Abstract

Extending proteomics to smaller samples can enable the mapping of protein expression across tissues with high spatial resolution and can reveal sub-group heterogeneity. However, despite the continually improving sensitivity of LC-MS instrumentation, in-depth profiling of samples containing low-nanogram amounts of protein has remained challenging due to analyte losses incurred during preparation and analysis. To address this, we recently developed nanoPOTS (Nanodroplet Processing in One pot for Trace Samples), a robotic/microfluidic platform that generates ready-to-analyze peptides from cellular material in ~200 nL droplets with greatly reduced sample losses. In combination with ultrasensitive LC-MS, nanoPOTS has enabled >3,000 proteins to be confidently identified from as few as 10 cultured human cells and ~700 proteins from single cells. However, the nanoPOTS platform requires a highly skilled operator and a costly in-house-built robotic nanopipetting instrument. In this work, we sought to evaluate the extent to which the benefits of nanodroplet processing could be preserved when upscaling reagent dispensing volumes by a factor of 10 to those addressable by commercial micropipette. We characterized the resulting platform, termed Microdroplet Processing in One pot for Trace Samples (μPOTS), for the analysis of as few as ~25 cultured HeLa cells (4 ng total protein) or 50 μm square mouse liver tissue thin sections and found that ~1800 and ~1200 unique proteins were respectively identified with high reproducibility. The reduced equipment requirements should facilitate broad dissemination of nanoproteomics workflows by obviating the need for a capital-intensive custom liquid handling system.

Keywords: Proteomics, small sample, microfluidics, thin tissue sections

Introduction

Interrogation of the proteome reveals information closely related to subtle cell states that may not be directly reflected in pre-translational omics. Even in the post-genomic era when transcriptomic information can be acquired with rapidly increasing efficiency and accuracy, proteome profiling is still essential to provide systematic inspection of the expression levels that better correlate with specific cell states and biological phenotypes [1]. Typically, proteomics analysis requires that samples contain micrograms of protein or the equivalent of >104 cells [2], a number large enough to allow multiple transcriptomically distinct sub-groups to reside that are masked by the ensemble results [3, 4]. In addition, for the examination of rare cells, e.g., circulating tumor cells (CTC) [5, 6], in which a very small number of cells of interest are available per collection, low sample input becomes an intrinsic requirement. Alternative proteomic methods such as flow cytometry (FC) and mass cytometry (MC) [7] can achieve single-cell sampling resolution, but the proteins that can be interrogated are restricted by limited availability of high-quality antibodies and the multiplexing capabilities of the methods, which are usually limited to <40 species. MALDI imaging [8, 9] provides sampling resolution as low as 20–50 μm for tissue samples, but the multiplexing capability is usually modest due to a lack of effective pre-MS separation [10]. To directly map the complexity of proteomes with higher sampling resolution, a workflow that combines the deep profiling capability of LC-MS but consumes much smaller biological samples with minimal loss of proteome coverage is critically needed.

Recent advances in LC-MS instrumentation have reduced the detection limits for tryptic peptides to ~10 zmol [11–15], a level at which many proteins are expressed within single somatic mammalian cells. However, extending deep proteome profiling to low numbers of somatic cells remains challenging. The gap between the sample input threshold and LC-MS ultra-sensitivity results from the inefficient recovery of proteins/peptides during the preparation of cellular samples, which mainly results from sample losses due to multi-phase peptide/protein purification and removal of LC-MS-incompatible detergents [16, 17], as well as non-specific adsorption to vial walls during sample transfer [18, 19]. Attempts to increase recovery have focused on improved sample preparation methods including LC-MS-compatible detergents [20–22] or detergent-free methods [15, 23] for cell lysis and protein extraction, simplified operations using integrated procedures and devices [15, 24–26], and online sample preparation methods [23, 27, 28]. Proteome profiling of single Xenopus laevis embryonic cells at early developmental stages has been reported using filter aided sample preparation (FASP) wherein ~1000 proteins were identified from ~1 μg of non-yolk protein per cell [29]. By combining adaptive focused acoustics-based cell lysis with porous layer open tube LC (10 μm i.d.), ~1300 proteins were identified from a protein digest aliquot corresponding to 50 MCF-7 cells [15]. Recent advances in sample preparation from fixed tissue allows for ~1000–1500 proteins to be identified using either hydrogel-based digestion [30] or liquid microjunction extraction [31] at a spatial resolution of <1 mm.

We recently developed nanoPOTS (Nanodroplet Processing in One pot for Trace Samples) [32], a robotically-addressed microfluidic platform that reduces total sample preparation volumes to ~200 nL within sessile droplets, greatly minimizing sample losses and enhancing enzymatic digestion efficiency due to increased substrate concentrations. In combination with nanoLC-MS, nanoPOTS has enabled >3,000 proteins to be identified from as few as ~10 HeLa cells with robust label-free quantification, as well as reproducible proteome profiling of thin sections of single pancreatic islets. More recently, fluorescence-activated cell sorting was interfaced with nanoPOTS to sort and analyze single HeLa and primary lung cells, with nearly 700 proteins being identified per HeLa cell [33]. The extension of in-depth proteome profiling to low numbers of somatic cells, however, has required a costly in-house-built robotic nano-pipetting instrument and associated expertise, which could limit dissemination of the platform to the broader research community.

To make the method accessible as a more conventional benchtop workflow, we explored the possibility of processing samples in small droplets using the same general nanoPOTS strategy but increasing the droplet volume to the low-microliter level (μPOTS). All liquid handling could be achieved using a commercially available laboratory micropipette with no additional infrastructure or required instrument training. We demonstrated that μPOTS enabled the identification of ~1800 protein groups from as few as ~25 HeLa cells containing ~4 ng total protein. We further combined μPOTS with laser capture microdissection (LCM), wherein mouse liver tissue sections were directly catapulted into the nanowells for μPOTS processing. From 10-μm-thick tissue sections as small as 50 μm per side (~10 mouse liver cells), a spatial resolution comparable to advanced MALDI-imaging systems,[34] ~1200 protein groups were reproducibly identified, demonstrating the enabling potential of μPOTS for physiologically relevant samples. These results indicate that μPOTS can provide in-depth proteome coverage for low-nanogram samples while greatly increasing accessibility and decreasing instrumentation requirements.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and chemicals

Dithiothreitol (DTT) and iodoacetamide (IAA) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) were freshly prepared in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (ABC) buffer. n-Dodecyl β-D-maltoside (DDM) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in 50 mM ABC buffer with a concentration of 1% (w/w), aliquoted, and stored at −20°C until use. MS-grade trypsin and Lys-C were products of Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Other unmentioned reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Deionized water (18.2 MΩ) was purified using a Barnstead Nanopure Infinity system (Los Angeles, CA, USA).

Chip fabrication

Chip fabrication followed our previously reported protocols [32], except that the microfabricated wells in the array were designed with larger dimensions to accommodate microliter volumes. In brief, a 3 × 16 array of spots having diameters of 2 mm and on-center spacing of 4.5 mm was designed on 25 mm × 75 mm glass slides that were pre-coated with chromium and photoresist (Telic Company, Valencia, CA). The glass slides underwent photoresist exposure, development, chromium removal and HF etching to form ~10-μm-tall elevated nanowells. The remaining photoresist was removed using AZ 400T stripper. After thorough rinsing with water and drying with compressed nitrogen, the chip surface was then cleaned and activated with oxygen plasma treatment for 3 min using March Plasma Systems PX250 (Nordson, Concord, NH). The glass surface that was not protected with chromium was treated with 2% (v/v) heptadecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrodecyl)dimethylchlorosilane in 2,2,4-trimethylpentane for 30 min. After complete removal of the remaining silanization reagent by ethanol, protective chromium was removed using chromium etchant (Transene), leaving elevated hydrophilic nanowells on a hydrophobic background.

Cell Culture and Harvest

HeLa cells (ATCC) were grown in Eagle’s minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1× penicillin/streptomycin, with standard culture conditions of 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were harvested after 3 days of culture by detaching cells using Detachin™ Cell Detachment Solution (Amsbio, Cambridge, MA). The cell suspension was gently washed three times in 1× PBS to remove proteins present in the growth medium, after which cells were counted using a hemocytometer. The cell suspension was diluted to targeted concentrations based on 0.5 μL sample volumes for dispensing into nanowells.

Slide Preparation and Laser Microdissection of Mouse Tissue

All procedures involving animals were performed in accordance with protocols established in the NIH/NRC Guide and Use of Laboratory Animals and were reviewed by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Battelle, Pacific Northwest Division. C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Jackson Labs and tissue samples were prepared for LCM as described previously [39]. Briefly, mouse liver tissue was sectioned to a thickness of 10 μm using a ThermoFisher CryoStar NX-70 cryostat, and tissue sections were deposited on PEN membrane slides (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Germany) and stored at −80°C until use. Tissue sections were immediately immersed into 70% ethanol at 4°C for 15 s and then rehydrated for 30 s in deionized water. They were then immersed in Mayer’s hematoxylin solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) for 1 min, dipped twice in DI water to remove excess dye solution, and immersed in Scott’s Tap Water Substitute (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 s to dye the tissues. Tissues were then dehydrated by sequential immersion in 70% ethanol (1 min), 95% ethanol (1 min), 100% ethanol (1 min) and xylene (2 min). The sections were then dried in a fume hood for 10 min and used directly or stored at −80°C until use. Before experiments, nanowells were prepopulated with 200 nL DMSO droplets that served as capture medium for the excised tissue sections. LCM was performed using a PALM MicroBeam system (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Munich, Germany) as described previously [39].

Proteomic Sample Preparation in Droplets

Before use, the μPOTS chip was washed with isopropanol and water to minimize contamination. A low-volume micropipette (Pipet-Lite LTS Pipette L-2XLS+, Rainin, Barcelona, Spain) with a minimum dispensing volume of 0.2 μL was employed for sample/reagent dispensing. To minimize droplet evaporation, the chip was placed on a bag of ice (Figure 1a). For HeLa samples, 0.5 μL of cell suspension with target cell numbers was pipetted into the wells. An accurate cell count in each nanowell was determined using an inverted microscope. For tissue samples, square tissue cuts of varying dimensions were excised and catapulted by LCM into nanowells using our recently developed DMSO-interfaced protocol as described above [35].

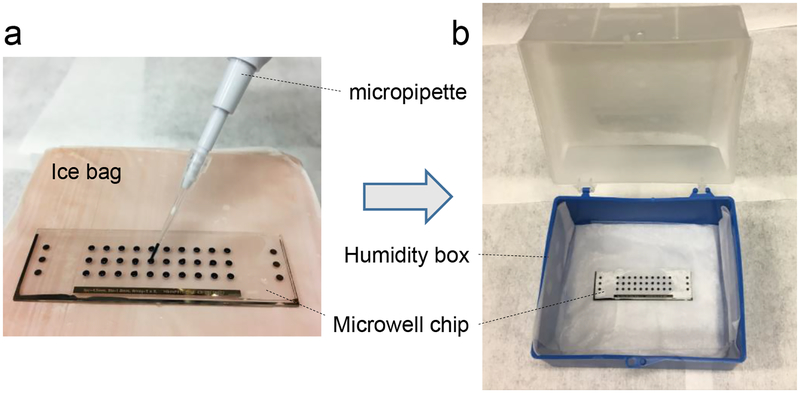

Figure 1.

Device and operation of μPOTS. (a) Microwell chip was placed on a bag of ice to reduce evaporation during reagent adding using a micropipette. (b) Reaction incubation in a home-made humid chamber.

For high-temperature and long-term incubation, a humidified chamber was made by lining the interior of a plastic box with wetted Kimwipe paper (Figure 1b). First, 0.5 μL of 50 mM ABC solution containing DDM (0.2%) and DTT (10 mM) was pipetted into either the HeLa cell droplets or mouse liver tissue-DMSO droplet. The chip was then placed inside the humid box and incubated at 70°C for 30 min to achieve cell lysis, protein extraction and disulfide bond reduction. Second, 0.5 μL of IAA solution (30mM in 50mM ABC) was dispensed into each droplet, followed by incubation in the dark at room temperature for 30 min to alkylate the sulfhydryl groups. For tissue samples, an additional step of DMSO removal under vacuum was required prior to the addition of IAA. Third, proteins were digested by first adding 0.5 μL of enzyme solution containing 2.5 ng Lys-C in 50 mM ABC to the droplet and incubating at 37°C for 4 h for predigestion, followed by addition of 0.5 μL of solution containing 2.5 ng trypsin in 50 mM ABC to each droplet with overnight incubation at 37°C.

Digested peptide samples in each nanowell were collected and stored in a section of fused silica capillary tubing (200 μm i.d., 360 μm o.d.). Before sample collection, capillary columns were cut to the desired length for the target sample volume. The droplet samples were collected by allowing the capillary columns to contact the nanowell surfaces, and samples were automatically drawn into the tubing using capillary forces. After sample collection, 1 μL of 0.1% formic acid (LC Buffer A) was pipetted into each nanowell to wash off residual peptides and collect them into the same capillary column. The capillary columns containing samples and their residual washes were sealed with Parafilm at both ends and stored at −20°C for short-term storage, or −70°C for long-term storage.

SPE-LC-MS setup

The SPE-LC-MS setup and instrumentation generally followed the settings for previously described nanoPOTS work [32] except some minor changes that were primarily due to the larger total sample volumes and specific LC column conditions. Notable changes include: (1) sample was driven through the SPE column at a higher flowrate of 2 μL/min for 10 min to desalt samples; (2) the LC separation flow rate was 60 nL/min, which was split from 300 nL/min; (3) linear 150-min gradient of 2–22% Buffer B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) and then 20-min gradient of 22–35% Buffer B were used for separation, and the LC column was washed by ramping Buffer B to 90% for 10 min, and finally re-equilibrated with Buffer A for another 15 min; (4) for different sample inputs, different Orbitrap scan resolutions and maximum injection times were used in MS2 settings to maximize sensitivity (240k and 502 ms for blank control and ~25-cell samples; 120k and 246 ms for ~55-cell samples; 60k and 118 ms for ~100-cell samples).

Data Analysis

All raw files were processed using MaxQuant (version 1.5.3.30) for feature detection, database searching and protein/peptide quantification[36] following settings described previously.[32] Tandem mass spectra were searched against the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot human database (downloaded on Dec 29, 2016 and containing 20,129 reviewed entries) and mouse database (download on Jan 28, 2017 and containing 16,844 reviewed entries) for HeLa cells and mouse liver tissue, respectively. The extracted data were further processed and visualized with Python using Pandas, Matplotlib_venn3 and Seaborn packages, for data analysis, Venn diagram plots and violin plots, respectively. Protein groups identified by at least two peptides were annotated using the online Gene Ontology (GO) database and tools at http://www.uniprot.org/ under Human or Mouse organisms for HeLa cells and mouse liver tissue samples, respectively.

Results and Discussion

μPOTS Sample and Reagent Handling Operations

The main challenge of low-microliter droplet-based sample preparation arises from droplet evaporation during liquid handling and the required hours-long incubations at elevated temperatures. In our previously reported nanoPOTS system [32], we overcame the challenge by operating the nano-pipetting robot in a sealed chamber with humidity maintained at 95% and applying a cover over the glass chips during extended incubations. For μPOTS, to simplify the overall experimental setup, we cooled the chip with an ice bag to reduce droplet evaporation (Figure 1a). We compared the evaporation speeds with and without the cooler by dispensing an array of 1 μL droplets on the chip. The test was performed in a typical lab environment with a temperature of 23°C and a humidity of 36%. Without the cooler, droplets dried in an average of 10.5 min (n=8). With cooling, no evident droplet evaporation was observed after two hours. In addition, the open-space operation greatly facilitated multiple-step reagent addition using the micropipette. Reagents with smallest volumes of 0.2 μL could be reliably dispensed into droplets using this method.

Proteome Coverage for <100 HeLa Cells

We first evaluated μPOTS with three different sample loading amounts (21–28, 48–54, 91–93 cells) using cultured HeLa cells. The range in cell numbers within each loading group was due to stochastic differences in cell numbers when dispensing the same volume. The number of identified unique peptides and proteins for cultured HeLa cells is shown in Figure 2, with supernatant of the most diluted cell sample and a reagent-only sample serving as blank controls (see Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) Fig. S1).

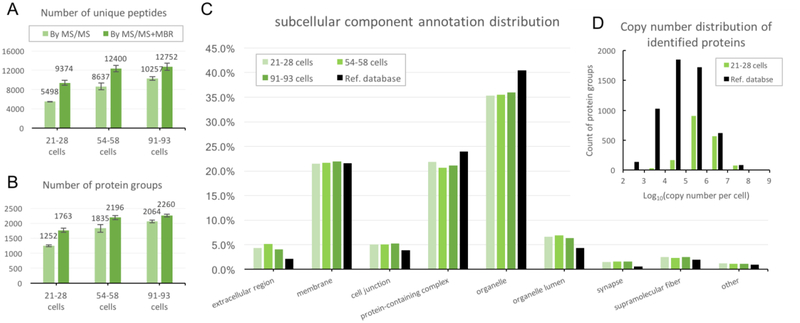

Figure 2.

Proteomic profiling results of samples with <100 HeLa cells. Number of identified peptides (A) and protein groups (B) were calculated in each cell loading group by either MS/MS only or MS/MS+MBR identification. (C) Gene Ontology annotation of all three groups’ proteomes in Cell Component aspect. (D) Comparison of the distribution of copy number per cell between the reference proteome and the proteome of the group containing 21–28 cells.

The average number of unique peptides identified by MS/MS was 5498, 8637 and 10257, for triplicate groups of increasing sample size, respectively (Figure 2A), leading to 1252, 1835 and 2064 identified protein groups (proteins) with <1% FDR (Figure 2B). By using the Match Between Runs (MBR) algorithm of Maxquant [36], average protein identifications increased to 1763, 2196, and 2260 for the three cell loadings. When a minimum of two peptides were required for identification, the average number of proteins was 1050, 1520, 1551 for MS/MS-only identification.

For MS/MS identification of the first two cell loading groups in μPOTS, although the numbers of input cells was higher than the corresponding sample loadings used for nanoPOTS [32] (21–28 cells vs. 10–14 cells, and 54–58 cells vs. 37–45 cells), the coverage was ~20% lower at both the peptide and protein levels. This is attributed to the compromise in sensitivity for μPOTS as a tradeoff of higher droplet volumes, which is limited by the minimum volume that the commercial micropipettes could precisely deliver, and the corresponding increased surface exposure on both the μPOTS chips and the sample transfer capillaries. The sample processing volume was ~8-fold higher for μPOTS than for nanoPOTS, so the well diameter had to double from 1 to 2 mm to maintain a similar contact angle (ESM Table S1). This led to a 4-fold increase in contact surface areas in the nanowells. Furthermore, during storage of the peptide digests in capillary columns, the contacting surface area to the inner wall of the column is proportional to the volume of the sample so that μPOTS had an 8× increase in exposure to the inner walls of the capillary transfer columns.

For MS/MS+MBR identification, the number of identified proteins also relies on other factors including the coverage achieved for reference samples and is thus less directly comparable between the two platforms. Still, ~1800 proteins were identified from 21–28 cells and ~2200 from 54–58 cells when MBR was employed, which is significantly higher than other previously reported sample preparation strategies aiming at cell numbers below 100 [14, 15]. 1756 of these were matched to a database providing an estimate of protein copy numbers per cell for 5443 proteins in HeLa [37] and indicated a dynamic range spanning more than four orders of magnitude. μPOTS results are biased to high-abundance proteins due to the use of only ~21–28 cells with ~4 ng total protein input, but 203 proteins were still detected at expression levels of <105 copies/cell.

The identified proteomes of all the three cell loading groups were further analyzed by Gene Ontology (GO) annotation[38, 39] in Cellular Component aspect and compared against the reference HeLa proteome annotation. The distribution of the proteins identified in μPOTS was similar to that of the bulk analysis, indicating that the samples prepared by μPOTS at all cell loading levels are non-discriminative to proteins among different subcellular components.

Quantitation and Reproducibility

The reproducibility of μPOTS was first assessed by the quality of protein digestion by examining the peptide spectrum matches (PSMs). The percentage of peptides generated by tryptic cleavage, average missed cleavages per miscleaved peptide and average length of the peptide sequences for the three cell loading groups were calculated (ESM Table S2).

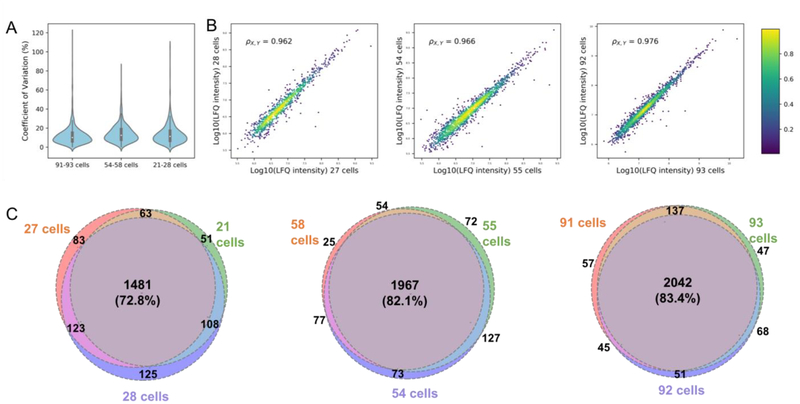

Further, by using label-free quantification (LFQ) intensity of proteins, pairwise Pearson’s correlation coefficients for any two samples within each cell loading group ranged from 0.96 to 0.98, and median CVs were ≤12.4% for all the three cell loading groups (Fig. 3B and ESM Fig. S2). The overlap of identified proteins from samples within each group is shown in Figure 3A, and all three groups showed >72% co-identified proteins among the three replicates. When two peptides were required for protein identification, the percentage of co-identified proteins exceeded 95% for all three cell loading groups (ESM Fig. S3). Together, these data suggest that μPOTS can be used for label-free quantification of samples of <100 mammalian somatic cells with acceptable dynamic range and robustness with only modestly reduced coverage relative to nanoPOTS.[32]

Figure 3.

Reproducibility of the proteomic profiling of HeLa cells prepared by μPOTS. (A) Violin plot of cell loading groups from 21–28 cells to 91–93 cells (n=3 in each group) (B) Correlation of log10(LFQ intensity) of identified proteins between samples with similar cell numbers (C) Venn diagram of identified proteins within each cell loading groups.

Application to Mouse Liver Tissue

As a typical model system for biological research and clinical trials, mouse attracts great interest in the study of its physiology and pathology by serving as an essential proof-of-concept in the discovery of medicines and solutions for human diseases. Mouse liver, due to its significance in metabolic and detoxification functions that are mediated by a large collection of proteins, has received even more attention in the scope for proteomics research.[40, 41] To demonstrate its potential application to more physiologically relevant samples, we applied μPOTS to square tissue sections that were sampled by LCM from a 10-μm-thick fresh-frozen mouse liver cross section.

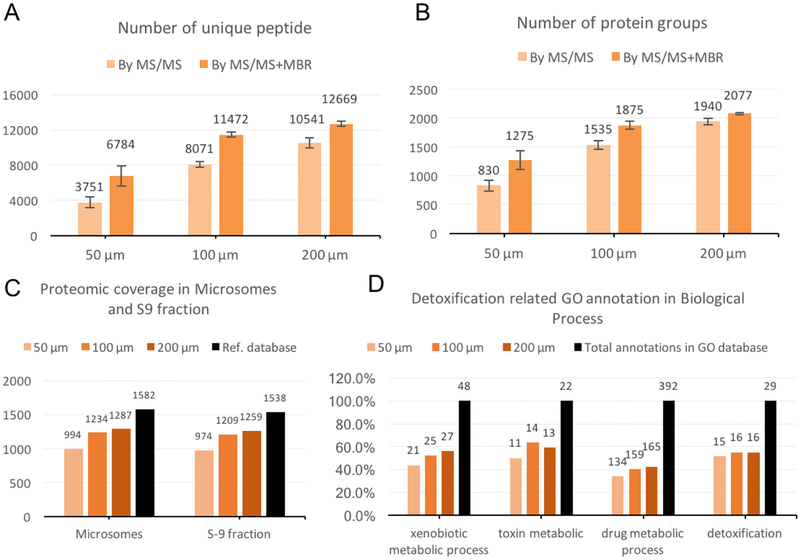

The numbers of identified peptides and proteins are shown in Figures 4A and 4B. From square tissue cuts having lateral dimensions of 50, 100 and 200 μm, (corresponding to ~10, 40 and 160 cells based on the average size of the mouse liver cells[37]), 1275, 1875 and 2077 protein groups were identified by MS/MS+MBR, and 1139, 1614 and 1872 protein groups were still identified when requiring at least two peptides for identification. This represents a depth of proteome coverage that typically requires several micrograms of proteins when using other benchtop sample processing workflows.[42]

Figure 4.

Proteomic profiling results of mouse liver tissue sections. Number of identified peptides (A) and protein groups (B) are calculated in each size of tissue cut by either MS/MS only identification or MS/MS+MBR identification. (C) Matching results of all three groups’ proteomes with reference proteomes identified from either microsome or S9 fraction. (D) Gene Ontology annotation of all three groups’ proteomes in detoxification related Biological Process aspect and comparison with total annotations in each term.

With its major functionalities in detoxification, liver cells contain numerous enzymes for drug metabolism, and most of them are enriched in subcellular microsomal parts. Deep proteomic profiling of isolated liver microsomes or liver’s S9 fraction (a mixture of microsomes and cytosol that is commonly used for drug metabolism studies in toxicology) have been studied recently using bulk sample preparation.[43] We aligned our identified mouse liver proteome to these reference data, which revealed that μPOTS-prepared samples identified >60% of the proteins that were found in homogenized bulk samples (Figure 4C).

We further analyzed the identified protein groups in the Biological Process aspect of GO annotations under terms of Xenobiotic Metabolic Process (GO:0006805), Toxin Metabolic (GO:0009404), Drug Metabolic Process (GO:0017144) and Detoxification (GO:0098754). The GO annotation of the proteomes revealed 34–50% of the total number of protein groups for all groups in the smallest samples, which increased to ~40–60% at the largest samples (Figure 4D). Important enzymes in the detoxification process of alcohol-derived acetaldehyde such as the aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member B1 (Q9CZS1), esterase D/formylglutathione hydrolase (Q9R0P3) and aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C13 (Q8VC28) were identified from all three sample sizes. Considering that we only used samples comprising ~14 liver cells from a 50-μm-sized tissue section providing spatial resolution comparable to that of cutting-edge MALDI-imaging systems,[34] this ratio of proteome coverage/sample size compares very favorably with most recent proteomic studies of trace samples.

Conclusions

In this work we developed μPOTS, a benchtop workflow and related apparatus to prepare trace samples for in-depth proteome profiling using a scaled-up droplet-based, one-pot strategy that was demonstrated successfully in our previous nanoPOTS work. The required equipment was dramatically reduced from a custom cubic-meter-sized robotic platform to a commercial pipette and ice bag-based cooler. As expected, a modest reduction in proteome coverage was observed relative to nanoPOTS due to the larger processing volumes and contacting surface areas, but >1000 proteins could still be identified from as few as ~25 somatic cells or fixed tissue samples at a spatial resolution comparable to cutting-edge imaging mass spectrometry. Without any complex robotic system or re-engineering of LC-MS instrumentation, μPOTS achieved a proteome profiling depth that has typically only been achievable for >1000 input cells. As a robust and easy-to-use benchtop sample preparation method for the deep proteomic profiling of trace samples, μPOTS should facilitate broad dissemination and suitability for many applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH grants R21 EB020976 and R33 CA225248. This research was performed using EMSL, a national scientific user facility sponsored by the Department of Energy’s Office of Biological and Environmental Research and located at PNNL.

Biographies

Kerui Xu is a postdoctoral research associate at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. His work is focused on developing benchtop, droplet based sample preparation methodologies for the deep proteome profiling of trace biological samples.

Yiran Liang is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at Brigham Young University. Under the supervision of Dr. Ryan T. Kelly, her research focuses on droplet-based trace biological sample preparation for proteome analysis using nanoLC-MS/MS systems.

Paul D. Piehowski is a scientist in the Earth and Biological Sciences Directorate at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. His research is focused on the application of proteomics measurements to clinical studies and increasing the depth, throughput, reproducibility and sensitivity of omics measurements using mass spectrometry.

Maowei Dou is a postdoctoral research associate at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. He is currently working on developing bioanalytical technologies combining droplet-based biological sample preparation with ultrasensitive nanoLC-MS/MS for deep proteome profiling of trace biological samples.

Kaitlynn C. Schwarz is an undergraduate research associate at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. While completing her mechanical engineering degree at Washington State University, she designs and fabricates microfluidic devices for a variety of applications.

Rui Zhao is a scientist in the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. His current research focuses on the development and application of new ultrasensitive Nano-HPLC systems with mass spectrometry for top-down and bottom-up proteomics.

Ryan L. Sontag is a scientist in the Earth and Biological Sciences Directorate at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. His research interests include pathogen/host interactions, synthetic biology, and intracellular signaling and he supports many different projects with tissue culture, histology, and other molecular biology techniques.

Ronald J. Moore is a Project Manager in the Integrative Omics Group at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. He has 29 years of experience working with a wide variety of analytical instrumentation and currently specializes in customized automated online sample handling and processing techniques coupled with nano-flow UPLC-MS.

Ying Zhu is a scientist in the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory with over ten years’ experience in ultrasensitive bioanalysis using microfluidic techniques and mass spectrometry. His current research focuses on the development of nanodroplet sample processing systems and its application to single cell typing of mammalian and plant cells, in-depth proteome mapping of tissue heterogeneity, and understanding microbial-plant interactions with high spatial and temporal resolution.

Ryan T. Kelly is an Associate Professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at Brigham Young University with a joint appointment as a Senior Research Scientist at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. His research interests focus on the development of microfluidic sample handling, advanced separations and ultrasensitive mass spectrometry to increase the sensitivity and throughput of biochemical analyses.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tyers M, Mann M. From genomics to proteomics. Nature. 2003; 422(6928):193–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zubarev RA. The challenge of the proteome dynamic range and its implications for in-depth proteomics. Proteomics. 2013; 13(5):723–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein AM, Mazutis L, Akartuna I, Tallapragada N, Veres A, Li V, Peshkin L, Weitz DA, Kirschner MW. Droplet Barcoding for Single-Cell Transcriptomics Applied to Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell. 2015; 161(5):1187–1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macosko EZ, Basu A, Satija R, Nemesh J, Shekhar K, Goldman M, Tirosh I, Bialas AR, Kamitaki N, Martersteck EM, Trombetta JJ, Weitz DA, Sanes JR, Shalek AK, Regev A, McCarroll SA. Highly Parallel Genome-wide Expression Profiling of Individual Cells Using Nanoliter Droplets. Cell. 2015; 161(5):1202–1214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagrath S, Sequist LV., Maheswaran S, Bell DW, Irimia D, Ulkus L, Smith MR, Kwak EL, Digumarthy S, Muzikansky A, Ryan P, Balis UJ, Tompkins RG, Haber DA, Toner M. Isolation of rare circulating tumour cells in cancer patients by microchip technology. Nature. 2007; 450(7173):1235–1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang N, Xu M, Wang P, Li L. Development of mass spectrometry-based shotgun method for proteome analysis of 500 to 5000 cancer cells. Anal Chem. 2010; 82(6):2262–2271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bendall SC, Simonds EF, Qiu P, Amir E-a. D, Krutzik PO, Finck R, Bruggner RV, Melamed R, Trejo A, Ornatsky OI, Balderas RS, Plevritis SK, Sachs K, Pe’er D, Tanner SD, Nolan GP. Single-Cell Mass Cytometry of Differential Immune and Drug Responses Across a Human Hematopoietic Continuum. Science. 2011; 332(6030):687–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan DJ, Nei D, Prentice BM, Rose KL, Caprioli RM, Spraggins JM. Protein identification in imaging mass spectrometry through spatially targeted liquid micro-extractions. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2018; 32(5):442–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benson H Family breakdown in the UK: it ‘ s NOT about divorce. J Proteomics. 2010; 107(December):25–31 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mascini NE, Heeren RMA. Protein identification in mass-spectrometry imaging. TrAC - Trends Anal Chem. 2012; 40:28–37 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun L, Zhu G, Zhao Y, Yan X, Mou S, Dovichi NJ. Ultrasensitive and fast bottom-up analysis of femtogram amounts of complex proteome digests. Angew Chemie - Int Ed. 2013; 52(51):13661–13664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith RD, Shen Y, Tang K. Ultrasensitive and Quantitative Analyses from Combined Separations - Mass Spectrometry for the Characterization of Proteomes. Acc Chem Res. 2004; 37(4):269–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun X, Kelly RT, Tang K, Smith RD. Ultrasensitive nanoelectrospray ionization-mass spectrometry using poly(dimethylsiloxane) microchips with monolithically integrated emitters. Analyst. 2010; 135(9):2296–2302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen Y, Tolić N, Masselon C, Paša-Tolić L, Camp DG, Hixson KK, Zhao R, Anderson GA, Smith RD. Ultrasensitive Proteomics Using High-Efficiency On-Line Micro-SPE-NanoLC-NanoESI MS and MS/MS. Anal Chem. 2004; 76(1):144–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li S, Plouffe BD, Belov AM, Ray S, Wang X, Murthy SK, Karger BL, Ivanov AR. An Integrated Platform for Isolation, Processing, and Mass Spectrometry-based Proteomic Profiling of Rare Cells in Whole Blood. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015; 14(6):1672–1683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crowell AMJ, Wall MJ, Doucette AA. Maximizing recovery of water-soluble proteins through acetone precipitation. Anal Chim Acta. 2013; 79648–79654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma R, Dill BD, Chourey K, Shah M, Verberkmoes NC, Hettich RL. Coupling a detergent lysis/cleanup methodology with intact protein fractionation for enhanced proteome characterization. J Proteome Res. 2012; 11(12):6008–6018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feist P, Hummon AB. Proteomic challenges: Sample preparation techniques for Microgram-Quantity protein analysis from biological samples. Int J Mol Sci. 2015; 16(2):3537–3563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho HR, Park JS, Wood TD, Choi YS. Longitudinal assessment of peptide recoveries from a sample solution in an autosampler vial for proteomics. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2015; 36(1):312–321 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen EI, McClatchy D, Sung KP, Yates JR. Comparisons of mass spectrometry compatible surfactants for global analysis of the mammalian brain proteome. Anal Chem. 2008; 80(22):8694–8701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laganowsky A, Reading E, Hopper JTS, Robinson CV. Mass spectrometry of intact membrane protein complexes. Nat Protoc. 2013; 8(4):639–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X Less is More: Membrane Protein Digestion Beyond Urea–Trypsin Solution for Next-level Proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015; 14(9):2441–2453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin JG, Rejtar T, Martin SA. Integrated microscale analysis system for targeted liquid chromatography mass spectrometry proteomics on limited amounts of enriched cell populations. Anal Chem. 2013; 85(22):10680–10685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes CS, Foehr S, Garfield DA, Furlong EE, Steinmetz LM, Krijgsveld J. Ultrasensitive proteome analysis using paramagnetic bead technology. Mol Syst Biol. 2014; 10(10):757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiśniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat Methods. 2009; 6(5):359–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sielaff M, Kuharev J, Bohn T, Hahlbrock J, Bopp T, Tenzer S, Distler U. Evaluation of FASP, SP3, and iST Protocols for Proteomic Sample Preparation in the Low Microgram Range. J Proteome Res. 2017; 16(11):4060–4072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang EL, Piehowski PD, Orton DJ, Moore RJ, Qian WJ, Casey CP, Sun X, Dey SK, Burnum-Johnson KE, Smith RD. Snapp: Simplified nanoproteomics platform for reproducible global proteomic analysis of nanogram protein quantities. Endocrinology. 2016; 157(3):1307–1314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clair G, Piehowski PD, Nicola T, Kitzmiller JA, Huang EL, Zink EM, Sontag RL, Orton DJ, Moore RJ, Carson JP, Smith RD, Whitsett JA, Corley RA, Ambalavanan N, Ansong C. Spatially-Resolved Proteomics: Rapid Quantitative Analysis of Laser Capture Microdissected Alveolar Tissue Samples. Sci Rep. 2016; 639223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun L, Dubiak KM, Peuchen EH, Zhang Z, Zhu G, Huber PW, Dovichi NJ. Single cell proteomics using frog (Xenopus laevis) blastomeres isolated from early stage embryos, which form a geometric progression in protein content. Anal Chem. 2016; 88(13):6653–6657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rizzo DG, Prentice BM, Moore JL, Norris JL, Caprioli RM. Enhanced Spatially Resolved Proteomics Using On-Tissue Hydrogel-Mediated Protein Digestion. Anal Chem. 2017; 89(5):2948–2955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wisztorski M, Desmons A, Quanico J, Fatou B, Gimeno JP, Franck J, Salzet M, Fournier I. Spatially-resolved protein surface microsampling from tissue sections using liquid extraction surface analysis. Proteomics. 2016; 16(11–12):1622–1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu Y, Piehowski PD, Zhao R, Chen J, Shen Y, Moore RJ, Shukla AK, Petyuk VA, Campbell-Thompson M, Mathews CE, Smith RD, Qian WJ, Kelly RT. Nanodroplet processing platform for deep and quantitative proteome profiling of 10–100 mammalian cells. Nat Commun. 2018; 9(1):882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu Y, Clair G, Chrisler WB, Shen Y, Zhao R, Shukla AK, Moore RJ, Misra RS, Pryhuber GS, Smith RD, Ansong C, Kelly RT. Proteomic Analysis of Single Mammalian Cells Enabled by Microfluidic Nanodroplet Sample Preparation and Ultrasensitive NanoLC-MS. Angew Chemie Int Ed. 2018; 57(38):12370–12374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aasebø E, Forthun RB, Berven F, Selheim F, Hernandez-Valladares M. Global Cell Proteome Profiling, Phospho-signaling and Quantitative Proteomics for Identification of New Biomarkers in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2016; 17(1):52–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu Y, Dou M, Piehowski PD, Liang Y, Wang F, Chu RK, Chrisler WB, Smith JN, Schwarz KC, Shen Y, Shukla AK, Moore RJ, Smith RD, Qian W-J, Kelly RT. Spatially Resolved Proteome Mapping of Laser Capture Microdissected Tissue with Automated Sample Transfer to Nanodroplets. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2018; 17(9):1864–1874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tyanova S, Temu T, Cox J. The MaxQuant computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun proteomics. Nat Protoc. 2016; 11(12):2301–2319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiśniewski JR, Hein MY, Cox J, Mann M. A “Proteomic Ruler” for Protein Copy Number and Concentration Estimation without Spike-in Standards. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014; 13(12):3497–3506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carbon S, Dietze H, Lewis SE, Mungall CJ, Munoz-Torres MC, Basu S, Chisholm RL, Dodson RJ, Fey P, Thomas PD, Mi H, Muruganujan A, Huang X, Poudel S, Hu JC, Aleksander SA, McIntosh BK, Renfro DP, Siegele DA, Antonazzo G, Attrill H, Brown NH, Marygold SJ, Mc-Quilton P, Ponting L, Millburn GH, Rey AJ, Stefancsik R, Tweedie S, Falls K, Schroeder AJ, Courtot M, Osumi-Sutherland D, Parkinson H, Roncaglia P, Lovering RC, Foulger RE, Huntley RP, Denny P, Campbell NH, Kramarz B, Patel S, Buxton JL, Umrao Z, Deng AT, Alrohaif H, Mitchell K, Ratnaraj F, Omer W, Rodríguez-López M, Chibucos MC., Giglio M, Nadendla S, Duesbury MJ, Koch M, Meldal BHM, Melidoni A, Porras P, Orchard S, Shrivastava A, Chang HY, Finn RD, Fraser M, Mitchell AL, Nuka G, Potter S, Rawlings ND, Richardson L, Sangrador-Vegas A, Young SY, Blake JA, Christie KR, Dolan ME, Drabkin HJ, Hill DP, Ni L, Sitnikov D, Harris MA, Hayles J, Oliver SG, Rutherford K, Wood V, Bahler J, Lock A, De Pons J, Dwinell M, Shimoyama M, Laulederkind S, Hayman GT, Tutaj M, Wang SJ, D’Eustachio P, Matthews L, Balhoff JP, Balakrishnan R, Binkley G, Cherry JM, Costanzo MC, Engel SR, Miyasato SR, Nash RS, Simison M, Skrzypek MS, Weng S, Wong ED, Feuermann M, Gaudet P, Berardini TZ, Li D, Muller B, Reiser L, Huala E, Argasinska J, Arighi C, Auchincloss A, Axelsen K, Argoud-Puy G, Bateman A, Bely B, Blatter MC, Bonilla C, Bougueleret L, Boutet E, Breuza L, Bridge A, Britto R, Hye-A-Bye H, Casals C, Cibrian-Uhalte E, Coudert E, Cusin I, Duek-Roggli P, Estreicher A, Famiglietti L, Gane P, Garmiri P, Georghiou G, Gos A, Gruaz-Gumowski N, Hatton-Ellis E, Hinz U, Holmes A, Hulo C, Jungo F, Keller G, Laiho K, Lemercier P, Lieberherr D, Mac-Dougall A, Magrane M, Martin MJ, Masson P, Natale DA, O’Donovan C, Pedruzzi I, Pichler K, Poggioli D, Poux S, Rivoire C, Roechert B, Sawford T, Schneider M, Speretta E, Shypitsyna A, Stutz A, Sundaram S, Tognolli M, Wu C, Xenarios I, Yeh LS, Chan J, Gao S, Howe K, Kishore R, Lee R, Li Y, Lomax J, Muller HM, Raciti D, Van Auken K, Berriman M, Stein, Paul Kersey L, Sternberg PW, Howe D, Westerfield M. Expansion of the gene ontology knowledgebase and resources: The gene ontology consortium. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45(D1):D331–D338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Gene Ontology Consortium, Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewi S, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G. Gene ontologie: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet. 2000; 25(1):25–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gazzana G, Borlak J. An update on the mouse liver proteome. Proteome Sci. 2009; 7:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lai KKY, Kolippakkam D, Beretta L. Comprehensive and quantitative proteome profiling of the mouse liver and plasma. Hepatology. 2008; 47(3):1043–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanca A, Abbondio M, Pisanu S, Pagnozzi D, Uzzau S, Addis MF. Critical comparison of sample preparation strategies for shotgun proteomic analysis of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples: Insights from liver tissue. Clin Proteomics. 2014; 11(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Golizeh M, Schneider C, Ohlund LB, Sleno L. Multidimensional LC-MS/MS analysis of liver proteins in rat, mouse and human microsomal and S9 fractions. EuPA Open Proteomics. 2015; 6:16–27 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.