Abstract

Methylphenidate (MP) is a widely prescribed psychostimulant used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Previously, we established a drinking paradigm to deliver MP to rats at doses that result in pharmacokinetic profiles similar to treated patients. In the present study, adolescent male rats were assigned to one of three groups: control (water), low-dose MP (LD; 4/10 mg/kg), and high dose MP (HD; 30/60 mg/kg). Following 3 months of treatment, half of the rats in each group were euthanized, and the remaining rats received only water throughout a 1-month-long abstinence phase. In vitro autoradiography using [3H] PK 11195 was performed to measure microglial activation. HD MP rats showed increased [3H] PK 11195 binding compared to control rats in several cerebral cortical areas: primary somatosensory cortex including jaw (68.6%), upper lip (80.1%), barrel field (88.9%), and trunk (78%) regions, forelimb sensorimotor area (87.3%), secondary somatosensory cortex (72.5%), motor cortices 1 (73.2%) and 2 (69.3%), insular cortex (59.9%); as well as subcortical regions including the thalamus (62.9%), globus pallidus (79.4%) and substantia nigra (22.7%). Additionally, HD MP rats showed greater binding compared to LD MP rats in the hippocampus (60.6%), thalamus (59.6%), substantia nigra (38.5%), and motor 2 cortex (55.3%). Following abstinence, HD MP rats showed no significant differences compared to water controls; however, LD MP rats showed increased binding in pre-limbic cortex (78.1%) and ventromedial caudate putamen (113.8%). These findings indicate that chronic MP results in widespread microglial activation immediately after treatment and following the cessation of treatment in some brain regions.

Keywords: Methylphenidate, Ritalin, Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Autoradiography, Microglia, Inflammation

Introduction

Methylphenidate (MP) is one of the most frequently prescribed psychostimulant medications for treating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Greenhill et al. 2002a, b). ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder affecting approximately 11% of school aged children, representing a 41% increased prevalence rate over the past decade (Visser et al. 2014). Additionally, studies on illicit use of MP show that up to 30% of college students surveyed report using MP for cognitive enhancement, weight loss, or its euphoric effects (Bogle and Smith 2009;Lakhan and Kirchgessner 2012;Fallah et al. 2018). The increasing use and abuse of MP causes concern over its long-term effects, especially since MP is most often used during critical periods of neurodevelopment. Previously, we found that chronic MP, provided at doses that mimic the pharmacokinetic profile of treated patients, results in a myriad of effects on physiology (including skeletal development) (Komatsu et al. 2012; Uddin et al. 2018; Robison et al. 2017b; Thanos et al. 2015), behavior (Robison et al. 2017b;Thanos et al. 2015), and neurochemistry (Robison et al. 2017a) in normal rats, with some effects persisting beyond the end of treatment. There is a concerning gap in knowledge, however, as to whether chronic MP treatment could result in significant brain inflammation, as has been shown following chronic administration of related psychostimulants (Cadet et al. 2005; Thanos et al. 2016a).

MP’s mechanism of action is partially mediated by its ability to block dopamine (DA) and norepinephrine (NE) transporters and increase extracellular DA and NE (Zhang et al. 2012;Volkow et al. 2002). Clinical results have shown increases in extracellular DA in the prefrontal cortex and striatum following MP administration (Zhang et al. 2012;Volkow et al. 2001). In rats, chronic MP has been shown to alter binding levels of the dopamine transporter and receptors in several regions of the basal ganglia, while a prolonged abstinence period reverses these effects (Caprioli et al. 2015; Robison et al. 2017a). Additionally, it has been shown that MP treatment results in changes in catecholamine systems within the medial prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, striatum, and hypothalamus (Gray et al. 2007). Due to an increase in cytokines and chemokines, excess dopamine has been shown to induce an inflammatory response in the brain, which could lead to an induction of microgliosis (Jang et al. 2012). Therefore, one possible consequence of MP treatment that has not been fully explored is its ability to trigger inflammatory and neurodegenerative processes, as has been shown to result from chronic administration of related psychostimulants (Gonçalves et al. 2010;Thanos et al. 2016a;Cubells et al. 1994; Cadet et al. 2005).

Studies have confirmed that MP reduces the expression of neurotrophins (Sadasivan et al. 2012), and induces apoptosis, oxidative damage, and DNA fragmentation in brain cells (Banihabib et al. 2014;Andreazza et al. 2007;Motaghinejad et al. 2016, 2017a, b; Gomes et al. 2008). Acute and chronic MP also increases the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, while chronic MP increases microglial activation in several brain regions including the cortex, hippocampus, and basal ganglia (Sadasivan et al. 2012;Motaghinejad et al. 2016, 2017b). Chronic administration of clinically relevant doses of MP change cell density and morphology in the dentate gyrus and CA1 of the hippocampus (Motaghinejad et al. 2016) and causes a 20% reduction in dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) (Sadasivan et al. 2012). Additionally, MP treatment sensitizes SNpc neurons to the parkinsonian agent 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), as measured by increased cell death, and enhanced the number of activated microglia following lesioning (Sadasivan et al. 2012). Taken together, the aforementioned results suggest that MP treatment could result in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration across several brain regions; however, there are a few methodological concerns of previous studies. First, all of these studies administered MP intraperitoneally, which differs significantly from oral administration, specifically with respect to time to peak serum concentration, half-life, and rate of elimination (Kuczenski and Segal 2001), as well as absolute magnitude and time course of increases in extracellular DA (Kuczenski and Segal 2001; Gerasimov et al. 2000). Additionally, it is of interest to determine whether the detrimental effects of MP persist beyond the cessation of treatment, as many children taking MP discontinue treatment in later adulthood.

The current study employs a previously established oral dosing paradigm to deliver MP to adolescent rats at two clinically relevant doses (4/10 mg/kg and 30/60 mg/kg) to reproduce the pharmacokinetic profile observed in treated humans (Thanos et al. 2015). The goal of this study is to assess the effects of chronic MP (3 months of treatment) on neuroinflammation in rats, as measured by microglial acti-vation throughout the whole brain, as well as the possible impact of cessation of treatment (following a 1 month drug abstinence period).

Methods and materials

Animals

Adolescent 2-week-old male Sprague Dawley rats (Taconic, Hudson, New York, USA) were individually housed in a controlled room (22 ± 2 °C and 40–60% humidity) with a 12-h reverse light–dark cycle (lights off 0800 h). All rats were allowed 1 week of habituation before starting on the MP drinking paradigm. Food was provided ad libitum throughout the entire experiment. All works were conducted in conformity with the National Academy of Sciences Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academy of Sciences NRC, 1996) and approved by the University at Buffalo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Drugs

Methylphenidate hydrochloride (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in distilled water to produce several doses (as previously described and shown below) of 4, 10,30, and 60 mg/kg solutions. Individual rats’ drinking bottles were made fresh daily based on body weight and the average of their last 3 days’ fluid intake to achieve desired dosages.

Drug paradigm

Rats were split into three groups, receiving water (control), low dose (LD, 4 mg followed by 10 mg) MP, or high dose (HD 30 mg followed by 60 mg) MP treatment (n = 15–16 for all groups). During the treatment period, rats had access to fluids during their dark cycle for 8 h per day. During the first hour of access (09:00 h–10:00 h), 4 mg/kg MP (LD MP) or 30 mg/kg (HD MP) drinking solutions were provided, following by drinking solutions at concentrations of 10 mg/kg (LD MP) or 60 mg/kg (HD MP) for the remaining 7 h (10:00 h–17:00 h). This treatment was based on a previously established dual-bottle 8-h limited access drinking paradigm, which results in a pharmacokinetic profile similar to that observed in patients treated with MP (peaking at ~ 8–10 ng/mL for the LD MP group and ~ 25 ng/mL for the HD MP group) along with similar liquid intakes among the treatment groups (Thanos et al. 2015). Following a 3-month treatment period, half of the rats in each group were euthanized and their brains were extracted for analysis. The remaining half of the animals went through a 1 month abstinence period, during which all rats received only water for the 8-h limited access drinking period while continuing to have access to food ad libitum.

Procedures

[3H] PK 11195 autoradiography

24 h following the respective treatment or abstinence period, rats were anesthetized using isoflurane (~ 3.0%). Brains were quickly removed, flash-frozen in 2-methylbutane, and stored at − 80 °C until use (n = 7–8/group). Cryostat sections (14 μm thick) were cut, mounted on slides, and stored tightly sealed at − 80 °C in the presence of desiccant, until the day of the binding experiment. [3H]PK 11195 binding was carried out according to a previously established protocol (Thanos et al. 2016b). Sections were pre-incubated for 15 min in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature. Sections were then incubated in 50mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.4) with the addition of 0.8nM[3H] PK 11195 (85.7 Ci/mmol, PerkinElmer Inc.) for 30 min at room temperature. Non-specific binding was determined on consecutive sections in the presence of excess 20 μM unlabeled PK 11195. After incubation, sections were washed twice for 6 min in ice-cold 50 mM Tris HCl buffer (pH 7.4) and then dipped in ice-cold distilled water.

After binding, all sections were dried under a stream of cool air and exposed onto Kodak BioMax MR Film for4 weeks, alongside calibrated tritium standards (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, St. Louis, MO). Following exposure, the films were developed in Kodax D-19 developer, dried and scanned as TIFF images at 1200 dpi, under uniform conditions. All regions of interest were quantified using the calibrated standard curves with Image J software (NIH). Regions of interest (ROI) selected for analysis include major areas of the cerebral cortex: prelimbic/infralimbic, cingulate, retrosplenial, insular, piriform, ectorhinal, perirhinal, lateral entorhinal, motor (M1 and M2), primary (jaw, upper lip, barrel field, trunk) and secondary somatosensory (S2), sensorimotor (hindlimb, forelimb), auditory, and visual. Subcortical areas selected for analysis include: nucleus accumbens, amygdala, striatum [split into dorsolateral (DL), dorsomedial (DM), ventrolateral (VL), and ventromedial (VM) quadrants], globus pallidus, hippocampus, hypothalamus, thalamus, and substantia nigra. See Fig. 1 for a map of ROIs drawn.

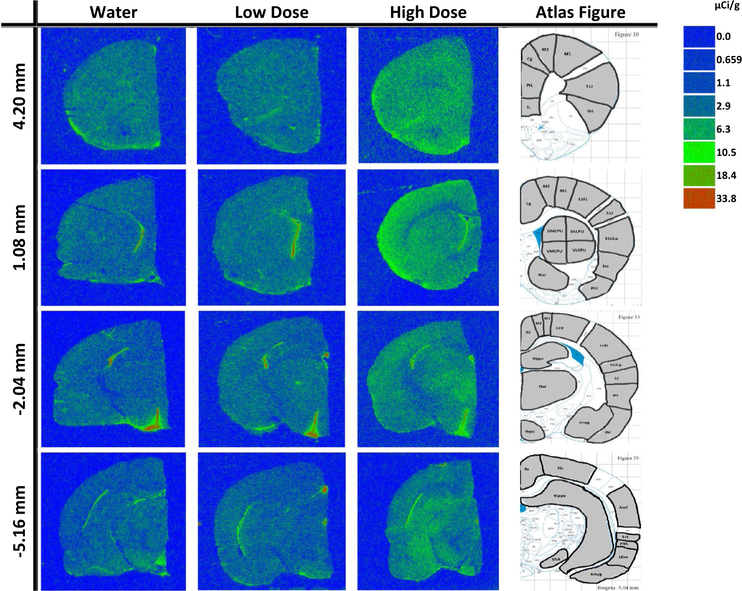

Fig. 1.

Autoradiographic coronal brain images of [3H] PK 11195 binding following 3 months of treatment between water (control), low dose methylphenidate (MP), and high dose MP at the following bregma coordinates: + 4.20, + 1.08, − 2.04, and− 5.16 mm, along with the corresponding regions of interest examined drawn on reference brain atlas images as adapted from Paxinos and Watson rat brain atlas

Statistics

Specific binding for each ROI was analyzed with one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc comparisons when appropriate. All statistical tests were run using SigmaPlot 11.0 software (Systat software Inc., San Jose, CA), with statistical significance set at α = 0.05.

Results

[3H] PK 11195 binding following 3 months of MP treatment

[3H] PK 11195 specific binding following 3 months of MP treatment was analyzed for each ROI with one-way ANOVA, with treatment as factor (Water, LD, HD) (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5). A significant effect of treatment was observed for the insular cortex [F(2,20) = 4.488; p < 0.05]; motor 1 cortex (M1) [F(2,20) = 5.899; p < 0.05]; motor 2 cortex (M2) [F(2,20) = 5.565; p < 0.05]; jaw somatosensory cortex [F(2,20) = 5.068; p < 0.05]; forelimb sensorimotor cortex [F(2,20) = 5.218; p < 0.05]; upper lip somatosensory cortex [F(2,20) = 5.435; p < 0.05]; whisker somatosensory cortex (barrel field) [F(2,20) = 5.032; p < 0.05]; trunk somatosensory cortex [F(2,19) = 3.974; p < 0.05]; secondary somatosensory cortex (S2) [F(2,20) = 4.347; p < 0.05];globus pallidus [F(2,19) = 4.004; p < 0.05]; hippocampus [F(2,20) = 4.445; p < 0.05]; thalamus [F(2,20) = 5.643; p < 0.05], and substantia nigra [F(2,20) = 5.298; p < 0.05].

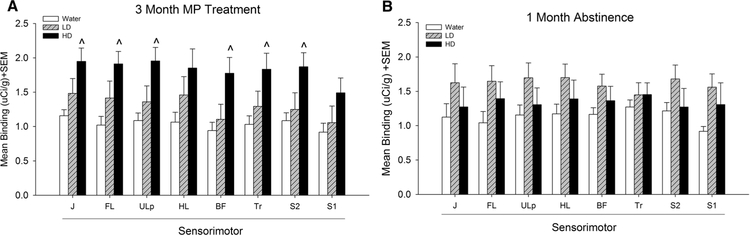

Fig. 2.

Mean [3H] PK 11195 specific binding in somatosensory cortex of control (water), low dose (LD) methylphenidate (MP), and high dose (HD) MP treatment groups following 3 months of treatment (a) or a 1 month abstinence period following 3 months of MP treatment (b). J Jaw, FL forelimb, Ulp upper lip, HL hindlimb, BF barrel field, TR trunk region, S2 secondary somatosensory. ^p < 0.05 compared to water group

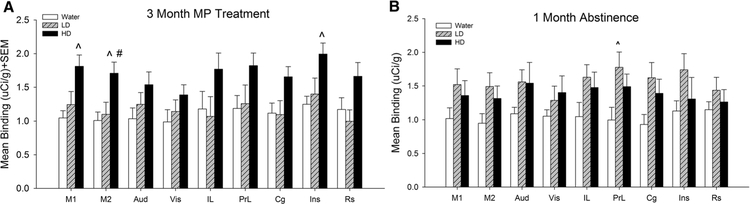

Fig. 3.

Mean [3H] PK 11195 specific binding in cortical regions of control (water), low dose (LD) methylphenidate (MP), and high dose (HD) MP treatment groups following 3 months of treatment (a) or a 1 month abstinence period following 3 months of MP treatment (b). IL Infralimbic, PrL prelimbic, Cg cingulate, Ins insular, M1 primary motor, M2 secondary motor, Aud auditory, Vis visual, Rs retrosplenial. ^p < 0.05 compared to water group; #p < 0.05 compared to LD group

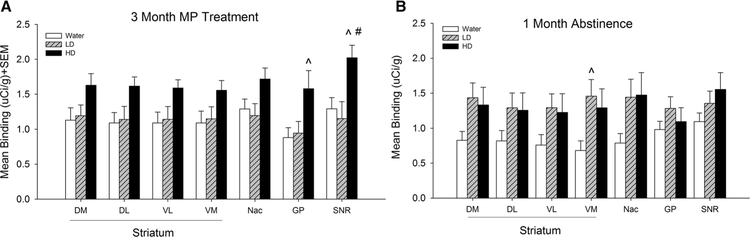

Fig. 4.

Mean [3H] PK 11195 specific binding in subregions of the basal ganglia in control (water), low dose (LD) methylphenidate (MP), and high dose (HD) MP treatment groups following 3 months of treatment (a) or a 1 month abstinence period following 3 months of MP treatment (b). DM Dorsomedial, DL dorsolateral, VM ventromedial, VL ventrolateral, Nac nucleus accumbens, GP globus pallidus, SNR substania nigra. ^p < 0.05 compared to water group; #p < 0.05 compared to LD group

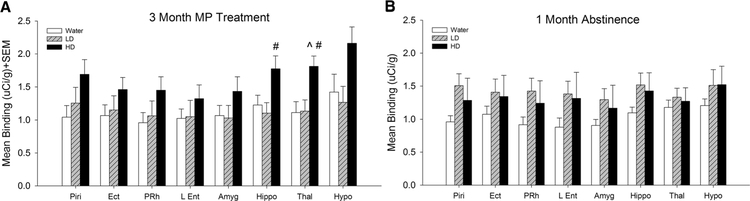

Fig. 5.

Mean [3H] PK 11195 binding in control (water), low dose (LD) methylphenidate (MP), and high dose (HD) MP treatment groups following 3 months of treatment (a) or a 1 month abstinence period following 3 months of MP treatment (b). Piri Piriform cortex, Ect ectorhinal cortex, PRh perirhinal cortex, L Ent lateral entorhinal cortex, Amyg amygdala, Hippo hippocampus, Thal thalamus, Hypo hypothalamus. ^p < 0.05 compared to water group; #p < 0.05 com-pared to LD group

Tukey’s post hoc tests found that HD MP treated rats showed significantly greater [3H] PK 11195 binding compared to water treated rats in the insular cortex, M1, M2, forelimb sensorimotor, jaw, upper lip, barrel field and trunk S1 areas, S2, globus pallidus, thalamus, and substantia nigra (p < 0.05 for all). Additionally, HD MP treated rats showed increased [3H] PK 11195 binding compared to LD treated rats in the M2, hippocampus, thalamus, and substantia nigra (p < 0.05 for all).

[3H] PK 11195 binding following 1 month abstinence from MP

[3H] PK 11195 specific binding following 3 months of MP treatment and 1 month abstinence was analyzed for each ROI with one-way ANOVA across treatment (Water, LD, HD) (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5), A significant effect of treatment was observed in the prelimbic cortex [F(2,18) = 4.044; p < 0.05] and ventromedial striatum [F(2,18) = 3.975; p < 0.05]. Tukey’s post-hoc test found that LD treated rats showed increased [3H] PK 11195 binding compared to water treated rats in these two regions (p < 0.05 for both).

Discussion

Here, we show that chronic daily treatment with a clinically comparable high dose of MP for 3 months can cause increases in microglial activation in multiple regions throughout the brain, (including the primary and secondary somatosensory cortices, primary and secondary motor cortices, insular cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, globus pallidus, and substantia nigra); however, PK 11195 binding levels in HD MP rats were indistinguishable from control rats following a 1 month abstinence period. In contrast,, the LD MP treated rats showed increased PK 11195 binding and microglial activation compared to control rats in prelimbic cortex and ventromedial striatum following the abstinence period. These results suggest that chronic MP treatment could result in neuroinflammation of specific brain regions.

An increase in microglial activation in the somatosensory cortex, motor cortices, basal ganglia, and thalamus could have downstream effects on sensorimotor function. It has been shown that MP is capable of modulating responses of the somatosensory cortex as well as regional blood flow (Drouin et al. 2006, 2007; Lee et al. 2005). Additionally, chronic MP modulates locomotor activity and sensory evoked responses in freely behaving rats (Yang et al. 2006). The insular cortex is involved in a variety of functions including pain perception, speech production, and the processing of social emotions (Nieuwenhuys 2012). The effects of chronic MP on social behavior have also been explored, with variable results in that some found no effect (Robison et al. 2017b), while several others suggest a disruption in social behavior (Vanderschuren et al. 2008;Trezza et al. 2009; Thor and Holloway 1983; Achterberg et al. 2015). Finally, HD MP treated rats displayed increased binding in comparison to LD MP treated rats in the hippocampus, a region associated with shortterm declarative memory and spatial learning and memory (Purves and Fitzpatrick 2001), suggesting that chronic high dose MP use could result in cognitive dysfunction. Previous studies have shown that chronic MP treatment impairs performance on memory tasks such as the Morris water maze (Scherer et al. 2010), object place (LeBlancDuchin and Taukulis 2009), and novel object recognition (Scherer et al. 2010; Heyser et al. 2004;LeBlanc-Duchin and Taukulis 2009); however, others report no effects (Bethancourt et al. 2009; Robison et al. 2017b) or even improvements (Bethancourt et al. 2009) in hippocampaldependent memory, likely due to differences in subjects and/or dosing regimens (routes of administration).

Following an extended 1-month abstinence period, these effects were reversed and there were no longer any differences in [3H] PK 11195 binding between HD MP and water treated rats. Interestingly though, the chronic LD MP treated rats, even after a 1 month abstinence period, showed significant increased microglial activation in the pre-limbic cortex (78.1%), a medial prefrontal area implicated in attention and cognitive flexibility (Dalley et al. 2004), and the ventromedial striatum (113.8%), which is critical for reward-guided and habitual behavior.

[3H] PK 11195 is a peripheral benzodiazepine receptor antagonist (Venneti et al. 2006) and binding has been reported to correspond to activated microglia in brain tissue following various neuronal injuries in rodent models (Stephenson et al. 1995; Pedersen et al. 2006;Raghavendra Rao et al. 2000; Vowinckel et al. 1997). Microglia will become activated in response to CNS damage that stimulates these cells to function as phagocytes (Gehrmann et al. 1995). Activated microglia can be cytotoxic producing potentially cytotoxic molecules such as nitric oxide and proinflammatory cytokines (Nakajima and Kohsaka 2001). In addition to their phagocytic role, microglia also have a protective role for the brain promoting neurogenesis (Butovsky et al. 2006) and removing toxic glutamate levels (Persson et al. 2005). The present findings can be compared to studies on the neurochemical effects of other psychostimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine which both increase extracellular dopamine levels (Volkow et al. 1997; Sulzer et al. 2005). Excess dopamine could be toxic, producing both post and pre-synaptic damage to structures within the brain (Filloux and Townsend 1993). An increase in cytokines and chemokines characterize an inflammatory response in the brain, which has been seen following an increase in free dopamine (Jang et al. 2012), and which could lead to an induction of microgliosis. Stimulant drugs such as methamphetamine have been proven to induce microglial activation after treatment (Thomas et al. 2004; Thanos et al. 2016a), as well as increase other markers of inflammation and neurodegeneration processes (Gonçalves et al. 2010;Thanos et al. 2016a;Cubells et al. 1994; Cadet et al. 2005), while chronic MP treatment in normal animals has reported to lead to structural changes such as decreasing the volume of posterior white matter tracts (Delis et al. 2017).

Some aspects of the study, aside from MP treatment, may have influenced the results of the binding assay. Rats in this study were single housed to accurately measure fluid and food consumption throughout the entirety of the experiment. Single housing is understood to be a “deprived” environment, which may influence the results since animals in socially isolated environments have been shown to be more sensitive to psychostimulants (Howes et al. 2000).

Increasing rates of non-prescription MP use among healthy individuals have been reported (Swanson and Volkow 2008), especially for academic improvement and euphoric effects (Lakhan and Kirchgessner 2012) and it has been reported for over a decade that stimulant use is widespread in college students (Arria and DuPont 2010). Therefore, it is important to further study the neurodevelopmental effects of chronic MP administration. Moreover, among college students nonmedical use of prescription stimulants was associated with past year illicit drug use, alcohol dependence, and marijuana dependence (Arria et al. 2008). Finally, illegal or prescription use of MP is also sought as a mean of decreasing appetite leading to weight loss based on limited findings in the pediatric population with ADHD (Schwartz et al. 2014). The present study found that chronic MP treatment increased microglial activation in multiple brain regions in rats, including the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, and basal ganglia. While many of these effects were reversible by long-term abstinence, some inflammation appeared (lose dose MP) beyond the cessation of treatment. These findings present grave concerns over the use and abuse of MP due to its ability to trigger inflammatory and possibly neurogenerative processes, particularly during critical periods of childhood through young adulthood while the brain is still developing.

Funding

This research was funded by the New York Research Foundation [Q0942016] and the National Institute of Health [R01HD70888].

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted.

References

- Achterberg EJM, van Kerkhof LWM, Damsteegt R, Trezza V, Vanderschuren LJMJ (2015) Methylphenidate and atomoxetine inhibit social play behavior through prefrontal and subcortical limbic mechanisms in rats. J Neurosci 35(1):161–169. 10.1523/jneurosci.2945-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreazza AC, Frey BN, Valvassori SS, Zanotto C, Gomes KM, Comim CM, Cassini C, Stertz L, Ribeiro LC, Quevedo J, Kapczinski F, Berk M, Gonçalves CA (2007) DNA damage in rats after treatment with methylphenidate. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 31(6):1282–1288. 10.1016/j.pnpbp2007.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arria AM, DuPont RL (2010) Nonmedical prescription stimulant use among college students: why we need to do something and what we need to do. J Addict Dis 29(4):417–426. 10.1080/10550887.2010.509273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arria AM, Caldeira KM, O’Grady KE, Vincent KB, Johnson EP, Wish ED (2008) Nonmedical use of prescription stimulants among college students: associations with attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder and polydrug use. Pharmacotherapy 28(2):156–169. 10.1592/phco.28.2.156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banihabib N, Haghi M, Zare S, Farrokhi F (2014) The effect of oral administration of methylphenidate on hippocampal tissue in adult male rats. Neurosurg Q 26(4):315–318(4). 10.1097/WNQ.0000000000000190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bethancourt JA, Camarena ZZ, Britton GB (2009) Exposure to oral methylphenidate from adolescence through young adulthood produces transient effects on hippocampal-sensitive memory in rats. Behav Brain Res 202(1):50–57. 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogle KE, Smith BH (2009) Illicit methylphenidate use: a review of prevalence, availability, pharmacology, and consequences. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2(2):157–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butovsky O, Ziv Y, Schwartz A, Landa G, Talpalar AE, Pluchino S, Martino G, Schwartz M (2006) Microglia activated by IL-4 or IFN-gamma differentially induce neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis from adult stem/progenitor cells. Molecular Cellular Neu-rosci 31(1):149–160. 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet JL, Jayanthi S, Deng X (2005) Methamphetamine-induced neuronal apoptosis involves the activation of multiple death pathways. Rev Neurotox Res 8(3–4):199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprioli D, Jupp B, Hong YT, Sawiak SJ, Ferrari V, Wharton L, Williamson DJ, McNabb C, Berry D, Aigbirhio FI, Robbins TW, Fryer TD, Dalley JW (2015) Dissociable rate-dependent effects of oral methylphenidate on impulsivity and D2/3 receptor availability in the striatum. J Neurosci 35(9):3747–3755. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3890-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubells JF, Rayport S, Rajendran G, Sulzer D (1994) Methamphetamine neurotoxicity involves vacuolation of endocytic organelles and dopamine-dependent intracellular oxidative stress. J Neurosci 14(4):2260–2271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Cardinal RN, Robbins TW (2004) Prefrontal executive and cognitive functions in rodents:neural and neurochemical substrates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 28(7):771–784. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis F, Weber A, Thanos PK (2017) Chronic oral methylphenidate intake affects white matter morphology and NMDA receptor density in normal rats. In: 27th meeting of the Hellenic Society for Neuroscience, Athens [Google Scholar]

- Drouin C, Page M, Waterhouse B (2006) Methylphenidate enhances noradrenergic transmission and suppresses midand long-latency sensory responses in the primary somatosensory cortex of awake rats. J Neurophysiol 96(2):622–632. 10.1152/jn.01310.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouin C, Wang D, Waterhouse BD (2007) Neurophysiological actions of methylphenidate in the primary somatosensory cortex. Synapse 61(12):985–990. 10.1002/syn.20454 doi [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallah G, Moudi S, Hamidia A, Bijani A (2018) Stimulant use in medical students and residents requires more careful attention. Casp J Intern Med 9(1):87–91. 10.22088/cjim.9.1.87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filloux F, Townsend JJ (1993) Preand postsynaptic neurotoxic effects of dopamine demonstrated by intrastriatal injection. Exp Neurol 119(1):79–88. 10.1006/exnr.1993.1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrmann J, Matsumoto Y,Kreutzberg GW (1995) Microglia: intrinsic immune effector cell of the brain. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 20(3):269–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimov MR, Franceschi M, Volkow ND, Gifford A, Gatley SJ, Marsteller D, Molina PE, Dewey SL (2000) Comparison between intraperitoneal and oral methylphenidate administration: a microdialysis and locomotor activity study. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 295(1):51–57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes KM, Petronilho FC, Mantovani M, Garbelotto T, Boeck CR, Dal-Pizzol F, Quevedo J (2008) Antioxidant enzyme activities following acute or chronic methylphenidate treatment in young rats. Neurochem Res 33(6):1024–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves J, Baptista S, Martins T, Milhazes N, Borges F, Ribeiro Carlos F, Malva João O, Silva Ana P (2010) Methamphetamineinduced neuroinflammation and neuronal dysfunction in the mice hippocampus: preventive effect of indomethacin. Eur J Neurosci 31(2):315–326. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07059.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JD, Punsoni M, Tabori NE, Melton JT, Fanslow V, Ward MJ, Zupan B, Menzer D, Rice J, Drake CT, Romeo RD, Brake WG, Torres-Reveron A, Milner TA (2007) Methylphenidate administration to juvenile rats alters brain areas involved in cognition, motivated behaviors, appetite, and stress. J Neurosci 27(27):7196–7207. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0109-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhill L, Beyer DH, Finkleson J, Shaffer D, Biederman J, Conners CK, Gillberg C, Huss M, Jensen P, Kennedy JL, Klein R, Rapoport J, Sagvolden T, Spencer T, Swanson JM, Volkow N (2002a) Guidelines and algorithms for the use of methylphenidate in chil-dren with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J AttenDisord 6(Suppl 1):S89–S100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhill LL, Findling RL, Swanson JM, Group AS (2002b) A doubleblind, placebo-controlled study of modified-release methylphenidate in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 109(3):E39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyser CJ, Pelletier M, Ferris JS (2004) The effects of methylphenidate on novel object exploration in weanling and periadolescent rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1021(1):465–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes SR, Dalley JW, Morrison CH, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ (2000) Leftward shift in the acquisition of cocaine self-administration in isolation-reared rats: relationship to extracellular levels of dopamine, serotonin and glutamate in the nucleus accumbens and amygdala-striatal FOS expression. Psychopharmacology 151(1):55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang H, Boltz D, McClaren J, Pani AK, Smeyne M, Korff A, Webster R, Smeyne RJ (2012) Inflammatory effects of highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus infection in the CNS of mice. J Neurosci 32(5):1545–1559. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5123-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu DE, Thanos PK, Mary MN, Janda HA, John CM, Robison L, Ananth M, Swanson JM, Volkow ND, Hadjiargyrou M (2012) Chronic exposure to methylphenidate impairs appendicular bone quality in young rats. Bone 50(6):1214–1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R, Segal DS (2001) Locomotor effects of acute and repeated threshold doses of amphetamine and methylphenidate: relative roles of dopamine and norepinephrine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 296(3):876–883 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhan SE, Kirchgessner A (2012) Prescription stimulants in individuals with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: misuse, cognitive impact, and adverse effects. Brain Behav 2(5):661–677. 10.1002/brb3.78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc-Duchin D, Taukulis HK (2009) Chronic oral methylphenidate induces post-treatment impairment in recognition and spatial memory in adult rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem 91(3):218–225. 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Kim BN, Kang E, Lee DS, Kim YK, Chung JK, Lee MC, Cho SC (2005) Regional cerebral blood flow in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: comparison before and after methylphenidate treatment. Hum Brain Mapp 24(3):157–164. 10.1002/hbm.20067 doi [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motaghinejad M, Motevalian M, Shabab B (2016) Effects of chronic treatment with methylphenidate on oxidative stress and inflammation in hippocampus of adult rats. Neurosci Lett 619:106–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motaghinejad M, Motevalian M, Abdollahi M, Heidari M, Madjd Z (2017a) Topiramate confers neuroprotection against methylphenidate-induced neurodegeneration in dentate gyrus and CA1 regions of Hippocampus via CREB/BDNF pathway in rats. Neurotox Res 31(3):373–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motaghinejad M, Motevalian M, Shabab B, Fatima S (2017b) Effects of acute doses of methylphenidate on inflammation and oxidative stress in isolated hippocampus and cerebral cortex of adult rats. J Neural Transm 124(1):121–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K, Kohsaka S (2001) Microglia: activation and their significance in the central nervous system. J Biochem 130(2):169–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuys R (2012) The insular cortex: a review. Prog Brain Res 195:123–163. 10.1016/b978-0-444-53860-4.00007-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen MD, Minuzzi L, Wirenfeldt M, Meldgaard M, Slidsborg C, Cumming P, Finsen B (2006) Up-regulation of PK11195 binding in areas of axonal degeneration coincides with early microglial activation in mouse brain. Eur J Neurosci 24(4):991–1000. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04975.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson M, Brantefjord M, Hansson E, Ronnback L (2005) Lipopolysaccharide increases microglial GLT-1 expression and glutamate uptake capacity in vitro by a mechanism dependent on TNFalpha. Glia 51(2):111–120. 10.1002/glia.20191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves A, Fitzpatrick D (2001) Neuroscience, 2nd edn. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra Rao VL, Dogan A, Bowen KK, Dempsey RJ (2000) Traumatic brain injury leads to increased expression of peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptors, neuronal death, and activation of astrocytes and microglia in rat thalamus. Exp Neurol 161(1):102–114. 10.1006/exnr.1999.7269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robison LS, Ananth M, Hadjiargyrou M, Komatsu DE, Thanos PK (2017a) Chronic oral methylphenidate treatment reversibly increases striatal dopamine transporter and dopamine type 1 receptor binding in rats. J Neural Transm 124(5):655–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robison LS, Michaelos M, Gandhi J, Fricke D, Miao E, Lam C-Y, Mauceri A, Vitale M, Lee J, Paeng S (2017b) Sex differences in the physiological and behavioral effects of chronic oral Methylphenidate treatment in rats. Front Behav Neurosci 11:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadasivan S, Pond BB, Pani AK, Qu C, Jiao Y, Smeyne RJ (2012) Methylphenidate exposure induces dopamine neuron loss and activation of microglia in the basal ganglia of mice. PLoS One 7(3):e33693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer EBS, da Cunha MJ, Matté C, Schmitz F, Netto CA, Wyse ATS (2010) Methylphenidate affects memory, brain-derived neurotrophic factor immunocontent and brain acetylcholinesterase activity in the rat. Neurobiol Learn Mem 94(2):247–253. 10.1016/j.nlm.2010.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz BS, Bailey-Davis L, Bandeen-Roche K, Pollak J, Hirsch AG, Nau C, Liu AY, Glass TA (2014) Attention deficit disorder, stimulant use, and childhood body mass index trajectory. Pediatrics 133(4):668–676. 10.1542/peds.2013-3427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson DT, Schober DA, Smalstig EB, Mincy RE, Gehlert DR, Clemens JA (1995) Peripheral benzodiazepine receptors are colocalized with activated microglia following transient global forebrain ischemia in the rat. J Neurosci 15(7 Pt 2):5263–5274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Sonders MS, Poulsen NW, Galli A (2005) Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by amphetamines: a review. Prog Neurobiol 75(6):406–433. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JM, Volkow ND (2008) Increasing use of stimulants warns of potential abuse. Nature 453(7195):586–586. 10.1038/453586a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos PK, Robison LS, Steier J, Hwang YF, Cooper T, Swanson JM, Komatsu DE, Hadjiargyrou M, Volkow ND (2015) A pharmacokinetic model of oral methylphenidate in the rat and effects on behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 131:143–153. 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos PK, Kim R, Delis F, Ananth M, Chachati G, Rocco MJ, Masad I, Muniz JA, Grant SC, Gold MS (2016a) Chronic methamphetamine effects on brain structure and function in rats. PloS One 11(6):e0155457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos PK, Kim R, Delis F, Ananth M, Chachati G, Rocco MJ, Masad I, Muniz JA, Grant SC, Gold MS, Cadet JL, Volkow ND (2016b) Chronic methamphetamine effects on brain structure and function in rats. PloS One 11(6):e0155457 10.1371/journal.pone.0155457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DM, Walker PD, Benjamins JA, Geddes TJ, Kuhn DM (2004) Methamphetamine neurotoxicity in dopamine nerve endings of the striatum is associated with microglial activation. J Pharmacol Exp Therapeutics 311(1):17. 10.1124/jpet.104.070961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thor DH, Holloway WR (1983) Play soliciting in juvenile male rats: effects of caffeine, amphetamine and methylphenidate. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 19(4):725–727. 10.1016/00913057(83)90352-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V, Damsteegt R, Vanderschuren LJMJ (2009) Conditioned place preference induced by social play behavior: parametrics, extinction, reinstatement and disruption by methylphenidate. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 19(9):659–669. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2009.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin SM, Robison LS, Fricke D, Chernoff E, Hadjiargyrou M, Thanos PK, Komatsu DE (2018) Methylphenidate regulation of osteoclasts in a dose-and sex-dependent manner adversely affects skeletal mechanical integrity. Sci Rep 8(1):1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJMJ, Trezza V, Griffioen-Roose S, Schiepers OJG, Van Leeuwen N, De Vries TJ, Schoffelmeer ANM (2008) Methylphenidate disrupts social play behavior in adolescent rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 33:2946 10.1038/npp.2008.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venneti S, Lopresti BJ, Wiley CA (2006) The peripheral benzodiazepine receptor in microglia: from pathology to imaging. Prog Neurobiol 80(6):308–322. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Holbrook JR, Kogan MD, Ghandour RM, Perou R, Blumberg SJ (2014) Trends in the parentreport of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003–2011. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 53(1):34–46 e32. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fischman MW, Foltin RW, Fowler JS, Abumrad NN, Vitkun S, Logan J, Gatley SJ, Pappas N, Hitzemann R, Shea CE (1997) Relationship between subjective effects of cocaine and dopamine transporter occupancy. Nature 386(6627):827–830. 10.1038/386827a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang G-J, Fowler JS, Logan J, Gerasimov M, Maynard L, Ding Y-S, Gatley SJ, Gifford A, Franceschi D (2001) Therapeutic doses of oral methylphenidate significantly increase extracellular dopamine in the human brain. J Neurosci 21(2):RC121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang G, Ding Y, Gatley SJ (2002) Mechanism of action of methylphenidate: insights from PET imaging studies. J Attent Disord 6(Suppl 1):S31–S43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vowinckel E, Reutens D, Becher B, Verge G, Evans A, Owens T, Antel JP (1997) PK11195 binding to the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor as a marker of microglia activation in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurosci Res 50 (2):345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang PB, Swann AC, Dafny N (2006) Chronic methylphenidate modulates locomotor activity and sensory evoked responses in the VTA and NAc of freely behaving rats. Neuropharmacology 51(3):546–556. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CL, Feng ZJ, Liu Y, Ji XH, Peng JY, Zhang XH, Zhen XC, Li BM (2012) Methylphenidate enhances NMDA-receptor response in medial prefrontal cortex via sigma-1 receptor: a novel mechanism for methylphenidate action. PloS One 7(12):e51910 10.1371/journal.pone.0051910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]