Abstract

Purpose:

Physical activity (PA) is known to improve cognitive and brain function, but debate continues regarding the consistency and magnitude of its effects, populations and cognitive domains most affected, and parameters necessary to achieve the greatest improvements (e.g., dose).

Methods:

In this umbrella review conducted in part for the 2018 Health and Human Services Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans Advisory Committee, we examined whether PA interventions enhance cognitive and brain outcomes across the lifespan, as well as in populations experiencing cognitive dysfunction (e.g., schizophrenia). Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and pooled analyses were used. We further examined whether engaging in greater amounts of PA is associated with a reduced risk of developing cognitive impairment and dementia in late adulthood.

Results:

Moderate evidence from randomized controlled trials indicates an association between moderate-to-vigorous intensity PA and improvements in cognition, including performance on academic achievement and neuropsychological tests, such as those measuring processing speed, memory, and executive function. Strong evidence demonstrates that acute bouts of moderate-to-vigorous PA have transient benefits for cognition during the post-recovery period following exercise. Strong evidence demonstrates that greater amounts of PA are associated with a reduced risk of developing cognitive impairment, including Alzheimer’s disease. The strength of the findings varies across the lifespan and in individuals with medical conditions influencing cognition.

Conclusions:

There is moderate-to-strong support that PA benefits cognitive functioning during early and late periods of the lifespan and in certain populations characterized by cognitive deficits.

Keywords: acute exercise, academic achievement, brain, cognitive function, dementia, fitness

Introduction:

Scientific, educational, and public health communities have demonstrated immense interest in investigating approaches that might enhance cognitive and brain function throughout the lifespan. Indeed, improvements in cognitive and brain health may have profound consequences for shaping quality of life, educational and career opportunities, and decision-making abilities. Physical activity (PA), defined as bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure (1), has emerged as one of the most promising methods for positively influencing cognitive function across the lifespan and reducing the risk of age-related cognitive decline. The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee (PAGAC) reviewed evidence on these effects to inform federal policy.

The possibility that PA might favorably influence cognitive and brain health is based upon the fundamental neurobiological principle that cellular and molecular events in the brain are amenable to modification by environmental enrichment. The pioneering work on environmental enrichment demonstrated that rodents housed in impoverished cages have a substantially different neurobiology than rodents housed in enriched cages and that this neurobiological effect translated to enhanced learning and memory (2, 3). Access to a running wheel was shown to be a critical feature of an enriched environment (4).

Demonstration of the positive effects of PA on the brain in rodents has guided questions about its potential for positive effects in humans. Indeed, studies in humans have found associations between PA and cognitive and brain outcomes across the lifespan (5). However, several reviews and meta-analyses of this literature have concluded that the impact PA on cognitive and brain health remains unclear because of inconsistencies in the parameters of PA used across studies, the ways in which cognition was measured, the assessment of moderators and mechanisms that could explain heterogeneity of the results, and quality of the study designs (5). More recent reviews and meta-analyses have found that PA training results in modest improvements in cognitive and brain outcomes across the lifespan, but many of these reviews have not closely interrogated quality (6, 7).

The 2018 PAGAC reviewed the scientific literature of this field, and the results from that analysis are partially described herein. We aimed to address several questions. First, by integrating the literature across ages and health conditions and providing a ‘bird’s eye’ perspective to the field, can we determine if there is sufficient evidence that PA positively influences cognitive and brain outcomes in humans? Second, at which age or in which population is the scientific literature the strongest and in which the weakest? Third, are there cognitive domains that are especially responsive to PA? Fourth, is PA associated with a reduced risk of cognitive impairment? Finally, is there sufficient evidence to indicate which parameters of PA may be important for modulation of cognitive and brain health?

Methods:

The methods used to conduct the reviews that informed the 2018 PAGAC Scientific Report have been described in detail elsewhere (8).

The searches were conducted in electronic databases (PubMed®, CINAHL, and Cochrane) and supplemented by additional articles identified by experts. The inclusion criteria were pre-defined, and studies were considered potentially eligible if they were systematic reviews (SRs), meta-analyses, or pooled analyses published in English from 2003 to February 2017. Studies published in 2017 or 2018 (i.e., after data extraction for the PAGAC report) are also included as the search was updated for this manuscript (N = 44). For the sake of this review, we used a relatively broad definition of PA based on that provided by Casperson et al. (1) to include play and recess activities in children, structured exercise programs for adults, and experimental manipulations of acute bouts of exercise. All types and intensities of PA, including free-living activities and play were included in the search as interventions/exposures. Although not a form of PA, the term ‘physical fitness’ was also included in the search and, if relevant, these studies were described separately. Studies of non-ambulatory people, hospitalized patients, or animals were excluded. The full search strategy is available at https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/report/supplementary_material/pdf/Brain_Health_Q1_Cognition_Evidence_Portfolio.pdf.

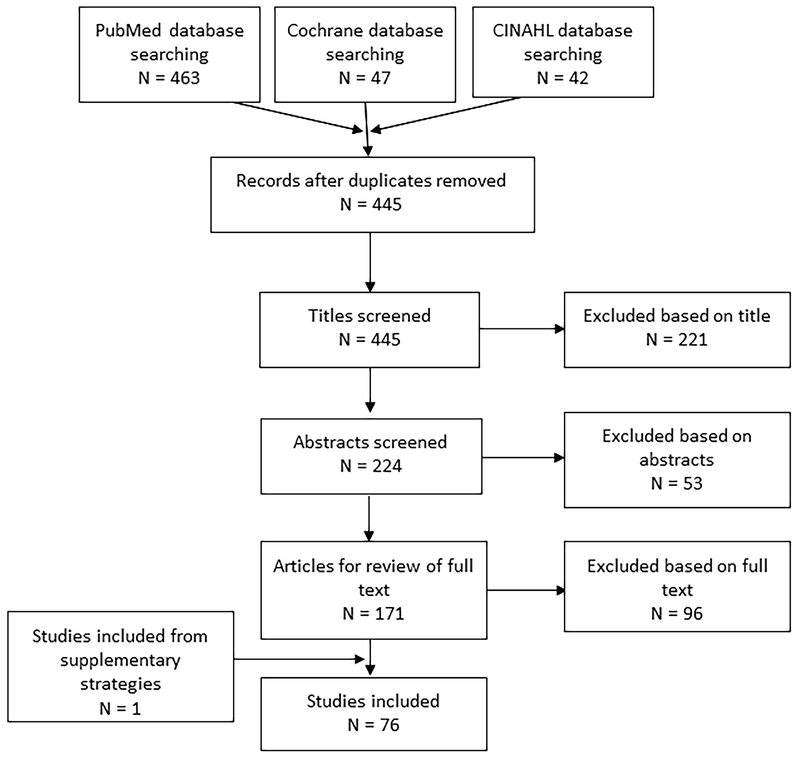

Titles, abstracts, and full-text articles were independently screened by two reviewers. Disagreement between reviewers was resolved by discussion or by a third person. The protocol for this review was registered at PROSPERO #CRD42018095774. Figure 1 shows the search strategy and study selection process.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of search strategy and study selection

A total of 76 articles (35 meta-analyses; 41 SRs) were identified that examined effects of RCTs and prospective longitudinal studies with cognitive outcomes. These reviews included results from younger (18-50 years; N=5) (9–13) adults, older adults (N =7) (6, 14–19), children (N= 13) (20–32), and adolescents (N=6) (33–38), as well as populations with impaired cognition, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (N=3) (39–41), mild cognitive impairment or dementia (N=13) (42–54), multiple sclerosis (N=1) (55), Parkinson’s disease (N=2) (56, 57), schizophrenia (N=1) (58), HIV (N=1) (59), Type 2 Diabetes (N=2) (60, 61), cancer (N=2) (62, 63), and stroke (N=2) (53, 64). We also included articles on acute exercise and cognitive outcomes (N=4) (65–68), sedentary behavior and cognitive outcomes (N=1) (69), and biomarkers of brain health (N=9) (70–78). We further included one meta-analysis examining resistance training and episodic memory (79) and 3 articles on interval training and exergaming (80–82). We summarized the outcomes of our review with the following “grades”: (1) Grade Not Assignable, (2) Limited, (3) Moderate, and (4) Strong (see (8) for an in-depth description and the defining characteristics of these categories).

Results:

Table 1 presents a summary of the results in each of the following domains.

Table 1.

Committee-assigned grades for the effects of physical activity on various ages and clinical outcomes.

| Population or Measure | Outcome | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| Children <6 yrs | Insufficient evidence to determine the effects of moderate-to-vigorous PA on cognition | Not Assignable |

| Children 6-13 yrs | Both acute and chronic moderate-to-vigorous PA interventions improve brain structure and function, as well as cognition, and academic outcomes | Moderate |

| Children 14-18 yrs | Limited evidence to determine the effects of moderate-to-vigorous PA on cognition | Limited |

| Young and middle Aged Adults 18-50 yrs | Insufficient evidence to determine the effects of moderate-to-vigorous PA on cognition | Not Assignable |

| Older Adults >50 yrs | Both acute and long-term moderate-to-vigorous PA interventions improve brain structure and function, as well as cognition | Moderate |

| Adults with Dementia | Evidence suggests that PA may improve cognitive function | Moderate |

| Risk of Dementia and Cognitive Impairment | Greater amounts of PA reduce the risk for cognitive impairment | Strong |

| Other Clinical Disorders (i.e., ADHD, schizophrenia, MS, Parkinson’s, stroke) | Evidence that moderate-to-vigorous PA has beneficial effects on cognition in individuals with diseases or disorders that impair cognition | Moderate |

| Biomarkers of Brain Health | Moderate-to-vigorous PA positively influences biomarkers including MRI-based measures of function, brain volume, and white matter | Moderate |

| Acute Bouts | Short, acute bouts of moderate-to-vigorous PA transiently improves cognition during the post-recovery period | Strong |

| OVERALL | There is a consistent association between chronic MVPA and improved cognition including performance on academic achievement tests, neuropsychological tests, risk of dementia. Effects are demonstrated across a gradient of normal to impaired cognitive health status | Moderate |

Chronic PA behavior

In the following subsections, we refer to chronic PA behavior as PA that is repeated and lasts longer than a single session or episode. Thus, acute PA research reflects the immediate (transient) response to a single bout of PA, while chronic PA reflects a true change in an individual’s baseline (i.e., a prolonged/permanent shift in activity). In the case of chronic PA, the change is not as tightly coupled in time to the last bout of PA. The effects of single-session, or acute, PA are discussed in a separate section below. Most of the work on chronic PA includes studies that examine PA behavior and engagement over a span of weeks, months, or years.

Children ≤6 years:

In preschool aged children, little published research has examined the relationship between regular PA and cognitive outcomes. In fact, only two SRs have appeared to date (24, 32). Carson and colleagues (24) reviewed seven observational and experimental studies of PA in typically developing children and reported that six of the studies yielded a beneficial effect of greater PA on at least one cognitive outcome, with the most notable findings observed for executive function (67% of the outcomes assessed) and language (60% of the outcomes assessed). No studies demonstrated that PA was related to poorer cognition. However, the authors rated six of the seven studies as having weak experimental quality and a high risk of reporting bias using PRISMA guidelines. Further, Zeng et al. (32) reviewed five RCTs of PA on cognitive development in children aged 4-6 years. Four of the five studies (80%) observed a positive effect of PA on attention, memory, language, and academic achievement. Similarly, they concluded that there is only preliminary evidence to support a positive effect of PA on cognition during early childhood. Due to insufficient evidence, the subcommittee decided a grade was Not Assignable regarding the effect of PA on cognitive development in the early, pre-school years.

Children 6 to 13 years:

The greatest wealth of evidence for an effect of PA on cognitive outcomes in children was found for preadolescents. Several SRs and meta-analyses report beneficial effects (using SR criteria, Cohen’s d, or Hedges’ g) of PA on cognitive and academic outcomes (20, 21, 23, 25, 26, 29–31, 35, 36). Specifically, consistent benefits of PA were observed for executive function (21, 23, 26), attention (25), and academic achievement (20, 26), including academic behaviors (e.g., time on task) (30). Across the included articles, there were consistent findings indicating a small-to-moderate effect (effect sizes = 0.13-0.30) of PA on cognitive and academic outcomes. Such findings were observed across a number of cognitive domains (and assessments within domains), highlighting the robustness of this relationship despite the heterogeneity of approaches for investigating the influence of PA on cognition.

Additional support for the relationship for PA on cognition in preadolescence stemmed from the use of neuroimaging tools in this population. Two SRs (23, 26) have described differences in brain structure and function as a result of PA in RCTs, with additional support from cross-sectional comparisons of higher and lower fit groups of preadolescents. Briefly, findings have demonstrated differences in brain structure including greater integrity in specific white matter tracts following PA interventions (23, 26). Functional brain changes resulting from PA interventions have also been noted in preadolescent children. Such studies have indicated PA intervention-induced benefits to the neuroelectric system as well as changes in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) signals (23, 26). Collectively, there is Moderate evidence that PA is beneficial to cognition and brain structure and function during preadolescence.

Children 14 to 18 years:

Relative to preadolescence, significantly fewer reports (i.e., 6 SRs and meta-analyses) have been published in adolescent children. In adolescents, there were fewer rigorous experimental studies with control groups, studies with well-described parameters and definitions of PA, and well-described measures of cognitive function or academic achievement. Despite these limitations, a recent meta-analysis reported a positive effect (Cohen’s d=0.37) for PA on academic outcomes across 10 studies (38). In addition, two SRs (both with ~20 studies) focused on PA and cognitive outcomes. Esteban-Cornejo et al. (33) observed mixed results, such that 70% of the studies observed a positive relationship of PA (broadly defined as physical education, sport, athletic participation and exercise behavior) with cognitive or academic outcomes, 20% observed no relationship, and 10% observed a negative relationship. Similarly, Ruiz-Ariza et al. (37) observed a generally beneficial relationship of several metrics of fitness with cognitive outcomes. Given the limited number of rigorous experimental studies with randomized designs, these findings should be considered preliminary. Four new reports emerged in 2017 and 2018 after the PAGAC search was completed (34–37), and collectively these reports have demonstrated consistency in their conclusions of a positive association between PA and cognition in adolescence. However, given the heterogeneity of findings in this age group, we determined there is Limited, but promising evidence for positive effects of PA on cognition in adolescent children. Note that this grade was changed from the 2018 PAGAC Report, where there was insufficient evidence available at the time for even a limited grade.

Young and Middle-Aged Adults:

Relative to studies of children and older adults, there is a dearth of SRs and meta-analyses on the relationship of PA and cognition in young and middle-aged adults (18-50 yrs). Several reports have investigated PA on cognition across the adult lifespan; however, the samples were weighted toward older adults (>60 years) or included individuals with various clinical disorders (11, 12). Other reports in middle aged adults only included 1-2 studies aimed at chronic, or long-term, PA participation, with the majority of studies focused on acute PA effects (79). Of the few studies reported, the findings were mixed for the effects of moderate-to-vigorous PA on cognition, indicating the need for additional research during young and middle adulthood. We determined that a grade was Not Assignable regarding the effects of PA on cognition and brain outcomes in this age range.

Older Adults (>50):

The most significant body of research (i.e., 7 SRs and meta-analyses) examining the effects of PA on cognitive function has been conducted in older adults, which the PAGAC defined at those over the age of 50. This work indicates that there is Moderate evidence for an effect of long-term moderate-to-vigorous PA on cognitive outcomes in adults aged 50 years and older. In cognitively-normal older adults, effect sizes (Hedges’ g) ranged from non-significant (15) to 0.20 (18) to 0.48 (6) or higher (14) in favor of PA. Effect sizes were greatest for measures of executive function (6), global cognition (18), and attention (15). In one meta-analysis of 39 RCTs, PA training improved executive function, episodic memory, visuospatial function, word fluency, processing speed, and global cognitive function (14). Some of these effects were large (Hedges’ g=2.06 for aerobic training effects on executive functions), but were moderated by the mode of activity with larger effect sizes for aerobic training compared to resistance or multi-modal (i.e., resistance and aerobic) interventions. Other studies have also reported effects of resistance training. For example, measures of reasoning were significantly improved across 25 RCTs, but this effect was specific to resistance exercise (15), while others reported the largest effect sizes for combined resistance and aerobic training (6, 19). Other modes of activity like exergaming (e.g., Wii Fit) might also improve cognitive function (17). In addition, for executive functions, larger effect sizes have been reported for studies with a greater percentage of women, suggesting sex is an important moderator of the effect of PA on cognition (6, 14). In another meta-analysis of 39 RCTs examining the effects of PA on cognitive function in individuals over the age of 50, PA improved cognition with an effect size of 0.29 (16). In sum, despite heterogeneity across studies, the majority of SRs and meta-analyses reported small-to-moderate sized effects of RCTs on cognitive performance in older adults, which were moderated by both sex and the cognitive domain assessed.

Neuroimaging research has provided another level and type of support for the effects of PA in older adults. These results have been summarized across several reviews (83). In one meta-analysis of 14 studies, nine of which were in older adults, aerobic exercise increased right and left anterior hippocampal volumes (71, 76). Yet, despite these promising results, few large-scale studies with sufficient sample sizes have examined the effects of PA interventions on hippocampal volume in older adults, leading to ambiguity about the long-term effects (75). Other studies have reported positive effects on other brain biomarkers of morphology and function (71, 77, 78), while others are more equivocal (72).

In summary, there are promising effects of PA on cognitive and brain outcomes in older adults, but more research is needed to disambiguate the age-ranges most affected, sex differences, dose-response parameters necessary to optimize PA effects, and brain biomarkers for better understanding pathways leading to improvements in cognition. These remaining open questions, led us to grade the evidence as Moderate for this age range.

Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia:

The evidence for this question was based on prospective observational research designs that followed people over periods of time ranging from 1 to 12 years (i.e., 2 SR and meta-analyses). There is Strong evidence indicating that greater amounts of PA is associated with a reduced risk of cognitive decline (51) and dementia, including AD (42). In this literature prospective observational studies are conducted on cognitively normal individuals who are then subsequently followed over time to determine whether PA is associated with risk for developing cognitive impairment. For example, a meta-analysis of 15 prospective studies ranging from 1-12 years in duration with more than 33,000 participants found that greater amounts of PA were associated with a 38% reduced risk of cognitive decline (51). Another meta-analysis of 10 prospective studies with more than 20,000 participants reported that greater amounts of PA were associated with a 40% reduced risk of developing AD (42). One additional SR published after the PAGAC search was completed examined the effects of PA interventions (of any type) lasting at least 6 months on delaying cognitive impairment in currently undiagnosed individuals (44). The authors concluded that there was insufficient evidence that PA could be used for dementia prevention. However, heterogeneous nature of the interventions (e.g., with many including both PA and diet components) and cognitive test measures, small and underpowered studies, and inability to assess the clinical significance of cognitive test outcomes were common limitations of the included studies.

PA is also a possible approach for managing the symptoms of dementia, indicating that PA interventions may help to improve cognition in individuals with a clinical dementia diagnosis, including AD (45, 47, 49, 50, 52, 84). For example, one meta-analysis of 18 RCTs from 802 dementia patients reported an overall standardized mean difference of 0.42; this effect was also significant for individuals with AD (N=8 studies) or in studies that combined AD and non-AD dementias (N=7) (47). These positive effects were found for interventions that were both high-frequency and low-frequency PA (defined as an average of 213 minutes per week or 93 minutes per week, respectively), although it is important to note that consensus in the literature has not been reached regarding the effects of RCTs of PA on reducing the risk for developing cognitive impairment many years later (43, 44). Despite these findings, there is considerable heterogeneity in the cognitive assessment methods, description of the PA interventions, and a moderate risk for bias noted across studies.

In sum, given the significant heterogeneity in study design, lack of appropriate reporting of important PA parameters, and significant variability in cognitive tests employed, there is moderate evidence that PA interventions improve cognitive performance in populations with a current diagnosis of dementia. However, there is strong evidence from observational prospective studies that engaging in greater amounts of PA is associated with a reduced risk of developing cognitive impairment.

Other Clinical Populations:

There is Moderate evidence, largely based on RCTs, indicating that PA improves cognitive function in individuals with diseases or disorders that impair cognitive function including ADHD (39), schizophrenia (58), multiple sclerosis (MS) (55), Parkinson’s disease (56), and stroke (53, 64). Results in MS are conflicting, but executive function, learning, memory, and processing speed show the largest effects (55). Individuals with Parkinson’s disease show improvements in cognition following PA (56, 57), with the largest effect sizes in general cognitive function and executive function. In schizophrenia, moderate-to-vigorous PA interventions improve global cognition, working memory, and attention, with an average Hedges’ g of 0.43 (58). Further, increases in brain volume and connectivity and elevated levels of serum BDNF are observed following 8 weeks to 6 months of PA in individuals with schizophrenia (70). In patients with both acute and chronic stroke, PA improves global cognition, attention, memory, and visuospatial abilities (53, 64).

In studies examining effects of PA in ADHD, the effect sizes (Hedges’ g) ranged from 0.18 to 0.77 in favor of PA improving cognitive performance (39–41). The cognitive domains most commonly affected included attention and executive function (e.g., inhibition, impulsivity) (39, 41). Such findings have been extended to children with social, emotional, and behavioral disabilities (22). In autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Tan et al. (41) reported a small-to-moderate effect (Hedges’ g = 0.47) for improvement in some aspects of cognition. However, the meta-analysis included children with ASD, ADHD, or both disorders (overall Hedges’ g = 0.24) and, as such, it is difficult to interpret effects of PA on ASD alone (41).

The study of PA as an adjuvant treatment for cancer-related cognitive deficits is in its early stages (62, 63). Myers et al., (63) reported that 7 of 11 RCTs indicated improved cognitive function due to PA (aerobic, resistance, mindfulness-based exercise, or a combination of PA modes). However, only two of the studies used objective measures of cognition (63). The remaining trials used subjective cognitive outcomes (e.g., ratings of cognitive slips or failures in daily activities). A similar conclusion was reached by Furmaniak et al. (62).

There are also promising, but preliminary results, showing that cognition in individuals with HIV (59) or Type 2 diabetes (60, 61) was improved by PA. For example, a recent SR of 16 studies in HIV suggests that PA may influence cognitive health across a variety of self-report, executive function, memory, and processing speed measures (59). Similar benefits have been suggested for Type 2 diabetes (60); but another review failed to establish a benefit of PA on cognitive health in this population (61).

Dose-response effects of PA:

Unfortunately, little is known about the dose of PA – volume, duration, frequency, or intensity – needed to improve cognitive function. One meta-analysis in older adults (6) reported that larger effects were observed in RCTs in which PA bouts lasted 46-60 minutes (compared to bout lasting 15-30 minutes and 31-45 minutes) and in interventions lasting for at least 6 months. Similarly, Northey et al. (16) reported that moderate intensity PA for 45-60 minutes per session were associated with benefits to cognition in adults over the age of 50. Despite these preliminary findings, heterogeneity in the dose parameters across studies makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the frequency, duration, or intensity of activity needed to achieve cognitive improvements for any age group or population.

Acute bouts of PA:

Although the research described in the above sections have focused on the effects of longer-term (i.e., more than a single episode), or chronic, PA, it is important to acknowledge that a single brief session of PA (i.e., acute PA) also influences cognition. Studies demonstrate a small, transient improvement in cognition following the cessation of a single, acute bout of PA, with effect sizes (Cohen’s d, Cohen’s k, and Hedges’ g) ranging from 0.014 to 0.67 across six SRs and meta-analyses that summarized 12-79 studies (27, 65–68). Reported effects were most consistent for domains of executive function (65–68), but significant benefits were also realized for processing speed, attention (although see (27) for a discrepant finding) and memory (65, 66, 68). Although effects were observed across the lifespan, larger effects (Hedges’ g) were realized for preadolescent children (0.54 [0.21, 0.87]) and older adults (0.67 [0.40, 0.93]) relative to adolescents (0.04 [−0.14, 0.23]) and young adults (0.20 [0.07, 0.34]) for executive function (67). Similar age differences in effect sizes were reported for other aspects of cognition.

Studies have reported that PA intensity has an effect on cognition, although the pattern of effect has been inconsistent. Some findings suggest an inverted-U shaped curve, with moderate-intensity PA demonstrating a larger effect than light- and vigorous-intensity PA (66, 68), and other studies indicate that very light-, light-, and moderate-intensity PA benefited cognition, but hard-, very hard-, and maximal-intensity PA demonstrated no benefit (65, 80). The timing of the assessment of cognition relative to the cessation of the acute bout also demonstrated differential effects. PA bouts lasting 11-20 minutes demonstrated the greatest benefits, with bouts lasting less than 11 minutes or more than 20 minutes having smaller effects on cognition (65).

The investigation into biological or physiological pathways leading to changes in cognition following an acute bout of PA is in its early stages. Despite a number of empirical reports assessing acute PA effects on brain function using neuroimaging approaches (65, 86), no SR or meta-analysis has appeared. However, a meta-analysis examining a blood-based biomarker has indicated higher concentrations of peripheral blood BDNF following an acute bout of PA (both aerobic and resistance bouts). Findings further indicated that increased BDNF concentrations were observed following longer bout durations (>30 min relative to <30 min) in those who had higher cardiorespiratory fitness (i.e., > VO2 peak), and that the findings were selective to males (although 75% of participants across studies were male) (74). Such findings suggest that BDNF may serve as a marker for the acute effects of PA on brain function in healthy adult males.

Overall, the findings strongly indicate that transient cognitive benefits may be derived following single acute bouts of PA. Such effects appear strongest for preadolescent children and older adults and for a PA dose of moderate intensity (65–68), with further evidence supporting 11-20 minutes in duration as the optimal range for enhancing cognitive function (65). These findings are important and relevant to the Physical Guidelines for Americans because they suggest that the benefits of engaging in PA can be seen immediately (i.e., following an acute bout) and accumulate over time (i.e., following more chronic PA behavior).

Discussion:

In regards to our first aim, we concluded from this umbrella review that there is overall moderate evidence that PA positively influences cognition in humans. The ‘moderate’ grade emerged because there were noticeable gaps in some populations (e.g., adolescents, young and middle-aged adults) as well as significant heterogeneity in study designs, cognitive instruments employed, lack of consistent reporting of blinding and adherence/compliance, and poor descriptions of whether the interventions were successful at maintaining moderate-intensity PA through the course of the intervention. Similarly, there is also considerable variability in the type and quality of PA measurements employed across studies (87). Yet, despite these limitations and heterogeneity, we argue that the consistency of effects and of effect sizes across populations (16, 26), durations of PA (including acute bouts), intensities, comorbid conditions (58), and ages (12) is truly remarkable and demonstrates that sufficient evidence exists to conclude that PA positively influences cognitive function in humans.

Our second aim was to examine whether there was a particular age or population that showed the strongest or weakest associations with PA. Most studies have been conducted in preadolescent children and older adults, so conclusions about the effects of PA across the lifespan are inherently limited because of the lack of high-quality data available in other age groups. Nonetheless, this research in children and older adults suggests that benefits might be obtained across the lifespan. Yet, clearly more research is needed to determine effects in other age groups and to examine whether the magnitude of the benefit is greater at some ages (or in some populations) relative to others.

Our third aim was to examine whether there were cognitive domains especially susceptible to a PA intervention. Executive functions emerged as the most consistent cognitive domain affected. However, this conclusion should be interpreted cautiously. Many studies have prioritized the assessment of executive functions over that of other cognitive domains and there is considerable variability in the type and quality of instruments used to test executive (and all other) cognitive domains. Additionally, many of the instruments used to assess executive functioning are traditional neuropsychological tools that were primarily developed to aid in clinical diagnosis rather than to assess individual variation in normative cognitive functioning. As such, their sensitivity to detect changes as a function of an intervention (especially in the context of a normative sample) remains questionable.

Our fourth aim was to examine whether PA was associated with reducing risk for cognitive impairment in late adulthood. Here the prospective observational literature was unequivocal – engaging in greater amounts of PA was associated with a reduced risk of cognitive decline and impairment. It is important to note the methodological differences in the studies that make up this literature compared to the scientific literature discussed in other sections. In other sections of this review, the meta-analyses and SRs were primarily focused on RCTs while in the context of MCI and dementia the studies were prospective and observational and typically used self-reported measures of PA. Such methodological differences are important when reflecting on the strength and weaknesses of the literature examining cognitive outcomes as well as the populations, parameters, and measures that might be most sensitive to improvements with PA. Finally, we asked whether there are parameters of PA (e.g., intensity) that are more important for the modulation of cognitive and brain health. Unfortunately, we conclude that there is insufficient data about the optimal dose parameters. Moderate-intensity PA is the most commonly reported dose, yet there is a consistent lack of clarity across studies about how moderate-intensity is defined and measured. Several reports find that moderate-intensity interventions of longer durations had larger effect sizes than lighter intensity and shorter duration studies. Yet, the lack of specificity on dose and the variability in the dose delivered across studies, populations, and age-ranges led to a conclusion of Grade Not Assignable. Due to this between-study heterogeneity, similar ambiguity exists about the optimal dosage of PA necessary to achieve cardiovascular disease outcomes (85). Similarly, there are few studies examining the impact of sedentary behavior or light intensity activity on cognitive outcomes as most RCTs manipulate moderate intensity activity and not light intensity or sedentary behaviors. The most likely outcome is that the appropriate dose of PA will be moderated by age, population, and other factors sensitive to both cognitive function and PA.

While most studies reported beneficial associations of PA on cognition, others reported less robust or even absent effects. In such instances, it is important to consider the factors that may have led to these discrepant findings. Not all SRs and meta analyses were conducted using the same set of guiding principles and criteria, with some utilizing stronger theoretical and methodological approaches than others. Among the more poorly constructed SRs and meta-analyses, one obvious limitation was the inclusion of empirical reports with poor adherence and compliance, imprecise measurement of PA, insensitive cognitive measurements, or poor descriptions of PA parameters. In addition, the considerable variability in how PA is measured and quantified across studies can often lead to heterogeneity of results and erroneous conclusions (86). Many of these design and measurement issues are not captured by PRISMA guidelines and thus, could be influencing effect sizes and conclusions from meta-analyses and SRs.

For more effective translation and adoption of PA, it is important to understand the possible mechanisms by which PA influences brain and cognition. Mechanisms can be conceptualized at multiple levels of analysis (88). On the molecular and cellular level, PA directly influences expression of neurotransmitter and neurotrophic factors which in turn influence synaptic plasticity and cell proliferation and survival. PA might also influence cognitive and brain health by modifying insulin/glucose signaling, oxidative stress, inflammatory pathways, hormonal regulation, or cerebrovasculature (2, 83). Indeed, it is likely that all of these factors are enhancing different aspects of brain health. In addition, there might be multiple mediators at other levels of analysis. For example, PA might be modifying sleep behaviors which in turn improve cognitive function. In short, there are many possible mechanisms by which PA influences brain health; more research across these diverse levels is required to better elucidate the primary pathways driving effects and how those pathways interact.

The meta-analyses and SRs reviewed in this report predominantly focused on RCTs or experimental manipulations of exercise (in the context of acute bout studies). However, this contrasts with many of the studies on MCI and dementia which were observational and prospective. In these observational studies, PA was often measured by self-report whereas in RCTs it was generally controlled and experimentally manipulated. These methodological differences could be contributing to the differences in effect sizes and consistency between these literatures. It will be important for future research to conduct longer RCTs with larger sample sizes and with sufficiently protracted post-intervention follow-up assessments over many years to determine whether engaging in a PA treatment reduces the incident rate of MCI and dementia.

Given the findings herein and the noted limitations, this field would benefit from a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms of these relationships including central and peripheral biomarkers. Further, understanding of potential moderators of the PA-cognition relationship is needed, as reports suggest that the relationship may differ as a function of body composition, fitness level, sex, and health status, among other factors. Relatedly, reporting parameters of the intervention (i.e., compliance, adherence) is important to better understand the execution and quality of the intervention. One reason for the excitement surrounding PA effects on childhood cognition is the ability to link such findings to scholastic performance. Thus, there is a need to identify other ecologically-valid outcomes, not only in children, but also in adults who have the potential to strengthen the external validity of research on PA. Finally, future research needs greater consistency and harmonization in the cognitive instruments employed.

In summary, there are positive effects of PA on a broad array of cognitive outcomes. This evidence comes from a variety of assessments that measure changes in brain structure and function, cognition, and applied academic outcomes. Accordingly, such findings may serve to promote better cognitive function in healthy individuals, and improve cognitive function in those suffering from certain cognitive and brain disorders. These findings may lead to more informed policies about using PA to improve and shape cognitive function across the lifespan.

Acknowledgments:

The committee members did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors for the work contained in this manuscript. The committee reviewed all articles for relevant content, assessed the strength of the evidence, determined conclusions, and wrote the manuscript. The committee’s work during the process of conducting the review for the Physical Activity Guidelines was heavily supported by members of the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) who provided organizational and infrastructure support for the committee. DHHS also provided funding for a contract that provided staff who conducted the initial search and provided ongoing and infrastructural support related to summarizing the methods for the articles selected for the review. DHHS and contract staff were also involved in editing the manuscript. All authors have seen and approved this version and have no conflicts of interest to report. The conclusions in this article are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation.

This paper is being published as an official pronouncement of the American College of Sports Medicine. This pronouncement was reviewed for the American College of Sports Medicine by members-at-large and the Pronouncements Committee. Disclaimer: Care has been taken to confirm the accuracy of the information present and to describe generally accepted practices. However, the authors, editors, and publisher are not responsible for errors or omissions or for any consequences from application of the information in this publication and make no warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the currency, completeness, or accuracy of the contents of the publication. Application of this information in a particular situation remains the professional responsibility of the practitioner; the clinical treatments described and recommended may not be considered absolute and universal recommendations.

References

- 1.Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100(2):126–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH. Neural consequences of environmental enrichment. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2000;1(3):191–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benefiel AC, Dong WK, Greenough WT. Mandatory “Enriched” Housing of Laboratory Animals: The Need for Evidence-based Evaluation. ILAR J. 2005;46(2):95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobilo T, Liu Q-R, Gandhi K, Mughal M, Shaham Y, van Praag H. Running is the neurogenic and neurotrophic stimulus in environmental enrichment. Learn Mem. 2011;18(9):605–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Etnier JL, Salazar W, Landers DM, Petruzzello SJ, Han M, Nowell P. The influence of physical fitness and exercise upon cognitive functioning: A meta-analysis. Journal of sport & exercise psychology. 1997;19(3):249–77. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colcombe S, Kramer AF. Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Sci. 2003;14(2):125–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prakash RS, Voss MW, Erickson KI, Kramer AF. Physical Activity and Cognitive Vitality. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66(1):769–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Committee. Scientific Report - 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines - health.gov. [date unknown]; [cited 2018 Jun 2 ] Available from: https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/report.aspx.

- 9.Etnier JL, Nowell PM, Landers DM, Sibley BA. A meta-regression to examine the relationship between aerobic fitness and cognitive performance. Brain Res Rev. 2006;52(1):119–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rathore A, Lom B. The effects of chronic and acute physical activity on working memory performance in healthy participants: a systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roig M, Nordbrandt S, Geertsen SS, Nielsen JB. The effects of cardiovascular exercise on human memory: a review with meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(8):1645–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith PJ, Blumenthal JA, Hoffman BM, et al. Aerobic exercise and neurocognitive performance: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(3):239–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loprinzi PD, Frith E, Edwards MK, Sng E, Ashpole N. The Effects of Exercise on Memory Function Among Young to Middle-Aged Adults: Systematic Review and Recommendations for Future Research. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(3):691–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barha CK, Davis JC, Falck RS, Nagamatsu LS, Liu-Ambrose T. Sex differences in exercise efficacy to improve cognition: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in older humans. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2017;46:71–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly ME, Loughrey D, Lawlor BA, Robertson IH, Walsh C, Brennan S. The impact of exercise on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;16:12–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Northey JM, Cherbuin N, Pumpa KL, Smee DJ, Rattray B. Exercise interventions for cognitive function in adults older than 50: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(3):154–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogawa EF, You T, Leveille SG. Potential Benefits of Exergaming for Cognition and Dual-Task Function in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. J Aging Phys Act. 2016;24(2):332–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu Y, Wang Y, Burgess EO, Wu J. The effects of Tai Chi exercise on cognitive function in older adults: A meta-analysis. Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2013;2(4):193–203. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sáez de Asteasu ML, Martínez-Velilla N, Zambom-Ferraresi F, Casas-Herrero Á, Izquierdo M. Role of physical exercise on cognitive function in healthy older adults: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;37:117–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Álvarez-Bueno C, Pesce C, Cavero-Redondo I, Sánchez-López M, Garrido-Miguel M, Martínez-Vizcaíno V. Academic Achievement and Physical Activity: A Meta-analysis [Internet]. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Álvarez-Bueno C, Pesce C, Cavero-Redondo I, Sánchez-López M, Martínez-Hortelano JA, Martínez-Vizcaíno V. The Effect of Physical Activity Interventions on Children’s Cognition and Metacognition: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(9):729–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ash T, Bowling A, Davison K, Garcia J. Physical Activity Interventions for Children with Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Disabilities-A Systematic Review. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2017;38(6):431–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bustamante EE, Williams CF, Davis CL. Physical Activity Interventions for Neurocognitive and Academic Performance in Overweight and Obese Youth: A Systematic Review. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63(3):459–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carson V, Hunter S, Kuzik N, et al. Systematic review of physical activity and cognitive development in early childhood. J Sci Med Sport. 2016;19(7):573–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Greeff JW, Bosker RJ, Oosterlaan J, Visscher C, Hartman E. Effects of physical activity on executive functions, attention and academic performance in preadolescent children: a meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21(5):501–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donnelly JE, Hillman CH, Castelli D, et al. Physical Activity, Fitness, Cognitive Function, and Academic Achievement in Children: A Systematic Review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(6):1197–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janssen M, Toussaint HM, van Mechelen W, Verhagen EA. Effects of acute bouts of physical activity on children’s attention: a systematic review of the literature. Springerplus. 2014;3:410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poitras VJ, Gray CE, Borghese MM, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(6 Suppl 3):S197–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santana CCA, Azevedo LB, Cattuzzo MT, Hill JO, Andrade LP, Prado WL. Physical fitness and academic performance in youth: A systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017;27(6):579–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sullivan RA, Kuzel AH, Vaandering ME, Chen W. The Association of Physical Activity and Academic Behavior: A Systematic Review. J Sch Health. 2017;87(5):388–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watson A, Timperio A, Brown H, Best K, Hesketh KD. Effect of classroom-based physical activity interventions on academic and physical activity outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeng N, Ayyub M, Sun H, Wen X, Xiang P, Gao Z. Effects of Physical Activity on Motor Skills and Cognitive Development in Early Childhood: A Systematic Review [Internet]. BioMed Research International. 2017; doi: 10.1155/2017/2760716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esteban-Cornejo I, Tejero-Gonzalez CM, Sallis JF, Veiga OL. Physical activity and cognition in adolescents: A systematic review. J Sci Med Sport. 2015;18(5):534–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li JW, O’Connor H, O’Dwyer N, Orr R. The effect of acute and chronic exercise on cognitive function and academic performance in adolescents: A systematic review. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20(9):841–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marques A, Santos DA, Hillman CH, Sardinha LB. How does academic achievement relate to cardiorespiratory fitness, self-reported physical activity and objectively reported physical activity: a systematic review in children and adolescents aged 6–18 years [Internet]. Br J Sports Med. 2017; doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin A, Booth JN, Laird Y, Sproule J, Reilly JJ, Saunders DH. Physical activity, diet and other behavioural interventions for improving cognition and school achievement in children and adolescents with obesity or overweight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1:CD009728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruiz-Ariza A, Grao-Cruces A, Loureiro NEM de, Martínez-López EJ. Influence of physical fitness on cognitive and academic performance in adolescents: A systematic review from 2005–2015. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2017;10(1):108–33. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spruit A, Assink M, van Vugt E, van der Put C, Stams GJ. The effects of physical activity interventions on psychosocial outcomes in adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;45:56–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cerrillo-Urbina AJ, García-Hermoso A, Sánchez-López M, Pardo-Guijarro MJ, Gómez JL Santos, Martínez-Vizcaíno V. The effects of physical exercise in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Child Care Health Dev. 2015;41(6):779–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Den Heijer AE, Groen Y, Tucha L, et al. Sweat it out? The effects of physical exercise on cognition and behavior in children and adults with ADHD: a systematic literature review. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2017;124(Suppl 1):3–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan BWZ, Pooley JA, Speelman CP. A Meta-Analytic Review of the Efficacy of Physical Exercise Interventions on Cognition in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder and ADHD. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(9):3126–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beckett MW, Ardern CI, Rotondi MA. A meta-analysis of prospective studies on the role of physical activity and the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barreto P de S, Demougeot L, Vellas B, Rolland Y. Exercise training for preventing dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and clinically meaningful cognitive decline: a systematic review and meta-analysis [Internet]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017; doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brasure M, Desai P, Davila H, et al. Physical Activity Interventions in Preventing Cognitive Decline and Alzheimer-Type Dementia: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(1):30–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cammisuli DM, Innocenti A, Franzoni F, Pruneti C. Aerobic exercise effects upon cognition in Mild Cognitive Impairment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Archives Italiennes de Biologie. 2017;155(1/2):55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gonçalves A-C, Cruz J, Marques A, Demain S, Samuel D. Evaluating physical activity in dementia: a systematic review of outcomes to inform the development of a core outcome set. Age Ageing. 2018;47(1):34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Groot C, Hooghiemstra AM, Raijmakers PGHM, et al. The effect of physical activity on cognitive function in patients with dementia: A meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;25:13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morrin H, Fang T, Servant D, Aarsland D, Rajkumar AP. Systematic review of the efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions in people with Lewy body dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(3):395–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee HS, Park SW, Park YJ. Effects of Physical Activity Programs on the Improvement of Dementia Symptom: A Meta-Analysis [Internet]. Bio Med Research International. 2016; available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2016/2920146/. doi: 10.1155/2016/2920146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panza GA, Taylor BA, MacDonald HV, et al. Can Exercise Improve Cognitive Symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2018;66(3):487–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sofi F, Valecchi D, Bacci D, et al. Physical activity and risk of cognitive decline: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Intern Med. 2011;269(1):107–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Song D, Yu DSF, Li PWC, Lei Y. The effectiveness of physical exercise on cognitive and psychological outcomes in individuals with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2018;79:155–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng G, Zhou W, Xia R, Tao J, Chen L. Aerobic Exercises for Cognition Rehabilitation following Stroke: A Systematic Review. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2016;25(11):2780–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zheng W, Xiang Y-Q, Ungvari GS, et al. Tai chi for mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Psychogeriatrics. 2017;17(6):514–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morrison JD, Mayer L. Physical activity and cognitive function in adults with multiple sclerosis: an integrative review. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(19):1909–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silva FC da, Iop R da R, Oliveira LC de, et al. Effects of physical exercise programs on cognitive function in Parkinson’s disease patients: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the last 10 years. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(2):e0193113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murray DK, Sacheli MA, Eng JJ, Stoessl AJ. The effects of exercise on cognition in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. Transl Neurodegener. 2014;3(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Firth J, Stubbs B, Rosenbaum S, et al. Aerobic Exercise Improves Cognitive Functioning in People With Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(3):546–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Quigley A, O’Brien K, Parker R, MacKay-Lyons M. Exercise and cognitive function in people living with HIV: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Podolski N, Brixius K, Predel HG, Brinkmann C. Effects of Regular Physical Activity on the Cognitive Performance of Type 2 Diabetic Patients: A Systematic Review. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2017;15(10):481–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao RR, O’Sullivan AJ, Singh MA Fiatarone. Exercise or physical activity and cognitive function in adults with type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance or impaired glucose tolerance: a systematic review. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. 2018;15:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Furmaniak AC, Menig M, Markes MH. Exercise for women receiving adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD005001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Myers JS, Erickson KI, Sereika SM, Bender CM. Exercise as an Intervention to Mitigate Decreased Cognitive Function From Cancer and Cancer Treatment: An Integrative Review [Internet]. Cancer Nurs. 2017; doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oberlin LE, Waiwood AM, Cumming TB, Marsland AL, Bernhardt J, Erickson KI. Effects of Physical Activity on Poststroke Cognitive Function: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Stroke. 2017;48(11):3093–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chang YK, Labban JD, Gapin JI, Etnier JL. The effects of acute exercise on cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Brain Res. 2012;1453:87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lambourne K, Tomporowski P. The effect of exercise-induced arousal on cognitive task performance: a meta-regression analysis. Brain Res. 2010;1341:12–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ludyga S, Gerber M, Brand S, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Pühse U. Acute effects of moderate aerobic exercise on specific aspects of executive function in different age and fitness groups: A meta-analysis. Psychophysiology. 2016;53(11):1611–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McMorris T, Hale BJ. Differential effects of differing intensities of acute exercise on speed and accuracy of cognition: a meta-analytical investigation. Brain Cogn. 2012;80(3):338–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Falck RS, Davis JC, Liu-Ambrose T. What is the association between sedentary behaviour and cognitive function? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2016;bjsports-2015-095551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Firth J, Cotter J, Carney R, Yung AR. The pro-cognitive mechanisms of physical exercise in people with schizophrenia. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174(19):3161–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li M-Y, Huang M-M, Li S-Z, Tao J, Zheng G-H, Chen L-D. The effects of aerobic exercise on the structure and function of DMN-related brain regions: a systematic review. Int J Neurosci. 2017;127(7):634–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.de Assis GG, de Almondes KM. Exercise-dependent BDNF as a Modulatory Factor for the Executive Processing of Individuals in Course of Cognitive Decline. A Systematic Review [Internet]. Front Psychol. 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dinoff A, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, et al. The Effect of Exercise Training on Resting Concentrations of Peripheral Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF): A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(9):e0163037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dinoff A, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Lanctôt KL. The effect of acute exercise on blood concentrations of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in healthy adults: a meta-analysis. Eur J Neurosci. 2017;46(1):1635–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Frederiksen KS, Gjerum L, Waldemar G, Hasselbalch SG. Effects of Physical Exercise on Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers: A Systematic Review of Intervention Studies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;61(1):359–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Halloway S, Wilbur J, Schoeny ME, Arfanakis K. Effects of Endurance-Focused Physical Activity Interventions on Brain Health: A Systematic Review [Internet]. Biol Res Nurs. 2016; doi: 10.1177/1099800416660758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pedroso RV, Fraga FJ, Ayán C, Carral JM Cancela, Scarpari L, Santos-Galduróz RF. Effects of physical activity on the P300 component in elderly people: a systematic review. Psychogeriatrics. 2017;17(6):479–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sexton CE, Betts JF, Demnitz N, Dawes H, Ebmeier KP, Johansen-Berg H. A systematic review of MRI studies examining the relationship between physical fitness and activity and the white matter of the ageing brain. Neuroimage. 2016;131:81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Loprinzi PD, Frith E, Edwards MK. Resistance exercise and episodic memory function: a systematic review [Internet]. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2018; doi: 10.1111/cpf.12507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brown BM, Rainey-Smith SR, Castalanelli N, et al. Study protocol of the Intense Physical Activity and Cognition study: The effect of high-intensity exercise training on cognitive function in older adults. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2017;3(4):562–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mura G, Carta MG, Sancassiani F, Machado S, Prosperini L. Active exergames to improve cognitive functioning in neurological disabilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis [Internet]. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017; doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.17.04680-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stanmore E, Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, de Bruin ED, Firth J. The effect of active video games on cognitive functioning in clinical and non-clinical populations: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2017;78:34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Erickson KI, Hillman CH, Kramer AF. Physical activity, brain, and cognition. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 2015;4:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zheng G, Xia R, Zhou W, Tao J, Chen L. Aerobic exercise ameliorates cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(23):1443–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Williams PT. Physical fitness and activity as separate heart disease risk factors: a meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(5):754–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hillman CH, Pontifex MB, Raine LB, Castelli DM, Hall EE, Kramer AF. The effect of acute treadmill walking on cognitive control and academic achievement in preadolescent children. Neuroscience. 2009;159(3):1044–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Strath SJ, Kaminsky LA, Ainsworth BE, et al. Guide to the assessment of physical activity: Clinical and research applications: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128(20):2259–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stillman CM, Cohen J, Lehman ME, Erickson KI. Mediators of Physical Activity on Neurocognitive Function: A Review at Multiple Levels of Analysis [Internet]. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016. [cited 2018 Nov 4 ];10 available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5161022/. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]