Abstract

In social species, relationships may form between mates, parents and their offspring, and/or social peers. Prairie voles and meadow voles both form selective relationships for familiar same-sex peers, but differ in mating system, allowing comparison of the properties of peer and mate relationships. Prairie vole mate bonds are dopamine-dependent, unlike meadow vole peer relationships, indicating potential differences in the mechanisms and motivation supporting these relationships within and/or across species. We review the role of dopamine signaling in affiliative behavior, and assess the role of behavioral reward across relationship types. We compared the reinforcing properties of mate versus peer relationships within a species (prairie voles), and peer relationships across species (meadow and prairie voles). Social reinforcement was assessed using the socially conditioned place preference test. Animals were conditioned using randomly assigned, equally preferred beddings associated with social (CS+) and solitary (CS-) housing. Prairie vole mates, but not prairie or meadow vole peers, conditioned toward the social cue. A second study in peers used counter-conditioning to enhance the capacity to detect low-level conditioning. Time spent on CS+ bedding significantly decreased in meadow voles, and showed a non-significant increase in prairie voles. These data support the conclusion that mate relationships are rewarding for prairie voles. Despite selectivity of preferences for familiar individuals in partner preference tests, peer relationships in both species appear only weakly reinforcing or non-reinforcing. This suggests important differences in the pathways underlying these relationship types, even within species.

Keywords: reward, reinforcement, motivation, voles, conditioned place preference, social behavior, meadow vole, prairie vole, vole, partner preference, same-sex, peer, dopamine

INTRODUCTION

Social relationships are integral to wellbeing, and the perceived nature of these relationships can have direct effects on mental state, physical health, and mortality risk (Cacioppo and Cacioppo, 2014). Vole species provide a unique opportunity to study the mechanisms underlying different types of social relationships, as these rodents form selective relationships with peers, and in some cases form socially monogamous partnerships with mates. These relationships may be differentially supported by a variety of factors, including increased “prosocial” factors such as reward from contact with familiar animals, or altered “antisocial” factors such as reduced fear and aggression toward familiar peers. We provide an overview of research on the reward mechanisms supporting mate and peer relationships in voles, and quantify the reinforcing properties of mate and peer relationships. Specifically, we assess the reinforcing effects of contact with a known social partner in mate vs. peer relationships within a socially monogamous species (prairie voles), and in peer relationships across species with different mating systems (meadow vs. prairie voles). These comparisons will elucidate whether mechanisms supporting social relationships are more consistent across types of relationships within a species, or within peer relationships across species. We particularly focus on the role of social reward because of its known role in different relationships—including mother-infant interactions, mate bonds, and social play (Trezza et al., 2011)—and discuss links to signaling pathways that may underlie differences in social preferences and motivation.

Peers vs. mates: what’s sex got to do with it?

In humans and other social species, friendships and peer relationships regularly form between individuals who are not reproductive partners. Disorders that affect social behavior often impact these peer relationships (DSM V, 2013), but most of what is known about the neurobiology of social attachment comes from the study of strong, rewarded reproductive relationships between mates or between parents and offspring (Resendez et al., 2016; Mattson et al., 2001). Relatively little work has explored the neurobiology of peer social relationships in mammals (Anacker and Beery, 2013). In particular, it is unknown to what extent peer social relationships rely on reward pathways that reinforce reproductive relationships between mates or between parents and offspring.

Prairie and meadow voles: models for understanding relationship types and substrates

Vole species display diverse social behaviors in the wild, allowing for comparative studies of species that share or differ in specific behaviors. In the field, socially monogamous prairie voles often form lasting partnerships with mates and reside in family groups (Getz et al., 2005; Ophir et al., 2008). In the laboratory, they exhibit selective preferences for their mates (e.g. Williams et al., 1992) as well as for familiar same-sex peers (Beery et al., 2018; DeVries et al., 1997). Because of these selective social relationships, prairie voles have been hailed as an emerging model organism for the translational study of human social deficits in disorders such as autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia (King et al., 2016; Lim et al., 2005; McGraw and Young, 2010; Modi and Young, 2012; Sadino and Donaldson, 2018).

The meadow vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus) is a closely related species that exhibits seasonal group living in the absence of monogamy (Getz, 1972; Madison, 1980; Boonstra et al., 1993). Females defend exclusive territories during summer months, but shift to social nesting with same- and opposite-sex peers in the winter, non-breeding season (Madison et al., 1984). In the laboratory, females form lasting and specific same-sex partner preferences in short, winter-like day lengths (SD, 10 h light: 14 h dark) (e.g. Parker and Lee, 2003; Beery et al., 2008; Anacker et al., 2016b). Male meadow voles are less territorial than females in the summer (Madison, 1980), and do not exhibit changes in peer social preferences with day-length in the laboratory, but also exhibit same-sex partner preferences for cage-mates (Beery et al., 2009).

The selective social preferences for familiar peers that are characteristic of prairie and meadow voles are not present in other social or socially tolerant rodents (mice: Beery et al., 2018; rats: Schweinfurth et al., 2017; degus: A. Beery and N. Insel, personal communication), making voles important models of selective relationships between peers and/or mates.

Investigation of the similarities and differences between these types of selective relationships within and across vole species will inform our understanding of how the behaviors and underlying pathways vary or are conserved. For instance, stress and glucocorticoid signaling impair formation of social preferences in females for mates (prairie voles) and peers (meadow voles), suggesting a potentially common mechanism for social avoidance (DeVries et al., 1996; Anacker et al., 2016b). In contrast, oxytocin appears to alter social selectivity for peers and mates in different brain regions and in different ways (Ross and Young, 2009; Beery and Zucker, 2010; Anacker et al., 2016a; Christensen and Beery, 2018), indicating that peer relationships must be studied separately.

Reward signaling and affiliative behavior in voles

A critical role for nucleus accumbens (NAcc) dopamine signaling has been established in the formation of pair bonds in male and female prairie voles. Centrally administered dopamine receptor agonists promote partner preference formation in male and female prairie voles, and mating induces increased extracellular dopamine in females and an increase of co-labeled fos and dopaminergic (tyrosine hydroxylase positive) cells in males (Aragona et al., 2003; Gingrich et al., 2000, 2000; Northcutt and Lonstein, 2009). Mating robustly elevates dopamine across species, however, and female meadow and prairie voles demonstrate similar levels of extracellular dopamine release during mating (Curtis et al., 2003)—thus dopamine signaling alone is not sufficient to lead to pair bonds. Decades of research have established critical roles of oxytocin and vasopressin signaling in pair-bonding and social behavior (reviewed elsewhere, e.g. Carter and Keverne, 2009; Anacker and Beery, 2013; Beery et al., 2016; Walum and Young, 2018). While oxytocin receptor (OTR), vasopressin V1a receptor, and dopamine receptor antagonists can each block PP formation independently, concurrent activation of OTR and dopamine D2 receptors in the NAcc are necessary for partner preference formation in mates (Liu and Wang, 2003).

Dopamine D1 and D2 receptors appear to have different roles in bond formation and maintenance in prairie voles. D2 receptor antagonists administered centrally or in the NAcc prevent partner preference formation in males and females (Aragona et al., 2006; Gingrich et al., 2000; Wang et al., 1999). D1 receptors are upregulated in the NAcc following pair bonding, and blockade of D1 receptors inhibits partner preference formation in males but not females. Furthermore, D1 antagonists prevent selective aggression in males, and dopamine release in the NAcc shell in males is positively correlated with attack frequency toward an intruder (Aragona et al., 2006; Resendez et al., 2016; Wang et al., 1999).

Opiate signaling also plays a role in behaviors relevant to pair-bonding. In prairie voles of both sexes, blockade of κ-opioid receptors in the NAcc shell abolishes selective aggression, and activation of these receptors causes partner aversion (Resendez et al., 2016, 2012). μ-opioid receptor antagonists in the dorsal striatum of females inhibit mating and partner preference, while those in the dorsomedial shell inhibit only partner preference (Resendez et al., 2013), and antagonizing μ-opioid receptors by administering naloxone also prevents males from forming a conditioned place preference for a chamber associated with repeated mating with a female (Ulloa et al., 2018). In rats, the rewarding and aversive effects of opioids in the CPP are dependent on DA activity in the mesolimbic system (Bals-Kubik et al., 1993; Shippenberg et al., 1993; Margolis et al., 2003), and both dopamine and opioid signaling relate to pair bonding in prairie voles (Resendez et al., 2016).

Research in meadow voles has established important roles for many of the neurochemical substrates involved in prairie vole pair-bonding in meadow vole same-sex partner preferences (albeit in different brain regions), including oxytocin signaling and corticotropin releasing factor receptor density (Beery and Zucker, 2010; Beery et al., 2014; Beery, 2015; Anacker et al., 2016a). In contrast, dopamine signaling likely only plays an important role in pair-bonding with mates; administration of dopamine receptor antagonist at a dose that prevents pair-bonding in prairie vole mates did not block the formation of same-sex partner preferences for a cage-mate in meadow voles (Beery and Zucker, 2010). Whether dopamine signaling is necessary or sufficient to promote peer relationships in prairie voles is currently under investigation (N. Lee and A. Beery, personal communication).

Because DA appears to mediate prairie vole mate bonds but not meadow vole peer bonds, an assay which more directly assess the socially rewarding aspects of these different types of relationships in meadow and prairie voles may indicate differences in the neurobiological pathways supporting them.

Measuring reward versus preference

Selective preferences for familiar mates and peers have most frequently been assessed using the partner preference test (PPT), developed in the laboratory of C. Sue Carter (Williams et al., 1992). In this assay, a test animal is placed in the center of a three-chambered apparatus and can choose to spend time alone or engage in side-by-side contact (huddling) with a tethered familiar or novel conspecific over the duration of a three-hour test. This test has repeatedly revealed that prairie voles exhibit robust preferences for mates over strangers, and that both female prairie and meadow voles exhibit preferences for familiar vs. novel same-sex peers (DeVries et al., 1997; Beery et al., 2018; Parker and Lee, 2003; Beery et al., 2008, 2009; Beery and Zucker, 2010; Anacker et al., 2016a, 2016b). While these preferences are robust, the PPT is not a direct measure of social motivation—subjects do not need to expend effort to spend time in contact. Huddling preferences may therefore represent reward from contact with a familiar individual and/or greater social tolerance for a familiar animal relative to an unfamiliar one. The relative levels of reward experienced in same- versus opposite-sex interactions are currently unknown, both within a species that exhibits both types of relationships (prairie voles) and across species that exhibit selective peer relationships (prairie and meadow voles). Assays involving conditioned place preference (reported here) and/or operant conditioning for peer or mate exposure (ongoing in our lab) will provide behavioral evidence for the mechanisms supporting these different kinds of relationships.

Study overview

We assessed reinforcing properties of social cohabitation with familiar peers or mates versus isolation using the socially conditioned place preference test (SCPP). The SCPP is a social adaptation of the conditioned place preference test that has historically been used to evaluate the reward associated with drug and alcohol consumption (Panksepp and Lahvis, 2007). In the SCPP version of the test, an animal is first exposed to two novel and distinct cues, such as different beddings, to assess baseline preferences for each. One bedding cue is then paired with social housing, while the other is paired with isolate housing, and animals are housed in alternation in the two conditions for several days. The subject is then placed back in the choice arena and allowed to choose between the different bedding cues in the absence of social stimuli. Shifts in time spent on the socially associated bedding are thought to positively correlate with the reward associated with social contact. Prior studies have used the SCPP to demonstrate, for example, strain differences in social conditioning in inbred strains of mice (Panksepp and Lahvis, 2007), and the importance of oxytocin for such social reinforcement (Dölen et al., 2013). We utilized the SCPP test, in addition to the PPT, in order to understand whether or not the role of reward versus social tolerance differed between mate and peer relationships, or by species differences in mating system.

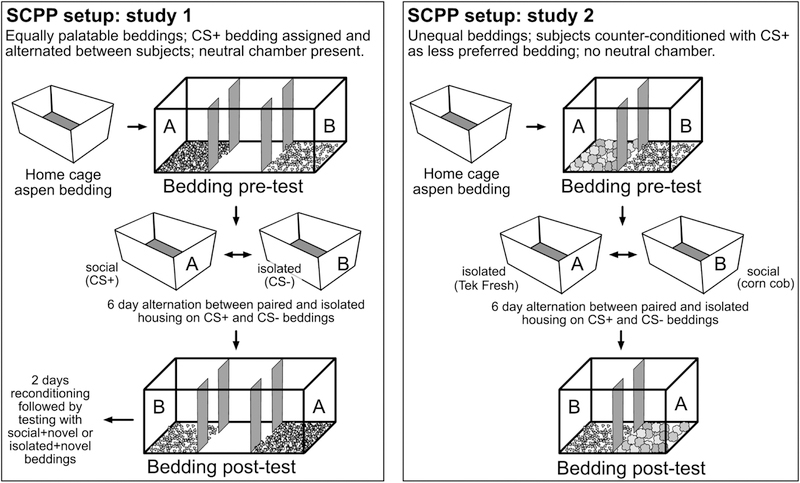

In study 1 (figure 1), we compared the relative social reward experienced in A) prairie voles housed with same-sex vs. opposite-sex (mate) partners, B) prairie voles vs. meadow voles housed with same-sex conspecifics, and C) short-day vs. long-day housed meadow voles. SCPP tests in study 1 were conducted in a three-chambered apparatus with a neutral center chamber in order to avoid forced bedding choice, and stimulus beddings were equally preferable and randomly assigned (not counter-conditioned) in order to maximize our ability to detect conditioning both toward and away from each cue (Prus et al., 2009). Additional conditions assessed whether conditioning occurred to beddings alone over time (control condition), and whether changes in bedding preference represent conditioning toward social contact or away from social isolation (social approach vs. isolation avoidance condition). In a smaller follow-up study (study 2, Figure 3), SCPP tests were conducted in a two-chambered forced choice apparatus with counter-conditioning (Dölen et al., 2013; Prus et al., 2009) in order to maximize our ability to detect increases in time spent on the initially less-preferred, socially-associated bedding. We used this paradigm to ask whether SD meadow voles might show signs of social reinforcement in a setting designed to maximize their detection. We also tested prairie voles housed in long day-lengths in this format, as we did not include this group in study 1, and a separate study led us to prefer this day-length for future studies of peer social preferences in prairie voles (Lee et al., 2017). Deeper understanding of the relative roles of motivation and reward in promoting social preferences will provide an essential foundation for future translational study of sexual and non-sexual social relationships.

Figure 1:

Depiction of conditioning paradigm. Animals underwent a 30-minute pre-test during which they could spend time on two novel beddings in opposite chambers. Animals were then housed overnight in their home cage before being placed in a novel, opaque cage and alternately housed on one bedding with their partner for 24 hours (study 1: randomly assigned paperchip or corncob bedding; study 2, corncob), then on the other bedding without their partner for 24 hours. After 6 alternating 24-hour conditioning periods, voles underwent a 30 minute post-test with the two beddings. In the control condition, voles were socially housed on both bedding types.

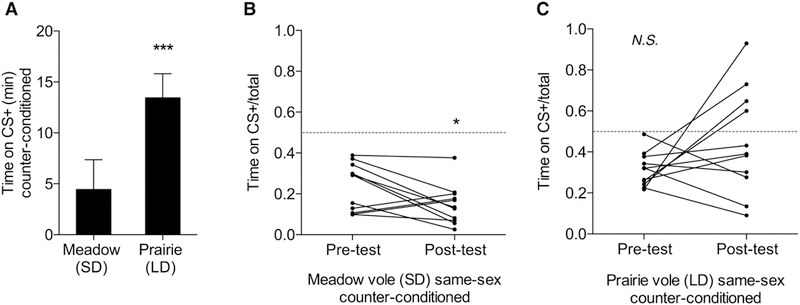

Figure 3:

Study Two conditioning results. A. LD female prairie vole peers spent significantly more time on CS+ bedding than SD female meadow peers (p=0.0019, unpaired t-test). B. Meadow peers demonstrated a significant decrease in the proportion of time spent on CS+ bedding (p=0.042, paired t-test). C. There was no significant shift in proportion of time spent on CS+ bedding in the prairie group (p=0.156, paired t-test). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.005.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Subjects

Prairie and meadow voles were bred locally at Smith College. Meadow voles were descended from a former UC Berkeley colony, outbred to voles trapped in Hampshire County, MA every three years. Prairie voles were descended from the colony of Dr. C. Sue Carter housed at Northeastern University, consisting of colony voles from Indiana University outbred to wild-caught voles trapped in Danville, Illinois. Voles were bred in long day lengths (14h light:10h dark, lights off at 5pm EST) and weaned at d19 (meadow voles) or d21 (prairie voles) into single-sex groups. Within a week, females were separated into sibling pairs, and transferred to short day lengths (10h light:14h dark; lights off at 5pm EST) or maintained in long days. Prairie voles used for mate comparisons were established multiparous breeders housed in long day lengths. Voles were housed in clear plastic cages (22×48×25cm) with aspen bedding and nesting materials (Enviro-dri bedding, a cotton Nestlet, and a white PVC hiding tube). Food (Lab Diet 5015 for meadow voles; Lab Diet 5015 mixed with 5326 for prairie voles) and water were available ad libitum, with every-other-day supplementation with fresh produce (apple or sweet potato). Meadow and prairie voles were housed in separate rooms.

All subjects were female, except both male and female members of the prairie vole mate pairs were tested. Behavioral testing was conducted simultaneously on both members of a pair to avoid isolation effects on one member of the pair. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the Smith College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Study Design

Study 1: Socially conditioned place preference using randomized beddings

The first study assessed partner preference and socially conditioned place preference in meadow and prairie voles. Female same-sex groups consisted of 20 pair-housed voles per species. 12 prairie vole mates were tested (6 male, 6 female). Same-sex pairs were housed in the short-day lengths that promote social behavior in meadow voles (social preferences in prairie voles are not day-length dependent (Lee et al., 2017)). At d92–105 of age, one vole from each pair (n = 10/group) underwent a partner preference test. Four days later, all subjects (n = 20/group) underwent SCPP pre-tests, conditioning, and post-tests (described in detail below) with randomly assigned social or isolate beddings (Figure 1a). Animals were then reconditioned for two days prior to a social approach/isolation avoidance test (Panksepp and Lahvis, 2007). The PPT and SCPP testing used different three-chambered apparatus designs to avoid carry-over effects (see detailed descriptions below).

A separate cohort of pair-housed adult female meadow voles underwent the control condition (n = 20), consisting of the main study procedure including pre-test, 6 days of conditioning, and a post-test, followed by two days of reconditioning and a social approach/isolation avoidance test. In the control condition, subjects were socially housed on both bedding types throughout the conditioning paradigm, and the “social” and “isolate” beddings in the social approach/isolation avoidance tests were the beddings from the first and second day of conditioning respectively. Pre- versus post-conditioning scores were examined to assess whether bedding preferences shifted over time in the absence of social connotations.

Study 2: Socially conditioned place preference using counter-conditioning

Experimentally naïve pair-housed female LD prairie vole and SD meadow voles (n = 12 meadow, 18 prairie) underwent counter-conditioned SCPP testing (figure 1b) at d70-d80. This test was used to maximize capacity to see increases in preference for social bedding. Pilot testing indicated that voles prefer TEK-Fresh bedding to corncob; thus social housing was paired with the less preferred corncob bedding, while isolation was paired with TEK-Fresh bedding. In order to assess counter-conditioned voles, any animal that spent more time on corncob bedding during the pre-test (n = 1 meadow, 7 prairie) was excluded from analysis. Short day meadow voles were chosen because females are most social during the winter, as modeled by short day-lengths in the lab (Madison and McShea, 1987; Beery et al., 2008), whereas prairie voles do not exhibit day-length differences in social preferences (Lee et al., 2017) and are most often studied in long day lengths (Beery et al., 2018; DeVries et al., 1997).

A separate cohort (n = 10) underwent the control paradigm for this study, as described for study one.

Partner Preference Tests

PPTs were conducted in a three-chambered apparatus consisting of three 17 cm × 28 cm x 12.5 cm chambers connected via tubes, as previously described (Beery et al., 2008, 2009; Beery and Zucker, 2010; Ondrasek et al., 2015). Focal animals were placed in the rear, isolated chamber, and could spend time alone, or with the partner or stranger voles tethered in opposite cages in the front of the apparatus for the duration of the three-hour test. On the day before the assay, focal voles were placed in the rear chamber of the apparatus for 10 minutes or until they entered each of the chambers at least once. Time in each chamber was scored, as well as time in side-by-side contact with the partner or stranger. Partner preference was defined as significantly more time huddling with the partner than the stranger within groups. Although prior tethering does not appear to affect subsequent focal performance in a PPT (Ondrasek et al., 2015), only one animal per pair was used as a focal in the PPT.

Socially Conditioned Place Preference Test (Study 1)

SCPP testing was conducted in a linear three-chambered apparatus (75 × 20 × 30 cm). End chambers were filled to similar heights with 150g of corncob and 250g of paperchip bedding (Anderson’s Bed-o’Cobs 1/8”; PC60035, PharmaServ Inc.); the center chamber was left empty. In pilot tests, we found that voles did not exhibit significant preferences for either of these beddings.

Pairs were randomly assigned to receive corncob or paperchip as the socially associated bedding. Voles underwent a 30-minute bedding preference pre-test on day one, after which they were transferred back to their aspen-bedding home cage. The following day, pairs were transferred into an opaque white cage on either corn cob or paperchip bedding. Voles were housed socially on this initial bedding for 24 hours, then transferred into isolate housing on the opposite bedding for 24 hours. Voles underwent six days of conditioning, alternating between social and isolate housing (Figure 1a). On the last day of conditioning, voles were transferred from isolate housing into a 30-minute post-test, conducted in the same manner as the pre-test above.

Following the SCPP post-test, same-sex pairs were reunited in a fresh social conditioning cage, and underwent two additional days of conditioning (social, then solitary). Voles then underwent a social approach and isolation avoidance assessment (n = 10 isolate, 10 social per group) as described in Panksepp and Lahvis (2007). One chamber contained either the social or isolate bedding, while the opposite chamber contained aquarium gravel, which served as a novel bedding. Animals were randomly assigned to be tested with novel vs. social or novel vs. isolate beddings to assess their baseline propensity for novelty, and the extent to which they sought or avoided social interaction and isolation associated cues.

Counter-conditioned Socially Conditioned Place Preference Test (Study 2)

Study two used counter-conditioning to maximize the ability to detect increases in preference for socially associated beddings in same-sex pairs of SD meadow voles or LD prairie voles. Testing was conducted in a two-chambered apparatus to remove the variable of non-bedding center chamber time. All voles were socially conditioned on corncob bedding (CS+) and isolate conditioned on TEK-Fresh bedding (CS-). Pilot testing indicated that TEK-Fresh bedding was strongly preferred over corncob bedding; any voles demonstrating a reversed preference in the pretest were excluded from analysis. An increase in preference for corncob bedding should demonstrate a conditioned preference toward social housing.

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using JMP 8 (SAS) and Prism 7 (GraphPad Software). Group differences were assessed using t-tests for two-group comparisons, or by one-way ANOVA for comparisons between multiple groups. Significant ANOVAs were followed by post-hoc Tukey’s HSD tests. Paired t-tests were used for within group comparisons for the SCPP studies. Three animals were excluded from SCPP analysis (and one from PPT analysis) on the basis of skull malformations caused by tooth overgrowth, as detected in post-mortem screening of all subjects. Cage mates were treated as independent samples in the SCPP studies as no correlation was found in time spent on socially conditioned bedding (CS+) between cage-mates in any single group (p = 0.5596, r2 = 0.051 to p = 0.9938, r2 = 0.000017) or across pooled subjects (p = 0.2423, r2 = 0.045). Effect sizes were calculated and reported for ANOVA using η2 and for t-tests using Cohen’s d. The Effect Size Calculator for T-Test (http://www.socscistatistics.com/effectsize/Default3.aspx) was used to estimate Cohen’s d for t-tests. All tests were conducted two-tailed, and results were deemed significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Partner preference

Unpaired t-tests revealed partner preferences in all groups, demonstrated by significantly more huddling time spent with the partner versus the stranger (LD meadow: p = 0.0015, d = 1.6752, n = 10; SD meadow: p = 0.0237, d = 1.1782, n = 9; SD prairie: p = 0.0009, d = 1.7795, n = 10). No significant difference in partner huddling or stranger huddling time was found between groups via one-way ANOVAs. Time huddling with the partner in the PPT was not correlated with time on the socially associated (CS+) bedding in the SCPP post-conditioning (p = 0.4341, r2 = 0.023, n = 29 pooled across groups).

SCPP Study 1

SCPP pre- and post-test data were compared using paired t-tests to assess conditioning within groups; one-way ANOVA was used to assess differences in time on the CS+ bedding across groups. In order to account for time spent in the center chamber in study 1, the metric CS+/total bedding time was used to assess the proportion of time animals spent on social versus isolate bedding.

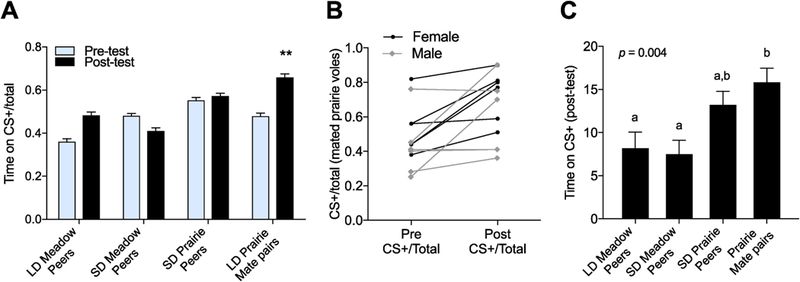

Same-sex LD and SD meadow voles and SD prairie voles did not condition toward the social bedding (p = 0.09, d = 1.8325, n = 20; p = 0.28, d = 1.2409, n = 19; p = 0.78, d = 0.3797, n = 18 respectively, figure 2A), as measured by time CS+/Total Bedding Time from pre- to post-test. In contrast, prairie vole mates showed a significant increase in proportion of time spent on CS+ bedding between the pre-and post-test (p > 0.0073 effect of conditioning, p = 0.1920 effect of sex, 2 way-ANOVA, figure 2A). While there was no sex difference, separate analysis by sex revealed that the female subset significantly conditioned toward the social bedding (p = 0.0167, d = 1.285, n = 6), while the male subset did not reach significance on its own (p = 0.1345, d = 0.7997, n = 6).

Figure 2:

Study One conditioning results. A. LD prairie mate pairs demonstrated a significant increase in proportion of time spent on CS+ bedding (p = 0.0049, paired t-tests). B. Individual data for prairie vole mate pairs showing male and female conditioning (2-way ANOVA: effect of conditioning: p > 0.0073; no effect of sex: p = 0.1920). C. No significant differences were observed between peer groups or prairie vole groups, but prairie vole mate pairs spent significantly more time on the CS+ bedding than meadow vole peer groups (one-way ANOVA). Letters denote groups that are significantly different with post-hoc Tukey’s HSD. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.005, NS = not significant.

There were significant differences between groups in the total amount of time spent on CS+ bedding between groups (p = 0.004, ANOVA, figure 2C). While peer groups did not differ significantly, prairie vole mates spent significantly more time on CS+ bedding than either of the meadow peer groups (LD meadow peers: p = 0.0237; SD meadow peers: p = 0.0125, figure 2C)

Control data:

SD meadow voles did not demonstrate a shift in bedding preference in the absence of social cues associated with the beddings (p = 0.1326, d = 0.4481, n = 20, paired t-test).

Isolation avoidance and social approach:

Social approach and isolation avoidance scores were analyzed within groups via paired t-tests. SD female meadow voles from the bedding control condition demonstrated a significant preference for the novel versus familiar bedding (p < 0.0001, d = 1.6741, n = 20), regardless of whether the familiar bedding was the first (p = 0.0190, d = 1.2306, n = 11) or second (p = 0.0013, d = 2.4922, n = 9) that they had been presented with during conditioning. Consistent preference for novel bedding indicated that the test could not distinguish between isolation avoidance vs. social approach. LD meadow voles that completed SCPP testing also maintained a novelty preference versus both social (p = 0.0428, d = 1.1132, n = 10) and isolate bedding (p = 0.0095, d = 1.7158, n = 10). No preference was seen between the novel bedding and the social or isolate beddings in other groups: SD meadow (p = 0.0757, d = 1.0809, n = 9 social; p = 0.1379, d = 0.8606, n = 10 isolate) or SD prairie voles (p = 0.9843, d = 0.0129, n = 8 social; p = 0.9970, d = 0.0029, n = 10 isolate).

SCPP Study 2:

In study two, the differences in percentage of time spent on CS+ bedding during the pre-and post-test were assessed using paired t-tests, and group differences were examined using an unpaired t-test. Prairie voles spent a significantly higher proportion of time on social versus isolate bedding than did meadow voles during the post-test, (p = 0.0019, d = 1.5403, n = 11 per group, Figure 3A). Meadow voles displayed a shift away from social bedding between pre- and post-test (p = 0.042, d = 0.8054, n = 11, Figure 3B). Prairie voles showed a non-significant increase in time spent on the socially associated bedding following conditioning (p = 0.156, d = 0.698, n = 11, Figure 3C). Control meadow voles showed no shift in bedding preference between pre- and post-test (p = 0.812, d = 0.1215, n = 6).

DISCUSSION

Partner preference tests have been a primary method of assessing relationship formation in both opposite- and same-sex partnerships in voles for decades. These tests directly assess the selectivity of relationships, but do not address reward, per se. Both meadow and prairie voles demonstrated robust partner preferences for same-sex peers in the present study, but neither species demonstrated socially conditioned place preferences for cues associated with long-term same-sex cage-mates. This is consistent with the dopamine-independence of peer partner preferences in meadow voles (Beery and Zucker, 2010), and suggests that peer relationships may be similarly mediated across prairie and meadow voles. This hypothesis may be further examined by assessing whether dopamine signaling is necessary for the formation or expression of peer partner preferences in prairie voles.

Both males and females in opposite-sex prairie vole mate pairs formed significant place preferences for cues associated with their long-term mates. This demonstrates that the conditioning paradigm was sufficient for SCPP to form in circumstances in which social reward is expected. Prairie vole mate relationships rely on dopamine signaling as well as opioid pathways (see introduction), and have been associated with behavioral measures of reward (Liu et al., 2011; Ulloa et al., 2018), consistent with this finding. In a recent examination of SCPP in prairie vole mates, Ulloa et al. (2018) found that mating with or without brief cohabitation induced SCPP in males, and that this conditioning was prevented by the μ-opioid receptor antagonist naloxone. It is of interest that female prairie voles did not form conditioned place preferences in the study above; the female subset of mated prairie voles in the present study exhibited pronounced conditioned place preferences. While this difference could be due to differences in SCPP testing protocols, bond duration may also play an important role in conditioning. Females in our study had produced multiple litters with their long-term mates, while females in the Ulloa et al. study were recently paired. While social preferences can form quickly, continued changes occur in both behavioral and physiological measures of social bonding with extended cohousing, and production of young (Aragona et al., 2006; Lewis et al., 2017). Importantly, the role of behavioral reward in long-term mate but not peer relationships indicates differences in the behavioral and neural mechanisms underlying peer versus mate social behavior in prairie voles.

While the conditioned place preference test is a well-established measure, there are key differences in test design that can reveal or obscure conditioning (Prus et al., 2009). Our second peer study used counter conditioning and a forced choice testing chamber in order to enhance detection of social conditioning. For instance, use of counter-conditioning, but not randomly assigned beddings, led to detection of nicotine conditioned place preferences in mice, and the removal of the center chamber forces the animals to directly choose between stimuli (Prus et al., 2009). In this context, meadow voles displayed a significant decrease in time spent on CS+ bedding following conditioning, indicating a lack of overt reward or reinforcement from peer relationships. Prairie vole peers spent significantly more time on the CS+ bedding than did meadow voles, but did not show a significant increase from pre-test to post-test. Ongoing studies in our laboratory indicate that prairie vole peers may form SCPP under some circumstances (for instance following pairing with new partners in adulthood), and the role of timing and manipulations has yet to be determined.

Huddling times in peer PPTs were not correlated with SCPP measures, indicating that these assays are measuring different aspects of social behavior and incentive, and that selectivity for a partner does not inherently translate to the experience of social reward. While partner preferences between female peers are typically robust, there are some situations in which they are superseded by environmental or social stimuli. Female meadow voles housed in cold conditions opt to huddle with a group of strangers versus a single known peer (Ondrasek et al., 2015), and female prairie voles express preferences for an unknown male versus a familiar same-sex peer (DeVries et al., 1997). These results indicate that female voles may demonstrate peer selectivity even when this is not their optimal relationship. Interestingly, gregarious species such as mice and ground squirrels display SCPP in similar conditioning paradigms (Dölen et al., 2013; Lahvis et al., 2015; Panksepp and Lahvis, 2007), but mice do not display partner preferences in the PPT (Beery et al., 2018), further underscoring the distinction between selectivity and reward. The disconnect between behavior in assays of social preference and social reinforcement highlights the necessity of moving beyond single-assay measures of sociality, and the importance of studying selective social preferences outside the context of reward.

Control data revealed no shift in bedding preference in the absence of social cues in the first or second studies, indicating that shifts in bedding preference in the test groups were conditioning-dependent. The social approach and isolation avoidance test has previously been used to demonstrate avoidance of the CS- stimuli and approach to the CS+ stimuli relative to neutral, novel beddings (Panksepp and Lahvis, 2007). In study one, our control animals significantly preferred novel to familiar stimuli; thus, we could not distinguish social approach from isolation avoidance using this paradigm.

Together, these results indicate that mate but not peer social interactions are reinforcing for voles, and that important mechanistic differences underlie these different types of relationships even within species. While partner preference tests have yielded important insights into the mechanisms of bond formation, socially conditioned place preference tests, operant conditioning, and other measures that elucidate reward and motivation will be important contributions to the study of sociality among voles.

Highlights.

-

o

Meadow and prairie voles prefer familiar peers, but differ in mating system

-

o

Motivational aspects underlying these relationships are relatively understudied

-

o

Social housing with a mate conditioned place preferences in prairie voles

-

o

Social housing with a peer did not condition place preferences in peers of either species

-

o

Place preference and partner preference metrics were not correlated

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Katrina Blandino, Lydia Ross, Katherine Freitas, and Jennifer Christensen for their assistance with behavioral assays and scoring, and to the staff of the animal care facility. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (award R15MH113085).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Anacker AMJ, Beery AK, 2013. Life in groups: the roles of oxytocin in mammalian sociality. Front. Behav. Neurosci 7, 185 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anacker AMJ, Christensen JD, LaFlamme EM, Grunberg DM, Beery AK, 2016a. Septal oxytocin administration impairs peer affiliation via V1a receptors in female meadow voles. Psychoneuroendocrinology 68, 156–162. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anacker AMJ, Reitz KM, Goodwin NL, Beery AK, 2016b. Stress impairs new but not established relationships in seasonally social voles. Horm. Behav 79, 52–57. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragona BJ, Liu Y, Curtis JT, Stephan FK, Wang Z, 2003. A Critical Role for Nucleus Accumbens Dopamine in Partner-Preference Formation in Male Prairie Voles. J. Neurosci 23, 3483–3490. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03483.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragona BJ, Liu Y, Yu YJ, Curtis JT, Detwiler JM, Insel TR, Wang Z, 2006. Nucleus accumbens dopamine differentially mediates the formation and maintenance of monogamous pair bonds. Nat. Neurosci 9, 133–139. 10.1038/nn1613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bals-Kubik R, Ableitner A, Herz A, Shippenberg TS, 1993. Neuroanatomical sites mediating the motivational effects of opioids as mapped by the conditioned place preference paradigm in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 264, 489–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beery AK, 2015. Antisocial oxytocin: complex effects on social behavior. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci 6, 174–182. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.11.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beery AK, Christensen JD, Lee NS, Blandino KL, 2018. Specificity in Sociality: Mice and Prairie Voles Exhibit Different Patterns of Peer Affiliation. Front. Behav. Neurosci 12 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beery AK, Kamal Y, Sobrero R, Hayes LD, 2016. Comparative neurobiology and genetics of mammalian social behavior., in: Sociobiology of Caviomorph Rodents: An Integrated View Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Beery AK, Loo TJ, Zucker I, 2008. Day length and estradiol affect same-sex affiliative behavior in the female meadow vole. Horm. Behav 54, 153–159. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beery AK, Routman DM, Zucker I, 2009. Same-sex social behavior in meadow voles: Multiple and rapid formation of attachments. Physiol. Behav 97, 52–57. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beery AK, Vahaba DM, Grunberg DM, 2014. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor densities vary with photoperiod and sociality. Horm. Behav 66, 779–786. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2014.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beery AK, Zucker I, 2010. Oxytocin and same-sex social behavior in female meadow voles. Neuroscience 169, 665–673. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonstra R, Xia X, Pavone L, 1993. Mating system of the meadow vole, Microtus pennsylvanicus. Behav. Ecol 4, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, 2014. Social Relationships and Health: The Toxic Effects of Perceived Social Isolation. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 8, 58–72. 10.1111/spc3.12087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, Keverne EB, 2009. The neurobiology of social affiliation and pair bonding, in: Hormones, Brain and Behavior, Vol. 1, 2nd Ed Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego, CA, US, pp. 137–165. 10.1016/B978-008088783-8.00004-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen JD, Beery AK, 2018. Oxytocin affects meadow vole social preferences differently by brain region and duration. Poster PS20055 Int. Congr. Neuroendocrinol. Tor. Can 10.6084/m9.figshare.7221428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis JT, Stowe JR, Wang Z, 2003. Differential effects of intraspecific interactions on the striatal dopamine system in social and non-social voles. Neuroscience 118, 1165–1173. 10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00032-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries AC, DeVries MB, Taymans SE, Carter CS, 1996. The effects of stress on social preferences are sexually dimorphic in prairie voles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 93, 11980–11984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries Johnson, C.L., Carter CS, 1997. Familiarity and gender influence social preferences in prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster). Can. J. Zool 75, 295–301. [Google Scholar]

- Dölen G, Darvishzadeh A, Huang KW, Malenka RC, 2013. Social reward requires coordinated activity of nucleus accumbens oxytocin and serotonin. Nature 501, 179–184. 10.1038/nature12518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getz LL, 1972. Social structure and aggressive behavior in a population of Microtus pennsylvanicus. J. Mammal 53, 310–317. [Google Scholar]

- Getz LL, McGUIRE B, Carter CS, 2005. Social organization and mating system of free-living prairie voles Microtus ochrogaster: a review

- Gingrich B, Liu Y, Cascio C, Wang Z, Insel TR, 2000. Dopamine D2 receptors in the nucleus accumbens are important for social attachment in female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster). Behav. Neurosci 114, 173–183. 10.1037/0735-7044.114.1.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LB, Walum H, Inoue K, Eyrich NW, Young LJ, 2016. Variation in the Oxytocin Receptor Gene Predicts Brain Region-Specific Expression and Social Attachment. Biol. Psychiatry 80, 160–169. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahvis GP, Panksepp JB, Kennedy BC, Wilson CR, Merriman DK, 2015. Social conditioned place preference in the captive ground squirrel (Ictidomys tridecemlineatus): Social reward as a natural phenotype. J. Comp. Psychol 129, 291–03. 10.1037/a0039435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NS, Goodwin NL, Freitas KE, Beery AK, 2017. Comparative studies of affiliation, aggression, and reward in monogamous and promiscuous voles. Poster 15814 Soc. Neurosci Wash. DC. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis R, Wilkins B, Benjamin B, Curtis JT, 2017. Cardiovascular control is associated with pair-bond success in male prairie voles. Auton. Neurosci 208, 93–102. 10.1016/j.autneu.2017.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim MM, Bielsky IF, Young LJ, 2005. Neuropeptides and the social brain: potential rodent models of autism. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. Off. J. Int. Soc. Dev. Neurosci 23, 235–243. 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wang Z, 2003. Nucleus accumbens oxytocin and dopamine interact to regulate pair bond formation in female prairie voles. Neuroscience 121, 537–544. 10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00555-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Young KA, Curtis JT, Aragona BJ, Wang Z, 2011. Social Bonding Decreases the Rewarding Properties of Amphetamine through a Dopamine D1 Receptor-Mediated Mechanism. J. Neurosci 31, 7960–7966. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1006-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison DM, 1980. Space Use and Social Structure in Meadow Voles, Microtus pennsylvanicus. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol 65. [Google Scholar]

- Madison DM, FitzGerald RW, McShea WJ, 1984. Dynamics of Social Nesting in Overwintering Meadow Voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus): Possible Consequences for Population Cycling. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol 9. [Google Scholar]

- Madison DM, McShea W, 1987. Seasonal changes in reproductive tolerance, spacing, and social organization in meadow voles: a microtine model. Am. Zool 27, 899–908. [Google Scholar]

- Margolis EB, Hjelmstad GO, Bonci A, Fields HL, 2003. κ-Opioid Agonists Directly Inhibit Midbrain Dopaminergic Neurons. J. Neurosci 23, 9981–9986. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-31-09981.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson BJ, Williams S, Rosenblatt JS, Morrell JI, 2001. Comparison of two positive reinforcing stimuli: pups and cocaine throughout the postpartum period. Behav. Neurosci 115, 683–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw LA, Young LJ, 2010. The prairie vole: an emerging model organism for understanding the social brain. Trends Neurosci 33, 103–109. 10.1016/j.tins.2009.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi ME, Young LJ, 2012. The oxytocin system in drug discovery for autism: animal models and novel therapeutic strategies. Horm. Behav 61, 340–350. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northcutt KV, Lonstein JS, 2009. Social contact elicits immediate-early gene expression in dopaminergic cells of the male prairie vole extended olfactory amygdala. Neuroscience 163, 9–22. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ondrasek NR, Wade A, Burkhard T, Hsu K, Nguyen T, Post J, Zucker I, 2015. Environmental modulation of same-sex affiliative behavior in female meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus). Physiol. Behav 140, 118–126. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ophir AG, Phelps SM, Sorin AB, Wolff JO, 2008. Social but not genetic monogamy is associated with greater breeding success in prairie voles. Anim Behav 75, 1143–1154. 10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.09.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp JB, Lahvis GP, 2007. Social reward among juvenile mice. Genes Brain Behav 6, 661–671. 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00295.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker KJ, Lee TM, 2003. Female meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus) demonstrate same-sex partner preferences. J. Comp. Psychol 117, 283–289. 10.1037/0735-7036.117.3.283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prus AJ, James JR, Rosecrans JA, 2009. Conditioned Place Preference, in: Buccafusco JJ (Ed.), Methods of Behavior Analysis in Neuroscience, Frontiers in Neuroscience CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton (FL: ). [Google Scholar]

- Resendez SL, Dome M, Gormley G, Franco D, Nevarez N, Hamid AA, Aragona BJ, 2013. -Opioid Receptors within Subregions of the Striatum Mediate Pair Bond Formation through Parallel Yet Distinct Reward Mechanisms. J. Neurosci 33, 9140–9149. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4123-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resendez SL, Keyes PC, Day JJ, Hambro C, Austin CJ, Maina FK, Eidson L, Porter-Stransky KA, Nevárez N, McLean JW, Kuhnmuench MA, Murphy AZ, Mathews TA, Aragona BJ, 2016. Dopamine and opioid systems interact within the nucleus accumbens to maintain monogamous pair bonds. eLife 5. 10.7554/eLife.15325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resendez SL, Kuhnmuench M, Krzywosinski T, Aragona BJ, 2012. -Opioid Receptors within the Nucleus Accumbens Shell Mediate Pair Bond Maintenance. J. Neurosci 32, 6771–6784. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5779-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross HE, Young LJ, 2009. Oxytocin and the neural mechanisms regulating social cognition and affiliative behavior. Front Neuroendocr 30, 534–47. 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadino JM, Donaldson ZR, 2018. Prairie Voles as a Model for Understanding the Genetic and Epigenetic Regulation of Attachment Behaviors. ACS Chem. Neurosci 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweinfurth MK, Neuenschwander J, Engqvist L, Schneeberger K, Rentsch AK, Gygax M, Taborsky M, 2017. Do female Norway rats form social bonds? Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol 71, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Shippenberg TS, Bals-Kubik R, Herz A, 1993. Examination of the neurochemical substrates mediating the motivational effects of opioids: role of the mesolimbic dopamine system and D-1 vs. D-2 dopamine receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 265, 53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V, Campolongo P, Vanderschuren LJMJ, 2011. Evaluating the rewarding nature of social interactions in laboratory animals. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci 1, 444–458. 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa M, Portillo W, Díaz NF, Young LJ, Camacho FJ, Rodríguez VM, Paredes RG, 2018. Mating and social exposure induces an opioid-dependent conditioned place preference in male but not in female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster). Horm. Behav 97, 47–55. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2017.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walum H, Young LJ, 2018. The neural mechanisms and circuitry of the pair bond. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 1 10.1038/s41583-018-0072-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Yu G, Cascio C, Liu Y, Gingrich B, Insel TR, 1999. Dopamine D2 receptor-mediated regulation of partner preferences in female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster): A mechanism for pair bonding? Behav. Neurosci 113, 602–611. 10.1037/0735-7044.113.3.602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JR, Catania KC, Carter CS, 1992. Development of partner preferences in female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster): The role of social and sexual experience. Horm. Behav 26, 339–349. 10.1016/0018-506X(92)90004-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]