Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major cause of acquired disability globally, and effective treatment methods are scarce. Lately, there has been increasing recognition of the devastating impact of TBI resulting from sports and other recreational activities, ranging from primarily sport-related concussions (SRC) but also more severe brain injuries requiring hospitalization. There are currently no established treatments for the underlying pathophysiology in TBI and while neuro-rehabilitation efforts are promising, there are currently is a lack of consensus regarding rehabilitation following TBI of any severity. In this narrative review, we highlight short- and long-term consequences of SRCs, and how the sideline management of these patients should be performed. We also cover the basic concepts of neuro-critical care management for more severely brain-injured patients with a focus on brain edema and the necessity of improving intracranial conditions in terms of substrate delivery in order to facilitate recovery and improve outcome. Further, following the acute phase, promising new approaches to rehabilitation are covered for both patients with severe TBI and athletes suffering from SRC. These highlight the need for co-ordinated interdisciplinary rehabilitation, with a special focus on cognition, in order to promote recovery after TBI.

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, sport-related concussion, neuro-rehabilitation, neuro-critical care, cognition

Clinical management in the acute stage of sports-related concussions

The awareness of the potential short- and long-term consequences of sports-related concussions (SRC) has increased markedly during the last decades. Conversely, the rules and regulations on the management of SRCs have evolved based on clinical management paradigms supported by experimental evidence of brain vulnerability post-injury and the possible lasting effects of repeated SRCs. At the sideline, acute management of an athlete who may have sustained an SRC should focus on a) concussion diagnosis and detection, including the recognition of warning signs and symptoms that indicate a more severe brain or spinal cord injury and b) adopting a strict removal from play protocol after an athlete has sustained an SRC. The broad scope of the literature has been recently reviewed at an international consensus meeting [1].

Risk factors for Sports Related Concussions

It is well established that concussions can have considerable adverse effects on cognitive functioning and balance in the first 24–72 hours following a SRC [2]. For most injured adult athletes, cognitive deficits, balance and symptoms improve rapidly during the first two weeks following injury [3, 4]. Some authors have suggested that the longer recovery times reported in more recent studies in part are due to changes in the medical management of concussion, with adoption of the gradual return to play recommendations from the Concussion in Sport Group statements [1, 5]. This topic was the subject of a recent detailed systematic review [3].

Having a past concussion is a risk factor for having a future concussion [6], and having multiple past concussions is associated with having more physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms prior to participation in a sporting season [3].

The strongest and most consistent predictor of slower recovery from concussion is the severity of a person’s acute and subacute symptoms following injury [7].

There are clear sex differences, which relate to differences in neck strength, injury mechanisms, and injury rates; however; although the literature is not conclusive, it supports that females, on average, take longer to recover—and they are more likely to have symptoms that persist for more than a month.

Injury severity characteristics (e.g. loss of consciousness, post-traumatic amnesia), pre-injury mental health problems, substance abuse, pre-injury headache/migraine history and prior concussions are not consistent predictors of recovery time in many studies; however methodological issues limit the interpretation of these studies.

Adolescents, and young adults with a pre-injury history of mental health problems or migraine headaches appear to be at somewhat greater risk for having symptoms for longer than one month. Those with ADHD or learning disabilities might require more careful planning and intervention regarding return to school, but they do not appear to be at substantially greater risk for persistent symptoms beyond a month.

Concussion detection and diagnosis

The definition of an SRC includes a transient functional impairment of brain function which could include a number of signs and symptoms, cognitive impairment, and neurobehavioral features [1]. Loss of consciousness, occurring in only 8–19% of SRCs, is not required for the diagnosis [8].

The sideline evaluation, aimed at recognition of the injury, provides the best opportunity for SRC diagnosis and for subsequent management. To recognize an SRC it is necessary to watch the sports event and the behavior of the player immediately after the time of impact. Due to the rapid and complex events occurring in modern sports, this may be a difficult task. Increasingly, video-assisted analysis of an event may be used where common factors associated with an SRC are easily observed including no attempt to resist the fall, seizures and/or a blank stare/vacant expression [9, 10].

After an SRC, a number of signs are common (Table 1). An important fact to remember is that the athlete may be almost symptom-free immediately after the time of impact, and experience evolving symptoms during the first post-injury minutes- hours. The most common short-lived symptoms experienced by the athlete include headache, confusion, dizziness, memory impairment and/or amnesia [1, 8, 11]. It must be emphasized that there is no simple “diagnosis” of SRC- instead it is a summary of a plethora of information that must be gathered by the individual who is medically responsible. These include knowledge of pre-injury status, injury mechanisms, presence of visual disturbance, and a combination of cognitive-, vestibulomotor-, ocular-, neurological-, cervical- and behavioral signs and symptoms [12]. A high degree of suspicion of SRC is warranted. The simple question “how do you feel on a scale 0–100?” may be informative and useful in the acute setting. The medical staff should also be aware that an athlete may disregard or underestimate or even refrain from reporting their symptoms, since they may have a strong motivation to continue with the sports activity.

Table 1.

Common observable signs associated with a sports-related concussion.

| Loss of consciousness |

| Slow getting up |

| Balance problems |

| Vacant look |

| Disorientated |

| Amnesia |

| Clutching the head |

| Facial injury |

There are different SRC recognition and management tools available, where the “Sport Concussion Assessment Tool” (SCAT) is plausibly the most validated and used, to date. The most recent version, the SCAT-5, was adopted by the Concussion in Sport group consensus meeting in Berlin, October 2016. It comprises different assessment stages allowing for the evaluation of e.g. symptoms, level of consciousness, cognitive and cranial nerve function, and balance as well as detecting potential warning signs indicating a severe brain injury [1, 13]. If the medical staff member knows the athlete well, and is familiar with his/her normal behavior, it may be easy to identify an aberrant level of functioning. The Concussion Recognition Tool 5 (CRT5) is the most recent revision of the Pocket Sport Concussion Assessment Tool introduced by the Concussion in Sport Group in 2005 that also may be used by the non-medical “laymen” person [14].

According to the SCAT-5, the sideline assessment may preferably be divided into two phases- first, a rapid sideline screening assessment. Then, if there is a suspicion of an SRC a more thorough “off-the-pitch” or “locker room” assessment is performed. Evaluation of the “Red Flags”, signs indicating a more severe brain or cervical injury (Table 2) that signals that the athlete should immediately be taken for medical evaluation, must be an integral part of the sideline assessment.

Table 2.

“Red flags” to for sideline assessments

| Neck pain or tenderness |

| Double vision |

| Weakness or tingling/burning in arms or legs |

| Severe or increasing headache |

| Seizure or convulsion |

| Loss of consciousness |

| Deteriorating conscious state |

| Vomiting |

| Increasingly restless, agitated or combative |

The acute, initial sideline screening should also include assessment of the observable signs (Table 1); most important being lying motionless on the ground, motor incoordination/balance problems, disorientation or confusion, blank or vacant stare and the presence of significant facial injury, the level of consciousness according to the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) Score and the cervical spine evaluation including presence of pain and range of motion. Cognitive abilities, including memory function, can be screened using simple questions, which include requests for information that the players should be aware of, such as what venue the player is in, name of the opposing team, the current score in the game and so forth. In the SCAT-5 these tools are named the Maddox questions. In general, cognitive tests describe lower sensitivity, but good specificity when used in SRC management [9].

If there is suspicion that an SRC has occurred after the initial sideline screening, a more thorough evaluation is warranted using the SCAT-5. It should be remembered that it takes ca 10–15 minutes to perform the entire SCAT-5 evaluation and that its interpretation is made easier if a pre-season, baseline assessment has been performed. The more detailed evaluation, the “off-the-pitch” or “locker-room” evaluation, includes evaluation of 22 symptom scored from 0–6 regarding the severity of the symptoms, which is filled out by the athlete. In addition, a more detailed cognitive testing is performed and balance test using the modified Balance Error Scoring System (mBESS) is performed which includes testing of Single-, Double- and Tandem leg stance. Due to the high frequency of visual disturbance following an SRC, tests of oculomotor function are gaining ground [9, 15]. The King-Dewick Test evaluates saccadic eye movement and may prove to be a useful test in the assessment of an athlete sustaining an SRC [16].

Early management and Remove-from-play protocol

If the Red Flag assessment raises the suspicion of a more severe brain or cervical injury, emergent measures according to the ABC concept apply including securing the airway and immobilisation of the cervical spine. The athlete needs to be carried from the field on a stretcher and emergently brought to nearest hospital for medical evaluation. In milder forms of injuries, by far the most common presentation of an SRC, the athlete must discontinue the sport session immediately and refrain from the sports activity on the same day after an SRC according to the concept of brain vulnerability (vide infra) [1]. A suspicion, based on the SCAT5, is enough to remove the athlete from play. The simple adage “If in doubt, sit them out” was first suggested by the CISG in 2002 [17]. It is recommended that athletes with suspected/diagnosed SRC should not be left alone during the first 1–2 hours, not use alcohol/recreational drugs, not be sent home alone and not drive in the acute post-injury period [14]. After this initial, acute phase, the graded-return-to play should then ensue. In brief, this protocol suggests a brief 24–48h period of cognitive and physical rest followed by a gradual increase in activity [18]. It should be emphasized that the exact degree and duration of rest have not been clearly established.

Why is then a removal-from-play protocol necessary and why cannot an asymptomatic player continue playing early after an SRC? These strict protocols have evolved from a clinical paradigm where slowed reaction times and impaired decision-making following a concussive injury place the athlete at increased injury risk by ongoing participation [19, 20]. There is also a theoretical risk based on physiological animal data whereby after an SRC, the brain is vulnerable for a second concussion for some time due to a persisting metabolic, vascular, and/or neurophysiological disturbance. An additional injury during the vulnerable phase may thus exacerbate the injury development [21–23]. In the experimental, animal setting this window of vulnerability has been clearly demonstrated [24, 25]. In humans, the duration and severity of the vulnerable period has not been established.

In imaging studies, prolonged post injury alteration of the brain functional connectivity network has been demonstrated, even even if the athlete was symptom free and had returned to his/her regular sports activity [26, 27].The significance of this is as yet unknown.

A rare but potentially devastating consequence of an additional mild traumatic brain injury seen in children and adolescents during the period following an SRC is the ‘second impact syndrome’ (SIS). The typical presentation of SIS is sudden death or rapid and catastrophic neurological deterioration following minor head trauma occuring after the athlete had sustained a previous mild head trauma minutes to days earlier. The proposed mechanism is that the second head injury occurs before symptoms from a first head injury have resolved. Although this entity was suggested in the 1970’s [28], the term second impact syndrome was coined in 1984 [29]. The second impact syndrome carries an exceedingly high mortality, ranging from 50–100%, believed to be caused by a distubed vasoreactivity that results in rapid and profound brain swelling without extra- or intracranial space-occupying hematomas. This condition is exceedingly rare, suggested to occur once in «a team of 50 players every 4100 seasons” [30, 31]. The existence of sudden impact syndrome as a disease entity has been questioned [31]. The controversy relates to the rarity of the disorder and the fact that most cases occur after a single impact to the head. A far more common clinical scenario than SIS is where an acute hemispheric brain swelling occurs in conjunction with a thin subdural hematoma [32].

Recovery and return to normal life after SRC

Establishing time course of recovery for SRC

Due to the heterogeneity of SRC severity, it is difficult to accurately assess how long recovery is necessary for the individual patient. Currently, there does not exist any ideal assessment tools for neither symptoms nor clinical/neuropsychological outcomes. Further, health-care providers often end up in difficult positions due to the complexity of symptoms that may or may not be related to the SRC (e.g. post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sleep disorders, anxiety, migraines, attention deficits) as a too early return-to-play may lead to additional injuries and exacerbation of symptoms. One of the reasons for the difficulty to estimate when an athlete is ready to return is that clinical recovery precedes the crucial, but more complex, physiological recovery. Because of this, it is now becoming practice to carefully escalate intensity in training in order to gradually re-introduce the participant before full activity can be recommended in any contact sport. Future research into how (and which) outcome assessments tools should be used, and in which populations, are warranted in multicenter, prospective studies, as of today no ideal objective scoring systems for return-to-play is ready for clinical practice.

Return to sport

Graduated Return to Sport

Return to sports (RTS) following an SRC should follow the previously mentioned graded recovery and rehabilitation strategy, as exemplified in Table 3. After 1–2 days of rest, careful activity, which should be modified depending on symptoms, may be attempted but should have a low bar concerning mental and physical activity (stage 1). Following this period, a majority of the SRC related symptoms while have subsided, and the athlete may gradually increase intensity if he/she remains asymptomatic and meets predefined criteria (e.g. intensity of activity, duration of activity and physiological metrics including pulse etc.). Ideally, these gradual increases should take a week (at minimum) in order to complete the protocol. As they start from when they don’t have any symptoms at rest, each step is approximately 24 hours in the patient continues to improve. However, as both SRC symptoms and individuals are extremely heterogenous, personalized targets and time-frames for RTS are recommended. If an athlete suffers from long-lasting symptoms related to the SRC despite days of inactivity, the different steps should be adjusted. This form of careful exercise-prescription to limit symptoms have been recently reviewed [33] suggesting that if the athlete start experiencing symptoms following escalation, a gradual decrease in intensity should be performed down to asymptomatic levels. Here, the athlete should remain for at least 24 hours, without SRC symptoms, before attempting progression to higher levels.

Table 3.

Graduated Return to Sport Strategy (Adapted from(1))

| Stage | Aim | Activity | Goal of each step |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Symptom-limited activity | Daily activities that do not provoke symptoms. | Gradual reintroduction of work/school activities. |

| 2 | Light aerobic exercise | Walking or stationary cycling at slow to medium pace. No resistance training. | Increase heart rate. |

| 3 | Sport-specific exercise | Running or skating drills. No head impact activities. | Add movement. |

| 4 | Non-contact training drills | Harder training drills, e.g., passing drills. May start progressive resistance training. | Exercise, coordination, and increased thinking. |

| 5 | Full contact practice | Following medical clearance, participate in normal training activities. | Restore confidence and assess functional skills by coaching staff. |

| 6 | Return to sport | Normal game play. |

NOTE: An initial period of 24–48 hours of both relative physical rest and cognitive rest is recommended prior to beginning the Return to Sport progression.

McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J, Aubry M, Bailes J, Broglio S, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport-the 5(th) international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(11):838–47.

The child and adolescent athlete

Many of the SRCs seen today occur in children and adolescents. For these patients, specific measures in management need to be taken into consideration due to the developing brain [34]. The lack of studies in this area (especially among the youngest) warrants further research in order to make more high-quality consensus statements for this particular group.

Current guidelines for these groups refer to athletes <19 years, but these presumably need a higher level of granularity with SRC paradigms for children (5–12 years) and adolescents (13–18 years). However, there are inadequate recommendations for these groups and adult guidelines often apply, which is due to a lack of pediatric SRC research. What has been seen is that the duration of SRC related symptoms exists longer and that a period four weeks of recovery is recommended, though more accurate markers of RTS is warranted. While symptom scores exist, more objective computerized neurophysiological assessment is highly sought after in this age group, in order to study symptoms more relevant to younger athletes. In aggregate, current guidelines are, just like for adult athletes, a period of rest before slowly escalating activity which tries to limit symptoms related to the SRC.

SRC policies should be enforced by schools and teams, including mandatory education on SRC and injury prevention which should be taken by all personnel involved (including teachers, parents, staff and students). Further, following an SRC, personalized teaching (including time away from school if necessary) should be possible for the affected athlete and the follow-up recovery should be monitored by qualified medical professionals. Table 4 exemplifies a gradual return to school for a young athlete.

Table 4.

Graduated Return to School Strategy (Adapted from [1])

| Stage | Aim | Activity | Goal of each step |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Daily activities at home that do not give the child symptoms | Typical activities that the child does during the day as long as they do not increase symptoms (e.g. reading, texting, screen time). Start with 5–15 minutes at a time and gradually build up | Gradual return to typical activities |

| 2 | School activities | Homework, reading or other cognitive activities outside of the classroom. | Increase tolerance to cognitive work. |

| 3 | Return to school part-time | Gradual introduction of schoolwork. May need to start with a partial school day or with increased breaks during the day. | Increase academic activities |

| 4 | Return to school full-time | Gradually progress school activities until a full day can be tolerated | Return to full academic activities and catch up on missed work |

McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport-the 5(th) international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med 2017; 51: 838–47.

As a rule, if a young athlete has not returned to school, he or she should not return to sports. And even when this occurs, a gradual escalation in order to prevent symptoms should be applied.

Treatment of cerebral edema in the neuro-critical care unit in severe TBI

Cerebral edema is one of several devastating pathological entities following TBI. It implies an abnormal accumulation of fluid within the brain parenchyma and is mainly subdivided into vasogenic and cytotoxic [35]. The brain is enclosed within a rigid skull and increased intracranial volume, e.g. growing edema, hemorrhage, brain tumors etc. must be compensated for. The Monro-Kellie doctrine [36] implies that the intracranial volume must stay intact to preserve intracranial pressure (ICP) as an increased volume will lead to insufficient cerebral blood flow (CBF), herniation of brain tissue and a subsequent brain death. There are compensatory mechanisms initiated to maintain adequate intracranial pressure, including decreased production of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and displacement of CSF and especially venous blood from the intracranial cavity. If these mechanisms are sufficient the intracranial pressure (ICP) and the CBF will remain intact, but when the pathological intracranial volume is exceeding these compensatory mechanisms, ICP will increase and CBF will be reduced. In the neuro-critical care unit (NCCU) the aim is to keep the ICP below 20 mmHg which is regarded sufficient as long as mean arterial blood pressure is sufficient to keep an adequate perfusion of the brain. The cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) is calculated by subtracting ICP from mean arterial pressure (MAP), and reflects the pressure of the blood reaching the brain. Depending on the location of the zero-points of ICP and MAP and the patient’s position in the bed, flat down or head elevated, the CPP should typically exceed 50–60 mmHg to maintain sufficient CBF. The normal global CBF is about 50 ml/100g/min [37] and if CBF decreases the brain can partly compensate by increasing its extraction of oxygen from the blood. However, when the global CBF reaches approximately 30 ml/100mg/min, symptoms (e.g. drowsiness) will occur. If CBF is further declined down to around 20 ml/100g/min, the brain starts to prioritize its basal functions and neuronal communication is dampened to prioritize membrane pump functions and the patient becomes unconscious. When the CBF has decreased to 8–12 ml/100g/min the cells suffer from substantial energy crisis and starts to succumb. The aim for neuro-critical care treatment is to maintain a balance between the metabolic demands of the brain and availability of oxygen and metabolites, predominantly glucose.

To maintain this delicate balance, brain edema must be treated. The intracerebral arteries are different from those in other locations in the body. Between the endothelial cells there are tight junction proteins that welds the cells together to control transportation of substances from the blood to the brain parenchyma. Further, above the endothelial cells there is a basement membrane over which there are smooth muscle cells and pericytes surrounded by the astrocytic foot processes. Collectively, this is referred to as the neurovascular unit and constitutes the anatomical blood-brain barrier (BBB). In these astrocytic foot processes, water passes through specific protein “gates”. These gates, called aquaporin 4, are involved in the pathophysiology of brain edema [38]. Following TBI, there is an immediate disintegration of the BBB due to the mechanical forces implied on the brain tissue. This is followed by biochemical disturbances of the BBB by the inflammatory response to trauma, including complement activation. Here, the membrane attack complex (MAC, C5b-9) is assembled and has a role in disintegrating the BBB by attacking endothelial cells in the intracerebral vasculature [39]. Immunoreactivity for tight junction proteins will be reduced in the border zone of cerebral contusions [40] and in humans the CSF/blood quota of albumin (Qalb) will be increased up to a week after TBI [41], indicating vasogenic edema formation. A concomitant energy failure in brain tissue, due to insufficient cerebral circulation, will lead to an inability for the cells to maintain their electrochemical gradients because of insufficient ion pump function. This will lead to an ionic intracellular influx with a subsequent increase in cell osmolality with an intracellular influx of water from the intracerebral extracellular space leading to an osmotic gradient between the extracellular space and the vessels. As this process leads to a disintegration of the BBB, molecules and water will be able to enter the extracellular space [42]. Thus, following TBI, both vasogenic extracellular edema and cytotoxic intracellular edema may co-exist [43].

In animal models, there are many suggested treatments directed at both types of brain edema [42], but in clinical reality, the number of different treatment options are considerably fewer. Primarily, the pathological cause of energy failure such as ischemia must be treated and expansive intracranial hematomas be removed in order to optimize CBF and restore the imbalance between CBF and cerebral metabolism. Targeted edema treatment includes osmotherapy, and if ICP is refractory to maximal therapy, decompressive craniectomy (a surgical procedure where parts of the cranial vault are removed to allow for brain swelling), might be performed. Corticosteroids, with a documented effect on systemic swelling due to vasogenic edema, are regarded non-beneficial, or even harmful, following TBI [44].

The CBF is regulated 1. by the cerebral metabolic rate, 2. chemically by pCO2 and 3. via cerebral autoregulation. Increased metabolic rate increases CBF linearly where body temperature and epileptic seizures are the most common factors contributing to the increased metabolic rate. Hyperventilation in a stressed, non-intubated patient or accidentally in a patient during mechanical ventilation, lead to a vasoconstriction with potential development of cerebral ischemia and a subsequent cytotoxic edema formation. Hypoventilation in an unconscious patient with impaired ventilation leads to a vascular engorgement with a subsequent cerebral hyperemic state, with a potential risk to develop increased vasogenic brain edema. The cerebral autoregulation aims at keeping the global CBF at approximately 50 ml/100g/min irrespective of the blood pressure. An intracerebral vasoconstrictive response is followed increased MAP, and vasodilation will compensate for lower pressures. These three regulatory mechanisms are often disturbed following TBI [45] and it is mandatory to monitor the patients thoroughly to identify the metabolic and cerebrovascular status of each TBI patient.

In the NCCU, three different intracranial monitors are commonly employed, 1. An ICP device aiding treatments aimed to optimize the ICP and enable the brain to maintain adequate cerebral blood flow, 2. Brain tissue oximetry (PBTO2) to monitor oxygen transport to the brain, and 3. intracerebral microdialysis for neurochemical monitoring to enable the assessment of the metabolic state. These monitors are used in conjunction with others evaluating more global measures, such as iterative measurements of oxygen and arteriovenous lactate difference between the jugular bulb and the systemic circulation, continuous EEG monitoring to detect seizures, and protein biomarkers in serum (e.g. S100B [46]) as markers of treatment efficacy.

When an impaired BBB leads to vasogenic edema, excessively high blood pressure must be avoided, but with a subsequent risk for ischemia if the blood pressure is too low. Brain tissue oximetry and microdialysis can guide this treatment by assessing PBTO2 and the lactate/pyruvate ratio (LPR), respectively. A declining PBTO2 and increasing LPR indicates a metabolic crisis that should be treated immediately. By decreasing the cerebral metabolic rate, the need for excessive cerebral blood flow can be reduced, and restore the balance between metabolism and CBF.

Osmotherapy is a treatment directly targeting the brain edema, but there are well-known considerable risks for rebound effects (ICP increases following treatment) [47]. Osmotherapy is mainly instituted in the acute situation to gain time prior to surgery, but may also be used in the NCCU. While previously mannitol was preferably used, hypertonic saline may be associated with less adverse events and a slightly improved ability to decrease ICP [48].

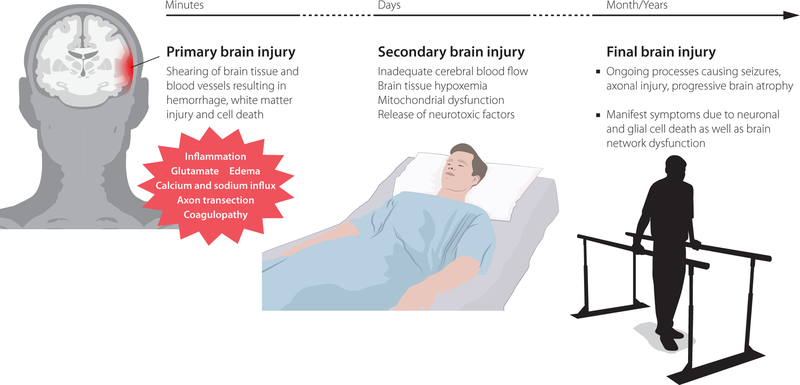

In summary, following severe TBI, both cytotoxic and vasogenic edema caused by BBB damage and metabolic dysfunction, are present causing potentially life-threatening intracranial swelling. There are currently no pharmacological treatment options for brain edema, instead clinical conditions should be optimized by other means, including alleviation of the pathological causes of energy failure such as ischemia or expansive mass lesions, optimizing the CBF and cerebral metabolism as well as administering osmotherapy and (if all other medical interventions fail), decompressive craniectomy. A schematic visualization depicting the progress from injury to potential symptoms is available in Fig 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the processes that occur from brain injury that will result in subsequent symptoms, highlighting the detrimental secondary injury cascade which neuro-critical care is aiming to mitigate.

Interdisciplinary rehabilitation for complex needs after severe traumatic brain injury in adults

Clinical management and rehabilitation of patients with persisting symptoms after mild TBI are addressed earlier in this article. Increasing severity of TBI is usually accompanied by greater severity and complexity of impairments of body structure and function, which contribute to activity limitations and participation restrictions [49]. Some or all of motor, behavioural, emotional, cognitive, language, and primary sensory function (vision, hearing, sensation, smell, taste) may be affected and pain is common. Some patients have co-existing rehabilitation needs and/or rehabilitation restrictions due to considerable extra-cranial injuries after multi-trauma.

The extended time frames for the recovery process, which for patients with the most severe TBI may continue over months or even years [50], and the interaction of subacute medical complications (very common after severe TBI [51, 52]) with rehabilitation possibilities, add further complexity to rehabilitation planning. Doctors and their teams working within the medical speciality of rehabilitation medicine (physiatry in the US, equivalent neurological sub-specialties in some countries) offer specific brain injury knowledge and integration with a wider bio-psycho-social context to promote recovery for patients with complex needs after TBI [53].

Components of brain injury rehabilitation

Rehabilitation is traditionally envisaged by both health care professionals and lay people as involving a therapist working with a patient with the aim of regaining the ability to perform a particular activity; for example, a physiotherapist training walking ability or an occupational therapist providing aids and training to regain the ability to dress. Whilst such therapy is indeed a key component of rehabilitation, The World Health Organisation (WHO) definition of rehabilitation [54] is broader: “Rehabilitation is a set of interventions designed to optimize functioning and reduce disability in individuals with health conditions in interaction with their environment”.

Brain injury rehabilitation promotes recovery through three main approaches:

Complications in the days to months after brain injury are prevented, detected and managed through frequent, specialised medical follow-up. Spontaneous improvement is thus maximised with normalisation of network processes as neuroinflammatory and other acute processes resolve.

Neuroplasticity is promoted by rehabilitation interventions, traditionally therapies such as physiotherapy, speech and language therapy, neuropsychology, and others, leading to restitution of body function.

Compensatory rehabilitation interventions maximise independence and quality of life: for example, a wheelchair may enable independent mobility, aids such as kitchen timers may enable safe home living. Compensatory interventions are particularly relevant for more severe TBI where it may not be medically realistic for function to be completely restored. There is however some theoretical risk that early focus on compensatory interventions may counteract restitution of function.

The evidence base for rehabilitation after TBI is growing [55], and evidence-based guidelines have begun to emerge [56]. There remain however many aspects where evidence is insufficient for detailed rehabilitation planning for the individual patient. A minority of guidelines are specific to TBI [57]; more commonly TBI is included under the umbrella term “acquired brain injury”.

Newer rehabilitation approaches

Recent research has begun to expand the range of interventions promoting neuroplasticity beyond traditional rehabilitation with a therapist. Neuromodulation, pharmacotherapy and new technologies are attractive techniques where current evidence regarding efficacy is as yet largely insufficient to support incorporation into routine clinical practice.

The rehabilitation evidence base is somewhat more advanced for stroke rehabilitation than for rehabilitation after severe TBI. Despite important pathophysiological differences there are some similarities between severe impairments after stroke and after TBI; stroke patients have also suffered sudden onset brain injury to a previously normally developed brain and may have similar activity and participation restrictions. Findings from the stroke literature may at least suggest interesting hypotheses and treatment strategies for further evaluation in patients with TBI. Clinical rehabilitation services for more complex needs are often organised for acquired brain injury rather than specifically for TBI, an organisational factor likely to contribute to difficulties in developing TBI-specific rehabilitation.

Studies of neuromodulation with transcranial magnetic stimulation or direct current stimulation are promising but are still at a relatively early stage [58], lagging behind the stroke literature [59]. It is likely to be some years before sufficiently robust studies are available for TBI-specific evidence-based clinical recommendations.

Pharmacological interventions promoting neuroplasticity are of intense current interest for stroke patients. The exploitation of previously underrecognized effects of drugs developed for other purposes (as such having well defined safety profiles and many years of experience of clinical usage) is attractive. One example is identification of positive effects of Fluoxetine on motor recovery in non-depressed patients after ischaemic stroke [60], with current studies extending recruitment to also include haemorrhagic stroke [61]. It is unclear whether similar clinical benefits occur after TBI; several of the putative mechanisms are certainly relevant after TBI and the simplicity of such an intervention is attractive [61].

An equally important but understudied element regarding pharmacological influences on neuroplasticity, is the potential negative effects of medications commonly used to manage symptoms during sub-acute recovery after moderate to severe TBI. One example is the use of typical neuroleptics such as Haloperidol using post-traumatic agitation, despite animal studies suggesting negative effects on neuroplasticity [62]. Actual clinical impact in the short and long term is largely unknown. Organisational aspects contribute to perpetuating an inadequate research base; during the important sub-acute period many patients have left the neurosurgical unit but often do not have immediate access to inpatient rehabilitation due to waiting times, stringent rehabilitation admission criteria requiring medical stability, or insurance issues. As such it is often clinicians who are not specialists in brain injury rehabilitation who must manage sub-acute symptoms and complications on busy general medical or surgical wards. Recent studies show a negative association between increasing time between discharge from intensive care and admission to rehabilitation with outcome not explained by initial injury severity [63], and better outcomes for patients receiving rehabilitation in a continuous chain initiated in the intensive care unit [64].

There is growing interest in technology in rehabilitation, either as an aid to more traditional rehabilitation promoting gain in function, particularly exoskeletons for motor function [65], or as a potentially powerful form of compensatory aid. The research base is however still in its infancy: whilst motor deficits can have a major impact on function for some individuals surviving severe TBI, these patients are relatively few in number. National and international collaborations will be needed to improve the evidence base.

Assessing rehabilitation needs

A prerequisite for adequate rehabilitation is adequate assessment. Neuroimaging findings and rehabilitation needs are only loosely correlated. Standard neurological examination is not primarily focused on describing rehabilitation needs, rather on contributing to the process of differential diagnosis according to a framework such as ICD-10. However, patients with the same ICD-10 diagnosis often have very different rehabilitation needs, and an assessment based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) is instead recommended [49]. A complicating factor after severe TBI is that the patient’s insight into his/her deficits is often affected, such that overreliance on patients’ reported symptoms risks missing important aspects that may be amenable to rehabilitation. With more severe injuries, the very complexity of deficits may make isolated assessment by any one profession (e.g. neuropsychologist, physiotherapist, speech and language therapist) potentially inaccurate – see case example

A system also needs to be in place to allow for repeated qualified assessment reflecting the dynamic process of recovery and changes in rehabilitation needs over time: for example, a patient who several weeks after TBI cannot participate actively in rehabilitation may risk being discharged to community services without specialist rehabilitation follow up and thus without access to interdisciplinary rehabilitation a few weeks later when s/he may have regained to ability to participate actively.

Whilst the ICF research section Core Sets have gone some way to highlighting common difficulties after TBI [66], there lacks international consensus on how to triage patients to different levels of rehabilitation assessment to allow identification of an appropriate rehabilitation service for the individual.

In conclusion, co-ordinated interdisciplinary rehabilitation promotes recovery after severe TBI [55]. The challenge in the coming years is to create health care systems promoting timely access to appropriate rehabilitation for those patients who need it. Exciting new rehabilitation methods are emerging including non-invasive neurostimulation, new technologies and new uses of existing drugs; the next challenge is to perform sufficiently large and methodologically robust trials to provide the evidence that is needed to launch these into routine clinical practice. A summary of rehabilitation aspects in moderate and severe TBI is available in Table 5.

Table 5.

Bullet points on rehabilitation in moderate to severe traumatic brain injury

| Assess | Impairments |

|---|---|

| Activity and participation restrictions | |

| Understand | Social and environmental context |

| Patient priorities regarding rehabilitation | |

| Plan rehabilitation interventions to… | Minimize complications (appropriate medical follow up by professional with expertise in brain injury) |

| Restore function (utilize neuroplasticity; may include physiotherapy, speech and language therapy, neuropsychological rehabilitation, amongst others) | |

| Compensate for function that cannot be restored (occupational therapy) | |

| Adopt appropriate rehabilitation form and intensity considering individual patient needs (monodisciplinary, multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary) | |

| Follow up the effect of rehabilitation and any persisting disability | Reassess |

| Adjust rehab plan | |

| Consider return to work interventions |

Cognitive Rehabilitation

Cognitive rehabilitation (CR) refers to interventions used to compensate for or resolve cognitive impairments and reduce disability [67]. This generic therapy is a heterogeneous array of treatments without a unified theoretical framework which are performed in various settings, including more recently web-based interventions. The goals of CR also include improving quality of life [68]. It is important to distinguish CR from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) which is designed to challenge and mitigate maladaptive thoughts and beliefs of an individual to effect behavioral change [67]. CBT is used to treat depression and other emotional conditions following concussion; CR and CBT can be employed concurrently or sequentially by different therapists or in some cases by the same therapist.

CR is more commonly indicated to treat the sequelae of moderate to severe traumatic brain injury, but repetitive concussion or mild TBI (mTBI) may result in persistent cognitive problems in a subgroup of patients. Although transient cognitive dysfunction (e.g., poor concentration, memory problem) during the first 2 to 4 weeks after a sports related concussion is common and can persist for 3 months after non-sports mTBI, these effects resolve in most athletes (and non-athletes) without CR. However, the clinical management of concussion includes evaluation of cognition and monitoring the clinical course over the first 2 to 4 weeks in sports concussion and by a follow-up visit in non-sports mTBI. Prescribing gradual return to studies and occupational duties that involve intensive concentration and time pressure is often recommended by clinicians to mitigate development of secondary anxiety, depression, and even aggravation of post-concussion symptoms.

CR is recommended in patients with persistent cognitive impairment; this may be restorative as in learning strategies to enhance goal management and cognitive efficiency in everyday activities [69]. Goal management training (GMT) involves strategies in problem solving, prioritizing goals, and inhibiting attention to less relevant, distracting information [69]. A recent review of clinical trials of GMT concluded that there is support for the effectiveness of this intervention with small to moderate effect sizes and some evidence for maintenance of gains at follow-up [69]. Limitations in the existing clinical trials for CR interventions include small sample size, lack of evidence in some studies for generalization of positive effects across situations, and some of the CR interventions also lack support for maintenance of the gains over time.

Compensatory cognitive interventions include learning to use a smart phone for reminders of appointments and to maintain lists of contacts and other information that is important in everyday activities. Telephone apps could also be used to enhance generalization of therapies such as GMT. Many patients may benefit from a combination of restorative and compensatory interventions; some interventions incorporate elements of both of these categories of treatment.

Emerging approaches to CR include the addition of neuromodulation by transient direct cortical stimulation (tDCS) or transient magnetic stimulation (TMS). The latter is used to treat depression as well, but entails a risk of seizures which is a concern especially after moderate to severe TBI [70]. Neuromodulation is thought to enhance neuroplasticity and purportedly facilitate training-related reorganization of brain networks. Pharmacologic treatment in combination with CR is infrequently used to treat sports related concussion or non-sports mTBI. However, medications such as methylphenidate have received support in clinical trials to treat attention disturbance after moderate to severe TBI [71].

The neural mechanisms underpinning CR are not well understood. In contrast to lateralized cognitive and language deficits after stroke, disturbance of memory and attention after concussion is attributed to network dysfunction involving multiple brain regions. Acquiring resting state functional MRI to measure functional connectivity of the default mode network (DMN) has shown dysfunction in athletes recovering from concussion [72]. The DMN and related networks are implicated in shifting between attention to tasks and self-referential mental activity; dysfunction may mediate difficulty in concentration following concussion. It is plausible that CR may facilitate recovery of DMN functioning.

In summary, CR consists of an array of restorative and compensatory techniques which are useful in treating persistent cognitive deficit after concussion or mTBI, but are more routinely employed following more severe TBI. CR is an evolving therapy which would benefit from more rigorous clinical trials. The format of CR may change as new technologies are used in combination with established techniques. Table 6 provides a summary of CR following TBI.

Table 6.

Cognitive Rehabilitation (CR) for Sports and Non-Sports TBI

| 1. CR is indicated for moderate to severe TBI, beginning when the patient is oriented and has reached a relatively stable baseline. |

| 2. For mTBI, CR is indicated for persistent cognitive deficits, defined by a duration > 4 weeks after sports related concussion and >3 months after non-sports mTBI. |

| 3. CR techniques include those that are restorative (e.g., retraining attention) and others which are compensatory (e.g., smart phone apps for reminders) |

| 4. Goal Management Training (GMT) is a promising treatment for executive function deficits typically identified after moderate to severe TBI. |

| 5. Combining CR with neuromodulation or pharmacologic treatment which enhance neuroplasticity may be effective, but further research is needed. |

| 6. Limitations in the CR literature include lack of data to support generalization of effects across situations and maintenance over time. |

Abbreviations: mTBI = mild traumatic brain injury, CR = cognitive rehabilitation, TBI = traumatic brain injury.

A graphical overview of the moments from injury to rehabilitation is provided in Fig 2.

Figure 2.

Overview of sideline assessments of a sports-related concussion, treatment of more severe brain injuries and highlights of neuro-rehabilitation.

Conclusions

The consequences of TBI, independent of severity, may be long lasting and result in varying degrees of permanent disability. SRCs are of increasing concern as a mild TBI, and management steps must be initiated at time of impact by rapid assessment at the sideline, as well as at later stages following the injury to reduce the risk for deterioration and to optimize recovery. For those that suffer from severe TBI, improvements in neuro-critical care monitoring allow for the detection of numerous factors exacerbating the injury, and aid in refining management. Following the initial post-injury phase, rehabilitation is essential in order to facilitate recovery. New methods of cognitive rehabilitation may play an important role, although future and more structured trials are warranted to evaluate their effect.

Case example – interdisciplinary rehabilitation assessment of complex need.

A 20-year-old student who underwent ICP-monitoring for a sports-related TBI (extensive contusions with left hemisphere dominance) 6 months previously attends the neurosurgical clinic for follow-up. He has been unable to return to his studies and is inactive at home. No neurosurgical complications are found. He is referred for rehabilitation assessment

Version 1: assessments by single therapists

He is referred to a neuropsychologist for assessment due to concern about possible cognitive deficits and behavioural issues, and separately to a physiotherapist due to mild right sided hemiparesis. The neuropsychologist however has difficulty administering several planned cognitive tests due to the patient’s hemiparesis affecting function in the dominant hand (writing), and also notes that the patient complains of uncontrolled pain in the same arm – it has not been possible to discontinue treatment with morphine initiated for headache immediately after the TBI. Speech problems are also noted, but a detailed evaluation of these lies outside the neuropsychologist’s expertise. The neuropsychologist notes that current morphine treatment may be affecting cognition and precludes firm conclusions about TBI-related cognitive impairments. A program of therapy targeting negative behaviours is given, but with little effect. The physiotherapy program also has little effect – the patient fails to turn up on many occasions and when he does come is reluctant to participate in therapy due to pain.

Version 2: assessment by an interdisciplinary rehabilitation team (physician, physiotherapist, speech and language therapist, neuropsychologist, occupational therapist):

The patient attends a coordinated team assessment over a period of a week, during which the team can have contact with each other, culminating in interdisciplinary discussion of findings and creation of a rehabilitation plan. A speech and language therapist characterizes a mild aphasia, considered to contribute to communication difficulties and frustration. The rehabilitation physician and physiotherapist note allodynia, neuropathic pain, and spasticity. Medications are adjusted to target neuropathic pain, eventually allowing cessation of morphine therapy. Treatment with botulinum toxin combined with physiotherapy contribute to improved hand function. Intensive speech therapy is provided, with improvement in aphasia. Assessment of cognition is complemented after these initial interventions, by the neuropsychologist in dialogue with a speech and language therapist, identifying executive difficulties that improve with strategy training. The rehabilitation team identify early that the patient has incomplete insight into his difficulties, and work continuously with the patient regarding this through the assessment and rehabilitation process. After intensive out-patient rehabilitation and co-ordination with the patient’s college, he returns to his studies with support 9 months after injury.

Acknowledgements

NM is supported by Swedish Brain Foundation and the Swedish Research Council under the framework of EU-ERA-NET NEURON CnsAFlame. HL is supported by NIH grants R21NS086714Department (PIs: H. Levin, S. Ott, P. Dash), PT13078 DOD (PI: G. Manley), and PT13078 DOD (PI: E. Wilde). PM is supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP1141609; APP1127007). EPT is supported by grants from Swedish Society for Medical Research.

The funding sources had no role in the design of this study or during its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results.

Eric P Thelin organized the Old Servant’s Brain Injury Symposium at the Karolinska Institutet and received honorarium from Journal of Internal Medicine/”Stiftelsen för Gamla Tjänarinnor” for this.

Niklas Marklund and Eric P Thelin has received financial support in order to prepare this manuscript from Journal of Internal Medicine.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Paul McCrory is a co-investigator on competitive grants relating to mild TBI funded by several governmental and other organizations. He is employed under a Fellowship awarded by the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia and is based at the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health. He has a clinical consulting practice in neurology, including medico-legal work. He has been reimbursed by the government, professional scientific bodies, and commercial organizations for discussing or presenting research relating to MTBI and sport-related concussion at meetings, scientific conferences, and symposiums. He has not directly received any research funding, or monies other than travel reimbursements from the AFL, FIFA or the NFL and does not hold any individual shares in or receive monies from any company related to concussion or brain injury assessment or technology. He acknowledges unrestricted philanthropic support from CogState Inc. (2001–16).

All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport-the 5(th) international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med 2017; 51: 838–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dougan BK, Horswill MS, Geffen GM. Athletes’ Age, Sex, and Years of Education Moderate the Acute Neuropsychological Impact of Sports-Related Concussion: A Meta-analysis. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2013: 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Iverson GL, Gardner AJ, Terry DP, Ponsford JL, Sills AK, Broshek DK, Solomon GS. Predictors of clinical recovery from concussion: a systematic review. British journal of sports medicine 2017; 51: 941–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker JG, Leddy JJ, Darling SR, Shucard J, Makdissi M, Willer BS. Gender Differences in Recovery From Sports-Related Concussion in Adolescents. Clinical pediatrics 2016; 55: 771–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfaller AY, Nelson LD, Apps JN, Walter KD, McCrea MA. Frequency and Outcomes of a Symptom-Free Waiting Period After Sport-Related Concussion. The American journal of sports medicine 2016; 44: 2941–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham P, Saumet JL, Chevalier JM. External Iliac Artery Endofibriosis in Athletes. Sports medicine (Auckland, NZ 1997; 24: 221–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merritt VC, Rabinowitz AR, Arnett PA. Injury-related predictors of symptom severity following sports-related concussion. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2015; 37: 265–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCrory P, Feddermann-Demont N, Dvorak J, et al. What is the definition of sports-related concussion: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2017; 51: 877–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patricios J, Fuller GW, Ellenbogen R, et al. What are the critical elements of sideline screening that can be used to establish the diagnosis of concussion? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2017; 51: 888–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis GA, Ellenbogen RG, Bailes J, et al. The Berlin International Consensus Meeting on Concussion in Sport. Neurosurgery 2018; 82: 232–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meaney DF, Smith DH. Biomechanics of concussion. Clin Sports Med 2011; 30: 19–31, vii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feddermann-Demont N, Echemendia RJ, Schneider KJ, et al. What domains of clinical function should be assessed after sport-related concussion? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2017; 51: 903–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yengo-Kahn AM, Hale AT, Zalneraitis BH, Zuckerman SL, Sills AK, Solomon GS. The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool: a systematic review. Neurosurg Focus 2016; 40: E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Echemendia RJ, Meeuwisse W, McCrory P, et al. The Concussion Recognition Tool 5th Edition (CRT5): Background and rationale. Br J Sports Med 2017; 51: 870–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sussman ES, Ho AL, Pendharkar AV, Ghajar J. Clinical evaluation of concussion: the evolving role of oculomotor assessments. Neurosurg Focus 2016; 40: E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rizzo JR, Hudson TE, Dai W, et al. Rapid number naming in chronic concussion: eye movements in the King-Devick test. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2016; 3: 801–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aubry M, Cantu R, Dvorak J, et al. Summary and agreement statement of the 1st International Symposium on Concussion in Sport, Vienna 2001. Clin J Sport Med 2002; 12: 6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider KJ, Leddy JJ, Guskiewicz KM, et al. Rest and treatment/rehabilitation following sport-related concussion: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2017; 51: 930–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nordstrom A, Nordstrom P, Ekstrand J. Sports-related concussion increases the risk of subsequent injury by about 50% in elite male football players. British journal of sports medicine 2014; 48: 1447–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cross M, Kemp S, Smith A, Trewartha G, Stokes K. Professional Rugby Union players have a 60% greater risk of time loss injury after concussion: a 2-season prospective study of clinical outcomes. British journal of sports medicine 2016; 50: 926–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terwilliger VK, Pratson L, Vaughan CG, Gioia GA. Additional Post-Concussion Impact Exposure May Affect Recovery in Adolescent Athletes. J Neurotrauma 2016; 33: 761–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manville J, Laurer HL, Steudel WI, Mautes AE. Changes in cortical and subcortical energy metabolism after repetitive and single controlled cortical impact injury in the mouse. J Mol Neurosci 2007; 31: 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shitaka Y, Tran HT, Bennett RE, Sanchez L, Levy MA, Dikranian K, Brody DL. Repetitive closed-skull traumatic brain injury in mice causes persistent multifocal axonal injury and microglial reactivity. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology 2011; 70: 551–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longhi L, Saatman KE, Fujimoto S, et al. Temporal window of vulnerability to repetitive experimental concussive brain injury. Neurosurgery 2005; 56: 364–74; discussion −74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laurer HL, Bareyre FM, Lee VM, et al. Mild head injury increasing the brain’s vulnerability to a second concussive impact. J Neurosurg 2001; 95: 859–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newsome MR, Li X, Lin X, et al. Functional Connectivity Is Altered in Concussed Adolescent Athletes Despite Medical Clearance to Return to Play: A Preliminary Report. Front Neurol 2016; 7: 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Broglio SP, Macciocchi SN, Ferrara MS. Neurocognitive performance of concussed athletes when symptom free. J Athl Train 2007; 42: 504–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider RC. Head and Neck Injuries in Football: Mechanisms, Treatment, and Prevention Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saunders RL, Harbaugh RE. The second impact in catastrophic contact-sports head trauma. JAMA 1984; 252: 538–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hebert O, Schlueter K, Hornsby M, Van Gorder S, Snodgrass S, Cook C. The diagnostic credibility of second impact syndrome: A systematic literature review. J Sci Med Sport 2016; 19: 789–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCrory PR, Berkovic SF. Second impact syndrome. Neurology 1998; 50: 677–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mori T, Katayama Y, Kawamata T. Acute hemispheric swelling associated with thin subdural hematomas: pathophysiology of repetitive head injury in sports. Acta neurochirurgica 2006; 96: 40–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makdissi M, Schneider KJ, Feddermann-Demont N, et al. Approach to investigation and treatment of persistent symptoms following sport-related concussion: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2017; 51: 958–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis GA, Anderson V, Babl FE, et al. What is the difference in concussion management in children as compared with adults? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2017; 51: 949–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marmarou A A review of progress in understanding the pathophysiology and treatment of brain edema. Neurosurgical focus 2007; 22: E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mokri B The Monro-Kellie hypothesis: applications in CSF volume depletion. Neurology 2001; 56: 1746–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lassen NA, Astrup J. Cerebral blood flow: Normal regulations and ischemic tresholds. In: Philip R Weistein AIF, ed, Protection of the brain from ischemia Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1990; 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zador Z, Bloch O, Yao X, Manley GT. Aquaporins: role in cerebral edema and brain water balance. Progress in brain research 2007; 161: 185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stahel PF, Morganti-Kossmann C, Perez D, Redaelli C, Gloor B, Trentz O, Kossmann T. Intrathecal levels of complement-derivied soluble membrane attack complex (sC5b-9) correlate with blood-brain barrier dysfunction in patients with traumatic brain injury. Journal of neurotrauma 2001; 18: 773–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bellander BM, von Holst H, Fredman P, Svensson M. Activation of the complement cascade and increase of clusterin in the brain following a cortical contusion in the adult rat. J Neurosurg 1996; 85: 468–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bellander BM, Olafsson IH, Ghatan PH, Bro Skejo HP, Hansson LO, Wanecek M, Svensson MA. Secondary insults following traumatic brain injury enhance complement activation in the human brain and release of the tissue damage marker S100B. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2011; 153: 90–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winkler EA, Minter D, Yue JK, Manley GT. Cerebral Edema in Traumatic Brain Injury: Pathophysiology and Prospective Therapeutic Targets. Neurosurgery clinics of North America 2016; 27: 473–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bullock R, Statham P, Patterson J, Wyper D, Hadley D, Teasdale E. The time course of vasogenic oedema after focal human head injury--evidence from SPECT mapping of blood brain barrier defects. Acta neurochirurgica Supplementum 1990; 51: 286–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roberts I, Yates D, Sandercock P, et al. Effect of intravenous corticosteroids on death within 14 days in 10008 adults with clinically significant head injury (MRC CRASH trial): randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 364: 1321–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee JH, Kelly DF, Oertel M, et al. Carbon dioxide reactivity, pressure autoregulation, and metabolic suppression reactivity after head injury: a transcranial Doppler study. J Neurosurg 2001; 95: 222–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thelin EP, Nelson DW, Bellander BM. Secondary peaks of S100B in serum relate to subsequent radiological pathology in traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit Care 2014; 20: 217–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muizelaar JP, Wei EP, Kontos HA, Becker DP. Mannitol causes compensatory cerebral vasoconstriction and vasodilation in response to blood viscosity changes. Journal of neurosurgery 1983; 59: 822–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gu J, Huang H, Huang Y, Sun H, Xu H. Hypertonic saline or mannitol for treating elevated intracranial pressure in traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurosurg Rev 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), World Health Organisation.

- 50.Whyte J, Nakase-Richardson R, Hammond FM, et al. Functional outcomes in traumatic disorders of consciousness: 5-year outcomes from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 94: 1855–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Godbolt AK, Stenberg M, Jakobsson J, Sorjonen K, Krakau K, Stalnacke BM, Nygren DeBoussard C. Subacute complications during recovery from severe traumatic brain injury: frequency and associations with outcome. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e007208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whyte J, Nordenbo AM, Kalmar K, et al. Medical complications during inpatient rehabilitation among patients with traumatic disorders of consciousness. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 94: 1877–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine, Core Standards for Major Trauma. 2015.

- 54.Organization WH. Rehabilitation in health systems Geneva: World Health Organization. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turner-Stokes L, Pick A, Nair A, Disler PB, Wade DT. Multi-disciplinary rehabilitation for acquired brain injury in adults of working age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015: CD004170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Network SIG. Brain Injury Rehabilitation in adults 2013.

- 57.Jolliffe L, Lannin NA, Cadilhac DA, Hoffmann T. Systematic review of clinical practice guidelines to identify recommendations for rehabilitation after stroke and other acquired brain injuries. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e018791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Clayton E, Kinley-Cooper SK, Weber RA, Adkins DL. Brain stimulation: Neuromodulation as a potential treatment for motor recovery following traumatic brain injury. Brain Res 2016; 1640: 130–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Brien AT, Bertolucci F, Torrealba-Acosta G, Huerta R, Fregni F, Thibaut A. Non-invasive brain stimulation for fine motor improvement after stroke: a meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol 2018; 25: 1017–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chollet F, Tardy J, Albucher JF, et al. Fluoxetine for motor recovery after acute ischaemic stroke (FLAME): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2011; 10: 123–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mead G, Hackett ML, Lundstrom E, Murray V, Hankey GJ, Dennis M. The FOCUS, AFFINITY and EFFECTS trials studying the effect(s) of fluoxetine in patients with a recent stroke: a study protocol for three multicentre randomised controlled trials. Trials 2015; 16: 369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nasrallah HA, Chen AT. Multiple neurotoxic effects of haloperidol resulting in neuronal death. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2017; 29: 195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Godbolt AK, Stenberg M, Lindgren M, et al. Associations between care pathways and outcome 1 year after severe traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2015; 30: E41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Andelic N, Bautz-Holter E, Ronning P, et al. Does an early onset and continuous chain of rehabilitation improve the long-term functional outcome of patients with severe traumatic brain injury? J Neurotrauma 2012; 29: 66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Resquin F, Gonzalez-Vargas J, Ibanez J, et al. Adaptive hybrid robotic system for rehabilitation of reaching movement after a brain injury: a usability study. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2017; 14: 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.ICF Core sets for traumatic brain injury.

- 67.Graham R, Rivara FP, Ford MA, Spicer CM. SPORTS-RELATED CONCUSSIONS IN YOUTH Improving the Science, Changing the Culture 2014. [PubMed]

- 68.Cicerone KD, Dahlberg C, Kalmar K, et al. Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: recommendations for clinical practice. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 81: 1596–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stamenova V, Levine B. Effectiveness of goal management training(R) in improving executive functions: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2018: 1–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Bikson M, Brunoni AR, Charvet LE, et al. Rigor and reproducibility in research with transcranial electrical stimulation: An NIMH-sponsored workshop. Brain Stimul 2018; 11: 465–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McDonald BC, Flashman LA, Arciniegas DB, et al. Methylphenidate and Memory and Attention Adaptation Training for Persistent Cognitive Symptoms after Traumatic Brain Injury: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017; 42: 1766–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chamard E, Lichtenstein JD. A systematic review of neuroimaging findings in children and adolescents with sports-related concussion. Brain Inj 2018; 32: 816–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]