Abstract

Objectives

This study explored whether TALENs‐mediated non‐homologous end joining (NHEJ) targeting the mutation site can correct the aberrant β‐globin RNA splicing, and ameliorate the β‐thalassaemia phenotype in β654 mice.

Material and methods

TALENs vectors targeted to the human β‐globin gene (HBB) IVS2‐654C >T mutation in a mouse model were constructed and selected to generate double heterozygous TALENs+/β654 mice. The gene editing and off‐target effects were analysed by sequencing analysis. β‐globin expression was identified by RT‐PCR and Western blot analysis. Various clinical indices including haematologic parameters and tissue pathology were examined to determine the therapeutic effect in these TALENs+/β654 mice.

Results

Sequencing analysis revealed that the HBB IVS2‐654C >T point mutation was deleted in over 50% of the TALENs+/β654 mice tested, and off‐target effects were not detected. RT‐PCR and Western blot analysis confirmed the expression of normal β‐globin in TALENs+/β654 mice. The haematologic parameters were significantly improved as compared with their affected littermates. The proportion of nucleated cells in bone marrow was considerably decreased, splenomegaly with extramedullary haematopoiesis was reduced, and significant decreases in iron deposition were seen in spleen and liver of the TALENs+/β654 mice.

Conclusion

These results suggest effective treatment of the anaemia phenotype in TALENs+/β654 mice following deletion of the mutation site by TALENs, demonstrating a simple and straightforward strategy for gene therapy of β654‐thalassaemia in the future.

1. INTRODUCTION

β‐thalassaemia is a genetically determined haematopoietic disorder caused by aberrant synthesis of the β‐globin chain of haemoglobin. It is a fairly common inherited disease, with approximately 1.5% of the world's population reported to be carriers, and over 40 000 children are born annually with β‐thalassaemia, according to the World Health Organization estimates.1 The clinical management of β‐thalassaemia largely depends on lifelong blood transfusions and iron chelation therapy. However, in addition to increased iron absorption, transfusion therapy can lead to progressive iron accumulation and tissue damage in multiple organs, such as liver and spleen.2 The majority of patients with β‐thalassaemia still experience reduced life expectancy and a relatively poor quality of life, especially those in developing countries. At present, the best treatment option for these patients is allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, which is limited by the availability of a histocompatible donor. Thus, gene therapy represents an attractive alternative for the treatment of β‐thalassaemia.3

More than 200 mutations in the human β‐globin gene (HBB) have been reported, and a large number of mutations are single‐nucleotide substitutions in functional regions of HBB.4 According to our previous study, a C→T substitution within the second intron of HBB (IVS2‐654C > T, c. 316 + 654 C > T) was found to be one of the most common β‐thalassaemia alleles affected in Han Chinese populations.5 The β654 mutation results in the generation of an aberrant 5′ donor splice site at position 652 and activation of a cryptic 3′ acceptor splice site at position 579, leading to the aberrantly spliced β‐globin mRNA containing a premature termination codon.5, 6 Fortunately, our study revealed that β654 patients were found to be able to produce approximately 15% of normal β‐globin, therefore a β+ rather than β0 phenotype,5, 6 making them suitable candidates for further exploration of various treatment options using gene therapy. As reduced synthesis of β‐globin chains results in the relative excess of α‐globin chains, the degree of excess determines the severity of the disease symptoms. Therefore, one favourable approach to treat β654‐thalassaemia is to disrupt the incorrect splicing to increase normal β‐globin synthesis, and thus to balance the α/β gene expression.

Our previous study using RNAi to knock down α‐globin mRNA combined with antisense RNA to reduce abnormal β654‐globin mRNA and increase correct splicing of β‐globin mRNA, demonstrated gratifying result to ameliorate the β‐thalassaemia symptoms in β654 mice.7, 8, 9 The strategy of transferring human β‐globin gene using a lentiviral vector in animal models and human patients was also implemented, which greatly relieved the anaemic complications.10, 11 However, the potential risks of using viral vector therapy remain challenging in clinical applications.12, 13, 14 With the rapid development of genome editing tools, such as zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator‐like effector nucleases (TALENs) and CRISPR/Cas9 (clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR‐associated protein 9) systems, the mutant DNA site can be modified with increased efficiency compared to standard homologous recombination, through generation of double‐strand DNA breaks (DSBs). A few pioneering studies have succeeded in targeting the HBB, both by TALENs and by CRISPR/Cas9 in β‐thalassaemia patient‐specific induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 However, the application of gene‐edited iPSCs is still limited by the low efficiency of homology‐directed repair (HDR) and the barrier associated with differentiation of iPSCs into sufficient number of haematopoietic cells for transplantation.

Non‐homologous end joining (NHEJ), on the other hand, occurs at a much higher frequency once the DSBs are introduced into the genome when comparing to HDR.21, 22 As the β654 mutation is due to the change of a single nucleotide located in the intron of HBB, we anticipated that a direct deletion of the mutant site by NHEJ would disrupt the incorrectly splicing of β‐globin mRNA while restoring the normal β expression. Thus, the present study utilizes TALENs‐mediated gene editing to target the HBB IVS2‐654C > T mutations, and investigates the effect of TALENs‐mediated NHEJ targeting the mutation in improve the β‐thalassaemia disease symptoms in β654 mice.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animals

The β654‐thalassaemia mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). In this mouse model, the two cis murine adult β‐globin genes (ie, major and minor) are replaced with a single copy of the human β654‐thalassaemia gene in one of the two alleles. The same aberrant splicing was observed as in its human counterpart, with a C > T substitution at nucleotide 654 of intron 2 in the β‐globin gene.

All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Children's Hospital of Shanghai. All the procedures were performed in strict accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. The construction of TALENs vectors

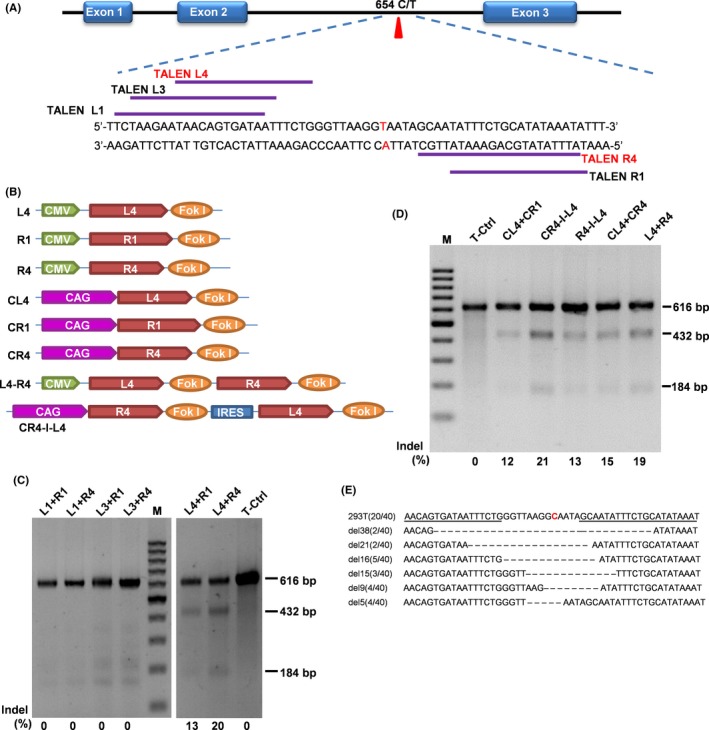

Six TALEN pairs (TALENL1‐R1, TALENL1‐R4, TALENL3‐R1, TALENL3‐R4, TALENL4‐R1 and TALENL4‐R4) were designed to directly target the IVS2‐654 C >T mutation of the human β globin gene (Figure 1A), and TALENs vectors were constructed by one‐step ligation using the FastTALETM TALEN Assembly kit (SIDANSAI, Shanghai, China). To enhance the expression efficiency of plasmids L4 and R4, the previous CMV promoter in the vectors was replaced by CAG promoter using restriction enzymes AvrII and SpeI, and the new vectors were named CL4 and CR4, respectively. To improve transfection efficiency, the co‐expression vector pCAG‐R4‐IRES‐L4 (CR4‐I‐L4) was also constructed by utilizing an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) sequence to link the two TALEN monomers.

Figure 1.

Construction and selection of TALENs to directly and efficiently delete the HBB IVS2‐654 C > T mutation. A, Six pairs of TALENs targeting the HBB IVS2‐654 mutation site were designed. The HBB IVS2‐654 mutation is shown in red, whereas the targeting sites are indicated by the purple lines. B, A schematic diagram of the TALENs plasmids. C, The T7EI assay using the 6 pairs of TALENs targeting the β‐globin locus in HEK293T cells. M, 100 bp DNA ladder, the percentage of indels is indicated under each pair of TALENs. D, The analysis of DSB efficiency by different TALENs vectors (seen in B) in HEK293T cells using T7EI assay. The percentage of the indels is indicated under each pair of TALENs, and CR4‐I‐L4 is one that showed the highest cleavage efficiency (21%). E, Representative Sanger sequencing results of HBB IVS2‐654 mutation site from sub‐cloning of the PCR product. The HBB IVS2‐654 mutation site is shown in red

2.3. Cell culture and transfection

HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS). To analyse the DSB efficiency of each TALENs, each pair of TALENs was transferred by Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) into HEK293T cells. In brief, HEK293T cells were cultured in six‐well tissue culture plates to 80% confluency and transfected with 5 μg plasmids via Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen). After 48 hours, genomic DNA was extracted from these cell lines.

2.4. T7 Endonuclease I assay

Genomic DNA was extracted from cells transfected with TALEN plasmids. PCR amplifies the TALENs targeting site were performed using the primers β‐L/R listed in Table S1. After purification with QIA quick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), the products were denatured and reannealed, and finally digested with T7 Endonuclease I at 37°C for 60 minutes in a reaction volume of 20 μL. Digested DNA was run on a 2% agarose gel. The efficiency of cleavage activity was calculated based on the relative band densities.

2.5. Off‐target analysis of TALENs‐mediated genome modification

To monitor possible off‐target events introduced by TALENs cleavage, potential gene regions harbouring similar recognition and cleavage sites were analysed using TAL Effector Nucleotide Targeter 2.0.23 Ten highly scored sites were selected for further analysis (Table S2). PCR amplicons with the length of 500 bp to 900 bp containing potential off‐target sites were amplified using the primers listed in Table S1. The DNAs from clones transferred with co‐expression vector pCAG‐R4‐IRES‐L4 were pooled, and the potential off‐target sites were amplified by PCR. The off‐target cleavages were detected by the T7EI assay.

2.6. Transgenic mice generation and screening

The co‐expression vector pCAG‐R4‐IRES‐L4 was digested with SphI (TaKaRa, Bio. (Dalian), Dalian, China), and the target fragments were purified with QIA quick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen Hilden, Germany) followed by microinjection into the pronucleus of the zygotes of C57BL/6 mouse strain. The double heterozygous TALENs+/β654 mice were generated by mating TALENs transgenic mice with β654 mice. PCR was performed to screen the transgenic mice based on tail biopsy DNA samples.

2.7. Southern blot

The TALENs transgenic founders were further confirmed by Southern blotting. In brief, 5 μg of genomic DNA obtained from transgenic to wild type (negative control) mice was digested with EcoRI, ran on an 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis, and then transferred to a nylon membrane (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany). The samples were hybridized with a digoxigenin (DIG)‐labelled probe amplified with the TALM‐L/R 574 bp amplification products (Table S1) to produce a 3.8 kb positive hybridization signal.

2.8. TAIL‐PCR

The TALENs gene integration sites were determined by TAIL‐PCR.24 The primers used in TAIL‐PCR were listed in Table S3. Pre‐amplification reactions were performed in 20 μL, and the primary or secondary TAIL‐PCRs in 50 μL. The PCRs were performed using a nexus gradient mastercycler (Eppendorf, Eppendorf, Germany) with thermal conditions shown in Table S4. The amplified products were analysed on 1.0% agarose gels, and single fragments were recovered from the gels and purified using a QIA quick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Fragment sequences were determined by Sanger sequencing with primer L3426.

2.9. RT‐PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol from double heterozygous TALENs+/β654 mice, β654 and WT mouse tissues, followed by reverse‐transcription with Reverse Transcriptase M‐MLV (RNase H), Ribonuclease Inhibitor (Takara Biotechnology, Japan) and oligo‐dT16 primers, starting from 1 μg of total RNA. PCR was processed with the IVS‐2‐654 specific primers resulting in target fragments sized 322 bp (normal) or 395 bp (β654). The mouse glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an RT‐PCR internal control, sized 490 bp.

2.10. Western blot

Blood samples from TALENs+/β654, β654 and WT mice were collected and washed twice with phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS). After centrifugation at 3000 rpm/min for 20 min, the supernatant was discarded. Two‐fold volume of sterile water was added to pre‐treated blood for haemolysis. A 0.5‐fold of volume tetrachloromethane was then added to the haemolysed blood, and mixed for 2 min by vigorous vortex. The supernatant including haemoglobin was centrifuged at 3000 rpm/min for 15 minutes, and the resulting samples were subjected to Western blot analysis. The extracted protein was mixed with SDS‐PAGE sample buffer and electrophoresed on a 12% SDS‐PAGE (Bio‐Rad, USA). It was subsequently electrophoretically transferred to a PVDF membrane (Bio‐Rad) that was blocked overnight at 4°C with 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS containing 0.05% (w/v) Tween 20 (PBS‐T). Monoclonal mouse anti‐human β‐globin antibody (1:2000 diluted) (Abnova H00003043‐M02, Taiwan, China) and horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated rabbit anti‐mouse IgG (1:2000 diluted) (Dako P0161, Denmark) were used to detect human β‐globin. Monoclonal antibodies rabbit anti‐human α‐globin (1:2000 diluted) (Abcam ab92492, Cambridge, USA) and horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti‐rabbit IgG (1:2000) (Dako P0448, Denmark) were used to detect α‐globin as the internal control in all of the experimental mice. Blots were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence and autoradiography.

2.11. Haematologic analysis

The peripheral blood smears and bone marrow slides from the three groups of mice (TALENs+/β654, β654, WT) were stained with Wright‐Giemsa (BASO, BA4017, Zhuhai, China). Whole blood samples from the 6‐week‐old mice were collected. Red blood cell (RBC) count, haemoglobin (HGB) concentration, haematocrit (HCT), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) and mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration (MCHC) were determined by Hematology Analyzer (XT‐2000i, Sysmex, Japan) (Table 1). Reticulocyte counts were determined by using brilliant tar cresyl‐blue stain (BASO BA4003, Zhuhai, China).

Table 1.

Haematologic analyses

| Group | N | RBC (106/μL) | HGB (g/L) | HCT (%) | MCV (fL) | MCH (pg) | MCHC (g/L) | RET (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 14 | 9.42 ± 0.79a | 138.69 ± 11.28a | 42.32 ± 3.27a | 45.10 ± 3.32a | 14.74 ± 1.10a | 327.55 ± 8.37a | 3.29 ± 0.77a |

| TALENs+/β654 | 18 | 8.55 ± 0.98a | 129.56 ± 7.85a | 38.70 ± 2.57a | 49.10 ± 2.40a | 16.42 ± 1.04a | 335.16 ± 13.69a | 9.07 ± 2.08a |

| β654 | 22 | 6.50 ± 0.63 | 88.36 ± 8.43 | 25.6 ± 2.99 | 39.37 ± 2.03 | 13.65 ± 0.73 | 347.49 ± 21.53 | 28.91 ± 7.40 |

Values represent mean ± SD.

HCT, haematocrit; HGB, haemoglobin; MCH, mean corpuscular haemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; RBC, red blood cell; RET, reticulocyte.

Statistically significant differences, WT, TALENs+/β654, compared with the β654 group: a P < .01.

2.12. Histopathology

Eight‐week‐old mice from different experimental groups were used for tissue pathology analysis. Small pieces of tissue from liver and spleen were embedded in paraffin wax and sliced into 4 μm thick sections. Liver and spleen tissues were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (BASO BA4025, Zhuhai, China). Iron accumulation in liver tissues was determined by ferrocyanide iron staining (BASO BA4115, Zhuhai, China). Bone marrow smears were stained with Wright‐Giemsa (BASO BA4017, Zhuhai, China). The spleen coefficient was calculated as spleen mass divided by body mass.

2.13. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5. A Student's t test was used for inter‐group comparisons, and P values < .05 were considered significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. TALENs‐mediated deletion of the HBB IVS2‐654 C > T mutation

To disrupt incorrect splicing in the HBB IVS2 that underlies the β654‐thalassaemia, TALENs vectors were designed to directly target the IVS2‐654 C > T mutation (Figure 1A,B). The activity of these TALENs for cleavage of HBB was first tested by transfecting the TALENs vectors into the HEK293T cells. Two out of the six vector pairs, TALENL4‐R1 and TALENL4‐R4 showed the DSB activity, with a 13% and 20% efficiency respectively, as determined by the T7EI assay (Figure 1C). TALENL4‐R4 was selected for further vector optimization. Five additional vectors were constructed by modification of the promoters (CMV and CAG promoters) of the TALENL4‐R4 or with the co‐expression vectors (Figure 1B). pCAG‐R4‐IRES‐L4 (CR4‐I‐L4) demonstrated the highest cleavage efficiency (21%) among all these vectors by the T7EI assay (Figure 1D), and was selected for further experiments. PCR products amplifying the intron 2 of HBB were cloned into the T‐vector, and 40 clones were randomly selected for Sanger sequencing. Both additions and deletions of the nucleotides were detected (summarized in Figure 1E), and 50% of these clones showed successfully disruption of the target locus. No large fragment deletion was observed around the HBB IVS2‐654 site.

Whole genome sequence was searched using the software TAL Efector Nusleotide Gargeter 2.0 to identify possible off‐target sites. A total of 6732 predicted off‐target sites were obtained and the 10 with the highest scores were selected for further analysis by PCR amplification followed by the T7EI assay. HBB target site was used as the control. None of the 10 regions showed evidence of off‐target cleavage.

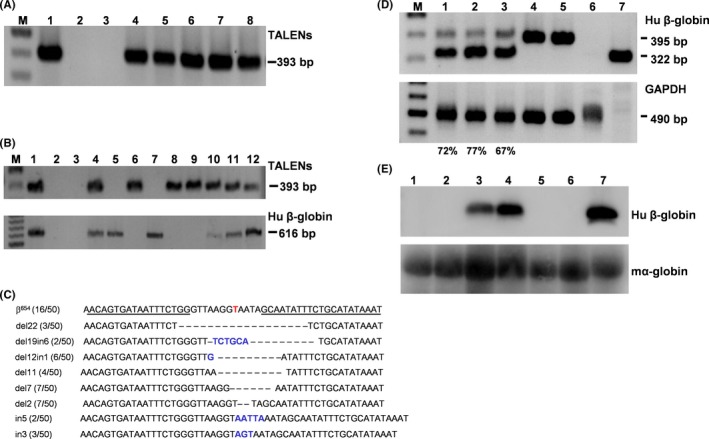

3.2. Generation and characterization of TALENs+/β654 mice

TALENs transgenic mice were generated by microinjecting the vector pCAG‐R4‐IRES‐L4 into the fertilized eggs of C57BL/6 dams. Of the 25 newborn pups, 5 carried the TALENs DNA. The genotypes were analysed by PCR as well as by Southern blot (Figure 2A and Figure S1A). Single integration site was found in four of the five transgenic founders (Table S5), while we failed to identify the definite integration site in the remaining transgenic mouse. Expression of TALENs in the transgenic mice was detected by RT‐PCR, and one mouse (F0‐5) showed a higher expression level than the others (Figure S1B). TALENs+/β654 mice was then generated by mating the TALENS transgenic founders with β654‐thalassaemia mice. Double heterozygous mice were determined by PCR analysis of tail genomic DNA (Figure 2B), and the transgene transmission to the offspring is summarized in Table S6. To further investigate the activity of TALENs in vivo, PCR amplified fragments of the HBB IVS2‐654 site from TALENs+/β654 mice were cloned using TA cloning, and followed by Sanger sequencing (Figure 2C). The efficiency of target locus disruption was analysed, and 58% of the aberrant splicing sites were successfully disrupted. No abnormalities were observed during the growth of the TALENs+/β654 mice. The TALENs+/β654 mice had much higher survival rates than the control β654 mice. Particularly, the survival rate of control β654 mice was 25.4%, while the 3‐week survival rates in F1 and F2 generation of β654 mice carrying TALENs transgene reached 43.5% and 49.2% respectively (Table S6).

Figure 2.

Identification of normal β‐globin mRNA in TALENs+/β654 mice. A, PCR analysis of TALENs transgenic mice. M, 100 bp DNA ladder; lane 1, a positive control vector; lane 2, genomic DNA from non‐transgenic mouse; lane 3, dd‐water as a blank control; lanes 4‐8, genomic DNA from transgenic mice in the following order: 3, 4, 5, 17 and 27. B, PCR analysis of TALEN +/β654 mice. M, 100bp DNA ladder; lane 1, a positive control vector; lane 2, genomic DNA from non‐transgenic mouse; lane 3, dd‐water as a blank control; lanes 4‐12, genomic DNA from mice in the following order: 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 and 29. C, Representative Sanger sequencing results of HBB IVS2‐654 mutation site from sub‐cloning of the PCR product of TALEN +/β654 mice. The HBB IVS2‐654 mutation site is indicated in red. D, RT‐PCR analysis of human β‐globin RNA. The 322 bp band indicates correct splicing and 395 bp band indicates abnormal splicing. 1‐3: TALEN +/β654 mice; 4‐5: β654 mice; 6: WT mouse; 7: human. The percentage of correct spliced β‐globin mRNA is indicated under each sample. E, Western blot analysis of human β‐globin expression. 1‐2: WT mice; 3‐4: TALENs+/β654 mice; 5‐6: β654 mice; 7: human. Mouse α‐globin as an internal control

3.3. Restoration of the correct splicing to generate normal β‐globin mRNA in TALENs+/β654 mice by TALENs‐mediated NHEJ

RT‐PCR was performed to analyse the expression of a human β‐globin gene in double heterozygous TALENs+/β654 mice. The properly spliced β‐globin transcript (322 bp) was present (Figure 2D). The percentage of normally spliced β‐globin mRNA increased from less than 15% theoretically in the β654 mice to 67% ~ 77% in the different individual TALENs+/β654 mouse (Figure 2D). Western blot analysis also confirmed the presence of normal human β‐globin protein in TALENs+/β654 mice to an evidential level (Figure 2E). These results reflected the dramatic increase of the normal β‐globin transcription in TALENs+/β654 mice mediated by TALENs induced NHEJ.

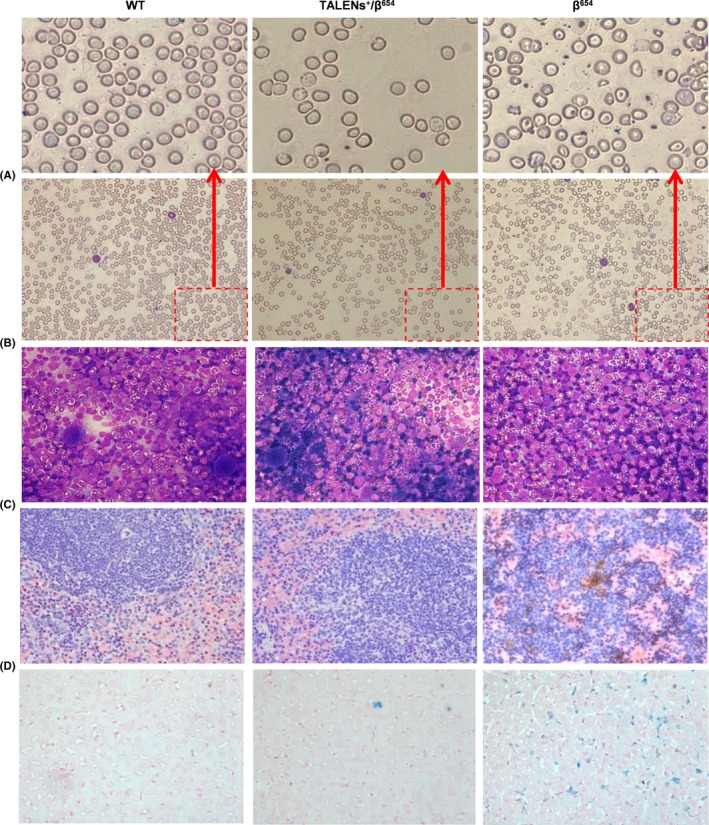

3.4. Improvement of haematologic indices in TALENs+/β654 mice

The TALENs+/β654 mice exhibited marked improvements in haematologic indices, such as RBC, HGB, HCT, MCV, MCH, MCHC and RET, when compared with the β654 mice in the control group (Table 1). Blood smears with Wright‐Giemsa staining revealed obvious reduction of poikilocytes, target cells and reticulocytes in TALENs+/β654 mice, compared with that of β654 mice (Figure 4A). Moreover, the proportion of nucleated cells in bone marrow was considerably decreased in TALENs+/β654 mice, demonstrated that abnormal bone marrow proliferation had markedly reduced (Figure 4B).

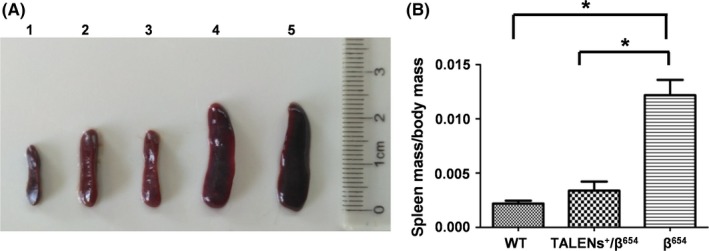

3.5. Morphology changes in spleen and liver of TALENs+/β654 mice

To determine the positive therapeutic effect of TALENs‐mediated gene editing on haematopoiesis, the extent of splenomegaly and extramedullary haematopoiesis (EMH) were examined in TALENs+/β654 mice, β654 mice and WT mice. Spleen size and weight of TALENs+/β654 mice were reduced compared with β654 mice. The spleen coefficient (spleen mass divided by body mass) of β654 mice was 3.6‐fold higher than that of the TALENs+/β654 mice (Figure 3). This improvement in TALENs+/β654 mice was consistent with histopathological analyses. In the TALENs+/β654 mice, the white pulp was significantly increased and much fewer numbers of erythroid precursors were observed in the red pulp, and the marginal zones were distinct. This is in comparison to the typical appearance of the β654 mice with red pulp expanded, white pulp decreased, and the indistinct marginal zones occupied by a significant number of nucleated RBCs. (Figure 4C). Furthermore, haemosiderin in the spleens and livers of the TALENs+/β654 mice was markedly reduced than that in the β654 mice (Figure 4C,D).

Figure 3.

Improvement of spleen pathology in TALENs+/β654 mice. A, Spleen size in TALENs+/β654 mice. 1: WT mouse; 2‐3: TALENs+/β654 mice; 4‐5: β654 mice. B, Spleen coefficient (spleen mass divided by body mass) of TALENs+/β654 mice. *Statistically significant difference from β654 mice, P < .01

Figure 4.

Improvement of RBC morphology and pathological changes in TALENs+/β654 mice tissues. A, Blood smears stained with Wright‐Giemsa (magnification 400x). B, Bone marrow slides were stained with Wright‐Giemsa (400x). C, The spleen sections were stained with haematoxylin‐eosin (400x). D, Ferrocyanide iron staining of liver samples (400x)

4. DISCUSSION

The β654‐thalassaemia consists of one of the most common types of β‐thalassaemia in China, accounting for almost 17%‐36% of the total β‐thalassaemia alleles in the Chinese population.4, 5 The molecular defect of this β654 mutation is a C→T substitution at IVS‐2 nucleotide position 654 of the HBB gene that results in the activation of an apparent 5′ donor‐like splicing acceptor leading to a non‐functional polypeptide. Given the fact that TALENs can be used to target virtually any DNA sequence of interest in humans with low off‐target efficiency, genome editing using TALENs provides a powerful approach to the treatment of human genetic diseases. Based on the underlying β654 molecular mechanism, we here described a straightforward strategy to correct the abnormal HBB splicing in β654 mice by TALENs‐mediated deletion of the mutant site. Our results demonstrated that TALENs can efficiently edit the targeting site and dramatically increase the expression of normal β‐globin proteins. The TALENs‐edited mice (TALENs+/β654 mice) showed sustained improvement of the haematologic parameters, and reduction of ineffective erythropoiesis and extramedullary haematopoiesis without observable abnormalities.

For β‐thalassaemia gene therapy, gene addition strategies have been repeatedly studied for more than 20 years. Among all the methods tested, adding a functional β‐globin gene into the genome by use of plasmids, adenovirus or lentiviral vectors, is complicated by the risk of insertional mutagenesis inherent to integrating vectors, and transgene silencing.12 The direct repair of primary mutations at the DNA level is a simple, direct and effective approach. Thus, gene editing represents an ideal alternative treatment strategy for genetic disorders, particularly for monogenic diseases such as β‐thalassaemia. Three different systems, ZFNs, TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9, have been tested to achieve high efficiency and specific gene modifications.25, 26, 27, 28 Compared with ZFNs, TALENs have considerably less cellular toxicity,29 whereas TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9 are more convenient and affordable for practical applications.30 Although CRISPR/Cas9 is cheaper and easier to utilize and could exhibit higher DSB efficiency than do TALENs,31, 32 its potential risk of off‐target events in HBB loci creates considerable concerns among scientists interested in gene therapy.33 Moreover, CRISPR/Cas9 is limited by the requirement for a PAM (NGG) sequence, and the proper sgRNAs that can directly target to the HBB IVS‐2‐654 mutation site was difficult to obtain. Therefore, TALENs represent an interesting alternative to CRISPR/Cas9 approaches in our study, as it can directly target our interesting mutant site and reduces the potential off‐target events.

In our study, we analysed the ten most potential off‐target sites of TALENs predicted by widely accepted bioinformatics tool. No off‐target event was detected, which was consistent with another study using TALENs to correct HBB IVS‐2‐654 mutation in patient‐specific iPSCs.15 With limitation of the current knowledge of TALENs and possible unknown defects of the system, we cannot completely exclude the possibility of the existence of other off‐target events. Further exploration of the correlating studies in human or their disease cells would be valuable to investigate the off‐target events before TALENs can be used in clinical application in the future.

Nucleases facilitating homologous recombination in iPSCs or HSPCs were used to correct single‐nucleotide mutations.15, 16, 17 However, the low efficiency of HDR hindered their further application in pursuit of an effective therapy. Increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of gene editing remains a challenge. Our study demonstrated that NHEJ deletion of the target mutation greatly improved the gene correction efficiency in this disease model. Over 50% of the animal tested had the HBB IVS2‐654 mutation sites deletion, and normal β‐globin splicing product reached as high as 77% of total β‐globin in the TALENs+/β654 mice. In addition, no large fragment deletion was detected by Sanger sequencing at the HBB IVS2‐654 site, which could be a positive sign for limiting adverse effects of HBB introduced by TALENs‐mediated NHEJ. Moreover, TALENs were expressed throughout lifespan, either in TALENs created transgenic mice, or TALENs+/β654 mice. So far, no obvious physiological abnormality was detected, demonstrating that the lengthy expression of TALENs protein was relatively safe in those mice bearing the TALENs transgene. However, insertion of a random sequence, which is inherently associated with the NHEJ, might still potentially introduce undesirable mutations into the targeted region. This concern has to be further investigated when TALENs‐mediated gene therapy is intended for human clinical use. Therefore, improving the efficiency of NHEJ‐mediated deletion and avoiding random insertion may be the next direction to focus for successful gene therapy approaches.

The β654 mice used in our study exhibited the classical clinical signs of the moderate to severe form of β‐thalassaemia. It is characterized by having a low RBC count, increased RBC disruption and ineffective erythropoiesis.34 Our previous study demonstrated that this model closely replicated the symptoms characteristic of human β654‐thalassaemia, and detailed the therapeutic effects following different treatments.7, 8, 10, 35, 36 In the present study, the haematologic parameters of TALENs+/β654 mice were significantly improved, including increased RBC and HGB, and reduced RET, resulting by the increased synthesis of normal human β‐globin detected at both the transcriptional and protein levels. The therapeutic effects were further verified by histopathology review of bone marrow, spleen and liver, which showed amelioration of splenomegaly, extramedullary haematopoiesis and iron haemosiderin of liver in TALENs+/β654 mice. Noteworthy, the expression of the correctly spliced normal β‐globin increased from less than 15% in the β654 mice to up to 77% of some of the TALENs+/β654 mice. It is notable that β654 genome type was not totally corrected, and there was still a small amount of abnormal spliced product present; however, clinically the treated mice (TALENs+/β654 mice) already represent a switch from moderate to severe thalassaemia syndrome to mild thalassaemia syndrome, and thereafter a remarkable amelioration of the thalassaemia phenotype. It suggests that patients with similar anaemia degree represented by the TALENs+/β654 mice could live a normal life without further treatment. Our study proposes that TALENs‐mediated deletion of HBB IVS2‐654 mutation site has great potential to efficiently alleviate the thalassaemia symptoms in patients.

In summary, our study showed that TALENs‐mediated deletion of HBB IVS2‐654 mutation site has great potential to efficiently alleviate the thalassaemia symptoms, and continuous optimization of the nucleases to eliminate the potential risks such as off‐target effect and insertion mutagenesis is needed before their clinical application.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors disclose no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Prof. Yitao Zeng for his helpful suggestions in experiment design, and to Profs. Zhaorui Ren and Richard H. Finnell for their help in manuscript editing. This work was supported by the grants from: the National Basic Research Program of China (2014CB964701 and 2014CB964703), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81570172), the Shanghai Municipal Natural Science Foundation (16ZR1428600), Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning Grant (201640228 and 20164Y0070), the Experimental Animals Project of Shanghai Municipality (18140901600 and 18140901601), the Shanghai Sailing Program (18YF1420300), and Project of Academician Workstation at KingMed Dianostic (2017B090904030).

Fang Y, Cheng Y, Lu D, et al. Treatment of β654‐thalassaemia by TALENs in a mouse model. Cell Prolif. 2018;51:e12491 10.1111/cpr.12491

Yudan Fang, Yan Cheng, and Dan Lu are the authors contributed equally to this work.

Funding Information

The National Basic Research Program of China, Grant/Award Number: 2014CB964701 and 2014CB964703; the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant/Award Number: 81570172; the Shanghai Municipal Natural Science Foundation, Grant/Award Number: 16ZR1428600; Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning Grant, Grant/Award Number: 201640228 and 20164Y0070; the Experimental Animals Project of Shanghai Municipality Grant/Award Number: 18140901600 and 18140901601; the Shanghai Sailing Program Grant/Award Number: 18YF1420300; Project of Academician Workstation at KingMed Diagnostics Grant/Award Number: 2017B090904030.

REFERENCES

- 1. Modell B, Darlison M. Global epidemiology of haemoglobin disorders and derived service indicators. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:480‐487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Olivieri NF, Nathan DG, MacMillan JH, et al. Survival in medically treatedpatients with homozygous beta‐thalassemia. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:574‐578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang JZ, Yan JB, Zeng F. Recent Progress on Genetic Diagnosis and Therapy for β‐Thalassemia in China and Around the World. Hum Gene Ther. 2018;29:197‐203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang SZ, Zhou XD, Zhu H, et al. Detection of beta‐thalassemia mutations in the Chinese using amplified DNA from dried blood specimens. Hum Genet. 1990;84:129‐131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huang SZ, Zeng FY, Ren ZR, et al. RNA transcripts of the beta‐thalassaemia allele IVS‐2‐654 C–>T: a small amount of normally processed beta‐globin mRNA is still produced from the mutant gene. Br J Haematol. 1994;88:541‐546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheng TC, Orkin SH, Antonarakis SE, et al. b‐Thalassemia in Chinese: use of in vivo RNA analysis and oligonucleotide hybridization in systematic characterization of molecular defects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:2821‐2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xie SY, Ren ZR, Zhang JZ, et al. Restoration of the balanced alpha/beta‐globin gene expression in beta654‐thalassemia mice using combined RNAi and antisense RNA approach. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2616‐2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xie SY, Li W, Ren ZR, et al. Correction of beta654‐thalassaemia mice using direct intravenous injection of siRNA and antisense RNA vectors. Int J Hematol. 2011;93:301‐310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xie S, Li W, Ren Z, et al. Amelioration of beta654‐thalassemia in mouse model with the knockdown of aberrantly spliced beta‐globin mRNA. J Genet Genomics. 2008;35:595‐601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li W, Xie S, Guo X, et al. A novel transgenic mouse model produced from lentiviral germline integration for the study of beta‐thalassemia gene therapy. Haematologica. 2008;93:356‐362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hanawa H, Hargrove PW, Kepes S, et al. Extended beta‐globin locus control region elements promote consistent therapeutic expression of a gamma‐globin lentiviral vector in murine beta‐thalassemia. Blood. 2004;104:2281‐2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rivella S, Sadelain M. Genetic treatment of severe hemoglobinopathies: the combat against transgene variegation and transgene silencing. Semin Hematol. 1998;35:112‐125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hacein‐Bey‐Abina S, Garrigue A, Wang GP, et al. Insertional oncogenesis in 4 patients after retrovirus‐mediated gene therapy of SCID‐X1. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3132‐3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cavazzana‐Calvo M, Payen E, Negre O, et al. Transfusion independence and HMGA2 activation after gene therapy of human beta‐thalassaemia. Nature. 2010;467:318‐322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xu P, Tong Y, Liu XZ, et al. Both TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9 directly target the HBB IVS2‐654 (C > T) mutation in beta‐thalassemia‐derived iPSCs. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ma N, Liao B, Zhang H, et al. Transcription activator‐like effector nuclease (TALEN)‐mediated gene correction in integration‐free beta‐thalassemia induced pluripotent stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:34671‐34679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xie F, Ye L, Chang JC, et al. Seamless gene correction of beta‐thalassemia mutations in patient‐specific iPSCs using CRISPR/Cas9 and piggyBac. Genome Res. 2014;24:1526‐1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Song B, Fan Y, He W, et al. Improved hematopoietic differentiation efficiency of gene‐corrected beta‐thalassemia induced pluripotent stem cells by CRISPR/Cas9 system. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24:1053‐1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Niu X, He W, Song B, et al. Combining single strand oligodeoxynucleotides and CRISPR/Cas9 to correct gene mutations in beta‐Thalassemia‐induced Pluripotent stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:16576‐16585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cai L, Bai H, Mahairaki V, et al. A Universal approach to correct various HBB gene mutations in human stem cells for gene therapy of beta‐Thalassemia and sickle cell disease. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2018;7:87‐97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chu VT, Weber T, Wefers B, et al. Increasing the efficiency of homology‐directed repair for CRISPR‐Cas9‐induced precise gene editing in mammalian cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:543‐548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Genovese P, Schiroli G, Escobar G, et al. Targeted genome editing in human repopulating haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2014;510:235‐240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Doyle EL, Booher NJ, Standage DS, et al. TAL Effector‐Nucleotide Targeter (TALE‐NT) 2.0: tools for TAL effector design and target prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W117‐W122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu YG, Chen Y. High‐efficiency thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR for amplification of unknown flanking sequences. Biotechniques. 2007;43:649‐650, 652, 654 passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hockemeyer D, Soldner F, Beard C, et al. Efficient targeting of expressed and silent genes in human ESCs and iPSCs using zinc‐finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:851‐857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hockemeyer D, Wang H, Kiani S, et al. Genetic engineering of human pluripotent cells using TALE nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:731‐734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819‐823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, et al. RNA‐guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823‐826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Voit RA, Hendel A, Pruett‐Miller SM, et al. Nuclease‐mediated gene editing by homologous recombination of the human globin locus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:1365‐1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim H, Kim JS. A guide to genome engineering with programmable nucleases. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:321‐334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smith C, Abalde‐Atristain L, He C, et al. Efficient and allele‐specific genome editing of disease loci in human iPSCs. Mol Ther. 2015;23:570‐577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ding Q, Regan SN, Xia Y, et al. Enhanced efficiency of human pluripotent stem cell genome editing through replacing TALENs with CRISPRs. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:393‐394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cradick TJ, Fine EJ, Antico CJ, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 systems targeting beta‐globin and CCR5 genes have substantial off‐target activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:9584‐9592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lewis J, Yang B, Kim R, et al. A common human beta globin splicing mutation modeled in mice. Blood. 1998;91:2152‐2156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yang G, Shi W, Hu X, et al. Therapeutic effects of induced pluripotent stem cells in chimeric mice with beta‐thalassemia. Haematologica. 2014;99:1304‐1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang B, Fang Y, Guo X, et al. Transgenic human alpha‐hemoglobin stabilizing protein could partially relieve betaIVS‐2‐654‐thalassemia syndrome in model mice. Hum Gene Ther. 2010;21:149‐156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials