Abstract

The digestive system cancers are leading cause of cancer‐related death worldwide, and have high risks of morbidity and mortality. More and more long non‐coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been studied to be abnormally expressed in cancers and play a key role in the process of digestive system tumour progression. Plasmacytoma variant translocation 1 (PVT1) seems fairly novel. Since 1984, PVT1 was identified to be an activator of MYC in mice. Its role in human tumour initiation and progression has long been a subject of interest. The expression of PVT1 is elevated in digestive system cancers and correlates with poor prognosis. In this review, we illustrate the various functions of PVT1 during the different stages in the complex process of digestive system tumours (including oesophageal cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma and pancreatic cancer). The growing evidence shows the involvement of PVT1 in both proliferation and differentiation process in addition to its involvement in epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT). These findings lead us to conclude that PVT1 promotes proliferation, survival, invasion, metastasis and drug resistance in digestive system cancer cells. We will also discuss PVT1's potential in diagnosis and treatment target of digestive system cancer. There was a great probability PVT1 could be a novel biomarker in screening tumours, prognosis biomarkers and future targeted therapy to improve the survival rate in cancer patients.

1. INTRODUCTION

Cancer of the digestive system is the leading cause of cancer‐related death worldwide. Among all the types of cancers, the incidence of gastric cancer (GC), hepatocellular cancer (HCC) and colorectal cancer (CRC) is high with a high mortality rate.1, 2 The prognosis of patient with digestive system cancers depends mostly upon the stage of the cancer at the time of diagnosis. However, current therapeutic methods for advanced stage cancers still have some limitations and it is hard to detect the cancers at their early stages due to the lack of efficient biomarkers. Therefore, identification of these potential efficient biomarkers may help in the early stage diagnosis of such cancers.

Recently, long non‐coding RNAs (lncRNAs), a subclass of non‐coding RNAs with >200 nucleotides, has been studied to be abnormally expressed in digestive system cancers and has a key role in the course of tumour development. Recently, several studies have focused on analysing their mechanisms and networks to expose their role in development of cancer. Among lncRNAs, Plasmacytoma variant translocation 1 (PVT1) seems fairly important. PVT1 belongs to lncRNA class, and is encoded by the PVT1 gene (also known as the Pvt1 oncogene). In 1984, PVT1 was identified as an activator of MYC in plasmacytoma variant translocations in mice.3 In humans, PVT1 is located on chromosomal 8q24.21, as a large locus (>30 kb) from 128806779 to 129113499, about 57 kb distant from and downstream of the c‐Myc gene.4, 5

Amplification of 8q24 encoded c‐Myc and PVT1 are often found in varieties of human malignancies. Coamplication of human PVT1 and c‐Myc has been found to be associated with rapid progression of breast cancer as well as poor clinical survival in breast cancer.6 PVT1 and c‐Myc may serve as transcription activator to each other.7 Six annotated miRNAs produced by PVT1 have been discovered, including miR‐1204, miR‐1205, miR‐1206, miR‐1207‐3p, miR‐1207‐5p and miR‐1208.8 But the relationships between PVT1 and other factors remain largely unknown.

The dysregulation of PVT1 was found in varieties of human diseases. PVT1 was reported to mediate the development of diabetic nephropathy through extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulation.9 The expression of PVT1 was low in normal tissue but its expression was found to be highly increased in transformed cell lines.8, 10 Amplification of PVT1 is one of the most frequent events in several human malignancies,11, 12, 13 such as thyroid carcinoma,14 bladder cancer,15 malignant pleural mesothelioma,16 prostate cancers and etc.17, 18, 19 PVT1 promoted cell proliferation, migration and invasion in non‐small cell lung cancer by regulating LATS2 expression, DNA rearrangements and amplifications.11, 20 It was also associated with poor prognosis in cervical cancer patients.13 Overexpression of PVT1 has contributed to the pathophysiology of ovarian and breast cancer,12 and cause cisplatin resistance by regulating apoptotic relevant pathways.21 To sum, various studies have revealed that PVT1 plays significant roles in tumourogenesis, making it a potential cancer biomarker.

Plasmacytoma variant translocation 1 was found to be up‐regulated in human tumours, especially in digestive system cancers. However, its clinical significance in digestive system tumours remains obscured. In this review, we will discuss the biological functions of PVT1 in digestive system cancers (Table 1). PVT1 will be a potentially useful tool for the diagnosis and treatment targeting of digestive system tumours.

Table 1.

Functional characterization of Plasmacytoma variant translocation 1 (PVT1) in various digestive system cancers

| Cancer types | Related gene | Expression | Phenotypes affected | Role | Protein binding | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oesophageal cancer | — | Up‐regulated | Proliferation, invasion | Oncogenic, ceRNAs | — | 28, 29 |

| Gastric cancer | CD151, FGF2, miR‐152; EZH2; MDR1, MRP, mTOR and HIF‐1α; miR‐186, HIF‐1α | Up‐regulated | Proliferation, metastasis, anti‐apoptosis, invasion | Oncogenic | P15, p16; FOXM1 | 34‐36, 39, 41 |

| Colorectal cancer | c‐Myc,NPM1, FUBP1, EZH2 | Up‐regulated | Proliferation, invasion, anti‐apoptotic | Oncogenic | — | 52, 53 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | miR‐152 | Up‐regulated | Proliferation, cell cycling and the stem cell‐like properties | Oncogenic | NOP2 | 57, 59 |

| Pancreatic Cancer | p21 | Up‐regulated | Proliferation migration, and EMT | Oncogenic | — | 66‐68 |

EMT: mesenchymal transition; HIF‐1α: Hypoxia‐ inducible factor 1‐alpha; MDR1: Multidrug Resistance 1.

2. OESOPHAGEAL CANCER

Oesophageal cancer is the sixth most common cause of cancer death among males and the ninth most common cause of cancer death among females worldwide.2 In 2010, the data of China showed that the morbidity and mortality of oesophageal cancer were 21.88/100000 and 15.85/100000, respectively.7 Even though, pathogenesis of oesophageal cancer is still unclear, several factors appear as consistent reasons such as tobacco, alcohol, reflux oesophagitis, dietary habits, nutrition, along with environmental factors.22 Currently, there are no ideal biomarkers, which can be used in screening oesophageal cancer strategies.23 LncRNA nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 (NEAT1), LncRNA ANRIL, HOX transcript anti‐sense intergenic RNA (HOTAIR) and SOX2 overlapping transcript (SOX2OT) were found to be associated with oesophageal cancer.24, 25, 26, 27

Epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a biological process in which epithelial cells lost cell polarity, adhesion properties, but obtain migratory and invasive abilities become multipotent mesenchymal stem cells. Decreased E‐cadherin and increased N‐cadherin are the hallmarks for the EMT. EMT is a vital step in cancer progression, invasion and metastasis.

In the last 2 years, role of PVT1 in development and progression of oesophageal cancer has attracted the attention of several scholars. PVT1 was associated with tumour stage, metastasis, as well as regulating the cell invasion in vitro by inducing EMT.28

They further observed that PVT1 contributes to the regulation of EMT markers expression (E‐cadherin, N‐cadherin and vimentin) in cell lines. Yang et al29reported that the function of PVT1 as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) on the basis of co‐expression network between mRNAs and lncRNAs. By proving that the miR‐186‐mediated PVT1‐mRNA network is associated with the ESCC, they suggested the roles of PVT1 in tumourogenesis, metastasis, along with the diagnosis of ESCC. Though the specific underlying mechanisms are not elucidated yet, the signalling pathways between PVT1 and EMT may be explored as a future therapeutic approach for the treatment of oesophageal cancer.

3. GASTRIC CANCER

Being a disease of high mortality, GC is the second commonest cause of cancer‐related death worldwide.2 In 2011, more than 400 000 patients were diagnosed with GC in China, among which there were estimated 300 000 deaths in China.30 The epidemiology study illustrated that environmental factors and lifestyles are key contributors to the aetiology of GC.31 Though, the treatment option for GC patients is still challenging, surgery and systemic chemotherapy are the mainstay treatments.32 Nevertheless, the exact molecular mechanism of GC is still obscured. Several genetic alterations are involved in the predisposition to GC, such as oncogenes, tumour suppressor genes and growth factors.33 Hence, it is urgent to find specific biomarkers in the diagnosis of GC and investigate therapeutic targets for GC.

Up‐regulation of PVT1 was found in human GC tissues in comparison with matched normal tissues or cell lines.34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42 A close relationship between PVT1 up‐regulation and tumour size,41 invasion depth,36, 41, 42 advanced TNM stage,36, 39, 40, 41, 42 and regional lymph nodes metastasis37, 39, 41, 42 was noted in GC patients. These findings show that PVT1 might play an important role in GC development and tumourogenesis, which may be associated with poor prognosis. Xu et al41 revealed PVT1 stimulates tumour progression through interacting with FOXM1, along with a positive feedback loop of PVT1‐FOXM1 in GC, which could be a novel target in therapeutic methods. Besides, FOXM1 directly connects the PVT1 promoter to initiate the transcription. Zeste homologue 2 (EZH2) was reported to be involved in tumours in a FOXM1‐dependent manner, and PVT1 was also found to connect with the enhancer of EZH2, promoting the proliferation of GC cells via the p15 and p16 repression network.36 While Xu et al41 in his study revealed that PVT1 and FOXM1 did not affect the protein expression of EZH2, indicating that the interaction among EZH2, FOXM1 and PVT1 may be complex and the regulatory factors may vary in different cells.

Clinically, the overexpression of PVT1 was specifically associated with deeper invasion depth, as well as advanced TNM stages. PVT1 plays an important role in G1 arrest.36 Another study revealed that PVT1 might act as a “sponge” to hinder miR‐152 in GC cells.34 MiR‐152 has been found to act as a tumour suppressor in various types of cancer.43, 44 CD151and FGF2, which were the target genes of miR‐152, act as a critical promoter for cell proliferation, metastasis, as well as tumour angiogenesis.45, 46 PVT1 could prevent the expression of miR‐152 and improve the expression of CD151 and FGF2 via regulating miR‐152 in GC.34 Further functional experiment suggested that up‐regulation of PVT1 stimulates the proliferation and invasion in GC cells by negatively regulating miR‐186. PVT1 directly interacts with miR‐186, leading to the inhibition of downstream of Hypoxia‐ inducible factor 1‐alpha (HIF‐1α) expression.39 HIF‐1α is the major transcription factor and its overexpression is associated with poor overall survival in GC patient's post‐gastrectomy.47, 48 Improved HIF‐1 activity stimulates tumour progression, so inhibition of PVT1/miR‐186/HIF‐1α pathway could be an effective method for cancer treatment.49

Multidrug Resistance (MDR) is one of the major reasons for therapy failure in GC, which leads to recurrence and metastasis of GC. PVT1 was overexpressed both in tissues and cells in cisplatin‐resistant patients. Overexpression of PVT1 has anti‐apoptotic activity, and improves the expression of MDR‐related genes such as MDR1, mTOR, MRP as well as HIF‐1α in cisplatin‐resistant GC cells. PVT1 might stimulate the development of MDR via regulation of mTOR/HIF‐1α/P‐gp along with MRP1 signalling pathway in MDR‐gastric cancer.35 The underlying mechanism of PVT1 in apoptosis induction is still not clear, so further study is needed.

In conclusion, PVT1 has been found to be linked with tumour suppressor or oncogenic pathways of GC,37 and altered expression of PVT1 was associated with the occurrence and development of GC (Figure 1). This finding provides evidence that PVT1 may be considered as a candidate detection biomarker as well as a novel therapeutic target in GC.

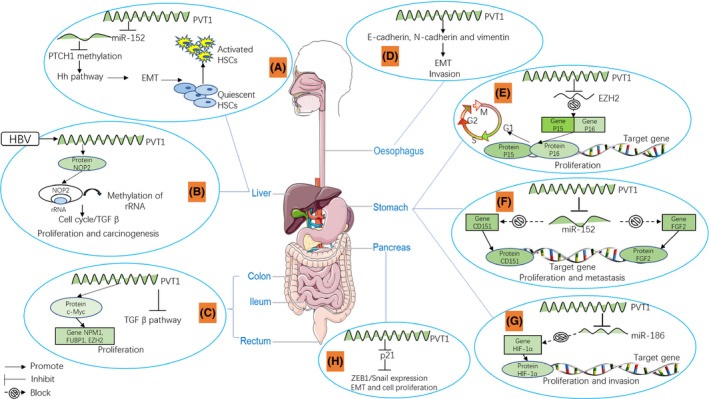

Figure 1.

LncRNA PVT1 expression changes during the development of digestive system cancers (A). PVT1 down‐regulates PTCH1 expression via binding with miR‐152, PTCH1 methylation leading to activation of Hh pathway, through the mesenchymal transition (EMT) process there is activation of hepatic stellate cells; (B) TGF‐β1 up‐regulates the expression of lncRNA‐hPVT1, promoting the proliferation and stem cell‐like property of hepatocellular cancer (HCC) cells by enhancing the stability of NOP2 proteins; (C). PVT1 is linked with c‐Myc protein, and the upper‐stream regulator of c‐Myc FUBP1, EZH2, and NPM1 to promote cell proliferation additionally by inhibiting TGF‐β pathway; (D). lncRNA PVT1 induces EMT invasion by regulating the expression levels of E‐cadherin, N‐cadherin and vimentin; (E). PVT1 inhibits EZH2 expression and causes obvious G1 phase arrest by affecting the expression of p15 and p16; (F). PVT1 increases the expression of CD151 and FGF2 through inhibiting the expression of miR‐152; (G). PVT1 directly targets as well as inhibits both miR‐186 and protein expression levels of the HIF‐1α in gastric cancer (GC) cells; (H). PVT1 promotes p21 expression, down‐regulates zinc finger E‐box‐binding protein 1 (ZEB1)/Snail expression, then induces the cell proliferation and migration

4. COLORECTAL CANCER (CRC)

Colorectal cancer is the third most common malignancy and has the third highest mortality rate in the United States.50 Although, the death rate has declined for several decades due to the adoption of screening strategies and the improvement of standard treatment,51 the occurrence of relapses and the unfavourable prognosis still significantly influences the result of treating CRC.

Guo et al52 found that the expression of PVT1 in CRC tissues was higher in comparison with that in normal tissues, which was associated with the expression of c‐Myc and c‐Myc regulating genes NPM1, FUBP1, along with EZH2. It was also associated with the expression of two other PVT1‐related transcript factors nuclear factor‐κB, as well as myocyte‐specific enhancer factor 2A. Down‐regulation of the PVT1 expression suppressed the expression of c‐Myc, inhibited cell proliferation and induced cell apoptosis in CRC. These findings indicate that PVT1 might be an important oncogene co‐amplified with c‐Myc in CRC tissues and functionally associated with the proliferation and apoptosis of CRC cells. In relation to prognosis, Takahashi et al53 indicates that CRC cells transfected with PVT1 siRNA show significant loss of proliferation and invasion capabilities. The TGF‐β signalling pathway and apoptotic signals were notably stimulated in these cells. Moreover, multivariate analysis explains that the level of PVT1 expression is an independent risk factor for the survival of CRC patients. PVT1 has anti‐apoptotic activity in CRC, and abnormal PVT1 expression was a key prognostic indicator for CRC patients, though further studies are needed to explore the underlying mechanism of PVT1‐inhibited apoptosis. In addition, the prognostic value of c‐Myc in CRC was not verified in this study, indicating that the interaction of c‐Myc and PVT1 may vary in different human malignancies. As a conclusion, PVT1 may act as an important diagnostic marker and therapeutic target of CRC, and further studies are required to confirm these findings.

5. HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA

Hepatocellular cancer is the most common primary cancer of the liver. Even though several diagnostic and treatment techniques are available for HCC, it has a very poor prognosis.54, 55

Patched1 (PTCH1) negatively regulates the Hedgehog (Hh) pathway. MicroRNA‐152 (miR‐152) prevents liver fibrosis from decreasing PTCH1 methylation.56 PVT1 down‐regulates PTCH1 expression through competitively binding miR‐152, contributing to EMT process in liver fibrosis.57 In addition, PVT1 and uc002mbe.2 in sera provides a novel supplementary method for the diagnosis of HCC, which were related to tumour size, serum bilirubin and Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stages.58 Further analysis showed that the expression level of PVT1 was significantly elevated in HCC tissues and patients with up‐regulated PVT1 had a poor clinical prognosis. The pro‐tumourigenic effect of PVT1 on cell proliferation, cell cycling and stem cell‐like properties of HCC cells were detected by stabilizing the NOP2 protein both in vitro and in vivo. The lncRNA‐PVT1/NOP2 pathway may play an important role in the treatment of HCC.59As a conclusion, PVT1 may act as an oncogene in HCC, suggesting its beneficial effects as a prognostic marker and a therapeutic target.

6. PANCREATIC CANCER (PC)

Pancreatic cancer is the seventh most common cause of cancer death worldwide.2 However, it has the poorest survival rate among all types of cancers. Till now, the overall 5‐year survival rate of PC patients is less than 5%, without apparent improvement over the past two decades.60 Currently, there is only one biomarker, carbohydrate antigen 19‐9 (CA19‐9), which is approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).61 However, significant limitations of CA19‐9 also exist, including poor sensitivity, increased false positivity in obstructive jaundice patients (10%‐60%) and false negative results in Lewis negative phenotypes (5%‐10%).62 Additionally, normal CA19‐9 level is also found in patients with localized diseases, and overexpressed CA19‐9 levels may also exist in some bile duct diseases such as cholangitis, calculus of bile duct, non‐malignant jaundice, along with cholangiocarcinoma.63, 64, 65 Therefore, it is urgent to find specific and sensitive biomarker for PC to improve clinical outcomes.

Till now, several lncRNAs, such as H19, HOTAIR, along with MALAT1 (metastasis‐associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1) are most closely correlated with PC. Other several studies also supported the PVT1 as an important biomarker. As shown in many previous studies, Wu et al66 noted that PVT1 expression was drastically found to be up‐regulated in PC tissues or cell lines in comparison with normal groups. They also found PVT1 stimulates EMT, cell proliferation, along with migration via down‐regulating p21 in PC cells. P21 may present as a mediator because p21 could down‐regulate the expression of ZEB1 and Snail. But further study is required to prove these regulatory relationships in vivo.

When both salivary HOTAIR and PVT1 were combined for the diagnosis of PC, Xie et al67 found that their combination had good sensitivity and specificity. This result implies that salivary HOTAIR and PVT1 could be a novel non‐invasive and specific biomarker for the detection of PC. However, these findings still need large‐scale validation.

To investigate the relationship between PVT1 and prognosis of PC, Huang et al68 found that increased expression of the PVT1 is correlated with tumour progression and multivariate cox regression analyses. This study revealed that PVT1 could be an independent prognostic factor for poor overall survival rate in PC patients.

7. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Plasmacytoma variant translocation 1 is a comparatively well‐characterized oncogenic lncRNA, which is up‐regulated in cancers, especially in many digestive system cancers, which includes oesophageal cancer, GC, HCC, CRC and PC. We reviewed PVT1 interaction with DNA, RNA, as well as related proteins in occurrence of digestive system cancers. It is tempting to speculate that PVT1 may interrupt definitive steps in numerous digestive system cancer suppressive and oncogenic pathways. PVT1 could promote tumour cell proliferation, migration and invasion. PVT1 up‐regulation is usually associated with poor prognosis. PVT1 will be a potentially useful biomarker for diagnosis and therapeutic targets of digestive system tumours. However, there is still lack of the independent cohort study for validation. Thus, multicentre studies will be needed, which can enhance the clinical utility of PVT1 as an effective biomarker.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

Zhou D‐D, Liu X‐F, Lu C‐W, Pant OP, Liu X‐D. Long non‐coding RNA PVT1: Emerging biomarker in digestive system cancer. Cell Prolif. 2017;50:e12398 10.1111/cpr.12398

Funding information

This work was supported by grants from The First Hospital of Jilin University Grant (grant number JDYY72016055).

Contributor Information

Cheng‐wei Lu, Email: lcwchina800@sina.com.

Xiao‐dong Liu, Email: doriszhoudan0928@sina.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pan R, Zhu M, Yu C, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality: a cohort study in China, 2008‐2013. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:1315‐1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet‐Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cory S, Graham M, Webb E, Corcoran L, Adams JM. Variant (6;15) translocations in murine plasmacytomas involve a chromosome 15 locus at least 72 kb from the c‐myc oncogene. EMBO J. 1985;4:675‐681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shtivelman E, Henglein B, Groitl P, Lipp M, Bishop JM. Identification of a human transcription unit affected by the variant chromosomal translocations 2;8 and 8;22 of Burkitt lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3257‐3260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shtivelman E, Bishop JM. Effects of translocations on transcription from PVT. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1835‐1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cui M, You L, Ren X, Zhao W, Liao Q, Zhao Y. Long non‐coding RNA PVT1 and cancer. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun. 2016;471:10‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen W, Zheng R, Zhang S, Zhao P, Zeng H, Zou X. Report of cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2010. Ann Transl Med. 2014;2:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barsotti AM, Beckerman R, Laptenko O, Huppi K, Caplen NJ, Prives C. p53‐Dependent induction of PVT1 and miR‐1204. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2509‐2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alvarez ML, DiStefano JK. Functional characterization of the plasmacytoma variant translocation 1 gene (PVT1) in diabetic nephropathy. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e18671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carramusa L, Contino F, Ferro A, et al. The PVT‐1 oncogene is a Myc protein target that is overexpressed in transformed cells. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:511‐518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yang YR, Zang SZ, Zhong CL, Li YX, Zhao SS, Feng XJ. Increased expression of the lncRNA PVT1 promotes tumorigenesis in non‐small cell lung cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:6929‐6935. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guan Y, Kuo WL, Stilwell JL, et al. Amplification of PVT1 contributes to the pathophysiology of ovarian and breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5745‐5755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Iden M, Fye S, Li K, Chowdhury T, Ramchandran R, Rader JS. The lncRNA PVT1 contributes to the cervical cancer phenotype and associates with poor patient prognosis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0156274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhou Q, Chen J, Feng J, Wang J. Long noncoding RNA PVT1 modulates thyroid cancer cell proliferation by recruiting EZH2 and regulating thyroid‐stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR). Tumour Biol. 2016;37:3105‐3113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhuang C, Li J, Liu Y, et al. Tetracycline‐inducible shRNA targeting long non‐coding RNA PVT1 inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis in bladder cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:41194‐41203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Riquelme E, Suraokar MB, Rodriguez J, et al. Frequent coamplification and cooperation between C‐MYC and PVT1 oncogenes promote malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:998‐1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu HT, Fang L, Cheng YX, Sun Q. LncRNA PVT1 regulates prostate cancer cell growth by inducing the methylation of miR‐146a. Cancer Med. 2016;5:3512‐3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bawa P, Zackaria S, Verma M, et al. Integrative analysis of normal long intergenic non‐coding rnas in prostate cancer. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0122143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meyer KB, Maia AT, O'Reilly M, et al. A functional variant at a prostate cancer predisposition locus at 8q24 is associated with PVT1 expression. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wan L, Sun M, Liu GJ, et al. Long noncoding RNA PVT1 promotes non‐small cell lung cancer cell proliferation through epigenetically regulating LATS2 expression. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:1082‐1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu E, Liu Z, Zhou Y, Mi R, Wang D. Overexpression of long non‐coding RNA PVT1 in ovarian cancer cells promotes cisplatin resistance by regulating apoptotic pathways. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:20565‐20572. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Palladino‐Davis AG, Mendez BM, Fisichella PM, Davis CS. Dietary habits and esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. Jan 2015;28:59‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gao QY, Fang JY. Early esophageal cancer screening in China. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;29:885‐893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shahryari A, Jazi MS, Samaei NM, Mowla SJ. Long non‐coding RNA SOX2OT: expression signature, splicing patterns, and emerging roles in pluripotency and tumorigenesis. Front Genet. 2015;6:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li Z, Yu X, Shen J. ANRIL: a pivotal tumor suppressor long non‐coding RNA in human cancers. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:5657‐5661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yu X, Li Z, Zheng H, Chan MT, Wu WK. NEAT1: a novel cancer‐related long non‐coding RNA. Cell Prolif. 2017;50 10.1111/cpr.12329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Song W, Zou SB. Prognostic role of lncRNA HOTAIR in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;463:169‐173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zheng X, Hu H, Li S. High expression of lncRNA PVT1 promotes invasion by inducing epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition in esophageal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:2357‐2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang S, Ning Q, Zhang G, Sun H, Wang Z, Li Y. Construction of differential mRNA‐lncRNA crosstalk networks based on ceRNA hypothesis uncover key roles of lncRNAs implicated in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:85728‐85740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Di Gesualdo F, Capaccioli S, Lulli M. A pathophysiological view of the long non‐coding RNA world. Oncotarget. 2014;5:10976‐10996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Crew KD, Neugut AI. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:354‐362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kanat O, O'Neil BH. Metastatic gastric cancer treatment: a little slow but worthy progress. Med Oncol. 2013;30:464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li T, Meng XL, Yang WQ. Long noncoding RNA PVT1 acts as a “Sponge” to inhibit microRNA‐152 in gastric cancer cells. Dig Dis Sci. 2017. 10.1007/s10620-017-4508-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang XW, Bu P, Liu L, Zhang XZ, Li J. Overexpression of long non‐coding RNA PVT1 in gastric cancer cells promotes the development of multidrug resistance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;462:227‐232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kong R, Zhang EB, Yin DD, et al. Long noncoding RNA PVT1 indicates a poor prognosis of gastric cancer and promotes cell proliferation through epigenetically regulating p15 and p16. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ding J, Li D, Gong M, et al. Expression and clinical significance of the long non‐coding RNA PVT1 in human gastric cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:1625‐1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cao WJ, Wu HL, He BS, Zhang YS, Zhang ZY. Analysis of long non‐coding RNA expression profiles in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3658‐3664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Huang T, Liu HW, Chen JQ, et al. The long noncoding RNA PVT1 functions as a competing endogenous RNA by sponging miR‐186 in gastric cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;88:302‐308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li T, Mo X, Fu L, Xiao B, Guo J. Molecular mechanisms of long noncoding RNAs on gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:8601‐8612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xu MD, Wang Y, Weng W, et al. A Positive Feedback Loop of lncRNA‐PVT1 and FOXM1 Facilitates Gastric Cancer Growth and Invasion. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:2071‐2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yuan CL, Li H, Zhu L, Liu Z, Zhou J, Shu Y. Aberrant expression of long noncoding RNA PVT1 and its diagnostic and prognostic significance in patients with gastric cancer. Neoplasma. 2016;63:442‐449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li B, Xie Z, Li B. miR‐152 functions as a tumor suppressor in colorectal cancer by targeting PIK3R3. Tumour Biol. Aug 2016;37:10075‐10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhu C, Li J, Ding Q, et al. miR‐152 controls migration and invasive potential by targeting TGF alpha in prostate cancer cell lines. Prostate. 2013;73:1082‐1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rubinstein E. The complexity of tetraspanins. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:501‐505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lau MT, So WK, Leung PC. Fibroblast growth factor 2 induces E‐cadherin down‐regulation via PI3K/Akt/mTOR and MAPK/ERK signaling in ovarian cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e59083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang J, Ni Z, Duan Z, Wang G, Li F. Altered expression of hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1alpha (HIF‐1alpha) and its regulatory genes in gastric cancer tissues. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e99835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen L, Shi Y, Yuan J, et al. HIF‐1 alpha overexpression correlates with poor overall survival and disease‐free survival in gastric cancer patients post‐gastrectomy. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e90678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Semenza GL. HIF‐1 and tumor progression: pathophysiology and therapeutics. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:S62‐S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:104‐117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Altobelli E, Lattanzi A, Paduano R, Varassi G, di Orio F. Colorectal cancer prevention in Europe: burden of disease and status of screening programs. Prev Med. 2014;62:132‐141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Guo K, Yao J, Yu Q, et al. The expression pattern of long non‐coding RNA PVT1 in tumor tissues and in extracellular vesicles of colorectal cancer correlates with cancer progression. Tumour Biol. 2017;39 10.1177/1010428317699122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Takahashi Y, Sawada G, Kurashige J, et al. Amplification of PVT‐1 is involved in poor prognosis via apoptosis inhibition in colorectal cancers. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:164‐171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Budhu A, Forgues M, Ye QH, et al. Prediction of venous metastases, recurrence, and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma based on a unique immune response signature of the liver microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:99‐111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Attwa MH, El‐Etreby SA. Guide for diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:1632‐1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yu F, Lu Z, Chen B, Wu X, Dong P, Zheng J. Salvianolic acid B‐induced microRNA‐152 inhibits liver fibrosis by attenuating DNMT1‐mediated Patched1 methylation. J Cell Mol Med. 2015;19:2617‐2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zheng J, Yu F, Dong P, et al. Long non‐coding RNA PVT1 activates hepatic stellate cells through competitively binding microRNA‐152. Oncotarget. 2016;7:62886‐62897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yu J, Han J, Zhang J, et al. The long noncoding RNAs PVT1 and uc002mbe.2 in sera provide a new supplementary method for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis. Medicine. 2016;95:e4436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang F, Yuan JH, Wang SB, et al. Oncofetal long noncoding RNA PVT1 promotes proliferation and stem cell‐like property of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by stabilizing NOP2. Hepatology. 2014;60:1278‐1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sharma C, Eltawil KM, Renfrew PD, Walsh MJ, Molinari M. Advances in diagnosis, treatment and palliation of pancreatic carcinoma: 1990‐2010. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:867‐897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Crawley AS, O'Kennedy RJ. The need for effective pancreatic cancer detection and management: a biomarker‐based strategy. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2015;15:1339‐1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wolfgang CL, Herman JM, Laheru DA, et al. Recent progress in pancreatic cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:318‐348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wongkham S, Silsirivanit A. State of serum markers for detection of cholangiocarcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(suppl):17‐27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Malaguarnera G, Paladina I, Giordano M, Malaguarnera M, Bertino G, Berretta M. Serum markers of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Dis Markers. 2013;34:219‐228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Liang B, Zhong L, He Q, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of serum CA19‐9 in patients with cholangiocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:3555‐3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wu BQ, Jiang Y, Zhu F, Sun DL, He XZ. Long noncoding RNA PVT1 promotes EMT and cell proliferation and migration through downregulating p21 in pancreatic cancer cells. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2017. 10.1177/1533034617700559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Xie Z, Chen X, Li J, et al. Salivary HOTAIR and PVT1 as novel biomarkers for early pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:25408‐25419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Huang C, Yu W, Wang Q, et al. Increased expression of the lncRNA PVT1 is associated with poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer patients. Minerva Med. 2015;106:143‐149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]