Abstract

BACKGROUND

Heart rate variability (HRV) declines after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of low-volume high-intensity interval training (LV-HIIT) and moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) on HRV as well as, hemodynamic and echocardiography indices.

METHODS

Forty-two men after CABG (55.12 ± 3.97 years) were randomly assigned into LV-HIIT, MICT, and control (CTL) groups. The exercise training in LV-HIIT consisted of 2-minute interval at 85-95 percent of maximal heart rate (HRmax), 2-minute interval at 50% of HRmax and 40-minute interval at 70% of HRmax in MICT for three sessions in a week, for 6-weeks. HRV parameters were evaluated by 24-hour Holter electrocardiography (ECG) recording, and echocardiography parameters at baseline and end of intervention were measured in all 3 groups.

RESULTS

At the end of the intervention, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) significantly increased in LV-HIIT group (58.53 ± 7.26 percent) compared with MICT (52.26 ± 7.91 percent) and CTL (49.68 ± 7.27 percent) groups (P < 0.001). Furthermore, mean R-R interval, root mean square successive difference (RMSSD) of R-R interval, and standard deviation of R-R interval (SDRR) in LV-HIIT group considerably increased compared with MICT group (P < 0.001). High-frequency power (HF) significantly increased in LV-HIIT and MICT groups compared with CTL group (P < 0.001). On the other hand, low frequency (LF) and LF/HF ratio significantly decreased in LV-HIIT group in comparison with MICT group (P < 0.010).

CONCLUSION

These results suggest that LV-HIIT has a greater effect on improvement of cardiac autonomic activities by increasing R-R interval, SDRR, RMSSD, and HF, and decreasing LF and LF/HF ratio in patients after CABG.

Keywords: High-Intensity Interval Training, Continuous Training, Cardiac Rehabilitation, Cardiac Autonomic Activity

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the major causes of death in the world.1 Patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) are at risk for life-threatening arrhythmias and sudden death. In patients with CAD, alterations in cardiac autonomic control, that are characterized by relative increase in sympathetic activity and decline of vagal modulation, play a major role in the occurrence of arrhythmic events.2,3 The variation of the time intervals between consecutive heartbeats or the instantaneous heart rates is called heart rate variability (HRV). HRV is a non-invasive method for assessing autonomic activity and providing information about heart’s ability to respond to the normal regulatory impulses, vagal modulation, and sympathovagal interactions.4 Cardiac autonomic dysfunction, as evidenced by low HRV, has strong detrimental effects on subsequent clinical outcome in patients with CAD.5 Low HRV is associated with all-cause mortality and increased risk of sudden cardiac death after myocardial infarction (MI).3,5

Some studies indicate that HRV significantly decreases in patients after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery, a condition that is even riskier than that of patients with MI.6 Cardiac autonomic nerves are permanently damaged after CABG surgery, leading to impairment of cardiac parasympathetic modulation.7 In contrast, many studies have demonstrated that exercise training has numerous benefits, including improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness, exercise capacity, cardiovascular risk factors, and endothelial function.8-10 Aerobic exercise training is a well-established means of improving autonomic function (through enhancing vagal, and reducing sympathetic cardiac modulation) in patients with MI, heart failure, and CABG.11-13

Murad et al. reported significantly greater increase in root mean square successive difference (RMSSD) of R-R interval and standard deviation of R-R interval (SDRR) in elderly patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) after 16-weeks of moderate intensity training, which represented improved HRV induced-exercise training.14 Another study reported that low-intensity exercise has a minimal adaptive effect on cardiac parasympathetic modulation after CABG surgery.15 These findings suggest that exercise rehabilitation program may be used to improve HRV in CVD. However, the optimal dose of exercise, defined as the volume and intensity of exercise for improvement in cardiac autonomic regulation, is a crucial issue that is not fully understood.16,17

Aerobic exercise training is the cornerstone of exercise training programs which beneficial effects of aerobic exercise training in cardiac autonomic regulation as well as, physiological and clinical parameters in patients with CVD is known.18 Recent studies have indicated that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) has a superior effect on exercise capacity, endothelial function, and quality of life than moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) in healthy subjects and patients with CHF/CAD.19-21 HIIT consists of alternating periods of high-intensity exercise involving 30-300-second bouts of aerobic exercise at 85-100 percent of maximum rate of oxygen consumption (VO2max) that are separated with periods of low-intensity exercise of equal or shorter duration, to allow patients to allocate greater time to high-intensity rather than continuous exercise.22 It has been shown that a single session of HIIT improves cardiac autonomic function in healthy trained and non-trained people, as well as patients with CHF.22,23 Various HIIT protocols (with difference in intensity, stage duration, nature of the recovery, and number of intervals) may have different impacts on patients with CAD. The parameters of HIIT, including work/recovery intensity and interval duration, are important factors in training effectiveness, because manipulating these parameters alters time of exercise at a high percentage of VO2peak.19 Existing studies have demonstrated that both long- and short-duration HIIT protocols are safe, and have beneficial effects on cardiopulmonary fitness in patients with CAD and CHF.21,24,25 The mechanisms of the HIIT affecting HRV in patients with CABG are not completely clear so far. Nonetheless, there is little evidence about the effect of exercise intensity on HRV, and hemodynamic and echocardiography indices in the patients after CABG.

In the present study, we hypothesized that low-volume high-intensity interval training (LV-HIIT) may improve HRV in patients with CABG even more than MICT. To test our hypothesis, we assessed 24-hour HRV, as well as hemodynamic and echocardiography indices in patients after CABG.

Materials and Methods

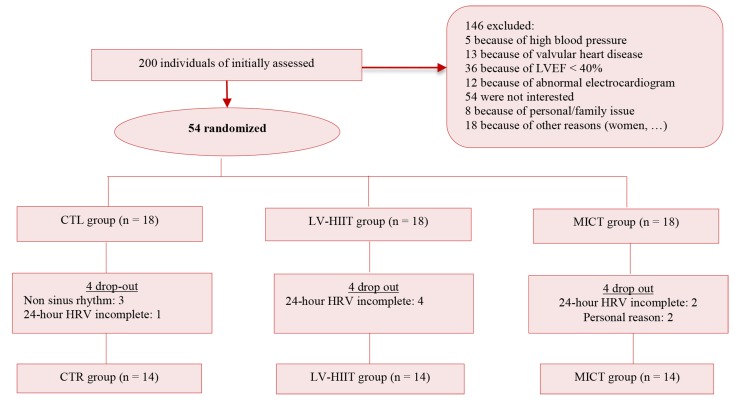

Participants were recruited from cardiovascular rehabilitation center of Baqiyatallah hospital in Tehran, Iran, in January-March 2016. At the beginning of the study, 200 post-CABG men were enrolled by responsible supervisor and researchers in the rehabilitation center. Inclusion criteria were as aging 50-70 years, being male, in sinus rhythm, and having CABG surgery during past 6 weeks. Furthermore, they should have left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥ 40% measured at least 6 weeks after the surgery. The subjects were excluded if they had peripheral vascular disease, ventricular premature beats or other arrhythmias, conduction defects, history of pacemaker insertion, significant valvular heart disease, arterial blood pressure (BP) > 180/100 mmHg, or functional limitations (such as osteoarthritis). The subjects were randomly assigned to one of the three groups of LV-HIIT (n = 14), MICT (n = 14) and control (CTL) (n = 14). Randomization was done by block randomization with the block size of 4 (Figure 1). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before participation in the study.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participant LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction; CTL: Control; LV-HIIT: Low-volume high-intensity interval training; MICT: Moderate intensity continuous training; HRV: Heart rate variability.

The present study protocol was approved by the Ethic Committee of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration, and is registered at Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20150701223002N1).

This study investigated the effect of interval exercise training and continuous exercise training on HRV in post-CABG men. Maximal heart rate (HRmax), resting heart rate (HRrest), resting diastolic BP (DBP), resting systolic BP (SBP), LVEF, end-systolic and diastolic volumes (ESV and EDV, respectively), and ambulatory HRV were measured at the beginning and end of the six-week exercise training. Resting BP and HRrest were measured in supine position, at the beginning and at the end of study before starting exercise, using digital Sphygmomanometer (Beurer GmbH, Soflinger Str.218, D-89077 Ulm, BM 75; Germany). Participants’ height and weight were measured using a stadiometer (GMP, Switzerland) and digital, medical scale (Radwage WPT 100/200, Poland), respectively, while subjects were wearing light clothes and had taken off their shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated through dividing weight by square root of height (kg/m2). Echocardiograms were checked for checking the existence of arrhythmias. After measurement of variables at the baseline, participants were informed about the exercise protocols in an orientations session. To minimize risks of exercise, protocols were performed under the supervision of a cardiologist. Moreover, patients were requested to report any problems and complications, such as chest pain and breathlessness, during exercise.

All subjects were asked to refrain from strenuous physical activities, and the consumption of caffeine and tobacco for 24 hours before exercise test. Subjects’ last meal was ingested at least 2 hours before the beginning of the exercise. The exercise test was performed on ergometer (3G cardio Elite Runner, Phoenix, AZ, USA) with a 12-lead continuous electrocardiography (ECG) monitoring in a room with controlled temperature (24 to 26 °C) between 9:00-17:00. One week before the exercise test, all participants underwent a similar exercise test that consisted of short duration and low intensity in order to get them familiarized with the testing procedures. The workload of incremental cycle exercise test was initially set at 30 watts, for 2 minutes, and power output increased every 1 minute by 10 watts until the subjects could not continue and maintained on a fixed pedaling frequency of 40 rpm. HRrest was measured as the mean of the 30 seconds of the resting period in the supine position. HRmax was also computed during the last 30 seconds of exercise test before exhaustion.

All subjects performed the exercise training program three times a week for 6 weeks (between 09:00-11:00). Exercise training was monitored by an exercise physiologist. A polar S810 HR monitor was connected to patients for measuring beat-to-beat HR during exercise. Each exercise training session consisted of 5 minutes of warm-up that included walking, running, and stretching movements up to 40% of HRmax. MICT session training consisted of 40 min running on a treadmill (Technogym, Italy) at 70% HRmax. Each LV-HIIT session followed by 10 intervals of 2 minutes at 85-95 percent of HRmax, and separated by 2 minutes at 50% of HRmax. The training session ended by a cool-down period that was 5 minutes at 40% of HRmax.

Exercise intensity was determined based on workload reaching during the exercise test. The cardiovascular workloads of the two programs were calculated to promote the same workload. MICT included 40 minutes at 70% of HRmax on the treadmill. LV-HIIT resulted in a mean workload of 70% HRmax [(10 × 2 × 90%) + (10 × 2 × 50%)]/40, (Repeated interval × time of exercise × percent of HRmax in high-intensity periods + repeated interval × time of exercise × percent of HRmax in low-intensity periods/total time of exercise).

The treadmill velocity was continually adjusted as along as training adaptions occurred, a move to ensure that every training session was carried out at the desired HRmax throughout the 6-weeks training period. The control group subjects were encouraged to maintain their daily activities without exercise training during the 6-weeks period. Additionally, subjects in three groups were advised to follow their normal food intake pattern during the intervention.

24-hour ECG monitoring was performed at the baseline and 48 hours after the end of last sessions. Ambulatory ECG recordings were obtained from a 3-channel Medilog Digital Holter recorder FD3, Oxford, with 1024 Hz sampling rate. HRV was analyzed by computer and a commercial system (Oxford Instruments, with Excel ECG Replay System-Rel 8.5). The MT-210 Analysis Software Version 1.0.0 (Schiller) was used to analyze SDRR, RMSSD, low-frequency power (LF), high-frequency power (HF), and the LV/HF ratio. Subjects were requested to maintain their normal daily activities, and to avoid caffeine, smoking, and walking/running during the recording. An experienced technician who was blinded to subjects’ information analyzed the recordings. All HRV variables were measured. If the variables were recorded for less than 20 hour, the subject was excluded from the study.4

M-mode, Doppler, and two-dimension echocardiography were performed at baseline and end of the study using a GE Vivid 3 device, and a 3 MHz phased-array transducer, respectively, by a single experienced cardiologist who was blinded to patients groups. The measurements of the echocardiography included left ventricular end diastolic dimension (LVEDD), left ventricular end-systolic dimension (LVESD), EDV, ESV, EF, LVEF was calculated based on the following formula: (LVEDD2 - LVESD2)/LVEDD2 measured in the left lateral decubitus according to the guidelines of the American Society of Echocardiography.26

Data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical software (version 16.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and the continues and categorical variables were reported by mean ± standard deviation (SD) and absolute number (percent) respectively. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used for evaluating normality of distribution. Moreover, chi-square was conducted for analyzing categorical variables. One-way ANOVA was further carried out in order to assess the difference between groups with regard to clinical characteristics of subjects at baseline and heart changes variables in three groups. To compare the changes in all research variables in three groups (CTL, LV-HIIT, and MICT), the differences between values before and after exercise in each groups were calculated and compared by using the one-way ANOVA. Moreover, Bonferroni and Games-Howell tests were used as a post-hoc to determine differences between groups, respectively. Paired t-test was used for evaluating the difference of variables between pre and post. The level of significance in all statistical analyses was set at P < 0.050.

Results

Subject characteristics: Out of the 200 patients who were assessed for eligibility, 54 met the inclusion criteria, so were randomly assigned into the three groups. Seven patients were excluded from the study, because the data of 24-hour Holter were incomplete. Three participants of the CTL group had non sinus rhythm, hence their data were excluded from analysis, too. Two patients withdrew consent for reasons unrelated to their clinical status (Figure 1). There was no drop out subjects during the exercise training period. During the study period, medication of subjects did not change. At the baseline, one way-ANOVA revealed that the three groups demonstrated no significant difference in age, weight, height, BMI, medical history, and medications (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics and medication of studied groups

| Variable | Group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTL (n = 14) |

LV-HIIT (n = 14) |

MICT (n = 14) |

P | |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| Age (year) | 58.80 ± 4.41 | 53.90 ± 3.44 | 54.10 ± 4.02 | 0.565 |

| Weight (kg) | 84.14 ± 6.66 | 82.73 ± 4.86 | 83.47 ± 6.14 | 0.235 |

| Height (cm) | 175.90 ± 4.95 | 176.8 ± 4.02 | 177.00 ± 4.89 | 0.882 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.18 ± 1.70 | 26.49 ± 1.88 | 26.61 ± 1.13 | 0.518 |

| Time after surgery (week) | 8.13 ± 1.60 | 9.40 ± 2.85 | 7.86 ± 1.23 | 0.267 |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Hypertension | 4 (28.5) | 5 (35.7) | 3 (21.4) | 0.450 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (42.8) | 3 (21.4) | 3 (21.4) | 0.285 |

| Medication | ||||

| β-blockers | 3 (21.4) | 4 (28.5) | 5 (35.7) | 0.340 |

| ACE inhibitors | 4 (28.5) | 3 (21.4) | 3 (21.4) | 0.310 |

| Diuretics | 4 (28.5) | 3 (21.4) | 2 (14.3) | 0.270 |

| Statins | 2 (14.3) | 3 (21.4) | 4 (28.5) | 0.281 |

SD: Standard deviation; BMI: Body mass index; ACE: Angiotensin converting enzyme; CTL: Control; LV-HIIT: Lowvolume high-intensity interval training; MICT: Moderate-intensity continuous training

Baseline levels of anthropometric and clinical variables examined using one-way ANOVA and chi-square, respectively.

Hemodynamic and echocardiography: The values of hemodynamic and echocardiography indices are displayed in table 2. No baseline difference was detected between the groups with regard to DBP, SBP, HRmax, HRrest, LVEF, EDV, ESV, LVEDD, and LVESD (P < 0.050 for all). Results of the one-way ANOVA indicated that DBP and SBP significantly decreased in LV-HIIT and MICT groups compared with CTL group (P < 0.010). Post-hoc analysis indicated that DBP had greater decrease in the LV-HIIT group compared with MICT group (P < 0.050). Moreover, changes of the SBP in LV-HIIT group had a greater decrease compared with MICT group (P < 0.050). At the end of intervention, HRmax significantly increased in exercise groups (P < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis indicated that change of HRmax in the LV-HIIT group had a greater increase compared with MICT group (P < 0.050). HRrest significantly decreased after 6-weeks exercise training (P < 0.010). Post-hoc analysis showed that change of HRrest in LV-HIIT group had a greater decrease compared with MICT group (P < 0.050). The result showed that LVEF increased after 6-weeks exercise training in both groups (P < 0.005). However, the post-hoc analysis showed that LVEF more significantly increased in LV-HIIT group compared with MICT group (P < 0.050). EDV and ESV after 6-weeks exercise training significantly increased and decreased, respectively. The post-hoc analysis demonstrated that LV-HIIT had a greater effect in increase and decrease of EDV and ESV, respectively (P < 0.010, P < 0.050). There was no significant difference in LVEDD and LVESD at the end of study.

Table 2.

Baseline and follow-up of hemodynamic and echocardiography

| Variable | Group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTL (n = 14) | LV-HIIT (n = 14) | MICT (n = 14) | P | ||

| DBP (mm Hg) | Baseline | 81.70 ± 11.62 | 82.80 ± 11.37 | 83.80 ± 11.84 | 0.913 |

| After intervention | 82.90 ± 10.81 | 80.10 ± 9.70* | 80.60 ± 10.78* | 0.041 | |

| P (from paired t-test) | 0.423 | 0.034 | 0.012 | ||

| Change | 1.20 ± 2.69 | -3.20 ± 2.69* | -2.70 ± 2.21* | < 0.010 | |

| SBP (mm Hg) | Baseline | 135.10 ± 18.94 | 138.50 ±18.05 | 136.30 ± 17.02 | 0.922 |

| After intervention | 136.30 ± 16.36 | 122.80 ± 13.55** | 125.90 ± 21.10* | 0.019 | |

| P (from paired t-test) | 0.278 | 0.005 | 0.023 | ||

| Change | 1.20 ± 3.67 | -15.70 ± 7.54**# | -6.10 ± 5.44* | 0.013 | |

| HRmax (beat/minute) | Baseline | 128.80 ± 22.23 | 121.10 ± 20.12 | 125.90 ± 21.10 | 0.217 |

| After intervention | 127.60 ± 23.24 | 128.60 ± 22.17 | 128.40 ± 19.65 | 0.823 | |

| P (from paired t-test) | 0.238 | 0.003 | 0.026 | ||

| Change | -1.20 ± 3.90 | 7.50 ± 4.46**# | 2.50 ± 4.26 * | 0.005 | |

| HRrest (beat/minute) | Baseline | 80.50 ± 12.27 | 80.10 ± 13.73 | 83.10 ± 12.25 | 0.851 |

| After intervention | 80.20 ± 11.15 | 72.10 ± 12.86 | 78.50 ± 12.28 | 0.194 | |

| P (from paired t-test) | 0.783 | 0.001 | 0.031 | ||

| Change | -0.30 ± 2.71 | -8.00 ± 2.62**# | -4.60 ± 1.50* | < 0.010 | |

| LVEF (%) | Baseline | 48.14 ± 7.25 | 52.06 ± 7.04 | 48.67 ± 6.69 | 0.410 |

| After intervention | 49.68 ± 7.27 | 58.53 ± 7.26**# | 52.26 ± 7.91* | 0.034 | |

| P (from paired t-test) | 0.198 | 0.007 | 0.042 | ||

| Change | 1.53 ± 0.74 | 6.46 ± 3.76*# | 3.59 ± 3.73 | 0.005 | |

| EDV (ml) | Baseline | 116.20 ± 27.54 | 128.20 ± 36.23 | 117.60 ± 32.51 | 0.660 |

| After intervention | 117.10 ± 26.61 | 135.30 ± 35.90**# | 123.30 ± 33.62* | 0.013 | |

| P (from paired t-test) | 0.385 | 0.002 | 0.021 | ||

| Change | 0.90 ± 2.18 | 7.10 ± 3.75** | 5.70 ± 2.71* | < 0.010 | |

| ESV (ml) | Baseline | 59.10 ± 10.97 | 59.30 ± 10.12 | 58.80 ± 11.38 | 0.995 |

| After intervention | 57.80 ± 10.39 | 54.10 ± 10.35* | 57.20 ± 11.27 | 0.045 | |

| P (from paired t-test) | 0.128 | 0.001 | 0.041 | ||

| Change | -1.30 ± 1.25 | -5.20 ± 4.13*# | -1.60 ± 4.03 | 0.029 | |

| LVEDD (mm) | Baseline | 49.60 ± 6.43 | 51.10 ± 8.58 | 50.00 ± 8.37 | 0.910 |

| After intervention | 50.30 ± 6.43 | 53.00 ± 8.88 | 51.00 ± 8.96 | 0.338 | |

| P (from paired t-test) | 0.589 | 0.098 | 0.123 | ||

| Change | 0.70 ± 1.33 | -1.90 ± 0.99 | -1.00 ± 1.49 | 0.116 | |

| LVESD (mm) | Baseline | 33.30 ± 9.44 | 34.80 ± 8.59 | 31.20 ± 8.30 | 0.657 |

| After intervention | 34.20 ± 9.25 | 33.70 ± 8.40 | 30.90 ± 8.00 | 0.398 | |

| P (from paired t-test) | 0.612 | 0.510 | 0.467 | ||

| Change | 0.90 ± 2.51 | -1.10 ± 2.28 | -0.30 ± 1.70 | 0.141 | |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

CTL: Control; LV-HIIT: Low-volume high-intensity interval training; MICT: Moderate-intensity continuous training; SBP: Systolic blood pressure; DBP: Diastolic blood pressure; HRmax: Maximal heart rate; HRrest: Resting heart rate; LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction; EF: Ejection fraction; EDV: End-diastolic volume; ESV: End-systolic volume; LVEDD: Left ventricular end diastolic dimension; LVESD: Left ventricular end systolic dimension

One-way ANOVA was used for evaluating difference between groups (post-hoc test).

P < 0.050 compared to CTL group;

P < 0.010 compared to CTL group;

P < 0.050 compared to MICT group

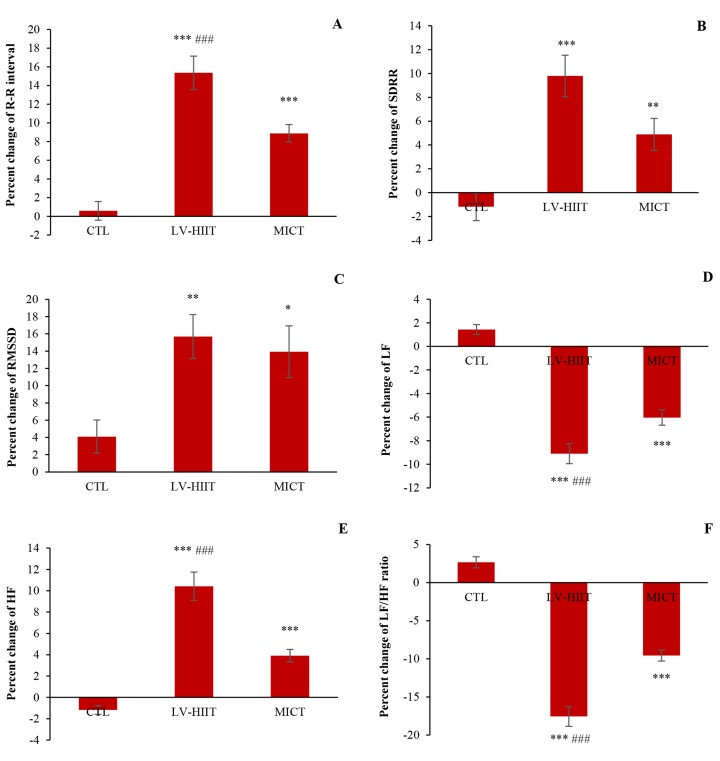

Heart rate variability: Baseline and follow-up HRV data are shown in table 3. The results of one-way ANOVA showed that mean R-R interval following the 6-weeks intervention increased in both exercise groups (P < 0.010). Post-hoc analysis showed that mean R-R interval increased considerably in LV-HIIT and MICT groups compared with CTL group (P < 0.010). Paired t-test analysis of mean R-R interval in LV-HIIT and MICT groups was more than post-hoc test (P < 0.010). Furthermore, percent changes of mean R-R interval had a greater increase in LV-HIIT group compared with MICT group (P < 0.001) (Figure 2-A). There was also a significant increase for SDRR after 6-weeks in both exercise groups (P < 0.010) (Table 3). The paired t-test showed that SDRR increased in posttest of LV-HIIT (P < 0.010) and MICT (P < 0.050) groups compared with pretest. Although, percent change in SDRR increased after exercise intervention, percent change in LV-HIIT group more increased than MICT group (P < 0.001) (Figure 2-B). RMSSD demonstrated a significant increase in both groups after 6-weeks intervention (P < 0.050). There was no significant difference for changes of RMSSD between LV-HIIT and MICT groups (Table 3). The percent change of RMSSD increased more profoundly in LV-HIIT group compared with CTL group (P = 0.050) (Figure 2-C). The paired t-test showed that RMSSD increased in posttest of LV-HIIT and MICT (P < 0.050) groups compared with pretest. Similarly, there was a significantly increase in terms of HF after 6 weeks in both exercise groups (P < 0.010).

Table 3.

Baseline and follow-up parameters of heart rate variability (HRV)

| Variable | Group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTL (n = 14) | LV-HIIT (n = 14) | MICT (n = 14) | P | ||

| Mean R-R interval (ms) | Baseline | 818.70 ± 104.24 | 864.00 ± 113.56 | 837.90 ± 111.90 | 0.657 |

| After intervention | 824.00 ± 112.03 | 997.00 ± 142.43**# | 912.50 ± 127.36** | 0.010 | |

| P (from paired t-test) | 0.345 | 0.001 | 0.010 | ||

| Change | 5.30 ± 25.86 | 133 ± 55.14**## | 74.60 ± 29.11** | < 0.010 | |

| SDRR (ms) | Baseline | 83.70 ± 28.26 | 91.30 ± 29.43 | 91.60 ± 30.39 | 0.794 |

| After intervention | 83.00 ± 28.97 | 99.30 ± 28.70** | 95.30 ± 29.35** | 0.028 | |

| P (from paired t-test) | 0.913 | 0.001 | 0.023 | ||

| Change | -0.70 ± 2.54 | 8.00 ± 3.43**# | 3.70 ± 2.40* | < 0.010 | |

| RMSSD (ms) | Baseline | 38.30 ± 16.89 | 42.20 ± 17.37 | 43.70 ± 17.26 | 0.770 |

| After intervention | 39.40 ± 16.99 | 47.70 ± 16.76** | 48.50 ± 15.77** | 0.019 | |

| P (from paired t-test) | 0.434 | 0.018 | 0.025 | ||

| Change | 1.10 ± 1.59 | 5.50 ± 1.43* | 4.80 ± 2.14* | < 0.050 | |

| HF (ms) | Baseline | 124.03 ± 38.16 | 131.52 ± 33.24 | 132.80 ± 41.71 | 0.943 |

| After intervention | 122.50 ± 37.63 | 144.80 ± 34.60**# | 137.50 ± 41.99** | 0.011 | |

| P (from paired t-test) | 0.273 | 0.006 | 0.034 | ||

| Change | -1.50 ± 1.50 | 13.30 ± 5.29**## | 4.70 ± 1.33* | < 0.010 | |

| LF (ms) | Baseline | 252.62 ± 69.83 | 244.42 ± 61.48 | 242.61 ± 75.61 | 0.855 |

| After intervention | 255.80 ± 69.49 | 222.30 ± 57.64** | 227.70 ± 70.57** | 0.039 | |

| P (from paired t-test) | 0.561 | 0.008 | 0.003 | ||

| Change | 3.20 ± 2.57 | -22.10 ±7.72**# | -14.90 ± 6.83** | 0.012 | |

| LF/HF ratio | Baseline | 2.34 ± 1.18 | 2.08 ± 1.04 | 2.21 ± 1.40 | 0.900 |

| After intervention | 2.39 ± 1.20 | 1.72 ± 0.89**# | 1.98 ± 1.22** | 0.041 | |

| P (from paired t-test) | 0.673 | 0.018 | 0.029 | ||

| Change | 0.53 ± 0.05 | -0.36 ± 0.17* | -0.23 ± 0.18* | 0.023 | |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

CTL: Control; LV-HIIT: Low-volume high-intensity interval training; MICT: Moderate-intensity continuous training; SDRR: Standard deviation of all R-R intervals; RMSSD: Root mean square of difference between successive R-R intervals; LF: Lowfrequency power; HF: High-frequency power

One-way ANOVA was used for evaluating difference between groups (post-hoc test).

P < 0.050 compared to CTL group;

P < 0.010 compared to CTL group;

P < 0.050 compared to MICT group;

P < 0.010 compared to MICT group

Figure 2.

Heart rate variability (HRV) assay demonstrated that exercise intervention for 6 weeks improved HRV in post-CABG men. A) Percent change of mean R-R interval; B) Percent change of standard deviation of R-R interval (SDRR); C) Percent change of root mean square difference of successive (RMSSD); D) Percent change of highfrequency power (HF); E) Percent change of low-frequency power (LF); F) Percent change of LF/HF ratio. CTL: Control; LV-HIIT: Low-volume high-intensity interval training; MICT: Moderate intensity continuous training; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting One-way ANOVA was used for evaluating difference between groups in percent changes. * P < 0.050 compared to CTL group; ** P < 0.010 compared to CTL group; *** P < 0.001 compared to CTL group; ### P < 0.001 compared to LV-HIIT group

HF increased in the exercise groups compared with CTR group (P < 0.010). Post-hoc analysis showed a significant greater enhancement in the changes of HF in LV-HIIT group compared to MICT group (P < 0.010). In addition, the percent change of HF in LV-HIIT group increased more than MICT group (Figure 2-D). The paired t-test showed that HF increased in posttest of LV-HIIT (P<0.010) and MICT (P<0.050) groups compared with pretest. After the 6-weeks exercise intervention, LF decreased in the exercise groups (P < 0.050). Post-hoc analysis revealed a significant increase in the changes and percent changes of LF in the LV-HIIT group compared with MICT group (P < 0.050) (Table 3, Figure 2-E). The paired t-test showed that LF increased in posttest of LV-HIIT and MICT groups (P < 0.010) compared with pretest. The LF/HF ratio following exercise intervention significantly reduced in the exercise groups (P < 0.050). Post-hoc analysis showed that the percent change of LF/HF ratio significantly reduced in the LV-HIIT group compared to MICT group (P < 0.001) (Figure 2-F). The paired t-test showed that SDRR increased in posttest of LV-HIIT and MICT groups (P < 0.050) compared with pretest.

Discussion

The findings of the present study indicate that a 6-weeks HIIT improves HRV in post-CABG men. To our knowledge, this study is the first to assess the effects of LV-HIIT protocol on HRV-parameters in these patients. This study show that, compared with MICT and control, LV-HIIT induces a greater improvement in the time domain indices (i.e. SDRR and RMSSD) in patients with CABG.

HIIT also results in HF enhancement and decline of LF and LF/HF ratio power. Additionally, LVEF and hemodynamic indices (SBP and DBP) improved significantly among subjects in LV-HIIT group compared with those of participants in MICT and CTL groups.

There was a significant increase in LVEF after 6 weeks of exercise training in the exercise groups compared with the CTL group. The post-hoc analysis revealed that this significant increase in LV-HIIT group was greater than MICT group. Exercise training improved LVEF in cardiovascular disease, though the mechanisms are unclear. Improved EF-induced HIIT may be attributed to attenuation in pathological remodeling and increase in ventricular compliance. In addition, it is demonstrated that structural changes in the heart led to increased LVEF.21 This study demonstrated that exercise training results in significant decrease in LVEDD and LVESD. It also revealed that the decrease of LVESD in LV-HIIT could cause greater increase of LVEF compared with MICT.

After HIIT training, HRrest significantly declined. These results are similar to those of other studies that have also reported aerobic exercise-induced bradycardia.27 Although the mechanism of bradycardia induced by aerobic exercise is unclear, it seems that bradycardia-induced HIIT reflects a combination of reduced intrinsic heart rate, decreased sympathetic tone, and increased parasympathetic tone.28 Katona et al. have demonstrated that endurance training in athletes and non-athletes leads to a reduction in intrinsic heart rate.27 A previous study showed that 12 weeks of HIIT could decrease HRrest in healthy men. This indicates that HIIT may increase cardiac performance by increasing cardiac dilation during exercise in young subjects. It seems that, increase of EDV contributes to the increase of SV and decline of HRrest; however, the increase of SV induced-increased myocardial contractility at rest appears to be a more likely.28 A previous study has demonstrated that different types of exercise training may improve HRV in patients with CAD.29 One of the candidate beneficial mechanisms of exercise is effects of autonomic nervous system, with numerous studies indicating that parasympathetic function improves after aerobic exercise training.20,30,31 In CAD, low HRV is a predictor of morbidity and mortality. According to Bilchick et al., the increase of 10 ms in SDRR was associated with 20% decrease in the risk of mortality.32 Exercise training could prevent CVD mortality by increasing SDRR. The result of this study indicate that HIIT is effective in improving cardiac autonomic modulation. LV-HIIT leads to enhancement of SDRR, RMSSD, and HF. Conversely, it decreases LF and LF/HF ratio in post-CABG. It seems that LV-HIIT has a greater effect in patients with CAD. Previous studies have demonstrated that short intervals of HIIT had a higher mean intensity and extracted higher perceived exertion (RPE) which was associated with lower exercise session compliance for CVD.22,24

A research showed that optimized HIIT protocols were associated with lower mean VO2, lower ventilation, lower RPE, and higher exercise session compliance. Thus, HIIT with short intervals is well tolerated by patients with CAD, and leads to greater increase of VO2peak.33 The reduction of HRrest in the patients after HIIT is directly correlated with vagal modulation, which was assessed through the increase in HF power. RMSSD increase in the exercise groups indicates a decline in sympathetic nervous activity, and a potential mechanistic shift toward increased vagal activity. The mechanisms by which exercise training improves cardiac autonomic modulation and HRV is not fully understood. Nevertheless, studies have shown that HIIT could lead to decrease in catecholamine levels, beta-adrenergic receptor density, and angiotensin II. On the contrary, it may increase nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability and potential mediators which improve cardiac autonomic modulation induced by exercise training.34,35

A reduction of angiotensin II levels after exercise training is an important mechanism that contributes to increasing parasympathetic activity. Angiotensin II is a peptide that increases sympathetic outflow, and inhibits cardiac vagal activity.36 The results of one study demonstrated that angiotensin II levels declined significantly in animal models undergoing HIIT.37 Additionally, another study has shown that, after HIIT, renin-angiotensin system (RAS) activity in mice is lowered by reduced expression of angiotensin-convertor-enzyme activity, angiotensin receptors, and renin.38 Nevertheless, another study has recently shown that aerobic exercise training improves cardiac autonomic modulation in patients with hypertension, irrespective of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor treatment.39 Thus, it seems that exercise training contributes to cardiac autonomic modulation via other potential mechanisms such as NO bioavailability. NO may have indirect effect on inhibiting sympathetic influences, and play a role in increasing cardiac vagal tone.40 NO bioavailability by induced exercise training, particularly HIIT, improves endothelial function in patients with CAD.21,41 Moreover, animal and human studies have revealed that the increase of NO expression is associated with increases in vagal activity.40,41 The effect of HIIT on NO bioavailability in patients with CAD may be due to the increase of apelin, expression, and phosphorylation of endothelial NO synthase, and the decrease of NO degradation.42 However, Wisloff et al. have shown that HIIT causes fluctuation between high and low intensities, extracts a higher shear stress in patients, and triggers larger responses at the cellular and molecular level. Additionally, HIIT reduces the amount of reactive oxygen species, and increases the activity of superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase.21 However, we showed that HIIT enhanced HRV by increasing HF, SDRR, and RMSSD, as well as reducing LF and LF/HF ratio. The mechanism underlying these effects are not clear. Nonetheless, it was demonstrated that improvement of HRV in LV-HIIT subjects may maintain the subjects in greater time of exercise at a high percentage of VO2peak.

Finally, several limitations of this study need to be emphasized. First, we worked on a relatively small sample size that only included men patients. Second, O2 consumption of patients was not measured. The effect of HIIT on autonomic nervous system outcomes for sympathetic nerve activity could be characterized by using direct nerve recording. However, there are surrogate markers for neurohumoral modulation, such as renin-angiotensin system activity and NO bioavailability, which were not measured in this study. We used an ambulatory 24-hour Holter for HRV recording. This does not allow to control common factors (e.g. posture, breathing frequency, and tidal volume) known to affect HRV.

Conclusion

We investigated the effect of 6 weeks of LV-HIIT and MICT on HRV and some other echocardiographic and hemodynamic indices in post-CABG men. Our results suggest that mean R-R intervals, SDRR, RMSSD, and HF power in LV-HIIT has a greater increase than MICT. Additionally, LF and LF/HF ratio decreases more in LV-HIIT than MICT.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the Heart Center of Baqiyatallah hospital and all the participants of this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Authors have no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roth GA, Huffman MD, Moran AE, Feigin V, Mensah GA, Naghavi M, et al. Global and regional patterns in cardiovascular mortality from 1990 to 2013. Circulation. 2015;132(17):1667–78. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.008720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Airaksinen KE, Ikaheimo MJ, Linnaluoto MK, Niemela M, Takkunen JT. Impaired vagal heart rate control in coronary artery disease. Br Heart J. 1987;58(6):592–7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.58.6.592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Floras JS. Sympathetic nervous system activation in human heart failure: Clinical implications of an updated model. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(5):375–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heart rate variability. Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Eur Heart J. 1996;17(3):354–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malpas SC. Sympathetic nervous system overactivity and its role in the development of cardiovascular disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(2):513–57. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakusic N, Mahovic D, Sonicki Z, Slivnjak V, Baborski F. Outcome of patients with normal and decreased heart rate variability after coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Int J Cardiol. 2013;166(2):516–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pantoni CB, Mendes RG, Di Thommazo-Luporini L, Simoes RP, Amaral-Neto O, Arena R, et al. Recovery of linear and nonlinear heart rate dynamics after coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2014;34(6):449–56. doi: 10.1111/cpf.12115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corra U, Piepoli MF, Carre F, Heuschmann P, Hoffmann U, Verschuren M, et al. Secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation: Physical activity counselling and exercise training: Key components of the position paper from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(16):1967–74. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heran BS, Chen JM, Ebrahim S, Moxham T, Oldridge N, Rees K, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD001800. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001800.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghardashi Afousi A, Izadi MR, Rakhshan K, Mafi F, Biglari S, Gandomkar BH. Improved brachial artery shear patterns and increased flow-mediated dilatation after low-volume high-intensity interval training in type 2 diabetes. Exp Physiol. 2018;103(9):1264–76. doi: 10.1113/EP087005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iellamo F, Manzi V, Caminiti G, Vitale C, Castagna C, Massaro M, et al. Matched dose interval and continuous exercise training induce similar cardiorespiratory and metabolic adaptations in patients with heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(6):2561–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendes RG, Simoes RP, de Souza Melo CF, Pantoni CB, Di Thommazo L, Luzzi S, et al. Left-ventricular function and autonomic cardiac adaptations after short-term inpatient cardiac rehabilitation: A prospective clinical trial. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43(8):720–7. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandercock GR, Grocott-Mason R, Brodie DA. Changes in short-term measures of heart rate variability after eight weeks of cardiac rehabilitation. Clin Auton Res. 2007;17(1):39–45. doi: 10.1007/s10286-007-0392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murad K, Brubaker PH, Fitzgerald DM, Morgan TM, Goff DC, Soliman EZ, et al. Exercise training improves heart rate variability in older patients with heart failure: A randomized, controlled, single-blinded trial. Congest Heart Fail. 2012;18(4):192–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2011.00282.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown CA, Wolfe LA, Hains S, Ropchan G, Parlow J. Spontaneous baroreflex sensitivity after coronary artery bypass graft surgery as a function of gender and age. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;81(9):894–902. doi: 10.1139/y03-087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kokkinos P, Myers J. Exercise and physical activity: Clinical outcomes and applications. Circulation. 2010;122(16):1637–48. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.948349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiroma EJ, Lee IM. Physical activity and cardiovascular health: Lessons learned from epidemiological studies across age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Circulation. 2010;122(7):743–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.914721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piepoli MF, Corra U, Benzer W, Bjarnason-Wehrens B, Dendale P, Gaita D, et al. Secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation: From knowledge to implementation. A position paper from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17(1):1–17. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283313592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guiraud T, Nigam A, Gremeaux V, Meyer P, Juneau M, Bosquet L. High-intensity interval training in cardiac rehabilitation. Sports Med. 2012;42(7):587–605. doi: 10.2165/11631910-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannan AL, Hing W, Simas V, Climstein M, Coombes JS, Jayasinghe R, et al. High-intensity interval training versus moderate-intensity continuous training within cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Access J Sports Med. 2018;9:1–17. doi: 10.2147/OAJSM.S150596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wisloff U, Stoylen A, Loennechen JP, Bruvold M, Rognmo O, Haram PM, et al. Superior cardiovascular effect of aerobic interval training versus moderate continuous training in heart failure patients: A randomized study. Circulation. 2007;115(24):3086–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guiraud T, Labrunee M, Gaucher-Cazalis K, Despas F, Meyer P, Bosquet L, et al. High-intensity interval exercise improves vagal tone and decreases arrhythmias in chronic heart failure. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(10):1861–7. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182967559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trapp EG, Chisholm DJ, Boutcher SH. Metabolic response of trained and untrained women during high-intensity intermittent cycle exercise. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293(6):R2370–R2375. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00780.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guiraud T, Juneau M, Nigam A, Gayda M, Meyer P, Mekary S, et al. Optimization of high intensity interval exercise in coronary heart disease. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(4):733–40. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1287-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moholdt TT, Amundsen BH, Rustad LA, Wahba A, Lovo KT, Gullikstad LR, et al. Aerobic interval training versus continuous moderate exercise after coronary artery bypass surgery: A randomized study of cardiovascular effects and quality of life. Am Heart J. 2009;158(6):1031–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2006;7(2):79–108. doi: 10.1016/j.euje.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katona PG, McLean M, Dighton DH, Guz A. Sympathetic and parasympathetic cardiac control in athletes and nonathletes at rest. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1982;52(6):1652–7. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.52.6.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heydari M, Boutcher YN, Boutcher SH. High-intensity intermittent exercise and cardiovascular and autonomic function. Clin Auton Res. 2013;23(1):57–65. doi: 10.1007/s10286-012-0179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Routledge FS, Campbell TS, McFetridge-Durdle JA, Bacon SL. Improvements in heart rate variability with exercise therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26(6):303–12. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(10)70395-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duru F, Candinas R, Dziekan G, Goebbels U, Myers J, Dubach P. Effect of exercise training on heart rate variability in patients with new-onset left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2000;140(1):157–61. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.106606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sloan RP, Shapiro PA, DeMeersman RE, Bagiella E, Brondolo EN, McKinley PS, et al. The effect of aerobic training and cardiac autonomic regulation in young adults. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(5):921–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.133165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bilchick KC, Fetics B, Djoukeng R, Fisher SG, Fletcher RD, Singh SN, et al. Prognostic value of heart rate variability in chronic congestive heart failure (Veterans Affairs' Survival Trial of Antiarrhythmic Therapy in Congestive Heart Failure). Am J Cardiol. 2002;90(1):24–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cozza IC, Di Sacco TH, Mazon JH, Salgado MC, Dutra SG, Cesarino EJ, et al. Physical exercise improves cardiac autonomic modulation in hypertensive patients independently of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor treatment. Hypertens Res. 2012;35(1):82–7. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ciolac EG, Bocchi EA, Bortolotto LA, Carvalho VO, Greve JM, Guimaraes GV. Effects of high-intensity aerobic interval training vs. moderate exercise on hemodynamic, metabolic and neuro-humoral abnormalities of young normotensive women at high familial risk for hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2010;33(8):836–43. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Izadi MR, Ghardashi Afousi A, Asvadi Fard M, Babaee Bigi MA. High-intensity interval training lowers blood pressure and improves apelin and NOx plasma levels in older treated hypertensive individuals. J Physiol Biochem. 2018;74(1):47–55. doi: 10.1007/s13105-017-0602-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandes T, Hashimoto NY, Magalhaes FC, Fernandes FB, Casarini DE, Carmona AK, et al. Aerobic exercise training-induced left ventricular hypertrophy involves regulatory MicroRNAs, decreased angiotensin-converting enzyme-angiotensin ii, and synergistic regulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2-angiotensin (1-7). Hypertension. 2011;58(2):182–9. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.168252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holloway TM, Bloemberg D, da Silva ML, Simpson JA, Quadrilatero J, Spriet LL. High intensity interval and endurance training have opposing effects on markers of heart failure and cardiac remodeling in hypertensive rats. PLoS One 2015; 10(3): e0121138.38.de Oliveira SG, Dos Santos Neves V, de Oliveira Fraga SR, Souza-Mello V, Barbosa-da-Silva S. High-intensity interval training has beneficial effects on cardiac remodeling through local renin-angiotensin system modulation in mice fed high-fat or high-fructose diets. PLoS One. 2015;10:3–e0121138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Oliveira SG, Dos Santos Neves V, de Oliveira Fraga SR, Souza-Mello V, Barbosa-da-Silva S. High-intensity interval training has beneficial effects on cardiac remodeling through local renin-angiotensin system modulation in mice fed high-fat or high-fructose diets. Life Sci. 2017;189:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chowdhary S, Townend JN. Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of cardiovascular autonomic control. Clin Sci (Lond) 1999;97(1):5–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Munk PS, Staal EM, Butt N, Isaksen K, Larsen AI. High-intensity interval training may reduce in-stent restenosis following percutaneous coronary intervention with stent implantation A randomized controlled trial evaluating the relationship to endothelial function and inflammation. Am Heart J. 2009;158(5):734–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Massion PB, Dessy C, Desjardins F, Pelat M, Havaux X, Belge C, et al. Cardiomyocyte-restricted overexpression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS3) attenuates beta-adrenergic stimulation and reinforces vagal inhibition of cardiac contraction. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2666–72. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145608.80855.BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hambrecht R, Adams V, Erbs S, Linke A, Krankel N, Shu Y, et al. Regular physical activity improves endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease by increasing phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2003;107(25):3152–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000074229.93804.5C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]