Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Lack of robust program evaluation has hindered the effectiveness of school-based drug abuse prevention curricula overall. Independently evaluated randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of universal, middle school-based drug abuse prevention curricula are the most useful indicators of whether such programs are effective or ineffective.

OBJECTIVE

To conduct a systematic review identifying independently evaluated RCTs of universal, middle school-based drug abuse prevention curricula; extract data on study quality and substance use outcomes; and assess evidence of program effectiveness.

EVIDENCE REVIEW

Psyclnfo, Educational Resources Information Center, Science Citation Index, Social Science Citation Index, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were searched between January 1,1984, and March 15, 2015. Search terms included variations of drug, alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use, as well as school, prevention, and effectiveness. Studies included in the review were RCTs carried out by independent evaluators of universal school-based drug prevention curricula available for dissemination in the United States that reported alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, or other drug use outcomes. Two researchers extracted data on study quality and outcomes independently using a data extraction form and met to resolve disagreements.

FINDINGS

A total of 5071 publications were reviewed, with 13 articles meeting final inclusion criteria. Of the 13 articles, 6 RCTs of 4 distinct school-based curricula were identified for inclusion. Outcomes were reported for 42 single-drug measures in the independent RCTs, with just 3 presenting statistically significant (P < .05) differences between the intervention group and the control group. One program revealed statistically significant positive effects at final follow-up (Lions-Quest Skills for Adolescence).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

The results of our review demonstrate the dearth of independent research that appropriately evaluates the effectiveness of universal, middle school-based drug prevention curricula. Independent evaluations show little evidence of effectiveness for widely used programs. New methods may be necessary to approach school-based adolescent drug prevention.

Preventing youth alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other illicit drug use is an important priority of drug policy; since 1987, the federal government has invested more than $10 billion in school-based drug abuse prevention curricula designed for class-room delivery in middle and junior high schools (sixth through ninth grades). Most school-based drug prevention programs are intended for children and adolescents in these grade levels.1 The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration maintains a National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices (NREPP)2 of vetted programs used by many states and school districts to guide decisions about which programs to purchase and implement. However, lists such as the NREPP have been criticized for placing more emphasis on study design than on data analysis techniques and presentation of results when evaluating programs for inclusion on the list.3 Lack of consensus as to which programs effectively reduce substance use among early adolescents raises the question of what constitutes high-quality evaluation. Two study elements contributing greatly to the quality of an evaluation are randomization and independent evaluation. According to the Society for Prevention Research’s standards of evidence,4 randomization is essential in drawing clear causal inferences from a study, and independent evaluation is desirable when conducting intervention effectiveness studies.

The most widely used prevention curricula have been subject to numerous randomized controlled trials (RCTs).5 In a 2008 comprehensive, systematic review of universal, middle school-based drug prevention program evaluations, Faggiano et al6 examined 29 RCTs and concluded that skills-based (as opposed to affective or knowledge-based) interventions can be effective in reducing marijuana and other illicit drug use. The authors noted that, of 50 RCTs selected, only 29 were of sufficient quality for inclusion in the review, and the variability of measurement among studies meant that data from only up to 4 studies could be included in each meta-analysis. A 2008 review by Dobbins et al7 examined 12 systematic reviews published between 1970 and 2007 that assessed the effectiveness of prevention programs; however, that study evaluated community and school-based prevention programs specific to tobacco use. Thomas and Perera8 also assessed smoking-specific prevention programs through 23 high-quality RCTs. In a more expansive meta-analysis conducted in 1986, Tobler9 evaluated 143 school-based drug prevention programs for 6th to 12th graders. These studies were reevaluated in 1993 with new selection criteria to assess a subset of 39 of the original articles, revealing that interactive programs were more effective in drug prevention than were noninteractive programs.

Although there are several published RCTs, many were carried out by program developers rather than by independent researchers. Developers are usually the first to evaluate their programs during and immediately after development, and they may have a financial interest in disseminating their programs as well as nonfinancial reasons for wanting their programs to succeed, including publications and professional promotions, thus raising the possibility of biased results.10 Ideally, developers’ evaluations would be followed up by independent evaluations, although this outcome is rare owing to high costs associated with conducting RCTs in schools. When research is funded by industry, the odds of the outcome being in industry’s favor are increased more than 3-fold.11

Several scholars12–16 have examined the issue of developer-led intervention research and pointed out important aspects, including the tightly controlled conditions in which developer-led interventions are typically conducted, the testing of multiple different outcomes using less-than-ideal data analytic strategies, and the lack of long-term follow-up studies. Each of these approaches to intervention research has the potential to inflate positive findings, leading to the perception that programs are effective even when later independent evaluations fail to confirm these findings. The object of our review was to systematically identify RCTs of school-based prevention curricula conducted by independent researchers and assess the evidence for effectiveness based on these studies.

Methods

Search Strategy

The following databases were searched for relevant articles published in peer-reviewed journals between January 1,1984, and March 15, 2015: PsycInfo, Educational Resources Information Center, Science Citation Index, Social Science Citation Index, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. We used the following search term string: drug use, drug abuse, drug misuse, substance use, substance abuse, substance misuse, addiction, alcohol use, alcohol abuse, alcohol misuse, tobacco use, smoking, marijuana, and school, school-based, schools, classroom, child, adolescent, youth, student, and prevention, education, curriculum, curricula, health education, program, and evaluation, study, outcome, outcomes, experiment, trial, efficacy, effectiveness, follow-up, and randomized, randomized trial, random assignment, randomization, randomly assigned, experimental.

Selection Criteria

Studies were included in the review if they were RCTs carried out by independent evaluators of universal, school-based drug prevention curricula available for dissemination in the United States that reported alcohol and/or other drug use outcomes and were published in English. Studies of smoking prevention curricula and evaluations of broader curricula reporting only smoking outcomes were excluded. Programs were considered to be available for dissemination if sufficient materials, training, and support resources were easily obtainable by school districts wishing to implement the program. A universal program is one developed to prevent drug use among all children of the target age group and is not focused on students of a particular sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic level, or those considered to be at high risk of drug abuse.

We considered program evaluators to be independent if (1) they did not have a role in the development of the program being evaluated or a financial interest in the program and (2) the organization funding the evaluation did not have a role in the development of the program being evaluated or a financial interest in the program. We were interested in the funding organization’s role in program development only to the extent that their investment and sense of ownership in a program could have introduced bias into the evaluation. We did not consider it a conflict of interest in cases in which the National Institute on Drug Abuse or another federal government agency funded the development of a program and later funded an independent evaluation of that program.

Evaluation of Studies

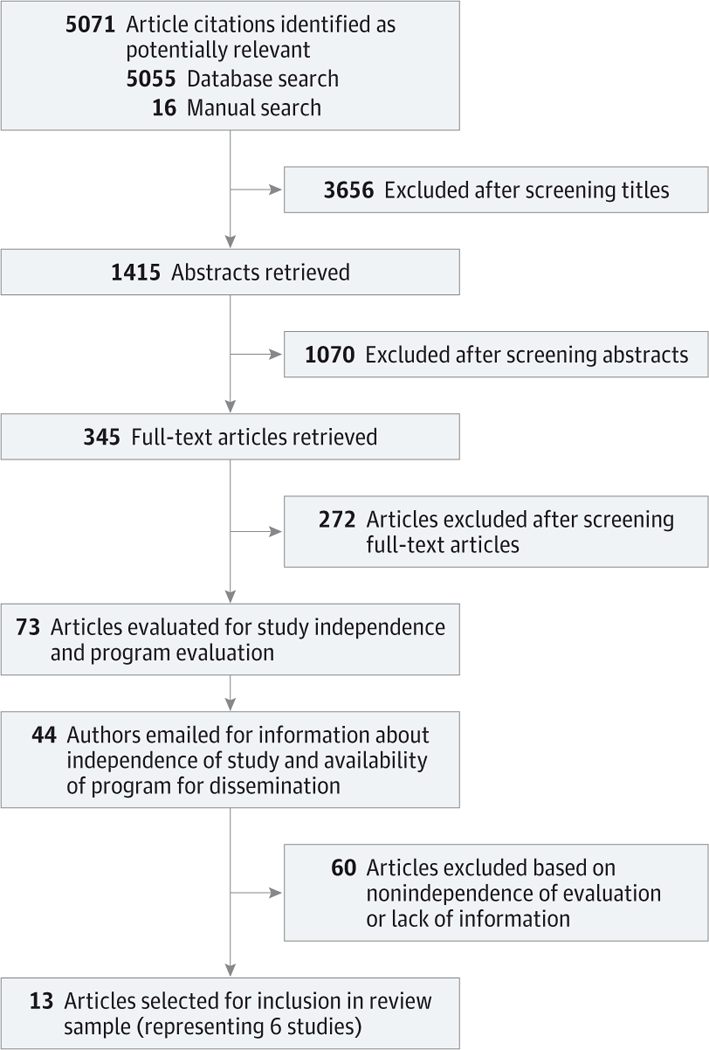

The Figure details the article screening process. We emailed and/or telephoned 44 authors to establish the degree of independence of their evaluations and the availability of programs for dissemination. We contacted first authors whenever possible and second and third authors when we were unable to reach the first authors. Twenty-nine individuals supplied the requested information; the remainder could not be contacted or declined to share the information. However, we were able to determine whether some evaluation studies were independent by consulting the literature and program websites.

Figure.

Article Selection Process

Two researchers (A.B.F. and S.H.) extracted data independently from eligible articles using a data extraction form and met to resolve disagreements. We extracted data about study methods, setting, population, intervention characteristics, substance use outcomes, and quality We determined that a meta-analysis of the data would not add to the findings of our review since the interventions represented are highly heterogeneous in content, delivery mechanism, and duration, and combining their effects on alcohol, tobacco, and other substance use would obscure these important differences.

Results

The database search yielded 5071 unique citations, and additional candidates for inclusion were found in article reference lists and from other sources; 13 articles met the final inclusion criteria. A total of 6 RCTs of 4distinct school-based curricula were identified: Life Skills Training (LST) (1 study17–19), Lions-Quest Skills for Adolescence (SFA) (1 study20,21), Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) (2 studies22–25), and Project ALERT (ALERT) (2 studies26–29)(Table1). Life Skills Training, ALERT, and SFA are listed on the NREPP; DARE is not included.

Table 1.

Program Descriptions and Studies Included in the Review

| Source | Program Name | Program Description |

|---|---|---|

| Clayton et al,22 1991 Clayton et al,23 1996 Lynam et al,24 1999 |

Drug Abuse Resistance Education |

Resistance skills taught by uniformed police officers |

| Ringwalt et al,25 1991 | ||

| Smith et al,17 2004 Vicary etal,18 2004 Vicary et al,19 2006 |

Life Skills Training | Normative, resistance skills, and social skills education |

| Ringwalt et al,26 2009 Ringwalt et al,27 2010 Clark et al,28 2011 |

Project ALERT | Normative and resistance skills education |

| St Pierre et al,29 2005 | ||

| Eisen et al,20 2002 Eisen et al,21 2003 |

Lions-Quest Skills for Adolescence |

Normative, resistance skills, and social skills education |

Life Skills Training, designed to teach children skills to resist peer pressure to use drugs as well as broader life skills and normative information, consists of 30 class sessions delivered in seventh, eighth, and ninth grades.30 ALERT, an 11-session program for seventh and eighth graders based on the social influences model, uses normative education (teaching that, contrary to popular belief, few teens use drugs) and skills to resist peer pressure to use drugs.26 Lions-Quest SFA, a 103-lesson curriculum to be taught in sixth through eighth grades, teaches resistance and social skills designed to improve self-esteem, decision making, and communication skills in addition to normative education.21 DARE, which teaches skills to resist peer pressure to use drugs and/or alcohol, consists of 10 sessions delivered in the classroom to fifth and sixth graders by uniformed police officers.25 In 2010, DARE replaced the curriculum it had used since 1983 with a new curriculum, Keepin’ it REAL.31 Because DARE is used nationwide and its delivery by uniformed police officers is a unique aspect of the program that will remain unchanged, we have included the 3 independent evaluations of the original curriculum in this review. To our knowledge, the Keepin’ it REAL curriculum has not been independently evaluated.

Although all studies in this sample were independent RCTs, they differed widely with regard to setting, population, and research methods (eTable in the Supplement). Studies were conducted in urban, suburban, and rural settings in classrooms ranging from fifth to ninth grades. The number of participating schools in individual studies ranged from 6 to 34, and the number of baseline students ranged from 435 to 7426. Each study had methodologic limitations, such as weaknesses in recruitment, randomization, baseline equivalence, attrition, fidelity of implementation, or consistency of control group interventions.

Recruitment

Four of 6 studies17–24,26–28 (67%) reported recruitment rates (number of students eligible to participate vs the number who participated), which ranged from 70% to 93%. The one study22–24 that used a passive parental consent process (students enrolled unless their parents objected) reported a recruitment rate of more than 90% (eTable in the Supplement). The studies that reported using active parental consent (students enrolled only after parents had given express permission) had rates ranging from 70% to 78%. The DARE evaluation did not specifically report the recruitment rate; however, the authors11 stated that only 3.2% of parents refused to allow their children to participate in the study.

Randomization

Five of the 6 studies22–24 (83%) used the school as the unit of randomization (eTable in the Supplement). However, in the study of ALERT,29 individual classrooms within schools were randomized to intervention and control conditions. One20,21 of the 6 studies (17%) identified in our systematic review matched schools with similar characteristics before assigning them to intervention or control conditions: the authors paired schools with similar prevalence of recent drug use. One of the studies had unbalanced numbers of intervention and control schools: the DARE evaluation22,23 enrolled 23 intervention schools and only 8 controls.

Baseline Equivalence

Baseline equivalence between intervention and control groups on substance use measures was reported in 2 of the 6 studies (33%) examined (SFA20,21 and ALERT29 evaluations) (eTable in the Supplement). Clayton et al22,23 found higher baseline rates of alcohol use in the DARE group compared with controls. Similarly, Ringwaltetal25 found the DARE intervention group to have more lifetime history of alcohol use compared with controls. In the study of LST,17–19 the intervention group reported higher substance use levels. The study of ALERT17–28 showed higher rates of past 30-day alcohol use in the intervention group compared with the control group.

Attrition

Student participation rates from pretest to follow-up ranged from 55.2% to 91.0% and showed a pattern of decreasing retention with increasing length of follow-up (eTable in the Supplement). Study retention rates were related to length of follow-up, as expected. For example, the 5-year DARE study evaluation22,23 had a 55.2% retention rate, whereas that of the DARE study with immediatefollow-up25 was much higher at 91.0%.

Fidelity of Implementation

Fidelity of implementation was measured and reported in 3 of the 6 studies (50%). In their study of LST, Smith et al17 and Vicary et al18,19 found that 81% of the lessons were delivered (eTable in the Supplement). For the ALERT studies, Ringwalt et al26,27 and Clark et al28 found that 97.4% of the lessons were delivered, and St Pierre et al29 reported that 98% of program activities were covered in class. However, in the Ringwalt et al26,27 and Clark et al28 study of ALERT, the program was implemented beginning in sixth grade rather than seventh grade, the age group for which the curriculum was originally designed. The SFAstudy20,21 tested a condensed version of the program, cutting the original 103 lessons to 40. The LST developer30 described the curriculum as 30 sessions implemented in seventh and eighth grades (15 sessions each year) and booster sessions in high school. However, Vicary et al17–19 implemented LST with 15 sessions in seventh grade, 10 sessions in eighth grade, and 5 to 7 booster lessons in ninth grade. Clayton et al22,23 eliminated 1 session (on gang involvement) of the DARE curriculum.

Control Group Intervention

In 4studies17–23,26–28(67%), the authors reported that control groups received some form of intervention, although details of these interventions are unclear in several cases (eTable in the Supplement). In the DARE study,22,23 control schools implemented drug abuse prevention activities, but no details about these activities were provided. In evaluating ALERT, the authors26–28 reported that control schools were allowed to implement non-evidence-based drug prevention curricula, but no details were provided about which schools implemented particular programs and activities. Eisen et al20,21 reported that control schools in the SFA study received their usual drug programming, but details were not provided.

Substance Use

Studies meeting our criteria reported a variety of substance use outcome measures (Table 2). The most common measures were current (past month or 2 weeks) alcohol and cigarette use (4 studies)20,21,25-29and lifetime alcohol and cigarette use (4studies).20,21,25–29 Other measures included current marijuana and other drug use; current alcohol bingeing; past-year alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use; lifetime use of marijuana and other illicit drugs; frequency of alcohol, cigarette, smokeless tobacco, marijuana, and inhalant use; and frequency of alcohol bingeing and drunkenness.

Table 2.

Substance Use Behavior Outcomes Measureda

| Behaviorb | DARE Studies | LST Studies | ALERT Studies | SFA Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol use | ||||

| Current | X25 | X,26–28 X29 | X20,21 | |

| Past year | X22,23 | X29 | ||

| Lifetime | X25 | X,26–28 X29 | X20,21 | |

| Frequency | X17–19 | |||

| Bingeing | NA | NA | ||

| Current | X20,21 | |||

| Past year | ||||

| Lifetime | ||||

| Frequency | X17–19 | |||

| Cigarette use | ||||

| Current | X25 | X,26–28 X29 | X20,21 | |

| Past year | X22,23 | X29 | ||

| Lifetime | X25 | X,26–28 X29 | X20,21 | |

| Frequency | X17–19 | |||

| Drunkenness | NA | NA | NA | |

| Current | ||||

| Past year | ||||

| Lifetime | ||||

| Frequency | X17–19 | |||

| Inhalant use | NA | NA | NA | |

| Current | ||||

| Past year | ||||

| Lifetime | ||||

| Frequency | X17–19 | |||

| Marijuana use | ||||

| Current | X,26–28 X29 | O20,21 | ||

| Past year | X22,23 | O29 | ||

| Lifetime | X,26–28 X29 | O20,21 | ||

| Frequency | X17–19 | |||

| Snuff/chew use | NA | |||

| Current | NA | NA | ||

| Past year | ||||

| Lifetime | ||||

| Frequency | X17–19 | |||

| Other | NA | |||

| Current | X25 | X26–28 | X20,21 | |

| Past year | ||||

| Lifetime | X25 | X26–28 | X20,21 | |

Abbreviations: DARE, Drug Abuse Resistance Education; LST, Life Skills Training; NA, not applicable; SFA, Skills for Adolescence.

Nonsignificant outcomes measured are indicated with an “X”; outcomes with significant results at final study follow-up are indicated with an “O.”

Of the 42 single-drug measures for which outcomes were reported in the independent RCTs, only 3 showed statistically significant differences (P < .05) between the intervention group of interest and the control group, with one representing an iatrogenic program effect. The Eisen et al21 evaluation of SFA found statistically significant differences between intervention and control groups on rates of lifetime (27.24% vs 30.5%; 95% CI, −6.55 to −0.00) and current (past month) (11.32% vs 13.79%; 95% CI, −4.70 to −0.23) marijuana use. St Pierre et al29 reported an increase in past-year marijuana use (iatrogenic effect) among students in the teen-assisted ALERT intervention group (149% increase in odds; SE, 0.317) compared with controls. However, as the authors noted, it is possible that this one statistically significant result is due to chance rather than to a harmful effect of the ALERT program because several statistical tests were conducted.

Of the 4 programs evaluated, 1 (25%) showed some statistically significant positive effects at final follow-up (SFA)21 and 3 (75%) did not (DARE,22–25 ALERT,26,27,29 and LST17–19). Marijuana use appeared to be most affected by the interventions evaluated, with 3 significant findings out of 9 measures reported, although the Project ALERT study29 finding was in an undesirable direction. No significant findings were reported for tobacco or alcohol use.

In addition to findings for universal samples on single-drug measures, some studies explored substance use outcomes for various subgroups of participants and found isolated effects among particular subgroups. Because we are interested in these programs’ effects on universal student populations rather than on subgroups, we did not extract this type of analytical data.

Discussion

Several other systematic reviews and meta-analyses have evaluated the effectiveness of school-based prevention programs, yet differences in methods make our review novel in its approach. Given that the inclusion criteria of our review were restricted to independently evaluated RCTs of drug prevention programs, our review provides for potentially less-biased conclusions regarding the effectiveness of school-based drug use prevention curricula. This review highlights the dearth of independent RCTs that have been carried out on universal drug prevention programs used nationwide. The more than 300 full-text articles screened yielded only 6 RCTs carried out by independent researchers. Several factors may help to explain why more independent evaluations have not been conducted. Program developers are highly motivated to evaluate their programs as part of the development process and as a way to prove the program’s efficacy. Research showing program effectiveness is essential to its inclusion on lists of evidence-based programs, such as the NREPP, and to successfully marketing the program to schools.Independent researchers may lack developers’ financial and professional incentives to evaluate a prevention program and must secure large grants to undertake the work.

Conducting research in schools comes with unique challenges. Identifying schools willing to take on a large-scale research project that do not already have an evidence-based drug prevention program in place is the first hurdle. Schools and districts can also impose restrictions that weaken the study. For example, in the study of DARE,22,23 the public school system insisted that only 8 of 31 schools (26%) be designated as control sites. No matter how carefully evaluators train teachers and staff to implement the program with fidelity, increasing pressures on classroom time can mean incomplete or dropped lessons and less-than-optimal time spent on individual program activities. Eisen et al20,21 had difficulty finding schools willing to implement the full 103-lesson SFA curriculum and had to cut it to 40 lessons.

Regarding analysis techniques across the 6 evaluated studies, one notable issue is the small number of schools in each study. Conducting group-level randomized evaluation with low unit counts could ultimately result in a lack of statistical power to properly conduct multilevel analysis. Another consideration when randomizing a limited number of schools is the potential difficulty in achieving baseline equivalence on key variables, such as sociodemographic characteristics and drug use. Even some of the largest studies included in our review failed to achieve equivalence through randomization. For example, in the Ringwalt et al study26,27 with 34 schools, intervention group students were more likely to have used alcohol in the past 30 days than were control group students. High costs associated with increasing the number of schools enrolled in a study make this a challenging issue to resolve.

Although each evaluation in this review had one or more methodologic challenges, they arguably represent some of the highest-quality, school-based prevention program evaluations conducted to date in real-life settings. Being independent evaluations, they are presumably less likely to include real or perceived conflicts of interest that are present in developer-led projects. For example, the studies included in our review were relatively free of the less-than-ideal statistical analysis techniques often seen in reports of developer-led evaluations. These techniques, including use of 1-tailed t tests and examining subgroups for evidence of effectiveness when whole-group analysis yields null findings, have been used in developer-led evaluations. Gorman and Huber15 demonstrated that using such techniques can make programs appear to be effective when evidence shows them to be ineffective among universal samples of children.

Although Faggiano et al6 included a more robust 29 RCTs in a systematic review for a total of 41 articles, the added criteria of independent evaluation in our review eliminated studies that might contribute misleading results. Faggiano et al based their assertion that skills-based programs effectively reduce marijuana and other drug use on one meta-analysis of just 4 studies and another of just 2 studies, and many of the studies included in the meta-analyses were conducted by the developers. The balance of evidence drawn from our sample of independent evaluations of 4 widely used, universal, school-based drug prevention curricula shows that these programs generally fail to reduce drug and alcohol use, although individual programs may be effective in preventing specific types of drug use among specific groups of students. Our findings on the DARE program are supported by those of a meta-analysis32 of mostly quasi-experimental DARE program evaluations that found no evidence of effectiveness in terms of tobacco, alcohol, or other illicit drug use.

Numerous factors limit the extent to which our review findings can be generalized to the many universal, school-based drug prevention curricula on the market today. Because we excluded all evaluations conducted by program developers, we were able to draw outcome data from only 6 studies of 4 unique programs. In addition, outcome measures reported in each of these studies were highly heterogeneous, making it difficult to compare across studies and making a meta-analysis unfeasible. Middle school prevention programs may differ significantly from those delivered to elementary and high school students; thus, our results cannot be applied to the curricula effectiveness outside middle school grades. Because our review excluded targeted, nonuniversal programs, these results cannot be generalized to curricula developed for and delivered specifically to children considered at high risk of substance use. Further limitations include the inconsistencies in student ages across the 6 evaluated studies since older children are more likely to use alcohol and illicit drugs than are younger children.

Conclusions

Our review shows the lack of independent research to ascertain the effectiveness of universal, middle school-based drug prevention curricula and the failure thus far of independent evaluations to show significant effectiveness in preventing substance use. With 25 years of research in this area showing mixed results, it may be time to rethink our approach to school-based adolescent drug prevention.

Supplementary Material

At a Glance.

We sought to systematically identify randomized controlled trials of school-based prevention curricula conducted by independent researchers and assess the evidence for effectiveness based on these studies.

A total of 6 randomized controlled trials of 4 distinct school-based curricula were identified.

Only 3 of 42 outcome measures evaluated showed statistically significant (P < .05) differences between the intervention group of interest and the control group, with one representing an iatrogenic program effect.

Independent evaluation studies using randomized designs are scarce and fail to show significantly positive effects of some of the most widely used middle school-based drug prevention curricula

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This research was supported in part by grant T-32DA007292 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: This research was undertaken by Drug Strategies, and no outside funding organization had any specific role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Drug Strategies, which currently employs Mss Falco and Hocini and, from 2008 to 2012, employed Ms Flynn, received grant support from the BEST Foundation to help develop an interactive game app designed to engage adolescents in drug abuse prevention. This grant ended June 30, 2013. The BEST Foundation funded the design and dissemination of Project ALERT, which is one of the programs reviewed in this article. No other disclosures were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ringwalt C, Hanley S, Vincus AA, Ennett ST, Rohrbach LA, Bowling JM. The prevalence of effective substance use prevention curricula in the nation’s high schools. J Prim Prev. 2008;29(6):479–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services. NREPP: SAMHSA’s National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices. http://www.nrepp.samhsa.gov/.Published 2014. Accessed March 17, 2014.

- 3.Gorman DM, Conde E, Huber JC Jr. The creation of evidence in “evidence-based” drug prevention: a critique of the Strengthening Families Program Plus Life Skills Training evaluation. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26(6):585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flay BR, Biglan A, Boruch RF, et al. Standards of evidence: criteria for efficacy, effectiveness and dissemination. Prev Sci. 2005;6(3):151–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sánchez V, Steckler A, Nitirat P, Hallfors D, Cho H, Brodish P. Fidelity of implementation in a treatment effectiveness trial of Reconnecting Youth. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(1):95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faggiano F, Vigna-Taglianti FD, Versino E, Zambon A, Borraccino A, Lemma P. School-based prevention for illicit drugs use: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2008;46(5):385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobbins M, DeCorby K, Manske S, Goldblatt E. Effective practices for school-based tobacco use prevention. Prev Med. 2008;46(4):289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas R, Perera R. School-based programmes for preventing smoking. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3(3):CD001293.doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tobler NS. Meta-analysis of adolescent drug prevention programs: results of the 1993 meta-analysis. NIDA Res Monogr. 1997;170:5–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorman DM, Conde E. Conflict of interest in the evaluation and dissemination of “model” school-based drug and violence prevention programs. Eval Program Plann. 2007;30(4):422–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP. Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;289(4):454–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisner M No effects in independent prevention trials: can we reject the cynical view? J Exp Criminol. 2009;5:163–183. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gandhi AG, Murphy-Graham E, Petrosino A, Chrismer SS, Weiss CH. The devil is in the details: examining the evidence for “proven” school-based drug abuse prevention programs. Eval Rev. 2007;31(1):43–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorman DM. Drug and violence prevention: rediscovering the critical rational dimension of evaluation research. J Exp Criminol. 2005;1:39–62. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorman DM, Huber JC Jr. The social construction of “evidence-based” drug prevention programs: a reanalysis of data from the Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) program. Eval Rev. 2009;33(4):396–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holder H Prevention programs in the 21st century: what we do not discuss in public. Addiction. 2010;105(4):578–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith EA, Swisher JD, Vicary JR, et al. Evaluation of Life Skills Training and Infused-Life Skills Training in a rural setting: outcomes at two years. J Alcohol Drug Educ. 2004;48(1):51–70. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vicary JR, Henry KL, Bechtel LJ, et al. Life Skills Training effects for high and low risk rural junior high school females. J Prim Prev. 2004;25(4):399–416. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vicary JR, Smith EA, Swisher JD, et al. Results of a 3-year study of two methods of delivery of Life Skills Training. Health EducBehav. 2006;33(3):325–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisen M, Zellman GL, Massett HA, Murray DM. Evaluating the Lions-Quest “Skills for Adolescence” drug education program: first-year behavior outcomes. Addict Behav. 2002;27(4):619–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisen M, Zellman GL, Murray DM. Evaluating the Lions-Quest “Skills for Adolescence” drug education program: second-year behavior outcomes. Addict Behav. 2003;28(5):883–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clayton RR, Catarello AM, Day LE, Walden KP Persuasive communication and drug prevention: an evaluation of the DARE program In: Donohew L, Sypher HE, Bukoski WJ, eds. Persuasive Communication and Drug Abuse Prevention. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1991:295–313. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clayton RR, Cattarello AM, Johnstone BM. The effectiveness of Drug Abuse Resistance Education (project DARE): 5-year follow-up results. Prev Med. 1996;25(3):307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynam DR, Milich R, Zimmerman R, et al. Project DARE: no effects at 10-yearfollow-up. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(4):590–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ringwalt C, Ennett ST, Holt KD. An outcome evaluation of project DARE (Drug Abuse Resistance Education). Health Educ Res. 1991;6(3):327–337 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ringwalt CL, Clark HK, Hanley S, Shamblen SR, Flewelling RL. Project ALERT: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(7):625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ringwalt CL, Clark HK, Hanley S, Shamblen SR, Flewelling RL. The effects of Project ALERT one year past curriculum completion. Prev Sci. 2010;11(2):172–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark HK, Ringwalt CL, Shamblen SR, Hanley SM, Flewelling RL. Are substance use prevention programs more effective in schools making adequate yearly progress? a study of Project ALERT J Drug Educ. 2011;41(3):271–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.St Pierre TL, Osgood DW, Mincemoyer CC, Kaltreider DL, Kauh TJ. Results of an independent evaluation of Project ALERT delivered in schools by cooperative extension. Prev Sci. 2005;6(4):305–31 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Botvin G, Griffin K. Prevention science, drug abuse prevention, and Life Skills Training: comments on the state of the science. J Exp Criminol. 2005;1(1):63–78. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elek E, Wagstaff DA, Hecht ML . Effects of the 5th and 7th grade enhanced versions of the Keepin’ it REAL substance use prevention curriculum.J Drug Educ. 2010;40(1):61–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.West SL, O’Neal KK. Project D.A.R.E. outcome effectiveness revisited. Am J Public Health. 2004; 94(6):1027–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.