Abstract

During retinal development, ribbon synapse assembly in the photoreceptors is a crucial step involving numerous molecules. While the developmental sequence of plexiform layers in human retina has been characterized, the molecular steps of synaptogenesis remain largely unknown. In the present study, we focused on the central rod-free region of primate retina, the fovea, to specifically investigate the development of cone photoreceptor ribbon synapses. Immunocytochemistry and electron microscopy were utilized to track the expression of photoreceptor transduction proteins and ribbon and synaptic markers in fetal human and Macaca retina. Although the inner plexiform layer appears earlier than the outer plexiform layer, synaptic proteins, and ribbons are first reliably recognized in cone pedicles. Markers first appear at fetal week 9. Both short (S) and medium/long (M/L) wavelength-selective cones express synaptic markers in the same temporal sequence; this is independent of opsin expression which takes place in S cones a month before M/L cones. The majority of ribbon markers, presynaptic vesicular release and postsynaptic neurotransduction-related machinery is present in both plexiform layers by fetal week 13. By contrast, two crucial components for cone to bipolar cell glutamatergic transmission, the metabotropic glutamate receptor 6 and voltage-dependent calcium channel α1.4, are not detected until fetal week 22 when bipolar cell invagination is present in the cone pedicle. These results suggest an intrinsically programmed but nonsynchronous expression of molecules in cone synaptic development. Moreover, functional ribbon synapses and active neurotransmission at foveal cone pedicles are possibly present as early as mid-gestation in human retina.

Keywords: electron microscopy, immunocytochemistry, Macaca, retina, RRID: AB_1860018, RRID: AB_2314216, RRID: AB_399431, RRID: AB_94671, RRID: AB_2631101, RRID: AB_2279325, RRID: AB_94284, RRID: AB_2314780, RRID: AB_2314792, RRID: AB_10000343, RRID: AB_2092368, RRID: AB_10746416, RRID: AB_2253622, RRID: AB_2315298, RRID: AB_2315389/91, RRID: AB_477523, RRID: AB_887877, RRID: AB_2631102

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

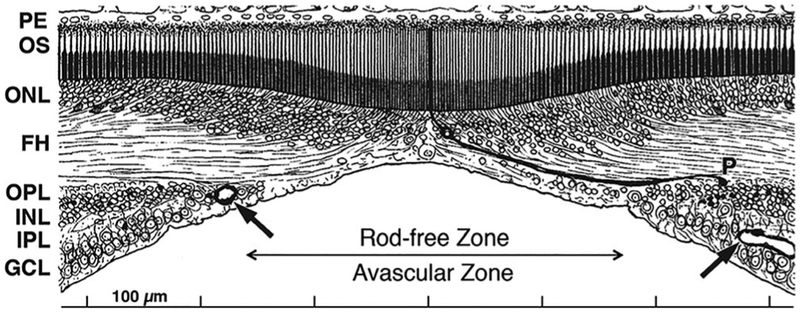

In adult monkeys, apes and humans, the central retina contains a specialized region called the fovea (Figure 1). This region is characterized by a pit in which the inner retinal layers are displaced peripherally. Over the pit center, cone photoreceptor density is the highest in the retina, reaching over 200,000 cones/mm2 (Curcio, Sloan, Kalina, & Hendrickson, 1990). Individual cones are very long and thin; a single foveal cone is highlighted in Figure 1. By contrast, rod photoreceptors are absent from the central 300 μm, which is called the rod-free zone. Blood vessels are also absent from the central fovea, forming a ring around this region, formally known as the foveal avascular zone.

FIGURE 1.

A drawing of the human adult fovea, modified by AH from Polyak (1941). The rod-free zone and foveal avascular zone are roughly coextensive. The most central capillaries are indicated by arrows. The pit displaces the inner nuclear (INL), inner plexiform (IPL), and ganglion cell (GCL) layers laterally. Over the pit center, cone density is the highest in the retina. One of the long thin foveal cones is emphasized to show its outer segment (OS), nucleus in the outer nuclear layer (ONL), cone axon, or fiber of Henle (FH) and synaptic pedicle (P) displaced from its cell body in the outer plexiform layer (OPL)

Foveal development has been shown to be a complex process. Previous work finds that the human fovea is morphologically apparent at fetal week (Fwk) 11 (Linberg & Fisher, 1990), but then develops slowly through the remainder of gestation (Hendrickson & Yuodelis, 1984). The pit begins after midgestation (Fwk 20) but is not mature until several months after birth (Hendrickson, Possin, Vajzovic, & Toth, 2012; Vajzovic et al., 2012). Surprisingly, in both human and monkey fovea, cone density is only ~25,000/mm2 at birth which is little different from midgestation (Diaz-Araya & Provis, 1992; Packer, Hendrickson, & Curcio, 1990; Springer, Troilo, Possin, & Hendrickson, 2011; Yuodelis & Hendrickson, 1986). Cone density rises after birth, probably due to a combination of cellular remodeling and a packing mechanism (Hendrickson & Kupfer, 1976; Provis, Dubis, Maddess, & Carroll, 2013; Springer, 1999; Yuodelis & Hendrickson, 1986) because there is no evidence for late generation of cones (Hendrickson, Possin, Kwan, Huang, & Bourne, 2016; La Vail, Rapaport, & Rakic, 1991). It takes 4–6 years for an adult density of ~200,000/mm2 to be reached in humans (Yuodelis & Hendrickson, 1986) and up to 15 months in macaque (Packer et al., 1990).

How does this morphological maturation compare with the appearance of synapses? One advantage of the slow retinal development in primates is that small increments of change can be detected more easily. Earlier studies from this lab in macaque and marmoset monkeys have shown that the earliest expression of synaptic labels is in the fovea (Hendrickson, Troilo, Djajadi, Possin, & Springer, 2009; Sears, Erickson, & Hendrickson, 2000) which begins shortly after cones are generated (Hendrickson et al., 2016; La Vail et al., 1991). Foveal synaptic development at the electron microscopic (EM) level in humans has not been reported, but that of the macaque inner plexiform layer (IPL) has (Crooks, Okada, & Hendrickson, 1995). Ribbon-containing synapses of bipolar cells are sparse but present at fetal day (Fd) 55 (term=Fd 170). Conventional synapses of amacrine cells appear by Fd 68, and these increase dramatically by Fd 88, shortly after midgestation. Thus in monkeys synaptic proteins and markers appear very early in both foveal IPL and outer plexiform layer (OPL).

We have examined a series of human prenatal foveas starting at Fwk 8 to track the immunocytochemical expression of pre- and post-synaptic markers in the cones and inner retina. We find that most markers appear between Fwk 8 and Fwk 13, except the ON bipolar metabotropic glutamate receptor 6 (mGluR6) and the voltage-gated calcium channel α1.4 (VCa) which appear together at Fwk 22. This indicates that inner and outer retina are synaptically linked well before the onset of either pit formation or cone packing.

2 ∣. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 ∣. Antibody characterization

The monoclonal antibody (mab) against the bassoon protein (Abcam Cat# ab82958, RRID:AB_1860018) detected a 400 kilodalton (kDa) band in a Western blot of mouse and rat brain (manufacturer data sheet). Bassoon is an established marker for photoreceptor ribbons, and no immunostaining is detected in bassoon knockout retinas (Brandstatter, Fletcher, Garner, Gundelfinger, & Wassle, 1999; Dick et al., 2003).

The mouse mab against the alpha subunit of cone transducin (J. B. Hurley, University of Washington, Seattle WA USA Cat# cone transducin (A1.1), RRID:AB_2314216) recognizes a 40.5-kDa band in Western blots of human retina extracts. It immunolabels the outer segments and cytoplasm, including the synapse of primate cones (Lerea, Bunt-Milam, & Hurley, 1989).

The mab against C-terminal binding protein 2 (BD Biosciences Cat# 612044, RRID:AB_399431) recognizes a 48-kDa protein in Western blots of rat retina (manufacturer data sheet). It was previously shown to label ribbons in photoreceptor and bipolar cell synaptic terminals in macaque and marmoset retina (tom Dieck et al., 2005; Jusuf, Martin, & Grunert, 2006).

The mouse mab against the G protein Goα (Millipore Cat# MAB3073, RRID:AB_94671) reacted with a protein of 42–43 kDa in homogenates from X. laevis and B. japonicas olfactory epithelium (Hagino-Yamagishi & Nakazawa, 2011). In retina, it labels rod and cone ON-bipolar cells (Dhingra et al., 2000; Haverkamp & Wassle, 2000).

The rabbit antibody to interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (G. Chader NIH/NEI Cat# anti-IRBP affinity purity antibody, RRID: AB_2631101) was shown by immunoblotting of extracts from human, bovine, and macaque eyes to label a single band in the 116-200 kDa range for each species. The antibody selectively labeled rod photoreceptor cells of the primate retina and gave little or no staining of cone photoreceptors or Müller glia (Rodrigues et al., 1986; Wiggert et al., 1986).

The antibody to ionotropic glutamate receptor 2/3 (Abcam Cat# ab27225, RRID:AB_2279325) was shown to specifically react with a band between 102 and 76 kDa in extracts of pigeon brain. This corresponds to the predicted 98 kDa for the common epitope of subunits 2 and 3 of the α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors (Cabral, Santana, da Silva, & de Toledo, 2010). According to the manufacturer data sheet, it also specifically labels the corresponding human AMPA receptors.

The mab to kinesin (Millipore Cat# MAB1614, RRID:AB_94284) has been shown to react only with the heavy chain, not with the light chain, and was found to immunolabel punctate cytoplasmic structures, but not microtubules in a variety of human cell lines (Pfister, Wagner, Stenoien, Brady, & Bloom, 1989). The H2 clone was shown to react with all three isoforms of kinesin (Kif5A, Kif5B, and Kif5C) in retinal extracts (Cai, Singh, Aslanukov, Zhao, & Ferreira, 2001).

The antibody against medium- and long-wavelength-sensitive cone opsin (J. C. Saari, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA Cat# medium- and long-wavelength-selective cone opsin, RRID: AB_2314780) recognizes a 38-kDa band in Western blots of human retina (Saari, unpublished observations). It shows high specificity for M/L opsin in both fetal and adult retina and has been used previously to study human and macaque cone development (Bumsted, Jasoni, Szel, & Hendrickson, 1997; Lerea et al., 1989; Xiao & Hendrickson, 2000).

The metabotropic glutamate receptor 6 (N. Vardi, University of Pennsylvania; Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA Cat# mGluR6, RRID: AB_2314792) antibody recognized a single band of 190 kDa in Western blots of monkey retina (Vardi, Duvoisin, Wu, & Sterling, 2000). It reproduced the pattern of labeling described previously in macaque retina; it labeled the tips of macaque ON bipolar cell dendrites (Gastinger, Barber, Vardi, & Marshak, 2006).

The parvalbumin monoclonal antibody (U.S. Biological Cat# P4700-07, RRID:AB_2092368) recognized a single band of 12 kDa on Western blots of rat brain (Celio, Baier, Scharer, de Viragh, & Gerday, 1988). It reproduced the pattern of labeling described previously using calretinin antibodies in macaque retina; it labels macaque horizontal cells and a type of broadly stratified amacrine cell (Klump, Zhang, Wu, & Marshak, 2009).

The antibody to postsynaptic density protein 95 (U.S. Biological Cat# P4700-07, RRID:AB_2092368) was characterized via Western blot using rat brain extracts. In our hands, it gives the characterstic labeling of photoreceptor terminals in adult retina as has been described for other similar PSD95 antibodies (Puthussery et al., 2014).

The antibody to protein kinase C alpha (Sigma-Aldrich Cat# SAB4502354, RRID:AB_10746416) used here was previously shown to label human and macaque monkey rod bipolar cells (Haverkamp, Haeseleer, & Hendrickson, 2003).

The pab against recoverin (Millipore Cat# AB5585, RRID: AB_2253622) recognizes a 25-kDa protein on Western blots of mouse retina. In primate retina, it labels only photoreceptors and midget bipolar cells (Haverkamp et al., 2003; Milam, Dacey, & Dizhoor, 1993).

The rabbit polyclonal antibody (pab) to S-cone opsin (J. Nathans, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA Cat# S-cone opsin RRID:AB_2315298) (Wang et al., 1992) immunolabels S cones in both fetal and adult primate retina. The antibody has been used to characterize S-opsin expression during retinal development (Bumsted & Hendrickson, 1999; Martin & Grünert, 1999; Xiao & Hendrickson, 2000).

The mouse mab to synaptic vesicle 2 (K. Buckley and R. B. Kelly, University of California at San Francisco, CA, USA Cat# SV2 (synaptic vesicle 2), RRIDs:AB_2315389, AB_2315391) recognizes a 78-kDa transmembrane glycoprotein in synaptic vesicles of neurons and endocrine cells (Buckley & Kelly, 1985), and recognizes isoforms A, B, and C (Bajjalieh, 1999). It was used to demonstrate localization of SV2 to synaptic vesicles of both conventional and ribbon synapses in macaque retina (Okada, Erickson, & Hendrickson, 1994).

The mab to synaptophysin (Sigma-Aldrich Cat# S5768, RRID: AB_477523) detects a 38-kDa protein on Western blots of rat brain and labels neurons, neuromuscular junctions, paracrine cells, and neuronal tumors of all mammalian species (manufacturer datasheet). At the electron microcroscopy (EM) level, this antibody labels photoreceptor and bipolar cell synaptic terminals in primate retina (Koontz & Hendrickson, 1993).

The rabbit pab against the vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (Synaptic Systems Cat# 135 302, RRID:AB_887877) recognizes a 60-kDa protein in Western blots of rat brain. It localizes to retinal photoreceptor and bipolar cell ribbon-containing synaptic terminals (Mimura et al., 2002; Sherry, Wang, Bates, & Frishman, 2003).

The rabbit antibody against the voltage gated calcium channel α1.4 (anti-Cacna1f(Pep3); Marion Maw* distributed by Dr. tom Dieck, University of Otago, Dunedin, NZ Cat# anti-Cacna1f(Pep3); RRID: AB_2631102) was previously shown to exhibit presynaptic active zone staining in mouse photoreceptor ribbon synapses (Specht et al., 2009). It showed greatly reduced labeling in mice with a mutant Cacna1f gene.

2.2 ∣. Tissue processing

All human tissue was obtained under approved Human Subjects protocols (E01-0447) with the assistance of the University of Washington (UW) Human Tissue Program, the UW Lions Eye Bank, or ABR, Inc. (San Mateo CA). Human eyes in this study ranged from Fwk 7 to Fwk 24. Macaca fascicularis monkey fetal and infant eyes were obtained at the Indonesian Primate Center, Bogor, Java under approved UW Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols. Monkey eyes ranged from Fd 50 to Fd 165, and postnatal 1,3, 6, and 12 weeks.

For immunolabeling, enucleated human and monkey eyes were immersion fixed for 1–2 hr in 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4. The cornea and lens were removed before fixation of eyes older than Fwk 15. The horizontal meridian was cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PB, frozen in OCT and serially sectioned at 12 μm. Every tenth slide was stained with 1% azure II/methylene blue in pH 10.5 borax buffer to locate the fovea and optic nerve head. Data reported in this study were taken from sections in or on the edge of the fovea. One enucleated monkey eye was fixed and processed as above. The fovea from the other eye was prepared for electron microscopy. It was immersion fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% glutaraldehyde in PB, then processed through 1% osmium tetroxide, rinsed, en bloc stained in 1% uranyl acetate, dehydrated in ethanol solutions, and embedded in epoxy resin (Epon Araldite). Thin sections were cut, placed on Formvar-coated slot grids and stained with Reynolds lead citrate.

To compare events in human (birth = Fwk 40) and monkey (birth = Fd 170) retinal development, percent gestation was used as a correction factor (e.g., 50% gestation is Fwk 20 in humans or Fd 85 in monkeys; see Table 2 for monkey–human developmental correlations). Using this correction, seminal events in human and macaque retinal development correspond closely throughout most of gestation (Hendrickson 1992; Hendrickson & Provis, 2006; Provis et al., 2013).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of significant retinal developmental events between Macaca and human

| Developmental event |

Macaca |

Human |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal days | % Gestation | Fetal weeks | % Gestation | |

| First ganglion and horizontal cells born | 30 | 18 | 7 | 18 |

| First cones born | 35 | 20 | 8 | 20 |

| First rods born | 43 | 25 | 10 | 25 |

| Foveal mitosis over; fovea appears | 50 | 29 | 11 | 28 |

| Cone synaptic proteins first appear | 60 | 35 | 10 | 25 |

| S opsin expressed | 65 | 38 | 12 | 30 |

| L&M opsin expressed | 65 | 38 | 15 | 40 |

| Rhodopsin expressed | 65 | 38 | 15 | 40 |

| Retinal vessels at optic disc | 70 | 41 | 16 | 40 |

| Peak ganglion cell axon number | 80 | 47 | 17 | 43 |

| Midgestation | 85 | 50 | 20 | 50 |

| Foveal avascular zone forms | 105 | 62 | 26 | 65 |

| Foveal pit begins | 105 | 62 | 26 | 65 |

| Eyelids open | 130 | 77 | 28 | 70 |

| OPL, IPL to edge retina | 30 | 76 | ||

| Birth | 170 | 100 | 40 | 100 |

| Adult foveal cone density | 722 | 425 | 248 | 620 |

The bold values denote key developmental stages (Midgestation and Birth)

2.3 ∣. Immunocytochemistry

Frozen sections were blocked for 1 hr in 10% Chemiblocker (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) in PB containing 0.5% Triton X100. They were incubated overnight in a single antiserum or a mixture of two antisera from different species in PB containing 5% Chemiblocker and 0.5% Triton X100 (diluent). Primary antisera are listed in Table 1. After a 2-hr wash in PB, sections were incubated for 1 hr in the dark in the appropriate species Alexafluor 488 or 594 (1/400; Molecular Probes, Eugene OR), washed, and coverslipped.

TABLE 1.

Antibodies used

| Antibody | Immunogen | Source | RRID raised in, type | Working dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibassoon | Recombinant rat bassoon | Abcam, Cambridge, MAcatalog # ab82958 | AB_1860018 mouse, mab | 1:2,500 |

| Anticone transducin | a.a. 159–170 of human cone transducin alpha subunit | J. Hurley, University of Washington, Seattle, WA | AB_2314216 UNK host, clon | 1:2,50 |

| Anti-C-terminal binding protein 2 | a.a. 361–445 of mouse C-terminal binding protein 2 | BD Bioscience, Heidelberg, Germany, catalog # 612044 | AB_399431 mouse, mab | 1:8,000 |

| Anti-G protein Go alpha, clone 2A | Purified bovine brain Goα | EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, catalog # MAB3073 | AB_94671 mouse, mab | 1:4,000 |

| Antiinterphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein | Purified Macaca mullatta interphotoreceptor retinoid binding protein | G. Chader NIH/NEI, Bethesda, MD | AB_2631101 rabbit, pab | 1:2,000 |

| Antiionotropic glutamate receptors 2 + 3 | Synthetic peptide from C terminus of human GluR2/3 | Abcam, Cambridge, MAcatalog # ab27225 | AB_2279325 rabbit, pab | 1:500 |

| Kinesin clone H2 | Kinesin heavy chain, a.a. 420-445 | EMD Millipore, Billerica, MAcatalog # MAB1614 | AB_94284 mouse, mab | 1:50 |

| Antimedium/long wavelength sensitive cone opsin | C-terminal 18 a.a. of human L/M opsin | J. Saari, University of Washington, Seattle, WA | AB_2314780 rabbit, pab | 1:5,000 |

| Antimetabotropic glutamate receptor 6 | C-terminal peptide of human mGluR6 (KATSTVAAPPKGEDAEAHK) | N. Vardi, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA | AB_2314792 rabbit, pab | 1:500 |

| Antiparvalbumin | PV purified from carp muscles | Swant, Marly, Switzerlandcatalog # PV325 | AB_10000343 mouse, mab | 1:5,000 |

| Antipostsynaptic density protein 95 | Rat Disks Large 4 homolog (Dlg4) | U.S. Biological, Salem, MAcatalog # P4700-07 | AB_2092368 rabbit, pab | 1:2,000 |

| Antiprotein kinase Cα | Synthetic peptide from human PKCα | Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO catalog # SAB4502354 | AB_10746416 rabbit, pab | 1:1,000 |

| Antirecoverin | Recombinant human recoverin | EMD Millipore, Billerica, MAcatalog # AB5585 | AB_2253622 rabbit, pab | 1:20,000 |

| Antishortwavelength opsin | C-terminal 48 a.a. human S opsin | J. Nathans, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore MD | AB_2315298 rabbit, pab | 1:15,000 |

| Antisynaptic vesicle 2 | Torpedo synaptic vesicles | K. Buckley, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA | AB_2315389/91 mouse, mab | 1:1000 |

| Antisynaptophysin | Rat retina synaptosomes | Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO catalog # S5768 | AB_477523 mouse, mab | 1:1000 |

| Antivesicular glutamate transporter 1 | a.a. 456-560 of rat vesicular glutamate transporter 1 | Synaptic Systems, Gottingen, Germany catalog # 135302 | AB_887877 rabbit, pab | 1:10,000 |

| Antivoltage gated calcium channel α1.4 | Cacna1f synthetic peptide AEEGRAGHRPQLSELTN | M. Maw, University of Otago, Dunedin, NZ | AB_2631102 rabbit, UNK clon | 1:200 |

2.4 ∣. Image acquisition

Immunolabled sections were imaged as single or through focus images on a Nikon Eclipse E1000 widefield microscope using a Hamamatsu camera and a Z-axis stepping stage. Images were deconvolved using Huygens software (Scientific Volumn Imaging, Hilversum, The Netherlands). Electron microscopic images were taken with a JEOL 100S transmission electron microscope, prints were made at a final magnification of 25,000×, these were formed into large montages of the outer retina, and selected areas were scanned digitally (see Crooks et al., 1995 for details). All images were imported into Photoshop CS5 (Adobe, San Jose, CA) and processed for size, color balance, sharpness, and contrast.

3 ∣. RESULTS

3.1 ∣. General morphology

The human eye develops over a long timespan and has a prominent centro-peripheral gradient throughout much of gestation (Hendrickson, 1992, 2016). This article will concentrate on the expression of synaptic markers in the fovea which is the first retinal area to mature, but the last to complete development. Human foveal development has been reported in several papers which show that the fovea appears morphologically at Fwk 11 and pit formation begins at Fwk 20 (reviewed in Provis et al., 2013). Cone packing to raise foveal density is mainly a postnatal event (Yuodelis & Hendrickson, 1986), so the prenatal period covered by this study will not be influenced by cone packing or pit formation. The morphological progression of the IPL and OPL has been reported for human retina (Hendrickson, 2016). There is considerable difference between inner and outer retina in that the IPL and ganglion cell layer (GCL) are to the edge of the retina just before midgestation, while the OPL is not complete until Fwk 30.

Because it is very difficult to obtain human eyes after Fwk 20, we include data from a timed series of Macaca fascicularis fetuses and infants which provide information about later gestational changes. Human and monkey prenatal retinal development are closely parallel when compared using percent (%) gestation (see Table 2).

3.2 ∣. Human foveal development between Fwk 8 and 10

At Fwk 8 the entire retina is only 3,800 μm long. In azure II/methylene blue stained sections, the region that will become the fovea can be identified as a zone 300 μm wide just temporal to the optic nerve (Figure 2a). This presumptive foveal zone is characterized by a thin, relatively acellular gap between the thick, pale, inner neuroblastic layer and the thick, basophilic outer neuroblastic layer. This gap marks the onset of IPL development which at Fwk 8–9 is confined to the presumptive fovea (for more details regarding development of the human IPL and OPL, please see Hendrickson, 2016). A thin nerve fiber layer is present on the temporal side of the optic nerve, indicating that ganglion cells (GC) are present and their axons are growing centrally. In outer retina, adjacent to the pigment epithelium (PE), some large round cells are present, presumably cones, but many other types of cells including mitotic figures are intermixed at this age.

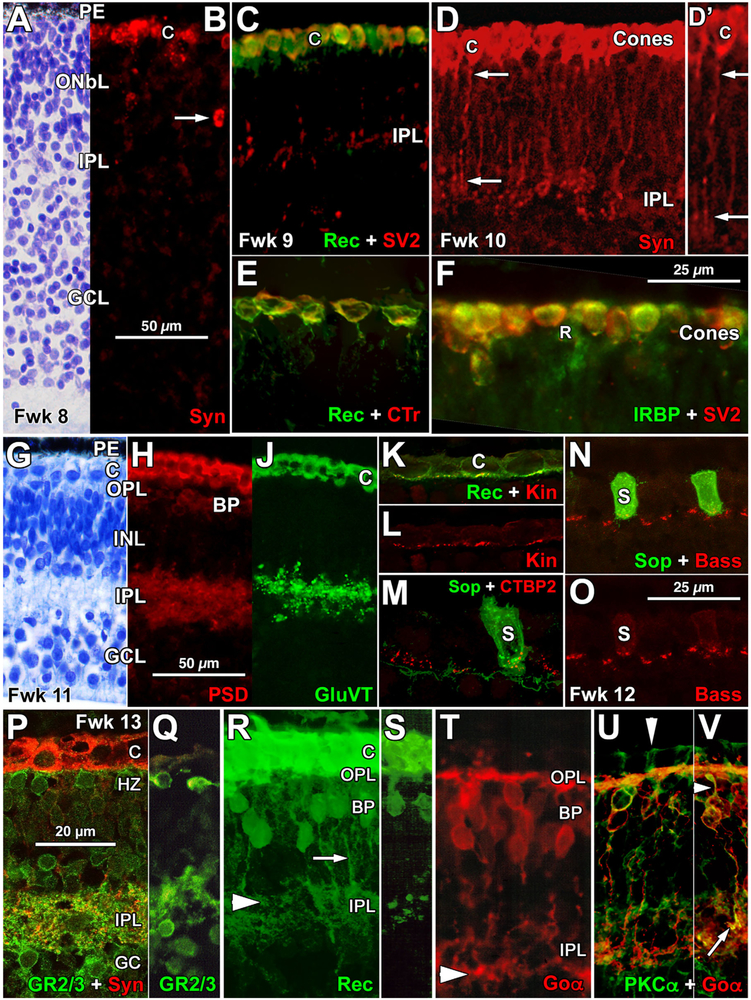

FIGURE 2.

Human Foveal Development Fetal Weeks 8–13. (a) Fwk 8 incipient fovea stained with 1% azure II/methylene blue (also see Figure 3 in Hendrickson, 2016 for a wider view of histology). The outer retina tightly adheres to the pigment epithelium (PE). The putative cones are found in a thick outer neuroblastic layer (ONbL). This is separated by a less cellular IPL and a thick dense GCL. Scale in b for a–c. (b) Adjacent Fwk 8 section labeled for synaptophysin (Syn) showing a row of large round Syn + immature cones (C) at the outer edge of the retina. The arrow shows a deeper Syn + cell. (c) All Fwk 9 cones (C) are both recoverin + (Rec) and synaptic vesicle 2 + (SV2). SV2 + puncta and vertical processes are present in the IPL. (d, d′) Fwk 10 Syn + foveal cones with numerous vertical processes (arrows) ending in puncta within the IPL. d′ is an enlargement of the cone marked “C.” Scale in f for d–f. (e). Fwk 10 cone cytoplasm is both recoverin + (Rec) and cone transducin + (CTr). (f) Fwk 10 cone cytoplasm is heavily double-labeled for SV2 and interphotoreceptor retinoid binding protein (IRBP). (g) Fwk 11 cresyl violet stained fovea showing five layers. The cones (C) now are separated from the INL by a thin OPL. The IPL is acellular and the GCL is packed with basophilic neurons. Scale in h for g–j. (h,j) Adjacent Fwk 11 sections labeled with postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD; h) and glutamate vesicular transporter 1 (GluVT; j). Cone cytoplasm is heavily labeled for both. The IPL is labeled for PSD throughout its depth, but GluVT is concentrated in the outer IPL. Presumed bipolar cell (BP) bodies are PSD +, but few neurons are GluVT + except cones. (k, l) Cones (C) marked with Rec in K contain a basal row of kinesin + (Kin; l) ribbons. k Shows Rec and Kin labels, I shows only Kin. Scale in o for k–o. (m) Cones around the fovea label for S cone opsin (Sop) by Fwk 11–12. Both the S cone and the surrounding opsin negative cones have c-terminal binding protein 2 + (CTBP2) synaptic ribbons at their base. (n, o) Both S cones (S) and neighboring opsin negative cones have basal ribbons labeled for bassoon (Bass). (p,q) The Fwk 13 fovea has heavy labeling for glutamate receptor 2/3 (GR2/3) at the base of the Syn + cones (C). Underlying horizontal cell bodies (HZ) and cell bodies on both sides of the IPL are GR2/3+. The IPL has GR2/3 + (green) and GR2/3+/Syn + (yellow) processes and puncta. Scale in p for p–v. (r–v) Adjacent Fwk 13 sections aligned to show bipolar cell (BP) labeling. R-S: BP cell bodies and outer IPL processes are Rec+. Cell bodies have basal axons (arrow) which end in the outer half of the IPL (arrowhead). (t) BP cell bodies, processes in the OPL and BP axons contain G protein Go alpha (Goα). Goα + axon terminals concentrate in the inner IPL (arrowhead). (u,v) Double labeling for Goα and protein kinase C alpha + (PKCα) show that some BP cells are positive for both. The arrow points to a Goα+/PCKα + BP axon terminal in the IPL and the arrowhead indicates a double-labeled dendrite from the same BP

Despite this immature morphology, the beginning of synaptic marker expression was found at Fwk 8–10, but only in the presumptive foveal region. Immunolabeled (+) cones with a variety of markers were numerous and form a single layer (Figure 2b–f). The cytoplasm but not the nucleus of large cells lining the outer retinal edge was synaptophysin + (Syn; Figure 2b,c) with a few deeper Syn + cells (Figure 2b, arrow). The latter disappear by Fwk 11. Other markers expressed in cones at Fwk 9–10 include synaptic vesicle 2 (SV2; Figure 2c), recoverin (Rec; Figure 2e), cone transducin (CTr; Figure 2e), and interphotoreceptor retinoid binding protein (IRBP; Figure 2f). Electron microscopic immunolabeling (Okada et al., 1994) shows that SV2 labels photoreceptor pedicle cytoplasm around vesicles and both ribbon and conventional synapses in the IPL. Cones at the outer retinal border had fine labeled processes descending to the IPL and ending in SV2 + (Figure 2c) or Syn + (Figure 2d,2d′, arrows) puncta. Although cone cell bodies were Rec + and IRBP + (Figure 2e,f), the IPL puncta were negative for these markers. Despite its early morphological appearance (also see Hendrickson, 2016), the Fwk 9–10 foveal IPL contained only sparse SV2 + and Syn + puncta (Figure 2c,d), with inner nuclear layer (INL) neurons and GC bodies unlabeled by these synaptic markers. A morphological OPL did not become clear until Fwk 11 in azure II/methylene blue stained sections despite the early cone immunolabeling (Figure 2g).

3.3 ∣. Human foveal development between Fwk 11 and 13

At Fwk 11, the fovea is ~1 mm wide and is the only region within the entire retina that has five layers (Figure 2g). The IPL is wider and free of cells while the GCL is tightly packed and quite thick. The neurons in the INL have matured so that outer horizontal, middle bipolar, and inner amacrine sublayers are emerging. The thin outer nuclear layer (ONL) of the central 1mm is formed by a single layer of large, pale-staining cones (C) containing a large dense nucleus (Figure 2g). This is the distinctive “pure cone” region that will characterize the fovea throughout the remainder of its development (Hendrickson & Kupfer, 1976; Hendrickson & Yuodelis, 1984). Cones are separated from the INL by a thin fibrous OPL Thus, at Fwk 11, the five-layered fovea (area = 1.77 mm2) sits as a differentiated island which is less than 2% of the much larger (area = 74 mm2), but very immature, more peripheral retina.

The morphological emergence of the fovea is accompanied by a burst of neuronal marker expression in both outer and inner retina. Between Fwk 11 and Fwk 13 all cones across the fovea and on its edge express the synapse proteins postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD; Figure 2h) and vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (GluVT; Figure 2j). These markers also are now present as fibers and puncta in the IPL, but neuronal labeling is still sparse. PSD was found through the full thickness of the IPL while GluVT + puncta were heavier in the outer half. The synaptic ribbon markers kinesin (Kin; Figure 21), cone transducin (CTr, data not shown), c-terminal binding protein 2 (CTBP2; Figure 2m) and bassoon (Bass; Figure 2n,o) were also present in the base of the central cones, including ones that expressed S-cone opsin (Sop; Figure 2m,n).

On the inner side of the thin foveal OPL, horizontal cell bodies and processes labeled for ionotropic glutamate receptor 2/3 (GR2/3; Figure 2p,q). In the inner retina, GR2/3 + bipolar, amacrine, and ganglion cell bodies are present, and the IPL contains many GR2/3 + puncta throughout its thickness. A subset of bipolar axonal and dendritic processes and cell bodies contained the OFF bipolar cell marker Rec (Figure 2r,s). Other bipolar cells labeled for the ON bipolar cell markers G protein Go alpha (Goα; Figure 2t,v) and protein kinase C alpha (PKCα; Figure 2u). There is a suggestion of IPL stratification with Rec + putative OFF axons terminating in the outer half (Figure 2r, white arrowhead) while Goα + and PKCα + putative ON axons terminating in the inner half (Figure 2t, white arrowhead). In addition, all three groups of bipolar cells have labeled dendrites extending to the OPL. Thus, by Fwk 13, many adult presynaptic and postsynaptic proteins are present within the fovea in both the IPL and OPL.

Synaptic differentiation is confined to cones at Fwk 11–13, because cells on the foveal edge containing the rod-specific nuclear protein NRL (Neural Retina Leucine Zipper) do not double-label for any synaptic markers (see Hendrickson et al., 2008).

3.4 ∣. Human foveal development between Fwk 14 and 18

From Fwk 14 to 18, foveal neurons mature, especially the cones which elongate and develop inner segments and synaptic pedicles (Figure 3a). The cone pedicle becomes smaller and more defined with age, especially as the cone axon develops (compare Figure 3c [foveal center, more mature cones] to Figure 3d [foveal edge, less mature cones]). The elongated cones now show cytoplasmic localization of markers. In contrast to younger cones where the entire cytoplasm is labeled, IRBP is confined to granules within the inner segment (IS) (Figure 3b). By Fwk 16, IRBP cellular labeling in the fovea disappears as the interphotoreceptor space between the emerging outer segment and pigment epithelium becomes heavily IRBP + (not shown). CTr (Figure 3c) labels both inner segment and cone pedicles, a pattern which it will retain into adulthood. GR2/3 + processes (Figure 3c) cluster beneath each cone pedicle.

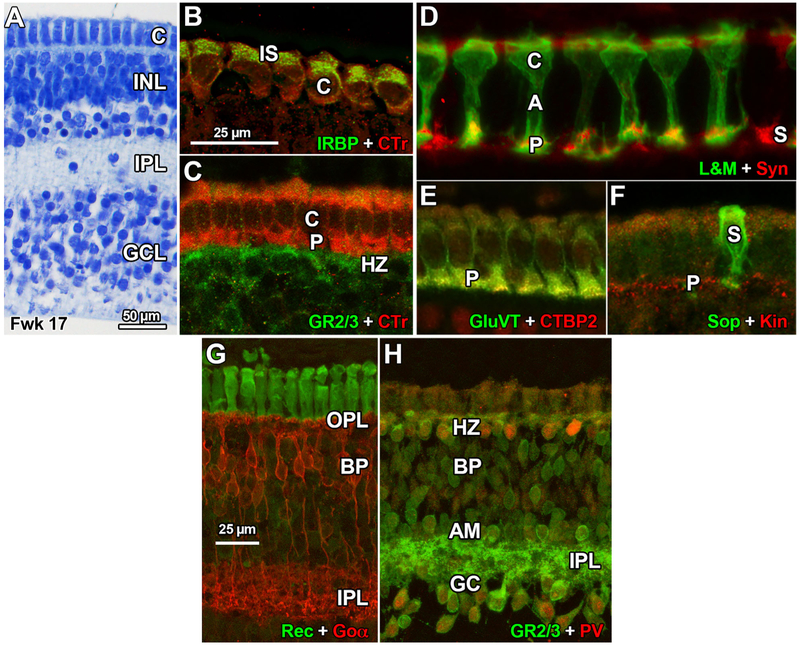

FIGURE 3.

Human Foveal Development Fwk 17–18. (A) Fwk 17 fovea stained with 1% azure II/methylene blue. The cones (C) are more elongated compared to earlier ages. (b) IRBP is confined to the developing inner segment (IS) of the Fwk 17 cones (C) while CTr is distributed throughout the cytoplasm. Compare this to IRBP label at Fwk 10 (Figure 2f). Scale in b for b–f. (c) The heavily labeled CTr + cone (C) cytoplasm shows the change in cell shape by Fwk 17–18. Each cone pedicle (P) is contacted by GR2/3 + horizontal cell (HZ) processes. (d) By Fwk 17–18 cones on the foveal edge (outside the rod-free zone) have expressed long & medium wavelength selective cone opsin (L&M). Because the cone membrane is L&M +, the entire cell is outlined. Cone axons (A) have elongated to accommodate the insertion of unlabeled rod cell bodies. Cone pedicles (P) label heavily for Syn but the rest of the cone has little Syn. S cones (S) also have basal Syn labeling. (e) All cone pedicles (P) contain GluVT while synaptic ribbons are CTBP2+. (f). Both S (S) cone pedicles and unlabeled L&M pedicles (P) contain kinesin + (Kin) ribbons. (g). The ON bipolar cells (BP) labeled with Goα have axon terminals concentrated in the inner IPL and processes filling the OPL. (h). Horizontal cells (HZ) are double labeled for parvalbumen (PV) and GR2/3. The inner retina is heavily labeled for GR2/3 including the entire IPL as well as bipolar (BP), amacrine cells (AM), displaced AM, small PV + ganglion cells (GC), and other GC

The first cone opsin appears at Fwk 11 (Xiao & Hendrickson, 2000) with scattered cones around the foveal edge expressing short wavelength-selective cone opsin (Sop); Figure 2m,n). When S cones are first detected, their cytoplasm is SV2 + or Syn + and their base contains synaptic ribbon markers (Figure 2m–o). Although cones fill the center of the Fwk 11 human fovea (Figure 3a, also see Bumsted & Hendrickson 1999), they do not express medium (M) or long (L) wavelength-selective opsin (M/L) until Fwk 15–16 (Figure 2d; Xiao & Hendrickson, 2000). The foveal cones are elongated by the appearance of a cone basal axon or fiber of Henle (Figure 3d, “A”) and a prominent pedicle (P) (Figure 3d,e). Syn and GluVT are intense in the pedicle (Figure 3d,e) but virtually absent from the cell body. Ribbon markers CTBP2 and Kin are prominent in all cone pedicles (Figure 3e,f).

By Fwk 18 Goα + bipolar cells have matured considerably (Figure 3g). They have fine dendrites basal to the cone pedicles in the OPL while their axons are clustered deep in the IPL. GR2/3 labeling is intense in the cytoplasm and dendrites of parvalbumen + (PV) horizontal cells (HZ) (Figure 3h). Many bipolar cell bodies label lightly and amacrine and ganglion cell bodies much more heavily for GR2/3; all neuronal types send processes into the IPL which is densely GR2/3 + throughout its thickness. A few small ganglion cells double label for PV (Figure 3h).

3.5 ∣. Human foveal development between Fwk 19 and 30

Foveal development in the latter half of gestation is mainly confined to the complex processes forming the foveal avascular zone and foveal pit. These are discussed elsewhere (Provis, Sandercoe, & Hendrickson, 2000; Robinson & Hendrickson, 1995; Springer & Hendrickson, 2004). An early stage of foveal cone displacement due to packing and/or pit formation can be detected by “cone tilt” accompanied by elongation of the cone axon (Figure 4a, arrow).

FIGURE 4.

Human and monkey foveal development near midgestation. (a) Fwk 24 human fovea stained with 1% azure II/methylene showing maturation of all layers (also see Figure 4 in Hendrickson, 2016 for larger views of histological sections). Cones (C) still are in a single layer, but have short axons and pedicles (arrow). The cone cell bodies tilt toward the center of the fovea (to left) as pit formation begins. (b) Fwk 24 human foveal cones (C) label for voltage-gated calcium channel α1.4 (VCa) in their axons (A) and pedicles (P), while the Goα + ON bipolar dendrites fill the OPL Goα + bipolar cell bodies (BP) are present in the IPL and Goα + axons fill the deep IPL Inset: A single VCa + cone axon and pedicle makes contact with the Goα + processes in the OPL. A single Goα + bipolar dendrite can be seen running into the OPL. (c) Fwk 24 human foveal cones have unlabeled pedicles whose base is metabotropic glutamate receptor 6 (mGluR6) + and Goα + (arrow) (d) Macaca fetal shortly after midgestation, around fetal day (Fd) 90 foveal cone pedicles (P) are Syn + and are contacted by mGluR6 + process tips. A well oriented pedicle is indicated by the arrow. Scale in d for d–f. (e) GluVT labeling outlines Macaca foveal cone pedicles (P) at around Fd90. These are contacted, and possibly invaginated, by mGluR6 + dendritic process tips. (f) Macaca parafoveal cones shortly after midgestation at around Fd105 have mGluR6+/Goα + dendritic processes (D) at the base of the unlabeled pedicles (arrow). Rod labeling is unclear

Given the early expression of so many cone presynaptic and postsynaptic markers, it is tempting to conclude that human cones could be “functional” by Fwk 18. However, labeling with two critical transmitter proteins indicated that this was not the case. No human retinas younger than Fwk 22 labeled for the ON bipolar metabotropic glutamate receptor 6 (mGluR6), or its critical co-molecule, voltage-gated calcium channel α1.4 (VCa) (data not shown). However, the oldest human fetal retinas in our collection that were suitable for immunolabeling of synaptic proteins are Fwk 22 and Fwk 24 (55–60% gestation), and both showed distinct membrane labeling for these markers at the base of cone pedicles only in the central fovea (Figure 4b,c). The VCa + cone axon and pedicle contacted underlying Goα + bipolar dendrites (Figure 4b). Likewise, mGluR6 + /Goα + processes contacted the cone pedicles (Figure 4c). Only the base of the pedicles was double labeled, suggesting that mGluR6 is present in the Goα + dendritic tips. No labeling was found outside the fovea at these ages.

3.6 ∣. Human and macaque monkey foveal development near midgestation

Given the age limitation in our human material, we turned to a collection of Macaca fetal and infant retinae to examine the expression pattern for these “late” markers. The pattern suggested in the human was confirmed in the macaque in that the first cytoplasmic pedicle labeling for mGluR6 or VCa was found near midgestation in central foveal cones (Figure 4d,e). Distinct mGluR6 + cone basal membrane labeling appeared outside the fovea shortly after midgestation at about Fd 105. Expression of these “late” markers slowly moved into peripheral retina with cone pedicles mGluR6 + at the eccentricity of the optic nerve at Fd 125 (74% gestation; data not shown), and at the edge of the retina by Fd 155, 2 weeks before birth (data not shown). Regardless of eccentricity, the presynaptic Syn + or GluVT + pedicle is contacted by mGluR6+/Goα + dendritic tips (Figure 4f). Thus, in humans these important components of the ON pathway appear more than 2 months after foveal cones have most other presynaptic and postsynaptic proteins and opsin. Judging from macaque labeling, we predict that in humans both markers would be expressed in cones at the optic nerve by Fwk 30, and at the retinal edge shortly after birth.

3.7 ∣. Electron microscopic development of outer retina

The electron microscopic development of Macaca foveal cones from Fd 55 to postnatal 3 months will be reported here as a general survey to expand the immunocytochemical findings. A more detailed report using serial reconstruction is being prepared.

At Fd 55 (=Fwk 10, see Table 2 for human/monkey conversions) large round cones (C) (Figure 5a) are in a single row separated by Müller cell (M) processes (Figure 5a) filled apically with small dark mitochondria. Membrane densities link cones and Müller cells (Figure 5a, arrowhead), indicating that the outer limiting membrane has formed. Cones have large IS (Figure 5a) which are tightly apposed to the PE with virtually no space between the two cell layers. This is consistent with the presence of IRBP-containing vesicles within the inner segments (Figure 2f). Cone inner segments are rich in ribosomes, large pale mitochondria, and large membranous vesicles, but have little rough endoplasmic reticulum. The base of the cone which will become the pedicle (P) (Figure 5b) also has ribosomes, mitochondria, and a few very small synaptic ribbons surrounded by a few synaptic vesicles. Most are in clusters, away from the membrane (Figure 5b arrow). The pedicle is flat and shows very few infoldings. Although synaptic immunomarkers SV2 and Syn were present at Fwk 8–10 (Figure 2b,c), the scarcity of ribbons may make them difficult to detect by immunolabeling. The OPL is thin, irregular and loosely filled with processes.

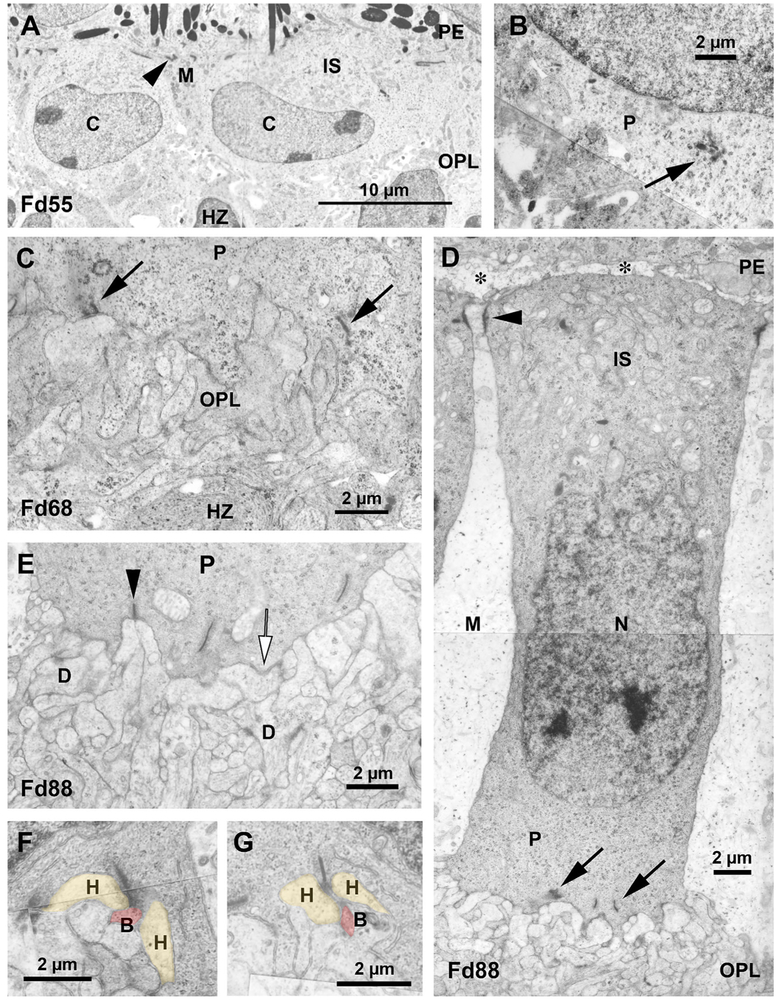

FIGURE 5.

Macaque foveal development. Low power electron micrograph showing two Macaca Fd 55 cones (C). The thick inner segments (IS) are closely adjacent to the PE. Apical Müller cell (M) processes make membrane contacts with cones (arrowhead). The OPL between the cones and HZ is thin, irregular, and contains loosely packed processes. The Macaca Fd 55 cone basal cytoplasm contains ribbon/vesicle clusters (arrow) and a few single ribbons. At Macaca Fd 68 the OPL is thicker and more processes are perpendicular to the cone pedicle (P). Synaptic ribbons (arrows) are oriented vertical to the membrane and are surrounded with vesicles. At Macaca Fd 88 cones are markedly elongated and are divided into distinct inner segment (IS), nucleus (N), and synaptic pedicle (P) regions. An interphotoreceptor space (asterisks) is appearing between cones and the PE. Pale Müller cells (M) form junctions (arrowhead) with the cones. The IS is rich in mitochondria and ribosomes. The pedicle contains multiple ribbons (arrows). Note some infolding of the pedicle by OPL processes. At Macaca Fd 88 some ribbons (arrowhead) are opposite two postsynaptic processes. Regions of the pedicle membrane (white arrow) are dense and closely contact a postsynaptic process. The OPL contains membrane densities (D) between processes. The first triad ribbon synapses were seen at Macaca Fd 88 but were uncommon at this age. The central presumably bipolar dendrite (B, pink) is more dense than the lateral horizontal processes (H, yellow). By Fd 110 in macaque synaptic ribbons contacting three postsynaptic densities forming a triad are more common (bipolar dendrite (B), pink; horizontal cell process (H), yellow)

At Fd 61 (=Fwk 12), the cones have not changed much in composition or shape. Müller cell cytoplasm is more pale than cone cytoplasm and thick Müller cell processes run between the cones. Cones are not totally separated in that cell–cell membrane contact is common. Our impression is that synaptic ribbons are more common at Fd 61, confirming the clear presence of ribbon immunomarkers at this age (Figure 2k–o). By Fd 68 (=Fwk 15; Figure 5c) the OPL was thicker with more tightly packed processes. Ribbons are longer and more common, with some perpendicular to the pedicle membrane (Figure 5c, arrows). OPL basal processes appear more vertically oriented and often make contact with the pedicle, with some processes infolded into the pedicle base. This may be correlated with the appearance of many immunolabeled bipolar dendrites and horizontal cell processes and receptors (Figure 2p–v) at this age.

A major change has occurred at Fd 88 (=Fwk 21) in that cones are much elongated from earlier ages and compartmented with definite mitochondria-filled inner segments, a ribosome-rich myoid, nucleus, and basal pedicle zones (Figure 5d). There is now some space between cones and PE which is filled with processes and extracellular matrix (Figure 5d, asterisks). This signals the shift from vesicular IRBP to extracellular IRBP immunolabeling seen in later ages (not shown). Müller cell (M) cytoplasm is pale and relatively free of organelles except for dark particles which are likely glycogen (Figure 5d). The outer limiting membrane junctions are dense and form a regular line near the cone apex (Figure 5d, arrowhead).

The Fd 88 OPL is thicker and more complex with membrane densities and conventional synapses between processes (Figure 5d,e). The cone base is more infolded with ribbons and vesicles adjacent to basal processes. Some of these pedicle-process membrane contacts have membrane densities (Figure 5e, white arrow). Some ribbons are opposite two processes forming a dyad synapse (Figure 5e, black arrowhead).

Ribbon synapses with three postsynaptic processes, or triads, were first seen at Fd 88 (Figure 5f) and were more common at Fd 110 (Figure 5g). Basal membrane densities opposite basal processes were also present. By comparison to 3-month-old retina (not shown), the synapses would continue to mature throughout the rest of gestation and into neonatal life.

4 ∣. DISCUSSION

This combined immunolabeling and EM study shows the very early development of the cone synaptic pedicle in the primate fovea. Although there are no labeling studies to determine when cones are “born” in humans, generation markers in monkeys (Hendrickson et al., 2016; La Vail et al., 1991) suggest cone generation begins early in Fwk 8, shortly after ganglion and horizontal cells are “born.” When cones can be recognized at Fwk 9, they contain Rec and Syn, and add SV2, IRBP, CTr, PSD, GluVT, and ribbon markers in the next 3 weeks. It is significant that at Fwk 13 the future foveal M/L cones express CTr, SV2, Syn, GluVT, CTBP2, Bass, Kin, and PSD, but not opsin, indicating that M/L foveal cones are actively forming transduction proteins, synaptic ribbons, and vesicular proteins well before opsin expression. By contrast, these synaptic markers are present in S cones concurrent with S opsin expression at Fwk 11. This difference between cone types suggests that the presence of opsin per se has little to do with directing synaptic formation.

There are only a few studies regarding synaptic development in primate retina. In marmoset, a similar early expression pattern to humans has been found for cone synaptic immunolabels (Hendrickson et al., 2009). The lack of a causal interaction between opsin/synapse expression is well demonstrated in marmoset where S opsin is the last opsin to be expressed, appearing after both M/L and rod opsin. Yet in both cone types, synaptic markers are found 2–3 weeks before opsin, while in rods opsin appears 2–4 weeks before synaptic markers. Likewise in human rods (Hendrickson et al., 2008) rod opsin is present before synapses. The EM appearance of foveal synapses has been reported for the macaque IPL (Crooks et al, 1995). Ribbon-containing bipolar synapses are sparse but present at Fd 55 (32% gestation). Amacrine conventional synapses appear at Fd 68 (40% gestation), and then increase dramatically in number by Fd 88 (52% gestation). This predicts that ribbons should appear at Fwk 12–13 in the human IPL. We have had difficulty detecting IPL, but not OPL, ribbon immunomarkers this early which may be due to their scarcity at these early ages. However, presynaptic and postsynaptic markers such as SV2, Syn, PSD, GR2/3, and GluVT (also see Okada et al., 1994) are abundant in the Fwk 13 IPL and are beginning to be stratified.

The preliminary EM of monkey IPL presented in this article supports the early presence of ribbon immunomarkers in human retina, and their increase both in size and number from Fwk 11–18. Triad synapses with two horizontal and one bipolar process did not appear until 52% gestation or Fwk 20–21. It may be significant that this is the time when mGluR6 and VCa are first detected in foveal cone pedicles. What triggers these proteins so long after most other ribbon, vesicle, and receptor markers are present in cones remains to be determined.

In mouse retina, ribbon synaptic proteins appear at different stages of development, following a similar temporal sequence to human (summarized by Hoon, Okawa, Della Santina, & Wong, 2014). For example, SV2, Syn (von Kriegstein & Schmitz, 2003; Wang, Janz, Belizaire, Frishman & Sherry, 2003), and GluVT (Sherry et al., 2003) are already prominently expressed at postnatal day (P) 0-2, and Bass and CTBP2 are expressed at P 4-5 when formation of ribbons is initiated (Regus-Leidig, Tom Dieck, Specht, Meyer, & Brandstatter, 2009). Similar to primates, mGluR6 and VCa are expressed later at P11-14 around eye opening, when bipolar invagination largely occurs (Cao et al., 2015; Dunn & Wong, 2012; Tummala, Neinstein, Fina, Dhingra, & Vardi, 2014). Therefore, the similarities in ribbon formation and synaptogenesis in mouse and primates may shed light on the mechanism behind the nonsynchronous expression pattern of synaptic proteins in human/primate retina.

Early in synaptic formation, an interaction between Bass and CTBP2 is required for anchoring floating ribbons at the active zone or release site; in turn this is crucial for bipolar invagination (Dick et al., 2003; tom Dieck et al., 2005; Regus-Leidig et al., 2009). mGluR6 and VCa require each other to be expressed and participate in maturation of ribbon synapses at photoreceptor axon terminals (Cao et al., 2015; Specht et al., 2009; Tummala et al., 2014; Zabouri & Haverkamp 2013). Therefore, it is not surprising that proteins that are functionally associated get expressed neck-to-neck in the same time window. Moreover, the expression of mGluR6 may require the function of proteins expressed much earlier; for example, dark rearing (Dunn, Della Santina, Parker, & Wong, 2013), or blocking vesicle exocytosis in photoreceptors (Cao et al., 2015) significantly reduces mGluR6 expression in the OPL. This implies an important role of glutamatergic vesicular release in mGluR6 expression that may involve SV2, Syn, and GluVT. The same late developmental time window of mGluR6 expression and bipolar invagination in mouse (P11-14; Hoon et al., 2014; Tummala et al., 2014) and primate (Fd 88 monkey; Fwk 22 human; our data) suggests a potential relationship between these two events. However, in Bass mutants where ribbons fail to be anchored and bipolar invagination is disrupted, mGluR6 expression remains normal (Dick et al., 2003) and the knockout of mGluR6 does not prevent bipolar invagination (Tsukamoto & Omi, 2013). Therefore, although lack of mGluR6 expression often occurs together with no bipolar invagination (Cao et al., 2015; Zabouri & Haverkamp, 2013), it is unlikely that bipolar invagination is a limiting factor for mGluR6 to be expressed. In conclusion, it can be postulated that during photoreceptor synaptogenesis the expression of mGluR6 requires the pre-existence of active presynaptic glutamatergic vesicular release, but not bipolar invagination. Because mGluR6 expression occurs at or after eyelid opening in mice, but in primates occurs long before birth, this suggests that primate photoreceptors have sufficient glutamate release at midgestation to initiate mGluR6 expression. We cannot discount other undiscovered molecules or events that are also responsible for the late expression of mGluR6.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Much of this work was done while AH was a visiting Alexander von Humboldt Professor at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research, Frankfurt, Germany. AH wishes to thank Director Heinz Wässle, Helmut Brandstätter, and Silke Haverkamp for their assistance and for the generous sharing of antibodies. We are grateful to Dr. J. Crooks for the use of fetal monkey montages. The technical assistance of Toni Haun, Jim Kuchenbecker, Jing Huang, and Dan Possin are gratefully acknowledged. AH wishes to thank the families of eye donors. The authors thank Maureen Neitz for her assistance in preparing the final revision. This work was supported by an unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology from Research to Prevent Blindness, and NIH/NEI grant P30 EY001730.

Funding information

Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Bonn, Germany; UW Department of Ophthalmology; NIH/NEI (VRC core), Grant/Award Number: P30 EY001730

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There is no identified conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Bajjalieh SM (1999). Synaptic vesicle docking and fusion. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 9(3), 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandstatter JH, Fletcher EL, Garner CC, Gundelfinger ED, & Wassle H (1999). Differential expression of the presynaptic cytomatrix protein bassoon among ribbon synapses in the mammalian retina. European Journal of Neuroscience, 11(10), 3683–3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley K, & Kelly RB (1985). Identification of a transmembrane glycoprotein specific for secretory vesicles of neural and endocrine cells. Journal of Cell Biology, 100(4), 1284–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumsted K, & Hendrickson A (1999). Distribution and development of short-wavelength cones differ between Macaca monkey and human fovea. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 403(4), 502–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumsted K, Jasoni C, Szel A, & Hendrickson A (1997). Spatial and temporal expression of cone opsins during monkey retinal development. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 378(1), 117–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral AL, Santana RF, da Silva VO, de Toledo CA (2010). GluR2/3 label expression of the AMPA-type glutamate receptor in the hippocampal formation of the homing pigeon stabilizes just after birth. Neuroscience Letters, 483(1), 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Singh BB, Aslanukov A, Zhao H, & Ferreira PA (2001). The docking of kinesins, KIF5B and KIF5C, to Ran-binding protein 2 (RanBP2) is mediated via a novel RanBP2 domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 276(45), 41594–41602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Sarria I, Fehlhaber KE, Kamasawa N, Orlandi C, James KN, … Martemyanov KA (2015). Mechanism for selective synaptic wiring of rod photoreceptors into the retinal circuitry and its role in vision. Neuron, 87(6), 1248–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celio MR, Baier W, Scharer L, de Viragh PA, & Gerday C (1988). Monoclonal antibodies directed against the calcium binding protein parvalbumin. Cell Calcium, 9(2), 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks J, Okada M, & Hendrickson AE (1995). Quantitative analysis of synaptogenesis in the inner plexiform layer of macaque monkey fovea. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 360(2), 349–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio CA, Sloan KR, Kalina RE, & Hendrickson AE (1990). Human photoreceptor topography. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 292(4), 497–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra A, Lyubarsky A, Jiang M, Pugh EN Jr., Birnbaumer L, Sterling P, & Vardi N (2000). The light response of ON bipolar neurons requires G[alpha]o. Journal of Neuroscience, 20(24), 9053–9058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Araya C, & Provis JM (1992). Evidence of photoreceptor migration during early foveal development: A quantitative analysis of human fetal retinae. Visual Neuroscience, 8(6), 505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick O, tom Dieck S, Altrock WD, Ammermuller J, Weiler R, Garner CC, … Brandstatter JH (2003). The presynaptic active zone protein bassoon is essential for photoreceptor ribbon synapse formation in the retina. Neuron 37(5), 775–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn FA, Della Santina L, Parker ED, & Wong RO (2013). Sensory experience shapes the development of the visual system’s first synapse. Neuron, 80(5), 1159–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn FA, & Wong RO (2012). Diverse strategies engaged in establishing stereotypic wiring patterns among neurons sharing a common input at the visual system’s first synapse. Journal of Neuroscience, 32 (30), 10306–10317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastinger MJ, Barber AJ, Vardi N, & Marshak DW (2006). Histamine receptors in mammalian retinas. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 495(6), 658–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagino-Yamagishi K, & Nakazawa H (2011). Involvement of Galpha (olf)-expressing neurons in the vomeronasal system of Bufo japonicus. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 519(16), 3189–3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkamp S, Haeseleer F, & Hendrickson A (2003). A comparison of immunocytochemical markers to identify bipolar cell types in human and monkey retina. Visual Neuroscience, 20(6), 589–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkamp S, & Wassle H (2000). Immunocytochemical analysis of the mouse retina. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 424(1), 1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson A (1992). A morphological comparison of foveal development in man and monkey. Eye (London, England), 6(Pt 2), 136–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson A (2016). Development of retinal layers in prenatal human retina. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 161, 29–35.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson A, Bumsted-O’Brien K, Natoli R, Ramamurthy V, Possin D, & Provis J (2008). Rod photoreceptor differentiation in fetal and infant human retina. Experimental Eye Research, 87(5), 415–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson A, & Kupfer C (1976). The histogenesis of the fovea in the macaque monkey. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 15(9), 746–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson A, Possin D, Kwan WC, Huang J, & Bourne JA (2016). The temporal profile of retinal cell genesis in the marmoset monkey. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 524(6), 1193–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson A, Possin D, Vajzovic L, & Toth CA (2012). Histologic development of the human fovea from midgestation to maturity. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 154(5), 767–778.e762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson A, & Provis J (2006). Comparison of development of the primate fovea centralis with peripheral retina In Serenger E, Harris W, Eglen S, Wong RO (Eds.), Retinal Development (pp. 126–149). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson A, Troilo D, Djajadi H, Possin D, & Springer A (2009). Expression of synaptic and phototransduction markers during photoreceptor development in the marmoset monkey Callithrix jacchus. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 512(2), 218–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson AE, & Yuodelis C (1984). The morphological development of the human fovea. Ophthalmology, 91(6), 603–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoon M, Okawa H, Della Santina L, & Wong RO (2014). Functional architecture of the retina: Development and disease. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 42, 44–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jusuf PR, Martin PR, & Grunert U (2006). Synaptic connectivity in the midget-parvocellular pathway of primate central retina. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 494(2), 260–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KE, Zhang AJ, Wu SM, & Marshak DW (2009). Parvalbumin-immunoreactive amacrine cells of macaque retina. Visual Neuroscience, 26(3), 287–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koontz MA, & Hendrickson AE (1993). Comparison of immunolocalization patterns for the synaptic vesicle proteins p65 and synapsin I in macaque monkey retina. Synapse (New York, NY), 14(4), 268–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Vail MM, Rapaport DH, & Rakic P (1991). Cytogenesis in the monkey retina. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 309(1), 86–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerea CL, Bunt-Milam AH, & Hurley JB (1989). Alpha transducin is present in blue-, green-, and red-sensitive cone photoreceptors in the human retina. Neuron, 3(3), 367–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linberg KA, & Fisher SK (1990). A burst of differentiation in the outer posterior retina of the eleven-week human fetus: an ultrastructural study. Visual Neuroscience, 5(1), 43–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PR, & Grunert U (1999). Analysis of the short wavelength-sensitive (“blue”) cone mosaic in the primate retina: comparison of New World and Old World monkeys. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 406(1), 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milam AH, Dacey DM, & Dizhoor AM (1993). Recoverin immunoreactivity in mammalian cone bipolar cells. Visual Neuroscience, 10(1), 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura Y, Mogi K, Kawano M, Fukui Y, Takeda J, Nogami H, & Hisano S (2002). Differential expression of two distinct vesicular glutamate transporters in the rat retina. Neuroreport, 13(15), 1925–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M, Erickson A, & Hendrickson A (1994). Light and electron microscopic analysis of synaptic development in Macaca monkey retina as detected by immunocytochemical labeling for the synaptic vesicle protein, SV2. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 339(4), 535–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer O, Hendrickson AE, & Curcio CA (1990). Development redistribution of photoreceptors across the Macaca nemestrina (pig-tail macaque) retina. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 298(4), 472–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister KK, Wagner MC, Stenoien DL, Brady ST, & Bloom GS (1989). Monoclonal antibodies to kinesin heavy and light chains stain vesicle-like structures, but not microtubules, in cultured cells. Journal of Cell Biology, 108(4), 1453–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak S (1941). The retina. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Provis JM, Dubis AM, Maddess T, & Carroll J (2013). Adaptation of the central retina for high acuity vision: Cones, the fovea and the avascular zone. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 35, 63–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provis JM, Sandercoe T, & Hendrickson AE (2000). Astrocytes and blood vessels define the foveal rim during primate retinal development. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 41(10), 2827–2836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthussery T, Percival KA, Venkataramani S, Gayet-Primo J, Grunert U, & Taylor WR (2014). Kainate receptors mediate synaptic input to transient and sustained OFF visual pathways in primate retina. Journal of Neuroscience, 34(22), 7611–7621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regus-Leidig H, Tom Dieck S, Specht D, Meyer L, & Brandstatter JH (2009). Early steps in the assembly of photoreceptor ribbon synapses in the mouse retina: The involvement of precursor spheres. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 512(6), 814–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SR, & Hendrickson A (1995). Shifting relationships between photoreceptors and pigment epithelial cells in monkey retina: Implications for the development of retinal topography. Visual Neuroscience, 12(4), 767–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues MM, Hackett J, Gaskins R, Wiggert B, Lee L, Redmond M, & Chader GJ (1986). Interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein in retinal rod cells and pineal gland. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 27(5), 844–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears S, Erickson A, & Hendrickson A (2000). The spatial and temporal expression of outer segment proteins during development of Macaca monkey cones. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 41(5), 971–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry DM, Wang MM, Bates J, & Frishman LJ (2003). Expression of vesicular glutamate transporter 1 in the mouse retina reveals temporal ordering in development of rod vs. cone and ON vs. OFF circuits. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 465(4), 480–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specht D, Wu SB, Turner P, Dearden P, Koentgen F, Wolfrum U, … tom Dieck S (2009). Effects of presynaptic mutations on a postsynaptic Cacna1s calcium channel colocalized with mGluR6 at mouse photoreceptor ribbon synapses. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 50(2), 505–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer AD (1999). New role for the primate fovea: A retinal excavation determines photoreceptor deployment and shape. Visual Neuroscience, 16(4), 629–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer AD, & Hendrickson AE (2004). Development of the primate area of high acuity. 1. Use of finite element analysis models to identify mechanical variables affecting pit formation. Visual Neuroscience, 21(1), 53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer AD, Troilo D, Possin D, & Hendrickson AE (2011). Foveal cone density shows a rapid postnatal maturation in the marmoset monkey. Visual Neuroscience, 28(6), 473–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- tom Dieck S, Altrock WD, Kessels MM, Qualmann B, Regus H, Brauner D, … Brandstatter JH (2005). Molecular dissection of the photoreceptor ribbon synapse: Physical interaction of Bassoon and RIBEYE is essential for the assembly of the ribbon complex. Journal of Cell Biology, 168(5), 825–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto Y, & Omi N (2013). Functional allocation of synaptic contacts in microcircuits from rods via rod bipolar to All amacrine cells in the mouse retina. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 521(15), 3541–3555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tummala SR, Neinstein A, Fina ME, Dhingra A, & Vardi N (2014). Localization of Cacna1s to ON bipolar dendritic tips requires mGluR6-related cascade elements. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 55(3), 1483–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vajzovic L, Hendrickson AE, O’Connell RV, Clark LA, Tran-Viet D, Possin D, … Toth CA (2012). Maturation of the human fovea: Correlation of spectral-domain optical coherence tomography findings with histology. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 154(5), 779–789.e772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardi N, Duvoisin R, Wu G, & Sterling P (2000). Localization of mGluR6 to dendrites of ON bipolar cells in primate retina. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 423(3), 402–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Kriegstein K, & Schmitz F (2003). The expression pattern and assembly profile of synaptic membrane proteins in ribbon synapses of the developing mouse retina. Cell Tissue Research, 311(2), 159–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Macke JP, Merbs SL, Zack DJ, Klaunberg B, Bennett J, … Nathans J (1992). A locus control region adjacent to the human red and green visual pigment genes. Neuron, 9(3), 429–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MM, Janz R, Belizaire R, Frishman LJ & Sherry DM (2003). Differential distribution and developmental expression of synaptic vesicle protein 2 isoforms in the mouse retina. Journal of Comparative Neurology 460(1), 106–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggert B, Lee L, Rodrigues M, Hess H, Redmond TM, & Chader GJ (1986). Immunochemical distribution of interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein in selected species. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 27(7), 1041–1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao M, & Hendrickson A (2000). Spatial and temporal expression of short, long/medium, or both opsins in human fetal cones. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 425(4), 545–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuodelis C, & Hendrickson A (1986). A qualitative and quantitative analysis of the human fovea during development. Vision Research, 26 (6), 847–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabouri N, & Haverkamp S (2013). Calcium channel-dependent molecular maturation of photoreceptor synapses. PLoS One, 8(5), e63853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]