Abstract

Introduction

The effects of smoking denicotinized (denic) and average nicotine (avnic) tobacco cigarettes were studied on brain mu opioid receptor binding by positron emission tomography with 11C carfentanil. The results indicated the importance of physiological and psychological effects induced by denic smoking.

Methods

Regional mu opioid binding potential (nondisplaceable binding potential, BPND) was measured in 20 adult male overnight abstinent chronic tobacco smokers. The denic sessions were conducted about 8:00 am followed by avnic sessions about 2 hours later. Venous plasma nicotine levels and scores of craving to smoke were assessed before and after each smoking session. Fagerstrom scores of nicotine dependence were determined. Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation tests were used to examine associations between BPND and other smoking parameters.

Results

Surprisingly, the very low plasma nicotine peak levels after denic smoking (mean ± SD: 3.3 ± 1.8 ng/mL) were significantly correlated with BPND after denic and avnic smoking. Equally surprising no association was found between nicotine levels after avnic smoking and BPND. Delta craving scores and Fagerstrom scores were correlated with both BPND after denic and avnic in several brain regions.

Conclusions

Very small amounts of nicotine, psychological and behavioral effects of denic smoking appear to have important actions on the endogenous mu opioid system.

Implications

Associations between very low venous plasma nicotine levels after denic smoking and regional brain mu opioid receptor availability are a surprising “placebo” effect. Delta craving and Fagerstrom scores were correlated with BPND in several brain regions including amygdala, hippocampus, insula, nucleus accumbens, putamen, and ventral striatum. This study is limited by modest Power (mean 1 − β = 0.6) for all correlation analyses.

Introduction

Several research groups have reported very discrepant results on the effects of tobacco smoking and release of endogenous brain opioids. Scott et al.1 found that mu opioid receptor availability was decreased after denicotinized (denic) smoking compared to that of nonsmoker controls. Subsequently, Domino et al.2 found that average nicotine (avnic) smoking induced mu opioid activation and deactivation in several brain areas of the drug reward circuit. Nuechterlein et al.3 found that denic smoking activates mu opioid release in the thalamus and nucleus accumbens. About 2 hours after denic smoking, avnic smoking produced no further mu opioid release. Both Ray et al.4 and Kuwabara et al.5 found mostly no change in the mu opioid system after different denic and moderate (nic) tobacco cigarette smoking.

The present study is a new analysis of previously collected data to examine the hypothesis that denic smoking alters mu opioid receptor availability and is associated with smoking parameters. It is well known that the mu opioid system is very susceptible to placebo effects. A placebo is inert pharmacologically but produces significant psychological pleasing effects. Placebo-induced stimulation of endogenous opioid neurotransmission has been reported in regions implicated in reward responses, motivated behavior, pain, and affective regulation.6–8 Therefore, not only pharmacological effects of nicotine, but also behavioral and psychological effects of inhaling smoke, and placebo effects of denic smoking are involved.

Methods

Study Design

Twenty male healthy chronic tobacco smokers aged 20–35 (mean ± SD: 26.5 ± 5.1 years old) were studied. They were volunteers recruited from advertisement. The participants smoked 15–40 cigarettes per day for at least 1 year. They were involved in three previous studies.2,3,9 All subjects were right handed. The subjects had no medical and clinical history or current symptoms of physical illness. Also the Structured Interview for DSM-IV, nonpatient version (SCID-IV NP)10 was used to verify no current or past psychiatric conditions. All participants had a negative urine toxicology test before the PET scans. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. This study included only men to avoid menstrual cycle effects in women. The present study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subject Research and the Radioactive Drug Research Committees at the University of Michigan.

All subjects were abstinent from tobacco smoking overnight (for 8–12 h) before the positron emission tomography (PET) scans. A carbon monoxide detector (Vitalograph Breath CO Model BC1349, Vitalograph, Inc., Lenexa, KS) was used to verify their smoking abstinence, not their smoking status, with a requirement of CO levels that is less than 10 ppm before scanning. The two PET scans with 11C carfentanil (CFN) and 11C raclopride were performed in a counterbalanced study design with denic smoking about 8:00 am followed by avnic tobacco smoking about 10:00 am on separate 2 days. Both denic and avnic cigarettes were obtained from Philip Morris Research Center. Unfortunately, such research cigarettes are no longer available. The cigarettes included genetically modified tobacco plants that differ primarily in the nicotine content only.

Subjects lied down in a PET scanner (Siemens HR+ scanner) with light head restraint. The CFN was injected intravenously as a bolus plus infusion during the scan. Either denic or avnic smoke was inhaled 43 and 53 minutes after the tracer injection. Denic cigarettes contained 0.08 mg nicotine and 9.1 mg tar. Avnic cigarettes contained 1.01 mg nicotine and 9.5 mg tar. Tobacco smoke was inhaled through a one-way air flow system. Detailed PET scanning protocol, image and data acquisition, data analyses were similar to what was reported previously.11 This manuscript presents new correlation analyses of data that were obtained from previous PET scan studies involving the same participants.2,3,9 The brain regions and Talairach atlas coordinates were the right ventral striatum (vStr; 16, 3, −10), left insula (Ins; −42, 10, −12), right hippocampus (Hippo; 18, −6, −14) and left cerebellum (Cbl; −10, −88, −34), left amygdala (Amyg; −20, 0, −22), left putamen (Put; −22, 10, −6), and left nucleus accumbens (NAcc; −10, 12, −8).

Craving, Fagerstrom Score and Plasma Nicotine Levels

Craving for tobacco smoking was measured clinically by self-reports from 1 to 10 (highest craving = 10) of visual analog scale (VAS). On the VAS, subjects were asked how they felt at the time in regard to being relaxed, nervous, alert, and craving for a cigarette before and after either denic or avnic smoking. Scores of the Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence from 0 to 10 (most dependent = 10) were also determined on the day of scanning. Venous blood samples (10 mL) were drawn from each subject to determine nicotine levels. Nicotine levels were examined before and after smoking at about 49, 59, 65, 75, and 95 minutes after CFN injection. Plasma nicotine levels were determined by MEDTOX Laboratories, Inc. (St. Paul, MN) using Liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS-MS).

Statistical Analyses

Calculated BPND for mu opioid receptors were determined as previously reported.2 The present new data examined the relationships between BPND values and plasma nicotine levels, craving, and Fagerstrom scores by correlation analyses. All data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism, RRID:SCR_002798 version 7.00. In the present study, the power analyses were performed with G*Power, RRID:SCR_013726 version 3.1.9.2.12 The p values less than .05 was considered as significant.

Results

CFN BPND and Venous Plasma Nicotine Levels

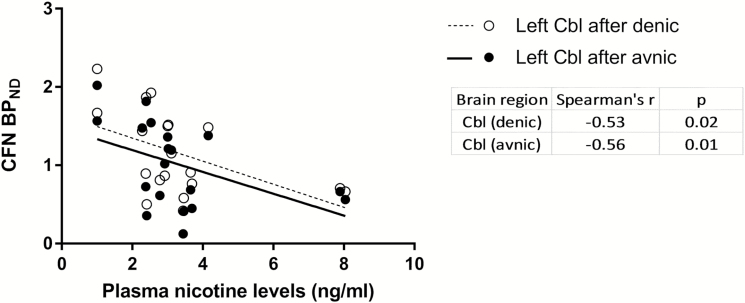

Nicotine levels before (baseline; mean ± SD: 1.67 ± 1.7 ng/mL) and after (peak; mean ± SD: 3.3 ± 1.8 ng/mL) denic smoking were compared with BPND after denic smoking (N = 20 for baseline and N = 19 for peak data). Baseline nicotine levels were not associated with BPND, but surprisingly such low peak nicotine levels after denic smoking were significantly negatively correlated with BPND after denic smoking in the left Cbl (Spearman’s r = −0.53, p = .02; Figure 1). Also peak nicotine levels after denic smoking was significantly negatively associated with BPND after avnic smoking in the left Cbl (Spearman’s r = −0.56, p = .01; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relationship of peak nicotine levels after denic and CFN BPND after either denic (○) or avnic (●) smoking in whole subjects (N = 19).

Nicotine levels before (mean ± SD: 1.9 ± 1.5 ng/mL) and after (mean ± SD: 17.2 ± 8.4 ng/mL) avnic smoking were compared with BPND after avnic smoking (N = 19 for both baseline and peak data). Again surprisingly both baseline and peak nicotine levels were not associated with BPND.

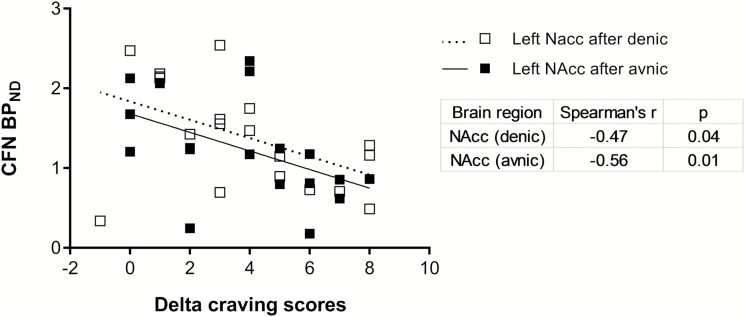

CFN BPND and Craving Scores

Craving scores after either denic or avnic smoking were compared with BPND after either denic or avnic smoking. Surprisingly, craving scores after either denic or avnic smoking were not correlated with BPND after smoking. However, the delta of craving scores (before minus after smoking) had significant associations with BPND. The delta craving score of denic smoking (mean ± SD: 6.4 ± 2.3) was significantly negatively correlated with BPND in left NAcc (Spearman’s r = −0.47, p = .04; Figure 2) after denic smoking (N = 19). The delta craving score of avnic smoking (mean ± SD: 5.4 ± 2.3) was also significantly negatively correlated with BPND in right Hippo (Spearman’s r = −0.46, p = .05) and positively associated with BPND in left NAcc (Spearman’s r = −.56, p = .01; Figure 2) after avnic smoking (N = 19).

Figure 2.

Relationship of CFN BPND after either denic (□) or avnic (■) smoking and delta craving scores (before minus after denic or avnic smoking) in whole subjects (N = 19).

CFN BPND and Fagerstrom Scores

Fagerstrom scores (mean ± SD: 5.2 ± 1.9) were significantly negatively associated with BPND in left Ins (Spearman’s r = −0.82, p < .001), right Hippo (Spearman’s r = −0.59, p = .02), right vStr (Spearman’s r = −0.55, p = .03), left Amyg (Spearman’s r = −.62, p = .01) and left Put (Spearman’s r = −0.55, p = .03) after denic, and BPND in left Ins (Spearman’s r = −0.57, p = .02) and right Hippo (Spearman’s r = −0.53, p = .04) after avnic smoking. In all regions, N = 16.

Power Analysis

Power analyses (post hoc) were conducted for all associations. Power was calculated with sample size, correlation coefficient, and p value for each association analysis. Mean power (1 − β) was 0.6 which had modest validity.

Discussion

One important finding in the present study is that very low plasma nicotine levels after denic smoking were associated with brain mu opioid receptor availability in overnight abstinent tobacco smokers. It has been reported a plasma nicotine boost of 10 ng/mL is needed to causes EEG changes13 and control tobacco smoking intake.14 However, in spite of the very low nicotine levels, associations between BPND after denic and even after avnic smoking were found in this study in the left cerebellum. The cerebellum has been reported to be involved in core drug dependence mechanisms through structural and functional alterations by nicotine.15

The psychological and behavioral effects of denic have been demonstrated. The contribution of sensory,16 process of smoking17 and non-nicotine component of cigarette smoke18 has potent reinforcing effects. Smokers prefer denic smoking over intravenous nicotine administration.18,19 The non-nicotine components of cigarette smoke significantly affect withdrawal symptoms and cerebral blood flow in frontal, parietal, occipital, temporal, and cerebellar cortices.20 Denic smoking has less pronounced effects to raise plasma nicotine levels,8 but reduces craving as well as avnic smoking.19,21

Plasma nicotine levels after smoking vary widely due to the nicotine content in a cigarette. One brand of avnic cigarette has almost 170% more nicotine compared to others (Table 1). Furthermore the smoking procedures, especially the number of puffs, period of exposure to tobacco smoke, and number of cigarettes were greatly different among the studies. In this study, the denic smoking was performed through a one-way air flow system with 0.08 mg of nicotine content cigarette smoke that is the same method as Nuechterlein et al.3 They did not find any associations between the changes in plasma nicotine levels and BPND after denic smoking. The difference between their and our study is that they subtracted the late portion of each scan (denic or avnic) from its earlier baseline but there was no baseline correction in the present study. Nuechterleins’ results suggest that denic smoking induced prolonged mu opioid activation and no additional activation after avnic smoking. From the point of view of denic smoking effects, their findings are similar to ours results even though different analytical methods were used. Therefore, the denic and avnic smoking sessions should be done in the future on separate days as per Ray et al.4 and Kuwabara et al.5 Also there is another reason why the denic and avnic sessions should be separated at least one day. Denic smoke inhalation was considered as the first cigarette of the day in the present study. Most smokers report that the first cigarette of the day is the strongest.22 The reason is that nicotine levels are at their lowest due to the rapid metabolism into cotinine overnight.23 Furthermore, the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) have recovered from desensitization and the first cigarette of the day tends to have most efficient activation on nAChRs.24 Therefore the first cigarette of the day, denic smoking may have greater effects on opioid activation compared to the second cigarette, avnic smoking in this study. However, the denic cigarette was only administered as the first cigarette of the day and no denic smoking effects data subsequent to the first cigarette of the day is available. Further research is needed to determine the effects of the first cigarette of the day.

Table 1.

Study Design Comparisons

| Authors | Scott et al.1 | Ray et al.4 | Kuwabara et al.5 | Domino et al.2 (2015) | Nuechterlein et al.3 | This study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smokers | 6 males | 6 females, 16 males | 2 females, 8 males | 20 males | 24 males | 20 males |

| Nonsmokers | 6 males | 7 females, 13 males | 4 females, 6 males | None | 22 males | None |

| Abstinence duration | ~12 h | 14 h | Not specified | ~8–12 h | 8–12 h | ~8–12 h |

| Administration | 10 puffs every 30 s per cigarette with 2 cigarettes | 6 puffs separated by 30 s with 1 cigarette | 8 puffs over 10 min with 1 cigarette | Smoke inhaling from bottle for 5 min, 2 cigarettes | Smoke inhaling from bottle for 5 min, 2 cigarettes | Smoke inhaling from bottle for 5 min, 2 cigarettes |

| Nicotine in denic cigarette | 0.08 mg | 0.05 mg | <0.05 mg | 0.08 mg | 0.08 mg | 0.08 mg |

| Nicotine in avnic cigarette | 1.01 mg | 0.6 mg | 0.6 mg | 1.01 mg | 1.01 mg | 1.01 mg |

| Tar in cigarette | 9.1 mg (denic), 9.5 mg (avnic) | 10 mg | 10 mg | 9.1 mg (denic), 9.5 mg (avnic) | 9.1 mg (denic), 9.5 mg (avnic) | 9.1 mg (denic), 9.5 mg (avnic) |

| Cigarette source | Philip Morris Research Center | Quest research cigarettes from Vector Tobacco | Quest 1 (avnic) and Quest 3 (placebo) | Philip Morris Research Center | Philip Morris Research Center | Philip Morris Research Center |

| Peak nicotine blood levels after avnic | 17.8 ± 3.7 ng/mL | Not measured | ~7 ng/mL | >10 ng/mL | ~16 ng/mL | 17.2 ng/mL |

| Peak nicotine blood levels after denic | 4.2 ± 0.7 ng/mL | Not measured | <1 ng/mL | No data | ~3 ng/mL | 3.3 ng/mL |

| Smoking sessions | Denic followed by avnic in the same morning | In separate days | In separate days | Denic followed by avnic in the same morning | Denic followed by avnic in the same morning | Denic followed by avnic in the same morning |

| Smoking effects | Endogenous opioids release: denic < avnic | No change between denic and avnic | No change between denic and avnic | Endogenous opioids release: increased and decreased by avnic | Endogenous opioids release: denic > avnic | Endogenous opioids release: increased and decreased by avnic |

| Baseline CFN BPND: smokers < nonsmoker | Baseline CFN BPND: smokers < nonsmoker |

Associations between craving scores and BPND were determined. As expected the changes in craving scores (before minus after smoking) were significantly negatively associated with BPND after both denic and avnic smoking in similar brain regions. Only positive association was found in NAcc after avnic smoking. The hippocampus contributes to contextual evoked craving25 and drug-seeking behavior.26 Reduced mu opioid receptor expression in NAcc by chronic nicotine contributed to development of nicotine tolerance.27 The results suggest that denic and avnic smoking had similar psychological effects on mu opioid system in contrast to plasma nicotine levels. It would be interesting to determine the durations of denic and avnic smoking effects and compare with the half-life of nicotine (~2 h).28

Fagerstrom scores were negatively associated with CFN BPND after denic and avnic in several brain regions. These results are consistent with the previous reports by Kuwabara et al.5 and Nuechterlein et al.3 that smokers with higher Fagerstrom scores had lower mu opioid receptor availability. The effects of chronic exposure to nicotine are controversial in animal models. Up-regulation,29 down-regulation,27,30 and no change31 of mu opioid receptor expression have been reported. Differences in nicotine administration pathway, duration, doses, and animal species may contribute to the contradictory results.

Larson et al.32 summarized the five reasons why people continue to smoke tobacco as follows: (1) Pharmacological effects of nicotine, (2) Effects of other constituents of tobacco smoke, (3) Psychological and psychoanalytic effects, (4) Cultural and social effects, and (5) Economic effects. The comprehensive volumes of Tobacco Experimental and Clinical Studies32 and Supplemental Study I33 provided a very firm scientific foundation for the world of literature on tobacco as of those dates. Since then all of us as researchers simply are providing additional pharmacological, physiological, and psychological, etc. reasons for smoking.

Funding

This work was supported by the Smoking Research Foundation in Japan; University of Michigan (Department of Pharmacology Psychopharmacology Research Fund C361024 and Education and Research Development Fund 276157) and the National Institutes of Health Grants (R01 DA 016423) to EFD.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. Scott DJ, Domino EF, Heitzeg MM, et al. Smoking modulation of mu-opioid and dopamine D2 receptor-mediated neurotransmission in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007; 32(2): 450–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Domino EF, Hirasawa-Fujita M, Ni L, Guthrie SK, Zubieta JK. Regional brain [(11)C]carfentanil binding following tobacco smoking. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2015;59:100–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nuechterlein EB, Ni L, Domino EF, Zubieta JK. Nicotine-specific and non-specific effects of cigarette smoking on endogenous opioid mechanisms. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;69:69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ray R, Ruparel K, Newberg A, et al. Human mu opioid receptor (OPRM1 A118G) polymorphism is associated with brain mu-opioid receptor binding potential in smokers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(22):9268–9273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kuwabara H, Heishman SJ, Brasic JR, et al. Mu opioid receptor binding correlates with nicotine dependence and reward in smokers. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e113694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peciña M, Love T, Stohler CS, Goldman D, Zubieta JK. Effects of the mu opioid receptor polymorphism (OPRM1 A118G) on pain regulation, placebo effects and associated personality trait measures. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(4):957–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scott DJ, Stohler CS, Egnatuk CM, Wang H, Koeppe RA, Zubieta JK. Placebo and nocebo effects are defined by opposite opioid and dopaminergic responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(2):220–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zubieta JK, Bueller JA, Jackson LR, et al. Placebo effects mediated by endogenous opioid activity on mu-opioid receptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25(34):7754–7762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Domino E, Ni L, Hirasawa-Fujita M. Mass dose effects of carfentanil and raclopride on venous plasma cortisol and prolactin after tobacco smoking during PET Scanning. Int Arch Clin Pharmacol. 2016;2(1):005. [Google Scholar]

- 10. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, and Williams JBW.. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP). New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Domino EF, Evans CL, Ni L, Guthrie SK, Koeppe RA, Zubieta JK. Tobacco smoking produces greater striatal dopamine release in G-allele carriers with mu opioid receptor A118G polymorphism. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;38(2):236–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kadoya C, Domino EF, Matsuoka S. Relationship of electroencephalographic and cardiovascular changes to plasma nicotine levels in tobacco smokers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55(4):370–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Russell MAH. Nicotine intake and its regulation by smokers. In: Martin WR, Van Loon GR, Iwamoto ET, Davis L, eds. Tobacco Smoking and Nicotine: A Neurobiological Approach. Boston, MA: Springer US; 1987:25–50. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kühn S, Romanowski A, Schilling C, et al. Brain grey matter deficits in smokers: focus on the cerebellum. Brain Struct Funct. 2012;217(2) :517–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Butschky MF, Bailey D, Henningfield JE, Pickworth WB. Smoking without nicotine delivery decreases withdrawal in 12-hour abstinent smokers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1995;50(1):91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pickworth WB, Fant RV, Nelson RA, Rohrer MS, Henningfield JE. Pharmacodynamic effects of new de-nicotinized cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(4):357–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rose JE, Salley A, Behm FM, Bates JE, Westman EC. Reinforcing effects of nicotine and non-nicotine components of cigarette smoke. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2010;210(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barrett SP. The effects of nicotine, denicotinized tobacco, and nicotine-containing tobacco on cigarette craving, withdrawal, and self-administration in male and female smokers. Behav Pharmacol. 2010;21(2):144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Addicott MA, Froeliger B, Kozink RV, et al. Nicotine and non-nicotine smoking factors differentially modulate craving, withdrawal and cerebral blood flow as measured with arterial spin labeling. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(12):2750–2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brody AL, Mandelkern MA, Olmstead RE, et al. Ventral striatal dopamine release in response to smoking a regular vs a denicotinized cigarette. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(2):282–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. DiFranza JR, Wellman RJ. A sensitization-homeostasis model of nicotine craving, withdrawal, and tolerance: integrating the clinical and basic science literature. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(1):9–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Benowitz NL, Jacob P III. Nicotine and cotinine elimination pharmacokinetics in smokers and nonsmokers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1993;53(3):316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Valayil J. Cigarette smoking and nicotine addiction. Austin J Lung Cancer Res. 2016;1(1):1002. [Google Scholar]

- 25. McClernon FJ, Conklin CA, Kozink RV, et al. Hippocampal and insular response to smoking-related environments: neuroimaging evidence for drug-context effects in nicotine dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(3):877–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gould TJ. Nicotine and hippocampus-dependent learning: implications for addiction. Mol Neurobiol. 2006;34(2):93–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Galeote L, Kieffer BL, Maldonado R, Berrendero F. Mu-opioid receptors are involved in the tolerance to nicotine antinociception. J Neurochem. 2006;97(2):416–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Benowitz NL. Nicotine and smokeless tobacco. CA Cancer J Clin. 1988;38(4):244–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wewers ME, Dhatt RK, Snively TA, Tejwani GA. The effect of chronic administration of nicotine on antinociception, opioid receptor binding and met-enkelphalin levels in rats. Brain Res. 1999;822(1–2):107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marco EM, Granstrem O, Moreno E, et al. Subchronic nicotine exposure in adolescence induces long-term effects on hippocampal and striatal cannabinoid-CB1 and mu-opioid receptors in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;557(1):37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vihavainen T, Piltonen M, Tuominen RK, Korpi ER, Ahtee L. Morphine–nicotine interaction in conditioned place preference in mice after chronic nicotine exposure. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;587(1–3):169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Larson PS, Haag HB, Silvette H.. Tobacco: Experimental and Clinical Studies; A Comprehensive Account of the World Literature. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Larson PS, Silvette H.. Tobacco: Experimental and Clinical Studies. Supplement. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1968. [Google Scholar]