardial imaging: Clinical, hemodynamic and angiographic implications in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 1980;46:189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kushner FG, Okada RD, Kirshenbaum HD, Boucher CA, Strauss HW, Pohost GM. Lung thallium-201 uptake after stress testing in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 1981;63:341–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibson RS, Watson DD, Carabello BA, Holt ND, Beller GA. Clinical implications of increased lung uptake of thallium-201 during exercise scintigraphy 2 weeks after myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1982;49:1586–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy R, Rozanski A, Berman DS, Garcia E, Van Train K, Maddahi J, et al. Analysis of the degree of pulmonary thallium washout after exercise in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1983;2:719–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams KA, Schneider CM. Increased stress right ventricular activity on dual isotope perfusion SPECT: A sign of multivessel and/or left main coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999; 34:420–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson LL, Verdesca SA, Aude WY, Xavier RC, Nott LT, Campanella MW, et al. Postischemic stunning can affect left ventricular ejection fraction and regional wall motion on post-stress gated sestamibi tomograms. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;30: 1641–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorbala S, Vangala D, Sampson U, Limaye A, Kwong R, Di Carli MF. Value of vasodilator left ventricular ejection fraction reserve in evaluating the magnitude of myocardium at risk and the extent of angiographic coronary artery disease: A 82Rb PET/ CT study. J Nucl Med 2007;48:349–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berman DS, Kang X, Slomka PJ, Gerlach J, de Yang L, Hayes SW, et al. Underestimation of extent of ischemia by gated SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with left main coronary artery disease. J Nucl Cardiol 2007;14:521–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geleijnse ML, Krenning BJ, van Dalen BM, Nemes A, Soliman OII, Bosch JG, et al. Factors affecting sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic testing: Dobutamine stress echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2009;22:1199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Attenhofer CH, Pellikka PA, Oh JK, Roger VL, Sohn DW, Seward JB. Comparison of ischemic response during exercise and dobutamine echocardiography in patients with left main coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;27:1171–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olson CE, Porter TR, Deligonul U, Xie F, Anderson JR. Left ventricular volume changes during dobutamine stress echocar-diography identify patients with more extensive coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994;24:1268–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andrade MJ, Picano E, Pingitore A, Petix N, Mazzoni V, Landi P, et al. Dipyridamole stress echocardiography in patients with severe left main coronary artery narrowing. Echo Persantine International Cooperative (EPIC) Study Group—Subproject ‘‘Left Main Detection’’. Am J Cardiol 1994;73:450–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenwood JP, Maredia N, Younger JF, Brown JM, Nixon J, Everett CC, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance and single-photon emission computed tomography for diagnosis of coronary heart disease (CE-MARC): A prospective trial. Lancet 2012;379:453–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwitter J, Wacker CM, Wilke N, Al-Saadi N, Sauer E, Huettle K, et al. MR-IMPACT II: Magnetic resonance imaging for myocardial perfusion assessment in coronary artery disease trial: Perfusion-cardiac magnetic resonance vs. single-photon emission computed tomography for the detection of coronary artery disease: A comparative multicentre, multivendor trial. Eur Heart J March 4, 2012. http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2012/03/04/eurheartj.ehs022. Accessed March 12, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sasaki T, Hansford R, Zviman MM, Kolandaivelu A, Bluemke DA, Berger RD, et al. Quantitative assessment of artifacts on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging of patients with pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Circulation: Cardio-vascular imaging 2011. http://circimaging.ahajournals.org/content/early/2011/09/23/CIRCIMAGING.111.965764.abstract. Accessed September 25, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paech DC, Weston AR. A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of 64-slice or higher computed tomography angiography as an alternative to invasive coronary angiography in the investigation of suspected coronary artery disease. BMC Car-diovasc Disord 2011;11:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamarappoo BK, Gutstein A, Cheng VY, Nakazato R, Gransar H, Dey D, et al. Assessment of the relationship between stenosis severity and distribution of coronary artery stenoses on multislice computed tomographic angiography and myocardial ischemia detected by single photon emission computed tomography. J Nucl Cardiol 2010;17:791–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunadian V, Harrigan C, Zorkun C, Palmer AM, Ogando KJ, Biller LH, et al. Use of the TIMI frame count in the assessment of coronary artery blood flow and microvascular function over the past 15 years. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2009;27:316–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porto I, Hamilton-Craig C, Brancati M, Burzotta F, Galiuto L, Crea F. Angiographic assessment of microvascular perfusion-myocardial blush in clinical practice. Am Heart J 2010;160: 1015–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson NP, Kirkeeide RL, Gould KL. Is discordance of coronary flow reserve and fractional flow reserve due to methodology or clinically relevant coronary pathophysiology? J Am Coll Cardiol Imaging 2012;5:193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim MJ, Kern MJ. Coronary pathophysiology in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Curr Probl Cardiol 2006;31:493–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El Fakhri G, Sitek A, Guerin B, Kijewski MF, Di Carli MF, Moore SC. Quantitative dynamic cardiac 82Rb PET using generalized factor and compartment analyses. J Nucl Med 2005;46: 1264–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Carli MF, Dorbala S, Meserve J, El Fakhri G, Sitek A, Moore SC. Clinical myocardial perfusion PET/CT. J Nucl Med 2007;48:783–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshida K, Mullani N, Gould KL. Coronary flow and flow reserve by PET simplified for clinical applications using rubidium-82 or nitrogen-13-ammonia. J Nucl Med 1996;37:1701–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El Fakhri G, Kardan A, Sitek A, Dorbala S, Abi-Hatem N, Lahoud Y, et al. Reproducibility and accuracy of quantitative myocardial blood flow assessment with 82Rb PET: Comparison with 13N-ammonia PET. J Nucl Med 2009;50:1062–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu M, Guaraldi MT, Mistry M, Kagan M, McDonald JL, Drew K, et al. BMS-747158–02: A novel PET myocardial perfusion imaging agent. J Nucl Cardiol 2007;14:789–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nekolla SG, Reder S, Saraste A, Higuchi T, Dzewas G, Preissel A, et al. Evaluation of the novel myocardial perfusion positronemission tomography tracer 18F-BMS-747158–02: Comparison to 13N-ammonia and validation with microspheres in a pig model. Circulation 2009;119:2333–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu M, Bozek J, Guaraldi M, Kagan M, Azure M, Robinson SP. Cardiac imaging and safety evaluation of BMS747158, a novel PET myocardial perfusion imaging agent, in chronic myocardial compromised rabbits. J Nucl Cardiol 2010;17:631–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huisman MC, Higuchi T, Reder S, Nekolla SG, Poethko T, Wester H-J, et al. Initial characterization of an 18F-labeled myocardial perfusion tracer. J Nucl Med 2008;49:630–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sherif HM, Nekolla SG, Saraste A, Reder S, Yu M, Robinson S, et al. Simplified quantification of myocardial flow reserve with flurpiridaz F 18: Validation with microspheres in a pig model. J Nucl Med 2011;52:617–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maddahi J, Czernin J, Lazewatsky J, Huang S-C, Dahlbom M, Schelbert H, et al. Phase I, first-in-human study of BMS747158, a novel 18F-labeled tracer for myocardial perfusion PET: Dosimetry, biodistribution, safety, and imaging characteristics after a single injection at rest. J Nucl Med 2011;52:1490–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jerosch-Herold M Quantification of myocardial perfusion by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2010;12:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jerosch-Herold M, Wilke N, Stillman AE, Wilson RF. Magnetic resonance quantification of the myocardial perfusion reserve with a Fermi function model for constrained deconvolution. Med Phys 1998;25:73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sicari R, Nihoyannopoulos P, Evangelista A, Kasprzak J, Lancellotti P, Poldermans D, et al. Stress echocardiography expert consensus statement: European Association of Echocar-diography (EAE) (a registered branch of the ESC). Eur J Echocardiogr 2008;9:415–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wei K, Jayaweera AR, Firoozan S, Linka A, Skyba DM, Kaul S. Quantification of myocardial blood flow with ultrasound-induced destruction of microbubbles administered as a constant venous infusion. Circulation 1998;97:473–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Christian T, Frankish M, Sisemoore J, Christian M, Gentchos G, Bell S, et al. Myocardial perfusion imaging with first-pass computed tomographic imaging: Measurement of coronary flow reserve in an animal model of regional hyperemia. J Nucl Cardiol 2010;17:625–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ho K-T, Chua K-C, Klotz E, Panknin C. Stress and rest dynamic myocardial perfusion imaging by evaluation of complete time-attenuation curves with dual-source CT. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2010;3:811–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Breault C, Roth N, Slomka PJ, Moore SC, Park M, Sitek A, et al. Quantification of myocardial perfusion reserve using dynamic SPECT imaging in humans Mosby-Year Book Inc: Philadelphia, PA; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uren NG, Melin JA, De Bruyne B, Wijns W, Baudhuin T, Camici PG. Relation between myocardial blood flow and the severity of coronary-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 1994;330: 1782–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Di Carli M, Czernin J, Hoh CK, Gerbaudo VH, Brunken RC, Huang S-C, et al. Relation among stenosis severity, myocardial blood flow, and flow reserve in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 1995;91:1944–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beanlands RSB, Muzik O, Melon P, Sutor R, Sawada S, Muller D, et al. Noninvasive quantification of regional myocardial flow reserve in patients with coronary atherosclerosis using nitrogen-13 ammonia positron emission tomography: Determination of extent of altered vascular reactivity. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;26: 1465–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anagnostopoulos C, Almonacid A, Fakhri G, Curillova Z, Sitek A, Roughton M, et al. Quantitative relationship between coronary vasodilator reserve assessed by 82Rb PET imaging and coronary artery stenosis severity. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2008;35: 1593–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parkash R, de Kemp RA, Ruddy TD, Kitsikis A, Hart R, Beau-chesne L, et al. Potential utility of rubidium 82 PET quantification in patients with 3-vessel coronary artery disease. J Nucl Cardiol 2004;11:440–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ziadi MC, Dekemp RA, Williams K, Guo A, Renaud JM, Chow BJW, et al. Does quantification of myocardial flow reserve using rubidium-82 positron emission tomography facilitate detection of multivessel coronary artery disease? J Nucl Cardiol March 14, 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22415819, Accessed March 19, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Naya M, Murthy VL, Klein J, Foster CR, Gaber M, Oba K, et al. Integrating semiquantitative measures of myocardial ischemia and quantitative coronary flow reserve assessed by 82Rubidium PET for the detection of multivessel coronary artery disease. J Nucl Med 2012;53:1872.23071350 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fujiwara M, Tamura T, Yoshida K, Nakagawa K, Nakao M, Yamanouchi M, et al. Coronary flow reserve in angiographically normal coronary arteries with one-vessel coronary artery disease without traditional risk factors. Eur Heart J 2001;22:479–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Bruyne B, Hersbach F, Pijls NHJ, Bartunek J, Bech J-W, Heyndrickx GR, et al. Abnormal epicardial coronary resistance in patients with diffuse atherosclerosis but ‘‘normal’’ coronary angiography. Circulation 2001;104:2401–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Laine H, Raitakari OT, Niinikoski H, Pitkänen O-P, Iida H, Viikari J, et al. Early impairment of coronary flow reserve in young men with borderline hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32:147–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dayanikli F, Grambow D, Muzik O, Mosca L, Rubenfire M, Schwaiger M. Early detection of abnormal coronary flow reserve in asymptomatic men at high risk for coronary artery disease using positron emission tomography. Circulation 1994;90:808–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaufmann PA, Gnecchi-Ruscone T, Schäfers KP, Lüscher TF, Camici PG. Low density lipoprotein cholesterol and coronary microvascular dysfunction in hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:103–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iwado Y, Yoshinaga K, Furuyama H, Ito Y, Noriyasu K, Katoh C, et al. Decreased endothelium-dependent coronary vasomotion in healthy young smokers. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2002;29:984–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Campisi R, Czernin J, Schoder H, Sayre JW, Marengo FD, Phelps ME, et al. Effects of long-term smoking on myocardial blood flow, coronary vasomotion, and vasodilator capacity. Circulation 1998;98:119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martin JW, Briesmiester K, Bargardi A, Muzik O, Mosca L, Duvernoy CS. Weight changes and obesity predict impaired resting and endothelium-dependent myocardial blood flow in postmenopausal women. Clin Cardiol 2005;28:13–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Motivala AA, Rose PA, Kim HM, Smith YR, Bartnik C, Brook RD, et al. Cardiovascular risk, obesity, and myocardial blood flow in postmenopausal women. J Nucl Cardiol 2008;15:510–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Di Carli MF, Charytan D, McMahon GT, Ganz P, Dorbala S, Schelbert HR. Coronary circulatory function in patients with the metabolic syndrome. J Nucl Med 2011;52:1369–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Di Carli MF, Afonso L, Campisi R, Ramappa P, Bianco-Batlles D, Grunberger G, et al. Coronary vascular dysfunction in premenopausal women with diabetes mellitus. Am Heart J 2002;144:711–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yokoyama I, Momomura S, Ohtake T, Yonekura K, Nishikawa J, Sasaki Y, et al. Reduced myocardial flow reserve in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;30:1472–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Di Carli MF, Janisse J, Ager J, Grunberger G. Role of chronic hyperglycemia in the pathogenesis of coronary microvascular dysfunction in diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1387–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Charytan DM, Shelbert HR, Di Carli MF. Coronary microvas-cular function in early chronic kidney disease/clinical perspective. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2010;3:663–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Quyyumi AA, Dakak N, Andrews NP, Husain S, Arora S, Gilligan DM, et al. Nitric oxide activity in the human coronary circulation. Impact of risk factors for coronary atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest 1995;95:1747–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cox DA, Vita JA, Treasure CB, Fish RD, Alexander RW, Ganz P, et al. Atherosclerosis impairs flow-mediated dilation of coronary arteries in humans. Circulation 1989;80:458–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Curillova Z, Yaman BF, Dorbala S, Kwong RY, Sitek A, Fakhri G, et al. Quantitative relationship between coronary calcium content and coronary flow reserve as assessed by integrated PET/ CT imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2009;36:1603–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Beltrame JF, Limaye SB, Wuttke RD, Horowitz JD. Coronary hemodynamic and metabolic studies of the coronary slow flow phenomenon. Am Heart J 2003;146:84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Johnson BD, Shaw LJ, Buchthal SD, Bairey Merz CN, Kim H-W, Scott KN, et al. Prognosis in women with myocardial ischemia in the absence of obstructive coronary disease: Results from the National Institutes of Health-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-Sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE). Circulation 2004;109:2993–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Suzuki H, Takeyama Y, Koba S, Suwa Y, Katagiri T. Small vessel pathology and coronary hemodynamics in patients with microvascular angina. Int J Cardiol 1994;43:139–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kajander S, Joutsiniemi E, Saraste M, Pietila M, Ukkonen H, Saraste A, et al. Cardiac positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging accurately detects anatomically and functionally significant coronary artery disease. Circulation 2010;122:603–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Murthy VL, Naya M, Foster CR, Hainer J, Gaber M, Di Carli G, et al. Improved cardiac risk assessment with noninvasive measures of coronary flow reserve. Circulation 2011;124:2215–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fukushima K, Javadi MS, Higuchi T, Lautamaki R, Merrill J, Nekolla SG, et al. Prediction of short-term cardiovascular events using quantification of global myocardial flow reserve in patients referred for clinical 82Rb PET perfusion imaging. J Nucl Med 2011;52:726–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Herzog BA, Husmann L, Valenta I, Gaemperli O, Siegrist PT, Tay FM, et al. Long-term prognostic value of 13N-ammonia myocardial perfusion positron emission tomography: Added value of coronary flow reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:150–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tio RA, Dabeshlim A, Siebelink H-MJ, de Sutter J, Hillege HL, Zeebregts CJ, et al. Comparison between the prognostic value of left ventricular function and myocardial perfusion reserve in patients with ischemic heart disease. J Nucl Med 2009;50:214–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ziadi MC, deKemp RA, Williams KA, Guo A, Chow BJW, Renaud JM, et al. Impaired myocardial flow reserve on rubidium-82 positron emission tomography imaging predicts adverse out-comes in patients assessed for myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:740–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zeiher A, Drexler H, Wollschlager H, Just H. Endothelial dys-function of the coronary microvasculature is associated with coronary blood flow regulation in patients with early athero-sclerosis. Circulation 1991;84:1984–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schachinger V, Britten MB, Zeiher AM. Prognostic impact of coronary vasodilator dysfunction on adverse long-term outcome of coronary heart disease. Circulation 2000;101:1899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Halcox JPJ, Schenke WH, Zalos G, Mincemoyer R, Prasad A, Waclawiw MA, et al. Prognostic value of coronary vascular endothelial dysfunction. Circulation 2002;106:653–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Suwaidi JA, Hamasaki S, Higano ST, Nishimura RA, Holmes DR, Lerman A. Long-term follow-up of patients with mild cor-onary artery disease and endothelial dysfunction. Circulation 2000;101:948–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.von Mering GO, Arant CB, Wessel TR, McGorray SP, Bairey Merz CN, Sharaf BL, et al. Abnormal coronary vasomotion as a prognostic indicator of cardiovascular events in women: Results from the national heart, lung, and blood institute-sponsored women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation (WISE). Circulation 2004;109:722–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cecchi F, Olivotto I, Gistri R, Lorenzoni R, Chiriatti G, Camici PG. Coronary microvascular dysfunction and prognosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1027–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Huggins GS, Pasternak RC, Alpert NM, Fischman AJ, Gewirtz H. Effects of short-term treatment of hyperlipidemia on coronary vasodilator function and myocardial perfusion in regions having substantial impairment of baseline dilator reverse. Circulation 1998;98:1291–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ishida K, Geshi T, Nakano A, Uzui H, Mitsuke Y, Okazawa H, et al. Beneficial effects of statin treatment on coronary micro-vascular dysfunction and left ventricular remodeling in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2012;155:442–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Alexanderson E, García-Rojas L, Jiménez M, Jácome R, Calleja R, Martínez A, et al. Effect of ezetimibe-simvastatine over endothelial dysfunction in dyslipidemic patients: Assessment by 13N-ammonia positron emission tomography. J Nucl Cardiol 2010;17:1015–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hong SJ, Choi SC, Kim JS, Shim WJ, Park SM, Ahn CM, et al. Low-dose versus moderate-dose atorvastatin after acute myocardial infarction: 8-month effects on coronary flow reserve and angiogenic cell mobilisation. Heart 2010;96:756–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Baller D, Notohamiprodjo G, Gleichmann U, Holzinger J, Weise R, Lehmann J. Improvement in coronary flow reserve determined by positron emission tomography after 6 months of cholesterol-lowering therapy in patients with early stages of coronary ath-erosclerosis. Circulation 1999;99:2871–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fujimoto K, Hozumi T, Watanabe H, Shimada K, Takeuchi M, Sakanoue Y, et al. Effect of fluvastatin therapy on coronary flow reserve in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol 2004;93:1419–21. A10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Takagi A, Tsurumi Y, Ishizuka N, Omori H, Arai K, Hagiwara N, et al. Single administration of cerivastatin, an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, improves the coronary flow velocity reserve: A transthoracic Doppler echocardiography study. Heart Vessels 2006;21:298–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ilveskoski E, Lehtimäki T, Laaksonen R, Janatuinen T, Vesalainen R, Nuutila P, et al. Improvement of myocardial blood flow by lipid-lowering therapy with pravastatin is modulated by apolipoprotein E genotype. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2007;67:723–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Akinboboye OO, Chou R-L, Bergmann SR. Augmentation of myocardial blood flow in hypertensive heart disease by angio-tensin antagonists: A comparison of lisinopril and losartan. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40:703–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Masuda D, Nohara R, Tamaki N, Hosokawa R, Inada H, Hirai T, et al. Evaluation of coronary blood flow reserve by13 N-NH3 positron emission computed tomography (PET) with dipyridamole in the treatment of hypertension with the ACE inhibitor (Cilazapril). Ann Nucl Med 2000;14:353–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chen J-W, Hsu N-W, Wu T-C, Lin S-J, Chang M-S. Long-term angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition reduces plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine and improves endothelial nitric oxide bioavailability and coronary microvascular function in patients with syndrome X. Am J Cardiol 2002;90:974–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kawata T, Daimon M, Hasegawa R, Teramoto K, Toyoda T, Sekine T, et al. Effect on coronary flow velocity reserve in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Comparison between angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist. Am Heart J 2006;151:798.e9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kawata T, Daimon M, Hasegawa R, Teramoto K, Toyoda T, Sekine T, et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor on serum asymmetric dimethylarginine and coronary circulation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Cardiol 2009;132:286–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hinoi T, Tomohiro Y, Kajiwara S, Matsuo S, Fujimoto Y, Yamamoto S, et al. Telmisartan, an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, improves coronary microcirculation and insulin resistance among essential hypertensive patients without left ventricular hypertrophy. Hypertens Res 2008;31:615–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pauly DF, Johnson BD, Anderson RD, Handberg EM, Smith KM, Cooper-DeHoff RM, et al. In women with symptoms of cardiac ischemia, nonobstructive coronary arteries, and micro-vascular dysfunction, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition is associated with improved microvascular function: A double-blind randomized study from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE). Am Heart J 2011;162:678–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schneider CA, Voth E, Moka D, Baer FM, Melin J, Bol A, et al. Improvement of myocardial blood flow to ischemic regions by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition with quinaprilat IV: A study using [15O] water dobutamine stress positron emission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;34:1005–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Motz W, Strauer BE. Improvement of coronary flow reserve after long-term therapy with enalapril. Hypertension 1996;27:1031–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kamezaki F, Tasaki H, Yamashita K, Shibata K, Hirakawa N, Tsutsui M, et al. Angiotensin receptor blocker improves coronary flow velocity reserve in hypertensive patients: Comparison with calcium channel blocker. Hypertens Res 2007;30:699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Xiaozhen H, Yun Z, Mei Z, Yu S. Effect of carvedilol on coronary flow reserve in patients with hypertensive left-ventricular hypertrophy. Blood Press 2010;19:40–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Böttcher M, Czernin J, Sun K, Phelps ME, Schelbert HR. Effect of beta 1 adrenergic receptor blockade on myocardial blood flow and vasodilatory capacity. J Nucl Med 1997;38:442–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Billinger M, Seiler C, Fleisch M, Eberli FR, Meier B, Hess OM. Do beta-adrenergic blocking agents increase coronary flow reserve? J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:1866–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gullu H, Erdogan D, Caliskan M, Tok D, Yildirim I, Sezgin AT, et al. Different effects of atenolol and nebivolol on coronary flow reserve. Heart 2006;92:1690–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Erdogan D, Gullu H, Caliskan M, Ciftci O, Baycan S, Yildirir A, et al. Nebivolol improves coronary flow reserve in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart 2007;93:319–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Neglia D, De Maria R, Masi S, Gallopin M, Pisani P, Pardini S, et al. Effects of long-term treatment with carvedilol on myocardial blood flow in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart 2007;93:808–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Togni M, Vigorito F, Windecker S, Abrecht L, Wenaweser P, Cook S, et al. Does the beta-blocker nebivolol increase coronary flow reserve? Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2007;21:99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Galderisi M, D’Errico A, Sidiropulos M, Innelli P, de Divitiis O, de Simone G. Nebivolol induces parallel improvement of left ventricular filling pressure and coronary flow reserve in uncomplicated arterial hypertension. J Hypertens 2009;27:2108–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zervos G, Zusman RM, Swindle LA, Alpert NM, Fischman AJ, Gewirtz H. Effects of nifedipine on myocardial blood flow and systolic function in humans with ischemic heart disease. Coron Artery Dis 1999;10:185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yoshinaga K, Beanlands RSB, deKemp RA, Lortie M, Morin J, Aung M, et al. Effect of exercise training on myocardial blood flow in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 2006;151:1324.e11–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Coppola A, Marfella R, Coppola L, Tagliamonte E, Fontana D, Liguori E, et al. Effect of weight loss on coronary circulation and adiponectin levels in obese women. Int J Cardiol 2009;134:414–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Sipahi I, Libby P, Raichlen JS, Ballan-tyne CM, et al. Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: The ASTEROID trial. JAMA 2006;295:1556–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gould KL, Ornish D, Scherwitz L, Brown S, Edens RP, Hess MJ, et al. Changes in myocardial perfusion abnormalities by positron emission tomography after long-term, intense risk factor modification. JAMA 1995;274:894–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Venkataraman R, Belardinelli L, Blackburn B, Heo J, Iskandrian AE. A study of the effects of ranolazine using automated quantitative analysis of serial myocardial perfusion images. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:1301–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Venkataraman R, Aljaroudi W, Belardinelli L, Heo J, Iskandrian AE. The effect of ranolazine on the vasodilator-induced myocardial perfusion abnormality. J Nucl Cardiol 2011;18:456–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Tonino PAL, De Bruyne B, Pijls NHJ, Siebert U, Ikeno F, van ‘t Veer M, et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med 2009;360:213–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Smith SC Jr, Feldman TE, Hirshfeld JW Jr, Jacobs AK, Kern MJ, King SB III, et al. ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/SCAI Writing Committee to Update 2001 Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention). Circulation 2006;113:e166–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]