Abstract

PURPOSE

In recognition of the growing burden of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), including cancer, we assessed the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of rural women in low-resourced countries toward common NCDs and the barriers they face in receiving NCD early detection services.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The study was conducted in a rural block of India using the Rapid Assessment and Response Evaluation ethnographic assessment, which included in-depth interviews of key health officials; focus group discussions with women, men, teachers, and health workers from the block; and a knowledge, attitudes, and practices questionnaire survey. The home-based survey was conducted among 1,192 women selected from 50 villages of the block using a two-stage randomization process and stratified to 30- to 44-year and 45- to 60-year age-groups.

RESULTS

Our study revealed low awareness among women with regard to tobacco as a risk factor; hypertension, diabetes, and cancer as major health threats; and the importance of their early detection. Only 4.8% of women reported to have ever consumed tobacco, and many others consumed smokeless tobacco without knowing that the preparations contained tobacco. Only 27.3% and 11.5% of women had any knowledge about breast and cervical cancer, respectively, and only a few could describe at least one common symptom of either cancer. Self-reported diagnosis of hypertension and diabetes was significantly lower than the reported national prevalence. Only 0.9% and 1.3% of women reported having had a breast examination or gynecologic checkup, respectively, in the past 5 years. Low female empowerment and misconceptions were major barriers.

CONCLUSION

Barriers need to be addressed to improve uptake of NCD early detection services.

INTRODUCTION

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) accounted for two thirds of deaths (34.5 million of a total 52.8 million) worldwide in 2010.1 In the same year, cancer was responsible for 8 million deaths, ischemic heart disease and stroke collectively for 12.9 million deaths, and diabetes for 1.3 million deaths, with all showing significant rising trends.

CONTEXT SUMMARY

Key Objective To assess the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of rural Indian women toward common noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and the usual barriers they face in receiving early detection and treatment services for common NCDs.

Knowledge Generated The study was conducted among rural women who reside in a hard-to-reach area in western India. Low awareness among the study population of NCDs, their early detection, and risk factors and poor social empowerment of women can be major barriers to accessing NCD prevention and early detection services. Some of the structural barriers the population faces for accessing NCD control services are distance to the primary health centers, lack of amenities, and poor quality of services. The habit of chewing various smokeless tobacco products was highly prevalent.

Relevance The recently launched comprehensive NCD control program in India needs to address these issues.

The government of India launched a revamped NCD control program in 2016, which aims to screen men and women for hypertension, diabetes, and oral cancer and women for breast and cervical cancers.2 Great inequity exists in the delivery of health care in India, particularly within the rural population.3 Women in developing countries like India are victims of the worse deprivation as a consequence of poor empowerment and discriminatory beliefs and practices.4,5 With recognition of the challenges of implementing an NCD control program in a resource-limited country like India, Krishnan et al6 recommended a study to assess the social, cultural, and behavioral factors that might influence the uptake of NCD control services as an implementation research priority. We undertook the community-based study to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of rural women toward the prevention and early detection of common NCDs. The information and evidence gathered were expected to identify some of the social barriers to successful implementation of NCD programs that target rural women in India as well as in other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Setting

The study was conducted in the Gogunda rural block of Udaipur District, Rajasthan, India. The block is situated approximately 100 km away from the district headquarters and has a total population of 186,311 distributed in 228 villages.7 The block, inhabited predominantly by tribal populations, is considered as one of the backward rural districts because of the semi-arid landscape, poor agricultural outputs, and high level of poverty. GBH Memorial Cancer Hospital, Udaipur, India, collaborated with the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Lyon, France, to implement the study.

Data Collection Methods

Three different methods were used to collect data. These included key informant interviews (KIIs) that involved an official from the Ministry of Health, a local elected people’s representative, a local general practitioner, a medical specialist from the local secondary health facility, and a representative from a local civil society organization; focus group discussions (FGDs) that involved 16 local women and 15 local men 30 to 60 years of age, two local community health workers (CHWs), a local school teacher, and two volunteers from a civil society organization; and a structured knowledge, attitudes, and practices questionnaire survey of women 30 to 60 years of age that focused on hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, breast cancer, and cervical cancer. A more-detailed description about how these methods were used is provided in the Data Supplement. Verbal consent was obtained from all participants. The FGDs were conducted in the local language, and both KIIs and FGDs were audio recorded.

The study, conducted between January 2017 and October 2017, was approved by the ethics committees of IARC and GBH Memorial Cancer Hospital. The KII and FGD outcomes were recorded in MS Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) files that were stored along with the audio recordings in password-protected computers at the project site. The completed questionnaires were entered into a password-protected database hosted on an IARC server.

Statistical Analysis

The investigators abstracted the themes related to the barriers to accessing NCD services after repeated reading, comparison, and analysis of the KII and FGD reports. These themes were listed and organized into categories for reporting. For the questionnaire survey, we present the distribution of participant sociodemographic, reproductive characteristics, and tobacco and alcohol consumption as numbers and proportions. Also presented as numbers and proportions are the respondents’ general knowledge and attitudes related to the harms of tobacco and alcohol use and the common NCDs. Statistical analysis was carried out using Stata 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) software.

RESULTS

Outcomes of KIIs and FGDs

The FGDs and KIIs were transcribed from the audio recordings and translated into English. There was a marked lack of awareness about the risk factors of NCDs and the importance of their early detection among the FGD participants. Some awareness existed about hypertension, which was believed to be related to stress, and about diabetes, which was believed to be a result of excessive consumption of sugar. Although very few of the participants had any knowledge of the risk factors associated with cancer or the tests available for early detection, most expressed fear of the disease. Cancer was associated with death and seen as a divine punishment for sins committed in a past life.

Most women said that they were too ashamed to discuss any female health problems with men. They would prefer to consult the village faith healer rather than seek help from their husbands or other male family members. It was a common belief that sickness was caused by someone casting an evil eye and that only the faith healers could remove the influence. Many of the FGD participants perceived cancer to be contagious. As quoted from a woman at an FGD:

My mother-in-law had vaginal discharge but refused to see anyone other than the faith healer. Finally, we took her to the hospital, but it was too late. She died within a month of us taking her to the hospital. She had constant foul-smelling discharge but would not let me clean her up. She was worried I would contract her disease by touching her.

Most participants were aware that tobacco consumption was harmful, with some even being aware that habitual users had trouble opening their mouth or could get oral cancer. However, that knowledge did not deter them from consuming tobacco. There were several misconceptions about the possible link between tobacco and cancer. As quoted from a school teacher:

My uncle had oral cancer even though he never consumed tobacco. When we took him to the cancer hospital, the other patients told us that they were fine as long as they smoked or chewed tobacco. They got cancer only after they quit.

Smoking beedis (handmade cigarettes) was the most popular way of tobacco consumption among men, whereas women preferred to rub mishri (tobacco paste) on their gums. The CHWs were seen as a trusted source of health care guidance and information. They were trained at the local primary health center (PHC) to educate the villagers about the ill effects of tobacco. However, their advice was not taken seriously by the majority of the population. They were not provided with any educational tools (flipcharts, posters, etc) to create awareness. As quoted from a CHW:

Even if I tell a pregnant woman to stop consuming tobacco, she refuses, saying that is the only way she can keep her bowel movements regular.

The women rarely consumed alcohol because alcohol drinking was considered a habit only appropriate for men. The men commonly consumed the locally produced drinks with high alcohol content.

The poor empowerment of women was reflected in their health seeking behavior. Women needed permission from their husband or father-in-law to visit the physician. They had to be accompanied by husbands or other males. According to the men, this was because the women were uneducated and unable to travel or navigate the health care system on their own. Given that most men were daily wage earners, they could not afford to take the day off to accompany the women, and this often resulted in a delay in seeking medical care.

The health administrators and clinician working at the PHC informed that an NCD detection clinic was held at the PHC once a month. However, there was no sustained effort to create awareness about the clinic. Even the CHWs and the elected representatives did not know of the NCD clinic. In fact, the FGD participants complained of the lack of facilities at the PHC. The PHC often runs out of medicines and refers patients to the district hospital much farther away. As quoted from a male FGD participant:

Whenever we go to the PHC, they never treat us; they just give a referral note to go to the district hospital.

The local PHCs and the district hospitals had very limited capacity to diagnose cancers early and had no facilities to treat them. The only hospital with comprehensive cancer treatment facilities was situated in the capital city, and it took the villagers almost a full day to travel.

Outcomes of the Questionnaire Survey

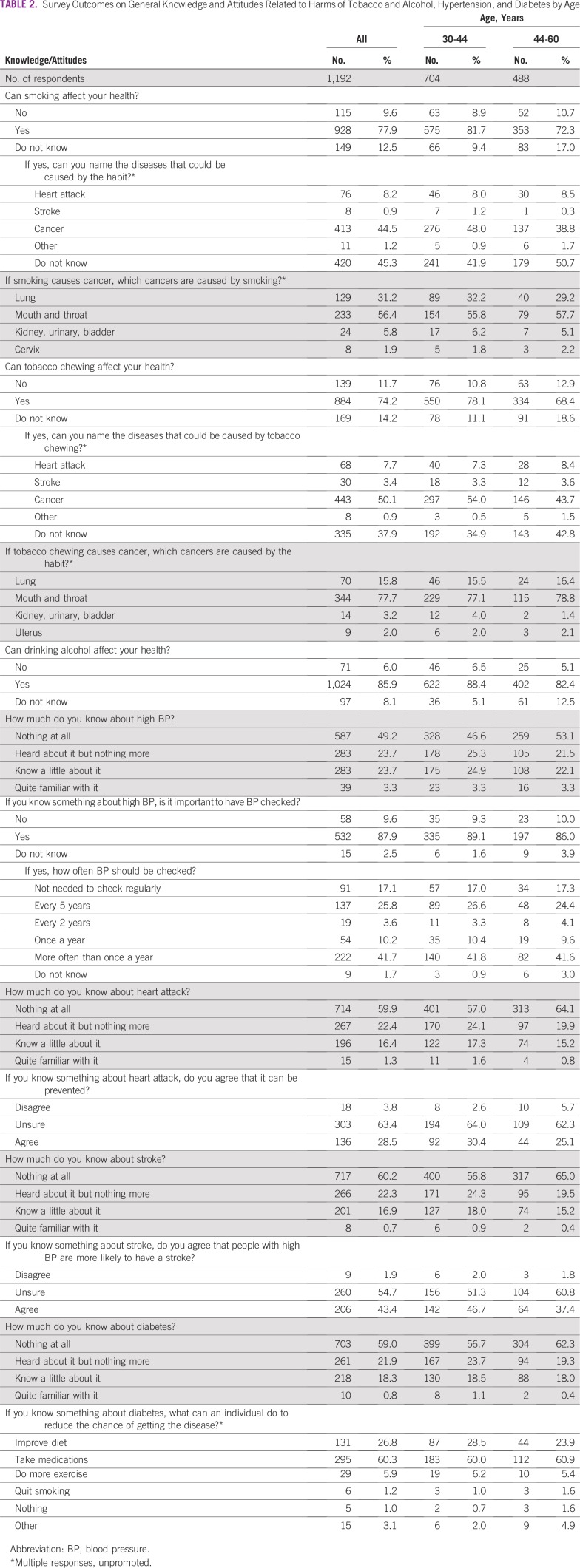

The questionnaires were satisfactorily completed by 1,192 women. The sociodemographic details of the respondent are listed in Table 1. The majority of the women were indigent and had low literacy. Only 4.8% reported to had ever chewed tobacco, which was likely an under-reporting. We came to know from the FGDs that the majority of women were unaware that the frequently used chewable preparations (eg, gutkha, zarda, and mishri) contained tobacco.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Questionnaire Survey Respondents

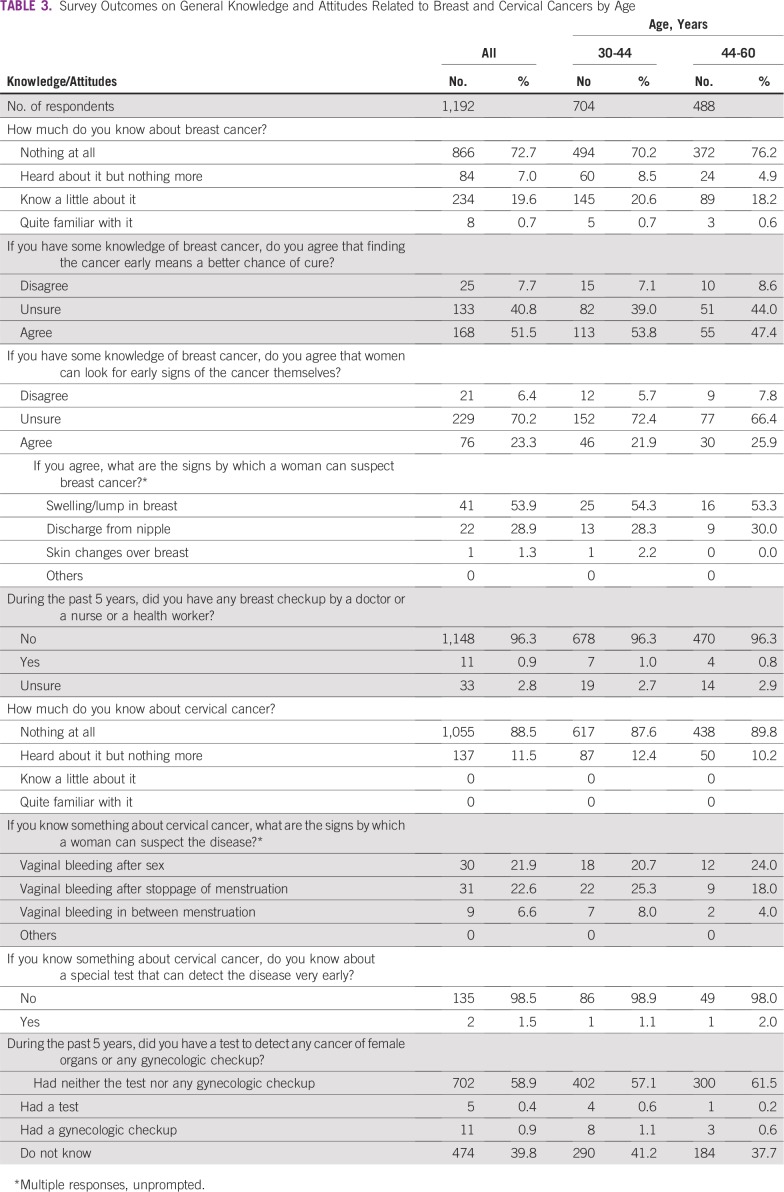

The knowledge of the respondents about tobacco and alcohol as risk factors and the level of awareness about early detection of hypertension and diabetes are listed in Table 2. The majority (younger, 81.7%; older, 72.3%) responded that smoking was harmful, although nearly one half of them did not know the diseases that could be caused by smoking. Nearly one third of respondents were aware of the link between smoking and cancer. Very few knew that smoking could increase the risk of heart attack or stroke. The level of awareness was poorer in the older women. Similar responses were elicited when the women were asked about the relationship between tobacco chewing and various diseases; 74% women knew that tobacco chewing was harmful. Only one half of them also knew that tobacco chewing could increase the risk of cancer. The majority of these women (77.7%) identified mouth and throat as the major sites for cancer in tobacco chewers. Alcohol was considered to be injurious to health by 85.9% of the women.

TABLE 2.

Survey Outcomes on General Knowledge and Attitudes Related to Harms of Tobacco and Alcohol, Hypertension, and Diabetes by Age

Only one half of the respondents (50.8%) knew about high blood pressure (BP) as a disease or had ever heard of it. Among those who knew about the disease, 87.9% agreed that routine checking of BP was beneficial, although there was a wide range of opinion on the appropriate frequency of checkup. Nearly 60% of the women never heard of heart attack or stroke. Only a minority of the women who had heard of heart attack or stroke agreed that the diseases could be prevented by controlling high BP.

Diabetes as a disease was known to only 43.3% of the younger women and 37.7% of the older women. Nearly one quarter of the women who had at least heard of the disease responded that the risk of diabetes could be reduced by improving diet. However, only 5.9% knew that physical activities could also reduce the risk.

The women who knew about diabetes and/or hypertension were asked whether they had either of the diseases. Only 0.3% of the younger women and 1.2% of the older women responded affirmatively.

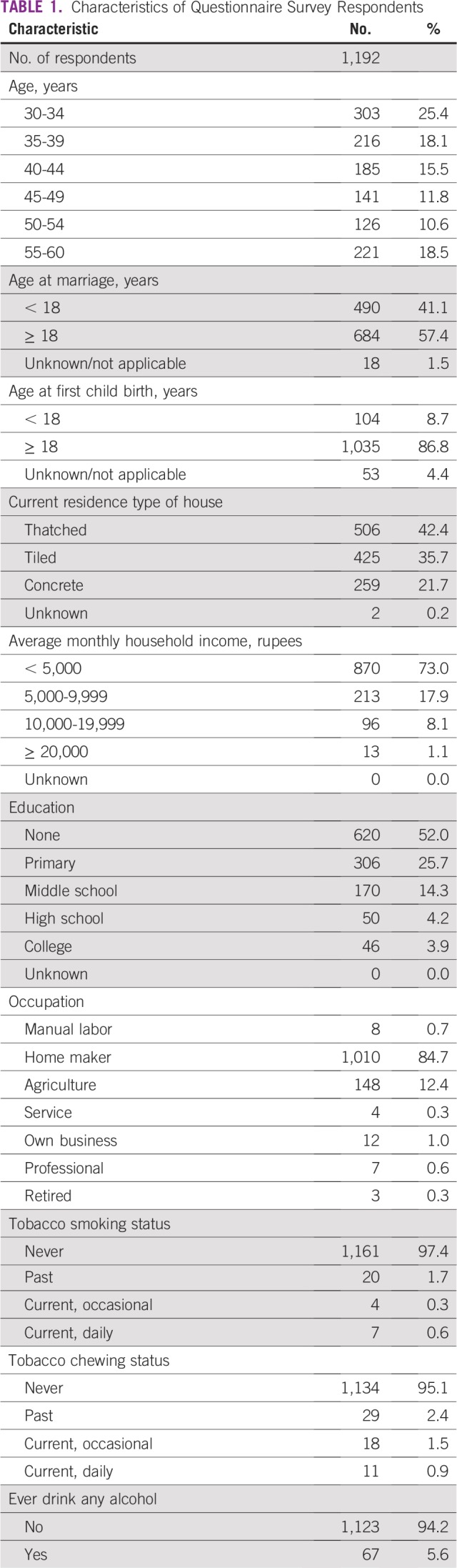

Responses to the questions related to breast and cervical cancer are listed in Table 3. Only 27.3% and 11.5% of the respondents had any knowledge about breast and cervical cancers, respectively. Among the small number of women who had some knowledge of breast cancer, only one half (51.5%) agreed that the disease could be cured if detected early, and very few could describe at least one symptom. Of the total 137 women who knew something about cervical cancer, only 70 (51.1%) could describe at least one symptom. Only 0.9% of the respondents had a breast examination by a health provider and only 1.3% had at least a gynecologic checkup in the past 5 years.

TABLE 3.

Survey Outcomes on General Knowledge and Attitudes Related to Breast and Cervical Cancers by Age

DISCUSSION

Our study highlights the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of the rural Indian population with regard to the common NCDs and identifies some of the social and structural barriers to accessing NCD control services. Although our study primarily focused on women, we learned some useful information about the beliefs and attitudes of the men that could be restrictive and prevent women from accessing available services.

The majority of the participating women had some limited knowledge of the harmful effects of tobacco. Although the prevalence of smoking among these rural women was significantly less than that reported earlier among urban Indian women (6.5%), the use of various forms of smokeless tobacco was common in the rural women and the majority were unaware of the nature of the contents.8 In our survey, almost all the women with some knowledge of the harmful effects of tobacco linked the habit to cancer only. Recently, cardiovascular diseases like ischemic heart disease and stroke were observed as responsible for more than one quarter (28.1%) of the deaths in India in 2016.9 There is evidence that long-term use of smokeless tobacco increases the risk of fatal myocardial infarction and stroke.10 The population should be made aware of the harmful effects of smoking as well as of smokeless tobacco use.

The prevalence of hypertension can be reduced and eligible people with hypertension can be provided treatment only if the population is well aware of the disease and has access to early detection and treatment services. Our survey revealed that nearly one half of the women knew about hypertension but had very limited knowledge about the necessity of regular checkups. Our finding is consistent with that of a meta-analysis that reported the awareness of BP in rural India to be only 25.1%, which is significantly lower than in urban India (41.9%). The level of awareness directly correlated with compliance with treatment and control of BP.11 The very low rate of self-reported hypertension among our survey respondents compared with the hypertension prevalence reported by the WHO STEPS (STEPwise Approach to Chronic Disease Risk Factors Surveillance) survey in the adult Indian population (40.1%) makes it obvious that very few women ever have had their BP checked.12

Awareness about diabetes among rural Indian women was even lower than that about hypertension. Very few of them knew about the benefits of regular exercise to prevent or control diabetes. A study conducted among adult populations selected from 188 urban and 175 rural areas of India reported that only 46.7% of males and 39.6% of females knew about a condition called diabetes.13 Like us, this study also observed very low awareness of prevention of diabetes through lifestyle modifications. The low self-reported prevalence of diabetes in our survey participants, as opposed to a 14.3% prevalence reported by the WHO STEPS survey, highlight the large number of undiagnosed individuals with diabetes in the population.12

Our study reveals not only poor awareness of either of the two common cancers among the women participants but also the misconceptions and stigma associated with the disease, which may prevent women from seeking appropriate care. Equating cancer with death, stigmatizing the disease as a consequence of past sins, or labeling cancer as a contagious disease can make women shy away from timely consultation and treatment. Such misconceptions compounded by poor access to effective health care lead to the late diagnosis of breast and cervical cancers and poor survival in rural populations.14,15 Participation in screening will be affected unless these myths and misconceptions are dealt with through appropriate communication strategies. The fear of getting a cancer diagnosis and fatality associated with cancer, and unwillingness to undergo a gynecologic examination are major barriers to the uptake of cancer screening reported in other Indian studies.16

In recognition of the growing burden of NCDs, the World Health Assembly adopted a global action plan for the prevention and control of NCDs in May 2013.17 The action plan aims to achieve a 25% relative reduction in overall NCD mortality by 2025.18 Many LMICs, like India, initiated comprehensive NCD control programs aligned to the global action plan. However, huge inequity in accessing NCD prevention and early detection services has been reported in the LMICs, especially in the rural areas.19 Poor infrastructure, low quality of services, inadequate manpower, and difficult geographic landscape are all factors that limit access. Rural women are the victims of worse deprivation that results from poor empowerment and low priority given to their health issues.20 Other key factors that influence uptake of services are the level of awareness about NCDs and their risk factors and the attitude toward preventive health interventions. Our study of rural indigent women who reside in a hard-to-reach area of India highlights the major barriers to accessing NCD control services, which are low empowerment of women, poor availability of services, a low level of awareness about NCDs, and a lack of a preventive health orientation.

The major limitation of our study is that the population was highly selective; thus, one can argue that the results are not generalizable. However, nearly 70% of the population in India live in rural areas and approximately 25% of the rural population live below the poverty line with limited access to services, including health care.21 Lack of awareness and insufficient health care access are common problems in India that lead to late diagnosis of chronic diseases.9 Organization of health care around the principles of universal coverage to ensure availability of good-quality services to all is key to minimizing health disparities. As a signatory to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, India needs to implement tobacco control strategies more stringently and regulate the sale of smokeless tobacco products. In accordance with national NCD control guidelines, rural CHWs need to be trained and empowered to raise awareness in the community.22 A culturally appropriate and broad-based communication strategy to educate the community will help to overcome some of the identified barriers. The low social empowerment of women needs to be addressed.

Footnotes

Presented at The First World Noncommunicable Diseases Congress 2017, Chandigarh, India, November 4-6, 2017.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Manoj Mahajan, Nilesh Patira, Sangita Prasad, Eric Lucas, Faeeza Faruq, Rengaswamy Sankaranarayanan, Swami Iyer, Partha Basu

Administrative support: Manoj Mahajan, Nilesh Patira, Sangita Prasad, Eric Lucas, Faeeza Faruq, Swami Iyer

Provision of study material or patients: Manoj Mahajan, Nilesh Patira, Sangita Prasad, Sushma Mogri, Eric Lucas

Collection and assembly of data: Manoj Mahajan, Navami Naik, Kirti Jain, Nilesh Patira, Sushma Mogri, Eric Lucas, Swami Iyer, Partha Basu

Data analysis and interpretation: Manoj Mahajan, Navami Naik, Kirti Jain, Richard Muwonge, Eric Lucas, Faeeza Faruq, Rengaswamy Sankaranarayanan, Swami Iyer, Partha Basu

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jgo/site/misc/authors.html.

Faeeza Faruq

Employment: Aveanna Healthcare (I)

Swami Iyer

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Takeda Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Roche (Inst), Incyte (Inst), Arog Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al: Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380:2095-2128, 2012 [Erratum: Lancet 381:628, 2013] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Health Mission, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India: Operational Guidelines. Prevention, Screening and Control of Common Non-Communicable Diseases: Hypertension, Diabetes and Common Cancers (Oral, Breast, Cervix). http://www.nicpr.res.in/images/pdf/guidelines_for_population_level_screening_of_common_NCDs.pdf.

- 3.Reddy KS. Health care reforms in India. JAMA. 2018;319:2477–2478. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.5284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knaul FM, Bhadelia A, Gralow J, et al. Meeting the emerging challenge of breast and cervical cancer in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;119:S85–S88. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balarajan Y, Selvaraj S, Subramanian SV. Health care and equity in India. Lancet. 2011;377:505–515. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61894-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krishnan S, Sivaram S, Anderson BO, et al. Using implementation science to advance cancer prevention in India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:3639–3644. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.9.3639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation: Integrated Management Information System (IMIS). http://indiawater.gov.in/imisweb/RwsMain.aspx?aspxerrorpath=/IMISWeb/Reports/rws/rpt_PresentPopulationBlockwise.aspx.

- 8.Krishnan A, Ekowati R, Baridalyne N, et al. Evaluation of community-based interventions for non-communicable diseases: Experiences from India and Indonesia. Health Promot Int. 2011;26:276–289. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daq067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arokiasamy P. India’s escalating burden of non-communicable diseases. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e1262–e1263. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piano MR, Benowitz NL, Fitzgerald GA, et al. Impact of smokeless tobacco products on cardiovascular disease: Implications for policy, prevention, and treatment: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122:1520–1544. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181f432c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anchala R, Kannuri NK, Pant H, et al. Hypertension in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence, awareness, and control of hypertension. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1170–1177. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thakur JS, Jeet G, Pal A, et al. Profile of risk factors for non-communicable diseases in Punjab, Northern India: Results of a state-wide STEPS survey. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deepa M, Bhansali A, Anjana RM, et al. Knowledge and awareness of diabetes in urban and rural India: The Indian Council of Medical Research India Diabetes Study (phase I): Indian Council of Medical Research India Diabetes 4. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18:379–385. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.131191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malvia S, Bagadi SA, Dubey US, et al. Epidemiology of breast cancer in Indian women. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2017;13:289–295. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thulaseedharan JV, Malila N, Swaminathan R, et al. Survival of patients with cervical cancer in rural India. J Clin Gynecol Obstet. 2015;4:290–296. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basu P, Sarkar S, Mukherjee S, et al. Women’s perceptions and social barriers determine compliance to cervical screening: Results from a population based study in India. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30:369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Health Organization: Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18. World Health Organization: Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao N, Long Q, Tang X, et al. A community-based approach to non-communicable chronic disease management within a context of advancing universal health coverage in China: Progress and challenges. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-S2-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vissandjée B, Barlow R, Fraser DW. Utilization of health services among rural women in Gujarat, India. Public Health. 1997;111:135–148. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3506(97)00572-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The World Bank India’s Poverty Profile. http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/infographic/2016/05/27/india-s-poverty-profile

- 22. World Health Organization-Government of India Biennium Work Plan 2016: Reducing Risk Factors for Noncommunicable Diseases (NDCs) in Primary Care. Training Manual for Community Health Workers. Bangalore, India, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, 2016.