Abstract

We used two national surveys (2010: N=1,597; 2013: N=1,057) of people who inject drugs (PWID) in past-month to assess the prevalence and population size of PWID with either safe or unsafe injection and sex behaviors, overall and by HIV status. In 2013, only 27.0% (vs. 32.3% in 2010) had safe injection and sex, 24.6% (vs. 23.3% in 2010) had unsafe injection and sex, 26.4% (vs. 26.5% in 2010) had only unsafe injection, and 22.0% (vs. 18.0% in 2010) had unsafe sex only. Among HIV-positive PWID in 2013, only 22.1% (~2200 persons) had safe injection and sex,14.2% (~1,400 persons) had unsafe injection and sex, 53.1% (~5200 persons) had unsafe injection, and 10.6% had unsafe sex (~1,100 persons). Among HIV-negative PWID in 2013, only 27.5% (~22,200 persons) had safe injection and sex, 25.9% (~20,900 PWID) had unsafe injection and sex, 23.2% (~18,700 persons) had unsafe injection, and 23.3% (~18,800 persons) had unsafe sex. HIV-positive and -negative PWID in Iran continue to be at risk of HIV acquisition or transmission which calls for targeted preventions services.

Keywords: people who inject drugs, unsafe injection, unsafe sex, HIV, Iran

Introduction

Globally, people who inject drugs (PWID) are at a disproportionate risk of HIV acquisition or transmission due to risky injection or unsafe sex behaviors [1]. PWID in Iran bear the highest prevalence of HIV among all at-risk populations in Iran (15.2% in 2010 [2]), the highest prevalence that was reported for any subpopulation in Iran and has not been changed significantly [3]. There are about 208,000 PWID living in Iran [4] and most of the reported HIV cases (67.2%) are likely to be infected through unsafe injection drug use [3].

According to the 2010 and 2013 bio-behavioral surveillance survey (BBSS) among PWID in Iran, the patterns of injection and risky behaviors have changed over time. 48.3% of the participants in the 2013 round of PWID national survey in Iran reported having injected drugs in the previous month compared to 61.6% in the 2010 round. However, the prevalence of unsafe sex (i.e., sex without using a condom) with either a paying partner or a non-paying partner increased to 60.5% and 68.7%, respectively since 2010. Also, shared injection in past-month increased from 22.1% in 2010 to 46.4% in 2013 [3]. Among sexually active participants in PWID 2013, only 21.8% (26.1% male vs. 7.1% female) reported consistent condom use in past-month [4]. The ongoing risky injection and sexual behaviors of PWID is correlated with the unchanged high prevalence of HIV among PWID in Iran.

The dual risk of unsafe injection and unsafe sex has not been assessed systemically. Most of the studies have just examined sharing of syringes or needles [5], others only assessed effectiveness of safe sex interventions (condom use or distribution) [6, 7], and very few looked at paraphernalia-sharing [8]. Likewise, for risky sexual behaviors, many studies have limited the condomless sex evaluation to female sex workers or men who have sex with men [9–11]. In the current literature, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to get a comprehensive picture of frequency of both dual and single risky behaviors among PWID [12].

To address this gap, we used the data collected in two national surveys of PWID in the 2010 and 2013 in Iran. In each survey, we combined answers to several questions on recent risky injection and sex behaviors to make a four-category outcome variable for dual and either safe or unsafe injection and sex behaviors in the overall study population and by subgroups including HIV status. We also estimated the population size of PWID in each of the subgroups by HIV status. Finally, we compared the results to the results from survey 2010 to assess the changes over time.

Methods

Sampling

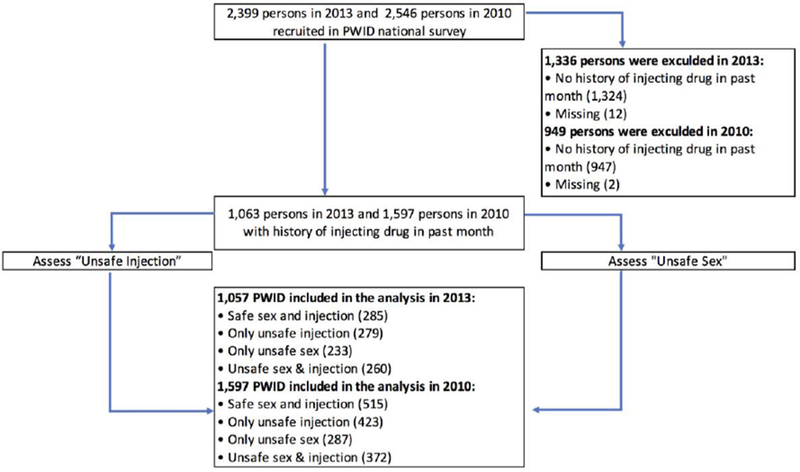

In the BBSS 2010 and 2013, we recruited 2,546 and 2,399 PWID, respectively. PWID were recruited from drop-in centers, shelters, Opium Maintenance Treatment (OMT) centers, voluntary counseling and testing centers, and outreached spots. For these two studies, eligible participants were 18 years of age and self-reported drug injection at least once during the past 12 months. In this analysis, we selected only those participants who reported a history of drug injection in the past month (Figure 1). After obtaining verbal informed consent, trained interviewers collected behavioral data using a standardized behavioral questionnaire. Consenting participants were then tested for HIV by two rapid tests (SD and Unigold). Those tested positive in both rapid tests were considered as HIV positive. Participants received monetary incentive for both the interview (about US$2.5) and HIV testing (about US$0.5) in both surveys. Research Ethics Board based at the Kerman University of Medical Sciences reviewed and approved the study protocol and procedures (Reference number: K/93/205).

Figure 1.

Participant inclusion flowchart. PWID: People who inject drugs

Study variables

We used data from several questions to derive a four-category outcome variable. Unsafe injection was defined as injecting drugs using a used needle/syringe or sharing a syringe or other equipment for injecting drugs. We did not consider reusing of self-used needles, syringes or injection equipment as unsafe injection as these behaviors do no attribute to HIV acquisition and transmission. Unsafe sex was defined as having unprotected sexual contact with any partner (i.e., spouse, male or female paid or unpaid partner) during the past 12 months. Those who had no sexual partners in the past 12 months were grouped as the safe sex category. Consequently, a four-category outcome was defined as, those with both unsafe drug injection and unsafe sexual contacts were categorized as “unsafe injection and sex” (UI&S), those with only unsafe injection behaviors were categorized as “only unsafe injection” , those with only unsafe sex behaviors were categorized as “only unsafe sex”, and those with no unsafe injection and no unsafe sex were categorized as “safe sex and injection ” (SI&S).

Statistical analyses

We used Stata survey command to measure the point prevalence and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) for each of the outcome categories overall and in PWID subgroups. Based on 2013 BBSS, it was estimated that 208,000 people in Iran had inject drugs in previous year [4]. In our study, we found that 43.3% (1039 out of 2399 in 2013 BBSS) reported injection in past month. Using this proportion and the prevalence of HIV, we estimated the total number of PWID with 95% uncertainty interval (UI) in each of the four categories of the outcome. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas USA).

Results

Our analytical sample included 1597 PWID (in 2010) and 1057 PWID (in 2013) with past-month injection (Figure 1). Only 0.5% (12 out of 2399) had missing data for past month injection and another 2.3% (24 out of 1063) had missing data for injection and sexual behaviors in the 2013 BBSS; No one in survey 2010 had missing data for similar questions.

In both surveys (Table 1), most participants were male, had low education, had a history of incarceration, and more than half had started injection drug use before the age of 18 years. In compare with the participants in 2010, fewer participants in the 2013 survey were younger than 30 years old (22.4% vs. 42.5%), married (17.5% vs. 27.4%), injected drugs for less than 10 years (53.7% vs. 72.7%), used opioids (23.2% vs. 76.6%); however, more PWID in the 2013 survey used opioids and stimulants simultaneously (70.2% vs. 13.4%). More participants in the 2013 survey were on opioids substitution therapy (34.1% vs. 24.1%), reported sexually transmitted diseases (STD) symptoms (8.1% vs. 3.8%) than those in the 2010 survey. HIV prevalence was lower in the 2013 survey (10.9% vs. 15.5%). The demographic characteristics of participants in all four subgroups of unsafe injection and sex in both surveys are presented in Table S1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in the two national surveys of people who injected drugs in the past month, Iran.

| Characteristics | PWID survey 2013 | PWID survey 2010 |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Male | 1,039 (98.3) | 1,568 (98.2) |

| Age (≤30 years old) | 237 (22.4) | 678 (42.5) |

| Low education (lower than high-school) | 737 (69.8) | 1,144 (71.8) |

| No secure income | 351 (33.6) | 607 (39.2) |

| Currently married (including temporary marriage) | 185 (17.5) | 438 (27.4) |

| Prison history (ever) | 883 (83.6) | 1,271 (79.9) |

| Age at first drug use (≤18 years old) | 580 (54.9) | 896 (56.1) |

| Drug injection duration (≤10 years) | 562 (53.7) | 1137 (72.7) |

| Substance type in past month * | ||

| Only opioids | 220 (23.2) | 1,180 (76.6) |

| Only stimulants | 63 (6.6) | 153 (9.9) |

| Opioids and stimulants | 666 (70.2) | 207 (13.4) |

| Currently on opioids substitute therapy | 306 (34.1) | 250 (24.1) |

| STD symptom in past year | 83 (8.1) | 60 (3.8) |

| HIV positive | 113 (10.9) | 233 (15.5) |

| Geographic areas ** | ||

| North | 359 (34.0) | 446 (27.9) |

| East | 193 (18.26) | 316 (19.8) |

| West | 404 (38.2) | 498 (31.2) |

| South | 101 (9.6) | 337 (21.1) |

Type of Drug (both injected or non-injected): Stimulant= Shishe, Hashish/grass/Cannabis, Marijuana, Ecstasy, Cocaine, and methamphetamine/crystal

Opioids=Opium, Opium sap, Opium syrup, Heroin, Norchizak, Tamchizak, Buprenorphine, Methadone, and Krack

Geographic areas: East=Kerman, Zahedan, and Mashhad, North=Tehran, and Sari, West=Kermanshah, Tabriz, and Lorestan, South=Shiraz, Ahvaz

if they are currently, under treatment with methadone, buprenorphine or sharbate taryak

In the 2013 survey, 24.6% of participants had both unsafe injection & sex, 22.0% had unsafe sex only, 26.4% had unsafe injection only and 27.0% had both safe injection and sex (Table 2). In comparison with male PWID, female PWID reported higher frequencies of unsafe injection (44.4% vs. 26.1) but fewer frequencies of unsafe sex (11.1% vs. 22.2% for only unsafe sex, and 16.7% vs. 24.7% for UI&S). Moreover, in compare with older PWID, a higher number of young PWID (≤30 years old) had unsafe sex only (26.2% vs. 20.9%) and both unsafe injection and sex (31.2% vs. 22.7%). More than 80% of PWID who were married had only unsafe sex or UI&S (40.5% + 43.2% = 83.7%). And 42.0% of PWID who had ever injected in prisons reported UI&S. The highest prevalence of UI&S was reported by those who injected only stimulant only (44.9%) or both opioids and stimulant (33.7%) in the past month. The prevalence of UI&S in those reported STD symptoms in past year was 55.4%. The prevalence of UI&S in the 2010 survey is reported in Table S2. In 2010, 23.3% of participants had UI&S, 18.0% had only unsafe sex, 26.5% had only unsafe injection and 32.3% had SI&S.

Table 2.

The prevalence of unsafe injection and sex in overall and by subgroups of people who inject drugs in the past month, Iran, 2013

| Characteristics | Categories | Safe injection & sex (SI&S) | Only unsafe injection | Only unsafe sex | Unsafe injection & sex (UI&S) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (CI 95%) | % (CI 95%) | % (CI 95%) | % (CI 95%) | ||

| Total | 27.0 (22.1, 32.5) | 26.4(20.5, 33.3) | 22.0(17.5, 27.5) | 24.6(19.5, 30.5) | |

| Gender | Male | 27.0(22.1,32.5) | 26.1(20.0,33.2) | 22.2(17.6,27.7) | 24.7(19.6,30.7) |

| Female | 27.8(12.4,51.2) | 44.4(24.6,66.2) | 11.1(2.6,36.9) | 16.7(8.4,30.5) | |

| Age | >30 years old | 28.4(23.0,34.6) | 28.1(21.8,35.3) | 20.9(15.3,27.7) | 22.7(18.0,28.2) |

| ≤30 years old | 21.9(17.2,27.6) | 20.7(14.7,28.3) | 26.2(21.2,31.8) | 31.2(23.2,40.6) | |

| Education | High school and higher | 28.8(19.4,40.6) | 24.1(17.5,32.3) | 23.2(16.3,31.9) | 23.8(15.7,34.4) |

| Guidance and lower | 26.1(21.3,31.4) | 27.4(21.5,34.2) | 21.6(16.2,28.2) | 25.0(20.8,29.6) | |

| Any secure income | Yes | 33.1(28.5,38.0) | 27.1(22.3,32.4) | 20.8(15.5,27.3) | 19.1(14.3,25.1) |

| No | 24.1(18.2,31.2) | 26.0(18.6,35.0) | 22.8(17.7,28.9) | 27.1(20.3,35.3) | |

| Currently married (including temporary marriage) | Yes | 8.7(3.2,21.2) | 7.6(4.5,12.4) | 43.2(37.1,49.7) | 40.5(30.6,51.4) |

| No | 30.9(26.8,35.3) | 30.3(24.7,36.6) | 17.6(13.7,22.2) | 21.2(17.9,25.0) | |

| Prison history (ever) | Yes | 28.2(23.8,33.0) | 27.9(22.3,34.2) | 20.3(15.6,25.9) | 23.7(19.5,28.4) |

| No | 20.8(11.4,34.8) | 19.1(12.0,28.9) | 31.2(25.2,37.9) | 28.9(17.2,44.3) | |

| Injection in prison (ever) | Yes | 17.0(11.2,25.0) | 31.1(21.4,42.9) | 9.9(7.1,13.7) | 42.0(30.7,54.2) |

| No | 31.9(27.6,36.6) | 26.6(21.8,32.1) | 23.5(18.1,29.8) | 18.0(14.8,21.8) | |

| Age at first drug use | >18 years | 26.4(19.4,34.8) | 27.0(19.2,36.7) | 21.4(16.2,27.6) | 25.2(16.1,37.1) |

| ≤18 years | 27.4(22.4,33.1) | 25.9(20.7,31.9) | 22.6(17.8,28.2) | 24.1(20.8,27.9) | |

| Drug injection duration | >10 years | 26.7(21.3,32.7) | 31.6(24.8,39.3) | 20.7(14.8,28.0) | 21.1(16.4,26.7) |

| ≤10 years | 27.6(21.5,34.7) | 22.2(16.8,28.8) | 23.0(18.4,28.2) | 27.2(20.9,34.7) | |

| Type of drugs injected in past month * | Only opioids | 28.9(23.7,34.7) | 26.5(20.0,34.3) | 22.9(17.4,29.3) | 21.7(16.7,27.8) |

| Only stimulant | 32.7(16.1,55.1) | 6.1(1.5,21.7) | 16.3(10.6,24.4) | 44.9(25.0,66.5) | |

| Opioids and Stimulant | 16.6(12.3,22.0) | 30.2(22.4,39.3) | 19.5(11.7,30.7) | 33.7(27.3,40.8) | |

| Currently on opioids substitute therapy | Yes | 23.2(14.2,35.6) | 20.6(16.5,25.4) | 26.1(21.6,31.2) | 30.1(19.8,42.9) |

| No | 28.1(22.1,35.0) | 25.4(19.7,32.0) | 23.0(17.3,30.0) | 23.5(19.2,28.5) | |

| STD symptom in past year | Yes | 7.2(3.0,16.6) | 20.5(13.5,29.8) | 16.9(8.3,31.2) | 55.4(42.9,67.3) |

| No | 28.8(23.5,34.8) | 26.3(19.6,34.2) | 22.7(18.3,28.0) | 22.2(16.3,29.4) | |

Type of Drug: Stimulant= Shishe, Hashish/grass/Cannabis, Marijuana, Ecstasy, Cocaine, and methamphetamine/crystal

opioids=Opium, Opium sap, Opium syrup, Heroin, Norchizak, Tamchizak, Buprenorphine, Methadone, and Crack

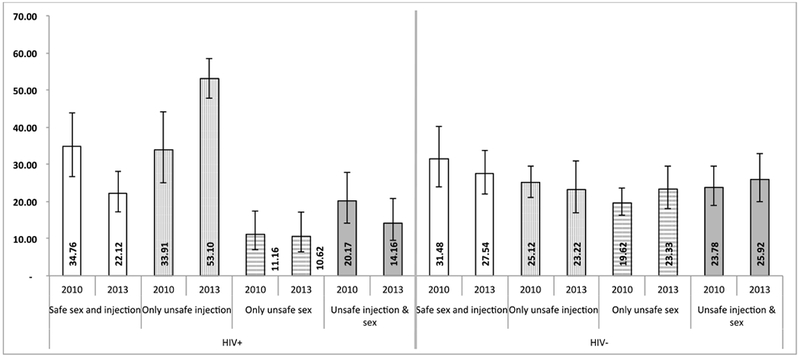

Between 2010 and 2013, among HIV-positive PWID, the prevalence of only unsafe injection increased (33.9% vs 53.1%); in contrast, SI&S prevalence decreased (34.8% vs. 22.1%). Among HIV-negative PWID, no significant changes were observed regarding the four risk categories between 2010 and 2013 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The prevalence of recent UI&S among HIV positive and negative people who inject drug in past-month, Iran, in 2010 and 2013

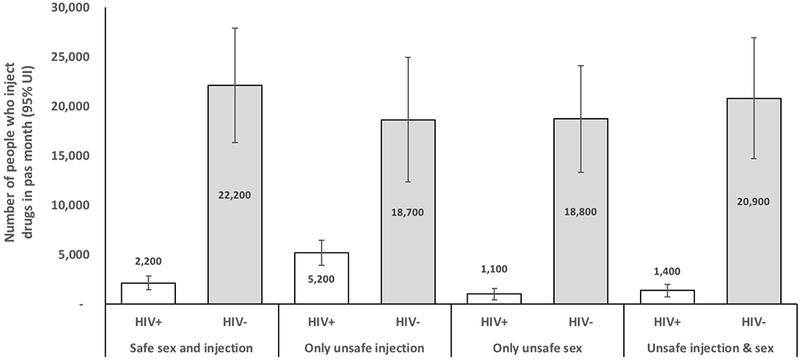

In the 2013 survey, only 22.1% of HIV-positive PWID had SI&S; 53.1% (~ 5,200 PWID, UI 95%: 3,926-6,464 in Iran) had only unsafe injection, 10.6% had only unsafe sex (~ 1,100 PWID, UI 95%: 465-1,616) and 14.2% (~ 1400 PWID, UI 95%: 749-2,024) had UI&S (Table 3 and Figure 3). Only 27.5% of HIV-negative PWID had SI&S; 23.2% (~ 18,700 PWID, UI 95%: 12,371- 24,964) had only unsafe injection, 23.3% (~ 18800 PWID, UI 95%: 13,371-24,135) had only unsafe sex and 25.9% (~ 20900 PWID, UI 95%: 14,733,26,937) had UI&S.

Table 3.

The prevalence of unsafe injection and sex by geographic areas and HIV status of people who inject drugs in the past month, Iran, 2013

| Characteristics | Categories | Safe injection & sex (SI&S) | Only unsafe injection | Only unsafe sex | Unsafe injection & sex (UI&S) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (CI95%) | % (CI95%) | % (CI95%) | % (CI95%) | ||

| Geographic areas** | North | 22.6(13.2,35.9) | 22.0(12.8,35.2) | 20.9(13.5,30.8) | 34.5(23.1,48.1) |

| East | 37.3(26.6,49.4) | 8.8(5.0,15.1) | 39.4(29.1,50.7) | 14.5(10.1,20.5) | |

| West | 24.5(19.6,30.2) | 40.4(34.4,46.6) | 13.6(10.7,17.2) | 21.5(18.0,25.5) | |

| South | 32.7(24.1,42.7) | 19.8(10.0,35.4) | 26.7(15.5,42.1) | 20.8(13.0,31.6) | |

| HIV test result | Positive | 22.1(17.2,28.0) | 53.1(47.73,58.40) | 10.6(6.4,17.1) | 14.2(9.5,20.7) |

| Negative | 27.5(22.0,33.9) | 23.2(16.9,31.0) | 23.3(18.1,29.6) | 25.9(19.9,33.0) | |

| HIV positive by four geographic areas | North | 32.3(22.0,44.6) | 41.9(29.0,56.1) | 19.4(6.5,45.3) | 6.5(2.5,15.6) |

| East | 66.7(41.4,85.0) | 16.7(2.8,58.6) | 16.7(2.8,58.6) | 0.0 | |

| West | 10.3(4.5,21.7) | 66.2(55.4,75.5) | 4.4(1.6,11.4) | 19.1(11.7,29.7) | |

| South | 50.0(32.4,67.6) | 12.5(1.2,63.3) | 25.0(12.5,43.8) | 12.5(3.4,36.6) | |

| HIV negative by four geographic areas | North | 21.1(11.1,36.6) | 20.5(11.5,34.0) | 20.8(12.6,32.5) | 37.5(25.8,50.9) |

| East | 37.0(25.6,50.1) | 7.7(4.3,13.6) | 40.3(29.3,52.4) | 14.9(10.1,21.4) | |

| West | 27.4(21.7,34.0) | 35.1(28.1,42.9) | 15.5(11.7,20.2) | 22.0(18.1,26.5) | |

| South | 31.5(22.4,42.4) | 19.6(9.2,36.8) | 27.2(15.1,44.0) | 21.7(13.1,33.9) | |

Geographic area: East=Kerman, Zahedan, and Mashhad, North=Tehran, and Sari, West=Kermanshah, Tabriz, and Lorestan, South=Shiraz, Ahvaz

Figure 3.

The estimated number of HIV positive and negative people who inject drug in past-month with recent UI&S, Iran, 2013

In the 2013 survey, the highest prevalence of UI&S (34.5%) was observed for the North of Iran (Table 3). In East, more than one third (39.4%) had only unsafe sex. The range of SI&S prevalence was from 22.6% in the North to 37.3 in the East. In the West, only 10.3% of HIV positive PWID had SI&S, while 66.2% had only unsafe injection and another 19.1% had UI&S. Majority of HIV positive PWID in the East (66.7%) and half of them in the South (50.0%) had SI&S. Only 21.1% of HIV negative PWID in the North and 27.4% of them in the West reported safe injection and sexual behaviors. The prevalence of UI&S by geographic areas and HIV status in the 2010 survey is presented in Table S3.

On average, PWID with unsafe sex had a greater number of sex partners (Table 4). On average, 5 to 11 people was evolved during episodes of shared injection in prisons and 43.6% of PWID in only unsafe injection subgroup had group injection (on average, with 5 other PWID) in the past month. Also, 59.5% of PWID in UI&S subgroup had group injection in the past month (on average, with 4 other PWID). Between 53.7% (in SI&S) and 66.3% (in only unsafe injection) of PWID in all subgroups had daily injections. Also, 12.1% (9.0%+3.1%) of PWID in UI&S subgroup had receptive sharing at most or all injections episodes they had in the past month. Bleaching or washing was a common practice in those who had unsafe injection in the past month.

Table 4.

Injection and sexual behaviors of people who inject drugs in past month by subgroups of unsafe injection or sex, Iran, 2013

| Sexual or injection behaviors | Categories | Safe injection & sex (SI&S) | Only unsafe injection | Only unsafe sex | Unsafe injection & sex (UI&S) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (CI95%) | Mean (CI95%) | Mean (CI95%) | Mean (CI95%) | ||

| Average number of sexual partners in past year | Unpaid partner | 3 (2, 3) | 2 (1, 2) | 8 (3, 12) | 4 (2, 5) |

| Paid partner | 2 (2, 2) | 2 (2, 3) | 6 (2, 10) | 4 (2, 6) | |

| Male partner* | 2 (0, 3) | 0 | 3 (1, 6) | 2 (1, 3) | |

| Lifetime duration in prison (in year) | 3.6 (2.8, 4.4) | 4.3 (3.8, 4.9) | 3.8 (3.4, 4.2) | 3.8 (3.0, 4.6) | |

| Average number of injecting partners in last shared injection episode in a prison** | 5 (2, 8) | 11 (6, 17) | 6 (2, 10) | 7 (4, 10) | |

| Duration of drug injection (in year) | 10.9 (9.9, 12.0) | 12.7 (11.5, 13.9) | 10.6 (9.8, 11.3) | 10.4 (9.2, 11.6) | |

| Group injection in past month (%) | 1.8 (0.7,4.2) | 43.6(38.0,49.5) | 3.4(2.0,5.8) | 59.5(42.8,74.2) | |

| Average number of PWID in a group injection | 2 (1, 3) | 5 (3, 8) | 2 (1, 3) | 4 (2, 7) | |

| Daily injection (%) | 53.7(45.33,61.83) | 66.3(60.6,71.6) | 56.2(42.7,68.9) | 56.6(41.6,70.6) | |

| Frequency of receptive sharing of needle or syringe in past month (%) | Never | 100 | 57.2(49.7,64.4) | 100 | 51.2(43.7,58.6) |

| Sometimes | 0 | 36.7(30.2,43.7) | 0 | 33.6(27.7,40.1) | |

| Often | 0 | 2.2(0.8,6.0) | 0 | 3.1(1.8,5.5) | |

| Most of the times | 0 | 2.2(0.9,5.1) | 0 | 9.0(6.9,11.7) | |

| Always | 0 | 1.8(0.6,5.5) | 0 | 3.1(1.1,8.7) | |

| Frequency of bleaching/washing in past month (%)*** | Never | 100 | 8.3(4.4,15.3) | 100 | 9.7(5.7,15.9) |

| Seldom | 0 | 10.0(5.7,17.0) | 0 | 17.0(7.5,34.0) | |

| Sometimes | 0 | 45.8(36.3,55.7) | 0 | 38.7(31.6,46.3) | |

| Most of the times | 0 | 15.8(9.0,26.5) | 0 | 12.9(9.2,17.9) | |

| Always | 0 | 20.0(14.9,26.4) | 0 | 21.8(14.1,32.0) | |

only calculated for male participants.

only for those with history of prison.

only in those reported receptive sharing in past month.

N/A: not applicable

Discussion

Our findings showed that the majority of PWID in Iran had practiced unsafe injection or sex; more than one in four had dual unsafe injection and unsafe sexual risks for HIV. Only one in five HIV-positive PWID had practiced safe injection and sex and were therefore less likely to transmit HIV infection to their sexual or injecting partners; the rest (~ 7,700 HIV-positive PWID) continued to transmit HIV infection. Moreover, less than one third of HIV-negative PWID had practiced safe injection and sex and were therefore at low risk of HIV acquisition; the rest (~ 58,400 HIV-negative PWID) were at risk of HIV acquisition through unsafe injection or sex or both. In comparison with 2010, more PWID in the 2013 survey reported unsafe injection — particularly among those who were HIV positive. We also observed a change in drug use patterns shifting from opioid use to poly-drug (i.e., opioids and stimulant). Unsafe injection in the 2013 survey was more frequent among female PWID. Married PWID were five times more likely to report unsafe sex with or without unsafe injection.

Our estimates for dual sex and injection risks among PWID were significantly higher than the findings of previous studies in Iran (i.e., 36.9% past month unsafe injection [2], 38.3% condom use in last sex [13]). This difference could be attributed to our use of a parallel approach in defining risky practices where answers to many questions about injection and sexual behaviors are used to define unsafe sex and/or injection risks [14]. This novel approach would result in a more sensitive and accurate assessment of the risk and has been previously used in defining ‘higher risk’ categories of PWID at risk of acquiring or transmitting HCV in Australia [15].

We found that many HIV-positive PWID continued to practice unsafe injection or sexual behaviors. As less than one-third of people living with HIV in Iran are aware of their HIV status [2, 16] and only half of PWID (49.8%) had ever tested for HIV [17], it is likely that most participants did not know their HIV status. Indeed, consistent with an international body of evidence [19], a recent study of PWID in Kermanshah, Iran [18] reported awareness of HIV status to be significantly and negatively associated with lending used needles and syringes to injecting partners (OR 0.22). Scaling up HIV testing among PWID in Iran is critical not only to diagnose and link them to life-saving antiretroviral therapy [20], but also to motivate them to have safer sexual and injection practices [18]. Increased access to HIV testing could also help facilitate moving towards ‘treatment as prevention’ which has been shown to be a successful strategy in even resource-limited settings [19][21, 22]. Consistent with the previous studies among PWID in Iran [2, 25], recent unsafe sex or injection among HIV-negative PWID were frequent. This is particularly concerning given that PWID bear the highest burden of HIV in Iran [23] and injection drug use continues to be the major driver of the HIV epidemic in the country [24]. While Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is not available in Iran and its acceptability among PWID requires further assessments [28], studies from other settings have highlighted its effectiveness in preventing new HIV infections among PWID [26, 27].

We also observed that certain demographic characteristics (e.g., being married or younger) were associated with increased odds of unsafe sexual and injection drug use practices. Previous studies have shown HIV prevalence among both injecting and non-injecting partners of male PWID in Iran to be as high as 7.7% [29]. Trusting the partner [30–32] and focusing on family planning not on STD/HIV prevention [33, 34] were reported as the main reasons for not using condoms in marital relationships. Furthermore, younger PWID, those who used stimulants, had recent STD symptoms or had history of injection in prison were more likely to have dual unsafe injection and sex risks; findings that are consistent with that of previous studies elsewhere due to their links with unsafe sexual practices [35][36, 37]. Moreover, our study highlighted a potential trend towards poly-drug use among PWID in Iran. Possible reasons for this shift are individual desires to tackle over-sedation resulting from opioids, low perceived risk, novelty and sensation seeking, and perception that stimulant can eventually help with quitting opioids [38]. Also, the social stigma for stimulant drug use seems to be less than opioids use in Iran [38–40]. With the recent shift from using opioids to stimulants in Iran [41, 42], and its association with frequency of unsafe sex [41], scaling up programs to address the harms associated with stimulant use is warranted.

While our study was not powered enough to detect potential gender differences among PWID, we found female PWID to have a risker injection profile than their male counterparts. Higher HIV incidence [43] and risky behaviors (e.g., syringe and equipment sharing) among female PWID have been previously reported [44–46]. These observations could be attributed to female PWID’s greater experiences of stigmatization and difficulties in accessing harm reduction services such as needle/syringe and substance use treatment programs [47]. Female PWID may also be very dependent on their male injecting partners for purchasing, preparing, and injecting illicit drugs which may lead to higher rates of sharing syringes and unsafe injection [48].

Unsafe injection behavior overall and in particular in HIV positive PWID increased since 2010. Both PWID and health providers need to be sensitized again for the potential harms associated with unsafe injection, with the focus on the West of Iran where both HIV prevalence and risk behaviors are the highest among PWID in the country [2, 25].

Our findings had three main limitations. We recruited our study participants using a facility-based and outreach sampling approach in ten major cities in Iran which limits the generalizability of findings to all PWID in Iran. Moreover, we did not ask PWID about their self-reported HIV status so we were not able to assess whether HIV status awareness was associated with risky behaviors. Lastly, similar to studies of this nature elsewhere, our findings are prone to social desirability and underreporting biases.

While bearing the limitations of our study in mind, our study assessed the dual injection and sexual behaviors of PWID and estimated the number of PWID who were at risk of HIV acquisition or transmission. The decrease in the prevalence of safe injections among PWID is concerning. Both PWID and healthcare providers need to be re-sensitized to the potential harms associated with unsafe injection. Our findings suggest that majority of HIV positive and HIV negative PWID continue to transmit or being at risk of contracting HIV. Prevention programs targeted both groups need to be evaluated and effectively scaled up to reduce HIV transmission among this marginalized population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment:

We would like to acknowledge supervisors and field staff from all collaborative universities who provided inputs to the study design and methods, assisted in data collection and implementation of the survey. Our gratitude also goes to the PWID who participated in the survey.

Funding: The study was funded by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria through UNDP Iran, and by Ministry of Iran. For this paper, we also received support from the University of California, San Francisco’s International Traineeships in AIDS Prevention Studies (ITAPS), U.S. NIMH, R25MH064712.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References:

- 1.Kim NJ, et al. , Trends in sources and sharing of needles among people who inject drugs, San Francisco, 2005-2012. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(12):1238–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khajehkazemi R, et al. , HIV prevalence and risk behaviours among people who inject drugs in Iran: the 2010 National Surveillance Survey. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89 Suppl 3:iii29–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National AIDS Committee Secretariat. Islamic Republic of Iran AIDS Progress Report (http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/IRN_narrative_report_2015.pdf). In: office HS, editor. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikfarjam A, et al. , National population size estimation of illicit drug users through the network scale-up method in 2013 in Iran. Int J Drug Policy, 2016. 31:147–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malta M, et al. , HIV prevalence among female sex workers, drug users and men who have sex with men in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez LM, et al. , Behavioral interventions for improving condom use for dual protection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(10):CD010662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malekinejad M, et al. , Effectiveness of community-based condom distribution interventions to prevent HIV in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0180718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thiede H, et al. , Prevalence and correlates of indirect sharing practices among young adult injection drug users in five U.S. cities. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91 Suppl 1:S39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbst JH, et al. , A meta-analytic review of HIV behavioral interventions for reducing sexual risk behavior of men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39(2):228–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Q, et al. , [Prevalence of HIV infection and syphilis, sexual behaviors and awareness of HIV/AIDS related knowledge among men who have sex with men in China: a Meta-analysis of data collected from 2010 to 2013]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2015;36(11):1297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chow EP, et al. , Behavioral Interventions Improve Condom Use and HIV Testing Uptake Among Female Sex Workers in China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 2015. 29(8):454–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Copenhaver MM, et al. , Behavioral HIV risk reduction among people who inject drugs: meta-analytic evidence of efficacy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31(2):163–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amin-Esmaeili M, et al. , Profile of People Who Inject Drugs in Tehran, Iran. Acta Med Iran. 2016;54(12):793–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arruda MM, et al. , Sensitivity and specificity of parallel or serial serological testing for detection of canine Leishmania infection. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2016;111(3):168–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treloar C, Wilson H, and Mao L, Deconstructing injecting risk of hepatitis C virus transmission: Using strategic positioning to understand “higher risk” practices. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy. 2016;23(6):457–461. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ministry of Health and Medical Education. AIDS Progress Report on Monitoring of the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV and AIDS (https://goo.gl/7xeeVZ). Tehran: National AIDS Committee Secretariat, Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Islamic Republic of Iran;March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shokoohi M, et al. , Low HIV testing rate and its correlates among men who inject drugs in Iran. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;32:64–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noroozi A, et al. , Impact of HIV Status Notification on Risk Behaviors among Men Who Inject Drugs in Kermanshah, West of Iran. J Res Health Sci. 2016;16(3):116–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy CE, et al. , Behavioural interventions for HIV positive prevention in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(8):615–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radfar SR, et al. , Behaviors Influencing Human Immunodeficiency Virus Transmission in the Context of Positive Prevention among People Living with HIV/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome in Iran: A Qualitative Study. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5(8):976–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radfar SR, Nematollahi P, and Arasteh M, Factors Influencing Access and Use of Care and Treatment Services among Iranian People Living with HIV and AIDS: A Qualitative Study. Iran J Public Health. 2016;45(1):109–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mgbere O, et al. , System and Patient Barriers to Care among People Living with HIV/AIDS in Houston/Harris County, Texas: HIV Medical Care Providers’ Perspectives. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14(6):505–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahimi-Movaghar A, et al. , HIV prevalence amongst injecting drug users in Iran: a systematic review of studies conducted during the decade 1998–2007. Int J Drug Policy. 2012;23(4):271–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nasirian M, et al. , Modeling of human immunodeficiency virus modes of transmission in Iran. J Res Health Sci. 2012;12(2):81–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noroozi M, et al. , Injecting and Sexual Networks and Sociodemographic Factors and Dual HIV Risk among People Who Inject Drugs: A Cross-sectional Study in Kermanshah Province, Iran. Addict Health. 2016;8(3):186–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernard CL, et al. , Estimation of the cost-effectiveness of HIV prevention portfolios for people who inject drugs in the United States: A model-based analysis. PLoS Med. 2017;14(5):e1002312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fu R, Owens DK, and Brandeau ML, Cost-effectiveness of alternative strategies for provision of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for people who inject drugs. AIDS. 2018;32(5):663–672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guise A, Albers ER, and Strathdee SA, ‘PrEP is not ready for our community, and our community is not ready for PrEP’: pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV for people who inject drugs and limits to the HIV prevention response. Addiction. 2017;112(4):572–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alipour A, et al. , HIV prevalence and related risk behaviours among female partners of male injecting drugs users in Iran: results of a bio-behavioural survey, 2010. Sex Transm Infect, 2013. 89 Suppl 3:iii41–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandali S, Norms and practices within marriage which shape gender roles, HIV/AIDS risk and risk reduction strategies in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique. AIDS Care. 2011;23(9):1171–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mtenga SM, et al. , ‘It is not expected for married couples’: a qualitative study on challenges to safer sex communication among polygamous and monogamous partners in southeastern Tanzania. Glob Health Action. 2016;9:323–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinchoff J, et al. , Why don’t urban youth in Zambia use condoms? The influence of gender and marriage on non-use of male condoms among young adults. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0172062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maia C, Guilhem D, and Freitas D, [Vulnerability to HIV/AIDS in married heterosexual people or people in a common-law marriage]. Rev Saude Publica. 2008;42(2):242–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raymond E and Trussell J, Condom use within marriage: a neglected HIV intervention. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(3):239;author reply 239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wand H, et al. , Individual and population level impacts of illicit drug use, sexual risk behaviours on sexually transmitted infections among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: results from the GOANNA survey. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoenigl M, et al. , Clear Links Between Starting Methamphetamine and Increasing Sexual Risk Behavior: A Cohort Study Among Men Who Have Sex With Men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71(5):551–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shoptaw S. and Reback CJ, Methamphetamine use and infectious disease-related behaviors in men who have sex with men: implications for interventions. Addiction. 2007;102 Suppl 1:130–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noroozi A, Malekinejad M, and Rahimi-Movaghar A, Factors Influencing Transition to Shisheh (Methamphetamine) among Young People Who Use Drugs in Tehran: A Qualitative Study. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2018;50(3):214–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rahimi-Movaghar A, et al. , Use of stimulant substances among university students in tehran: a qualitative study. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2011;5(2):32–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fallah G, et al. , Stimulant use in medical students and residents requires more careful attention. Caspian J Intern Med, 2018. 9(1):87–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alam-Mehrjerdi Z and Abdollahi M, The Persian methamphetamine use in methadone treatment in Iran: implication for prevention and treatment in an upper-middle income country. Daru. 2015;23:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shariatirad S, Maarefvand M, and Ekhtiari H, Methamphetamine use and methadone maintenance treatment: an emerging problem in the drug addiction treatment network in Iran. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24(6):e115–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hurtado Navarro I, et al. , Differences between women and men in serial HIV prevalence and incidence trends. Eur J Epidemiol. 2008;23(6):435–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Viitanen P, et al. , Hepatitis A, B, C and HIV infections among Finnish female prisoners--young females a risk group. J Infect. 2011;62(1):59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tracy D, et al. , Higher risk of incident hepatitis C virus among young women who inject drugs compared with young men in association with sexual relationships: a prospective analysis from the UFO Study cohort. BMJ Open. 2014;4(5):e004988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montgomery SB, et al. , Gender differences in HIV risk behaviors among young injectors and their social network members. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28(3):453–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Des Jarlais DC, et al. , Are females who inject drugs at higher risk for HIV infection than males who inject drugs: an international systematic review of high seroprevalence areas. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;124(1-2):95–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jin H, et al. , Differences in HIV risk behaviors among people who inject drugs by gender and sexual orientation, San Francisco, 2012. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:180–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.