Abstract

Late-stage synthesis of α,β-unsaturated aryl ketones remains an unmet challenge in organic synthesis. Herein, we report a photocatalytic non-chain radical aroyl-chlorination of alkenes via 1,3-chlorine atom shift to form β-chloroketones as masked enones that liberate the desired enones upon workup. This strategy suppresses side reactions of enone products such as double aroylation, E/Z isomerization, [2+2]-dimerization, and cross-[2+2]-cycloaddition under photoredox-catalysed conditions. The reaction tolerates a wide array of functional groups and complex molecules including derivatives of peptides, sugars, natural products, nucleosides, and marketed drugs, and offers a potential application in modern drug discovery programs. Notably, addition of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridine enhances the quantum yield and efficiency of the cross-coupling reaction. Experimental and computational studies suggest a mechanism involving PCET, formation and reaction of α-chloro-α-hydroxy benzyl radical, and 1,3-chlorine atom shift. These discoveries and mechanistic insights are useful in the development of new photocatalytic reactions.

Keywords: photoredox, enones, radical, aroylation, aroyl chlorides

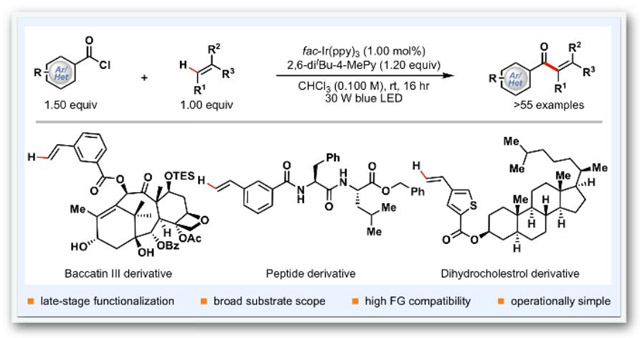

Graphical Abstract

A photocatalytic β-selective alkene aroylation using readily available aroyl chlorides and activated alkenes is developed. The synthetic utility of the reaction is highlighted by its broad functional group compatibility and high levels of chemo- and regioselectivity. The reaction is amenable to late-stage functionalization of complex molecules including derivatives of sugars, peptides, natural products, nucleosides, and commercially available drugs.

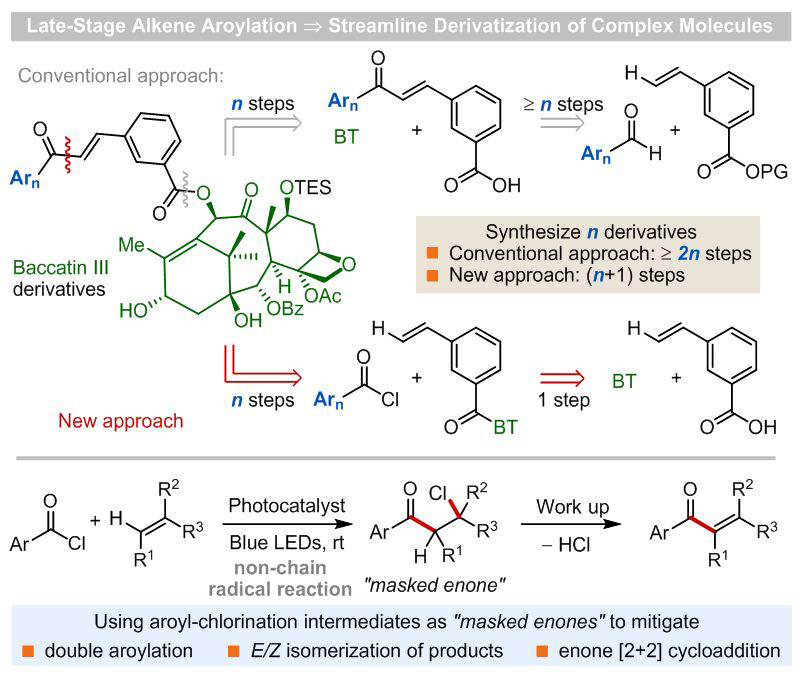

Late-stage C–H functionalization of biorelevant molecules is a powerful strategy for the discovery of novel functional molecules, because it avoids laborious de novo synthesis of new analogues, increases the efficiency of structure-activity relationship studies, and produces promising new candidates that might have never been evaluated otherwise.[1] Thus, establishment of new methodologies that introduce useful pharmacophores such as α,β-unsaturated aryl ketones at late-stages of a synthesis is highly desirable. Aryl vinyl ketones are key components of synthetic building blocks, natural products, and pharmaceuticals and have important anticancer, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and immunosuppressive activities.[2] Consequently, in addition to the conventional stoichiometric reactions,[3] a range of catalytic intermolecular strategies for the preparation of aryl enones, such as cross-metathesis reactions,[4] transition metal-catalyzed hydroacylation of alkynes,[5] copper-catalyzed dehydrogenative cross-coupling reactions,[6] palladium-catalyzed carbonylation reactions,[7] NHC-catalyzed (NHC: N-heterocyclic carbene) olefination of aldehydes using vinyliodonium salts,[8] and photocatalytic coupling reactions of α-keto-carboxylic acids and styrenes in the presence of a stoichiometric amount of SelectFluor™, a strong oxidant,[9] have been developed in recent years.[10] Although these elegant approaches have provided access to a range of simple α,β-unsaturated aryl ketones, the development of mild and general catalytic methods for late-stage synthesis of this important pharmacophore remains a significant challenge in organic synthesis. To address this unmet need, we examined photoredox-catalyzed acyl radical chemistry,[11],[12],[13] in which photo-catalytically generated aroyl radicals can react with olefins to form a C(sp2)-C(sp3) bond and alkyl radical intermediates.[14] Direct oxidation of these alkyl radicals by photoredox catalysts to the corresponding cations followed by deprotonation to afford α,β-unsaturated carbonyls is feasible in view of their electrochemical character.[15] However, both the efficiency and generality of such an approach are limited because (i) the enone products, especially the β-mono-substituted enones, are susceptible to a second radical addition of nucleophilic aroyl radicals, forming doubly aroylated side products, and (ii) the α,β-unsaturated carbonyl products can undergo E/Z-isomerization,[16] [2+2]-dimerization, and cross [2+2]-cycloaddition with alkenes[17] via a photocatalytic energy transfer mechanism. We questioned whether these challenges could be addressed by minimizing the amount of enones generated in the reaction mixture through producing masked enones, for example, β-chloroketones (Scheme 1).[18] We envisioned that direct aroyl-chlorination of alkenes using readily available aroyl chlorides[19] should give the desired masked enones, which then would undergo HCl elimination upon workup to liberate α,β-unsaturated aryl ketone products.[20] This formal β-selective alkenyl C–H aroylation strategy is appealing because it obviates the use of stoichiometric quantities of strong oxidants such as SelectFluorTM[9] and eliminates the need for pre-functionalization of the alkenes. As a result, it will allow direct incorporation of the aroyl group at any time towards the target synthesis. Herein, we report (i) the successful development of a mild photocatalytic protocol that enables late-stage synthesis of α,β-unsaturated aryl ketones from aroyl chlorides and alkenes, (ii) unprecedented effects of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridine additive on the reaction efficiency and quantum yield, and (ii) a novel reaction mechanism of aroyl-chlorination of alkenes.

Scheme 1.

Photocatalytic β-aroylation of alkenes. BT = Baccatin

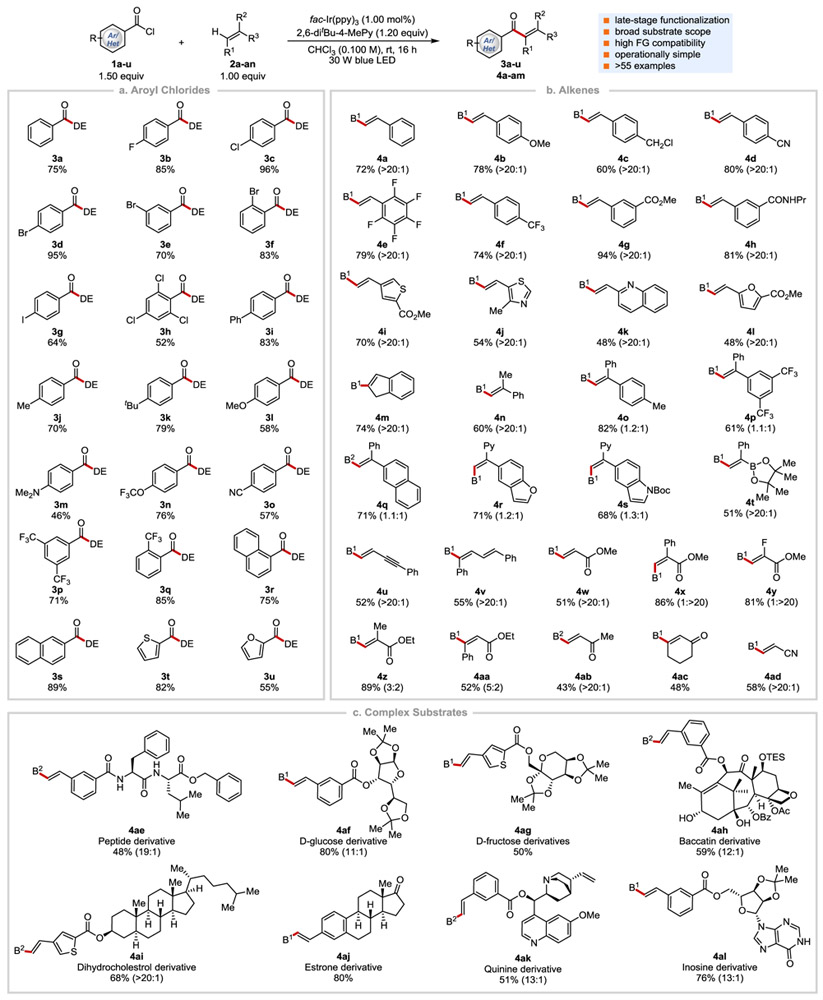

After a systematic variation of different reaction parameters, such as additives, solvents, photoredox catalysts, concentrations, and stoichiometries, we were pleased to identify optimal reaction conditions in which a mixture of 4-fluorobenzoyl chloride (1b, 1.50 equiv), 1,1-diphenyl-ethylene (2am, 1.00 equiv), fac-Ir(ppy)3 {fac tris[2-phenylpyridinato-C2,N]iridium(III), 1.00 mol%}, and 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridine (1.20 equiv) in CHCl3 (0.100 M) at 23 °C with irradiation by a blue LED light for 16 h afforded the desired product 3b in 85% isolated yield.[21] Although aliphatic acyl chlorides failed to react under these conditions, a diverse set of aroyl chlorides was successfully coupled to afford the desired enone products (Table 1a). For example, electron-neutral (1a, 1r-1s), electron-rich (1i-1m), and electron poor (1n-1q) aroyl chlorides reacted well under these reaction conditions affording the desired enones in 46–96% isolated yields. Different halogen functionalities (1b-1h), in particular, Br and I, survived the reaction, and provided synthetic handles for further structural elaboration through metal-catalyzed coupling reactions. The reaction tolerated o-, m-, and p-substituted aroyl chlorides (1d-1f). Substrates bearing extended π-system (1r, 1s) and heteroarenes such as thiophene (1t) and furan (1u) reacted smoothly, providing the desired products in 55–89% yields.

Table 1.

Selected examples of the coupling reaction between aroyl chlorides and alkenes.[a]

|

Cited yields and E/Z ratio. in the parenthesis are of isolated material. DE = 1,1-diphenylethylenyl, B1 = 2-trifluorobenzoyl, B2 = 4-chlorobenzoyl, Bz = benzoyl, Ac = acetyl, Py = pyridyl, TES = triethylsilyl, Boc = tert-butyloxycarbonyl, Pr = n-propyl, 2-6-ditBu-4-MePy = 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridine

We next directed our attention to examine the scope of alkenes and found that a wide range of mono- and di-substituted alkenes participate in this coupling reaction, affording the desired enones in modest to good yields (Table 1b). For example, various styrenes regardless of their electronics (2a-2h, 2m-2t, 2v, 2x, 2aa) were viable substrates. Alkenes substituted with biologically important heteroarenes such as thiophene (2i), thiazole (2j), quinoline (2k), furan (2l), pyridine (2r-2s), benzofuran (2r), and indole (2s) were compatible under the optimized reaction conditions. Both 1,2- and 1,1-disubstituted (hetero)aryl alkenes (2m-2t, 2v) reacted to give the desired trisubstituted enones in yields of 51–82%. The E and Z diastereoselectivity of the resulting enones is determined by the sterics of alkene substituents. While alkenes with sterically distinct substituents afforded one diastereomer (2n, 2t) exclusively, alkenes with substituents of similar sizes gave a mixture of diastereomers (1–1.3:1, 2o-2s). Most of the mono-substituted alkenes afforded the desired products as a single diastereomer. Although aliphatic alkenes afforded only trace amount of the desired products, our method was successfully applied to other alkene derivatives such as an enyne (2u), a diene (2v), mono- and di-substituted α,β-unsaturated esters (2w-2aa), acyclic (2ab) and cyclic (2ac) enones, and acrylonitrile (2ad) to furnish the corresponding products in 43–89% yields. More importantly, the protocol allows a straightforward and selective synthesis of molecular scaffolds (e.g., 4m, 4n, 4t, 4v, 4ac) that are otherwise difficult to access.

To demonstrate the amenability of the photocatalytic alkene aroylation process to late-stage synthetic applications, drug-like molecules were subjected to the standard reaction conditions (Table 1c). For example, derivatives of peptides, sugars, natural products, nucleosides, and marketed drugs bearing functional groups such as free hydroxyl groups, tertiary amines, alkyl alkenes, acetal and triethylsilyl protecting groups, oxetane, ketones, and heteroaromatics were successfully aroylated to afford the desired products (4ae-4al) in 48–80% yields and with excellent levels of chemo-, regio-, and diastereoselectivity. It is noteworthy that preparation of these complex aryl enones via the cross-metathesis protocol is challenging due to (i) the instability and limited availability of aryl vinyl ketones and (ii) the difficulty in distinguishing between two different terminal alkenes (4ak). Thus, our strategy is complementary to the cross-metathesis.

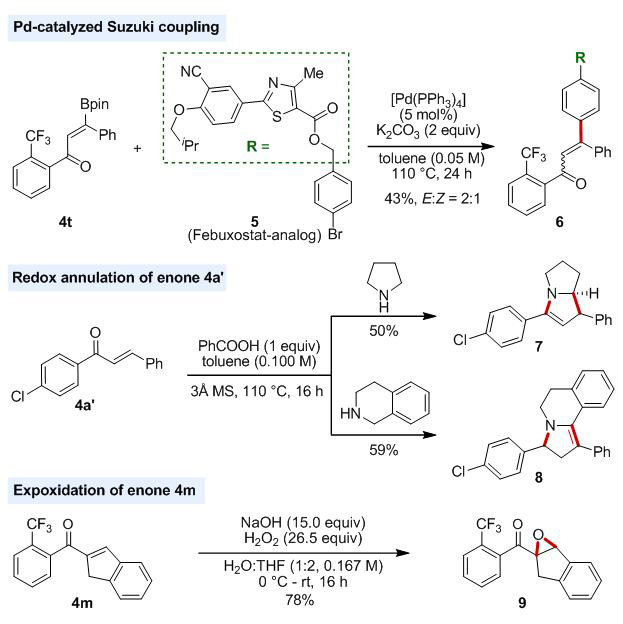

To illustrate the synthetic utility of the enone products for preparation of useful molecular scaffolds, we derivatized the products under various reaction conditions (Scheme 2). Treatment of 4t, an enone derivative that is difficult to prepare otherwise, with the Febuxostat-derivative 5 under Suzuki coupling reaction conditions afforded the desired product 6 in 43% yield with 2:1 E:Z-ratio. Under redox annulation reaction conditions, the chalcone 4a’ coupled with pyrrolidine and tetrahydroisoquinoline, forming the cyclic amines 7 and 8, respectively, in modest yields.[22] The enone 4m underwent epoxidation smoothly to afford the desired product in 78% yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthetic utility of the enone products.

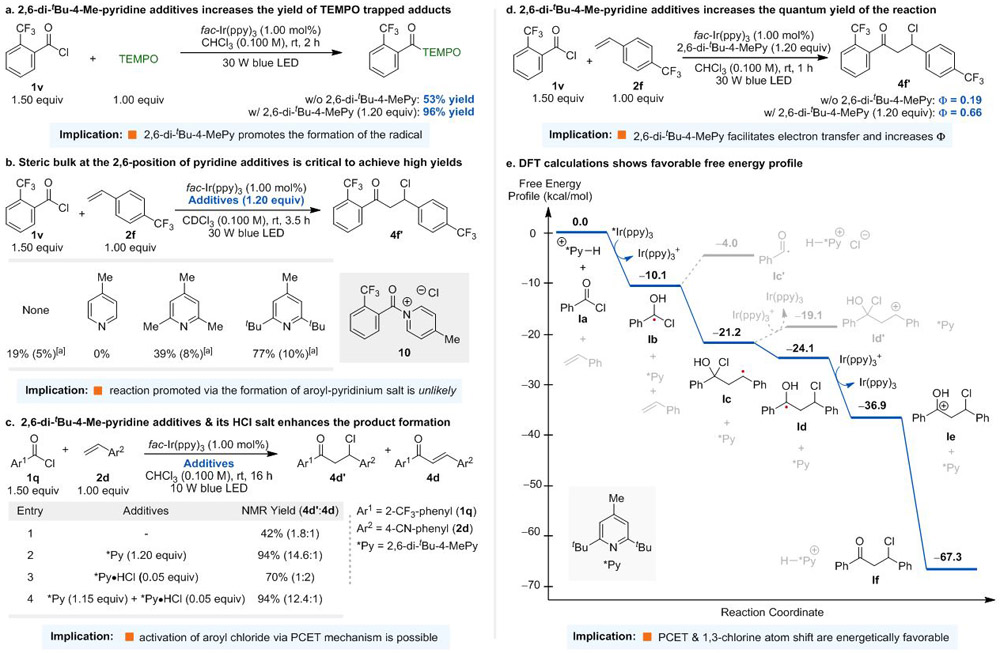

It is noteworthy that 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridine additive is critical for the success of the reaction. We conducted a series of experiments to understand the role of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridine additive. First, Stern-Volmer experiments revealed that aroyl chlorides quench excited fac-*Ir(ppy)3 photocatalysts but alkenes and 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridine do not. Interestingly, the presence of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridine enhanced the quenching constant of aroyl chlorides from 9.89 × 108 M−1s−1 to 1.29 × 109 M−1s−1 (Figure S1). In addition, TEMPO [(2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl] trapping experiments demonstrated that 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridine additive increased the yield of the benzoyl-TEMPO adduct from 53% to 96%. These observations suggested that the reaction proceeds through a radical mechanism and the additive promotes the formation of the aroyl radicals (Scheme 3a). We also noticed that the steric bulk at the 2,6-position of pyridine is crucial in obtaining high yields and no desired product was observed by using 4-methylpyridine as the additive (Scheme 3b). 1H-NMR studies showed a significant downfield shift of 4-methylpyridine protons after the addition of aroyl chloride 1q, indicating the formation of aroyl-pyridinium salt 10 (Figure S3). Once 10 was formed, the 1H-NMR of the reaction mixture remained unchanged even after irradiation with blue LEDs for 16 hours. Thus, these results rule out the aroyl chloride activation via the formation of aroyl-pyridinium salts. Notably, the addition of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridine increased both the product yield (4d’ and 4d) and the ratio of product distribution (Scheme 3c, entries 1 and 2), favouring the formation of the chloro-product 4d’. These observations implied that 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridine (*Py) additive serves more than just a base. Although the exact role of the 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridine requires further studies, we speculated that a small amount of HCl formed in the reaction mixture protonates the pyridine additive to give the corresponding *Py-HCl salt.[23] This salt may act as a Brønsted acid catalyst and facilitate the generation of the α-chloro-α-hydroxybenzyl radical via the proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) mechanism.[24] Indeed, the addition of 0.05 equivalents of *Py-HCl salt and a mixture of *Py/*Py-HCl (1.15/0.05 equiv) improved the product yield from 42% to 70% and 94% (entries 1, 3, and 4), respectively,[25] demonstrating the feasibility of the PCET reaction pathway. Furthermore, the quantum yield of the reaction was increased from 0.19 to 0.66 by the addition of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridine additive (Scheme 3d).[11d, 26] Since the quantum yield is lower than 1, an extended radical chain reaction mechanism is unlikely, which corroborates with Light ON/OFF experiments (Figure S6).

Scheme 3. Mechanistic studies.

All energies are Gibbs free energies in kcal/mol computed at the M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p)/SMD(CHCl3)//M06-2X/6-31+G(d)/SMD(CHCl3) level of theory using benzoyl chloride and styrene as substrates. [a] Cited yields in the parenthesis are of amount of the corresponding enone formed in the reaction mixture. See SI for details.

Detailed DFT calculations provided additional insights into the reaction mechanism (Scheme 3e). First of all, the proposed PCET step to form α-chloro-α-hydroxybenzyl radical Ib is thermodynamically favourable.[27] Notably, instead of undergoing HCl elimination to give the benzoyl radical Ic’, the radical Ib reacts with styrene to form benzyl radical Ic. In addition, while an intermolecular oxidation of Ic by Ir(ppy)3+ to form benzylic cation Id’ is an endergonic process, an intramolecular 1,3-chlorine atom shift[28] to produce radical Id is an exergonic reaction. Subsequent single electron oxidation of Id by Ir(ppy)3+ and deprotonation of Ie are both highly exothermic.

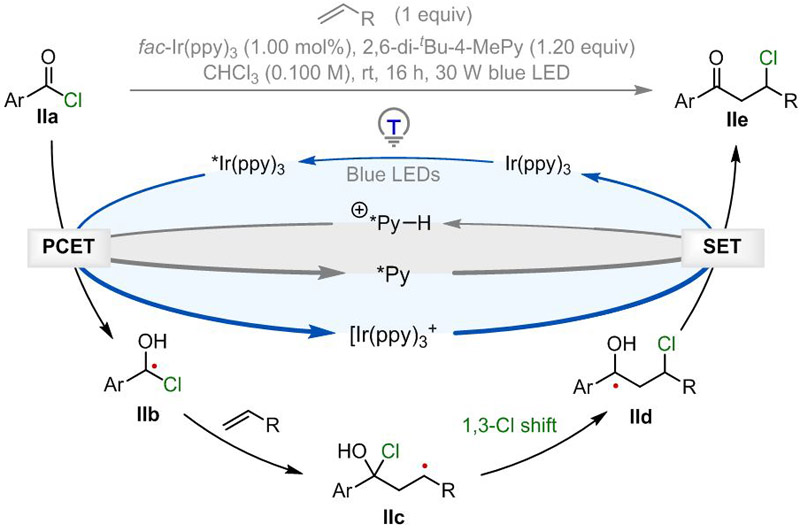

Based on these experimental and computational studies, a plausible reaction mechanism is depicted in Scheme 4. Photoexcitation of the photocatalyst Ir(ppy)3 produces the long-lived excited *Ir(ppy)3 (t½ = 1.9 μs, E½ IV/III* = –1.73 V vs SCE).[29] In the presence of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridinium species, aroyl chloride IIa (Ep of benzoyl chloride = –1.02 V vs SCE)[19b] undergoes a proton couple electron transfer (PCET) process with *Ir(ppy)3 to liberate 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridine and α-chloro-α-hydroxy benzyl radical IIb. This nucleophilic radical adds to an alkene to give intermediate IIc followed by 1,3-chlorine atom shift to afford α-hydroxy radical IId. Single electron oxidation of IId by Ir(ppy)3+ followed by deprotonation regenerates the ground state Ir(ppy)3 and affords the desired β-chloro-ketone IIe, which delivers the final enone upon workup.

Scheme 4.

Proposed reaction mechanism.

In conclusion, we have developed a photocatalytic β-selective alkene aroylation using readily available aroyl chlorides and activated alkenes. The synthetic utility of the reaction is highlighted by its broad functional group compatibility and high levels of chemo- and regioselectivity. The reaction is amenable to late-stage functionalization of complex molecules including derivatives of sugars, peptides, natural products, nucleosides, and commercially available drugs. Notably, 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridine additive serves more than a base, it also promotes electron transfer, increases quantum yields, and enhances the reaction efficiency. DFT calculations suggests that a reaction mechanism involving PCET, formation and reaction of α-chloro-α-hydroxy benzyl radical, and 1,3-chlorine atom shift is operable. We anticipate that these new mechanistic insights will be useful in the development of photocatalytic reactions and that this mild, versatile reaction will find applications in modern drug discovery and development programs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R35GM119652 and R35GM128779). We thank Prof. James K. McCusker and James Luliano for insightful discussion. We also greatly appreciate the helpful comments and suggestions provided by the referees Calculations were performed at the Center for Research Computing at the University of Pittsburgh.

References

- [1].Cernak T, Dykstra KD, Tyagarajan S, Vachal P, Krska SW, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2] a).Amslinger S, ChemMedChem 2010, 5, 351; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sahu NK, Balbhadra SS, Choudhary J, Kohli DV, Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 209; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wei Y, Shi M, Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 6659; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Heravi MM, Ahmadi T, Ghavidel M, Heidari B, Hamidi H, RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 101999; [Google Scholar]; e) Pellissier H, Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015, 357, 2745; [Google Scholar]; f) Arshad L, Jantan I, Bukhari SNA, Haque M, Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chavan B, Gadekar A, Mehta P, Vawhal P, Kolsure A, Chabukswar A, Asian J Biomed. Pharm. 2016, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- [4] a).Chatterjee AK, Morgan JP, Scholl M, Grubbs RH, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 3783; [Google Scholar]; b) Chatterjee AK, Choi T-L, Sanders DP, Grubbs RH, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 11360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5] a).Willis MC, Chem. Rev. 2009, 110, 725; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Leung JC, Krische MJ, Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 2202; [Google Scholar]; c) Ghosh A, Johnson KF, Vickerman KL, Walker JA, Stanley LM, Org. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 639. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wang J, Liu C, Yuan JW, Lei AW, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2256; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 2312. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wu X-F, Neumann H, Spannenberg A, Schulz T, Jiao H, Beller M, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 14596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rajkiewicz AA, Kalek M, Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zhang M, Xi J, Ruzi R, Li N, Wu Z, Li W, Zhu C, J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 9305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10] a).Muzart J, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 2010, 3779; [Google Scholar]; b) Egi M, Umemura M, Kawai T, Akai S, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 12197; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 12405; [Google Scholar]; c) Diao T, Stahl SS, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14566; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Diao T, Wadzinski TJ, Stahl SS, Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 887; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Diao T, Pun D, Stahl SS, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 8205; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Zhu Y, Sun L, Lu P, Wang Y, ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 1911; [Google Scholar]; g) Huang D, Zhao Y, Newhouse TR, Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 684; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Chen M, Rago AJ, Dong G, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2018, 57, 16205; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 16437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11] a).Prier CK, Rankic DA, MacMillan DWC, Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5322; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Karkas MD, Porco JA Jr., Stephenson CR, Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 9683; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Romero NA, Nicewicz DA, Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 10075; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Skubi KL, Blum TR, Yoon TP, Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 10035; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Matsui JK, Lang SB, Heitz DR, Molander GA, ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12] a).Banerjee A, Lei Z, Ngai M-Y, Synthesis 2019, 51, 303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Raviola C, Protti S, Ravelli D, Fagnoni M, Green Chem. 2019, 21, 748. [Google Scholar]

- [13] a).Bergonzini G, Cassani C, Wallentin CJ, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 14066; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 14272; [Google Scholar]; b) Capaldo L, Riccardi R, Ravelli D, Fagnoni M, ACS Catal. 2017, 8, 304; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Stache EE, Ertel AB, Rovis T, Doyle AG, ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 11134; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Zhang M, Xie J, Zhu C, Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3517; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Li J, Liu Z, Wu S, Chen Y, Org. Lett. 2019, DOI: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00353; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Goti G, Bieszczad B, Vega‐Peñaloza A, Melchiorre P, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1213; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chatgilialoglu C, Crich D, Komatsu M, Ryu I, Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wayner D, McPhee D, Griller D, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 132. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Metternich JB, Gilmour R, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 11254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17] a).Blum TR, Miller ZD, Bates DM, Guzei IA, Yoon TP, Science 2016, 354, 1391; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Huang X, Quinn TR, Harms K, Webster RD, Zhang L, Wiest O, Meggers E, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9120; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Miller ZD, Lee BJ, Yoon TP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 11891; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 12053; [Google Scholar]; d) Lei T, Zhou C, Huang MY, Zhao LM, Yang B, Ye C, Xiao H, Meng QY, Ramamurthy V, Tung CH, Wu L-Z, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 15407; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 15609 [Google Scholar]

- [18].Petzold D, Singh P, Almqvist F, König B, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201902473; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, DOI: 10.1002/ange.201902473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [19].For seminal works on generation of aroyl radicals from aroyl chlorides under photoredox-catalyzed reaction conditions, seeLi C-G, Xu G-Q, Xu P-F, Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 512;Xu S-M, Chen J-Q, Liu D, Bao Y, Liang Y-M, Xu P-F, Org. Chem. Front. 2017, 4, 1331;Liu Y, Wang Q-L, Zhou C-S, Xiong B-Q, Zhang P-L, Yang C.-a., Tang K-W, J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 2210;Wang CM, Song D, Xia PJ, Wang J, Xiang HY, Yang H, Chem. Asian J. 2018, 13, 271.

- [20].Non-catalyzed coupling of aroyl chlorides and activated alkenes is feasible at ~200 °C, but it suffers from limited substrate scope and low product yield. Bergmann F, Israelashvili S, Gottlieb D, J. Chem. Soc. 1952, 2522. [Google Scholar]

- [21].See Supporting Information for detailed optimization tables.

- [22].Kang Y, Richers MT, Sawicki CH, Seidel D, Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 10648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].There are several potential pathways of generating HCl in the reaction mixture that lead to formation of pyridinium-HCl salts. First, the CHCl3 solvent contains ethanol (0.33 wt%) as a stabilizer, which may react with benzoyl chloride to form HCl and ethyl benzoate. Indeed, we observed the formation of ethyl benzoate in GCMS in some of the reactions. In addition, a trace amount of water may be introduced into the reaction mixture through the substrates, reagents, and solvent. This water could hydrolyse benzoyl chloride to release HCl. Finally, in some cases, we observe the formation of the enones in the reaction mixture, which liberates HCl to form pyridinium-HCl salt.

- [24] a).Tarantino KT, Liu P, Knowles RR, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 10022; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Miller DC, Tarantino KT, Knowles RR, Top. Curr. Chem. 2016, 374, 145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].The reaction favoured formation of alkene product in 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-pyridinium chloride salt because it likely catalysed conversion of chloro-product to alkene product via E1cB mechanism.

- [26].The increase in the quantum yield is likely due to the PCET process. However, the possibility of the additive minimizing the back-electron transfer cannot be neglected. For examples of organic additives minimizing the back-electron transfer, see:Masuhara H, Mataga N, Acc. Chem. Res. 1981, 14, 312;Gould IR, Ege D, Moser JE, Farid S, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 4290;Lewis FD, Bedell AM, Dykstra RE, Elbert JE, Gould IR, Farid S, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 8055;Mattay J, Vondenhof M, in Photoinduced Electron Transfer III, Springer, 1991, pp. 219; see also reference 11d.

- [27].DFT calculations showed that ΔG of the direct SET and the PCET pathways are ‒0.4 kcal/mol and ‒10.1 kcal/mol, respectively. These data suggest the favourability of the PCET mechanism as compared to the direct SET pathway.

- [28] a).Walker BJ, Wrobel PJ, J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1980, 462; [Google Scholar]; b) Adcock JL, Luo H, J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 1704; [Google Scholar]; c) Lu S-C, Wang W-X, Gao P-L, Zhang W, Tu Z-F, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Flamigni L, Barbieri A, Sabatini C, Ventura B, Barigelletti F, Top. Curr. Chem. 2007, 281, 143. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.