Abstract

Purpose.

To conduct a systematic literature review to determine if physical activity episodes of <10 minutes in duration have health-related benefits; or, alternatively, if the benefits are only realized when the duration of physical activity episodes is ≥10 minutes.

Methods.

The primary literature search was conducted for the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report and encompassed literature through June 2017, with an additional literature search conducted to include literature published through March 2018 for inclusion in this systematic review.

Results.

The literature review identified 29 articles that were pertinent to the research question that used either cross-sectional, prospective cohort, or randomized designs. One prospective cohort study (N=4,840) reported similar associations between moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and all-cause mortality when examined as total MVPA, MVPA in bouts ≥5 minutes in duration, or MVPA in bouts ≥10 minutes in duration. Additional evidence was identified from cross-sectional and prospective studies to support that bouts of physical activity <10 minutes in duration are associated with a variety of health outcomes. Randomized studies only examined bouts of physical activity ≥10 minutes in duration.

Conclusions.

The current evidence, from cross-sectional and prospective cohort studies, supports that physical activity of any bout duration is associated with improved health outcomes, which includes all-cause mortality. This may suggest the need for a contemporary paradigm shift in public health recommendations for physical activity, which supports total moderate-to-vigorous physical activity as an important lifestyle behavior regardless of the bout duration.

Keywords: physical activity, exercise, bouts

Introduction

Physical activity recommendations have traditionally focused on moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), and this was interpreted as activity performed in a continuous manner. The historical perspective of these recommendations was summarized in the US Surgeon General’s Report on Physical Activity and Health (1). In the mid-1980’s, Haskell suggested that some forms of physical activity may not result in an improvement in physical fitness, but the acute effects of repetition of physical activity may still result in improvements in health (2).

Emerging evidence began to support the concept that physical activity could have beneficial effects when accumulated in multiple shorter bouts performed across the day rather than solely relying on one longer continuous bout of physical activity. For example, one of the first empirical studies was conducted by Ebisu et al. (3), and results demonstrated that multiple bouts of running equivalent to 30 minutes per day (e.g., 3 session of 10 minutes) over a period of 8 weeks improved cardiorespiratory fitness and improved high-density lipoprotein (HDL) in young men. Pate et al. published the first contemporary recommendation, on behalf of the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), for MVPA to be “accumulated” to achieve a specific threshold of daily physical activity that, in turn, could result in health and fitness benefits (4). This recommendation stated that “intermittent bouts of physical activity, as short as 8 to 10 minutes, totaling 30 minutes or more on most days provided beneficial health and fitness effects.” This resulted in a new paradigm, suggesting the accumulation of physical activity across bouts of short duration would provide health benefits. This paradigm was reinforced in the report by Haskell et al. (5) in the physical activity recommendations for adults from the ACSM and the American Heart Association (AHA). The 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans continued to support this recommendation for adults, stating that “aerobic activity should be performed in episodes of ≥10 minutes” (6).

The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee (PAGAC) recognized, however, that not all free-living physical activity is performed in a continuous manner, and most activity is likely performed in episodes typically <10 minutes in duration. An example of this may be the short and sporadic bouts of physical activity that can be performed in selective agricultural, goods producing, and manufacturing occupations. Church et al. (7) have demonstrated that these types of occupations have been decreasing in prevalence which has contributed to a decrease in total energy expenditure, mostly due to a decrease in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, which may also be associated with negative health consequences. Thus, the 2018 PAGAC examined the available scientific literature to determine if physical activity episodes of <10 minutes in duration have health-related benefits; or, alternatively, if the benefits are only realized when the duration of physical activity episodes is ≥10 minutes.

METHODS

The overarching methods used to conduct systematic reviews informing the 2018 PAGAC Scientific Report are described in detail elsewhere (8, 9). The searches were conducted using electronic databases (PubMed®, CINAHL, and Cochrane). An initial search was conducted to identify systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and pooled analyses examining the relationship between bout duration and various health outcomes; and this search did not identify sufficient literature to answer the proposed research question. Therefore, a de novo search of original research was conducted until June 2017 for the 2018 PAGAC report. This de novo search of original research was expanded to include literature published through March 2018 for inclusion in this manuscript. Eligibility criteria were original research studies published in English; examining bouts as the physical activity exposure among adults; and health outcomes including weight status, body composition, blood lipids, blood pressure, metabolic syndrome, risk of type 2 diabetes, and risk of cardiovascular disease. The full search strategy is available at https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/report/supplementary_material/pdf/Exposure_Q5_Bouts_Evidence_Portfolio.pdf. For the search conducted to include literature through March 2018, additional outcomes such as frailty and all-cause mortality were permissible as outcomes. Search terms included bout-specific terms combined with outcome-specific terms. However, the PAGAC Scientific Report (30) included a specific section related to high-intensity interval training (HIIT) that was separate from this review, and therefore the literature specific to HIIT is not included in this review.

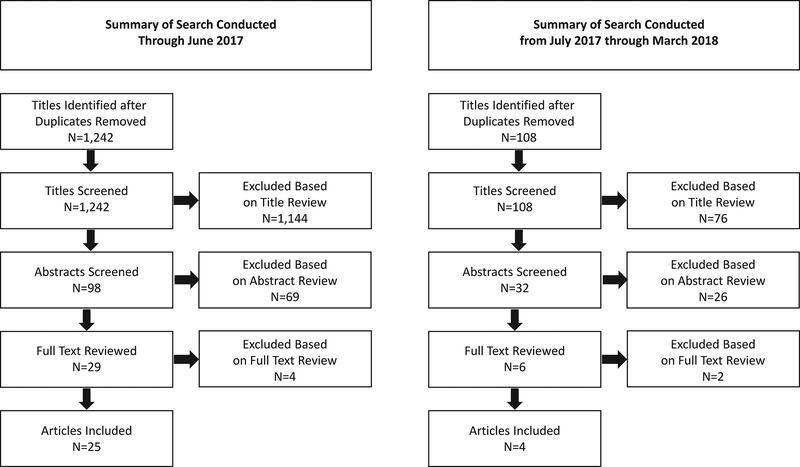

The titles and abstracts of the identified articles were independently screened by two reviewers. The full-text of relevant articles were reviewed to identify those meeting the inclusion criteria. Two professional abstractors independently abstracted data and conducted a quality or risk of bias assessment using the USDA NEL Bias Assessment Tool (BAT) (10). Discrepancies in article selection or data abstractions were resolved by discussion or by a third reviewer, if needed. The protocol for this review was registered with the PROSPERO database registration (CRD42018092854). The summary of the review process for the articles included in this systematic review is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Summary of literature search.

RESULTS

Search Results

For the 2018 PAGAC Report, 25 original manuscripts published from 1995 to 2017, based on 23 original studies, that examined the relationship between bouts of physical activity and different health outcomes were included as sources of evidence (11–35). Two pairs of these studies reported on different outcomes from the same studies (12–15). Of the 23 studies examined, 11 used a cross-sectional design (14–17, 21–23, 26, 27, 31, 32, 34), 2 used a prospective design (18, 36), and 10 used a randomized design (11–13, 19, 20, 24, 25, 28–30, 35). The additional search conducted through March 2018 resulted in four additional original research studies, including one randomized control trial (37), one prospective cohort (38), and two cross-sectional studies (39, 40). The analytical sample size across these various studies ranged from 22 to 6,321. A summary of the articles, by study design and health outcomes examined, is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of study designs that examined physical activity bout duration by health outcome.

| Health Outcomes | Cross-Sectional Studies | Prospective Studies | Randomized Studies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight or Body Composition | Incidence of Obesity | 1 | ||

| Body Mass Index | 6 | 6 | ||

| Body Fatness | 7 | 8 | ||

| Blood Pressure | 2 | 1 | 6 | |

| Lipids | Total Cholesterol | 2 | ||

| LDL Cholesterol | 1 | 4 | ||

| HDL Cholesterol | 4 | 1 | 5 | |

| Triglycerides | 3 | 4 | ||

| Glycemic Control | Fasting Blood Glucose | 3 | 3 | |

| Fasting Insulin | 2 | 2 | ||

| Oral Glucose Tolerance Test | 1 | |||

| HbA1c | 1 | |||

| Metabolic Syndrome | 2 | |||

| c-Reactive Protein | 2 | |||

| Framingham Cardiovascular Disease Risk Score | 1 | |||

| Frailty | 1 | |||

| Multi-Morbidity | 1 | |||

| All-Cause Mortality | 1 | |||

Measures of Physical Activity Bouts

Within the context of this review the methods used to assess physical activity were quantified. The majority of studies (n=18) used objective measure to assess physical activity that included accelerometers (14, 15, 17, 18, 21–26, 31–34, 38–41), with other studies using a heart rate monitor and pedometer (30), a combination of self-report and heart rate monitor (12, 29, 35), and direct supervision of physical activity sessions (19, 37). The remaining four studies used self-report (exercise logs and diaries) to quantify physical activity (11, 13, 20, 28).

Duration of Bouts

The duration of bouts varied across the studies that were examined. Cross-sectional (14–17, 21–23, 26, 27, 31, 32, 34, 39, 40) and prospective studies (18, 36, 38) reported on bouts of physical activity that were <10 minutes, whereas randomized studies (11–13, 19, 20, 24, 25, 28–30, 35, 37) reported only on bouts that were ≥10 minutes in duration.

Physical Activity Bout Duration and Health Outcomes: Randomized Studies

Twelve manuscripts reported on randomized designs, and these studies only included bouts of physical activity that were ≥10 minutes in duration (11–13, 19, 20, 24, 25, 28–30, 35, 37). In these studies intermittent bouts resulted in similar or enhanced effects when compared to continuous bouts of physical activity of longer duration for outcomes of weight and body composition (11–13, 19, 20, 24, 25, 28–30, 35, 37), blood pressure (12, 19, 20, 24, 28, 37), blood lipids (12, 19, 28, 29, 35), or glucose or insulin (12, 19, 37). These studies, however, do not provide information to evaluate bouts of physical activity of <10 minutes in duration.

Physical Activity Bout Duration and Health Outcomes: Cross-Sectional and Prospective Studies

The cross-sectional and prospective studies reported on a variety of health outcomes that included body weight or body composition (15, 16, 21, 23, 26, 27, 31, 34, 36), blood pressure (27, 34, 36), blood lipids (14, 18, 23, 27, 34), glucose or insulin (22, 26, 34), metabolic syndrome (17, 26), inflammatory biomarkers (27, 34), a composite of cardiovascular disease risk (32), frailty (39), or multimorbidity (40). In addition, a more recent study reported on all-cause mortality (38). A brief summary of these findings by health outcome are presented below and also presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the number of studies where health benefits are observed when physical activity in bouts ≥10 minutes is compare to bouts <10 minutes.

| Number of Studies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Outcomes | Effect in Bouts <10 minutes and ≥10 minutes | Effect in Bouts <10 minutes but Not in Bouts ≥10 minutes | Effect in Bouts ≥10 minutes but Not in Bouts <10 minutes | |

| Weight or Body Composition | Incidence of Obesity | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Body Mass Index | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Body Fatness | 5 | 1 | 1 | |

| Blood Pressure | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| Lipids | Total Cholesterol | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| LDL Cholesterol | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| HDL Cholesterol | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Triglycerides | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Glycemic Control | Fasting Blood Glucose | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Fasting Insulin | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Oral Glucose Tolerance Test | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| HbA1c | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Metabolic Syndrome | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| c-Reactive Protein | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Framingham Cardiovascular Disease Risk Score | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Frailty | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Multi-Morbidity | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| All-Cause Mortality | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

Body Mass Index, Adiposity, and Obesity.

Some studies have examined whether physical activity accumulated in bouts <10 minutes in duration are associated with body mass index (BMI) or body fatness (15, 16, 21, 23, 26, 27, 31, 34, 36). In a cohort study by White et al. (36), physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes in duration was associated with lower incidence of obesity, whereas physical activity accumulated in <10 minutes was not associated with lower incidence of obesity. In cross-sectional studies examining BMI, two favored physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes compared to physical activity accumulated in bouts <10 minutes (27, 34), one favored physical activity accumulated in <10 minute bouts (16), and three did not report a difference between physical activity accumulated in bouts <10 minutes versus bouts of ≥10 minutes (21, 23, 26). Of the seven cross-sectional studies examining measures of body fatness, one favored physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes (31), one reported that the association between total volume of physical activity was more strongly associated with cardiometabolic health than physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes (34), and five studies showed no difference between physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes versus physical activity not accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes (15, 16, 23, 26, 27).

Resting Blood Pressure:

Evidence for resting blood pressure is available from one cohort study and two cross-sectional studies. In the cohort study (36) demonstrated that physical activity in bouts of either ≥10 minutes or <10 minutes in duration was associated with lower incidence of hypertension. In both of the cross-sectional studies showed that physical activity accumulated in bouts <10 minutes was associated with lower resting blood pressure (27, 34).

Blood Lipids:

One cross-sectional study showed physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes or <10 minutes in duration was associated with lower total cholesterol (27). In the one cross-sectional study examining LDL cholesterol, both physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes in duration and in <10 minutes in duration were inversely associated with LDL cholesterol (27).

For HDL cholesterol, the one prospective study, which was only 14 weeks in duration, reported that physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes in duration predicted change in HDL, whereas when the threshold was reduced to include bouts of at least 5 minutes this pattern of physical activity was not predictive of change in HDL (18). Of the four cross-sectional studies reviewed, two showed similar associations between HDL and physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes and <10 minutes (23, 27), one showed that physical activity accumulated in bouts as short as at least 32 seconds was associated with higher HDL (14), and one showed physical activity accumulated in bouts <10 minutes was more strongly associated with HDL than physical activity accumulated in ≥10 minutes (34).

Three cross-sectional studies examined the association between physical activity and triglycerides. In two of these studies, there were similar associations of triglycerides with physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes in duration or in bouts <10 minutes (23, 27). One of these studies showed physical activity accumulated in bouts of <10 minutes was more strongly associated with lower triglycerides than physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes (34).

Fasting Glucose, Fasting Insulin, and HbA1c.

Three cross-sectional studies examined the association between physical activity and fasting glucose (14, 27, 34), two with fasting insulin (26, 34), and one with HbA1c (22). For fasting glucose, in one study bouts of physical activity at least 3 minutes in duration were associated with lower fasting glucose (14), in one study there was no difference in the association between fasting glucose and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity accumulated in bouts of <10 minute versus bouts of ≥10 minutes (27), and in one study physical activity accumulated in bouts of <10 minutes was more strongly associated with lower fasting glucose when compared to physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes (34). For fasting insulin, one study showed no difference in the association when comparing moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity accumulated in <10 minutes and ≥10 minutes (26), and one study showed physical activity accumulated in bouts of <10 minutes was more strongly associated fasting insulin when compared to physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes in duration (34). In the one study examining HbA1c, physical activity accumulated in bouts <10 minutes predicted lower HbA1c, whereas physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes in duration was not predictive of lower HbA1c (22).

Metabolic Syndrome.

Two cross-sectional studies were reviewed that reported on the association between physical activity and metabolic syndrome (17, 26). In one study, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity accumulated in bouts of 1 to 9 minutes, 4 to 9 minutes, or 7 to 9 minutes in duration predicted lower odds of having metabolic syndrome (42) independent of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes (17). In an additional study odds of having metabolic syndrome (43) did not differ when comparing physical activity accumulated in bouts of <10 minutes versus ≥10 minutes (26).

C-Reactive Protein.

Two cross-sectional studies examined the association between physical activity and c-reactive protein (27, 34). One study showed no difference in the association between c-reactive protein and physical activity accumulated in bouts of <10 minutes in duration and bouts of ≥10 minutes (27). One study showed that physical activity accumulated in bouts of <10 minutes was more strongly associated with lower c-reactive protein when compared to physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes (34).

Cardiovascular Risk Score.

One cross-sectional study examined the association between physical activity and the Framingham Cardiovascular Disease Risk Score (32). In this study, physical activity accumulated in bouts of 1 to 5 minutes, 6 to 10 minutes, 11 to 15 minutes, or 20 to 120 minutes in duration and during total waking time were negatively associated with Framingham Cardiovascular Disease Risk Score.

Frailty.

Aging is typically associated with an increase in frailty. Kehler et al. examined data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to determine if MVPA performed in bouts of ≥10 minutes had a differential influence on the frailty index compared to MVPA performed in bouts of <10 minutes in adults 50 years of age or older (39). In this study, meeting 50–99% of 150 minutes per week of MVPA was associated with a reduced frailty index, with similar findings observed regardless of whether MVPA was performed in bouts of ≥10 minutes or in bouts of <10 minutes.

Multi-Morbidity.

Multi-morbidity is the presence of two or more chronic conditions such as coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and others. Loprinzi examined data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to determine if physical activity bouts that were ≥10 minutes in duration or were <10 minutes in duration were associated with multi-morbidity (40). In this analysis, both bouts of MVPA ≥10 minutes in duration and those <10 minutes in duration were independently associated with the presence of multi-morbidity. These findings provide support for promoting MVPA regardless of bout duration.

All-Cause Mortality.

A recent finding is based on the data that are now available regarding physical activity bout duration and all-cause mortality. In a prospective examination of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Saint-Maurice et al. examined the influence of MVPA of different bout durations (total MVPA regardless of bout duration, MVPA in bouts of at least 5 minutes, MVPA in bouts of ≥10 minutes) on all-cause mortality over an average follow-up period of 6.6 years (38). In this analysis, the hazard ratios were similar across quartiles of MVPA regardless of bout duration, suggesting that the reduction in mortality risk is independent of how MVPA is accumulated.

DISCUSSION

Summary and Public Health Impact

The 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommended that physical activity be accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes in duration to influence a variety of health-related outcomes (6). This was consistent with an initial paradigm shift that occurred approximately 20 years early when it was suggested by the CDC and ACSM that physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes in duration can improve a variety of health-related outcomes (4). This current review of the evidence continues to support that physical activity accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes in duration can improve a variety of health-related outcomes. However, additional evidence, from cross-sectional and prospective cohort studies, suggests that physical activity accumulated in bouts that are <10 minutes is also associated with favorable health-related outcomes, including all-cause mortality. This is of public health importance because it suggests that engaging in physical activity, regardless of length of the bout, may have health-enhancing effects. This is of particular importance for individuals who are unwilling or unable to engage in physical activity bouts that are ≥10 minutes in duration. It also adds support to public health initiatives advocating physical activity behaviors that are unlikely to require 10 minutes, such as climbing a flight of stairs or parking the car in a more distant part of the parking lot. This may suggest the need for a contemporary paradigm shift in public health recommendations for physical activity, which encourages engagement in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity as an important lifestyle behavior to enhance health, with potential benefits realized regardless of the bout duration.

Needs for Future Research

The evidence from this review supports that physical activity accumulated in bouts <10 minutes in duration are associated with enhanced health across a variety of outcomes. There is, however, a need for additional research related to the accumulation of physical activity and it association with health. These additional research needs are described below.

Conduct longitudinal research, either in the form of prospective studies or randomized controlled trials, to examine whether physical activity accumulated in bouts of <10 minutes in duration enhances health outcomes.

The majority of studies reviewed that support the health benefits of physical activity accumulated in bouts of <10 minutes in duration used a cross-sectional design, with none of the randomized studies reporting on the effects of physical activity accumulated in bouts of <10 minutes. Having this knowledge will inform potential cause and effect rather than simply associations.

Conduct research to compare bouts of physical activity of <10 minutes to ≥10 minutes, which also equates for volume and total energy expenditure between these physical activity patterns, to examine the effects on health outcomes.

The randomized studies that were specifically designed to equate for volume of physical activity or energy expenditure only examined the effects of physical activity performed in bouts ≥10 minutes. Thus, appropriately designed studies are needed to confirm the findings of the cross-sectional and prospective observational studies regarding the health benefits of physical activity accumulated in bouts ≥10 minutes in duration.

Conduct large research trials with ample sample sizes to allow for stratum-specific analyses to determine whether the influence of physical activity accumulated in bouts of varying length on health outcomes varies by age, sex, race/ethnicity, socio-economic status, initial weight status, or other demographic characteristics.

Based on the studies reviewed, there is limited evidence available on whether the influence of physical activity varies when the exposure to physical activity is consistent across individuals with different demographic characteristics. Having this information will inform public health recommendations about whether physical activity exposure of varying bout length to enhance health needs to vary by age, sex, race/ethnicity, socio-economic status, weight status and other demographic characteristics, and may allow for more precise individual-level physical activity recommendations.

Include measurement methods in prospective and randomized studies that will allow for the evaluation of whether physical activity performed in a variety of bout lengths has differential effects on health outcomes.

Based on this review, randomized studies were not identified that reported on physical activity accumulated in bouts that were <10 minutes in duration, and only three prospective studies were identified that reported on physical activity accumulated in bouts that were <10 minutes. This may be a result of the methods used to assess physical activity in randomized and prospective studies, suggesting the need to include physical activity assessment methods that allow for these data to be available for analysis. For example, the use of objective monitoring that allows for physical activity data to be collected in 1-minute epochs may be preferable to self-reported methods when examining the duration of activity bouts that are associated with improved health.

Conduct meta-analyses and systematic reviews of longitudinal prospective studies to evaluate the effect of physical activity accumulated in varying bout durations on health outcomes.

High-quality systematic reviews and meta-analyses were not identified in the literature that have summarized the evidence related to physical activity accumulated in varying bout durations and health outcomes. With specific regard to a summary of the evidence related to physical activity bout durations of <10 minutes, this may have been influenced by the current lack of sufficient prospective and randomized studies. This resulted in the need to examine limited number of individual studies that addressed this topic. As additional prospective and randomized studies are conducted on this topic, meta-analyses and systematic reviews should be conducted that will provide information on the consistency and magnitude of the overall effect size of the relationships observed across the original studies.

Conduct appropriately designed studies to examine the mechanistic pathways by which physical activity bouts of varying durations, particularly bouts of physical activity <10 minutes in duration, may influence various health-related outcomes.

This review of the literature was not designed to identify and summarize the scientific literature related to the potential mechanistic pathways of how physical activity bouts of varying durations, particularly <10 minutes in duration, may influence health-related measures. This may be important for understanding the biology of physical activity, provide a foundation for future research, and may influence for whom physical activity bouts <10 minutes in duration may be most effective.

Conduct studies to examine the effects of light-intensity physical activity accumulated in bouts of <10 minutes and ≥10 minutes on health outcomes.

The studies reviewed primarily focused on MVPA within the context of physical activity bout duration. Thus, these studies do not contribute to an understanding of how light-intensity physical activity may influence health outcomes, and whether bout duration of light-intensity physical activity may influence this potential relationship. This is a potentially important public health question given the potential for lifestyle, household, and occupational activity to be performed in bouts <10 minutes and at a light-intensity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors also gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Anne Brown Rodgers, HHS consultant for technical writing support of the Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report; and ICF librarians, abstractors, and additional support staff.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding

The results of this study are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate manipulation. The Committee’s work was supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Committee members were reimbursed for travel and per diem expenses for the five public meetings; Committee members volunteered their time.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor

HHS staff provided general administrative support to the Committee and assured that the Committee adhered to the requirements for Federal Advisory Committees. HHS also contracted with ICF, a global consulting services company, to provide technical support for the literature searches conducted by the Committee. HHS and ICF staff collaborated with the Committee in the design and conduct of the searches by assisting with the development of the analytical frameworks, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and search terms for each primary question; using those parameters, ICF performed the literature searches.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This paper is being published as an official pronouncement of the American College of Sports Medicine. This pronouncement was reviewed for the American College of Sports Medicine by members-at-large and the Pronouncements Committee. Disclaimer: Care has been taken to confirm the accuracy of the information present and to describe generally accepted practices. However, the authors, editors, and publisher are not responsible for errors or omissions or for any consequences from application of the information in this publication and make no warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the currency, completeness, or accuracy of the contents of the publication. Application of this information in a particular situation remains the professional responsibility of the practitioner; the clinical treatments described and recommended may not be considered absolute and universal recommendations.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haskell WL. Physical activity and health: Need to define the required stimulus. Am J Cardiol. 1985;55(10):D4–D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebisu T Splitting the distances of endurance training: on cardiovascular endurance and blood lipids. Jap J Phys Educ. 1985;30:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN et al. Physical activity and public health: a recommendation from the Centers for Disease and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA. 1995;273(5):402–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haskell WL, Lee I-M, Pate RR et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1423–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services. 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Church TS, Thomas DM, Tudor-Locke C et al. Trends over 5 decates in U.S. occupation-related physical activity and their associations with obesity. PLos One. 2011;6(5):e19657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torres A, Tennant B, Ribeiro-Lucas I, Vaux-Bjerke A, Piercy K, Bloodgood B. Umbrella and systematic review methodology to support the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Committee. J Phys Act Health. 2018;15(11): 805–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Nutrition Evidence Library Methodology. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alizadeh Z, Kordi R, Rostami M, Mansournia MA, Hosseinzadeh-Attar SMJ, Fallah J. Comparison between the effects of continuous and intermittent aerobic exercise on weight loss and body fat percentage in overweight and obese women: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4(8):881–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asikainen TM, Miilunpalo S, Kukkonen-Harjula K et al. Walking trials in postmenopausal women: effect of low doses of exercise and exercise fractionization on coronary risk factors. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2003;13(5):284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asikainen T-M, Miilunpalo S, Oja P, Rinne M, Pasanen M, Vuori I. Walking trials in postmenopausal women: effect of one vs two daily bouts on aerobic fitness. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2002;12(2):99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayabe M, Kumahara H, Morimura K, Ishii K, Sakane N, Tanaka H. Very short bouts of non-exercise physical activity associated with metabolic syndrome under free-living conditions in Japanese female adults. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(10):3525–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayabe M, Kumahara H, Morimura K, Sakane N, Ishii K, Tanaka H. Accumulation of short bouts of non-exercise daily physical activity is associated with lower visceral fat in Japanese female adults. Int J Sports Med. 2013;34(1):62–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cameron N, Godino J, Nichols JF, Wing D, Hill L, Patrick K. Associations between physical activity and BMI, body fatness, and visceral adiposity in overweight or obese Latino and non-Latino adults. Int J Obes (Lond). 2017;41(6):873–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke J, Janssen I. Sporadic and bouted physical activity and the metabolic syndrome in adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(1):76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Blasio A, Bucci I, Ripari P et al. Lifestyle and high density lipoprotein cholesterol in postmenopause. Climacteric. 2014;17(1):37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donnelly JE, Jacobsen DJ, Heelan KS, Seip R, Smith S. The effects of 18 months of intermittent vs continuous exercise on aerobic capacity, body weight and composition, and metabolic fitness in previously sedentary, moderately obese females. Int J Obes Relat Metab Dis. 2000;4(5):566–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eguchi M, Ohta M, Yamato H. The effects of single long and accumulated short bouts of exercise on cardiovascular risks in male Japanese workers: a randomized controlled study. Ind Health. 2013;51(6):563–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan JX, Brown BB, Hanson H, Kowaleski-Jones L, Smith KR, Zick CD. Moderate to vigorous physical activity and weight outcomes: does every minute count? Am J Health Promot. 2013;28(1):41–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gay JL, Buchner DM, Schmidt MD. Dose-response association of physical activity with HbA1c: intensity and bout length. Prev Med. 2016;86:58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glazer NL, Lyass A, Esliger DW et al. Sustained and shorter bouts of physical activity are related to cardiovascular health. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(1):109–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakicic JM, Wing RR, Butler BA, Robertson RJ. Prescribing exercise in multiple short bouts versus one continuous bout: effects on adherence, cardiorespiratory fitness, and weight loss in overweight women. International Journal of Obesity. 1995;19:893–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jakicic JM, Winters C, Lang W, Wing RR. Effects of intermittent exercise and use of home exercise equipment on adherence, weight loss, and fitness in overweight women: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1554–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jefferis BJ, Parsons TJ, Sartini C et al. Does duration of physical activity bouts matter for adiposity and metabolic syndrome? A cross-sectional study of older British men. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13(36):DOI 10.1186/s12966-016-0361-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loprinzi PD, Cardinal BJ. Association between biologic outcomes and objectively measured physical activity accumulated in ≥10-minute bout and <10-minute bouts. Am J Health Promot. 2013;27(3):143–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murtagh EM, Boreham CA, Nevill A, Hare LG, Murphy MH. The effects of 60 minutes of brisk walking per week, accumulated in two different patterns, on cardiovascular risk. Prev Med. 2005;41(1):92–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quinn TJ, Klooster JR, Kenefick RW. Two short, daily activity bouts vs. one long bout: are health and fitness improvements similar over twelve and twenty-four weeks? Journal of strength and conditioning research / National Strength & Conditioning Association. 2006;20(1):130–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt WD, Biwer CJ, Kalscheuer LK. Effects of long versus short bout exercise on fitness and weight loss in overweight females. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20(5):494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strath SJ, Holleman RG, Ronis DL, Swartz AM, Richardson CR. Objective physical activity accumulation in bouts and nonbouts and relation to markers of obesity in US adults. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(4):https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2008/oct/07_0158.htm. Accessed October 6, 2017. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vasankari V, Husu P, Vaha-Ypya H et al. Association of objectively measured sedentary behaviour and physical activity with cardiovascular disease risk. European journal of preventive cardiology. 2017;24(12):1311–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White DK, Pettee Gabriel K, Kim Y, Lewis CE, Sterfeld B. Do short spurts of physical activity benefit health? The CARDIA Study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(11):2353–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolff-Hughes DL, Fitzhugh EC, Bassett DR, Churilla JR. Total activity counts and bouted minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity: relationships with cardiometabolic biomarkers using 2003–2006 NHANES. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12:694–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woolf-May K, Kearney EM, Owen A, Jones DW, Davison RC, Bird SR. The efficacy of accumulated short bouts versus single daily bouts of brisk walking in improving aerobic fitness and blood lipid profiles. Health Educ Res. 1999;14(6):803–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White DK, Gabriel KP, Kim Y, Lewis CE, Sternfeld B. Do short spurts of physical activity benefit cardiovascular health? The CARDIA Study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(11):2353–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chung J, Kin K, Kong H-J. Effects of prolonged exercise versus multiple short exercise sessions on risk for metabolic syndrome and the atherogenic index in middle-aged obese women: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Women’s Health. 2017;17:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saint-Maurice PF, Troiano RP, Matthews CE, Kraus WE. Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and all-cause mortality: do bouts matter? J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e007678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kehler DS, Clara I, Hiebert B et al. The association between bouts of moderate to vigorous physical activity and patterns of sedentary behavior with frailty. Exp Gerontol. 2018;104:28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loprinzi PD. Associations between bouted and non-bouted activity on multimorbidity. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2017;37(6):782–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cameron N, Nichols JF, Hill L, Patrick K. Associations betweeen physical activity and BMI, body fatness, and visceral adiposity in overweight or obese Latino and non-Latino adults. International Journal of Obesity. 2017;41:873–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2735–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Association; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1640–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]