Abstract

Objectives

We investigated the associations between Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min, across the entire range of score values, and child developmental health at 5 years of age.

Setting

British Columbia, Canada

Participants

All singleton term infants without major congenital anomalies born between 1993 and 2009, who had a developmental assessment in kindergarten between 1999 and 2014.

Main outcomes and measures

Developmental vulnerability on one or more domains of the Early Development Instrument and special needs requirements. Adjusted rate ratios (aRRs) and 95% CIs were estimated using log-linear regression.

Results

Of the 150 081 children in the study, 45 334 (30.2%) were developmentally vulnerable and 3644 (2.5%) had special needs. There was an increasing trend in developmental vulnerability and special needs with decreasing 1 min and 5 min Apgar scores. Compared with children with an Apgar score of 10 at 5 min, the aRR for developmental vulnerability increased steadily with decreasing Apgar score from 1.02 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.04) for an Apgar score of 9 to 1.57 (95% CI 1.03 to 2.39) for an Apgar score of 2. Among children with 1 min Apgar scores in the 7–10 range, changes in Apgar scores between 1 and 5 min were associated with significant differences in developmental vulnerability. Compared with children who had an Apgar score of 9 at 1 min and 10 at 5 min, children with an Apgar score of 9 at both 1 and 5 min had higher rates of developmental vulnerability (aRR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.05). Compared with infants with an Apgar of 10 at both 1 and 5 min, infants with a 1 min score of 10 and a 5 min score of <10 had higher rates of developmental vulnerability (aRR 1.53, 95% CI 1.08 to 2.17).

Conclusion

Risks of adverse developmental health and having special needs at 5 years of age are inversely associated with 1 min and 5 min Apgar scores across their entire range.

Keywords: neonatology, epidemiology, fetal medicine, paediatrics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Ability to access comprehensive health-related and education-related databases at the population level.

Using a teacher-reported instrument, no reliance was placed on parental report of developmental health.

There may be some individual differences in teachers’ ability to evaluate developmental health on the Early Development Instrument.

Study was restricted to the comparatively healthy subset of all term live births, as children with severe disabilities may not have enrolled in kindergarten.

Introduction

In 1953, Virginia Apgar proposed a scoring system that enabled a rapid assessment of the clinical status of the newborn infant and identified infants requiring resuscitation on the basis of heart rate, respiration, colour, muscle tone and reflex irritability.1 Initially, the Apgar score at 1 min was used to assess the need for immediate resuscitation. Subsequently, the Apgar score at 5 min was shown to be a better predictor of neonatal survival than the Apgar score at 1 min. Although the value of a low Apgar score for accurately predicting adverse neurological outcomes at the individual level has been questioned,2 3 low Apgar scores are well correlated with both short-term4 and long-term outcomes, in both preterm and term infants.5–11

Only the lowest and more compromised Apgar scores have been conventionally regarded as predictive of maladaptive development and morbidity. Nevertheless, a few population-based studies have shown that risks of cerebral palsy, epilepsy, early developmental health status and need for special education are inversely associated with 5 min Apgar scores in a dose-dependent manner across the entire range of scores.12–14 Even children with an Apgar score of 9 at 5 or 10 min have an increased risk of adverse neurological outcomes compared with children with 5 min or 10 min Apgar scores of 10.12 13 Although approximately 65%–85% of newborns receive a 1 min or a 5 min Apgar score in the 7–9 range,13 there is a dearth of information on how this impacts a child’s developmental health.

Changes in Apgar score values between 1 and 5 min, and between 5 and 10 min are known to influence risks of cerebral palsy and epilepsy.12 15 16 Our recent population-based study demonstrated elevated risks of cerebral palsy and epilepsy among children with a 5 min Apgar score of 7 or 8, even if their 10 min Apgar score was 9 or 10.12 Although it is recognised that changes in Apgar scores between 1 and 5 min are a useful measure of the response to resuscitation, the long-term significance of changes in such Apgar scores within the ‘normal’ range (ie, 7–10) is not clear.

In this population-based study, we investigated the associations between Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min across the entire range of score values, and developmental health at 5 years of age. We also analysed the effect of a change in Apgar scores from 1 to 5 min, including changes within the normal range of Apgar scores. Specifically, we were interested in developmental health among children with 1 min Apgar scores in the 7–9 range who received a score less than 10 at 5 min.

Methods

The study was based on all singleton term infants without major congenital anomalies born between 1993 and 2009, who had a developmental assessment in kindergarten between 1999 and 2014. Information on the study population was obtained from several population-based linked health and demographic databases in British Columbia. The anonymised linked data used in this study included information from the Discharge Abstract Database,17 which comprised hospital admission and discharge records; the Vital Statistics Birth and Clinical Births18 databases, which contained information on all births in the province, along with delivery and neonatal health status, including diagnoses based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9 or ICD-10-CA) codes; the Census GeoData, which provided socioeconomic status (SES) data expressed as average neighbourhood income quintiles (based on census information from Statistics Canada and quantified using postal codes)19; the Consolidation File,20 which provided demographic information on study subjects and confirmed residency in the province; and the Early Development Instrument (EDI)21 data, which provided information on early childhood developmental health, and were accessed through linkage with the Human Early Learning Partnership.22 The EDI has been routinely administered province-wide in British Columbia every 1–3 years since the 1999/2000 school year, achieving at least 85% participation of kindergarten children from each school district. Teachers completed the EDI for each child in their kindergarten class (age range 5–7 years) in February. The EDI is designed to tap five core areas of early childhood development21–23: physical health and well-being; social competence; emotional maturity; language and cognitive development; and communication skills and general knowledge (online supplementary table 1).21 It consists of 104 binary and Likert-scale items, from which scores between 0 and 10 are calculated for each domain. The EDI also records demographic information on each child and whether the child has identified special needs.

bmjopen-2018-027655supp001.pdf (339.4KB, pdf)

The study population included all singleton term (≥37 weeks’ gestation) infants born between 01 April 1993 and 31 December 2009, who had documented 1 min and 5 min Apgar scores as well as a completed EDI assessment in kindergarten. Inclusion of infants with these birth dates meant that children were 5–7 years of age between 1999 and 2014 and part of the EDI assessment. The study population was restricted to infants without major congenital anomalies, identified using diagnosis codes from linked hospital records in the year after birth.

Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min were considered as the main exposures and examined both as discrete values from 0 to 10 and also as grouped categories (Apgar values of 0–3, 4–6, 7, 8, 9 and 10). Children with an Apgar score of 0 at 1 or 5 min who did not have a diagnostic code for birth asphyxia (ICD-9: 768.5, 768.6 and 768.9; ICD-10: P21), or an intervention code for either resuscitation or ventilation (Canadian Classification of Health Interventions: 1.GZ.30, 1.GZ31, 1.HZ.30, 1361, 1362, 1363, 1373, 1379 and 1004) were excluded from the study (n=470), as information on these cases likely resulted from transcription errors.

Developmental health assessment included whether a child had special needs or was developmentally vulnerable as measured by the EDI. Children were categorised as being developmentally vulnerable if their scores on the EDI fell below the 10th percentile value24 in any of the five domains, based on the national EDI cut-off scores.25 The 10th percentile cut-off has been recommended because it is higher and hence, more sensitive than clinical cut-off points of 3% or 5% for diagnosing developmental delay.21 Developmentally vulnerable children may not manifest developmental delays but may be at risk of experiencing challenges in school and society without additional support and care.26 Children with special needs were defined as requiring special assistance because of chronic medical, physical or intellectually disabling conditions.

Other independent variables examined included infant sex (male vs female), birth weight-for-gestational age, age of the child in years at the time of EDI assessment, gestational age at birth in completed weeks (37, 38, 39, 40, 41 and ≥42), birth order (1, 2, 3 and +4), marital status (married vs not married) and SES (quintiles). Birth weight-for-gestational age was categorised as: small (<10th percentile), appropriate (10th–90th percentile) and large (>90th percentile) for gestational age.27 Each child’s family income was derived from the median household income in the child’s residential area (based on postal code) obtained from the 2006 Canadian Census data.28–30

The frequency of each 5 min Apgar score value was calculated within categories of maternal and infant characteristics. Multivariable log-linear regression models with robust variance estimates31 were used to examine the association between Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min and developmental vulnerability and special needs. Results were expressed as crude and adjusted rate ratios (aRRs) with 95% CIs. Other variables included in the final models were based on the literature24 32 or statistical significance (p value <0.10). The full model included child’s sex, child’s age at EDI completion, SES, child’s first language, birth weight-for-gestational age, birth order and gestational age. Interactions between Apgar scores and other determinants were examined and stratified analyses were carried out when a significant interaction was present.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation of the findings.

Results

There were 150 081 children (mean age=5.7 years) with a gestational age at birth of ≥37 weeks, without major malformations and complete Apgar and EDI data included in the study. Information on special needs was available in 148 699 (99.1%) children. Five-minute Apgar scores showed a U-shaped association with gestational age at birth, with low scores more frequent at 37 weeks and ≥42 weeks (table 1). Low 5 min Apgar scores were comparable for most characteristics but more frequent among males, small-for-gestational-age live births, children of mothers who were nulliparous, not married and those with a low SES.

Table 1.

Maternal and birth characteristics according to Apgar score at 5 min among singleton term live births, British Columbia, 1993–2009

| Maternal and birth characteristics | Total | Apgar 0–3 (n=147) | Apgar 4–6 (n=1328) | Apgar 7 (n=2375) | Apgar 8 (n=7666) | Apgar 9 (n=101 191) | Apgar 10 (n=37 374) |

| No. (%) | % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Total | 150 081 (100) | ||||||

| Maternal age (years) | |||||||

| ≤19 | 6170 (4.11) | 0.15 | 1.41 | 1.93 | 5.80 | 64.17 | 26.55 |

| 20–24 | 24 637 (16.42) | 0.09 | 1.11 | 1.77 | 5.88 | 64.83 | 26.32 |

| 25–29 | 43 832 (29.21) | 0.10 | 0.88 | 1.64 | 5.19 | 66.66 | 25.54 |

| 30–34 | 47 332 (31.54) | 0.10 | 0.80 | 1.50 | 4.76 | 68.45 | 24.39 |

| ≥35 | 28 081 (18.71) | 0.09 | 0.72 | 1.39 | 4.73 | 69.89 | 23.17 |

| Missing | 29 (0.02) | 0 | <17.24 | <17.24 | <17.24 | 58.62 | 31.03 |

| Socioeconomic status | |||||||

| Fifth quintile (highest) | 27 519 (18.34) | 0.10 | 0.90 | 1.64 | 5.00 | 66.88 | 25.47 |

| Fourth quintile | 31 282 (20.84) | 0.11 | 0.83 | 1.69 | 5.38 | 66.79 | 25.21 |

| Third quintile | 30 939 (20.61) | 0.10 | 0.86 | 1.65 | 5.18 | 67.47 | 24.74 |

| Second quintile | 31 266 (20.83) | 0.06 | 0.84 | 1.48 | 5.08 | 67.73 | 24.80 |

| First quintile (lowest) | 28 889 (19.25) | 0.12 | 1.00 | 1.45 | 4.88 | 68.25 | 24.30 |

| Missing | 186 (0.12) | 0 | <2.69 | <2.69 | 3.23 | 66.13 | 28.49 |

| Married | |||||||

| Yes | 103 099 (68.70) | 0.09 | 0.78 | 1.47 | 4.73 | 68.43 | 24.49 |

| No | 43 374 (28.90) | 0.12 | 1.13 | 1.85 | 6.01 | 64.93 | 25.95 |

| Missing | 3608 (2.40) | 0.17 | 0.89 | 1.47 | 4.93 | 68.63 | 23.92 |

| Infant’s sex | |||||||

| Female | 73 809 (49.18) | 0.08 | 0.78 | 1.46 | 4.91 | 67.17 | 25.61 |

| Male | 76 272 (50.82) | 0.12 | 0.99 | 1.70 | 5.30 | 67.67 | 24.22 |

| Birth order | |||||||

| 1 | 67 516 (44.99) | 0.12 | 1.25 | 2.09 | 6.13 | 67.92 | 22.49 |

| 2 | 56 025 (37.33) | 0.09 | 0.63 | 1.24 | 4.32 | 67.51 | 26.22 |

| 3 | 19 239 (12.82) | 0.07 | 0.46 | 1.05 | 4.13 | 66.66 | 27.63 |

| ≥4 | 7301 (4.86) | <0.07 | 0.56 | 0.99 | 4.34 | 64.17 | 29.91 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | |||||||

| 37 | 8966 (5.97) | 0.10 | 1.08 | 2.02 | 6.88 | 68.02 | 21.89 |

| 38 | 25 821 (17.20) | 0.05 | 0.74 | 1.37 | 4.67 | 68.21 | 24.96 |

| 39 | 37 408 (34.03) | 0.09 | 0.76 | 1.32 | 4.36 | 68.57 | 24.89 |

| 40 | 51 079 (34.03) | 0.10 | 0.82 | 1.65 | 5.05 | 66.31 | 26.08 |

| 41 | 25 040 (16.68) | 0.15 | 1.22 | 1.87 | 6.08 | 67.38 | 23.29 |

| 42–44 | 1767 (1.18) | <0.28 | 1.58 | 2.09 | 6.51 | 61.35 | 28.3 |

| Birth weight-for-gestational age | |||||||

| Appropriate | 121 035 (80.65) | 0.09 | 0.84 | 1.51 | 4.96 | 67.42 | 25.18 |

| Small | 11 581 (7.72) | 0.19 | 1.35 | 2.20 | 6.16 | 67.04 | 23.06 |

| Large | 17 445 (11.62) | 0.08 | 0.85 | 1.65 | 5.47 | 67.76 | 24.18 |

| Missing | 20 (0.01) | <25.00 | <25.00 | 0 | 0 | 40.00 | 50.00 |

| Child’s age at EDI data collection (years) | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.70 (0.32) | 5.67 (0.30) | 5.65 (0.30) | 5.66 (0.30) | 5.66 (0.30) | 5.65 (0.30) | 5.65 (0.30) |

EDI, Early Development Instrument.

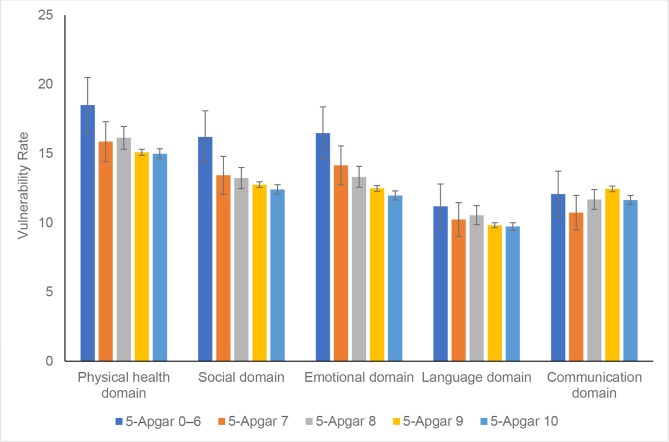

Overall, the prevalence of vulnerability in one or more domains of the EDI was 30.2%, with physical and social domains having the highest rates of vulnerability at 15.2% and 12.7%, respectively (figure 1). There was an increasing trend in the rate of developmental vulnerability with decreasing 1 min and 5 min Apgar scores (p for trend<0.001; table 2). However, this association was much more pronounced for the 5 min Apgar score. Compared with children with an Apgar score of 10 at 5 min, children with a 5 min Apgar score of 2 had a 57% higher rate of developmental vulnerability (aRR 1.57, 95% CI 1.03 to 2.39). Similarly, children with a 5 min Apgar score of 7, 8 or 9 had significantly higher rates of developmental vulnerability compared with children with a 5 min Apgar score of 10 (aRR 1.08, 1.06 and 1.02 for Apgar 7, 8 and 9, respectively; table 2). The association between 5 min Apgar scores and developmental vulnerability was mainly due to the higher rates of vulnerability in the language and emotional domains of the EDI (online supplementary table 2).

Figure 1.

Rates of vulnerability within the five Early Development Instrument domains by Apgar score at 5 min, British Columbia, Canada.

Table 2.

Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min and rate ratios for developmental vulnerability among singleton term live births, British Columbia, Canada

| Apgar score | Total number of children | Developmental vulnerability | ||

| No. with outcome (%) | Rate ratio (95% CI) | |||

| Crude | Adjusted* | |||

| 1 min Apgar | 150 081 | 45 334 (30.2) | ||

| 0 | 24 | 9 (37.5) | 1.25 (0.74 to 2.10) | 1.08 (0.64 to 1.83) |

| 1 | 469 | 161 (34.3) | 1.15 (1.00 to 1.31) | 1.16 (1.02 to 1.32) |

| 2 | 1060 | 329 (31.0) | 1.04 (0.93 to 1.15) | 1.03 (0.93 to 1.14) |

| 3 | 1760 | 546 (31.0) | 1.04 (0.95 to 1.13) | 1.03 (0.95 to 1.13) |

| 4 | 2582 | 814 (31.5) | 1.05 (0.97 to 1.14) | 1.07 (0.99 to 1.15) |

| 5 | 4069 | 1261 (31.0) | 1.03 (0.96 to 1.11) | 1.05 (0.98 to 1.12) |

| 6 | 6975 | 2124 (30.5) | 1.02 (0.95 to 1.08) | 1.04 (0.98 to 1.11) |

| 7 | 12 019 | 3648 (30.4) | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.08) | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.09) |

| 8 | 38 671 | 11 666 (30.2) | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.06) | 1.02 (0.96 to 1.08) |

| 9 | 79 369 | 23 852 (30.1) | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.06) | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.06) |

| 10 | 3083 | 924 (30.0) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| P for trend | <0.001 | |||

| Per one unit of Apgar | 0.99 (0.98 to 0.99) | |||

| 5 min Apgar | ||||

| 0 | 20 | 7 (35.0) | 1.18 (0.65 to 2.15) | 1.16 (0.62 to 2.17) |

| 1 | 16 | 9 (56.3) | 1.90 (1.24 to 2.93) | 1.88 (1.27 to 2.77) |

| 2 | 28 | 13 (46.4) | 1.57 (1.05 to 2.34) | 1.57 (1.03 to 2.39) |

| 3 | 83 | 30 (36.2) | 1.22 (0.92 to 1.63) | 1.25 (0.93 to 1.67) |

| 4 | 106 | 43 (40.6) | 1.37 (1.09 to 1.73) | 1.33 (1.06 to 1.67) |

| 5 | 290 | 85 (29.3) | 0.99 (0.83 to 1.19) | 0.98 (0.82 to 1.17) |

| 6 | 932 | 306 (32.8) | 1.11 (1.01 to 1.22) | 1.08 (0.99 to 1.18) |

| 7 | 2375 | 740 (31.2) | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.12) | 1.08 (1.01 to 1.14) |

| 8 | 7666 | 2387 (31.1) | 1.05 (1.02 to 1.09) | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.10) |

| 9 | 101 191 | 30 668 (30.3) | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.04) | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.04) |

| 10 | 37 374 | 11 046 (29.6) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| P for trend | <0.001 | |||

| Per one unit of Apgar | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99) | |||

*Adjusted for child’s sex (male vs female), child’s age at EDI completion (years), socioeconomic status (first quintile, second quintile, third quintile, fourth quintile vs fifth quintile), child’s first language (other vs English), birth order (2, 3, +4 vs 1), birth weight-for-gestational age (large, small vs appropriate) and gestational age (weeks).

EDI, Early Development Instrument.

In total, 3644 (2.5%) children had special needs (table 3). The proportion of children with special needs increased linearly with decreasing 1 min and 5 min Apgar scores (p for trend<0.001). Compared with children who had a 1 min Apgar score of 10, those with an Apgar score of 2 at 1 min had significantly higher adjusted rates of having special needs (aRR 1.72, 95% CI 1.19 to 2.48), while those with an Apgar score of 5 at 1 min had 1.39 times higher rate of having special needs (95% CI 1.05 to 1.85). Children with 5 min Apgar scores in the 1–8 range had higher adjusted rates for having special needs, which consistently increased with decreasing 5 min Apgar score values: from 1.20 in children with an Apgar score of 8 at 5 min to 5.13 among those with an Apgar score of 1 at 5 min. The aRRs for having special needs among children with 1 min and 5 min Apgar scores in the 0–3 range had wide 95% CIs because of small numbers of children in these categories.

Table 3.

Apgar score at 1 and 5 min and rate ratios for special needs status among singleton term live births in British Columbia, Canada

| Apgar score | Total number of children | Special needs | ||

| No. with outcome (%) | Rate ratio (95% CI) | |||

| Crude | Adjusted* | |||

| 1 min Apgar | 148 699 | 3644 (2.5) | ||

| 0 | 22 | <5 (4.6) | 1.94 (0.28 to 13.4) | 1.44 (0.23 to 8.97) |

| 1 | 463 | 26 (5.6) | 2.40 (1.55 to 3.72) | 2.23 (1.44 to 3.46) |

| 2 | 1054 | 45 (4.3) | 1.82 (1.26 to 2.63) | 1.72 (1.19 to 2.48) |

| 3 | 1743 | 53 (3.0) | 1.30 (0.91 to 1.84) | 1.23 (0.86 to 1.74) |

| 4 | 2554 | 69 (2.7) | 1.15 (0.83 to 1.60) | 1.09 (0.79 to 1.52) |

| 5 | 4032 | 136 (3.4) | 1.44 (1.09 to 1.91) | 1.39 (1.05 to 1.85) |

| 6 | 6894 | 191 (2.8) | 1.18 (0.90 to 1.55) | 1.16 (0.89 to 1.52) |

| 7 | 11 903 | 298 (2.5) | 1.07 (0.83 to 1.38) | 1.06 (0.82 to 1.37) |

| 8 | 38 300 | 946 (2.5) | 1.06 (0.83 to 1.34) | 1.07 (0.84 to 1.35) |

| 9 | 78 701 | 1808 (2.3) | 0.98 (0.78 to 1.24) | 1.00 (0.79 to 1.26) |

| 10 | 3033 | 71 (2.3) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| P for trend | <0.001 | |||

| Per one unit of Apgar | 0.99 (0.98 to 0.99) | |||

| 5 min Apgar | ||||

| 0 | 17 | <5 (<29.4) | 2.51 (0.37 to 16.8) | 2.59 (0.41 to 16.3) |

| 1 | 15 | <5 (<33.3) | 5.69 (1.56 to 20.7) | 5.13 (1.45 to 18.1) |

| 2 | 28 | <5 (<17.9) | 6.10 (2.46 to 15.2) | 5.17 (2.01 to 13.3) |

| 3 | 83 | 9 (10.8) | 4.63 (2.49 to 8.61) | 3.78 (2.03 to 7.02) |

| 4 | 103 | 7 (6.8) | 2.90 (1.41 to 5.95) | 2.59 (1.25 to 5.35) |

| 5 | 289 | 8 (2.8) | 1.18 (0.59 to 2.35) | 1.10 (0.56 to 2.16) |

| 6 | 928 | 36 (3.9) | 1.66 (1.19 to 2.30) | 1.49 (1.07 to 2.06) |

| 7 | 2342 | 74 (3.2) | 1.35 (1.07 to 1.70) | 1.28 (1.01 to 1.61) |

| 8 | 7597 | 225 (3.0) | 1.26 (1.09 to 1.46) | 1.20 (1.03 to 1.38) |

| 9 | 100 281 | 2411 (2.4) | 1.03 (0.95 to 1.11) | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.09) |

| 10 | 37 016 | 867 (2.3) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| P for trend | <0.001 | |||

| Per one unit of Apgar | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99) | |||

*Adjusted for child’s sex (male vs female), child’s age at EDI completion (years), socioeconomic status (first quintile, second quintile, third quintile, fourth quintile vs fifth quintile), child’s first language (other vs English), birth order (2, 3, +4 vs 1), birth weight-for-gestational age (large, small vs appropriate) and gestational age (weeks).

EDI, Early Development Instrument.

Table 4 presents rates of developmental vulnerability in relation to changes in Apgar score from 1 to 5 min, among children whose 1 min Apgar score was in the normal range (7–10). Among children with a 1 min Apgar score of 7, the rate of developmental vulnerability decreased in a dose–response manner with greater improvement in the Apgar score from 1 to 5 min (p value for dose response=0.02). Larger reductions in developmental vulnerability with greater improvements in 1 min to 5 min Apgar scores were also evident among children with a 1 min Apgar score of 9 (p value for trend=0.009) but not among children with a 1 min Apgar score of 8 (p value for trend=0.36). Children with an Apgar score of 9 at 1 min and 9 at 5 min had higher rates of developmental vulnerability compared with those who had Apgar scores of 9 at 1 min and 10 at 5 min (aRR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.05). Furthermore, compared with children who had Apgar scores of 10 at both 1 and 5 min, children whose 1 min Apgar score decreased from 10 to a 5 min Apgar score of <10, had 1.53 times the rate of developmental vulnerability (aRR 1.53, 95% CI 1.08 to 2.17).

Table 4.

Rate ratios for developmental vulnerability according to the combination of Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min, singleton term live births, British Columbia, Canada

| 1 min Apgar | 5 min Apgar | Total number of children | Developmental vulnerability | |||

| No. with outcome (%) | Rate ratio (95% CI) | |||||

| Crude | Adjusted* | P for trend | ||||

| 7 | <7 | 20 | 9 (45.0) | 1.62 (0.99 to 2.65) | 1.34 (0.80 to 2.25) | |

| 7 | 7 | 172 | 56 (32.6) | 1.18 (0.93 to 1.48) | 1.18 (0.94 to 1.47) | |

| 7 | 8 | 1987 | 629 (31.7) | 1.14 (1.02 to 1.28) | 1.12 (1.01 to 1.23) | |

| 7 | 9 | 8700 | 2637 (30.3) | 1.09 (0.99 to 1.20) | 1.08 (0.99 to 1.19) | |

| 7 | 10 | 1140 | 317 (27.8) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.024 |

| 8 | <8 | 66 | 17 (25.8) | 0.85 (0.56 to 1.28) | 0.71 (0.47 to 1.07) | |

| 8 | 8 | 1337 | 420 (31.4) | 1.03 (0.94 to 1.13) | 1.01 (0.92 to 1.10) | |

| 8 | 9 | 33 255 | 10 007 (30.1) | 0.99 (0.94 to 1.04) | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.02) | |

| 8 | 10 | 4013 | 1222 (30.5) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.36 |

| 9 | <9 | 140 | 48 (34.3) | 1.17 (0.93 to 1.47) | 1.10 (0.88 to 1.38) | |

| 9 | 9 | 50 976 | 15 501 (30.4) | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.06) | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.05) | |

| 9 | 10 | 28 253 | 8303 (29.4) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.009 |

| 10 | <10 | 26 | 13 (50.0) | 1.68 (1.14 to 2.47) | 1.53 (1.08 to 2.17) | |

| 10 | 10 | 3057 | 911 (29.8) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.016† |

*Adjusted for child’s sex (male vs female), child’s age at EDI completion (years), socioeconomic status (first quintile, second quintile, third quintile, fourth quintile vs fifth quintile), child’s first language (others vs English), birth order (2, 3, +4 vs 1), birth weight-for-gestational age (large, small vs appropriate) and gestational age (weeks).

†P value for difference in rates.

EDI, Early Development Instrument.

Discussion

In this population-based study, we found graded, continuously increasing risks of developmental vulnerability and special needs at 5 years of age with decreasing 1 min and 5 min Apgar scores. A low Apgar score at 5 min was more strongly associated with developmental vulnerability and special needs than a low Apgar score at 1 min. In particular, children with ‘normal’ 5 min Apgar scores of 7, 8 and 9 were more likely to have developmental vulnerability compared with children with 5 min Apgar scores of 10. Similarly, children who had Apgar scores of 7 or 8 at 5 min had higher risks of having special needs compared with those with a 5 min Apgar score of 10. Furthermore, children with a 1 min Apgar score in the normal range (7–10) had an increased risk of developmental vulnerability, if their Apgar score at 5 min was <10. Particularly, noteworthy was a reduction in the Apgar score from 10 at 1 min to 7–9 at 5 min, as this substantially increased the risk of developmental vulnerability.

Our results confirm previous findings from a smaller cohort, which showed that developmental adversity extended in a linear fashion across the full range of Apgar scores.13 Both research and clinical practice generally emphasise the increased risks of adverse outcomes associated with very low and less common Apgar scores (ie, <7 or <4). Our results suggest that the negative association between Apgar score and developmental adversity or special needs extends across the full range of scores. Consistent with our findings, previous studies have shown a significant linear relationship between each one-point decrease in 5 min and 10 min Apgar scores and increasing risk of epilepsy, cerebral palsy and needing education in a special school.12 14 While profound perinatal events can cause death or obvious neurological deficits, milder insults may sometimes cause subtle cognitive impairment only detectable as the child grows older and apparent only at a population level.

Our study also showed that changes in Apgar scores from 1 to 5 min were associated with developmental vulnerability. This is in agreement with previous studies showing that changes in Apgar scores immediately after birth influence risks of cerebral palsy and epilepsy.12 15 16 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that examined risks of developmental adversity in relation to changes in Apgar scores from 1 to 5 min. Current guidelines define ‘normal’ Apgar scores as 7 or more at 1 min and 8 or more at 5 min, indicating that the baby does not require assistance if scores are within these ranges.33 However, our results reveal that lower scores within the normal range (7–9) and even a slight reduction in score from 10 at 1 min to 9 at 5 min are both associated with a significant increase in the risk of developmental vulnerability. Similarly, infants who have low Apgar scores for prolonged, or even brief periods are reported to have a higher risk of poor IQ scores at age 18, even if the infants recover subsequently.6 The higher developmental vulnerability observed among infants whose optimal Apgar score (of 10) at 1 min falls with time after birth may be important clinically; such a progression may indicate problems with physiological circulatory, respiratory or central nervous system changes that follow delivery. Deterioration in the Apgar score immediately after birth, therefore, warrants re-evaluation of the infant and close clinical scrutiny in order to exclude congenital abnormalities and drug-induced depression of the central nervous system.

The strengths of our study included the ability to access comprehensive health-related and education-related databases at the population level. By using a teacher-reported instrument, no reliance was placed on parent or self-report of developmental health. Nonetheless, there may be some individual differences in teachers’ ability to evaluate developmental health on the EDI.25 Further, our study was restricted to the comparatively healthy subset of all term live births, as children with severe disabilities may not have enrolled in kindergarten or may have enrolled in special needs schools. Furthermore, although the EDI has broad coverage across British Columbia, it is collected less frequently in independent schools (30% coverage). We recognise that the Apgar score as recorded in medical charts represents routine clinical practice,34 and is prone to interobserver variability,34 specifically in intubated newborn babies.35 However, the quality of Apgar score values should not differ between children with and without subsequent diagnosed developmental vulnerability. Nevertheless, measurement errors inherent in routinely recorded Apgar scores (and possibly the EDI) may potentially explain the lack of an evident dose–response relationship between Apgar scores and developmental vulnerability. Finally, we acknowledge that the incidence of adverse outcomes in the setting of normal Apgar scores is rare and a low Apgar in the normal range is a poor predictor of developmental vulnerability for the individual infant.

In summary, our study showed that the risk of developmental vulnerability and special needs at 5 years of age was inversely associated with 1 min and 5 min Apgar scores across their entire range. Furthermore, improvements in Apgar scores between 1 and 5 min among children with a 1 min Apgar score of 7–9 were associated with a lower risk of developmental vulnerability. These results provide clinicians with valuable prognostic information and the justification to carefully monitor infants who are even mildly compromised at 1 and 5 min. Future studies should examine the underlying mechanism by which Apgar scores in the normal range could influence long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: NR conceptualised and designed the study, analysed the data, drafted the initial manuscript and finalised the manuscript based on co-authors' feedback. She had full access to all the data used in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. SC, MP, KT and SL reviewed and commented on the initial and final analyses, provided feedback on the initial draft of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. KJ assisted with conceptualisation and design of the study, reviewed and commented on the initial and final analyses, provided feedback on the initial draft of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: NR is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). KJ is supported by the BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute.

Disclaimer: All inferences, opinions and conclusions drawn in this journal article are those of the authors and do not reflect the opinions or policies of the data steward(s).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The University of British Columbia’s Clinical Research Ethics Board approved the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Apgar V. A proposal for a new method of evaluation of the newborn infant. Anesthesia & Analgesia 1953;32:260???267–7. 10.1213/00000539-195301000-00041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bharti B, Bharti S. A review of the Apgar score indicated that contextualization was required within the contemporary perinatal and neonatal care framework in different settings. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:121–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn, american College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. The Apgar Score. Pediatrics 2015;136:819–822. 10.1542/peds.2015-2651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li J, Cnattingus S, Gissler M, et al. The 5-minute Apgar score as a predictor of childhood cancer: a population-based cohort study in five million children. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001095 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moore EA, Harris F, Laurens KR, et al. Birth outcomes and academic achievement in childhood: A population record linkage study. Journal of Early Childhood Research 2014;12:234–50. 10.1177/1476718X13515425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Odd DE, Rasmussen F, Gunnell D, et al. A cohort study of low Apgar scores and cognitive outcomes. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2008;93:F115–F120. 10.1136/adc.2007.123745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Grijota M, et al. Association of Apgar score at five minutes with long-term neurologic disability and cognitive function in a prevalence study of Danish conscripts. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:14 10.1186/1471-2393-9-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marschik PB, Einspieler C, Garzarolli B, et al. Events at early development: are they associated with early word production and neurodevelopmental abilities at the preschool age? Early Hum Dev 2007;83:107–14. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krebs L, Langhoff-Roos J, Thorngren-Jerneck K. Long-term outcome in term breech infants with low Apgar score--a population-based follow-up. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2001;100:5–8. 10.1016/S0301-2115(01)00456-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cnattingius S, Norman M, Granath F, et al. Apgar score components at 5 minutes: risks and prediction of neonatal mortality. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2017;31:328–37. 10.1111/ppe.12360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tweed EJ, Mackay DF, Nelson SM, et al. Five-minute Apgar score and educational outcomes: retrospective cohort study of 751,369 children. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2016;101:F121–F126. 10.1136/archdischild-2015-308483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Persson M, Razaz N, Tedroff K, et al. Five and 10 minute Apgar scores and risks of cerebral palsy and epilepsy: population based cohort study in Sweden. BMJ 2018;360:k207 10.1136/bmj.k207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Razaz N, Boyce WT, Brownell M, et al. Five-minute Apgar score as a marker for developmental vulnerability at 5 years of age. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2016;101:F114–F120. 10.1136/archdischild-2015-308458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stuart A, Otterblad Olausson P, Källen K. Apgar scores at 5 minutes after birth in relation to school performance at 16 years of age. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118(2 Pt 1):201–8. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31822200eb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sun Y, Vestergaard M, Pedersen CB, et al. Apgar scores and long-term risk of epilepsy. Epidemiology 2006;17:296–301. 10.1097/01.ede.0000208478.47401.b6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moster D, Lie RT, Irgens LM, et al. The association of Apgar score with subsequent death and cerebral palsy: A population-based study in term infants. J Pediatr 2001;138:798–803. 10.1067/mpd.2001.114694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] [2012]. Discharge Abstract Database (Hospital Separations): Population Data BC [publisher]; Data Extract, 2012. http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data [Google Scholar]

- 18. British Columbia Vital Statistics Agency [creator] (2012). Vital Statistics Births: Population Data BC [publisher];Data Extract BC Vital Statistics Agenency, 2012. http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data [Google Scholar]

- 19. Statistics Canada [creater] (2009). Statistics Canada Income Band Data. Catalogue Number: 13C0016: Population Data BC [publisher]; Population Data BC, 2017. http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data [Google Scholar]

- 20. British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] [2012]. Consolidation File (MSP Registration & Premium Billing): Population Data BC [publisher]; Data Extract, 2012. http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Janus M, Offord DR. Development and psychometric properties of the Early Development Instrument (EDI): a measure of children’s school readiness. Can J Behav Sci 2007;39:1–22. 10.1037/cjbs2007001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Human Early Learning Partnership [creator] (2012) Early Development Instrument. Human Early Learning Partnership. Vancouver, BC: Population Data BC [publisher]; Data Extract; University of British Columbia, School of Population and Public Health, 2012. http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Duncan GJ, Dowsett CJ, Claessens A, et al. School readiness and later achievement. Dev Psychol 2007;43:1428–46. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Janus M, Duku E. The school entry gap: Socioeconomic, Family, and Health Factors Associated With Children’s School Readiness to Learn. Early Education & Development 2007;18:375–403. 10.1080/10409280701610796a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. The Offord Centre for Child Studies. Measuring in support of early childhood development: The Normative II report [Report]. 2012. http://www.offordcentre.com/readiness/files/updated_normative_II.pdf (Accessed 01 Apr 2013).

- 26. Brinkman S, Sayers M, Goldfeld S, et al. Population monitoring of language and cognitive development in Australia: The Australian Early Development Index. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 2009;11:419–30. 10.1080/17549500903147552 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, et al. A new and improved population-based Canadian reference for birth weight for gestational age. Pediatrics 2001;108:e35 10.1542/peds.108.2.e35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martens P. Health inequities in Manitoba: is the socioeconomic gap in health widening or narrowing over time? Winnipeg: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, University of Manitoba, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mustard CA, Derksen S, Berthelot J-M, et al. Assessing ecologic proxies for household income: a comparison of household and neighbourhood level income measures in the study of population health status. Health Place 1999;5:157–71. 10.1016/S1353-8292(99)00008-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health 1992;82:703–10. 10.2105/AJPH.82.5.703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:702–6. 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Santos R, Brownell MD, Ekuma O, et al. The Early Development Instrument (EDI) in Manitoba: linking socioeconomic adversity and biological vulnerability at birth to children’s outcomes at age 5. Winniepg, MB: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, University of Manitoba, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33. AAo P. The APGAR score. Adv Neonatal Care 2006;6:220–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. O’Donnell CPF, Kamlin COF, Davis PG, et al. Interobserver variability of the 5-minute Apgar score. J Pediatr 2006;149:486–9. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lopriore E, van Burk GF, Walther FJ, et al. Correct use of the Apgar score for resuscitated and intubated newborn babies: questionnaire study. BMJ 2004;329:143–4. 10.1136/bmj.38117.665197.F7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027655supp001.pdf (339.4KB, pdf)