Abstract

BACKGROUND

Microvascular dysfunction (MVD) is a potential cause of chest pain in younger individuals. We hypothesized that non-elderly patients referred for computed tomography coronary angiography (CTA) but without significant stenosis would have a high prevalence of MVD by myocardial contrast echocardiography (MCE). Secondary aims were to test whether the presence of non-obstructive CAD or reduced brachial flow-mediated dilation (FMD) predicted MVD.

METHODS

Subjects ≤60 years-of-age undergoing CTA were recruited if they had either no evidence of coronary plaque, or evidence of mild CAD (<50% stenosis) and at least one high-risk plaque feature. Subjects underwent quantitative MCE perfusion imaging at rest and during regadenoson vasodilator stress. Microvascular dysfunction was defined by global or segmental delay of microvascular refill (≥2 seconds) during regadenoson. FMD of the brachial artery was also performed.

RESULTS

Of the 29 patients in whom MCE could be performed, 12 subjects (41%) had MVD. These subjects compared to those with normal microvascular function had lower hyperemic perfusion (Aβ) (236±68 vs 354±161 IU/s, p=0.02) and microvascular flux rate (β) (1.6±0.4 vs 2.5±0.9 s−1, p=0.002) on quantitative MCE. The degree of FMD was not significantly different in those with or without MVD (11±4 vs 9±4 %, p=0.32), and there was a poor correlation between stress MCE results and FMD. Only eight of the 29 subjects were classified as having non-obstructive CAD. There were no group-wise differences in the prevalence of MVD function in those with versus without CAD (43% vs 38% for CTA- and CTA+, p=0.79).

CONCLUSIONS:

MVD is a common finding in the non-elderly population referred for CTA for evaluation of possible CAD but without obstructive stenosis. Neither the presence of noncritical atherosclerotic disease nor abnormal FMD increase the likelihood for detecting MVD in this population.

Keywords: CT coronary angiography, Microvascular dysfunction, Myocardial contrast echocardiography

Non-invasive cardiovascular imaging is commonly used for the evaluation of suspected coronary artery disease (CAD) in symptomatic but stable patients. Approaches include those that evaluate coronary anatomy or detect ischemia during physiologic or pharmacologic stress. The sensitivity and specificity for echocardiographic detection of CAD by either contractile reserve or myocardial perfusion are both generally between 80 and 90%.1–3 Yet false positive studies occur, the rate of which is influenced by the prevalence of disease in the study population.2,4 Positive stress echocardiography in those without significant coronary stenosis can result from abnormal microvascular function defined as a vasoconstrictor-vasodilator imbalance,5–7 which may be responsible for the similar rate of clinical outcomes as in those with CAD.4 Anatomic imaging with computed tomography coronary angiography (CTA) can directly image stenosis but is unlikely to detect microvascular dysfunction, even when performed with new fractional flow reserve algorithms that rely on computational fluid dynamics derived from anatomy.

In this study, we hypothesized that patients referred for CTA for suspected CAD, particularly the adult non-elderly who are less likely to have severe obstructive CAD, would have a high prevalence of microvascular dysfunction assessed by vasodilator stress myocardial contrast echocardiography (MCE) perfusion imaging. A secondary hypothesis was that microvascular dysfunction would be more common in those with non-obstructive (<50%) epicardial coronary disease on CTA and at least one high risk feature based on the wide spectrum of pathways that predispose to abnormal vasomotor tone in patients with atherosclerosis or its risk factors,8,9 and the potential for ischemia to occur modest but diffuse arterial narrowing.10 To test our hypotheses, vasodilator stress MCE was performed in subjects <60 years of age who were referred for CTA but had either no evidence of CAD, or had non-obstructive coronary atherosclerotic lesions and at least one established high-risk feature.

METHODS

Study Subjects

The study was approved by the Investigational Review Board at Oregon Health & Sciences University and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02465554). Subjects between the ages of 19 and 60 years of age without known CAD who had been referred for CTA by a health care provider for evaluation of symptoms within 6 months were prospectively screened for eligibility over a two year period. The CTA studies were reviewed by an expert blinded to all other data to ensure eligibility based on CTA results. Patients were recruited to undergo vasodilator MCE microvascular testing if they had either: (i) no evidence for CAD defined as lack of coronary plaque or stenosis on CTA and a coronary artery calcium score (CACS) of 0; or (ii) evidence of coronary plaque in at least one coronary artery but with stenosis severity <50% of luminal diameter, and at least one of the following high risk plaque feature: (a) positive remodeling, (b) low CT attenuation plaque, (c) spotty calcium, and (d) a “napkin ring” sign.11,12 Subjects were excluded for vasculitis, pregnancy, presence of a myocardial bridge, contraindications to regadenoson, or allergy to ultrasound contrast agents. Clinical data including comorbidities, medications, and laboratory values were collected by taking a comprehensive history and through the electronic medical record. Blood for fasting plasma lipid levels was drawn on the day of the study.

Coronary CT Imaging

Coronary CTA images were acquired using prospectively ECG-triggered protocol on a 256-multidector-row scanner (Philips iCT, Cleveland, OH) with the injection of iodinated contrast agent (70 mL of Omnipaque 350 mgI/ml). The imaging parameters included tube current of 150 mAs, tube potential of 120 kVp and gantry rotation of 280 ms. Images were reconstructed with slice thickness of 0.8 mm and increment of 0.4 mm and transferred to the core lab for interpretation. Image analysis was performed by two expert readers in a consensus evaluation using a cardiac workstation (Philips, IntelliSpace Portal 9.0, Cleyeland, OH).

Coronary CTA images were assessed for the presence of coronary stenosis and plaque in all four major epicardial coronary arteries inclusive of the left main according to the guidelines of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography.13 In patients with calcified coronary plaque, we quantified the total amount of coronary calcium using Agatston score on non-contrast CT scan.14 Patients were classified as having high-risk plaque feature if at least one high-risk plaque feature was present, defined as: positive remodeling (remodeling index >1.1 assessed in multiplanar reformatted images reconstructed in long axis and short axis view of the vessel), low CT attenuation plaque (presence of areas of low CT attenuation in non-calcified plaque with mean CT number in three regions of interest <30 HU), napkin-ring sign (a ring-like peripheral higher attenuation of the non-calcified portion of the coronary plaque) and spotty calcium (calcified plaque with a diameter <3 mm in any direction, length of the calcium less than 1.5 times the vessel diameter and width of the calcification <2/3 of the vessel diameter).11,12

Quantitative measurements of coronary plaque volume were performed using semi-automated analysis software QAngio CT Research Edition (v3.1; Medis, Leiden, The Netherlands). Analysis began with the automatic detection of the coronary arteries followed by the segmentation of luminal and outer vessel boundaries. If needed, manual adjustments of the vessel centerline and boundaries were performed. The total coronary plaque volume was measured in all that coronary segments that were determined to have coronary plaque on qualitative assessment.

Microvascular Testing with Myocardial Contrast Echocardiography

Patients abstained from all caffeinated products for 48 hours prior to study. MCE perfusion imaging was performed with a contrast-specific multipulse amplitude modulation imaging algorithm (iE33, Philips Ultrasound, Andover, MA) at a centerline frequency of 2.0 MHz. Imaging was performed at a mechanical index of 0.12–0.14 and gain was set at a level that just eliminated background myocardial speckle. Images were acquired in the apical 4-chamber, 2-chamber, and long-axis imaging planes. Lipid-shelled octafluoropropane microbubbles (Definity, Lantheus Medical Imaging, North Billerica, MA) were diluted to 30 mL total volume in normal saline and infused at a constant rate of 1.0 to 1.5 ml/min. A 5-frame high-power (mechanical index >0.9) sequence was applied to destroy microbubbles in the imaging sector through inertial cavitation, after which electrocardiographically-triggered end-systolic frames were acquired to assess contrast replenishment. MCE was performed at rest and during vasodilator stress. For the latter, images were acquired between 1 and 4 min after intravenous administration of regadenoson (0.4 mg). Microvascular dysfunction was defined by global or segmental lack of complete transmural or subendocardial microvascular refill within 2 seconds during vasodilator stress.15

For quantitative analysis, digital video clips were transferred to a personal computer and analyzed using validated intensity analysis software (iMCE, Narnar LLC, Portland, OR). Data were averaged for the three major coronary vascular territories. A region-of-interest was drawn to derive information transmurally, even when defects seen were only subendocardial. The first post-destructive frame was digitally subtracted from all subsequent frames and background-subtracted time-intensity data were fit to the function:

where y is signal intensity at time t, A is the plateau intensity reflecting relative microvascular blood volume (MBV), and β is the rate constant reflecting microvascular blood flux rate. Microvascular blood flow was quantified by the product of MBV and β.16 Flow reserve and β-reserve were calculated by the ratio of values obtained during regadenoson to those at rest.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography (iE33, Philips Ultrasound, Andover, MA) was performed to assess chamber dimensions and left ventricular function according to guidelines published by the American Society of Echocardiography.17 Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and volumes were calculated using the modified Simpson’s method; while LV mass was calculated using the linear formula. Stroke volume was calculated using the product of left ventricular outflow tract area and the time-velocity integral measured by pulsed-wave spectral Doppler. Myocardial work was calculated by the product of stroke volume index, systolic blood pressure, and heart rate.

Flow Mediated Vasodilation

Brachial artery flow-mediated vasodilation (FMD) was performed using a linear-array probe (5–9 MHz). At baseline, the brachial artery diameter proximal to the antecubital fossa was measured using 2-D ultrasound and real-time spatial compounding of co-planar angled beams. Centerline blood velocities were measured at the same location using pulsed-wave Doppler and angle correction software. A blood pressure cuff was placed around the proximal forearm and insufflated to 50 mm Hg over systolic blood pressure (BP) for 5 minutes. After release of the cuff, Doppler velocity measurements were measured immediately and brachial diameter measurements were repeated at 30 second intervals for four minutes. FMD was calculated by the ratio of maximum hyperemic to baseline diameter. This value was also expressed normalized to hyperemic flow, expressed as the absolute increase in blood velocity.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Prism (version 5.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Group-wise differences were assessed by Mann-Whitney U test for data that were determined to be non-normally distributed by D’Agostino and Pearson omnibus test. For data with normal distribution, group-wise differences were assessed by non-paired Student’s t-test for group-wise comparisons and by paired Student’s t-test for pre- and post-regadenoson data. Differences in proportions were assessed by a Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Correlations were made by least-squares fit and linear regression analysis. Differences were considered significant at p<0.05 (2-sided).

RESULTS

Of the 30 patients recruited, vasodilator stress MCE could be performed in 29. Clinical data are shown in Table 1. At least one traditional CAD risk factor was present in 18 (62%) of the subjects, and 15 (51%) were taking at least one vasoactive antihypertensive medication. On average, plasma lipid values (Table 2) were largely normal, although 4 subjects had elevated LDL cholesterol (14%) and 6 subjects (21%) had elevated lipoprotein(a) at the time of the study. A total of 8 subjects were on a statin. On average, echocardiographic measurements, including measurements of stroke work and myocardial work which influence oxygen demand, were normal (Table 3). For the entire cohort, a total of 21 subjects were classified as having no coronary plaque and 8 as having non-obstructive CAD (<50%) with at least one high risk plaque feature. Coronary plaque was present in one vessel in 4 subjects, two vessels in 2 subjects, three vessels in 1 subject, and four vessels in 1 subject.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics

| Total Cohort (n=29) | −CAD (n=21) | +CAD (n=8) | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 48±6 | 47±6 | 51±6 | ns |

| Male/Female | 10/19 | 6/15 | 4/4 | ns |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.7±6.6 | 28.6±7.0 | 29.1±5.8 | ns |

| Family History, n (%) | 16 (55%) | 10 (48%) | 6 (75%) | ns |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 10 (34%) | 5 (24%) | 5 (63%) | ns |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (13%) | ns |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 7 (24%) | 4 (19%) | 3 (38%) | ns |

| Smoking history (%) | 4 (14%) | 4 (19%) | 0 (0%) | ns |

| Medications, n (%) | ||||

| ACE-I/ARB | 8 (28%) | 6 (29%) | 2 (25%) | ns |

| Beta blocker | 9 (31%) | 5 (24%) | 4 (50%) | ns |

| CCB | 3 (10%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (25%) | ns |

| Anti-platelet | 8 (28%) | 3 (14%) | 5 (63%) | ns |

| Anti-thrombotic | 2 (7%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (13%) | ns |

| Statin | 8 (28%) | 3 (14%) | 5 (63%) | 0.01 |

| Other lipid agent | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (13%) | ns |

| Long-acting nitrates | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ns |

| Insulin | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ns |

ACE-I, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CCB, calcium channel blocker.

p-value for comparison of −CAD and +CAD cohorts.

Table 2.

Plasma Lipid Values Based on Absence or Presence of CAD

| Total Cohort (n=29) | −CAD (n=21) | +CAD (n=8) | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 138±53 | 140±55 | 132±50 | ns |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 190±36 | 199±30 | 168±42 | 0.03 |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 55±15 | 57±15 | 50±13 | ns |

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 108±27 | 114±22 | 92±34 | 0.05 |

| Lipoprotein(a) (mg/dL) | 23±31 | 13±10 | 51±50 | 0.003 |

HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

p-value for comparison of −CAD and +CAD cohorts.

Table 3.

Echocardiography Measurements

| Total Cohort (n=29) | −CAD (n=21) | +CAD (n=8) | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVIDd (cm) | 4.7±0.6 | 4.7±0.6 | 4.6±0.6 | ns |

| LVIDs (cm) | 3.2±0.8 | 3.3±0.8 | 3.0±0.7 | ns |

| IVSd (cm) | 0.9±0.3 | 0.9±0.3 | 1.0±0.2 | ns |

| PWd (cm) | 0.9±0.2 | 0.8±0.1 | 1.0±0.2 | ns |

| LVEDV (mL) | 100±22 | 100±24 | 99±20 | ns |

| LVESV (mL) | 38±12 | 39±11 | 38±14 | ns |

| LVEF (%) | 63±7 | 63±6 | 63±9 | ns |

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 77±25 | 74±24 | 85±28 | ns |

| Stroke volume (mL) | 72±19 | 73±22 | 72±12 | ns |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 5.1±1.5 | 5.1±1.7 | 5.0±1.1 | ns |

| Stroke work (mL×mm Hg) | 8729±1906 | 8581±2001 | 9101±1717 | ns |

| Myocardial work (×1000 mL×mm Hg/min) | 1032±328 | 978±333 | 1170±294 | ns |

IVSd, diastolic interventricular septum thickness; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD, left ventricular end-systolic volume; LVIDd, diastolic left ventricular diameter, LVIDs, systolic left ventricular diameter; PWd, diastolic posterior wall thickness.

p-value for comparison of −CAD and +CAD cohorts.

During regadenoson vasodilator stress, for the entire cohort there was a significant drug-related increase in both heart rate and double product with no change in blood pressure (Table 4). No patients experienced hypotension defined as systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg, thereby excluding the possibility of reduced aortic perfusion pressure as a cause for impaired hyperemic perfusion. No patients had diagnostic ST-segment changes on ECG. During regadenoson MCE, 12 subjects (41%) had evidence of impaired microvascular function, defined as delayed microvascular replenishment of contrast on MCE during vasodilator stress in at least one vascular territory (Figure 1). Seven patients (24%) had severe microvascular dysfunction defined as contrast replenishment that required ≥5 seconds during regadenoson in at least one segment. In these patients, the spatial pattern was divided nearly evenly between those with global versus segmental abnormalities in stress microvascular perfusion. No significant differences in either HR or blood pressure at rest or during stress were found for subjects classified as having normal versus abnormal microvascular function (Table 4). There were no major demographic or risk factor differences between those with normal versus abnormal microvascular function on MCE except there was a non-significant trend for greater proportion of women in abnormal microvascular function group (83% vs 53%, χ2 p=0.09). There were no significant differences in blood lipid values for those with normal versus abnormal microvascular function (Table 5).

Table 4.

Vital Signs at Rest and During Vasodilator Stress*

| HR (min−1) | Systolic BP (mm Hg) | Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | Double Product (mm Hg/min) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire Cohort | ||||

| Rest | 71±12 | 117±15 | 68±11 | 8325±2199 |

| Stress | 84±17† | 118±22 | 71±14 | 9577±3467† |

| −CAD on CTA | ||||

| Rest | 71±14 | 113±15 | 68±11 | 8175±2324 |

| Stress | 86±18† | 117±24 | 71±15 | 9569±3788 |

| +CAD on CTA | ||||

| Rest | 69±8 | 126±14 | 69±10 | 8718±1911 |

| Stress | 78±12 | 121±18 | 74±14 | 9603±2497 |

| Normal microvascular function | ||||

| Rest | 69±11 | 118±15 | 69±10 | 8172±2060 |

| Stress | 86±19† | 117±25 | 73±14 | 10139±3545 |

| Abnormal microvascular function | ||||

| Rest | 73±15 | 114±16 | 66±12 | 8404±2570 |

| Stress | 82±12 | 117±19 | 69±15 | 9593±3353 |

CAD, coronary artery disease; CTA, coronary computed tomography angiography

p=ns for all comparisons between presence vs absence of CAD, and normal vs abnormal microvascular function

p<0.05 versus resting condition.

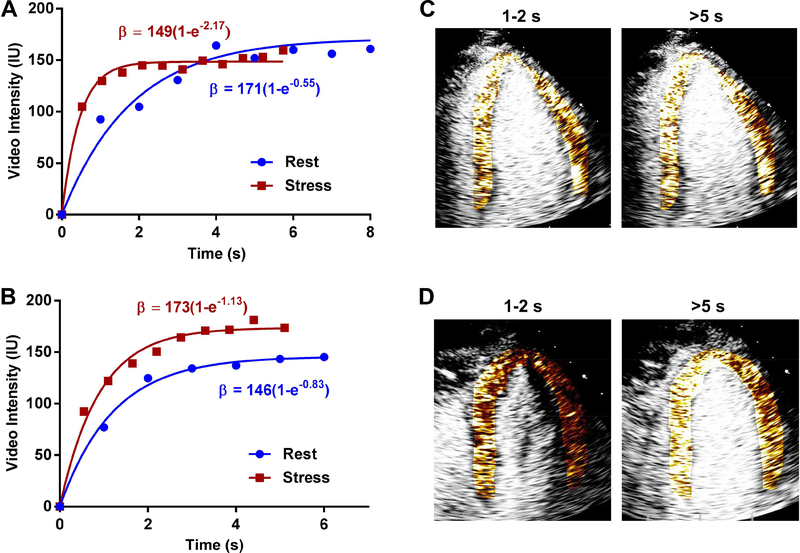

Figure 1.

Examples of time-intensity data from the myocardium at rest and during regadenoson stress from a patient categorized as having (A) normal microvascular function, or (B) abnormal microvascular function. During stress, the subject with normal microvascular function exhibits a plateau of videointensity between 1 and 2 seconds and a nearly 4-fold increase in β-value; whereas the subject with abnormal microvascular function has a plateau of videointensity between 3 and 4 seconds and a small (<40%) increase in β-value. (C and D) The corresponding background-subtracted color coded MCE images from the apical 4-chamber view during stress at 1–2 seconds or >5 seconds after the destructive pulse sequence illustrate the incomplete replenishment by 1–2 seconds in the patient with microvascular dysfunction which was used for semi-quantitative categorization.

Table 5.

Plasma Lipid Values Based on Microvascular Functional Status

| Normal (n=17) | MVD (n=12) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 139±52 | 136±57 | ns |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 183±29 | 201±43 | ns |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 52±14 | 59±15 | ns |

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 103±20 | 114±35 | ns |

| Lipoprotein(a) (mg/dL) | 28±40 | 17±12 | ns |

HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MVD, microvascular dysfunction.

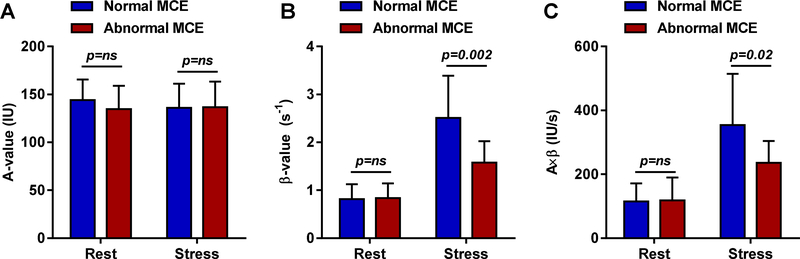

Quantitative analysis of myocardial perfusion on MCE, which for each patient was averaged for at least two vascular territories, showed no differences in resting MBF, MBV or microvascular flux rate (β) between subjects classified as having normal versus abnormal microvascular function (Figure 2). During regadenoson stress, however, subjects with microvascular dysfunction had significantly lower MBF and microvascular flux rate (β), and lower β-reserve (1.95±0.58 vs 3.67±2.96, p=0.01), thereby corroborating subjective classification of these patients.

Figure 2.

Quantitative MCE data (mean ±SD) averaged for at least two vascular terrtories including (A) microvascular blood volume (A-value), (B) microvascular flux rate (β), and (C) microvascular blood flow (A×β) at rest and during regadenoson in patients subjectively determined to have normal microvascular response versus microvascular dysfunction. IU, intensity units; s, seconds.

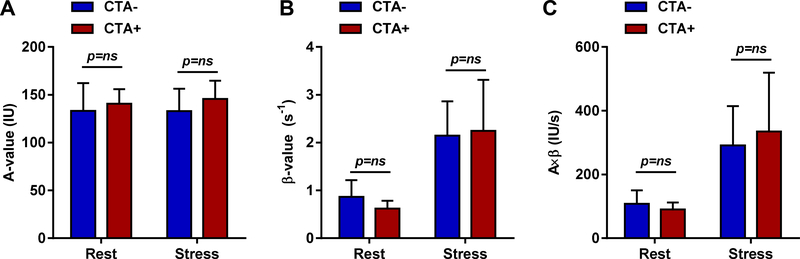

Separate analysis was performed for subjects with and without CAD with the caveat that the power from these studies was limited by the low number of subjects with CAD. In subjects with CAD, the median Agatston score was 41.8 (IQR 10.5 to 84.8). High-risk features included spotty calcium in all 8 subjects, positive remodeling in 3 subjects, low CT attenuation plaque in 2 subjects and napkin ring sign in 2 subjects. The mean total plaque volume in subjects with coronary plaque was 32.5 mm3. The clinical characteristics of the patients stratified according to CTA results (Table 1) did not show any major group-wise differences except those with CAD had a trend toward higher prevalence of a history of dyslipidemia (p=0.08). Plasma lipids (Table 2) revealed that those with non-obstructive CAD had lower total and LDL cholesterol than those without CAD, likely reflecting a greater proportion of subjects treated with statins (63% vs 14%, p<0.01). However those with CAD had significantly higher levels of lipoprotein(a), a known CAD risk factor. Results on resting echocardiography (Table 3) were similar between groups, as were hemodynamic variables at rest or during vasodilator stress (Table 4). When microvascular function was analyzed according to the CTA stratification, there were no group-wise differences in the prevalence of microvascular dysfunction function (43% vs 38% for CTA- and CTA+, Fisher’s exact p=0.79), or by quantitative MCE perfusion during stress (Figure 3). The proportion of patients that had CAD+ on CTA was similar for those with and without microvascular dysfunction (29% vs 38%, χ2 p=0.90). Mean total plaque volume was also similar in subjects with versus without microvascular dysfunction (9.3±20.4 vs 6.6±15.7 mm3, p=0.84).

Figure 3.

Quantitative MCE data (mean ±SD) including (A) microvascular blood volume (A-value), (B) microvascular flux rate (β), and (C) microvascular blood flow (A×β) at rest and during regadenoson in patients subjectively determined to have normal versus abnormal CTA. IU, intensity units; s, seconds.

Brachial FMD was performed in all subjects and was expressed either as absolute value or as FMD normalized to hyperemic flow velocity, the major contributor of shear augmentation after reperfusion. There were no group-wise differences in these FMD values when analyzed based based on the presence versus absence of microvascular function on MCE, or on the presence versus absence of CAD (Figure 4). On continuous analysis, the relationships between MCE-derived perfusion and FMD were weak, with a significant but poor relationship between microvascular flux rate (β) during vasodilator stress and FMD (r2=0.16; standard error of the estimate=0.04). Neither hyperemic blood flow nor β-reserve correlated with FMD.

Figure 4.

(A-D) Brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD) in the patient cohorts segregated based on MCE microvascular response or on results of CTA. FMD data are expressed as a ratio to baseline diameter, or as FMD ratio normalized to the increase in brachial artery velocity during hyperemia in order to control for the increase in arterial shear. (E-G) Correlation between brachial artery FMD and either hyperemic microvascular flux rate (β), hyperemic microvascular blood flow (Aβ), or β-reserve. IU, intensity units; s, seconds.

DISCUSSION

It is increasingly recognized that abnormal microvascular function without significant obstructive CAD can be responsible for chest pain and for ischemia detected on cardiovascular stress testing. The importance of this phenomenon is underscored by studies that have suggested that patients with microvascular dysfunction or those with “false positive” stress echocardiography have cardiovascular outcome rates that are similar to those of patients with CAD.4,9,18 While there is no consensus for the best technique for diagnosing microvascular dysfunction, approaches that have been used include evaluation of coronary diameter and flow velocity during intracoronary administration of various endothelial-dependent or independent vasodilators in the catheterization laboratory, or non-invasive assessment of global or regional microvascular perfusion during vasodilator stress using MCE or positron emission tomography.

For non-invasive perfusion imaging, methods that are able to quantify myocardial blood flow are desirable for several reasons. A reduction in flow reserve, which is often used to define coronary microvascular dysfunction, can occur solely from an increase in resting blood flow that occurs in the setting of anemia or any condition that increases resting myocardial oxygen demand such as increased heart rate, contractility, or wall stress.5 MCE studies in women with “Syndrome X” have suggested that abnormal flow reserve solely from increased resting flow can occur without any increase in oxygen demand.19 This finding suggests an insufficiency of oxygen or nutrient delivery could exist. Abnormal flow reserve can also occur when vascular resistance does not fall appropriately in response to vasodilatory stimuli.5,8 From a physiology perspective, this would result in a shallower slope to the relationship between coronary perfusion pressure and microvascular blood flow during vasodilator stimulus. While this phenomenon is often attributed to abnormal vasodilator-vasoconstrictor balance, it can also occur from extrinsic microvascular forces when intramyocardial pressures are elevated, such as in high pre-load states.5 While the diagnosis of coronary microvascular dysfunction is conventionally made in the absence of significant (>50%) coronary stenosis, mild but diffuse atherosclerotic narrowing has the potential to reduce flow reserve purely from an anatomic basis.10

Within this framework, in the current study quantitative MCE perfusion imaging during vasodilator challenge was performed to determine the prevalence of microvascular dysfunction in non-elderly subjects referred for CTA who did not have significant obstructive disease or myocardial bridging. The vast majority of these subjects were classified based on Diamond-Forrester classification as having medium pretest likelihood for disease. We found that 41% subjects had evidence for microvascular impairment. The primary definition of microvascular dysfunction was made on the basis of abnormal hyperemic flow rather than abnormal flow reserve in order to eliminate those with abnormal flow reserve solely due to increased resting flow. Quantitative MCE and conventional echocardiography were useful for proving that there was no difference between those with normal versus abnormal microvascular function with regards to either resting blood flow or indices of myocardial work. Quantitative MCE was also useful for confirming a reduction in microvascular flux rate (β) during vasodilator challenge in those defined as having microvascular dysfunction. This finding aligns with the notion that impaired vasodilatory capacity will increase arteriolar resistance and, hence, reduce pre-capillary driving pressure and microvascular flux rate.20

A recent study of patients with angina but no obstructive CAD found endothelial dysfunction or increased coronary resistance during vasodilator testing in the catheterization laboratory in about half, a prevalence similar to our own results.21 Some of these patients had myocardial bridges identified, and all had some degree of atherosclerosis on intravascular ultrasound. Other studies have demonstrated that traditional atherosclerotic risk factors are associated with abnormal flow reserve on positron emission tomography. There are many potential pathways by which atherosclerotic disease itself and associated hyperlipidemia or diabetes mellitus can impair microvascular responses. Some of the better-characterized processes include increased vascular production of reactive oxygen species, reduced endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity, eNOS uncoupling, impaired purinergic receptor response, and increased production of and sensitivity to vasoconstrictors.22 Accordingly we investigated whether microvascular dysfunction in our population was more prevalent in those with evidence of atherosclerosis on CTA. Unexpectedly, microvascular dysfunction was seen to the same extent in those with completely normal coronary arteries versus those with mild non-obstructive disease and at least one high risk plaque feature on CTA, although these results must be tempered by the small number of subjects with CAD. These findings are in agreement with a study of subjects with atherosclerosis on CTA in whom PET perfusion imaging with vasodilator stress did not show any differences in hyperemic myocardial blood flow in segments subtended by arteries with 0–50% stenosis versus arteries with no plaque.23 In another study, coronary flow reserve by transthoracic Doppler was associated with certain atherosclerotic risk factors, yet statistical modeling revealed that they impacted flow reserve to only a minor degree.24 In our study, there were no differences in lipid values based on microvascular functional status.

Our results show a rather poor association between vasodilator MCE measurements of hyperemic myocardial perfusion and FMD. This finding, however, may not be entirely unexpected since previous studies have clearly demonstrated that coronary and brachial reactivity are not tightly correlated.25 The implications of our findings are that FMD may not be an appropriate method for identifying subjects who have symptoms from impaired coronary microvascular function.

There are important limitations to the current study that deserve comment. With prospective screening, the number of patients studied was small based on regional trends of low CTA utilization as a consequence of burdensome pre-authorization policies, and willingness to participate in the study by only half of those that met eligibility. In order to evaluate whether significant atherosclerotic disease predisposes to abnormal microvascular function, we elected to study those who had evidence of atherosclerosis only if they also had at least one high risk plaque feature on CTA. These criteria eliminated some subjects with non-severe CAD but without high risk features. MCE microvascular testing was performed with regadenoson rather than with other vasodilator agents that are purely endothelial-dependent such as acetylcholine. We selected regadenoson based on the notion that vascular response to an adenosine A2a-receptor agonist still requires the additional shear-mediated endothelial responses for full effect.26 Similar to PET perfusion imaging which has been used to assess microvascular function, MCE was not validated against a gold standard for microvascular dysfunction in patients. However, a close correlation is known to exist between these two techniques with respect to quantifying hyperemic response.27 Finally, although the increase in heart rate and double product during regadenoson in the “abnormal microvascular function” group did not meet statistical significance, this is unlikely to be the reason for reduced hyperemic flow since flow augmentation (normally several-fold) occurs primarily from direct coronary arteriolar adenosine A2a-receptor effects rather than from the very modest increases in myocardial work.

In summary, our data indicate that microvascular dysfunction is not an uncommon finding in the non-elderly population referred for CTA evaluation of possible CAD in whom “significant” coronary stenosis is not found. Although the population of patients with evidence of atherosclerotic disease on CTA was small, the presence of atherosclerosis even with additional high risk features did not increase the likelihood of abnormal microvascular response. Our results indicate that vasodilator MCE testing and measurement of peak hyperemic microvascular flux rate or replenishment time can provide a rapid non-invasive method for not only explaining ischemic symptoms in patients who do not have significant disease on angiography, but also for identifying those patients in whom prognosis is affected by abnormal microvascular function.18 This information may have a clinical impact by identifying those who may benefit from therapies that have been shown to reduce symptoms in microvascular dysfunction, or who should avoid medications or dietary supplements that adversely increase vasomotor tone.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by a grant (14–14NSBRI1–0025) to Dr. Lindner from the National Space Biomedical Research Institute of NASA. Dr. Lindner is supported by grants R01-HL078610, R01-HL120046, and P51-OD011092 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Ferencik is supported by grant 13FTF16450001 from the American Heart Association. The study was also supported by material support grants from Astellas.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CACS

coronary artery calcium score

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CTA

computed tomography angiography

- FMD

flow mediated vasodilation

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- MCE

myocardial contrast echocardiography

- PET

positron emission tomography

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

There are no financial disclosures related to this study. All authors have participated in conception of the study design, data acquisition, and data analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Jong MC, Genders TS, van Geuns RJ, Moelker A, Hunink MG. Diagnostic performance of stress myocardial perfusion imaging for coronary artery disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European radiology. 2012;22:1881–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pellikka PA, Nagueh SF, Elhendy AA, Kuehl CA, Sawada SG, American Society of E. American society of echocardiography recommendations for performance, interpretation, and application of stress echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2007;20:1021–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porter TR, Xie F. Myocardial perfusion imaging with contrast ultrasound. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:176–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.From AM, Kane G, Bruce C, Pellikka PA, Scott C, McCully RB. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with abnormal stress echocardiograms and angiographically mild coronary artery disease (<50% stenoses) or normal coronary arteries. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:207–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duncker DJ, Koller A, Merkus D, Canty JM Jr. Regulation of coronary blood flow in health and ischemic heart disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;57:409–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanza GA, Crea F. Primary coronary microvascular dysfunction: Clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and management. Circulation. 2010;121:2317–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camici PG, d’Amati G, Rimoldi O. Coronary microvascular dysfunction: Mechanisms and functional assessment. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12:48–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crea F, Camici PG, Bairey Merz CN. Coronary microvascular dysfunction: An update. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1101–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murthy VL, Naya M, Taqueti VR, Foster CR, Gaber M, Hainer J, et al. Effects of sex on coronary microvascular dysfunction and cardiac outcomes. Circulation. 2014;129:2518–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel MB, Bui LP, Kirkeeide RL, Gould KL. Imaging microvascular dysfunction and mechanisms for female-male differences in cad. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:465–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puchner SB, Liu T, Mayrhofer T, Truong QA, Lee H, Fleg JL, et al. High-risk plaque detected on coronary ct angiography predicts acute coronary syndromes independent of significant stenosis in acute chest pain: Results from the romicat-ii trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:684–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferencik M, Mayrhofer T, Bittner DO, Emami H, Puchner SB, Lu MT, et al. Use of high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaque detection for risk stratification of patients with stable chest pain: A secondary analysis of the promise randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:144–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leipsic J, Abbara S, Achenbach S, Cury R, Earls JP, Mancini GJ, et al. Scct guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of coronary ct angiography: A report of the society of cardiovascular computed tomography guidelines committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2014;8:342–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M Jr., Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu J, Barton D, Xie F, O’Leary E, Steuter J, Pavlides G, et al. Comparison of fractional flow reserve assessment with demand stress myocardial contrast echocardiography in angiographically intermediate coronary stenoses. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei K, Jayaweera AR, Firoozan S, Linka A, Skyba DM, Kaul S. Quantification of myocardial blood flow with ultrasound-induced destruction of microbubbles administered as a constant venous infusion. Circulation. 1998;97:473–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: An update from the american society of echocardiography and the european association of cardiovascular imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1–39 e14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pepine CJ, Anderson RD, Sharaf BL, Reis SE, Smith KM, Handberg EM, et al. Coronary microvascular reactivity to adenosine predicts adverse outcome in women evaluated for suspected ischemia results from the national heart, lung and blood institute wise (women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2825–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rinkevich D, Belcik T, Gupta NC, Cannard E, Alkayed NJ, Kaul S. Coronary autoregulation is abnormal in syndrome x: Insights using myocardial contrast echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26:290–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaul S, Jayaweera AR. Myocardial capillaries and coronary flow reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1399–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee BK, Lim HS, Fearon WF, Yong AS, Yamada R, Tanaka S, et al. Invasive evaluation of patients with angina in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2015;131:1054–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Durand MJ, Gutterman DD. Diversity in mechanisms of endothelium-dependent vasodilation in health and disease. Microcirculation. 2013;20:239–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Driessen RS, Stuijfzand WJ, Raijmakers PG, Danad I, Min JK, Leipsic JA, et al. Effect of plaque burden and morphology on myocardial blood flow and fractional flow reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:499–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mygind ND, Michelsen MM, Pena A, Frestad D, Dose N, Aziz A, et al. Coronary microvascular function and cardiovascular risk factors in women with angina pectoris and no obstructive coronary artery disease: The ipower study. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2016;5:e003064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teragawa H, Ueda K, Matsuda K, Kimura M, Higashi Y, Oshima T, et al. Relationship between endothelial function in the coronary and brachial arteries. Clinical cardiology. 2005;28:460–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao JC, Kuo L. Interaction between adenosine and flow-induced dilation in coronary microvascular network. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H1571–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogel R, Indermuhle A, Reinhardt J, Meier P, Siegrist PT, Namdar M, et al. The quantification of absolute myocardial perfusion in humans by contrast echocardiography: Algorithm and validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:754–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]