Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the number one cause of death in the United States and worldwide. The most common cause of cardiovascular disease is atherosclerosis, or formation of fatty plaques in the arteries. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL), termed “bad cholesterol,” is a large molecule comprised of many proteins as well as lipids including cholesterol, phospholipids, and triglycerides. Circulating levels of LDL are directly associated with atherosclerosis disease severity. Once thought to simply be caused by passive retention of LDL in the vasculature, atherosclerosis studies over the past 40–50 years have uncovered a much more complex mechanism. It has now become well established that within the vasculature, LDL can undergo many different types of oxidative modifications such as esterification and lipid peroxidation. The resulting oxidized LDL (oxLDL) has been found to have antigenic potential and contribute heavily to atherosclerosis associated inflammation, activating both innate and adaptive immunity. This review discusses the many proposed mechanisms by which oxidized LDL modulates inflammatory responses and how this might modulate atherosclerosis.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, macrophage, T-cell, B-cell, antibody, oxLDL

I. INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) accounts for 17.3 million deaths worldwide per year. The vast majority of CVD-related deaths are the direct result of atherosclerosis, characterized by narrowing of the arteries due to the formation of lipid-filled plaques. Atherosclerosis-related deaths result when these plaques rupture, inducing formation of a thrombus that results in heart attack or stroke. While many treatment options are available for CVD, including lifestyle changes and lipid lowering statins, it is expected that annual mortality will grow to almost 24 million by 2030.1 This highlights the importance for further understanding the underlying mechanism(s) of atherosclerosis to pave the way for new and novel therapeutic options.

Atherosclerosis is not a modern disease; evidence of its existence can be found dating back thousands of years. Pathologic changes resembling vascular injury and plaque formation have been identified in the arteries of ancient Egyptian mummies.2,3 However, while atherosclerosis pathogenesis appears to date back many millennia, adverse changes in the vasculature only began to be methodically studied in the 19th century. Pathologists Carl von Rokitansky and Rudolf Virchow simultaneously observed that there were changes in cellular composition within the vessel walls at the location of atherosclerotic plaques.4,5 Despite making identical observations, Rokitansky and Virchow disagreed on the cause. Rokitansky believed that the cellular changes were secondary to the changes to the vessel, whereas Virchow believed that these cells played a causal role.6

At the turn of the 20th century, Adolf Windaus observed that atherosclerotic plaques were comprised of cholesterol and calcified connective tissue. Soon after, Nikolai Anitschkow and Semen Chaltow showed that atherosclerosis could be induced by feeding rabbits a diet high in cholesterol.7,8 These studies not only identified cholesterol as an important risk factor for the development of atherosclerotic lesions but also gave way to the idea that lipids were key players in atherosclerotic plaque formation and cellular changes were secondary.

Despite the changes observed by Rokitansky and Virchow in the mid-1800s, the cellular mechanisms underlying atherosclerosis remained unclear until approximately 40 years ago when the development of specific monoclonal antibodies allowed the discovery that the majority of these cells in the vasculature of the lesion were macrophages.9 This important milestone opened the door to the hypothesis that lipid accumulation was not only a passive event in atherosclerosis but also likely induced the inflammatory changes associated with lesion development and progression. Following this initial discovery, additional immunohistochemical analyses of human atherosclerotic plaques showed the presence of many different immune cell subsets: monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), neutrophils, and CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells.10,11 High levels of major histocompatibility complex-II (MHC-II) staining on antigen-presenting cells in the lesions was also detected. This finding suggested that adaptive immunity, in addition to macrophages and other innate immune cells, may be important to atherosclerosis (reviewed in Jonasson et al. 11). Interestingly, these immune cell subsets were present in the arteries of children and young adults at predicted sites of likely plaque formation, further implicating immune inflammation in atherosclerosis development.12

These studies were paramount in establishing a role for the immune system in atherosclerosis; however, while they suggested the possibility that an immune reaction was occurring, an antigen to drive this inflammation was unknown. In the mid-1980s, Quinn et al. found that in vitro macrophages treated with oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL), a modified cholesterol found in the atherosclerotic plaque, but not native LDL, accumulated cholesterol esters.13 Shortly after, Palinski et al. showed that oxLDL could induce systemic antibody formation in hyperlipidemic apolipoprotein E (Apoe−/−) mice.14 Interestingly, many of these antibodies, termed “EO” antibodies, are immunoglobulin (Ig) M and recognize phosphorylcholine, a moiety also found in the cell walls of bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae.15 The most well recognized of these antibodies is E06. Indeed, studies of Binder et al. found that immunizing atherosclerosis susceptible low-density lipoprotein receptor deficient (Ldlr−/−) mice with Streptococcus pneumoniae protected against atherosclerosis in combination with generating high circulating levels and anti-oxLDL IgM, indicating that perhaps oxLDL elicits immune responses at least in part through molecular mimicry.16 Additional studies helped to support oxLDL as an immunologic antigen by showing that T-cell clones isolated from atherosclerotic plaques became activated by oxLDL.17 It is widely believed that native LDL cannot elicit these initial responses immune responses: oxidation or some other modification, such as acetylation, to the LDL is required to expose the neo-antigens responsible for inducing immune responses.18,19 However, studies from Hermansson et al. suggest that native LDL is also able to elicit inflammation.20 Together, these studies identified oxLDL as a key antigen in atherosclerosis driving the immune response in atherosclerosis.

These seminal studies strongly indicated that classic atherosclerosis was a complex disease driven by immune-mediated inflammation, and they highlighted the importance of better understanding how oxLDL activates inflammatory responses. In this article, we review the proposed mechanisms by which oxLDL mediates the chronic systemic inflammation associated with atherosclerosis and CVD.

II. oxLDL AND INNATE IMMUNITY

Many of the first studies to elucidate the immune response in atherosclerosis focused on monocytes and macrophages due to their early arrival at the site of injury. Circulating oxLDL has been shown to enhance monocyte binding to endothelial cells in a mechanism independent of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression.21 Once these cells enter the vasculature, they have a strong propensity to become lipid-laden foam cells. As previously mentioned, in vitro studies found that macrophages treated with oxLDL formed foam cells, but those treated with native LDL did not.13 Early studies by Brown and Goldstein identified a binding site on macrophages that allowed for this cholesterol uptake and deposition, which they called “scavenger receptors.”22 At least 10 different groups of scavenger receptors are based on structure and function (reviewed in Zani et al.23). The first of these scavenger receptors identified was SR-A, which comes in several different subtypes and is known to be able to bind and facilitate uptake of modified LDL.24

Perhaps the best known and most well characterized of the scavenger receptors is CD36. Well known for its function in binding fatty acids, this receptor also recognizes oxidized phospholipids, including oxidized LDL and blockade of CD36 with a specific antibody, prevents up to 50% of oxLDL binding to the human macrophage THP-1 cell line.25 Likewise, macrophages isolated from Cd36/Apoe double knockout mice are defective in oxLDL uptake.26 Internalized oxLDL has been shown to be a ligand for PPARγ, and binding of oxLDL to PPARγ creates a positive feedback loop, upregulating CD36 expression and facilitating further oxLDL uptake by macrophages.27,28 In terms of atherosclerosis, genetic deletion or chemical blockade of CD36 in atherosclerosis susceptible murine models is protective.26,29,30 Bone marrow transplant studies have demonstrated that loss of macrophage-specific CD36 conferred these protective effects.31

In addition to binding to scavenger receptors to facilitate oxLDL uptake and enhance atherosclerotic burden, there is evidence that oxLDL is also able to bind other classes of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). Studies have shown that minimally modified LDL (mmLDL) can bind to the Toll-like Receptor (TLR) class of PRRs. More specifically, mmLDL can bind to TLRs 2 and 4 to induce the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α in an NFkB dependent fashion.32,33 Additional studies determined that this phenotype was enhanced by the presence of CD36.34 Sheedy et al. demonstrated that oxLDL activates the NLRP3 inflammasome via uptake by CD36 and the formation of a TLR4/TLR6/CD36 heterotrimer, resulting in the development of cholesterol crystals that induce lysosomal damage.35 The inflammasome is a multiple-protein oligomer that requires both a priming and activating signal for initiation. Activation of the inflammasome results in robust secretion of the inflammatory cytokine IL-1β36 The inflammasome was originally identified as an innate immune molecule necessary for the clearance of many bacterial and fungal pathogens.37,38 Inhibition of inflammasome-mediated IL-1β secretion is protective in atherosclerosis; it has been shown that knocking out the inflammasome-related gene Nlrp3 in mice completely abolishes the development of plaques.39

Although there is a great deal of free oxLDL in circulation, a large percentage of it is bound to specific antibodies forming immune complexes. These oxLDL-containing immune complexes (oxLDL-IC) induce inflammatory responses in macrophages and dendritic cells. Studies in the human macrophage cell line THP-1 show that oxLDL-ICs induce cellular activation, inflammatory cytokine production, and foam cell formation mainly by signaling through the immune complex receptor Fc gamma receptor I (FcγRI).40–42 Similar to the observation that free oxLDL activates the inflammasome through a TLR4/TLR6/CD36-dependent mechanism, we demonstrated that oxLDL-ICs act as a priming signal for the inflammasome via an FcγR/TLR4/CD36-dependent mechanism.43

Although many studies seeking to understand immune responses to oxLDL have focused on macrophages, DCs also play an important role in atherogenesis. Like macrophages, DCs are also found in large numbers in atherosclerotic lesions, specifically in areas that are prone to rupture, such as the plaque core.44,45 Interestingly, oxLDL has been shown to mature dendritic cells and induce expression of MHCII, suggesting that these cells may be most important in atherosclerosis for their ability to bridge the innate and adaptive immune systems.46,47

III. oxLDL MODULATION OF T-CELL RESPONSES

Evidence for involvement of the adaptive immune in atherosclerosis came from studies in Apoe−/− and Ldlr−/− mice on the Rag1−/− background lacking functional T-and B-cells. These mice exhibited a significant reduction in atherosclerotic lesion size, which suggests an important role for the adaptive immune system in atherogenesis.48,49 Reconstitution of CD4+ T-cells restored and even aggravated atherosclerotic lesion development in immunodeficient Apoe−/− mice.50 In immunization studies, the entire oxLDL molecule or the ApoB100 protein component of LDL induced high levels of IgG1 and IgG2a against oxLDL, suggesting that T-dependent antibody responses are at the crux of the observed protective effects.51,52 While oxLDL is widely believed to be the antigen driving T-cell responses in atherosclerosis, a study by Hermansson et al. found that inhibiting T-cell responses to native LDL are also atheroprotective.20 For specific T-cell responses to occur, there must be antigen presentation by a professional antigen-presenting cell such as a DC. Interestingly, immunization with oxLDL-pulsed dendritic cells has yielded conflicting results: studies show both atheroprotective and atherogenic effects. However, all of the adoptive transfer studies agree that oxLDL-pulsed dendritic cells elicit specific CD4 T-cell responses.53,54

Innovative studies have examined DC–T-cell interactions in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Ldlr−/− mice globally deficient in MHCII are protected from atherosclerosis due to a lack of functional T-cells in these mice, suggesting that DC–T-cell cross talk may be important in the development of atherosclerotic lesions.55 Lievens et al. discovered that disrupting signaling of the immunomodulatory cytokine transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) in CD11c+ cells of Apoe−/− mice caused expansion of effector T-cells and increased atherosclerotic lesion size.56 Another study by Subramanian et al. showed that MyD88 (a critical protein downstream of TLR4) signaling for oxLDL in CD11c+ cells is required for regulatory T-cell (Treg)–mediated protection from atherosclerosis in Ldlr−/− mice.57 An in vitro study by Lim et al. also established a role for dendritic cell MyD88 as well as CD36 in oxLDL mediated Th17 skewing.58 Therefore, DC/CD4+ T-cell interactions appear to be one of the primary drivers of atherosclerosis development and progression.

Despite substantial evidence for oxLDL-specific CD4+ T-cells in atherosclerosis-associated inflammation, the peptide epitopes that stimulate these responses remain unknown. However, studies from Tse et al. have shown that immunization with ApoB100 peptides (3501–3506 and 978–993) provides ~40% protection against atherosclerotic lesion formation, suggesting that these epitopes may be a good starting point for further investigation.59

Like CD4+ T-cells, CD8+ T-cells can be observed in the atherosclerotic lesions of both humans and mice; however, the role for these cells is less well defined.11,60,61 OxLDL-specific CD8+ T-cells have been detected in the blood of coronary artery disease patients, and immunization with the ApoB100 p210 peptide has shown atheroprotective effects in a CD8+ T-cell–dependent manner.62,63 Further understanding of the underlying DC–T-cell interactions driving the generation of oxLDL-specific T-cells will not only provide important insight into disease pathogenesis but will also aid in successful vaccine development.

IV. oxLDL AND HUMORAL IMMUNITY

While very few B-cells are actually detected in atherosclerotic lesions or their surrounding adventitia, they play an important role in oxLDL-mediated systemic inflammation. The first indications of this were experiments showing that immunization of atherosclerosis-susceptible mice and rabbits with various forms of oxLDL was atheroprotective.51,64–66 Studies by Caliguri et al. in 2002 showed that splenectomized mice developed enhanced atherosclerosis compared to sham-treated mice and that this increased atherosclerotic burden could be reversed by adoptive transfer of educated splenic B-cells.67 Notably, however, transfer of T-cells also protected against atherosclerosis in this study. Around the same time, Major et al. showed similar results in Ldlr −/− mice that received a bone marrow transplant from μMT −/− (B-cell deficient) mice. Compared to their immunocompetent counterparts, B-cell–deficient Ldlr−/− mice had increased atherosclerotic lesion size in the proximal aorta when placed on a high-fat diet, and this increase in atherosclerosis was accompanied by diminished titers of oxLDL antibodies and increased production of proinflammatory cytokines, suggesting that antibodies against oxLDL may be protective.68 A follow-up study by Ait-Oufella et al. investigated the implications of removing mature B-cells from circulation using anti-CD20 treatment in both Ldlr−/− and Apoe−/− mice. Surprisingly, treatment with anti-CD20 provided atheroprotective effects. These researchers observed that depleting B-cells with anti-CD20 dramatically decreased anti-oxLDL IgG but only minimally reduced levels of anti-oxLDL IgM, effectively increasing the IgM:IgG ratio. This led the investigators to hypothesize that anti-oxLDL IgM plays a protective role while IgG is inflammatory.69

Kyaw et al. tested this hypothesis in a series of elegant experiments that utilized adoptive transfer of either IgM-secreting B1a cells or conventional IgG-secreting B2 B-cells into Apoe−/−Rag2−/−GammaC−/− as well as B2 B-cells into Apoe−/−μMT−/− mice. These studies showed that B1a B-cells abrogated atherosclerosis, while B2 B-cells increased lesion size more than 300%.70 In a follow-up study, Kyaw validated his findings with genetic deletion of B2 B-cells using Baff−/− mice crossed to the Apoe−/− background. When these animals were placed on high-fat diet, they had significantly smaller atherosclerotic lesions in the proximal aorta compared to Apoe−/− mice. Reduced lesion size was accompanied by decreased titers of IgG and decreased levels of inflammatory cytokines.71 In terms of IgG, recent studies have shown that T-dependent production of atherogenic IgG is dependent on the presence of B-cell–specific X-box binding protein-1 (XBP1) and that germinal-center B-cells drive T-dependent IgG-secreting plasma cell differentiation.72,73 Kyaw et al. further tested the atheroprotective role of IgM using splenectomized Apoe−/− mice deficient in peritoneal B1a but not B2 B-cells. Following splenectomy, protection against atherosclerosis was achieved with adoptive transfer of wild-type B1a cells but not secretory IgM-deficient B1a cells. Mice that received protective wild-type B1a cells also had increased titers of anti-oxLDL IgM.74 Likewise, Rosenfeld et al. found that the adoptive transfer of B-lB-cells into Rag1−/−Apoe-/– mice was sufficient to produce oxLDL-specific IgM and to provide atheroprotective effects.75 B-lb–mediated protection was found to be dependent on the B-lb–specific inhibitor of differentiation-3 (Id3) gene, and polymorphisms in this gene in humans have been previously implicated as a potential risk factor for atherosclerosis development.76 The body of work identifying the atheroprotective nature of IgM is complementary to the early studies from the Witztum group, which characterized the B-1a–derived E06 IgM antibody as atheroprotective, in part by preventing the binding of oxLDL to the scavenger receptor CD36.77

Fitting nicely with the aforementioned studies, IgG and IgM titers have also been shown to correlate with atherogenesis and atheroprotection, respectively, in both mice and humans.78,79 These studies emphasize that while oxLDL activates inflammation through a variety of mechanisms, this antigen can also elicit protective immune responses. It is critical to gain further understanding of how these responses occur in order to harness the power of oxLDL as a potential therapeutic.

V. CONCLUSIONS

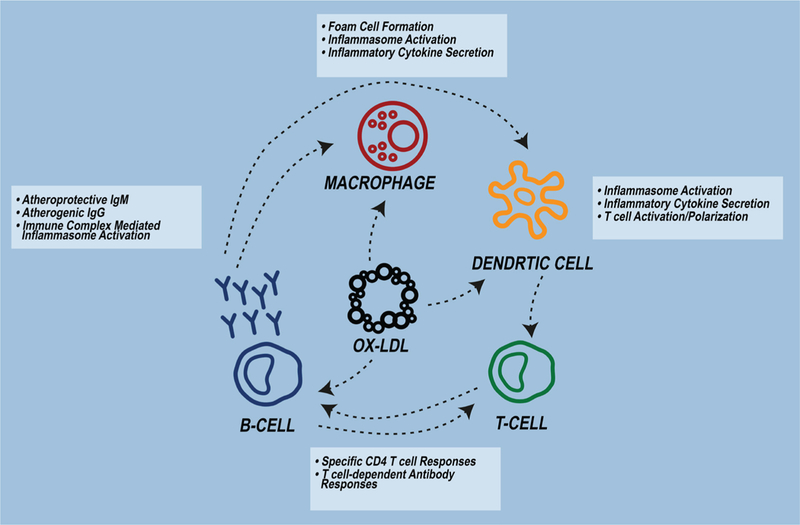

In summary, oxLDL modulates innate and adaptive immune responses and can be both pro- and anti-inflammatory (Fig. 1). Huge strides have been made over the past 40–50 years in understanding the underlying mechanisms of these responses. Many of these advances, which have centered around how oxLDL modulates inflammatory responses, have been in terms of macrophage biology as oxLDL signaling through PRRs, such as scavenger receptors and TLRs, which is known to contribute to foam cell formation and inflammatory cytokine secretion. In addition, it has become abundantly clear that oxLDL-specific T- and B-cell responses occur in atherosclerosis-associated inflammation and are important drivers of disease. However, despite advances in this field over the past several decades, further studies are needed to the answer remaining questions, including identification of the specific oxLDL epitopes that drive these T- and B-cell responses. The continued development of highly innovative studies coupled with important technological advancements positions the field to answer these questions and continue striving towards translational therapies.

FIG. 1:

OxLDL modulates innate and adaptive immunity. OxLDL activates macrophages and dendritic cells via uptake by scavenger receptors and TLRs, generates specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses, and stimulates systemic oxLDL-antibody production.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This article was funded by the National Institute of Health (Grant Nos. I01BX002968 and R03AI124190).

ABBREVIATIONS:

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- oxLDL

oxidized LDL

- DC

dendritic cell

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- ApoE

apolipoprotein E

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- Ldlr

low-density lipoprotein receptor

- PRR

pattern recognition receptor

- mmLDL

minimally modified LDL

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- IL

interleukin

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TGF

transforming growth factor

REFERENCES

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, De Ferranti S, Després JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, MacKey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):447–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sandison AT. Degenerative vascular disease in the Egyptian mummy. Med Hist. 1962;6:77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmerman M The paleophysiology of the cardiovascular system. Texas Heart Inst J. 1993;20:252–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rokitansky K A manual of pathological anatomy. Philadelphia: Blanchard & Lee; 1855. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Virchow R Cellular pathology as based upon physiological and pathological histology. Philadelphia: J B Lippincott; 1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayerl C, Lukasser M, Sedivy R. Atherosclerosis research from past to present—on the track of two pathologists with opposing views, Carl von Rokitansky and Rudolf Virchow. Virchows Archiv. 2006:96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.A W. Ueber den Gehalt normaler und atheromatoeser Aorten an Cholesterol and Cholesterinestere. Zeitschrift Physiol Chem. 1910;67:174–76. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anitschkow N and Chalatow S. Ueber experimentelle Cholesterinsteatose und ihre Bedeutung für die Entstehung einiger pathologischer Prozesse. Zentralbl Allg Pathol. 1913;(24):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansson GK, Jonasson L. The discovery of cellular immunity in the atherosclerotic plaque. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(11):1714–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonasson L, Holm J, Skalli O, Gabbiani G, Hansson GK. Expression of class 11 transplantation antigen muscle cells in human atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 1985;76(1):125–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jonasson L, Holm J, Skalli O, Bondjers G, Hansson GK. Regional accumulations of T-cells, macrophages, and smooth muscle cells in the human atherosclerotic plaque. Atherosclerosis. 1986;6:131–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu Q, Oberhuber G, Gruschwitz M, Wick G. Immunology of atherosclerosis: Cellular composition and major histocompatibility complex class II antigen expression in aortic intima, fatty streaks, and atherosclerotic plaques in young and aged human specimens. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;56(3):344–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinn MT, Parthasarathy S, Fong LG, Steinberg D. Oxidatively modified low density lipoproteins: a potential role in recruitment and retention of monocyte/macrophages during atherogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(9):2995–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palinski W, Hörkkö S, Miller E, Steinbrecher UP, Powell HC, Curtiss LK, Witztum JL. Cloning of monoclonal autoantibodies to epitopes of oxidized lipoproteins from apolipoprotein E-deficient mice: demonstration of epitopes of oxidized low density lipoprotein in human plasma. J Clin Invest. 1996;98(3):800–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snapper CM, Mond JJ. A model for induction of T-cell-independent humoral immunity in response to polysaccharide antigens. J Immunol. 1996; 157(6): 2229–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Binder CJ, Hörkkö S, Dewan A, Chang M-K, Kieu EP, Goodyear CS, Shaw PX, Palinski W, Witztum JL, Silverman GJ. Pneumococcal vaccination decreases atherosclerotic lesion formation: molecular mimicry between Streptococcus pneumoniae and oxidized LDL. Nat Med. 2003;9(6):736–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stemme S, Faber B, Holmt J, Wiklund O, Witztuml JL, Hansson GK, Steinberg D. T lymphocytes from human atherosclerotic plaques recognize oxidized low density lipoprotein. Med Sci. 1995;92(9):3893–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palinski W, Rosenfeld ME, Ylä-Herttuala S, Gurtner GC, Socher SS, Butler SW, Parthasarathy S, Carew TE, Steinberg D, Witztum JL. Low density lipoprotein undergoes oxidative modification in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(4):1372–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palinski W, Witztum JL. Immune responses to oxidative neoepitopes on LDL and phospholipids modulate the development of atherosclerosis. J Intern Med. 2000;247(3):371–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hermansson A, Ketelhuth DFJ, Strodthoff D, Wurm M, Hansson EM, Nicoletti A, Paulsson-Beme G, Hansson GK. Inhibition of T-cell response to native low-density lipoprotein reduces atherosclerosis. J Exp Med. 2010;207(5):1081–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dwivedi A, Änggård EE, Carrier MJ. Oxidized LDL-mediated monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells does not involve NFκB . Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284(1):239–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein JL, Ho YK, Basu SK, Brown MS. Binding site on macrophages that mediates uptake and degradation of acetylated low density lipoprotein, producing massive cholesterol deposition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76(1):333–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zani IA, Stephen SL, Mughal NA, Russell D, Homer-Vanniasinkam S, Wheatcroft SB, Ponnambalam S. Scavenger receptor structure and function in health and disease. Cells. 2015;4(2):178–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krieger M Molecular flypaper and atherosclerosis: structure of the macrophage scavenger receptor. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17(4):141–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Endemann G, Stanton LW, Madden KS, Bryant CM, White RT, Protter AA. CD36 is a receptor for oxidized low density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(16):11811–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Febbraio M, Podrez EA, Smith JD, Hajjar DP, Hazen SL, Hoff HF, Sharma K, Silverstein RL. Targeted disruption of the class B scavenger receptor CD36 protects against atherosclerotic lesion development in mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(8):1049–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tontonoz P, Nagy L, Alvarez JGA, Thomazy VA, Evans RM. PPARγ promotes monocyte/macrophage differentiation and uptake of oxidized LDL. Cell. 1998;93(2): 241–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagy L, Tontonoz P, Alvarez JGA, Chen H, Evans RM. Oxidized LDL regulates macrophage gene expression through ligand activation of PPARγ. Cell. 1998;93(2): 229–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuchibhotla S, Vanegas D, Kennedy DJ, Guy E, Nimako G, Morton RE, Febbraio M. Absence of CD36 protects against atherosclerosis in ApoE knock-out mice with no additional protection provided by absence of scavenger receptor A I/II. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;78(1):185–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marleau S EP 80317, a ligand of the CD36 scavenger receptor, protects apolipoprotein E-deficient mice from developing atherosclerotic lesions. FASEB J. 2005;19(13):1869–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Febbraio M, Guy E, Silverstein RL. Stem Cell transplantation reveals that absence of macrophage CD36 is protective against atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(12):2333–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chávez-Sanchez L, Madrid-Miller A, Chávez-Rueda K, Legorreta-Haquet MV, Tesoro-Cruz E, Blanco-Favela F. Activation of TLR2 and TLR4 by minimally modified low-density lipoprotein in human macrophages and monocytes triggers the inflammatory response. Humimmunol. 2010;71(8):737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller YI, Viriyakosol S, Worrall DS, Boullier A, Butler S, Witztum JL. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent and -independent cytokine secretion induced by minimally oxidized low-density lipoprotein in macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(6):1213–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie CH, Ng HP, Nagarajan S. OxLDL or TLR2-induced cytokine response is enhanced by oxLDL-independent novel domain on mouse CD36. Immunol Lett. 2011;137(1–2):15–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheedy FJ, Grebe A, Rayner KJ, Kalantari P, Ramkhelawon B, Carpenter SB, Becker CE, Ediriweera HN, Mullick AE, Golenbock DT, Stuart LM. CD36 coordinates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by facilitating intracellular nucleation of soluble ligands into particulate ligands in sterile inflammation. Nature Immunol. 2013. August;14(8):812 DOI: 10.1038/ni.2639.CD36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140(6):821–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hise AG, Tomalka J, Ganesan S, Patel K, Hall BA, Brown GD, Fitzgerald KA. Article an essential role for the nlrp3 inflammasome in host defense against the human fungal pathogen candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5(5):487–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Body-malapel M, Amer A, Park J, Kanneganti T, Nesrin O, Franchi L, Whitfield J, Barchet W, Colonna M, Vandenabeele P, Bertin J, Coyle A, Grant EP, Akira S, Nu G. Bacterial RNA and small antiviral compounds. 2006;440(7081):233–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG, Schnurr M, Espevik T, Lien E, Fitzgerald KA, Abela GS, Franchi L, Nun G. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464(7293):1357–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saad AF, Virella G, Chassereau C, Boackle RJ, Lopes-Virella MF. OxLDL immune complexes activate complement and induce cytokine production by MonoMac 6 cells and human macrophages. J Lipid Res. 2006;47(9):1975–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lopes-Virella MF, Virella G, Orchard TJ, Koskinen S, Evans RW, Becker DJ, Forrest KY. Antibodies to oxidized LDL and LDL-containing immune complexes as risk factors for coronary artery disease in diabetes mellitus. Clin Immunol. 1999;90(2): 165–72. D0I: 10.1006/clim.1998.4631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lopes-Virella MF, Virella G. Pathogenic role of modified LDL antibodies and immune complexes in atherosclerosis. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2013;20(10):743–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rhoads JP, Lukens JR, Wilhelm AJ, Moore L, Mendez- fernandez Y, Major AS. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein immune complex priming of the nlrp3 inflammasome involves tlr and fc γ r cooperation and is dependent on card9. J Immunol. 2017. January 27:1601563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erbel C, Sato K, Meyer FB, Kopecky SL, Frye RL, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Functional profile of activated dendritic cells in unstable atherosclerotic plaque. Basic Res Cardiol. 2007;102(2):123–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yilmaz A, Lochno M, Traeg F, Cicha I, Reiss C, Stumpf C, Raaz D, Anger T, Amann K, Probst T, Ludwig J, Daniel WG, Garlichs CD. Emergence of dendritic cells in rupture-prone regions of vulnerable carotid plaques. Atherosclerosis. 2004;176(1):101–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang Y, Ronnelid J, Frostegard J. Oxidized LDL induces enhanced antibody formation and mhc class ii–dependent ifn-γ production in lymphocytes from healthy individuals. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:1577–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perrin-Cocon L, Coutant F, Agaugué S, Deforges S, André P, Lotteau V. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein promotes mature dendritic cell transition from differentiating monocyte. J Immunol. 2001;167(7):3785–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daugherty A, Puré E, Delfel-Butteiger D, Chen S, Leferovich J, Roselaar SE, Rader DJ. The effects of total lymphocyte deficiency on the extent of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E−/− mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(6): 1575–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dansky HM, Charlton SA, Harper MM, Smith JD. T and B lymphocytes play a minor role in atherosclerotic plaque formation in the apolipoprotein E-deficient mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(9):4642–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou X, Nicoletti A, Elhage R, Hansson GK. Transfer of CD4+ T-cells aggravates atherosclerosis in immunodeficient apolipoprotein e knockout mice. Circulation. 2000;102(24):2919–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Freigang S, Hörkkö S, Miller E, Witztum JL, Palinski W. Immunization of LDL receptor-deficient mice with homologous malondialdehyde-modified and native LDL reduces progression of atherosclerosis by mechanisms other than induction of high titers of antibodies to oxidative neoepitopes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18(12):1972–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fredrikson GN, Söderberg I, Lindholm M, Dimayuga P, Chyu KY, Shah PK, Nilsson J. Inhibition of atherosclerosis in apoE-null mice by immunization with apoB-100 peptide sequences. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(5):879–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Habets KLL, Van Puijvelde GHM, Van Duivenvoorde LM, Van Wanrooij EJA, De Vos P, Tervaert JWC, Van Berkel TJC, Toes REM, Kuiper J. Vaccination using oxidized low-density lipoprotein-pulsed dendritic cells reduces atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85(3):622–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hjerpe C, Johansson D, Hermansson A, Hansson GK, Zhou X. Dendritic cells pulsed with malondialdehyde modified low density lipoprotein aggravate atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− mice. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209(2):436–41. D0I: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun J, Hartvigsen K, Chou MY, Zhang Y, Sukhova GK, Zhang J, Lopez-Ilasaca M, Diehl CJ, Yakov N, Harats D, George J, Witztum JL, Libby P, Ploegh H, Shi GP. Deficiency of antigen-presenting cell invariant chain reduces atherosclerosis in mice. Circulation. 2010;122(8):808–0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lievens D, Habets KL, Robertson AK, Laouar Y, Winkels H, Rademakers T, Beckers L, Wijnands E, Boon L, Mosaheb M, Ait-Oufella H, Mallat Z, Flavell RA, Rudling M, Binder CJ, Gerdes N, Biessen EAL, Weber C, Daemen MJAP, Kuiper J, Lutgens E Abrogated transforming growth factor beta receptor II (TGF-β RII) signalling in dendritic cells promotes immune reactivity of T-cells resulting in enhanced atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(48):3717–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Subramanian M, Thorp E, Hansson GK, Tabas I. Treg-mediated suppression of atherosclerosis requires MYD88 signaling in DCs. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(1):179–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lim H, Kim YU, Sun H, Lee JH, Reynolds JM, Hanabuchi S, Wu H, Teng BB, Chung Y. Proatherogenic conditions promote autoimmune T helper 17 cell responses in vivo. Immunity. 2014;40(1):153–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tse K, Gonen A, Sidney J, Ouyang H, Witztum JL, Sette A, Tse H, Ley K. Atheroprotective vaccination with MHC-II restricted peptides from ApoB-100. Front Immunol. 2013;4(December):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koch AE, Haines GK, Rizzo RJ, Radosevich JA, Pope RM, Robinson PG, Pearce WH. Human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Immunophenotypic analysis suggesting an immune-mediated response. Am J Pathol. 1990; 137(5):1199–213. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cochain C, Koch M, Chaudhari SM, Busch M, Pelisek J, Boon L, Zernecke A. CD8 + T-cells regulate monopoiesis and circulating Ly6C high monocyte levels in atherosclerosis in mice: novelty and significance. Circ Res. 2015;117(3):244–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ghio M, Fabbi P, Contini P, Fedele M, Brunelli C, Indiveri F, Barsotti A. OxLDL- and HSP-60 antigen-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes are detectable in the peripheral blood of patients suffering from coronary artery disease. Clin Exp Med. 2013;13(4):251–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chyu KY, Zhao X, Dimayuga PC, Zhou J, Li X, Yano J, Lio WM, Chan LF, Kirzner J, Trinidad P, Cercek B, Shah PK. CD8+T-cells mediate the athero-protective effect of immunization with an ApoB-100 peptide. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Palinski W, Miller E, Witztum JL. Immunization of low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-deficient rabbits with homologous malondialdehyde-modified LDL reduces atherogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(3): 821–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nilsson J, Calara F, Regnstrom J, Hultgardh-Nilsson A, Ameli S, Cercek B, Shah PK. Immunization with homologous oxidized low density lipoprotein reduces neointimal formation after balloon injury in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30(7):1886–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.George J, Afek A, Gilburd B, Levkovitz H, Shaish A, Goldberg I, Kopolovic Y, Wick G, Shoenfeld Y, Harats D. Hyperimmunization of apo-E-deficient mice with homologous malondialdehyde low-density lipoprotein suppresses early atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis. 1998;138(1):147–52. D0I: 10.1016/S00219150(98)00015-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Caligiuri G, Nicoletti A, Poirierand B, Hansson GK. Protective immunity against atherosclerosis carried by B-cells of hypercholesterolemic mice. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(6):745–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Major AS, Fazio S, Linton MF. B-lymphocyte deficiency increases atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-null mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22(11):1892–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ait-Oufella H, Herbin O, Bouaziz J-D, Binder CJ, Uyttenhove C, Laurans L, Taleb S, Van Vre E, Esposito B, Vilar J, Sirvent J, Van Snick J, Tedgui A, Tedder TF, Mallat Z. B-cell depletion reduces the development of atherosclerosis in mice. J Exp Med. 2010;207(8): 1579–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kyaw T, Tay C, Khan A, Dumouchel V, Cao A, To K, Kehry M, Dunn R, Agrotis A, Tipping P, Bobik A, Toh B-H. Conventional B2 B-cell depletion ameliorates whereas its adoptive transfer aggravates atherosclerosis. J Immunol. 2010;185(7):4410–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kyaw T, Tay C, Hosseini H, Kanellakis P, Gadowski T, MacKay F, Tipping P, Bobik A, Toh BH. Depletion of b2 but not bla B-cells in baff receptor-deficient apoe −/− mice attenuates atherosclerosis by potently ameliorating arterial inflammation. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tay C, Liu Y-H, Kanellakis P, Kallies A, Li Y, Cao A, Hosseini H, Tipping P, Toh B- H, Bobik A, Kyaw T. Follicular B-cells promote atherosclerosis via T-cell–mediated differentiation into plasma cells and secreting pathogenic immunoglobulin G. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018. May;38(5):e71–e84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sage AP, Nus M, Bagchi Chakraborty J, Tsiantoulas D, Newland SA, Finigan AJ, Masters L, Binder CJ, Mallat Z. X-box binding protein-1 dependent plasma cell responses limit the development of atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2017;121(3):270–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kyaw T, Tay C, Krishnamurthi S, Kanellakis P, Agrotis A, Tipping P, Bobik A, Toh BH. B1a B lymphocytes are atheroprotective by secreting natural IgM that increases IgM deposits and reduces necrotic cores in atherosclerotic lesions. Circ Res. 2011;109(8):830–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rosenfeld SM, Perry HM, Gonen A, Prohaska TA, Srikakulapu P, Grewal S, Das D, McSkimming C, Taylor AM, Tsimikas S, Bender TP, Witztum JL, McNamara CA. B-1B-cells secrete atheroprotective IgM and attenuate atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2015;117(3):e28–e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Doran AC, Lipinski MJ, Oldham SN, Garmey JC, Campbell KA, Skaflen MD, Cutchins A, Lee DJ, Glover DK, Kelly KA, Galkina EV, Ley K, Witztum JL, Tsimikas S, Bender TP, McNamara CA. B-cell aortic homing and atheroprotection depend on Id3. Circ Res. 2012. January 6;110(1):e1–e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hörkkö S, Bird DA, Miller E, Itabe H, Leitinger N, Subbanagounder G, Berliner JA, Friedman P, Dennis EA, Curtiss LK, Palinski W, Witztum JL. Monoclonal autoantibodies specific for oxidized phospholipids or oxidized phospholipid-protein adducts inhibit macrophage uptake of oxidized low-density lipoproteins. J Clin Invest. 1999;103(1):117–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Salonen JT, Korpela H, Salonen R, Nyyssonen K, Yla-Herttuala S, Yamamoto R, Butler S, Palinski W, Witztum JL. Autoantibody against oxidised LDL and progression of carotid atherosclerosis. Lancet. 1992;339(8798):883–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shaw PX, Hörkkö S, Chang MK, Curtiss LK, Palinski W, Silverman GJ, Witztum JL. Natural antibodies with the T15 idiotype may act in atherosclerosis, apoptotic clearance, and protective immunity. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(12):1731–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]