Abstract

Stunted growth in children and multisectoral action to address it are dominant ideas in the international nutrition community today, and this study finds that these ideas are increasingly evident over time in nutrition policy in Zambia, with stunting largely displacing other framings of nutrition. This study is based on key informant interviews (70 interviews with 61 interviewees), policy document review, and social network mapping, with iterative data collection and analysis taking place over 6 years (2011–2016). Analysis was based on two established political science theories: policy transfer theory and the Advocacy Coalition Framework. Policy changes in Zambia are shown to result from the international community’s nutrition agenda, transferred to national policy through the normative promotion of certain ways of understanding the issue of malnutrition, largely propagated through advocacy, technical assistance and funding. With its focus on multisectoral action to reduce stunting, the recent nutrition policy narrative impinges directly on an existing food security narrative as it attempts to alter agriculture policy away from maize reliance. The nutrition policy sub-system in Zambia is therefore split between an international coalition promoting action on child stunting, and a national coalition focused on food security and hunger, with implications for both sides on progressing a coherent policy agenda. This study finds that it is possible to understand policy processes for nutrition more fully than has so far been achieved in much nutrition literature through the application of multiple political science theories. These theories allow the generalization of findings from this case study to assess their relevance in other contexts: the study ultimately is about the transfer of policy being explained by the presence of advocacy coalitions and their different beliefs, resources and power, and these concepts can be investigated wherever the nutrition system reaches down from international to national level.

Keywords: Advocacy coalitions, policy transfer, nutrition policy, Zambia

Key Messages

Nutrition policy ideas of multisectoral approaches to stunting reduction have been transferred from international realms to Zambian national policy processes by international organizations working at both levels.

In Zambia, a nutrition advocacy coalition has been met by an established food security coalition promoting opposing policies, with implications for both sides on progressing a coherent policy agenda.

Both hunger and stunting remain important issues in Zambia, and common ground should be found to work on both issues through explicitly recognizing these coalition divisions and finding more inclusive forms of policy practice, perhaps with a focus on quality diets.

Combining political science theories of policy transfer and advocacy coalitions sheds new light on nutrition policy processes, and tests these theories in new contexts.

Introduction

Malnutrition in all its forms is a significant development issue. Probably the most recognized form of malnutrition is hunger, technically known as undernourishment, defined as not having enough energy (calories) available from food each day for an active life. Beyond hunger, the major international preoccupation is with child stunting, or low height for a child’s age, which is associated with poor health and productivity outcomes in later life (Black et al., 2008). Globally, hunger affects almost 1 billion people and child stunting affects 150 million children, and malnutrition underpins many persistent health and social challenges (Development Initiatives, 2018). In Zambia, per-capita availability of total calories has worsened slightly over time as population growth outstrips production, with 48% of the population currently classified as hungry, particularly in lean agricultural periods of the year (FAO, 2016), putting Zambia close to the bottom of global hunger rankings (von Grebmer et al., 2017). Stunting rates are also very high at 40% of children under age 5 (Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Health, Tropical Diseases Research Centre, University of Zambia and Macro International Inc., 2014), which is significantly higher than the Southern African regional average of 23%.

There is therefore a need to better address malnutrition, both globally and in Zambia specifically, and part of this response will be through national policy. Nutrition as a policy issue sits at the intersection of the food and health sectors. Action in both of these areas is necessary but not sufficient to address nutrition issues; if nutrition is not also addressed explicitly, it often gets lost between its two larger policy cousins. The inherent multisectorality of nutrition across these sectors means that more than the usual number of stakeholders are likely to be involved in nutrition policy processes, with more diverse ideas and approaches than would be usual for a single-sector issue. This speaks to the importance of understanding policy processes affecting the issue of nutrition in different contexts, to improve our insight into how multiple sectors interact both politically and practically, to more effectively address nutrition as a policy and development issue.

Researchers have in recent years started to build a body of work on nutrition policy processes, but there has been relatively little empirical political analysis in this field to date. Normative work elaborating practical recommendations explicitly focused on nutrition policy processes, but not based on established policy science theories or frameworks, started to emerge after 2000, with operational findings on the need for improved capacity, commitment and collaboration in the nutrition sector (Gillespie et al., 2003; Heaver, 2005; Engesveen et al., 2009; Haddad, 2013). Only in the last 10 years or so has nutrition policy process work emerged that has a foundation in established policy science and empirical studies of national policy processes (Natalicchio et al., 2009; Pelletier et al., 2012; Reich and Balarajan, 2012; Acosta and Haddad, 2014; Balarajan and Reich, 2016; Harris et al., 2017b; Thow et al., 2018). Recent synthesis work has concluded that while the research focus on nutrition governance is growing, much political work in this field lacks theoretical depth and conceptual rigour, and has yet to contribute a great deal to the political science or development studies fields more broadly (Nisbett et al., 2014; Bump, 2018). To start to address this gap, this article takes the case of nutrition policy in Zambia, tracing its history and teasing out the actors, narratives and politics underlying policy change over the past decade.

Aims and approach

This study was undertaken as a piece of doctoral research and evolved over 6 years from 2011 to 2016 as both the Zambian context and the researcher’s familiarity with this context changed, following actors and events as they moved. The aim of this study, emerging after 2 years of exploratory research to understand the policy context, was to investigate how and why certain international nutrition ideas and approaches have found their way into national nutrition policy and practice in Zambia. The locus of the study is therefore the spaces between the national and international policy worlds, between which policy ideas travel. The study contributes, though investigation of the case of nutrition policy in one country, to an understanding of policy processes in low-income countries more generally.

Data collection

To approach this issue, data were collected from district, national and international levels over the course of the study. All data collection with the exception of the NetMap interview (which was undertaken by a qualified consultant) and all analysis were undertaken by the author. Ethical approval for this research was obtained through the University of London (SOAS) review board, and the University of Zambia review board. Free and informed consent of all research participants was obtained and documented.

A key data source was in the form of semi-structured key informant interviews (KII; 70 interviews with 61 different respondents over 6 years). Nationally, the nutrition policy stakeholder group in Zambia is active but not large. Over the 6 years of the study, a comprehensive list of national actors in the Zambian nutrition policy landscape was compiled for this study from a combination of meeting and workshop minutes, conference and event attendance lists, and professional interactions. Interviews were sought with those actors from this list who were active in the creation and implementation of nutrition policies and the shaping of the national nutrition agenda, with purposive sampling across a range of actor types (see Table 1). All national interviews were undertaken in person in English (the working language of government in Zambia) generally in the offices of the interviewees. Some of the international interviews were undertaken using Skype. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by professional transcribers for analysis.

Table 1.

Interview sources

| Interview source | Number of interviews | Interview source | Number of interviews |

|---|---|---|---|

International actors

|

|

National actors

|

|

International actors with strong links to Zambia

|

|

Local actors

|

|

| Total | 70 | ||

In addition, documents of several types provided data on which parts of this study were based: published academic literature, as well as providing background to the study as a whole, was used in parts of the research to trace the history of the field of nutrition and evolving narratives and agendas; international donor policies and strategies relating to nutrition provided evidence as to the changing priorities of the international nutrition community; and national policy and strategy documents showed how nutrition has been addressed in Zambia. All available Zambian national nutrition policy and strategy documents dating back to Zambian independence in 1964 were reviewed to understand changes in policy focus over time.

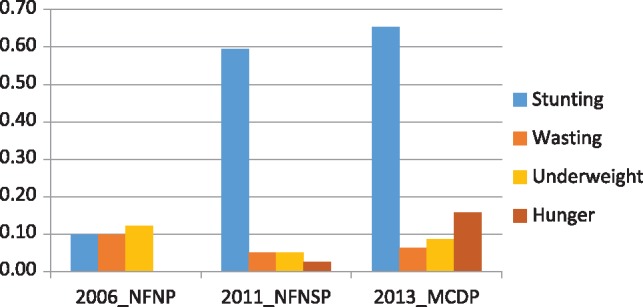

A final data source was a social network map created using the NetMap method (Schiffer, 2007). The method involves the facilitation of respondents in creating drawn maps of actors in a policy network and their connections, and assigning relative influence to these actors based on the respondents’ understanding of the network. In this case, respondents were in a single group interview bringing together a cross-section of interviewees from Table 1, explicitly including active stakeholders in nutrition policy. This was undertaken at national level in 2015 to gain a view of organizations involved in nutrition-relevant policy and action, as well as their influence over the issue of nutrition policy, and links of accountability between organizations, to understand how the distinct actors are connected.

Data analysis

Initial investigations (including interview guides and broad directions of enquiry) were informed by a guiding framework from the health policy literature focusing on the agenda-setting stage of the policy process (Shiffman, 2007; Shiffman and Smith, 2007). Primary thematic analysis of interviews was through coding using Nvivo 11 software (QSR International), including the use of memos to note emerging themes and ongoing analytical thoughts. Initial themes were taken directly from the guiding framework, essentially as a list of primary codes into which the raw data could be parcelled to start to break it into manageable chunks (for instance, under the parent-code ‘ideas and issue framing’, child-codes included ‘norm promotion’ and ‘internal frame’). Codes were also derived in vivo from the data itself as new concepts arose in the course of fieldwork and analysis (for instance under the same parent-code ‘ideas and issue framing’ the child-code ‘history’ was added; and a new parent-code ‘power’ was added). Coding was undertaken periodically throughout the middle years of the study, with emerging trends and findings then followed up in later interviews. The work was therefore iterative, with data collection and analysis continuing over the 6 years of the study.

Analysis of documents included simple word counts to assess the prominence of different concepts, and narrative synthesis whereby commonalities and changes among the written content in different documents over time were identified and summarized. Word counts searched for root words to find all mentions of relevant concepts (e.g. ‘stunt’ would find both ‘stunting’ and ‘stunted’).

The 2015 NetMap group interview was turned into a visual network map using Visualyzer™ software (SocioWorks). Network analysis was based on nodes (the different actors) and links (the relations between the actors), as well as being able to show visually other elements that describe the actor or organization being shown (such as sector) (Hanneman and Riddle, 2005). The phenomenon of power is shown in network analysis in various ways, primarily by the position of an actor in the network and so the access he has to others in the network; the number of inward accountability links; and the influence assigned to an actor by those elaborating the network with insider knowledge of the network (Schiffer and Waale, 2008; Hafner-Burton et al., 2009). Organizations involved in food and nutrition policy, links of accountability, and attribution of relative influence were added by consensus in the group NetMap interview, and the resulting network map reflects the agreed views of key respondents from a range of organizations involved in nutrition issues at the national level.

A final round of analysis involved bringing all of the different analyses and syntheses of the different data sources together to identify recurrent or important themes to build a grounded explanation of how and why certain international nutrition ideas and approaches have found their way into national nutrition policy and practice in Zambia. As the data were explored and synthesized together, a concurrent reading of the public policy theory literature suggested several different ideas that might shed theoretical light on the emerging empirical findings. In the absence of a single, unifying theory of public policy, Cairney (2013) suggests that combining the insights of multiple theories may produce new perspectives and new research agendas that bring fresh understanding to policy process issues. This study eventually applied two theories which together explained the phenomena being observed and documented through the empirical research: the theory of policy transfer (Dolowitz and Marsh, 1996) explained the movement of ideas, norms, behaviours and discourses between policy domains, including between international and national levels of governance. The Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF; Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith, 1993) charted the hierarchical belief systems, resources and strategies of actors within the Zambian policy sub-system (a grouping of experts and interested parties working on a specialist policy issue in a given sector) in order to identify actor groupings with similar beliefs and policy positions which were advocating in similar directions on policy issues.

Findings

Transferring ideas: setting the agenda

The issue of hunger has been a dominant nutrition concept globally since at least the 1940s (Harris, unpublished). In recent decades however, a large part of the nutrition community internationally has sought to distance itself from the idea of hunger in order to look at outcomes beyond simply calories, incorporating the tracking of broader diet and malnutrition outcomes particularly in children. Internationally, the ideas defining the nutrition sector have changed over several decades and have consolidated over the past 10 years or so to focus on a single nutrition outcome: child stunting, or low height for a child’s age [height-for-age z-score of more than two standard deviations below the defined mean of a healthy reference population (WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group, 2006)]. Focus on the idea of child stunting is relatively new internationally, and a narrative defining the toll of stunting on economic and human development has been the major rationale for the rise of this metric over others (Harris, unpublished; Leroy and Frongillo, 2019).

A review of national policy documents shows that the persistent issue of hunger has historically shaped food policy in Zambia. Maize is the major food security crop, and the agriculture sector has focused on increasing production of maize to feed a growing population, and therefore on food security in a narrow sense. Two interlinked food security policies have supported and consolidated this focus on maize: the Food Reserve Agency (FRA) was reformed in 1996 in order to buy grain from farmers at a set price (essentially an output subsidy); and the Fertilizer Support Programme [later the Farmer Input Support Programme (FISP)] was set up in 2002 to provide cheap fertilizer and seed for growing grain (an input subsidy). These two programmes—FRA and FISP—together have accounted for upwards of 80% of the national agriculture budget for many years (Kuteya et al., 2016).

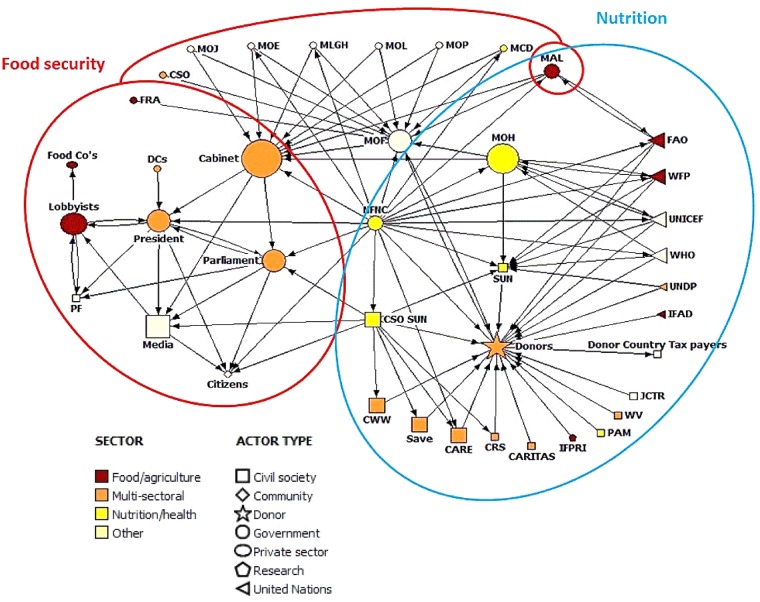

Policy document review also finds that nutrition programmes have existed in Zambia for decades, largely focusing on other child malnutrition outcomes (underweight and wasting) (Harris et al., 2017a). These activities existed largely within the health sector, though written nutrition policy underpinning programmes only emerged through the early part of the 21st century, with the National Food and Nutrition Policy (NFNP) passed in 2006. Nutrition programmes have focused on a variety of nutrition issues over the years (including treatment of acute malnutrition, micronutrient deficiencies, breastfeeding promotion and nutrition in HIV) and many of these continue as part of health sector programming. Review specifically of national nutrition policy documents however finds that between 2006 and 2013 the major focus of nutrition policy and programmes in Zambia crystalized on current narratives of stunting as the dominant problem to address. Stunting reduction was the first of eleven strategic directions in the 2011 National Food and Nutrition Strategic Plan (NFNSP), and became the major focus of the 2013 Most Critical Days nutrition programme (MCDP) which is the current nutrition implementation plan in Zambia. Content analysis of these three major nutrition policy documents in Zambia finds that mentions of four key nutrition issues (stunting, wasting, underweight and hunger) in the 2006 nutrition policy and subsequent 2011 strategy and 2013 plan show stunting far outstripping other issues in the more recent iterations, following the change internationally (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Changing national nutrition policy focus over time. Metric: Mentions of four major nutrition outcome measures in written Zambian nutrition policy. Calculation: Word count for each nutrition issue, divided by number of pages in the document.

This observation of wholesale change in nutrition focus in Zambia is supported by many of the national respondents’ KIIs. Respondents in this research identified the international development community [international Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), financial donors and those working through the UN Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) movement] as creating the original awareness, attention and priority for stunting policy and action in recent years, largely through technical assistance and systematic advocacy and funding for stunting as an issue. Narratives of being buffeted by the changing international agenda of the time were evident: ‘I think (…) the global movement has brought stunting to the fore, for us to start looking at stunting. I do not think that it came necessarily from Zambia, saying we have got a challenge of stunting. I think it’s because of the SUN movement and everybody now trying to focus on stunting’ [National government KII 2015_09].

The newer focus on stunting reduction in Zambia goes hand-in-hand with the recent international narrative on the need for sectors outside of health to be sensitive to the requirements of nutrition policy, and for multisectoral action. This comes through clearly in written nutrition policy and strategy, where roles are assigned in writing to several other sectors in policy documents emanating from the health sector, despite the health sector having no convening power over other sectoral ministries. It also recurs frequently in the interviews, with multisectorality one of the major practical themes that respondents discussed as a recent change in Zambia’s nutrition policy direction: ‘So you know (…) in the history of our country, in terms of nutrition, the past 20 years that I’ve been in this field I’ve never seen so much attention to nutrition. And in this case we are not talking about a particular intervention [but] a holistic approach and multi-sector response. (…) And so therefore it had indicated [to] those other ministries that they needed to do something’ [National government KII 2015_04].

The timing of changes in international and national policy documents, combined with these insights from the KIIs, suggest that stunting as a policy idea has been transferred from the international realm to national policy processes by specific groups of actors, and that this newer narrative of multisectorality for nutrition is encroaching on sectors outside of health.

Advocacy coalitions: defining the alternatives

Dominant international narratives do not encounter a vacuum at national level; rather they have to interact with myriad established and emerging ideas, interests, preferences, philosophies and beliefs within political, policy, technical and lay communities in the national political and policy arena. The document reviews and interviews suggest that prior to the change towards stunting as an outcome and multisectorality as the preferred process, food security and nutrition policies co-existed fairly peacefully for decades largely because they existed in different realms: food security was addressed by the agriculture sector and nutrition by the health sector. With its focus on multisectoral action to reduce stunting however, the newer nutrition policy narrative introduced by international actors increasingly impinges on the existing food security narrative as it attempts to alter agriculture policy away from a sole focus on maize self-sufficiency and towards the inclusion of attention to the diverse diets needed for nutrition: ‘Because now there was a policy, meaning a framework for nutrition implementation in the country, we actually now saw various sector ministries starting to plan from government perspective nutrition interventions in the different sectors. We started seeing ministry of agriculture department of women and youth, (…) we saw it changing to department of food and nutrition section. That was after the policy’ [National government KII 2015_13].

A visual map of the nutrition policy sub-system in Zambia (Figure 2) reveals how actors interact on these issues, and KII shed light on how and why different groups align. Fifty-seven actor entities (in this case, organizations) were mentioned in the NetMap group interview: 40 are linked through accountability in its various forms as reported by respondents, and shown on the map (Figure 2); the other 17 are not shown on the map because they have no direct accountability links, even though they may be involved in the issue (e.g. the National Farmers’ Union; noted in Table 2). In addition to the accountability links, influence scores for the different organizations ranged from 0 (no influence assigned over nutrition policy or programmatic decisions in Zambia, but involved in the issue) to 4 (most influential), shown by the size of the organization’s bubble on the map; influence is also denoted by the amount of accountability owed to or by an organization (in-links and out-links, as shown by the arrows on the map).

Figure 2.

Advocacy coalitions in the Zambian nutrition policy sub-system. Notes: ‘Sector’ colour denotes the sector the organization is seen as working in, according to respondents. The blue and red clusters overlaying the map are added after analysis of the study data, denoting broad ‘advocacy coalitions’. Relative influence of each actor was calculated by dividing the assigned influence value for each actor by the highest influence allocated by the respondents. Size of the actors on the maps then denotes relative influence assigned by respondents. The link of accountability was used as it was a key theme that emerged during early analysis of the interview data. The network map appears to be capturing several forms of accountability, including financial accountability through funding contracts; institutional accountability in terms of management or oversight structures; and political accountability through the processes of democracy. ‘Citizens’ explicitly included ‘voters’; ‘farmers’; and ‘community as recipients of programs’. There was a sense in the discussions that these were separate in people’s minds as ‘urban citizens and rural subjects’; Community and Citizens were noted as separate actors, although when voting and political mobilization were discussed they were conflated. ‘Donors’ mentioned were DfID, Irish Aid, SIDA, World Bank, EU and USAID. ‘Food companies’ mentioned were agro-dealers, beverage companies, food manufacturers/processors, millers, retailers, ZamBeef and ZamSugar. ‘SUN’ was understood as the broad SUN Movement, and explicitly incorporated the Zambian SUN Fund as a separate entity to its individual donors. ‘National NGOs’ were mentioned in connection with donors and citizens, but accountability links were not made explicit by the respondent group so these do not appear on the network map.

Table 2.

Full list of entities mentioned in the national NetMap

| ACF | Action Against Hunger | MAL | Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock |

| BAZ Cabinet | Biofuels Association of Zambia | MCD | Ministry of Community Development |

| MOE | Ministry of Education | ||

| CARE | Care International | MOH | Ministry of Health |

| CSO | Central Statistical Office | MOJ | Ministry of Justice |

| CARITAS | Caritas Internationalis | MOL | Ministry of Lands |

| CHAZ | Churches Health Association of Zambia | MLGH | Ministry of Local Government and Housing |

| CAZ | Cotton Association of Zambia | MMD | Movement for Multi-party Democracy |

| Citizens | See note above | NAZ | Nutrition Association of Zambia |

| CRS | Catholic Relief Services | NFNC | National Food and Nutrition Commission |

| CSO SUN | SUN Civil Society Organization | NISIR | National Institute for Scientific and Industrial Research |

| CWW | Concern Worldwide | PAM | Programme Against Malnutrition |

| DCs | District Commissioners | President | |

| Donors | See note above | PF | Patriotic Front |

| Donor country taxpayers | Parliament | ||

| FAO | UN Food and Agriculture Org. | Save | Save the Children |

| Food Co’s | Private sector food companies | SUN | Scaling up Nutrition |

| FRA | Food Reserve Agency | TDRI | Tropical Disease Research Institute |

| Harvest+ | HarvestPlus | UNDP | UN Development Programme |

| IAPRI | Indaba Agriculture Policy Research Institute | UNICEF | UN Children’s Fund |

| IBFAN | International Baby Food Action Network | UNZA | University of Zambia |

| IFAD | International Fund for Agriculture Development | UPND | United Party for National Development |

| IFPRI | International Food Policy Research Institute | UTH | University Teaching Hospital |

| JCTR | Jesuit Centre for Theological Reflection | VP | Vice President |

| Lobbyists | Specifically food industry lobbyists | WV | World Vision |

| Media | Various forms of media | WFP | UN World Food Programme |

| Mining | Mining industry | WHO | UN World Health Organization |

| MOF | Ministry of Finance | ZARI | Zambia Agricultural Research Institute |

| ZNFU | Zambian National Farmers Union | ||

The network map can approximately be seen in two halves: the upper and left-hand side of the network map is broadly related to national institutions (the government executive, sectoral ministries, private companies, the media and citizens), while the lower and right-hand side of the network map is broadly related to international institutions with a foothold in Zambia (UN agencies, international NGOs and international donors; see Table 2 for acronyms). Only three organizations working in the centre of the network—National Food and Nutrition Commission (NFNC), Ministry of Health (MOH) and CSO-SUN (a donor-funded civil society advocacy organization for nutrition)—were reported by participants to be accountable to both of these sides of the network on the issue of nutrition policy and practice, and connected to the most powerful actors on each side (shown by larger bubbles and/or more inward accountability arrows).

The network map illustrates an important division among groups within the Zambian food and nutrition policy sub-system that was found in the document reviews and interviews above: the two key nutrition issues in Zambia—hunger and stunting—are represented by different coalitions of policy actors: one with a focus on food security (coalition actors shown inside the red circles overlaying the map) and one on nutrition (coalition actors shown inside the blue circle). Though this division is not absolute (for instance there are departments of FAO and some of the major NGOs working on both issues), the interviews with these different actors confirm that the actors inside the blue circle are bringing a focus on stunting into Zambia’s policy discourse, while those inside the red circle broadly maintain a focus on traditional food security policy, suggesting that coalitions of actors are working towards these different ends. The attributes, belief systems, resources and strategies that define and bind each of these coalitions, according to this analysis, are laid out in Table 3.

Table 3.

Coalition attributes, beliefs, resources and strategies

| Nutrition/stunting coalition | Food security/hunger coalition | |

|---|---|---|

| Coalition attributes | Largely international in genesis and organizational makeup | Largely national grouping including the government executive |

| Advocacy network; support shared causes, motivated by shared values | Political network; both beliefs and political/economic interests important | |

| Professional network; epistemic community, motivated by shared interpretation of knowledge | Professional network; epistemic community, motivated by shared interpretation of knowledge | |

| Moral or economic imperative of reducing child malnutrition | Political imperative of maintaining the social contract | |

|

| ||

| Normative core beliefs | Set of ideas around providing help to people and doing social good | Zambian Humanism as the national philosophy, explicitly rejecting both the capitalist and communist models |

| Development approach that sees assistance largely as supporting state intervention; open to market-led approaches to improving nutrition | Socialist in its outlook, with centre-left socialist political parties ruling | |

| Increasingly market-led due to external pressures and political imperatives | ||

|

| ||

| Policy core beliefs | Malnutrition as lack of a diet quality and freedom from disease leading to stunting | Malnutrition as a lack of calories leading to hunger |

| Distance themselves from hunger as too simplistic | Yet to see their role in broader malnutrition issues | |

| Poor, rural communities of most concern, particularly women | Poor, rural communities of most concern, particularly farmers | |

|

| ||

| Secondary policy beliefs | Addressing the nexus of a lack of diet quality and access to health services and adequate child care as the answer | Producing more staple food (maize) as the answer |

| Maize farmers (mostly male) as the key target group | ||

| Food producers (farmers) and child carers (mostly female) as the target group | Sector-based agriculture programmes as the administrative setup | |

| Multisectoral co-ordination as the administrative setup | ||

|

| ||

| Resources | Nutrition policy action largely funded by international donor resources | Food security policy largely nationally funded, taking up to 80% of the agriculture budget |

| National ministries have minor nutrition departments with funding for salaries but little for programmes | Any focus on nutrition more broadly than calories in written policy is largely unfunded in practice | |

|

| ||

| Strategies | Frame a narrative that speaks to human and economic development | Maintain ‘business as usual’ agriculture policy |

| Challenge the primacy of maize in a diet diversity/quality narrative | Update policy approach with new technology (e-vouchers for a wider range of inputs) | |

| Increase awareness of nutrition statistics | Maintain funding through government budgets (in the face of opposition to agricultural subsidies by international donors) | |

| Fund nutrition programmes through donor support | ||

The food security coalition largely encompasses the national apparatus of government, and as such has a broadly political rationale for its policy choices. This coalition has a long history in Zambia: the document review shows that its main policies are entrenched in agricultural policy documents, funding cycles and bureaucratic structures. Implementation of food security policy is largely nationally funded, through the agriculture sector and smaller programmes under the ministry of community development. The implicit strategy of this coalition is therefore to maintain business as usual, drawing on cultural and historical framings of maize and the economic and social realities of rural life to preserve its food security focus in the interest of maintaining food supply and therefore the social contract.

The nutrition coalition, as shown in the sections above, is newer to the political arena in Zambia, and particularly in its modern form promoting stunting reduction and multisectoral action (and therefore directly challenging the food security narrative) has only emerged in the past 10 years. The reduction of stunting is framed as either an economic or a moral imperative in documents produced by this coalition. Implementation of nutrition policy is largely funded by international donor resources; national ministries have minor nutrition departments with funding for salaries but little for programmes. The nutrition coalition’s multisectoral approach also has less political traction because of its inherent complexity, which does not offer quick political wins in the way that agricultural subsidies do.

Both coalitions are essentially epistemic communities, sharing similar motivations for their work and interpretations of the evidence in favour of these. Within both coalitions actors can be said to share normative core beliefs broadly supportive of socially focused intervention, either by government or by civil society, into community issues such as hunger and malnutrition: both coalitions can be described as broadly left-leaning in philosophy but increasingly market-oriented by necessity of the practicalities of providing assistance and participating in the global economy.

A dichotomy in framing of the policy issue occurs at the level of policy core beliefs, with the food security coalition framing malnutrition as a lack of calories leading to hunger, and the nutrition coalition framing malnutrition as poor health combined with a lack of a diet quality leading to stunting, as seen in the policy document review and interviews above. It is these policy core beliefs that largely characterize the differences between the two coalitions. This leads to a divergence in preferred policy responses, with the stunting coalition promoting multisectoral co-ordination to address poor diets and health; and the food security coalition promoting agriculture-sector policy for increased calorie production.

While there are individuals in both coalitions working on both food security and stunting reduction, there was no sense in the interviews conducted here that the individuals involved in the core policy areas of each sector were particularly aware of the work of the other coalition: Those working on agriculture and food security largely don’t see their role in child malnutrition beyond producing staple foods; and those in the nutrition coalition have not engaged to a large extent with either the political economy of maize dominance, or the popular view of hunger, favouring technical framings and approaches. The interviewees in this research did not self-identify as belonging to either coalition; rather the lack of cross-reference among these groups in policy documents and interviews led to the analysis above.

Discussion

This study contributes a primary empirical analysis of political phenomena in Zambia’s nutrition policy process, finding that it is possible to understand these more fully than has so far been achieved in much nutrition literature through the application of multiple political science theories. Combining political science theories of policy transfer and advocacy coalitions sheds new light on nutrition policy processes, and applying these theories allows the generalization of findings from this case study to assess their relevance in other contexts. This work also tests these theories in new contexts, finding that they maintain their relevance in low-income country settings. In this study, the theories were used sequentially—i.e. first to identify a case of policy transfer, then to explain the transfer through the actions of advocacy coalitions. Future work could further explore the utility of this approach to theory combination.

In particular, this study extends the application of the theory of policy transfer. A key feature the theory (Dolowitz and Marsh, 1996; Dolowitz and Marsh, 2000) is that policies can be shared between and within countries, and between international, national and local levels of governance (Hulme, 2005; Ngoasong, 2011). To strengthen early policy transfer research, there have been calls to broaden the scope of work away from just industrialized countries towards the different complexities of the developing world as a potent testing ground for these theories; to combine the policy transfer framework with other streams of work on networks and governance; and to explore policy complexity in international agendas and communities, and the multi-level nature of policy from international to local (Hulme, 2005; Marsh and Sharman, 2009; Benson and Jordan, 2011). The current study addresses many of these suggestions on scale and scope in using this theory to explain the movement of international ideas into Zambia’s national nutrition policy.

This study also has limitations, key among these being the NetMap focus on organizations, whereas a finer grain of detail may have been possible if asking about individual actors; and the focus of most KII on members of what would later be characterized as the nutrition coalition, at the expense of deeper interaction with food security actors.

As Schattschneider (1975) surmised, in the end it is conflict over issues, and the ways that people divide into groups around a question, that leads to agendas being set and to policy maintenance or change. This study finds that as international nutrition priorities have crystallized around the issue of child stunting reduction and sidelined other nutrition issues (including hunger), so too has Zambian nutrition policy come to focus almost exclusively on stunting. This fits with the findings of other work, which has found significant paradigm shifts in ideas and policy for nutrition over time, including a current focus on stunting (Nomura et al., 2015; Gillespie and Harris, 2016; Harris, unpublished). International ideas have been transferred into Zambian national policy largely by a coalition of international stakeholders active in the national nutrition policy sub-system. This ‘behind-the-scenes’ influence on national policy is increasingly being documented in various health fields (Storeng et al., 2019), with implications for national sovereignty and legitimacy, and the balance of power among policy actors.

Alongside the stunting narrative is an explicit call for multisectoral action, hence nutrition policy—historically the preserve of the health sector—is encroaching on other sectors, in particular the agriculture sector. Those working on more traditional food security policy therefore can be characterized as a rival coalition, with a largely unacknowledged tug-of-war between conflicting policy priorities. The nutrition policy sub-system in Zambia is split between an internationally led coalition believing in action on child stunting, and a nationally led coalition focused on food security and hunger. Again, this chimes with other work which has found the broader nutrition community fragmented and arguing over a multiplicity of framing narratives, without clear prioritization (Morris et al., 2008; Balarajan and Reich, 2016; Béné et al., 2019).

Both coalitions in Zambia have been successful in getting their agendas into policy formulation in different sectors, and defining the alternatives to choose between. However, the lack of acknowledgement of one coalition by another is leading to policy inertia, whereby neither coalition can progress an entirely coherent policy agenda. Debates on multisectoral governance of nutrition in Zambia did not over the time of this research include engaging with hunger framings, and agricultural policymakers have hardly engaged with nutrition. Policy review and evaluation from various external quarters are showing that current approaches are solving neither hunger nor stunting issues however; both hunger and stunting are important issues, and both remain at unacceptable levels in Zambia. Ultimately a strategy that focuses on both is needed if legitimacy of the policy actors involved is to be maintained, not a logical dismantling of one issue to address the other. Previous work has suggested for instance that a focus on enabling quality diets—those containing a variety of nutrient-rich foods, rather than simply starchy staples—provides an opportunity to join previously competing agendas across various food and nutrition actors (Thow et al., 2016).

Hunger remains an issue in Zambia, and cannot be ignored or sidelined by the nutrition coalition in its efforts to frame malnutrition as more complex than just lack of calories; but stunting too is at unacceptable levels, and has a clear diet quality component that the food security coalition can’t sweep aside. While the two coalitions work largely separately on their own issues in Zambia, some respondents in this research professed shock at learning both the hunger and malnutrition numbers in recent years, which might provide an entry point for negotiation and change; the policy core beliefs of each coalition might be amenable to change with evidence, communication and understanding. The broader point is for nutrition practitioners and advocates to be explicit about what these divisions mean for nutrition policy, and to reflect on whether there might be more inclusive ways to practice. The study ultimately is about policy transfer, as explained by the presence of advocacy coalitions and their different beliefs, resources and power, and these concepts can be investigated wherever the nutrition system reaches down from international to national level.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this research was obtained through the University of London (SOAS) review board, and the University of Zambia review board. Free and informed consent of all research participants was obtained and documented.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges three reviewers with deep knowledge of the Zambian nutrition community for comments on an earlier draft, as well as the time and support of all research respondents.

Funding

This research was undertaken as part of a PhD funded by the Leverhulme Centre of Integrative Research on Agriculture and Health (LCIRAH) at SOAS, University of London, UK. Furhter funding for aspects of the research was through a grant under the Stories of Change project of the Agriculture for Nutrition and Health consortium of the CGIAR.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- Acosta AM, Haddad L.. 2014. The politics of success in the fight against malnutrition in Peru. Food Policy 44: 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Balarajan Y, Reich MR.. 2016. Political economy challenges in nutrition. Globalization and Health 12: 70.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béné C, Oosterveer P, Lamotte L, Brouwer ID, de Haan S, Prager SD, Talsma EF, Khoury CK.. 2019. When food systems meet sustainability—current narratives and implications for actions. World Development 113: 116–30. [Google Scholar]

- Benson D, Jordan A.. 2011. What have we learned from policy transfer research? Dolowitz and Marsh revisited. Political Studies Review 9: 366–78. [Google Scholar]

- Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Ezzati M, Mathers C, Rivera J.. 2008. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. The Lancet 371: 243–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bump JB. 2018. Undernutrition, obesity and governance: a unified framework for upholding the right to food. BMJ Glob Health. 3(Suppl 4): e00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairney P. 2013. Standing on the shoulders of giants: how do we combine the insights of multiple theories in public policy studies? Policy Studies Journal 41: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Health, Tropical Diseases Research Centre, University of Zambia and Macro International Inc. 2014. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2013–14. Calverton, Maryland, USA: CSO and Macro International Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Development Initiatives. 2018. 2018 Global Nutrition Report: Shining a Light to Spur Action on Nutrition. Bristol, UK: Development Initiatives. [Google Scholar]

- Dolowitz D, Marsh D.. 1996. Who learns what from whom: a review of the policy transfer literature. Political Studies 44: 343–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dolowitz DP, Marsh D.. 2000. Learning from abroad: the role of policy transfer in contemporary policy‐making. Governance 13: 5. [Google Scholar]

- Engesveen K, Nishida C, Prudhon C, Shrimpton R.. 2009. Assessing countries’ commitment to accelerate nutrition action demonstrated in PRSPs, UNDAFs and through nutrition governance. SCN News 37: 10–6. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. 2016. FAO Statistical Pocketbook—World Food and Agriculture. Rome, Italy: FAO. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie S, Harris J.. 2016. How nutrition improves: half a century of understanding and responding to the problem of malnutrition In: Pandya-Lorch R, Gillespie S (eds). Nourishing Millions: Stories of Change in Nutrition. Washington DC: IFPRI. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie S, McLaughlan M, Shrimpton R (2003). Combatting Malnutrition: Time to Act. AS. Preker Washington DC, World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad L. 2013. Building an enabling environment to fight undernutrition: some research tools that may help. The European Journal of Development Research 25: 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hafner-Burton EM, Kahler M, Montgomery AH.. 2009. Network analysis for international relations. International Organization 63: 559–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hanneman RA, Riddle M.. 2005. Introduction to Social Network Methods. Riverside, CA: University of California, Riverside. (Available online at http://faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/). [Google Scholar]

- Harris J. (unpublished). Narratives of nutrition: alternative explanations for international nutrition practice.

- Harris J, Drimie S, Roopnaraine T, Covic N.. 2017. From coherence towards commitment: Changes and challenges in Zambia’s nutrition policy environment. Global Food Security13: 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Frongillo EA, Nguyen PH, Kim SS, Menon P.. 2017. Changes in the policy environment for infant and young child feeding in Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia, and the role of targeted advocacy. BMC Public Health 17(Suppl 2): 492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaver R. 2005. Strengthening Country Commitment to Human Development, Lessons from Nutrition. Directions in Development. Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Hulme R. 2005. Policy transfer and the internationalisation of social policy. Social Policy and Society 4: 417–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kuteya AN, Sitko NJ, Chapoto A, Malawo E.. 2016. An In-Depth Analysis of Zambia's Agricultural Budget: Distributional Effects and Opportunity Cost. IAPRI Working Papers. Lusaka, Zambia: Michigan State University. [Google Scholar]

- Leroy JL, Frongillo EA. 2019. Perspective: What Does Stunting Really Mean? A Critical Review of the Evidence. Advances in Nutrition 10: 196–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh D, Sharman JC.. 2009. Policy diffusion and policy transfer. Policy Studies 30: 269–88. [Google Scholar]

- Morris S, Cogill B, Uauy R.; Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group. 2008. Effective international action against undernutrition: why has it proven so difficult and what can be done to accelerate progress? Lancet 371: 608–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natalicchio M., Garrett J, Mulder-Sibanda M, Ndegwa S, Voorbraak D (eds). 2009. Carrots and Sticks: The Political Economy of Nutrition Policy Reforms. Health, Nutrition and Population (HNP) Discussion Paper. Washington, DC: World Bank, IFPRI. [Google Scholar]

- Ngoasong MZ. 2011. Transcalar networks for policy transfer and implementation: the case of global health policies for malaria and HIV/AIDS in Cameroon. Health Policy and Planning 26: 63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett N, Gillespie S, Haddad L, Harris J.. 2014. Why worry about the politics of childhood undernutrition? World Development 64: 420–33. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura M, Takahashi K, Reich MR.. 2015. Trends in global nutrition policy and implications for Japanese development policy. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 36: 493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier DL, Frongillo EA, Gervais S. et al. 2012. Nutrition agenda setting, policy formulation and implementation: lessons from the Mainstreaming Nutrition Initiative. Health Policy Plan 27: 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich MR, Balarajan Y.. 2012. Political Economy Analysis for Food and Nutrition Security. Washington DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier PA, Jenkins-Smith HC.. 1993. Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach (Theoretical Lenses on Public Policy). USA: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schattschneider EE. 1975. The Semi-Sovereign People: A Realist's View of Democracy in America. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer E. 2007. The Power Mapping Tool: A Method for the Empirical Research of Power Relations. IFPRI Discussion Paper 00703. Washington DC: IFPRI. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer E, Waale D.. 2008. Tracing Power and Influence in Networks: Net-Map as a Tool for Research and Strategic Network Planning. Washington DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman J. 2007. Generating political priority for maternal mortality reduction in 5 developing countries. American Journal of Public Health 97: 796–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman J, Smith S.. 2007. Generation of political priority for global health initiatives: a framework and case study of maternal mortality. Lancet 370: 1370–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storeng KT, Palmer J, Daire J, Kloster MO.. 2019. Behind the scenes: International NGOs’ influence on reproductive health policy in Malawi and South Sudan. Global public health 14: 555–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thow AM, Greenberg S, Hara M. et al. 2018. Improving policy coherence for food security and nutrition in South Africa: a qualitative policy analysis. Food Security 10: 1105–30. [Google Scholar]

- Thow AM, Kadiyala S, Khandelwal S, Menon P, Downs S, Reddy KS.. 2016. Toward food policy for the dual burden of malnutrition: an exploratory policy space analysis in India. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 37: 261–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Grebmer K, Bernstein J, Hossain N. et al. 2017. Global Hunger Index: The Inequalities of Hunger. Washington, D.C, Bonn, and Dublin: International Food Policy Research Institute, Welthungerhilfe, and Concern Worldwide. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. 2006. WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age: Methods and Development. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]