Abstract

Introduction

The European population is rapidly ageing. In order to handle substantial future challenges in the healthcare system, we need to shift focus from treatment towards health promotion. The PreventIT project has adapted the Lifestyle-integrated Exercise (LiFE) programme and developed an intervention for healthy young older adults at risk of accelerated functional decline. The intervention targets balance, muscle strength and physical activity, and is delivered either via a smartphone application (enhanced LiFE, eLiFE) or by use of paper manuals (adapted LiFE, aLiFE).

Methods and analysis

The PreventIT study is a multicentre, three-armed feasibility randomised controlled trial, comparing eLiFE and aLiFE against a control group that receives international guidelines of physical activity. It is performed in three European cities in Norway, Germany, and The Netherlands. The primary objective is to assess the feasibility and usability of the interventions, and to assess changes in daily life function as measured by the Late-Life Function and Disability Instrument scale and a physical behaviour complexity metric. Participants are assessed at baseline, after the 6 months intervention period and at 1 year after randomisation. Men and women between 61 and 70 years of age are randomly drawn from regional registries and respondents screened for risk of functional decline to recruit and randomise 180 participants (60 participants per study arm).

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was received at all three trial sites. Baseline results are intended to be published by late 2018, with final study findings expected in early 2019. Subgroup and further in-depth analyses will subsequently be published.

Trial registration number

NCT03065088; Pre-results.

Keywords: physical activity, muscle strength, balance, mobile health units, functional decline, behaviour change

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Adapted LiFE integrates individualised and appropriately challenging balance, muscle strength and physical activities into daily lives of young older adults.

Enhanced LiFE uses a smartphone/smartwatch app to offer a personalised lifestyle-integrated activity programme, based on a risk screening of future functional decline and an individual’s physical performance.

Technology-supported exercise programme allows participants to monitor their behaviour and receive messages and feedback in real time aiming to change their physical behaviour.

The 12-month follow-up enables monitoring and evaluation of long-term adherence to smartphone-based and paper-based interventions.

Potential sources of bias include the selection of participants and loss to follow-up if those who complete the full data collection protocol are systematically different between the three groups.

Background

The European population is rapidly ageing. Average life expectancy has exceeded 80 years across Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries,1 with a concomitant increase in projected years spent with disabilities.2 In order to tackle future challenges on already overstretched healthcare systems, it is generally recognised that there needs to be shift of focus from treatment towards promoting active and healthy ageing and prevention of age-related diseases and functional decline.3

It is well documented that physical activity (PA) improves health and physical function and reduces disability at old age.4 Increasing PA4 as well as balance5 and strength5 training have been described as determinants for maintaining function and ability. According to the WHO, physical inactivity is the fourth leading risk factor contributing to death worldwide and increases the risk of adverse health outcomes, such as shortened life expectancy, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer.6 Older adults are at increased risk of physical inactivity, with significant decline in activity levels occurring around the time of retirement.7 Simultaneously, this period of life provides the opportunity to adopt a healthy and active lifestyle, as there is still potential to prevent decline and maintain physical function required to remain active and independent in later life.8

In order to shift from an inactive to an active lifestyle, behaviour change is needed. However, uptake of and adherence to PA interventions is a challenge, as shown, for example, in fall prevention9 and evidence-based strength and balance programmes in older adults.10 Previous studies demonstrated that high intervention adherence rates can achieve statistically significant and clinically relevant treatment effects.11 However, participants’ activity levels often revert back to previous low activity levels at the end of the intervention period,12 13 indicating that interventions must be supported by behavioural change, be acceptable and be based on theoretical and empirically tested principles.12 14 15

The PreventIT project (Early risk detection and prevention in ageing people by self-administered ICT-supported assessment and a behavioural change intervention, delivered by use of smartphones and smartwatches) is a European Horizon 2020 Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and personal health project. The aim is to develop and test a personalised behaviour change intervention on PA aimed at young older adults that has the potential to prevent accelerated functional decline at older age.16

PreventIT is based on the Lifestyle-integrated Exercise (LiFE) programme developed by Clemson et al.17 In LiFE, balance and muscle strengthening activities are embedded within everyday activities. Rather than using a prescribed set of exercises, LiFE activities occur whenever the opportunity for such activity arises during the day. The original LiFE programme was developed for adults 70 years and older and tested in older home-dwelling people. It was found to significantly reduce falls, improve physical function, decrease disability and improve adherence, compared with a traditional exercise programme and a sham intervention.18 Thus, tailoring exercise at an individual level and integrating it in daily life seems to be a promising approach.

In accordance with the UK Medical Research Council guidance19 on development, evaluation and implementation of complex interventions, the original LiFE programme was customised to the needs of a younger target group. The PreventIT consortium adapted and piloted the LiFE activities in order to make them adequately challenging, complex and meaningful for a younger target population (adapted LiFE, aLiFE) (paper submitted).20 21 In addition, the consortium further developed the behavioural change elements of the intervention,22 mapping these to behaviour change theory and techniques (table 1).23 Iterative stages of feasibility testing and evaluation of the aLiFE programme were applied including a proof of concept pilot study (ISRCTN37750605; https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN37750605). Subsequently, the aLiFE programme was transferred to a mobile health application system (PreventIT mHealth system),24 called enhanced LiFE (eLiFE) programme, delivering the intervention on smartphones and smartwatches.

Table 1.

Behaviour change techniques adopted within aLiFE and eLiFE

| Behaviour change techniques* | aLiFE content | eLiFE content |

| 1. Goals and planning | ||

| 1.1 Goal setting (behaviour—which activities, where and how often) | Daily routine chart, activity planner | App content (planning screens), instructor |

| 1.2 Problem solving | Manual, instructor | App content, instructor |

| 1.3 Goal setting (outcome—long term) | Paper form, instructor | App content (planning screens), instructor |

| 1.4 Action planning | Activity planner, instructor | App content (planning screens), instructor |

| 1.5 Review behavioural goals | Activity planner, activity counter | App content (daily reporting) |

| 1.6 Discrepancy between current behaviour and goal | Paper form, activity planner | App content (motivational messaging, activity reporting) |

| 1.7 Review outcome goals | Paper form, activity planner, activity counter, instructor | App content (motivational messaging, activity reporting) |

| 2. Feedback and monitoring | ||

| 2.2 Feedback on behaviour | Instructor | App content (real-time feedback) |

| 2.3 Self-monitoring of behaviour | Activity planner, activity counter | App content (activity reporting) |

| 2.4 Self-monitoring of outcomes of behaviour | Activity planner, activity counter | App content (motivational messaging) |

| 2.6 Biofeedback | Not included | System components (accelerometer) and app content (feedback screens) |

| 2.7 Feedback on outcomes of behaviour | Instructor | App content (real-time feedback) |

| 3. Social support | ||

| 3.1 Social support | Instructor | App content (motivational messaging) |

| 4. Shaping knowledge | ||

| 4.1 Instruction on how to perform the behaviour | Manual, instructor | App content (text, pictures, videos) |

| 5. Natural consequences | ||

| 5.1 Information about health consequences | Manual | App content (motivational messaging) |

| 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences | Manual | App content (motivational messaging) |

| 6. Comparison of behaviour | ||

| 6.1 Demonstrate the behaviour | Manual (text, pictures), instructor | App content (text, pictures, videos) |

| 6.2 Social comparison | Not included | App content (motivational messaging) |

| 6.3 Information about others’ approval | Not included | App content (motivational messaging) |

| 7. Associations | ||

| 7.1 Prompts/cues | Manual, instructor | App content (planning screens) |

| 8. Repetition and substitution | ||

| 8.1 Behavioural practice/rehearsal | Manual, instructor | App content (planning screens, real-time feedback, motivational messaging) |

| 8.3 Habit formation | Manual, instructor, activity planner, activity counter | App content (planning screens, real-time feedback, motivational messaging) |

| 8.6 Generalisation of a target behaviour | Manual, instructor, daily routine chart, activity planner | App content (motivational messaging) |

| 8.7 Graded tasks | Manual, instructor | App content (planning screens, real-time feedback, motivational messaging) |

| 10. Reward and threat | ||

| 10.10 Reward (outcome) | Instructor | App content (real-time feedback, motivational messaging) |

| 10.3 Non-specific reward | Instructor | App content (real-time feedback, motivational messaging) |

| 12. Antecedents | ||

| 12.1 Restructuring the physical environment | Manual, instructor | App content (planning screens, motivational messaging) |

| 12.2 Restructuring the social environment | Manual, instructor | App content (planning screens, motivational messaging) |

| 15. Self-belief | ||

| 15.1 Verbal persuasion about capability | Not included | App content (motivational messaging) |

| 15.3 Focus on past success | Not included | App content (motivational messaging) |

*Using Michie et al.23

aLiFE, adapted LiFE; eLiFE, enhanced LiFE.

In order to assess feasibility and usability, evaluate and further improve the intervention, and to suggest sample size and design for a future phase III clinical trial, this feasibility study is currently being conducted, comparing eLiFE and aLiFE interventions with a control group.

Aims

The aim of the multicentre randomised controlled feasibility trial is to assess the feasibility of eLiFE and aLiFE programmes, integrating activities into daily life, versus a control group, targeting young older adults between 61 and 70 years. There are five main research questions: (1) Participation: What are the levels of adherence of young older adults to specific activities and to the entire eLiFE and aLiFE intervention over the course of the study period? (2) Technology: What is the acceptability of the eLiFE intervention delivered using technology (smartphones and smartwatches) including user interface, goal setting, feedback, motivational messages and social interaction? (3) Feasibility and usability: What is the feasibility of the eLiFE and aLiFE intervention programmes in a cohort of young older adults: What are the possible harms (adverse events) of the eLiFE or aLiFE intervention? What is the acceptability of eLiFE and aLiFE activities (usefulness, safety, difficulty level, adaptability/personalisation, planning and uptake of exercises)? Are the randomised controlled trial (RCT) methods suitable (recruitment, randomisation, follow-up, outcomes, and so on)? (4) Estimates of change: What is the change in function, as measured by two primary clinical outcome measures: the Late-Life Function and Disability Instrument (LLFDI) and the behavioural complexity metric, for the eLiFE and the aLiFE interventions compared with the control group? What are the estimated effect sizes for LLFDI, complexity metric and the secondary clinical outcome measures? (5) Health economics evaluation: Is it feasible to collect data in order to estimate healthcare resource utilisation, costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALY), and model incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICER) of aLiFE and eLiFE compared with the control group over a 6-month and 12-month time period?

Methods

Trial design

The study uses a three-arm RCT design, performed at three clinical sites including a total of 180 participants (60 participants at each site; 20 participants in each arm per site). Inclusion of participants started in March 2017 with a 6-month intervention period and 12-month follow-up from baseline lasting until August 2018.

Study setting and test procedures

The three participating study sites are Trondheim, Norway; Amsterdam, The Netherlands; and Stuttgart, Germany. Telephone screening, risk screening, medical assessment as well as three on-site assessments (T1, T2, T3) are undertaken in university facilities (Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) Trondheim and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam) and academic hospital (Robert Bosch Krankenhaus, Stuttgart). All other participant contact is through home visits or telephone communication. Participants are assessed at baseline (T1) within 6 weeks of initial screening, post-test (T2) 182 days after the first home visit (±2 weeks) and follow-up after 12 months (T3) (364 days±4 weeks after the first home visit). Trained assessors (blinded to group allocation) perform all assessments at the collaborating centres. Each assessment lasts approximately 1.5–2.5 hours.

Eligibility criteria

Persons born between 1 January 1947 and 31 December 1956 (61–70 years of age at start of recruitment) were invited to participate via mail. Persons within the target group were randomly selected from three local population registries (the National Registry in Norway, the Municipality Registry of Amsterdam and the Stuttgart Registry in Germany). The inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in table 2. Eligibility for participation is determined through a telephone interview, a risk screening for functional decline and a medical screening. Rates of eligibility at each stage of the inclusion process are monitored.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

| Telephone screening | Between 61 and 70 years of age | Current participation in an organised exercise class >1 per week |

| Retired (more than 6 months, <50% paid/unpaid work) | Moderate-intensity physical activity ≥150 min/week in the previous 3 months | |

| Community dwelling | Travels >2 months planned during intervention period | |

| Able to read a newspaper or text on a smartphone | ||

| Speaks Norwegian/Dutch/German | ||

| Able to walk 500 m without walking aid | ||

| Available for home visits the following 6 weeks | ||

| Risk screening | ‘At risk’ for functional decline | Cognitive impairment (Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) <24 points) |

| Acute depression (STU and AMS) | ||

| Medical screening | Medical condition (heart failure New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III and IV) | |

| Acute myocardial infarction last 6 months or unstable angina | ||

| Pericarditis, myocarditis, endocarditis in the last 6 months | ||

| Symptomatic aortic stenosis; cardiomyopathy | ||

| Resting blood pressures of a systolic >180 mm Hg or diastolic >100 mm Hg or higher | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Gold class III and IV | ||

| Uncontrolled asthma at least two exacerbations in the last 6 months | ||

| Amputated lower extremities | ||

| Active cancer treatment during the last 6 months | ||

| Ankylosing spondylitis | ||

| History of schizophrenia | ||

| Parkinson’s disease | ||

| Cerebrovascular accident last 6 months | ||

| Epilepsy treated with medication | ||

| Severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) interfering with mobility | ||

| Fracture of lumbar spinal vertebra/thoracic spinal vertebra or lower extremity in the last 6 months | ||

| Three fractures in the last 2 years due to severe osteoporosis | ||

| Acute depression (TRD) | ||

| After screening process | Spouse/living together with an already included participant in this trial |

AMS, clinical site Amsterdam; STU, clinical site Stuttgart; TRD, clinical site Trondheim.

Sample size and recruitment

No sample size calculation was performed for this study as it is a feasibility study not designed to conclude on effectiveness. However, based on a Norwegian population-based study,25 the sample size (n=180) is estimated to be large enough to estimate critical parameters,26 which equals twice the minimum required number of participants suggested (2× n=90) as a general rule to estimate a parameter.27 28

Participants are drawn from the general population with the purpose of identifying those estimated to be at risk of accelerated functional decline. The number required to invite in order to reach 180 participants is not predefined, due to insufficient knowledge about ability/function in this age group and because the risk screening tools (see below) are newly developed.16 A contact list was provided for home-dwelling individuals between 61 and 70 years of age living in Trondheim, Amsterdam and Stuttgart, stratified by age and with even distribution of men and women in each age stratum. The initial draw from each local registry was set at 2000 persons, with the intention of performing a second draw if necessary.

Screening

We recruited persons who actively replied to their respective study site by telephone or email following the mailing and invited them to undergo a multistep screening. Screening started with a structured telephone interview to determine interest and eligibility, which among other criteria included being retired and currently not undertaking more than 150 min of moderate/vigorous PA per week (table 2). Eligible participants are then invited to an on-site risk screening and medical assessment (table 2). All participants sign an informed consent form prior to commencing the on-site assessments.

An online web-based tool developed through the PreventIT project (the PreventIT risk screening tool) is used to identify participants’ risk for functional decline.16 This is a newly developed tool, where the risk for functional decline over the next 9 years is estimated and participants are classified as being at ‘low risk’, ‘medium risk’ or ‘high risk’. At time of commencing recruitment, the tool had not yet been validated. Initially, only participants identified as being at ‘medium risk’ were to be included in the study, as prior analyses in other cohort data indicated that this would be a third of potential participants.16 The telephone screening, which preceded on-site screening and assessment, was designed to exclude the majority of ‘low risk’ participants. Subsequently applying the risk screening tool on the selected sample showed that only about 10% of individuals invited for face-to-face assessment are classified as ‘medium risk’ and hence eligible for inclusion. Therefore, the selection of participants based on the risk screening tool was discontinued and the risk screening tool is now applied to estimate and describe the participants’ specific risk for functional decline within the recruited cohort. Participants who complete the face-to-face risk screening and are not excluded due to cognitive impairment (Montreal Cognitive Assessment >24)29 are invited to a medical screening to ensure participation in an exercise intervention is not contraindicated. When all inclusion criteria are met, participants are invited to perform a full baseline assessment (T1).

Data collection and outcome measures

All eligible participants undergo a phone screening, risk screening, medical screening and three measurements: one at entry into the study (baseline assessment, T1), one after the 6-month intervention period (T2) and one after completing the 6 months passive follow-up period (12 months assessment, T3). Table 3 highlights the measures collected, table 4 provides a summary of the schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments, and table 5 provides an overview of intervention time frame.

Table 3.

List of assessments and outcome measures collected during telephone screening, risk screening, medical screening, baseline assessment, after 6 months active intervention and further 6 months passive follow-up

| TS | RS | MS | T1 | T2 | T3 | O | |

| Sociodemographic | |||||||

| Age, gender, employment status, living arrangements (community-dwelling or residential aged care facility), number of cohabitants, years of education | ✓ | – | |||||

| Economic satisfaction (good, sufficient, bad/poor) | ✓ | – | |||||

| Prior experience with using smartphone technology (yes/no) | ✓ | – | |||||

| General health and function | |||||||

| Ability to walk 500 m without walking aid | ✓ | – | |||||

| Ability to read newspaper in print and on a smartphone | ✓ | – | |||||

| Participation in an organised exercise group >1 per week (yes/no) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| Currently undertaking 150 min or more in moderate-intensity PA per week (yes/no) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| Amount of moderate-intensity PA undertaken per week (hardly active; mostly seated activities; light-intensity PA (2–4 hours/week); moderate-intensity PA (1–2 hours/week) or light-intensity PA (>4 hours/week); moderate-intensity >3 hours/week; high-intensity PA several times per week) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| Late-Life Function and Disability Instrument (LLFDI) to assess meaningful change in function (person’s ability to do discrete actions/activities) and disability (person’s performance of socially defined tasks)30 31 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | P | |||

| Medical history and medication use | |||||||

| ‘Have you seen a doctor for being diagnosed for having problems with your joints?’* | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | |||

| ‘Have you seen a doctor for being diagnosed for having problems with your heart?’† | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | |||

| Medications used (total number, type, frequency, dosage) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | ||

| Fall history (count over last 12 months) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| Pain during rest and walking (numeric scale, score 0–10)41 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) in lying and standing (after 1 and 3 min); pulse, vision, hearing | ✓ | – | |||||

| Comorbidities (number, type, date of diagnosis and treatment) | ✓ | – | |||||

| Height (cm), weight (kg) | ✓ | – | |||||

| Regular alcohol consumption per week (units) | ✓ | – | |||||

| Neuropsychological | |||||||

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) score to assess symptoms of depression and mood (score range 0–60)‡42 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| 7-Item Short Version Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I) (score)43 plus three additional FES-I items to assess ‘fear of falling’‡44 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) tool (converted MoCA score) to assess cognitive function (score _/30)‡29 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| Physical | |||||||

| Gait speed over 4 m (usual pace)45 and 7 m (usual pace and as fast as possible)46 (best of two trials per measure, m/s) | ✓§ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | ||

| Hand grip strength using a dynamometer (kg, max score of 3 reps per hand, using the protocol of the InChianti study) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | |||

| Five times sit-to-stand to assess functional strength45 | ✓ | ✓ | S | ||||

| Physical—balance | |||||||

| Able to perform ‘Tandem stance’ for 10 s with eyes open (yes/no) | ✓ | S | |||||

| Community Balance and Mobility Scale (CB&MS) used to measure higher level balance and mobility47 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| Static balance measured using the 8-Level Balance scale18 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| Physical—instrumented (participants have a smartphone attached to their lower back, instructions are provided by the assessor. Activity is recorded for the duration of the assessment) | |||||||

| 30 s chair stand is completed to quantify strength35 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| Timed Up and Go33 to measure sit-to-stand duration and movement jerk, mean step time, variability of step time, interstride trunk sway in anterior-posterior and mediolateral directions34 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| Tandem stance, 30 s, eyes closed, to assess sway in anterior-posterior and mediolateral directions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| Five times sit-to-stand to quantify strength and measure sit-to-stand duration | ✓ | S | |||||

| Physical—self-administered (instructions are provided in written form (paper and smartphone) and acoustic cues are provided through the smartphone) | |||||||

| Timed Up and Go33 is completed to measure sit-to-stand duration and movement jerk, mean step time, variability of step time, interstride trunk sway in anterior-posterior and mediolateral directions34 | ✓ | ✓ | S | ||||

| Tandem stance, 15 s, eyes closed, to assess sway in anterior-posterior and mediolateral directions | ✓ | S | |||||

| Tandem stance, 15 s, eyes open, to assess sway in anterior-posterior and mediolateral directions | ✓ | S | |||||

| Five times sit-to-stand to quantify strength and measure sit-to-stand duration | ✓ | ✓ | S | ||||

| Physical—sensor-derived data | |||||||

| Behavioural complexity of PA and sleep measured through activity monitoring (data collection for 7 continuous days) (type, duration, intensity) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | P | |||

| Physical activity39 (a set of sensor-based features extracted from signals, including the percentages of sedentary, active and walking times, duration and intensity (metabolic equivalent) of the activities, and gait and turning characteristics) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| Health economics/quality of life | |||||||

| EuroQol-5D, EQ-5D-5L to measure quality of life and as a utility-based quality of life instrument will be used for estimating QALYs (descriptive profile and a single index value for health-related quality of life)48 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| 12-Item Short Form (SF-12) survey to measure function and well-being/quality of life49 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| A resource-use questionnaire is used to ascertain health resource utilisation (eg, GP visits, medication use and healthcare cost from a societal perspective) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| Adherence (monthly follow-up during active and passive intervention period) | |||||||

| Number of visits/calls successfully completed during the intervention period | S | ||||||

| Withdrawals from intervention (n) | S | ||||||

| PreventIT mHealth system use after 6 months (eLiFE only) | S | ||||||

| Uptake and adherence to recommendations/LiFE (all three intervention arms, monthly question) was assessed via email (by use of a secure web-based form) or post including one reminder. ‘Over the last seven days, did you perform the recommended level of physical activity?’ The response options are as follows: (1) yes, I did more than I planned; (2) yes, I did them all; (3) yes, but not as much as I intended; (4) no, I did not feel well; (5) no, I forgot; (6) no, I did not have time; (7) no, I do not like these activities. The control group’s response is identical to the options from the active arm, except the generic term ‘physical activity’ is used instead of ‘activities’. | S | ||||||

| Adherence to the recommendations/LiFE (all three intervention arms, at post-test and follow-up) and validation of the monthly adherence questions will be evaluated by use of the Exercise Adherence Ratio Scale (EARS)50 | ✓ | ✓ | S | ||||

| Experience, motivation and behavioural change | |||||||

| Self-Reported Behavioural Automaticity Index to assess habit formation (score, 7-point Likert scale)51 | ✓ | ✓ | S | ||||

| Level of ease or difficulty in engaging with the intervention and integrating balance, strength and PA into everyday life (score, 7-point Likert scale) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Motivational aspects of the intervention (score, 7-point Likert scale) | ✓ | ✓ | S | ||||

| Willingness to participate | |||||||

| Recruitment numbers, dropouts (n), CONSORT (participant numbers through trial progression) | |||||||

| Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) to measure participants’ motivation52 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | S | |||

| Usability of technology (eLiFE only) | |||||||

| The System Usability Scale53 at post-test and 12 months follow-up | ✓ | ✓ | S | ||||

| The Telehealthcare Satisfaction Questionnaire–Wearable Technology (TSQ-WT)54 at post-test and 12 months follow-up | ✓ | ✓ | S | ||||

| Issues logs from eLiFE participants will be summarised and described | |||||||

| PreventIT mHealth system feasibility, adherence and progression | ✓ | ✓ | S | ||||

| Usability technology (questionnaire) | ✓ | ✓ | S | ||||

Data from PreventIT mHealth system

|

✓ | ✓ | S | ||||

| Acceptability of the intervention | ✓ | S | |||||

| Focus groups (10 participants per intervention arm, at each site): qualitative analysis of narratives of experience of recruitment process, randomisation process, screening and assessments, home visits, instructors, tools used (paper-based or technology), support in intervention period, activities undertaken, ideas for improvement. Qualitative data will also be used to evaluate usability of technology. | ✓ | S | |||||

| Focus groups (with all assessors and instructors): qualitative analysis of narratives of recruitment process, training, successes and challenges in delivering intervention, ideas for improvement | ✓ | S | |||||

| Issue logs from the instructors will be evaluated related to acceptability from the instructors’ perspectives. | S | ||||||

| Acceptability questionnaire 55 with rating of helpfulness of aLiFE/eLiFE activities for improving balance, strength, PA; perceived safety during aLiFE/eLiFE practice; perceived level of difficulty, activity preference, adaptability of activities to fit individual lifestyles and daily activities | ✓ | ✓ | S | ||||

| Adverse events—intervention related and unrelated | S | ||||||

*Question is answered yes/no, and if ‘yes’, if any arthrosis, rheumatologic diseases, or other arthropathies or joint disorders are registered.

†Question is answered yes/no, and if ‘yes’, if any heart failure, myocardial infarction, cardiac dysrhythmias or arrest, valvular disease, or other ischaemic heart disease is registered, and if ‘no’, if any cerebrovascular disease or stroke, hypertension/high blood pressure, or peripheral artery disease is registered.

‡Assessment is part of the risk screening and eligibility criteria, as well as being an outcome measure.

§Only 7 m walk at fast pace was assessed during the RS.

–, not an outcome measure; 6mth, assessment 6 months after randomisation; 12mth, assessment 12 months after randomisation; aLiFE, adapted LiFE; BA, baseline assessment; CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; eLiFE, enhanced LiFE; EQ-5D-5L, 5-level version of EuroQol-5 Dimension; GP, general practitioner; GPS, Global Positioning System; LiFE, Lifestyle-integrated Exercise programme; MS, medical screening; O, outcome measure; P, primary; PA, physical activity; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; RS, risk screening; S, secondary; SMS, short message service; STU, clinical site Stuttgart, Germany; TRD, clinical site Trondheim, Norway; TS, telephone screening.

Table 4.

Schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments

| Time point | Enrolment | Study period | ||||||||

| Preallocation | Allocation | Postallocation | ||||||||

| t2 | t1 | T1 | 0 | PA1 | HV1* | T2 | PA2 | T3 | PA3 | |

| Enrolment | ||||||||||

| Telephone screening |  |

|||||||||

| Risk screening |  |

|||||||||

| Medical screening |  |

|||||||||

| Randomisation |  |

|||||||||

| Assessment† | ||||||||||

| Baseline |  |

|||||||||

| PA monitoring |  |

|

|

|||||||

| Reassessment |  |

|||||||||

| Follow-up |  |

|||||||||

| Intervention (active intervention) | ||||||||||

| eLiFE |  |

|||||||||

| aLiFE |  |

|||||||||

| Control group |  |

|||||||||

| Intervention (passive intervention) | ||||||||||

| eLiFE |  |

|||||||||

| aLiFE |  |

|||||||||

| Control group |  |

|||||||||

PA monitoring/PA1, PA2, PA3 participants’ physical activity was monitored for 7 consecutive days. No contact to the research team was permitted during this time.

*Home visit (HV) 1 was completed 8–15 days after the baseline assessment.

†Outcome measures collected during the assessments are listed in table 3.

aLiFE, adapted LiFE; eLiFE, enhanced LiFE; PA, physical activity.

Table 5.

Overview of intervention time frame

| Time point | eLiFE | aLiFE |

| Week 0 | Extra home visit if no prior smartphone experience | |

| Week 1 | Home visit 1 | Home visit 1 |

| Week 2 | Home visit 2 | Home visit 2 |

| Week 4 | Phone call 1 | Home visit 3 |

| Week 5 | Home visit 3 | Phone call 1 |

| Week 6 | Home visit 4 | |

| Week 9 | Home visit 4 | Home visit 5 |

| Week 11 | Phone call 2 | |

| Week 13 | Phone call 2 | Home visit 6 |

| Week 17 | Phone call 3 | Phone call 3 |

aLiFE, adapted LiFE; eLiFE, enhanced LiFE.

Blinding

All preintervention measures are assessed by trained research staff and the medical screening by medically qualified members of the research teams at the respective sites prior to randomisation. Postintervention measures are collected by personnel blinded to group allocation. Due to the nature of the intervention, it is not possible to blind participants or the instructors delivering the intervention. Outcome measures that identify group allocation (eg, technology acceptability questionnaires) are collected by unblinded research staff.

Outcome measures

All outcome measures are listed in table 3 and include sociodemographic data, outcomes regarding general health and function, medical history, medication use, neuropsychological assessments, measures of physical ability and quality of life measures. Further data are collected for economic evaluation purposes. During the 12-month follow-up period monthly adherence rates are monitored and detailed information about adherence to the interventions is collected during the 6-month (T2) and 12-month (T3) assessments. Experience with the programme, motivation and behaviour change outcome measures, as well as outcome measures regarding willingness to participate, usability of technology and acceptability of the intervention are collected after the active (first 6 months) and passive follow-up period (further 6 months).

Among all outcome measures, two are the primary clinical outcomes that are related to change in function (objective 4) and measured using the LLFDI30 31 and a complexity metric,20 further developed and adapted within the project to assess behavioural complexity in the domains of PA, sleep and social participation.

The LLFDI was developed as a comprehensive questionnaire assessing function and disability for use in community-dwelling older adults.30 31 The LLFDI contains items that represent functional limitations (inability to perform discreet physical tasks encountered in daily routines) and disability (inability to take part in major life tasks and social roles). The LLFDI assesses function in 32 PAs (in three dimensions: upper extremity, basic lower extremity and advanced lower extremity) and disability in 16 major life tasks.

PA and sleep data are collected via PA monitoring. After each measurement point (T1, T2, T3), participants’ PA is monitored for 7 consecutive days using activity monitors at the lower back (fixed using adhesive tape) and the wrist (fixed in an elastic wristband) (AX3 sensors from Axivity; http://axivity.com/product/ax3). Assessment on social interaction is based on detection of outdoor walking derived from the timing and the number of steps of walking episodes. Frequency and number of short message service and phone calls and Global Positioning System statistics are also used as possible social interaction measures. These statistics are anonymous, without identifying the caller/sender. Data on physical behaviour are represented as time series embedding fundamental activity characteristics (ie, type, duration and intensity). The concept of complexity in physical behaviour postulates that high functional status is characterised by freedom of movement in terms of flexibility, ability to successfully achieve daily tasks, physical performance, diversity of activities and participation in social life. On the other hand, advanced ageing and age-related adverse events may be characterised by progressive movement impairment, difficulties with daily tasks and limitation of activities and social life, that is, less complex physical behaviour.32

As part of the on-site assessments, self-administered tests of mobility, balance and functional strength are used, where participants use a smartphone app to perform the ‘Timed Up and Go’,33 ‘Tandem stance, eyes open’ and ‘Five times sit-to-stand’ tests by following instructions in the app, with no additional guidance from the assessor. This test battery is developed as part of the PreventIT project, and the acceptance of self-administered tests will be evaluated. The smartphone is worn in an elastic band around the participant’s waist during the self-administered tests, from which parameters such as sit-to-stand duration, jerk during sit-to-stand, mean step time, variability of step time and interstride trunk sway in anterior-posterior and mediolateral directions can be obtained.34 Participants also perform assessor-guided versions of the Timed Up and Go, Tandem stance (eyes open and closed), Five times sit-to-stand and the 30 s chair stand test originally from the Senior Fitness Test,35 during which the participant ‘wears’ the smartphone to record movement parameters as during the self-administered tests.

Randomisation

Randomisation is undertaken following 1 week of activity monitoring at baseline, using a web-based randomisation procedure developed, used and run by the Unit for Applied Clinical Research at the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences at NTNU. Randomisation is stratified to centre and performed by block randomisation, where block sizes can vary. One person at each site, unblinded to group allocation, has access to the web-based randomisation platform and forwards the result to the instructors who provide the intervention. Recruitment continues until 60 participants have completed their first home visit per study site.

Interventions

Following the feedback from participants in a pilot study, the aLiFE activity framework is applied in both intervention arms. Details of the intervention components are shown in table 6 (Template for Intervention Description and Replication Guidelines). In short, the programme consists of strategies (A) to improve balance by use of four principles (‘decreasing base of support’, ‘shifting your weight to the limits of stability’, ‘stepping over objects’ and ‘stepping, hopping and jumping in different ways’); (B) to increase muscle strength by use of seven principles (‘bend your knees’, ‘sit to stand’, ‘on your toes’, ‘on your heels’, ‘up the stairs’, ‘move sideways’ and ‘tighten muscles’); and (C) to reduce sedentariness and increase PA by teaching the participants two principles (‘sit less’ and ‘walk more’). In addition, the programme comprises a behavioural change model for developing intentions to become more physically active and turning these intentions into actions by embedding activities into daily life to make them habitual. As the participants learn the programme, they can find opportunities, choose other activities and upgrade their existing activities (table 6).

Table 6.

Intervention description using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist

| 1. Brief name | Study name | PreventIT (Early risk detection and prevention in ageing people by self-administered ICT-supported assessment and a behavioural change intervention, delivered by use of smartphones and smartwatches) | ||

| Intervention groups | The aLiFE programme (experimental group 1) |

The eLiFE programme (experimental group 2) |

WHO guidelines (control group) |

|

| 2. Why | A rapidly ageing population will place increasing stress on our healthcare systems. The focus needs to shift from treatment towards health promotion for active and healthy ageing and prevention of age-related diseases. The PreventIT project has adapted a Lifestyle-integrated Exercise (LiFE) programme (to suit healthy young older adults at risk for future accelerated functional decline into two interventions: one delivered by instructors and use of paper manuals (aLiFE), and one delivered via mobile phone (smartphone) with a virtual instructor (eLiFE). The aim is to develop and test a personalised behaviour change intervention on physical activity aimed at young older adults that has the potential to prevent accelerated functional decline at older age. | |||

| 3. What materials | All participants received a detailed risk and baseline assessment at their respective study sites, assessing medical history, physical and cognitive functions and quality of life. All participants had their PA levels recorded for 7 consecutive days using activity monitors. In all three groups, participants completed motivational questionnaires prior to beginning the intervention. | |||

|

Paper manual The aLiFE manual included descriptions and instructions of the activities selectable within the programme (strength and balance exercises), an activity planner (weekly use) and activity counter (daily use), safety instructions and further information about increasing physical activity and reducing sedentariness. |

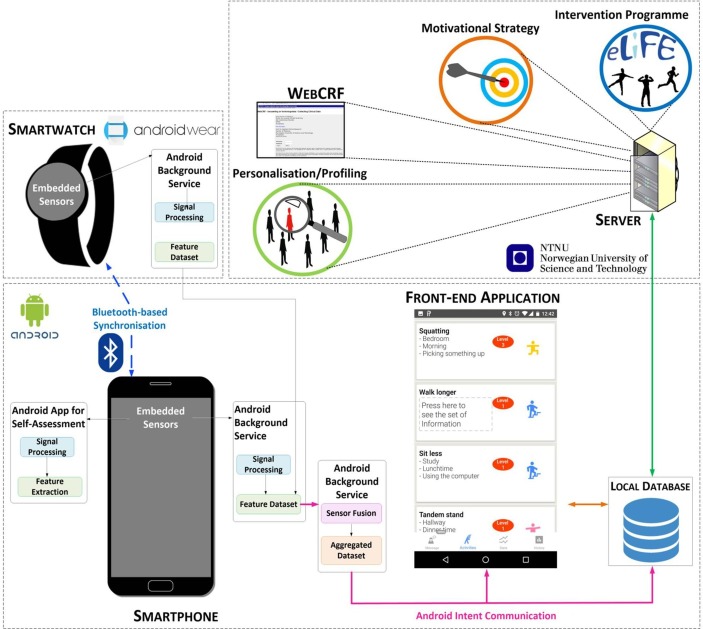

PreventIT mHealth system on smartphone and smartwatch eLiFE was delivered via the PreventIT mHealth system. Participants received instructions by use of video clips, pictures and text/verbal instructions on the PreventIT smartphone for the activities. The architecture of the eLiFE application system is shown in figure 1. Activity planning, reporting and feedback is provided entirely through the smartphone application. Participants receive one troubleshooting document to aid with technological problems they may encounter. Instructors are available to help participants use the smartphone during home visits. |

One-page WHO guidelines regarding recommended PA levels per week for the target group | ||

| 4. What procedure | All participants receive a risk screening and medical assessment to ensure study eligibility and rule out contraindications to an exercise intervention. A detailed baseline assessment at a clinical site and a 7-day PA monitoring is completed. Participants are informed of their group allocation after their 7 days of PA monitoring is completed. | |||

|

Intervention groups Receive direct support through a trained staff member to implement the aLiFE/eLiFE programme into their daily life and understand the concept of the programme. Assistance is provided on how to select, upgrade and identify additional daily situations to integrate activities. Participants receive home visits as well as support phone calls during the 6-month active intervention period as part of the ongoing active intervention. |

Control group During a single home visit the written WHO guidelines are provided to participants with guidance on the dose–response relationship between the frequency, duration, intensity, type and total amount of physical activity recommended per week. |

|||

| 5. Who provided | Assessment | All assessments completed at the clinical sites are completed by blinded research staff with tertiary qualification as physiotherapists or exercise scientists. Assessments are completed at baseline (T1), 6 months after randomisation (T2) and 12 months after randomisation (T3). | ||

| Intervention | Following randomisation, participants receive the relevant intervention delivered in their home, provided by physiotherapists or exercise scientists. All staff had undergone a 3-day workshop to ensure standardised intervention delivery across all three clinical sites. | |||

| 6. How | Invitation to participate | Persons born between 1947 and 1956 (61–70 years of age at the time of inclusion) were invited via mail-out to participate. Three respective local registries randomly selected persons within the target group. Participants were required to contact their respective site actively if they were interested. | ||

| Telephone screening | A telephone screening determined eligibility to attend the risk screening of potential participants. | |||

| Risk screening and medical screening | The risk screening is completed by trained researchers and a medical screening is completed by medical doctors at each site. The multistep process ensures participants meet inclusion/exclusion criteria, and that an exercise programme is deemed safe from a medical perspective. | |||

| T1, T2, T3 assessment | The assessments are completed by blinded research staff at the three clinical sites. | |||

| The interventions (aLiFE and eLiFE) are delivered in the participants’ home, the types of activities and difficulty levels are dependent on the individual’s ability and preference. Home visits and follow-up phone calls are completed according to a predefined schedule. Participants are permitted to attend further exercises groups, undertake other activities or seek further healthcare during the duration of the trial which are beyond the scope of the RCT. Details are recorded during assessments (T2, T3) but no additional assistance is provided by the research staff. | The control group receives a single home visit and is provided with written information about PA recommendations only. Participants are permitted to attend exercise groups, undertake other activities or seek healthcare during the duration of the trial which are beyond the scope of the control group intervention. Details are recorded during assessments (T2, T3) but no additional assistance is provided by the research staff. |

|||

| 7. Where | The RCT is conducted as part of the PreventIT project, a European Horizon 2020 ICT and personal health project (project number 689238). The three participating clinical centres are Trondheim, Norway; Amsterdam, The Netherlands; and Stuttgart, Germany. | |||

| 8. When and how much | The aLiFE programme (experimental group 1) |

The eLiFE programme (experimental group 2) |

WHO guidelines (control group) |

|

| Home visits, phone calls | 6 home visits 3 phone calls |

4 home visits 3 phone calls |

1 home visit | |

| Active intervention period | 6 months | 6 months | NA | |

| Passive follow-up period | 6 months | 6 months | 12 months | |

| Instructor main role | Teach the programme | Teach how to use the PreventIT mHealth system | NA | |

| Activities | Participants choose activities from the strength, balance and/or PA domain to integrate into their daily activities. The number of activities is individual and an activity planner and counter is used for documentation purposes. | The PreventIT mHealth system suggests a list of activities to participants ranked according to the expected level of benefit. Participants select their preferred activities from this list. The number of activities chosen is determined by the individual. | NA | |

| Training goals | Decided by the participants with help of a prespecified list of possible goals | Participants select goals from a prespecified list within the application | NA | |

| Phenotyping tool | Not used in aLiFE | Results from assessments (T1) are included in the PreventIT mHealth system for each participant individually prior to the first home visit to decide what to prioritise among the activities (balance, strength or physical activity). | NA | |

| Motivation | Provided by the instructor-based individual progress (eg, reviewing the activity planner during home visits) | Personalised motivational messages are displayed on the phone based on chosen activities and the reported adherence | NA | |

| Social interaction/chat | NA | Participants can use the platform ‘Slack’ for group chat to communicate anonymously with other eLiFE participants at their clinical site. | NA | |

| 9. Tailoring | aLiFE assessment tool (LAT) | The LAT is performed at the first home visit so the instructor can set the initial difficulty level on the balance and strength activities. | The LAT is performed at the first home visit, instructors manually add the results to the PreventIT mHealth system and the system sets the initial difficulty level on the balance and strength activities. | NA |

| Progression | The instructor teaches the participants when to upgrade the number of activities and situations during the subsequent home visits | Participants can independently progress their activities based on the rule that the user has performed the activity each day for the last 7 days for at least 50% of the goal on average and at least 50% of the goal on each of the last 3 days. The progression is not compulsory when a higher level becomes accessible. |

||

| Feedback | Feedback is provided by the instructor based on individual progress (reviewing the activity planner and counter) during home visits. | Participants receive feedback on their PreventIT mHealth system: 1. Based on physical behaviour monitored by the smartphone and the smartwatch (time of PA and amount of sedentariness). 2. Depending on the amount (type and dose) of strength and balance activities completed (in-app adherence reporting) in relation to the intended type/dose. |

NA | |

| 10. Modification | Super-user | Participants are recommended to select activities that are challenging and relevant to the individual as identified using the LAT. As some participants reached level 4 (highest level) on certain activities (mainly strength exercises), further ‘upgrades’ to the activities were offered. This ‘super-user’ concept aims to further increase the task challenge (beyond level 4) in order to ensure a training intensity which induces motor adaptations and clinically relevant improvements in functional performances. It includes elements of peak strain, slow motion (extended muscle loading), increased number of repetitions, differential training (learning through change/differences in movement variables, eg, joint angle/position), combining strength and balance activities, decreasing base of support and more complex sensorimotor tasks. Participants are able to access the ‘super-user’ function for a specific activity after having performed the particular activity at 100% for 14 consecutive days. |

NA | |

| 11. How well planned | Participant daily adherence | Daily adherence can be reported using the activity counters, with responses being dichotomous (completed, not completed). | Daily adherence is reported on the PreventIT mHealth system that specifically asks about the planned/intended activities as previously defined by the participant. | NA |

| Participant monthly adherence | Monthly adherence data are obtained via a weblink or via a postal question. Participants are asked if they completed all their activities/PA as intended in the last 7 days. The responses are: (1) yes, more than intended; (2) yes, as much as intended; (3) yes, but not as much as intended; (4) no, did not feel well; (5) no, forgot; (6) no, no time; (7) no, dislike of planned activity. | |||

| Instructor fidelity | Training is delivered independently in each of the three clinical sites. All instructors adhere to a single training protocol to ensure standardised delivery of the programme across sites. Training delivery was taught during a 3-day workshop with subsequent exam. | |||

aLiFE, adapted LiFE; eLiFE, enhanced LiFE; ICT, Information and Communication Technology; NA, not applicable (this intervention component is not available in this intervention arm/control group); PA, physical activity; RCT, randomised controlled trial; T1, baseline assessment; T2, assessment 6 months after randomisation±2 weeks; T3, assessment 12 months after randomisation±4 weeks.

The activities are individually tailored to each participant’s functional status at the first home visit by use of an initial balance and strength assessment (the LiFE assessment tool),17 defining the starting level for the balance and strength activities.

Both eLiFE and aLiFE participants receive home visits during which instructors teach and deliver the LiFE programme. Three follow-up/booster phone calls are also provided during the 6-month active intervention period (table 6). eLiFE participants receive instructions by use of video clips, pictures and text/verbal instructions in the PreventIT application on a smartphone for each activity and aLiFE participants use a paper-based manual with descriptions and instructions for the same activities. eLiFE participants receive android phones that they use during the intervention and follow-up period. Participants without any smartphone experience receive one extra home visit with information on how to use a smartphone prior to starting the home visits in week 1. eLiFE participants also receive technological support to navigate through the application. The architecture of the eLiFE application system is shown in figure 1. The active intervention is scheduled for 6 months in order to be able to change behaviour.14 36 Participants are encouraged to continue independently to use smartphones and smartwatches (eLiFE) or their paper materials (aLiFE) during the passive follow-up period (between months 7 and 12).

Figure 1.

The architecture of the enhanced LiFE (eLiFE) system. Physical behaviour is continuously monitored by a smartphone and a smartwatch, connected through a Bluetooth. The same units are also used for delivering the intervention. Data are calculated and stored locally on the smartphone and then sent to a cloud-based server for further processing and storing. The collected information is sent back to the smartphones in the form of motivational messages and feedback on behaviour.

eLiFE/aLiFE instructors

The instructors follow an eLiFE and aLiFE instructor manual with topics to teach during each home visit/phone call. To ensure all clinical sites deliver the programme in a standardised manner, instructors attended a 3-day workshop covering the eLiFE and aLiFE concept. aLiFE components including aims, activity principles, behavioural change concept, instructing and supporting the participants in action planning using the activity planner and activity counter, upgrading activities during subsequent home visits and phone calls, and safety principles were taught. The eLiFE concept included the same content as aLiFE and additionally, knowledge about the PreventIT mHealth system and how to instruct the participants to use the technology was included in the workshop. All instructors were tested and awarded certification prior to the start of the study, to ensure that they had the competences needed to deliver both the eLiFE and the aLiFE interventions.

Control group

The control group receives one home visit to provide them with a two-page written summary of the WHO recommendations of PA.37 These guidelines are relevant to all healthy older adults unless specific medical conditions indicate the contrary, and highlight the benefits of being physically active as well as stimulate the recommended amount of PA to be undertaken per week.

Focus groups

Semistructured focus group interviews are conducted with a maximum of 10 participants from each intervention arms and control group at each site, after the post-test (T2) assessment. The topics to be discussed include: (A) the recruitment process; (B) the randomisation process; (C) screening and assessments; (D) home visits; (E) the instructors; (F) the tools used (paper based and technology enabled); (G) support in the intervention period; (H) the activities undertaken; (I) experience of the follow-up period; and (J) ideas for improvement. In addition, the eLiFE participants are asked to keep an ‘Issues log’ to record issues and difficulties with the technology and on the trial procedure.

At the end of the trial, interviews with the assessors and the instructors will be performed. Interviews will be performed face-to-face using a semistructured interview guide. Topics to be discussed include: (A) the recruitment process; (B) the training received; (C) successes and challenges in delivering the intervention; and (D) ideas for improvement. Focus groups and interviews are expected to last between 90 and 120 min. All focus groups and interviews are recorded using a digital voice recorder, transcribed and translated into English prior to data analysis.

Participant retention, adherence and dropout

Participants’ progression through the study phases is documented and presented in a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials38 flow diagram. Reasons for dropout from the entire trial, or the intervention programme only, are recorded. In consenting to the trial, participants are consenting to the trial treatment, follow-up and data collection. If withdrawal from the randomly allocated treatment occurs, participants are still followed up if they consent. Participants are allowed to withdraw without giving a reason at any time and a withdrawal corticotropin-releasing factor is completed to document the date and reason (if known) for withdrawal. Data collected up to the time of withdrawal will be included in analyses unless the patient specifically asks for it to be withdrawn.

In all three study arms adherence to the intervention is measured monthly by use of a single question answerable via email or postcard (see details in table 6). The intervention arms also report their exercise adherence on a daily basis through in-app reporting (eLiFE) or paper documentation (aLiFE: activity counter). Adherence measures are part of the study procedure as well as an outcome measure in this trial.

Safety considerations and adverse events

Basedon existing literature, the risk of adverse events during the eLiFE and aLiFE training is estimated to be low.17 18 The safety aspect is emphasised in the eLiFE and aLiFE programmes, including the participants’ manuals and smartphone app. Exercise training can have side effects and thus some adverse reactions such as muscle pain or adverse events like falls due to being more physically active in everyday life are expected. Several strategies have been incorporated in this trial to minimise the risk for study participants.

The number and description of adverse events that occur during the intervention and follow-up period that could be attributable to participation in the eLiFE or aLiFE programme are recorded. Participants are encouraged to report any adverse events and the medical responsible person at each site evaluates the need for further medical care. In case of any serious adverse event, participants are encouraged to seek appropriate medical advice/help. All adverse events are reported to the PreventIT Independent Data Monitoring Committee and will be reported in all publications arising from this project.

Planned data analyses

A complete data analysis plan was finalised on 3 October 2017 before the T2 assessments (at 6 months) started (accessible via first author).

The first analyses will be performed blinded to group allocation. It will be evaluated whether there is a pattern of missing data, and sensitivity analyses will be performed when missing data, collected via an assessor or using the smartphone, are judged not missing at random. Data at baseline will be analysed using descriptive statistics. The primary clinical outcome measures will evaluate the change in function from baseline (T1) to follow-up (T3), for the eLiFE and the aLiFE interventions compared with the control group. Linear mixed models will be used which will include factors for time point and study allocation, as well as their interaction, as independent variables. Within-subject baseline risk will be accounted for by including a subject-specific random intercept. Due to a limited number of centres (3), the centre effect will be treated as fixed rather than random, and included among the independent variables. Estimates of effect sizes for the differences between eLiFE, aLiFE and control groups, and for changes within the eLiFE and aLiFE groups, will be provided as mean differences for the outcome variables. In case of non-normality, other appropriate models will be used. Results will be used to perform calculations of sample sizes to determine the optimal number of participants to be included when planning for a future final RCT to detect a real effect as statistically significant.

The analysis of change will be based on intention to treat, but a per-protocol analysis will also be conducted as a sensitivity analysis as this is likely to provide further insight into the feasibility of the interventions.

In order to determine a potential dose–response association between the adherence and outcome, the association between the two primary clinical outcomes, measured by LLFDI and activity monitoring (complexity metric), and the adherence measures collected (single question every 4 weeks to all participants in all three groups) will be assessed. Further subgroup analysis dependent on group allocation or adherence is described in detail in the analysis plan.

Multimodal analyses will be performed to calculate behavioural complexity using appropriate metrics such as Lempel-Ziv complexity (LZC). LZC determines the number of distinct temporal sequences of multivariate PA states, as well as the rate of their recurrence, with larger values indicating higher complexity of the given activity pattern.20 Data collected from the 7-day activity monitoring will be processed offline making use of software developed in the FARSEEING project (http://farseeingresearch.eu).39 A set of sensor-based PA features will be extracted from the signals, including the percentages of sedentary, active and walking times, duration and intensity (metabolic equivalent) of the activities and gait and turning characteristics. Combinations of these features will be used to define the multivariate states.20

A further focus of the analyses will be on the willingness to participate, adherence to the interventions and acceptance of the interventions, including the technology used to deliver the intervention and give feedback and motivation for behavioural change.

Another focus will be to analyse the data collected by the technology to establish their reliability, to analyse participants’ perception of which activities they have completed compared with what sensors have recorded as well as exploring additional metrics.

The health economics analysis will focus on the feasibility of collecting data on, and estimate, healthcare resource utilisation, costs and QALYs, and model ICER of eLiFE and aLiFE compared with the control group over a 6-month and 12-month period in a standard within-trial evaluation model. EQ-5D-5L health utility scores will be used to calculate QALYs for economic evaluation. Published national unit costs will be used to calculate the total costs of resource utilisation.

This feasibility RCT is a hypothesis-generating study, where additional explorative analyses not described in this protocol paper or data analysis plan might be planned and performed.

Data storing and security

Data are collected by the research staff, and from smartphones and smartwatches used by eLiFE participants. Data are stored in three different locations: in a web-based case report system (WebCRF), developed by NTNU, in the memories of the individual smartphones and in an in-house protected server at NTNU. Data are synched daily from the smartphones onto the servers. Moreover, data on the servers are backed up daily as part of the routine scheduled backup of the NTNU computer centre that hosts the PreventIT servers. Participants’ ID and identifiable information are kept locally and securely by recruiters at each site at all times. Data in the WebCRF and in the NTNU servers are pseudonymised. Only research staff directly involved in the analysis of the RCT will have access to the final trial data set, which will only contain non-identifiable information.

The in-house web server will be in a demilitarised zone and behind a firewall. Both the WebCRF and the data servers will be behind a second firewall. Security and other ethical issues are priority, as sensor systems that monitor and report on health-related behaviours depend on the processing of personal data. All the data on the server are maintained in encrypted databases.

All data on smartphones are kept in encrypted databases. All transmission of data between the server and the smartphones is encrypted. Each phone/user is provided with an individual user login.

After the conclusion of the feasibility RCT, data will remain stored on the NTNU server in pseudonymised format using participant IDs. Coupling to personal IDs will be stored securely for 5 years after the end of the PreventIT project at each of the three sites. After this, data will be fully anonymised.

Participant and public involvement

Prior to commencing this feasibility RCT, pilot studies were conducted for both the eLiFE and the aLiFE intervention modes. These pilot studies provided information about the practical execution of collecting the relevant outcome measures, and to improve the intervention components, with a focus on the feasibility and acceptability of the balance, strength and PA activities. The eLiFE intervention was further tested for usability and acceptability within the target group. Focus groups were conducted during the pilot studies, providing insight into participants’ priorities, experience and preferences. There are no participant advisers in the study, as the aim is to conduct a feasibility RCT and not a final RCT.

Following the participants’ final assessment (T3), all participants will get individual, written results from their participation providing them with an overview of the study status and their personal results regarding physical outcome measures and the 7-day consecutive PA monitoring.

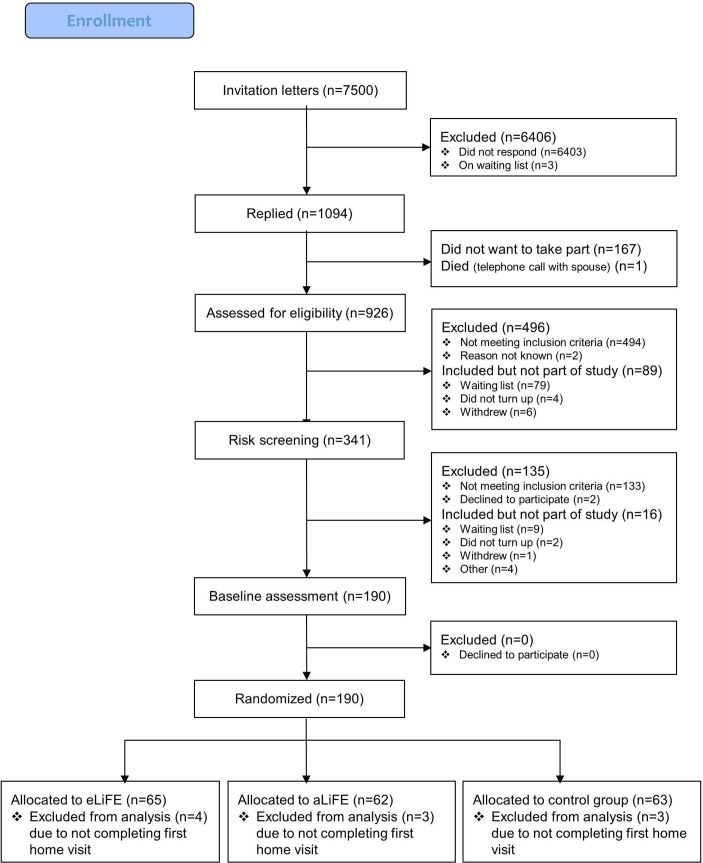

In total, 7500 persons between 61 and 70 years of age were drawn from the local registries in Norway, Germany and the Netherlands. Two thousand letters in Trondheim, 1500 letters in Stuttgart and 4000 letters in Amsterdam were sent. Following the three-step screening process, 180 participants were successfully enrolled into the study, accepted randomisation and completed their first home visit. The flow of participants from recruitment until randomisation is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

PreventIT flow diagram. aLiFE, adapted LiFE; eLiFE, enhanced LiFE.

Discussion

The current study is designed to evaluate the feasibility of conducting an RCT of a lifestyle-integrated intervention delivered in two modes, aLiFE (an instructor-delivered, paper-based intervention) and eLiFE (a newly developed intervention using a mobile health application system) compared with simply being given guidelines on PA requirements. Both interventions entail embedding activities into daily life, strengthened by a behavioural change model aimed at making the activities habitual. This study further develops and adapts the LiFE programme to suit a younger population of seniors, at retirement age (61–70 years). Particularly at time of retirement, LiFE-based interventions may be beneficial to young older adults by specifically completing lower extremity muscle strengthening and balance activities as well as increasing PA to avoid later age-related functional decline. In comparison to traditional exercise programmes, such as group training and gym workouts where one needs to set aside dedicated time to follow the programme, LiFE-based programmes embed small bouts of activities into the individual’s routines that are already part of their daily life. This individual tailoring of exercises, and embedding them into daily routines, seems to be a promising approach to keep young older adults active.40

Capitalising on the benefits of technological advances and embedding the concept into a mobile health application system, aLiFE was transferred to an ICT platform to create eLiFE using smartphones and smartwatches, commonly available technology already in use in this target population. There is a rapid development in mobile health application technology, with numerous health applications currently available. Application systems may motivate persons to be more physically active, provide opportunities to personalise interventions, provide feedback to the person using the technology and help people keep track of their PAs. Despite this potential, there is at present a lack of systems developed based on existing knowledge from research on exercise programmes and behavioural change, and tailored for use in young older (61–70 years) adults. The current trial will provide data on feasibility and usability of both the mobile health application in eLiFE and the instructor-delivered aLiFE. The aim is that the interventions can empower this population to maintain or increase their activity levels, so that they can stay active and healthy longer at advancing age. The study will provide more knowledge about how to integrate demanding activities into daily life and how to deliver an intervention to young older adults in order to increase their daily PA.

Finally, it is challenging to recruit a target population of young older adults without current signs of functional decline. Understanding how to recruit this specific population will aid in providing recommendations for a future RCT.

Conclusions

It is expected that both eLiFE and aLiFE have the potential to provide effective means to increase PA and complexity, improve functional capacity and change behaviour in young older adults. By using technology in eLiFE, it is expected that the behavioural change aspects of the aLiFE intervention are strengthened. It is also expected that an intervention that embeds more activity into daily life has the potential to empower young older adults to stay active at older age and therefore has the potential to reduce the risk of future functional decline.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has approvals to send invitation letters based on data from local/national registries.

We will seek to publish all results from the feasibility trial in open-access, peer-reviewed international journals, and disseminated at scientific and non-scientific conferences and events. Main results will also be shared on the project website and spread to various stakeholders. Authorship eligibility will follow the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authors-and-contributors.html).

Trial status

The trial commenced recruitment in March 2017. In August 2017, a total of 180 participants were included in the trial.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the ongoing support of participants, research staff, coordinators, data managers and other site staff who have been responsible for setting up the trial, recruiting participants and collecting data.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors made substantial contribution to the concept and design of the study. KT drafted the manuscript, with input from BV and JLH. EB, DPF, CT and HHH provided input on behavioural change. SM, AZ, KA and API provided technical input on the eLiFE description. FBY and BG provided input on health economics. CB, MS and LC provided input on the background information about the project. ABM, JvA, NHJ and MP provided input on the medical assessment and screening of participants. SB, RB, BV, JLH and LC commented on the entire manuscript. KT, ASM, BV and JLH critically revised the manuscript with input from all coauthors. All authors approved the final version of the document.

Funding: The feasibility RCT is part of the EU funded project ’PreventIT' (2016– 2018, grant number 689238) responding to the Horizon 2020, Personalised Health and Care call PHC-21: Advancing active and healthy aging with ICT: Early risk detection and intervention. The PreventIT project focuses on a new behaviour change activity approach for young older adults (61–70 years of age) with an overall aim to shift focus from treatment of conditions and diseases to early prevention and to empower people to take care of their own health.

Disclaimer: The EU was not actively responsible or involved in the study design, collection, management, analysis or interpretation of data. The writing of reports and the decision to submit for publication is not authorised by the EU.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study and methods were evaluated and approved by the ethical committees in Norway (REK midt, 2016/1891), Stuttgart (registration number 770/2016BO1), and Amsterdam (METc VUmc registration number 2016.539 (NL59977.029.16)).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Health at a Glance. OECD Indicators. 2013http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Health-at-a-Glance-2013.pdf (Accessed Jan 2016).

- 2.Chatterji S, Byles J, Cutler D, et al. . Health, functioning, and disability in older adults–present status and future implications. Lancet 2015;385:563–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61462-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rechel B, Doyle Y, Grundy E, et al. . How can health systems respond to population ageing?. Policy Briefing 10 WHO Regional Office for Europe 2009. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/64966/E92560.pdf (Accessed Jan 2016).

- 4.Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, et al. . American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009;41:1510–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawe RJ, Leurgans SE, Yang J, et al. . Association Between Quantitative Gait and Balance Measures and Total Daily Physical Activity in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2018;73:636–42. 10.1093/gerona/glx167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WorldHealthOrganization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olesen K, Rod NH, Madsen IE, et al. . Does retirement reduce the risk of mental disorders? A national registry-linkage study of treatment for mental disorders before and after retirement of 245,082 Danish residents. Occup Environ Med 2015;72:366–72. 10.1136/oemed-2014-102228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landi F, Calvani R, Tosato M, et al. . Age-Related Variations of Muscle Mass, Strength, and Physical Performance in Community-Dwellers: Results From the Milan EXPO Survey. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:88.e17–88.e24. 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawley-Hague H, Horne M, Campbell M, et al. . Multiple levels of influence on older adults’ attendance and adherence to community exercise classes. Gerontologist 2014;54:599–610. 10.1093/geront/gnt075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nyman SR, Victor CR. Older people’s recruitment, sustained participation, and adherence to falls prevention interventions in institutional settings: a supplement to the Cochrane systematic review. Age Ageing 2011;40:430–6. 10.1093/ageing/afr016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mikolaizak AS, Lord SR, Tiedemann A, et al. . Adherence to a multifactorial fall prevention program following paramedic care: Predictors and impact on falls and health service use. Results from an RCT a priori subgroup analysis. Australas J Ageing 2018;37:54–61. 10.1111/ajag.12465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.French DP, Olander EK, Chisholm A, et al. . Which behaviour change techniques are most effective at increasing older adults’ self-efficacy and physical activity behaviour? A systematic review. Ann Behav Med 2014;48:225–34. 10.1007/s12160-014-9593-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray JM, Brennan SF, French DP, et al. . Effectiveness of physical activity interventions in achieving behaviour change maintenance in young and middle aged adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med 2017;192:125–33. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stiggelbout M, Hopman-Rock M, Crone M, et al. . Predicting older adults’ maintenance in exercise participation using an integrated social psychological model. Health Educ Res 2006;21:1–14. 10.1093/her/cyh037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devereux-Fitzgerald A, Powell R, Dewhurst A, et al. . The acceptability of physical activity interventions to older adults: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Soc Sci Med 2016;158:14–23. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonkman NH, Del Panta V, Hoekstra T, et al. . Predicting Trajectories of Functional Decline in 60- to 70-Year-Old People. Gerontology 2018;64:212–21. 10.1159/000485135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]