Abstract

With the aim of describing the human microbiota by the means of culture methods, culturomics was developed in order to target previously un‐isolated bacterial species and describe it via the taxono‐genomics approach. While performing a descriptive study of the human gut microbiota of the pygmy people, strain Marseille‐P4678T has been isolated from a stool sample of a healthy 39‐year‐old pygmy male. Cells of this strain were Gram‐positive cocci, spore‐forming, non‐motile, catalase‐positive and oxidase‐negative, and grow optimally at 37°C under anaerobic conditions. Its 16S rRNA gene sequence exhibited 89.69% of sequence similarity with Parvimonas micra strain 3119BT (NR 036934.1), its phylogenetically closest species with standing in nomenclature. The genome of strain Marseille‐P4678T is 2,083,161 long with 28.26 mol% of G+C content. Based on its phenotypic, biochemical, genotypic and proteomic profile, this bacterium was classified as a new bacterial genus and species Miniphocibacter massiliensis gen. nov., sp. nov. with the type strain Marseille‐P4678T.

Keywords: culturomics, gut microbiota, Miniphocibacter massiliensis, new species, pygmy, taxono‐genomics

1. INTRODUCTION

Ever since it has been proved to play a role in the human health and diseases, the human gut microbiota took more attention and descriptive studies have been exhaustively done toward unveiling its microbial content (Clemente, Ursell, Parfrey, & Knight, 2012). For example, the gut microbiota composition has been shown to play a role in malnutrition, Crohn's disease, inflammatory bowel diseases, etc. and thus became a therapeutic target in several cases (Million et al., 2016; Rigottier‐Gois, 2013; Tidjani Alou et al., 2017; Vétizou et al., 2015; Würdemann et al., 2009). Yet, with the expansion of culture‐independent techniques, scientists’ thought that the human microbiota could be more efficiently described with no need of re‐adapting culture approaches. Indeed, with metagenomics, loads of data have been reported out of which some were significant and others were not since several drawbacks can be faced throughout the process such as the depth bias, presence of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) inability to identify certain pathogenic species or distinguish dead from living bacteria, and thus rendering a part of the human gut population neglected, not identified or described (Greub, 2012). Thus, culturomics was developed, based on sophisticated culture methods, targeting previously uncultured bacterial species (Lagier et al., 2012). The latter was able to report a significant number of nonhuman and new bacterial species along with correlating its sequences to different OTUs (Lagier et al., 2016). New bacterial species are described with the means of taxono‐genomics approach, which relies on characterizing the understudied organism at the phenotypic, biochemical, proteomic and genomic level in order to confirm the novelty of the understudied organism whenever full genomes are available for comparison at wider range (Fournier & Drancourt, 2015; Lagier et al., 2016). Knowing that 1g of human stool might contain up to 1012 bacterial cells and that only around 2,000 species were isolated by culture, motivate us to purse our efforts in describing the human gut microbiota by culturomics. (Hugon et al., 2015; Raoult & Henrissat, 2014). Herein, we describe a new bacterial species, Miniphocibacter massiliensis gen.nov, sp. nov. strain Marseille‐P4678T using the taxono‐genomics approach. This bacterium was isolated from the stool samples of a healthy pygmy male.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Strain Marseille‐P4678T isolation and identification

Shipment of the stool samples was done using a special medium C‐Top Ae‐Ana (Culture Top, Marseille, France) and stored at our laboratory at ‐80°C for further analysis. To assess bacterial content using culturomics, the stool sample was diluted with phosphate buffer saline and incubated in an anaerobic culture bottles (BD BACTEC®, Plus Anaerobic/F Media, Le Pont de Claix, France) supplemented with 5% (V/V) sheep blood and 5% (V/V) sterile‐filtered cow rumen at 37°C. Subculturing assays were done on 5% sheep blood–enriched Columbia agar (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) for bacterial colonies isolation. Isolated colonies were identified using MALDI‐TOF MS (matrix‐assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry; Microflex Lt [Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany]) as previously described (Lagier et al., 2012; Seng et al., 2010). Whenever MALDI‐TOF MS fails to identify the tested organism, 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed as formerly done for further phylogenetic analysis (Drancourt, Berger, & Raoult, 2004). CodonCode Aligner tool (http://www.codoncode.com) served for sequence optimization and alignment. Retrieved sequences were blasted in NCBI nucleotide database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.gate1.inist.fr/Blast.cgi), and species or genera delimitation thresholds were adapted according to Kim, Oh, Park, and Chun (2014) norms. EMBL‐EBI (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/services) and UMRS (http://www.mediterranee infection.com/article.php?laref=256&titre=urms‐database) databases were used for 16S rRNA gene sequence and mass spectrum deposition, respectively.

2.2. Optimal growth conditions

Several growth attempts were done with various culture conditions in order to determine the optimal growth of strain Marseille‐P4678T. The following criteria were taken into consideration: pH (6, 6.5, 7, and 8.5), temperatures (25, 37, 45, and 55°C), NaCl concentrations (0, 5, 10, 50, 75, and 100 g/L), and atmosphere (anaerobic (GENbag anaer, bioMérieux, France), microaerophilic (GENbag Microaer, bioMérieux, France), and aerobic).

2.3. Biochemical, antibiotic resistance, and phenotypic characteristics of strain Marseille‐P4678T

To biochemically describe strain Marseille‐P4678T, API strips (ZYM, 20A and 50CH; bioMérieux) were used according to manufacturer's protocol. Sporulation ability was tested by performing a culture assay of a previously heat‐shocked bacterial suspension (80°C; 20 min). Gram staining and motility were evaluated using a DM1000 photonic microscope (Leica Microsystems, Nanterre, France) at 100 × oil immersion lens, and cell morphology was determined using an electron microscope as formerly done (Bilen et al., 2018).

Additionally, to test the antibiotic resistance characteristics of strain Marseille‐P4678T, several E‐strips were used: voriconazole, vancomycin, tobramycin, teicoplanin, rifampicin, minocycline, metronidazole, kanamycin, imipenem, fosfomycin, fluconazole, erythromycin, ertapenem, daptomycin, colistin, ceftriaxone, benzylpenicillin, amoxycillin, amikacin (bioMérieux, France).

GC/MS and cellular fatty acid analysis of strain Marseille‐P4678T were carried out using 20 mg (dry weight) of bacterial biomass per tube as previously done (Dione et al., 2016). SQ8s mass spectrometer (Perkin Elmer, Courtaboeuf, France) was used for short‐chain fatty acids measurements along with Clarus 500 chromatography (Zhao, Nyman, & Jönsson, 2006). Isobutyric, propionic, butyric, isovaleric, caproic, valeric, enanthic, and isocaproic (Sigma‐Aldrich; Lyon, France) were used. Calibrations were done using acidified water (pH 2–3 with HCl 37%), and SCFA were examined using three samples and three controls. Centrifugation of the culture medium was done for 5 min at 16,000 × g in order to get rid of the bacteria and its debris. Collected supernatant's pH was fixed between two and three and spiked with 2‐ethylbutyric acid as the internal standard (1 mm) (IS) (Sigma‐Aldrich). Centrifugation was repeated prior sample's injection. Direct injection (0.5 μl) of the aqueous solution was done in a splitless liner heated at 200°C. Injection performance was decreased with 10 syringe washes in methanol:water (50:50 v/v). Using a linear temperature gradient from 100 to 200°C at 8°C/min, compounds’ separation was done on an Elite‐FFAP column (30 m, 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 mm film thickness). Helium flowing was used as carrier gas at 1 ml/min. MS inlet line and electron ionization source were set at 200°C. After 4.5 min, selected ion recording (SIR) was done with the following masses: 88 m/z (2‐ethylbutyric acid, IS), 43 m/z (isobutyric acid), 60 m/z (acetic, butyric, valeric, isovaleric, caproic, and enanthic acid), and 74 m/z (propanoic and isocaproic acid). All data were collected and processed using Turbomass 6.1 (Perkin Elmer, Courtaboeuf, France). The peak areas of the associated SIR chromatograms were used for quadratic internal calibration calculations. All coefficients of determination were more than 0.999. Back‐calculated standards and calculated quality controls (0.5 and 5 mm) represented accuracy with less than 15% deviation. Blank results of the control were subtracted from while analyzing samples.

2.4. DNA extraction and genome sequencing

Strain Marseille‐P4678T genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted by first performing acid glass beads wash (G4649‐500 g Sigma) using a FastPrep BIO 101 instrument (Qbiogene, Strasbourg, France) at maximum speed (6.5 m/s) for 90s. Two hours later, a lysozyme incubation at 37°C was done prior to DNA extraction on the EZ1 biorobot (Qiagen) with EZ1 DNA tissues kit. 50 μl gDNA of 15.8 ng/μl concentration was eluted. Concentration was measured using a Qubit assay with the high sensitivity kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). MiSeq technology (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) was used with the mate‐pair strategy for gDNA sequencing along with 11 other projects and barcoded with the with the Nextera Mate Pair sample prep kit (Illumina). 1.5 μg of gDNA was used for library preparation according to Nextera mate‐pair Illumina guidelines. Tagmentation was done using with a mate‐pair junction adapter and simultaneously fragmented. Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used for fragments profile validation with a DNA 7500 labchip. Fragments’ DNA sizes ranged between 1.5 and 11 kb with an optimal size at 5.933 kb. Additionally, circularization (600 ng of tagmented fragments) was performed with no size selection. The circularized DNA was mechanically sheared to small fragments with optima on a bimodal curve at 475 and 1,207 bp on the Covaris device S2 in T6 tubes (Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA). The library final concentration was measured and visualized on a High Sensitivity Bioanalyzer LabChip (Agilent Technologies Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA) as 27.85 nmol/l. The latter was normalized at 2 nM and pooled. Denaturation was done, and a dilution step to 19 pM was performed prior to pool loading. A single 2 × 251‐bp run was performed with an automated sequencing and cluster generation method. Total information of 4.6 Gb was obtained from a 471 K/mm2 cluster density with a cluster passing quality control filters of 98.7% (9,100,000 passing filter paired reads). Within this run, the index representation for strain Marseille‐P4678T was determined to 20.97%. The 1,908,234 paired reads were trimmed and assembled as previously done (Lagier et al., 2012). Extra‐genomic feature was obtained using Rast tool (Aziz et al., 2008; Brettin et al., 2015; Overbeek et al., 2014). PHAST was used for phage detection (Zhou, Liang, Lynch, Dennis, & Wishart, 2011), RNAmmer for rRNA (Lagesen et al., 2007), and Artemis was used for genome circular representation (Kumar, Tamura, & Nei, 1994). dDDH (DNA‐DNA hybridization) between the genomes was obtained using the online GGDC tool (http://ggdc.dsmz.de/ggdc.php#).

2.5. Phylogenetic analysis

A maximum‐likelihood 16S rRNA gene sequence‐based phylogenetic tree was constructed using the MEGA software with 500 bootstraps (Kumar et al., 1994). Blast was done (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PAGE TYPE=BlastSearch), and NCBI nucleotide database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/) was used for the phylogenetically closest species with standing in nomenclatures’ sequence download. CLUSTAL W was used for sequence alignment (Thompson, Higgins, & Gibson, 1994).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Strain Marseille‐P4678T identification

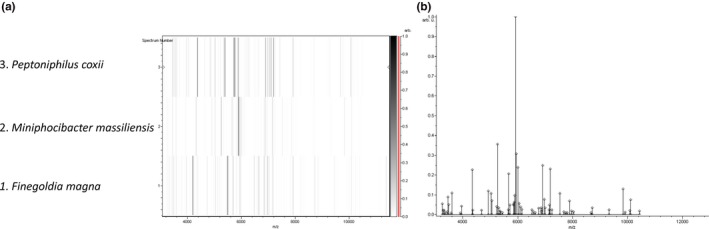

The mass spectrum of strain Marseille‐P4678T was missing in the current MALDI‐TOF MS Bruker database. Thus, its identification with the means of this technique was not possible. Consequently, 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis showed that the understudied organism has more than 5% sequence divergence with Parvimonas micra strain 3119BT (NR 036934.1), its phylogenetically closest species with standing in nomenclature (Figure 1). Thus, according to Kim et al. (2014), we propose the isolation of a new bacterial genus. To analyze at the proteomic level strain Marseille‐P4678T, a gel view comparing the available mass spectra of the phylogenetically closest species with standing in nomenclature was done (Figure 2b). The gel view shows that strain Marseille‐P4678T has a unique peaks profile that does not match completely with any of the implemented organisms. This stands by the fact that this strain represents a new bacterial genus.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree representing the position of strain Marseille‐P4678T relative to other closely related species

Figure 2.

(a) Reference mass spectrum representing of strain Marseille‐P4678T obtained after comparing 12 spectra. (b) Gel view comparing mass spectra of strain Marseille‐P4678T to other species with the raw spectra on the left. The x‐axis represents the m/z value. The left y‐axis indicates the running spectrum number acquired from successive spectra loading. The intensity of the peaks is indicated with the different gray scale, and the y‐axis indicates the relation between the peak color and its intensity

3.2. General features of strain Marseille‐P4678T

Cells of this strain were Gram‐positive cocci, spore‐forming, nonmotile, catalase‐positive, and oxidase‐negative. It forms smooth gray colonies of 0.2 to 0.8 mm diameter on COS medium at 37°C after 48 hr of anaerobic incubation. Strain Marseille‐P4678T cells had a diameter of 0.7 μm (Table 1, Figure 3) when observed under the electron microscope. Nevertheless, strain Marseille‐P4678T grew in a temperature range between 25 and 37°C under microaerophilic and anaerobic conditions but optimally under anaerobic conditions at 37°C. This strain tolerated a pH range between 6 and 8.5 and NaCl concentration up to 100 g/L.

Table 1.

Differential characteristics of strain Marseille‐P4678T, Anaerosphaera aminiphila (AA) (Ueki et al., 2009), Peptoniphilus asaccharolyticus (PA) (Ezaki et al., 2001), Peptoniphilus coxii (PC) (Citron, Tyrrell, & Goldstein, 2012), Parvimonas micra (PM) (Tindall & Euzéby, 2006), Finegoldia magna (FM) (Murdoch & Shah, 1999), and Helcococcus sueciensis (HS) (Collins, Falsen, Brownlee, & Lawson, 2004)

| Properties | Strain Marseille‐P4678T | AA | PA | PC | PM | FM | HS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell diameter (μm) | 0.7 | 0.7–0.9 | Na | 0.7 | 0.3‐0.7 | 0.8‐1.6 | Na |

| Oxygen requirement | Facultative anaerobe | Anaerobic | Anaerobic | Anaerobic | Anaerobic | Anaerobic | Anaerobic |

| Gram stain | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Motility | − | − | − | Na | − | − | − |

| Endospore formation | + | + | − | Na | − | − | − |

| Production of | |||||||

| Alkaline phosphatase | − | Na | − | − | + | V | + |

| Catalase | + | − | Na | − | V | V | − |

| Urease | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| G+C content (mol%) | 28.26 | 32.5 | 32.3 | 44.6 | 28.6 | 32.3 | 28.4 |

| Habitat | Human gut | Methanogenic reactor | Clinical specimen | Clinical specimen | Human | Human | Human wound |

Na: data not available; V: variable.

Figure 3.

Electron micrographs of strain Marseille‐P4678T

Strain Marseille‐P4678T had its unique minimal inhibitory concentrations profile, being 0.25 > 256, 0.032, 0.032, 0.5, >256, 0.75, 0.25, 0.38, >256, 1.5, 0.25, 48, 0.064, 0.125, 0.006, 0.125, 0.25, and >32 (μg/ml) with vancomycin, amikacin, amoxicillin, benzylpenicillin, ceftriaxone, colistin, daptomycin, ertapenem, erythromycin, fluconazole, fosfomycin, imipenem, kanamycin, metronidazole, minocycline, rifampicin, teicoplanin, tobramycin, and voriconazole, respectively, proposing a possible resistance mechanism toward amikacin, colistin, kanamycin, fluconazole, voriconazole. The availability of isolating new bacterial species and drawing its antimicrobial profile urge the scientific community on pursuing efforts toward studying more exhaustively the commensal community of the human microbiota, keeping in mind that most pathogenic bacteria were previously commensals (Isenberg, 1988). Using API ZYM, positive reactions were observed for α‐galactosidase, valine arylamidase, trypsin, naphtol‐AS‐BI‐phosphohydrolase, lipase (C14), esterase lipase (C8), and cystine arylamidase. As for API 50CH, positive reactions were observed with D‐ribose, potassium gluconate, N‐acetylglucosamine, and D‐fructose. Finally, with API 20A, no positive reactions were observed. These results emphasize on the use of proteinaceous compounds as essential elements for this stain's growth. For instance, Gram‐positive anaerobic cocci bacteria are frequently isolated from human and clinical samples, and most of the latter are non‐saccharolytic and rely on peptone for growth (Ezaki et al., 2001; Ueki et al., 2009). Recently, many protein anaerobic degraders were reported such as Clostridium thiosulfatireducens (Hernández‐Eugenio et al., 2002), Clostridium tunisiense (Thabet et al., 2004), and Proteiniphilum acetatigenes (Chen & Dong, 2005). These bacteria were characterized by the use of proteinaceous compounds. When comparing strain Marseille‐P4678T to its phylogenetically close species with standing in nomenclature, we determine that most of these species are also proteinaceous compounds users. For example, Anaerosphaera aminiphila, isolated from a methanogenic reactor, has been reported to be able to degrade several types of amino acids, similarly to P. micra, Finegoldia, and Peptostreptococcus species, which are also member of the Gram‐positive anaerobic cocci family (Ueki et al., 2009). This highlights the potential use of strain Marseille‐P4678T as protein, peptide, and amino acid degraders in the ecosystem.

General features of strain Marseille‐P4678T are represented in Table 1 and are compared to its phylogenetically close species. All the included species were Gram‐positive, anaerobic, and urease‐negative (Table 1).

The major fatty acids were hexadecanoic acid (52%), 9‐octadecenoic acid (22%), and tetradecanoic acid (11%). Minor amounts of other fatty acids were also detected (Table 2). After 72 hr of culture in a hemoculture flask supplemented with blood, we measured a production of acetic (>10 mM), propanoic (3.0 ± 0.2 mM), butyric (3.5 ± 0.2 mM), isobutyric (3.0 ± 0.2 mM), isovaleric (2.2 ± 0.1 mM), and isocaproic (7.2 ± 0.3 mM) acids. Valeric, caproic, and enanthic acids were not detected.

Table 2.

Fatty acids content of strain Marseille‐P4678T

| Fatty acids | Name | Mean relative % a |

|---|---|---|

| 16:0 | Hexadecanoic acid | 51.9 ± 0.8 |

| 18:1ω9 | 9‐Octadecenoic acid | 22.3 ± 1.4 |

| 14:0 | Tetradecanoic acid | 10.8 ± 1.0 |

| 18:2ω6 | 9,12‐Octadecadienoic acid | 6.8 ± 0.4 |

| 18:0 | Octadecanoic acid | 2.2 ± 1.0 |

| 12:0 | Dodecanoic acid | 2.0 ± 0.2 |

| 15:0 | Pentadecanoic acid | 1.6 ± 0.4 |

| 16:1ω7 | 9‐Hexadecenoic acid | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| 13:0 | Tridecanoic acid | TR |

aMean peak area percentage; TR: trace amounts <1%.

3.3. Genome characteristics of strain Marseille‐P4678T

The genome of strain Marseille‐P4678T is 2,083,161 bp long with 28.26 mol% of G+C content. It is composed of 14 contigs. A total of 2,148 genes were detected along with 2,068 coding DNA sequences (CDSs) and 55 RNA genes. rRNA was detected as follow: 4, 3, 1 (5S, 16S, 23S) along with 44 tRNAs. No CRISPRs repeats were found. A total of 802 proteins were annotated as hypothetical proteins. Using PHAST tool, two potential prophages regions have been identified, of which one region is intact and one region is incomplete (Figure 4). The intact region extended in the region 1012948–1042003 with 29.88 mol% of G+C content and shared the highest number of proteins with Bacillus virus 1 (NC 009737) with 25% similar proteins. Phage tracking is important since they might be contributing to virulence mechanisms acquiring due to gene transfer events (Penadés, Chen, Quiles‐Puchalt, Carpena, & Novick, 2015). Based on RAST annotation, 25 factors were correlated to virulence, diseases, and defense from which 12 were correlated to antibiotics resistance and toxic compounds (copper homeostasis, Million et al., 2016, cobalt‐zinc‐cadmium resistance, Vétizou et al., 2015, aminoglycoside adenylyltransferases, Clemente et al., 2012, fluoroquinolones resistance, Million et al., 2016, cadmium resistance, Clemente et al., 2012, and multidrug resistance pumps, Million et al., 2016). As well, 12 invasion and intracellular resistance features were detected (Mycobacterium virulence operon involved in protein synthesis (SSU ribosomal proteins) (Rigottier‐Gois, 2013), Mycobacterium virulence operon involved in an unknown function with a Jag Protein and YidC and YidD (Million et al., 2016), Mycobacterium virulence operon involved in DNA transcription (Million et al., 2016), and Mycobacterium virulence operon involved in protein synthesis (LSU ribosomal proteins) (Tidjani Alou et al., 2017). Spore protection system features were detected, and no motility features were detected, confirming our previous results. Circular genome representation of strain Marseille‐P4678T is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Phage like sequences distribution among the strain Marseille‐P4678T's genome as predict by PHAST tool

Figure 5.

Circular representation of the strain Marseille‐P4678T genome. From outer to inner: coding DNA sequences on the forward strand, coding DNA sequences on the reverse strand, rRNA, tRNA, and G+C plot and skew

3.4. Comparative analysis between the genomes of strain Marseille‐P4678T and closely related species

GGDC online calculator was used with formula 2, in order to calculate the DNA‐DNA hybridization distance (dDDH) between the genome of strain Marseille‐P4678T and other available genomes of the phylogenetically closest species (Table 3). dDDH values are calculated whenever whole genome sequence is available in order to confirm other proteomic, phenotypic, and genomic data that propose the classification of a new species (Mccarthy & Bolton, 1963; Schildkraut, Marmur, & Doty, 1961). Being set as a norm, 70% threshold is adapted to delimitate a species (Mccarthy & Bolton, 1963; Schildkraut, Marmur, & Doty, 1961). Strain Marseille‐P4678T had dDDH values of 18.5, 21.8, 27, 27.5, 20.1, and 19.3 with Anaerosphaera aminiphila WN036T (A. aminiphila), Peptoniphilus asaccharolyticus ATCC 14963T (P. asaccharolyticus), Peptoniphilus coxii RMA 16757T (P. coxii), Helcococcus sueciensis CIP 108183T (H. sueciensis), Finegoldia magna DSM 20470T (F. magna), and Parvimonas micra ATCC 33270T (P. micra), respectively, thus supporting the previous data that suggest the classification of this as a novel bacterial species (Table 3).

Table 3.

Genome comparison between strain Marseille‐P4678T and closely related species using GGDC and formula 2 (dDDH estimates based on identities over HSP length), upper right. The inherent uncertainty in assigning dDDH values from intergenomic distances is presented in the form of confidence intervals

| MM | PM | FM | HS | PC | PA | AA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | 18.5 ± 2.25 | 18.8 ± 2.25 | 23.4 ± 2.35 | 21.6 ± 2.35 | 32.3 ± 2.45 | 19.2 ± 2.3 | 100% |

| PA | 21.8 ± 2.35 | 24.1 ± 2.4 | 32.4 ± 2.45 | 26.8 ± 2.45 | 35.4 ± 2.45 | 100% | |

| PC | 27 ± 2.4 | 28.7 ± 2.45 | 34.9 ± 2.45 | 38.7 ± 2.5 | 100% | ||

| HS | 27.5 ± 2.45 | 21.9 ± 2.35 | 20.4 ± 2.3 | 100% | |||

| FM | 20.1 ± 2.3 | 22.2 ± 2.35 | 100% | ||||

| PM | 19.3 ± 2.3 | 100% | |||||

| MM | 100% |

*Anaerosphaera aminiphila DSM 21120T (AA), Peptoniphilus asaccharolyticus DSM 20463T (PA), Peptoniphilus coxii DNF00729T (PC), Helcococcus sueciensis DSM 17243T (HS), Finegoldia magna ATCC 29328T (FM), Parvimonas micra ATCC 33270T (PM), and Miniphocibacter massiliensis strain Marseille‐P4678T (MM).

The draft genome sequence of strain Marseille‐P4678T size is lower than Peptostreptococcus assachrolyticus but higher than H. sueciensis, P. micra, F. magna, and P. coxii (2.1, 2.2, 1.6, 1.6, 1.8, and 1.8, respectively). The G+C content (mol%) of strain Marseille‐P4678T is higher than those of H. sueciensis but lower than P. micra, F. magna, P. asaccharolyticus, A. aminiphila, and P. coxii (28.26, 28.4, 28.6, 32.3, 32.3, 32.5, and 44.6, respectively). CDSs in strain Marseille‐P4678T were higher than H. sueciensis, P. micra, P. coxii, F. magna, A. aminiphila, and P. asaccharolyticus (2134, 1427, 1476, 1742, 1839, 1,916, and 2054).

4. CONCLUSION

Culturomics has proved that culture is an essential method that should be adapted in complementarity with metagenomics when describing the human microbiota and especially the gut. With the means of this approach, we succeeded in isolating a new bacterial genus (M. massiliensis strain Marseille‐P4678T gen. nov. sp. nov.), thus adding to the current human gut repertoire new species. Its taxono‐genomics description rendered its main features available for the scientific community in case of its isolation in a commensal or pathogenic scene. Nevertheless, sequencing its genome made more nucleotides sequences defined and thus minimized the holes in the current database or what is so‐called Dark Matter.

4.1. Description of Miniphocibacter gen. nov

Miniphocibacter (Mini.phoci.bacter, L. adj. masc., miniphocibacter composed by mini, referring at the small size of pygmy people from whom this strain was isolated, and phoci referring at Phocae, the Latin name of the city from where the funders of culturomics came from). Cells are Gram‐positive cocci, spore‐forming, non‐motile, catalase‐positive, and oxidase‐negative. It forms smooth gray colonies of 0.2 to 0.8 mm diameter on COS medium at 37°C after 48 hr anaerobic incubation and grows optimally under anaerobic conditions at 37°C. Major fatty acids were hexadecanoic acid (52%), 9‐octadecenoic acid (22%), and tetradecanoic acid (11%). Minor amounts of other fatty acids were also detected. The genome of strain Marseille‐P4678T is 2,083,161 bp long with 28.26 mol% of G+C content. The type species is M. massiliensis.

4.2. Description of M. massiliensis sp. nov

Miniphocibacter massiliensis (mas.il.i.en'sis, L. gen. masc. n., massiliensis, pertaining to Massilia, the antic name of the city of Marseille, where this bacterium was discovered).

Cells are Gram‐positive cocci with 0.7 μm in diameter, spore‐forming, non‐motile, catalase‐positive, and oxidase‐negative. It forms smooth gray colonies of 0.2 to 0.8 mm diameter on COS medium at 37°C after 48 hr anaerobic incubation. Nevertheless, strain Marseille‐P4678T grows in a temperature range between 25 and 37°C under microaerophilic and anaerobic conditions but optimally under anaerobic conditions at 37°C. It tolerates a pH range between 6 and 8.5 and NaCl concentration more than 100 g/L. Using APIZYM, positive reactions are observed for α‐galactosidase, valine arylamidase, trypsin, naphtol‐AS‐BI‐phosphohydrolase, lipase (C14), esterase lipase (C8), and cystine arylamidase. As for API50CH, positive reactions are observed with D‐ribose, potassium gluconate, N‐acetylglucosamine, and D‐fructose. Finally, with API20A, no positive reactions are observed. Major fatty acids are hexadecanoic acid (52%), 9‐octadecenoic acid (22%), and tetradecanoic acid (11%). Minor amounts of other fatty acids are also detected. The genome of strain Marseille‐P4678T is 2,083,161 bp long with 28.26 mol% of G+C content.

The type strain is Marseille‐P4678T and was isolated from the stool sample of a healthy 39‐year‐old pygmy male from Congo.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None to be declared.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MB isolated, described, and wrote the manuscript. MF helped in the taxono‐genomics description. TN helped in the genomic sequencing. MR helped in genome sequencing. ZD helped in writing and critical analysis of the manuscript. PF helped in writing and critical analysis of the manuscript. DR designed the project, and helped in writing, reviewing, and critical analysis. FC designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

An approval under the number 09‐022 was obtained from the Ethic Committee of the Institut Fédératif de Recherche 48 along with a signed consent from the sample's donor. The donor was a healthy 39‐year‐old pygmy male, and collection was done according to Nagoya protocol from Republic of Congo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by IHU Méditerranée Infection, Marseille, France, and by the French Government under the “Investissements d'avenir” (Investments for the Future) program managed by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR, fr: National Agency for Research) (reference: Méditerranée Infection 10‐IAHU‐ 03). This work was supported by Région Provence Alpes Côte d'Azur and European funding FEDER PRIMI.

Bilen M, Mbogning Fonkou MD, Nguyen TT, et al. Miniphocibacter massiliensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a new species isolated from the human gut and its taxono‐genomics description. MicrobiologyOpen. 2019;8:e735 10.1002/mbo3.735

DATA ACCESSIBILITY

Genome sequences of strain Marseille‐P4678T were deposited in EMBL‐EBI and can be accessed with the following accession numbers: LT934441 and OCTQ00000000.

The type strain is Marseille‐P4678T and was deposited in two international strain collection institutes with the following accession numbers: CSUR P4678T = CCUG 71375T.

Strain Marseille‐P4678T typical mass spectrum can be accessed on http://www.mediterranee-infection.com/article.php?larub=280&titre=urms-database.

References

- Aziz, R. K. , Bartels, D. , Best, A. A. , DeJongh, M. , Disz, T. , Edwards, R. A. , … Zagnitko, O. (2008). The RAST Server: Rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics, 9, 75 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilen, M. , Cadoret, F. , Richez, M. , Tomei, E. , Daoud, Z. , Raoult, D. , & Fournier, P. E. (2018). Libanicoccus massiliensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a new bacterium isolated from human stool. New Microbes and New Infections, 21, 63–71. 10.1016/j.nmni.2017.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brettin, T. , Davis, J. J. , Disz, T. , Edwards, R. A. , Gerdes, S. , Olsen, G. J. , … Xia, F. (2015). RASTtk: A modular and extensible implementation of the RAST algorithm for building custom annotation pipelines and annotating batches of genomes. Scientific Reports, 5, 8365 10.1038/srep08365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. , & Dong, X. (2005). Proteiniphilum acetatigenes gen. nov., sp. nov., from a UASB reactor treating brewery wastewater. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 55(Pt 6), 2257–2261. 10.1099/ijs.0.63807-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citron, D. M. , Tyrrell, K. L. , & Goldstein, E. J. C. (2012). Peptoniphilus coxii sp. nov. and Peptoniphilus tyrrelliae sp. nov. isolated from human clinical infections. Anaerobe, 18(2), 244–248. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, J. C. , Ursell, L. K. , Parfrey, L. W. , & Knight, R. (2012). The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: An integrative view. Cell, 148(6), 1258–1270. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, M. D. , Falsen, E. , Brownlee, K. , & Lawson, P. A. (2004). Helcococcus sueciensis sp. nov., isolated from a human wound. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 54(Pt 5), 1557–1560. 10.1099/ijs.0.63077-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dione, N. , Sankar, S. A. , Lagier, J.‐C. , Khelaifia, S. , Michele, C. , Armstrong, N. , … Fournier, P. E. (2016). Genome sequence and description of Anaerosalibacter massiliensis sp. nov. New Microbes and New Infections, 10, 66–76. 10.1016/j.nmni.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drancourt, M. , Berger, P. , & Raoult, D. (2004). Systematic 16S rRNA gene sequencing of atypical clinical isolates identified 27 new bacterial species associated with humans. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 42(5), 2197–2202. 10.1128/JCM.42.5.2197-2202.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezaki, T. , Kawamura, Y. , Li, N. , Li, Z. Y. , Zhao, L. , & Shu, S. (2001). Proposal of the genera Anaerococcus gen. nov., Peptoniphilus gen. nov. and Gallicola gen. nov. for members of the genus Peptostreptococcus . International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 51(4), 1521–1528. 10.1099/00207713-51-4-1521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, P.‐E. , & Drancourt, M. (2015). New Microbes New Infections promotes modern prokaryotic taxonomy: A new section ‘TaxonoGenomics: New genomes of microorganisms in humans’. New Microbes and New Infections, 7, 48–49. 10.1016/j.nmni.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greub, G. (2012). Culturomics: A new approach to study the human microbiome. Clinical Microbiology & Infection, 18(12), 1157–1159. 10.1111/1469-0691.12032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández‐Eugenio, G. , Fardeau, M.‐L. , Cayol, J.‐L. , Patel, B. K. C. , Thomas, P. , Macarie, H. , … Ollivier, B. (2002). Clostridium thiosulfatireducens sp. nov., a proteolytic, thiosulfate‐ and sulfur‐reducing bacterium isolated from an upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) reactor. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 52(Pt 5), 1461–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugon, P. , Dufour, J.‐C. , Colson, P. , Fournier, P.‐E. , Sallah, K. , & Raoult, D. (2015). A comprehensive repertoire of prokaryotic species identified in human beings. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 15(10), 1211–1219. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00293-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg, H. D. (1988). Pathogenicity and virulence: Another view. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 1(1), 40–53. 10.1128/CMR.1.1.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M. , Oh, H.‐S. , Park, S.‐C. , & Chun, J. (2014). Towards a taxonomic coherence between average nucleotide identity and 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity for species demarcation of prokaryotes. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 64(Pt 2), 346–351. 10.1099/ijs.0.059774-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. , Tamura, K. , & Nei, M. (1994). MEGA: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software for microcomputers. Computer Applications in the Biosciences, 10(2), 189–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagesen, K. , Hallin, P. , Rødland, E. A. , Staerfeldt, H.‐H. , Rognes, T. , & Ussery, D. W. (2007). RNAmmer: Consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Research, 35(9), 3100–3108. 10.1093/nar/gkm160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagier, J.‐C. , Armougom, F. , Million, M. , Hugon, P. , Pagnier, I. , Robert, C. , … Raoult, D. (2012). Microbial culturomics: Paradigm shift in the human gut microbiome study. Clinical Microbiology & Infection, 18(12), 1185–1193. 10.1111/1469-0691.12023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagier, J.‐C. , El Karkouri, K. , Nguyen, T.‐T. , Armougom, F. , Raoult, D. , & Fournier, P.‐E. (2012). Non‐contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Anaerococcus senegalensis sp. nov. Standards in Genomic Sciences, 6(1), 116–125. 10.4056/sigs.2415480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagier, J.‐C. , Khelaifia, S. , Alou, M. T. , Ndongo, S. , Dione, N. , Hugon, P. , … Raoult, D. (2016). Culture of previously uncultured members of the human gut microbiota by culturomics. Nature Microbiology, 1, 16203 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Mccarthy, B. J. , & Bolton, E. T. (1963). An approach to the measurement of genetic relatedness among organisms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 50, 156–164. 10.1073/pnas.50.1.156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Million, M. , Tidjani Alou, M. , Khelaifia, S. , Bachar, D. , Lagier, J.‐C. , Dione, N. , … Raoult, D. (2016). Increased gut redox and depletion of anaerobic and methanogenic prokaryotes in severe acute malnutrition. Scientific Reports, 6(1). 10.1038/srep26051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Murdoch, D. A. , & Shah, H. N. (1999). Reclassification of Peptostreptococcus magnus (Prevot 1933) Holdeman and Moore 1972 as Finegoldia magna comb. nov. and Peptostreptococcus micros (Prevot 1933) Smith 1957 as Micromonas micros comb. nov. Anaerobe, 5(5), 555–559. 10.1006/anae.1999.0197 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek, R. , Olson, R. , Pusch, G. D. , Olsen, G. J. , Davis, J. J. , Disz, T. , … Stevens, R. (2014). The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Research, 42(Database issue), D206–D214. 10.1093/nar/gkt1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penadés, J. R. , Chen, J. , Quiles‐Puchalt, N. , Carpena, N. , & Novick, R. P. (2015). Bacteriophage‐mediated spread of bacterial virulence genes. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 23, 171–178. 10.1016/j.mib.2014.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raoult, D. , & Henrissat, B. (2014). Are stool samples suitable for studying the link between gut microbiota and obesity? European Journal of Epidemiology, 29(5), 307–309. 10.1007/s10654-014-9905-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigottier‐Gois, L. (2013). Dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel diseases: The oxygen hypothesis. ISME Journal, 7(7), 1256–1261. 10.1038/ismej.2013.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schildkraut, C. L. , Marmur, J. , & Doty, P. (1961). The formation of hybrid DNA molecules and their use in studies of DNA homologies. Journal of Molecular Biology, 3, 595–617. 10.1016/S0022-2836(61)80024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seng, P. , Rolain, J.‐M. , Fournier, P. E. , La Scola, B. , Drancourt, M. , & Raoult, D. (2010). MALDI‐TOF‐mass spectrometry applications in clinical microbiology. Future Microbiology, 5(11), 1733–1754. 10.2217/fmb.10.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thabet, O. B. D. , Fardeau, M.‐L. , Joulian, C. , Thomas, P. , Hamdi, M. , Garcia, J.‐L. , & Ollivier, B. (2004). Clostridium tunisiense sp. nov., a new proteolytic, sulfur‐reducing bacterium isolated from an olive mill wastewater contaminated by phosphogypse. Anaerobe, 10(3), 185–190. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2004.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. D. , Higgins, D. G. , & Gibson, T. J. (1994). CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position‐specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Research, 22(22), 4673–4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidjani Alou, M. , Million, M. , Traore, S. I. , Mouelhi, D. , Khelaifia, S. , Bachar, D. , … Raoult, D. (2017). Gut Bacteria missing in severe acute malnutrition, can we identify potential probiotics by culturomics? Frontiers in Microbiology, 8, 899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tindall, B. J. , & Euzéby, J. P. (2006). Proposal of Parvimonas gen. nov. and Quatrionicoccus gen. nov. as replacements for the illegitimate, prokaryotic, generic names Micromonas Murdoch and Shah 2000 and Quadricoccus Maszenan et al. 2002, respectively. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 56(11), 2711–2713. 10.1099/ijs.0.64338-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueki, A. , Abe, K. , Suzuki, D. , Kaku, N. , Watanabe, K. , & Ueki, K. (2009). Anaerosphaera aminiphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a glutamate‐degrading, Gram‐positive anaerobic coccus isolated from a methanogenic reactor treating cattle waste. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 59(Pt 12), 3161–3167. 10.1099/ijs.0.011858-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vétizou, M. , Pitt, J. M. , Daillère, R. , Lepage, P. , Waldschmitt, N. , Flament, C. , … Zitvogel, L. (2015). Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA‐4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science, 350(6264), 1079–1084. 10.1126/science.aad1329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Würdemann, D. , Tindall, B. J. , Pukall, R. , Lünsdorf, H. , Strömpl, C. , Namuth, T. , … Oxley, A. P. A. (2009). Gordonibacter pamelaeae gen. nov., sp. nov., a new member of the Coriobacteriaceae isolated from a patient with Crohn's disease, and reclassification of Eggerthella hongkongensis Lau et al. 2006 as Paraeggerthella hongkongensis gen. nov., comb. nov. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 59(Pt 6), 1405–1415. 10.1099/ijs.0.005900-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, G. , Nyman, M. , & Jönsson, J. A. (2006). Rapid determination of short‐chain fatty acids in colonic contents and faeces of humans and rats by acidified water‐extraction and direct‐injection gas chromatography. Biomedical Chromatography, 20(8), 674–682. 10.1002/(ISSN)1099-0801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. , Liang, Y. , Lynch, K. H. , Dennis, J. J. , & Wishart, D. S. (2011). PHAST: A fast phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Research, 39(Suppl. 2), W347–W352. 10.1093/nar/gkr485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Genome sequences of strain Marseille‐P4678T were deposited in EMBL‐EBI and can be accessed with the following accession numbers: LT934441 and OCTQ00000000.

The type strain is Marseille‐P4678T and was deposited in two international strain collection institutes with the following accession numbers: CSUR P4678T = CCUG 71375T.

Strain Marseille‐P4678T typical mass spectrum can be accessed on http://www.mediterranee-infection.com/article.php?larub=280&titre=urms-database.