Abstract

Objectives

People interact with their work environment through being, to a greater or lesser extent, compatible with aspects of their setting. This interaction between person and environment is particularly relevant in healthcare settings where compatibility affects not only the healthcare professionals, but also potentially the patient. One way to examine this association is to investigate person–organisation (P-O) fit and person–group (P-G) fit. This systematic review aimed to identify and synthesise knowledge on both P-O fit and P-G fit in healthcare to determine their association with staff outcomes. It was hypothesised that there would be a positive relationship between fit and staff outcomes, such that the experience of compatibility and ‘fitting in’ would be associated with better staff outcomes.

Design

A systematic review was conducted based on an extensive search strategy guided by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analyses to identify relevant literature.

Data sources

CINAHL Complete, EMBASE, Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Scopus.

Eligibility criteria

Articles were included if they were empirical studies, published in peer-reviewed journals in English language, set in a healthcare context and addressed the association that staff outcomes have with P-O and/or P-G fit.

Data extraction and synthesis

Included texts were examined for study characteristics, fit constructs examined and types of staff outcomes assessed. The Quality Assessment Tool was used to assess risk of bias.

Results

Twenty-eight articles were included in the review. Of these, 96.4% (27/28) reported a significant, positive association between perception of fit and staff outcomes in healthcare contexts, such that a sense of compatibility had various positive implications for staff, including job satisfaction and retention.

Conclusion

Although the results, as with all systematic reviews, are prone to bias and definitional ambiguity, they are still informative. Generally, the evidence suggests an association between employees’ perceived compatibility with the workplace or organisation and a variety of staff outcomes in healthcare settings.

Keywords: organisational development, organisation of health services, human resource management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Systematic review is specific to healthcare, addressing a gap in the literature and informing healthcare professionals.

Focus is specifically on the components of person–environment fit that contribute to organisational and workplace culture in healthcare settings.

Results of this review can be leveraged to inform improvements in staff outcomes.

The body of literature is relatively small; the review may have benefited from a broader search strategy to incorporate articles that used different terminologies.

Introduction

Understanding how people fit into their environment is a key aspect to understanding organisational and workplace cultures.1–3 Research increasingly attempts to make sense of how shared attitudes, values, beliefs and practices can have downstream effects on outcomes such as productivity and staff retention.4 5 In healthcare contexts, culture holds consequences for both staff and patients.2 6 Uniquely, the presence of patients and the caring role of health providers create an important point of departure from other contexts. Thus, we need to understand how people interact with their environment and how culture improvement strategies can be more efficiently and sustainably implemented in the light of this knowledge.7–12

The person–environment (P-E) fit paradigm provides one such research avenue to further understand culture, focusing on how people perceive themselves in relation to their work environment. The P-E fit theory describes the compatibility of the individual with an aspect of their work context, for example, fit between the person and the work group (person–group (P-G) fit) or organisation (person–organisation (P-O) fit).13–15 P-E fit research measures the interacting individual and contextual factors that determine the compatibility of an individual employee with aspects of his or her environment. Components of the environment (eg, the organisation and the job) are studied separately, as it is postulated they may have different effects on staff outcomes.16 In this theory, fit is defined as a sense of belonging where (1) at least one entity (eg, the person) fulfils the needs of the other (eg, the organisation); (2) the entities share similar characteristics or (3) both 1 and 2 occur.15 Table 1 offers definitions of the commonly identified components of P-E fit (including supplementary, complementary, needs–supplies and demands–abilities fit) in the literature.

Table 1.

Important definitions of the components of person–organisation and person–group fit

| Term | Definition | Associated key terms |

| Supplementary/similarity fit | Compatibility in which the individual and the environment are congruent (eg, similar values, personality or goals)15 21 | Fit, congruence, similarity fit, compatibility |

| Complementary fit | Fit in which the individual or organisation fills a gap in, adds something unique to or ’makes whole' the other21 22 33 | Uniqueness |

| Needs–supplies fit | A feeling of fit in which the needs, inclinations or requirements of the person are fulfilled by the work environment15 88 | Supplies–values fit* |

| Demands–abilities fit | Fit in which the individual has the capabilities and capacity to meet the demands of the environment.15 | Not applicable |

Past reviews of P-E fit, although useful in highlighting the relevance of the topic, have limited utility to healthcare specifically, because of its unique siloed culture and reputation for tribalism, leading to increased burnout compared with other workplaces.1 3 6 17 Most previous reviews synthesised information from across other industries.18 While there have been quite a range of studies investigating P-E specifically in healthcare settings (such as hospitals,19 pharmaceutical distribution firms18 and elderly care facilities20) examining outcomes more typically associated with caring work (eg, burnout), these findings have not yet been rigorously synthesised.15 21–23 This could be of importance to healthcare providers, researchers and policymakers in order to more clearly understand the components of change and improvement in the organisation and workplace.

Additionally, past systematic reviews on the fit concept have tended to focus exclusively on the compatibility between employees and one element of their environment, such as the P-O or the P-G fit,15 21 23 or have alternatively examined P-E fit as a whole, without differentiation of environmental components.14 These approaches do not account for the possible interactions among different types of fit (ie, evidence suggests that employees may simultaneously experience different levels of fit with their organisation and their work group).24

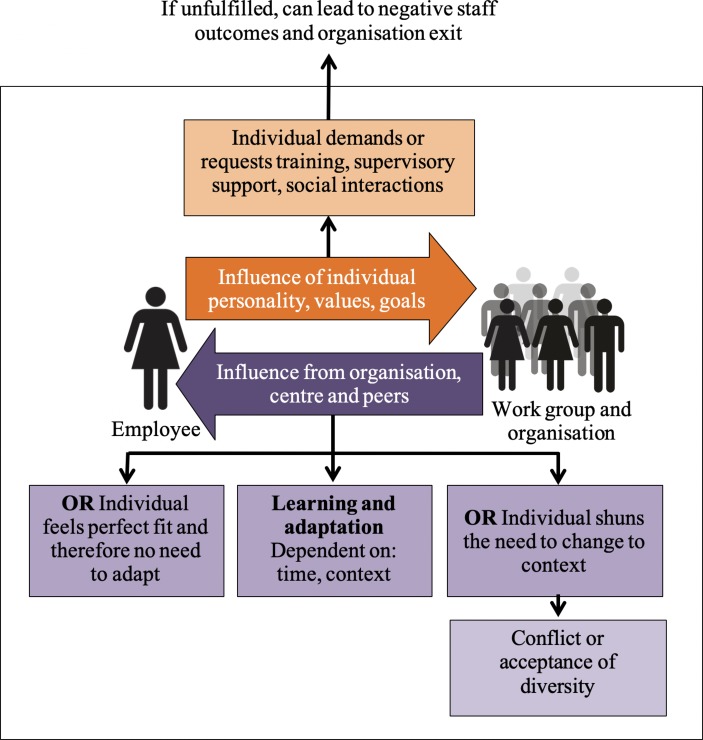

In research investigating P-E fit, one of the most important downstream effects to consider is the impact of fit perceptions on the staff themselves. Although the aim of studying organisational culture in healthcare is often ultimately to improve patient outcomes, employees are the first point of reference in attempts to alter, modify and ultimately transform organisational culture.25–32 Staff outcomes are particularly important to understand in healthcare settings because of frequent reports of employee burnout, stress, intent to leave and turnover (see figure 1 for a graphical depiction).33–37 By first understanding the factors, such as P-E fit, that influence these outcomes in healthcare settings, initiatives may be developed to improve staff well-being or reduce, for example, negative organisational cultures.25–32

Figure 1.

Rich picture modelling the process of fit and adaptation.82

In the present systematic review, available evidence for the compatibility of staff with the culture of their organisation or workplace, and the effect of this compatibility on staff outcomes is examined for the first time in healthcare settings. Because of their respective applicability to organisational and workplace cultures, it was decided that both P-O fit and P-G fit would be examined. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to identify and synthesise knowledge on both P-O fit and P-G fit in healthcare settings to determine their association with staff outcomes. It was postulated that the majority of studies would show a positive relationship between fit and staff outcomes, such that increased fit would be associated with more positive outcomes for staff.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria consisted of five points that needed to be satisfied for an article to be included in the review. These were (1) being published in English language, (2) being set in a healthcare context, (3) being published in a peer-reviewed journal, (4) being an empirical research article, and (5) ability to address the association of staff outcomes with P-O and/or P-G fit. Articles were excluded if they did not meet all five criteria. All types of ‘healthcare’ settings were eligible for inclusion in the review, encompassing any front-line clinical environment where health professionals (including medical staff, nurses, allied health professionals, paramedics and pharmacists) directly interact with patients, residents or consumers.2 Additionally, all types of empirical studies were considered, including longitudinal and cross-sectional analysis, and quantitative, qualitative and mixed-method designs. Each of these methods, if conducted in a valid and rigorous way, had the potential to provide insights by which to address the study’s aim.

Information sources

Relevant databases were identified for searching: CINAHL Complete, EMBASE, Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Scopus. The general search strategy (table 2) was cross-checked with related systematic reviews to ensure relevant keywords were incorporated.4 5 The strategy aimed to include different components within P-G fit and P-O fit. Hence, the strategy encompassed general terms (eg, ’P-O fit'), as well as more specific terms (eg, ’supplementary').15 21 The search strategy also endeavoured to identify staff outcomes, including, but not limited to, work attitude,23 38 staff satisfaction,31 burnout,27–29 work stress26 30 39 40 and organisational commitment.32

Table 2.

General search strategy

| Keyword | Related terms/synonyms | Alternative terms |

| P-O and P-G fit | Person*organisation fit OR supplementary fit OR complementary fit OR needs-supplies fit OR supplies-values fit OR demands-abilities fit OR supplementary congruence OR complementary congruence OR similarity fit OR value congruence OR goal congruence OR personality congruence OR person-group fit OR person-team fit | Organization |

| Healthcare context | Health organisation* OR hospital* OR health facilit* OR acute care OR primary care OR primary health care OR health context OR health setting OR health service OR health*care OR tertiary care OR nurse* OR health profession* OR doctor OR GP OR physician* OR dentist* OR health OR health care service* OR gyn*ecologist* OR h*ematologist* OR internist* OR obstetrician* OR p*ediatrician* OR pharmacist* OR physiotherapist* OR psychiatrist* OR psychologist* OR radiologist* OR surgeon* OR surgery OR therapist* OR counse*lor* OR neurologist* OR optometrist* | Health care Healthcare Health-care Organization |

| Staff outcomes | Burnout OR staff outcome* OR job satisfaction OR staff satisfaction OR employee satisfaction OR employee outcome* OR retention OR staff recognition OR employee recognition OR intention to stay OR intention to leave OR debrief* OR intent to turnover OR turnover intention OR organisation* commitment OR stress OR work attitude OR occupational hazard* OR collegiality OR working relationship* OR teamwork OR collaboration | Organization |

The symbol * is used by the databases to symbolise truncation.

At least one keyword was needed from each row.

The initial search was conducted on 3 April 2017 and then updated on 22 January 2019 to include articles published up to the end of 2018. The results were imported into EndNote by JH, who then deleted duplicate articles.41 Additionally, snowballing was conducted as systematic, narrative, or scoping reviews were identified and their reference lists were searched for other potential articles to include. The reference lists of included articles were subject to the same process. For the complete search strategy, please see online supplementary appendix 1.

bmjopen-2018-026266supp001.pdf (269.9KB, pdf)

Selection and data collection process

Guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement,42 an initial title and abstract review was completed by JH based on the inclusion criteria (must be published in English language, must be set in a healthcare context, must be published in a peer-reviewed journal article by the end of 2018 and must addresses the association between staff outcomes and P-O and/or P-G fit). Two authors (JH and CP) independently reviewed 10% of the EndNote Library, and then discussed results until consensus was reached.43 A full-text review was then conducted by JH. Results were summarised and synthesised. Included articles were sorted according to the data type, setting, staff outcomes measured and types of fit studied.

Data items

Information from each included study was extracted, including their aims, methods (qualitative, quantitative or mixed method; and cross-sectional or longitudinal), results and conclusions. The staff outcomes and type of fit studied were also recorded. Definitions of fit components were compared with the definitions of this systematic review, and any discrepancies were recorded.

Bias

It was anticipated that there would be biases in individual studies. The Quality Assessment Tool44 was used to assess the bias and quality across nine categories. Each category was rated on a 4-point scale (from 1=‘very poor’ to 4=‘good’) to create a total score, with higher scores denoting higher quality.6 45 For example, to receive a ‘good’ rating for the ‘abstract and title’ category, an article required a clear title and a structured abstract, including all necessary information to understand the article.44 JH classified each article to ensure consistency and to decrease variability. The classification system quality grades facilitate the categorisation of articles as low (9–23 points), medium (24–29 points) and high (30–36 points).46 There was also possible bias in the type of results published, for example, publication bias.47

Results

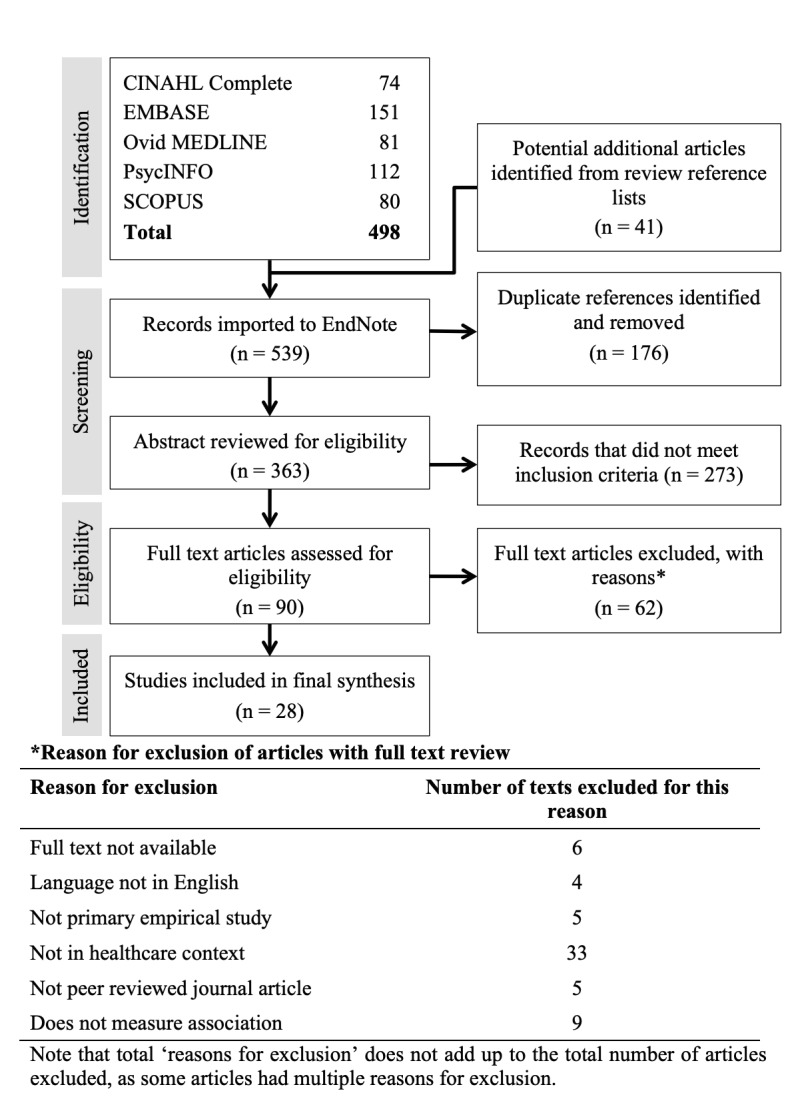

Study selection

Four hundred ninety-eight articles were identified from the database search and snowballing techniques. Once duplicates were removed, 10% of the EndNote Library was subject to the double screening by two authors with a Cohen kappa statistic of 0.61, indicating a moderate level of agreement.48 49 Two hundred seventy-three texts did not meet the inclusion criteria, and the remaining 90 articles were subjected to a full-text review (figure 2). Ultimately, 28 articles were included in the review.

Figure 2.

Search process.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Based on the Quality Assessment Tool,44 the included articles scored between 23 and 36 points out of a potential 36 points. In this study, there were 3 low-quality, 2 medium-quality and 23 high-quality articles.6 For a complete classification of each article, see online supplementary appendix 2.

Study characteristics

The articles in the final analysis originated from multiple countries, including nine from the USA,20 50–57 four from Canada,58–61 two from Spain,62 63 China64 65 and Korea,66 67 and one each from Italy,68 France,69 Germany,70 Greece,71 Turkey,72 the Netherlands,73 New Zealand,74 Norway75 and the UK.25 There were also differences in the study setting, though the largest proportion of research was conducted in hospitals (46%) (table 3).

Table 3.

Setting of included studies in systematic review

| Study setting | Included studies conducted in this context (n) |

| Hospitals | 1353 55–59 62 63 66 68 69 71 75 |

| Elderly care facilities | 420 54 70 73 |

| Acute care facilities | 161 |

| Ambulatory care | 150 |

| Disability services | 125 |

| Community health | 164 |

| No contextual information | 265 72 |

| Multiple settings | 551 52 60 67 74 |

The included studies differed in their design. Of the 28 articles, 5 were longitudinal50 53 56 70 73 and the remaining 23 were cross-sectional. The sample size varied considerably from 5675 to 19 149 participants.60 65 Additionally, the type of participants varied. The most commonly recruited participants were nurses, followed by physicians. Further information about the specific characteristics of each study is reported in online supplementary appendix 3.

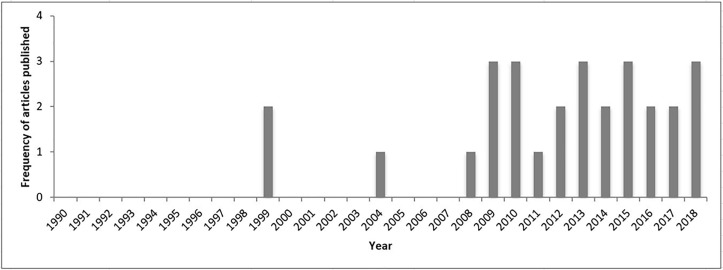

Trends in publication of the included articles provide an insight into the potential of future research examining fit in healthcare. Only 2 of the 28 included articles were published before 2000, with the majority being published after 2010 (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Trends in the frequency of published person–organisation and person–group fit research conducted in a health setting over time.

Synthesis of results

Twenty-four articles exclusively measured P-O fit, two measured P-G fit and two measured both P-O fit and P-G fit. The articles measuring P-G fit measured only supplementary value congruence. On the other hand, P-O fit articles measured various components of fit. The strength of the evidence for both P-O fit and P-G fit is examined, in turn, before discussing the inferences for fit research as a whole.

Articles measuring P-G fit

In the included studies, P-G fit, that is, the compatibility that healthcare staff members experience with their work group, was only measured through value congruence, whereby the similarity of values between the individual and the group is measured. All four articles identified in this category also measured similar staff outcomes, namely, job satisfaction52 56 72 75 and turnover intent,52 56 72 although one also measured employee attitude and time pressure.75 In all of these articles, increased value congruence was significantly positively associated with job satisfaction, and negatively associated with intention to leave the job.52 56 72 75 However, Dotson et al 52 counterintuitively reported that value congruence was positively associated with intent to leave the entire nursing profession; the authors speculated this may have been due to a lack of fulfilment of altruistic values in the nursing field, as well as external financial or bureaucratic pressures. Overall, the four studies indicated a relationship between P-G value congruence and staff outcomes, particularly a positive relationship with job satisfaction and a negative relationship with turnover intent.

Articles measuring P-O fit

In contrast with P-G fit, P-O fit, the compatibility that healthcare staff members experience with their organisation, was measured more frequently and in terms of various components of fit. Different ways of measuring some or all of the components were present in the 26 P-O fit articles (24 that solely measured P-O fit and 2 that also measured P-G fit). Table 4 reports on what authors purported to measure in their P-O fit studies.

Table 4.

Number of studies reported for each type of P-O fit

| Component of P-O fit | Studies (n)* |

| Supplementary | |

| Value | 22 |

| Personality | 2 |

| Knowledge, skills and abilities | 1 |

| Goal | 1 |

| Unspecified | 2 |

| Total | 25† |

| Complementary | 1 |

| Needs–supplies | 1 |

| Demands–abilities | 0 |

| Total studies measuring P-O fit | 26‡ |

*Studies may have reported measuring additional types of fit in different aspects of the person–environment paradigm (eg, Rehfuss et al 51 measured needs–supplies and demands–abilities person–job fit).51 These are not relevant to the aims of this systematic review and are not reported here.

†The total number of articles measuring supplementary fit does not equate to the number of studies measuring each individual component of supplementary fit, as some studies measured multiple components of supplementary fit in one study.

‡The total number of articles measuring P-O fit does not equate to the number of studies measuring each individual component, as some studies measured multiple components of P-O fit in one study.

P-O, person–organisation.

Supplementary fit was the most commonly measured component of P-O fit in healthcare literature.14 15 76 77 P-O supplementary value congruence was measured in 22 studies. Eight articles measured value congruence through the Areas of Worklife Scale,78 where ‘values’ was one of six components the scale measured.50 56 58–61 63 65 68 Consequently, ‘fit’ or ‘compatibility’ was not the main focus of these articles, but they still reported the correlations with outcomes, including burnout,50 58–61 63 turnover intent61 and job satisfaction,57 in a variety of healthcare settings, including hospitals57–59 63 and acute care facilities.61 The remaining survey tools measuring P-O value congruence were heterogeneous, with five studies51 62 67 69 73 using the Perceived Fit Scale from Cable and DeRue,79 four studies deriving their survey questions from other sources,55 62 65 66 71 and five studies using tools crafted specifically for that study.20 52–54 72 The heterogeneity of tools and study contexts made it difficult to compare across studies. However, these studies collectively suggested there are several valid ways to measure P-O supplementary value fit and its associations with staff outcomes.

Personality congruence was measured in two studies, one of which also measured knowledge, skills and abilities (KSA) congruence. Cha et al 66 measured personality congruence under the heading of ‘prosocial P-O fit’, whereby high scores on personal and prosocial identities (in other words, high personality congruence) was associated with higher organisational citizenship and caring behaviour from hospital employees. However, they reported an unexpected link between the misfit of the person and organisation with prosocial behaviour, such that individuals would be intrinsically motivated to engage in these behaviours even if the organisation did not actively encourage them. Similarly, the study measuring P-O KSA and personality congruence found that the overall measure of P-O fit was significantly associated with both job satisfaction and turnover intention.72 However, personality and KSA congruence were not analysed separately, so there was not enough evidence to deduce individual associations between each of these types of fit and staff outcomes.

Supplementary goal congruence was measured in one study of job strain among aged care workers, where Schmidt70 found that goal incongruence was related to absenteeism and self-reported burnout. As there was only one study on goal congruence, it was difficult to draw conclusions regarding this particular component of supplementary fit.

Two studies did not specify the aspect of supplementary fit that they measured. Hatton et al 25 used an ‘ideal–real’ organisational culture tool to test the congruence between employees' perceptions of their organisation compared with those of an ‘ideal’ organisation. It could not be determined from the original scale which component or components of supplementary fit were examined. The second study measuring an unspecified component of supplementary fit was also the sole article reporting a measure of complementary fit. Reportedly, each fit component (supplementary and complementary) was measured through four items.74 However, on review of the original survey items, it became apparent that the complementary fit scale consisted of items that would be defined as different elements of fit (needs–supplies and supplementary).80 This combination of items made it difficult to draw theoretical conclusions from the study. Although general complementary fit itself was not measured, this article indicates the potential importance of needs–supplies P-O fit.

Zhang et al 64 reported that needs–supplies P-O fit was directly associated with job satisfaction, as well as significantly inversely associated with intent to leave among community health workers in China. These results aligned with those of Cooper-Thomas et al,74 who reported a significant positive correlation of P-O fit with job satisfaction and organisational commitment, and a negative correlation with intention to quit. Moreover, both studies reported that job satisfaction partially mediated the relationship between needs–supplies P-O fit and intention to quit.

Articles measuring P-O fit and P-G fit

There was a dearth of research examining P-O fit and P-G fit together in healthcare, limiting knowledge regarding their relationship. Of the two articles purporting to measure both P-O fit and P-G fit, it appeared that, based on the items used, one rigorously measured only P-O fit,72 and the other did not delve into the fit framework but rather measured P-O fit and P-G value congruence.52 As such, it was not possible to draw any reasonable conclusions on the potential interactional effect between P-O fit and P-G fit on staff outcomes in health environments. This indicates the importance of definitional consistency in fit research.

Staff outcomes measured

In addition to the variability among the type of fit studied, there was also a variation in the staff outcomes measured. The main types of outcomes included satisfaction, intention to quit, organisational commitment, burnout and absenteeism (table 5).

Table 5.

Staff outcomes assessed in the studies included in this review

| Term | Alternative terms | Included articles measuring and recording this outcome* |

| Satisfaction | Job satisfaction, work satisfaction, career satisfaction | 17 |

| Intention to quit | Turnover intent, intention to stay, job search behaviour, intent to leave job, intent to leave profession, actual turnover | 16 |

| Organisational commitment | Loyalty, organisational citizenship behaviour,† caring behaviour | 10 |

| Burnout | N.A. | 10 |

| Stress | Time pressure, job stress, psychosomatic complaints | 4 |

| Absenteeism | Sick leave behaviour | 4 |

| Other | For example, self-rated health, accident propensity, employee attitude | 3 |

*The total of this column does not equate to the total number of included articles, as some studies measured outcomes from more than one column.

†Organisational citizenship behaviour is defined as voluntary actions undertaken by an employee and directed towards individuals or organisations. The actions may not be rewarded, but they contribute to the work environment.66

Overall findings

Overall, 96.4% of included articles (27/28) reported a significant, positive relationship between P-O or P-G fit and staff outcomes, such that greater compatibility with one’s workplace or organisation was associated with more positive outcomes for staff (eg, lower levels of burnout and increased satisfaction). Of these, 22 articles reported an exclusively positive relationship, showing that the relationship between fit and each measured staff outcome was in the direction hypothesised. Five further articles reported a partially positive relationship; in other words, some staff outcomes had a significant association with fit in the direction hypothesised, but the association with other outcomes did not reach a level of statistical significance (eg, a reported positive association between measures of fit and job satisfaction and loyalty, but no association with turnover).71 Finally, one article reported no significant association between the two entities (namely, P-O value fit and actual turnover).73

Discussion

The results of this review provided robust evidence for the initial postulation that stronger P-O fit, and to a lesser extent P-G fit, would be associated with more positive outcomes, such as organisational commitment and job satisfaction, and decreased intent to quit, burnout and stress. Even with a relatively small number of P-G fit articles compared with P-O fit articles, the trend across the results suggests the importance of both constructs in increasing individuals’ perception of fit, and that this is conducive to better outcomes for staff working in healthcare. Hence, this review highlights the importance for people’s well-being of feeling a sense of fit with both their work group and their wider organisation, a result that confirms previous results from systematic reviews not conducted in healthcare.15 81 Specifically, evidence suggests the importance of similar values between individuals and their workplace and organisation.20 52 54–56 60 75 Not only may this have positive downstream effects on the employees themselves, but also it has the potential to positively impact on the outcomes they produce in the work environment, which, in healthcare, equates to better patient care.6

Research regarding the process of individual adaptation to the work context is growing,82 83 which will add richness to the understanding of how to most effectively foster perceived fit and improve cultures in healthcare settings. This review will, we hope, offer welcome guidance to policymakers, managers and other custodians of organisational culture in healthcare on the importance of enhancing fit perceptions between individuals and their work environments. Ultimately, such strategies aim to increase mutually beneficial fit at work.

The results have important implications for clinicians, allied health professionals, healthcare managers and policymakers involved in the development and implementation of culture change interventions. Most apparently, they suggest the importance of individuals being motivated to seek work at organisations that hold values and goals similar to their own.52 84 Alternatively, in the case of employed individuals being incompatible with the workplace or organisation, the results suggest the importance of bridging this gap.85–87 The systematic review is the first in the context of healthcare to highlight the mutual benefit of adaptation and flexibility of both the individual and the environment, in order to create better fit between healthcare staff and the places they work, which may also potentially improve patient care.

Strengths and limitations

There are several strengths and limitations to this study. The review searched multiple databases and was thorough and rigorous, applying PRISMA methodology and assessing bias and quality. Bias is unavoidable, and thus readers should be mindful of this potential bias when judging the strength of evidence of the association between P-O fit and P-G fit with staff outcomes. Additionally, the included articles were inconsistent and heterogeneous in their labelling and measuring of fit. For example, some articles measured value congruence but did not explain the wider concept of supplementary fit,58 63while others specified this information.51 73 This meant we had to make some choices regarding the identification and grouping of articles for this review. In the future, empirical studies of P-O fit and P-G fit in health settings could address these limitations by explicitly identifying what facet of fit they are studying and linking this to their measurement tool.

Conclusion

The results of this systematic review indicate that fitting in at work is conducive to improved staff outcomes in healthcare. The results argue in favour of the intrinsic benefit of improving staff well-being. However, the approach on how to best enhance organisational cultures in order to therefore have downstream effects on employees' productivity and quality of work remains unclear.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JH conceptualised and drafted the manuscript. JH, KC and CP were involved in the search strategy and data extraction. KC, LAE and JB edited the manuscript and critically reviewed its intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: JH was funded by a Research Training Program Master of Research stipend scholarship at Macquarie University. JB is supported by multiple NHMRC Council grants.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and public were not involved in this research.

References

- 1. Braithwaite J. A lasting legacy from Tony Blair? NHS culture change. J R Soc Med 2011;104:87–9. 10.1258/jrsm.2010.100364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Braithwaite J, Herkes J, Ludlow K, et al. Association between organisational and workplace cultures, and patient outcomes: systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e013758 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Braithwaite J, Hyde P, Pope C. Culture and Climate in Health Care Organizations. Basingstoke, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parmelli E, Flodgren G, Beyer F, et al. The effectiveness of strategies to change organisational culture to improve healthcare performance: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2011;6:1–8. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. MacDavitt K, Chou SS, Stone PW. Organizational climate and health care outcomes. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2007;33:45–56. 10.1016/S1553-7250(07)33112-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Braithwaite J, Herkes J, Ludlow K, et al. Association between organisational and workplace cultures, and patient outcomes: systematic review. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017708 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Higgins J, Altman D, Sterne J. Chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in included studies : Higgins J, Green S, Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 510: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Larson EL, Early E, Cloonan P, et al. An organizational climate intervention associated with increased handwashing and decreased nosocomial infections. Behav Med 2000;26:14–22. 10.1080/08964280009595749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nosrati H, Clay-Williams R, Cunningham F, et al. The role of organisational and cultural factors in the implementation of system-wide interventions in acute hospitals to improve patient outcomes: protocol for a systematic literature review. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002268 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sacks GD, Shannon EM, Dawes AJ, et al. Teamwork, communication and safety climate: a systematic review of interventions to improve surgical culture. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:458–67. 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beer M, Nohria N. Cracking the code of change. Harv Bus Rev 2000;78:133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Isouard G. Leading and managing the implementation process: the key to successful national health reform. APJHM 2010;5:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morley M. Person-organization fit. J Manag Managerial Psychology 2007;22:109–17. 10.1108/02683940710726375 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kristof-Brown A, Guay R. Person-environment fit Zedeck S, APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Maintaining, Expanding, and Contracting the Organization. 3: American Psychological Association, 2011. –3. [Google Scholar]

- 15. KRISTOF AMYL. Person-organization fit: an integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers Psychol 1996;49:1–49. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1996.tb01790.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chatman JA. Improving interactional organizational research: a model of person-organization fit. Acad Manage Rev 1989;14:333–49. 10.5465/amr.1989.4279063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Braithwaite J, Clay-Williams R, Vecellio E, et al. The basis of clinical tribalism, hierarchy and stereotyping: a laboratory-controlled teamwork experiment. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012467 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cennamo L, Gardner D. Generational differences in work values, outcomes and person‐organisation values fit. Journal of Managerial Psychology 2008;23:891–906. 10.1108/02683940810904385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Parkes L, Bochner S, Schneider S. Person-organisation fit across cultures: an empirical investigation of individualism and collectivism. Appl Psychol 2001;50:81–108. 10.1111/1464-0597.00049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ren T, Hamann DJ. Employee value congruence and job attitudes: the role of occupational status. Personnel Review 2015;44:550–66. 10.1108/PR-06-2013-0096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Piasentin KA, Chapman DS. Subjective person–organization fit: Bridging the gap between conceptualization and measurement. J Vocat Behav 2006;69:202–21. 10.1016/j.jvb.2006.05.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Santos LBdos, De Domenico SMR. Person-organization fit: bibliometric study and research agenda. European Business Review 2015;27:573–92. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Verquer ML, Beehr TA, Wagner SH. A meta-analysis of relations between person–organization fit and work attitudes. J Vocat Behav 2003;63:473–89. 10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00036-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vogel RM, Feldman DC. Integrating the levels of person-environment fit: The roles of vocational fit and group fit. J Vocat Behav 2009;75:68–81. 10.1016/j.jvb.2009.03.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hatton C, Rivers M, Mason H, et al. Organizational culture and staff outcomes in services for people with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res 1999;43:206–18. 10.1046/j.1365-2788.1999.00190.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Edwards D, Burnard P, Coyle D, et al. Stress and burnout in community mental health nursing: a review of the literature. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2000;7:7–14. 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2000.00258.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fong TCT, Ho RTH, Au-Yeung FSW, et al. The relationships of change in work climate with changes in burnout and depression: a 2-year longitudinal study of Chinese mental health care workers. Psychol Health Med 2016;21:401–12. 10.1080/13548506.2015.1080849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kilroy A, Flood P, Bosak J, et al. Perceptions of high-involvement work practices, person-organization fit, and burnout: a time-lagged study of health care employees. Hum Resour Manage 2016:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav 1981;2:99–113. 10.1002/job.4030020205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shinn M, Rosario M, Mørch H, et al. Coping with job stress and burnout in the human services. J Pers Soc Psychol 1984;46:864–76. 10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen P, Sparrow P, Cooper C. The relationship between person-organization fit and job satisfaction. Journal of Managerial Psychology 2016;31:946–59. 10.1108/JMP-08-2014-0236 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kinjerski V, Skrypnek BJ. The promise of spirit at work: increasing job satisfaction and organizational commitment and reducing turnover and absenteeism in long-term care. J Gerontol Nurs 2008;34:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Piasentin KA, Chapman DS. Perceived similarity and complementarity as predictors of subjective person-organization fit. J Occup Organ Psychol 2007;80:341–54. 10.1348/096317906X115453 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Grunfeld E, Whelan TJ, Zitzelsberger L, et al. Cancer care workers in Ontario: prevalence of burnout, job stress and job satisfaction. CMAJ 2000;163:166–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chew J, Chan CCA. Human resource practices, organizational commitment and intention to stay. Int J Manpow 2008;29:503–22. 10.1108/01437720810904194 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gould-Williams JS, Mostafa AMS, Bottomley P. Public Service Motivation and Employee Outcomes in the Egyptian Public Sector: Testing the Mediating Effect of Person-Organization Fit. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 2015;25:597–622. 10.1093/jopart/mut053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mostafa AMS, Gould-Williams JS. Testing the mediation effect of person–organization fit on the relationship between high performance HR practices and employee outcomes in the Egyptian public sector. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2014;25:276–92. 10.1080/09585192.2013.826917 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Warr P, Cook J, Wall T. Scales for the measurement of some work attitudes and aspects of psychological well-being. Journal of Occupational Psychology 1979;52:129–48. 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1979.tb00448.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ramirez AJ, Graham J, Richards MA, et al. Mental health of hospital consultants: the effects of stress and satisfaction at work. Lancet 1996;347:724–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90077-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ward L. Mental health nursing and stress: maintaining balance. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2011;20:77–85. 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00715.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Analytics C. Endnote.

- 42. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, et al. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res 2002;12:1284–99. 10.1177/1049732302238251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Taylor N, Clay-Williams R, Hogden E, et al. High performing hospitals: a qualitative systematic review of associated factors and practical strategies for improvement. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:244–66. 10.1186/s12913-015-0879-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Whitehead M, et al. Appendix 5: quality assessment for the systematic review of qualitative evidence. Crime, Fear of Crime and Mental Health: Synthesis of Theory and Systematic Reviews of Interventions and Qualitative Evidence. Southampton, UK: NIHR Journals Library, 2014. Public Health Research, No. 2.2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dickersin K. The existence of publication bias and risk factors for its occurrence. JAMA 1990;263:1385–9. 10.1001/jama.1990.03440100097014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Byrt T, Bishop J, Carlin JB. Bias, prevalence and kappa. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:423–9. 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90018-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med 2012;22:276–82. 10.11613/BM.2012.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gregory ST, Menser T. Burnout among primary care physicians: a test of the areas of worklife model. J Healthc Manag 2015;60:133–48. 10.1097/00115514-201503000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rehfuss MC, Gambrell CE, Meyer D. Counselors' Perceived Person-Environment Fit and Career Satisfaction. Career Dev Q 2012;60:145–51. 10.1002/j.2161-0045.2012.00012.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dotson MJ, Dave DS, Cazier JA, et al. An empirical analysis of nurse retention. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration 2014;44:111–6. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Somers MJ. Patterns of attachment to organizations: Commitment profiles and work outcomes. J Occup Organ Psychol 2010;83:443–53. 10.1348/096317909X424060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ren T. Sectoral differences in value congruence and job attitudes: the case of nursing home employees. Journal of Business Ethics 2013;112:213–24. 10.1007/s10551-012-1242-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kalliath TJ, Bluedorn AC, Strube MJ. A test of value congruence effects. J Organ Behav 1999;20:1175–98. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gates MG, Mark BA, diversity D. value congruence, and workplace outcomes in acute care. Res Nurs Health 2012;35:265–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Risman KL, Erickson RJ, Diefendorff JM. The Impact of Person-Organization Fit on Nurse Job Satisfaction and Patient Care Quality. Appl Nurs Res 2016;31:121–5. 10.1016/j.apnr.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Leiter MP, Day A, Price L. Attachment styles at work: Measurement, collegial relationships, and burnout. Burn Res 2015;2:25–35. 10.1016/j.burn.2015.02.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Leiter MP. A two process model of burnout and work engagement: distinct implications of demands and values. G Ital Med Lav Ergon 2008;30(1 Suppl A):A52–A8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Leiter MP, Frank E, Matheson TJ. Demands, values, and burnout: relevance for physicians. Can Fam Physician 2009;55:1224–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Leiter MP, Jackson NJ, Shaughnessy K. Contrasting burnout, turnover intention, control, value congruence and knowledge sharing between Baby Boomers and Generation X. J Nurs Manag 2009;17:100–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00884.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bao Y, Vedina R, Moodie S, et al. The relationship between value incongruence and individual and organizational well-being outcomes: an exploratory study among Catalan nurses. J Adv Nurs 2013;69:631–41. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06045.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Leiter MP, Gascón S, Martínez-Jarreta B. Making sense of work life: a structural model of burnout. J Appl Soc Psychol 2010;40:57–75. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00563.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhang M, Yan F, Wang W, et al. Is the effect of person-organisation fit on turnover intention mediated by job satisfaction? A survey of community health workers in China. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013872 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Shao J, Tang L, Wang X, et al. Nursing work environment, value congruence and their relationships with nurses' work outcomes. J Nurs Manag 2018;26:1091–9. 10.1111/jonm.12641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cha J, Chang YK, Kim T-Y. Person–organization fit on prosocial identity: implications on employee outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics 2014;123:57–69. 10.1007/s10551-013-1799-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lee S, Jang E. The relationships of person-organization fit and person-job fit with work attitudes: A moderating effect of person-supervisor fit. Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 2017;12:3767–78. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lamiani G, Dordoni P, Argentero P. Value congruence and depressive symptoms among critical care clinicians: The mediating role of moral distress. Stress Health 2018;34:135–42. 10.1002/smi.2769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gillet N, Fouquereau E, Coillot H, et al. The effects of work factors on nurses' job satisfaction, quality of care and turnover intentions in oncology. J Adv Nurs 2018;74:1208–19. 10.1111/jan.13524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Schmidt KH. The relation of goal incongruence and self-control demands to indicators of job strain among elderly care nursing staff: a cross-sectional survey study combined with longitudinally assessed absence measures. Int J Nurs Stud 2010;47:855–63. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bellou V. Matching individuals and organizations: evidence from the Greek public sector. Employee Relations 2009;31:455–70. 10.1108/01425450910979220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Findik M, Öǧüt A, Çaǧliyan V. An evaluation about person-organization fit, job satisfaction, and turnover intention: a case of health institution. Mediterr J Soc Sci 2013;4:434–40. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Boon C, Biron M. Temporal issues in person-organization fit, person-job fit and turnover: The role of leader-member exchange. Hum Relat 2016;69:2177–200. 10.1177/0018726716636945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Cooper-Thomas HD, Poutasi C. Attitudinal variables predicting intent to quit among Pacific healthcare workers. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 2011;49:180–92. 10.1177/1038411111400261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Verplanken B. Value congruence and job satisfaction among nurses: a human relations perspective. Int J Nurs Stud 2004;41:599–605. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2003.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Guan Y, Deng H, Risavy S, et al. Supplementary fit, complementary fit, and work-related outcomes: the role of self-construal. Appl Psychol Int Rev 2010;60. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Mehtap Özge, Alnıaçık E. Can Dissimilar be Congruent as well as the Similar? A Study on the Supplementary and Complementary Fit. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2014;150:1111–9. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Leiter MP, Maslach C. Areas of worklife: a structured approach to organizational predictors of job burnout. Emotional and Physiological Processes and Positive Intervention Strategies: Research in Occupational Stress and Well Being: Elsevier Ltd, 2004:91–134. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Cable DM, DeRue DS. The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J Appl Psychol 2002;87:875–84. 10.1037/0021-9010.87.5.875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Saks AM, Ashforth BE. Is job search related to employment quality? It all depends on the fit. J Appl Psychol 2002;87:646–54. 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. KRISTOF-BROWN AMYL, ZIMMERMAN RD, JOHNSON EC. Consequences of individuals' fit at work: a meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Pers Psychol 2005;58:281–342. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Ellis LA. Coordinating care across boundaries in mental health facilities: a qualitative approach to understanding perceptions of fit at work. Organ Behav Health Care 2018:13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ryan A, Kristof-Brown A. Focusing on personality in person-organization fit research: unaddressed issues : Barrick M, Ryan A, Personality and Work: Reconsidering the Role of Personality in Organizations. 1st edn San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2003:262–88. [Google Scholar]

- 84. McDonald P, Gandz J. Getting value from shared values. Organ Dyn 1992;20:64–77. 10.1016/0090-2616(92)90025-I [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Judge T, Cable D, personality A. organizational culture, and organization attraction. Pers Psychol 1997;50:359–94. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Lievens F, Decaesteker C, Coetsier P, et al. Organizational Attractiveness for Prospective Applicants: A Person-Organisation Fit Perspective. Appl Psychol 2001;50:30–51. 10.1111/1464-0597.00047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87. SAKS AM, ASHFORTH BE. A longitudinal investigation of the relationships between job information sources, applicant perceptions of fit, and work outcomes. Pers Psychol 1997;50:395–426. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1997.tb00913.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Yu KYT, Davis HM. Autonomy’s impact on newcomer proactive behaviour and socialization: A needs-supplies fit perspective. J Occup Organ Psychol 2016;89:172–97. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026266supp001.pdf (269.9KB, pdf)