Introduction

The digital and hand replantation has progressed after the first replantation of a completely amputated digit by Japanese orthopedic surgeons, Tamai and Komatsu in 1965, which was reported in 1968.1 With the advancement of microsurgery techniques and instrumentation, replantation is effective in treating digital and hand amputations. Successful digital and hand replantation can provide excellent aesthetic outcomes by maintaining the digit number and length. However, replantation should not be routinely done without considering postoperative functional outcomes. For example, a severely injured digit involving multiple tissue, usually more than three injured categories per five tissue in digital and hand components (bone or joint, tendon, vessels, nerves, and skin), may be considered a contraindication for replantation given its presumed poor functional outcomes. Achieving best outcomes after replantation is not solely related to the success of the microvascular anastomosis itself, but also to the adequacy of bone fixation, tendon and nerve repair, and soft-tissue coverage. The aim of this article is to review the literature relating to surgical technique and recent evidence in microsurgical digital and hand replantation, and describe our surgical pearls for overcoming various pitfalls.

Indications and Contraindications for Replantation

There is much controversy regarding the indications and contraindications for digital and hand replantation. Because there are multiple factors to consider (e.g. patient’s age, occupation, dominant hand, severity and level of injury, warm ischemia time, general condition, motivation, economic factors), the final decision regarding replantation depends on the surgeons and patients. Moreover, suitability of this procedure is usually done under the microscope in the operation theater after inspecting the amputated digit and proximal stump. Although it is difficult to definitively specify the indications for replantation, there are several rules that help the decision. First, replantation is only considered in a stable patient. In case of life-threatening associated injuries, replantation should be avoided. Second, amputated levels and digital numbers and patient background are important. Thumb, multiple digit, or transmetacarpal amputations are considered as strong indications for replantation.2 There is no age limitation for replantation. However, patients with diabetes mellitus or obliterative vascular diseases, or smoking have a higher failure rate.3,4 Patients with active psychiatric illness or self-amputation should be contraindications. On the other hand, any pediatric amputation is considered for replantation, because children have good potential for recovery and regeneration, resulting in better functional outcomes than adults.5 Our indications for digital and hand replantation based on injury and patient factors are summarized in Table 1. Third, the severity of injury that can achieve good outcomes after replantation include: (1) Guillotine: clean and sharp amputation (e.g., knife), (2) crush amputation (e.g., saw) with minimal local tissue damage, and (3) avulsion amputation (e.g., machine press or door) with minimal vascular injury. Guillotine is favorable for replantation, on the other hand, crush or avulsion injuries are less likely to be salvageable. Predictive signs of severe vascular injury of amputated digits, “red line sign (small hematomas seen in the skin along the course of the neurovascular bundle)” (Figure 1) and “ribbon sign (a corkscrew appearance of the arteries)”, are considered as contraindication of replantation because of extensive zone of injury. Fourth, Replantation should be undertaken emergently to minimize ischemia time and maximize clinical outcomes. Warm ischemia time for a successful digit (no muscle) replantation should be up to 12 hours and cold ischemia of 24 hours.6 However, with a hand amputation, ischemia time is shorter because of muscle necrosis that can produce myoglobinuria, acidosis, and hyperkalemia after reperfusion. Thus, minimizing warm ischemia and total ischemia time is crucial for successful replantation.

Table 1:

Indications for Replantation

| Strong Indications | |

| Patients Factors | Any pediatric amputation |

| Injury Factors | Thumb amputation |

| Multiple digital amputations | |

| Transmctacarpal amputation | |

| Relative Indications | |

| Patients Factors | Special needs (e.g., musician, craftworker’s dominant hand, young lady, small finger replantation in Japan) |

| Injury Factors | Single digital Zone I amputation |

| Ring finger avulsion injury |

Figure 1:

Red line sign

Small hematomas can be seen in the skin along the course of the neurovascular bundle (black arrow).

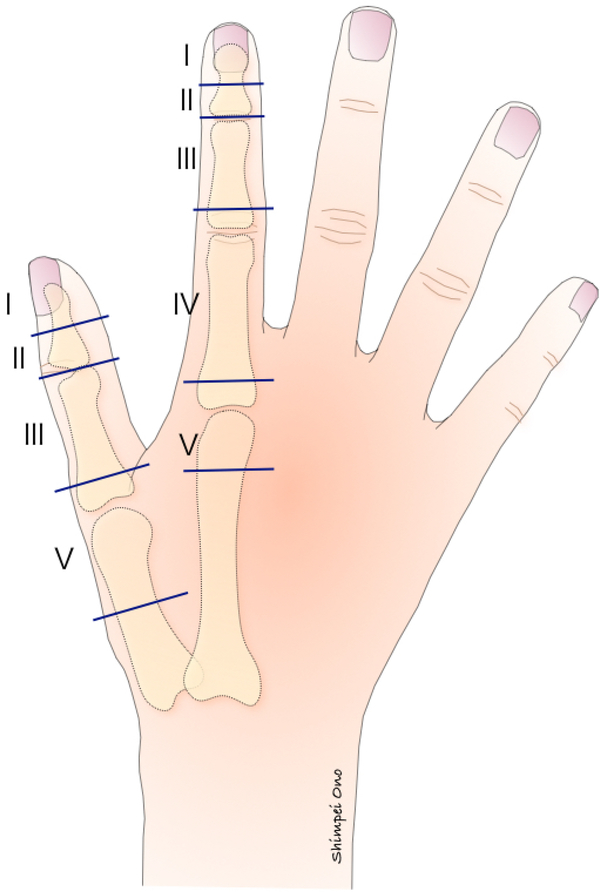

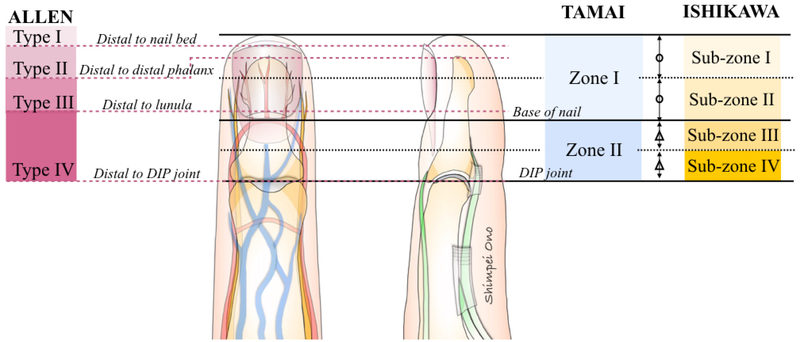

Classifications Based on the Level of Amputation

Amputations can be classified based on the anatomical level of amputation. Upper extremity amputations can be classified into two groups: major amputation (amputations proximal to the radiocarpal joint) and minor amputation (amputations distal to the radiocarpal joint). With regards to digital amputation, Tamai’s classification7 is the most frequently used system. He classified digital amputation into five zones (Figure 2). Each zone has anatomic characteristics that influence the technique and outcome of replantation. Fingertip amputation has been classified by many authors (Figure 3).7–9 Tamai’s classification of zone 1 (from the fingertip to the base of the nail) and zone 2 (from the base of the nail to the distal interphalangeal joint) are also used for amputation classification of the fingertip.

Figure 2:

Tamai’s classification of fingertip amputation

Figure 3:

Classifications of distal digital amputations.

DIP: distal interphalangeal

Ishikawa et al. subdivided Tamai’s classification into four subzones: subzone I the distal to the midpoint of the nail, subzone II from the nail base to the midpoint of the nail, subzone III from midway of the nail base and DIP joint to the nail base, subzone IV from the DIP joint to the midway point.

A Step-by-Step Operative Approach

1). STEP 1: Emergency Management and Care of the Amputated Digit

On arrival into the emergency care unit, a complete trauma assessment is essential; life-threatening conditions must be investigated and controlled. Most digital and hand amputation patients are initially cared by non-specialists, before referral to hand surgery centers or microsurgical units. Appropriate initial management is a key factor of good outcomes. Actively bleeding vessels at stump are never be clamped and should be controlled with hand elevation and external gauze pressure to avoid additional vessels damage (Figure 4) 10. The amputated digit and hand should be immediately wrapped in a saline-moistened gauze (Figure 5), placed in a plastic bag (Figure 6), in a container with ice and water (approximately at 4°C). Cooling below 4° C, ice in direct contact with the tissue, causes frostbite damages.11 Thus care must be taken so that the amputated segment does not come in direct contact with the ice (Figure 7). Radiographic examination of the hand and the amputated segment should be performed to evaluate the extent of the bone injury (Figure 8).

Figure 4:

Bleeding vessels at stump should be controlled with external gauze pressure to avoid additional vessels damage.

Figure 5:

Amputated digit should be immediately wrapped in a saline-moistened gauze.

Figure 6:

Amputated digit in a saline-moistened gauze (black arrow) placed in a plastic bag.

Figure 7:

A plastic bag with amputated segment is placed in a container. Particular care must be taken so that the amputated segment does not come in direct contact with the ice (asterisk).

Figure 8:

Radiographic examination of the amputated segment should be performed to evaluate the extent of the bone injury.

A two-team approach is ideal; while one team evaluates and prepares the patient, and the other assesses the amputated segment. Ideally, the amputated segment is taken immediately to the operating room to be examined under microscope or loupe magnification (Figure 9). The amputated segment is then dissected to expose important structures (arteries, veins, and nerves), and they are tagged with sutures of 9–0 or 10–0 nylon.

Figure 9:

The amputated segment is taken to the operating room to be examined under microscope and dissected to allow exposure of important structures such as digital artery (black arrow).

2). STEP 2: Anesthesia

Replantation surgery is usually performed under regional anesthesia, axillary nerve block, alone or in combination with general anesthesia. Regional anesthesia provides the benefit of sympathetic blockade, which optimizes vasodilatation and facilitates vascular anastomosis.12 Moreover, the regional anesthesia can be maintained in the postoperative period.

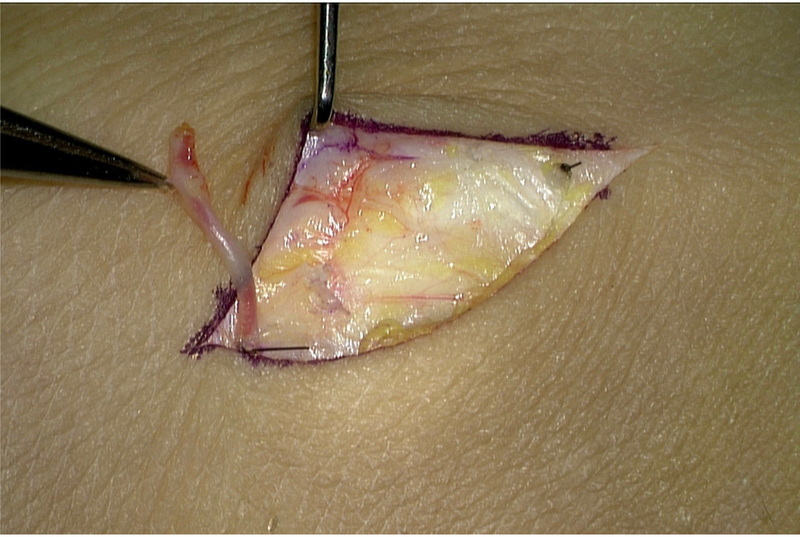

3). STEP 3: Preparation of Proximal Stump

A tourniquet is used during the course of the dissection in the proximal stump. Midlateral incisions (Figure 10) provide a rapid and excellent exposure for the dorsal veins located just above the extensor tendons and volar neurovascular bundle. The flexor tendons are retracted proximally; they are retrieved and held out to length, by transfixing them with 23G needles. The artery is located dorsal to the nerve in the digit, whereas the common digital artery is volar to the common digital nerve in the palm. Each end is identified and tagged before skeletal fixation.

Figure 10:

Midlateral incisions are utilized for exposure to raise volar and dorsal skin flaps.

4). STEP 4: Order of Repair

After all vital structures have been identified, repair is begun. Two methods are available when multiple digits are replanted. One is “digit-by-digit”, wherein each digit is replanted one after the other. The other method is the “structure-by-structure”;13 skeletal fixation of all digits is done first, and the extensors, flexors, palmar arteries and nerves, and dorsal veins are then repaired in this order. The author prefers the “structure-by-structure” method to reduce operation time and avoid accidental damage to repaired adjacent neurovascular structures. The logical sequence of replantation is to progress from the deeper structures to superficial structures: (a) bone stabilization, (b) repair extensor tendons, (c) repair flexor tendons, (d) repair arteries, (e) repair nerves, (f) repair veins, and (g) close or cover wound. In the case of excess tension at the anastomosis site, vein grafts should be harvested from volar aspect of wrist to provide tension-free anastomoses (Figure 11).

Figure 11:

Vein grafts harvested from volar aspect of wrist

5). STEP 5: Bone Stabilization

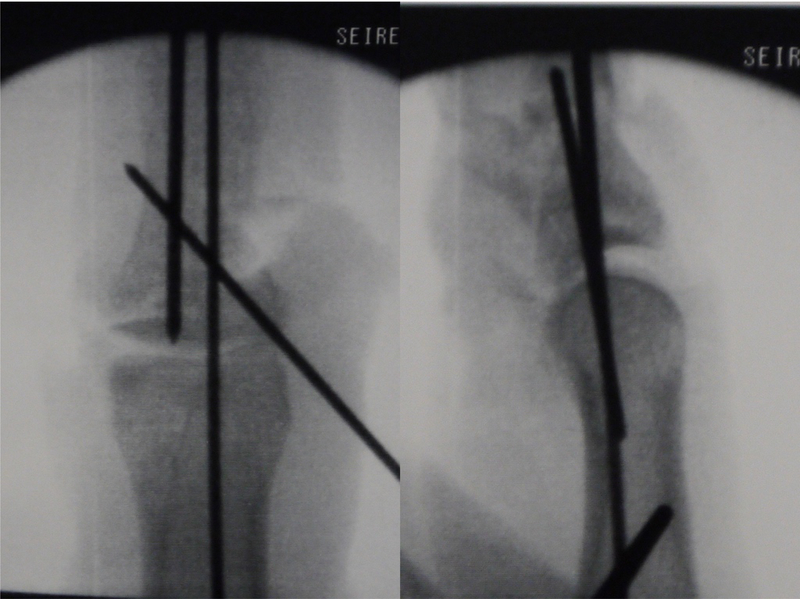

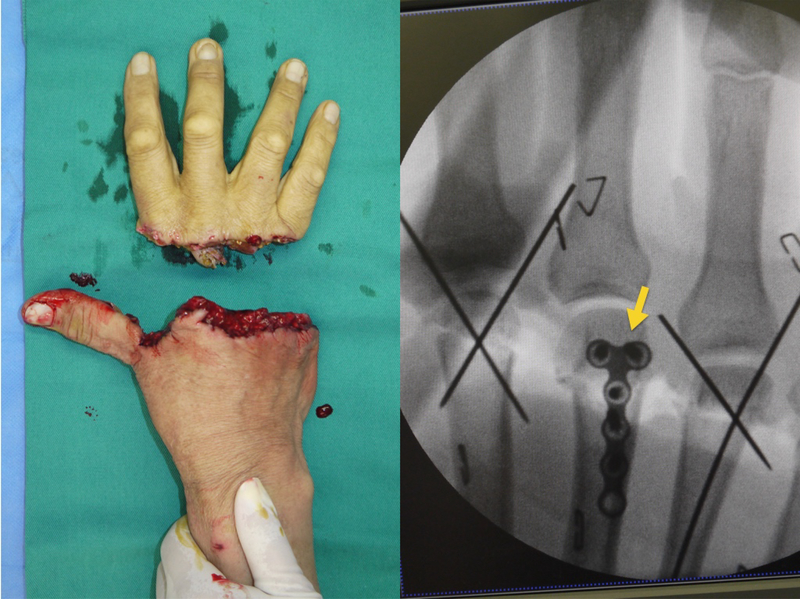

Digital and hand replantation requires bone stabilization first. Various bony stabilization methods are available: Kirschner (K-) wire, intraosseous wiring, screw, peg, and small plate. Digital amputations at the distal or middle phalanx are most often secured with single or crossed K-wires (Figure 12) and at the proximal phalanx with crossed K-wires or intraosseous wiring. Care must be taken to avoid twisting the neurovascular bundle or tethering the tendons by the K-wires. On the other hand, transmetacarpal amputations often require mini-plate fixation (Figure 13) for rigid fixation strong enough to withstand the rigors of hand therapy after replantation surgery. Wires and plates should be placed to allow joint motion, if possible. Care should be taken to achieve anatomical alignment and correct rotation of the replanted segments. Bone shortening is one of the methods to make replantation easier and permits tension-free vascular anastomosis and nerve repairs. The amount of bone shortening depends on the extent of involved tissue. Less than 0.5–1.0 cm in the digits and 2–4 cm hand is safer to prevent postoperative functional impairment.

Figure 12:

Crossed K-wires were used to obtain skeletal fixation.

Figure 13:

Mini-plate (yellow arrow) for skeletal fixation in transmetacarpal amputation

6). STEP 6: Tendon Repair

After rigid bony stabilization is performed, the extensor and flexor tendon repair is performed. Extensor tendons are repaired with figure-of-eight, horizontal mattress, or (locked) running suture of 5–0 or 4–0 nylon. Repair of the intrinsic tendons, lateral bands, is important for extension of distal interphalangeal joints.

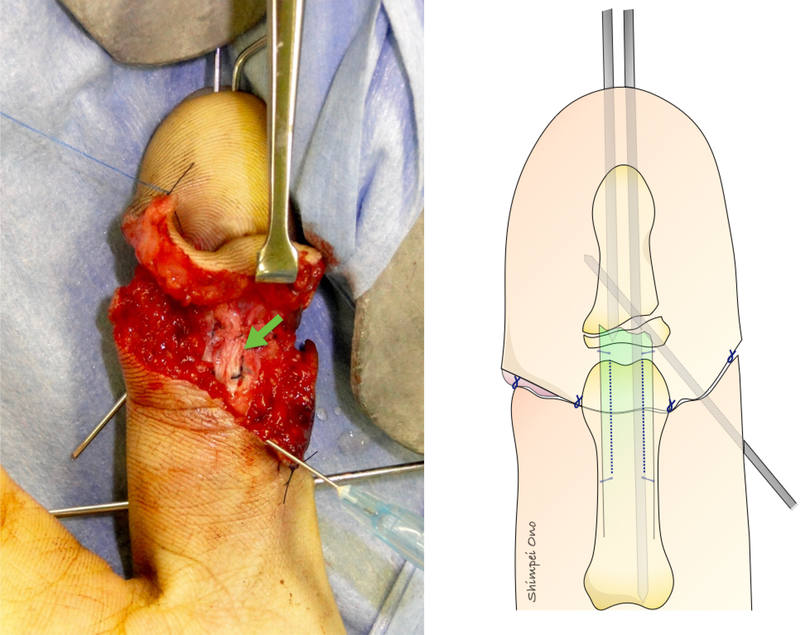

After the extensor mechanism repair, flexor tendons are then repaired (Figure 14). As to flexor tendons, primary repair is the rule. However, secondary repair, usually the two-stage silicone rod method is required in some cases. Four-strand core sutures are now used for primary flexor tendons repair. We prefer to use 4-stand modified Kessler of 4–0 double-loop sutures for making core sutures. In zone II level amputation, only the profundus tendon is repaired to avoid adhesions between the superficialis and profundus tendon. Some surgeons prefer to repair not only the profundus but also a half-slip of the superficialis to improve postoperative motion when compared to single profundus fingers. Subsequent tenolysis may be required 6 months after replantation.

Figure 14:

Repaired flexor tendon (green arrow)

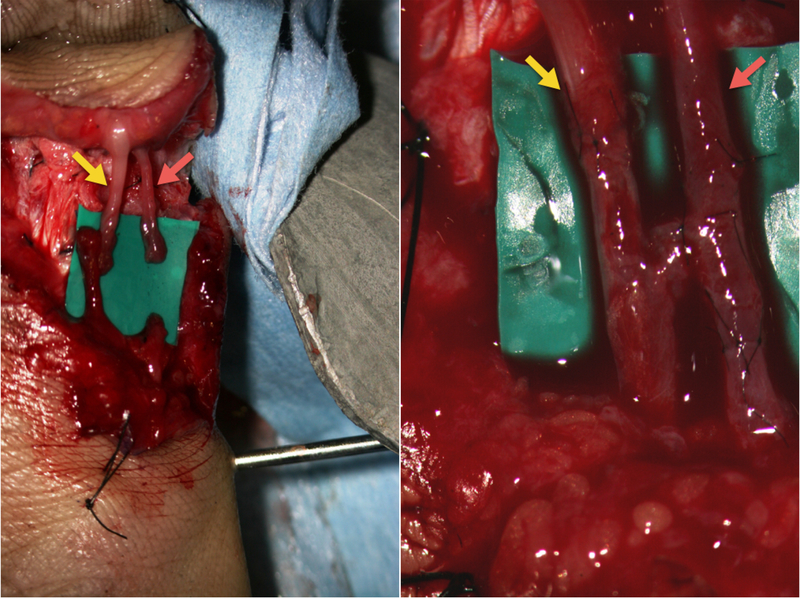

7). STEP 8: Vessel and Nerve Repair

Once tendons are repaired, arteries are anastomosed (Figure 15). Some surgeons recommend repairing all the arteries that can be restored; however, one digital artery repair for one digit is enough for replantation and can save total operation time. If one digital artery is repaired, the dominant artery should be repaired if selectable. In the thumb, index, long, and ring fingers, the ulnar digital artery is dominant, whereas the small finger the radial artery is dominant. I possible, multiple venous anastomoses are recommended to improve outflow and increase chances of survival. Although bone shortening is useful for tension-free vessels anastomosis, vein grafts are often required for bypassing vasospastic or damaged segments of vessels at the amputation site. Vein grafts are usually harvested from volar wrist or dorsal foot, which are similar in caliber to digital vessels, whereas saphenous veins are suitable for hand vessels. The damaged artery has separation of the endothelial layer, and must be resected until normal intima is visualized. Insufficient resection and arterial tension repair without vein grafts decrease the survival rate. Moreover, arterial anastomosis should not be done until identifying spurting and pulsating arterial flow from proximal arteries. If vasospasm of proximal arteries is identified, (a) relief of arterial tension or compression, (b) warming of the room, patient, and proximal artery, (c) gentle intraluminal flushing with papaverine (1:20 dilution), (d) continuous intravenous prostaglandin E1 (PGE1), and (e) waiting, are useful methods for vasodilatation.

Figure 15:

Tension-free arterial anastomosis using a vein graft (red arrow) and nerve repair (yellow arrow)

The digital nerves are then repaired (Figure 15) because they are located in the same surgical field. After the bone shortening, nerve repair is easy because there is no tension at the suture site. In the digital nerve repair, two or three epineural sutures with 9–0 to 10–0 nylon are necessary. If a nerve defect occurs, autologous nerve grafting is usually performed. The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve or posterior interosseous nerve is ideal as a donor for digital nerve grafting whereas the sural nerve best matches the common digital nerve. However, the use of autologous nerve grafts carries the risk of donor-site morbidity including sensory loss, neuroma, and scar. Recently, artificial nerve conduit repair can be chosen for replantation treatment of the nerve defect, when direct tension-free coaptation is not possible (Figure 16). Further studies are required to estimate its role in nerve reconstruction for digital and hand replantation.14

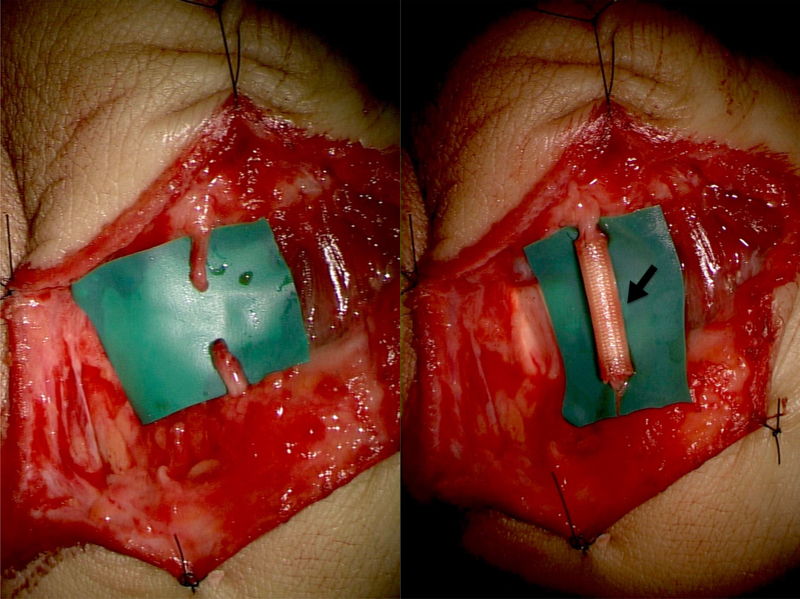

Figure 16:

Artificial nerve conduit (black arrow) repair for nerve defect

After the arteries and nerves are repaired, dorsal veins are anastomosed finally (Figure 17). It is very difficult to find the dorsal veins because they are usually collapsed. Thus, by releasing the arterial clamps, the veins will enlarge and be easier to find. Before releasing the arterial clamps, a bolus of 3000U heparin is injected intravenously. When the dorsal veins are not available for repair, the thin, smaller volar veins can be used. Ideally, two vein repairs are necessary for one arterial repair.

Figure 17:

Venous anastomosis on the dorsal side

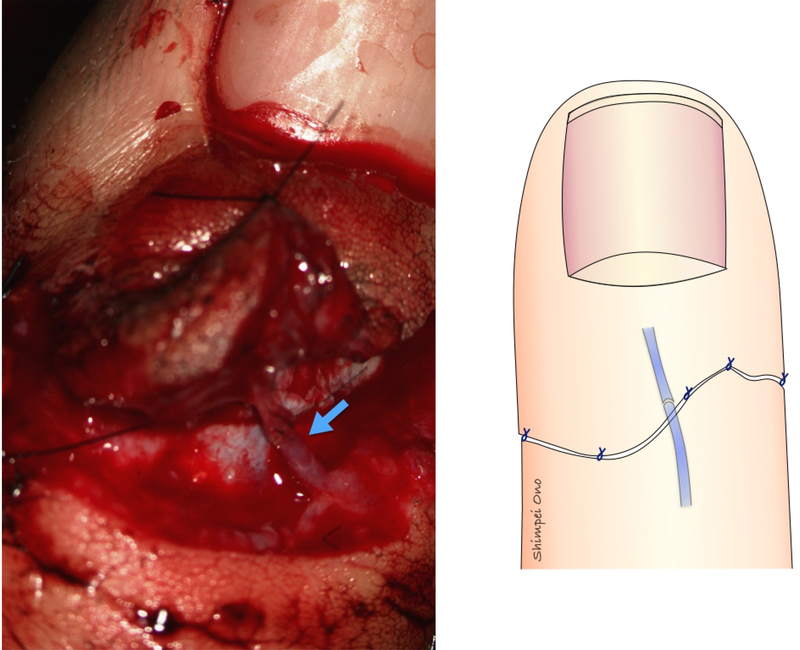

8). STEP 9: Skin Closure

The skin is closed loosely with a few interrupted nylon sutures (Figure 18). Small defects, less than 1cm in a diameter, can be covered with artificial dermis (Figure 19). If skin defects are large, a local flap or split-thickness skin grafts may be required. A large volar defect with an arterial defect can be reconstructed by a venous flap harvested from the volar wrist as a flow-through flap.15

Figure 18:

Skin closure with a few interrupted nylon sutures

Figure 19:

Small defects can be covered with artificial dermis (black arrow)

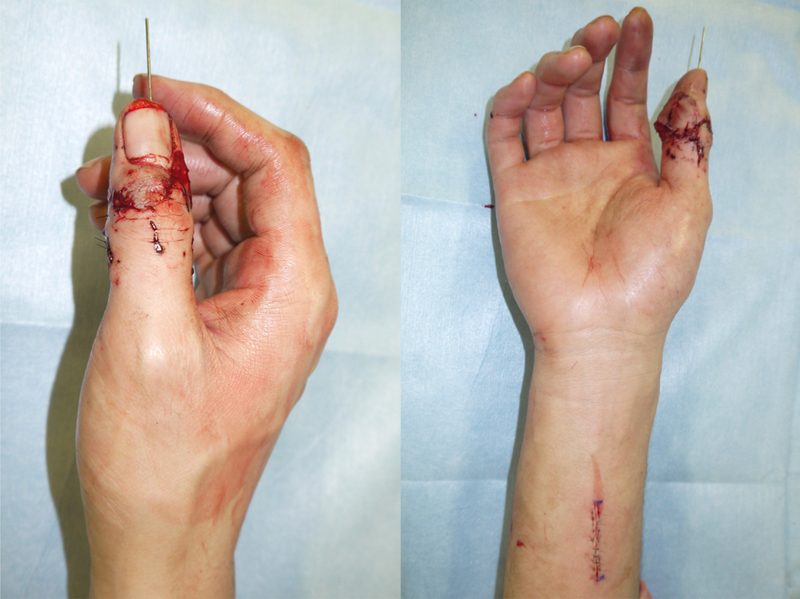

9). STEP 10: Postoperative Care

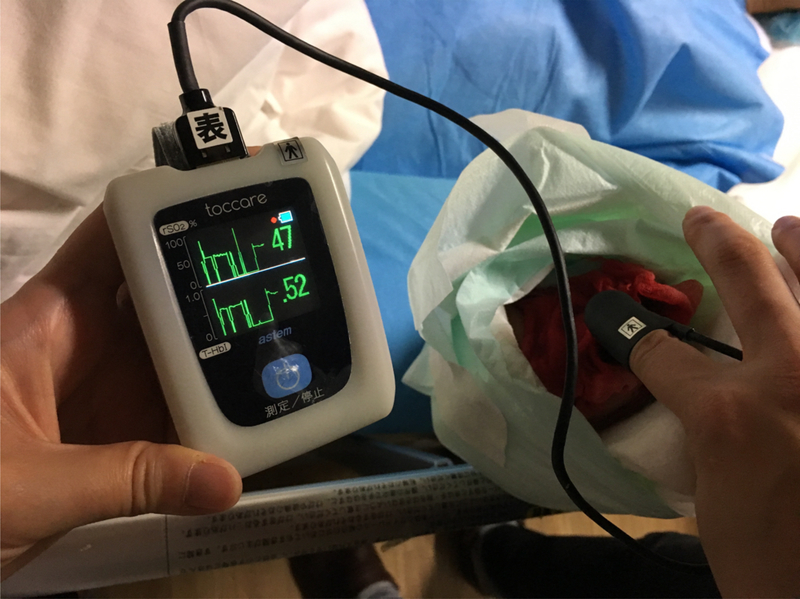

A bulky and non-compressive dressing, and dorsal plaster splint are applied for postoperative protection and comfort. The affected hand is kept elevated above the heart or slightly higher to increase circulation. The fingertips and small area of skin are left exposed for evaluation of the circulation (Figure 20). To improve success rate in replantation, postoperative management is very important. Skin color, temperature, turgor, and capillary refilling time should be monitored closely and frequently; every 1–3 hour for the first 24 hours, then every 6–8 hours till the fifth postoperative day (Table 2). More objective and quantitative evaluation can be measured with transcutaneous oxygen measurements, an easy and reliable method to predict the viability of the tissue (Figure 21). The patient is kept warm, well hydrated. Pain and anxiety are controlled to avoid adrenergic response and vasoconstriction. Smoking and caffeinated drinks are prohibited. The use of anticoagulants is controversial. The authors do not use postoperative anticoagulation routinely because there is no prospective randomized data to support a standard regimen of any of these medications. One exception is the crush or avulsion injury, for which intravenous heparin, 1000 U per hour, is used for five to seven days.

Figure 20:

Small area of skin is left exposed for evaluation of the circulation.

Black arrow: heparin-soaked gauze

Table 2:

Indicators for Arterial and Venous Crisis

| Indicators for Vascular Crisis | Arterial Crisis (arterial vasospasm or thrombosis) | Venous Crisis (venous thrombosis) |

|---|---|---|

| Skin Color | White, Pale | Dark purple |

| Skin Temperature | Decreased | First high then low |

| Skin Turgor | Decreased tension | Increased tension |

| Capillary Refilling Time | Prolonged (>2 seconds) | Shorten (<1 second) |

| Pin-prick Test | Slow and decreased bleeding | Fast and excessive bleeding |

Figure 21:

Transcutaneous oxygen measurements are an easy and reliable method to predict the viability of the tissue

If there is a suspicion of vascular crisis (arterial or venous insufficiency), the patient is immediately transferred to the operating room for exploration of the vascular anastomosis. Early recognition of vascular crisis is essential for improving outcomes of replantation surgery. In patients with arterial obstruction, there is usually a thrombosis of an anastomosis that invariably requires re-anastomosis or vein grafting. In patients with venous obstruction, the solutions are: a fish-mouth incision, dermal de-epthelization, periodic puncture of the fingertip, continuous nail bed bleeding by removing a portion of the nail bed, use of medical leeches, and heparin-soaked gauze dressing to the wound. These methods are more useful in distal replants. Postoperative two-month view is shown in Figure 22.

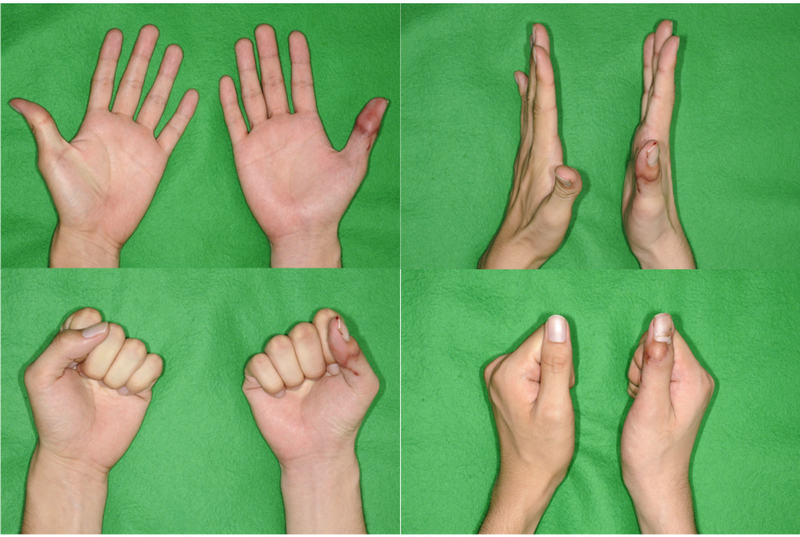

Figure 22:

A two-month postoperative view

Outcomes

Functional outcomes depend on the level of amputation. In general, the more distal the amputation, the better the functional result of replantation. A recent systematic review by Sebastin et al.16 shows that the outcomes for distal digital replantation are: the mean 86% survival rate, the mean of 7 mm two-point discrimination (2-PD), 98% returned to work, complications include pulp atrophy in 14% and nail deformity in 23%. For more proximal digital amputations, the outcomes are similar, with reported survival rates between 80–90%17–19 and an average 2-PD of 8 to 15 mm.20 Range of motion is also related to amputation level. Active PIP joint motion in replantation proximal to the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) insertion results in 35 degrees, whereas distal to the FDS insertion results in 82 degrees.21 For transmetacarpal amputations, the survival rate is relatively high (86–90%), however, the functional outcomes are poorer: the sensory recovery is poor (78% achieved 2-PD, among those the mean 2-PD was 14.7 mm), less than 50% returned to previous work, and the mean total active motion (TAM) is 109–154 degrees. Interestingly, despite these poorer outcomes, patient satisfaction with the replantation surgery is high.22,23

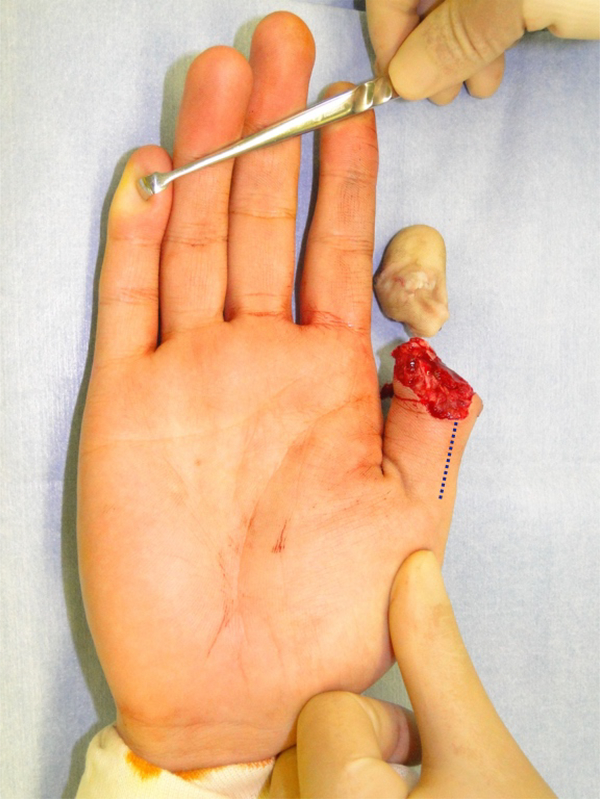

Fingertip Replantation

Fingertip is defined as the distal to the flexor and extensor tendon insertion site on the distal phalanx. Fingertip amputation was traditionally considered to be a contraindication for replantation. However, after the first report by Yamano,24 recent studies have shown high survival rates (>80–90%)16 and excellent functional and aesthetic outcomes, providing a high degree of patient satisfaction. Nowadays it is recognized that successful fingertip replantation is superior to any other reconstructive choice.25 Fingertip replantation is more demanding than proximal digital replantation because veins are very small and sometime difficult to find. If a suitable vein cannot be found, artery-only fingertip replantation is a good treatment option (Figure 23); however, venous congestion is an inevitable phenomenon. Venous congestion of replanted segment can be managed by pin-prick every 3–6 hours for 5–7 days, but survived fingertip often become painful with atrophy (Figure 24). Several methods have been described to prevent venous congestion until internal circulation is established: removal of the nail bed,26 use of medical leeches,27 and heparin-soaked gauze dressing. Koshima et al. has devised two useful methods; arteriovenous anastomosis28 to eliminate venous drainage and delayed venous repair29 (arterial anastomosis first and veins get engorged after 24 hours). Some surgeons mentioned that obligatory external bleeding to restore venous outflow is not always necessary and venous outflow could be managed by the bleeding that occurred from wound-edge and bone marrow reflux.30,31

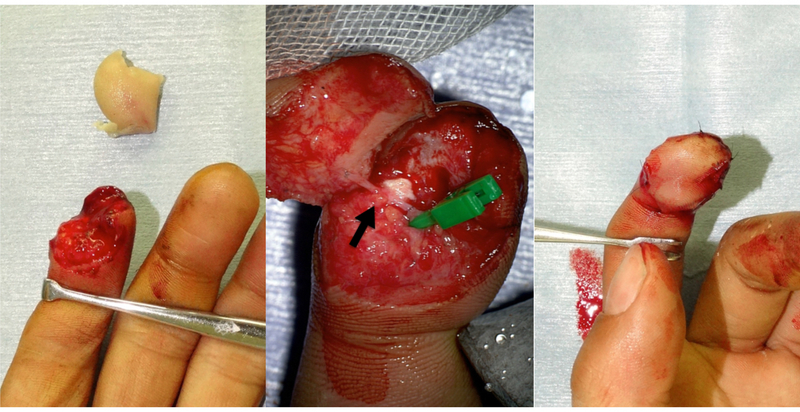

Figure 23:

Artery-only fingertip replantation of zone I digital amputation

Black arrow: Reconstructed artery with a vein graft

Figure 24:

Artery-only fingertip replantation of zone II digital amputation

Venous congestion of replanted segment can be managed by pin-prick venous drainage, but survived fingertip often become painful with atrophy.

Black arrow: Venous drainage by pin-prick at the wound-edge

Other useful choice of fingertip replantation is cap technique32 and pocket-plasty,33 non-microsurgical reattachment. These techniques strive to augment venous outflow. The cap technique enhances composite graft survival by increasing the contact surface between the distal amputated fingertip and the stump. The pocket-plasy involves de-epithelializing the pulp and a suitable site on the palm and suturing them together. The pulp and palm are separated two to three weeks later after the initial operation.

CONCLUSIONS

Surgical technique and recent evidence in microsurgical digital and hand replantation are comprehensively reviewed. Best outcomes after replantation are not solely related to the success of the microvascular anastomosis, but also to the functional and aesthetic outcomes. More prospective studies are necessary to evaluate the quality of life, patient’s satisfaction, and cost-effectiveness of replantation compared with revision amputation.

KEY POINTS.

One should consider multiple factors when conducting replantation: patient’s age, occupation, hand dominance, severity and level of injury, warm ischemia time, general condition, motivation, economic factors.

Strong indications to replantation include: thumb, multiple digits, transmetacarpal and proximal, and any pediatric amputations whatever the level.

For successful replantation, we emphasize the usefulness of two-team approach, bone shortening, tension-free anastomosis, and vein graft. Early recognition of postoperative vascular compromise is also important.

Recent studies have shown that high survival rates after fingertip replantation by providing excellent functional and aesthetic outcomes. Artery-only fingertip replantation requires several methods to restore venous outflow: removal of the nail bed, use of medical leeches, and heparin-soaked gauze dressing.

SYNOPSIS.

In this article, we comprehensively reviewed literature relating to surgical techniques and recent evidence in microsurgical digital and hand replantation. Successful replantation can provide excellent aesthetic outcomes by maintaining the digital number and length. However, replantation should not be done routinely without considering postoperative functional outcomes. Achieving best outcomes after replantation is not solely related to the success of the microvascular anastomosis, but also to the adequacy of bone fixation, tendon and nerve repair, and soft-tissue coverage. With an advancement of microsurgery, replantation surgery has now become a routine procedure. However, little is known about the decision-making process in treatment for digital and hand amputation. A well-designed study is desired to compare the outcomes of digital and hand amputations treated with either replantation or revision amputation. Additionally, outcome assessment includes not only function but also patient-reported outcomes that include quality of life and patient’s satisfaction, and cost-effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Funding sources: Supported in part by grants from a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (2 K24-AR053120–06)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Komatsu S, Tamai S. Successful replantation of a completely cut-off thumb: Case report. Plast Reconstr Surg 1968;42:374–377. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung K, Alderman A. Replantation of the upper extremity: Indications and outcomes. J Am Soc Surg Hand 2002;2:78–94. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleinert HE, Juhala CA, Tsai TM, et al. Digital replantation-selection, technique, and results. Orthop Clin North Am 1977;8:309–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dec W A meta-analysis of success rates for digit replantation. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg 2006;10:124–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng GL, Pan DD, Zhang NP, et al. Digital replantation in children: a long-term follow-up study. J Hand Surg Am 1998;23:635–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Beek AL, Kutz JE, Zook EG. Importance of the ribbon sign, indicating unsuitability of the vessel, in replanting a finger. Plast Reconstr Surg 1978;61:32–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tamai S Twenty years’ experience of limb replantation--review of 293 upper extremity replants. J Hand Surg 1982;7A:549–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen MJ. Conservative management of fingertip injuries in adults. Hand 1980;12:257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishikawa K, Ogawa Y, Soeda H, Yoshida Y. A new classification of the amputation level for the distal part of the fingers. J Jpn Soc Microsurg 1990;3:54–62. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilhelmi BJ, Lee WP, Pagenstert GI, et al. Replantation in the mutilated hand. Hand Clin 2003;19:89–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sapega AA, Heppenstall RB, Sokolow DP, et al. The bioenergetics of preservation of limbs before replantation. The rationale for intermediate hypothermia. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1988;70:1500–1513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maricevich M, Carlsen B, Mardini S, et al. Upper extremity and digital replantation. Hand 2011;6:356–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camacho FJ, Wood MB. Polydigit replantation. Hand Clin 1992;8:409–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paprottka FJ, Wolf P, Harder Y, et al. Sensory recovery outcome after digital nerve repair in relation to different reconstructive techniques: meta-analysis and systematic review. Plast Surg Int 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pederson WC. Upper extremity microsurgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 220;107:1524–1537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sebastin SJ, Chung KC. A systematic review of the outcomes of replantation of distal digital amputation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;128:723–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshizu T, Katsumi M, Tajima T. Replantation of untidily amputated finger, hand, and arm: experience of 99 replantations in 66 cases. J Trauma 1978;18:194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng GL, Pan DD, Qu ZY, et al. Digital replantation. A ten-year retrospective study. Chin Med J 1991;104:96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waikakul S, Sakkarnkosol S, Vanadurongwan V, Un-nanuntana A. Results of 1018 digital replantations in 552 patients. Injury 2000;31:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glickman LT, Mackinnon SE. Sensory recovery following digital replantation. Microsurgery 1990;11:236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urbaniak JR, Roth JH, Nunley JA, et al. The results of replantation after amputation of a single finger. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1985;67A:611–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinzweig N, Sharzer LA, Starker I. Replantation and revascularization at the transmetacarpal level: long-term functional results. J Hand Surg Am 1996;21:877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paavilainen P, Nietosvaara Y, Tikkinen KA, et al. Long-term results of transmetacarpal replantation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2007;60:704–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamano Y Replantation of the amputated distal part of the fingers. J Hand Surg Am 1985;10:211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yabe T, Tsuda T, Hirose S, et al. Treatment of fingertip amputation: comparison of results between microsurgical replantation and pocket principle. J Reconstr Microsurg 2012;28:221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yabe T, Muraoka M, Motomura H, et al. Fingertip replantation using a single volar arteriovenous anastomosis and drainage with a transverse tip incision. J Hand Surg Am 2001;26:1120–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han SK, Chung HS, Kim WK. The timing of neovascularization in fingertip replantation by external bleeding. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002;110:1042–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koshima I, Soeda S, Moriguchi T, et al. The use of arteriovenous anastomosis for replantation of the distal phalanx of the fingers. Plast Reconstr Surg 1992;89:710–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koshima I, Yamashita S, Sugiyama N, et al. Successful delayed venous drainage in 16 consecutive distal phalangeal replantations. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005;115:149–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka K, Kobayashi K, Murakami R, et al. Venous drainage through bone marrow after replantation: an experimental study. Br J Plast Surg 1998;51:629–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peterson SL, Peterson EL, Wheatley MJ. Management of fingertip amputations. J Hand Surg Am 2014;39:2093–2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rose EH, Norris MS, Kowalski TA, et al. The “cap” technique: nonmicrosurgical reattachment of fingertip amputations. J Hand Surg Am 1989;14:513–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brent B Replantation of amputated distal phalangeal parts of fingers without vascular anastomoses, using subcutaneous pockets. Plast Reconstr Surg 1979;63:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]