Abstract

Objectives

The goal of this study is to identify, analyse and classify interventions to improve adherence to reporting guidelines in order to obtain a wide picture of how the problem of enhancing the completeness of reporting of biomedical literature has been tackled so far.

Design

Scoping review.

Search strategy

We searched the MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane Library databases and conducted a grey literature search for (1) studies evaluating interventions to improve adherence to reporting guidelines in health research and (2) other types of references describing interventions that have been performed or suggested but never evaluated. The characteristics and effect of the evaluated interventions were analysed. Moreover, we explored the rationale of the interventions identified and determined the existing gaps in research on the evaluation of interventions to improve adherence to reporting guidelines.

Results

109 references containing 31 interventions (11 evaluated) were included. These were grouped into five categories: (1) training on the use of reporting guidelines, (2) improving understanding, (3) encouraging adherence, (4) checking adherence and providing feedback, and (5) involvement of experts. Additionally, we identified lack of evaluated interventions (1) on training on the use of reporting guidelines and improving their understanding, (2) at early stages of research and (3) after the final acceptance of the manuscript.

Conclusions

This scoping review identified a wide range of strategies to improve adherence to reporting guidelines that can be taken by different stakeholders. Additional research is needed to assess the effectiveness of many of these interventions.

Keywords: scoping review, quality of reporting, completeness of reporting, reporting guidelines, knowledge synthesis, adherence

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We considered a wide range of reporting guidelines as well as their extensions.

Merging the evidence found in the published and grey literature allowed us to provide a broad picture of how the problem of enhancing adherence to reporting guidelines has been tackled so far and could be faced in the future.

The screening and data extraction were performed in duplicate.

We could have missed evidence of possible interventions that may not be present in the published or grey literature but are instead used in practice and continue to be used.

Background

Approximately 85% of all biomedical research today is estimated to be wasted, due, in part, to incomplete or inaccurate reporting.1 The past two decades have given rise to a number of changes in an effort to help authors and the broader scientific community properly report research methods and findings, which would allow them to contribute to the broader goal of combating waste in biomedical research. The most prominent of these changes has been the inception of reporting guidelines (RGs) for different study types, data and clinical areas.2

The vast majority of RGs have not yet been assessed as to whether they help improve the reporting of research,3 but some, such as the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) for the reporting of randomised controlled trials (RCTs),4 have been shown to enhance the completeness of reporting.5 6

Dozens of systematic reviews have explored the extent of adherence to some RGs in certain areas of health research.7–10 Samaan et al 11 went one step further and performed a systematic review of systematic reviews assessing adherence to RGs. As they considered a broad range of clinical areas and study designs, their results provided a global picture of adherence to RGs in health research. Although some studies reported acceptable overall levels of completeness of reporting and found that it had improved since the introduction of certain RGs such as CONSORT, the authors of most of the reviews (43 of 50, 86%) concluded that more improvement is needed or that adherence to RGs was inadequate, poor, medium or suboptimal. Therefore, it is warranted to explore and develop strategies to improve the current levels of adherence to RGs.

In recent years, several initiatives aiming to improve adherence to RGs have been proposed, some of which have already been evaluated. For example, the effect of journal endorsement of RGs3 5 6 and the implementation of writing aid tools for authors such as the CONSORT-based web tool (COBWEB)12 have been assessed. While some of these strategies have not been shown to have a benefit,3 others report better but still suboptimal levels of reporting5 6 or even clear benefits.12 13

As mentioned, several reviews have analysed the quality of reporting in different clinical areas and for different study types.7–10 However, no scoping review has been performed that provides a global picture of different strategies aiming to improve adherence to RGs. Given the low levels of completeness of reporting in health research that have been observed,11 along with the imperative need to take further actions for mitigating this problem, we considered that performing such a scoping review was warranted.

In addition to analysing the implementation and effect of interventions that have already been evaluated, we aimed to gather other possible strategies that could be implemented and evaluated in the future.

For clarification, some relevant terms used throughout the scoping are defined in box 1, which is based on Stevens et al.3

Box 1. Relevant definitions in the context of this scoping review.

Adherence

Action(s) taken by authors to ensure that a research report is compliant with the items recommended by the appropriate/relevant reporting guideline. These can take place before or after the first version of the manuscript is published.

Endorsement

Action(s) taken by journals to indicate their support for the use of one or more reporting guideline(s) by authors submitting research reports for consideration.

Implementation

Action(s) taken by journals to ensure that authors adhere to an endorsed reporting guideline and that therefore published papers are completely reported.

Complete reporting

Pertains to the state of reporting of a study report and whether it is compliant with all the items recommended by the appropriate/relevant reporting guideline.

Methods

As presented in the published protocol,14 this scoping review follows the methodology manual published by the Joanna Briggs Institute for scoping reviews.15

Objectives

The scoping review questions are:

What interventions to improve adherence to RGs in health research have been evaluated?

What further interventions to improve adherence to RGs have been performed or suggested but never evaluated?

We aimed to analyse and classify the interventions found for both questions in order to obtain a wide picture of how the problem of adhering better to RGs has been tackled so far and can be tackled in the future.

Eligibility criteria

We included:

Studies evaluating interventions aiming to improve adherence to RGs in health research, irrespective of study design.

Commentaries, editorials, letters, studies and online sources describing possible interventions to improve adherence to RGs that have been performed or suggested but never evaluated.

The RGs considered were those shown on 8 May 2017 on the Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of Health Research (EQUATOR) Network website16 as ‘RGs for main study types’. In addition, we included Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses, since it was the precursor of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). Online supplementary file 1 shows all RGs considered.

bmjopen-2018-026589supp001.pdf (79KB, pdf)

We considered the following languages: English, Spanish, French, German and Catalan.

Exclusion criteria

We have excluded references that include interventions that do not specifically aim to improve the completeness of reporting, even though these interventions may actually influence completeness. For example, we have excluded clinical trial registration even though it may enhance the completeness of reporting, because its main goals are to improve clinical trial transparency while also reducing publication and selective reporting biases.

Search strategy and study selection

On 8 May 2017, we searched PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane Library databases for articles published between 1 January 1996 and 31 March 2017, in accordance with our scheduled search.14 The detailed search terms for PubMed can be found in the protocol.

The retrieved studies were exported into Mendeley and duplicates were automatically removed using it. One reviewer (DB) first screened the titles and abstracts for eligibility. Each of the other two reviewers (JJK and EC) was randomly assigned 50% of the references and screened the titles and abstracts independently of the first reviewer. The reviewers classified the references into one of the following groups:

Evaluated: Includes references describing interventions to improve adherence to RGs that have been empirically assessed.

Non-evaluated: Includes references describing interventions to improve adherence to RGs that have been performed or suggested but never evaluated.

Unclear: Includes references (1) containing vague statements such as ‘authors, editors and journals have to adhere better to RGs to improve the quality of reporting’ or ‘greater efforts have to be made by authors to check that their research is compliant with (the relevant RG)’, or (2) not having the abstract available.

Excluded: Includes references (1) not describing interventions to improve adherence to any of the RGs considered and (2) describing but not evaluating certain interventions that have already been classified as evaluated.

Disagreements were solved by discussion among the reviewers.

Second, one reviewer (DB) examined the full text of all group A and B references to confirm the previous classification, then all group C references to reclassify them either as group A, B or D. Reclassification was verified by the initial reviewer (JJK or EC). Finally, one reviewer (DB) ensured literature saturation by searching the reference lists of included studies, the lists of articles citing them according to PubMed, and the individual studies included in two relevant systematic reviews.3 6

In addition, we performed a grey literature search, which included: the websites of networks and organisations promoting the use of RGs (ie, EQUATOR Network and National Library of Medicine Research Reporting Guidelines and Initiatives); work groups of medical journal editors (ie, International Committee of Medical Journal Editors and World Association of Medical Editors); biomedical journal publishers (ie, BMJ Publishing Group and BioMed Central); funding agencies (ie, National Institute of Health and European Research Council); online platforms of postpublication peer review (ie, PubPeer and ScienceOpen); and the abstract books of the past editions of the International Congress on Peer Review and Biomedical Publication.

Some of the included references were described in studies coauthored by some of the authors this scoping review. These references underwent the same process of screening, data extraction and data synthesis as the others.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed to collect the information necessary for data synthesis. Two reviewers (DB, JJK) independently performed a pilot data extraction on a random sample of five articles and subsequently refined the form.

Extracted data included:

Publication characteristics: title, year of publication, author, author’s affiliation country and field of study.

- Characteristics of the intervention:

- Classification as evaluated or non-evaluated.

- Research stage: education, grant writing, protocol writing, manuscript writing, submission, journal peer review, copyediting and postpublication.

- Rationale of the intervention, which refers to the deduced reasons why the intervention is evaluated or proposed.

- For evaluated interventions: details of the intervention, study design (eg, RCT, before–after, etc), RGs considered and format (checklist, bullet points and/or examples), period of intervention, number of journals and articles involved, effect size of the intervention on adherence to RGs and measure used to assess this effect.

Relevant conclusions.

Two reviewers (DB, JJK) independently performed data extraction for all studies except for the individual studies of the two systematic reviews evaluating journal endorsement of RGs,3 6 since none of these studies described further interventions and their results had already been reported in these reviews. Discrepancies between reviewers were discussed and solved by consensus.

Data synthesis

Following data extraction, interventions to improve adherence to RGs were categorised as follows:

Training on the practical use of RGs: mentoring of different stakeholders on the practical use of RGs.

Enhancing accessibility and understanding: dissemination of RGs and the improvement of authors’ understanding of their content.

Encouraging adherence: suggestions and tools to facilitate compliance.

Checking adherence and providing feedback: checking the level of compliance and indicating incorrect or missing items.

Involvement of experts: interaction and cooperation on methodology and reporting.

One reviewer (DB) performed the initial categorisation, which was verified and refined by the other two reviewers (JJK and EC).

Furthermore, we determined the existing gaps in research on the evaluation of interventions to improve adherence to RGs. More specifically, we identified which categories of interventions and which research stages have not been addressed so far in studies evaluating interventions.

We did not perform a meta-analysis of the observational studies assessing journal endorsement of RGs that were not included in the two systematic reviews previously mentioned.3 6 We considered that, for the purpose of this scoping review, these systematic reviews provided a reliable picture of the impact of this editorial intervention.

Deviations from the protocol

In order to better capture the most relevant aspects of the included studies, the original data extraction form proposed in the protocol was modified. We removed the healthcare area of the studies included, refined the research stages considered and included more details on the implementation of the evaluated interventions.

Patients and public involvement

No patients or public were involved in the study.

Results

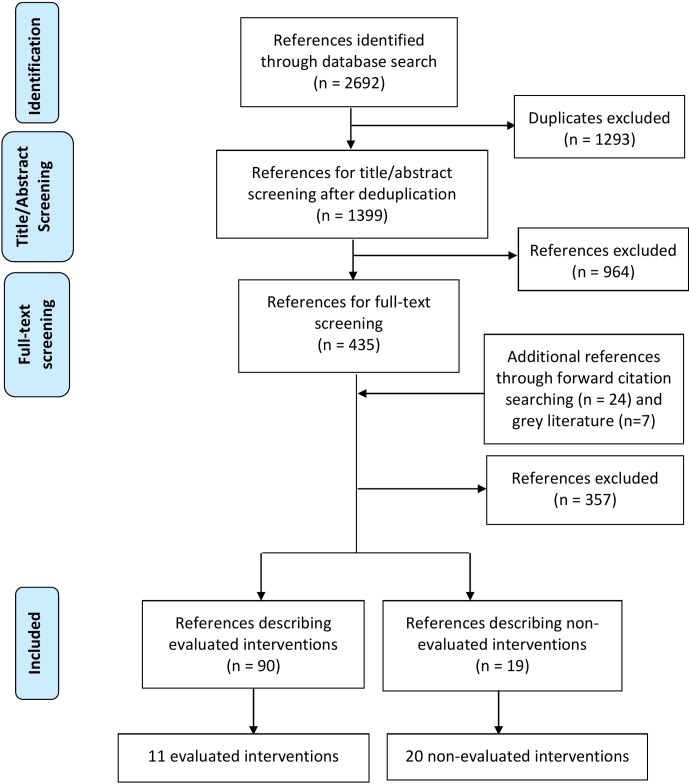

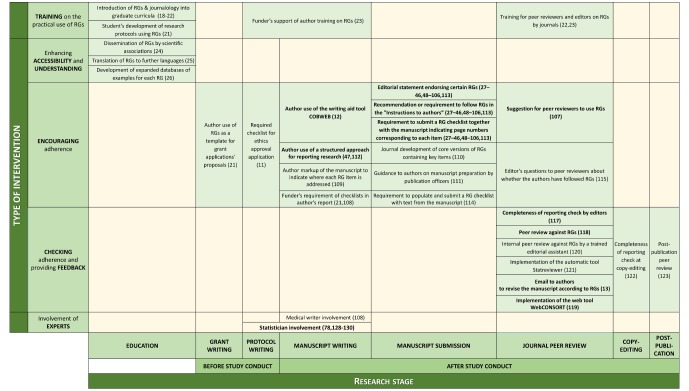

The database search yielded 1399 citations after deduplication (see figure 1). Screening of titles and abstracts resulted in a first classification, after which 435 papers were included for full-text review. We also reviewed the full text of 24 additional references found through forward citation searching. Furthermore, a grey literature search yielded seven additional references. Finally, 109 references were included. Some of these interventions appeared in more than one reference and some of the references contained more than one intervention. Ninety of these references (86 observational and 4 randomised studies) described 11 evaluated interventions and the other 19 (12 research studies, 2 editorials, 2 blogs, 1 commentary, 1 essay and 1 perspective) described 20 non-evaluated interventions. Figure 2 displays these 31 interventions according to their categorisation and the research stage where they can be performed. Moreover, table 1 shows all interventions in a tabular format together with their rationale. All interventions reported in this section were found in the literature and do not necessarily correspond to the personal ideas of the scoping review authors.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Figure 2.

Typology of interventions to improve adherence to RGs according to type of intervention and research stage. Evaluated interventions are shown in bold. CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; RGs, reporting guidelines.

Table 1.

Rationale of the interventions identified.

| Group | Intervention | Rationale |

| Training on the practical use of RGs | Introduction of RGs and journalology into graduate curricula18–22 | To introduce good research reporting habits early in young researchers’ scientific careers. |

| Student’s development of protocols for coursework and research using RGs21 | ||

| Funder’s support of author training on RGs23 | Authors, editors and peer reviewers have insufficient training in issues related to reporting. | |

| Training for peer reviewers and editors on RGs by journals22 23 | ||

| Enhancing accessibility and understanding | Dissemination of RGs by scientific associations24 | A large number of researchers are not aware of the existence of RGs. |

| Translation of RGs to further languages25 | Language barriers may affect the proper use of RGs. | |

| Development of expanded database of examples for each RG26 | Authors need more examples of good reporting to properly understand certain items. | |

| Encouraging adherence | Author use of RGs as a template for grant application proposals21 | Using RGs in early stages may facilitate completeness of reporting of published research. |

| Required checklist for ethics approval application11 | ||

| Funder’s requirement of checklists in author’s report21 108 | ||

| Author use of the writing aid tool COBWEB12 | (A) Authors need help to successfully adhere to RGs at the writing stage and (B) Dividing RG items into bullet points and providing examples might help. | |

| Author use of a structured approach for reporting research47 112 | (A) To help authors avoid omissions, (B) to aid reviewers and editors in appraising articles and (C) to allow more efficient data extraction during the systematic review process. | |

| Author mark-up of the manuscript to indicate where each RG item is addressed109 | ||

| Editorial statement endorsing certain RGs27–46 48–106 113 | Authors read editorial statements and follow ‘Instructions to authors’. | |

| Recommendation or requirement to follow RGs in the ‘Instructions to authors’27–46 48–106 113 | ||

| Requirement to submit an RG checklist together with the manuscript indicating page numbers corresponding to each item27–46 48–106 113 | Authors may not consider editorial statements or recommendations in ‘Instructions to authors’ to be important. Compulsory submission of checklists or text mark-up may encourage authors to be more compliant with RGs. | |

| Requirement to populate and submit an RG checklist with text from the manuscript114 | ||

| Journal development of core versions of RGs containing key items110 | Focusing on the most important items could be more effective than considering the whole checklist. | |

| Guidance to authors on manuscript preparation by publication officers111 | Trained journal officers may enhance authors’ compliance with RGs during manuscript preparation. | |

| Suggestion for peer reviewers to use RGs107 | Peer reviewers often do not detect reporting flaws. Therefore, they may need to follow a more systematic approach and use RGs. | |

| Editor’s questions to peer reviewers about whether the authors have followed RGs115 | ||

| Checking adherence and providing feedback | Completeness of reporting check by editors117 | Requiring checklists at submission does not guarantee adherence. Editors and peer reviewers have to check whether submitted papers are compliant with RGs. |

| Peer review against RGs118 | ||

| Internal peer review against RGs by a trained editorial assistant120 | It is extremely unlikely that the average clinical peer reviewer has the methodological expertise to check a paper against RGs. | |

| Implementation of the automatic tool Statreviewer121 | ||

| Email to authors to revise the manuscript according to RGs13 | It might be more effective to ask authors for adherence to RGs during the revision process because they will do anything to get their paper published. | |

| Implementation of the tool WebCONSORT119 | ||

| Completeness of reporting check at copyediting122 | Copyediting and postpublication offer alternate time points to improve adherence to RGs. | |

| Postpublication peer review123 | ||

| Involvement of experts | Statistician involvement (78 128–130) | Professionals with specific knowledge of RGs might help authors when designing, conducting or reporting their research. |

Medical writer involvement.108

COBWEB, CONSORT-based web tool; CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

RGs, reporting guidelines.

Among the 11 evaluated interventions identified, we found a variety of measures used to assess their effect on adherence to RGs, including:

Score for completeness of reporting for each paper, either assigning different or equal weights to RG items, on a 0–10 scale.

Percentage of items reported for each paper.

Percentage of compliance per RG item.

Score for the Manuscript Quality Assessment Instrument17 for each paper.

Due to the heterogeneity of these measures and for the sake of clarity, we prefer to omit the information on the exact effect sizes in the main body of the manuscript and show it in online supplementary file 2, together with the implementation details of the evaluated interventions. In this way, these effects can be understood in an appropriate context.

bmjopen-2018-026589supp002.pdf (137.1KB, pdf)

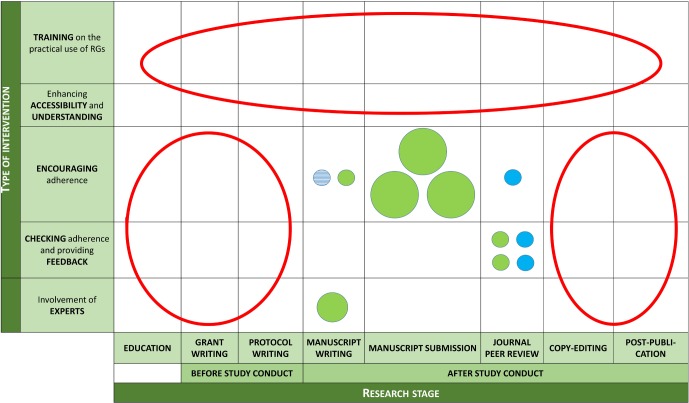

Research gaps identified (see figure 3) included the evaluation of interventions (1) on training on the use of RGs and improving understanding of these, (2) at early stages of research (education, grant writing or protocol writing) and (3) after the final acceptance of the manuscript (copyediting or postpublication peer review).

Figure 3.

Gaps in research on the evaluation of interventions to improve adherence to RGs. Each circle represents one intervention. Variables displayed: (1) Circle size: number of studies evaluating each intervention (bigger=more studies); (2) Circle colour: study design of those studies (blue for RCTs and green for observational studies) and (3) Circle fill: kind of RG implementation (plain for checklist and stripes for bullet points and examples). Research gaps are highlighted in red. RCTs, randomised controlled trials; RGs, reporting guidelines.

Hereafter, we describe the interventions found for each category (table 1 and online supplementary file 2 summarise these interventions).

Training on the practical use of RGs

Four non-evaluated interventions related to educating different stakeholders on the practical use of RGs were found.18–23

In a first step, health profession schools could incorporate RGs into curricula that address research methodology and publication standards.18–22 In line with this, students could develop protocols for coursework and research using RGs such as Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (randomised trials) and PRISMA-Protocol (systematic reviews), and educators may encourage adherence to those guidelines and grade the protocols using them.21 For their part, funders may consider supporting author training on RGs.23 Finally, journals or publishers may consider investing resources in training editors and reviewers on the content and use of RGs.22 23

Enhancing accessibility and understanding

We identified three non-evaluated interventions focused on increasing the awareness of the existence of RGs, as well as the authors’ understanding of the content of these.24–26

First, international scientific associations may play an important role in disseminating and popularising RGs to large audiences.24 Second, RG developers might consider translating them to new languages that have not been addressed yet.25 Finally, further databases of examples of good reporting for different RGs that are accessible to authors can be developed, as has been done for CONSORT.26

Encouraging adherence

Fourteen interventions found were associated with different strategies to facilitate compliance with RGs.11 12 21 27–115 Six of these were evaluated.12 27–107 113

Funders might require authors to use RGs as a template for grant application proposals.21 Later on, research ethics boards may require that protocols submitted for ethical approval clearly state which RGs the study will be using based on the study design, and that RG checklists are part of the application for ethics approval.11 Funders could also encourage adherence to RGs by asking for RG checklists as part of the authors’ report.21 108

One initiative to support authors adhering to RGs at the writing stage of the manuscript has been COBWEB, a writing aid tool that aims to help authors adequately combine the different extensions of the CONSORT statement.12 This tool divided the CONSORT items into bullet points showing the key elements that need to be reported together with examples of adequate reporting. The impact of COBWEB was evaluated in a randomised trial that showed a large effect of this intervention12 (see online supplementary file 2 for more details about this and other evaluated interventions). A second option to support authors at manuscript writing is that they follow a more structured approach. For example, ClinicalTrials.gov requires authors to report key information in a tabular format when registering a study or making available its results.116 This has been shown to be effective: some results posted on this platform, especially harms, are more complete than those in corresponding journal articles reporting the same trials.47 Another possibility to improve the structure of manuscripts is to include new subheadings corresponding to different RG items within the traditional format introduction, methods, results and discussion, as the American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics (AJO-DO) proposed.112 Finally, authors may also avoid omissions when writing the manuscript if mark-up the text and highlight where each item of the relevant checklist is addressed.109

At the manuscript submission stage, different editorial actions have been taken to improve adherence to RGs. The most popular is what has traditionally been defined as journal endorsement of RGs, which is usually defined as one or more of the three following interventions: (1) journal editorial statement endorsing certain RGs; (2) requirement or recommendation in journal’s ‘Instructions to Authors’ to follow certain RGs when preparing their manuscript or (3) requirement for authors to submit the appropriate RG checklist together with their manuscript indicating page numbers corresponding to each item.6 Dozens of observational studies have explored the possible effect of journal endorsement of different RGs in different clinical areas.27–46 48–106 113 A recent systematic review focused on CONSORT evaluations showed relative but suboptimal improvements in the completeness of reporting in journals by following the aforementioned policies,6 while another systematic review considering nine other guidelines showed no improvements.3

Journals might also consider other strategies to enhance adherence to RGs at submission. A first option could be to develop shorter, core versions of RGs containing key items, which could be provided to authors as part of the submission process.110 Second, they might introduce publication officers in order to provide guidance to authors on preparing manuscripts for submission.111 Third, editors may ask authors to populate the relevant checklist with text from their manuscript and not accept a submission unless this is provided.114

Finally, editors may suggest that peer reviewers use RGs.107 In addition, by asking peer reviewers questions about whether the author has followed RGs, this might be an indirect way to encourage them.115

Checking adherence and providing feedback

Eight interventions were related to monitoring level of compliance with RGs of the manuscripts and providing instructions to authors on how to improve the reporting of missing or incorrect items.13 117–123 Four of them were evaluated.13 117–119

Some journals have opted for implementing RGs at peer review. First, an associate editor may assess manuscripts for adherence to the relevant RG and ask authors to make changes accordingly.117 This process may be repeated until the associate editor thinks that the manuscript can move to the next step of the review process, leading to an editorial decision. This intervention was evaluated at the AJO-DO and showed satisfactory results: 33 of 37 items reached perfect compliance.117 Second, peer reviewers could also assess the manuscripts against the appropriate checklist.118 While the observed effect of this intervention was slightly positive, it was smaller than hypothesised. In fact, investigators pointed out that authors tended to comply better with suggestions coming from standard reviews rather than from reviews against RGs, implying that it might be difficult to adhere to high methodological standards at late stages of research if these standards are not considered earlier in the research process. Third, journals could also ask trained editorial assistants to check manuscripts against RGs120 or to implement automatic peer-review tools such as StatReviewer,124 software that automatically checks adherence to RGs and evaluates the appropriate use and reporting of statistical tests.121 Currently, its performance is being assessed through a pilot trial in collaboration with four BioMed Central Journals.121 In any of those cases, emails could be sent to authors asking them to revise the manuscript according to guidelines.13 To do this, the EQUATOR network has provided standard letters that can be used (1) after checks by an editor or a single peer reviewer, (2) after full peer review or (3) alongside acceptance.125 Furthermore, at the time of author revision of the manuscript, Hopewell et al found no significant effect when incorporating WebCONSORT, a web-based tool that generates a unique list of items customised to the trial design, to the revision process of journals that endorsed CONSORT but had no active policy for implementing it.119 Finally, in a late stage of the publication process, copyediting of the manuscript could also ensure that all items are covered.122

Once the paper is published, the scientific community could use online platforms of postpublication peer review such as PubPeer126 or ScienceOpen127 to evaluate the adherence to RGs of published articles and to provide feedback to authors.123

Involvement of experts

Two interventions identified implied interaction and cooperation between authors and experts on methodology and reporting at different stages of research.78 108 128–130 One of them was evaluated.78 128–130

On the one hand, statisticians (or epidemiologists or other quantitative methodologists) may get involved in the design, conduct or reporting of the study might contribute to properly reporting key areas such as sample size calculation, randomisation, blinding and appropriate statistical analysis.129 While three studies found a statistically significant positive relationship between CONSORT scores and statistician involvement,78 129 130 another one did not.128 On the other hand, it has been hypothesised that the involvement of medical writers during the manuscript writing stage of research could improve the completeness of reporting.108

Interventions described in papers coauthored by authors of this scoping review

Twenty-five (of 109) included references describing 21 (of 31) included interventions were coauthored by at least one of the authors of this scoping review.12 13 20–23 26 47 54 55 63 67 74 76 80 104 107 111 114 115 117–120 123

Discussion

In this scoping review, we identified 31 interventions to improve adherence to RGs. We have also determined the gaps in research on the evaluation of this type of interventions. By considering a wide range of RGs as well as their extensions and merging the evidence found in the published and grey literature, this review provides a broad picture of how the problem of enhancing adherence to RGs has been tackled so far and could be faced in the future.

This study reveals that most published research aimed at improving adherence to RGs has been conducted in journals. Typically, journal strategies range from making available editorial statements that endorse certain RGs, recommending or requiring authors to follow RGs in the ‘Instructions to authors’, and requiring authors to submit an RG checklist together with the manuscript, with page numbers indicated for each item. However, these strategies have been shown not to have the desired effect.3 6 131 Recent research has called for more active and enforced journal policies throughout the editorial process, such as requiring the use of structured approaches with new subheadings adapted to different kinds of study designs,112 which was also found to be beneficial in a new study outside of our search period132; providing guidance on manuscript preparation111; making sure the peer-review process involves editorial assistants who have specific training on reporting issues120 and implementing automatic peer-review tools.121 Journals will vary in their ability to make some of these strategies effective, depending on factors such as their resources, their guidelines to peer reviewers and the dedication of their editors—many editors and editorial staff work part time and have a limited amount of time.

Moreover, editors’ education and performance should be improved. A recent study pointed out that more than one-third (39%) of the manuscripts classified as randomised trials by the editorial staff were not actually randomised trials.119 133 Consequently, it seems difficult to improve author and peer reviewer adherence to RGs if journal gatekeepers are not properly trained in methodological and reporting issues.

Apart from journals, editors and peer reviewers, other key stakeholders such as medical schools, research funders, universities and other research institutions should also take responsibility regarding this issue. This scoping review provides some strategies to follow. However, as the problem is complex and the possible interventions are varied, enhancing the completeness of reporting most likely depends not so much on any isolated action but on a set of strategies by several different stakeholders. These could be enacted at different stages of research, from education to article postpublication.

For interventions aiming to improve adherence to RGs, we should require the same level of evidence that we require for interventions to improve health. For this reason, it is striking that we found only four published randomised trials that evaluated interventions to improve adherence to RGs.12 107 118 119 Among these trials, statistically significant effect of the intervention was only observed for the use of the writing aid tool for authors COBWEB.12 While performing an additional review against RGs showed slightly positive but not significant effect,118 suggesting the use of RGs to peer reviewers107 or implementing at the process of author revision of the manuscript the web-based tool WebCONSORT showed no benefit.119 The rest of the evaluations of interventions found (86 of 90) were observational studies, whose results are subject to the influence of confounding factors. As already mentioned, the impact of journal endorsement on completeness of reporting was suboptimal.3 6 However, completeness of reporting improved remarkably when RGs were actively implemented by editors (eg, if editors perform a completeness of reporting check of the manuscript117) and when research results were posted in a tabular format without discussion or conclusions.47 Future randomised trials should consider evaluating these interventions or addressing some of the research gaps identified in this review, such as improving adherence to RGs at the grant application or protocol writing stages.

A few of the interventions found in this review were shown to enhance adherence to RGs. However, it is noteworthy there is no evidence that some successful interventions12 117 have been implemented more widely later. For this reason, more resources and efforts are needed to further implement these interventions in other settings, evaluate the effect, and share the results with the scientific community. In any case, it is important to keep in mind that contemporary publication culture may harm the potential improvements in reporting quality. This could result from the fact that most scientists feel that the primary evaluation tool of their research is the quantity of their scientific output rather than its quality134; and such attitudes may undermine the potential effect of any intervention to improve adherence to RGs.

Our scoping review has some limitations. First, we did not formally assess the methodological quality of the studies that evaluated interventions. Second, restricting to certain databases or not having standard search terms for the databases searched may have excluded relevant publications. Third, it is possible that we could have missed evidence of possible interventions that may have never been reflected in the published or grey literature but are instead used in practice and continue to be used. For example, journals might be applying specific editorial strategies that are not publicly available on their websites or in the published literature.

Conclusion

Improving adherence to RGs is one of the key issues in order to enhance complete and accurate reporting and therefore reduce waste in research.

Different stakeholders—such as research funders, ethics boards and journals—should consider implementing and evaluating some of the interventions identified in this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the MiRoR Project (http://miror-ejd.eu/) and Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions for their support. The authors also thank Matt Elmore for editorial help. This review is part of a larger project whose next goals are (1) to capture editors’ perceptions on the barriers and facilitators of some promising interventions identified in this review, (2) to explore new possible interventions and (3) to evaluate one of these interventions in collaboration with BMJ Open.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to conceptualising and designing the study. DB, EC and JJK independently performed screening. DB and JJK independently performed data extraction. DB performed initial data synthesis and EC, IB, DM, DA and JJK refined it. DB drafted the manuscript. EC, IB, DM, DA and JJK made major revisions. Due to the strong involvement of JJK and EC at several different stages of the study, all authors agreed to consider them joint senior authors of the scoping review, although EC was the only senior author of the protocol. All authors read and approved the final manuscript, which was completed in April 2018. DA passed away in June 2018 and therefore could not approve the revised manuscript (November 2018).

Funding: This scoping review belongs to the ESR 14 research project from the Methods in Research on Research (MiRoR) project (http://miror-ejd.eu/), which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 676207. DM is supported through a University Research Chair (University of Ottawa).

Competing interests: DA and DM are directors of the UK and Canadian EQUATOR Centres, respectively. IB is deputy director of French EQUATOR Centre.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet 2009;374:86–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60329-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. EQUATOR Network. Library for health research reporting. http://www.equator-network.org/resource-centre/library-of-health-research-reporting.

- 3. Stevens A, Shamseer L, Weinstein E, et al. . Relation of completeness of reporting of health research to journals' endorsement of reporting guidelines: systematic review. BMJ 2014;348:g3804 10.1136/bmj.g3804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c332 10.1136/bmj.c332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Plint AC, Moher D, Morrison A, et al. . Does the CONSORT checklist improve the quality of reports of randomised controlled trials? A systematic review. Med J Aust 2006;185:263–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Turner L, Shamseer L, Altman DG, et al. . Does use of the CONSORT Statement impact the completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials published in medical journals? A Cochrane review. Syst Rev 2012;1:60 10.1186/2046-4053-1-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bereza BG, Machado M, Einarson TR, et al. . Assessing the reporting and scientific quality of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of treatments for anxiety disorders. Ann Pharmacother 2008;42:1402–9. 10.1345/aph.1L204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fung AE, Palanki R, Bakri SJ, et al. . Applying the CONSORT and STROBE statements to evaluate the reporting quality of neovascular age-related macular degeneration studies. Ophthalmology 2009;116:286–96. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rios LP, Odueyungbo A, Moitri MO, et al. . Quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials in general endocrinology literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:3810–6. 10.1210/jc.2008-0817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shea B, Bouter LM, Grimshaw JM, et al. . Scope for improvement in the quality of reporting of systematic reviews. From the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group. J Rheumatol 2006;33:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Samaan Z, Mbuagbaw L, Kosa D, et al. . A systematic scoping review of adherence to reporting guidelines in health care literature. J Multidiscip Healthc 2013;6:169–88. 10.2147/JMDH.S43952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barnes C, Boutron I, Giraudeau B, et al. . Impact of an online writing aid tool for writing a randomized trial report: the COBWEB (Consort-based WEB tool) randomized controlled trial. BMC Med 2015;13:221 10.1186/s12916-015-0460-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hopewell S, Ravaud P, Baron G, et al. . Effect of editors’ implementation of CONSORT guidelines on the reporting of abstracts in high impact medical journals: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ 2012;344:e4178 10.1136/bmj.e4178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blanco D, Kirkham JJ, Altman DG, et al. . Interventions to improve adherence to reporting guidelines in health research: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017551 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reviewers’ Manual. 2015; Available from: www.joannabriggs.org

- 16. EQUATOR Network. Available from: http://www.equator-network.org/

- 17. Goodman SN, Berlin J, Fletcher SW, et al. . Manuscript quality before and after peer review and editing at Annals of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med 1994;121:11–21. 10.7326/0003-4819-121-1-199407010-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ma B, Qi GQ, Lin XT, et al. . Epidemiology, quality, and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews of acupuncture interventions published in Chinese journals. J Altern Complement Med 2012;18:813–7. 10.1089/acm.2011.0274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Larson EL, Cortazal M. Publication guidelines need widespread adoption. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:239–46. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sarkis-Onofre R, Cenci MS, Moher D, et al. . Research reporting guidelines in dentistry: A survey of editors. Braz Dent J 2017;28:3–8. 10.1590/0103-6440201601426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. . the PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Simera I, Moher D, Hirst A, et al. . Transparent and accurate reporting increases reliability, utility, and impact of your research: reporting guidelines and the EQUATOR Network. BMC Med 2010;8:24 10.1186/1741-7015-8-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Glasziou P, Altman DG, Bossuyt P, et al. . Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet 2014;383:267–76. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62228-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Verbeek J. Moose Consort Strobe and Miame Stard Remark or how can we improve the quality of reporting studies. Scand J Work Environ Health 2008;34:165–7. 10.5271/sjweh.1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim KH, Kang JW, Lee MS, et al. . Assessment of the quality of reporting in randomised controlled trials of acupuncture in the Korean literature using the CONSORT statement and STRICTA guidelines. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005068 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. . Resources for authors of reports of randomized trials: harnessing the wisdom of authors, editors, and readers. Trials 2011;12:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Faunce TA, Buckley NA. Of consents and CONSORTs: reporting ethics, law, and human rights in RCTs involving monitored overdose of healthy volunteers pre and post the "CONSORT" guidelines. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2003;41:93–9. 10.1081/CLT-120019120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Halpern SH, Darani R, Douglas MJ, et al. . Compliance with the CONSORT checklist in obstetric anaesthesia randomised controlled trials. Int J Obstet Anesth 2004;13:207–14. 10.1016/j.ijoa.2004.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hewitt C, Hahn S, Torgerson DJ, et al. . Adequacy and reporting of allocation concealment: review of recent trials published in four general medical journals. BMJ 2005;330:1057–8. 10.1136/bmj.38413.576713.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Greenfield ML, Rosenberg AL, O’Reilly M, et al. . The quality of randomized controlled trials in major anesthesiology journals. Anesth Analg 2005;100:1759–64. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000150612.71007.A3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Llorca J, Martínez-Sanz F, Prieto-Salceda D, et al. . Quality of controlled clinical trials on glaucoma and intraocular high pressure. J Glaucoma 2005;14:190–5. 10.1097/01.ijg.0000159124.57112.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Haahr MT, Hróbjartsson A. Who is blinded in randomized clinical trials? A study of 200 trials and a survey of authors. Clin Trials 2006;3:360–5. 10.1177/1740774506069153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kober T, Trelle S, Engert A. Reporting of randomized controlled trials in Hodgkin lymphoma in biomedical journals. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98:620–5. 10.1093/jnci/djj160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Biondi-Zoccai GG, Lotrionte M, Abbate A, et al. . Compliance with QUOROM and quality of reporting of overlapping meta-analyses on the role of acetylcysteine in the prevention of contrast associated nephropathy: case study. BMJ 2006;332:202–9. 10.1136/bmj.38693.516782.7C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Balasubramanian SP, Wiener M, Alshameeri Z, et al. . Standards of reporting of randomized controlled trials in general surgery: can we do better? Ann Surg 2006;244:663–7. 10.1097/01.sla.0000217640.11224.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dias S, McNamee R, Vail A, et al. . Evidence of improving quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials in subfertility. Hum Reprod 2006;21:2617–27. 10.1093/humrep/del236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smidt N, Rutjes AW, van der Windt DA, et al. . The quality of diagnostic accuracy studies since the STARD statement: has it improved? Neurology 2006;67:792–7. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000238386.41398.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Coppus SF, van der Veen F, Bossuyt PM, et al. . Quality of reporting of test accuracy studies in reproductive medicine: impact of the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) initiative. Fertil Steril 2006;86:1321–9. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.03.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tiruvoipati R, Balasubramanian SP, Atturu G, et al. . Improving the quality of reporting randomized controlled trials in cardiothoracic surgery: the way forward. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;132:233–40. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.10.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mahoney J, Ellison J. Assessing the quality of glucose monitor studies: a critical evaluation of published reports. Clin Chem 2007;53:1122–8. 10.1373/clinchem.2006.083493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Poolman RW, Abouali JA, Conter HJ, et al. . Overlapping systematic reviews of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction comparing hamstring autograft with bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft: why are they different? J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89:1542–52. 10.2106/00004623-200707000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Spring B, Pagoto S, Knatterud G, et al. . Examination of the analytic quality of behavioral health randomized clinical trials. J Clin Psychol 2007;63:53–71. 10.1002/jclp.20334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Agha R, Cooper D, Muir G. The reporting quality of randomised controlled trials in surgery: a systematic review. Int J Surg 2007;5:413–22. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2007.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kane RL, Wang J, Garrard J. Reporting in randomized clinical trials improved after adoption of the CONSORT statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:241–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Paranjothy B, Shunmugam M, Azuara-Blanco A, et al. . The quality of reporting of diagnostic accuracy studies in glaucoma using scanning laser polarimetry. J Glaucoma 2007;16:670–5. 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3180457c6d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Johnson ZK, Siddiqui MA, Azuara-Blanco A, et al. . The quality of reporting of diagnostic accuracy studies of optical coherence tomography in glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2007;114:1607–12. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Riveros C, Dechartres A, Perrodeau E, et al. . Timing and completeness of trial results posted at ClinicalTrials.gov and published in journals. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001566 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hind D, Booth A. Do health technology assessments comply with QUOROM diagram guidance? An empirical study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007;7:49 10.1186/1471-2288-7-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lee PE, Fischer HD, Rochon PA, et al. . Published randomized controlled trials of drug therapy for dementia often lack complete data on harm. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:1152–60. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pat K, Dooms C, Vansteenkiste J, et al. . Systematic review of symptom control and quality of life in studies on chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: how CONSORTed are the data? Lung Cancer 2008;62:126–38. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Folkes A, Urquhart R, Grunfeld E. Are leading medical journals following their own policies on CONSORT reporting? Contemp Clin Trials 2008;29:843–6. 10.1016/j.cct.2008.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sinha S, Sinha S, Ashby E, et al. . Quality of reporting in randomized trials published in high-quality surgical journals. J Am Coll Surg 2009;209:565–71. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Freeman K, Szczepura A, Osipenko L, et al. . Non-invasive fetal RHD genotyping tests: a systematic review of the quality of reporting of diagnostic accuracy in published studies. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2009;142:91–8. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Uetani K, Nakayama T, Ikai H, et al. . Quality of reports on randomized controlled trials conducted in Japan: evaluation of adherence to the CONSORT statement. Intern Med 2009;48:307–13. 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ethgen M, Boutron L, Steg PG, et al. . Quality of reporting internal and external validity data from randomized controlled trials evaluating stents for percutaneous coronary intervention. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:24 10.1186/1471-2288-9-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Krzych LJ, Liszka L. No improvement in studies reporting the diagnostic accuracy of B-type natriuretic peptide. Med Sci Monit 2009;15:SR5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pagoto SL, Kozak AT, John P, et al. . Intention-to-treat analyses in behavioral medicine randomized clinical trials. Int J Behav Med 2009;16:316–22. 10.1007/s12529-009-9039-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kidwell CS, Liebeskind DS, Starkman S, et al. . Trends in acute ischemic stroke trials through the 20th century. Stroke 2001;32:1349–59. 10.1161/01.STR.32.6.1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Han C, Kwak KP, Marks DM, et al. . The impact of the CONSORT statement on reporting of randomized clinical trials in psychiatry. Contemp Clin Trials 2009;30:116–22. 10.1016/j.cct.2008.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Alvarez F, Meyer N, Gourraud PA, et al. . CONSORT adoption and quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials: a systematic analysis in two dermatology journals. Br J Dermatol 2009;161:1159–65. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09382.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wei X, Tiejun L, Cheng W. Current situation on the reporting quality of randomized controlled trials in 5 leading Chinese medical journals. J Med Coll PLA 2009;24:105–11. 10.1016/S1000-1948(09)60025-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ladd BO, McCrady BS, Manuel JK, et al. . Improving the quality of reporting alcohol outcome studies: effects of the CONSORT statement. Addict Behav 2010;35:660–6. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yu LM, Chan AW, Hopewell S, et al. . Reporting on covariate adjustment in randomised controlled trials before and after revision of the 2001 CONSORT statement: a literature review. Trials 2010;11:59 10.1186/1745-6215-11-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Areia M, Soares M, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Quality reporting of endoscopic diagnostic studies in gastrointestinal journals: where do we stand on the use of the STARD and CONSORT statements? Endoscopy 2010;42:138–47. 10.1055/s-0029-1243846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Delaney M, Meyer E, Cserti-Gazdewich C, et al. . A systematic assessment of the quality of reporting for platelet transfusion studies. Transfusion 2010;50:2135–44. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02691.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Flint HE, Harrison JE. How well do reports of clinical trials in the orthodontic literature comply with the CONSORT statement? J Orthod 2010;37:250–61. 10.1179/14653121043191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hopewell S, Dutton S, Yu LM, et al. . The quality of reports of randomised trials in 2000 and 2006: comparative study of articles indexed in PubMed. BMJ 2010;340:c723 10.1136/bmj.c723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ernst E, Hung SK CY. NCCAM-funded RCTs of herbal medicines: An independent, critical assessment. Perfusion 2011;24:89–102 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288438592_NCCAM-funded_RCTs_of_herbal_medicines_An_independent_critical_assessment. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sánchez-Thorin JC, Cortés MC, Montenegro M, et al. . The quality of reporting of randomized clinical trials published in Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2001;108:410–5. 10.1016/S0161-6420(00)00500-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Selman TJ, Morris RK, Zamora J, et al. . The quality of reporting of primary test accuracy studies in obstetrics and gynaecology: application of the STARD criteria. BMC Womens Health 2011;11:8 10.1186/1472-6874-11-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Parsons NR, Hiskens R, Price CL, et al. . A systematic survey of the quality of research reporting in general orthopaedic journals. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:1154–9. 10.1302/0301-620X.93B9.27193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kiehna EN, Starke RM, Pouratian N, et al. . Standards for reporting randomized controlled trials in neurosurgery. J Neurosurg 2011;114:280–5. 10.3171/2010.8.JNS091770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Strech D, Soltmann B, Weikert B, et al. . Quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials of pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorders: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry 2011;72:1214–21. 10.4088/JCP.10r06166yel [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Turner LA, Singh K, Garritty C, et al. . An evaluation of the completeness of safety reporting in reports of complementary and alternative medicine trials. BMC Complement Altern Med 2011;11:67 10.1186/1472-6882-11-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Haidich AB, Birtsou C, Dardavessis T, et al. . The quality of safety reporting in trials is still suboptimal: survey of major general medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:124–35. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Gray R, Sullivan M, Altman DG, et al. . Adherence of trials of operative intervention to the CONSORT statement extension for non-pharmacological treatments: a comparative before and after study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2012;94:388–94. 10.1308/003588412X13171221592339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Cornelius VR, Sauzet O, Williams JE, et al. . Adverse event reporting in randomised controlled trials of neuropathic pain: considerations for future practice. Pain 2013;154:213–20. 10.1016/j.pain.2012.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Diaz-Ordaz K, Froud R, Sheehan B, et al. . A systematic review of cluster randomised trials in residential facilities for older people suggests how to improve quality. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:127 10.1186/1471-2288-13-127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Geha NN, Moseley AM, Elkins MR, et al. . The quality and reporting of randomized trials in cardiothoracic physical therapy could be substantially improved. Respir Care 2013;58:1899–906. 10.4187/respcare.02379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Moher D, Jones A, Lepage L. CONSORT Group (Consolidated Standards for Reporting of Trials). Use of the CONSORT statement and quality of reports of randomized trials: a comparative before-and-after evaluation. JAMA 2001;285:1992–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Liu LQ, Morris PJ, Pengel LH, et al. . Compliance to the CONSORT statement of randomized controlled trials in solid organ transplantation: a 3-year overview. Transpl Int 2013;26:300–6. 10.1111/tri.12034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Panic N, Leoncini E, de Belvis G, et al. . Evaluation of the endorsement of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement on the quality of published systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS One 2013;8:e83138 10.1371/journal.pone.0083138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Fleming PS, Seehra J, Polychronopoulou A, et al. . A PRISMA assessment of the reporting quality of systematic reviews in orthodontics. Angle Orthod 2013;83:158–63. 10.2319/032612-251.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Péron J, Maillet D, Gan HK, et al. . Adherence to CONSORT adverse event reporting guidelines in randomized clinical trials evaluating systemic cancer therapy: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3957–63. 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.3981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Tunis AS, McInnes MD, Hanna R, et al. . Association of study quality with completeness of reporting: have completeness of reporting and quality of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in major radiology journals changed since publication of the PRISMA statement? Radiology 2013;269:413–26. 10.1148/radiol.13130273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Maclean EN, Stone IS, Ceelen F, et al. . Reporting standards in cardiac MRI, CT, and SPECT diagnostic accuracy studies: analysis of the impact of STARD criteria. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;15:691–700. 10.1093/ehjci/jet277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Baker D, Lidster K, Sottomayor A, et al. . Two years later: journals are not yet enforcing the ARRIVE guidelines on reporting standards for pre-clinical animal studies. PLoS Biol 2014;12:e1001756 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Choi J, Jun JH, Kang BK, et al. . Endorsement for improving the quality of reports on randomized controlled trials of traditional medicine journals in Korea: a systematic review. Trials 2014;15:429 10.1186/1745-6215-15-429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Walther S, Schueler S, Tackmann R, et al. . Compliance with STARD checklist among studies of coronary CT angiography: systematic review. Radiology 2014;271:74–86. 10.1148/radiol.13121720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ghimire S, Kyung E, Lee H, et al. . Oncology trial abstracts showed suboptimal improvement in reporting: a comparative before-and-after evaluation using CONSORT for Abstract guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:658–66. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Devereaux PJ, Manns BJ, Ghali WA, et al. . The reporting of methodological factors in randomized controlled trials and the association with a journal policy to promote adherence to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist. Control Clin Trials 2002;23:380–8. 10.1016/S0197-2456(02)00214-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Song TJ, Leng HF, Zhong LL, et al. . CONSORT in China: past development and future direction. Trials 2015;16:243 10.1186/s13063-015-0769-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Stevely A, Dimairo M, Todd S, et al. . An Investigation of the Shortcomings of the CONSORT 2010 Statement for the Reporting of Group Sequential Randomised Controlled Trials: A Methodological Systematic Review. PLoS One 2015;10:e0141104 10.1371/journal.pone.0141104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Adie S, Ma D, Harris IA, et al. . Quality of conduct and reporting of meta-analyses of surgical interventions. Ann Surg 2015;261:685–94. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Jull A, Aye PS. Endorsement of the CONSORT guidelines, trial registration, and the quality of reporting randomised controlled trials in leading nursing journals: A cross-sectional analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2015;52:1071–9. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Bearn DR, Alharbi F. Reporting of clinical trials in the orthodontic literature from 2008 to 2012: observational study of published reports in four major journals. J Orthod 2015;42:186–91. 10.1179/1465313315Y.0000000011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Agha RA, Fowler AJ, Limb C, et al. . Impact of the mandatory implementation of reporting guidelines on reporting quality in a surgical journal: A before and after study. Int J Surg 2016;30:169–72. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.04.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Pouwels KB, Widyakusuma NN, Groenwold RH, et al. . Quality of reporting of confounding remained suboptimal after the STROBE guideline. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;69:217–24. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Rao A, Brück K, Methven S, et al. . Quality of reporting and study design of ckd cohort studies assessing mortality in the elderly before and after strobe: A systematic review. PLoS One 2016;11:e0155078 10.1371/journal.pone.0155078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Grob ATM, van der Vaart LR, Withagen MIJ, et al. . Quality of reporting of diagnostic accuracy studies on pelvic floor three-dimensional transperineal ultrasound: a systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017;50:451–7. 10.1002/uog.17390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Rikos D, Dardiotis E, Tsivgoulis G, et al. . Reporting quality of randomized-controlled trials in multiple sclerosis from 2000 to 2015, based on CONSORT statement. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2016;9:135–9. 10.1016/j.msard.2016.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Montori VM, Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, et al. . In the dark: the reporting of blinding status in randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:787–90. 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00446-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Bigna JJ, Um LN, Nansseu JR. A comparison of quality of abstracts of systematic reviews including meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in high-impact general medicine journals before and after the publication of PRISMA extension for abstracts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 2016;5:174 10.1186/s13643-016-0356-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Sarkis-Onofre R, Poletto-Neto V, Cenci MS, et al. . Impact of the CONSORT Statement endorsement in the completeness of reporting of randomized clinical trials in restorative dentistry. J Dent 2017;58:54–9. 10.1016/j.jdent.2017.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Tharyan P, Premkumar TS, Mathew V, et al. . Editorial policy and the reporting of randomized controlled trials: a survey of instructions for authors and assessment of trial reports in Indian medical journals (2004-05). Natl Med J India 2008;21:62–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Lai TY, Wong VW, Lam RF, et al. . Quality of reporting of key methodological items of randomized controlled trials in clinical ophthalmic journals. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2007;14:390–8. 10.1080/09286580701344399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Cobo E, Selva-O’Callagham A, Ribera JM, et al. . Statistical reviewers improve reporting in biomedical articles: a randomized trial. PLoS One 2007;2:e332 10.1371/journal.pone.0000332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Implementing Reporting Guidelines: Why and How, for Journal Editors [Internet]. World Association of Medical Editors. https://wame.blog/2017/09/17/implementing-reporting-guidelines-why-and-how-for-journal-editors/.

- 109. Rupinski M, Zagorowicz E, Regula J, et al. . Randomized comparison of three palliative regimens including brachytherapy, photodynamic therapy, and APC in patients with malignant dysphagia (CONSORT 1a) (Revised II). Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:1612–20. 10.1038/ajg.2011.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Jilka RL. The Road to Reproducibility in Animal Research. J Bone Miner Res 2016;31:1317–9. 10.1002/jbmr.2881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Moher D, Altman DG. Four Proposals to Help Improve the Medical Research Literature. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001864 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Pandis N, Turpin DL. Enhancing CONSORT compliance for improved reporting of randomized controlled trials. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2014;145:1 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Hill CL, LaValley MP, Felson DT. Secular changes in the quality of published randomized clinical trials in rheumatology. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2002;46:779–84. 10.1002/art.512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, et al. . The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:777–84. 10.7326/M14-2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Hirst A, Altman DG. Are peer reviewers encouraged to use reporting guidelines? A survey of 116 health research journals. PLoS One 2012;7:e35621 10.1371/journal.pone.0035621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. ClinicalTrials.gov. National Library of Medicine (US). https://clinicaltrials.gov/.

- 117. Pandis N, Shamseer L, Kokich VG, et al. . Active implementation strategy of CONSORT adherence by a dental specialty journal improved randomized clinical trial reporting. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:1044–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Cobo E, Cortes J, Ribera JM, et al. . Effect of using reporting guidelines during peer review on quality of final manuscripts submitted to a biomedical journal: masked randomised trial. BMJ 2011;343:d6783 10.1136/bmj.d6783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Hopewell S, Boutron I, Altman DG, et al. . Impact of a web-based tool (WebCONSORT) to improve the reporting of randomised trials: results of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Med 2016;14:199 10.1186/s12916-016-0736-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Hopewell S, Collins GS, Boutron I, et al. . Impact of peer review on reports of randomised trials published in open peer review journals: retrospective before and after study. BMJ 2014;349:g4145 10.1136/bmj.g4145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. A peerless review?. Automating methodological and statistical review. https://blogs.biomedcentral.com/bmcblog/2016/05/23/peerless-review-automating-methodological-statistical-review/.

- 122. Mbuagbaw L, Thabane M, Vanniyasingam T, et al. . Improvement in the quality of abstracts in major clinical journals since CONSORT extension for abstracts: a systematic review. Contemp Clin Trials 2014;38:245–50. 10.1016/j.cct.2014.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Schriger DL, Altman DG. Inadequate post-publication review of medical research. BMJ 2010;341:c3803 10.1136/bmj.c3803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Statreviewer. Available from: http://www.statreviewer.com/

- 125. Tools and templates for implementing reporting guidelines. http://www.equator-network.org/toolkits/using-guidelines-in-journals/tools-and-templates-for-implementing-reporting-guidelines/.

- 126. PubPeer. Available from: https://pubpeer.com/

- 127. ScienceOpen. Available from: https://www.scienceopen.com/

- 128. Péron J, You B, Gan HK, et al. . Influence of statistician involvement on reporting of randomized clinical trials in medical oncology. Anticancer Drugs 2013;24:306–9. 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32835c3561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Pandis N, Polychronopoulou A, Eliades T. An assessment of quality characteristics of randomised control trials published in dental journals. J Dent 2010;38:713–21. 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Kloukos D, Papageorgiou SN, Doulis I, et al. . Reporting quality of randomised controlled trials published in prosthodontic and implantology journals. J Oral Rehabil 2015;42:914–25. 10.1111/joor.12325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Blanco D, Biggane AM, Cobo E. MiRoR network. Are CONSORT checklists submitted by authors adequately reflecting what information is actually reported in published papers?. Trials 2018;19:80 10.1186/s13063-018-2475-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Koletsi D, Fleming PS, Behrents RG, et al. . The use of tailored subheadings was successful in enhancing compliance with CONSORT in a dental journal. J Dent 2017;67:66–71. 10.1016/j.jdent.2017.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Cobo E, González JA. Taking advantage of unexpected WebCONSORT results. BMC Med 2016;14:204 10.1186/s12916-016-0758-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Tijdink JK, Schipper K, Bouter LM, et al. . How do scientists perceive the current publication culture? A qualitative focus group interview study among Dutch biomedical researchers. BMJ Open 2016;6:e008681 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026589supp001.pdf (79KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-026589supp002.pdf (137.1KB, pdf)