Abstract

Background

The Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) has become one of the most widely used cognitive screening instruments since its initial publication. To date, only a handful of studies have explored longitudinal characteristics of the MoCA.

Aim

The aim of this study is to characterize the trajectory of MoCA performance across a broad age continuum of older adults.

Methods

Data from 467 cognitively normal participants were used in this analysis. The sample was grouped into four strata based on the participants’ age at baseline (60–69, 70–79, 80–89, and 90–99). Mixed model repeated measures (MMRM) analysis and mixed-effects spline models were used to characterize the trajectory of MoCA scores in each age stratum and in the entire sample. Intrasubject standard deviation (ISD) was used to characterize the natural variability of individual MoCA performance over time.

Results

The ISD values for each of the age strata indicated that year-to-year individual variation on the MoCA ranged from zero to three points. MMRM analysis showed that the 60–69 stratum remained relatively stable over time while the 70–79 and 80–89 strata both showed notable decline relative to baseline performance. The mixed-effects spline model showed that MoCA performance declines linearly across the older adult age span.

Discussion

Among cognitively normal older adults MoCA performance remains relatively stable over time, however across the older adult age-span MoCA performance declines in a linear fashion. These results will help clinicians better understand the normal course of MoCA change in older adults while researchers may use these results to inform sample size estimates for intervention studies.

Conclusion

This study provides an enhanced view of the MoCA’s intraindividual trajectory in normal elderly aged 60 and older.

Keywords: Cognition, Cognitive variability, Intraindividual change, Age-associated cognitive decline, Age-associated memory impairment

Introduction

The Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) has become one of the most widely used cognitive screening instruments since its initial publication in 2005 [1]. Several studies have reported on its ability to accurately identify individuals with impaired cognition relative to those who are non-cognitively impaired (NCI) [2–5]. In particular, recent studies have suggested that it is superior to the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) in terms of its diagnostic accuracy for identifying individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [3–5]. Cross-sectional normative performance of the MoCA in NCI older adults has also been reported by our group [6] and others [7].

To date, only a handful of studies have explored longitudinal characteristics of the MoCA. In particular, very few have provided information regarding MoCA trajectory in individuals age 80 and older. Costa and colleagues [8] demonstrated that the MoCA corresponded with clinically meaningful disease progression in a small cohort of memory clinic patients over 1-year (n = 25; MCI = 18, 7 = mild Alzheimer’s disease). Specifically, a medium effect size (d = 0.43) was noted for the degree of 1-year MoCA score change in the MCI group. Krishnan et al. [9] found a larger, but still moderate effect size (d = 0.63) for the degree of change in MCI patients over 3.5 years. Among NCI individuals, the variability in longitudinal MoCA performance is relatively high with only 40% remaining stable (within one point of first MoCA score) after 1 year [10]. In this same study, 30% of individuals had MoCA scores that were two points higher than the first assessment with the remaining individuals showing a decline of at least two points after 1 year [10].

Cooley et al. [11] reported annual increases in MoCA scores over several years among NCI individuals, especially between the first and second assessments. Krishnan et al. [9] found that NCI individuals showed little change in MoCA performance over a 3.5-year follow-up period and that a decline of greater than 1.73 points from baseline is indicative of clinically meaningful change. The neural mechanisms underlying the ability to maintain cognitive performance in older age are unclear; however, neuroimaging evidence indicates that the relative stability of the MoCA in NCI older adults is associated with greater volume in a number of different brain regions [12].

Although these studies have provided good estimates of the natural MoCA trajectory in older adults, octogenarians and nonagenarians do not appear to be well-represented in these samples. The aim of this study is to characterize the trajectory of MoCA performance across a broad age continuum of older adults which includes individuals in their 9th and 10th decades.

Methods

Study sample

Data from 467 cognitively normal participants from the longevity study: learning from our elders [13] were used in this analysis. The primary catchment area for this study is the northwest region of the Phoenix, Arizona metropolitan area, however individuals from regions across Arizona are also enrolled. Interviews are conducted in person with trained volunteers and staff while several questionnaires are filled out by the study participants. Participants are recruited through advertisements, community talks, and referrals from individuals already participating in the study. All participants signed an informed consent form prior to participating. The Longevity Study is approved by the Western and Arizona State University Institutional Review Boards.

For this analysis, participants who had at least two observations with complete MoCA scores ranging between 20 and 30 were used. This range of scores is consistent with normative MoCA performance for older adults [6]. To minimize practice effects, alternating versions of the MoCA were used at each assessment. All individuals were community-dwelling, independent individuals deemed to be cognitively normal based on interview and self-reported medical history of no dementia or other diagnoses that would cause cognitive impairment. In addition, all individuals reported no significant dysfunction in activities of daily living.

Statistical analysis

The sample was grouped into four strata based on the participants’ age at baseline (60–69, 70–79, 80–89, and 90–99). Chi-square was used to determine if significant differences in gender frequency were present among the age strata. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess group differences for baseline MoCA scores, length of follow-up, annualized rate of change, and intrasubject standard deviation (ISD). Tukey test was used to analyze groupwise comparisons.

For each participant, an annualized rate of change for the MoCA was calculated by taking the difference in MoCA scores between the most recent and baseline assessments. This difference was then divided by the duration (years) that elapsed between baseline and the most recent visit.

Mixed model repeated measures (MMRM) analysis was used to characterize the trajectory of MoCA change within each age stratum. MoCA score at each annual visit was used as the outcome while annual visit number, age stratum, gender, education, baseline MoCA score, and annual visit number by age stratum interaction were used as predictors. Variance components covariance structure was used to characterize within-subject variability of MoCA performance between annual assessments.

Least-squares means for the annual visit number by age stratum interaction were derived to estimate MoCA scores at each annual visit within each of the age strata.

Additional analyses to estimate the rate of change for the MoCA over the entire sample were carried out using a mixed-effects spline model. This generated an estimated MoCA score for each age value. However, for brevity we report the estimated MoCA scores in 5-year increments.

Statistical analyses were carried out using SYSTAT 13.1, SAS Enterprise Guide 6.1, and R 3.4.0. Analysis of demographic variables and groupwise comparisons of ISD and annualized MoCA change were carried out in SYS-TAT. MMRM analysis was carried out in SAS using ‘proc mixed’. The ‘sme’ and ‘plot.SmeModel’ functions in the “sme” package in R were used for the mixed-effects spline model and plot.

Results

Demographic and descriptive statistics grouped by age strata are shown in Table 1. For the entire sample the average duration of follow-up was 2.77 ± 1.45 years with range of 1–6.5 years. 49% of the sample had at least 16 years of education and 72% of the sample was comprised of females. Length of follow-up was significantly different between age strata with the 60–69 and 70–79 strata having significantly longer follow-up lengths than the 90–99 age stratum (p = 0.03 and p = 0.01, respectively). Baseline MoCA scores were significantly different between the age strata (p < 0.001) with all pairwise comparisons showing significant differences (p < 0.001) except the comparison of the 80–89 and 90–99 strata (p = 0.07). MoCA scores between males and females were not significantly different (p = 0.30). For education effects, individuals with 16 or more years had significantly greater MoCA scores (26.44 ± 2.46) relative to those with 12–15 years education (25.86 ± 2.52; p = 0.04). The magnitude of this difference was small (d = 0.23). Individuals with less than 12 years of education (25.83 ± 1.17) were not significantly different from the other groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and descriptive statistics

| 60–69 | 70–79 | 80–89 | 90–99 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 75 | 131 | 163 | 98 |

| Gender (M/F) | 16/59 | 27/104 | 56/107 | 30/68 |

| Education (16 years or more %) | 67% | 50% | 45% | 42% |

| Baseline age (years) | 65.64 ± 2.95 | 74.15 ± 2.85 | 84.79 ± 2.80 | 93.70 ± 2.48 |

| Length of follow-up (years) | 2.98 ± 1.55 | 3.01 ± 1.46 | 2.71 ± 1.38 | 2.38 ± 1.43 |

| Baseline MoCA score | 27.79 ± 1.98 | 26.63 ± 2.27 | 25.70 ± 2.47 | 24.98 ± 2.37 |

| Intrasubject standard deviation (MoCA) | 1.51 ± 1.07 | 1.69 ± 0.91 | 1.98 ± 1.09 | 1.88 ± 1.16 |

| Annualized MoCA change | −0.22 ± 1.72 | −0.03 ± 1.37 | −0.37 ± 1.98 | −0.76 ± 1.90 |

Mean ± standard deviation

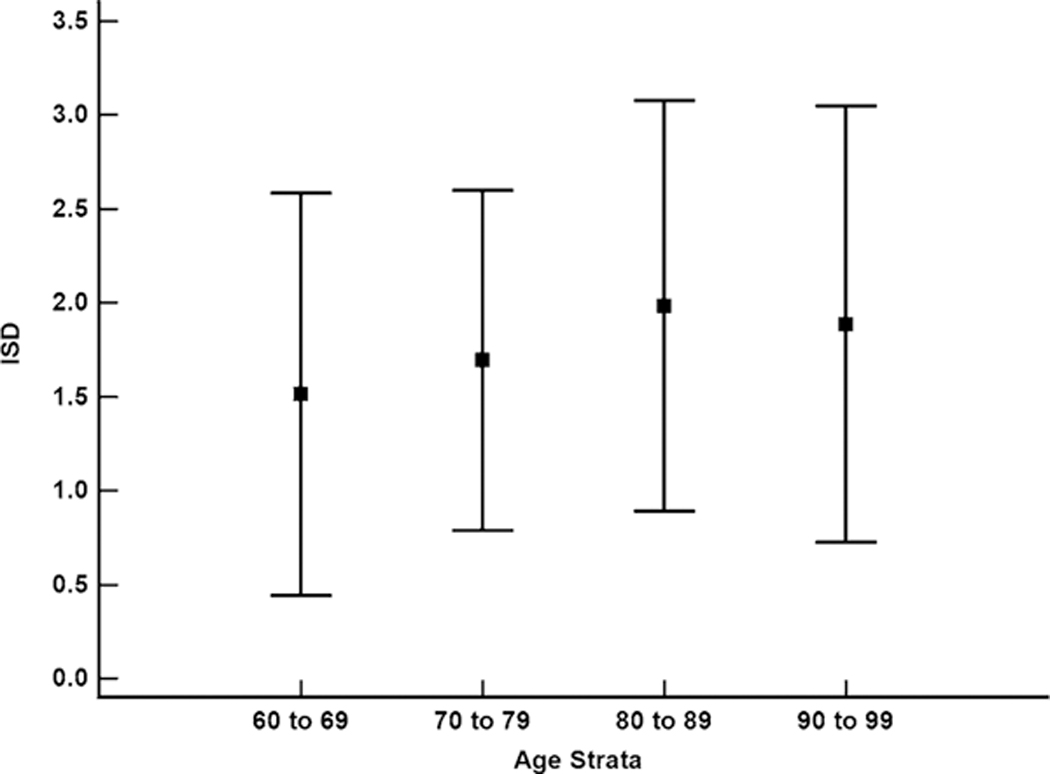

Annualized MoCA change was significantly different between the 70–79 and 90–99 age strata (p = 0.01). A significant groupwise difference for ISD was present only between the 60–69 and 80–89 age strata (p = 0.01) (Fig. 1). The ISD values for each of the age strata indicated that year-to-year individual variation on the MoCA has an approximate range of zero to three points (Fig. 1) with the majority of individuals showing year-to-year variation of one to two points (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Intrasubject standard deviation (ISD) values for the MoCA by age strata. Boxes are means and error bars are standard deviation; Only the 60–69 and 80–89 age strata were significantly different (p = 0.01)

Table 2.

MMRM-estimated annual MoCA scores by age stratum

| Baseline | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60–69 | 27.44 (26.68, 28.21) | 26.90 (26.12, 27.69) | 26.79 (25.97, 27.62) | 27.00 (26.12, 27.87) | 27.12 (26.06, 28.18) | 27.19 (25.78, 28.59) |

| 70–79 | 26.34 (25.66, 27.02) | 26.74 (26.05, 27.43) | 26.19 (25.48, 26.90) | 26.48 (25.72, 27.25) | 26.08 (25.23, 26.93) | 25.02 (23.91, 26.12) |

| 80–89 | 25.50 (24.86, 26.13) | 25.34 (24.69, 25.98) | 24.44 (23.78, 25.10) | 25.03 (24.30, 25.76) | 24.83 (23.98, 25.68) | 23.34 (22.17, 24.52) |

| 90–99 | 24.72 (24.05, 25.40) | 24.49 (23.80, 25.17) | 23.84 (23.09, 24.59) | 23.95 (23.06, 24.85) | 23.04 (21.95, 24.13) | 24.13 (22.62, 25.64) |

MoCA score (95% confidence interval)

Results of the MMRM analysis are shown in Table 2. Across the annual visits, MoCA performance was relatively stable for each age stratum. However, the 70–79 and 80–89 age strata both showed incremental year-to-year decline. The 60–69 stratum was stable across all annual visits while the 80–89 stratum appeared to have the greatest year-to-year MoCA score fluctuation. The 90–99 stratum also showed incremental year-to-year decline, but then showed a one-point improvement between year 4 and year 5.

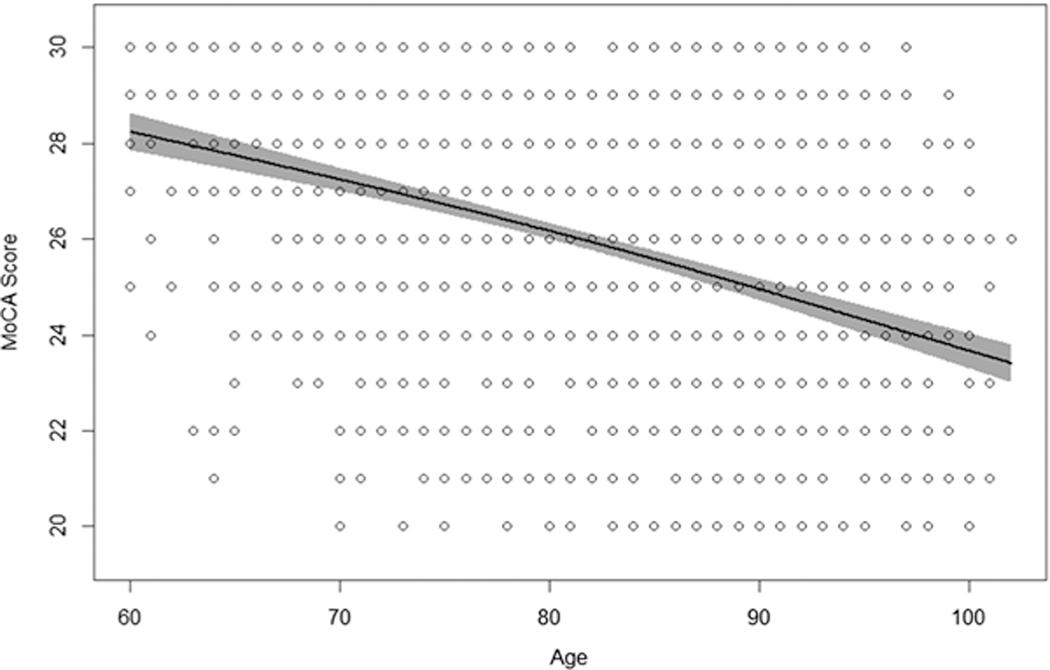

MoCA scores from the mixed-effects spline model in 5-year age increments are shown in Table 3. Across the age span of older adults, MoCA performance declines in a linear fashion (Fig. 2). However, differences in 5-year age increment MoCA scores show that the rate of decline accelerates slightly at approximately age 80 and continues an incremental acceleration at each 5-year increment (Table 3). Since the mixed-effects spline model produced a linear trajectory of age-related MoCA decline, a linear mixed-effects model was used to generate a prediction equation for age-adjusted MoCA scores. The linear mixed-effects model used MoCA scores as the outcome and age at visit as the predictor with the intercept and slope of each subject as a random effect. Using the model’s intercept and slope, an age-corrected MoCA score formula was derived: Age-Corrected MoCA Score = 35.34 + (−0.12 * Age at Assessment)

Table 3.

Mixed-effects spline-estimated MoCA scores for 5-year age increments

| 60 | 65 | 70 | 75 | 80 | 85 | 90 | 95 | 100 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated MoCA score | 28.24 | 27.74 | 27.24 | 26.72 | 26.17 | 25.57 | 24.95 | 24.31 | 23.66 |

| Change from previous | na | −0.50 | −0.50 | −0.52 | −0.55 | −0.60 | −0.62 | −0.64 | −0.65 |

| Change from age 60 | na | −0.50 | −1.00 | −1.52 | −2.07 | −2.67 | −3.29 | −3.93 | −4.58 |

Age-Corrected MoCA Score = 35.34 + (−0.12 × age at assessment)

Fig. 2.

Mixed-effect spline model shows a linear trajectory of decline across the age span of cognitively normal older adults. Shaded area around regression line is 95% confidence band. Additional linear mixed-effects model yielded a prediction equation of: Age-Corrected MoCA Score = 34.35 + (−0.12 × age at assessment)

Discussion

These longitudinal results extend the findings of previous studies that characterized MoCA trajectory in older adults [9–12]. A linear trajectory of decline across the 60–99 age span was noted while at the individual level, MoCA scores can vary by approximately zero to three points between assessments among older adults. These results contrast with those reported by Suzuki et al. [10] whose parameters used to define stability (± 1 point change = stable, ≥+2 point change = improvement, ≥ − 2 point change = decline) were within the expected range of individual variation based on the ISD values we report here. Krishnan et al. [9] derived a reliable change index (RCI) for the MoCA and found that a change of ± 1.73 points is clinically meaningful. It is noted that this finding was based on a relatively small (n = 53) and young (age range 55–70) normative sample. Moreover, this reliable change value also falls within the range of year-to-year variation we found. Our results suggest that a 1-year change of at least four points on the MoCA is beyond the normal range of variation; however, it is unclear whether this actually represents clinically meaningful change.

One of the more positive attributes of this study is the inclusion of a relatively large number of octogenarians and nonagenarians. Given that these age groups are among the fastest-growing in the population [14] characterizing their normative trajectory and variability is important for both clinicians and researchers. Previous work by our group characterized cross-sectional normative performance in octogenarians and nonagenarians [6] and demonstrated that cognitively normal older adults often score below the original cutoff proposed in the validation study of the MoCA [1]. With regard to nonagenarians, their low performance may be explained by having less formal education relative to other age groups. In this study, 42% of the 90–99 age group had at least 16 years of education which is the lowest percentage among the age strata in this study. However, there is still a need to continue pursuing age-adjustment methods that provide better estimates of age-related MoCA performance. Specifically, methods that incorporate the degree of intraindividual variability would help in this regard. The longitudinal results presented in this study provide an extension to our cross-sectional findings [6] by characterizing the natural variability of MoCA scores over time in cognitively normal older adults.

The degree to which MoCA scores remained stable in this sample, particularly among the octogenarians and nonagenarians, is rather remarkable considering that the risk of developing AD is highest among those between the ages of 75 and 84 [15]. One possible reason for this might be a low prevalence of the APOE ε4 genotype among the individuals in this study. Although this cannot be verified since APOE genotyping is not yet carried out in the Longevity Study, it still serves as a possible explanation for the lack of decline noted in the group. In addition, the catchment area for this study is comprised of retirement communities where active lifestyles and continued social engagement are emphasized. As a result, the population from which participants were drawn is likely to be healthier and less likely to show decreased cognitive performance relative to the general population of older adults.

Recent neuroimaging evidence suggests that older individuals with superior cognitive function demonstrate greater thickness and connectivity in cortical regions and networks that are critical to memory and executive function [16]. The term “superagers” has been applied to these older adults as many of them demonstrate neuroanatomical findings that are consistent with individuals in their 20s and 30s [16]. This raises the possibility that individuals in our cohort may also have these neuroanatomical attributes which contributes to their ability to maintain cognitive function. Genetic contributions to longevity must also be considered [17] as it is likely that they are also factors that aid in the maintenance of cognitive function in advanced age. Sebastiani et al. [18] found that exceptional longevity was linked to a wide network of genes, each with varying isoforms that conferred differing levels of protection against age-related diseases. It is possible that these same gene networks may also offer protective benefits for cognition either through direct neuroprotective pathways or through a reduced risk of systemic disease (e.g. heart disease) that can also impact cognition. This, or a survivor effect, may also explain why individuals in the 90–99 age group performed relatively well on the MoCA as genetic profiles that confer increased longevity may also provide higher levels of protection against age-related and disease-related pathologies that negatively impact cognition.

There are some limitations to the current study. Our cohort is predominantly Caucasian with very few ethnic minorities which limits the generalizability of the results to more ethnically diverse populations. Rossetti et al. [7] demonstrated that Caucasians had significantly higher MoCA scores than other ethnic groups, so it is possible that the trajectories of scores may differ as well. Another limitation of this study is that our sample, as a whole, has higher socioeconomic and educational attainment than the general population, which may also limit the generalizability of these results to populations where high education levels are less prevalent.

The combination of group-level and individual-level results shown in this study will be of value to both clinicians and researchers. By characterizing both the natural trajectory and natural variability of MoCA performance, clinicians are better informed as to what constitutes normal age-related changes and researchers are provided with data that could aid in the design of trials for cognitive enhancing interventions [19, 20] and those that target Alzheimer’s disease pathology [21].

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent All participants signed an informed consent form prior to participating.

References

- 1.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, White-head V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H (2005) The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 53:695–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsu J-L, Fan Y-C, Huang Y-L, Wang J, Chen WH, Chiu HC, Bai CH (2015) Improved predictive ability of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment for diagnosing dementia in a community-based study. Alzheimer Res Ther 7:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damian AM, Jacobson SA, Hentz JG, Belden CM, Shill HA, Sab-bagh MN, Caviness JN, Adler CH (2011) The Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the Mini-Mental State Examination as screening instruments for cognitive impairment: item analyses and threshold scores. Dement Geriatr Cog Disord 31:126–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freitas S, Simões MR, Alves L, Santana I (2013) Montreal Cognitive Assessment: validation study for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 27:37–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciesielska N, Sokołowski R, Mazur E, Podhorecka M, Polak-Szabela A, Kędziora-Kornatowska K (2016) Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test better suited than the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) detection among people aged over 60? Meta-analysis. Psychiatr Pol 50:1039–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malek-Ahmadi M, Powell JJ, Belden CM, O’Connor K, Evans L, Coon DW, Nieri W (2015) Age-and education-adjusted normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in older adults age 70–99. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn 22:755–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossetti HC, Lacritz LH, Cullum CM, Weiner MF (2011) Normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in a population-based sample. Neurology 77:1272–1275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa AS, Reich A, Fimm B, Ketteler ST, Schulz JB, Reetz K (2014) Evidence of the sensitivity of the MoCA alternate forms in monitoring cognitive change in early Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 37:95–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishnan K, Rossetti H, Hynan LS, Carter K, Falkowski J, Lacritz L, Cullum CM, Weiner M (2017) Changes in Montreal Cognitive Assessment scores over time. Assessment 24:772–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki H, Kawai H, Hirano H, Yoshida H, Ihara K, Kim H, Chaves PH, Minami U, Yasunaga M, Obuchi S, Fujiwara Y (2015) One-year change in the Japanese version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment performance and related predictors in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 63:1874–1879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooley SA, Heaps JM, Bolzenius JD, Salminen LE, Baker LM, Scott SE, Paul RH (2015) Longitudinal change in performance on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in older adults. Clin Neuropsychol 29:824–835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paul R, Lane EM, Tate DF, Heaps J, Romo DM, Akbudak E, Niehoff J, Conturo TE (2011) Neuroimaging signatures and cognitive correlates of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment screen in a nonclinical elderly sample. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 26:454–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Connor K, Coon DW, Malek-Ahmadi M, Dugger BN, Schofield S, Nieri W (2016) Description and cohort characterization of the Longevity Study: learning from our elders. Aging Clin Exp Res 28:863–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H (2014) An aging nation: The older population in the United States: Population estimates and projections, current population reports http://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25–1140.pdf. Accessed 3 May 2017

- 15.Alzheimer’s Association (2016) Alzheimer’s disease facts and Figs 2016. https://www.alz.org/documents_custom/2016-facts-and-figures.pdf. Accessed 3 May 2017

- 16.Sun FW, Stepanovic MR, Andreano J, Barrett LF, Touroutoglou A, Dickerson BC (2016) Youthful brains in older adults: preserved neuroanatomy in the default mode and salience networks contributes to youthful memory in superaging. J Neurosci 36:9659–9668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodríguez-Rodero S, Fernández-Morera JL, Menéndez-Torre E, Calvanese V, Fernández AF, Fraga MF (2011) Aging genetics and aging. Aging Dis 2:186–195 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sebastiani P, Solovieff N, DeWan AT, Walsh KM, Puca A, Hartley SW, Melista E, Andersen S, Dworkis DA, Wilk JB, Myers RH, Steinberg MH, Montano M, Baldwin CT, Hoh J, Perls TT (2012) Genetic signatures of exceptional longevity in humans. PLoS One 7:e29848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Os Y, de Vugt ME, van Boxtel M (2015) Cognitive interventions in older persons: do they change the functioning of the brain?. Biomed Res Int 2015:438908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams K, Kemper S (2010) Exploring interventions to reduce cognitive decline in aging. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 48:42–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brookmeyer R, Kawas CH, Abdallah N, Paganini-Hill A, Kim RC, Corrada MM (2016) Impact of interventions to reduce Alzheimer’s disease pathology on the prevalence of dementia in the oldest-old. Alzheimers Dement (NY) 12:225–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]