Abstract

Delivering molecules to the plasma membrane of single cells is still a challenging task in profiling cell signaling pathways with single cell resolution. We demonstrated that large quantity of molecules could be targeted and released onto the membrane of individual cells to trigger signaling responses. This is achieved by a porous pen nanodeposition (PPN) method, in which a multilayer porous structure, serving as a reservoir for a large amount of molecules, is formed on an atomic force microscope (AFM) tip using layer-by-layer assembly and post processing. To demonstrate its capability for single cell membrane drug delivery, PPN was employed to induce a Calcium flux triggered by the binding of released antibodies to membrane antigens in an autoimmune skin disease model. This Calcium signal propagates from the target cell to its neighbors in a matter of seconds, proving the theory of intercellular communication through cell-cell junctions. Collectively, these results demonstrated the effectiveness of PPN in membrane drug delivery for single cell; to the best of our knowledge, this is the first technique that can perform the targeted transport and delivery in single cell resolution, paving the way for probing complex signaling interactions in multicellular settings.

Keywords: porous pen nanodeposition, layer by layer assembly, drug delivery, single cell analysis, atomic force microscopy

1. INTRODUCTION

Extracellular compounds trigger intracellular signaling pathways and further regulate cell behavior after binding to membrane receptor.[1] For therapeutic purposes, more than 60% of approved drugs target membrane receptors,[2] and this trend remains for discovering new drugs.[3] In autoimmune diseases, for example, pathogenic autoantibodies induce dysfunctional cellular behavior after binding to their membrane antigens.[4,5] Compound-activated cells may transmit the induced behavior to neighboring cells via intercellular communications.[6,7] The mechanisms of this transmission, a major knowledge gap, can be explored by profiling the cell signaling process spatially. This type of profiling, however, has been hindered by the lack of tools for delivering molecules onto plasma membrane of single cells. Diffusing drugs to cell culture media releases molecules to the entire cell population and prevents the study of intercellular communication. Though micro-injection[8,9] and carrier-based methods[10] have been developed for single cell delivery purposes, these tools deliver drugs “into” the cytosol, rather than “onto” the plasma membrane. They are more suitable for intracellular stimulation intervention. Towards this end, nanocarriers for delivering cytokines onto cell membrane was developed. This novel nanocarrier can target tumor cells and sustainably release cytokines and potentially other proteins.[11,12] These nanocarriers are designed for delivery to cell populations towards clinical application. Therefore, a method for single-cell plasma membrane drug delivery is required to facilitate new approaches for investigating compound-activated cell signaling.

Functionalized atomic force microscope (AFM) probes have been deployed for a range of biomedical applications,[13–16] including drug delivery.[17–20] Functionalized AFM tip stimulates individual cells mechanically and chemically, while an integrated optical microscope system monitors the cellular and molecular responses simultaneously.[21–25] To load molecules, the surface of an AFM probe is often aminosilanized with silane molecules, such as (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES) and aminophenyl-trimethoxysilane (APhS).[26–28] A single layer of protein molecules are conjugated to the salinized tip surface through covalent bonds or electrostatic interactions.[29] The molecules loaded onto the tip interact with their membrane receptors when the AFM tip is in contact with cells [20,30]. In drug delivery, however, this approach is restricted by the amount of protein molecules loaded on a probe. The amount of protein molecules in a single layer is limited by the small surface area of an AFM tip. Thus, forming a reservoir to store enough protein molecules is of significant value for drug delivery onto cell membrane.

Promisingly, a porous structure formed by layer-by-layer (LbL) assembly has the potential to serve as such a reservoir.[31–33] LbL assembly is a promising technology toward biomedical applications due to its aqueous-based and tunable fabrication process, as well as the broad choices of substrate materials.[33–35] AFM tips functionalized by the LbL process with multiple layers of polyelectrolytes stored much more protein molecules on the tip than those with a single functionalized layer.[36] Using this method, patterns of protein molecules at micrometer and submicrometer scale were fabricated via dip pen nanolithography (DPN) in air. Ultrathin as the polyelectrolyte multilayers were, the free space in the reported structure was limited. In addition, its usage for drug delivery in liquid is hindered by the unstable hydrogen-bonded multilayers and the long deposition time during fabrication. Its utility is further confined in air due to the requirement of meniscus formation between the tip and the substrate.[37]

To address these problems, we present a porous pen method using an AFM tip with a porous structure fabricated by an innovative process of LbL assembly and post processing. With fast LbL assembly, the deposition time was reduced to less than 1 minute/layer compared with 10 minutes/layer previously.[36,38] The thickness of a porous structure formed by our method increases to several micrometers as compared to tens of nanometers as previously reported;[36] and the porous structure can store a large quantity of protein molecules. Protein loading, diffusion, and contact release were demonstrated using porous pen nanodeposition (PPN). To demonstrate its capability of single-cell membrane drug delivery, antibody molecules were loaded and delivered onto membranes of single cells. The transmission of antibody-induced cell signaling within cell monolayer was profiled using Calcium flux assay. Collectively, these results demonstrated the effectiveness of PPN as a drug delivery platform. The successful usage of PPN for delivery antibodies onto cell membrane may pave the way for its further application in cell signaling studies, drug development, and toxicological investigations.

2. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

2.1. An on-tip porous reservoir for drug delivery

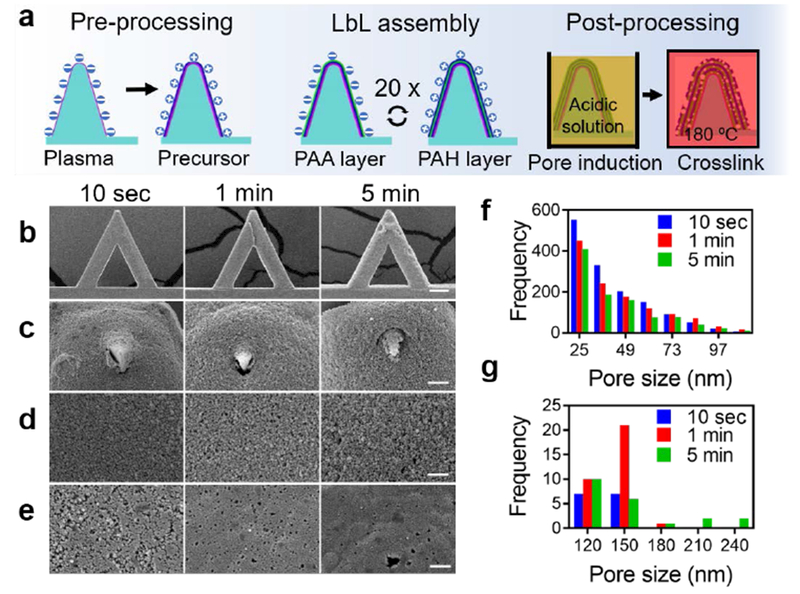

A porous structure can be formed by immersing poly allylamine hydrochloride (PAH)/poly acrylic acid (PAA) multilayers in an acidic aqueous solution with pH ranging from 1.6 to 2.6.[33,39] Modulating the molecular weight[38], pH level of the solution, and the exposure time during pore induction can fabricate porous structures with thicknesses ranging from nanometers to micrometers.[33] Free amine and carboxylate groups crosslinked on the surface of porous structures provide binding sites for the loaded molecules. Similar molecular structures, tunable porous characteristics, fast fabrication, and abundant protein binding sites all together make the PAH/PAA multilayer porous structure an ideal reservoir for protein loading and delivery[40]. Experimental results also demonstrated the bioactivity of proteins released from PAH/PAA and other polyelectrolyte multilayers of LbL-formed porous structure[40]. LbL-formed multilayers and porous structures are widely used in tissue engineering[41], and the protein bioactivity issues were intensively studied[42]. Here, a PAH/PAA multilayer porous structure on AFM tip was formed via fast LbL assembly followed by acidic treatment at pH 2.0. The fabrication process is described in detail in methods section. Briefly, the surface of AFM probe is functionalized with hydroxyl group via plasma treatment. After coating the precursor PAH layer, PAA and PAH layers are alternatively functionalized onto the probe through LbL assembly. This multilayer structure is transformed to be porous after acidic treatments and crosslinked at 180 °C temperature (Figure 1a).[38]

Figure 1. Fabrication and characterization of porous pens.

a) The fabrication process of Layer-by-Layer (LbL) assembly-formed porous structures on the surface of an AFM cantilever and tip. b) SEM observation of porous pens on the entire cantilever. c) SEM observation of tips of porous pens. d) Zoom-in SEM observation of the surface of AFM tips. e) Zoom-in SEM observation of the surface of cantilevers. f-g) Frequency analysis of pores sizes on the surface of porous pens fabricated with different deposition times: for pore sizes smaller than 110 nm (f) and larger than 110 nm (g). Scale bars in (b) 50 μm, (c) 2 μm, (d-e) 1 μm.

The porous pen has unique characteristics compared with the porous structures formed on glass slides. Changing the deposition time can tune the morphological characteristics of the porous structure. First, a longer deposition time increases the thickness and roughness of the porous structures as evidenced by the SEM images of porous pens with different deposition times in Figure 1b. This result is consistent with our previous results of coating a porous structure on glass slides.[38] In addition, a longer deposition time increases the pore size (Figure 1c and f). The 10-second deposition condition produces the most pores with diameters smaller than 61 nm (Figure 1f); while the 1-minute and 5-minute deposition conditions produce more pores with sizes larger than 110 nm (Figure 1g). For pores smaller than 110 nm, the samples with all three deposition times have similar distributions (Figure 1f). However, for pores larger than 110 nm, longer deposition times leads to larger pore sizes (Figure 1g). In addition, the microscale size and complicated geometries of the AFM cantilever and tip affect the morphology of porous structures. Compared with porous structures on glass slides, porous pens in all three deposition conditions have smaller pores.[38] In a porous pen, the morphology of the porous structures on the on-tip reservoir (Figure 1d) differentiates from that of the cantilever (Figure 1e). Due to the sharp edges and the microscale dimension of an AFM cantilever and tip, it is highly possible that the residual stress was trapped within the multilayers during the LbL assembly and were relaxed during the porous induction. This varies the behaviors of chain rearrangement during the formation of porous structures at different positions. Collectively, a porous structure is formed on an AFM tip to serve as a reservoir for molecules, and the microscale AFM cantilever and tip affect the morphology of the porous structure.

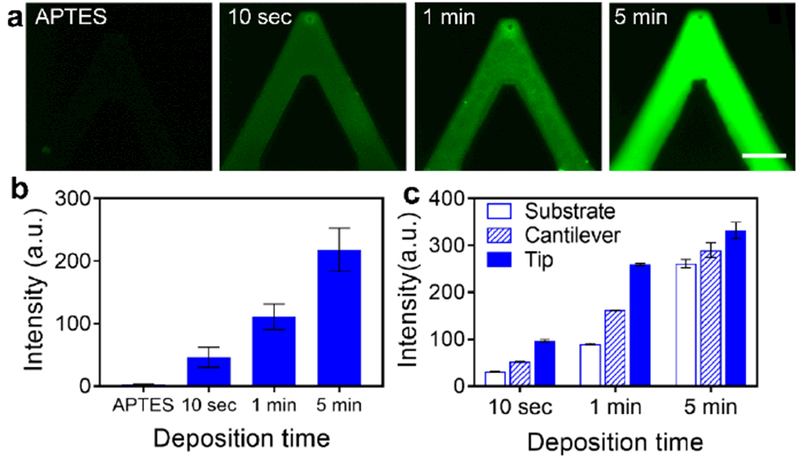

Compared with the APTES aminosilanized AFM cantilevers, porous pens load much more protein molecules with better uniformity. To apply porous pens for targeted antibody delivery relevant to human diseases, we used a disease model of pemphigus vulgaris (PV), a blistering autoimmune skin disorder, which is associated with the binding of anti-desmoglein (Dsg) antibodies to keratinocytes (skin cells). For this purpose, an anti-Dsg3 monovalent IgG antibody[43] was loaded onto APTES-aminosilanized AFM cantilevers and porous pens. Revealed by fluorescence images of secondary antibodies, both APTES aminosilanized AFM cantilevers and porous pens were successfully functionalized with protein molecules, but with different characteristics (Figure 2a). Compared with APTES aminosilanized AFM cantilevers, porous pens loaded much more protein molecules (~ 20 to 50 times more as evaluated by the fluorescence intensity) (Figure 2b). In addition, porous pens fabricated with longer deposition times loaded more protein molecules. Both chemical and physical characteristics of porous pens might be accountable for this. First, chemical similarity between the porous reservoirs and the protein molecules as well as ample amount of binding sites for protein molecules enhance protein loading in a porous pen. Both protein molecules and porous PAH/PAA multilayer materials contain hydrophilic functional groups and hydrophobic backbones. Besides, ample amount of amine and carboxylate groups exist on the surface of porous reservoirs. Second, porous pens have larger surface area for protein loading. Compared with the single layer APTES aminosilanization, a porous pen offers larger surface area, which provides more binding sites for loaded molecules. Meanwhile, the pores also serve as microscale reservoirs for protein solution. The deposition time in LbL assembly varies the thickness and the surface area of the porous structure, and thus tunes the amount of protein molecules loaded onto the probe. Interestingly, the amount of loaded protein molecules varied on the probe substrate, the cantilever and the tip. Tips store more molecules than cantilevers and probe substrates. This might be induced by the morphological differences of porous structures at different locations (Figure 2c). For the fluorescent secondary antibody, the fluorescence intensity is proportional to the concentration of antibody solution, thus it is an ideal indicator for protein concentration (Supplemental materials, Figure S1a). Since some protein molecules are absorbed onto the surface of porous structure, the fluorescence intensity cannot be directly interpreted as protein concentration. We thus termed it as nominal concentration (Supplemental materials, Figure S1b).

Figure 2. Characterization of protein loading on porous pens and APTES functionalized AFM cantilevers.

a) Amount of protein loading on an APTES functionalized AFM probe and porous-structured AFM probes fabricated with three deposition times: 10 seconds, 1 minute, and 5 minutes. b) The intensity level of the four experimental conditions. c) The amount of protein loading at the substrate of probes, the cantilever and the tip of porous pens. Scale bar in (a): 30 μm.

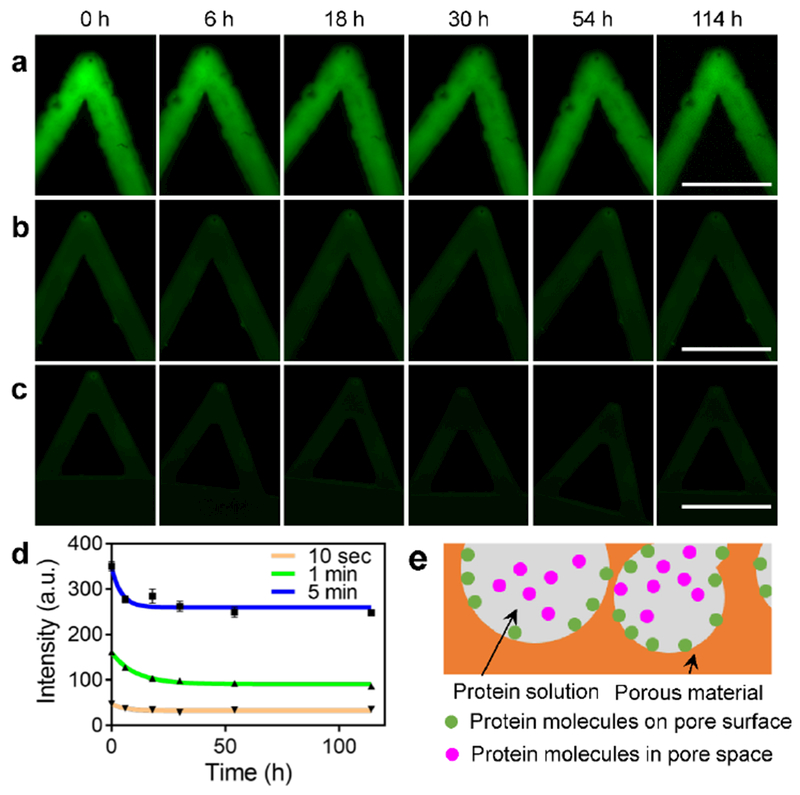

2.2. Diffusion of loaded protein molecules

To achieve single-cell membrane drug delivery, the diffusion of loaded protein molecules should be minimized to avoid unexpected delivery. Here, the diffusion of loaded proteins was evaluated by fluorescence imaging. Diffusion of protein molecules occurs when the porous pen is incubated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution (Figure 3a-c). In the first 6 hours, protein molecules diffused faster from porous pens fabricated with longer deposition time. This might be due to the larger pore sizes in porous pens with longer deposition time. Though deposition time affects the initial diffusion rates, protein diffusion is stabilized after 48-hour incubation at roughly the same percentage, around 70% for three samples with different deposition times, as evaluated by the fluorescence intensity. For porous structures with deposition time of 10 seconds, 1 minute and 5 minutes, the percentages of the molecule diffusion are 30.1%, 27.7% and 31.2%, respectively (Figure 3d).

Figure 3. Diffusion of loaded protein molecules from porous pens fabrication with different deposition times.

a-c) Representative fluorescence images of porous pen samples during protein diffusion of 114 hours. Porous pens are fabricated with 5-minute (a), 1-minute (b), and 10-second (c) deposition times, respectively. d) The fluorescence intensity of the three experimental conditions over 114 hours. e) A diagram illustrates the two types of protein interactions with the porous structure. Scale bars in (a), (b), and (c): 100 μm.

This biphasic diffusion pattern (rapid followed by sustained diffusions) can be explained by the two states of loaded protein in a porous pen: attached on the pore surface or confined in the pore space (Figure 3e). Considering chemical characteristics, protein molecules interacts with a porous structure in several regimes, including electrostatic interactions through the ammonium and carboxylate ion groups, and secondary interactions, such as hydrophobic interaction and Van der Waals interaction.[44] The protein molecules confined in the pore space experience weaker interactions than those attached on the pore surface. The initial rapid diffusion is due to the release of those confined in the pore space (Figure 3d). This theoretical analysis is consistent with the first order kinetics (the diffusion rate decreases over time) of the experimental data. The molecules attached on the pore surface may need longer time to be released, thus some of them stayed in the porous reservoir after the two-day diffusion process (Figure 3d). Considering the experiments using porous pen only last for a few minutes, experiments with longer diffusion time were not performed.

As reported, porous structures with microscale and nanoscale pores on glass slides have different diffusion profiles[40]. Porous structures with nanoscale pores have few (compared with the number of diffusion molecules) openings on the surface, and exhibit zero-order diffusion kinetics; while porous structures with microscale pores is filled with pores open to the surface, and thus exhibit first-order diffusion kinetics,[45,46] as is the case with the porous structure on the AFM probes.

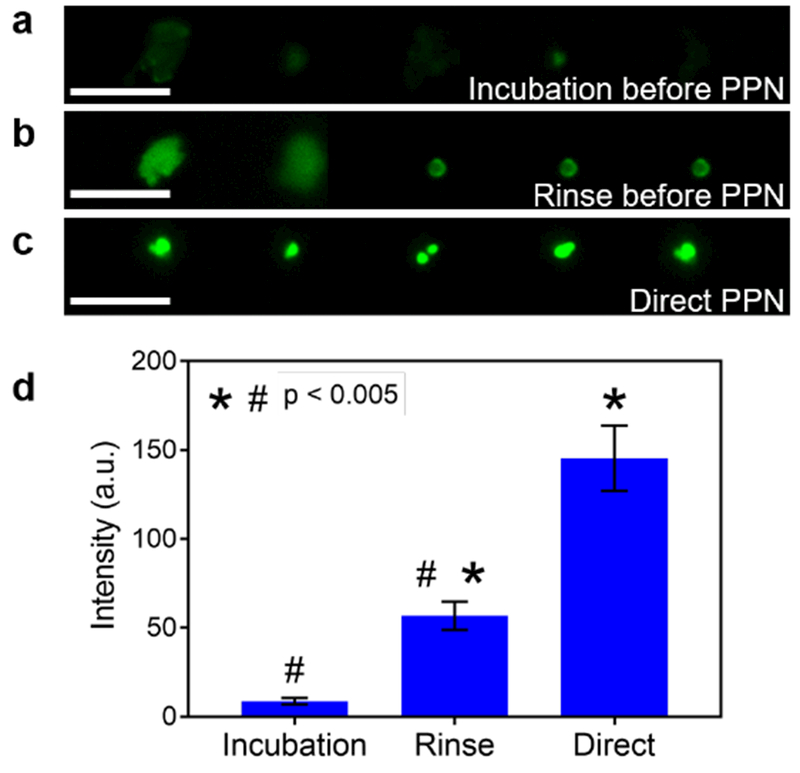

2.3. Contact release of loaded molecules

To test the contact release of the loaded protein molecules, PPN was performed. Incubated in florescence antibody solution for one hour, the porous pen was mounted onto a nanopositioner to perform controlled contact release of molecules. The TPEDA-functionalized substrate is positively charged. Depositing protein molecules onto the substrate, PPN successfully generated a dot-pattern of molecules (Figure 4a-c). These results are consistent with previous DPN study in air.[36] To limit the effect of diffusion, the porous pen were rinsed in PBS for three times to remove loosely bound protein molecules prior to PPN (Figure 4b). Incubating the porous pens in PBS for two days prior to the experiment, protein molecules can still be successfully deposited onto the substrate (Figure 4a). The quantity of molecules deposited, evaluated by the intensity of fluorescence signals, was reduced significantly after the porous pens were rinsed or incubated in PBS (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

Porous pen nanodeposition (PPN) of protein molecules onto a substrate. (a-c) Representative results for PPN experiments after porous pens are incubated (a) or rinsed (b) in PBS, or directly after protein loading (c). d) The fluorescence intensity of deposited protein dots in the three experimental conditions. Scale bars in (a), (b), and (c): 5 μm.

Though working in different conditions, PPN and DPN are similar in two aspects: 1) molecular transport from a tip to a substrate; 2) molecular deposition onto the substrate.[47–50] For molecular transport, DPN in air requires the formation of solution meniscus between the tip and substrate,[37] which does not apply for PPN. PPN thus has a different molecular transport mechanism. When a porous pen contacts a substrate, the positively-charged substrate attracts the loaded molecules. Inversely proportional to the substrate-molecule distance, this attraction force generates a concentration gradient of loaded molecules. This gradient facilitates the flow of loaded molecules towards the substrate.[48] As the molecules on the very tip deposited onto the substrate, other molecules will follow the gradient and flow to the nearest available substrate surface.[49]

Since the protein-loaded porous pen had been either rinsed or incubated in PBS, diffusion could be minimized. According to previous reports, small molecules (254 Da and 507 Da) diffuse from similar porous structures on glass slides very slowly, less 30 ng/cm2/day for nanoscale pores and around 50 ng/cm2/day for microscale pores.[40] The antibody molecules (~hundred kDa) and microscale surface area of porous pen further decrease the diffusion rates.[51] In addition, PPN lasted for around 1 minute. The low diffusion rate and short diffusion time together make the diffusion negligible.

2.4. Antibody delivery to single cell membrane and induction of intercellular signaling

For delivering drugs onto membranes of single cells, two conditions should be met. First, molecular diffusion should be minimized; second, molecular deposition from the porous pen to plasma membranes should be maximized. To minimize diffusion of protein molecules, the protein loaded porous pens were rinsed in PBS for three times, and further incubated in PBS for two hours prior to PPN delivery attempts. In addition, the short contact time (less than 1 minute) and large molecular weight of antibody (150 kDa) together decrease the diffusion rate. To maximize deposition of protein molecules, strong protein-receptor interaction facilitates releasing the protein molecules from the porous structure to the plasma membrane. Furthermore, the continuously floating membrane receptors enhances the deposition of antibody.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of drug delivery onto the plasma membrane of single cells using PPN, we utilized the antibody-antigen interaction in PV as a model system. In PV, autoantibodies bind to the extracellular domain of Dsg3 and Dsg1, cadherin molecules integral to the intercellular desmosomes structures[52]. Anti-Dsg antibodies have been shown to be pathogenic. They dissociate desmosomes, enlarge the spacing between neighboring cells,[24,53] and the induce Calcium (Ca)-signaling.[54] It is still unclear whether the Ca-signal induced in one cell can be transmitted to neighboring cells via intercellular communications (Figure 5a-b).[55–57]

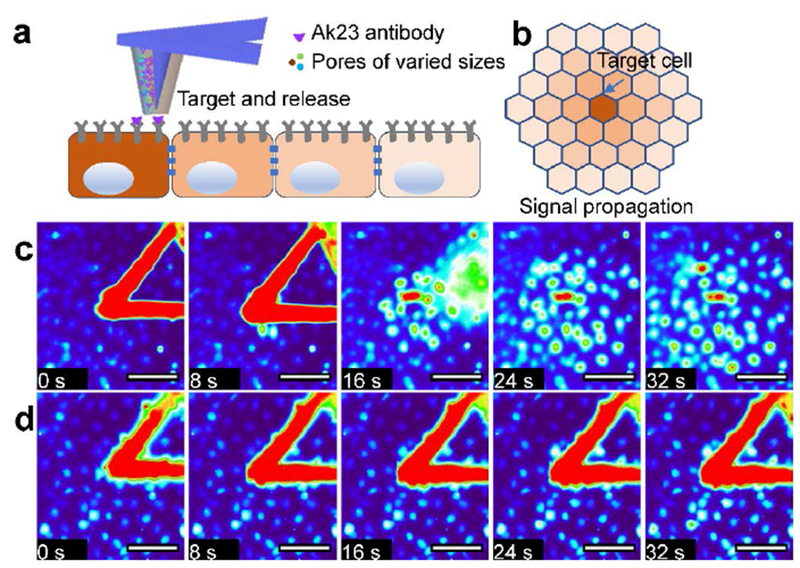

Figure 5. PPN enabled spatial profiling of antibody-induced cell signaling in keratinocyte monolayer.

a) A diagram of targeting and releasing of loaded antibody molecules onto the membrane of a single cell in a cell monolayer. b) The gradient of Calcium signal within the monolayer around the targeted cell. c) Time-lapse fluorescence images of cells stimulated by an AK23 loaded porous pen. d) Time-lapse fluorescence images of cells stimulated by negative control of a porous pen. Scale bars in (c)(d): 100 μm.

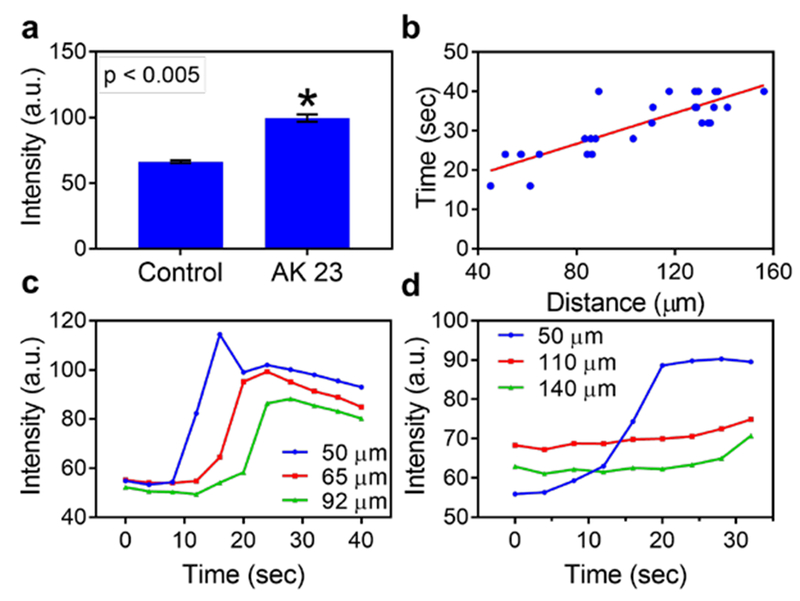

To address this question, we delivered antibody molecules to a single HaCaT cell in a confluent monolayer using PPN. A commercially available anti-Dsg antibody, AK23, was loaded onto a porous pen. With the help of a nanopositioner, PPN was carried out to deliver the antibody molecules to the individual cell of interests. We first demonstrated the capability to deposit protein molecules onto cell membrane of a single cell using GFP-tag antibody (Supplemental materials, Figure S2). The contact between the porous pen and the cell is detected by the deflection of the AFM cantilever. AK23 induced Ca-signal in the target cell (Figure 5c). In addition, AK23-activated Ca-signal could be transmitted to neighboring cells via intercellular communication. Interestingly, this Ca-signal did not only transmit to the immediate neighbor cells, but also to cells further away from the target cell (Figure 5c and the supplemental videos). In the control experiment (no antibody molecules loaded in the porous pen), a weak Ca-signal was induced in the target cell. This signal, however, decayed quickly and does not induce Calcium wave in neighboring cells (Figure 5d). AK23 antibody induced the Ca-signal was much stronger than that of the control group (Figure 6a). Immediately after treating cell with AK23, the Ca2+ intensity increased near the drug delivery spot (depicted by the blue line in Figure 6c). This signal was then transmitted to neighboring cells, as the Ca-signals were elevated (Figure 6c, red and green lines). The timing of Ca-signal peak in a neighboring cell is proportional to its distance from the stimulated cell (Figure 6b). This indicates that the signal is transmitted evenly from the target cell to surrounding cells. In the control experiment, an increase in Ca-signal was detected in the target cell (Figure 6d, blue line), but no observable signal was detected in its surrounding cells (Figure 6d). The signal at the contact point might be induced by the mechanical contact itself.[30,58,59] Taken together, our data show for the first time that anti-Dsg autoantibody-induced Ca-signals can spread via intercellular communication.

Figure 6. Quantitative analysis of the spatial profile of AK23-induced Calcium signals within a keratinocyte monolayer.

a) The fluorescence intensity of experimental and control groups 32 seconds after stimulations. b) The induction time of Calcium signal of neighboring cells is linearly related with the distance between this cell to the target cell. c-d) The Calcium wave signals of three cells with different distances from the stimulated cell in experimental (c) and negative control (d) groups.

3. CONCLUSION

We demonstrated single-cell membrane drug delivery using PPN. A porous pen was made by forming a porous structure on an AFM tip using fast LbL assembly and post processing. We observed for the first time that antibody induced Ca-signal could be transmitted across single cells via intercellular communication in a skin disease model. This method was shown to have several inherent advantages. The porous pen can be fabricated efficiently using the fast LbL assembly technique. In addition, the chemical similarity and porous structure of a porous pen facilitate the loading of protein molecules. The number of molecules loaded can be tuned by varying the deposition time during LbL assembly. Furthermore, the loaded protein molecules can be deposited by PPN with negligible diffusion. Collectively, PPN provides new technical capabilities for plasma membrane drug delivery with single cell resolution and will enable investigation of dynamic single cell signaling in complex multicellular settings.

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fabrication of a porous pen.

All LbL films were assembled with a programmable Carl-Zeiss slide-stainer. The AFM probes were exposed to oxygen plasma generated by a Harrick plasma cleaner (Harrick Scientific Corporation, Boarding Ossining, NY) for 20 minutes, producing hydrophilic moieties and negative charges on the surface. After this, the AFM probes were mounted onto glass slides, and were dipped into PAH solution (without adjusting the pH) for 20 minutes to form the precursor layer, followed by three washing steps. The AFM probes were then introduced in the aqueous solution of PAA (pH = 3.5) for required deposition time, followed by three washing steps with DI water (pH = 3.5) for sufficient time. Subsequently, the probes were immersed in the PAH (pH = 8.5) aqueous solution with the same deposition time as PAA and washed again three times with DI water (pH = 8.5). The dipping process was repeated 20 times. In total, 20.5 bilayers were deposited on the AFM probes, including the first PAH precursor layer. Deposition time of 10 seconds, 1 minute and 5 minutes were applied in this work. The assembled polyelectrolyte multilayer films were immersed in water solution with pH of 2.0 for 5 minutes followed by washing with DI water (pH =5.5) for 5 minutes. After the porosity induction, the films were dried and then heated at 180 °C for 2 hours to cross-link the films preventing the porous structure from being distorted. A JEOL 6610LV Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was used to observe the porous thin films on the AFM cantilevers. All specimens were coated with gold before examination under the SEM.

Silanization of AFM cantilevers.

The AFM tips were washed in chloroform for 1 hour and air plasma cleaned. The tips were placed in a chamber with the presence of 45 μl (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES, Sigma Aldrich) and 15 μl triethylamine (TEA, Fisher) at room temperature for 1 hour. Then the tips were placed on a hot plate at 100 °C for 3 hours.

Loading of protein molecules.

The pathogenic anti-Dsg3 antibody Px4-3 (kind gift from Dr. Aimee Payne, University of Pennsylvania) was used and diluted PBS at 1:50 concentration (2.44 μg/ml). Both porous pens and silanized tips were immersed in the antibody solution. After loading antibodies, the porous pens were blocked with bovine serum albumin (BSA block) and then incubated in Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG solution (A11013, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The probes were immersed in PBS prior to use. The protein loaded AFM cantilevers were imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE300, Nikon Instruments Inc, Melville, NY) with Cool SNAP EZ CCD Camera (Photometries, Tucson, AZ) to determine the loading amount of protein molecules.

Characterization of diffusion release from porous pens.

Porous pens were incubated in the fluorescence antibody (A11013, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) (1:200) for 1 hour. After the removal of free protein molecules in the porous pen via rinsing three times in PBS, the porous pens were further incubated in PBS solution, and stored in a 4 °C refrigerator during the experiment. The fluorescent intensity on AFM cantilevers was monitored by the fluorescence microscope over time.

PPN experiment.

1N-[3-(trimethoxysilyl)propyl]ethylenediamine (TPEDA, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was mixed with ethanol with a volumetric ratio of 1:10. Plasma cleaned glass slides were immersed in the mixture for 30 minutes to form amino-terminated self-assembled monolayer. The modified glass slides were rinsed with ethanol and dried under Nitrogen. In the end, the modified substrates were placed in an oven at 60 °C for 1 hour to stabilize the monolayer. The amino-terminated substrates were used for contact release. Porous pens were first incubated in the florescent secondary antibody solution for 1 hour to stabilize protein adsorption. A micro-manipulator (Signatone S-926, Signatone Corporation, Gilroy, CA) was used to perform the contact release along with an optical microscope (Nikon TS 100, Nikon Instruments Inc, Melville, NY) for positioning. The protein loaded AFM probes were mounted onto the micro-manipulator, which allowed the contact of AFM tips with the amino-terminated substrates, forming a dot pattern of protein arrays. This pattern was recorded by the Nikon fluorescence microscope. The contact time was controlled to 15 seconds. Three experimental conditions were tested: direct PPN, rinse before PPN, and incubation before PPN. For contact detection, PPN experiment was also carried out on an AFM system (FlexFPM, Nanosurf). The contact force was recorded by the deflection of the AFM probe.

Cell culture.

human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT was used in this study. Cells were grown in DMEM medium (Gibco-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bio-products, West Sacramento, CA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (10,000 U/ml/10,000 μg/ml; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Imaging processing for porous structure analysis.

The SEM images were processed using Fiji, an open-source platform for biological-image analysis.[60] The images were smoothed to reduce the noise level. The images were then binarized. The thresholds for images were selected based on the gray scale value of these images. The images then processed with “Binary -> open” command to remove isolated pixels. After that, the images were processed via “Analyze Particle” command.

Delivering drug to plasma membrane.

The drugs, anti-Dsg antibody AK23, were loaded onto porous structured AFM probe as mentioned above. The human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT was grown to confluence and incubated with Fluo-4 AM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 hour before rinsing with PBS. Then the antibody loaded porous pen was mounted onto a robotic positioner and was located onto plasma membrane. The fluorescent signals were recorded via fluorescence microscopy.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Dr. Jing Yu is supported by “the MSU Foundation”. Dr. R. Yang acknowledges the funding from the Nebraska Center for Integrated Biomolecular Communication (NIH National Institutes of General Medical Sciences P20 GM113126). The authors thank Dr. Zhengbao Zha and Dr. Shengqiang Xu for their help on experimental designs.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Contributor Information

Dr. Yongliang Yang#, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA, ylyang@msu.edu

Dr. Jing Yu#, Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA

Amir Monemian Esfahani, Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, University of Nebraska -Lincoln, Lincoln, NE 68588, USA.

Prof. Kristina Seiffert-Sinha, Department of Dermatology, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York 14203, USA

Prof. Ning Xi, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA

Prof. Ilsoon Lee, Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA

Prof. Animesh A. Sinha, Department of Dermatology, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York 14203, USA

Dr. Liangliang Chen, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA

Dr. Zhiyong Sun, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA

Prof. Ruiguo Yang, Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, University of Nebraska -Lincoln, Lincoln, NE 68588, USA, ryang6@unl.edu

Prof. Lixin Dong, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA, ldong@egr.msu.edu

REFERENCES

- [1].Kensler TW, Wakabayashi N, Biswal S, Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 2007, 47, 89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Josic D, Clifton JG, Proteomics 2007, 7, 3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rask-Andersen M, Almén MS, Schiöth HB, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2011, 10, 579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Noack M, Miossec P, Autoimmun. Rev 2014, 13, 668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Heupel W-M, Zillikens D, Drenckhahn D, Waschke J, J. Immunol 2008, 181, 1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gumbiner BM, Cell 1996, 84, 345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Thoma CR, Zimmermann M, Agarkova I, Kelm JM, Krek W, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2014, 69-70, 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chow YT, Chen S, Wang R, Liu C, Kong C-W, Li RA, Cheng SH, Sun D, Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 24127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zhang Y, Yu L-C, Bioessays 2008, 30, 606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mhanna R, Qiu F, Zhang L, Ding Y, Sugihara K, Zenobi-Wong M, Nelson BJ, Small 2014, 10, 1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hu Q, Sun W, Lu Y, Bomba HN, Ye Y, Jiang T, Isaacson AJ, Gu Z, Nano Lett 2016, 16, 1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sun W, Ji W, Hu Q, Yu J, Wang C, Qian C, Hochu G, Gu Z, Biomaterials 2016, 96, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dupres V, Verbelen C, Dufrêne YF, Biomaterials 2007, 28, 2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dufrene YF, 2003, 6, 317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Alsteens D, Müller DJ, Dufrêne YF, Acc. Chem. Res 2017, 50, 924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ebner A, Wildling L, Zhu R, Rankl C, Haselgrübler T, Hinterdorfer P, Gruber HJ, Top Curr Chem 2008, 285, 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dai X, Moffat JG, Wood J, 2012, 64, 449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lal R, Ramachandran S, Arnsdorf MF, 2010, 12, 716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ruozi B, Tosi G, Leo E, 2007, 73, 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sitterberg J, Ozcetin A, Ehrhardt C, Bakowsky U, Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2010, 74, 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yang Y, Xi N, Sun Z, Basson M, Zeng B, Song B, Chen L, Zhou Z, in 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), IEEE, 2016, pp. 5285–5290. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dufrêne YF, Ando T, Garcia R, Alsteens D, Martinez-Martin D, Engel A, Gerber C, Müller DJ, Nat. Nanotechnol 2017, 12, 295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pfreundschuh M, Harder D, Ucurum Z, Fotiadis D, Müller DJ, Nano Lett 2017, 17, 3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Seiffert-Sinha K, Yang R, Fung CK, Lai KW, Patterson KC, Payne AS, Xi N, Sinha AA, PLoS One 2014, 9, e106895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Xi N, Fung CKM, Yang R, Lai KWC, Wang DH, Seiffert-Sinha K, Sinha AA, Li G, Liu L, Methods Mol. Biol 2011, 736, 485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ebner A, Hinterdorfer P, Gruber HJ, Ultramicroscopy 2007, 107, 922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Barattin R, Voyer N, Chem. Commun 2008, 1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kumar R, Ramakrishna SN, Naik VV, Chu Z, Drew ME, Spencer ND, Yamakoshi Y, Nanoscale 2015, 7, 6599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Senapati S, Lindsay S, Acc. Chem. Res 2016, 49, 503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hu KK, Bruce MA, Butte MJ, Immunol. Res 2014, 58, 211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Decher G, Science 1997, 277, 1232. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Richardson JJ, Björnmalm M, Caruso F, Science 2015, 348, aaa2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Mendelsohn JD, Barrett CJ, Chan VV, Pal AJ, Mayes AM, Rubner MF, Langmuir 2000, 16, 5017. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Fery A, Schöler B, Cassagneau T, Caruso F, Langmuir 2001, 17, 3779. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Cho C, Jeon J-W, Lutkenhaus J, Zacharia NS, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 4930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wu C-C, Xu H, Otto C, Reinhoudt DN, Lammertink RGH, Huskens J, Subramaniam V, Velders AH, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 7526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Piner RD, Zhu J, Xu F, Hong S, Mirkin CA, Science 1999, 283, 661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Yu J, Sanyal O, Izbicki AP, Lee I, Macromol. Rapid Commun 2015, 36, 1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hiller J, Mendelsohn JD, Rubner MF, Nat. Mater 2002, 1, 59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Berg MC, Zhai L, Cohen RE, Rubner MF, Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gribova V, Auzely-Velty R, Picart C, Chem. Mater 2012, 24, 854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Schneider A, Vodouhê C, Richert L, Francius G, Le Guen E, Schaaf P, Voegel J-C, Frisch B, Picart C, Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lo AS, Mao X, Mukherjee EM, Ellebrecht CT, Yu X, Posner MR, Payne AS, Cavacini LA, PLoS One 2016, 11, e0156800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Cranford SW, Ortiz C, Buehler MJ, Soft Matter 2010, 6, 4175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kuznetsova A, Yates JT, Liu J, Smalley RE, J. Chem. Phys 2000, 112, 9590. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Linsebigler AL, Smentkowski VS, Ellison MD, Yates JT, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1992, 114, 465. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ginger DS, Zhang H, Mirkin CA, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2004, 43, 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Rozhok S, Piner R, Mirkin CA, J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 751. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Jang J, Hong S, Schatz GC, Ratner MA, J. Chem. Phys 2001, 115, 2721. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Jang J, Schatz GC, Ratner MA, J. Chem. Phys 2002, 116, 3875. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Payne AS, Ishii K, Kacir S, Lin C, Li H, Hanakawa Y, Tsunoda K, Amagai M, Stanley JR, Siegel DL, J. Clin. Invest 2005, 115, 888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Amagai M, Tsunoda K, Zillikens D, Nagai T, Nishikawa T, J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 1999, 40, 167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Broussard JA, Yang R, Huang C, Nathamgari SSP, Beese AM, Godsel LM, Hegazy MH, Lee S, Zhou F, Sniadecki NJ, Green KJ, Espinosa HD, Mol. Biol. Cell 2017, DOI 10.1091/mbc.E16-07-0520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Di Zenzo G, Amber KT, Sayar BS, Müller EJ, Borradori L, Semin Immunopathol 2016, 38, 57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Giordano CN, Sinha AA, Autoimmunity 2012, 45, 427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Koga H, Tsuruta D, Ohyama B, Ishii N, Hamada T, Ohata C, Furumura M, Hashimoto T, Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2013, 17, 293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Hashimoto T, Arch Dermatol Res 2003, 295 Suppl 1, S2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Junkin M, Lu Y, Long J, Deymier PA, Hoying JB, Wong PK, Biomaterials 2013, 34, 2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Tsutsumi M, Inoue K, Denda S, Ikeyama K, Goto M, Denda M, Cell Tissue Res 2009, 338, 99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez J-Y, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A, Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.