Abstract

Introduction

A review of international and Australian school-based resources suggests that teaching of the ovulatory-menstrual (OM) cycle is predominantly couched in biology. A whole-person framework that integrates spiritual, intellectual, social and emotional dimensions with the physical changes of the OM cycle is needed to facilitate adolescent OM health literacy. This paper describes the protocol for a study that aims to develop and trial an intervention for adolescent girls aged 13–16 years that enhances positive attitudes towards OM health coupled with developing skills to monitor and self-report OM health. These skills aim to foster acceptance of the OM cycle as a ‘vital sign’ and facilitate confident communication of common OM disturbances (namely, dysmenorrhoea, abnormal uterine bleeding and premenstrual syndrome), which are known to impact school and social activities.

Methods and analysis

Phase I will comprise a Delphi panel of women’s health specialists, public health professionals and curriculum consultants and focus groups with adolescent girls, teachers and school healthcare professionals. This will inform the development of an intervention to facilitate OM health literacy. The Delphi panel will also inform the development of a valid and reliable questionnaire to evaluate OM health literacy. Phase II will trial the intervention with a convenience sample of at least 175 adolescent girls from one single-sex school. The mixed-method evaluation of the intervention will include a pre-intervention and post-intervention questionnaire. One-on-one interviews with teachers and school healthcare professionals will expand the understanding of the barriers, enablers and suitability of implementation of the intervention in a school-based setting. Finally, focus groups with purposively selected trial participants will further refine the intervention.

Ethics and dissemination

The study findings will be disseminated through local community seminars, conferences, peer-review articles and media channels where appropriate. The Curtin University of Human Research Ethics Committee has approved this study (approval HRE2018-0101). This project is registered with the ‘Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry’.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12619000031167; Pre-results.

Keywords: school-based intervention, health literacy, menstruation, dysmenorrhoea, abnormal uterine bleeding, premenstrual syndrome

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The Delphi panel comprising experts from multiple disciplines adds rigour to the development of the school-based ovulatory-menstrual health literacy intervention.

A consumer-centred study that engages multiple stakeholders.

The mixed-methods approach allows for triangulation of quantitative and qualitative data.

The risks of bias and limited generalisability are present as participant recruitment in the phase II trial will be restricted to a single-sex private school and exclude parental inputs.

Limited funds restrict implementation and evaluation of trials in a larger sample of schools.

Introduction

The American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists Committee for Adolescent Health Care and the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence have jointly and repeatedly recommended that the ovulatory-menstrual (OM) cycle is to be considered a ‘vital sign’ in assessing overall health.1 2 For all young girls, menarche is the culmination of a sustained intricate hormonal interplay which is governed by the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis.3 As this ongoing cyclical process matures slowly,4 5 disturbances such as dysmenorrhoea, abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) and premenstrual syndrome (PMS) can present.6

Studies in Australia suggest the prevalence of dysmenorrhoea in adolescent girls ranges from 80% to 93%.7–10 International studies suggest similar rates of prevalence: 68% in Italy,11 69% in Nigeria,12 73% in Brazil13 and 83% in Singapore.14 Globally, the rates for girls with schooling affected because of dysmenorrhoea ranges from 12% to 37%.7 9 11 13 For women subsequently diagnosed with endometriosis, a recent literature review suggests considerable direct financial costs associated with this chronic disease, ranging from US$1109 (£682) to US$12 118 (£6170) per patient per year in Canada and the USA respectively.15 In Australia, the government has indicated its intention to create a National Action Plan for Endometriosis to provide support for women facing this medical condition.16

AUB menstrual disturbance can occur at both ends of reproductive life. Studies suggest that prevalence for adolescent girls ranges from 21% in Egypt17 and 33% Brazil13 to 40% in Australia.9 The costs of investigating and managing this variable condition are estimated around $A6 million (£2.65 million) per annum.18

Another common OM disturbance is PMS. A report of global studies posits its prevalence at 51%–86%, with comments that severe cases are disabling and can interfere with schooling and relationships.19 An early study found that a PMS diagnosis was associated with an average annual increase of US$59 (£30) in direct costs and US$4333 (£2271) in indirect costs per patient compared with patients without PMS.20

In Australian studies, the prevalence of adolescent girls consulting a healthcare professional about their menstrual disturbances ranged from 18% to 34%.7 9 10 Without diagnosis and treatment, cycle disorders worsen over time, as does any underlying pathology.21

Adolescent health literacy is an emerging field, and knowledge about it is not as extensive as that of adult health literacy.22 Nutbeam’s Health Outcome model23 offers a framework to explore adolescent health literacy. It begins by situating health literacy as a key outcome of health education. In this model, health literacy is realised after sequentially acquiring three core skills: functional skills (such as information search and comprehension), interactive skills (including personal application of health knowledge, engagement with health caregivers, decision-making and self-confidence) and critical skills to appraise information.23 Coincidentally, the progression from functional to critical health literacy skills aligns with the trajectory of adolescent cognitive and social development.24 Qualitative research in Britain applied the functional and interactive skills of Nutbeam’s model23 to understand how children make meaning of health information through their own embodied experience.25 One Canadian exploratory study extended the first two core skills of Nutbeam’s model23 to the final core skill of critical health literacy by using task-oriented measurements of evaluation.26 The three core skills of Nutbeam’s model23 will be used as a framework in this study to develop and evaluate OM health literacy in adolescents.

As girls grow, develop and begin assuming responsibility for their health, they are still minors: first, under the close care of parents and family, and second, under the wider care of healthcare professionals and teachers. Schools play an important role in developing health literacy because of curriculum requirements around personal development27 28 and the time children spend in education.

However, in Australia, many teachers lack training and confidence to facilitate contemporary relationships and sexuality education (RSE). In primary schools, qualitative studies have observed a tendency for teachers to outsource puberty education29 30 and that less than half of the female teachers felt very confident in teaching menstruation.31 In primary and secondary schools, a lack of confidence has been noted in teachers to deliver RSE programmes.32 33 A synthesis of international qualitative reviews of school-based RSE programmes suggests that teachers are best placed to fulfil the needs of continuity and meeting key curriculum outcomes. It was noted that some teachers were embarrassed about teaching RSE, which may be linked to their poor training.34 In Australia, RSE training is not mandatory for pre-service teachers, and so not all teachers may have received this training.35 This could negatively impact the supporting of girls to develop their OM health literacy.

Furthermore, available educational resources in Australia on OM cycles focus predominantly on ovulation and menstruation as biological events.36–39 The resources contain limited information about ovulation as the governing event of the OM cycle. In some regions of New Zealand, a school-based menstrual health education programme on endometriosis (the me programme) has been delivered annually since 1997.40 The me programme is delivered in one 60 minutes' session, akin to the vaccination model.29 This short time-frame is problematic in equipping adolescents with the skills to recognise their own OM cycle patterns because the OM cycle is complex, highly individualised and fluctuates over weeks. Additionally, the me programme focuses on only one common OM disturbance, and it is predicated on a negative OM experience rather than framing OM health positively. The Rite Journey programme41 in Australia was adapted for girls and it could be considered to overcome these drawbacks through its fertility awareness challenge of charting one cycle to identify the individual’s unique OM pattern.42 No data exist to measure if teachers are equipped to teach OM health or if this aspect of the programme is offered. These programmes neither promote the OM cycle as a ‘vital sign’, its use as a personal health monitor to identify common OM disturbances1 2 nor its place within the core skill set of critical health literacy.23 In addition, more evidence is needed on their effect on girls’ attitudes to the OM cycle and measures of their confidence in explaining their OM experiences to healthcare professionals.

Methods and analysis

Research objectives

This study aims to develop and trial an OM health literacy intervention for delivery to female students aged 13–16 years. The study objectives will be completed in two phases:

Phase I: Development

To develop a school-based adolescent OM health literacy intervention after consultation with experts in health and education, and with the primary (adolescent girls) and secondary (teachers and school healthcare professionals) target groups.

To develop a valid and reliable questionnaire to measure adolescent OM health literacy.

Phase II: Intervention trial

To trial the intervention in one single-sex secondary school.

To refine the intervention after consultation with the primary and secondary target groups.

To provide recommendations regarding the future utility of the intervention.

Patient and public involvement

The students, teachers and school healthcare professionals who will be invited to participate in this study have not been involved in the development of the research question, study design or the outcome measures. The schools involved in this study will be provided a summary of the research findings. The results will also be published in peer-review journals.

Research setting

The study will be based in Perth, Western Australia. In phase I, five schools will be invited to offer female students, teachers and school healthcare professionals the opportunity to participate in focus groups. Both private and public schools will be approached. Representation across various socio-demographic backgrounds will be sought based on the schools’ Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage values.43 The setting for phase II will be one purposively selected single-sex school in the Perth metropolitan area. Only private schools will be approached in this phase because there are no single-sex public schools in Perth. The school will be single-sex rather than co-educational (mixed sexes) in order to eliminate any study burden of occupying male students. Subsequent studies may explore the efficacy of this intervention in a co-educational setting. To avoid possible testing effects, schools in phase I will not be approached for phase II.

Phase I: Development

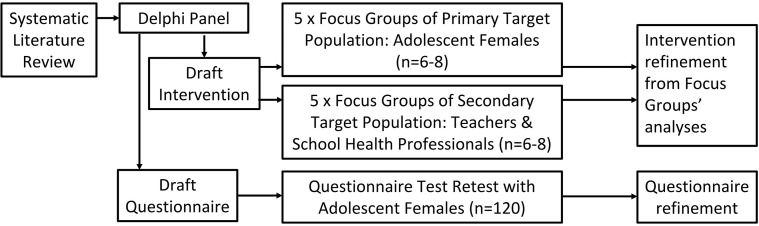

The development phase of the OM health literacy intervention and questionnaire is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of phase I – development of the ovulatory-menstrual health literacy intervention.

A Systematic Literature Review (SLR) of OM health programmes for adolescent girls

The SLR will include an assessment of previous reviews of OM health programmes and primary studies published in English using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram and check list.44 The search time-period spans 39 years, dating from 1 January 1980 to 31 December 2018. The year 1980 marks the publication of a mainstream book which used Odeblad’s findings45 to describe OM cycle phases.46 Key search words will include: [adolescen* OR teen?age*] AND [menstrua* OR menarch*, ovulat* OR fertil* OR reproduc*] AND [educat* OR teach* OR school*] AND [chart* OR record* OR track* OR diary] AND [knowledge OR aware* OR ‘health literacy’] AND [attitude OR opinion OR ‘body image’ OR confidence]. The databases to be searched are CINAHL, Informit, Ovid, Proquest, Science Direct, Medline, Web of Science and Scopus. The SLR aims to identify components that would enhance the opportunity for changes in knowledge, attitude and help-seeking behaviours in adolescent girls. Studies which do not demonstrate review by a healthcare professional or are not school-based will be excluded. Each study will be assessed on how it addresses:

- The primary target population (adolescent girls aged 13–16 years), and with consideration of:

- comprehensiveness (such as coverage of common complaints, evidence of programme development by fertility specialists and guidance for participants to identify personal OM cycle phases);

- fostering a positive attitude towards the OM cycle (eg, the Australian Medical Association has suggested a relationship between education and body image)47; and

- fostering an improvement in confidence to communicate with healthcare professionals.

The secondary target population (teachers and school healthcare professionals), and with consideration of content and integration within the curricula, ease and comfort of the programme delivery, training, efficacy of delivery in school-based settings, dissemination and programme evaluation.

The expected outcome from conducting the SLR is that it will inform the draft development of the intervention which will then be submitted to the Delphi panel for further development.

Delphi study

A Delphi study offers a consensus building method through group communication and feedback from a panel of experts in the field.48 For this study’s purposes, the classes of experts have been identified49 as women’s health specialists, public health professionals and curriculum consultants. Delphi studies do not rely on statistical power, but rather group dynamics, for achieving consensus, with the literature suggesting 10–18 experts.49 The panel’s first task will be to inform the development of the intervention by collecting their feedback on how the intervention can:

Be mapped to the mandated Health & Physical Education curriculum for Grades 9 and 10 (ages 13–16 years) in Western Australia.27

Incorporate the whole-person framework for the following dimensions of a human being: spiritual, physical, intellectual, social and emotional.

- Address the needs of:

- The primary target group (such as materials and the format, number and length of class sessions, which the literature for school-based menstrual health and well-being promotional interventions will have preliminarily indicated).50–52

- The secondary target group (such as material guides and a professional support and development plan).

The Delphi panel’s feedback on the intervention’s development will be collated as a preliminary draft. In its review, members will be able to suggest items that might not have been initially considered.49 Subsequent iterations will identify and rank the most important factors until members achieve 70% consensus on the draft intervention.49 53

The Delphi panel’s second task will be to refine the questionnaire to measure OM health literacy using existing valid and reliable items and scales to test:

Adolescent health literacy.22 26 54–58

Knowledge, attitudes and experiences of menstruation.59–63

The Delphi panel will be asked to evaluate how the items and scales meet the study’s aims and objectives, and to make alternative contributions. Their feedback will be collated as a preliminary draft questionnaire, which will be reviewed and ranked in an iterative process to identify and rank the items,49 with consensus achieved at 70%53 to provide content validation.48

Focus groups of the primary target population

Focus groups with adolescent girls will be conducted to gain insight into64 and to elicit priorities for issues65 to be included in the intervention. To reduce the possibility of distress, 16-year-old girls will be approached because most will have already been menstruating for up to 3 years and are more likely to be familiar with the responsibilities and experience of their OM cycles. Personal information will not be solicited, but rather what the participants believe to be important for adolescent OM health in general. This creates an opportunity to explore socio-ecological influences66 that may shape an adolescent’s approach to OM self-management. However, exploration of girls’ parents or guardians as enablers or barriers to OM health literacy lies outside the scope of this study. Each of the five socio-demographically diverse schools will be asked to purposively select six to eight 16-year-old female students to form one focus group.67 A total of 30 to 40 participants will thus be allocated into five focus groups (n=6–8 per group).

Focus groups of the secondary target population

Teachers from health, physical education, science and religious studies and school healthcare professionals (such as nurses, psychologists and counsellors) are the most likely group to implement the intervention in phase II and beyond.68 They may provide insight65 into mapping the intervention to the curriculum and its practical facilitation in class. The purpose is to gain an understanding of the issues surrounding the programme’s content, delivery, training and future continuation. Each of the five socio-demographically diverse schools will be asked to purposively select six to eight of their teachers and school healthcare professionals to form one focus group. In total, 30 to 40 participants will be allocated into five focus groups (n=6–8 per group).

Additional focus groups in either population may be recruited to saturation, which is consistent with qualitative research.69 The focus groups will be facilitated by the research team using a semi-structured interview guide, and conducted at a suitably quiet location at each school.

Qualitative data analysis

Focus groups’ data will be digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. To maintain dependability and determine credibility, the data will be reviewed by three researchers, two of whom have extensive experience in this field.70 71 Data will be coded using NVivo V.10 software. A constant comparison analysis will allow for the thematic discovery72 that is necessary to finalise the intervention development. The 32-item Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ-32)73 will be used to report on the conduct, method, context, findings, analysis and interpretations of the qualitative studies. The key findings based on the SLR, Delphi Panel and COREQ-32 will inform the refinement of the intervention in preparation for its trial. The expected outcomes are improvements in the intervention’s feasibility and acceptability for its delivery in phase II.

Questionnaire test-retest

A group of at least 120 adolescent girls50 74 75 will be recruited from one school to assess test-retest reliability of the questionnaire over a fortnight.76 To thank them for their time, the participants will be invited to enter a draw for a $A30 gift voucher at each sitting. Questionnaires will be administered online through Qualtrics. Participants will enter their responses in real time from either personal or school supplied devices. The test-retest reliability will be deemed acceptable at Cronbach’s alpha value >0.70.77 The research team will use the findings of the test-retest process to refine the questionnaire for use in phase II. The expected outcome is established validity and reliability for the questionnaire to be administered in phase II.

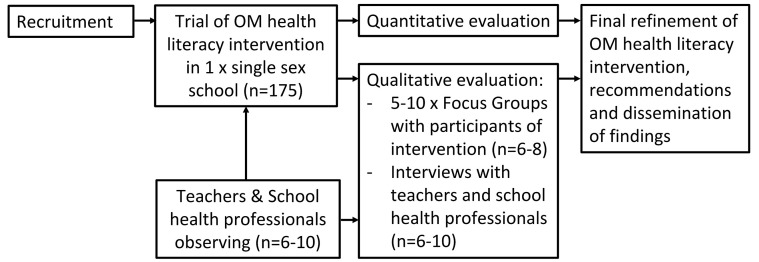

Phase II: Trial

The trial and evaluation of the OM health literacy intervention is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of phase II – trial of the ovulatory-menstrual (OM) health literacy intervention.

One single-sex private school in Perth WA will be purposively selected. The trial will be offered in-class at the school’s convenience. While the intervention will be mapped to the Australian curriculum for Health & Physical Education,27 the school’s preference for its delivery in other classes will be observed. For the purpose of the trial, the intervention will be delivered by the first author who has expertise in the facilitation of RSE programmes to 13–16 year-old students. It is anticipated that the trial will run for 6 to 8 weekly sessions during one school term, which will reduce the risk of participant loss. Both primary and secondary target populations will be recruited from the same school:

The primary target population will be adolescent girls aged 13–16 years. This age range falls in Grade 9, at which the intervention is targeted and which also provides the likeliest opportunity to recruit given the curriculum time restrictions in more senior years. All Grade 9 girls will be invited.

The secondary target population will be teachers in health, physical education, science and religious studies, as well as the school’s healthcare professionals which may include the school nurses, psychologists and counsellors. These staff will be invited through convenience sampling to observe the delivery of the intervention.

Quantitative evaluation by adolescent participants

Using the questionnaire developed in phase I, the OM health literacy scores of the 13–16 year-old adolescent girls will be recorded at baseline and immediate post-intervention. To detect a medium-sized difference of 4 points between the baseline score and the immediate post-intervention score at 5% significance and 80% power, a sample size of at least n=105 is required. With 60% retention at post measurement,51 a total of at least 175 adolescent girls will be recruited.

It is expected that the OM health literacy scores will comprise four key aspects:

OM health knowledge;

OM health attitudes;

self-perceived confidence to communicate OM cycle health; and

ability to recognise OM cycle phases.

The scores will be assessed for normality. If normally distributed, the descriptive statistics of the OM health literacy scores will be reported in mean and SD. Paired t-tests will be used to compare the difference between baseline and immediate post-intervention. If the data are not normally distributed, descriptive statistics will be reported in median and IQR, and transformed or analysed using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Statistical significance will be achieved at p<0.05. Data will be analysed using STATA V.14 (StataCorp LP). The expected outcomes are that the OM health knowledge and attitudes of participants will have improved, and they will have gained confidence in communicating OM cycle health by being able to recognise OM cycle phases.

Qualitative evaluation with intervention participants

All Grade 9 intervention participants aged 13–16 years will be invited to qualitatively evaluate the study. A semi-structured interview guide will be used to:

explore understanding of OM health;

explore common attitudes towards OM health;

identify generic experiences of OM cycle charting; and

generate feedback on the course content and its structure.

Approximately three focus groups (n=6–8 per group) will be conducted in a quiet location at the school’s convenience. Additional focus groups may be recruited to saturation. This operates concurrently with sampling, data collection, coding, data comparison and analysis to allow theory to emerge.78

Qualitative evaluation with teachers and school healthcare professionals

The teachers and school healthcare professionals who observed the intervention’s trial will be invited to participate in a one-on-one semi-structured interview. The interview guide will discuss opinions on:

the appropriateness of the programme for the primary target group;

elements of the trial that were successful and those which need modification; and

items required to address the efficacy of implementation in schools (such as resources to implement the programme, how to equip teachers and school healthcare professionals to deliver the programme, and how well it maps to the curriculum).

Qualitative data analysis

While conducting the student focus groups and school staff interviews, new threads of interest may arise. The discussion guides may be modified for subsequent focus groups and interviews.79 This allows for questions to be modified as part of the understanding process.80 The focus groups and interviews will be conducted to saturation, which will be determined when no new concepts surface from repeated data review.78

The qualitative data generated from the focus groups and interviews will be recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data will be coded with NVivo and then discussed and reviewed by the research team. A grounded theory approach has been selected because it aims to make theoretical assumptions that can be verified.72 81 This systematic approach accentuates the mixed methods approach.82 The theory developed should explain variations in behaviour while representing the main concerns and ideas of the participants.83 Accordingly, the data will be analysed by constant comparison, whereby data is continually sorted and the information is coded into commonly occurring key themes.80 After final coding, the data will be thematically analysed to include the perspectives that emerged and allow for an inductive development of theory.72 This process is consistent with those of other qualitative studies.79 84 COREQ-32 will be used to report the conduct, method, context, findings, analysis and interpretations of the qualitative studies.73 The expected outcome is that the qualitative findings will provide a richer understanding of the intervention from the perspective of the students, teachers and school healthcare professionals. These data will be triangulated with the quantitative findings to further refine the intervention.

In summary, the qualitative and quantitative instruments used in this study’s mixed-method approach offer a triangulation of data sources to cross-check and inform the development and trialling of the intervention. Each step in phase I will inform the next step in order to progress the intervention’s development and to validate the questionnaire as a measurement tool. In turn, phase I provides the intervention and its validated questionnaire for trial in phase II. The final outcome expected at the end of phase II is a more nuanced and refined intervention for wider testing. A subsequent large intervention-based trial would include focus on generalisability and sustainability.

Ethics and dissemination

Prior to participation in the study, informed written consent will be obtained from parents or guardians and student participants. Each participant will be informed of the voluntary nature of the study, their right to withdraw at any time without prejudice, and maintenance of anonymity. Confidentiality procedures will include delinked data collection, direct computer entry of de-identified data, and encrypted data storage on secure computers. Focus groups and interviews will be held in familiar environments while mindful of the participants’ privacy and safety.

The questionnaire will be administered according to a standard protocol that includes eligibility checks, confidentiality, ethical consent and administering incentives. Communication with participants will be age-appropriate. Information about suitable support services will be given to all participants and referral to a school healthcare professional will be made available for the participants if they become distressed by the focus groups, questionnaire test-retest or participation in the intervention.

The dissemination of results will include:

A de-identified report of the study findings will be given to participating schools for dissemination to their staff and families for having generously participated.

Dissemination of the study’s findings to healthcare professionals, educationalists and academics through local community, health and education conferences and international peer-reviewed journals.

Presentations at school-based professional development workshops and community-based seminars including web-based settings, where appropriate, to encourage the integration of the study’s findings into public health and education policies.

Dissemination of the study’s questionnaire for use by researchers developing interventions for adolescent reproductive health literacy, and by teachers delivering puberty programmes as part of sexuality and relationship education in accordance with curricula requirements.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to development and conceptualisation of the protocol. FR was responsible for drafting and coordinating the authors’ contributions. SB, HJC and JH were responsible for editing and guidance on the paper. All authors were responsible for critically revising the paper. All authors approved the final version of this paper.

Funding: This research project is funded through the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship Award Number CHESSN8617438119 and administered through the doctoral program run at Curtin University’s School of Public Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval has been obtained from Curtin University (HRE2018-0101). Additional ethics approval will be sought at key milestones as stipulated by HREC.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care. Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Pediatrics 2006;118:2245–50. 10.1542/peds.2006-2481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care. Opinion no. 651: Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e143–e146. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child 1969;44:291–303. 10.1136/adc.44.235.291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quint EH, Smith YR. Abnormal uterine bleeding in adolescents. J Midwifery Womens Health 2003;48:186–91. 10.1016/S1526-9523(03)00061-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams Hillard PJ, Hillard PA. Menstruation in Adolescents. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1135:29–35. 10.1196/annals.1429.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamieson MA. Disorders of menstruation in adolescent girls. Pediatr Clin North Am 2015;62(4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hillen TI, Grbavac SL, Johnston PJ, et al. Primary dysmenorrhea in young Western Australian women: prevalence, impact, and knowledge of treatment. J Adolesc Health 1999;25:40–5. 10.1016/S1054-139X(98)00147-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitts MK, Ferris JA, Smith AM, et al. Prevalence and correlates of three types of pelvic pain in a nationally representative sample of Australian women. Med J Aust 2008;189:138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker MA, Sneddon AE, Arbon P. The menstrual disorder of teenagers (MDOT) study: determining typical menstrual patterns and menstrual disturbance in a large population-based study of Australian teenagers. BJOG 2010;117:185–92. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02407.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Subasinghe AK, Happo L, Jayasinghe YL, et al. Prevalence and severity of dysmenorrhoea, and management options reported by young Australian women. Aust Fam Physician 2016;45:829–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zannoni L, Giorgi M, Spagnolo E, et al. Dysmenorrhea, absenteeism from school, and symptoms suspicious for endometriosis in adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2014;27:258–65. 10.1016/j.jpag.2013.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nwankwo TO, Aniebue UU, Aniebue PN. Menstrual disorders in adolescent school girls in Enugu, Nigeria. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2010;23:358–63. 10.1016/j.jpag.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitangui AC, Gomes M, Lima A, et al. Characteristics and effects on the activities of daily living among adolescent girls from Brazil. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2013;26:148–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarwal A, Venkat A. Questionnaire study on menstrual disorders in adolescent girls in Singapore. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2009;22:365–71. 10.1016/j.jpag.2009.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soliman AM, Yang H, Du EX, et al. The direct and indirect costs associated with endometriosis: a systematic literature review. Hum Reprod 2016;31:712–22. 10.1093/humrep/dev335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunt G. National action plan on endometriosis. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2017. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/ministers/publishing.nsf/Content/health-mediarel-yr2017-hunt130.htm (accessed Apr 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nooh AM, Abdul-Hady A, El-Attar N. Nature and prevalence of menstrual disorders among teenage female students at Zagazig university, Zagazig, Egypt. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2016;29:137–42. 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hickey M, Karthigasu K, Agarwal S. Abnormal uterine bleeding: a focus on polycystic ovary syndrome. Womens Health 2009;5:313–24. 10.2217/WHE.09.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rapkin AJ, Mikacich JA. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder and severe premenstrual syndrome in adolescents. Paediatr Drugs 2013;15:191–202. 10.1007/s40272-013-0018-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borenstein J, Chiou CF, Dean B, et al. Estimating direct and indirect costs of premenstrual syndrome. J Occup Environ Med 2005;47:26–33. 10.1097/01.jom.0000150209.44312.d1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vigil P, Ceric F, Cortés ME, et al. Usefulness of monitoring fertility from menarche. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2006;19:173–9. 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manganello JA, DeVellis RF, Davis TC, et al. Development of the Health literacy Assessment Scale for Adolescents (HAS-A). J Commun Healthc 2015;8:172–84. 10.1179/1753807615Y.0000000016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int 2000;15:259–67. 10.1093/heapro/15.3.259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sansom-Daly UM, Lin M, Robertson EG, et al. Health literacy in adolescents and young adults: an updated review. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2016;5:106–18. 10.1089/jayao.2015.0059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fairbrother H, Curtis P, Goyder E. Making health information meaningful: Children’s health literacy practices. SSM Popul Health 2016;2:476–84. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu AD, Begoray DL, Macdonald M, et al. Developing and evaluating a relevant and feasible instrument for measuring health literacy of Canadian high school students. Health Promot Int 2010;25:444–52. 10.1093/heapro/daq032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.School Curriculum and Standards Authority. Health & Physical Education Curriculum Pre-Primary to Year 10. Perth: Government of Western Australia, 2017. https://k10outline.scsa.wa.edu.au/home/p-10-curriculum/curriculum-browser/health-and-physical-education (accessed Apr 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Family Planning Alliance Australia. Position Statement: Relationship and Sexuality Education in Schools. Australia: FPPA, 2016. http://familyplanningallianceaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/FPAA-Schools-Education_Position-Statement_001_v2c.pdf (accessed Apr 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldman JDG. External providers' sexuality education teaching and pedagogies for primary school students in Grade 1 to Grade 7. Sex Educ 2011;11:155–74. 10.1080/14681811.2011.558423 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson RL, Sendall MC, McCuaig LA. Primary schools and the delivery of relationships and sexuality education: the experience of Queensland teachers. Sex Educ 2014;14:359–74. 10.1080/14681811.2014.909351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duffy B, Fotinatos N, Smith A, et al. Puberty, health and sexual education in Australian regional primary schools: Year 5 and 6 teacher perceptions. Sex Educ 2013;13:186–203. 10.1080/14681811.2012.678324 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith A, Schlichthorst M, Mitchell A, et al. Sexuality education in Australian secondary schools 2010: results of the 1st national survey of Australian secondary teachers of sexuality education. Melbourne: Australian Research Centre in Sex Health & Society, La Trobe University, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burns S, Hendriks J. Sexuality and relationship education training to primary and secondary school teachers: an evaluation of provision in Western Australia. Sex Educ 2018;18:672–88. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pound P, Langford R, Campbell R. What do young people think about their school-based sex and relationship education? A qualitative synthesis of young people’s views and experiences. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011329 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carman M, Mitchell A, Schlichthorst M, et al. Teacher training in sexuality education in Australia: how well are teachers prepared for the job? Sex Health 2011;8:269–71. 10.1071/SH10126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.New South Wales Education. The Menstrual Cycle. Sydney, Australia: Intel Corporation, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walsh J, soon T. Talk often: a guide for parents talking to their kids about sex. Victoria: Australian Research Centre in Sex Health & Society, La Trobe University, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Department of Health Western Australia. Puberty: Menstrual Cycle. Growing & Developing Healthy Relationships: curriculum support materials. Perth: Government of Western Australia, 2016. http://www.healthywa.wa.gov.au/Articles/N_R/Puberty-things-that-change-for-girls (accessed Apr 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Department of Health Western Australia. Girls and Puberty. Perth: Government of Western Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bush D, Brick E, East MC, et al. Endometriosis education in schools: A New Zealand model examining the impact of an education program in schools on early recognition of symptoms suggesting endometriosis. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2017;57:452–7. 10.1111/ajo.12614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lines A, Gallasch G. The Rite Journey: rediscovering rites of passage for boys. Boyhood Studies 2009;3:74–89. 10.3149/thy.0301.74 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lines A, Gallasch G, Hobbs A, et al. The rite journey for girls: a rite of passage programme for adolescents. Adelaide, Australia: Authenticity, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority. Guide to understanding 2013 Index of Community Socio-educational Advantage (ICSEA) values. Sydney: ACARA, 2013. www.myschool.edu.au (accessed Apr 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Odeblad E. The functional structure of human cervical mucus. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1968;47:57–79. 10.3109/00016346809156845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Billings E, Westmore A. The Billings method: controlling fertility without drugs or devices. Richmond, Victoria: Anne O’Donovan, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Australian Medical Association. Position statement: health in the context of education. Barton: ACT: AMA, 2014. www.ama.com.au (accessed Apr 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna HP. The Delphi technique in nursing and health research. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okoli C, Pawlowski SD. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inf Manage 2004;42:15–29. 10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fakhri M, Hamzehgardeshi Z, Hajikhani Golchin NA, et al. Promoting menstrual health among Persian adolescent girls from low socioeconomic backgrounds: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Public Health 2012;12:193 10.1186/1471-2458-12-193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Su JJ, Lindell D. Promoting the menstrual health of adolescent girls in China. Nurs Health Sci 2016;18:481–7. 10.1111/nhs.12295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tokolahi E, Hocking C, Kersten P. Development and content of a school-based occupational therapy intervention for promoting emotional well-being in children. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health 2016;32:245–58. 10.1080/0164212X.2015.1129522 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Humphrey-Murto S, Varpio L, Gonsalves C, et al. Using consensus group methods such as Delphi and nominal group in medical education research. Med Teach 2017;39:14–19. 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1245856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abel T, Hofmann K, Ackermann S, et al. Health literacy among young adults: a short survey tool for public health and health promotion research. Health Promot Int 2015;30:725–35. 10.1093/heapro/dat096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davis TC, Wolf MS, Arnold CL, et al. Development and validation of the rapid estimate of adolescent literacy in medicine (realm-teen): a tool to screen adolescents for below-grade reading in health care settings. Pediatrics 2006;118:e1707–e1714. 10.1542/peds.2006-1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McDonald FE, Patterson P, Costa DS, et al. Validation of a health literacy measure for adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2016;5:69–75. 10.1089/jayao.2014.0043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Osborne RH, Batterham RW, Elsworth GR, et al. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health 2013;13:658 10.1186/1471-2458-13-658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bradley-Klug K, Shaffer-Hudkins E, Lynn C, et al. Initial development of the health literacy and resiliency scale: youth version. J Commun Healthc 2017;10:100–7. 10.1080/17538068.2017.1308689 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aflaq F, Jami H. Experiences and attitudes related to menstruation among female students. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research 2012;27:201–24. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brooks-Gunn J, Ruble DN. The menstrual attitude questionnaire. Psychosom Med 1980;42:503–12. 10.1097/00006842-198009000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marván ML, Ramírez-Esparza D, Cortés-Iniestra S, et al. Development of a new scale to measure beliefs about and attitudes toward menstruation (BATM): data from Mexico and the United States. Health Care Women Int 2006;27:453–73. 10.1080/07399330600629658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morse JM, Kieren D, Bottorff J. The adolescent menstrual attitude questionnaire, part I: Scale construction. Health Care Women Int 1993;14:39–62. 10.1080/07399339309516025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.DeMaria EP, Mikulas WL. Women’s awareness of their menstrual cycle. Int J Sex Health 1992;4:71–82. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Byers P, Zeller R, Byers B. Focus group methods In: Weiderman M, Whitley B, eds Handbook for conducting research on human sexuality, 2002:173–93. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Carter SM, et al. Patients' priorities for health research: focus group study of patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2008;23:3206–14. 10.1093/ndt/gfn207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Greene S, Hogan D. Researching children’s experiences: methods and approaches. London: SAGE, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 68.McBride N. Intervention research: a practical guide for developing evidence-based school prevention programmes. Singapore: Springer, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carlsen B, Glenton C. What about N? A methodological study of sample-size reporting in focus group studies. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:26 10.1186/1471-2288-11-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liamputtong P. Research methods in health: foundations for evidence-based practice. 2nd ed Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liamputtong P. Qualitative research methods. 4th ed Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd ed: Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications Inc, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chiou MH, Wang HH, Yang YH. Effect of systematic menstrual health education on dysmenorrheic female adolescents' knowledge, attitudes, and self-care behavior. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2007;23:183–90. 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70395-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Janssen EH, Singh AS, van Nassau F, et al. Test-retest reliability and construct validity of the DOiT (Dutch Obesity Intervention in Teenagers) questionnaire: measuring energy balance-related behaviours in Dutch adolescents. Public Health Nutr 2014;17:277–86. 10.1017/S1368980012005253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Flisher AJ, Evans J, Muller M, et al. Brief report: Test-retest reliability of self-reported adolescent risk behaviour. J Adolesc 2004;27:207–12. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2001.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kilic S. Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient. Journal of Mood Disorders 2016;6:47–8. 10.5455/jmood.20160307122823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bowen GA. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: a research note. Qual Res 2008;8:137–52. 10.1177/1468794107085301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Burns S, Cross D, Maycock B. "That could be me squishing chips on someone’s car." How friends can positively influence bullying behaviors. J Prim Prev 2010;31:209–22. 10.1007/s10935-010-0218-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Boeije H. A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Quality and Quantity 2002;36:391–409. 10.1023/A:1020909529486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Harris T. Grounded theory. Nurs Stand 2015;29:32–9. 10.7748/ns.29.35.32.e9568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bluff R. Grounded Theory: The Methodology Holloway I, Qualitative Research in Health Care. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press, McGraw-Hill, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Glaser B. Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Burns S, Maycock B, Cross D, et al. The power of peers: why some students bully others to conform. Qual Health Res 2008;18:1704–16. 10.1177/1049732308325865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.