Abstract

This article examines the experience of a frontier-based community health center when it utilized the Tool for Health and Resilience in Vulnerable Environments (THRIVE) for assessing social determinants of health with a local health consortium. Community members (N = 357) rated safety, jobs, housing, and education among the top health issues. Community leaders integrated these health priorities in a countywide strategic planning process. This example of a frontier county in New Mexico demonstrates the critical role that community health centers play when engaging with local residents to assess community health needs for strategic planning and policy development.

Keywords: community health center, frontier, policy, social determinants of health, THRIVE

THE ROLE OF community health centers (CHCs) as conveners for mobilizing community action to address the social determinants of health in the United States dates back to the 1960s’ War on Poverty. Similar to one of the first health centers initiated in the Mississippi Delta (Geiger, 2005), today’s rural and frontier health centers are in a position to engage with community leaders to bridge preventive and primary care with basic social needs and support services, such as food, housing, and clean water (Lefkowitz, 2005). The empowerment of people to exert control over their own health needs through multisector community development lies at the crux of the approach used successfully by many CHCs to address social determinants of health (Goldfield, 2009; Hunt, 2005).

More recently, landmark initiatives such as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Commission to Address the Social Determinants of Health (Braveman et al., 2011), the national call to include social factors in the Healthy People 2020 Initiative (Koh & Tavenner, 2012), and the National Prevention Strategy that was developed in accordance with the Affordable Care Act guidelines (Patient Protection & Affordable Care Act, 2010) have called for a reemergence of integration between primary health care and public health. Furthermore, the Affordable Care Act invests more federal resources into growing the role of CHCs and public hospitals to include conducting periodic community health care needs assessments and devising an implementation strategy to address high-priority health-related community needs (Nielsen, 2010; Patient Protection & Affordable Care Act, 2010). For example, funding through both the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation and the Prevention and Public Health Fund emphasizes improving health and controlling costs through partnerships between health clinics and public health organizations; community benefits regulations have also shifted to allow for investment in broader community health activity and to encourage better alignment between required needs assessments and investment; and investments in Accountable Care Organizations and Health Home demonstration projects are leading to innovative approaches to improve health and to incentivize models other than fee-for-service delivery. This support, taken together with emerging evidence of the effectiveness of strategies focusing on populations, presents opportunities to revisit the role of health centers in society, particularly the ways they can serve as loci for addressing the social determinants of health. Community health centers provide comprehensive care and patient support services, engage in quality care improvements, and are able to transform the delivery system because they operate at the crossroads of medical care and public health (Hawkins & Groves, 2011, p. 95). Some health centers are changing local economies as well as health environments (Hawkins & Groves, 2011; Hunt, 2005). It is estimated that by 2015, health centers will generate $53.9 billion in economic activity, where every $1 million in federal funding yields $1.73 million in return (National Association of Community Health Centers, 2010).

Rural and frontier CHCs can play a critical role in aligning community planning and strategies with primary care goals and policy interventions. Rural and frontier providers have the ability to deliver patient-centered care and services in a coordinated and affordable way (Bolin et al., 2011). In frontier communities in particular, CHCs are typically the sole representative of the health sector in local or regional planning efforts. Community health centers in rural/frontier communities are typically one of the major employers in the region, and providers are known and respected throughout the community. Because providers are respected, play a commanding role, and well aware of the unique circumstances and needs that present themselves in rural and frontier communities, they are uniquely situated to facilitate community assessments and environmental policy change (Kilpatrick, 2009). For example, CHCs play a convening role in working with health extension rural offices and other partners to align community needs with strategic planning in rural areas (Moulton et al., 2007). In New Mexico, health extension offices have been utilized to address community needs and help develop community capacities to effectively address underlying social determinants of disease (Kaufman et al., 2010). In addition, the Community Transformation Grant program administered through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has provided funding for multiple state and local public health departments to work with community coalitions to address social determinants of health impacting smoking, fitness and nutrition, and chronic disease (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). However, very little is documented about the community engagement tools and processes that rural and frontier health centers use to align the social determinants of health with primary care for planning and policy development.

To address this gap, we examine the community Tool for Health and Resilience in Vulnerable Environments (THRIVE) (Davis et al., 2005) experience in a frontier county along the US-Mexico border. This case example illustrates how one CHC took the lead along with a local health coalition to assess the social determinants of health and used the data to inform a strategic action plan and policy goals to improve health conditions.

METHODS

Setting

Hidalgo County is located in southwestern New Mexico and borders Mexico to the south and Arizona to the west. With 4894 residents and a population density of 1 person per square mile, Hidalgo is classified as a frontier county (US Census Bureau, 2012). Fifty-six percent of the county is Latino and one-third of the population speaks Spanish at home (US Census Bureau, 2012). Ranching and mining, the major industries in the area, have been severely impacted by the economic downturn, resulting in an unemployment rate of 8%, pushing 27.8% of the county residents below the poverty line (US Census Bureau, 2012). The frontier setting challenges access to social services and basic needs such as fresh and affordable food, as well as to adequate health care. Many frontier residents live “off the grid,” without access to electricity or hot water, and many must drive up to 2 hours to reach supermarkets, schools, and physicians’ offices (Patrick & Cox, 2013).

Despite these challenges, community-based organizations and residents of this frontier county are actively engaged in community change and serve as valuable assets. The lead organization in this project, Hidalgo Medical Services (HMS), is the only CHC in the county and is actively working to address local health needs and link patients with social services. Hidalgo Medical Services provides comprehensive primary care at 11 locations, including 4 school-based health centers, in both Hidalgo and Grant counties. Hidalgo Medical Services utilizes a mix of pediatric, internal medicine, and family medicine physicians and midlevel clinicians who provide comprehensive primary medical care to patients of all ages. In addition to medical care, HMS also acts as a mediating institution (Lamphere, 1992, p. 4) that promotes community-based partnerships between local residents and external research institutions and links patients with social services through a rigorous Community Health Worker program. The community health workers provide a wide range of services, including eligibility screening and enrollment for HMS’s sliding-fee scale, Medicare, state and federal benefits/assistance programs, community outreach, health education, and patient advocacy. These comprehensive services reflect an expanded ambulatory care model that provides patients both medical and social care, bridging them to supportive community resources (Barr et al., 2003).

The HMS board is composed entirely of patients from the community and serves as a valuable asset in keeping the CHC informed of economic and social issues affecting the residents of the surrounding region. The HMS board of directors encourages HMS to conduct a variety of needs assessments, many of which are required in grant funded work, to guide organizational planning and resource development. Because of limited financial resources and human capital, individuals in rural and frontier areas experience a high level of community interconnectedness between social, health, and economic systems. As various issues arise, it is common for residents and community leaders to convene to discuss local issues and consider solutions. This ability to unify in a geography-dispersed area is one of the greatest assets of the frontier community and was demonstrated in this project.

Tool for Health and Resilience in Vulnerable Environments

The THRIVE was developed by the Prevention Institute and is a framework and tool designed to engage community members in critically thinking about the role the physical, social, and economic environments play in shaping the health and safety of their community and to identify potential solutions (Davis et al., 2005; Prevention Institute, 2013). The THRIVE’s approach is grounded in cultivating the wisdom that exists within communities about what is shaping health and safety and in bringing forward priority strategies to improve community health. The Prevention Institute developed THRIVE as a systematic means to help community members shift from focusing on a discrete health problem to focusing on the factors that underlie the problem (ie, upstream social determinants of health). As illustrated in Table 1, the tool is divided into 3 domains: (1) equitable opportunity, (2) the people, and (3) the place. Each of the 3 domains is subdivided into factors associated with health. Community stakeholders are asked to rate the importance of each factor in an assessment and then to respond to a number of probing questions. The final stage of THRIVE is to engage stakeholders in developing action plans that incorporate policies and social conditions contributing to health inequities (see Supplemental Digital Content, available at http://links.lww.com/JACM/A30).

Table 1.

THRIVE Community Health Factors

| Place |

| What’s Sold and How It’s Promoted |

| Look, Feel, & Safety |

| Parks & Open Space |

| Getting Around |

| Housing |

| Air, Water, and Soil |

| Arts, Culture, and Entertainment |

| Equitable opportunity |

| Racial Justice |

| Jobs and Local Ownership |

| Education |

| People |

| Social Networks and Trust |

| Participation and Willingness to Act for the Common Good |

| Norms/Customs |

The partnership

In 2010, HMS approached the Hidalgo County Health Consortium to form a partnership to conduct a community assessment. The HMS’s commitment to providing medical care and public health services to reduce pervasive health and access disparities is a key motivator for initiating this partnership. The members of the Consortium (representatives from governmental entities, private businesses, schools, the health department, law enforcement, nonprofit groups, and retired public servants) saw the value in the project and agreed to form a partnership. Hidalgo Medical Services then contacted the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center for Health Policy at the University of New Mexico and the Prevention Institute from Oakland, California, to test a community prevention approach that addresses health disparities and focuses on building on the resilience of communities with compromised environments. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center for Health Policy at the University of New Mexico is a national resource for minority health-policy research and gives voice to Hispanics, Native Americans, and other underrepresented groups. The Prevention Institute, a national leader in developing equity-based tools, such as the THRIVE tool, works with and trains local community members in community-based research techniques. Hidalgo Medical Services, as previously indicated, is a nonprofit CHC with 11 community and school-based locations, including 3 in Hidalgo County and 8 in Grant County.

At the onset of the project staff from the University of New Mexico, HMS, and the Prevention Institute discussed their roles and desired project outcomes. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center for Health Policy at the University of New Mexico faculty and a graduate student would provide methodological guidance and assist with data analysis. Staff from the Prevention Institute would lead and facilitate workshops on how to modify and use the THRIVE tool in addition to providing preliminary descriptive analysis of the collected data. Staff from the HMS Center for Health Innovation, a planning and development division within HMS, would recruit community leaders, host and coordinate local activities, oversee implementation of THRIVE, and serve as a local partner to ensure enactment of policy-driven initiatives resulting from the findings.

A 4-step community-driven engagement process

Over the course of 9 months, the partners implemented the following 4 steps to assess the social determinants of health in Hidalgo County and develop strategies for change: (1) formation and training of the leadership team (April 2011); (2) adaptation and implementation of THRIVE for assessment in a frontier setting (May-July 2011); (3) identification of countywide community health priorities (August 2011); and (4) strategic planning, policy development, and dissemination of results and briefs (September-December 2011).

Step 1: Formation and training of the community leadership team

With support from the Hidalgo County Health Consortium, HMS recruited a leadership team to guide the THRIVE effort. Hidalgo Medical Services identified 26 community leaders who had history and knowledge of their community and were engaged in community activism. The HMS staff recruited them via phone calls, e-mail, and personal contact, and invited them to attend a 4-hour training session hosted by HMS and Hidalgo County Health Consortium and facilitated by the Prevention Institute in May 2011.

Thirteen community leaders (n = 13) from various sectors (eg, ranching, education, government, business) who represented various communities throughout the county attended a “Train-the-Trainer” session led by staff from the Prevention Institute. Also joining the leadership team were members of the local health consortium and HMS staff (including community health workers or promotoras de salud).

The training session began with an introduction of THRIVE along with the framework for understanding how factors within the community environment, including social, physical, and economic conditions, affect health and safety. Prevention Institute staff presented the THRIVE tool and its assessment component, and participants were asked to complete a sample of the assessment, which resulted in robust discussion among participants and suggestions to adapt both the instrument and the descriptions of factors to ensure that language, linguistic nuances, and sociocultural context were adequately addressed. Participants were asked to discuss how they would explain the THRIVE tool to community members, including what they hoped to get out of the entire process. Next, participants discussed the process for distributing the THRIVE tool throughout the county, selected key personnel to distribute and return the tool, and coordinated timelines. At the end of the training session, each leadership team member committed to distributing a specific number of assessments in his or her respective communities, ensuring that the 6 major areas of the county would be represented. The goal was to collect a total of 200 completed assessments by July 2011. With logistics settled, the Community Leadership Team began to consider adaptation of THRIVE for the frontier setting.

Step 2: Adaptation and implementation of THRIVE

The THRIVE features community factors (see Table 1) that were determined on the basis of the input of a national expert panel and influenced by the Healthy People 2010 Leading Health Indicators. First piloted in 2004 in New York, New York, Sacramento, California, and Hidalgo County, New Mexico (Prevention Institute, 2004), the tool was subsequently used only nationally in urban settings. Because the tool had insufficient application in frontier settings, the community leadership team felt that it was important to adapt THRIVE to the frontier setting. For example, 1 question asked community members to rank whether they had enough “open space,” a concept that is meaningful in urban areas but is insignificant in rural and frontier settings. Subsequently, the question was removed. In another instance, community members wrestled with how to incorporate immigration and border-patrol staffing issues, a politically charged topic with diverse dialogue and conflicting community perceptions regarding both problems and solutions. To keep the integrity of the THRIVE assessment, HMS and the Prevention Institute decided to add an item in the tool that allowed for open-ended responses by the county residents.

A professional translator translated the adapted paper-based tool from English into Spanish. The HMS policy staff, in partnership with the local health consortium coordinator, engaged with community leaders throughout the county and organized the data collection. The HMS distributed the tool to the leadership team, which then distributed the assessment through various venues including community and church events, health education classes, the senior citizens’ center, food commodities distribution sites, youth center sites, schools, community centers, and other locally significant gathering places. The health consortium coordinator checked in weekly with the leadership team to see how outreach and assessment completion was progressing, to offer technical assistance, and to collect completed assessments. Staff at the HMS scanned the submitted documents for backup purposes and mailed them to the Prevention Institute for analysis. The Prevention Institute then scanned the tools using Remark Office OMR software (Gravic, Inc., Malvern, PA) and ranked the community scores using Microsoft Excel, software chosen because it was commonly available among Hidalgo residents. The Prevention Institute ranked the submissions by priority and returned findings to the local community coalition for discussion and interpretation.

Step 3: Identification of countywide community priorities

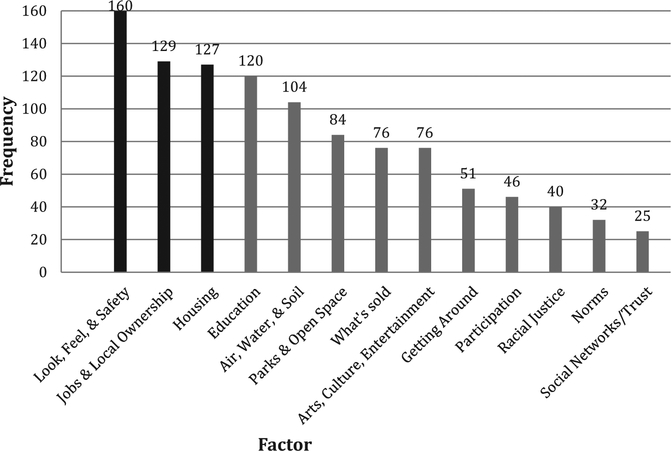

Three hundred fifty-seven assessments were completed by adult residents between the ages of 18 and 65 years from 6 towns geographically dispersed in the county. Hispanic residents comprised from 21.71% to 77.26% from the 6 towns. Only 10 surveys were completed in Spanish since bilingual residents preferred to complete the survey in English. The following 4 items were most commonly reported by the residents of Hidalgo County: (1) Look, Feel, & Safety; (2) Jobs & Local Ownership; (3) Housing; and (4) Education (Figure). Following the survey results, 2 meetings were held with community members to examine and discuss the findings. The factor “Look, Feel & Safety” was identified as the issue of greatest community concern and was discussed at length. Comments focused on concerns about the US Border Patrol’s presence far north of the US-Mexico border, often on private lands, instead of focusing attention directly on the border where residents felt that there was the most need for security. As one resident explained, “We hear from Washington, D.C., that our border is safe, but what we see is different.” Also of concern was the lack of safe opportunities for parent-child engagement, including access to local high school grounds after school hours, excess litter in open spaces, and abandoned buildings and vehicles. “Jobs & Local Ownership” closely followed “Look, Feel, & Safety” as a high-priority issue. Community members pointed out the lack of job opportunities, which were resulting in “many graduates leaving the county to find employment elsewhere.” “Housing,” the third priority identified, resonated in the community meetings. Of particular concern was the lack of local amenities and affordable housing for the influx of border-patrol agents and their families. Exasperated, one individual explained, “It’s difficult; we can get some grants for houses, but it is not enough. It’s difficult to get people to live here! It is not green and there is no life here.” Finally, “Education,” closely ranked in fourth place, was indicated as a priority because of its possible impact on student career development and the creation of a local workforce. As explained by a resident, “A lot of people go back and forth for jobs with the mines, and they live away from home. But it’s like a cycle. No education, no jobs, no housing.”

Figure.

THRIVE factors ranked by frequency of responses from residents.

Step 4: Strategic planning and policy development

Following analysis and prioritization, the findings were presented to community members during 2 separate meetings. To promote attendance, HMS staff and the health council coordinator promoted the events in local newspaper articles and community flyers through e-mail lists and word of mouth. The purpose of the first meeting was to present the data and solicit feedback from local residents in interpreting the results. In a 4-hour session held in Lordsburg, New Mexico, 11 participants were presented with THRIVE findings and supporting statistics on health indicators from Hidalgo County state agencies. During the session, community members provided initial ideas on strategies to address the top factors impacting the county. This initial planning session helped prepare for a 2-hour strategic planning session, held the following day, as the topic for the monthly Hidalgo County Health Consortium meeting.

Twenty community members attended the 2-hour strategic planning session in mid-August in Lordsburg, New Mexico. An overview of the THRIVE process and review of concepts regarding the social determinants of health was presented along with results from the THRIVE assessment and county health-related statistics. Participants were presented with the list of strategies identified at the previous day’s meeting and asked to brain-storm additional strategies, including policy initiatives. Strategies were prioritized and specific action items were identified. Potential resources and lead entities to address each action item were also listed.

Participants identified local strategies for addressing each factor. To address “Look, Feel & Safety,” the primary factor, community residents, and leaders from organizations suggested developing neighborhood watch programs, supporting block parties, leading neighborhood cleanup programs, and improving after-hour lighting and access to the high school track and field. For “Jobs & Local Ownership,” the second priority, local business organizations and the Chamber of Commerce, suggested supporting a “shop local” campaign to promote local businesses, assessing business gaps and recruiting needed businesses, and providing tax incentives for new businesses. For “Housing,” the third priority, participants suggested providing rural housing incentives for housing contractors, including enhanced access to state code enforcers; actively recruiting developers; ensuring adequate infrastructure (eg, water, electric, sewer) to encourage new construction in frontier areas; and joining the Southwest Housing Corporation. Finally, because “Education” was a close fourth, the community suggested improving the communication flow between school board, administration, and parents in the Lordsburg School District (such as coordination of homework assignments) as a way to strengthen local ties to education. Also suggested were various ways to link education with career development opportunities, including finding employment and career opportunity placements (paid or volunteer) and enhancing career exposure for middle-school students (eg, job shadowing). Furthermore, community members suggested actively engaging local employers to learn their current and future employment needs (skills, experience, work ethic, etc) and partnering with universities and tech schools to ensure that the needs are met.

Satisfied that each of the top factors was addressed, the 20 community members reviewed the list and made plans to integrate them into other countrywide strategic planning documents that had little or no community input. Recognizing that the THRIVE process was one of many evaluations currently underway, HMS and the Hidalgo County Health Consortium began to strategically network with local governmental organizations, including county and city officials, to integrate the community input. As a result of this study, a detailed draft of the Hidalgo County Comprehensive Plan Update 2011 (Chaires et al., 2011) was released in October for public review and comment. The plan defined the direction in which the county commissioners guide the county in the upcoming years and established actionable strategies for addressing 6 critical areas: land and water (25 strategies), economic development (29 strategies), housing (12 strategies), transportation (11 strategies), infrastructure/community facilities (14 strategies), and hazards mitigation (7 strategies).

There were clear parallels in the priorities in the County Comprehensive Plan and the THRIVE results, and the THRIVE tool provided reassurance and validity to community efforts. For example, an economic development goal listed in the Comprehensive Plan was to “expand the county-wide workforce training/education program, especially to keep our youth in the area.” Other examples of complementary strategies include shop local campaigns; incentives for new businesses; promotion of local businesses; incentives for housing contractors, including access to state code enforcers and ensured infrastructure; Southwest Housing Corporation membership; and the recruit of developers to the county.

One of the virtues of rural and frontier areas is the cultural practice and regional necessity of gathering stakeholders to manage basic infrastructure needs in the isolated and geographically sparse setting (eg, deliver potable water, manage acreage, corral livestock). The shared value of “we are all in this together” allows local residents to find ways to share and leverage scare resources rather than compete for them. In the 12 months since the THRIVE process began, 2 community initiatives have evolved out of the priorities identified through the THRIVE assessment and planning process. The THRIVE stimulated increased collaboration across county, city, and health care leaders along with increased community engagement. The first initiative is the “Pride Group,” under the leadership of the county manager and commissioners. This group meets monthly and has engaged various youth groups to assist in the beautification and cleanup of targeted city and county areas. The second initiative came from a potential grant opportunity, bringing together the county, local school district, Western New Mexico University, and HMS to increase vocational as well as college opportunities for area youth. Although the grant was not pursued, it opened up communication among these key stakeholders, resulting in the establishment of 3 new vocational certification courses at the local high school for traditional students and adults.

DISCUSSION

After using THRIVE to assess the factors affecting chronic conditions in a frontier county, we believe that there are 3 important findings and 8 lessons that have emerged. First, given the unique challenges to conducting research in frontier settings, adaptation and utilization of available tools can save time and limited resources. Low-cost or free tools such as THRIVE prove to be very useful when adapted to meet local needs and when they are implemented by local organizations. Furthermore, THRIVE provides a structured flow and process that is easily understood by all partners involved and is organized so that community members who are not experienced in research can successfully implement it.

Second, it is important to merge assessment findings and community strategies with other projects already underway in order to leverage the impact on health outcomes. This not only improves the data but also ensures that the findings resonate in and with communities. Furthermore, when attempting to address social determinants of health in rural/frontier communities, it is imperative that health care providers and health planning organizations link with other planning efforts at the county or city (town, village) levels. As was the case in Hidalgo, when city and county planners are informed about the ways which socioeconomic factors influence both the health of the residents and the health of the community, policy changes occur outside of governmental “silos,” and in more comprehensive ways.

Third, it is necessary to engage community members in ongoing, action-oriented dialogue regarding the fears and concerns that affect the daily lives of residents and that have the potential to block advocacy efforts from addressing systems and policy change. For instance, concerns regarding immigration, border violence, or isolation can easily become inflamed public debates that polarize rather than unify residents. Tools such as THRIVE provide a facilitating venue to express social and political community concerns in a constructive manner so that health improvement efforts can continue.

On the basis of our experience using THRIVE as a community engagement assessment and strategic planning process in a rural/frontier setting, we developed a course of guidelines that can facilitate other CHCs in addressing social determinants of health in strategic action planning and policy development (Table 2). The 8 guidelines are to (1) identify local assets; (2) establish trust among key frontier/rural stakeholders; (3) choose realistic and achievable strategies; (4) focus on environments, systems, and policies; (5) collaborate with partners and existing projects; (6) identify community-based entities responsible for leading strategies; (7) engage with members of geographically dispersed communities; and (8) allow for additional time to complete projects.

Table 2.

Action Strategies for Community Planning and Policy Development

| 1. | Identify assets, including local mediating institutions and local cultural practices, to leverage limited resources for extended collaboration and coordination. |

| 2. | Establish trust among key frontier/rural stakeholders to better identify political issues or other factors that may restrain advancement in addressing social determinants of health and related conditions. |

| 3. | Choose 1 to 3 realistic and achievable strategies to focus on and implement. Continue to meet with existing community groups to identify common priorities and strategies to address those priorities. |

| 4. | Focus on local strategies that change environments, systems, and policies to address community health and safety priorities. |

| 5. | Collaborate with partners to address health through existing projects and strategies outside the health arena (such as economic development) rather than creating a separate initiative. |

| 6. | Identify community-based entities responsible for leadership in advancing priority strategies. Establish a clear purpose and goal among all entities and clarify the roles and responsibilities of each community entity in meeting the goal. |

| 7. | Engage community members throughout the planning and implementation process to increase chances of success in creating change and explore unique ways to engage geographically dispersed communities. |

| 8. | Community planning processes are complex and labor-intensive. Plan for adequate time, funding, and a diversity of people with the necessary skills dedicated to the effort. |

It is our hope that these guidelines will assist other CHCs to increase and improve collaboration with local partners in other frontier settings. These actions provide insight on how to assess social determinants of health for program planning and policy development in rural and frontier settings. These actions help rural advocates identify and address social determinants of health collaboratively and directly with new partners. This is a potential challenge in the geographically dispersed setting, but to create a space for real and significant environmental, infrastructural, and systems-level changes, a variety of actors must be “at the table” to discuss local initiatives and to raise community awareness.

CONCLUSION

The New Mexico THRIVE example illustrates the process, outcomes, and successes when CHCs engage with local partners to assess the social determinants of health for strategic action and policy development in frontier areas of the United States. Our experience demonstrates the unique role that CHCs play in linking with hard-to-reach populations and in leading community-wide health improvement strategies. When modified for frontier communities, THRIVE is a useful and productive tool for translating community needs into concrete changes in local policies, programs, and priorities.

Acknowledgements:

This research project was funded by the Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health, National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities to Principle Investigator Cacari Stone under the RWJF Center for Health Policy (Grant Number-3P20MD004996-01S1).

Footnotes

The authors have disclosed that they have no significant relationships with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citation appears in the printed text and is provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.ambulatorycaremanagement.com).

Human Participant Protection: The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (HRRC#10–634).

REFERENCES

- Barr V, Robinson S, Narin-Link B, Underhill L, Dotts A, & Ravendale D (2003). The expanded chronic care model: an integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the chronic care model. Hospital Quarterly, 7(1), 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolin JN, Gamm L, Vest JR, Edwardson N, & Miller TR (2011). Patient-centered medical homes: will health care reform provide new options for rural communities and providers? Family and Community Health, 34(2), 93–101. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e31820e0d78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P, Egerter S, & Williams DR (2011). The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annual Review of Public Health, 32, 381–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-1012180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Community Transformation Grants (CTG). Retrieved April 23, 2013, from http://www.cdc.gov/communitytransformation/index.htm

- Chaires Richard, Kerr Ed, Shannon Darr, Salazar John, Acosta Carmen, Green Tisha, … Salazar John. (2011). Hidalgo County comprehensive plan update 2011. Hidalgo, New Mexico: Hidalgo County Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Davis R, Cook D, & Cohen L (2005). A community resilience approach to reducing ethnic and racial disparities in health. American Journal of Public Health, 95(12), 2168–2173. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2004.050146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger HJ (2005). The first community health centers: a model of enduring value. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 28(4), 313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfield N (2009). Community participation and (not or) individual empowerment: The key to improving health outcomes and stabilizing healthcare costs. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 32(4), 271–274. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e3181ba6ef4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins D, & Groves D (2011). The future role of community health centers in a changing health care landscape. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 34(1), 90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt JW Jr. (2005). Community health centers’ impact on the political and economic environment: the Massachusetts example. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 28(4), 340–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman A, Powell W, Alfero C, Pacheco M, Silverblatt H, Anastasoff J, … Scott A (2010). Health extension in New Mexico: An academic health center and the social determinants of disease. Annals of Family Medicine, 8(1), 73–81. doi: 10.1370/afm.1077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick S (2009). Multi-level rural community engagement in health. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 17(1), 39–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2008.01035.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh HK, & Tavenner M (2012). Connecting care through the clinic and community for a healthier America. American Journal of Public Health, 102(Suppl. 3), S305–S307. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2012.300760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamphere L (Ed.). (1992). Structuring diversity: Ethnographic perspectives on the new immigration. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz B (2005). The health center story: forty years of commitment. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 28(4), 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulton PL, Miller ME, Offutt SM, & Gibbens BP (2007). Identifying rural health care needs using community conversations. The Journal of Rural Health, 23(1), 92–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00074.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Community Health Centers, Capital Link. (2010). Turning vision into reality: Community health centers lead the primary care revolution. Retrieved February 13, 2013, from http://www.nachc.com/

- Nielsen Site Reports. (2010). Claritas Site Reports Basic Demographics Report Bundle: Hidalgo County. Retrieved May 3, 2013, from http://www.claritas.com/on.

- Patient Protection & Affordable Care Act, Pub. L. No. 111–148, 42 USC 289d, x 5313 (2010).

- Patrick M, & Cox B (2013). Hidalgo County food security study: Final report. Lordsburg, New Mexico: Hidalgo Medical Services. [Google Scholar]

- Prevention Institute. (2004). Final project report: A community approach to address health disparities: Toolkit for health & resilience in vulnerable environments (p. 19). Oakland, CA: Prevention Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Prevention Institute. (2013). THRIVE: Tool for health and resilience in vulnerable environments. Retrieved February 8, 2013, from http://thrive.preventioninstitute.org/thrive/factor_tools.php?

- US Census Bureau. (2012). State & County QuickFacts: New Mexico. Retrieved February 8, 2013, from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/35/35017.html