Introduction

Drug overdose mortality has reached unprecedented levels in the United States. Over the past two decades, drug overdose has more than tripled to become the leading cause of injury deaths in the US, outnumbering deaths from motor vehicle accidents and homicides according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) / National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Compressed Mortality File and Cause of Death Files (full information in the list of References). The epidemic shows no signs of leveling off: drug overdose mortality continued to rise through 2017, amounting to over 70,000 deaths in that year and increasing by 16 percent per year between 2014 and 2017 (Hedegaard, Warner, and Miniño 2018).

Traditionally, drug overdose and other injury deaths have been regarded as “background mortality,” the expectation being that mortality from these causes of death should continue to decrease and ultimately decline to negligible levels over time (Bongaarts 2006) with improved public health and safety measures, economic growth, etc. The substantial increases in drug overdose mortality that have occurred in the US are both unanticipated and alarming, and the need for a comprehensive examination of cross-national differences in drug overdose mortality is urgent. There is widespread agreement that there is a shortage of cross-national research on drug policy, drug use, and drug overdose mortality; particularly relative to the scope of the issue (Kilmer, Reuter, and Giommoni 2015; Martins et al. 2015; Zobel and Götz 2011).

In addition, it is well known that American life expectancy lags far behind other high-income countries (Crimmins, Preston, and Cohen 2011; Ho 2013; Woolf and Aron 2013), and that the US’s international life expectancy rankings have deteriorated in recent decades (Ho and Hendi 2018; Ho and Preston 2010; Palloni and Yonker 2016). However, the contribution of the contemporary drug overdose epidemic to life expectancy differentials between the US and other high-income countries has not been established. The main aims of this study are (1) to situate the contemporary American drug overdose epidemic in broader perspective by comparing levels of, and trends in, drug overdose mortality in the US to 17 other high-income Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries,1 including examining whether drug overdose mortality is differentially patterned by age and sex across countries, and (2) to quantify the contribution of drug overdose to the magnitude and widening of life expectancy differences between the US and these comparison countries.

Background

The contemporary American drug overdose epidemic

Since the mid-1990s, drug-related hospital emergency department visits, substance abuse treatment admissions, and drug overdose mortality have increased dramatically in the United States. Increases in drug overdose mortality have been particularly sharp since 2010 and have continued through the present (Hedegaard, Warner, and Miniño 2018). Initially, the epidemic was primarily driven by prescription opioids, particularly the prescription painkiller OxyContin (Paulozzi et al. 2011). Following the release of abuse-deterrent formulations of OxyContin in 2010 (Cicero, Ellis, and Surratt 2012; Evans, Lieber, and Powell 2018) and wider recognition of the prescription opioid epidemic, the burden of drug-related mortality shifted increasingly to heroin and other synthetic opiates like fentanyl (Paulozzi et al. 2011; Hedegaard, Warner, and Miniño 2018; Jones, Einstein, and Compton 2018). The subgroups that experienced the largest increases in drug overdose mortality include non-Hispanic whites and the less educated (Ho 2017).

While the US has experienced prior drug epidemics, its current epidemic is distinctive in three key aspects. First, the magnitude of the contemporary epidemic in terms of the estimated number of users and deaths involved far exceeds that of prior epidemics. Second, the earlier epidemics were driven primarily by illicit substances (heroin in the 1970s and cocaine in the 1980s to early 1990s), while legal drugs (prescription opioids) played the main role in initiating and sustaining the contemporary epidemic until the most recent decade. Third, drug overdose mortality was previously concentrated in major cities like New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and San Francisco, while the contemporary epidemic has encompassed dramatic increases in drug overdose mortality in nontraditional locations, particularly midsize cities, suburbs, and rural areas (Paulozzi and Xi 2008; Rigg, Monnat, and Chavez 2018). This has led to a convergence in drug overdose mortality so that drug overdose death rates do not differ substantially between rural areas and metros at the national level, although a large amount of geographic heterogeneity exists in these patterns (Rigg, Monnat, and Chavez 2018).

The events leading directly up to the contemporary epidemic can be briefly summarized as follows: prior to the 1980s, the prevailing belief in the medical community was that few safe and effective methods to manage pain existed, and that opioid painkillers were too dangerously addictive to be prescribed except to terminally-ill cancer patients. By the 1990s, however, a fundamental change had occurred in the American medical establishment (Chiarello 2018; Meier 2003; Wailoo 2014). A new narrative dominated: millions of Americans were suffering needlessly from untreated pain; freedom from pain should be considered a universal human right (Brennan, Carr, and Cousins 2016; Cousins, Brennan, and Carr 2004; International Association for the Study of Pain 2018; Lohman, Schleifer, and Amon 2010) and pain should be accorded the status of the “fifth vital sign”; safe, non-addictive, and effective painkillers had been developed to treat pain; and doctors had a moral obligation to treat pain using these painkillers. Not only did the assessment, management, and treatment of pain become areas of increased and intense focus for medical practitioners, but also, using prescription opioids to treat many different types of non-cancer pain became common. The new importance given to recognizing and treating pain was reflected in the establishment of pain medicine as a subspecialty and the proliferation of pain management specialists: the first certificates in pain management were issued in 1993, followed by a rapid expansion of pain medicine training programs (Conrad and Muñoz 2010; Rathmell and Brown 2002). These trends occurred alongside important structural changes in the health care system in the era of managed care, during which primary care physicians faced increased financial pressures, patient caseloads, and time constraints. With physicians’ employment and pay increasingly tied to patient evaluations, physicians had strong incentives to prescribe painkillers (Quinones 2015; Van Zee 2009).

Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of OxyContin, played a pivotal role in developing and popularizing the narrative that not only was there a moral obligation to treat pain, but that there now existed a safe and effective means of doing so. It marketed OxyContin—a pain reliever consisting of the opioid oxycodone—aggressively for a wide range of conditions including headaches, back pain, sports injuries, and wisdom tooth extraction (Meier 2003; Van Zee 2009). Purdue spent hundreds of millions of dollars (an estimated $200 million in 2001 alone [Goldenheim 2002]) on encouraging prescribing and promotional activities—including sponsoring pain management conferences and continuing medical education seminars (which many states require physicians to take to maintain their licenses)—during which their representatives touted that the risks of addiction were “less than one percent” (Meier 2003; Van Zee 2009).

In the United States, painkiller prescriptions rose rapidly to unprecedented levels. In 1996, the year following its initial approval in the US, sales and prescriptions of OxyContin amounted to roughly $45 million and 316,786 prescriptions, respectively. In 2002, these figures reached $1.5 billion and seven million prescriptions (GAO 2003), corresponding to a 34-fold increase in sales and a 22-fold increase in prescriptions. Sales of all opioid pain relievers quadrupled between 1999 and 2013 (Paulozzi et al. 2011). These trends reflect excessive prescribing on physicians’ parts as well as patients’ demands. The two intersected in “pill mills,” clinics where doctors prescribed enormous amounts of painkillers without medical justification and where clients could obtain pills onsite for cash. Individuals outside the medical establishment were also involved: they owned and ran pill clinics, notably in Florida (Lawson 2015; Temple 2015), and they acted as “sponsors” who recruited groups of users, took them to pain clinics, and paid for their appointments in return for painkillers, which they then resold on the black market (Macy 2018; Quinones 2015; Rigg, March, and Inciardi 2010). The huge amounts of pills entering the population were also fueled by “doctor shopping”—patients obtaining prescriptions for opioid painkillers simultaneously from multiple (as many as five or more) physicians (Hall et al. 2008; McDonald and Carlson 2013). As awareness of the epidemic grew, measures to limit prescribing were instituted; however, drug overdose mortality continued to rise. The huge amounts of prescribed opioids had created a large population of addicts who switched from opioid painkillers to heroin, a cheaper and more easily accessible alternative (Cicero et al. 2012; Evans et al. 2018; Muhuri, Gfroerer, and Davies 2013; Quinones 2015). Since 2010, drug overdose mortality has continued to increase, largely due to heroin and illegally-synthesized fentanyl (Jones, Einstein, and Compton 2018; Rudd et al. 2016). China has emerged as a main supplier of fentanyl to both the United States and Europe (EMCDDA 2018; U.S. Congress 2018).

Cross-national differences in drug overdose mortality

An important open question concerns whether the contemporary American drug overdose epidemic is an isolated phenomenon: is drug overdose mortality higher in the US than other high-income countries?2 Have other high-income countries experienced similar increases in drug overdose mortality, and are they likely to going forward? Increases in opioid prescribing have been noted in several other high-income countries including Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom (Häkkinen et al. 2012; Hamunen et al. 2008; Hauser, Schug, and Furlan 2017; Hider-Mlynarz, Cavalie, and Maison 2018; Karanges et al. 2016; Rintoul et al. 2011; Roxburgh et al. 2017; Schubert, Ihle, and Sabatowski 2013; Weisberg et al. 2014; Zin, Chen, and Knaggs 2014). However, these increases have occurred much more slowly, have often been observed for different opioids (e.g., morphine or weak opioids instead of strong opioids like oxycodone), and are generally much smaller in magnitude than the increases observed in the United States. Extant studies have documented significant increases in opioid-related mortality only in Australia and Canada (del Pozo et al. 2008; Fischer et al. 2006; Lenton, Dietze, and Jauncey 2016; Marschall et al. 2016; van Amsterdam and van den Brink 2015; Weisberg and Stannard 2013).

To date, no systematic cross-national comparison of the magnitudes of, and trends in, drug overdose mortality has been performed, and many studies have highlighted the paucity of literature on opioid abuse in Europe (e.g., Kotecha and Sites 2013; see Casati, Sedefov, and Pfeiffer-Gerschel 2012 for one exception). This study aims to shed light on which of three potential scenarios is likely to hold: (1) American exceptionalism, where the drug overdose epidemic proves to be a uniquely American scourge and other high-income countries escape largely unscathed, (2) the US as vanguard nation, at the forefront of an epidemic that eventually spreads to other high-income countries, or (3) the US as a cautionary tale, where other high-income countries at risk of developing epidemics potentially avoid or mitigate them by learning from the American experience.

Data and methods

Data

Data from the Human Mortality Database (HMD 2017) and the World Health Organization Mortality Database (WHO) are extracted for the set of 18 countries starting with the year in which each country first adopted ICD-10 coding3 and ending with the most recent year for which data are available (which ranges from 2013–2015) (see Appendix Table A-1). Because the earliest and latest years for which data are available for all 18 countries are 2003 and 2013, many of the over-time comparisons focus on these years. For Canada (Statistics Canada 2017) and the US (NCHS 2018), I draw on additional data from these countries’ vital statistics agencies to supplement the WHO and HMD data.4 These data are used to produce country-, year-, sex-, and age-specific drug overdose death rates between 1994 and 2015.

Drug overdose deaths are defined as deaths for which the underlying cause of death was ICD-10 codes X40–X44, X60–X64, X85, and Y10–Y14 following the standard definition used by the US National Center for Health Statistics (Warner et al. 2011; Hedegaard, Warner, and Miniño 2018). These include deaths from both legal and illegal drugs and from deaths of all intents (i.e., drug-related accidental poisonings, suicides, homicides, and deaths of undetermined intent), and they exclude alcohol-related deaths. They include deaths from all drugs (not limited to opioids) since the objective is to capture the full extent of variation in the burden of drug overdose mortality across countries, which may be driven by different substances across time and across countries.

Methods

Age-specific drug overdose death rates are obtained by combining all-cause life table death rates from the HMD with the corresponding fractions of total deaths due to drug overdose from the WHO5:

| (1) |

Where m is death rate, D is the number of deaths, a is age, s is sex, t is year, and i is country. These are used to calculate age-standardized drug overdose death rates using the U.S. population in 2000 as the age standard (SEER).

To assess the role of drug overdose in the US life expectancy shortfall, cause-deleted life tables that answer the question, “What would life expectancy in each country be in the absence of drug overdose mortality?” are calculated (Preston, Heuveline, and Guillot 2001). Chiang’s assumption is used to specify mortality in this counterfactual scenario; this is the standard and appropriate assumption given that drug overdose mortality predominates at ages at which overall levels of mortality are quite low (Chiang 1968; Preston, Heuveline, and Guillot 2001). Years of life lost due to drug overdose are specified as the difference between observed life expectancy and life expectancy from the cause-deleted life table. The contribution of drug overdose to the life expectancy gap between the US and any other country in a given year is calculated as:

| (2) |

The contribution of drug overdose to the change in the life expectancy gap between the US and another country between two time periods is calculated as:

| (3) |

Where in a given time period, and t1 and t2 refer to time periods 1 and 2, respectively.

Results

Levels of and trends in drug overdose mortality

Figure 1 shows age-standardized death rates (ASDRs) from drug overdose for men (Panel A) and women (Panel B) in the 18 countries from 1994–2015. Corresponding numbers for selected years are presented in Appendix Table A-2. Prior to the early 2000s, the US was not an outlier in terms of drug overdose mortality. However, the US has posted the highest drug overdose death rates among this set of countries in each year for over a decade—since 2002 and 2005 for men and women, respectively. In recent years, the US has pulled far above its peer countries. Based on the most recent two years for which data are available, drug overdose mortality appears to be trending upward for men in most (11 out of 18) countries. In contrast, it appears to be trending downward for women.

FIGURE 1.

Age-standardized drug overdose death rates (p.100,000), men (a) and women (b), 18 high-income countries, 1994–2015

NOTES: The 10 countries with the highest drug overdose death rates in 2013 are highlighted. The remaining 8 countries (Austria, Italy, Germany, Japan, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland) are in Gray.

Figure 2 shows ASDRs from drug overdose for men (Panel A) and women (Panel B) by four country groupings in 2013, the most recent year for which data are available for all 18 countries. The four groups are: Anglophone, Nordic, countries with moderate levels of drug overdose mortality (“Medium”), and countries with very low levels of drug overdose mortality (“Low”). Anglophone and Nordic countries have higher levels of drug overdose mortality, while the Medium and Low groups have lower levels. The ranking of individual countries within each group is fairly similar, but not identical, for men and women. The ASDRs ranged from 0.60 (Japan) to 16.97 (US) per 100,000 for men and from 0.39 (Japan) to 10.51 (US) per 100,000 for women. On average, drug overdose mortality was 3.5 times higher in the US than in its peer countries, although this figure ranged from 1.6 to 28 times higher. What is particularly alarming is that even compared to the countries with the next highest death rates—the Nordic countries and other Anglophone countries—drug overdose mortality in the US is now nearly twice as high as in those countries.

FIGURE 3.

Years of life lost from drug overdose by country groupings, men (a) and women (b), 18 high-income countries, 2003 and 2013

Figure 3 shows the years of life lost (YLL) from drug overdose in each country in 2003 and 2013 for men (Panel A) and women (Panel B). In all of the Anglophone and Nordic countries except for Norway, YLL from drug overdose increased between 2003 and 2013. In 2003, YLL from drug overdose ranged from 0 (Italy) to 0.28 (US) for men, and from 0.02 (Italy) to 0.17 (US) for women. In 2013, these figures were 0.02 (Portugal) to 0.45 (US) for men and 0.02 (Italy) to 0.30 (US) for women. In both years, the US lost the most years of life from drug overdose among this set of countries; however, the difference in YLL between the US and the comparison countries increased dramatically over this decade.

FIGURE 4.

Percent of the US life expectancy gap due to drug overdose, men (a) and women (b), 17 high-income countries and average, 2013

Contribution of drug overdose to the US life expectancy shortfall

Given that the US now has much higher drug overdose mortality than other high-income countries, and that this difference has widened over time, it seems likely that the contemporary American drug overdose epidemic is contributing to the US life expectancy shortfall relative to the comparison countries.

Figure 4 shows the percent contribution of drug overdose to the gaps in life expectancy at birth between the US and each of the 17 other countries in 2013 plotted against these gaps for men (Panel A) and women (Panel B). The corresponding numbers are presented in Appendix Table A-3. In general, the association between these measures is negative—the larger the US life expectancy shortfall, the less of it that tends to be due to drug overdose. The percent contributions are generally larger for men (ranging from 4–48 percent) than women (ranging from 4–23 percent). On average, life expectancy was roughly 2.6 years lower in the US than in other high-income countries in 2013 for both men and women, and drug overdose accounted for 12 percent and 8 percent of these 2.6-year gaps, respectively.

FIGURE 5.

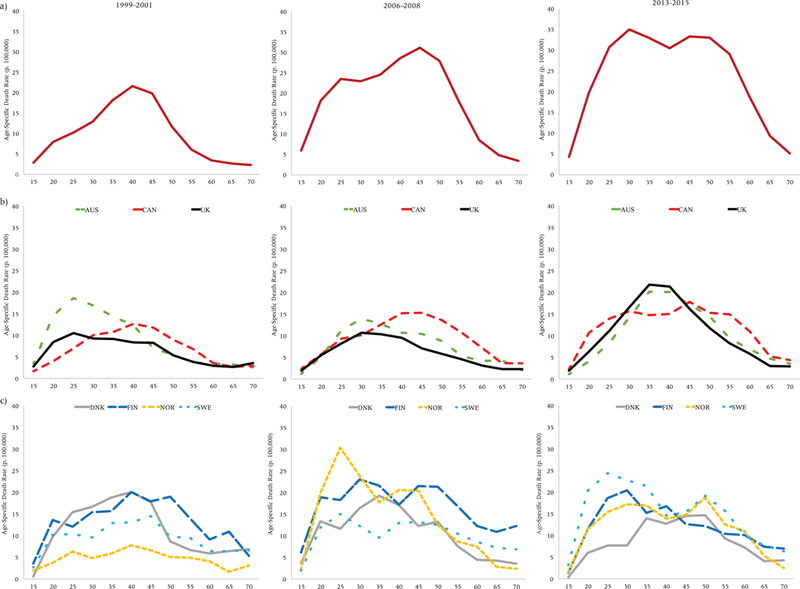

Age-specific drug overdose death rates (p. 100,000), United States (a), Anglophone (b), and Nordic (c) countries, men

How much of the gap is due to drug overdose is a function of several factors including the size of the gap, how high drug overdose mortality is in the comparison country, and at what ages it predominates. For example, drug overdose accounts for more of the US’s shortfall relative to countries like Portugal and Germany partly because both of these countries have very low drug overdose mortality. Drug overdose accounts for little of the US-Sweden life expectancy differential in part because Sweden, like the US, has high drug overdose mortality. However, there remains a considerable degree of variation. For example, Denmark also has fairly high drug overdose mortality, but the contribution of drug overdose to the US-Denmark gap is nontrivial (16 percent and 23 percent for men and women, respectively).

Turning to how drug overdose contributes to changes over time in the US life expectancy shortfall (Table 1), we see that US life expectancy gaps widened by 0.72 and 0.33 years on average for men and women, respectively, between 2003 and 2013. For three countries—Japan for men and women, and Germany and Sweden for women only—these gaps decreased; however, the predominant trend was for the US life expectancy shortfall to widen over this period. In the absence of drug overdose, it would have widened to a lesser degree. On average, the widening would have been one-fifth and one-third smaller for men and women, respectively. Among men, drug overdose made the largest contribution to the widening gap between the US and Germany (40 percent of the 0.43-year increase in the gap) and the smallest contribution to the widening gap between the US and the UK (only 5 percent of the 0.89-year increase). Among women, drug overdose made the largest percent contribution to the widening gap between the US and Australia (61 percent of the 0.14-year increase) and the smallest contribution to the widening gap between the US and Portugal (9 percent of the 1.31-year increase). There were three cases—Belgium, Norway, and Switzerland—where drug overdose accounted for the entirety of the widening. In other words, in the absence of drug overdose, life expectancy differences between American women and women in these three countries would have narrowed instead of increasing.

TABLE 1.

Contribution of drug overdose to the widening of the US life expectancy gap between 2003 and 2013, 17 high-income countries and average

| A. Men |

B. Women |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Δ (2003–2013) | % due to Drug Overdose |

Δ (2003–2013) | % due to Drug Overdose |

| Australia | 0.56 | 20 | 0.14 | 61 |

| Austria | 0.50 | 33 | 0.37 | 39 |

| Belgium | 0.54 | 28 | 0.06 | + |

| Canada | 0.83 | 9 | 0.57 | 15 |

| Denmark | 0.94 | 13 | 0.61 | 16 |

| Finland | 0.70 | 15 | 0.37 | 23 |

| France | 0.91 | 19 | 0.44 | 31 |

| Germany | 0.43 | 40 | −0.15 | * |

| Italy | 0.90 | 16 | 0.42 | 29 |

| Japan | −0.11 | * | −0.27 | * |

| Netherlands | 1.14 | 14 | 0.47 | 21 |

| Norway | 0.58 | 34 | 0.04 | + |

| Portugal | 1.26 | 14 | 1.31 | 9 |

| Spain | 1.43 | 12 | 0.80 | 15 |

| Sweden | 0.16 | 35 | −0.34 | * |

| Switzerland | 0.58 | 22 | 0.12 | + |

| United Kingdom | 0.89 | 5 | 0.64 | 16 |

| Average | 0.72 | 19 | 0.33 | 34 |

Gap narrowed between 2003 and 2013 and would have narrowed further in the absence of drug overdose.

Gap would have narrowed instead of widening between 2003 and 2013 in the absence of drug overdose.

In general, drug overdose’s contribution to the widening of US life expectancy gaps between 2003 and 2013 was larger than its contribution to the magnitudes of these gaps at a point in time (in 2013). The contribution of drug overdose to widening US life expectancy gaps is sizeable. Life expectancy gaps increased between American women and women in 14 of these high-income countries, and drug overdose accounted for 15 percent or more of this widening in 13 of those 14 countries. In the remaining three countries, life expectancy gaps narrowed, and would have narrowed even further in the absence of drug overdose. Among men, life expectancy gaps widened between the US and 16 countries, and the contribution of drug overdose exceeded 15 percent in 10 of these 16 countries.

Age patterns of drug overdose mortality

The next set of figures plots age-specific drug overdose death rates for the US (Panel A), other Anglophone countries (Panel B), and Nordic countries (Panel C) in three periods: 1999–2001, 2006–2008, and 2013–2015.

Starting with men (Figure 5), it is apparent that the age profile of drug overdose mortality has changed tremendously for American men over the past 17 years. In 1999–2001, during the early stages of the epidemic, drug overdose death rates in the United States were highest at ages 35–49. Over time, the age profile rectangularized: death rates are now uniformly high between ages 25–59 in the most recent period. This rectangularization was partly driven by sharp increases in drug overdose mortality at younger ages. Although the age profile of drug overdose mortality became younger over time for American men, it became older for men in the other Anglophone countries. In Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom, the peak ages of drug overdose mortality increased. One of the most striking findings is the similarities between the US and the other Anglophone countries—but with varying time lags. Although overall levels of drug overdose mortality remain lower in Canada than the US, in terms of its age profile, Canada appears to be following a similar trajectory to the US but lagging behind by about seven years (i.e., its 2013–2015 profile strongly resembles the US’s 2006–2008 profile, and Canada’s profile also appears to be rectangularizing due to increases at younger ages). Australia and the UK’s profiles in the most recent period strongly resemble the US’s in the earliest period. Trends in age profiles of mortality are less clear for the Nordic countries. In general, these countries had flatter age profiles in the first two periods; by the most recent period, there appears to have been a shift toward younger ages in Sweden, Finland, and Norway.

FIGURE 6.

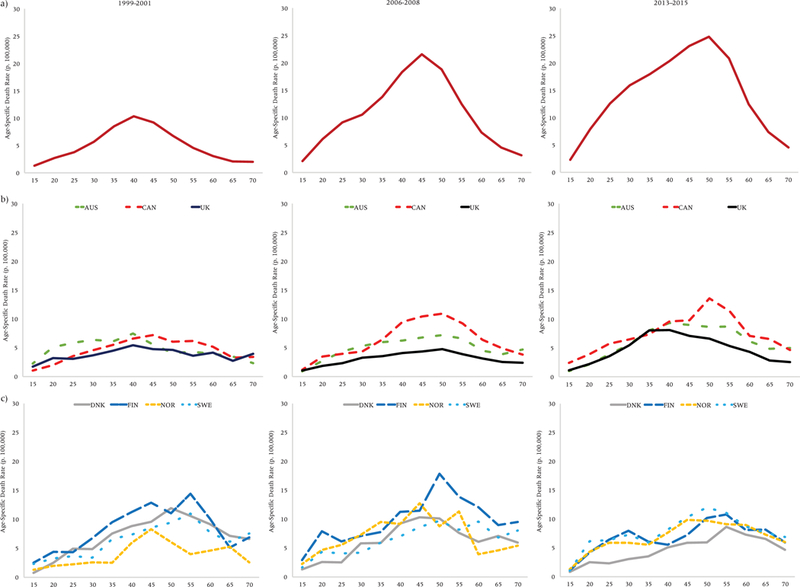

Age-specific drug overdose death rates (p. 100,000), United States (a), Anglophone (b), and Nordic (c) countries, women

Overall, age profiles of drug overdose mortality are older for women (Figure 6) than men. For American women, the profile has shifted to progressively older ages over time. While substantial increases in drug overdose mortality have also occurred at younger ages, the profile for American women remains unimodal and did not rectangularize as it did for American men. In general, trends were similar in the US and other Anglophone countries: the age profile appears to be getting older in all of these countries, although levels of drug overdose mortality remain much lower in the other countries than in the United States. Canada bears the closest resemblance to the US in terms of the shape of its age profile and trends, again offset by several years. The Nordic countries started out having the oldest age profile compared to the other countries in 1999–2001 and did not undergo much change. Women in the other countries converged to their age profiles.

Limitations

Consistent data on drug overdose mortality are available for most high-income countries starting in the late 1990s. Ideally, we would want to examine trends starting in the early 1990s to concretely establish how drug overdose mortality in the US compared prior to the contemporary epidemic. However, data limitations prevent us from precisely identifying drug overdose deaths in years before countries started using ICD-10 coding. The next best strategy is to examine trends in drug-related accidental poisoning deaths (ICD-9 codes E850–E858 and ICD-10 codes X40–X44), a subset of drug overdose deaths that can be consistently defined across ICD changes. Trends in ASDRs from drug-related accidental poisoning (Appendix Figure A-1) are highly consistent with the trends in total drug overdose: the US had fairly high death rates from drug-related accidental poisoning in the 1990s, with death rates increasing in the mid- to late-1990s and pulling away sharply from the other countries since the 2000s.

Data comparability is an important consideration in any cross-national comparative work. Here, the primary concern is whether significant differences in the coding of drug overdose deaths exist across high-income countries. If drug overdose deaths are undercounted in the US relative to other countries, differences between the US and other high-income countries would be even more dramatic than those found in this study and estimates of the contribution of drug overdose to US life expectancy gaps at a point in time and to the widening of these gaps would be underestimates. If drug overdose deaths are undercounted in other countries relative to the US, the opposite would hold. It is nearly impossible to establish which is the case. However, two independent pieces of evidence suggest that the US really does have much higher levels of drug overdose than other high-income countries. First, the US consumes nearly all of the world’s opium supply, accounting for 83 percent and 99 percent of global consumption of oxycodone and hydrocodone, respectively, in 2007 (INCB 2009). Second, we can gain some insights by triangulating mortality data. The question is: if drug overdoses are not coded as such, which cause of death categories are they most likely to be allocated to? Suicides are a likely candidate. In terms of overall suicide mortality, the US has middling (men) to low (women) rates (Appendix Figure A-2). The proportion of total suicides which are drug overdoses ranged from 2 percent (Japan) to 23 percent (Finland) in 2013; this figure was 13 percent for the US. Even if half of all suicides in other countries were due to drug overdose and this figure remained at 13 percent in the US, the US would still have the second highest death rate from drug-related suicide and accidental poisonings combined for men, and the highest death rate for this combined category for women in 2013. Thus, we can be fairly confident that drug-related mortality is indeed considerably higher in the US than in other high-income countries.

Discussion

The United States is experiencing a drug overdose epidemic of unprecedented magnitude, not only judging by its own history but also compared to the experiences of other high-income countries. For over a decade now, the US has had the highest drug overdose mortality among its peer countries. This is a fairly recent phenomenon—in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Nordic countries had the highest levels of drug overdose mortality. However, drug overdose mortality has increased rapidly in the US over the course of the contemporary epidemic, resulting in its dramatic pulling away from other high-income countries.

Among the comparison countries, the Nordic and Anglophone countries have higher drug overdose mortality, while other continental European countries (especially the southern European countries) and Japan have lower mortality. The five countries with the highest levels were Canada, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and the US, while the five countries with the lowest levels were Austria, Italy, Japan, Portugal, and Spain. In terms of its trends in and age profile of drug overdose mortality, Canada is the country that most closely resembles the US, and prescription opioids have played a key role in driving drug overdose mortality in both countries (Fischer et al. 2006; Fischer, Jones, and Rehm 2013; King et al. 2014). The Nordic countries also have high drug overdose mortality but different trends and age profiles than the US, likely due to the differing nature of the substances primarily responsible: prescription drugs (until the most recent decade) in the US versus illicit drugs in the Nordic countries.

The contemporary American drug overdose epidemic has important consequences for international comparisons of life expectancy. While the US is not alone in experiencing increases in drug overdose mortality, the magnitude of the differences in levels of drug overdose mortality is staggering. Drug overdose mortality is now 3.5 times higher on average in the US than other high-income countries. It is over 27 times higher than in Italy and Japan, which have the lowest drug overdose death rates, and 60 percent higher than in Finland and Sweden, the comparator countries with the next highest death rates. Between 2003 and 2013, drug overdose mortality increased by 0.73 (men) and 0.26 (women) deaths per 100,000 on average in the comparison countries compared to increases of 5.53 (men) and 4.15 (women) deaths per 100,000 in the US (Appendix Table A-2).

These differences underlie drug overdose’s growing impact on the US life expectancy shortfall relative to its peer countries. In 2013, drug overdose accounted for 12 percent and 8 percent of the average US life expectancy gap for men and women, respectively, although it accounted for up to 48 percent (Portugal, men) and 23 percent (Denmark, women) of the difference between the US and individual countries. Drug overdose made large contributions to the widening of life expectancy gaps between the US and the comparison countries—in the absence of drug overdose, increases in these gaps would have been on average 19 percent and 34 percent smaller for men and women, respectively. While drug overdose alone does not account for the poor and deteriorating US performance relative to other high-income countries,6 it is an important contributor to recent increases in the US life expectancy shortfall.

Factors contributing to high US drug overdose mortality

It is clear from the results of this study that the contemporary US drug overdose epidemic has catapulted it to having the highest drug overdose death rates among the set of high-income comparison countries. The following section briefly outlines potential factors structuring cross-national differences in drug overdose mortality, with an emphasis on factors influencing the demand for and availability of prescription opioids, the substances primarily responsible for the initial development of the contemporary American epidemic.7

Health care system factors8

The key dimensions of health care provision and financing influencing the use of and mortality related to prescription opioids include: (1) what role opioids play in pain management, including how their prescription is regulated and/or monitored; (2) how opioids are covered, prioritized, and reimbursed by insurance systems; (3) whether and how strongly physician reimbursement is tied to patient satisfaction; (4) how susceptible physicians’ prescribing behaviors are to influence by pharmaceutical advertising and marketing; (5) broader patterns of health care utilization; and (6) the extent of decentralization in the health care system.

Multiple dimensions of the US health care system have contributed to its opioid epidemic. First, strong opioids like oxycodone and methadone became a cornerstone of non-cancer pain treatment in the late 1990s and early 2000s in the United States and have been implicated in a large proportion of drug overdose deaths. Other countries typically did not use strong opioids for pain relief or tended to place greater restrictions on their use. For example, France has relatively high consumption of painkillers, but it consumes primarily non-opioids and has very low use of strong opioids (Hider-Mlynarz, Cavalie, and Maison 2018). Prior to 2008, Norway did not reimburse opioids for non-cancer pain (Hamunen et al. 2008). In Japan, opioids are rarely prescribed for several reasons: physicians must undergo lengthy training to prescribe opioids for non-cancer pain, most pharmacies do not stock opioids due to strict storage requirements, and oxycodone is not covered by insurance for non-cancer pain (Onishi et al. 2017). In most European countries, morphine, not oxycodone, remains the strong opioid of choice for pain treatment (Karanges et al. 2016; Weisberg et al. 2014; Zin, Chen, and Knaggs 2014), and methadone is used primarily for addiction treatment, not pain management (Weisberg and Stannard 2013; Weisberg et al. 2014). Australia, which did experience a switch from weak to strong opioids, reflected in its 14-fold increase in oxycodone consumption between 1997 and 2008, and Ontario, Canada, which saw a 850 percent increase in oxycodone prescriptions between 1991 and 2007, both experienced large increases in drug overdose mortality (Häuser, Schug, and Furlan 2017; Rintoul et al. 2011).

Prior to the present epidemic, relatively few regulations existed in the US regarding the use of strong opioids; in contrast, regulations regarding opioid use in European countries included: dose limits; requirements that patients be registered to receive opioid prescriptions (France, Italy, and Portugal); use of duplicate or triplicate prescription pads (Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland); and use of special prescription forms (Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland) (Cherny et al. 2010; del Pozo et al. 2008; Hamunen et al. 2008). In contrast, reimbursement policies in the US promote greater reliance on opioid prescribing. Insurers in the US are more likely to cover prescription drugs for chronic pain than alternative therapies like physical therapy, steroid injections, and acupuncture, which may be classified as “experimental” or “investigational,” and coverage of non-opioid treatments became more restrictive over time (Cole and de Leon-Casasola 2016; Jacobs 2016). Which types of drugs are covered for chronic pain also matters: in the US, many insurers cover opioids without prior approval while limiting access to less risky and less addictive painkillers by requiring prior approval, placing them in higher cost tiers, covering them only if the pain does not respond to cheaper (but often riskier and more addictive) opioids, or not covering them at all (Thomas and Ornstein 2017). As a result, prescription opioids are the lowest-cost option for many patients in the US. In other countries, there is less recognition of pain as a condition requiring drug therapy (or treatment in general), greater coverage and use of alternative therapies, more conservative attitudes toward use of strong prescription opioids, and cost differences incentivizing the use of safer over riskier opioids (e.g., in all of the Nordic countries, oxycodone is two to three times more expensive than morphine [Hamunen et al. 2008].)

The frequency of use of other types of drugs and procedures can also affect levels of drug overdose mortality. For example, compared to other high-income countries the US appears to be an outlier in terms of the use of psychotropic drugs including benzodiazepines (e.g., the anti-anxiety drugs Xanax and Valium), which act synergistically with prescription opioids to increase mortality (Bachhuber et al. 2016; Dasgupta et al. 2016; Fischer et al. 2013; Park et al. 2015; Sun et al. 2017). While benzodiazepine use has increased markedly in the US, it has declined in countries like the United Kingdom (Weisberg and Stannard 2013). The US also tends to perform more elective procedures including knee replacements, cosmetic surgery, and wisdom teeth extraction (Squires 2012); has shorter waiting times for elective surgeries (Schoen et al. 2007; Siciliani and Hurst 2003); and is more likely to prescribe opioid painkillers to patients undergoing these procedures than other countries. These factors tend to generate higher use of painkillers. Taking the example of prophylactic wisdom teeth extraction, this procedure is commonly performed in Australia, Canada and the US, which have all experienced larger increases in drug overdose mortality, but it is not recommended by most European assessments (Anjrini, Kruger, and Tennant 2015; Boughner 2013).

Use of prescription opioids in the US is also fueled by institutional structures such as provider reimbursement systems and tying physician reimbursement to patient satisfaction. The three main physician payment systems are: salary (paid a fixed amount regardless of patients seen), capitation (paid a fixed amount per patient regardless of services rendered), and fee-for-service (FFS) (paid for each test and service provided). Physicians paid via FFS have greater incentives to provide more care regardless of medical necessity, and FFS is associated with greater or overuse of services and greater barriers to coordination of care (Davis 2007; Gosden et al. 2000). FFS is the dominant payment method in the US, accounting for 95 percent of all physician office visits in 2013 (Berenson and Rich 2010; Zuvekas and Cohen 2016). While 13 of the 17 comparison countries also use FFS (Table 2), they place greater emphasis on capitation and salary, with salary accounting for up to 60–70 percent of physicians’ income in Austria and Finland (Paris, Devaux, and Wei 2010). An interesting pattern that emerges from Table 2 is that all of the Anglophone countries, which have higher levels of drug overdose mortality, use FFS, whereas the set of countries with the lowest drug overdose mortality (Austria, Italy, Japan, Spain, and Portugal) have a much greater reliance on capitation or salary systems. In the US, physicians have stated that their patient satisfaction scores —as well as their paychecks—are negatively affected when they refuse patient demands for prescription painkillers (Hoffman and Tavernise 2016). In countries where physicians are mainly reimbursed through salary or capitation or where FFS is used, but other pay-for-performance metrics—such as lower blood pressure, lower cholesterol, or successfully quitting smoking—matter more for reimbursement than patient satisfaction (e.g., the United Kingdom), fewer incentives to overprescribe exist.

TABLE 2.

Predominant mode of physician reimbursement, 18 high-income countries

| Predominant mode of physician reimbursement |

||

|---|---|---|

| Country | Primary care physicians |

Outpatient specialists |

| Australia | FFS | FFS |

| Austria | FFS/Capitation | FFS |

| Belgium | FFS | FFS |

| Canada | FFS | FFS |

| Denmark | FFS/Capitation | Salary |

| Finland | Salary | Salary |

| France | FFS | FFS |

| Germany | FFS | FFS |

| Italy | Cap | Salary |

| Japan | FFS | FFS |

| Netherlands | Capitation | FFS |

| Norway | FFS/ Capitation | FFS/Salary |

| Portugal | Salary | Salary |

| Spain | Salary/ Capitation | Salary |

| Sweden | Salary | Salary |

| Switzerland | FFS | FFS |

| United Kingdom | Salary/ Capitation /FFS | Salary |

| United States | FFS/ Capitation /Salary | FFS |

NOTES: FFS=fee-for-service

SOURCE: OECD 2011.

Due to the fragmented nature of the US health care system, physicians have greater incentives to prescribe painkillers, and it is more difficult for physicians to identify doctor shopping due to the poor quality, lack, or underutilization of centralized administrative patient records. In other high-income countries, physicians can more easily determine from patients’ medical records whether patients have seen other physicians and whether they recently received or filled prescriptions for painkillers (Weisberg and Stannard 2013). In the United Kingdom, prescribers’ information systems alert them if patients’ doses of opioids escalate, and anomalous prescribing data generally leads to discussions with prescribers and clinical review of patients (ibid.). This type of monitoring remains quite limited and underused in the US, and prescription drug monitoring programs remain underused and vary in terms of quality and completeness across states. There are more deterrents to doctor shopping in other countries with greater coordination of care: doctors are assigned on a regional basis and there are longer wait times (Leonard 2016). The more porous health care system, weak regulatory infrastructure, and participation of multiple stakeholders generates more opportunities for non-physicians to capture profit related to prescription drug diversion in the US than other countries. For example, many of the pill mills and OxyContin smuggling rings supplying much of the East Coast were operated by non-physicians (Lawson 2015; Temple 2015). Similar profit-capturing motives, which exist in the public Canadian system, have been hypothesized to contribute to its opioid epidemic (Fischer et al. 2013).

Pharmaceutical industry factors

Opioid prescribing can also be motivated by pharmaceutical advertising and marketing (EMCDDA 2017a; Hamunen et al. 2008; van Zee 2009). Only three countries in the world—Brazil, New Zealand, and the US—permit direct-to-consumer advertising; all other countries have banned this practice (Ventola 2011). Among OECD countries, the US is an early adopter of drugs—it has faster uptake of new and more expensive prescription drugs. The US constitutes a prime target for pharmaceutical companies due to its population size (as the most populous high-income country) and high drug prices related to organizational, legal, and longstanding cultural reasons (Danzon and Furukawa 2003). These include the fact that the US has a multi-payer system, which has less bargaining power in negotiating drug prices than single-payer systems, and that Medicare, the largest single US payer for prescription drugs, is not permitted by law to negotiate drug pricing (Kanavos et al. 2013; Morgan, Leopold, and Wagner 2017). In contrast, other high-income countries use centralized authorities to negotiate drug prices for the country as a whole, set price controls for drugs, and take an evidence-based approach to drug approval and reimbursement that tends to result in lower prices (Cohen, Malins, and Shahpurwala 2013).

The majority of new drugs are approved in the US before other countries (Downing et al. 2012), and the US was the first country to approve OxyContin (nearly four years earlier on average than the other countries, Table 3). Japan was the last country to approve OxyContin, over seven years later. All five countries with the lowest drug overdose mortality approved OxyContin fairly late and have relatively low approved maximum dosage forms (Table 3). Initially, no one knew how addictive and deadly OxyContin would be, and it took several years for widespread recognition of the drug overdose epidemic to develop. Countries with longer approval processes or which receive applications later can learn from countries which approved the drug earlier. For example, other countries may avoid the epidemic altogether by not approving OxyContin, approving only abuse-deterrent formulations or low dosage forms, or imposing strict regulation and close monitoring of its use.

TABLE 3.

Date of first approval for OxyContin and maximum approved dosage form by country, 18 high-income countries

| Country | Date of first approval |

Maximum approved dosage form (mg) |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 1995/Dec | 160 | 1 |

| Finland | 1996/Jan | 120 | 2 |

| Denmark | 1996/Sep | 160 | 3 |

| Canada | 1996/Dec | 80 | 4 |

| Germany | 1998/May | 120 | 5 |

| Sweden | 1998/Dec | 160 | 6 |

| Switzerland | 1999/Jun | 80 | 7 |

| Australia | 1999/Sep | 80 | 8 |

| Austria | 1999/Nov | 80 | 9 |

| Netherlands | 2000/Apr | 160 | 10 |

| Italy | 2000/May | 80 | 11 |

| France | 2000/Jul | 160 | 12 |

| Norway | 2000/Oct | 120 | 13 |

| Spain | 2000/Nov | 80 | 14 |

| United Kingdom | 2002/May | 120 | 15 |

| Portugal | 2003/May | 80 | 16 |

| Belgium | 2003/Jun | 160 | 17 |

| Japan | 2003/Jul | 40 | 18 |

Drug policy factors

The US favors abstinence-only policies, which have been hypothesized to contribute to riskier drug use, less access to treatment, and higher drug overdose mortality. In contrast, most European countries pursue a harm reduction approach while Canada falls somewhere between the two. Within Europe, policies have generally converged over time with increasing numbers of countries providing opioid substitution treatment—which had widespread adoption in Europe in the 1990s—and needle and syringe exchange programs (Courtwright and Hickman 2011; Zobel and Götz 2011). The United Kingdom, which has also seen recent increases in drug overdose mortality, followed the harm reduction approach (including use of opiate substitution therapies) between 1997 and 2010. From 2010 onwards, however, it has placed a greater emphasis on abstinence, and drug and alcohol treatment have become more decentralized and less integrated with other health services as responsibility was transferred to local authorities under the Health and Social Care Act of 2012 (Middleton, McGrail, and Stringer 2016). There were an estimated number of 204 needle exchange programs in the US in 2013 (increasing to 333 in mid-2018), making it a laggard in this area compared to countries like Australia, which has over 3,000 such programs and is roughly one-thirteenth the population size of the US (Katz 2018). Supervised injection centers or drug consumption facilities exist in Australia, Canada, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, and Switzerland, with those in Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Germany dating prior to the mid-1990s (Dolan et al. 2000; EMCDDA 2010). In the US, these centers do not yet exist and face considerable resistance, although at least two major cities are considering proposals for such centers. These centers create spaces where drug consumption is more easily monitored by medical professionals. The Netherlands, with its commercial “coffee shop” model of selling cannabis, is perhaps the quintessential example of the harm reduction approach (Oesterle et al. 2012; Kilmer, Reuter, and Giommoni 2015). The motivation for these arrangements is that having widely available “soft” drugs as safer legal alternatives will result in fewer incentives to seek out more dangerous “hard” drugs (e.g., heroin, cocaine, etc.) and lower mortality.

A scarcity of substance abuse treatment has been noted in the US, where it is estimated that only 10 percent of those with a substance abuse disorder receive specialist treatment (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality 2016). Compared to other countries, the US has a much lower percentage of opioid-dependent patients in treatment, with some estimates placing the treatment rate at 30 percent in the US compared to over 40 percent in most Western European countries and reaching 63 percent in the UK and 75 percent in the Netherlands (van Amsterdam and van den Brink 2015). Expanding opioid addiction treatment using buprenorphine (a medication which diminishes the effects of physical dependency on opioids), which remains expensive and difficult to access in the US (Bebinger 2016), has proved successful in other countries. For example, a 1995 policy change in France allowing all registered medical doctors to prescribe buprenorphine without any special education or licensing was associated with a tenfold increase in patients being treated and a 79 percent reduction in opiate deaths (Auriacombe et al. 2004).

Some studies (e.g., Weisberg et al. 2014) have hypothesized that greater availability of both cheap heroin and opioid substitution treatment have suppressed demand for prescription opioids in other countries. Notably, Italy, Portugal, and Spain—three of the countries with the lowest drug overdose mortality—have decriminalized illicit drug use. In addition to the cost and availability of alternative substances, polydrug use—using two or more drugs in combination— also influences mortality. Polydrug use has been associated with elevated mortality across several contexts. In this respect, the US does not appear to be an outlier since high levels of polydrug use have also been observed in many of the other high-income countries including all four Nordic countries, Australia, and Austria (EMCDDA 2017a, 2017b; Simonsen et al. 2011; Steentoft et al. 2006; Martyres, Clode, and Burns 2004; Waal and Gossop 2014).

Cultural orientations toward health, pain, and health care utilization

One factor believed to contribute to the drug overdose epidemic is that Americans want “quick fixes” or “magic bullets,” so they are more likely to expect and demand immediate pain relief and prescription painkillers from their physicians than people in other high-income countries (Onishi et al. 2017). The prevailing attitudes toward health care, rationing, and drug therapy in the US create a climate where Americans are quick to adopt and demand new drugs and treatments and are less willing to accept denial of treatment due to cost constraints. These orientations are reflected in the present configuration of the US health care system and may interact with the health care system at multiple junctures. For example, in an environment where patients have wide choice and can easily change providers, physicians have stronger incentives to placate patients by prescribing painkillers, particularly when they have heavy caseloads and their salaries are tied to patient satisfaction.

Other potential contributors

A full exploration of the potential factors shaping cross-national differences in drug overdose mortality lies outside the scope of this paper. Additional factors that have been suggested as potential contributors to these differences include the medicalization of pain; stigma surrounding drug use; occupational health and safety conditions; injuries related to motor vehicles and firearms; population density; levels of sports participation; and poor macroeconomic conditions contributing to unemployment, deindustrialization, and downward intergenerational mobility. It is also likely that the US’s higher prevalence of pain-related chronic diseases and disability may contribute to its elevated levels of drug overdose mortality (Banks et al. 2006; Crimmins et al. 2011; Woolf and Aron 2013). The extent to which these factors shape cross-national differences in drug overdose mortality, as well as their relative importance, remains to be determined, and their further investigation may constitute promising avenues for future research.

Conclusion

Will the contemporary American drug overdose epidemic prove a case of American exceptionalism, a cautionary tale, or the US as vanguard nation? In many respects, the American epidemic is distinctive—it is clear from the results of this analysis that the US is experiencing a drug overdose epidemic of unprecedented magnitude, not only judging by its own historical experience, but also compared to other high-income countries. No other country has exhibited anything close to the levels of or increases in drug overdose mortality observed in the US. However, the potential remains for drug overdose mortality to increase in other countries in the near future. Similar and troubling signs are already discernible in the countries which are closest to the US, namely the Anglophone countries (Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom), and some of the similarities among this subset of countries have been highlighted in the Discussion.

Furthermore, cross-national convergence of the substances driving drug overdose mortality is already occurring. While the current American epidemic started with prescription opioids, it is now rapidly transitioning to heroin and fentanyl (Jones et al. 2018). European countries may be moving in the opposite direction—much of their drug overdose mortality is driven by heroin, but the use of prescription opioids and synthetic drugs like fentanyl are becoming increasingly common in many high-income countries and constitute a common challenge to be confronted by these countries in the near future (EMCDDA 2017a).

Finally, this paper compared the US to other high-income countries partly because of data quality and availability considerations, but also because access to painkillers is very limited outside these countries (Berterame et al. 2016; INCB 2015). However, this situation may change imminently. Mundipharma—a network of international companies owned by the same family as Purdue Pharma—is expanding rapidly into Latin America, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa (Ryan, Girion, and Glover 2016). Its efforts to generate demand for painkillers mirror practices used in the US, including sponsoring physician training seminars and campaigns to medicalize and increase public awareness of chronic pain. Mundipharma’s marketing campaigns involve the use of celebrities urging people to stop thinking of pain as a normal part of daily life: “Don’t resign yourself” and “Chronic pain is an illness in and of itself,” say these advertisements (ibid.). Comparisons are being drawn between opioid painkillers and cigarettes; in the latter case, multinational tobacco companies moved aggressively into developing-country markets when they started losing revenue in developed countries, and it proved a highly successful strategy. If OxyContin follows the same route, it will pose a major concern because regulatory structures, health care systems, and surveillance systems are much less developed in low-income countries, rendering them more vulnerable to aggressive marketing by pharmaceutical companies, and there is a strong possibility that serious drug overdose epidemics could develop with very little warning in these countries.

Supplementary Material

FIGURE 2.

Age-standardized drug overdose death rates (p. 100,000) by country groupings, men (a) and women (b), 18 high-income countries, 2013

Acknowledgments:

I am grateful to Jennifer Ailshire, Eileen Crimmins, Dana Goldman, Noreen Goldman, Arun Hendi, and Julie Zissimopoulos for helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper. This research was supported in part by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R00 HD083519, by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers P30 AG043073 and R01 AG060115, and by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (#74439). The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Footnotes

These countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

Inadequate access to painkillers is an issue in many low- and middle-income countries, where data availability and data quality issues preclude further investigation of drug overdose mortality in these countries. See the Conclusion section below for a fuller treatment of this issue.

It is not possible to produce consistently-defined drug overdose mortality rates for years when countries were using ICD-9 standards based on the WHO data. For sensitivity analyses, see Appendix Figures A-1 and A-2, which present age-standardized death rates from drug-related accidental poisoning and suicide using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes.

These data cover 1994–1998 for the United States and 2012–2013 for Canada.

For countries where the most recent year(s) of data available from the WHO postdates that available from the HMD, all-cause death rates are calculated based on the WHO total deaths and population counts for those years.

US life expectancy was already lower than other high-income countries in the early 1990s, prior to the contemporary drug overdose epidemic.

The focus on opioids is justified given their key role in setting off the contemporary American drug overdose epidemic. They have also been documented to trigger the use of other classes of drugs like methamphetamines in Colorado and Ohio (Daley 2018; Rezvani, Martin, and Hajek 2018). Opioids were implicated in roughly two-thirds (66.4 percent) of all drug overdose deaths that occurred in the United States in 2016 (Hedegaard, Warner, and Miniño 2017).

Prescription opioids are controlled substances, and their production and distribution is licensed and supervised in the US and worldwide. Health care systems are the point of initial dispensation for prescription opioids, even if they are later diverted and/or resold on black markets, rendering several aspects of health care systems particularly salient to this discussion.

References

- Anjrini AA, Kruger E, and Tennant M. 2015. “Cost Effectiveness Modelling of a ‘Watchful Monitoring Strategy’ for Impacted Third Molars vs Prophylactic Removal Under GA: An Australian Perspective.” British Dental Journal 219(1): 19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auriacombe Marc, Fatséas Mélina, Dubernet Jacques, Daulouède Jean-Pierre, and Tignol Jean. 2004. “French Field Experience with Buprenorphine.” The American Journal on Addictions 13: S17–S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachhuber Marcus A., Hennessy Sean, Cunningham Chinazo O., and Starrels Joanna L.. 2016. “Increasing Benzodiazepine Prescriptions and Overdose Mortality in the United States, 1996–2013.” American Journal of Public Health 106: 686–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks James, Marmot Michael, Oldfield Zoe, and Smith James P.. 2006. “Disease and Disadvantage in the United States and in England.” Journal of the American Medical Association 295: 2037–2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebinger Martha. 2016. “FDA Considering Pricey Implant as Treatment for Opioid Addiction.” National Public Radio Morning Edition, May 20, 2016. http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/05/20/478577515/fda-considering-pricey-implant-as-treatment-for-opioid-addiction. [Google Scholar]

- Berenson Robert A., and Rich Eugene C.. 2010. “US Approaches to Physician Payment: The Deconstruction of Primary Care.” J Gen Intern Med 25: 613–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berterame Stefano, Erthal Juliana, Thomas Johny, Fellner Sarah, Vosse Benjamin, Clare Philip, Hao Wei, Johnson David T., Mohar Alejandro, Pavadia Jagjit, Samak Ahmed Kamal Eldin, Sipp Werner, Sumyai Viroj, Suryawati Sri, Toufq Jallal, Yans Raymond, and Mattick Richard P.. 2016. “Use of and Barriers to Access to Opioid Analgesics: A Worldwide, Regional, and National Study.” Lancet 16: 1644–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts John. 2006. “How Long Will We Live?” Population and Development Review 32: 605–628. [Google Scholar]

- Boughner Julia C. 2013. “Maintaining Perspective on Third Molar Extraction.” J Can Dent Assoc 79: d106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan Frank, Carr Daniel, and Cousins Michael. 2016. “Access to Pain Management-Still Very Much a Human Right.” Pain Med 17: 1785–1789.Casati, Alicia, Roumen Sedefov, and Tim Pfeiffer-Gerschel. 2012. “Misuse of Medicines in the European Union: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Eur Addict Res 18: 228–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2016. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Compressed Mortality File 1979–1998. CDC WONDER On-line Database, compiled from Compressed Mortality File CMF 1968–1988, Series 20, No. 2A, 2000 and CMF 1989–1998, Series 20, No. 2E, 2003.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Underlying Cause of Death 1999–2016 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released December, 2017. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999–2016, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

- Cherny NI, Baselga J, de Conno F, and Radbruch L. 2010. “Formulary Availability and Regulatory Barriers to Accessibility of Opioids for Cancer Pain in Europe: A Report from the ESMO/EAPC Opioid Policy Initiative.” Annals of Oncology 21: 615–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang Chin Long. 1968. An Introduction to Stochastic Processes in Biostatistics. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Chiarello Elizabeth. 2018. “Where Movements Matter: Examining Unintended Consequences of the Pain Management Movement in Medical, Criminal Justice, and Public Health Fields.” Law & Policy 40: 79–109. [Google Scholar]

- Cicero Theodore J., Ellis Matthew S., and Surratt Hilary L.. 2012. “Effect of Abuse-Deterrent Formulation of OxyContin.” New England Journal of Medicine 367(2): 187–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Joshua, Malins Ashley, and Shahpurawala Zainab. 2013. “Compared to US Practice, Evidence-Based Reviews in Europe Appear to Lead to Lower Prices for Some Drugs.” Health Affairs 32: 762–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole Daniel, and de Leon-Casasola Oscar. 2016. Letter to Thomas Frieden, January 13, 2016. https://www.asra.com/content/documents/2016-1-6-_asa-asra_comments_cdc_guideline_final.pdf.

- Conrad Peter, and Muñoz Vanessa L.. 2010. “The Medicalization of Chronic Pain.” Tidsskrift for Forskning i Sygdom og Samfund 7: 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Courtwright David T., and Hickman Timothy A.. 2011. “Modernity and Anti-Modernity: Drug Policy and Political Culture in the United States and Europe in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries” In Drugs and Culture: Knowledge, Consumption and Policy, edited by Hunt Geoffrey, Milhet Maitena, and Bergeron Henri, 213–224. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins Eileen M., Preston Samuel H., and Cohen Barney., eds. 2011. International Differences in Life Expectancy at Older Ages: Dimensions and Sources Panel on Understanding Divergent Trends in Longevity in High-Income Countries, Committee on Population, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley John. 2018. “A Surge In Meth Use In Colorado Complicates Opioid Recovery.” National Public Radio, July 14, 2018. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/07/14/628134831/a-surge-in-meth-use-in-colorado-complicates-opioid-recovery. [Google Scholar]

- Danzon Patricia M., and Furukawa Michael F.. 2003. “Prices and Availability of Pharmaceuticals: Evidence from Nine Countries.” Health Affairs W3: 521–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta Nabarun, Michele Jonsson Funk Scott Proescholdbell, Hirsch Annie, Ribisl Kurt M., and Marshall Steve. 2016. “Cohort Study of the Impact of High-Dose Opioid Analgesics on Overdose Mortality.” Pain Medicine 17: 85–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis Karen. 2007. “Paying for Care Episodes and Care Coordination.” New England Journal of Medicine 256: 1166–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan Kate, Kimber Jo, Fry Craig, Fitzgerald John, McDonald David, and Trautmann Franz. 2000. “Drug Consumption Facilities in Europe and the Establishment of Supervised Injecting Centres in Australia.” Drug and Alcohol Review 19(3): 337–346. [Google Scholar]

- Downing Nicholas S., Aminawung Jenerius A., Shah Nilay D., Braunstein Joel B., Krumholz Harlan M., and Ross Joseph S.. 2012. “Regulatory Review of Novel Therapeutics – Comparison of Three Regulatory Agencies.” New England Journal of Medicine 366: 2284–2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, William N., Ethan Lieber, and Patrick Power. 2018. “How the Reformulation of OxyContin Ignited the Heroin Epidemic,” NBER Working Paper No. 24475.

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). 2010. Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges Tim Rhodes and Dagmar Hedrich, eds. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). 2017a. European Drug Report 2017: Trends and Developments. Luxemburg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). 2017b. Austria, Country Drug Report 2017. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). 2018. Fentanils and synthetic cannabinoids: driving greater complexity into the drug situation An update from the EU Early Warning System. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer Benedikt, Rehm Jürgen, Patra Jayadeep, and Cruz Michelle Firestone. 2006. “Changes in illicit opioid use across Canada.” CMAJ 175: 1385–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer Benedikt, Jones Wayne, and Rehm Jürgen. 2013. “High Correlations between Levels of Consumption and Mortality Related to Strong Prescription Opioid Analgesics in British Columbia and Ontario, 2005–2009.” Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 22: 438–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- General Accounting Office (GAO). 2003. Prescription Drugs: OxyContin Abuse and Diversion and Efforts to Address the Problem. Publication GAO-04–110. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office. [Google Scholar]

- Goldenheim Paul. 2002. “OxyContin: Balancing Risks and Benefits” Testimony in Hearing of the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, United States: Senate, February 12, 2002, p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Gosden Toby, Forland Frode, Kristiansen Ivar, Sutton Matthew, Leese Brenda, Giuffrida Antonio, Sergison Michelle, and Pedersen Lone. 2000. “Capitation, Salary, Fee-for-service and Mixed Systems of Payment: Effects on the Behaviour of Primary Care Physicians.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3 Art. No.: CD002215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häkkinen Margareeta, Launiainen Terhi, Vuori Erkki, and Ojanperä Ilkka. 2012. “Comparison of Fatal Poisonings by Prescription Opioids.” Forensic Science International 222(1–3): 327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall Aron J., Logan Joseph E., Toblin Robin L., Kaplan James A., Kraner James C., Bixler Danae, Crosby Alex E., and Paulozzi Leonard J.. 2008. “Patterns of Abuse among Unintentional Pharmaceutical Overdose Fatalities.” Journal of the American Medical Association 300: 2613–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamunen Katri, Pirjo Laitinen-Parkkonen Pirkko Paakkari, Breivik Harald, Gordh Torsten, Jensen Niels Henrik, and Kalso Eija. 2008. “What Do Different Databases Tell About the Use of Opioids in Seven European Countries in 2002?” European Journal of Pain 12: 705–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häuser Winfried, Schug Stephan, and Furlan Andrea D.. 2017. “The Opioid Epidemic and National Guidelines for Opioid Therapy for Chronic Noncancer Pain: A Perspective from Different Continents.” PAIN Reports 2(3): e599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard Holly, Warner Margaret, and Miniño Arialdi M.. 2017. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2016. NCHS data brief, no 294. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard Holly, Warner Margaret, and Miniño Arialdi M.. 2018. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS data brief, no 329. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Hider-Mlynarz Karima, Cavalié Philippe, and Maison Patrick. 2018. “Trends in Analgesic Consumption in France over the Last 10 Years and Comparison of Patterns across Europe.” British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 84(6): 1324–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Jessica Y. 2013. “Mortality Under Age 50 Accounts for Much of the Fact that US Life Expectancy Lags that of Other High-income Countries.” Health Affairs 32: 459–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Jessica Y. 2017. “The Contribution of Drug Overdose to Educational Gradients in Life Expectancy in the United States, 1992–2011.” Demography 54: 1175–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Jessica Y., and Hendi Arun S.. 2018. “Recent trends in life expectancy across high income countries.” The BMJ 362: k2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Jessica Y., and Preston Samuel H.. 2010. “US Mortality in an International Context: Age Variations.” Population and Development Review 36: 749–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman Jan, and Tavernise Sabrina. 2016. “Vexing Question on Patient Surveys: Did We Ease Your Pain?” New York Times, August 4, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/05/health/pain-treatment-hospitals-emergency-rooms-surveys.html. [Google Scholar]

- Human Mortality Database (HMD). University of California, Berkeley (USA), and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany). www.mortality.org or www.humanmortality.de (accessed November 26, 2017).

- International Association for the Study of Pain. 2018. Declaration of Montréal. https://www.iasp-pain.org/DeclarationofMontreal (accessed January 2, 2019).

- International Narcotics Control Board (INCB). 2009. The Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2008. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- International Narcotics Control Board (INCB). 2015. The Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2014. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs Harrison. 2016. “Pain Doctors: Insurance Companies Won’t Cover the Alternatives to Opioids.” Business Insider, August 10, 2016. http://www.businessinsider.com/doctors-insurance-companies-policies-opioid-use-2016-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Christopher M., Einstein Emily B., and Compton Wilson M.. 2018. “Changes in Synthetic Opioid Involvement in Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 2010–2016.” JAMA 319(17): 1819–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanavos Panos, Ferrario Alessandra, Vandoros Sotiris, and Anderson Gerard F.. 2013. “Higher US Branded Drug Prices and Spending Compared to Other Countries may Stem Partly from Quick Uptake of New Drugs.” Health Affairs 32: 753–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanges Emily A., Blanch Bianca, Buckley Nicholas A., and Pearson Sallie-Anne. 2016. “Twenty-five Years of Prescription Opioid Use in Australia: A Whole-of-population Analysis Using Pharmaceutical Claims.” British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 82: 255–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz Josh. 2018. “Why a City at the Center of the Opioid Crisis Gave Up a Tool to Fight It.” New York Times, April 27, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/04/27/upshot/charleston-opioid-crisis-needle-exchange.html. [Google Scholar]

- Kilmer Beau, Reuter Peter, and Giommoni Luca. 2015. “What Can Be Learned from Cross-National Comparisons of Data on Illegal Drugs?” Crime and Justice 44(1): 227–296. [Google Scholar]

- King Nicholas B., Fraser Veronique, Boikos Constantina, Richardson Robin, and Harper Sam. 2014. “Determinants of Increased Opioid-related Mortality in the United States and Canada, 1990–2013: A Systematic Review.” American Journal of Public Health 104: e32–e42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotecha MK, and Sites BD. 2013. “Pain Policy and Abuse of Prescription Opioids in the USA: A Cautionary Tale for Europe.” Anaesthesia 68: 1207–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson Guy. 2015. “The Dukes of Oxy: How a Band of Teen Wrestlers Built a Smuggling Empire.” Rolling Stone, April 9, 2015. http://www.rollingstone.com/culture/features/the-dukes-of-oxy-how-a-band-of-teen-wrestlers-built-a-smuggling-empire-20150409. [Google Scholar]

- Lenton Simon R., Dietze Paul M., and Jauncey Marianne. 2016. “Australia Reschedules Naloxone for Opioid Overdose.” MJA 204(4): 146–147e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard Kimberley. 2016. “Is the EU Facing the Next Opioid Epidemic?” US News, August 3, 2016. http://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2016-08-03/european-union-sees-alarming-rates-of-prescription-drug-abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Lohman Diederik, Schleifer Rebecca, and Amon Joseph J. 2010. “Access to pain treatment as a human right.” BMC Med 8:8.Macy, Beth. 2018. Dopesick. New York: Hachette Book Group. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschall U, L’hoest H, Radbruch L, and Häuser W. 2016. “Long-term Opioid Therapy for Chronic Non-cancer Pain in Germany.” Eur J Pain 20(5): 767–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins Silvia S., Sampson Laura, Cerdá Magdalena, and Galea Sandro. 2015. “Worldwide Prevalence and Trends in Unintentional Drug Overdose: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” American Journal of Public Health 105(11): e29–e49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyres Raymond F., Clode Danielle, and Burns Jane M. 2004. “Seeking Drugs or Seeking Help? Escalating “Doctor Shopping” by Young Heroin Users Before Fatal Overdose.” MJA 180: 211–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald Douglas C., and Carlson Kenneth E.. 2013. “Estimating the Prevalence of Opioid Diversion by ‘Doctor Shoppers’ in the United States.” PLoS ONE 8: e69241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier Barry. 2003. Pain Killer: A “Wonder” Drug’s Trail of Addiction and Death. New York: Rodale, St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton John, McGrail Sara, and Stringer Ken. 2016. “Drug Related Deaths in England and Wales.” BMJ 354: i5259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan Steven G., Leopold Christine, and Wagner Anita K.. 2017. “Drivers of Expenditure on Primary Care Prescription Drugs in 10 High-income Countries with Universal Health Coverage.” CMAJ 189: E794–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhuri Pradip K., Gfroerer Joseph C., and Davies M. Christine. 2013. “Associations of Nonmedical Pain Reliever Use and Initiation of Heroin Use in the United States.” CBHSQ Data Review. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Mortality - State Only (2005+) and Mortality - All County (micro-data) files (1989–2015), as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. 2018.

- Oesterle Sabrina, Hawkins J. David, Steketee Majone, Jonkman Harrie, Brown Eric C., Moll Marit, and Haggerty Kevin P.. 2012. “A Cross-National Comparison of Risk and Protective Factors for Adolescent Drug Use and Delinquency in the United States and the Netherlands.” Journal of Drug Issues 42(4): 337–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]