Abstract

Research on licensed nurses in assisted living and residential care communities (RCCs) is sparse compared to that on licensed nurses in nursing homes. RCCs are state-regulated; thus, staffing requirements vary considerably. The current study analyzed variation in characteristics of licensed nurses by state-specific requirements for licensed nurses in RCCs. A significantly higher percentage of RCCs with one or more RNs (68.87%) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) or licensed vocational nurses (LVNs) (56.85%) were found among states with licensed nurse requirements compared to states with no such requirements (37.35% and 29.08%, respectively; p < 0.05). LPN/LVN hours were higher among RCCs in states with licensed nurse requirements compared to RCCs in states with no such requirements (17 minutes and 8 minutes, respectively; p < 0.05). The findings provide the first evidence of variation in characteristics of licensed nurses by state-specific requirements for licensed nurses.

Residential care communities (RCCs), including assisted living, continue to grow in scope and importance as a major alternative to institutional types of long-term care (LTC) (i.e., nursing facilities) for older adults and younger adults with disabilities (Han, Trinkoff, Storr, Lerner, & Yang, 2017; Harris-Kojetin et al., 2016). A combination of public policies and private sector developments spurred this shift, including the Olmstead Decision and availability of Medicaid waivers, which allowed states to use LTC funds to pay for residential community-based services (Friedman, 2017). In addition, the shift from nursing facilities to RCCs was supported by a private sector response to consumer demand from older adults who needed personal care assistance and monitoring and wanted an alternative to nursing home care (Lord, Davlyatov, Thomas, Hyer, & Weech-Maldonado, 2018; Silver, Grabowski, Gozalo, Dosa, & Th omas, 2018). Over time, RCCs have come to serve an increasingly disabled population with multiple chronic conditions and a diverse set of health care needs (Stearns et al., 2007).

There are two primary types of care-related staffing in RCCs—licensed nurses, such as RNs and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) or licensed vocational nurses (LVNs), and unlicensed nurse aides. In terms of skill level, RNs receive approximately 2 to 6 years of education and training, followed by LPNs/LVNs who receive approximately 1 year of training. Both types of nurse staffing must be licensed to practice (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017a,b). Licensed nurse responsibilities in RCCs include coordination and oversight for nursing and medication services (Carder, O’Keeffe, O’Keeffe, White, & Wiener, 2016). In contrast, nurse aides are not licensed, and include a wide range of staff types, including nurse aides who are certified by the state after completing a mandated training course, and personal care aides who lack any certification.

Common staffing measures for LTC and other types of health care facilities include staffing hours per resident per day (HPRD) and skill mix. Staffing HPRD is operationalized in the literature as the ratio of the average number of staffing HPRD in a RCC, and is considered to be an important indicator of LTC quality (Backhaus, Verbeek, van Rossum, Capezuti, & Hamers, 2014; Castle & Anderson, 2011; Harrington, Schnelle, McGregor, & Simmons, 2016; Lee, Blegen, & Harrington, 2014; Park & Stearns, 2009; Zhang & Grabowski, 2004).

Nurse staffing skill mix is the ratio of licensed to unlicensed nurse staffing, or some combination of the various permutations of staffing types, such as licensed nurses to aides or aides to activities staff. Multiple organizational factors may influence staffing skill mix in LTC, such as service availability and resident acuity (Beeber et al., 2014). Nurse staffing skill mix is associated with resident outcomes (e.g., hospitalizations) and quality of care in RCCs and nursing homes (Bowblis, 2011; Kim, Harrington, & Greene, 2009; Stearns et al., 2007; Trinkoff et al., 2013).

The primary function of staffing regulations is to enhance patient safety and quality of care and ensure that the diverse needs of residents are being met (Harrington et al., 2016). RCCs are regulated by states, and state regulations vary, including the mix, scope, and level of nurse staffing required (Carder & O’Keeffe, 2016). Not all states have a requirement for RCC nurse staffing, with some states requiring nurses only if current residents have nursing care needs, and other states requiring full-time nurses (Carder et al., 2016).

The current study draws from a study by Paek, Zhang, Wan, Unruh, and Meemon (2016) by using the resource dependence theory’s construct of environmental complexity to conceptualize how state regulations might impact staffing HPRD and skill mix. This theory posits that an organization’s resources are influenced by the macro operating environment, such as federal and state policy; external funding mechanisms; and organizational characteristics (Yeager et al., 2014). Paek et al. (2016) found that nursing homes in states with stronger licensed nurse and aide minimum staffing standards were more likely to have higher staffing levels for each of the licensed nurse and aide staff types, as measured by HPRD. The study by Paek et al. (2016) is one study of a growing body of nursing home sector literature that explores the relationship between state minimum staffing standards and various measures of nurse staffing hours (Bowblis, 2011; Bowblis & Hyer, 2013; Chen & Grabowski, 2015; Harrington et al., 2016; Lin, 2014; Mueller et al., 2006; Mukamel et al., 2012; Park & Stearns, 2009).

No published literature has examined the relationship between state regulations and RCC staffing levels and skill mix. Previous studies on staffing in the assisted living sector from national surveys used a sample that could not be extrapolated to the state level, or used administrative data sources that focused on a single state exclusively (Hernandez, 2007; Simmons, Coelho, Sandler, Shah, & Schnelle, 2017; Stearns et al., 2007).

The current descriptive study provides the most recent national estimates of the percentage of RCCs that employ or contract one or more RNs and one or more LPNs/LVNs, in addition to describing licensed nurse and aide staffing HPRD and skill mix among RCCs. This study is also the first to examine variation in the percentage of RCCs with one or more licensed nurses, as well as variation in licensed nurse and aide staffing HPRD and skill mix among RCCs by state staffing requirements, by describing and comparing aggregated estimates for RCCs in states with licensed nurse requirements versus RCCs in states with no such requirements to determine whether the differences are statistically significant. Aides were used as a comparator for licensed nurses to determine whether state requirements for licensed nurses had an impact on unlicensed care staff in these settings.

METHOD

Data Sources

National Study of Long-Term Care Providers.

RCC staffing data were obtained from the RCC survey component of the 2014 National Study of Long-Term Care Providers (NSLTCP) (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2016). To be eligible to participate in the study, a facility must be regulated by the state to provide room and board with at least two meals per day; provide around-the-clock on-site supervision and assistance with personal care, such as bathing and dressing, or health-related services, such as medication management; operate four or more licensed, certified, or registered beds; have at least one resident currently living in the RCC at the time of the survey; and serve a predominantly adult population.

Nursing homes were excluded from the sample, along with RCCs that were licensed to exclusively serve residents with severe mental illness or intellectual or developmental disabilities (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2016). Among the sample of 11,618 RCCs drawn from the 2014 RCC sampling frame of 40,583 communities across the United States (National Center for Health Statistics, 2015), 5,035 RCCs completed a survey questionnaire for a weighted response rate of 49.6%. Further information regarding the 2014 NSLTCP RCC survey eligibility criteria, methodology, and data collection is available online (access https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsltcp/nsltcp_questionnaires.htm).

Staffing Variables

The 2014 NSLTCP collected information on the number of full- and part-time employee and contract RNs, LPNs/LVNs, and aides. Aides were defined as certified nursing assistants, nursing assistants, home health aides, home health care aides, personal care aides, personal care assistants, and medication technicians or medication aides. Both employee and contract staff full-time equivalents (FTEs) were combined for each of the staffing measures included in this analysis.

Six nurse staffing outcome variables were derived to assess variation among all RCCs nationally and for each of the two staffing state regulatory subgroups (i.e., 38 states [including the District of Columbia] with licensed nurse staffing requirements and 13 states without). The first two outcome variables were defined as the percentage of RCCs that had one or more RN FTEs and one or more LPNs/LVNs FTEs, respectively. Measures were obtained by dividing the number of RCCs that had one or more RNs by the total number of RCCs and dividing the number of RCCs that had one or more LPNs/LVNs by the total number of RCCs. As the focus of this analysis was on licensed nurse staffing, and because 80% of RCCs had one or more aide employees in 2014 (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2016), a measure of the percentage of RCCs with one or more aides was not included in the analyses.

The third through fifth staffing outcome variables measured HPRD for different staff types. Staffing HPRD was defined as the ratio of the average number of hours providing care per resident each day for RNs, LPNs/LVNs, and aides, respectively. To derive each of these three measures of staffing HPRD, the number of FTEs for each staff type was converted into hours by multiplying each FTE or fraction of a FTE for the staff type at the RCC by 35 hours, then dividing that estimate by 7 days, then dividing that estimate by the number of current residents in the RCC to arrive at HPRD:

Licensed nurse and aide staffing variables were derived from employee and contract FTE staffing. If the derived HPRD was >24, these values were recoded to 24.

Aide staffing HPRD was included in the analysis to determine whether state licensed nurse staffing requirements corresponded to differences in aide HPRD and skill mix—licensed nurse staffing versus aide staffing. Skill mix, the sixth staffing outcome variable, was calculated as the percentage of the total average HPRD worked by RNs and LPNs/LVNs compared to the total average HPRD worked by licensed nurses and aide staff combined, formulated as:

Residential Care and Assisted Living Regulation Variable

State regulatory information for nurse staffing was obtained from a 2014 compendium of RCC regulations and a follow-up report that focused primarily on licensed professional staff (Carder, O’Keeffe, & O’Keeffe, 2015; Carder et al., 2016). Table 1 of the Carder et al. (2016) study was used as the framework for categorizing each state by whether the state: (a) had a requirement for a licensed nurse (RN or LPN/LVN) to be on staff or available, either through employment or as a consultant; or (b) did not have a requirement for licensed nurse staffing.

TABLE 1.

Staffing Characteristics of Residential Care Communities in 2014a

| Variable | % (SE) |

|---|---|

| Distribution of licensed staff across communities |

|

| One or more RNs | 53.73 (0.93) |

| One or more LPNs/LVNs | 43.51 (0.83) |

| Skill mix | |

| Licensed nurse | 17.68 (0.57) |

| Mean Hours (Minutes) (SE) | |

| Staffing HPRD | |

| RN | 0.26 (16) (0.02) |

| LPN/LVN | 0.21 (13) (0.01) |

| Aide | 2.35 (141) (0.06) |

Note. SE = standard error; LPN = licensed practical nurse; LVN = licensed vocational nurse; HPRD = hours per resident per day.

As part of the validation process, the current authors reviewed state-specific regulations from the RCC compendium that focused on staffing. Although the Carder et al. (2016) report included other licensed health care professionals such as physicians and physician’s assistants to define licensed staffing, exclusion of this staff type for the purposes of the current analysis did not change the overall categorization of states.

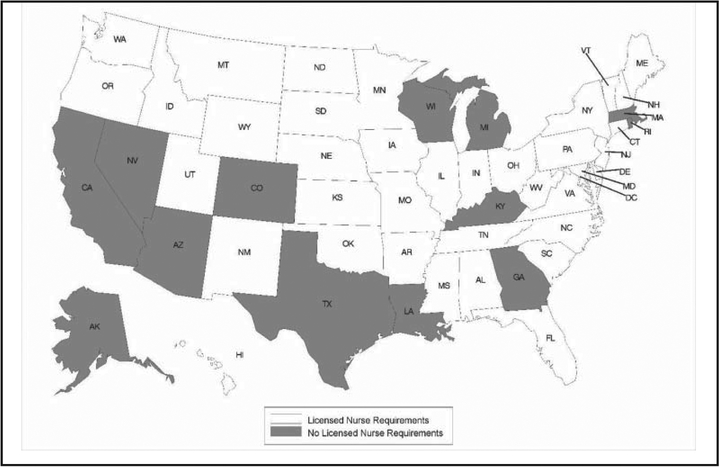

Thirty-eight states, including the District of Columbia, had a requirement for RNs or LPNs/LVNs to be on staff or available, either through employment or as a consultant, whereas 13 states did not. Figure 1 provides the geographic distribution of states by whether the state has a requirement for licensed nurses to be on staff or otherwise available. A weighted 52% of RCCs in the United States in 2014, housing 67% of RCC residents, were in states that had a requirement for a licensed nurse to be on staff or otherwise available.

Figure 1.

States with and without regulatory requirements for licensed nurse staffing in residential care, 2014.

Analysis

The unit of analysis was the RCC. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3/SAS-callable SUDAAN version 11.0.0 statistical packages. RCC staffing characteristics nationally and by regulatory subgroup were described using proportions for categorical variables and means for continuous variables. Tests for statistically significant differences in proportions and means were determined in SAS using chi-square and t tests (p < 0.05), respectively.

The current analysis used the coefficient of variation (CV), which is the standard error of the estimate divided by the estimate multiplied by 100, to test for reliability of estimates for states that were sampled during the 2014 survey. Estimates with a CV of <30% that were based on 60 or more sampled cases were considered reliable and reported in the results.

Final Sample

Of the 5,035 RCCs included in the 2014 RCC survey data file, 381 were identified as adult foster care (AFC) providers and excluded from the analyses. AFC is a type of home- and community-based service that provides personal care assistance to adults who reside in a residential home with a live-in caregiver (Carder et al., 2015; Horsford & Zimmerman, 2016). The current study used the description of each state’s AFC licensure categories, as described in Carder et al. (2015), to link to the state licensure labels available in the 2014 RCC sampling frame to identify AFCs in the survey data file. Of the remaining RCCs, 134 did not provide a response to any of the staffing questions and therefore were excluded from the analyses. The final analytic sample included 4,520 cases.

RESULTS

Percentage of RCCs With One or More RNs and LPNs/LVNs

In 2014, 53.73% and 43.51% of all RCCs in the United States either employed or obtained through contract one or more RNs or one or more LPNs/LVNs, respectively (Table 1). The percentage of RCCs that employed or contracted one or more RNs was significantly higher among states that had a regulatory requirement for licensed nurses to be on staff or available, either through employment or as a consultant, compared to states that did not have such a requirement (68.87% and 37.35%, respectively; p < 0.05) (Table 2). More than one half of all RCCs that had state requirements for licensed nurses had one or more LPNs/LVNs (56.85%), compared to 29.08% of RCCs that did not have state requirements for licensed nurses (p < 0.05).

TABLE 2.

Staffing Characteristics of Residential Care Communities (RCCs) in the United States in 2014, by State Requirements for Licensed Nursesa

| Variable | States Without Licensed Nurse Requirements |

States With Licensed Nurse Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| % (SE) | ||

| Distribution of licensed staff across communities |

||

| One or more RNsb | 37.35 (1.57) | 68.87 (1.05) |

| One or more LPNs/LVNsb | 29.08 (1.32) | 56.85 (1.04) |

| Skill mix | ||

| Licensed nurse | 13.58 (1.01) | 21.46 (0.57) |

| Mean Hours (Minutes) (SE) | ||

| Staffing HPRD | ||

| RN | 0.23 (14) (0.03) | 0.29 (17) (0.02) |

| LPN/LVNb | 0.14 (8) (0.02) | 0.28 (17) (0.01) |

| Aide | 2.32 (139) (0.10) | 2.38 (143) (0.07) |

Note. SE = standard error; LPN = licensed practical nurse; LVN = licensed vocational nurse; HPRD = hours per resident per day.

Differences between RCCs in states without licensed nurse staffing requirements and RCCs in states with licensed nurse requirements are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Staffing HPRD

Staffing HPRD among all RCCs was approximately 0.26 hours (16 minutes) for RNs, 0.21 hours (13 minutes) for LPNs/LVNs, and 2.35 hours (141 minutes) for aides (Table 1). The LPN/LVN staffing HPRD among RCCs in states with a licensed nurse staffing requirement was significantly higher (0.28 hours [17 minutes]) than the LPN/LVN staffing HPRD among RCCs in states without licensed nurse staffing requirements (0.14 hours [8 minutes], p < 0.05) (Table 2). The RN staffing HPRD among RCCs in states with a licensed nurse staffing requirement was not significantly different (0.29 hours [17 minutes]) from the RN staffing HPRD among RCCs in states without licensed nurse staffing requirements (0.23 hours [14 minutes]). The aide staffing HPRD among RCCs in states with a licensed nurse staffing requirement was not significantly different (2.38 hours [143 minutes]) from the aide staffing HPRD among RCCs in states without licensed nurse staffing requirements (2.32 hours [139 minutes]).

Skill Mix

Among all RCCs in 2014, licensed nurse (RN and LPN/LVN) staffing hours constituted 17.68% of all nurse and aide staffing time in RCCs (Table 1). Licensed nurses constituted 21.46% of all nurse and aide staff time among RCCs in states with one or more licensed nurse staffing requirements, which was significantly higher than the percentage of licensed nurse staffing time among RCCs in states with no requirements (13.58%, p < 0.05) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In the current cross-sectional analysis of RCCs in the United States in 2014, researchers found that most RCCs employed or contracted one or more RNs, whereas four of 10 RCCs employed or contracted one or more LPNs/LVNs. Approximately one fifth of all nurse and aide staffing hours were provided by licensed nurses, with aides providing the majority of care in this sector. Overall, a higher percentage of RCCs employed or contracted one or more RNs than LPNs/LVNs, but RNs and LPNs/LVNs had similar staffing HPRD nationally.

Significant differences were found when comparing RCCs in states that had requirements for licensed nurses with RCCs in states that had no requirements regarding the percentage of RCCs with one or more RN and LPN/LVN staffing, LPN/LVN staffing HPRD, and licensed nurse staffing skill mix. The LPN/LVN staffing HPRD for RCCs in states with licensed nurse staffing requirements were double the HPRD in states without such requirements, indicating that RCCs in the former group of states may have preferred to meet the requirement for licensed nurses with less skilled licensed nurses.

As with LPNs/LVNs, RN and aide HPRD were higher in states that had licensed nurse requirements, although these differences were small and not statistically significant. The finding that RN staffing HPRD did not vary much by state requirements for licensed nurse staffing may be due to RNs’ function as coordinators of services rather than direct providers of care to residents. In addition, because LPNs/LVNs have fewer years of education than RNs, they represent a less expensive alternative for RCCs to meet the licensed nurse staffing requirement. In 2016, the median annual salary for RNs in nursing and residential care facilities was $60,950, compared to $45,300 for LPNs/LVNs (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017a,b).

Apart from falling outside the scope of licensed nurse staffing requirements, the lack of differences in aide HPRD among the regulatory groups examined may also be due to the fact that aides comprise the primary source of direct care to residents across all types of facilities regardless of the mix of licensed nurse staff types.

LIMITATIONS

The current findings have several limitations. The bivariate design of this analysis does not control for factors related to the facility, such as the organizational structure and acuity of residents, or additional environmental factors, such as state funding mechanisms and measures of nurse labor market availability, which might be associated with the licensed nurse and aide staffing measures examined in this analysis. The current study was a cross-sectional study; therefore, causal relationships cannot be determined. In states that licensed multiple levels of care, only the most stringent licensed nurse staffing requirement was used in the analysis. Therefore, a particular requirement for licensed nurses may not apply to all facilities in a state with multiple types of RCCs. State requirements for licensed nurses vary considerably in regard to the nature of the requirement, such as for the provision of certain types of services. The current analysis does not consider the variety of ways licensed nurses are regulated. In addition, this study did not account for secondary or tertiary regulatory forces that might influence staffing indirectly, such as provisions for third-party providers, restrictions on the provision of skilled nursing services, and states’ Nurse Practice Act requirements and definitions for licensed nurses. Finally, the NSLTCP surveys do not distinguish between the various roles that licensed nurse staffing may undertake in a facility, such as for the direct provision of care or facility administration.

CONCLUSION

The current study is the first to examine differences in licensed nurse and aide staffing characteristics by state regulations for licensed nurses in the RCC sector. The results indicated that there is variation in the percentage of RCCs that employed or contracted one or more RNs and one or more LPNs/LVNs and skill mix of licensed nurse staffing in assisted living and similar RCCs, as well as LPN/LVN HPRD, between states that had requirements for licensed nurses versus those that did not have these requirements. The results suggest that RCCs in states with regulatory oversight for licensed nurses organize staffing resources to meet these requirements. With the increased shift of residents and federal resources to RCCs and other community-based services, questions remain about how providers are organizing essential resources such as staffing, as well as the impact on resident quality of care and outcomes. It is unknown if these differences would persist after controlling for possible moderating factors related to the operating characteristics of the RCC, the cognitive or functional status of residents, the local long-term care marketplace, workforce wages, other state regulations that impact RCCs (e.g., the Nurse Practice Act), or additional components of the state’s RCC regulations that might indirectly influence the typology of services and users. These findings can help fill current knowledge gaps regarding the relationship between state licensed nurse staffing requirements and the structure and resources of RCCs in the United States.

Acknowledgments

The authors have disclosed no potential conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise. The authors thank Manisha Sengupta, PhD, for her assistance in validating the estimates and standard errors reported in this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Backhaus R, Verbeek H, van Rossum E, Capezuti E, & Hamers JP (2014). Nurse staffing impact on quality of care in nursing homes: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 15, 383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeber AS, Zimmerman S, Reed D, Mitchell CM, Sloane PD, Harris-Wallace B,…Schumacher JG (2014). Licensed nurse staffing and health service availability in residential care and assisted living. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 62, 805–811. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowblis JR (2011). Staffing ratios and quality: An analysis of minimum direct care staffing requirements for nursing homes. Health Services Research, 46, 1495–1516. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01274.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowblis JR, & Hyer K (2013). Nursing home staffing requirements and input substitution: Effects on housekeeping, food service, and activities staff. Health Services Research, 48, 1539–1550. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carder PC, & O’Keeffe J (2016). State regulation of medication administration by unlicensed assistive personnel in residential care and adult day services settings. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 9, 209–222. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20160404-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carder PC, O’Keeffe J, & O’Keeffe C (2015, June 15). Compendium of residential care and assisted living regulations and policy: 2015 edition. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/compendium-residential-care-and-assisted-living-regulations-and-policy-2015-edition

- Carder PC, O’Keeffe J, O’Keeffe C, White E, & Wiener JM (2016). State regulatory provisions for residential care settings: An overview of staffing requirements. Retrieved from https://www.rti.org/rti-press-publication/state-regulatory-provisions-residential-care-settings

- Castle NG, & Anderson RA (2011). Caregiver staffing in nursing homes and their influence on quality of care: Using dynamic panel estimation methods. Medical Care, 49, 545–552. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820fbca9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MM, & Grabowski DC (2015). Intended and unintended consequences of minimum staffing standards for nursing homes. Health economics, 24, 822–839. doi: 10.1002/hec.3063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman C (2017). A national analysis of Medicaid home and community based services waivers for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: FY 2015. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 55, 281–302. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-55.5.281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K, Trinkoff AM, Storr CL, Lerner N, & Yang BK (2017). Variation across U.S. assisted living facilities: Admissions, resident care needs, and staffing. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 49, 24–32. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington C, Schnelle JF, McGregor M, & Simmons SF (2016). The need for higher minimum staffing standards in U.S. nursing homes. Health Services Insights, 9, 13–19. doi: 10.4137/HSI.S38994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Valverde R, Caffrey C, Rome V, & Lendon J (2016). Long-term care providers and services users in the United States: Data from the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers, 2013–2014. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_03/sr03_038.pdf [PubMed]

- Hernandez M (2007). Assisted living and residential care in Oregon: Two decades of state policy, supply, and Medicaid participation trends. The Gerontologist, 47, 118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsford C, & Zimmerman S (2016). Adult foster care homes In Whitbourne SK (Ed.), The encyclopedia of adulthood and aging. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Harrington C, & Greene WH (2009). Registered nurse staffing mix and quality of care in nursing homes: A longitudinal analysis. The Gerontologist, 49, 81–90. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY, Blegen MA, & Harrington C (2014). The effects of RN staffing hours on nursing home quality: A two-stage model. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 51, 409–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H (2014). Revisiting the relationship between nurse staffing and quality of care in nursing homes: An instrumental variables approach. Journal of HealTheconomics, 37, 13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord J, Davlyatov G, Th omas KS, Hyer K, & Weech-Maldonado R (2018). The role of assisted living capacity on nursing home financial performance. Inquiry, 55, 46958018793285. doi: 10.1177/0046958018793285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller C, Arling G, Kane R, Bershadsky J, Holland D, & Joy A (2006). Nursing home staffing standards: Their relationship to nurse staffing levels. The Gerontologist, 46, 74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel DB, Weimer DL, Harrington C, Spector WD, Ladd H, & Li Y (2012). The effect of state regulatory stringency on nursing home quality. Health Services Research, 47, 1791–1813. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01459.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. (2015). 2014 national study of long-term care providers: Survey methodology and documentation. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nsltcp/nsltcp_2014_survey_methodology_and_documentation.pdf

- Paek SC, Zhang NJ, Wan TT, Unruh LY, & Meemon N (2016). The impact of state nursing home staffing standards on nurse staffing levels. Medical Care Research and Review, 73, 41–61. doi: 10.1177/1077558715594733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, & Stearns SC (2009). Effects of state minimum staffing standards on nursing home staffing and quality of care. Health Services Research, 44, 56–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00906.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver BC, Grabowski DC, Gozalo PL, Dosa D, & Th omas KS (2018). Increasing prevalence of assisted living as a substitute for private-pay long-term nursing care. Health Services Research. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons SF, Coelho CS, Sandler A, Shah AS, & Schnelle JF (2017). Managing person-centered dementia care in an assisted living facility: Staffing and time considerations. The Gerontologist, 58, e251–e259. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stearns SC, Park J, Zimmerman S, Gruber-Baldini AL, Konrad TR, & Sloane PD (2007). Determinants and effects of nurse staffing intensity and skill mix in residential care/assisted living settings. The Gerontologist, 47, 662–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkoff AM, Han K, Storr CL, Lerner N, Johantgen M, & Gartrell K (2013). Turnover, staffing, skill mix, and resident outcomes in a national sample of US nursing homes. Journal of Nursing Administration, 43, 630–636. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2017a). Licensed practical and licensed vocational nurses. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/licensed-practical-and-licensed-vocational-nurses. htm

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2017b). Registered nurses. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/registered-nurses.htm

- Yeager VA, Menachemi N, Savage GT, Ginter PM, Sen BP, & Beitsch LM (2014). Using resource dependency theory to measure the environment in health care organizational studies: A systematic review of the literature. Health Care Management Review, 39, 50–65. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3182826624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, & Grabowski DC (2004). Nursing home staffing and quality under the nursing home reform act. The Gerontologist, 44, 13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]