Abstract

Background

Depression is among the top mental health problems with a major contribution to the global burden of disease. This study aimed at identifying the latent factor structure and construct validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale.

Participants and setting

A cross-sectional survey of 562 adults aged 18 years and above who were randomly selected from the Eritrean refugee community living in the Mai-Aini refugee camp, Ethiopia.

Measures

The CES-D Scale, Primary Care PTSD (PC-PTSD) screener, premigration and postmigration living difficulties checklist, Oslo Social Support Scale (OSS-3), Sense of Coherence Scale (SoC-13), Coping Style Scale and fast alcohol screening test (FAST) were administered concurrently. Confirmatory factor analysis was employed to test prespecified factor structures of CES-D.

Result

First-order two factors with second-order common factor structure of CES-D (correlated error terms) yielded the best fit to the data (Comparative Fit Index =0.975; root mean square error of approximation=0.040 [90% CI 0.032 to 0.047]). The 16 items defining depressive affect were internally consistent (Cronbach’s α=0.932) and internal consistency of the 4 items defining positive affect was relatively weak (Cronbach’s α=0.703). These two latent factors have a weaker standardised covariance estimate of 33% (24% for women and 40% for men), demonstrating evidence of discriminant validity. CES-D is significantly associated with measures of adversities, specifically, premigration living difficulties (r=0.545, p<0.001) and postmigration living difficulties (r=0.47, p<0.001), PC-PTSD (r=0.538, p<0.001), FAST (r=0.197, p<0.001) and emotion-oriented coping (r=0.096, p˂0.05) providing evidence of its convergent validity. It also demonstrated inverse association with measures of resilience factors, specifically, SoC-13 (r=−0.597, p<0.001) and OSS-3 (r=−0.319, p<0.001). The two correlated factors model of CES-D demonstrated configural, metric, scalar, error variance and structural covariance invariances (p>0.05) for both men and women.

Conclusions

Unlike previous findings among Eritreans living in USA, second-order two factors structure of CES-D best fitted the data for Eritrean refugees living in Ethiopia; this implies that it is important to address culture for the assessment and intervention of depression.

Keywords: epidemiology, ces-d, eritrean refugees

Strengths and limitations of the study.

Adaptation of measures into the Tigrigna version following rigorous procedures of adaptation can be taken as the strength of the study, because it fills the pressing need for adaptation of depression measures in humanitarian settings of Africa.

Rating of all the items of CES-D and other measures in the present study by the experts for their content relevance is also the strength of the present study before using them in the main study.

Comparison of factor structure of CES-D observed between men and women shades light for our limited understandings regarding the contrast of symptom presentation for men and women in the African humanitarian context.

This study would have been profitable had we concurrently administered structured interviews like the Schedule for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, to estimate predictive validity.

Had the present study been based on multiple groups of samples, it would have increased the external validity of our findings. However, our sample was derived from a single population.

Study background

By the year 2020, depression is projected to be the second leading cause of disability adjusted life years and the fourth leading contributor to burden of disease.1 2 The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) is one of the most common instruments used to measure depression in non-clinical populations.3 Despite the fact that there are several studies to detect depression in the community using different measures, the latent factor structure for most measures of depression in many low-income countries, particularly in almost all African countries, is not well understood. Mere reliance on the total score of depression measures without understanding their latent factor structure is not sounding for reasons associated with validity. Therefore, there is a need for a cross-cultural study to ensure measurement equivalence (measurement invariance) of CES-D, before this measure is used in a given culture.4 Although most symptoms of depression are universal, problems related to validity and reliability of depression in African settings should be understood in light of ethnocentric conceptualisations.5 6 Symptoms of depression vary across cultures; this implies the possibility of incompatibility between existing measures of depression and local concepts of distress.5

CES-D is a scale for the measurement of clinical depression, originally designed for the general population.3 It was based on Beck’s four factors model of depression constituting four dimensions: positive affect, negative affect, somatic symptoms and retarded activity, and interpersonal difficulties.6 The four-factors structure of CES-D was previously fitted to data from the elderly populations of Spain, Mexico, the Netherlands and China, the African-Americans and Caucasians living in the USA, and Hispanic older adults.7–10

Studies suggest that factor structures of CES-D can vary across different cultures.9 11 12 Sheehan’s item allocation model of four latent factors was an alternative model that was tested as a variant to the four-factors structural model; Sheehan’s model demonstrated better fit to the data in many studies on populations from different cultures.13 In addition, evidence for two-factor and three-factor solutions of CES-D questioned the universality of the four-factor dimensions of CES-D.11 14 Therefore, its original four latent factors structure indicated in previous studies, including the study by the original scale developer Radloff (1977),15 is not consistently seen across cultures. For example, in a Turkish sample, the psychometric properties (ie, fit indices) of the four-factors structure of CES-D were found to be weak.16 Besides its application to the general population, CES-D was employed in different groups of vulnerable populations, including prisoners in Nepal,17 genocide survivors in Rwanda,18 Eritrean refugees in USA19 and Bosnian refugees.20 It was also used to measure depression among Korean immigrants in Canada.21 The instrument has been translated into many languages, employed in different ethnic groups, used for various groups of patients and wider age groups to study depression.16 Differences in the factor structures of CES-D have been reported in those studies.

Besides variation in cultures and types of population, difference in age is also accountable for the difference in the factor structures of the CES-D scale.22 There are contrasting findings which state that CES-D is having a stable factor structure and is reliable such that age, and other demographic variables and physical health factors do not significantly affect the factor structure as well as factor scores.10 For example, the four-factor structure demonstrated the best fitting model among black women in USA with or without history of cancer.23 However, a report from South Korea stated that the 14 items of CES-D fit into three-factor structures: anhedonia, negative affect and somatic symptoms.24 Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in women selected from a Middle Eastern country of Jordan resulted in a three-factor solution, namely, negative affect, somatic symptoms and positive affect.25

It was reported that the two-factor model, which combines all the negative items on one separate factor, and the remaining positive items on the second factor, demonstrated superior fit.14 For example, the two factors model, negative affect (16 items) and well-being (4 items) best fits data in studies of elderly Mexicans in USA,12 Puerto Ricans,26 and in studies from South Africa22 and Rwanda.18

These variations in the factor structure of the CES-D measure seen across cultures, as reported in the preceding paragraphs, necessitated the need to conduct a further empirical study on the validity of this measure in a sample of Eritrean refugees, because previous studies recommended the need to test the validity of measurement equivalence.4 9 11–13 Being informed by the findings of a validation study of the Tigrigna version of CES-D among Eritrean refugees in the USA19 as a starting point, the current study was designed to further understand the construct validity, factor structure and other psychometric properties of the Tigrigna version of the CES-D scale. For this purpose, an Eritrean refugee population living in a camp in Ethiopia was used for the study.

Methods

Study setting

This study was carried out in the Mai-Aini refugee camp, situated 1116 km north of Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. This is one of the largest refugee camps in northern Ethiopia, and was established in 2008 with support from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).27 As of 2013, this camp alone hosted about 17 825 Eritrean refugees.28 In the camp there are three churches for Orthodox, Protestant and Catholic religion followers and one mosque. The camp provides employment opportunities, health and education support to the local Ethiopians as well as the Eritreans.27 Two humanitarian institutions, namely Administration of Refugees and Returnees Affairs (ARRA) and Centre for Victims of Trauma (CVT) offer counselling and other forms of mental healthcare in the camp. In addition, Norwegian Refugee Council, International Rescue Committee and Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) are providing services such as education, psychosocial care and logistic support.29 Together with other partner organisations, a coordinated delivery of protection and assistance was jointly run by ARRA of the Ethiopian government and UNHCR.30

Study design

In this paper we report a portion of findings from cross-sectional survey data, which is part of the larger study on the psychotrauma of Eritrean refugees living in Ethiopia during the survey period.

Sample size and sampling procedures

This report was extracted from the larger study on psychotrauma of Eritrean refugees. Sample size was estimated based on the average prevalence estimate of PTSD of 30.73% among refugees and forced migrants in East African camps31–33 with 4% precision, 95% CI and 90% response. This resulted in a minimum sample size of 562. In order to determine a sampling frame, a census of refugees’ document by UNHCR from the office of ARRA was used as the starting point. According to the census, there was a total of 10 006 registered refugees living in Mai-Aini camp in January 2016, of which 4257 were women. Since we found that the census data were not complete, especially for new arrivals, we conducted census of households from December 2015 to January 2016. In this census, a total of 2055 households were registered out of which 100 houses were filtered out because they were units for unaccompanied minors (children below the age of 18 years living without their parents or guardians). The remaining 1955 units of households were taken as the sampling frame. From this, 562 households were selected using a simple random sampling method. One participant aged at least 18 years of age was selected from each of the selected households using a lottery method. Inclusion criteria included: those who had Eritrean nationality before migrating to Ethiopia, currently having a refugee status, and those who were not admitted in the health centre for treatment during the time of the survey. Twenty-two of the selected households were replaced from neighbouring households (ie, from those that preceded or followed the selected household numbers), because household members were not found on three visits by data collectors. Data collection took place from January to March 2016.

Adaptation procedures of measures

Except for CES-D, all the instruments were adapted following adaptation procedures of instruments for transcultural study.34 First, instruments were translated from the source language (English) into the target language (Tigrigna) by two bilingual experts, and then masked back translation was done by other two independent bilingual translators who had no knowledge about the original version. Translations and the back translations were given to experts for comments, and two consensus meetings were held by the experts in Addis Ababa and Mekelle Universities. After receiving feedback from the experts, two more consensus meetings were held to merge the translations.

Translations were then rated using a 4-point rating scale for relevance of their content by seven experts to obtain content validity index.35 36 Besides, cognitive interviews were done with six refugees from the target community and minor revisions were made based on their feedback. All the instruments were pilot tested before using them in the main study.

Patient and public involvement

The measures employed in the present study were validated by the situational analysis study carried out 1 year prior to the current study (Getnet B. Personal communication, 2015). Specifically, validation of measures involved refugee counsellors and a psychiatrist, who had years of work experience with Eritrean refugees. In doing this, the interest and priorities of refugees were accommodated in framing research questions as well as adapting measures to fit to the understanding of Eritrean refugees. There was direct involvement of some members of the refugee community (especially Eritreans who were members of the health staff) and district-level stakeholder organisations, such as CVT, International Organization for Migration (IOM), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and ARRA. These organisations supported the study by providing us with some material support, giving us the necessary information during the adaptation study. Although those refugees who scored higher on PTSD and depression were already encouraged to visit counsellors in CVT and ARRA through Eritrean healthcare staff, findings of the study will be communicated directly to the study participants as well as primary refugee stakeholder organisations, such as IOM, UNHCR, ARRA, CVT and JRS in the form of seminars and poster presentations.

Measures

Depression was measured using CES-D.37 The English version of CES-D is a brief 20-item scale with four alternative response options, ranging from ‘None of the time’ to be scored 0 to ‘Most of the time’ to be scored 3, and this instrument is designed to measure depressive symptomatology in the general population.37 Four items (ie, items 4, 8, 12 and 16) measuring feelings of positive affect were reverse coded.37 CES-D was translated and validated into Tigrigna for Tigrigna-speaking Eritrean refugees in the USA, and the author found an α value of 0.86 for internal consistency and 0.91 for test retest reliability.19

Traumatic events for refugees were measured using the premigration and postmigration living difficulties checklist.38 This brief 14-item checklist has a 5-point response format (ie, strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree and strongly agree to be scored from 0 to 5).38 It was developed and employed to measure traumatic events of Zimbabwean refugees in South Africa during premigration and postmigration periods.38 39 In order to differentiate between those who had encountered trauma from those who had not, the authors recoded original scores 1–3 to 0 and scores 4 and 5 to 1.39

PTSD was measured using the Primary Care PTSD (PC-PTSD) screener.40 This is a four-item PTSD screening instrument, having two options ‘Yes’ or ‘No’.40 The test-retest reliability for this measure was found to be 0.8341 with sensitivity and specificity of 0.78 and 0.87, respectively.40 This scale was used to detect PTSD in different population groups such as US soldier returnees from combat and refugees in USA from different countries.41–44

Coping strategies were measured using a Coping Style Scale,45 consisting of a list of 10 items. The items require participants to respond as ‘this is not like me’ or ‘this is like me’.45 This instrument was cross-culturally validated by the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization, and later used to study displaced Ethiopians from Eritrea.45 This scale roughly captured three coping strategies, including: task-oriented, avoidance-oriented and emotion-oriented coping strategies.45

Resilience was measured using the Sense of Coherence Scale (SoC-13).46 This is a 13-item semantic differential scale adapted to the Eritrean culture in the form of a 5-point Likert Scale from the original 7-point scale to reduce complexity of understanding.47 The instrument was reported to have proved the measure of resilience in an Eritrean population.47

Social support was measured using Oslo Social Support Scale (OSS-3).48 This is a scale consisting of three items in which sum scores range from 3 to 14.49 In a validation study of OSS-3 in Nigeria, the internal consistency value of Cronbach’s α was found to be 0.5.49

Alcohol use was measured using the fast alcohol screening test (FAST).50 FAST is a four-item tool meant to measure alcohol use, which was extracted from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.50 51 Each item is scored from 0 to 4, whose total score was considered as either FAST-positive or FAST-negative. A mean score of 3 or more would be considered FAST-positive.50 Test-retest reliability of the total score for inter-rater agreement was 0.83, demonstrating excellent agreement.51 It was employed to study alcohol use in the East-African setting, including Ethiopia.52 FAST demonstrated an overall sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 93%,50 and it is assumed to be used in busy medical settings.51

Statistical analysis

Before running CFA, CES-D items were evaluated on the basis of the minimum requirement criteria for assumptions of factor analysis. CFA was employed to generate ‘etic’ knowledge using IBM SPSS Amos, V.21. Single-group confirmatory factor analysis (SGCFA) was employed to test theoretically relevant prespecified factor structures for a single group of the total sample (n=562). Multigroup confirmatory factor analysis (MGCFA) was used to test for measurement invariance between men and women on the four dimensions. Specifically, metric invariance (invariance of factor loadings) was performed on confirmation of configural invariance between two groups;53 scalar invariance (intercept invariance), which indicates equivalence for latent scores and observed scores; error variance invariance, which indicates presence of measurement error of each in the two groups; factor covariance invariance, indicating the stability in the relationship of factors between groups.54

Cut-off values of fit indices for accepting a model was determined based on standard minimum cut-off criteria: values of χ2 to df (x2/df) should be ≤3; values should be ≥0.95 for Comparative Fit Index (CFI); ≥0.95 for Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI); ≤0.06–0.08 for root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and ≤0.08 for standardised root mean residual (SRMR).55

Convergent validity was assessed by examining the extent to which the indicators loaded onto the expected factors and divergent or discriminate validity was judged using the correlation between the latent factors.56 Discriminant validity is considered adequate when this correlation is ≤0.80 or 0.85.56 Content validity was analysed by Content Validity Index (CVI), which estimates for Item-level Content Validity Index (I-CVI) and Scale-level Content Validity Index (S-CVI) for content relevance.35 57 58 The proportion of agreement on the relevance of each item (I-CVI) should be at least 0.78.35 36

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

Of the 562 participants, 304 (54.1%) were women. The mean age of the participants was 29.63 years, which ranged from 18 years to 74 years (SD=10.18). The vast majority was literate; the average duration of stay in the refugee camp was 3.71 years, and a high proportion of the participants (92%) belonged to the Tigriya ethnic group. Only 8% of participants constituted other ethnic groups such as Saho, Bilen, Tigre and Jabelty. In terms of religion, 84% are followers of Coptic Orthodox Christianity. The study participants had diverse occupational profiles before coming to Ethiopia and most of them (71%) constituted students, military personnel and farmers (see table 1)

Table 1.

The demographic characteristics of participants

| Characteristics | Number (%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 258 (45.9) |

| Female | 304 (54.1) |

| Age, years | |

| Mean(SD) | 29.6 (10.2) |

| 18–24 | 205 (36.5) |

| 25–34 | 219 (39.0) |

| 35–44 | 89 (15.8) |

| 45–54 | 29 (5.2) |

| 55–64 | 15 (2.5) |

| 65–75 | 5 (0.9) |

| Educational background | |

| Non-literate | 67 (11.9) |

| Elementary school | 232 (41.3) |

| Secondary school | 238 (42.3) |

| College graduate or above | 25 (4.5) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 189 (33.6) |

| Married | 327 (58.2) |

| Divorced | 29 (5.2) |

| Widowed | 17 (3.0) |

| Religion | |

| Orthodox | 477 (84.9) |

| Protestant | 17 (3.0) |

| Catholic | 23 (4.1) |

| Muslim | 44 (7.8) |

| Jehovah witness | 1 (0.2) |

| Past occupation in Eritrea | |

| Student | 201 (35.8) |

| Military | 111 (19.8) |

| Farmer | 89 (15.8) |

| Home maid | 66 (11.7) |

| Educator | 23 (4.1) |

| Daily labourers | 15 (2.7) |

| Others | 57 (10.1) |

Mean score and internal consistency of CES-D

The mean value of CES-D for the total sample (n=562) is 26.87 with SD of 12.86. Specifically, women have a mean CES-D score of 26.83 with SD 13.07, whereas men have a mean CES-D score of 26.91 with SD 13.76. The value of Cronbach’s α as a measure of internal consistency for items of CES-D was 0.917 in the pilot study (n=50) and 0.913 in the main study (n=562). Gutman’s split half reliability of this instrument was 0.905 (n=562). The item-total correlation ranged from 0.22 to 0.85 in the pilot study (n=50) and from 0.21 to 0.74 in the main study (n=562). Four items, which measure absence of positive well-being (item 4, item 8, item 12 and item 16), have consistently demonstrated lower item-total correlation both in the pilot study and the main study. The internal consistency is substantially reduced to ≤0.75 if any of the item is deleted compared with an α value of 0.91 for the total items (table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of item-total correlation, internal consistency and content validity of CES-D

| CES-D items | Item-total correlation in the | Cronbach’s | I-CVI |

| main study (n=562) | α if an | ||

| item is deleted | (n=562) | ||

| (n=562) | |||

| 1. I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me. | 0.67 | 0.74 | 1 |

| 2. I did not feel like eating; my appetite was poor. | 0.623 | 0.742 | 1 |

| 3. I felt that I could not shake off the blues even | 0.687 | 0.738 | 0.86 |

| with help from my family. | |||

| 4. I felt that I was just as good as other people. | 0.284 | 0.75 | 1 |

| 5. I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing. | 0.735 | 0.739 | 1 |

| 6. I felt depressed. | 0.721 | 0.738 | 0.86 |

| 7. I felt that everything I did was an effort. | 0.7 | 0.738 | 0.86 |

| 8. I felt hopeful about the future. | 0.21 | 0.752 | 1 |

| 9. I thought my life had been a failure. | 0.601 | 0.741 | 1 |

| 10. I felt fearful. | 0.712 | 0.739 | 1 |

| 11. My sleep was restless. | 0.732 | 0.739 | 0.86 |

| 12. I was happy. | 0.425 | 0.747 | 1 |

| 13. I talked less than usual. | 0.698 | 0.74 | 1 |

| 14. I felt lonely. | 0.742 | 0.737 | 1 |

| 15. People were unfriendly. | 0.525 | 0.744 | 0.86 |

| 16. I enjoyed life. | 0.386 | 0.747 | 1 |

| 17. I had crying spells. | 0.738 | 0.738 | 0.71 |

| 18. I felt sad. | 0.706 | 0.739 | 1 |

| 19. I felt that people disliked me. | 0.662 | 0.74 | 1 |

| 20. I could not ‘get going’. | 0.707 | 0.739 | 1 |

*Value of Cronbach’s α for the total scale=0.91.

Avarage scale Level Content Validity index (S-CVI/Ave)=0.92.

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; I-CVI, Item-level Content Validity Index,

Content validity

The Item-level Content Validity Index (I-CVI) values for the 20 items ranged from 0.71 to 1, and Average Scale-level Content Validity Index (S-CVI/Ave) for the total scale was 0.92 (see table 2).

Single-group confirmatory factor analysis

The preliminary test for assumption of factor analysis for CES-D items indicates that the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.939. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (x 2=5258.70; df=190, p<0.001). The minimum sample size needed (ie, n>200) for factor analysis was also met (n=562).

In the present study, CFA results for the total sample (n=562) indicate that the four-factor solution of the CES-D model, which was identified by the original scale developer, Radloff (1977), hasn’t achieved the minimum adequate fit because of negative definitiveness across the variance matrix within the factors. Further investigations of theoretically plausible alternative models of CES-D with respect to their factor structures were made and the findings are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of fit indices to the computing factor structures of CES-D to the Eritrean refugee sample

| Proposed model of CES-D | Sample | χ2 (df) | CFI | χ2/df | GFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA | P values |

| 1. Four correlated factors model (Sheehan’s item allocation) | |||||||||

| Correlated error terms | Total sample (n=562) | 588.62 (158) | 0.916 | 3.725 | 0.903 | 0.899 | 0.0475 | 0.07 | p<0.001 |

| Uncorrelated error terms | Total sample (n=562) | 704.346 (164) | 0.895 | 4.295 | 0.882 | 0.878 | 0.0504 | 0.077 | p<0.001 |

| 2. First-order four factors with second order model (Sheehan’s item allocation) | |||||||||

| Correlated error terms | Total sample (n=562) | 619.63 (161) | 0.911 | 3.819 | 0.897 | 0.895 | 0.048 | 0.071 | p<0.001 |

| Uncorrelated error terms | Total sample (n=562) | 709.251 (166) | 0.894 | 4.273 | 0.881 | 0.879 | 0.0508 | 0.076 | P<0.001 |

| 3. Two correlated factors structure | |||||||||

| Correlated error terms | Total sample (n=562) | 302.801 (150) | 0.97 | 2.019 | 0.95 | 0.962 | 0.0391 | 0.043 | p<0.001 |

| 4. First-order twofactors, second-order common factor | |||||||||

| Correlated error terms | Total sample (n=562) | 271.65 (144) | 0.975 | 1.886 | 0.955 | 0.967 | 0.0378 | 0.04 | p<0.001 |

| Correlated error terms | Female (n=304) | 239.495 | 0.965 | 1.5886 | 0.929 | 0.956 | 0.0484 | 0.044 | p<0.001 |

| Correlated error terms | Male (n=258) | 284.592 | 0.952 | 1.801 | 0.901 | 0.943 | 0.0479 | 0.056 | p<0.001 |

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CFI, Comparative Fit index; GFI, Goodness of Fit Index; RMSEA, root mean error of approximation; SRMR, standardised root mean residual; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index; χ2/df=χ2 to degree of freedom.

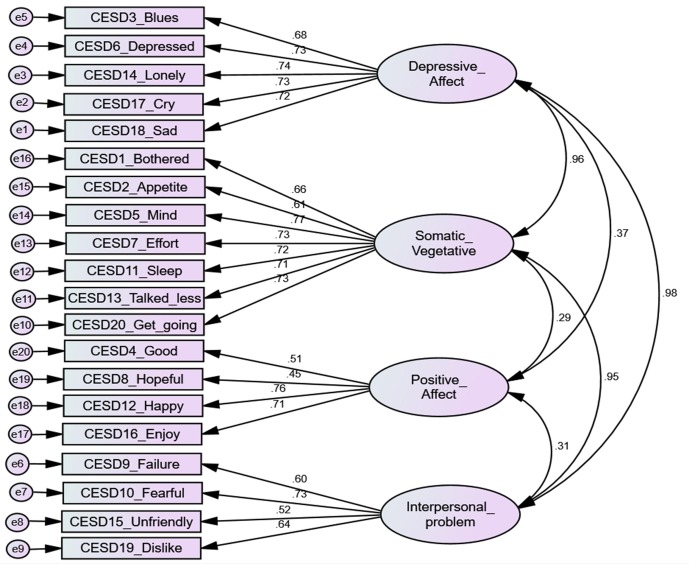

Examination of the four correlated factors structure of CES-D, Sheehan’s item allocation; (figure 1) demonstrated poor fit to the present data with CFI <0.90 and RMSEA>0.05.

Figure 1.

Four correlated factors model of the CES-D model (Sheehan’s item allocation, uncorrelated error terms). Rectangles represent indicator items; ovals represent latent factors; single headed arrows along with standardised weights represent item loadings; double-headed arrows represent covariances between factors; circles represent error terms for each item (e). Model fit: χ2=704.346; df=164; X2/df=4.295; CFI=0.895; TLI=0.878; RMSEA=0.077; SRMR=0.0504. CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; SRMR, standardised root mean square residual; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index.

Further modifications on this model based on Modification Index (MI), after allowing error terms of some items to correlate, this model showed a reasonable fit of the current data: χ2=588.62; df=158; CFI=0.916; RMSEA=0.070; SRMR=0.0475 (table 3). An additional CFA test for the second-order four factors model of CES-D (Sheehan’s item allocation) (figure 2) yielded more or less similar results with fit indices for the four correlated factors structure of CES-D with very slight differences (table 3: models 1 and 2).

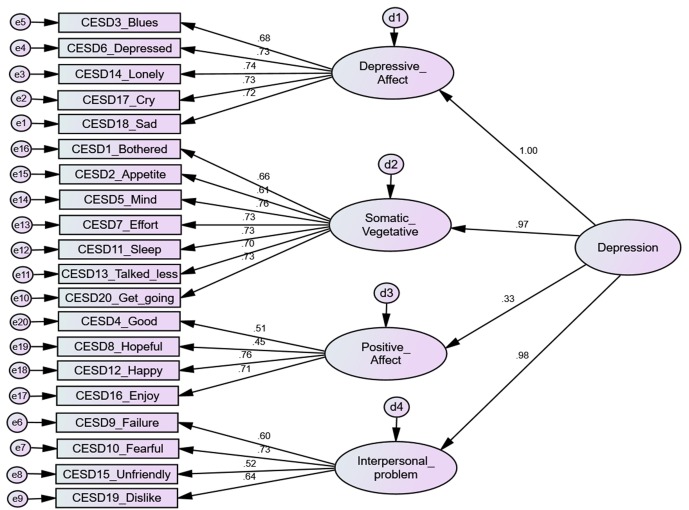

Figure 2.

Four factors with second-order single common factor model of CES-D (Sheehan’s item allocation, uncorrelated error terms). Rectangles represent indicator items; ovals represent latent factors; single-headed arrows along with standardised weights represent factor and item loadings; circles represent error terms for each item (e) and disturbance terms of each latent factor (d). Model fit: χ2=709.251; df=166; X2/df=4.273; CFI=0.894; TLI=0.879; RMSEA=0.076; SRMR=0.0508. CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; SRMR, standardised root mean residual; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index.

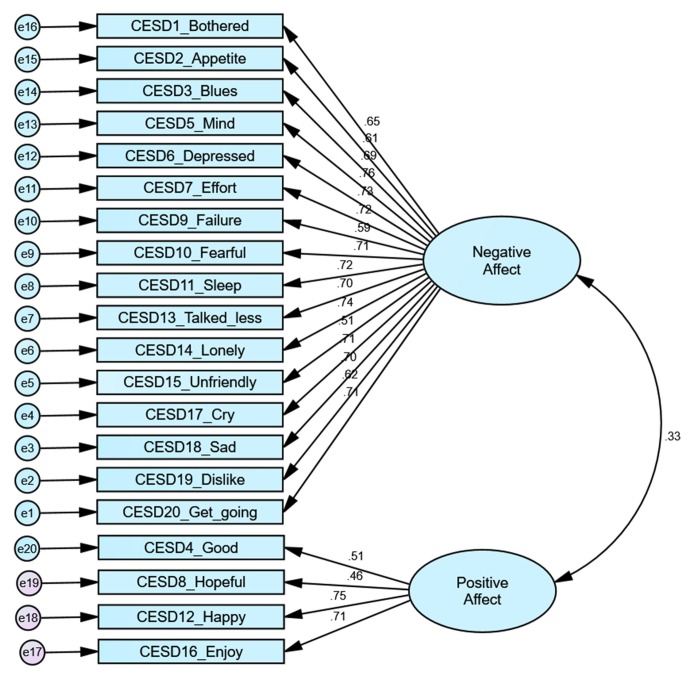

CFA test for the two models, specifically for the two correlated factors model of CES-D (figure 3) and the first-order two factors with second-order common factor structure of CES-D (figure 4) yielded a similar estimate of item loadings and fit indices, which is below the acceptance level (CFI˂0.95; RMSEA˃0.06). The second-order common factor with first-order two factors structure was tested in order to further understand if the current data supported evidence of a single common latent factor ‘depression’, thinking that it can explain the two related factors.

Figure 3.

Two correlated factors structure of CES-D, uncorrelated error terms. Rectangles represent indicator items; ovals represent latent factors; single-headed arrows along with standardised weights represent item loadings; circles represent error terms for each item (e), and disturbance terms of each latent factor (d). Model fit:χ2=725.929; df=169; X2/df=4.295; CFI=0.892; TLI=0.878; RMSEA=0.077; SRMR=0.0512. CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; SRMR, standardised root mean square residual; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index.

Figure 4.

The first-order two factors with second-order common factor structure of CES-D, uncorrelated error terms. Rectangles represent indicator items; ovals represent latent factors; single-headed arrows along with standardised weights represent factor loadings; circles represent error terms for each item (e), and disturbance terms of each latent factor (d). Model fit: χ2=725.929; df=169; X2/df=4.295; CFI=0.892; TLI=0.878; RMSEA=0.077; SRMR=0.0512. CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximatio; SRMR, standardised root mean square residual; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index.

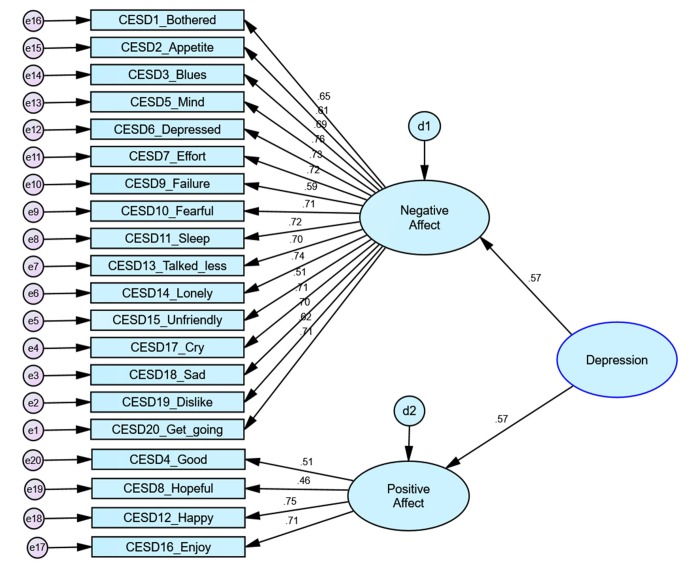

Further modifications of the model were made after allowing error terms of some items to correlate based on MI, and constraining one additional second-order path into 1 (see online supplementary figure 1). This resulted in excellent fit to the current data in the sample of Eritrean refugees better than all models tested: x2=271.65; df=144; CFI=0.975; SRMR=0.0378; RMSEA=0.040 (90% CI 0.032 to 0.047) with substantial improvement in the fit indices compared to CES-D model indicated in figure 4.

bmjopen-2018-026129supp001.docx (199.2KB, docx)

The first factor, negative affect (16 items) has excellent internal consistency (value of Cronbach’s α=0.932) whereas the second factor, positive affect (4 items), has good level of internal consistency (value of Cronbach’s α=0.703).

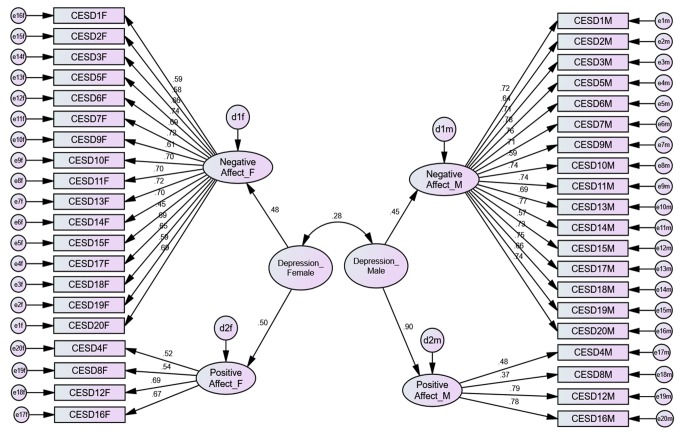

In addition, the first-order two latent factors were adequately loaded onto a single dimension, and all the 20 indicator items have demonstrated sufficient loading onto their respective latent factors. In the hierarchical model of CES-D with the first-order two factors model (correlated error terms), 57% of variance in the single second-order factor ‘depression’ is explained by first-order latent factor, positive affect (4 items), while 61% of variance of this second-order common construct ‘depression’ is explained by another first-order latent factor, negative affect (16 items) (see online supplementary figure 1). In the first-order two factors with second-order common factor structure of CES-D, all the 16 items sufficiently loaded onto the first factor (negative affect) ranging from 0.51 to 0.76, while 4 items sufficiently loaded onto the second factor (positive affect) ranging from 0.46 to 0.75 (figure 4) for the total sample. A similar trend of item loadings with smaller variation is observed between female (n=304) and male (n=258) subsamples (see figure 5). In the second-order single common factor model with first-order four factors model of CES-D (Sheehan’s item allocation), all the 20 items of CES-D sufficiently loaded onto the expected four separate latent factors ranging from 0.45 to 0.76 (see figure 2).

Figure 5.

Co-variance between second-order depression latent factors for male (n=258) and female (n=304) subsamples of Eritrean refugees. Rectangles represent indicator items; ovals represent latent factors; single-headed arrows along with standardised weights represent factor and item loadings; circles represent error terms for each item (e), and disturbance terms of each latent factor (d). Model fit: χ2 =71478.854; df=737; X 2 /df=2.007; CFI=0.860; TLI=0.844; RMSEA=0.042 (90% CI 0.039 to 0.045). CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index.

Multigroup confirmatory factor analysis

MGCFA was performed for men and women on the two correlated factors structure of CES-D (uncorrelated error terms), which resulted in a close fit to the data (χ2 = 938, df=338, p<0.001; CFI=0.884, TLI=0.870, RMSEA=0.056 [90% CI 0.052 to 0.061], SRMR=0.0538). Separate analysis for each group indicates that the fit indices for men (n=258) were χ2=432, df=169, p<0.001; CFI=0.901, TLI=0.888, SRMR=0.0538; RMSEA=0.078 (90% CI 0.069 to 0.087), and the fit indices for women (n=304) were χ2=505.571, df=169; CFI=0.867, TLI=0.851, SRMR=0.0602, RMSEA=0.081 (90% CI 0.073 to 0.089).

Thus, configural invariance was supported since this model demonstrated close fit, but not within acceptable range, to the current data for both men and women. Further analysis for measurement weight, measurement intercept, structural covariance and measurement residuals indicate that χ2 differences were not statistically significant (p>0.05) (see table 4). Overall, the two correlated factors model is invariant between men and women. Thus, the findings demonstrate configural invariance, metric invariance, scalar invariance and structural covariance invariance.

Table 4.

Comparison of the two correlated factors model of CES-D (with uncorrelated error terms) for male and female subsamples of Eritrean refugees

| Model | df | χ2 | P values | NFI | IFI | RFI | TLI |

| δ-1 | δ-2 | ρ-1 | ρ-2 | ||||

| Measurement weights | 18 | 13.965 | 0.731 | 0.003 | 0.003 | −0.007 | −0.007 |

| Measurement intercepts | 38 | 49.601 | 0.099 | 0.009 | 0.009 | −0.01 | −0.011 |

| Structural covariance | 41 | 55.456 | 0.065 | 0.01 | 0.011 | −0.01 | −0.011 |

| Measurement residuals | 61 | 76.714 | 0.085 | 0.014 | 0.015 | −0.016 | −0.017 |

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; IFI, Incremental Fit Index; NFI, Normed Fit Index; df, degrees of freedom; RFI, Relative Fit Index; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index.

In addition, an estimate for the standardised covariance estimate for the two second-order depression latent factors calculated for male and female samples (figure 5), after constraining second order paths to one yielded modest relationship demonstrated significant relationship (standardised covariance=0.28, p<0.05).

Discriminant validity

Evidence from the present study with respect to discriminant validity among four latent correlated factors (Sheehan’s item allocation) (figure 1) demonstrated that there is strong covariance between the three factors of depressive affect, somatic vegetative and interpersonal problems (standardised covariance ≥0.95, p<0.001), which is greater than the maximum cut-off value for a factor to be significant for discriminant validity. There is a satisfactory discriminant validity below the threshold cut-off point (standardised covariance <0.80) demonstrated between positive affect with each of the three latent factor structures (ie, depressive affect, somatic vegetative and interpersonal problems) with standardised covariance of 0.37, 0.29 and 0.31, respectively. For the women subsample (n=304), the covariance between positive affect with each of the subscales (ie, depressive affect, somatic vegetative and interpersonal problems) had a standardised covariance of 0.34, 0.18 and 0.20, respectively. For the male subsample (n=258) the standardised covariance between positive affect with depressive affect, somatic vegetative and interpersonal problems is 0.39, 0.40, 0.40 respectively. The covariance demonstrated in women and men is consistently lower (standardised covariance ≤0.40) between positive affect and the other three latent factors. However, the covariance seen in the three factors (ie, depressive affect, somatic vegitative and interpersonal problems) is very high in both women and men with (standardised covariance estimate ≥0.91 for men and ≥0.96 for women) (see table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison in the covariance between latent factors of CES-D for male and female subsamples of Eritrean refugees

| Model | Sample | Fit statistics | Latent factors | Positive affect |

Depressive affect |

Somatic vegetative |

Interpersonal problem |

| Four factors model of CES-D | Total (n=562) | CFI=0.895; RMSEA=0.077 (90% CI 0.71 to 0.83) |

Positive affect | 1 | |||

| Depressive affect | 0.37 | 1 | |||||

| Somatic vegetative | 0.29 | 0.96 | 1 | ||||

| Interpersonal problem | 0.31 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1 | |||

| Male (258) | CFI=0.906; RMSEA=0.077 (90% CI 0.68 to 0.86) |

Positive affect | 1 | ||||

| Depressive affect | 0.39 | 1 | |||||

| Somatic vegetative | 0.4 | 0.96 | 1 | ||||

| Interpersonal problems | 0.4 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 1 | |||

| Female (304) | CFI=0.872; RMSEA=0.081 (90% CI 0.73 to 0.89) |

Positive affect | 1 | ||||

| Depressive affect | 0.34 | 1 | |||||

| Somatic vegitative | 0.18 | 0.96 | 1 | ||||

| Interpersonal problem | 0.2 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 1 | |||

| Negative affect | |||||||

| Two factors model CES-D | Total (n=562) | CFI=0.892; RMSEA=0.077 (90% CI 0.71 to 0.82) |

Positive affect | 0.33 | |||

| Male (258) | CFI=0.901; RMSEA=0.078 (90% CI 0.69 to 0.87) |

Positive affect | 0.4 | ||||

| Female (304) | CFI=0.867; RMSEA=0.081 (90% CI 0.73 to 0.89) |

Positive affect | 0.24 |

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

The bivariate Pearson’s correlation analysis indicated that CES-D was negatively and significantly associated with SoC-13 (r=−0.597, p<0.001) and OSS-3 (r=−0.319, p<0.001). The higher discriminant validity with estimates of covariance ≤0.40 in the four factors model (Sheehan’s item allocation) is consistently demonstrated in female (n=304) and male (n=258) samples. In the two factors model, there is 33% covariance between latent factors of ‘positive affect’ and ‘negative affect’. Subsample CFA analysis by gender for this two factors model of CES-D demonstrated that although there is no statistically significant variation in factor covariance (invariance of factor co-variance) and item loading (metric invariance)(table 4), there is slight differences in factor co-variances (table 5)and item loadings (figure 5) of this model between women and men. The covariance between the two factors for women, men and the total sample is 24%, 40% and 33%, respectively. MGCFA showed that χ2 differences with respect to these factor covariance and item loadings are not statistically significant (p˃0.05), indicating factor covariance invariance and metric invariance of this model for both men and women.

Convergent validity

Analysis of the bivariate Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) of CES-D with measures of other constructs has showed a significantly positive relationship with the premigration living difficulties checklist (r=0.545, p<0.001), postmigration living difficulties checklist (r=0.47, p<0.001); PC-PTSD (r=0.538, p<0.001); FAST (r=0.197, p<0.001) and emotion-oriented coping (r=0.096, p˂0.05).

Comparison of the factor structure of the present study with samples from Western culture

The contrast in the factor structure of the present findings with findings of previous studies done in Europe, USA and Canada is summarised in table 6.

Table 6.

Comparison of the factor structure of the Tigrigna version of CES-D with previous studies done in samples of USA, Canada and Europe

| Author | Study context | Sample | Best fitting factor structure of CES-D |

| Present study | Eritreans in Ethiopia | Eritrean refugees living in the Mai-Aini refugee camp, Ethiopia (n=562) | First- order two factors model, with second-order common factor (correlated error terms) CFI=0.975; RMSEA=0.040 (90% CI 0.032 to 0.047) |

| Wu Q et al 62 | Belgium | Dutch-speaking Belgians (n=837) | First- order four factors model, with second-order common factor (correlated error terms) CFI=0.982, RMSEA=0.036 (90% CI 0.031 to 0.041) |

| McCauley SR et al 60 | USA |

|

Four factors model of CES-D has a reasonable fit to the data CFI=0.99; RMSEA=0.023 (90% CI 0.00 to 0.035) |

| Carleton et al 64 | Canada and USA | Multiple samples drawn from Canada and USA:

|

Three factor solutions CES-D best fitted to:

|

| Morin AJS et al 63 | France | French sample (n=461) Clinical sample (n=163) Non-clinical sample (n=298) |

Four first-order factors and second-order factor (CFI=0.993; RMSEA=0.04 (90% CI 0.036 to 0.051) |

| Asari et al 59 | USA |

|

|

| Tatar and Saltukoglu61 | Turkey | 1143 sample aged 17 to 85 selected from from student and adult population | Four factor structure of CES-D has demonstrated better fit to the data GFI=0.84; RMSEA=0.10 |

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; GFI, Goodness of Fit Index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

Discussion

In the present study, which was mainly aimed at identifying construct validity and factor structure and structural invariance of CES-D in Eritrean refugees who were living in Ethiopia during the study period, the two factors with higher-order single factor model of CES-D (with correlated error terms) showed best fit to the present data, with all the 20 items sufficiently loading onto their respective latent factors.

The present finding regarding the fit of our data with the two factors structure seems to be in line with previous findings from South Africa,22 and from the genocide survivors sample in Rwanda.18 The present finding is also in agreement with studies from non-institutionalised civilian Puerto Ricans living on the islands and in elderly Mexicans in the USA.12 26 It can be inferred that depression, as measured by CES-D, is best presented in terms of two factors instead of the four factors structure proposed by the original scale developer, Radloff (1977),37 as well as findings of a previous study in Eritrean refugees in USA.19 Our study came up with a contrasting finding regarding factor structure of depression for Eritrean refugees living in different geographical and social environments, which would make it difficult to explain. The question remains whether the difference in current living circumstances of refugees can explain the difference in symptom expression of depression in people who originated from the same geographical and social environments.

Unlike the evidence from Puerto Ricans, which indicates that the two factors structure of CES-D was non-invariant between men and women,26 the current finding showed measurement invariance of the two factors between men and women. The overall two correlated factors model of CES-D (uncorrelated error terms) is invariant between male and female Eritrean refugees in this study since χ2 differences for the measurement weight, measurement intercept, structural covariance and measurement residuals were not statistically significant (p>0.05). This implies the stability of a two factors structure of depression in men and women as measured by CES-D where gender cannot confound the validity of this model in the Eritrean refugee sample.

The value of α=0.91 obtained for the whole scale as a measure of internal consistency in the present study is comparable with previous findings in African settings, such as 0.86 in Rwanda and 0.90 in South Africa as was indicated in a systematic review report.53 The implications of a substantial reduction in internal consistency to ≤0.75 if any of the items is deleted compared with an α value of 0.91 for the total items (table 2) is that all items of CES-D proposed by Radloff (1977) are valid in the Eritrean culture to measure the depression construct. The value of α=0.91 obtained for the whole scale as a measure of internal consistency in the present study is comparable with previous findings in African settings, such as 0.86 in Rwanda, and 0.90 in South Africa.35 Item 8 (I felt hopeful about the future) and item 4 (I felt that I was just as good as other people) showed the lower item-total correlation both in the pilot and in the main studies. This weaker correlation of item 4 in the present study supports a report from cross-cultural studies in Latin America, Spain and Mexico.7 The association between CES-D and other measures of adverse conditions in the current study including PC-PTSD, the premigration and postmigration living difficulties checklist, and FAST indicate a significant positive relationship. This implies that there is acceptable convergent validity between CES-D and other scales, which measure adversities to psychological well-being. Of all measures used in the current study, CES-D is highly correlated with PC-PTSD, although the direction of relationship cannot be inferred from the current cross-sectional study design.57 On the other hand, an acceptable and expected significant inverse association was demonstrated between SoC-13 and CES-D on the same sample of Eritrean refugees, as reported in a recent publication.58 This means CES-D as measure of depression in the Eritrean community did not positively relate to measures of resilience and well-being (sense of coherence), implying its acceptable divergent validity.

The test for discriminant validity in the present study between four latent correlated factors, in light of the proposed Sheehan’s item allocation,13 demonstrated that there is strong covariance among the three factors of depressive affect, somatic vegetative and interpersonal problems (r>0.95, p<0.001). This correlation is >0.85 which is the maximum cut-off value for a factor to be significant for discriminant validity.56 This may imply that the factors may stand to measure a similar or the same construct. However, there is a satisfactory discriminant validity below the cut-off point (r<0.80) shown between positive affect and each of the three latent factors (ie, depressive affect, somatic vegetative and interpersonal problems) with standardised covariance of 0.37, 0.29 and 0.31, respectively (see figure 1). This indicates that the coefficients for the three former highly correlated factors indicate the maximum cut-off point in factor covariance, indicating absence of discriminant validity between the three related subscales. This may imply that the three correlated subscale factors measure similar things or same factors, while the later absence of positive affect may represent the second distinct factor for depression construct. The present findings support those previous research findings, which reported that the two factors structure of CES-D is more reasonable in the non-Western sample studied,12 18 22 26 which is different from an acceptable four factors structure of the scale reported in samples reviewed in USA, Canada and Europe.59–64 Our evidence strengthens the view that cultural variation in symptom presentation of depression is crucial,65 arguing that depression is not a mere product of the absence of balance in brain chemicals, but depression may be a socially constructed, whereby specific symptoms and pattern of symptomatology are differently emphasised across cultures. Our findings are in line with a contemporary theory of depression called social constructivist paradigm, which contends that depression can result from an individual’s living environment and some other factors different from neural functioning.66 In this paradigm, it is argued that depression should not be regarded as an universal emotion, rather it is a condition lived out in a given sociocultural condition.66 A pillar of this paradigm known as symbolic interactionism contends that people construct the meaning of their depression in their daily life.66 The dimensions of CES-D seen in terms of three/four factors structures in samples drawn from samples of Europe, USA and Canada59–64 contrasts the two factors structure of this scale in samples of non- Western cultural settings.12 18 22 26 In this regard, our findings lend supportive evidence to the previous findings seen in samples of the latter group of studies done in non-Western cultural contexts that strengthens the social constructivism paradigm of depression.66

Clinical implications of findings for refugees’ healthcare

The findings of this study imply that there is variation in symptom presentation of depression for people with the same ethnic background, but who are living in different sociocultural and geographical settings. Therefore, in the present sample, intercorrelated separate symptoms of depression, depressive affect, somatic complaints and social problem are loading onto a single common factor, implying that these three inter-related symptoms are being manifested as one mix of symptoms. Absence of positive affect was the second presenting symptom for depression. The diminished factor loadings from the first three separate latent factors (which is the dominant factor structure of CES-D in many Western settings) to one merged latent factor from among the two factors in the present sample may be helpful for healthcare providers and researchers to understand and explain the reason why most Eritreans may express their depressive feelings associated with social relationship and depressed mood through somatic symptoms. Counselors, psychiatrists and other mental healthcare professionals may find such an evidence helpful to easily understand the idiomatic exprressions for depression common to Eritreans so that they can properly capture culture specific symptoms of depression useful for their clinical practice.

Conclusions

Unlike Eritrean refugees in USA whose data fitted well with four correlated first order factors structure of CES-D, second-order one factor with two first order factors of CES-D fitted well to the current data generated from Eritrean refugees living in Ethiopia. Findings in the present study provided an additional evidence on the utility of CES-D as a psychometrically sound instrument to measure depression among Eritreans in humanitarian settings. Yet, caution should be taken while interpreting the dimensionality of CES-D in light of the Western Diagnostic Statistical Manual framework in the assessment of symptoms as well as planning an intervention for the Eritrean refugee community living in Ethiopia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank those health staff members of ARRA health center and CVT in Mai Aini refugee camp for their unreserved support in coordinating and extending material assistance in the entire stay of data collection, without which realization of this study would have been impossible. The authors also thank the study participants who were willing share their psychological and social experiences before and during their travel to Ethiopia, and while living in the camp.

Footnotes

Contributors: BG, the principal investigator, led in generating the research ideas, design and methods of the study, and wrote the research protocol. He also led the validation of measures, data collection, analysis, interpretation and wrote the findings. AA has made contribution in revising the research protocol, revised the draft manuscript and provided constructive comments during the process of writing this paper. He has also reviewed the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was financially supported by Addis Ababa University and University of Gondar, Ethiopia.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Institutional Ethical Review Board (IRB) of College of Health Sciences in Addis Ababa University (AAU) under approval letter (protocol number: 052/14/Psy). Participants were provided with an information sheet about the study regarding its objective, relevance, beneficence, risk, participant’s rights and others. Then a written consent from each participant was obtained before engaging them to participate. Ethical issues as outlined by declaration of Helsinki for human participants in medical research were adhered.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All necessary data to understand in the manuscript (MS) are included in tables or text within the MS. The row data in SPSS format can be accessed from the department of psychiatry upon reasonable request by the legal institution in accordance with data sharing policy of Institutional Review Board (IRB) of College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University (AAU).

References

- 1. Reddy MS. Depression: the disorder and the burden. Indian J Psychol Med 2010;32:1–2. 10.4103/0253-7176.70510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health 2013;34:119–38. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boisvert JA, McCreary DR, Wright KD, et al. Factorial validity of the center for epidemiologic studies-depression (CES-D) scale in military peacekeepers. Depress Anxiety 2003;17:19–25. 10.1002/da.10080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. L. Milfont T, Fischer R. Testing measurement invariance across groups: applications in cross-cultural research. Int J Psychol Res 2010;3:111–21. 10.21500/20112084.857 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mutumba M, Tomlinson M, Tsai AC. Psychometric properties of instruments for assessing depression among African youth: A systematic review. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health 2014;26:139–56. 10.2989/17280583.2014.907169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Summerfield D. Major depression' in Ethiopia: validity is the problem. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:362 10.1192/bjp.190.4.362a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Losada A, de los Angeles Villareal M, Nuevo R, et al. Cross-cultural confirmatory factor analysis of the CES-D in Spanish and Mexican dementia caregivers. Span J Psychol 2012;15:783–92. 10.5209/rev_SJOP.2012.v15.n2.38890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang B, Fokkema M, Cuijpers P, et al. Measurement invariance of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D) among chinese and dutch elderly. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:1–10. 10.1186/1471-2288-11-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nguyen HT, Kitner-Triolo M, Evans MK, et al. Factorial invariance of the CES-D in low socioeconomic status African Americans compared with a nationally representative sample. Psychiatry Res 2004;126:177–87. 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ros L, Latorre JM, Aguilar MJ, et al. Factor structure and psychometric properties of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) in older populations with and without cognitive impairment. Int J Aging Hum Dev 2011;72:83–110. 10.2190/AG.72.2.a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gay CL, Kottorp A, Lerdal A, et al. Psychometric Limitations of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale for Assessing Depressive Symptoms among Adults with HIV/AIDS: A Rasch Analysis. Depress Res Treat 2016;2016:2824595 10.1155/2016/2824595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miller TQ, Markides KS, Black SA. The factor structure of the CES-D in two surveys of elderly Mexican Americans. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1997;52:S259–S269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rhee SH, Petroski GF, Parker JC, et al. A confirmatory factor analysis of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in rheumatoid arthritis patients: additional evidence for a four-factor model. Arthritis Care Res 1999;12:392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang M, Armour C, Wu Y, et al. Factor structure of the CES-D and measurement invariance across gender in Mainland Chinese adolescents. J Clin Psychol 2013;69:966–79. 10.1002/jclp.21978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological measurement 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tatar A, Saltukoglu G. The Adaptation of the CES-depression scale into turkish through the use of confirmatory factor analysis and item response theory and the examination of psychometric characteristics. Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bülteni-Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2010;20:213–27. 10.1080/10177833.2010.11790662 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shrestha G, Yadav DK, Sapkota N, et al. Depression among inmates in a regional prison of eastern Nepal: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17:348 10.1186/s12888-017-1514-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lacasse JJ, Forgeard MJ, Jayawickreme N, et al. The factor structure of the CES-D in a sample of Rwandan genocide survivors. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2014;49:459–65. 10.1007/s00127-013-0766-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moges MF. Translation And Adaptation Of The Center For Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) Scale into Tigrigna Language For Tigrigna Speaking Eritrean Immigrants in the United States: Theses and Dissertations, 2011. PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miller KE, Weine SM, Ramic A, et al. The relative contribution of war experiences and exile-related stressors to levels of psychological distress among Bosnian refugees. J Trauma Stress 2002;15:377–87. 10.1023/A:1020181124118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Noh S, Speechley M, Kaspa V, et al. Depression in Korean immigrantsin Canada. Method of the study and prevalence of depression. Journal of Nervousand Mental Disease 1992;180:573–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baron EC, Davies T, Lund C. Validation of the 10-item centre for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D-10) in zulu, xhosa and afrikaans populations in South Africa. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17:6 10.1186/s12888-016-1178-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Makambi KH, Williams CD, Taylor TR, et al. An assessment of the CES-D scale factor structure in black women: The Black Women’s Health Study. Psychiatry Res 2009;168:163–70. 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aoki S, Tsuda A, Horiuchi S, et al. Factor structure of the center for epidemiologic studies depression Scale in South Korea. Open Journal of Medical Psychology 2014;03:301–5. 10.4236/ojmp.2014.34031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Al-Modallal H. Screening depressive symptoms in Jordanian women: evaluation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale (CES-D). Issues Ment Health Nurs 2010;31:537–44. 10.3109/01612841003703329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rivera-Medina CL, Caraballo JN, Rodríguez-Cordero ER, et al. Factor structure of the CES-D and measurement invariance across gender for low-income Puerto Ricans in a probability sample. J Consult Clin Psychol 2010;78:398–408. 10.1037/a0019054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Women’s Refugee Commission. Young and Astray: An Assessment of Driving the Movement of an accompanied Children and Adolescents from Eritrea into Ethiopia, Sudan and Beyond. New York, 2013. https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/images/. [Google Scholar]

- 28. United Nations Higher Commissioner for Refugees. Ethiopia, Operational Overview: Camp Demographic Population statistics by Office and Region. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Auguststatisticspackage.pdf (As of 31 Aug 2013).

- 29. Holzaepfel EA, Ethiopia T. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Livelihoods Programs for Refugees in Ethiopia, United States Department of State. Washington, 2015. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/252133. [Google Scholar]

- 30. United Nations Higher Commissioner for Refugees Fact Sheet, 2015. http://www.unhcr.org.

- 31. de Jong JT, Komproe IH, Van Ommeren M, et al. Lifetime events and posttraumatic stress disorder in 4 post-conflict settings. JAMA 2007;266:255–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Onyut LP, Patience L, Neuner F, et al. The Nakivale Camp Mental Health Project: Building Local Competency for Psychological assistance to Traumatized Refugees. Intervention 2004;2:90–107. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kamau M, Silove D, Steel Z, et al. Psychiatric disorders in an african refugee camp. Intervention 2004;2:84–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ommern MV, de Jong JTV. Preparing instruments for cross-cultural research. Use of the translation monitoring form with Nepali speaking Bhutanese refugees. Trans-cultural psychiatry;36:285–301. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lynn MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res 1986;35:382–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health 2006;29:489–97. 10.1002/nur.20147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological measurement 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Idemudia ES, Williams JK, Wyatt G. Gender difference in trauma and post traumatic stress symptoms among displaced zimbabweans in South Africa. J Trauma Stress Disorder Treat 2013;2:1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Idemudia ES, Williams JK, Madu SN, et al. Trauma exposures and post traumatic stress among zimbabwean refugees in South Africa. Life Science Journal 2013;10:2397–497. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC–PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry 2004;9:9–14. 10.1185/135525703125002360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bliese PD, Wright KM, Adler AB, et al. Validating the primary care posttraumatic stress disorder screen and the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist with soldiers returning from combat. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008;76:272–81. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA 2006;295:1023–32. 10.1001/jama.295.9.1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Taylor EM, Yanni EA, Pezzi C, et al. Physical and mental health status of Iraqi refugees resettled in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health 2014;16:1130–7. 10.1007/s10903-013-9893-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Caitlin M. Somali refugee interpretations of trauma-related mental illness: Similarities and differences between the somali concepts of ‘MurugoJoogto’ and ‘Qulub’ and PTSD. Undergraduate Research Journal at the University of Northern Colorado 2013;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Araya M, Chotai J, Komproe IH, et al. Gender differences in traumatic life events, coping strategies, perceived social support and sociodemographics among postconflict displaced persons in Ethiopia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2007;42:307–15. 10.1007/s00127-007-0166-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med 1993;36:725–33. 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Almedom AM, Tesfamichael B, Saeed Mohammed Z, et al. Use of ’sense of coherence (SOC)' scale to measure resilience in Eritrea: interrogating both the data and the scale. J Biosoc Sci 2007;39:91–107. 10.1017/S0021932005001112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dalgard OS, Dowrick C, Lehtinen V, et al. Negative life events, social support and gender difference in depression: a multinational community survey with data from the ODIN study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006;41:444–51. 10.1007/s00127-006-0051-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Abiola T, Udofia O, Zakari M. Psychometric properties of the 3-Item oslo social support scale among clinical students of bayero university, Kano, Nigeria;. Malaysian Journal of Psychiatry 2013;22:2. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hodgson R, Alwyn T, John B, et al. The FAST AlcoHol screening test. Alcohol Alcohol 2002;37:61–6. 10.1093/alcalc/37.1.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Meneses-Gaya C, Crippa JA, Zuardi AW, et al. The fast alcohol screening test (FAST) is as good as the AUDIT to screen alcohol use disorders. Subst Use Misuse 2010;45:1542–57. 10.3109/10826081003682206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fekadu A, Medhin G, Selamu M, et al. Population level mental distress in rural Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14:194 10.1186/1471-244X-14-194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mutumba M, Tomlinson M, Tsai AC. Psychometric properties of instruments for assessing depression among African youth: A systematic review. J Child Adolesc Ment Health 2014;26:139–56. 10.2989/17280583.2014.907169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Milfont TL, Fischer R. Testing measurement invariance across groups: applications in cross-cultural research. Int J Psychol Res 2010;3:111–21. 10.21500/20112084.857 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schreiber JB, Nora A, Stage FK, et al. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J Educ Res 2006;99:323–38. 10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brown TA. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. Newyork: Guilford press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Getnet B, Medhin G, Alem A. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression among Eritrean refugees in Ethiopia: identifying direct, meditating and moderating predictors from path analysis. BMJ Open 2019;9:e021142 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Getnet B, Alem A. Construct validity and factor structure of sense of coherence (SoC-13) scale as a measure of resilience in Eritrean refugees living in Ethiopia. Confl Health 2019;13 10.1186/s13031-019-0185-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Assari1 S and Moazen-Zadeh E. confirmatory Factor analysis of the 12-item center for epidemiologic studies Depression scale among Blacks and Whites. Frontiers in psychiatry 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. McCauley SR, Pedroza C, Brown SA, et al. Confirmatory factor structure of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale (CES-D) in mild-to-moderate traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2006;20:519–27. 10.1080/02699050600676651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tatar A, Saltukoglu G. The adaptation of the CES-depression scale into turkish through the use of confirmatory factor analysis and item response theory and the examination of psychometric characteristics. Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bülteni-Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2010;20:213–27. 10.1080/10177833.2010.11790662 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wu Q, Erbas Y, Brose A, et al. The factor structure, predictors, and percentile norms of the center for epidemiologic studies depression (CES-D) scale in the dutch-speaking adult population of Belgium. Psychol Belg 2016;56:1–12. 10.5334/pb.261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Morin AJS, Moullec G, Maïano C, et al. amp;Ninot G. Psychometric properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES- D) in French Clinical and Non-Clinical Adults. Epidemiology and Public Health/Revue d’Épidémiologie et de SantéPublique 2011;59:327–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Carleton RN, Thibodeau MA, Teale MJ, et al. The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale: a review with a theoretical and empirical examination of item content and factor structure. PLoS One 2013;8:e58067 10.1371/journal.pone.0058067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lu A, Bond MH, Friedman M, Chan C. Understanding cultural influences on depression by analyzing a measure of its constituent symptoms. International Journal of Psychological Studies 2010;2:55–70. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Huang Y, Fang L. Understanding depression from different paradigms: Toward an eclectic social work approach. British Journal of Social Work 2015;46:1–17. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026129supp001.docx (199.2KB, docx)