Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a key metabolite in biosynthesis and is increasingly being recognized as an essential gasotransmitter. Owing to its diffusible and reactive nature, H2S can be difficult to quantify, particularly in situ. Although several detection schemes are available, they have drawbacks. In efforts to quantify sulfide release in the cross-linking reaction of the flagellar protein FlgE we developed an enzyme-coupled sulfide detection assay using the Escherichia coli O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase enzyme CysM. Conversion of HS− to L-cysteine via CysM followed by derivatization with the thiol-specific fluorescent dye 7-diethylamino-3-(4-maleimidophenyl)-4-methylcoumarin enables for facile detection and quantification of H2S by fluorescent HPLC. The assay was validated by comparison to the well-established methylene blue sulfide detection assay and the robustness demonstrated by interference assays in the presence of common thiols such as glutathione, 2-mercaptoethanol, dithiothreitol and L-methionine, as well as a range of anions. We then applied the assay to the aforementioned lysinoalanine cross-linking by the Treponema denticola flagellar hook protein FlgE. Overall, unlike previously reported H2S detection methods, the assay provides a biologically compatible platform to accurately and specifically measure hydrogen sulfide in situ, even when it is produced on long time scales.

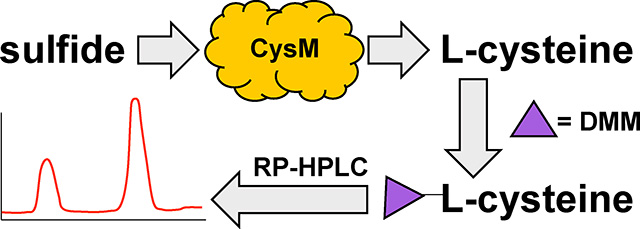

Graphical Abstract

2. Introduction

H2S and its deprotonated forms, HS- and S2−, are key metabolites in the biosynthesis of amino acids, nucleic acids and cofactors. Furthermore, interest in H2S signaling has recently surged after the discovery that H2S belongs to the family of gasotrasmitters essential for maintaining proper homeostasis, along with carbon monoxide (CO) and nitric oxide (NO).1,2 H2S is an endogenous modulator in the central nervous system, and has additional regulatory roles in the cardiovascular, digestive, reproductive, respiratory, and renal systems.2 Sulfate-reducing bacteria of the gut flora are a major source of sulfide and hence the state of the microbiome is a key factor in H2S availability. Interestingly, recent studies have also implicated H2S-mediated cell signaling as an important factor in cancer cell biology; revealing the potential medicinal power of H2S-based therapies.3,4

Detection strategies for H2S depend upon its unique chemical properties. H2S is a weak, diprotic acid that can exist in three different forms (H2S, HS−, and S2). The H2S/HS− couple is the most relevant pair in biological systems with a pKa1 of approximately 7.4. Unlike the more electrophilic H2S, HS− is a potent nucleophile that can readily react with a diverse array of electrophiles. Additionally, the sulfur in H2S is in its lowest oxidation state (−2) and is readily oxidized by molecular oxygen. Due in part to these two factors, H2S is unstable and decays in aerobic solutions with a reported half-life on the order of minutes.5 As such, attempts to detect and quantify H2S in biological systems are notoriously difficult. Although there are several methodologies available for sulfide detection, each has its limitations.6 The earliest and most commonly used H2S detection assays include iodometric titrations or spectrophotometric detection via the formation of methylene blue.7,8 Despite their popularity, both methods suffer from high limits of detection (LOD) and interference issues arising from non-specific assay interactions. Similarly, methylene blue production requires high zinc chloride concentrations (50–100 mM) to limit H2S volatilization; however, high Zn2+ can cause sample degradation, such as proteolysis. Fluorescence-based probes are becoming increasingly popular due to their specificity and low signal-to-noise ratios (S/N); however, probe stability, solubility, and slow reaction kinetics can result in less than optimal assay performance.9 Similarly, many reported sulfide-specific fluorescent probes are not commercially available and therefore need to be synthesized.9 Gas chromatographic techniques often enable the detection of extremely low (picomole) amounts of H2S yet their implementation can often be experimentally demanding.6,7,10 Electrochemical methods are unique in that they offer the ability to measure H2S production in real time; however, these techniques can suffer from sulfur poisoning at the electrode surface or require S2− specific electrodes that operate best at pH values > 12.7,9,11 More recently, pulsed electrochemical detection (PED) methods have eliminated the sulfur poisoning and high pH issues and operate with a wide linear dynamic range; however, these techniques demand high sample volumes.12 Lastly, H2S detection via reverse phase (RP) high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with fluorescence detection through the sulfide-reactive fluorescence probe monobromobimane (MBB) allows for H2S detection with a LOD in the low to mid nM range.13–16 This technique, however, requires a large excess of MBB (5–10 mM) in order to achieve efficient sulfide sulfide dibimane (SDB), whose parent HPLC peak can interfere with SDB concentrations < 1 μM.15 To remove this interference, samples are often treated with ethyl acetate to extract SDB. In order to circumvent these potential issues, reduce the number of steps and add to the list of established sulfide detection assays, new methods to accurately measure hydrogen sulfide that are compatible with biological samples in situ are desired.

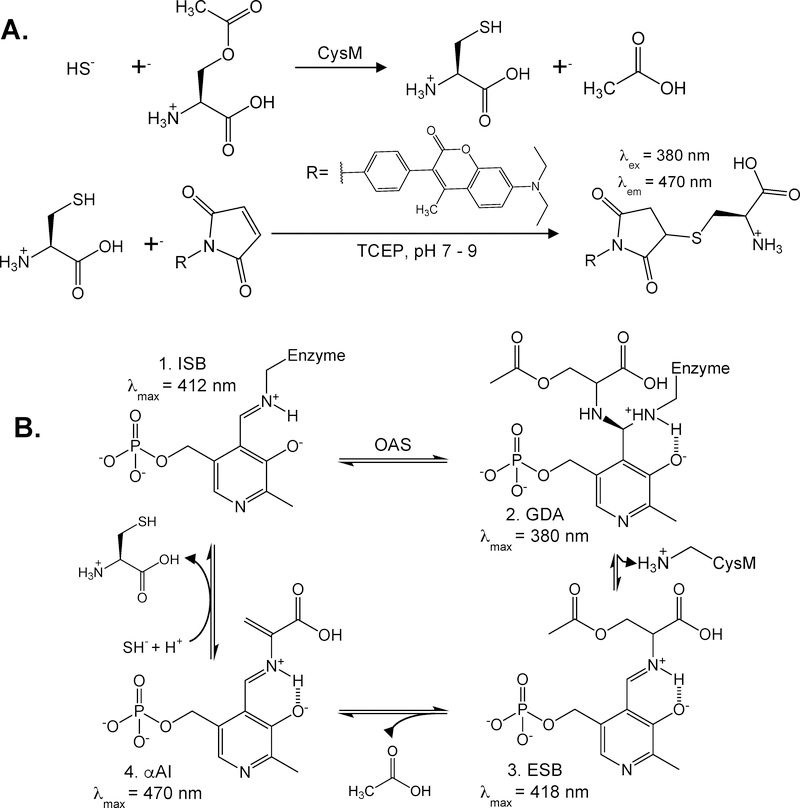

Herein, we describe an HPLC-based H2S detection assay utilizing the Escherichia coli O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase isoenzyme B, also known as CysM. The assay is carried out in two steps (Figure 1A). First, H2S is transformed into L-cysteine in the presence of O-acetylserine (OAS) via the enzymatic activity of CysM, followed by L-cysteine derivatization with the thiol reactive dye 7-diethylamino-3-(4-maleimidophenyl)-4-methylcoumarin (DMM) for HPLC fluorescence detection. In the presence of CysM, conversion of L-cysteine depends on the pyrixoyl-5-phosphate (PLP) cofactor,17-20

Figure 1: Overview of (A) CysM enzyme-coupled hydrogen sulfide detection assay and (B) CysM catalyzed L-cysteine production.

A) Step one involves incubation of the sulfide-containing samples with OAS and CysM to form L-cysteine and acetate. L-cysteine is then reduced with TCEP prior to derivatized with thiol-reactive dye DMM prior to HPLC separation and fluorescence detection. B) Abbreviated reaction cycle of L-cysteine production by CysM.17,19 (1. Internal Schiff Base [ISB], 2. Geminal diamine [GDA], 3. External Schiff Base [ESB], and 4. α-Aminoacrylate Intermediate [αAI]).

The rate determining step of L-cysteine production is the formation of the α-Aminoacrylate intermediate (αAI, k ~ 280 s−1), but providing the αAI prior to HS− exposure forms L-cysteine rapidly with reported rate constants > 1.0 ×103 s−1.20 CysM and OAS are both in excess throughout the assay and H2S reacts rapidly to form the stable L-cysteine product as it is generated, thereby largely out competing H2S oxidation. The second step of the assay involves a pre-column derivatization of L-cysteine with DMM. DMM is a weakly fluorescent molecule but it reacts rapidly with thiols to form a brightly fluorescent thiol-DMM product. The cysteine-DMM derivatives are then resolved with RP-HPLC and detected fluorescently. With a solvent ratio of 65:35 10 mM trichloroacetic acid:acetonitrile pH 2.5 and a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min cysteine-DMM elutes in approximately 7.3–7.8 minutes and is well resolved from other thiol-DMM derivative peaks.

To validate our assay, we compared the sensitivity of the CysM enzyme-coupled sulfide detection assay to the methylene blue (MB) assay.8 The CysM assay is approximately 120 times more sensitive than the MB assay, highlighting its advantage over previously well-established sulfide detection methods. We then used the CysM assay to quantify H2S release during lysinoalanine (LA) cross-link formation in the oral pathogen Treponema denticola (Td) flagellar hook protein FlgE.21 In this system we were able to successfully detect and quantify stoichiometric amounts of H2S production. The assay is quite tolerant to changes in buffer, pH, CysM and OAS concentration, dilution factors, and injection volume. The LOD of our CysM HPLC assay is 102 nM (0.12 ng), with a limit of quantification (LOQ) of approximately 330 nM (0.24 ng), but for a given circumstance these parameters could be substantially optimized. Unlike previously reported methods, our enzyme coupled RP-HPLC assay traps H2S in the form of the stable product L-cysteine. Importantly, enzymatic trapping allows sulfide detection over long times, which was key to characterization of the FlgE LA cross-link reaction.

3. Materials and Methods

1. CysM cloning, expression, purification and characterization

E. coli CysM (UniProtKB-P16703, EC: 2.5.1.47) was cloned from genomic DNA, ligated into the pet28a plasmid between the Nde1 and BamH1 restriction sites (5’-TATTATTATTATGGATCCTCAAATCCCCGCCCC-3’, 5’-ATAATAATACATATGATGAGTACATTAGAACAAACAATAGGCAAT-3’) and confirmed by DNA sequencing. CysM expression was carried out as described previously with minor changes.18 Briefly, the CysM pet28a construct was transformed in BL21(DE3) cells and grown in LB media supplemented with 50 mg/L pyridoxine (>98%, Sigma, CAT #: P5669) to an OD600 of 0.6–0.8 at 37°C. The cell culture was then reduced to 25°C and induced with 100 μM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). CysM induction was carried out for 12–16 hours and the cells harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm. At this time, cells were visibly yellow, indicative of proper PLP cofactor biosynthesis. The cell pellets were then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −20°C. To purify CysM, cell pellets were thawed on ice and resuspended in 60 mL of lysis buffer (25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 500 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM imidazole). The cells were then vortexed to homogeneity and sonicated on ice. The lysate was centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 45 minutes at 4°C and the supernatant collected and pooled. The supernatant was then subjected to Ni-NTA affinity chromatography, washed with 60 mL of lysis buffer containing 25 mM imidazole, and eluted in 10 mL of elution buffer (25 mM Tris, 500 mM sodium chloride, 250 mM imidazole) supplemented with 1.0 mM PLP hydrate (>98%, Sigma, CAT #:P9255). The N-terminal His6-tag was removed via overnight incubation with thrombin protease and the crude protein mixture further purified via size exclusion chromatography (SEC 26/60, Superdex 75 resin, GE Heathcare Life Sciences, Product #:17104401) in 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM sodium chloride (Figure 1A). The PLP concentration was measured using a molar absorptivity coefficient of ε414nm = 11,500−1cm−1.17 CysM concentration was measured using the Bradford method with bovine serum albumin as a standard. The PLP:CysM ratio was approximately 0.57:1 indicative of partial PLP incorporation into CysM. The CysM stock was prepared to a final concentration of 2 mM in 50 mM Tris, 150 mM sodium chloride pH 7.5, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. All buffers were prepared fresh and filtered through a 0.22 pm filter prior to use.

2. L-cysteine and sodium sulfide standard curve

All sample preparations were carried out anaerobically with freshly prepared degassed buffer until tris(carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) treatment (see below). Caution was taken when degassing samples to ensure anaerobic conditions. For L-cysteine standards, a 10x L-cysteine stock was prepared by dissolving solid L-cysteine (free base, Sigma, CAT #:C7755) to a final concentration of 100 mM in 100 mM degassed hydrochloric acid and diluted to a 1× 100 μM L-cysteine working stock solution with filtered degassed 18MΩ water. A 10× 100mM sodium sulfide (anhydrous, Alfa Aesar, CAT #:65122) stock solution was prepared similarly but was dissolved in degassed 100 mM sodium hydroxide and diluted to a 1× 100 μM working stock with filtered degassed 18 MΩ water. For L-cysteine and sodium sulfide standard curve measurements, all samples were performed in triplicate and error bars corresponding to +/− the standard deviation are displayed where relevant. To prepare the standard curves, 1x L-cysteine or sodium sulfide stocks were diluted to a final volume of 50 μL in 1X FlgE crosslinking buffer pH 7.5 (XLB, 40 mM Tris, 160 mM sodium chloride, 1.0M ammonium sulfate). For sodium sulfide samples, 1.5 μL of 2 mM CysM in degassed 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM sodium chloride and 1.0 μL of 50 mM O-acetylserine (Chem-Impex, CAT #:09096) in degassed 18 MΩ water were added to yield final concentrations of 60 μM and 1.0 mM, respectively. Samples were incubated anaerobically for 20 minutes to ensure full L-cysteine conversion and then reduced by the addition of 5.0 μL 220 μM TCEP (Oakwood Chemicals, CAT #:M02624). To each sample, 100 μL 18MΩ water was added to dilute the final TCEP concentration to 7 μM and transferred to a 10kDa MWCO centrifugal filter (EDM-Millipore, CAT #: UFC501096) and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 25°C. After centrifugation, 40 μL of protein-free sample was collected and diluted to 50 μL via the addition of 10 μl 250 μM DMM (>95%, Sigma, CAT #:C1484) in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, Amresco, CAT #: UN182) to yield final DMM and DMSO concentrations of 50 μM and 20% (v/v), respectively. The samples were briefly vortexed, centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 30 seconds and incubated for 20 minutes in the dark at 25°C. Samples were then acidified via the addition of 10 μL 1 M hydrochloric acid and transferred to brown HPLC-compatible injection vials. The vials were then inserted into an auto-sampler prechilled to 4°C and 10 μL injected onto a RP-HPLC C18 column pre-equilibrated with 65:35 10 mM trichloroacetic acid pH 2.5 (Oaskwood Chemical, CAT #:005004): acetonitrile (Fisher, CAT #: A988–4). Samples were eluted under isocratic conditions at a flow rate of 1.0 mg/mL. The L-cysteine-DMM peak eluted after approximately 7.3–7.8 minutes, and the peak area measured and plotted against starting sulfide or L-cysteine concentrations. Three standard curves were generated: (1) analytical grade L-cysteine standards from 0 – 25 μM, (2) CysM:OAS with sodium sulfide standards from 0 – 25 μM, and (3) CysM:OAS with sodium sulfide standards from 0 – 2.0 μM. All curves were linear within the aforementioned concentration range with R2 of ~ 0.99. For clarity, all chromatograms were aligned to the highest peak within the 7.2 – 8.4 elution time window; however, see SI for the unaligned HPLC chromatogram for both the 7.2–8.4 min region and entire 20-minute run.

3. Quantification of H2S in the presence of L-cysteine

For each sample, 10 μM L-cysteine was added prior to H2S addition (2, 4 and 6 μM). For samples untreated with CysM, 1.5 μL ddH2O was added in lieu of 2 mM CysM. Samples were reacted and derivatized as previously described. Two different methods were used to determine the H2S concentration. In the first case, the peak areas were subtracted (CysM-treated minus untreated) and the remaining area used to calculate the H2S concentration according to a standard calibration as described above. In the second method, the cysteine concentration was determined in the sample and then this concentration of cysteine was added to the H2S containing-samples used to generate the standard curve. The new calibration curve with the baseline L-cysteine concentration included in each measured H2S value was then used to determine the unknown H2S concentration, Unless specified, each sample was prepared in triplicate with the error bars representing +/− the standard deviation of all three trials.

4. Interference assay

To assess the interference of biologically relevant thiols for the CysM assay, 6 μM H2S was incubated with 60 μM CysM and 1.0 mM OAS in the presence of 5 μM glutathione, L-methionine, 2-mercaptoethanol (βME) and dithiothreitol (DTT). In addition, an anion cocktail containing 100 μM sodium fluoride, sodium citrate, sodium bromide, sodium phosphate, sodium nitrate, sodium sulfite, sodium thiocyanate and sodium carbonate supplemented with 10 Μm EDTA was also tested for interference. To prepare a 5x stock of the anion cocktail, 500 mM stocks of each salt were prepared fresh and diluted to 500 μM in degassed ddH2O. Single samples were reacted and prepared as described previously.

5. Sulfide quantification using the methylene blue (MB) sulfide detection assay

Sulfide detection using the MB assay was carried out as described previously.8 Briefly, 50 μL sodium sulfide standards were prepared in crosslinking buffer (XLB, 40 mM Tris pH 8.5, 160 mM sodium chloride, 1 M ammonium sulfate) over a 0 – 50 μM concentration range. To the 50 μL standards, 50 μL 20 mM N,N-dimethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine sulfate (DMPS, >98.0%, T.C.I., CAT #: D0782) in 7.2 M hydrochloric acid was added, followed by 50 μL 30 mM ferric chloride hexahydrate (99.0%, Fisher, CAT #: I88–500) in 1.2 M hydrochloric acid. The MB sulfide standards were incubated anaerobically for 20 minutes in the dark and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 13,000 rpm. For each sample, 100 μL of supernatant was then transferred to a quartz cuvette with a 1 cm path length and the absorbance measured at 675 nm and 747 nm. Calibration curves were generated by plotting absorbance intensity versus sulfide concentration and were linear over the 0–50 μM concentration range with R2 values ~ 0.99 (Figure S5).

6. Measuring sulfide production by FlgE lysinoalanine crosslinking

FlgE sample preparation was carried out in a similar manner to the L-cysteine and sodium sulfide standard curve samples with minor changes. Briefly, for the FlgE lysinoalanine cross-linking samples, the CysM concentration was reduced from 60 μM to 5 μM, and the OAS concentration increased from 1 mM to 5 mM. Samples were incubated anaerobically for 48 hours at 25°C and processed as described above. For this concentration of CysM and OAS, a new standard curve was generated and was found to be non-linear; thus, a polynomial fit was used to establish a standard curve and thereby determine the H2S concentration, which was then compared to the percept crosslinking observed on SDS-PAGE. Recombinantly expressed and purified T. denticola FlgE was prepared as previously described.21Cross-linking yields were determined by measuring band intensity using the image analysis software FIJI.22

7. UV-Vis spectroscopy and high-performance liquid chromatography

Absorbance measurements were made on an Agilent Technologies UV-Vis spectrophotometer (model #:8453). The tungsten and deuterium lamps were allowed to warm up for 10 minutes prior to absorbance measurements. HPLC experiments were carried out with an Agilent Technologies 1100 Series high-performance liquid chromatography system equipped with an inline degasser (JP13207221), quaternary pump (US83103638), and fluorescence detection capabilities (DEAEJ00250). Samples were injected into am Agilent Eclipse plus C18 (3.5μm × 4.6mm × 100mm) column and eluted under isocratic conditions. Fluorescence detection was carried out with excitation and emission wavelengths of 380 nm and 470 nm, respectively. All buffers were prepared fresh and filtered through a 0.22 μm filter prior to use. Recorded peak areas were integrated and calculated using OpenLab CDS Software with the following parameter settings: slope sensitivity – 0.001, peak width – 0.020, area reject – 0.001, height reject – 0.001, shoulders – OFF, and area percent reject – 0.000.

4. Results

1. CysM purification and qualitative assessment of CysM activity

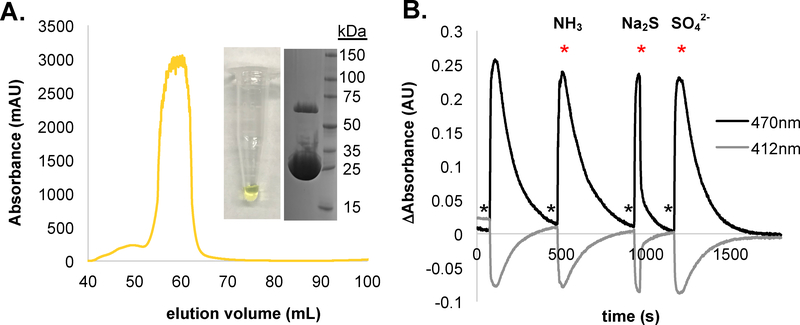

CysM is one of two O-acetylserine sulfhydrylases utilized by E. coli to produce L-cysteine. Under aerobic conditions, L-cysteine is predominately generated by isoenzyme A (CysK), while under anaerobic growth conditions L-cysteine production occurs via CysM activity.17,18,20 The crystal structure of CysM has been solved to 2.1 Å (PDB: 2BHS, 2BHT) with expression and purification conditions previously reported.18 Of the two enzymes CysM production proved most facile in our hands. CysM is active as a homodimer, with a monomeric molecular weight of approximately 32 kDa. Each subunit contains a PLP cofactor ligated through a Schiff base to the ε-amino group of Lysine-41.17–20 OAS forms an external aldimine with the PLP cofactor and then undergoes an anti-E2 elimination of acetate to form an α-Aminoacrylate intermediate (αAI) that absorbs strongly at 470 nm (Figure 1B). The αAI serves as a Michael acceptor for HS− to form L-cysteine.17–20 In agreement with previously published data, CysM purifies as a bright yellow peak with at an elution volume corresponding to a CysM homodimer (Figure 2A). SDS-PAGE reveals a final sample purity > 95% where both monomer and dimer bands are observed. Comparing protein to PLP concentration reveals a final PLP:CysM ratio of approximately 0.57:1 (data not shown). To confirm that the purified CysM is active and to rule out any potential buffer interference, we monitored the emergence and disappearance of the αAI via UV-Vis spectroscopy under varying conditions (Figure 2B). Although the addition of SO42− and NH3 have little to no effect on the 470 nm αAI consumption rate, HS− dramatically increases the αAI consumption rate. It was important to test interference by SO42− and NH3 because of their requirement for the FlgE lysinoalanine crosslinking reaction to be examined below.

Figure 2: Purification and characterization of E. coli CysM.

(A) Size exclusion chromatograph of overexpressed CysM reveals one major peak with an elution volume corresponding to a CysM homodimer. The final CysM stock was bright yellow in color, with a purity of > 95% and molecular weight of 33 kDa as estimated by SDS-PAGE. (B) Qualitative assessment of CysM activity; 1.0 mL of 60 μM CysM in 1X XLB pH 7.5 was stirred and absorbance measured in 5 second intervals at 412nm and 470nm. To test for sulfide specificity, 10 μL 10 mM OAS was added (indicated with *) and then 10 μL 10 mM reagent added (indicated with * and labeled above) once absorbance at 470nm reached a maximum.

2. Resolution of L-cysteine DMM product via RP-HPLC

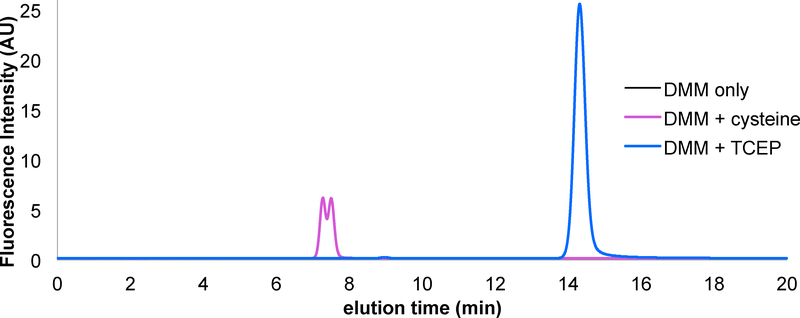

Amino acids are typically derivatized with the fluorescent amine-reactive molecule o-phthalaldehyde (OPA) for HPLC-based detection.23 Unfortunately, cysteine detection using OPA is not possible as the cysteine thiol quenches OPA fluorescence and can interfere with the derivatization reaction.23 DMM is a maleimide based fluorescence turn on probe that has been used previously for thiol derivatization and for the labeling of reactive cysteine residues.24-26 DMM is weakly fluorescent in its maleimide form; however, it undergoes a Michael addition with nucleophilic thiol species to produce a highly fluorescence thiol-DMM product that is stable for extended periods in acidic medium.24 In order to accurately measure H2S levels using this assay, it was essential that L-cysteine remained reduced. To ensure reduced L-cysteine, TCEP was added to all samples at a concentration such that DMM remained in excess. We found that DMM and TCEP react to form a fluorescent product, therefore, to accurately measure L-cysteine-DMM concentrations in the presence of TCEP it was important to resolve the L-cysteine-DMM peak from that of TCEP and other fluorescence contaminates with reverse phase HPLC. A solvent ratio of 65:35 10 mM trichloroacetic acid pH 2.5:acetonitrile at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min separates the fluorescent TCEP-DMM product from the L-cysteine-DMM product (Figure 3). The L-cysteine peak elutes after approximately 7.3–7.8 minutes with a characteristic two-humped line shape. We suspect that the two peaks result from an equilibrium between protonated and deprotonated forms of the L-cysteine-DMM product. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that reducing the pH of the solvent to 1.5 collapses the two peaks to one (Figure SI).

Figure 3: Resolution of L-cysteine and TCEP after DMM derivatization.

For each sample, 50 μM DMM in 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 was treated with excess L-cysteine (magenta) or TCEP (blue), reacted for 20 minutes and 10 μL injected onto a RP-HPLC equilibrated with 65:35 10 mM TCA pH 2.5:acetonitrile at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Comparing both runs reveal two well resolved peaks corresponding to either the L-cysteine or TCEP derivatized DMM products.

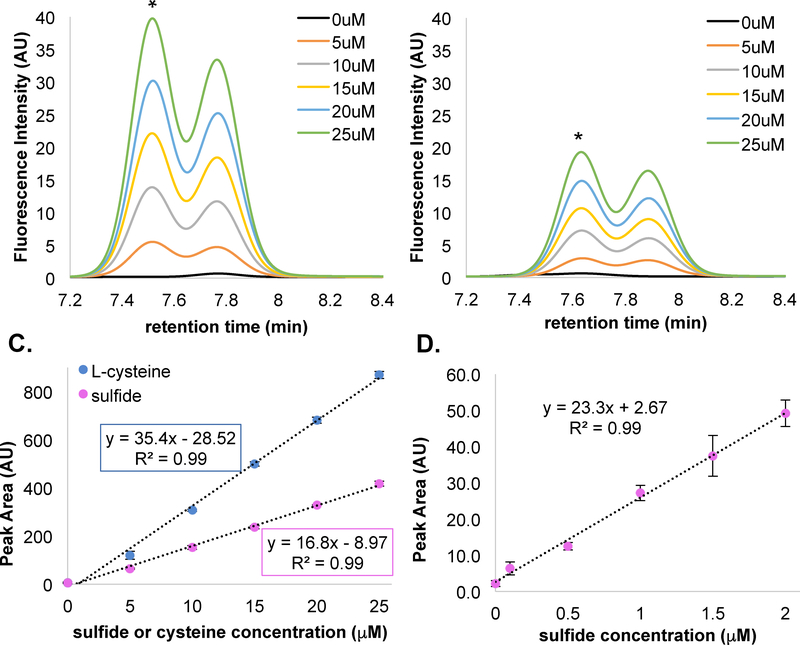

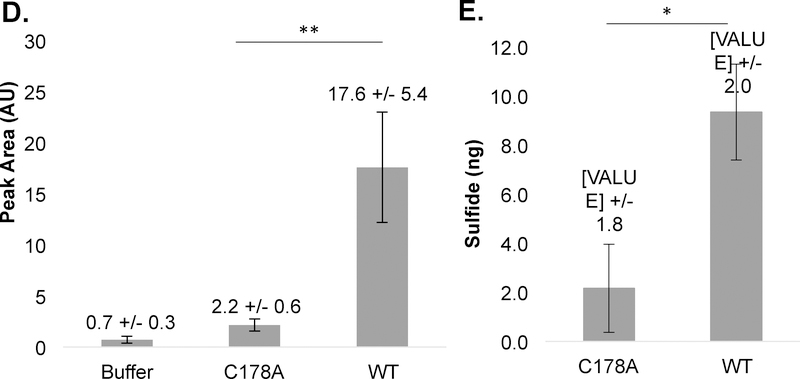

3. Generation of L-cysteine and sodium sulfide standard curves

To confirm CysM activity and determine the LOD and LOQ of our sulfide detection assay, we generated three standard curves using the CysM and DMM derivatization procedure described above. We first tested whether L-cysteine derivatization by DMM was linear over a biologically relevant concentration range. Indeed, the L-cysteine standard curve for concentrations of 0 – 25 μM is linear with a correlation coefficient of 0.99 (Figure 4A and 3C). Including a CysM L-cysteine conversion step from the reactants H2S and OAS also resulted in a nearly linear line with a correlation coefficient of 0.99 (Figure 4B and 3C). Interestingly, the H2S standard curve slope is decreased by approximately half when H2S is used as the precursor instead of L-cysteine (Figure 4C). Studies have shown that sulfate and chloride can inhibit CysK by binding to either the internal aldimine or the α-Aminoacrylate external aldimine.27 Therefore, the incomplete conversion to L-cysteine by CysM is possibly a result of allosteric inhibition of CysM activity by sulfide (or perhaps chloride). Note that to promote scavenging of most of the sulfide, the CysM concentration is commensurate with that of the sulfide concentration. Regardless, sulfide conversion by CysM under these conditions produced a consistent calibration curve that allows for accurate determination H2S via L-cysteine quantification. Repeating the experiment with a lower H2S concentration range from 0–2 μM produced a LOD and LOQ of 102 nM and 331nM H2S, respectively (Figure 4D).

Figure 4: L-cysteine and Na2S HPLC chromatograms and calibration curves.

A) Representative elution pattern of L-cysteine standards. B) Elution pattern of 0 – 25 μM Na2S standards incubated with 60 μM CysM and 1 mM OAS. Standards were run in triplicate and aligned to the largest peak marked with *. C) Comparison of L-cysteine and CysM-derived L-cysteine calibration curves plotting peak area versus sulfide/L-cysteine concentration. D) Low sulfide calibration curves (0–2 μM), Error bars reported as +/− the standard deviation of the three replicate samples. See Figure S2 for 0–2 μM chromatographs and unaligned chromatographs.

To evaluate the utility of the assay in the presence of L-cysteine, we measured the concentration of H2S in samples containing 2, 4 and 6 μM H2S in the presence of 10 L-cysteine by two different methods. The first method (Figure S3Ai) involves splitting the samples into two and then determining their L-cysteine content either with or without CysM treatment. The L-cysteine HPLC peak areas were measured and subtracted from the untreated samples to reveal the CysM-generated L-cysteine only (Figure S3B). The differential peak area was then used to calculate H2S concentration with the calibration curve reported in Figure 3C (pink). As shown in Figure S3C, the measured sulfide was systematically higher than the actual H2S levels. Thus, to more accurately determine H2S levels in samples containing L-cysteine, a new H2S calibration curve was generated in the presence of the determined L-cysteine concentration (10 ΩM, Figure S3D) and sulfide levels from these standard measurements that contain the predetermined L-cysteine offset (Figure S3E). In this case, the measured H2S levels agreed with the expected concentrations.

4. Testing for interfering compounds

In addition to L-cysteine, we also assessed whether several other relevant thiols (e.g. glutathione, L-methionine, 2-mercaptoethanol (βME) and dithiothreitol (DTT)) interfered with L-cysteine production or derivatization. As shown in Figure S4 (A-E), the presence of stoichiometric amounts of these thiol-containing small molecules did not interfere with CysM-mediated L-cysteine formation, nor did any compound tested overlap with the L-cysteine-DMM peak. It should be noted that both glutathione and DTT eluted within 30 seconds of the L-cysteine-DMM peak; however, the peaks did not completely overlap with the L-cysteine and could be deconvoluted (Figure S4B and S4E). We also confirmed that anions other than HS− (e.g. fluoride, bromide, citrate, phosphate, sulfite, nitrate, carbonate, and thiocyanate) had no effect on the production or derivatization of L-cysteine (Figure S4F).

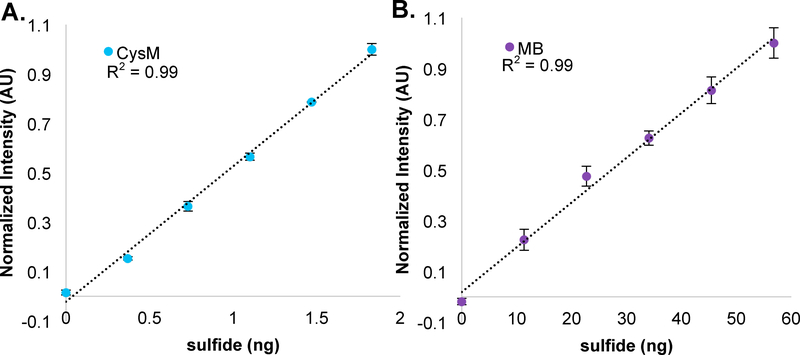

5. Comparison of the CysM and Methylene Blue sulfide detection assays

The MB colorimetric assay proceeds when acid-labile hydrogen sulfide reacts with excess DMPS and Fe3+ to yield methylene blue.8 Methylene blue concentrations can be followed spectrophotometrically through absorbance at 675 nm and 747 nm and thereby serves as an indirect measure of H2S.6–8 To contrast the sensitivities of the CysM and MB assays, we compared sodium sulfide standards measured using our CysM assay (blue spheres) to those measured using the MB method (purple spheres). As shown in Figure 5, the CysM assay standard curve slope (m) is 39.28 +/− 0.05 times greater than the slope of the MB assay calibration curve. Tabulated in Table 1, the signal to noise ratio (S/N, m/⟨σ⟩) for the CysM assay (S/N = 43.4) is ~120 times greater compared to the MB assay (S/N = 0.45). Thus, the specificity imparted by CysM activity, sensitivity of DMM derivatization and fluorescence detection, and the resolution power of RP-HPLC combine to provide a high S/N ratio that far surpasses that of the MB assay allowing detection of low ng quantities of sulfide.

Figure 5: Comparing CysM and MB sulfide detection assays.

For each set of standards, the total amount of sulfide present in each sample was calculated and plotted versus the normalized signal intensity. A) CysM (blue spheres), or B) MB (purple spheres) assay data points were fit to a line and the slopes calculated and compared. Standards were prepared in triplicate with +/− the standard deviation represented by error bars. The CysM standards were taken from Figure 4B and the MB assay standards reported in Figure S5.

Table 1:

Comparing CysM and MB assay sensitivities

| Assay | Slope (m) | Slope error | Average error (⟨σ⟩) | S/N (m/⟨σ⟩) | S/N error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MB | 0.0140 | 0.0005 | +/− 0.039 | 0.36 | +/− 0.04 |

| CysM | 0.55 | 0.02 | +/− 0.012 | 43 | +/− 2 |

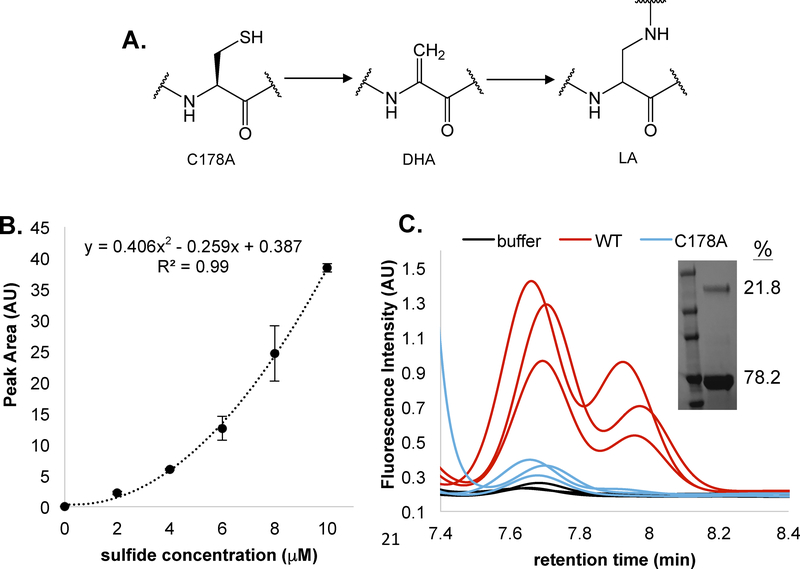

6. Hydrogen sulfide is the by-product of FlgE lysinoalanine (LA) cross-link formation

Our major motivation in developing this assay was to detect sulfide release during the LA cross-linking reaction catalyzed by the spirochete T. denticola flagellar hook protein FlgE.21 This reaction presents challenges for sulfide detection as it occurs slowly in aerobic solution and requires high concentrations of ammonium sulfate to promote protein association. TdFlgE undergoes a self-catalyzed polymerization reaction with other FlgE subunits via the formation of a covalent LA cross-link.21 The LA cross-linkage connects the D1 and D2 domains of adjacent FlgE monomers and is essential for translational motility. Cross-linking occurs between Lysine-165 (K165, Td numbering) and cysteine-178 (C178) in at least two distinct biochemical steps. First, C178 undergoes a β-elimination to form the dehydroalanine (DHA) intermediate (Figure 6A). Second, DHA serves as a Michael acceptor and reacts with the K165 side chain ε-amine from a neighboring FlgE monomer to form the mature LA cross-link (Figure 6A).21 The 7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole (NBD-N3) sulfide-detection assay suggested that FlgE crosslinking indeed releases H2S; however, due to the instability of the detection probe over the 48-hour incubation time of the assay, we sought to generate an orthogonal assay that could report on H2S evolution in situ that was also compatible with long assay durations (Lynch et. al., in preparation, see for review only material).28 CysM proved stable over the required time; however, OAS degradation became problematic. CysM will degrade OAS to ammonia and pyruvate under certain conditions, and variables such as buffer pH and incubation times should be considered when applying this assay to a particular system of interest.17,19 Monitoring the αAI stability in XLB pH 7.5 at a CysM and OAS concentration of 60μM and 1mM reveals that the αAI is only stable for approximately 45 minutes at 25°C (Figure S6). Therefore, in order to circumvent this issue, we decreased the enzyme concentration to 5 μM and increased the OAS concentration to 5 mM for the TdFlgE crosslinking samples. OAS concentrations that exceed 10 mM in certain buffers can result in CysM and/or FlgE precipitation and thus attention to solvent conditions is imperative. Interestingly, with concentrations of CysM of 5 μM and OAS of 1mM, the sulfide standard curve is no longer linear over a the 0–10 μM sulfide range and is more accurately fit to a polynomial function (Figure 6B). We suspect this non-linear behavior is the result of other processes such as de-gassing of H2S and oxidation out completing CysM when the sulfide-concentration is low. Nonetheless, the standard curve is reproducible and allows for an accurate assessment of absolute sulfide production. To determine the quantity of sulfide release by TdFlgE, we compared the FlgE L-cysteine-DMM peak area to that determined by the standard curve of sodium sulfide (Figure 6B and 6C). Thus, we effectively integrate the amount of sulfide released during the entire cross-linking reaction and then compare it to the amount of cross-linked FlgE produced. Importantly, CysM and excess OAS is present during the cross-linking reaction so that sulfide is trapped as L-cysteine as it is liberated from FlgE. Cross-linking of full-length recombinant TdFlgE resulted in the release of 9.3 +/− 2.0 ng HS− from 30 μM TdFlgE (18.3 +/− 3.7%, Figure 6D and 6E). This value compares well to the 21.8% crosslinking determined by SDS-PAGE (Figure 6C, inset). A C178A TdFlgE mutant which does not cross-link produced only 2.2 +/− 1.8 ng HS−. This data validates HS− as a by-product of FlgE LA cross-linking and supports similar findings from other orthogonal sulfide detection methods.

Figure 6: Measuring sulfide release by T. denticola FlgE lysinoalanine cross-linking.

A) Minimal mechanism of lysinoalanine (LA) cross-link formation, (cysteine-178 [C178], dehydroalanine [DHA] and lysinoalanine [LA]). B. H2S calibration curve using 5 μM CysM and 1 mM OAS in 1X XLB pH 7.5. C) HPLC chromatograms of wild type (WT, red) and C178A (blue) full-length TdFlgE crosslinking samples where the inset shows the SDS-PAGE gel of WT TdFlgE with a quantification of the HMWC relative to the monomeric TdFlgE. Band intensity measurements were carried out using FIJT21 D) Peak area measurements of (C) result in an 8-fold increase in the peak area for WT compared to C178A TdFlgE. E) Buffer-subtracted H2S quantities of WT TdFlgE (9.3 +/− 2.0 ng corresponding to a concentration of 5.6 +/− 1.1 μM) and C178A TdFlgE (2.2 +/− 1.8 ng corresponding to a concentration of 1.3 +/− 0.7 μM). For WT TdFlgE, 5.5 +/− 1.1 μM HS− corresponds to approximately 18.6 +/− 3.7% of the total TdFlgE concentration, in agreement with the 21.8% of cross-linked species observed via SDS-PAGE. Statistical significance was confirmed via a two-tailed unpaired students t-test (** = p < 0.01, * = p < 0.05).

5. Discussion

The assay described herein allows H2S levels to be accurately measured in situ by converting H2S to L-cysteine. L-cysteine can then be readily derivatized using the thiol-reactive probe DMM and separated by RP-HPLC with fluorescence detection capabilities. Unlike previously reported assays, which typically measure H2S chemical reactivity levels indirectly, employing CysM to convert H2S into L-cysteine transforms the highly reactive H2S molecule to a more stable and less reactive L-cysteine moiety and thus provides a direct measure of H2S concentration. The CysM assay is capable of detecting biologically relevant concentrations of H2S, with a LOD and LOQ of 102 nM and 331 nM, respectively. We believe that a lower LOD and LOQ could be attained by altering variables such injection volume, dilution factor, assay volume, and CysM or OAS concentration. Furthermore, L-cysteine production could be detected by LC-MS instead of by DMM derivatization if fluorescence HPLC is not available. When preparing for and carrying out this assay, several factors are essential to ensure reproducibility and assay success. First, in our experience, CysM expression in E. coll BL21(DE3) cells works best a 25°C. At all three induction temperatures tested (17°C, 25°C, and 37°C) we observed a fraction of CysM in inclusion bodies; however, at 25°C this fraction was much smaller than compared to that at 37°C (data not shown). Therefore, it is recommended to ensure that the bacterial culture has reduced to room temperature before inducing with IPTG. Second, throughout the course of troubleshooting the assay, it was found that concentrations of OAS exceeding 10 mM resulted in protein precipitation. Therefore, when working in buffer conditions different than what is reported here, it is advised to test CysM stability at the needed OAS concentration. Third, it is advised to monitor the αAI decay kinetics for a given CysM and OAS concentration to assure that OAS is always in excess. Previous data demonstrated a clear pH dependence on the rate of OAS degradation.20 We found that at a buffer pH of 7.5, 60 μM CysM will degrade 1 mM OAS in approximately 45 minutes, whereas increasing the pH to 8.5 accelerated OAS degradation to 25 minutes (Figure S6). Therefore, it is essential to fully characterize the enzymatic activity in the assay buffer of choice over the duration of the assay. It should be noted, however, that the pH dependence refers only to the stability of the αAI only; L-cysteine production by CysM was found to be invariant over a pH range of 7 – 9. Once L-cysteine has been derivatized with DMM and acidified with hydrochloric acid, the by-product is quite stable. Re-screening the calibration curve samples shown in Figure 4 after seven days incubated at room temperature produced similar chromatogram profiles; however, the retention times and peak areas varied significantly (Figure S7). Therefore, it is recommended that all samples being tested are processed and derivatized immediately on that day of the experiment.

The CysM assay is relatively robust from interference by L-cysteine and related thiols. Samples that also contain L-cysteine can be processed by first determining the amount of L-cysteine by DMM derivatization and then establishing a standard sulfide curve with this amount of L-cysteine present to be used for quantification of the L-cysteine containing sample (Fig. S3D and S3E). Because specificity of the assay comes from the selectivity of CysM for sulfide and also the chromatographic characteristics of DMM-derivatized L-cysteine, there is little interference from other biological thiols or anions (Fig. S4). That said, caution should be taken when working with solutions containing excess glutathione and DTT, as these compounds elute within 30 seconds of L-cysteine-DMM using the HPLC conditions reported here. For these scenarios, further optimization of the TCA/acetonitrile ratio will likely ensure improved peak resolution. The most significant complication of the assay is the fact that CysM conversion of H2S to L-cysteine is not necessarily stoichiometric and the yield of conversion depends on conditions. The reason for this variability stems from the rate of CysM conversion compared to the rate of other reactions, such as sulfide oxidation and H2S degassing. Fortunately, if calibration curves with pure sulfide are made under the same conditions of the samples (particularly with respect to pH and concentration range), accurate sulfide quantification is achieved.

Overall, employing CysM to convert H2S to L-cysteine is a useful method for measuring H2S levels in biological samples and this assay exhibits superior sensitivity compared to the commonly employed methylene blue sulfide detection assay. Converting H2S to L-cysteine circumvents the stability and oxidation issues commonly associated with H2S measurements and allows for facile derivatization with a fluorophore. With OAS in excess, kinetically favored L-cysteine production can effectively trap H2S over long periods of time in a manner that competes effectively with H2S oxidation in aerobic conditions.

Supplementary Material

9. Acknowledgements

The authors thank Angela Picciano and Estella Yee for experimental assistance and helpful insight during troubleshooting. We also thank Alexandrine Bilwes-Crane for editing the manuscript and Chunhao Li for supplying the plasmid encoding for recombinant T. denticola FlgE (Grant #: DE023080, Philips Institute for Oral Health Research - Virginia Commonwealth University School of Dentistry).

3. Funding - This work was supported by NIH grant R35 122535 (B.R.C.) and the CBI Training grant T32 GM008500 (M.J.L. and B.R.C.)

8. Abbreviations

- αAI

α-Aminoacrylate intermediate

- RP

reverse phase

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- OAS

O-acetylserine

- MBB

monobromobimane

- SDB

sulfide dibimane

- βME

2-mercaptoethanol

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- DHA

dehydroalanine

- LOD

limit of detection

- LOQ

limit of quantification

- DMM

7-diethylamino-3-(4-maleimidophenyl)-4-methylcoumarin

- OPA

o-phthalaldehyde

- PLP

pyridoxyl-5-phosphate

- TCEP

tris(carboxyethyl)phosphine

- XLB

crosslinking buffer

- NBD-N3

7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole

- MB

methylene blue

- DMPS

N,N-dimethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine sulfate

- m

slope

- ⟨σ⟩

average error

Footnotes

Notes - The authors declare no competing financial interest

10. References

- 1.Wang R (2002) Two’s company, three’s a crowd: can H2S be the third endogenous gaseous transmitter? FASEB J. 16, 1792–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filipovic MR, Zivanovic J, Alvarez B and Banerjee R (2017) Chemical Biology of H2S Signaling through Persulfidation, Chem. Rev, 118, 1253–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao X, Ding L, Xie Z, Yang Y, Whiteman M, Moore PK, and Bian J-S (2018) A Review of Hydrogen Sulfide Synthesis, Metabolism, and Measurement: Is Modulation of Hydrogen Sulfide a Novel Therapeutic for Cancer? Antioxid. Redox Signal, 0, 1–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallace JL, and Wang R (2015) Hydrogen sulfide-based therapeutics: exploiting a unique but ubiquitous gasotransmitter. Nat. Rev. | DRUG Discov 14, 329–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Göte H, and Alexander J (1963) Oxidation rate of sulfide in sea water, A preliminary study. J. Geophys. Res 68, 3995–3997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawrence NS, Davis J, and Compton RG (2000) Analytical strategies for the detection of sulfide: a review. Talanta 52, 771–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin VS, Chen W, Xian M, and Chang CJ (2015) Chemical probes for molecular imaging and detection of hydrogen sulfide and reactive sulfur species in biological systems. This J. is Cite this Chem. Soc. Rev 44, 4596–4618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moest RR (1975) Hydrogen sulfide determination by the methylene blue method. Anal. Chem 47, 1204–1205. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, Yin C, and Huo F (2015) Chromogenic and fluorogenic chemosensors for hydrogen sulfide: review of detection mechanisms since the year 2009. RCS Advances 5, 2191–2206. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitvitsky V, and Banerjee R (2015) H2S Analysis in Biological Samples Using Gas Chromatography with Sulfur Chemiluminescence Detection. Methods Enzymol. 554, 111–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeroschewski P, Haase K, Trommer A, and Grundler P (1994) Galvanic sensor for determination of hydrogen sulfide. Electroanalysis 6, 769–772. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall JR, and Schoenfisch MH (2018) Direct Electrochemical Sensing of Hydrogen Sulfide without Sulfur Poisoning. Anal. Chem 90, 5194–5200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen X, Pattillo CB, Pardue S, Bir SC, Wang R, and Kevil CG (2011) Measurement of plasma hydrogen sulfide in vivo and in vitro. Free Radic. Biol. Med 50, 1021–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Togawa T, Ogawa M, Nawata M, Ogasawara Y, Kawanabe K, and Tanabe S (1991) High Performance Liquid Chromatographic Determination of Bound Sulfide and Sulfite and Thiosulfate at Their Low Levels in Human Serum by Pre-column Fluorescence Derivatization with Monobromobimane. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 40, 3000–3004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen X, Kolluru GK, Yuan S and Kevil CG (2015) Methods in enzymology 554, 31–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wintner EA, Deckwerth TL, Langston W, Bengtsson A, Leviten D, Hill P, Insko MA, Dumpit R, VandenEkart E, Toombs CF, and Szabo C (2010) A monobromobimane-based assay to measure the pharmacokinetic profile of reactive sulphide species in blood. Br. J. Pharmacol 160, 941–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chattopadhyay A, Meier M, Ivaninskii S, Burkhard P, Speroni F, Campanini B, Bettati S, Mozzarelli A, Rabeh WM, Li L, and Cook PF (2007) Structure, Mechanism, and Conformational Dynamics of O-Acetylserine Sulfhydrylase from Salmonella typhimurium: Comparison of A and B Isozymes, Biochemistry, 46, 8315–8330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Claus MT, Zocher GE, Maier THP, and Schulz GE(2005) Structure of the O-Acetylserine Sulfhydrylase Isoenzyme CysM from Escherichia coli Biochemistry 44, 8620–8626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tian H, Guan R, Salsi E, Campanini B, Bettati S, Kumar VP, Karsten WE, Mozzarelli W, and Cook PF (2010) Identification of the Structural Determinants for the Stability of Substrate and Aminoacrylate External Schiff Bases in O-Acetylserine Sulfhydrylase-A, Biochemistry 49, 6093–6103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabeh WM and Cook PF (2004) Structure and mechanism of O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase. J. Biol. Chem 279, 26803–26806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller MR, Miller KA, Bian J, James ME, Zhang S, Lynch MJ, Callery PS, Hettick JM, Cockburn A, Liu J, Li C, Crane BR, and Charon NW (2016) Spirochaete flagella hook proteins self-catalyse a lysinoalanine covalent crosslink for motility. Nat. Microbiol 1, 16134–16142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, and Frise E (2012) Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bidlingmeyer BA, Cohen SA, and Tarvin TL (984) Rapid analysis of amino acids using pre-column derivatization. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl 336, 93–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goncalves V, Brannigan JA, Thinon E, Olaleye TO, Serwa R, Lanzarone S, Wilkinson AJ, Edward TW, and Leatherbarrow RJ (2012) A fluorescence-based assay for N-myristoyltransferase activity. Analytical Biochemistry 421, 342–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng W, Liu G, Xia R, Abramson JJ, and Pessah IN (1999) Site-Selective Modification of Hyperreactive Cysteines of Ryanodine Receptor Complex by Quinones. Molecular Pharamacology 55, 821–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steenkamp DJ (1993) Simple methods for the detection and quantification of thiols from Crithidia fasciculata and for the isolation of trypanothione. Biochem. J 292 (Pt 1), 295–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tai C-H, Gani D, Jenn T, Johnson C, and Cook PF (2001) Characterization of the Allosteric Anion-Binding Site of O-Acetylserine Sulfhydrylase. Biochemistry 40, 7446–7452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou G, Wang H, Ma Y, and Chen X (2013) An NBD fluorophore-based colorimetric and fluorescent chemosensor for hydrogen sulfide and its application for bioimaging. Tetrahedron 69, 867–870. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.