Abstract

Prader–Willi syndrome (PWS) is a complex and multisystem neurobehavioral disorder. The molecular mechanism of PWS is deficiency of paternally expressed genes from the chromosome 15q11-q13. Due to imprinted gene regulation, the same genes in the maternal chromosome 15q11-q13 are structurally intact but transcriptionally repressed by an epigenetic mechanism. The unique molecular defect underlying PWS renders an exciting opportunity to explore epigenetic-based therapy to reactivate the expression of repressed PWS genes from the maternal chromosome. Inactivation of H3K9m3 methyltransferase SETDB1 and zinc finger protein ZNF274 results in reactivation of SNRPN and SNORD116 cluster from the maternal chromosomes in PWS patient iPSCs and iPSC-derived neurons, respectively. High content screening of small molecule libraries using cells derived from transgenic mice carrying the SNRPN-GFP fusion protein has discovered that inhibitors of EHMT2/G9a, a histone 3 lysine 9 methyltransferase, are capable of reactivating expression of paternally expressed SNRPN and SNORD116 from the maternal chromosome, both in cultured PWS patient-derived fibroblasts and in PWS mouse models. Treatment with an EMHT2/G9a inhibitor also rescues perinatal lethality and failure to thrive phenotypes in a PWS mouse model. These findings present the first evidence to support a proof-of-principle for epigenetic-based therapy for the PWS in humans.

INTRODUCTION

Prader—Willi syndrome (PWS) is a complex and multisystem neurobehavioral disorder, first described by Prader et al in 1956 based on its characteristic clinical features. These clinical features have since been well-delineated through natural history studies.1-3 The exact incidence of PWS remains unknown, but is estimated to be around 1 in 15,000—20,000 live births.1

Most PWS cases are sporadic, but a small number of familial cases have been reported. In the 1980s, high-resolution chromosome analysis led to the discovery that PWS patients have a chromosomal deletion of 15q11-q13.4,5 This same deletion is also implicated in Angelman syndrome (AS), a severe neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by profound intellectual disability and epilepsy.6 PWS and AS have since become prototypes for genomic imprinting disorders in humans.7,8 In both disorders, the deletion is associated with a different parental origin.9,10 The PWS deletion is of paternal origin, while in AS the same deletion is of maternal origin. Studies of PWS patients over the past 3 decades, and in particular, of rare cases with atypical etiologies, have exponentially expanded our understanding of the disorder on a molecular level.11 A large number of studies investigating genomic imprinting mechanisms in mammals target the 15q11-q13 chromosomal region in humans and its homologous region in the mouse central chromosome, 7C.7,8 Despite substantial progress, the exact molecular pathogenesis of PWS has not been elucidated completely. This knowledge gap has limited the development of treatments that target its underlying genetic defects. Here, we review the major advances in the molecular study of PWS and discuss current and future perspectives on the development of epigenetic-based molecular therapies.

THE NATURAL HISTORY OF PWS

The major clinical manifestations of PWS are specific to the developmental stage of the patient (Table I).1,12,13 Clinical presentations likely begin in the prenatal stage, but there are few documented reports of abnormal findings during this period.13 In newborns, hypotonia and feeding difficulties are immediately noticeable, but gradually improve over the first 2 years of life. In most cases, interventions such as feeding assistance are necessary to maintain normal growth. There is a short period in middle infancy (2—4 years of age) in which feeding and growth appear relatively normal.14 During later infancy or early childhood, excessive feeding, or hyperphagia, becomes a significant problem. In most cases, this will develop into morbid obesity without clinical intervention.3,15,16 Motor milestones and language development are typically delayed, but usually only to a mild or moderate degree.2,17 Mild to moderate cognitive impairment is also common.18 Behavioral problems with obsessive-compulsive characteristics are frequently observed,2,19 and these individuals have a high risk of developing psychosis as adults.20 Hypogonadism is present in both males and females, and manifests as genital hypoplasia, incomplete pubertal development, and infertility. Short stature is common and often presents with facial features characteristic of PWS, small hands and feet, strabismus, and scoliosis.1

Table I.

Clinical problems at different ages

| Birth to age 2 years |

|---|

|

Modified from Driscoll et al.12

Molecular bases of PWS.

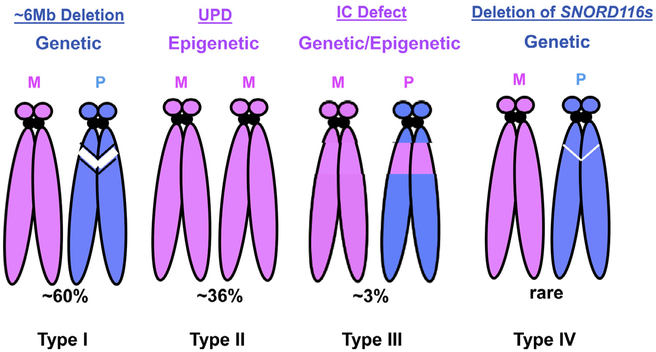

Historically, PWS is considered as a contiguous chromosomal microdeletion syndrome and a prototype for “genomic disorder.”21 In 1980, Ledbetter et al first reported chromosome 15q11-q13 deletion in patients with PWS using the then newly developed high-resolution chromosome banding technique.5 In 1989, Nicholls et al identified maternal uniparental disomy (UPD) 15. This discovery provided the first evidence of genomic imprinting in humans, and indicated that the molecular progression of PWS is impacted by the parent of origin, which was termed the “parental origin effect.”10 The majority of PWS patients have a large deletion (~6 Mb) of the paternal chromosome 15q11-q13. A significant subset of cases have maternal UPD 15. In rare cases of PWS, there is a separate class of imprinting defect in which there are no large chromosomal deletions or maternal UPD 15; instead, the maternal epigenotype is characterized by DNA methylation (5mC) at the 5' CpG island of the SNRPN gene in the 15q11-q13 region.22 The small deletions upstream of the SNPRN gene within the 15q11-q13 identified in rare PWS patients delineate a critical regulatory element designated as imprinting center (IC).23,24 In a recent report, Butler et al summarizes the genetic findings from 510 individuals with PWS (Fig 1).25 Of these, 60% have a ~6 Mb 15q11-q13 deletion in the paternal chromosome; 36% have a maternal UPD 15; and 4% have imprinting defects. The report found that 60% of cases have paternal deletions, which is lower than the historically reported ~70% of PWS cases,12 and suggesting that the latter may be an overestimate due to the smaller sample size. Among the 303 cases with deletions, 38.9% have a 15q11-q13 type I deletion (deletion between breakpoint I and III, Fig 2), 165 (54.5%) have a 15q11-q13 type II deletion (deletion between breakpoints II and III), and 6.6% have a larger (>6 Mb) or in rare cases with a smaller (<1 Mb) atypical 15q11-q13 deletion. For the 185 cases with maternal UPD 15, 29.8% have maternal heterodisomy 15, 57.7% have segmental isodisomy 15, and 12.5% had total isodisomy 15. The average size of segmental isodisomy 15 was about 25.1 Mb with a range of 5—67.4 Mb, commonly in the 15q11-q13 and 15q26 regions.

Fig 1.

Molecular bases of PWS. Four types of molecular defects found in PWS are diagramed. Chromosome ideogram in pink color represents the maternal origin and in blue color for paternal chromosome. The white strips represent the large or small deletion in the chromosome 15q11-q13. (M, maternal; P, paternal; IC, imprinting center; UPD, uniparental disomy). Type I: Large 6 Mb deletion in the paternal chromosome 15q11-q13. Typ1 II: Maternal UPD of 15. Type III: Imprinting defect that with or without a microdeletion in the PWS—IC. The IC defect causes the maternal epigenotype in the 15q11-q13 region in the paternal chromosome measured by DNA methylation. Type IV: Microdeletion in the region of SNORD116s. For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

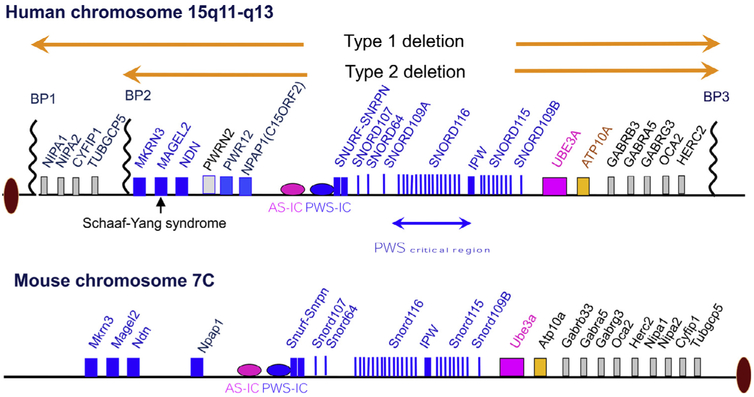

Fig 2.

Human chromosome 15q11-q13 imprinting domain and homologous region in the mouse central chromosome 7C. The genes in blue color are expressed exclusively from the paternal chromosome. The gene in pink color is expressed exclusively from the maternal chromosome. The genes in black color are expressed from both maternal and paternal chromosomes. The imprinted expression pattern for PWRN1, NPAP1, and UBE3A is tissue or cell type specific (BP, breakpoint; IC, imprinting center). For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Genotype and phenotype correlations for PWS.

There is no phenotypic feature that is known to correlate exclusively with any 1 of the 3 main molecular mechanisms (paternal deletion, maternal UPD 15, and imprinting defect) that result in PWS.12 However, the differences in the frequency or severity of certain features are reported among different genotypes, primarily between the large paternal deletion and maternal UPD 15 for which a large number of cases are available for study. The molecular characteristics of different classes may predict that the individuals with imprinting mutation are more similar to the group with the maternal UPD 15. Individuals with a paternal deletion show more prominent feeding problem sleep disturbance, and speech articulation impairment.26 However, the difference between type 1 and type 2 deletion appears not major and also inconsistent among different studies.2,19,27,28 Individuals with maternal UPD 15 have a slightly higher verbal IQ and milder behavior problems19,29 but are more likely to have psychosis in adult30,31 and autism spectrum disorder.32,33 In one study, as many as 62% of individuals with maternal UPD 15 develop atypical psychosis compared with 16% of those with a paternal deletion.34 These observations provide initial clues for further investigation in a larger cohort and with a better phenotyping tool are warranted.

The imprinted domain, IC, and paternally expressed genes.

Discovery of the paternal origin effect in PWS indicates that the candidate gene or genes causing the disorder must undergo genomic imprinting that is either exclusively or preferentially expressed in the paternal chromosome.8,35 Indeed, over a dozen genes have been identified that are exclusively expressed in the paternal chromosome ubiquitously or in tissue specific manner within a ~3 MB interval from the breakpoint 1 (BP1) or breakpoint 2 (BP2) to UBE3A (Fig 2). Several genes known to be bi-allelic based on tissue sample analyses are also mapped in this interval. A bipartite IC that regulates in cis imprint resetting and imprint maintenance in the entire 15q11-q13 imprinted domain is mapped to upstream of SNRUF/SNRPN gene.23,24 All reported IC deletions include promoter/exon 1 of a paternally expressed SNRUF/SNRPN gene and overlap a well-defined CpG island in this region. The smallest IC deletion identified from a patient is ~4 kb and spans the promoter/exon 1 of the SNRPN gene.11,36 How the IC regulates the expression of imprinted genes across the domain has not been fully elucidated.11,37-39 The PWS—IC is differentially regulated by several epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation, histone methylation, and acetylation.23,40,41 Differential DNA methylation (5mC) is the best-recognized modification for the reference of parental identity.23 In the literature, the CpG island of SNPRN within the PWS—IC region is the most reported region for DNA methylation. The PWS—IC is unmethylated on the paternal chromosome but methylated on the maternal chromosome by 5mC. DNA methyltransferases (DNMT1 and DNMT3A/B) play a role in both the establishment and maintenance of DNA methylation.39,42,43 Deficiency of DNMTs in mouse models results either embryonic or early postnatal lethality.44,45 Deficiency of Dnmt1 in mice leads to loss of the methylation in PWS—IC and the bi-allelic expression of paternally expressed Snrpn.45 The paternal genome undergoes active demethylation, in part through action of TET3, a ten-eleven translocation gene family member, which converts 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine.46 The maternal genome undergoes passive demethylation through multiple cell divisions. Differential DNA methylation that is placed on the PWS—IC in the germline is maintained following fertilization, despite the extensive reprogramming that occurs as the genomes are prepared for embryonic development. Interestingly, a recent genome wide high-resolution methylome analysis has revealed a more complex parent-of-origin specific differential methylated regions (DMRs) in the 15q11-13 PWS/AS imprinting domain.47 In contrast to the pattern in PWS—IC, the entire region of 15q11-q13 displays an almost continuous preferential paternal methylation but interposed “spikes” of maternal methylation. The maternally methylated DMRs are mostly located at regulatory features (promoters, promoter flanks, and transcription start sites), whereas the paternally methylated DMRs are more evenly spread with repeats and heterochromatin in the region. The relevance of this pattern of DMRs to the imprinted expression of genes in the region remains unclear and is warranted for further investigation.

The critical region and candidate genes for PWS.

More than a dozen of paternally expressed coding genes, SnoRNA clusters, and long noncoding RNA transcripts have been identified from the PWS candidate region (Fig 2). Conceptually, all of them are candidate for PWS because the expression of these genes is absent in PWS patients with a large deletion, maternal UPD, and IC defect. MKRN3, NDN, MAGEL2, NPAPA1, and SNURF-SNRPN are 5 protein coding genes. The specific functions for each gene and their relevance to the PWS phenotypes remain obscure. Mutant mice for NDN, MAGEL2, and SNURF-SNRPN genes have been generated and characterized (see more discussion in section of PWS models below). MKRN3 is believed to play an important role in regulating the hormonal axis related to the puberty development in human because loss of function mutations in MKRN3 is found in several families with an idiopathic precocious puberty.48 There are 6 clusters of SnoRNA including SNORD64, SNORD107, SNORD109A/B, SNORD116, and SNORD115 in the region between SNRPNR and UBE3A. They belong to the class of C/D box SnoRNAs.49 SNORD115 is implicated in the RNA editing of 5HTR2C receptor but function for other SnoRNA clusters remain poorly understood.50,51 Similarly, little is known for the function of the majority long noncoding RNA transcripts in the region. Some of them are known to serve as the host transcripts for SnoRNA clusters. Two newly characterized SPA1 and SPA2 transcript, a long noncoding RNA that is 5' SnoRNA capped and 3' polyadenylated are implicated in the RNA protein binding and alternative splicing of mRNA.52-54

Over the last decade, the application of new genomic technologies for molecular diagnostics, such as high-resolution copy number variant analyses by array Comparative Genomic Hybridization and whole exome sequencing, has revealed rare and subtle genetic defects in the chromosome 15q11-q13 in the individuals with a clinical or suspected diagnosis of PWS. In 2008, a case study of a clinically diagnosed PWS patient identified a small ~400 kb microdeletion spanning the SNORD116 cluster55 (Fig 2). The deleted interval also contains the host noncoding RNA transcripts that overlap with IPW transcripts, and a newly characterized SPA1 and SPA2 transcript.52,53 Similar findings are also reported in subsequent cases.56-58 The smallest microdeletion is restricted to the SNORD116 cluster and its host noncoding RNA transcript, a portion of IPW, and SPA2 transcript based on the genome annotation.56 Molecular findings from these rare cases together indicate that a region between SNRPN and UBE3A, the SNORD116 cluster in particular, may be critical to the key clinical presentations of PWS. However, it does not exclude a possibility that disruption of SPA2 and IPW as well as the host transcript for SNORD116 may also play a role because other studies have suggested that the noncoding RNAs of SPA2 and IPW may have functions in regulating other genes.52,59 Over the past 5 years, whole exome sequencing has been used routinely to evaluate a small number of patients who have clinical features overlapping those of PWS or, in some cases, who were referred for the evaluation of autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. These clinical studies have revealed pathogenic single nucleotide variants in the paternal allele of the MAGEL2 gene.60,61 These cases were later named Schaaf—Yang syndrome62 because of their distinct or otherwise consistent clinical features, such as autism spectrum disorder and joint contractures, which are not typically seen in PWS. Intriguingly, protein truncating mutations of MAGEL2 are also associated with several cases who have a primary diagnosis of either arthrogryposis multiplex congenita or Chitayat—Hall syndrome, and whose features do not significantly overlap with those of PWS or Schaaf—Yang syndrome.63,64 The molecular basis of the pleotropic presentation associated with MAGEL2 mutations is not well understood. PWS patients with paternal deletion, maternal UPD 15, and IC defect do not express MAGEL2, and this deficiency would be expected to contribute to some of their clinical presentations. However, if MAGEL2 mutations actually result in stable truncated proteins, and therefore act as a gain of function or dominate negative mutation mechanism, interpretation of truncating mutations of MAGEL2 would be different. Further investigation is certainly warranted to test various hypotheses related to the role of MAGEL2 in these different clinical presentations.

Current clinical treatments for PWS.

Like most human genetic diseases, there are no clinical targeted molecular therapies for PWS patients. Current management is symptom-based or recreational therapy for medical or behavioral problems.1,65 Special feeding techniques, including specialized nipples or gavage feeding, may be necessary for the first weeks to months of life to assure adequate nutrition and growth, and to prevent failure to thrive. Gastrostomy tube placement is rarely necessary as feeding improves with time, but could be considered if clinically indicated. The hyperphagia is believed to be caused by a hypothalamic abnormality resulting in lack of satiety. However, the exact pathophysiology and molecular mechanism underlying excessive eating or hyperphagia remains unclear. Several studies have suggested the elevated levels of ghrelin, a potent circulating orexigenic hormone, correlate with the onset of hyperphagia in individuals with PWS.66,67 But other studies have not reached the same conclusion.68,69 Interestingly, the prohormone convertase PC1 (encoded by PCSK1) is reduced in PWS patient iPSC and iPSC-derived neurons as well as in the PWS mouse model with deficiency of Snord116.70,71 Because deficiency of PC1 in humans and mice causes the hyperphagic obesity, the result of reduced PC1 may support that the major neuroendocrine features in PWS are the result of PC1 deficiency. No known medications help control excessive eating or suppress food seeking behavior for individuals with PWS. Behavioral modification and food access restriction remain the primary intervention.72 Short stature is common in PWS, and growth hormone treatment is the mainstream therapy for PWS clinical management12,73,74 There have been extensive investigations into whether PWS patients have growth hormone deficiency, although study quality varies widely. In the literature, the reported prevalence of growth hormone deficiency in patients with PWS ranges from 40% to 70%.13 Factors contributing to this significant discrepancy remain unclear, and a varying percentage of subjects show stimulated growth hormone values within the normal range. More importantly, the mechanism underlying growth deficiency associated with the deficiency of paternally expressed genes is completely unknown. Nevertheless, growth hormone has been widely used in clinic to treat PWS.75 The bulk of evidence demonstrates benefit from growth hormone treatment therapy, including improvement in final height, body composition, physical strength, increased lean body mass, decreased fat mass, and increased mobility. Several small-scale studies also report the positive findings in cognitive and behavioral impairments in PWS patients.76,77 However, systemic investigation is necessarily needed to determine whether growth hormone therapy also improves cognitive function and helps in the management of behavioral problems. Recently, multiple clinical trials indicate that intranasal oxytocin treatment may have significant clinical benefits.78-81 The mechanism underlying the clinical efficacy of oxytocin treatment remains to be elucidated.

Mouse models for PWS.

The 15q11-q13 region in humans is highly conserved in the central chromosome 7C region in mice. The structures of the imprinting domain, imprinted expression for most genes, and IC are also conserved in mice.82 The exception to these is that the long noncoding RNAs of SPA1 and SPA2 in human are apparently not conserved in rodent.52 Researchers have produced and characterized a series of genetically modified mouse models with inactivating mutations at different genes or loci within the mouse central chromosome 7 (Table II). Until recently, it has been difficult to evaluate the validity of these models, as precise genotype and phenotype correlations between genetic defects in different genes in the 15q11-q13 regions and the features of PWS in humans remained unclear. It has become evident in recent years that SNORD116 deficiency is critical to the key PWS clinical features. However, other paternally expressed genes may also modify the clinical presentation with a large paternal deletion, maternal UPD, and imprinting defect. For comparison with the majority of human PWS cases, an ideal model for PWS would be genetically mutant mice carrying a chromosome deletion that is homologous with either a type 1 or type II deletion in human 15q11-q13 region. To date, there are no reports of such a model. We have attempted to engineer a mouse chromosome with a deletion from Gabrb3 to Ndn and Ube3a to Ndn, but have failed to obtain germline transmission despite successful introducing these deletions into mouse embryonic stem cells (Jiang and Beaudet, unpublished data). A virus-induced transgene insertion in the 7C of the mouse chromosome 7 (TgPWS/del) has been reported and characterized.83 The exact breakpoint and size of the deletion has not been delineated, but is estimated to span the region between Ndn and Ube3a. Unfortunately, this mouse line is no longer available for further characterization.82 Researchers have used a Cre/loxP chromosomal engineering technique to generate and characterize mice carrying a ~500 kb deletion from exon 1 of Snprn to exon 2 of Ube3a, which includes the cluster of Snord116 in the paternal chromosome.84 The paternal deletion results in a highly penetrant perinatal lethality and poor feeding, which is considered to recapitulate human neonatal and early infant PWS phenotypes. Smaller deletions restricted to Snord116 are also reported.85,86 Mouse phenotypes of the Snord116 paternal deletion are similar to, but milder than, those of mice with a paternal deletion from Snrpn to Ube3a. Mutations in the individual, paternally expressed genes Snrpn, Ndn, and Magel2 are also reported. No significant phenotypes have been associated with paternal deficiency of Snprn.84 In Ndn mutant mice, perinatal lethality has been associated with 1 line87 but not another.88 Extensive phenotypic analyses have been conducted for 2 different lines of paternal Magel2 deficient mice.89,90 Both prenatal and postnatal partial lethality have been reported in these lines. Multiple lines of mutant mice with small deletions in the region homologous to that in human PWS—IC have also been generated and characterized.91-93 Similar to other lines of mutant mice with deletion in paternally expressed genes, partial perinatal lethality is a common feature associated with these IC mutant lines. Discussion of the detail phenotypes for each mutant mouse line is beyond the scope of this review, and readers are referred to updates in the literature and recommendations of the PWS Animal Models Working Group.82 One of the most intriguing findings from a review of all PWS-related models is that none of mutations in germline recapitulate obesity phenotype despite some models may display some degree of hyperphagia phenotype. Interestingly, Cre-expressing adeno-associated virus was used to generate mice with a conditional deletion of Snord116s in the mediobasal hypothalamus; these animals became hyperphagic between 9 and 10 weeks after injection, and a subset developed marked obesity.94 The underlying cause of this discrepancy between germline and conditional deletions of Snord116 remains unclear and warrants further investigation.

Table II.

PWS mouse models that can be used to test the novel therapy

| Mouse strain | Description | Major phenotypes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| pat-Del (Snrpn-Ube3a) | ~500 kb Deletion from Snrpn to Ube3a | Perinatal lethality/poor feeding Postnatal growth retardation No obesity | 84 |

| pat-Del (Snord116)-Brosius | ~deletion of IPW and Snord116 | Perinatal lethality Postnatal growth retardation No obesity | 85 |

| pat-Del (Snord116)-Francke | ~deletion of Snord116 | Perinatal lethality Postnatal growth retardation Abnormal feeding Lean body composition No obesity | 86 |

| PWS–IC del 35 kb | 35 kb deletion in the region homologous PWS–IC | Perinatal lethality Postnatal growth retardation No obesity | 92 |

| PWS–IC del 6 kb | 6 kb deletion in the region homologous PWS–IC | Perinatal lethality Postnatal growth retardation No obesity | 93 |

| PWS–IC del 4.8 kb | 4.8 kb deletion in the region homologous PWS–IC | Perinatal lethality Postnatal growth retardation No obesity | 91 |

| Magel2-Waverick | deletion of Magel2 | Prenatal lethality Viable postnatally Postnatal growth retardation Abnormal food consumption Increased fat to muscle No obesity | 89 |

| Magel2-Muscatelli | deletion of Magel2 | Postnatal lethality/poor feeding Postnatal growth retardation Abnormal food consumption Increased fat to muscle No obesity | 90 |

Epigenetic therapy for PWS.

Epigenetic therapy refers to the use of drugs or other epigenome-influencing techniques for the treatment of human diseases. Over the last 2 decades, this approach has been investigated for the development of novel cancer treatments.95-98 It is beyond the scope of this review to summarize this progress of cancer epigenetic therapy. Search of Clinicaltrials.Gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) using the combined terms “Cancer” and “Epigenetics” returned a total 207 clinical trials (completed and active), 73 of which are actively recruiting. Epigenetic dysregulations at different levels are wide spread in cancer cells.97,99 These could be primary, such as global or gene-specific hyper- or hypomethylation of DNA, alterations in the histone modifications, or secondary to mutations in genes that encode epigenetic proteins.99 The development of epigenetic cancer therapy are mostly focusing on identifications of small molecules and compounds with the capacity to reverse the epigenetic changes found in cancer cells.97,100 These include targeted therapies for a specific type of epigenetic dysregulation and broad epigenome reprogrammers. While almost all types of epigenetic modifications are drug development target candidates, DNA methylation, and histone acetylation have gained the most attention.101 Broad epigenome reprogrammers such as inhibitors for DNMTs and HDACs have been tested in cancers and several have obtained the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use in humans.102-105 These drugs tend to cause large-scale changes in gene expression, generally reversing cancer-specific expression. A long list of other compounds targeting various histone and chromatin modifications is at different investigational stages.100 Targeted epigenetic therapies are focusing on specific epigenetic changes in a subset of cancer patients based on the knowledge of the disease expression signature. For example, The H3K27 histone N-methyltransferase EZH2 is activated by mutations in lymphomas,106 and use of an EZH2 inhibitor induced selective killing of cell lines carrying such mutations.107 The knowledge gained from these epigenetic cancer therapies will certainly be applicable and contribute to the development of similar drugs for brain disorders.108

As genomic imprinting disorders have unique molecular and epigenetic defects, they offer hopeful opportunities to explore epigenetic therapy in humans. For example, the genes responsible for AS and PWS are expressed from either the maternal or paternal chromosome but are repressed or silenced in the corresponding paternal or maternal chromosome. The genetic structure of AS and PWS genes in the silenced chromosome 15q11-q13 remain intact, but are transcriptionally repressed via an epigenetic mechanism. Thus, the hypothesis for epigenetic therapy in these disorders is straightforward; namely, a pharmacologic approach would utilize epigenetic modification to reactivate expression of the repressed AS and PWS genes. This hypothesis is supported by early studies that treatments of cultured PWS patient-derived cells with DNA methylation inhibitors of 5-Azacytidine and 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine result in the reactivation of the paternally-expressed SNPRN gene on the maternal chromosome.41,109 Similarly, but less consistently, treatment with an HDAC inhibitor has also been shown to reactivate expression of the SNRPN gene in PWS patient cells.41,109 The effects of treatment with DNA methylation inhibitors in vivo has not yet been reported. Nevertheless, these observations support the theory that either DNA methylation or histone modification contributes to PWS gene repression in the maternal chromosome.

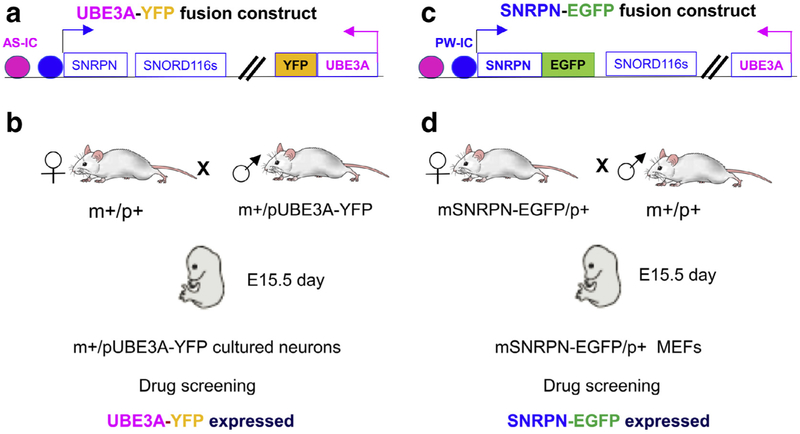

To systematically identify new drugs or small molecules capable of reactivating AS and PWS gene expression, Huang et al conducted a high context small molecule screening in cultured neurons derived from mice carrying a UBE3A-YFP fusion protein transgene110,111 (Fig 3, A and B). Screening of 2306 small molecule compounds identified a list of both topoisomerase I and II inhibitors capable of reactivating expression of the Ube3a gene on the paternal chromosome, both in cultured neurons and in vivo in mouse brains. One of topoisomerase I inhibitors, topotecan, appears to reactivate Ube3a expression and is FDA approved for use as a chemotherapy drug.112 For this reason, topotecan has been more extensively studied in the AS mouse model.110 Considering the known toxicity of current topoisomerase inhibitors, the prospect of their use in human AS has not been fully investigated but is expected to be low. Recently, new derivative of topoisomerase I inhibitor that are capable of reactivating the expression of Ube3a from the paternal chromosome in cultured neurons have been reported.113 These modified new compound may offer a new opportunity to test them in vivo as well as to assess the toxicity of these compounds.

Fig 3.

Drug screening strategy to discover the small molecule drugs for the epigenetic therapy in the PWS and AS. A, UBE3A-YFP fusion protein transgenic mice. B, Drug screening strategy using cultured neurons derived from UBE3A-YFP fusion protein mice to screen small molecule drug that can reactivate the expression of Ube3a from the paternal chromosome. C, SNRPN-EGFP fusion protein transgenic mice. D, Drug screening strategy using mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from the maternal SNRPN-EGFP mice to screen small molecule drug that can reactivate the expression of Snrpn from the maternal chromosome.

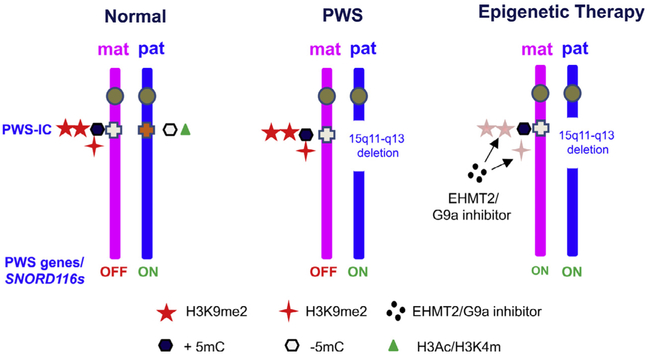

A similar strategy has been applied to investigate SNORD116, the key PWS candidate gene.114 SNORD116 is a noncoding small nucleolar RNA that is processed from the intron of a continuous noncoding RNAs presumably initiated from the promoter of SNRPN.53,115 As Snord116s are noncoding RNAs, it is not feasible to design a direct high content screening approach. Investigators have performed high-content small molecule screening using mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEFs) derived from the maternally inherited Snrpn-EGFP fusion transgene114,116 (Fig 3, C and D). Expression of Snrpn-EGFP in MEFs and the brain was confirmed by mRNA analyses. The working hypothesis is that small molecules that reactivate expression of Snrpn from the maternal chromosome should have the same effect on Snord116s. Screens of more than 9000 small molecules from 13 libraries have identified a list of G9a/EHMT2 inhibitors, primarily UNC0642 and UNC0638, that are capable of reactivating the expression of SNRPN-EGFP in MEFs.114 As hypothesized, both UNC0642 and UNC0638 can reactivate SNORD116 expression in mice in vivo as well as in cultured fibroblasts derived from PWS patients with a paternal deletion of 15q11-q13. Most importantly, treatment with UNC0642 during postnatal days 5—12 has demonstrated the same reactivation of Snrpn and Snord116, which in turn was protective against perinatal lethality and poor feeding in the PWS mouse model carrying a paternal deletion from Snrpn to Ube3a.84,114 The same treatment in wild type mice did not cause any significant acute toxicity at the given dose. The treatment is also effective in adult mice to reactivate the expression of SNRPN-EGFP fusion transgene in brain and liver from the maternal chromosome.114 It remains to be investigated whether the treatment could have the same effect for the human neurons derived from the iPSCs of PWS patients. These results provide the first proof-of-principle for the feasibility of epigenetic therapy in PWS (Fig 4). As expected, treatment with a G9a/EHMT2 inhibitor reduced the H3K9m2/H3K9me3 in PWS—IC and multiple other loci within the imprinted domain. The chromatin accessibility assay also indicates that the treatment of G9a results in a more open chromatin in PWS imprinting domain that supports a chromatin spreading model in response to the change of H3K9me2.114 An interesting question to be investigated is whether the treatment of EHMT2/G9a inhibitor may also alter the expression of paternally expressed PWS genes on the paternal chromosome. One unexpected, but interesting, finding at a mechanistic level is that treatment with G9a/EHMT2 inhibitors did not change DNA methylation in the PWS—IC, yet still reactivated paternally-expressed genes in the maternal chromosome. This suggests that the PWS—IC mechanism that is responsible for imprinted expression of PWS genes operates independently of DNA methylation. It also raises the question as to whether combined DNA methylation inhibitors and histone modulators would have a synergistic effect and raise the efficiency of PWS gene reactivation. In assessing the prospective of clinical application of EHMT2/G9a mediated epigenetic based therapy, it is expected that the EHMT2/G9a inhibitor treatment would be effective for PWS patients caused by all 3 major classes of defects (large paternal deletion, maternal UPD 15, and imprinting defect). However, further validation in different model may be warranted.

Fig 4.

A proof-of-principle of epigenetic therapy for PWS by G9a inhibitors. G9a inhibitor of UNC0638 and UNC0642 (block dots) directly reduce H3K9 methylation (red stars), but do not change methylation of PWS—IC (black hexagon). The reduction of H3K9 methylation is shown to be sufficient to activate the expression of PWS genes from the maternal chromosome, thereby offering therapeutic benefits. For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The impact with a G9a/EHMT2 inhibitor on other paternally expressed genes in the 15q11-q13 region.

As diagramed in Fig 2, NDN, MAGEL2, MKRN3, and SNORD115s are other paternally expressed genes or transcripts that are mapped in the imprinted domain. The interesting and also important question for future translational research is whether EHMT2/G9a inhibitors are also capable of reactivating these genes from the maternal chromosome. Treatment with the G9a/EHMT2 inhibitor can reactivate the expression of host transcript of SNORD115s and NDN in cultured fibroblasts from PWS patients with a paternal deletion of 15q11-q13.114 Reactivation of MAGEL2 has not been determined in cultured fibroblasts because of its brainspecific expression pattern.117 Further investigation into reactivation of Ndn, Mkrn3, and Magel2, and Snord115s by G9a/EHMT2 inhibitors should be performed in vivo including brains of mutant mice carrying the paternal deficiency of these genes. The positive results will not only shed the insight for the mechanism underlying the EHMT2/G9a treatment but also provide the evidence to support translational potential for the individuals carrying mutations only in MAGEL2 and MKRN3 in clinic.

The impact of epigenetic therapy for PWS on the AS Ube3a gene.

There is ample evidence from genetically modified mice studies that antisense RNA of Ube3 (Ube3a-ATS), which also initiates from the IC region of the paternal chromosome, is responsible for brain-specific imprinted expression of AS Ube3a.118,119 This raises the question of whether use of s G9a/EHMT2 inhibitor to reactivate PWS genes in the maternal chromosome would also activate Ube3a-ATS. Treatment with an EHMT2/G9a inhibitor does not affect Ube3a-ATS and UBE3A expression in the mouse brain,114 but does reactivate the expression of host transcripts of SNOR116 and SNORD115. The transcriptional mechanisms underlying the generation of long noncoding host transcripts for SnoRNAs and Ube3a-ATS from the interval between PWS—IC and Ube3a are not well understood. Studies using EHMT2/G9a inhibitors suggest that expression of Snord116 host transcript and Ube3a-ATS are regulated differently. It is possible that these differences arise at the transcriptional start sites for the host transcripts of Snord116 and Ube3a-ATS.54 G9a/EHMT2 inhibitors affect the transcription start site for the host transcripts of Snord116, but not the Ube3a-ATS. Genome-wide H3K9me profiling indicates that the continuous distribution of H3K9me2 along the PWS domain does not extend to the gene body of UBE3A.120 In this case, the effect of the G9a/EHMT2 inhibitor weakens as it becomes more distal to the PWS—IC. This is because a domain-specific chromosome insulator close to UBE3A defines H3K9me2 in the PWS region.120

Other potential targets for epigenetic based therapy.

The PWS—IC and PWS imprinting domain is known to be differentially modified by multiple epigenetic modifications. shRNA-mediated knock down of SETDB1, a methyltransferase responsible for the H3K9m3, in PWS patient-derived iPSCs and iPSC-derived neurons results in partial reactivation of SNORD116 and the host transcripts.121 The change of H3K9me3 is associated to only with SNORD116s locus but not in PWS—IC. The primary change associated the treatment of EHMT2/G9a inhibitors is the reduced H3K9m2 in both SNORD116s and the PWS—IC.114 Reduction of H3K9me3 associated with SNORD116s is also observed in cells treated with EHMT2/G9a inhibitor. In contrast to the G9a/EHMT2 inhibitors, inactivation of SETDB1 reduces DNA methylation in the PWS—IC despite no change of H3K9me3. The SETDB1 interacts with ZNF274, a zinc finger protein.122 In PWS patient iPSCs-derived neurons, inactivation of ZNF274 using a CRISPR/Cas9 method also reduces H3K9m3 in the PWS—IC and reactivates SNRPN and SNORD116 clusters from the paternal chromosome.123 Interestingly, not all SNRPN transcripts were reactivated as a result of ZNF274 inactivation. Similar to G9a inhibitors, but different from the SETDB1 knockdown, ZNF274 deficiency does not affect the DNA methylation of the PWS—IC. These results together suggest that distinct mechanisms may underlie reactivation of paternally expressed genes from the maternal chromosome mediated by EHMT2/G9a and SETDB1/ZNF2714. Nevertheless, these findings together support that SETDB1 and ZNF274 are druggable targets for the development of molecular therapy of PWS.

Genome-wide off-target effects or/and epigenetic toxicity related to epigenetic therapy.

Common concerns regarding the use of epigenetic drugs include the potential for genome-wide or off-target effects that may be referred as epigenetic toxicity. While this is logical in concept, the EHMT2/G9a inhibitor has been well tolerated in animal studies, suggesting that evaluations of epigenetic toxicity should be conducted on a case-by-case basis with careful consideration of the dose, duration, route, and timing of the drug delivery. One example of epigenetic drug safety in practice is the tolerability of an FDA approved DNA methylation inhibitor used in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome patients. 102,124 It is theorized that an epigenetic inhibitor, such as the EHMT2/G9a inhibitor, could generate genome-wide up- or down-regulation of hundreds of genes. Genome-wide mRNA expression profiling of animals treated with different dosing, duration, and at different ages may provide better assessment of toxicity. However, it is difficult to determine whether these changes would reach the threshold of physiological toxicity. It would be even more difficult to predict whether the net impact of up- or down gene regulation is a direct result of the epigenetic drug treatment. In the case of G9a/EHMT inhibitors, genome-wide ChIP analysis for targeted H3K9me2 may help to assess the molecular impact and correlation with change of gene expression. However, the challenge may remain to assess the net impact of physiological interaction among the genes that are dysregulated by epigenetic level in vivo and in long term. To elaborate on this, there is one noteworthy example in humans in which disruption of multiple imprinted loci due to germline mutations in ZFP57 resulted in only a relatively mild condition, a rare case of transient neonatal diabetes.125,126 These observations suggest that evaluating the broad effects of epigenetic drugs is the more complex task at hand and the molecular targeting specifically to SETDB1 or ZNF274 may be an alternative approach to explore in future study.

Concluding remarks and future directions.

PWS is a life-long debilitating genetic and epigenetic condition that has a significant impact on quality of life. The molecular basis underlying PWS is unique and presents a hopeful opportunity to explore epigenetic-based molecular therapy. Broad evidence from PWS patient-derived cellular models and PWS mouse models support the proof of principle that epigenetic modifications to reactivate PWS genes from the maternal chromosome 15q11-q13. Inhibition of H3K9me2 with small molecules derived from high content screening is capable of reactivating SNORD116 expression, a critical gene for PWS, and protects against perinatal lethality and failure of thrive in 1 PWS mouse model. The discovery that inactivation of SETDB1 and ZNF274 that primarily involve H3K9m3 can also reactivate the imprinted expression of PWS genes support the additional epigenetic targets for the future development of PWS therapies. Future investigations need to assess the translational potential of therapy for these approaches in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Conflicts of Interest: The research project is partially supported by Levo Therapeutics through a sponsored research program at Duke University.

We would like to thank Dr. Bryan Roth from UNC-Chapel Hill for the drug screening and Kelly McMillan for critical read and edit for manuscript. The research in Yong-hui Jiang’s lab is supported by grants from FPWR and National Institute of Health to YHI (HD087795 and HD088626). YHJ is also supported in part by Levo Therapeutics.

All authors have read the authorship agreement and agreed. All authors have also read the journal’s policy on disclosure of potential conflicts of interest and the disclosure is described above.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cassidy SB, Driscoll DJ. Prader-Willi syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 2009;17:3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler MG, Bittel DC, Kibiryeva N, Talebizadeh Z, Thompson T. Behavioral differences among subjects with Prader-Willi syndrome and type I or type II deletion and maternal disomy. Pediatrics 2004;113:565–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler MG. Management of obesity in Prader-Willi syndrome. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2006;2:592–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ledbetter DH, Mascarello JT, Riccardi VM, Harper VD, Airhart SD, Strobel RJ. Chromosome 15 abnormalities and the Prader-Willi syndrome: a follow-up report of 40 cases. Am J Hum Genet 1982;34:278–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ledbetter DH, Riccardi VM, Airhart SD, Strobel RJ, Keenan BS, Crawford JD. Deletions of chromosome 15 as a cause of the Prader-Willi syndrome. N Engl J Med 1981;304:325–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magenis RE, Brown MG, Lacy DA, Budden S, LaFranchi S. Is Angelman syndrome an alternate result of del(15)(q11q13)? Am J Med Genet 1987;28:829–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buiting K, Cassidy SB, Driscoll DJ, et al. Clinical utility gene card for: Prader-Willi syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 2014;22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang Y, Tsai TF, Bressler J, Beaudet AL. Imprinting in Angelman and Prader-Willi syndromes. Curr Opin Genet Dev 1998;8:334–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malcolm S, Clayton-Smith J, Nichols M, et al. Uniparental paternal disomy in Angelman’s syndrome. Lancet 1991;337:694–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicholls RD, Knoll JH, Butler MG, Karam S, Lalande M. Genetic imprinting suggested by maternal heterodisomy in nondeletion Prader-Willi syndrome. Nature 1989;342:281–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horsthemke B, Wagstaff J. Mechanisms of imprinting of the Prader-Willi/Angelman region. Am J Med Genet A 2008;146A:2041–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Driscoll DJ, Miller JL, Schwartz S, Cassidy SB, et al. Prader- Willi syndrome In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Stephens K, eds. GeneReviews((R)); 1993Seattle (WA). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butler MG, Lee J, Cox DM, et al. Growth charts for Prader-Willi syndrome during growth hormone treatment. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2016;55:957–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller JL, Lynn CH, Driscoll DC, et al. Nutritional phases in Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2011;155A: 1040–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butler MG, Kimonis V, Dykens E, et al. Prader-Willi syndrome and early-onset morbid obesity NIH rare disease consortium: a review of natural history study. Am J Med Genet A 2018;176:368–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh P, Mahmoud R, Gold JA, et al. Multicentre study of maternal and neonatal outcomes in individuals with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Med Genet 2018;55:594–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cassidy SB, Schwartz S, Miller JL, Driscoll DJ. Prader-Willi syndrome. Genet Med 2012;14:10–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller J, Kranzler J, Liu Y, et al. Neurocognitive findings in Prader-Willi syndrome and early-onset morbid obesity. J Pediatr 2006;149:192–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartley SL, Maclean WE Jr., Butler MG, Zarcone J, Thompson T Maladaptive behaviors and risk factors among the genetic subtypes of Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2005;136:140–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boer H, Holland A, Whittington J, Butler J, Webb T, Clarke D. Psychotic illness in people with Prader-Willi syndrome due to chromosome 15 maternal uniparental disomy. Lancet 2002;359:135–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lupski JR. Genomic disorders: structural features of the genome can lead to DNA rearrangements and human disease traits. Trends Genet 1998;14:417–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohta T, Gray TA, Rogan PK, et al. Imprinting-mutation mechanisms in Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 1999;64:397–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sutcliffe JS, Nakao M, Christian S, et al. Deletions of a differentially methylated CpG island at the SNRPN gene define a putative imprinting control region. Nat Genet 1994;8:52–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buiting K, Saitoh S, Gross S, et al. Inherited microdeletions in the Angelman and Prader-Willi syndromes define an imprinting centre on human chromosome 15. Nat Genet 1995;9:395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butler MG, Hartin SN, Hossain WA, et al. Molecular genetic classification in Prader-Willi syndrome: a multisite cohort study. J Med Genet 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torrado M, Araoz V, Baialardo E, et al. Clinical-etiologic correlation in children with Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS): an interdisciplinary study. Am J Med Genet A 2007;143A:460–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milner KM, Craig EE, Thompson RJ, et al. Prader-Willi syndrome: intellectual abilities and behavioural features by genetic subtype. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2005;46:1089–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varela MC, Kok F, Setian N, Kim CA, Koiffmann CP. Impact of molecular mechanisms, including deletion size, on Prader- Willi syndrome phenotype: study of 75 patients. Clin Genet 2005;67:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dykens EM, Cassidy SB, King BH. Maladaptive behavior differences in Prader Willi syndrome due to paternal deletion versus maternal uniparental disomy. Am J Ment Retard 1999;104:67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holland AJ, Whittington JE, Butler J, Webb T, Boer H, Clarke D. Behavioural phenotypes associated with specific genetic disorders: evidence from a population-based study of people with Prader-Willi syndrome. Psychol Med 2003;33:141–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang L, Zhan GD, Ding JJ, et al. Psychiatric illness and intellectual disability in the Prader-Willi syndrome with different molecular defects—a meta analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e72640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veltman MW, Craig EE, Bolton PF. Autism spectrum disorders in Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes: a systematic review. Psychiatr Genet 2005;15:243–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Veltman MW, Thompson RJ, Roberts SE, Thomas NS, Whittington J, Bolton PF. Prader-Willi syndrome—a study comparing deletion and uniparental disomy cases with reference to autism spectrum disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004;13:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soni S, Whittington J, Holland AJ, et al. The course and outcome of psychiatric illness in people with Prader-Willi syndrome: implications for management and treatment. J Intellect Disabil Res 2007;51:32–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buiting K Prader-Willi syndrome and Angelman syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2010;154C:365–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horsthemke B, Buiting K. Imprinting defects on human chromosome 15. Cytogenet (Genome Res 2006;113:292–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalish JM, Jiang C, Bartolomei MS. Epigenetics and imprinting in human disease. Int J Dev Biol 2014;58:291–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barlow DP, Bartolomei MS. Genomic imprinting in mammals. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2014;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartolomei MS, Ferguson-Smith AC. Mammalian genomic imprinting. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inoue A, Jiang L, Lu F, Suzuki T, Zhang Y. Maternal H3K27me3 controls DNA methylation-independent imprinting. Nature 2017;547:419–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saitoh S, Wada T. Parent-of-origin specific histone acetylation and reactivation of a key imprinted gene locus in Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2000;66:1958–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li E, Beard C, Jaenisch R. Role for DNA methylation in genomic imprinting. Nature 1993;366:362–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li E, Zhang Y. DNA methylation in mammals. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2014;6:a019133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okano M, Bell DW, Haber DA, Li E. DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell 1999;99:247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li E, Bestor TH, Jaenisch R. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell 1992;69:915–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gu TP, Guo F, Yang H, et al. The role of Tet3 DNA dioxygenase in epigenetic reprogramming by oocytes. Nature 2011;477:606–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zink F, Magnusdottir DN, Magnusson OT, et al. Insights into imprinting from parent-of-origin phased methylomes and transcriptomes. Nat Genet 2018;50:1542–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abreu AP, Dauber A, Macedo DB, et al. Central precocious puberty caused by mutations in the imprinted gene MKRN3. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2467–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Falaleeva M, Welden JR, Duncan MJ, Stamm S. C/D-box snoRNAs form methylating and non-methylating ribonucleo-protein complexes: Old dogs show new tricks. Bioessays 2017;39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kishore S, Khanna A, Zhang Z, et al. The snoRNA MBII-52 (SNORD 115) is processed into smaller RNAs and regulates alternative splicing. HumMolGenet 2010;19:1153–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kishore S, Stamm S. The snoRNA HBII-52 regulates alternative splicing of the serotonin receptor 2C. Science 2006;311:230–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu H, Yin QF, Luo Z, et al. Unusual processing generates SPA LncRNAs that sequester multiple RNA binding proteins. Mol Cell 2016;64:534–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Runte M, Huttenhofer A, Gross S, Kiefmann M, Horsthemke B, Buiting K. The IC-SNURF-SNRPN transcript serves as a host for multiple small nucleolar RNA species and as an antisense RNA for UBE3A. Hum Mol Genet 2001;10:2687–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Galiveti CR, Raabe CA, Konthur Z, Rozhdestvensky TS. Differential regulation of non-protein coding RNAs from Prader-Willi Syndrome locus. Sci Rep 2014;4:6445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sahoo T, del Gaudio D, German JR, et al. Prader-Willi phenotype caused by paternal deficiency for the HBII-85 C/D box small nucleolar RNA cluster. Nat Genet 2008;40:719–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bieth E, Eddiry S, Gaston V, et al. Highly restricted deletion of the SNORD116 region is implicated in Prader-Willi syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 2015;23:252–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duker AL, Ballif BC, Bawle EV, et al. Paternally inherited microdeletion at 15q11.2 confirms a significant role for the SNORD116 C/D box snoRNA cluster in Prader-Willi syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 2010;18:1196–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Smith AJ, Purmann C, Walters RG, et al. A deletion of the HBII-85 class of small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) is associated with hyperphagia, obesity and hypogonadism. Hum Mol Genet 2009;18:3257–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stelzer Y, Sagi I, Yanuka O, Eiges R, Benvenisty N. The noncoding RNA IPW regulates the imprinted DLK1-DIO3 locus in an induced pluripotent stem cell model of Prader-Willi syndrome. Nat Genet 2014;46:551–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schaaf CP, Gonzalez-Garay ML, Xia F, et al. Truncating mutations of MAGEL2 cause Prader-Willi phenotypes and autism. Nat Genet 2013;45:1405–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fountain MD, Schaaf CP. Prader-Willi syndrome and Schaaf-Yang syndrome: neurodevelopmental diseases intersecting at the MAGEL2 gene. Diseases 2016;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fountain MD, Aten E, Cho MT, et al. The phenotypic spectrum of Schaaf-Yang syndrome: 18 new affected individuals from 14 families. Genet Med 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jobling R, Stavropoulos DJ, Marshall CR, et al. Chitayat-Hall and Schaaf-Yang syndromes: a common aetiology: expanding the phenotype of MAGEL2-related disorders. J Med Genet 2018;55:316–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mejlachowicz D, Nolent F, Maluenda J, et al. Truncating mutations of MAGEL2, a gene within the Prader-Willi locus, are responsible for severe arthrogryposis. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97:616–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cassidy SB, Dykens E, Williams CA. Prader-Willi and Angel- man syndromes: sister imprinted disorders. Am J Med Genet 2000;97:136–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haqq AM, Stadler DD, Rosenfeld RG, et al. Circulating ghrelin levels are suppressed by meals and octreotide therapy in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:3573–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cummings DE, Clement K, Purnell JQ, et al. Elevated plasma ghrelin levels in Prader Willi syndrome. Nat Med 2002;8: 643–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kweh FA, Miller JL, Sulsona CR, et al. Hyperghrelinemia in Prader-Willi syndrome begins in early infancy long before the onset of hyperphagia. Am J Med Genet A 2015;167A:69–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Feigerlova E, Diene G, Conte-Auriol F, et al. Hyperghrelinemia precedes obesity in Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:2800–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Burnett LC, LeDuc CA, Sulsona CR, et al. Deficiency in prohormone convertase PC1 impairs prohormone processing in Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clin Invest 2017;127:293–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Polex-Wolf J, Yeo GS, O’Rahilly S. Impaired prohormone processing: a grand unified theory for features of Prader-Willi syndrome? J Clin Invest 2017;127:98–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mackenzie ML, Triador L, Gill JK, et al. Dietary intake in youth with Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2018;176:2309–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tauber M, Diene G, Molinas C. Sequelae of GH treatment in children with PWS. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2016;14: 138–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Deal CL, Tony M, Hoybye C, et al. GrowthHormone Research Society workshop summary: consensus guidelines for recombinant human growth hormone therapy in Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:E1072–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bakker NE, Lindberg A, Heissler J, et al. Growth hormone treatment in children with Prader-Willi syndrome: three years of longitudinal data in prepubertal children and adult height data from the KIGS database. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:1702–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dykens EM, Roof E, Hunt-Hawkins H. Cognitive and adaptive advantages of growth hormone treatment in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2017;58:64–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Donze SH, Damen L, Mahabier EF, Hokken-Koelega ACS. Improved mental and motor development during 3 years of GH treatment in very young children with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dykens EM, Miller J, Angulo M, et al. Intranasal carbetocin reduces hyperphagia in individuals with Prader-Willi syndrome. JCI Insight 2018;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kabasakalian A, Ferretti CJ, Hollander E. Oxytocin and Prader-Willi syndrome. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2018;35:529–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Miller JL, Tamura R, Butler MG, et al. Oxytocin treatment in children with Prader-Willi syndrome: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Am J Med Genet A 2017;173: 1243–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rice LJ, Einfeld SL, Hu N, Carter CS. A review of clinical trials of oxytocin in Prader-Willi syndrome. Curr Opin I5sychiatry 2018;31:123–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Resnick JL, Nicholls RD, Wevrick R. Prader-Willi Syndrome Animal Models Working G. Recommendations for the investigation of animal models of Prader-Willi syndrome. Mamm Genome 2013;24:165–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gabriel JM, Merchant M, Ohta T, et al. A transgene insertion creating a heritable chromosome deletion mouse model of Prader-Willi and angelman syndromes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999;96:9258–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tsai TF, Jiang YH, Bressler J, Armstrong D, Beaudet AL. Paternal deletion from Snrpn to Ube3a in the mouse causes hypotonia, growth retardation and partial lethality and provides evidence for a gene contributing to Prader-Willi syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 1999;8:1357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ding F, Li HH, Zhang S, et al. SnoRNA Snord116 (Pwcr1/MBII-85) deletion causes growth deficiency and hyperphagia in mice. PLoS One 2008;3:e1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Skryabin BV, Gubar LV, Seeger B, et al. Deletion of the MBII-85 snoRNA gene cluster in mice results in postnatal growth retardation. PLoS Genet 2007;3:e235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gerard M, Hernandez L, Wevrick R, Stewart CL. Disruption of the mouse necdin gene results in early post-natal lethality. Nat Genet 1999;23:199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tsai TF, Armstrong D, Beaudet AL. Necdin-deficient mice do not show lethality or the obesity and infertility of Prader-Willi syndrome. Nat Genet 1999;22:15–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bischof JM, Stewart CL, Wevrick R. Inactivation of the mouse Magel2 gene results in growth abnormalities similar to Prader-Willi syndrome. HumMol Genet 2007;16:2713–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mercer RE, Wevrick R. Loss of magel2, a candidate gene for features of Prader-Willi syndrome, impairs reproductive function in mice. PLoS One 2009;4:e4291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bressler J, Tsai TF, Wu MY, et al. The SNRPN promoter is not required for genomic imprinting of the Prader-Willi/Angelman domain in mice. Nat Genet 2001;28:232–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yang T, Adamson TE, Resnick JL, et al. A mouse model for Prader-Willi syndrome imprinting-centre mutations. Nat Genet 1998;19:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dubose AJ, Smith EY, Yang TP, Johnstone KA, Resnick JL. A new deletion refines the boundaries of the murine Prader-Willi syndrome imprinting center. Hum Mol Genet 2011;20:3461–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Khan MJ, Gerasimidis K, Edwards CA, Shaikh MG. Mechanisms of obesity in Prader-Willi syndrome. Pediatr Obes 2018;13:3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jones PA, Issa JP, Baylin S. Targeting the cancer epigenome for therapy. Nat Rev Genet 2016;17:630–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Biswas S, Rao CM. Epigenetic tools (The Writers, The Readers and The Erasers) and their implications in cancer therapy. Eur J Pharmacol 2018;837:8–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pfister SX, Ashworth A. Marked for death: targeting epigenetic changes in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discovery 2017;16:241–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Thomenius MJ, Totman J, Harvey D, et al. Small molecule inhibitors and CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis demonstrate that SMYD2 and SMYD3 activity are dispensable for autonomous cancer cellproliferation. PLoS One 2018;13:e0197372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Biswas S, Rao CM. Epigenetics in cancer: fundamentals and Beyond. Pharmacol Ther 2017;173:118–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ribich S, Harvey D, Copeland RA. Drug discovery and chemical biology of cancer epigenetics. Cell Chem Biol 2017;24: 1120–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ahuja N, Sharma AR, Baylin SB. Epigenetic therapeutics: a new weapon in the war against cancer. Annu Rev Med 2016;67:73–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kaminskas E, Farrell AT, Wang YC, Sridhara R, Pazdur R. FDA drug approval summary: azacitidine (5-azacytidine, Vidaza) for injectable suspension. Oncologist 2005;10: 176–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Muller CI, Ruter B, Koeffler HP, Lubbert M. DNA hyperme-thylation of myeloid cells, a novel therapeutic target in MDS and AML. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2006;7:315–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cappellacci L, Perinelli DR, Maggi F, Grifantini M, Petrelli R. Recent progress in histone deacetylase inhibitors as anticancer agents. Curr Med Chem 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Teknos TN, Grecula J, Agrawal A, et al. A phase 1 trial of Vorinostat in combination with concurrent chemoradiation therapy in the treatment of advanced staged head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Invest New Drugs 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Morin RD, Johnson NA, Severson TM, et al. Somatic mutations altering EZH2 (Tyr641) in follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of germinal-center origin. Nat Genet 2010;42: 181–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.McCabe MT, Ott HM, Ganji G, et al. EZH2 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for lymphoma with EZH2-activating mutations. Nature 2012;492:108–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Szyf M Prospects for the development of epigenetic drugs for CNS conditions. Nat Rev Drug Discovery 2015;14:461–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fulmer-Smentek SB, Francke U. Association of acetylated histones with paternally expressed genes in the Prader-Willi deletion region. Hum Mol Genet 2001;10:645–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Huang HS, Allen JA, Mabb AM, et al. Topoisomerase inhibitors unsilence the dormant allele of Ube3a in neurons. Nature 2012;481:185–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dindot SV, Antalffy BA, Bhattacharjee MB, Beaudet AL. The Angelman syndrome ubiquitin ligase localizes to the synapse and nucleus, and maternal deficiency results in abnormal dendritic spine morphology. Hum Mol Genet 2008;17:111–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Brahmer JR, Ettinger DS. The Role of topotecan in the treatment of small cell lung cancer. Oncologist 1998;3:11–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lee HM, Clark EP, Kuijer MB, Cushman M, Pommier Y, Philpot BD. Characterization and structure-activity relationships of indenoisoquinoline-derived topoisomerase I inhibitors in unsilencing the dormant Ube3a gene associated with Angelman syndrome. Mol Autism 2018;9:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kim Y, Lee HM, Xiong Y, et al. Targeting the histone methyltransferase G9a activates imprinted genes and improves survival of a mouse model of Prader-Willi syndrome. Nat Med 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Cavaille J, Buiting K, Kiefmann M, et al. Identification of brain-specific and imprinted small nucleolar RNA genes exhibiting an unusual genomic organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:14311–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wu MY, Tsai TF, Beaudet AL. Deficiency of Rbbp1/Arid4a and Rbbp1l1/Arid4b alters epigenetic modifications and suppresses an imprinting defect in the PWS/AS domain. Genes Dev 2006;20:2859–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Boccaccio I, Glatt-Deeley H, Watrin F, Roeckel N, Lalande M, Muscatelli F. The human MAGEL2 gene and its mouse homologue are paternally expressed and mapped to the Prader-Willi region. Hum Mol Genet 1999;8:2497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chamberlain SJ, Brannan CI. The Prader-Willi syndrome imprinting center activates the paternally expressed murine Ube3a antisense transcript but represses paternal Ube3a. Genomics 2001;73:316–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Meng L, Person RE, Beaudet AL. Ube3a-ATS is an atypical RNA polymerase II transcript that represses the paternal expression of Ube3a. Hum Mol (Genet 2012;21:3001–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wen B, Wu H, Shinkai Y, Irizarry RA, Feinberg AP. Large histone H3 lysine 9 dimethylated chromatin blocks distinguish differentiated from embryonic stem cells. Nat Genet 2009;41:246–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cruvinel E, Budinetz T, Germain N, Chamberlain S, Lalande M, Martins-Taylor K. Reactivation of maternal SNORD116 cluster via SETDB1 knockdown in Prader-Willi syndrome iPSCs. Hum Mol Genet 2014;23:4674–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Frietze S, O’Geen H, Blahnik KR, Jin VX, Farnham PJ. ZNF274 recruits the histone methyltransferase SETDB1 to the 3′ ends ofZNF genes. PLoS One 2010;5:e15082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Langouet M, Glatt-Deeley HR, Chung MS, et al. Zinc finger protein 274 regulates imprinted expression of transcripts in Prader-Willi syndrome neurons. Hum Mol Genet 2018;27: 505–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Mann BS, Johnson JR, Cohen MH, Justice R, Pazdur R. FDA approval summary: vorinostat for treatment of advanced primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Oncologist 2007;12: 1247–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mackay DJ, Callaway JL, Marks SM, et al. Hypomethylation of multiple imprinted loci in individuals with transient neonatal diabetes is associated with mutations in ZFP57. Nat Genet 2008;40:949–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Caliebe A, Richter J, Ammerpohl O, et al. A familial disorder of altered DNA-methylation. J Med Genet 2014;51:407–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]