Abstract

Network science approaches can enhance global and national coordinated efforts to prevent and manage non-communicable diseases, say Ruth Hunter and colleagues

Recent figures highlight the rising global burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs),1 and tackling this problem requires global coordinated action. Behavioural risk factors for NCDs at both individual and population level are increasingly recognised to be influenced by multiple factors interacting across multiple sectors.2 3 4 No single organisation or sector can therefore solve the problem alone.5 It requires multipronged action across various sectors. The myriad political, economic, environmental, interpersonal, and individual factors are inter-related through a complex and often non-linear feedback process and interactions that give rise to an adaptable system that can be modelled.

Importance of multisectoral collaboration

The global action plan for reducing NCDs published by the World Health Organization outlines “best buys” for tackling key risk factors such as tobacco use, physical inactivity, the harmful use of alcohol, and unhealthy diets. The plan provides policy makers with a menu of policy options to reduce NCDs5 and recommends multisectoral action engaging all of government as well as academia, non-governmental organisations, philanthropies, and the private sector. Stakeholders encompass different levels of governance, including national, subnational, and municipal councils. Thus, the engagement of the whole of government and whole of society is necessary to support countries to reduce NCDs.

Action on NCDs needs to come not only from the health sector but also organisations and agencies that operate outside the traditional sphere of health, such as non-profits, schools, businesses, and other governmental agencies, including transport, planning, and education. Therefore, building national action plans requires the development and implementation of cross-sectoral and multistakeholder networks that can provide a synergistic, concerted, and coherent approach to prevention of these diseases and their risk factors.

A major challenge is how these diverse organisations, agencies, and groups can develop meaningful partnerships to tackle shared goals in population health. Traditionally, organisations are used to working within single sectors rather than across them,6 and there is little guidance on how best to effectively develop, manage, and maintain a national stakeholder network. A systems approach can also be useful within organisations, providing a better appreciation of how organisations are structured and highlighting the tendencies to operate in silos. A shift in culture to a network approach could therefore have wider benefits.

Operationalising multisectoral partnerships as networks

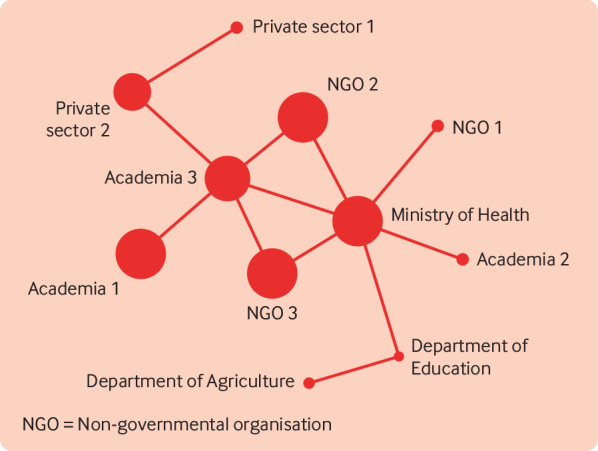

Conceptualising multisectoral partnerships as networks (fig 1) allows use of stakeholder network analysis techniques and network theories to determine how they can be more effective in reducing NCDs.7 Stakeholder network analyses can help clarify which organisations are connected to each other and how. They can also measure the quality of these connections, with the resulting data used to strengthen ties.

Fig 1.

Example of a public health stakeholder network.6 The nodes represent organisations and the lines represent ties between organisations. The larger nodes represent the organisations with the most collaborators

Stakeholder analyses can identify the organisations involved in implementing interventions for prevention and control of NCDs and how they are linked; describe the structure and characteristics of the network—how its participants communicate with each other and how influential they are; and identify areas and strategies to strengthen the participation of key stakeholders. A visual representation of the network helps members to better understand the network and identify priorities to make the network more robust and collaborative—for example, by establishing relationships between stakeholders that are disconnected, identifying areas where new stakeholders need to be recruited, and facilitating sharing of resources and knowledge. Understanding how a stakeholder network is organised can empower and promote self management among the network members.

Varda et al outlined the core dimensions of connectivity in public health collaboratives.6 These include factors such as membership (name, type, and characteristics such as size); network interaction (key players, patterns, and positions occupied); the role of the Ministry of Health (such as convenor, facilitator, or equal member); the frequency of interactions; and issues of power, involvement, resources, trust, and reciprocity. An understanding of these factors could help increase efficiency, effectiveness, and sustainability of stakeholder networks.8 9 10 It increases the likelihood that goals will be met because tasks and efforts are shared and policies and programmes are optimised.

However, such high level networks risk burnout as often there is little funding or resources to support the work; overuse, especially as some individuals are commonly involved in several high level networks; and collaborative failure. Furthermore, once networks are set up they can be difficult to sustain over the longer term, particularly in a dynamic setting where people regularly change job roles or organisations and agendas change to adapt to the most urgent priorities.

Role of network science

The sustainability of any efforts to support implementation of interventions for NCDs at both individual and organisational levels will depend on the strength and empowerment of the interorganisational networks. An assessment of the processes that facilitate or inhibit the effective implementation of national NCD action plans will form an integral part of this programme of work. This can be done using methods that draw from complexity science,11 including established stakeholder network analysis tools and techniques.7

For example, the strength and extent of network ties between the stakeholders—in terms of reciprocal relationships, trust, exchange of information, and technical assistance—can be evaluated using mathematical parameters describing the network (box 1).7 These include the network density (the proportion of possible ties in a network that actually exist), the number of ties to and from a stakeholder (degree, used to determine opinion leaders), and the frequency with which certain organisations or individuals connect others in the network (betweenness). The quality of ties can be measured and actions identified to improve them, increasing efficiency and reducing redundancy. Clustering coefficients and community detection algorithms, which assess the density of connections between organisations, can be used to identify important subnetworks—for example, those focused on specific NCD priorities.

Box 1. Common network terminology.

Network—Set of nodes and set of ties representing entities (ie, organisations) and the relationship(s) between them

Node—Representation of an organisation or individual. Also called actor or vertex

Tie—Representation of a relationship between a pair of entities, such as friendship or shares needles with (for people) or trades with (for business or nation). Also called edge, arc, or link

Density—The proportion of all possible ties that are actually present in the network. The density of a network may give us insights into the speed at which information diffuses among the nodes

Degree—The number of ties attached to the given node. For example, the number of organisations that the ministry of health thinks of as collaborator

Clustering coefficient—The proportion of potential ties between a node’s neighbours that are actual ties. For example, the proportion of organisations of the ministry of health’s collaborators who are also collaborators with each other

Closeness—The average distance (number of edges on shortest path) to each other node in the network

Community detection algorithm—The use of mathematical algorithms to identify important subnetworks

Betweenness—The number of shortest paths between pairs of nodes that pass through the given node

Clique—A subset of nodes where each node has ties with all other nodes

Community—A subset of nodes with relatively high tie density, so the nodes are mostly connected to other nodes in the community rather than the rest of the network

Homophily—Tendency to form relationship with nodes with a characteristic in common

Stakeholder network analysis provides a means to study microstructural and macrostructural changes that affect the sustainability of the implementation. The hierarchical transformation of networks through the formation of cliques or communities among stakeholders can shed light on the dynamic and emergent nature of the relationships. Using network science and qualitative inquiry12 13 to investigate how the nature, roles, and relationships between stakeholders evolve and affect the implementation of NCD prevention and management plans can provide information to strengthen the implementation of national action plans. Activities such as multisectoral stakeholder meetings and communities of practice could also be enhanced through network approaches. For example, communities of practice—groups of people with a common goal working and learning together—can use network approaches to share resources more efficiently, such as new funding opportunities for NCD control, and diffuse information effectively throughout the network.

Network theory

Network theories can provide a unique perspective into how to improve collaborative efforts regarding NCD prevention and control. For example, the concept of homophily suggests that organisations with similar characteristics will tend to collaborate together and form strong ties.7 However, diversity in ties is important for introducing new knowledge and spreading new behaviours through a network. Granovetter’s strength of weak ties theory14 argues that indirect and weak ties (eg, acquaintances) are usually unconnected to the rest of an organisation’s network and therefore more likely to introduce new information or behaviour. In contrast, when ties are highly clustered (ie, people in an organisation’s network are close contacts) their information is already known to the organisation. This theory suggests that having many stakeholders is not necessarily better. Organisations need to cultivate weak ties and maintain a diverse set of contacts to be able to access resources and information critical to survival and success.

Burt developed this theory further when he noted that weak ties spanned “structural holes” (a gap between individuals or organisations in the network who have similar sources of information or similar positional advantages or disadvantages) in the network.15 16 He suggested that organisations or individuals who occupy structural holes hold critical positions in the network that enable them to be more efficient and effective in diffusing information. This supports the idea that “less is more,” whereby fewer connections to several groups provide greater opportunity for sharing of information, resources, and innovation. For example, an individual or organisation acting as a mediator or bridge between two or more closely connected groups will be well placed to transfer or act as gatekeeper of information, knowledge, or resources between groups. Ministries of health often have the role of gatekeeper in NCD prevention and control as they are usually a central, well connected member of such networks.

Network intervention approaches

Better understanding of the structure, characteristics, and function of stakeholder networks has led to novel interventions to improve their efficiency and effectiveness. Data captured using network analysis techniques can be used to accelerate and improve stakeholder network performance. A landmark paper by Valente in 2012 set out a taxonomy of network intervention approaches.18 Two approaches could be relevant to NCD specific stakeholder networks. Interventions can engage “individuals” who are selected on the basis of some network property and who may have greater roles in providing information or support within their network. For example, there are many mathematical algorithms available to identify central nodes (organisations) in the network. Nodes identified as having the highest “centrality betweenness”—being the shortest connection between other organisations—typically occupy critical gatekeeping positions and would have an important role in sharing information on NCD programmes across fragmented networks, thereby improving efficiency of implementation.

The second approach is known as segmentation and considers networks to have core members with dense connections and periphery members with looser connections.19 Valente suggests that the core members are key to mobilising networks, for example, to advocate for change, and to share information and resources.18 Public health partnerships are often composed of many organisations and individuals, but the core working group may be fewer than 15 organisations. Stakeholder network analyses can help understand who is part of the core and can therefore help with equal distribution of resources.

Conclusion

Global and national prevention and management of NCDs requires effective multisectoral partnerships. Such partnerships could benefit from using network science approaches. For example, network functions such as advocating for resources could be enhanced by using network science approaches to identify the key factors for achieving change in population behaviour. To advocate for better green infrastructure to promote physical activity, for example, requires a range of actors, such as government departments of planning, health, and finance, alongside urban planners, local NGOs, and local authorities,

Stakeholder network analysis techniques can help us better understand multistakeholder networks. The data can be used to inform the development of networks to tackle NCDs and improve their efficiency, effectiveness, and sustainability. However, such approaches must account for the dynamic context of these networks, with members, aims, and objectives changing as the work develops.21 22 Understanding the structure of the network can empower its members and foster self management, facilitating the identification of ways in which new relationships may have greater impact. Changing how we prepare for and deal with network management could improve the quality, robustness, and sustainability of policies and initiatives.

Key messages.

The prevention and management of NCDs requires global, multisectoral, and multistakeholder action

Current national coordination efforts are often not as effective as they could be and are challenging to sustain

Network science can be used to better understand collaboration and how it can be improved

Information from network analysis could enhance global and national efforts to prevent and manage NCDs

For other articles in the series see www.bmj.com/NCD-solutions

Contributors and sources:All authors have experience in stakeholder network analyses, working together on a range of projects led by RH investigating multisectoral stakeholder networks in NCD prevention and control. RH led the writing of the first draft of the article and all authors provided input on earlier drafts and approved the final version. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the institutions to which they are affiliated.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of a series proposed by the WHO Global Coordination Mechanism on NCDs and commissioned by The BMJ, which peer reviewed, edited, and made the decision to publish. Open access fees are funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA), UNOPS Defeat-NCD Partnership, Government of the Russian Federation, and WHO..

References

- 1. Bennett JE, Stevens GA, Mathers CD, et al. NCD Countdown 2030 collaborators NCD Countdown 2030: worldwide trends in non-communicable disease mortality and progress towards Sustainable Development Goal target 3.4. Lancet 2018;392:1072-88. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31992-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Diez Roux AV. Complex systems thinking and current impasses in health disparities research. Am J Public Health 2011;101:1627-34. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rutter H, Savona N, Glonti K, et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet 2017;390:2602-4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31267-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sterman JD. Learning from evidence in a complex world. Am J Public Health 2006;96:505-14. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Tackling NCDs: ‘Best buys’ and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. 2017. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259232/WHO-NMH-NVI-17.9-eng.pdf;jsessionid=CBE31FD1C1A4EADFB3D22AB8A7010FCB?sequence=1

- 6. Varda DM, Chandra A, Stern SA, Lurie N. Core dimensions of connectivity in public health collaboratives. J Public Health Manag Pract 2008;14:E1-7. 10.1097/01.PHH.0000333889.60517.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hanneman RA, Riddle M. Introduction to social network methods. Riverside, CA. University of California, 2005. http://faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wipfli HL, Fujimoto K, Valente TW. Global tobacco control diffusion: the case of the framework convention on tobacco control. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1260-6. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.167833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yousefi-Nooraie R, Dobbins M, Marin A, Hanneman R, Lohfeld L. The evolution of social networks through the implementation of evidence-informed decision-making interventions: a longitudinal analysis of three public health units in Canada. Implement Sci 2015;10:166. 10.1186/s13012-015-0355-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Popelier L. A scoping review on the current and potential use of social network analysis for evaluation purposes. Evaluation 2018;24:325-52 10.1177/1356389018782219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. May CR, Johnson M, Finch T. Implementation, context and complexity. Implement Sci 2016;11:141. 10.1186/s13012-016-0506-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dominguez S, Hollstein B. Mixed methods social networks research design and applications. Cambridge University Press, 2014. 10.1017/CBO9781139227193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yamasaki S, Spreitzer A. Beyond methodological tenets. The worlds of QCA and SNA and their benefits to policy analysis. In: Innovative comparative methods for policy analysis. Springer Link, 2006: 95-120. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Granovetter MS. The strength of ties. Am J Sociol 1973;78:1360-80 10.1086/225469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Burt RS. Structural holes: the social structure of competition. Harvard University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Burt RS. Brokerage and closure: an introduction to social capital. Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Papoutsi C, et al. Analysing the role of complexity in explaining the fortunes of technology programmes: empirical application of the NASSS framework. BMC Med 2018;16:66. 10.1186/s12916-018-1050-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Valente TW. Network interventions. Science 2012;337:49-53. 10.1126/science.1217330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Borgatti SP, Everett MG. Models of core/periphery structure. Soc Networks 2000;21:375 10.1016/S0378-8733(99)00019-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Badham J, Kee F, Hunter RF. Simulating network intervention strategies: Implications for adoption of behaviour. Netw Sci 2018;6:265-80 10.1017/nws.2018.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Koleros A, Mulkerne S, Oldenbeuving M, Stein D. The actor-based change framework: A pragmatic approach to developing program theory for interventions in complex systems. Am J Eval 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1177/1098214018786462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ling T. Evaluating complex and unfolding interventions in real time. Evaluation 2012;18:79-91. 10.1177/1356389011429629. [DOI] [Google Scholar]