Abstract

Introduction PCOS is the most common endocrine syndrome in women of the reproductive age that has manifold effects on the life of affected women. Little scientific attention has been devoted to these womenʼs sexual lives.

Aim To investigate sexual quality of life in women with PCOS.

Methods The sample size was n = 44. Measures employed were: An extended list of sexual dysfunctions and perceived distress based on DSM-IV-TR, Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), German Questionnaire on Feelings of Inadequacy in Social and Sexual Situations (FUSS), Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE), Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) subscale depression. The relationships of these components were examined including further variables (body mass index, degree of hirsutism using the Ferriman-Gallwey Score, wish for a child). An open question about what participants see as the source of their sexual problems was presented.

Results Only moderate impairment in sexual function was detected, but feelings of inadequacy in social and sexual situations were markedly elevated and positively correlated with the degree of hirsutism. Depression showed to be a major problem.

Conclusion Patients with PCOS should be screened for socio-sexual difficulties and emotional problems. Specialized psychological and sexological counselling can complement patient care.

Key words: polycystic ovary syndrome, sexual quality of life, feelings of inadequacy in social and sexual situations, depression, hirsutism

Zusammenfassung

Einleitung PCOS ist die häufigste endokrine Störung bei Frauen im gebärfähigen Alter und kann vielfältige Auswirkungen auf das Leben betroffener Frauen haben. Bislang wurde dem Sexualleben von betroffenen Frauen wenig Aufmerksamkeit gewidmet.

Ziel Ziel dieser Studie war es, die sexuelle Lebensqualität von Frauen mit PCOS zu untersuchen.

Methoden Die Fallzahl betrug n = 44. Folgende Fragebogen wurden zur Untersuchung verschiedenster Aspekte herangezogen: Sexualstörungen und subjektiv wahrgenommenes Leiden basierend auf dem DSM-IV-TR, dem Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), dem Fragebogen zur Unsicherheit in sexuellen Situationsen (FUSS), der Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE), der Subskala Depressivität des Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI). Die Beziehungen der verschiedenen Aspekte untereinander wurden zusammen mit weiteren Variablen (Body-Mass-Index, Ausmaß des Hirsutismus gemessen mit dem Ferriman-Gallwey-Score, Kinderwunsch) untersucht. Den Teilnehmerinnen wurde ein offener Fragenbogen vorgelegt, in dem sie sich darüber äußern sollten, was sie als die Ursache ihrer Sexualprobleme betrachteten.

Ergebnisse Während die Sexualfunktion nur moderat beeinträchtigt war, waren Unsicherheitsgefühle in soziosexuellen Situationen signifkant erhöht und korrelierten positiv mit dem Ausmaß des Hirsutismus. Es zeigte sich, dass Depression ein erhebliches Problem darstellte.

Schlussfolgerung Patientinnen mit PCOS sollten auf soziosexuelle Schwierigkeiten und emotionalen Probleme untersucht werden. Eine zielgerichtete psychologische Beratung sowie eine Sexualberatung könnten eine sinnvolle Ergänzung der Patientinnenversorgung sein.

Schlüsselwörter: polyzystisches Ovarsyndrom, sexuelle Lebensqualität, Unsicherheit in sexuellen Situationen, Depression, Hirsutismus

Introduction

Sexuality has a high impact on the overall well-being 1 . Sexual quality of life comprises all aspects that result in a satisfying sexuality. That means sexual quality of life is more than the mere absence of an illness or a disorder that might impair sexual functioning. It also involves the ability to fall in love, to initiate and maintain a sexual and romantic relationship and to feel certain about oneʼs own sexuality 2 . A sexual disorder can be an indicator for an impaired sexual quality of life but sexual well-being should be assessed in more detail. Moreover, overall physical functioning, partnership, and the self-worth have been identified to influence sexual quality of life 1 , 3 . Additionally, the attitude towards the own body, more specific the genitals 4 , 5 , 6 and the body image 7 , have an effect on our sexuality.

The most common endocrinopathy amongst women at the reproductive stage 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , the polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) with a prevalence rate of about 5% 12 , 13 or even up to 17.8% in a community sample 14 , is associated with an impaired general quality of life and psychological well-being in affected women 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 . However, not much is known about the sexual quality of life of women with PCOS. Most research focuses on sexual function whereby most studies report only global scores (e.g. 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ) and specific sexual dysfunctions are only sporadically reported 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 . So far it appears that sexual satisfaction and sexual self-worth are impaired 16 , 23 , 24 , 29 , 30 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 . More research on sexual quality of life is necessary because PCOS affects a high number of women and is associated with a number of symptoms that each by itself can mediate sexuality.

The syndrome is currently defined as a combination of hyperandrogenism (hirsutism and/or hyperandrogenemia) and ovarian dysfunction (oligo-anovulation and/or polycystic ovaries) (NIH criteria 38 ; Rotterdam criteria 39 ). Affected women face multiple problems, for example menstrual irregularities or amenorrhea, hirsutism, acne, alopecia and obesity while there is a wide variety in the clinical presentation 40 .

Obesity has been documented to have a negative effect on sexuality 41 , 42 , but in women with PCOS the results are mixed 23 , 26 , 41 , 42 .

Hirsutism has been described to have aversive effects on sexuality by causing body dissatisfaction and interfering with the womenʼs feminine self-perception 16 , 25 , 29 , 31 , 37 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 . Infertility is a burden that can lead to marital problems and sexual dysfunction 48 , 49 , 50 . Barnard et al. found that infertility was the third most troubling symptom of PCOS after weight concerns and menstrual problems 51 . A negative association between the wish for a child and sexual well-being in women with PCOS would thus seem plausible.

Literature on self-esteem and sexuality seems to support a positive relationship between these two variables 3 . Low self-esteem can also adversely affect a personʼs body image and in this way negatively influence sexuality 3 , 52 , 53 . Systematic studies on self-esteem in women with PCOS are scarce 20 , 30 , 37 , 44 , 54 . Depression or more generally mood is a known mediator in female sexual function 55 , 56 . Depression has often been reported to be elevated in women with PCOS 17 , 24 , 36 , 51 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , a negative influence on sexuality in PCOS patients could thus be expected.

Aims

This study is designed to investigate sexual quality of life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). First, sexual difficulties and perceived distress will be described at the level of individual sexual problems as outlined in the DSM-IV-TR of the American Psychiatric Association 61 . The second aim is to explore total sexual function scores, feelings of inadequacy in social and sexual situations as well as to take a look at general self-esteem and depression. Third, the relationships of these variables will be examined linking them to putative mediators such as body mass index, the wish for a child and hirsutism. The study will close with an inquiry about what participants see as the source of their sexual problems.

Materials and Methods

Procedure

This cross-sectional study was conducted within the scope of the research project “Androgens, Quality of Life and Femininity in People with Complete Androgen Insensitivity (CAIS), Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser Syndrome (MRKHS) and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)” at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Institute for Sex Research and Forensic Psychiatry. Recruitment of participants was accomplished by contacting support groups and professionals in the field of gynaecology and endocrinology and via an internet announcement.

An extensive paper & pencil questionnaire was developed which included standardised as well as self-developed scales and open questions. The study employed scales and questions also used in a previously conducted study on intersex conditions – University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Institute for Sex Research and Forensic Psychiatry 62 , 63 , 64 . Participants filled out the questionnaire at home or at the research centre. A compensation of 20 EUR was granted. The data were collected between 03/2010 and 07/2011. The study was approved of by the ethics committee.

Participants

Participants had to be of full legal age (≥ 18 years) and data were included only if informed consent had been given. Diagnostic information was accepted with a differentiation between two levels of confirmation: Participants had to confirm that they had the polycystic ovary syndrome and that they had been diagnosed by a medical doctor. This was considered “second degree confirmation”. If consent was given, the attending medical doctors were contacted and asked to verify the diagnosis and send in medical records. Diagnoses attested directly by doctors were considered “first degree confirmation”.

Outcome measures

Sexual problems and dysfunctions

A list of sexual problems was presented. It was developed based on DSM-IV-TR diagnoses 61 , but extended to include further problems 62 . First, participants had to indicate whether the respective situation was true for them (“yes” or “no”) and then, whether this problem caused them distress (“yes” or “no”). A mean number of sexual problems was calculated (maximum: 12).

Comparison data were available from a previous study by the authors 65 . Sexual problems that required previous sexual experience were only analysed in experienced individuals.

Standardised scales

All scores were calculated according to the manuals. For all scales satisfactory to excellent psychometric properties are reported 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 .

Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI)

The Female Sexual Function Index 66 , 70 is a self-report scale used to assess sexual function in women during the past four weeks. Full-scale scores range from 2.0 to 36.0, with high numbers indicating better sexual function. Comparison data were available from the publication by Rosen 66 . Full-scale scores have been classified as “poor” when ≤ 23, as “good” or “satisfactory” when within the range of 24 – 29, and as “very good” when ≥ 30 71 , 72 .

Feelings of Inadequacy in Social and Sexual Situations (FUSS)

The questionnaire by Fahrner assesses feelings of inadequacy during interactions with a potential or an actual romantic partner 73 . It contains two subscales: “social” and “sexual”. Each subscale consists of 11 statements. Participants indicate their level of agreement (0 = “not at all true” and 5 = “absolutely true”). “I feel anxious when talking to an attractive man/woman” is an example of a social situation that might trigger feelings of inadequacy (FUSS social), “I donʼt know how to tell a man/woman when I would like to have sex with him/her” refers to insecurity in the sexual domain (FUSS sexual). Comparison data from a healthy control group were available from the publication by Fahrner 73 .

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE)

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale 74 is measure for the assessment of global self-worth 67 , 75 , 76 . The scale consists of 10 statements scaled 1 (“not true at all”) to 4 (“absolutely true”). A high RSE score (max. 40) represents high self-confidence. The current study employed the version by von Collani and Herzberg 68 . Comparison data from a non-clinical sample were available from a publication by Martín-Albo et al. 77 .

Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)

The Brief Symptom Inventory is a questionnaire on psychological distress by Derogatis and Melisaratos 69 , 78 . It is divided into 9 subscales. In this study only the depression subscale was employed. Original scores are transformed into t-scores according to the manualʼs norm charts. T-values ≥ 63 are classified as clinically relevant 69 .

Ferriman Gallwey Score (FG)

Hirsutism was assessed using the modified Ferriman-Gallwey method 79 , 80 , 81 including nine body parts. FG-Scores ≥ 6 were considered significant hirsutism 12 , 82 .

Wish for a child

The intensity of the participantsʼ current wish for a child was assessed using a single question: “How much would you currently like to have a child?” The answer was measured on a Likert scale of 1 “not” to 5 “very much”.

Open question on alleged cause(s) of sexual problems

The list of Sexual Problems and Dysfunctions was supplemented by an open question: “If you have any of the sexual problems mentioned above, what do you think is/are the reason(s) for it?”

Statistical methods

All calculations were conducted using the SPSS software package PASW Statistics 18.0.0.

Categorical data were compared using Pearsonʼs χ 2 , when expected frequencies were not adequate Fisherʼs exact probability test was used instead.

Differences between the PCOS group and comparison samples 66 , 73 , 77 were analysed using t-tests (check Table 2 ).

Table 2 Psychosexual variables, self-esteem and depression in PCOS: group comparisons.

| PCOS n = 44 |

Comparison samples | PCOS vs. controls | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t-tests | |||

|

1

ns “not significant”, * significant at α-level of 5%, ** significant at α-level of 1%, *** significant at α-level of 0.1%

2 Full scale scores are “poor” when ≤ 23, as “good” or “satisfactory” when within the range of 24 – 29, and as “very good” when ≥ 30 61 , 62 . 3 High scores indicate high levels of insecurity. 4 Items scaled: 1 – 4, high scores indicate high self-esteem 5 t-scores standardization: M = 50, SD = 10; in the BSI t-scores ≥ 63 are seen as clinically relevant, high scores indicate high levels depression 59 | |||||

| Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) | |||||

| Full-scale score 2 | 27.5 (5.33) | 30.5 (5.29) | Rosen et al. 66 | *** | t(40) = − 3.59, p ≤ 0.001, r = 0.49 |

|

n = 3 | ||||

| Feelings of Inadequacy in Social and Sexual Situations (FUSS) 3 | |||||

| Social insecurity – Scale 1 | 14.4 (11.92) | 9.82 (7.35) | Fahrner et al. 73 | * | t(43) = 2.54, p = 0.015, r = 0.36 |

|

– | ||||

| Sexual insecurity – Scale 2 | 17.7 (10.71) | 11.82 (7.79) | Fahrner et al. 73 | *** | t(43) = 3.62, p ≤ 0.001, r = 0.48 |

|

– | ||||

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE) | |||||

| Total Score 4 | 30.9 (5.73) | 31.1 (4.55) | Martín-Albo et al. 77 | ns | t(40) = − 0.25, p = 0.805, r = 0.04 |

|

n = 3 | ||||

| Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) Depression Scale | |||||

| Mean t-score 5 | 62.0 (11.71) | – | Franke 69 | ||

|

– | ||||

Continuous data were categorised in order to find out how many individuals showed critical scores. For both FUSS scales and the RSE scale each individualʼs score was z-transformed. Scores above + 1.64 (FUSS social, FUSS sexual) or below − 1.64 (RSE) were defined as “critical”, for in the general population only 5% of the people would be expected to show scores this extreme. For the FSFI and the BSI depression scale categorisations were already available (see above).

Pearsonʼs correlations were employed to identify relationships between variables.

For better comparability between measures effect sizes were calculated for Mann–Whitney U and t-tests and expressed as correlation coefficient r, whereby r ≥ 0.10 stands for a small, r ≥ 0.30 for a medium and r ≥ 0.50 for a large effect 83 .

Qualitative data were analysed using Mayringʼs qualitative content analysis method 84 . Numbers and ratios of participants who mentioned a derived topic are given. Ratios refer to the total number of people who gave an answer to the question.

Results

Participants

Eleven questionnaires had to be discarded at the outset (no informed consent, unclear or missing diagnosis). Of the remaining 55 participants, another eleven were excluded (currently pregnant, recently delivered a baby). A total of 44 data sets could finally be included in the study.

The diagnosis was confirmed by a medical doctorʼs statement or medical records (“first degree confirmation”) for 27 (61.4%) participants. For the rest 17 (38.6%) “second degree confirmation” was available. 21 (47.7%) women were informed about the study by a fertility clinic.

Sample characteristics

The median age of the participants was 28.5 years (Q 25 = 27.0, Q 75 = 30.8). The PCOS group showed the following median level of education of 4.0 (Q 25 = 3.0, Q 75 = 6.0). A value of 4 corresponds to German “Abitur” which is equivalent to 12 – 13 years of schooling. 84.1% (n = 37) reported being in a relationship whereby the partnerships were exclusively heterosexual. The sampleʼs median body mass index (BMI) was 25.8 (Q 25 = 21.2, Q 75 = 32.6). 21 (47.7%) women had a BMI below 25, eight (18.2%) participants were overweight (BMI ≥ 25 to < 30) and 15 (43.1%) were obese (BMI ≥ 30).

The participantsʼ current wish for a child was Md = 5.0 (Q 25 = 3.0, Q 75 = 5.0) which is the maximum possible value and corresponds to a very strong wish for a child.

Hirsutism as assessed by the modified Ferriman-Gallwey method yielded a median score of 7.5 (Q 25 = 4.0, Q 75 = 13.75), with n = 27 (61.4%) showing relevant hirsutism as defined by a FG-score ≥ 6 points 12 , 82 .

Descriptive data – PCOS symptoms and sexual experience

For information on menstruation, acne, greasy hair (“seborrhea”) and hair loss (“alopecia”) check Table 1 .

Table 1 Descriptive data – PCOS symptoms and sexual experience.

| Variables | PCOS n = 44 |

|---|---|

|

1

Percentages add up to 100%

2 Item scale: 1 (“very dissatisfied”) – 5 (“very satisfied”) | |

| n (%) 1 | |

| Menstruation | |

|

14 (31.8) |

|

27 (61.4) |

|

3 (6.8) |

| Acne | |

|

17 (38.6) |

|

25 (56.8) |

|

2 (4.5) |

| Greasy hair | |

|

24 (54.5) |

|

19 (43.2) |

|

1 (2.3) |

| Hair loss | |

|

7 (15.9) |

|

33 (75.0) |

|

4 (9.1) |

| Intercourse experience | |

|

43 (97.7) |

|

1 (2.3) |

|

– |

| Masturbation experience | |

|

38 (86.4) |

|

6 (13.6) |

|

– |

| Orgasm experience | |

|

41 (93.2) |

|

– |

|

3 (6.8) |

|

Mdn (Q

25

– Q

75

)

Range |

|

| Age at first intercourse (yrs.) | 17.5 (16.0 – 20.0) 13.0 – 30.0 |

|

n = 2 (4.5%) |

| Age at first masturbation (yrs.) | 14.0 (13.0 – 16.5) 5.0 – 30.0 |

|

n = 7 (15.9%) |

| Satisfaction with sex life 2 | 3.0 (2.0 – 4.0) 1.0 – 5.0 |

|

n = 1 (2.3%) |

43 women (97.7%) indicated having had sexual intercourse at least once in a lifetime, 38 women (86.4%) reported having masturbated in the past. 41 of the women (93.2%) reported orgasm experience. Median age at first intercourse was 17.5 years (Q 25 = 16.0, Q 75 = 20.0), median age at first masturbation was 14.0 years (Q 25 = 13.0, Q 75 = 16.5). Satisfaction with sex life was a median of 3.0 (Q 25 = 2.0, Q 75 = 4.0) which stands for “moderately satisfied”, the item scale ranged from 1 (“very dissatisfied”) to 5 (“very satisfied”). Please check Table 1 .

Main Results

Sexual problems and dysfunctions

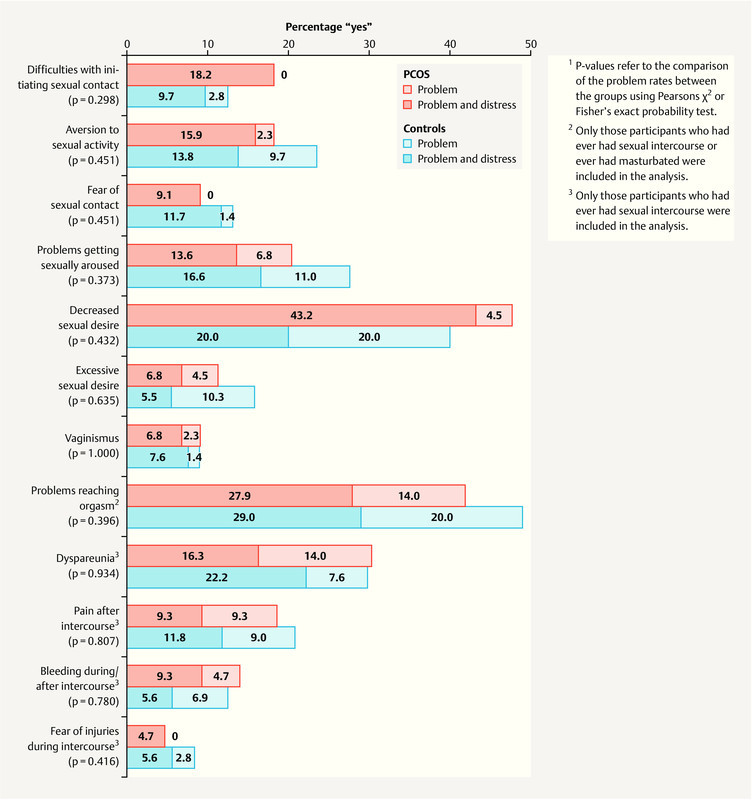

No differences were observed between PCOS and a non-clinical convenience sample (data were collected in a previous study, see 65 ) regarding sexual problem rates. For an overview of sexual problem rates and distress see Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Sexual problems and dysfunctions: problem rates and distress.

The PCOS group and the control sample did not differ significantly in terms of the number of sexual problems (Mann–Whitney U = 2479.5, p = 0.673, r = − 0.03; PCOS: Md = 2.0, Q 25 –Q 75 = 0.00 – 4.00, missing n = 5; non-clinical controls: Md = 3.0, Q 25 –Q 75 = 1.00 – 4.00, missing n = 12).

Standardised scales

Group comparisons

A difference between women with PCOS and controls was revealed concerning total sexual function scores (FSFI). The PCOS sample showed significantly lower values (t[40] = − 3.59, p ≤ 0.001, r = 0.49). The comparison of feelings of inadequacy in social situations (FUSS social) also yielded a significant difference (t[43] = 1.80, p = 0.015, r = 0.36) indicating stronger insecurity in women with PCOS. For feelings of inadequacy in sexual situations a clear difference emerged (t[43] = 3.62, p ≤ 0.001, r = 0.48) again showing higher levels of discomfort in women with PCOS. Self-esteem ratings (RSE) were comparable to controls (t[40] = − 0.25, p = 0.805, r = 0.04). The mean depression score (BSI t-score: Mean [SD] = 62.0 [11.71]) almost reached the cut-off value for relevant clinical depression (t-score ≥ 63). Please check Table 2 .

Categorisations

With respect to the FSFI eight women (19.5%) of the PCOS sample were categorised as having “poor” sexual function. As far as feelings of inadequacy in social situations (FUSS social) were concerned n = 11 (25.0%) showed “critical” scores. Results are five times higher than expected in the general population. With regard to feelings of inadequacy in sexual situations (FUSS sexual) the score was “critical” in 8 (18.2%) individuals. This is more than three times the expected rate. Only one person (2.4%) was classified as having critically low self-esteem. The depression scale identified an extraordinarily high number of participants with a clinical depression: n = 24 (54.4%). Please check Table 3 .

Table 3 Psychosexual variables, self-esteem and depression in PCOS: Critical cases

| PCOS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 44 | |||

| Score | Category | n (%) | |

|

1

Full scale scores are “poor” when ≤ 23, as “good” or “satisfactory” when within the range of 24 – 29, and as “very good” when ≥ 30

71

,

72

.

2 High scores indicate high levels of anxiety, z-scores above z = + 1.64 (FUSS social, FUSS sexual) were defined as “critical”, in the general population only 5% of the people would be expected to show scores above this cut-off value. 3 High scores indicate high levels of self-esteem, scores below − 1.64 (RSE) were defined as “critical”, for in the general population only 5% of the people would be expected to show scores below this cut-off value. 4 High scores indicate high levels of depression BSI t-scores ≥ 63 are seen as clinically relevant 69 . | |||

| Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) 1 | |||

| Full-scale score | ≤ 23 | “poor” | 8 (19.5) |

| 24 – 29 | “satisfactory” | 15 (36.6) | |

| ≥ 30 | “good” | 18 (43.9) | |

| missing | n = 3 | ||

| Feelings of Inadequacy in Social and Sexual Situations (FUSS) 2 | |||

| Social insecurity – Scale 1 | ≤ 1.64 | “average” | 33 (75.0) |

| > 1.64 | “critical” | 11 (25.0) | |

| missing | – | ||

| Sexual insecurity – Scale 2 | ≤ 1.64 | “average” | 36 (81.8) |

| > 1.64 | “critical” | 8 (18.2) | |

| missing | – | ||

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE) 3 | |||

| Total Score | < −1.64 | “critical” | 1 (2.4) |

| ≥ −1.64 | “average” | 40 (97.6) | |

| missing | n = 3 | ||

| Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) 4 Depression Scale | |||

| Mean t-score | < 63 | “average” | 20 (45.5) |

| ≥ 63 | “critical” | 24 (54.5) | |

| missing | – | ||

Correlation matrix – standardised measures

Sexual function showed negative correlations with feelings of inadequacy in social and even more so in sexual situations (FSFI & FUSS social: r = − 0.37; FSFI & FUSS sexual: r = − 0.54), whereas the two FUSS scales are highly interrelated (FUSS social & FUSS sexual: r = − 0.75). Sexual function showed a negligible association with depression (FSFI & BSI depression: r = 0.01), but depression was considerably correlated with apprehension in social and sexual situations (BSI depression & FUSS social: r = 0.40; BSI depression & FUSS sexual: r = 0.51) and showed a strong correlation with self-esteem (BSI depression & RSE: r = − 0.63). Hirsutism showed a relevant association with FUSS social (FG & FUSS social: r = 0.31). Body mass index showed a positive medium-size correlation with sexual function (BMI & FSFI: r = 0.32). Age did not reach a medium size correlation with any of the scales, neither did the wish for a child. Please check Table 4 .

Table 4 Correlations.

| FSFI | FUSS social | FUSS sexual | RSE | BSI depression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSFI | – | − 0.367 | − 0.536 | 0.187 | 0.007 |

| FUSS social | – | 0.753 | − 0.393 | 0.398 | |

| FUSS sexual | – | − 0.578 | 0.510 | ||

| RSE | – | − 0.626 | |||

| BSI depression | – | ||||

| Age | 0.038 | − 0.086 | 0.074 | − 0.084 | − 0.139 |

| Body Mass Index | 0.315 | − 0.038 | − 0.110 | − 0.212 | 0.188 |

| Wish for a child | 0.222 | − 0.231 | − 0.184 | − 0.058 | 0.177 |

| Ferriman-Gallwey Score | − 0.177 | 0.308 | 0.288 | − 0.166 | 0.214 |

Content analysis

Of the total number of 44 participants, 24 (54.5%) commented on the question “If you have any of the sexual problems mentioned above, what do you think is/are the reason(s) for it?”. Important themes that arose were related to psychological difficulties, the sexual experience, somatic conditions and partnership. Psychological difficulties such as “Low self-esteem” and “Feeling of being unattractive” were seen in 2 of 24 (8.3%) women, respectively. “General emotional problems” were reported by 3 women (12.5%). The section of Sexual experience yielded the “fear not to get pregnant” as a reason for sexual problems and “insufficient lubrication”: these problems were each reported by 2 of 24 (8.3%) women. Somatic conditions included “hormones” as reasons for sexual dysfunctions in 5 (20.8%) participants. Issues related to “partner and relationship characteristics” were given as reasons by 6 of 24 (25.0%) women in the section of Partnership . Please check Table 5 .

Table 5 Subjective reasons for sexual problems.

| Category | Subcategory | n (%) | Representative quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCOS n = 24* |

|||

| * The n refers to the number of participants who gave an answer to the open question at all. The number serves as the base rate for the percentages given. Each participant could touch on multiple themes in the answer given. | |||

| Psychological difficulties |

|

2 (8.3) | “Low self-confidence” |

|

2 (8.3) | “I am ashamed of the body hair, razor burn” | |

|

1 (4.2) | “Fear that he could find out about the PCOS, especially the body hair”, ”fear of his lack of understanding” | |

|

3 (12.5) | “Psychological difficulties” | |

| Sexual experience |

|

2 (8.3) | “I have the feeling that I wonʼt get pregnant anyway, I think itʼs standing in the way” |

|

2 (8.3) | “Maybe Iʼm not wet enough” | |

| Somatic conditions |

|

5 (20.8) | “I think itʼs due to the anti-baby pill. But I canʼt say for sure” |

|

1 (4.2) | “Because of the PCO Syndrome” | |

|

1 (4.2) | “Health issues” | |

| Partnership |

|

6 (25.0) | “My partner doesnʼt excite me any more” |

|

3 (12.5) | “Different working hours between me and my partner, stress” | |

| Other |

|

2 (8.3) | “I have always had problems, donʼt know it any other way.” |

|

3 (12.5) | “?” | |

Discussion

The presented study assessed sexual quality of life in women with PCOS and was not restricted to sexual functioning. The impact of the diverse factors that were assessed are discussed in the following section.

Sexual functioning and sexual satisfaction

Previous studies have found mixed results regarding sexual functioning. Some authors have reported impairment women with PCOS in certain areas like orgasm completion 32 , genital pain 29 , 35 or sexual desire 30 , 31 , but many studies have not found a significant reduction in overall sexual functioning 24 , 27 , 28 , 32 . Taken together our study showed moderate impairment of sexual functioning. There was no impairment at the level of individual sexual problems according to the list of “sexual problems and dysfunctions”, but the mean FSFI score was significantly lower than that of a comparison group. The group mean of the FSFI score was still within the “satisfactory” range (27.5 [5.33], compare Table 2 ) but 19.5% showed a poor outcome when the scores were categorised (i.e. number of scores below 23). Bearing in mind that sexual dysfunctions are widespread in the population 66 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 further studies are necessary to examine whether PCOS contributes to a higher prevalence of sexual dysfunctions.

This study found moderate sexual satisfaction in PCOS. Regarding sexual satisfaction, our sample with PCOS was less satisfied than a group of women with vaginal agenesis 89 . The results are in line with previous research that indicates a reduced sexual satisfaction in PCOS compared to controls 16 , 24 , 34 , 35 .

Social and sexual insecurity

To our knowledge, this study is the first that examined social and sexual insecurity in PCOS with a detailed questionnaire. The findings showed highly elevated insecurity in the PCOS sample compared to controls and the scores were notably correlated with the degree of body hair. Previous studies indicate that there are several psychological problems associated with hirsutism that can lead to the impairment of sexual well-being 44 . Hirsute women can feel inhibited, ashamed of their body hair and less feminine so that their sexual confidence is compromised 32 , 37 , 54 , 90 . Many hirsute women avoid certain social situations 43 , 47 , and show stronger social fears 45 , 47 . Women with PCOS feel less sexually attractive compared to controls 16 or before antiandrogen treatment 29 . Therefore, the presented results are in line with previous findings uncovering sizable associations between hirsutism and feelings of insecurity. Taking a closer look at the two subscales of feelings of inadequacy in “social” vs. “sexual” situations, our participants with PCOS showed higher anxiety in the social domain. A different picture is seen in women with vaginal agenesis where the bodily condition is not visible to the naked eye. These women report higher distress in sexual compared to social situations 89 . These aspects of sexual quality of life are important to the sexual experience but are an area that remains uncovered when only focussing on sexual dysfunctions.

Self-esteem

Keegan et al. found higher self-esteem in women with PCOS using the RSE, but the sample was skewed towards the better in socio-demographical terms 44 . DeNiet et al. found lower self-esteem using the same scale, yet, a large sample size might have led to a significant result 20 . In this study women with PCOS did not differ from controls regarding RSE results. This contradicts the outcomes of qualitative studies 30 , 37 , 54 . The RSE assesses a global level of self-worth. In order to detect PCOS-related problems, questionnaires might have to be more focussed on specific areas of body image and sexual confidence 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 .

Depression

Depression is an important mediator of sexuality in women. This study found depression in more than half of the women with PCOS (54.5%). High rates have also been reported by other authors 17 , 24 , 36 , 51 , 57 , 91 , but not all 27 . Tan et al. found a rate of about 50% with at least a mild depression 91 , Pastore et al. found 40 – 60% in a PCOS cohort 58 . These numbers are comparable with the result of this study. The point prevalence of depression in Germany is 5.6% 92 . Studies reporting lower levels might be biased in that they excluded participants with any prior psychiatric diagnosis or current use of psychiatric medication 27 , 34 .

The results suggest that enormous rates of depression can be expected in PCOS. Depression can thus be seen as an important contributor to impaired sexual quality of life in PCOS and should also always be considered as a treatment focus apart from gynaecological, endocrinological and sexological care.

Body weight

While the literature presents a clear picture of the inverse relationship between body weight and sexual function 93 , 94 the situation is less clear in women with PCOS 26 , 41 , 42 . For instance, Ferraresi et al. presented a study showing FSFI scores in the low functioning range in obese women without PCOS while women with PCOS showed borderline scores irrespective of weight status 26 . In this study, unexpectedly, a positive correlation between body weight and sexual function was found. As obesity is only one factor that can contribute to the sexual experience it seems that other parameters might be overshadowing body weight effects in PCOS.

Wish for a child

The intensity of the “wish for a child” did not show any substantial correlations with the main outcome measures. This might be an effect of the two roads infertile couples can take: Infertility might put strain on the partnership 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 or lead to an intensified sense of belonging 33 , 91 .

Limitations

The study is based on self-report and did not include expert ratings or physical examinations. Data on hormonal levels would have allowed the authors to gain more insight into the data, yet, as Caruso and colleagues suggested psychological and social factors might indeed be overriding hormonal effects in PCOS 29 . A problem with PCOS is the heterogeneous clinical picture that makes it difficult to attribute research findings to one common feature. In future studies more homogenous subgroups could be selected.

The sample size is rather small and the sampling routes might have caused biased results. Therefore, the results cannot be generalised to the whole population of women with PCOS. The participants were largely informed about the study via fertility clinics which most certainly affects sexual activity and partnership rates 95 . For instance feelings of insecurity and the fear of being rejected might be much more pronounced in samples with lower partnership rates. These fears might even stop women from engaging in social and sexual encounters and lower their chance of positive experiences. Recently, differences in medical (e.g. cycle length) and lifestyle measures have been reported in women with PCOS who had children vs. no children 96 . Depression might exacerbate these difficulties by typical cognitions as a negative view on the self and a pessimistic view on the world. These effects and mutually reinforcing mechanisms should be investigated in further quantitative and qualitative studies.

Some strong points of this study are that the investigation was not confined to the assessment of global scores of sexual function, but especially included the assessment of feelings of inadequacy in social and sexual situations and single sexual problems.

Several standardised scales were included to ensure comparability and correlations between them were analysed to reveal associations. The study was not conducted within a treatment setting, so common social desirability effects could be minimised.

Conclusion

While sexual function per se is only partly impaired, feelings of inadequacy in social and sexual situations are frequent and considerably correlated with the degree of hirsutism in women with PCOS and constitute a major problem in their sexual quality of life. The issue of sexuality should be openly addressed with the patients in order to reduce feelings of shame and inhibition. Unfortunately, sexual counselling is still not a standard procedure in hospital and outpatient care, as special training is needed for doctors and psychologists. If the screening for sexual problems is positive, the patient should be offered to talk to their attending gynaecologist, see a psychologist or be referred to a specialist if problems are severe. A more widespread acknowledgement of the importance of sexual quality of life and the integration of “sexual counselling” into academic curricula might help to improve the treatment situation.

A main issue in women with PCOS is depression. All patients with PCOS should be screened for socio-sexual difficulties and emotional problems. Gynaecologists can ask for problems during the exploration or for instance use short questionnaires for the screening for depression. If the screening is positive patients should be referred to a psychiatrist or psychotherapist.

Interdisciplinary cooperation should be fostered and targeted interventions for the treatment of hirsutism and specialised psychological and sexological counselling should be offered in order to optimise patient care.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants for their time and interest in taking part in the study. The research project was kindly supported by the Else Kröner-Fresenius Stiftung.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Arrington R, Cofrancesco J, Wu A W. Questionnaires to measure sexual quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:1643–1658. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-7625-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mölleken D, Richter-Appelt H, Stodieck S. Influence of personality on sexual quality of life in epilepsy. Epileptic Disord. 2010;12:125–132. doi: 10.1684/epd.2010.0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schönbucher V. Sexuelle Zufriedenheit von Frauen: Psychosoziale Faktoren. Zeitschrift für Sexualforschung. 2007;20:21–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman L A, Berman J, Miles M.Genital self-image as a component of sexual health: Relationship between genital self-image, female sexual function, and quality of life measures J Sex Marital Ther 200329(Suppl.)11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berman L, Windecker M A. The relationship between womenʼs genital self-image and female sexual function: A national survey. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2008;5:199–207. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zielinski R, Miller J, Low K L. The relationship between pelvic organ prolapse, genital body image, and sexual health. Neurol Urodynam. 2012;31:1145–1148. doi: 10.1002/nau.22205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woertman L, van den Brink F. Body image and female sexual functioning and behavior: a review. J Sex Res. 2012;49:184–211. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.658586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmina E, Rosato F, Janni A. Relative prevalence of different androgen excess disorders in 950 women referred because of clinical hyperandrogenism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franks S. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:853–861. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199509283331307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hart R, Hickey M, Franks S. Definitions, prevalence and symptoms of polycystic ovaries and polycystic ovary syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Ob. 2004;18:671–683. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conway G, Dewailly D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E. The polycystic ovary syndrome: A position statement from the European Society of Endocrinology. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;171:P1–P29. doi: 10.1530/EJE-14-0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knochenhauer E S, Key T J, Kahsar-Miller M. Prevalence of the polycystic ovary syndrome in unselected black and white women of the southeastern United States: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:3078–3082. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.9.5090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azziz R, Woods K S, Reyna R. The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2745–2749. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.March W A, Moore V M, Willson K J. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:544–551. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coffey S, Mason H. The effect of polycystic ovary syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2003;17:379–386. doi: 10.1080/09513590312331290268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elsenbruch S, Hahn S, Kowalsky D. Quality of life, psychosocial well-being, and sexual satisfaction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5801–5807. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jauca R, Jäger S, Franke G H. Psychische Belastung, Lebenszufriedenheit und Krankheitsverarbeitung bei Frauen mit dem Polyzystischen Ovarsyndrom (PCOS) Z Med Psychol. 2010;19:38–47. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jedel E, Waern M, Gustafson D. Anxiety and depression symptoms in women with polycystic ovary syndrome compared with controls matched for body mass index. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:450–456. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones G L, Hall J M, Balen A H. Health-related quality of life measurement in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review. Hum Reprod. 2008;14:15–25. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmm030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Niet J E, de Koning C M, Pastoor H. Psychological well-being and sexarche in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:1497–1503. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmid J, Kirchengast S, Vytiska-Binstorfer E. Infertility caused by PCOS – health-related quality of life among Austrian and Moslem immigrant women in Austria. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2251–2257. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trent M E, Rich M, Austin S B. Quality of life in adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome. Arch Pediat Adol Med. 2002;156:556–560. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aloulou J, Halouani N, Charfeddine F. Marital sexual satisfaction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur Psychiat. 2012;27:1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Månsson M, Norström K, Holte J. Sexuality and psychological wellbeing in women with polycystic ovary syndrome compared with healthy controls. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;155:161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drosdzol A, Skrzypulec V, Mazur B. Quality of life and marital sexual satisfaction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Folia Histochem Cyto. 2007;45 01:93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferraresi S R, da Silva Lara L A, Reis R M. Changes in sexual function among women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a pilot study. J Sex Med. 2013;10:467–473. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Battaglia C, Nappi R E, Mancini F. PCOS, sexuality, and clitoral vascularisation: a pilot study. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2886–2894. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veras A B, Bruno R V, de Avila M AP. Sexual dysfunction in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: clinical and hormonal correlations. Compr Psychiat. 2011;52:486–489. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caruso S, Rugolo S, Agnello C. Quality of sexual life in hyperandrogenic women treated with an oral contraceptive containing chlormadinone acetate. J Sex Med. 2009;6:3376–3384. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones G L, Hall J M, Lashen H L. Health-related quality of life among adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2011;40:577–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2011.01279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conaglen H A, Conaglen J V. Sexual desire in women presenting for anti-androgen therapy. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003;29:255–267. doi: 10.1080/00926230390195498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stovall D W, Scriver J L, Clayton A H. Sexual function in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Sex Med. 2012;9:224–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hahn S, Benson S, Elsenbruch S. Metformin treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome improves health-related quality-of-life, emotional distress and sexuality. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:1925–1934. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elsenbruch S, Benson S, Hahn S. Determinants of emotional distress in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:1092–1099. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hahn S, Janssen O E, Tan S. Clinical and psychological correlates of quality of life in polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;153:853–860. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Himelein M J, Thatcher S S. Depression and body image among women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Health Psych. 2006;11:613–625. doi: 10.1177/1359105306065021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kitzinger C, Willmott J. “The thief of womanhood”: womenʼs experience of polycystic ovarian syndrome. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:349–361. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zawadski J, Dunaif A. Boston: Blackwell Scientific; 1992. Diagnostic Criteria for polycystic Ovary Syndrome: towards a rational Approach; pp. 377–384. [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group . Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodman N F, Cobin R H, Futterweit W. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society disease state clinical review: Guide to the best practices in the evaluation and treatment of Polycystic ovary syndrome – part 2. Endoc Pract. 2015;21:1415–1426. doi: 10.4158/EP15748.DSCPT2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albani F, Santamaria V, Tonani S. Sexual function in lean and obese women with policystyc ovarian syndrome (PCOS) J Sex Med. 2009;6:394. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gateva A, Kamenov Z. Sexual function in bulgarian patients with PCOS and/or obesity before and after metformin treatment. J Sex Med. 2011;8:381. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barth J H, Catalan J, Cherry C A. Psychological morbidity in women referred for treatment of hirsutism. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:615–619. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90056-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keegan A, Liao L M, Boyle M. ‘Hirsutism’: a psychological analysis. J Health Psychol. 2003;8:327–345. doi: 10.1177/13591053030083004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sonino N, Fava G A, Mani E. Quality of life of hirsute women. Postgrad Med J. 1993;69:186–189. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.69.809.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dennerstein L, de Senarclens M. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica; 1983. The young woman: psychosomatic aspects of obstetrics and gynaecology. 7th International Congress on Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology; 1983 Sep11–15, Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lipton M G, Sherr L, Elford J. Women living with facial hair: the psychological and behavioral burden. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coëffin-Driol C, Giami A. The impact of infertility and its treatment on sexual life and marital relationships: review of the literature. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2004;32:624–637. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Drosdzol A, Skrzypulec V. Evaluation of marital and sexual interactions of Polish infertile couples. J Sex Med. 2009;6:3335–3346. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tao P, Coates R, Maycock B. The impact of infertility on sexuality: a literature review. Australas Med J. 2011;4:620–627. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.20111055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barnard L, Ferriday D, Guenther N. Quality of life and psychological well being in polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2279–2286. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Larson J H, Anderson S M, Holman T B. A longitudinal study of the effects of premarital communication, relationship stability, and self-esteem on sexual satisfaction in the first year of marriage. J Sex Marital Ther. 1998;24:193–206. doi: 10.1080/00926239808404933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cash T F. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2002. Womenʼs Body Images; pp. 175–194. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Snyder B S. The lived experience of women diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Obst Gyn Neonat Nurs. 2006;35:385–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bancroft J, Loftus J, Long J S. Distress about sex: a national survey of women in heterosexual relationships. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32:193–208. doi: 10.1023/a:1023420431760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Basson R, Leiblum S, Brotto L. Revised definitions of womenʼs sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2004;1:40–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.10107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weiner C L, Primeau M, Ehrmann D A. Androgens and mood dysfunction in women: comparison of women with polycystic ovarian syndrome to healthy controls. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:356–362. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000127871.46309.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pastore L M, Patrie J T, Morris W L. Depression symptoms and body dissatisfaction association among polycystic ovary syndrome women. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71:270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Annagür B B, Tazegül A, Uguz F. Biological correlates of major depression and generalized anxiety disorder in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74:244–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cesta C E, Månsson M, Palm C. Polycystic ovary syndrome and psychiatric disorders: co-morbidity and heritability in a nationwide Swedish cohort. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;73:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.American Psychiatric Association . Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Diagnostic and statistical Manual of mental Disorders. 4th ed., text revision. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schönbucher V, Schweizer K, Rustige L. Sexual quality of life of individuals with 46,XY disorders of sex development. J Sex Med. 2012;9:3154–3170. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schönbucher V, Schweizer K, Richter-Appelt H. Sexual quality of life of individuals with Disorders of Sex Development and a 46,XY karyotype: a review of international research. J Sex Marital Ther. 2010;36:193–215. doi: 10.1080/00926231003719574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schweizer K, Richter-Appelt H. 1. Aufl. Gießen: Psychosozial-Verlag; 2012. Die Hamburger Studie zur Intersexualität; pp. 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rustige L. Hamburg: Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Carl von Ossietzky; 2009. Validierung der Fragebögen zur Zufriedenheit mit den einzelnen Körperteilen (Körperpuppe) und zu sexuellen Schwierigkeiten und Verhaltensweisen (SVS): Erhebung einer Kontrollgruppe zur Erforschung des Körpererlebens und der Sexualität bei erwachsenen intersexuellen Menschen [Dissertation]

- 66.Rosen C B. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gray-Little B, Williams V SL, Hancock T D. An Item Response Theory analysis of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale. Pers Soc Psychol B. 1997;23:443–451. [Google Scholar]

- 68.von Collani G, Herzberg P Y. Eine revidierte Fassung der deutschsprachigen Skala zum Selbstwertgefühl von Rosenberg. Z Diff Diagn Psychol. 2003;24:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Franke G H. Göttingen: Beltz Test; 2000. Brief Symptom Inventory von L. R. Derogatis (Kurzform der SCL-90-R) Deutsche Version-BSI: Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Berner M M, Kriston L, Zahradnik H P. Überprüfung der Gültigkeit und Zuverlässigkeit des deutschen Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI-d) Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2004;64:293–303. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Allen L M, Lucco K L, Brown C M. Psychosexual and functional outcomes after creation of a neovagina with laparoscopic Davydov in patients with vaginal agenesis. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2272–2276. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fedele L, Bianchi S, Frontino G. The laparoscopic Vecchiettiʼs modified technique in Rokitansky syndrome: anatomic, functional, and sexual long-term results. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:3770–3.77E8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.10.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fahrner E M. Selbstunsicherheit bei Patienten mit funktionellen Sexualstörungen: Ein Fragebogen zur Diagnostik. Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft fuer praktische Sexualmedizin. 1984;4:15–16. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rosenberg M. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1965. The Measurement of Self-esteem; pp. 16–36. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Blascovich J, Tomaka J. San Diego: Academic Press, Elsevier Science; 1991. Measures of Self-esteem; pp. 115–160. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roth M, Decker O, Herzberg P Y. Dimensionality and norms of the Rosenberg Self-esteem scale in a German general population sample. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2008;24:190–197. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Martín Albo L, Núňez J L, Navarro J G. The Rosenberg Self-esteem scale. Span J Psychol. 2007;10:458–467. doi: 10.1017/s1138741600006727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Derogatis L R, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hatch R, Rosenfield R L, Kim M H. Hirsutism: implications, etiology, and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;140:815–830. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(81)90746-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ferriman D, Gallwey J D. Clinical assessment of body hair growth in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1961;21:1440–1447. doi: 10.1210/jcem-21-11-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Azziz R, Carmina E, Sawaya M E. Idiopathic Hirsutism. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:347–362. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.4.0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D. The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: the complete task force report. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:456–488. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Field A.Discovering Statistics using SPSS 3rd ed.ed.London: Sage Publications; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mayring P. München: Psychologische Verlagsunion; 1990. Einführung in die qualitative Sozialforschung. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Anastasiadis A G, Davis A R, Ghafar M A. The epidemiology and definition of female sexual disorders. World J Urol. 2002;20:74–78. doi: 10.1007/s00345-002-0272-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Domoney C. Sexual function in women: what is normal? Int Urogynecol J. 2009;20:9–17. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0841-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Laumann E O, Paik A, Rosen R C. Sexual dysfunction in the United States prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281:537–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nicolosi A, Laumann E O, Glasser D B. Sexual behavior and sexual dysfunctions after age 40: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Urology. 2004;64:991–997. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fliegner M, Krupp K, Brunner F. Sexual Life and Sexual Wellness in Individuals with Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (CAIS) and Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser Syndrome (MRKHS) J Sex Med. 2014;11:729–742. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Krupp K, Brunner F, Fliegner M. Fragebogen zum Erleben der eigenen Weiblichkeit (FB-W): Ergebnisse von Frauen mit Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser Syndrom und Frauen mit polyzystischem Ovarsyndrom. Psychother Psych Med. 2013;63:334–340. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1333286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tan S, Hahn S, Benson S. Psychological implications of infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:2064–2071. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jacobi F, Klose M, Wittchen H U. Psychische Störungen in der deutschen Allgemeinbevölkerung: Inanspruchnahme von Gesundheitsleistungen und Ausfalltage. Bundesgesundheitsbl – Gesundheitsforsch – Gesundheitsschutz. 2004;47:736–744. doi: 10.1007/s00103-004-0885-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kocełak P, Chudek J, Naworska B. Psychological disturbances and quality of life in obese and infertile women and men. Int J Endocrinol. 2012;2012:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2012/236217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kolotkin R L, Zunker C, Østbye T. Sexual functioning and obesity: a review. Obesity. 2012;20:2325–2333. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wischmann T, Schilling K, Toth B. Sexuality, self-esteem and partnership quality in infertile women and men. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2014;74:759–763. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1368461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stassek J, Ohnolz F, Hanusch Y. Do pregnancy and parenthood affect the course of PCO Syndrome? Initial results from the LIPCOS study (Lifestyle Intervention for Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome [PCOS]) Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2015;75:1153–1160. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1558186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]