Abstract

Background-

To improve the quality of care for children with sickle cell anemia (SCA) in Kano, Nigeria, we initiated a standard care protocol in 2014 to manage children with strokes at Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital.

Method-

The standard care protocol requires that children presenting with acute strokes be treated with hydroxyurea at a fixed dose of 20 mg/kg/day within 2 months of the stroke.

Results-

We identified 29 children with SCA who had an initial stroke within the study period, followed for a mean of 1.25 years (to either end of follow up or a second stroke) and corresponding to an initial stroke incidence rate of 0.88 per 100 patient-years. Six children had stroke recurrence while on hydroxyurea, with a stroke recurrence rate of 17.4 events per 100 patient-years, and one child died. None of the children treated with hydroxyurea had therapy held because of myelosuppression; although, adherence was approximately 60%, in part because families had to pay for hydroxyurea. Most likely, we underestimated the incidence of strokes because despite formal training for stroke detection during the quality improvement period, no participant had formal assessment using the pediatric stroke scale.

Conclusion-

Our results provide strong evidence for the high prevalence of initial strokes in children with SCA in a low-resource setting, requirement for ongoing training to detect strokes with an objective stroke assessment, and the need for government support free access to hydroxyurea.

Keywords: Sickle cell disease, stroke, stroke recurrence, mortality, hydroxyurea

Introduction

Each year about 300,000 children are born with sickle cell disease (SCD) worldwide, with nearly two-thirds of the births occurring in Africa.1 In a recent survey, we demonstrated Kano, in northern Nigeria, has the highest number of children with SCD in Nigeria, with Murtala Mohammed Specialist Hospital in Kano having about 10,000 children registered at the pediatric SCD clinic.2 In contrast to high-income countries, SCD-related childhood mortality in sub-Saharan African countries such as Nigeria remains high at 50–90%,3 with fewer than half of the children reaching their 5th birthday.3

Stroke is one of the most important causes of mortality in children with SCD.4 Without transcranial doppler ultrasound (TCD) screening and regular blood transfusion therapy for those with abnormal TCD measurement, approximately 10% of the children with sickle cell anemia (SCA) defined as phenotype hemoglobin (Hb) SS or HB Sβ0 thalassemia, not screened for abnormal TCD measurements nor treated with regular blood transfusion therapy, will develop strokes. Among untreated children with strokes, at least 50% experience a second stroke after 2 years,4 with a mortality rate of 20–30%.4 Due to this high rate of stroke recurrence and the absence of regular blood transfusion therapy as a viable option in Nigeria as a result of poor availability of blood, poor parental acceptance of blood transfusion and cost, hydroxyurea therapy is the only viable option for the majority of children.5 Preliminary data supporting the potential use of hydroxyurea therapy for secondary stroke prevention in children with SCD in sub-Saharan Africa is based on a meta-analysis our team conducted. The expected incidence rates of stroke recurrence while on regular blood transfusion therapy, hydroxyurea therapy, or no therapy were found to be 1.9 (95% CI 0.1.0, 2.9), 3.8 (95% CI 1.9 to 5.7), and 29.1 (95% CI 19.2, 38.9) events per 100 patient-years, respectively.6 This meta-analysis clearly demonstrates that hydroxyurea therapy is significantly better for secondary stroke prevention than no therapy, which is the current standard of care in most sub-Saharan countries, and in the northern Nigeria region. However, the benefits and risks of hydroxyurea therapy for secondary stroke prevention are poorly defined in Nigeria.

Since 2014, based on the evidence that hydroxyurea therapy has some benefit in secondary stroke prevention,6 the hematology team at Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital (AKTH) in Kano, Nigeria elected to introduce a uniform strategy for secondary stroke prevention as part of a quality improvement program. We introduced hydroxyurea therapy as standard care for all children with SCA and prior strokes. We report the results of this quality improvement strategy for secondary stroke prevention in a low-resource setting.

Methodology-

The study was conducted at the pediatric SCD clinic of AKTH located in Kano, northern Nigeria. Approximately 1100 children are seen annually at the pediatric SCD clinic. The clinic runs weekly, with about 80 children seen each clinic day. Approval to conduct the study was received from the ethics committees of AKTH and Vanderbilt University Medical Center. A standard care protocol for secondary stroke prevention was created, reviewed, and initiated for all children with SCA and new strokes from January of 2014 through July of 2017. As part of our inclusion criteria, we reviewed all medical charts of children with strokes and SCA (HbSS and HbSβ0 thalassemia) identified through SCD clinic, and retrieved all eligible files. Data extracted for each child included age at time of first stroke, date of birth, sex, parental income, parental education, weight, height, date of first stroke, number of strokes, side of stroke, any secondary stroke prevention strategy (blood transfusion or hydroxyurea therapy), history of recurrence, number of recurrent strokes, year of each recurrence, side of recurrence, date of last visit, patient status at the time of review, modified Rankin Scale7 (mRS) and the gross motor classification system8 scored from the most recent clinic visit, complete blood count result at first visit and at most recent clinic visit. Hydroxyurea therapy was prescribed upon diagnosis of a stroke, a fixed dose of 20 mg/kg/day. All hydroxyurea prescriptions were self-pay because there is no public health insurance to cover the expenses of hydroxyurea.

Prior to initiating the protocol, multiple members of the pediatric care team received training on conducting the Pediatric National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (PedNIHSS) (https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/toolkit_content/PDF/PX820802.pdf).9,10 All data were entered into an electronic database and reviewed by a second assistant to ensure accuracy.

Statistical analysis-

We summarized study variables using the median and interquartile range for continuous data and percentages for categorical data. We assessed stroke prevalence using proportions. We assessed mortality and stroke recurrence using rates and percentages. Comparisons of the pretreatment laboratory values for mean cell volume (MCV) and values at 12 months after starting hydroxyurea therapy for patients on hydroxyurea were conducted to determine the differential change from baseline and thus adherence. A p-value <0.05 was taken as statistically significant. All analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 25).

Results-

Demographics-

Based on World Health Organization criteria and a standardized neurological examination,10 a total of 29 children with SCA were diagnosed with a stroke during the sampling frame. The median age at the time of first stroke was 6.0 years (range 1.1 to 14.2 years), with 62.1% males. The median hemoglobin level at the time of stroke was 8.2 g/dl. After implementing, as standard care in the clinic, a fixed dose of ~ 20 mg/kg/day of hydroxyurea therapy for secondary stroke prevention, 93.1% (27 of 29) were started on hydroxyurea therapy within two months of the first stroke.

Nigerian children with SCA experience a high rate of stroke and stroke recurrence

A total of 2.6% (29 of 1100) children with SCA had an initial stroke within the study period, with 27.6% (8 of 29) having at least one recurrent stroke within 3.3 years of the first stroke. The median time to recurrence was 0.35 years with 75% (6 of 8) of the recurrences within the first 6 months, (Figure 2) and the earliest stroke occurring within 2 months of the first stroke, Figure 1. The rate of initial stroke in the pediatric SCD clinic population (birth through 12 years-of-age) was 0.88 per 100 patient-years (95% confidence interval 0.60 to 1.25 per 100 patient-years). Children with initial strokes were followed for a total of 36.4 years to the end of follow-up or a second stroke, and had a rate of recurrence of 22.0 events per 100 patient-years (95% confidence interval 10.2 – 41.8 per 100 patient-years). The rate of recurrence for children who followed the protocol of starting hydroxyurea therapy within 2 months of the initial stroke (27 of 29) was lower, at 17.4 events per 100 patient-years (95% confidence interval 7.1 – 36.3 events per 100 patient-years).

Figure 2-.

Time to second stroke showing 75% of children having stroke recurrence within 6 months of the first stroke.

Figure 1: Kaplan-Meier plot of time to stroke recurrence after first stroke (n=29).

High mortality rate associated with strokes

We recorded two deaths out of the 29 children for an overall mortality rate of 4.0 events per 100 patient-years (95% CI 0.7 – 13.3 events per 100 patient-years). Both children were on hydroxyurea therapy for secondary stroke prevention. The mortality rate for the 27 children on hydroxyurea per protocol was 4.3 events per 100 patient years (95% CI 0.7 – 14.3 events per 100 patient years). Death was unrelated to any evidence of myelosuppression. The first child that died had stroke at the age of 6 years and had 3 recurrent strokes within 2 years of the initial stroke, while the second child had one stroke at the age of 11 years. The mortality rate from first stroke to endpoint (second stroke, death, or endpoint) was 2.75 events per 100 patient-years (1 death in 36.4 cumulative patient-years), 95% CI 0.04 to 15.30 per 100 patient-years. The mortality rate from second stroke to endpoint or death was 7.41 per 100 patient-years (1 death in 13.5 cumulative patient years) with a 95% CI (0.10 to 41.24 per 100 patient-years).

Children receiving fixed moderate dose of hydroxyurea with SCA do not experience increased toxicity associated with hydroxyurea therapy for secondary stroke prevention

Of the 29 children with an initial stroke, 65.5% received an initial exchange transfusion. Transfusion therapy was not continued at regular intervals due to barriers due to either poor availability of blood, poor parental acceptance of blood transfusion or cost. For secondary prevention of strokes, 93.1% (27) were either already on hydroxyurea (n=1) or started on a fixed dose of hydroxyurea (n=26), 20 mg/kg/day, within 2 months of the stroke, as part of standard care. None of the children treated with hydroxyurea had therapy held because of myelosuppression or anemia.

Adherence to hydroxyurea therapy for secondary prevention of strokes was assessed in 21 of the 27 children who began hydroxyurea within 2 months. As an indirect measure of adherence, 61.9% (13/21) of patients had an increase in MCV by at least 10.0 femtoliter (fl), with the mean MCV increasing from 86.2fl at baseline to 101.3fl at 24 months. Mean last MCV was 111.3fl and 98.2fl in those with and without recurrence, respectively (p=0.035). However, adherence (MVC ≥ 10.0fl) was not different by recurrence (56.3% in those without recurrence, 80.0% in those with recurrence, p=0.61). Unlike in a clinical trial, no specific strategy was used to reinforce adherence to hydroxyurea and hydroxyurea therapy was not as a trial therapy.

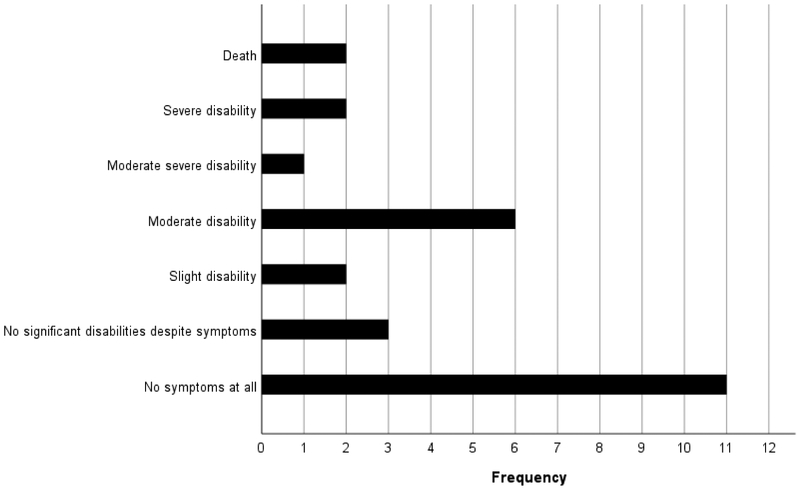

The Modified Rankin scale shows a wide degree of neurologic disability following stroke in children with SCA

The median modified Rankin Score was assessed in 93% (27/29) children with strokes. the median modified Rankin Score was 1, range from 0 to 6. Classifying the modified Rankin Score as either no or slight disability, or moderate disability or worse, 26.3% (5/19) of those without recurrence had moderate or greater disability compared to 75.0% (6/8) of those with recurrence (p=0.33). On the gross motor function classification system 34.0% (10/25) had normal function and 21.0% (6/25) had level 3 or higher. Both measurements were completed at a median of 1.6 years (IQR 1.9 years) after the initial stroke, Table I. Despite the medical staff being trained on the Pediatric National Institute of Health Stroke Scale prior to the beginning of the quality improvement project, no participants presenting with acute stroke symptoms were evaluated with the stroke scale. We did not identify this gap in assessment until completion of the quality improvement project.

Table I:

Demographics of the cohort stratified by occurrence of a second stroke (n=29)

| Variables | No second stroke (n=21) | Second stroke (n=8) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, Male (%) | 57.1 | 75.0 | 0.671# |

| Age at start of follow-up, median (IQR) | 4.7 (6.6) | 4.1 (2.4) | 0.922* |

| Age at first stroke, median (IQR) | 6.5 (7.3) | 5.1 (3.3) | 0.495* |

| Hydroxyurea use within two months of first stroke (%) | 100.0 | 75.0 | 0.069# |

| Modified Rankin scale - moderate or severe disability (n=27) | 26.3 | 75.0 | 0.033# |

| GMFCS‡ (Level 0 - normal functioning) (n=25) | 50.0 | 14.3 | 0.179 |

| Death (%) | 4.8 | 12.5 | 0.483# |

Fisher’s exact test

Mann-Whitney test

Gross Motor Function Classification System

Discussion

Despite the high prevalence of SCD in Nigeria and other sub-Saharan African countries, no standard strategy has been endorsed for secondary prevention of strokes. Using an accepted strategy for secondary stroke prevention, in 2014, we introduced a uniform protocol for secondary stroke prevention in our tertiary care hospital and collected information describing our quality improvement program. The reported rate of initial stroke for our study was 0.88 events per 100 patient-years which is similar to the expected incidence rate of 0.76 in children below 20 years4, living in the United States in the era before primary stroke prevention with annual surveillance for abnormal TCD measurements, coupled with regular blood transfusion therapy. The recurrence rate of stroke while on hydroxyurea was 17.4 events per 100 patient-years, which falls below the expected rate of 29.1 in patients without any treatment.4,6

In our study, the majority (75%) of the stroke recurrences occurred within 6 months of the initial stroke. These findings are similar to prior evidence in children with SCD that highest incidence of stroke recurrence occurred within 24 months of the initial stroke for both individuals not receiving blood transfusion therapy,4 and for those that do receive blood transfusion11.

At least two reasons, independently or together, may explain a higher rate of stroke recurrence after treatment with fixed moderate dose of hydroxyurea, 17.4 versus an expected 3.8 events per 100 patients from a pooled analysis. First, all expenses associated with hydroxyurea including the cost of the therapy and the cost of laboratory surveillance must be paid for out of pocket. As shown in a recent study in Benin, Nigeria, another state without government supported public health insurance, 16% (4 of 24) adults were compliant with hydroxyurea therapy. Major reasons for non-compliance were lack of funds and poor knowledge of adults with SCA regarding stroke prevention.12 In our feasibility trial for primary stroke prevention in Nigerian children with SCA, which provided both free hydroxyurea, and free laboratory evaluation, none of the scheduled monthly visits (603 visits), were missed and approximately 85% of the participants increased their MCV to above 10 fl from baseline suggesting good compliance with hydroxyurea.5 The results of the current study demonstrate a poor adherence rate of only approximately 60% when the hydroyxurea therapy was self-pay. A second explanation for the lower than expected benefit for secondary stroke prevention is that the dose of 20 mg/kg/day may be too low to prevent stroke recurrence.

None of the children in this cohort had myelosuppression as a result of hydroxyurea using a fixed moderate dose of 20 mg/kg/day suggesting laboratory monitoring for myelosuppression is not required, which may help to reduce the financial burden these families experience. The absence of toxicity associated with a fixed dose of hydroyxurea is similar to our earlier findings in the primary stroke feasibility trial in the same region, demonstrating no significant toxicity associated with fixed dose of 20 mg/kg/day of hydroxyurea therapy.5 In a low-resource setting, the absence of myelosuppression is critically important because laboratory surveillance costs are typically paid for out-of-pocket. In this region, the mean monthly income is the equivalent of $130. A complete blood cell count is approximately $5.00, too expensive for many families to afford on a regular basis. Thus, the maximum tolerated dose of hydroxyurea with monitoring for myelosuppression that is often utilized high income countries is perhaps too costly when combining the potential small incremental clinical benefit, plus the added burden of frequent laboratory monitoring. There is evidence that moderate dose hydroxyurea (20 mg/kg/day) has clinical benefit in decreasing acute vaso-occlusive pain events and lowers TCD velocities.5,13,14 Baby HUG data also demonstrated that infants and young children on hydroxyurea therapy at a fixed dose of 20 mg/kg/day had no increased adverse events when compared to children not receiving any therapy.14

As part of the standard of care assessment, we asked the pediatric staff specifically trained in the Pediatric National Institute of Health Stroke Scale, to assess each suspected acute stroke in a child with SCA. However, no acute assessment with the scale was performed. The absence of any assessment of the Pediatric Stroke Scale is most likely reflects a lack of perceived lack clinical utility for the scale. Improvement in the acute care assessment of children with strokes represents an opportunity for improvement in the next cycle of quality improvement for stroke detection and management.

We were able to retrospectively record the modified Rankin scale on 55% (16/29) children who had a stroke via parental interview and examination of the child to determine the degree of neurological disability following the stroke. Six patients (24%) had moderate to severe disability requiring assistance in walking and other daily activities including dressing, eating and toileting. A total of 10 patients had complete recovery (34%) from stroke. In a previous retrospective study in Ibadan, Nigeria, of 39 children who had stroke between 1998 and 2002, only 15% (6 of 39) had complete recovery, with majority of the children having mild to moderate disability requiring assistance with daily activities.15 This degree of disability is similar to the findings by Njamnshi et al in Cameroun, who showed high stroke severity among patients with SCD due to lack of standardized care for managing SCD patients with stroke.16

The stroke mortality rate of 4.3 per 100 patient-years for patients on hydroxyurea is similar to our previous findings in the primary stroke prevention (SPIN) in Nigerian children with SCA trial. In the prior trial conducted in the same region, mortality rate for children treated with hydroxyurea for primary stroke prevention was 2.69 per 100 patient-years and 1.81 per 100 patient years in the comparison group of children without hydroxyurea therapy.17 Similarly Makani et al. found a mortality rate of 1.9 per 100 person-years in the general population of children with SCD in Tanzania.18 Mortality rates in high-income countries are at least 10 times lower, approximately, 0.15 per 100 person-years in the United Kingdom and 0.6 per 100 person years in the USA.19,20 Preliminary data suggest that death rate after a second stroke was much higher than expected, but these data are limited because of the low number of deaths following the second stroke (n=1) and the short follow up period (~ 1.3 years).

As expected in a quality improvement project, our study has inherent limitations. As data were collected from clinical records, we included and analyze only data captured and available in the clinical records. Additionally, the clinical records were only paper-based with no electronic database. Consequently, we may have underestimated the number of strokes and deaths that occurred at home or at other hospitals outside our study site.

Given the high prevalence of strokes in unscreened and untreated children with SCA, primary and secondary stroke prevention program are a public urgency in children with SCA living in Nigeria. Hydroxyurea may be a reasonable option for secondary stroke prevention; however, without a government policy to provide hydroxyurea therapy and laboratory surveillance for toxicity, strategies are not likely to be effective in low-resource settings. Further, the optimal dose of hydroxyurea still needs to be elucidated for low-resource settings.

As the local expertise for detecting stroke has continued to grow at multiple institutions in the region, so has the number of children with SCD identified with stroke. Since closing of the standard care protocol in July of 2017 at AKTH, and creating stroke care teams at the other two hospitals in Kano, Nigeria, Murtala Mohammed Specialist Hospital (start date August 2017) and Hasiya Bayero Pediatric Hospital (start date November of 2017), we have identified an additional, 7, 29 and 20 strokes, respectively in children for a total of 56 in Kano, Nigeria. All children have been prescribed hydroxyurea at fixed dose of 20 mg/kg/day. Without a comprehensive public health strategy with a partnership including the state health department, the full benefit of primary and secondary prevention strategies will fall short of their potential.

Figure 3: Modified Rankin Scale for Children with Stroke.

The bar graph shows the frequency of modified Rankin scale scores for n=29 Nigerian children with sickle cell disease.

Acknowledgement

This article was supported by the Sickle cell disease Stroke PRevention In NiGeria (SPRING) TRIAL (NCT02560935) (R01NS09404–04) and the Moderate dose hydroxyurea for Secondary Stroke Prevention in Children With Sickle cell disease in sub-Saharan Africa (SPRINT) Trial (NCT02675790).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Piel FB, Patil AP, Howes RE, et al. Global epidemiology of sickle haemoglobin in neonates: a contemporary geostatistical model-based map and population estimates. Lancet 2013;381:142–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galadanci N, Wudil BJ, Balogun TM, et al. Current sickle cell disease management practices in Nigeria. International health 2014;6:23–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grosse SD, Odame I, Atrash HK, Amendah DD, Piel FB, Williams TN. Sickle cell disease in Africa: a neglected cause of early childhood mortality. Am J Prev Med 2011;41:S398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powars D, Wilson B, Imbus C, Pegelow C, Allen J. The natural history of stroke in sickle cell disease. The American journal of medicine 1978;65:461–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galadanci N, Abdullahi SU, Vance LD, et al. Feasibility Trial for Primary Stroke Prevention in Children with Sickle Cell Anemia in Nigeria (SPIN Trial). American journal of hematology 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kassim AA, Galadanci NA, Pruthi S, DeBaun MR. How I treat and manage strokes in sickle cell disease. Blood 2015;125:3401–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goeggel Simonetti B, Cavelti A, Arnold M, et al. Long-term outcome after arterial ischemic stroke in children and young adults. Neurology 2015;84:1941–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Developmental medicine and child neurology 1997;39:214–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ichord RN, Bastian R, Abraham L, et al. Interrater reliability of the Pediatric National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (PedNIHSS) in a multicenter study. Stroke 2011;42:613–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beslow LA, Kasner SE, Smith SE, et al. Concurrent validity and reliability of retrospective scoring of the Pediatric National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. Stroke 2012;43:341–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scothorn DJ, Price C, Schwartz D, et al. Risk of recurrent stroke in children with sickle cell disease receiving blood transfusion therapy for at least five years after initial stroke. The Journal of pediatrics 2002;140:348–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adewoyin AS, Oghuvwu OS, Awodu OA. Hydroxyurea therapy in adult Nigerian sickle cell disease: a monocentric survey on pattern of use, clinical effects and patient’s compliance. African health sciences 2017;17:255–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott JP, Hillery CA, Brown ER, Misiewicz V, Labotka RJ. Hydroxyurea therapy in children severely affected with sickle cell disease. The Journal of pediatrics 1996;128:820–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang WC, Ware RE, Miller ST, et al. Hydroxycarbamide in very young children with sickle-cell anaemia: a multicentre, randomised, controlled trial (BABY HUG). Lancet 2011;377:1663–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fatunde OJ, Adamson FG, Ogunseyinde O, Sodeinde O, Familusi JB. Stroke in Nigerian children with sickle cell disease. African journal of medicine and medical sciences 2005;34:157–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Njamnshi AK, Mbong EN, Wonkam A, et al. The epidemiology of stroke in sickle cell patients in Yaounde, Cameroon. Journal of the neurological sciences 2006;250:79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galadanci NA, Umar Abdullahi S, Vance LD, et al. Feasibility trial for primary stroke prevention in children with sickle cell anemia in Nigeria (SPIN trial). American journal of hematology 2017;92:780–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makani J, Soka D, Rwezaula S, et al. Health policy for sickle cell disease in Africa: experience from Tanzania on interventions to reduce under-five mortality. Tropical medicine & international health : TM & IH 2015;20:184–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 2010;115:3447–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Telfer P, Coen P, Chakravorty S, et al. Clinical outcomes in children with sickle cell disease living in England: a neonatal cohort in East London. Haematologica 2007;92:905–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]