Abstract

Ustilago segetum (Pers.) Roussel tritici (UST) causes loose smut of wheat account for considerable grain yield losses globally. For effective management, knowledge of its genetic variability and population structure is a prerequisite. In this study, UST isolates sampled from four different wheat growing zones of India were analyzed using the second largest subunit of the RNA polymerase II (RPB2) and a set of sixteen neutral simple sequence repeats (SSRs) markers. Among the 112 UST isolates genotyped, 98 haplotypes were identified. All the isolates were categorized into two groups (K = 2), each consisting of isolates from different sampling sites, on the basis of unweighted paired-grouping method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA) and the Bayesian analysis of population structure. The positive and significant index of association (IA = 1.169) and standardized index of association (rBarD = 0.075) indicate population is of non-random mating type. Analysis of molecular variance showed that the highest variance component is among isolates (91%), with significantly low genetic differentiation variation among regions (8%) (Fst = 0.012). Recombination (Rm = 0) was not detected. The results showed that UST isolates have a clonal genetic structure with limited genetic differentiation and human arbitrated gene flow and mutations are the prime evolutionary processes determining its genetic structure. These findings will be helpful in devising management strategy especially for selection and breeding of resistant wheat cultivars.

Keywords: genetic diversity, gene flow, haplotype, mutation, population structure

Introduction

Loose smut caused by the basidiomycete fungus Ustilago segetum (Pers.) Roussel tritici Jensen (UST), is one of the most serious diseases on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) globally. The disease is favored by moist and cool climate during anthesis (Quijano et al., 2016). This fungus converts the spike floral tissues to fungal teliospores, causing yield losses equivalent to the percent smutted spikes (Green et al., 1968; Singh, 2018). The primary inoculum of the pathogen survives in the embryo of the wheat seeds (Kassa et al., 2015). Wilcoxon and Saari (1996) documented that the fungus can result in reductions of 5–20 per cent profit at an infection level of 1–2 per cent. Similarly, Nielsen and Thomas (1996) reported 15–30% annual yield losses as a result of UST infection. Joshi et al. (1980) reported loose smut incidence up to 10% in North Western parts of India. Besides India, 5–10% loose smut incidence was also reported from Russia, New Zealand, and USA (Thomas, 1925; Bonne, 1941; Atkins et al., 1943; Watts Padwick, 1948; Menzies et al., 2009; Kaur et al., 2014).

The infection process and disease cycle of UST on wheat has been elaborately discussed by several workers (Wilcoxon and Saari, 1996; Ram and Singh, 2004). Dikaryotic spores of UST disembarked on the wheat floret, germinate and penetrate the ovary through feathery stigma during anthesis (Dean, 1964; Shinohara, 1976). Mycelia of UST stay alive within the embryo of infected seeds and move systemically through the growing point of the tillers without showing any visible symptoms (Kumar et al., 2018). The symptoms become visible on emergence of spikes from the boot. Several methods are available to manage loose smut that include use of disease free seed, seed treatment with hot water or systemic fungicides, and host resistance are highly effective in controlling loose smut of wheat (Jones, 1999; Bailey et al., 2003; Knox et al., 2014). Unfortunately, the high genetic variability in the pathogen population may develop strains resistant to fungicides and also reduces lifespan of the resistant varieties (Randhawa et al., 2009). Therefore, the understanding of the variability and mechanism causing variability in the pathogen population is important for framing effective disease management and resistance breeding strategies.

Traditionally, variations in fungal pathogens have been deciphered on the basis of morphology, cultural characters, physicochemical characters, virulence pattern, mating type, and disease reaction on differential hosts (Kaur et al., 2014; Kashyap et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2016). Unfortunately, these methods are time consuming, highly influenced by environment and thus are not very precise. Recently, DNA profiling based on restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) and inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) are being extensively employed to study the population biology and genetic diversity among fungi (Bennett et al., 2005; Kashyap et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2016). Karwasra et al. (2002) used RAPD, ISSR, and AFLP profiling for assessing the extent of genetic variation among the regional UST isolates collected from Haryana, India. SSR or microsatellites markers have an advantage in studying genetic diversity, population genetic structure, genetic linkage mapping, and quantitative trait locus (QTL) because of its high repeatability, transferability, co-dominance, and ubiquitous presence (Ellegren, 2004; Kumar et al., 2013a; Singh et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2016). Recently, SSR has been used for deciphering diversity in many fungal plant pathogens, such as Puccinia triticina (Wang et al., 2009), Magnaporthe grisea (Shen et al., 2004), Rhynchosporium secalis (Bouajila et al., 2007), Phytophthora infestans (Zhao et al., 2008), Phaeosphaeria nodorum (Sommerhalder et al., 2010), Fusarium culmorum (Pouzeshimiab et al., 2014), Ustilago hordei (Yu et al., 2016), Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici (Prasad et al., 2018), and Bipolaris oryzae (Ahmadpour et al., 2018). Storch et al. (2007) reported that protein-coded genes are generally more conserved and can be aligned with more reliability. Among protein-coding markers, second-largest subunit of nuclear RNA polymerase II (RPB2), translation elongation factor 1-alpha (Tef1), beta-tubulin (Tub2) and actin (ACT) have been most frequently used for inferring phylogenetic relationships among fungi (Stielow et al., 2015; Raja et al., 2017). Functionally, RPB2 gene is responsible for the transcription of protein-encoding genes (Sawadogo and Sentenac, 1990) and present as single-copy in all eukaryotes (Thuriaux and Sentenac, 1992). A high level of polymorphisms in this gene makes this an excellent tool to study molecular evolution and phylogenetic relationships (Matheny et al., 2007; Krimitzas et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2016; Kruse et al., 2017). Stockinger et al. (2014) reported RPB2 gene as a potential marker for adequate phylogenetic resolution to resolve fungal lineages when compared to rDNA loci. Therefore, in the present study phylogenetic analysis of the single copy of RPB2 gene was done to explore genetic differentiation of UST populations. Despite recent advances, the role of gene flow in the reproduction, dispersal and evolution of UST populations is still poorly studied. To the best of our knowledge, fingerprinting and genetic diversity in UST population using microsatellite markers have not been studied extensively on large number of UST isolates. Thus, the present investigation was undertaken to study the genetic variation in the UST isolates collected from four different agro-ecological zones of India. The specific objectives of present investigation were to: (i) analyze the genetic diversity of UST isolates of Indian origin based on geographic areas of collection by microsatellites and RPB2 gene sequence comparison (ii) investigate the possibility of random mating within their sampling sites using MULTILOCUS version 1.31 (Agapow and Burt, 2001) and (iii) determine the population genetic structure of the UST population in four different wheat growing zones by employing genetic data analysis tools like GenAlEx 6.5 (Peakall and Smouse, 2012), NTSYS-pc program V2.1 (Rohlf, 2002), DnaSP program (Tajima, 1983), STRUCTURE 2.3.4 (Pritchard et al., 2000), and Bottleneck v1.2 (Agapow and Burt, 2001).

Materials and Methods

Sampling, Isolation and Purification of Fungal Isolates

One hundred and twelve isolates of UST were collected from different agro-ecological zones of India during 2016–2018 (Table 1, Figure S1). Stratified random sampling method was adopted at spike emergence to anthesis stage at least 30 KM apart, in each field. One smutted spike was gathered per field to avoid the possibility of mixture of genotypes. Isolates were assigned into four populations and named as Central zone (CZ), North Eastern Plain Zone (NEPZ), North Hill Zone (NHZ), and North Western Plain Zone (NWPZ). Single-teliospore cultures were obtained by inoculating teliospores on half-strength potato dextrose agar (50% PDA) and incubated at 25 ± 1°C for 24 h. Single germinating teliospores were transferred to slants containing 50% PDA, incubated at 25 ± 1°C and maintained at 4°C for further use.

Table 1.

Sampling details of Ustilago segetum tritici (UST) isolates used in the study.

| S.N. | Isolate code | Region/State | Zone | Latitude (N) | Longitude (E) | UTM (E) | UTM (N) | HG | HC | NCBI accession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WLS17-PUN-1 | Yodhapur, Punjab | NWPZ | 30.084 | 76.573 | 651593.80 | 3329136.60 | 52 | 1 | MH160206 |

| 2 | WLS17-PUN-2 | Mirapur, Punjab | NWPZ | 30.200 | 76.492 | 643618.00 | 3341932.40 | 1 | 2 | MH160207 |

| 3 | WLS17-HR-3 | Taprapur, Haryana | NWPZ | 30.267 | 77.152 | 707042.00 | 3350276.80 | 53 | 3 | MH160208 |

| 4 | WLS17-HR-4 | Gagsina, Haryana | NWPZ | 29.568 | 76.886 | 682707.80 | 3272403.20 | 54 | 1 | MH160209 |

| 5 | WLS17-HR-5 | Samora, Haryana | NWPZ | 29.816 | 77.006 | 693861.70 | 3300051.80 | 55 | 3 | MH160210 |

| 6 | WLS17-HR-6 | Indri, Haryana | NWPZ | 29.951 | 77.048 | 697648.50 | 3315152.90 | 56 | 1 | MH160211 |

| 7 | WLS17-HR-7 | Stondi, Haryana | NWPZ | 29.570 | 76.895 | 683555.80 | 3272583.30 | 57 | 1 | MH160212 |

| 8 | WLS15-WB-8 | Karimpur, West Bengal | NEPZ | 23.545 | 88.539 | 657067.90 | 2604691.20 | 12 | 1 | MH160213 |

| 9 | WLS17-HR-9 | Gagsina, Haryana | NWPZ | 29.568 | 76.886 | 682707.80 | 3272403.20 | 58 | 1 | MH160214 |

| 10 | WLS16-WB-10 | Muradpur (Jalangi), West Bengal | NEPZ | 24.089 | 88.696 | 672410.80 | 2665131.90 | 13 | 1 | MH160215 |

| 11 | WLS15-WB-11 | Isalampur, West Bengal | NEPZ | 26.227 | 88.146 | 614505.40 | 2901327.10 | 14 | 2 | MH160216 |

| 12 | WLS15-WB-12 | Dakashin Dinapur, West Bengal | NEPZ | 25.264 | 88.905 | 691837.20 | 2795509.90 | 15 | 1 | MH160217 |

| 13 | WLS17-HR-13 | Budanpur, Haryana | NWPZ | 29.593 | 76.914 | 685393.00 | 3275245.30 | 14 | 2 | MH160218 |

| 14 | WLS17-MH-14 | Pune, Maharashtra | CZ | 18.483 | 73.779 | 371125.30 | 2044019.40 | 1 | 2 | MH160219 |

| 15 | WLS17-MH-15 | Wakapur, Maharashtra | CZ | 20.726 | 76.967 | 704857.90 | 2293078.00 | 2 | 1 | MH160220 |

| 16 | WLS17-HR-16 | Mohay-Ud-Dinpur, Haryana | NWPZ | 29.644 | 77.076 | 700955.90 | 3281138.80 | 59 | 1 | HD 2967 |

| 17 | WLS17-HR-17 | Bati, Haryana | NWPZ | 29.697 | 76.297 | 625522.10 | 3285898.80 | 60 | 1 | HD 2967 |

| 18 | WLS17-PUN-18 | Langroya, Punjab | NWPZ | 31.111 | 76.174 | 611948.10 | 3442538.30 | 61 | 1 | MH160223 |

| 19 | WLS17-MH-19 | Washim, Maharashtra | CZ | 20.195 | 76.925 | 701191.80 | 2234174.80 | 3 | 1 | MH160224 |

| 20 | WLS17-HR-20 | Laha, Naraingarh, Haryana | NWPZ | 30.313 | 77.066 | 698615.60 | 3355265.50 | 24 | 5 | MH160225 |

| 21 | WLS17-HR-21 | Dhanoli, Ambala, Haryana | NWPZ | 30.232 | 77.054 | 697671.80 | 3346277.90 | 62 | 1 | MH160226 |

| 22 | WLS17-HR-22 | Pathreri, Haryana | NWPZ | 30.254 | 77.016 | 693922.80 | 3348650.20 | 53 | 3 | MH160227 |

| 23 | WLS17-HR-23 | Pratapgarh, Kurukhestra, Haryana | NWPZ | 29.982 | 76.880 | 681336.50 | 3318261.00 | 63 | 1 | MH160228 |

| 24 | WLS17-HR-24 | Ladwa, Haryana | NWPZ | 29.991 | 77.038 | 696558.40 | 3319515.30 | 64 | 1 | MH160229 |

| 25 | WLS17-UP-25 | Sherkot, Uttar Pradesh | NWPZ | 29.322 | 78.593 | 266235.60 | 3246067.60 | 55 | 3 | MH160230 |

| 26 | WLS17-RJ-26 | Badh Fatehpura, Rajasthan | NWPZ | 26.888 | 75.559 | 555511.30 | 2974114.30 | 65 | 1 | MH160231 |

| 27 | WLS17-RJ-27 | Ramkui, Rajasthan | NWPZ | 26.960 | 75.550 | 554569.00 | 2982086.90 | 66 | 1 | MH160232 |

| 28 | WLS17-RJ-28 | Sanganer, Rajasthan | NWPZ | 26.819 | 75.696 | 569125.00 | 2966539.20 | 67 | 1 | MH160233 |

| 29 | WLS17-RJ-29 | Boraj, Rajasthan | NWPZ | 26.862 | 75.448 | 544455.90 | 2971262.00 | 68 | 1 | MH160234 |

| 30 | WLS17-UK-30 | Domet, Uttrakhand | NHZ | 30.511 | 77.854 | 773937.40 | 3378919.90 | 24 | 5 | MH160235 |

| 31 | WLS17-UP-31 | Unnao, Uttar Pradesh | NWPZ | 26.536 | 80.486 | 448834.20 | 2935181.00 | 69 | 1 | MH160236 |

| 32 | WLS17-UP-32 | Gazipur, Uttar Pradesh | NWPZ | 25.788 | 83.171 | 717682.80 | 2854017.20 | 70 | 1 | MH160237 |

| 33 | WLS17-MH-33 | Brahmangaon, Maharashtra | CZ | 20.552 | 74.302 | 427242.10 | 2272723.10 | 4 | 2 | MH160238 |

| 34 | WLS17-UP-34 | Nethaur, Uttar Pradesh | NWPZ | 29.327 | 78.392 | 246715.10 | 3246986.20 | 55 | 3 | MH160239 |

| 35 | WLS17-UP-35 | Shahadatpura, Uttar Pradesh | NWPZ | 25.935 | 83.569 | 757294.60 | 2870954.70 | 71 | 1 | MH160240 |

| 36 | WLS17-UP-36 | Shahganj, Uttar Pradesh | NWPZ | 26.051 | 82.678 | 667882.60 | 2882380.80 | 72 | 1 | MH160241 |

| 37 | WLS17-UP-37 | Jaunpur, Uttar Pradesh | NWPZ | 25.743 | 82.702 | 670726.90 | 2848327.10 | 73 | 1 | MH160242 |

| 38 | WLS17-MH-38 | Baramati, Maharashtra | CZ | 18.139 | 74.574 | 454965.60 | 2005623.70 | 5 | 1 | MH160243 |

| 39 | WLS17-UK-39 | Almora, Uttrakhand | NHZ | 29.791 | 73.536 | 358481.80 | 3296537.70 | 25 | 1 | MH160244 |

| 40 | WLS17-UK-40 | Kaladungi, Uttrakhand | NHZ | 29.295 | 79.336 | 338358.60 | 3241810.20 | 26 | 1 | MH160245 |

| 41 | WLS17-UK-41 | Quano, Uttrakhand | NHZ | 30.677 | 77.764 | 764845.00 | 3397092.30 | 4 | 2 | MH160246 |

| 42 | WLS17-MH-42 | Jopul, Maharashtra | CZ | 20.190 | 73.933 | 388515.80 | 2232865.20 | 6 | 1 | MH160247 |

| 43 | WLS17-PUN-43 | Fatehgarh Sahib, Punjab | NWPZ | 31.509 | 76.223 | 616103.60 | 3486677.80 | 74 | 1 | MH160248 |

| 44 | WLS17-PUN-44 | Ropar, Punjab | NWPZ | 31.246 | 76.473 | 640300.80 | 3457750.60 | 75 | 1 | MH160249 |

| 45 | WLS17-PUN-45 | Bhalowal, Punjab | NWPZ | 31.318 | 76.423 | 635408.90 | 3465683.00 | 76 | 1 | MH160250 |

| 46 | WLS16-WB-46 | Petrapole, West Bengal | NWPZ | 23.036 | 88.877 | 692320.50 | 2548732.70 | 16 | 1 | MH160251 |

| 47 | WLS17-PUN-47 | Hiyatpur, Punjab | NWPZ | 31.145 | 76.224 | 616681.90 | 3446297.40 | 77 | 1 | MH160252 |

| 48 | WLS17-PUN-48 | Hakimrpur Apra, Punjab | NWPZ | 31.106 | 75.907 | 586525.20 | 3441703.60 | 78 | 1 | MH160253 |

| 49 | WLS17-PUN-49 | Kalpi, Punjab | NWPZ | 30.288 | 77.000 | 692344.90 | 3352378.30 | 79 | 1 | MH160254 |

| 50 | WLS17-PUN-50 | Rupnagar, Punjab | NWPZ | 30.991 | 76.532 | 646292.50 | 3429639.10 | 80 | 1 | MH160255 |

| 51 | WLS17-PUN-51 | Sherpur Gill, Punjab | NWPZ | 31.082 | 76.265 | 620635.20 | 3439429.50 | 81 | 1 | MH160256 |

| 52 | WLS17-PUN-52 | Sibalmajra, Punjab | NWPZ | 31.099 | 76.242 | 618492.20 | 3441213.70 | 82 | 1 | MH160257 |

| 53 | WLS17-PUN-53 | Gurdashpur, Punjab | NWPZ | 32.046 | 75.383 | 536162.00 | 3545619.30 | 83 | 1 | MH160258 |

| 54 | WLS17-PUN-54 | Moga, Punjab | NWPZ | 30.837 | 75.158 | 515088.80 | 3411540.20 | 84 | 1 | MH160259 |

| 55 | WLS17-PUN-55 | Khabra, Punjab | NWPZ | 31.228 | 76.110 | 605691.40 | 3455353.50 | 85 | 1 | MH160260 |

| 56 | WLS17-PUN-56 | Dasuya, Punjab | NWPZ | 31.813 | 75.656 | 562100.00 | 3519909.40 | 86 | 1 | MH160261 |

| 57 | WLS17-PUN-57 | Jalandar, Punjab, | NWPZ | 31.298 | 75.544 | 551727.20 | 3462736.10 | 87 | 1 | MH160262 |

| 58 | WLS17-PUN-58 | Ludhiana, Punjab | NWPZ | 30.906 | 75.806 | 576977.70 | 3419451.90 | 88 | 1 | MH160263 |

| 59 | WLS17-JK-59 | Kathua, Jammu and Kashmir | NHZ | 32.426 | 75.437 | 541057.80 | 3587777.80 | 27 | 1 | MH160264 |

| 60 | WLS17-JK-60 | RS Pura, Jammu and Kashmir | NHZ | 32.736 | 74.830 | 484087.30 | 3622074.90 | 28 | 1 | MH160265 |

| 61 | WLS17-JK-61 | Chatha, Jammu and Kashmir | NHZ | 32.640 | 74.800 | 481229.90 | 3611389.90 | 29 | 1 | MH160266 |

| 62 | WLS17-JK-62 | Barnai, Jammu and Kashmir | NHZ | 32.709 | 74.789 | 480216.50 | 3619064.90 | 30 | 1 | MH160267 |

| 63 | WLS17-JK-63 | Udhaywall, Jammu and Kashmir | NHZ | 32.741 | 74.821 | 483266.30 | 3622559.80 | 31 | 1 | MH160268 |

| 64 | WLS17-JK-64 | Ramghar, Jammu and Kashmir | NHZ | 32.554 | 74.900 | 490617.60 | 3601873.00 | 32 | 1 | MH160269 |

| 65 | WLS17-JK-65 | Kana check, Jammu and Kashmir | NHZ | 32.757 | 74.849 | 485811.80 | 3624358.70 | 33 | 1 | MH160270 |

| 66 | WLS17-JK-66 | Domana, Jammu and Kashmir | NHZ | 32.769 | 74.817 | 482841.90 | 3625643.60 | 34 | 1 | MH160271 |

| 67 | WLS17-JK-67 | Ranbir Singh pura, Jammu and Kashmir | NHZ | 32.606 | 74.734 | 475034.80 | 3607688.00 | 35 | 1 | MH160272 |

| 68 | WLS17-PUN-68 | Kurdan, Phillaur Punjab | NWPZ | 31.047 | 75.944 | 590070.80 | 3435193.70 | 89 | 1 | MH160273 |

| 69 | WLS17-PUN-69 | Khadukhera, Punjab | NWPZ | 30.563 | 76.464 | 640377.70 | 3382102.30 | 43 | 2 | MH160274 |

| 70 | WLS17-MP-70 | Indore, Madhya Pradesh | CZ | 22.698 | 75.880 | 590380.70 | 2510394.30 | 7 | 1 | MH160275 |

| 71 | WLS17-MP-71 | Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh | CZ | 23.214 | 75.786 | 580451.80 | 2567464.00 | 8 | 1 | MH160276 |

| 72 | WLS17-MP-72 | Rewa, Madhya Pradesh | CZ | 24.541 | 81.302 | 530568.70 | 2714113.90 | 9 | 1 | MH160277 |

| 73 | WLS17-MP-73 | Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh | CZ | 23.256 | 77.410 | 746609.30 | 2573922.20 | 10 | 1 | MH160278 |

| 74 | WLS17-MP-74 | Arjani, Madhya Pradesh | CZ | 23.820 | 78.717 | 267429.30 | 2636195.10 | 11 | 1 | MH160279 |

| 75 | WLS17-RJ-75 | Rajpura, Rajasthan | NWPZ | 26.795 | 76.002 | 599620.30 | 2964152.30 | 90 | 1 | MH160280 |

| 76 | WLS17-RJ-76 | Goner, Rajasthan | NWPZ | 26.823 | 75.930 | 592427.20 | 2967202.70 | 91 | 1 | MH160281 |

| 77 | WLS17-HP-77 | Bara, Himachal Pradesh | NHZ | 31.481 | 76.575 | 649577.80 | 3484017.90 | 36 | 1 | MH160282 |

| 78 | WLS17-HP-78 | Rudhanni, Himachal Pradesh | NHZ | 31.453 | 76.690 | 660539.10 | 3481039.00 | 24 | 5 | MH160283 |

| 79 | WLS17-HP-79 | Kangra, Himachal Pradesh | NHZ | 32.109 | 76.266 | 619457.20 | 3553261.30 | 37 | 1 | MH160284 |

| 80 | WLS17-HP-80 | Mandi, Himachal Pradesh | NHZ | 31.680 | 76.940 | 683934.70 | 3506583.40 | 38 | 1 | MH160285 |

| 81 | WLS17-HP-81 | Ratti, Himachal Pradesh | NHZ | 31.604 | 76.903 | 680558.50 | 3498104.00 | 39 | 1 | MH160286 |

| 82 | WLS17-HP-82 | Ramshehar, Himachal Pradesh | NHZ | 31.091 | 76.790 | 670693.40 | 3441100.20 | 40 | 1 | MH160287 |

| 83 | WLS17-HP-83 | Una, Himachal Pradesh | NHZ | 31.472 | 76.243 | 618040.90 | 3482586.40 | 41 | 1 | MH160288 |

| 84 | WLS17-HP-84 | Sundar Nagar, Himachal Pradesh | NHZ | 31.171 | 76.853 | 676644.10 | 3450015.20 | 42 | 1 | MH160289 |

| 85 | WLS17-HP-85 | Kullu, Himachal Pradesh | NHZ | 31.954 | 77.095 | 698035.70 | 3537234.10 | 43 | 2 | MH160290 |

| 86 | WLS17-UP-86 | Shamli, Uttar Pradesh | NWPZ | 29.625 | 77.090 | 702362.60 | 3279039.20 | 92 | 1 | MH160291 |

| 87 | WLS17-UP-87 | Mohamdabad, Uttar Pradesh | NWPZ | 28.772 | 78.164 | 223090.50 | 3186033.70 | 24 | 5 | MH160292 |

| 88 | WLS17-UP-88 | Rajak Nagar, Uttar Pradesh | NWPZ | 29.495 | 77.245 | 717686.80 | 3264898.00 | 53 | 3 | MH160293 |

| 89 | WLS17-UP-89 | Faizabad, Uttar Pradesh | NWPZ | 26.769 | 82.145 | 613856.10 | 2961394.30 | 93 | 1 | MH160294 |

| 90 | WLS17-HP-90 | Kunihar, Himachal Pradesh | NHZ | 31.084 | 76.969 | 687785.90 | 3440527.40 | 44 | 1 | MH160295 |

| 91 | WLS17-HP-91 | Diggal, Himachal Pradesh | NHZ | 31.084 | 76.869 | 678280.10 | 3440428.70 | 45 | 1 | MH160296 |

| 92 | WLS17-HP-92 | Jai Nagar, Himachal Pradesh | NHZ | 31.171 | 76.853 | 676644.10 | 3450015.20 | 46 | 1 | MH160297 |

| 93 | WLS17-JK-93 | Khandwalmore, Jammu and Kashmir | NHZ | 32.405 | 75.307 | 528843.30 | 3585363.40 | 47 | 2 | MH160298 |

| 94 | WLS17-JK-94 | Dablehar, Jammu and Kashmir | NHZ | 32.576 | 74.760 | 477448.10 | 3604322.60 | 48 | 2 | MH160299 |

| 95 | WLS17-JK-95 | Satwari, Jammu and Kashmir | NHZ | 32.737 | 74.831 | 484195.20 | 3622165.00 | 24 | 5 | MH160300 |

| 96 | WLS17-JK-96 | Saikalan, Jammu and Kashmir | NHZ | 32.507 | 74.791 | 480370.00 | 3596643.80 | 49 | 1 | MH160301 |

| 97 | WLS17-JK-97 | Udhaywalla, Jammu and Kashmir | NHZ | 32.741 | 74.821 | 483266.30 | 3622559.80 | 48 | 2 | MH160302 |

| 98 | WLS17-JK-98 | Quderpur, Jammu and Kashmir | NHZ | 32.578 | 74.760 | 477448.50 | 3604544.40 | 47 | 2 | MH160303 |

| 99 | WLS17-JHK-99 | Dhampur, Jharkhand | NEPZ | 23.921 | 86.134 | 411867.50 | 2645781.20 | 17 | 1 | MH160304 |

| 100 | WLS17-JHK-100 | Kannu, Jharkhand | NEPZ | 24.247 | 87.255 | 525877.30 | 2681561.20 | 18 | 1 | MH160305 |

| 101 | WLS17-JHK-101 | Jharkhandi, Jharkhand | NEPZ | 24.344 | 86.026 | 401160.80 | 2692643.80 | 19 | 1 | MH160306 |

| 102 | WLS17-JHK-102 | Deoghar, Jharkhand | NEPZ | 24.471 | 86.693 | 468928.00 | 2706386.60 | 20 | 1 | MH160307 |

| 103 | WLS17-JHK-103 | Gola-Baniyatu, Jharkhand | NEPZ | 23.498 | 85.660 | 363208.90 | 2599294.30 | 21 | 1 | MH160308 |

| 104 | WLS17-JHK-104 | Mahadebganj, Jharkhand | NEPZ | 24.343 | 87.584 | 559211.90 | 2692359.80 | 22 | 1 | MH160309 |

| 105 | WLS17-JHK-105 | Machut, Jharkhand | NEPZ | 25.063 | 87.620 | 562485.70 | 2772018.10 | 23 | 1 | MH160310 |

| 106 | WLS17-HP-106 | Lohar ghat, Himachal Pradesh | NHZ | 31.190 | 76.838 | 675153.00 | 3452112.90 | 50 | 1 | MH160311 |

| 107 | WLS17-UK-107 | Kashipur, Uttrakhand | NHZ | 29.203 | 78.968 | 302468.50 | 3232131.60 | 51 | 1 | MH160312 |

| 108 | WLS17-UP-108 | Ballia, Uttar Pradesh | NWPZ | 28.200 | 79.361 | 339100.50 | 3120415.90 | 94 | 1 | MH160313 |

| 109 | WLS17-UP-109 | Sultanpur, Uttar Pradesh | NWPZ | 29.160 | 79.062 | 311507.30 | 3227320.80 | 95 | 1 | MH160314 |

| 110 | WLS17-UP-110 | Mirzapur, Uttar Pradesh | NWPZ | 25.133 | 82.551 | 656350.60 | 2780566.60 | 96 | 1 | MH160315 |

| 111 | WLS17-UP-111 | Jagdishpur, Uttar Pradesh | NWPZ | 26.749 | 80.542 | 454446.60 | 2958723.20 | 97 | 1 | MH160316 |

| 112 | WLS17-UP-112 | Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh | NWPZ | 26.766 | 80.977 | 497740.90 | 2960550.80 | 98 | 1 | MH160317 |

CZ, Central zone; NEPZ, North East Plain zone; NHZ, North hill zone; NWPZ, North Western Plain zone; HG, Haplotype group; HC, Haplotype Count.

Genomic Preparations

For genomic DNA extraction, isolates of UST were transferred, using a sterile needle, from Petri dishes to 100 ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing potato dextrose yeast (PDY) broth. The cultures were grown for 10 days in an orbital shaker (150 rpm) at 25 ± 1°C. The fungal mat harvested on sterile Whatman filter paper, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and ground to fine powder with pestle and mortar. Cetyl trimethyl-ammonium bromide (CTAB) method was used to extract genomic DNA as described by Kumar et al. (2013b). DNA was quantified by recording absorbance at 260 nm and determined purity by calculating the ratio of absorbance at 260 nm to that of 280 nm. The concentration of DNA was adjusted to 50 ng μl−1 for PCR analysis.

RNA Polymerase II Second Largest Subunit (RPB2) Gene Amplification and Sequence Analysis

A portion of the RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (RPB2) gene was amplified for all the 112 UST isolates using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primer RPB2F (5′- AACCACCGATTTGGAGCAGT-3′) and RPB2R (5′- ACTCATTAGATGGCGGGGAGA-3′). The primers were designed using the NCBI accession number DQ846896.1. PCR amplification was performed in Q cycler 96 (Hain Lifescience, UK). Each PCR reaction mixture (50 μl) consisting of 50 ng template DNA, 1.5 μM of each primer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each deoxynucleotides, 1.5 unit of Taq DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, USA), and final volume of 50 μl was maintained by adding distilled water. The amplification was done as initial denaturing at 94°C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 1 min, extension at 72°C for 1 min and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. The amplified PCR products were separated on 1% agarose gel, and the desired specific band was purified by Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. DNA was sequenced commercially at the Eurofins Genomics India Pvt. Ltd. (Bangalore, India). A consensus sequence was obtained from the sequencing of both forward and reverse strands, and further data quality were checked using Chromas 2.32 (Technelysium Pty. Ltd.). BlastN search programme was used to compare the sequences available in National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) databases. The sequences were aligned using MEGA 7 (Kumar et al., 2016) and gaps and missing data were not considered for phylogenetic analysis. Evolutionary tree was drawn using neighbor-joining (NJ) method (Saitou and Nei, 1987) and evolutionary distances were determined by Kimura (1980). The nucleotide sequences of RPB2 gene were submitted to NCBI GenBank.

Microsatellite Genotyping

For the amplification of each microsatellite marker gradient PCR was performed to select the best annealing temperature. PCR amplifications were performed in Q cycler 96 (Hain Lifescience, UK) in a total volume of 10 μl containing Promega™ PCR Master Mix, additional 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.05–0.15 μM forward primer, 0.05–0.15 μM reverse primer, and 1.0 μl template DNA (50 ng μl−1). PCR cocktail without template DNA was taken as control. PCR was programmed for initial denaturation at 94°C for 4 min; followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 60 s, annealing at 51, 52, 53, 54, and 55°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min; with a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min. PCR products were separated in 4% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide along 100 bp ladder (Genei, Bangalore) to know the polymorphism. Test isolates were scored on the basis of amplification and non-amplification of SSR markers. The numbers of varoius alleles per locus, effective alleles per locus, private alleles and Shannon's Information Index were computed for each population using GenAlEx 6.5 (Peakall and Smouse, 2012). The polymorphic information content (PIC) value for each SSR markers was calculated using the formula:

| (1) |

where k is the total number of alleles detected for a microsatellite; Pi is the frequency of the ith allele in the set.

Population Structure and Gene Flow

The presence (1) and absence (0) of desired amplicom for each SSR marker in all the 112 isolates were treated as binary characters and was analyzed using the NTSYS-pc program V2.1 (Rohlf, 2002). All the isolates were grouped in different clusters using Un-weighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic average [UPGMA; (Yu et al., 2006)] in the SAHN subprogram. Dice similarity coefficient based on the proportion of shared alleles with the SIMQUAL was used to know the genetic similarity between isolates. Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) based on SSR markers was calculated using GenAlEx 6.5 to know the genetic diversity in different populations [Table 1; (Peakall and Smouse, 2012)]. The fixation index (Fst) of the total populations and pairwise Fst among all pairs of populations were calculated to investigate population differentiation, and significance was tested based on 1,000 bootstraps. Gene flow among populations was calculated based on the number of migrants per generation (Nm) using the formula,

| (2) |

Population structure analysis was executed with STRUCTURE 2.3.4 (Pritchard et al., 2000) using microsatellite loci data. The optimum number of populations (K) was selected by testing K = 1 to K = 15 using five independent runs of 25,000 burn-in period length at fixed iterations of 100,000 with a model allowing for admixture and correlated allele frequencies. The optimum number of population was predicted using the simulation method of Evanno et al. (2005) in STRUCTURE HARVESTER version 0.6.92 (Earl and vonHoldt, 2012). The K value was determined by the log probability of data [Ln P(D)] based on the rate of change in LnP(D) between successive K. Bottleneck v1.2 was used to determine whether there was an excess (a recent population bottleneck) or deficit (a recent population expansion) in H (gene diversity) relative to the number of alleles present in UST populations (Piry et al., 1999). To determine whether loci displayed a significant excess or deficit in gene diversity Sign and Wilcoxon significance tests (WT) were performed (Cornuet and Luikart, 1996).

The Tajima's D value was estimated using the DnaSP program (Tajima, 1983). Number of haplotypes, number of segregating sites, and the π and Φw measures of nucleotide diversity for each population were determined with clone-corrected samples whereas, Nei's haplotype diversity (Hd) was also determined before sample clone-corrected. The value of π and Φw represents the average number of pairwise nucleotide differences and the total number of segregating sites in a set of DNA sequences, respectively. MULTILOCUS version 1.31 was used to measure linkage disequilibrium among SSR loci using the index of association (IA) and rBarD index (Agapow and Burt, 2001). Tests of departure from random mating for both indices were done with 10,000 randomizations of the complete and clone-corrected MLH dataset. To dissect the recombination in UST populations, the proportion of compatible pairs of loci (PrCP) was determined using MULTILOCUS v.1.31 (Agapow and Burt, 2001). The null hypothesis of random mating was rejected if more compatible loci than expected in a randomized population were observed (P < 0.05).

Results

Gene Sequence Analysis and Haplotypic Diversity

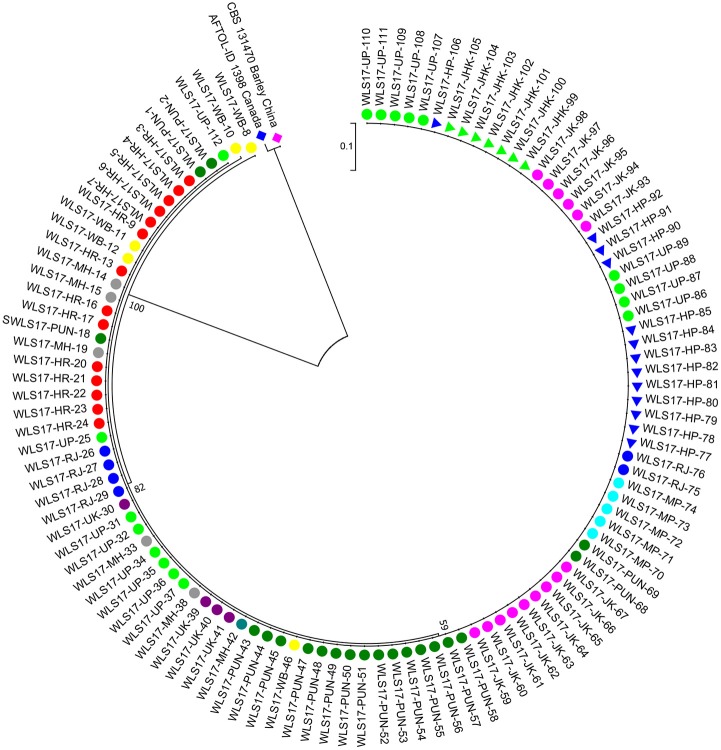

The second largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB2) gene sequences of all the 112 UST isolates were compared with those from known species of Ustilago available in the NCBI database (Figure 1). The results confirmed that all the 112 isolates are Ustilago segetum tritici. Sequences were deposited at NCBI GenBank, and got accession numbers (Table 1). Phylogenetic analysis of RPB2 gene from 112 isolates turn out from different wheat growing zones showed that they are related to each another and divergent from the isolate reported from Canada (Figure 1). Analysis of the sequences of the RPB2 gene loci in the 112 isolates by DnaSP version 5.10 identified a total of 98 haplotypes (Table 1). Eighty three haplotypes were represented by single isolate and the remaining 15 haplotypes had minimum two isolates (Table 1). Fifteen haplotypes, which contained at least two isolates, were found only in NWPZ, CZ and NHZ. Haplotype 47 (WLS17-JK-93 and WLS17-JK-98) and haplotype 48 (WLS17-JK-94 and WLS17-JK-97) were collected from the NHZ while haplotype 53 (WLS17-HR-3, WLS17-HR-22 and WLS17-UP-88) and haplotype 55 (WLS17-HR-5, WLS17-UP-25 and WLS17-UP-34) were identified in NWPZ population only (Table 1). However, haplotype 24 (WLS17-UP-87 and WLS17-HR-20, WLS17-UK-30, WLS17-HP-78, and WLS17-JK-95) and haplotype 43 (WLS17-PUN-69 and WLS17-HP-85) were shared by NWPZ and NHZ populations. Similarly, CZ (WLS17-PUN-2) and NWPZ (WLS17-MH-14) shared haplotype 1, while haplotype 14 (WLS16-WB-11 and WLS17-HR-13) shared between NWPZ and NEPZ. NHZ and CZ shared haplotype 4 (WLS17-UK-41 and WLS17-MH-37). All the four populations displayed low nucleotide diversity (>0.0001) and haplotype diversity (>0.9905) (Table 2). CZ and NWPZ population possessed the highest haplotype diversity (1.000), while NEPZ population showed highest nucleotide diversity (0.00456) (Table 2). Five mutations were detected in entire populations (Table 2). NEPZ population showed highest number of singleton mutations. Further, estimates of DNA divergence between populations based on RPB2 gene sequence analysis indicated that mutation events shared between UST population of CZ and NHZ and CZ and NWPZ (Table S1).

Figure 1.

A neighbor-joining tree of RNA polymerase II gene (RPB2) sequences of the 112 isolates of UST from wheat growing states of India.

Table 2.

DNA polymorphism data for Ustilago segetum tritici (UST) isolates based on RPB2 gene sequence comparisons.

| DNA polymorphism parameter | Populations | Overall | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CZ | NEPZ | NHZ | NWPZ | ||

| Number of sequences | 11 | 12 | 33 | 56 | 112 |

| Selected region analyzed | 1–687 | 1–687 | 1–687 | 1–687 | 1–687 |

| Number of polymorphic sites (S) | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Number of mutations (Eta) | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| Total number of singleton mutations, Eta(s) | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Number of haplotypes (h) | 11 | 12 | 29 | 51 | 98 |

| Haplotype (gene) diversity (Hd) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9905 | 0.9955 | 0.9965 |

| Nucleotide diversity (Pi) | 0.00246 | 0.00456 | 0.00139 | 0.00053 | 0.00053 |

| Theta (per sequence) from Eta | 0.68283 | 1.32456 | 0.73919 | 0.65308 | 0.945 |

| Theta (per site) from Eta | 0.00330 | 0.00643 | 0.00357 | 0.00322 | 0.00471 |

| Number of nucleotide differences (k) | 0.50909 | 0.93939 | 0.28788 | 0.10714 | 0.107 |

| Tajima's D | −0.77815 | −1.02271 | −1.39934 | −1.68380 | −1.85385 |

| Fu and Li's D* test statistic (FLD*) | −0.33034 | −0.45895 | −0.29252 | −3.09074 | −3.28229 |

| Fu and Li's F* test statistic (FLF*) | −0.45160 | −0.68098 | −0.71183 | −3.10485 | −3.20471 |

| Fu's Fs statistic (FFs) | −0.659 | 0.560 | −2.415 | −4.521 | −6.254 |

| Minimum number of recombination events (Rm) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The population statistic parameters revealed statistically negative values of Tajima's D (−1.68380 to −0.77815) in UST populations of different wheat growing zones and provided evidence that the dominance of purifying selection and population expansion is operating in UST isolates (Table 2). Similarly, the test statistic FLD* and FLF* reflected analogous type of results for UST isolates and highlighted the principle of operation of purifying selection and population size expansion in different wheat growing zones. The statistically significant negative value of FFs statistic except NEPZ further strongly denotes the expansion observed in CZ, NWPZ, and NHZ population (Table 2).

Marker Development, SSRs Polymorphism and Gene Diversity

To evaluate allelic diversity among UST isolates, 35 microsatellite markers were used. Twenty five SSR primer pairs produced clear single amplicons while rest did not amplify. Out of 25 primers, only 16 (Table 3) showed polymorphism and therefore used in genetic diversity analysis of 112 UST isolates originated from four geographical distinct zones of India. The polymorphism of the different SSR loci is presented in Table 3. The alleles per locus varied from two to four and allele size ranged from 170 to 750 bp. The PIC values ranged from 0.3713 to 0.6632. One SSR loci (UST31) was highly informative (PIC ≥ 0.5) and rest all loci were reasonably informative (0.5 < PIC > 0.25). The 16 polymorphic primer pairs revealed a total of 68 alleles across the 34 loci in 112 isolates, ranging from 2 to 4 alleles per isolate (Table 3). The markers were all selectively neutral according to the Ewens-Watterson test (Table S2).

Table 3.

Characteristics of sixteen neutral microsatellite markers used in the study for population genetic diversity analysis of Ustilago segetum tritici (UST) isolates.

| S. No. | Sequence (5′-3′) | Motif | Amplicon size (bp) | Number of allele | Ta (°C) | He | PIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | USTF 5: GCTCGTCTACCTCTGCGATACT | (GGA)5 | 215–241 | 2 | 55 | 0.4984 | 0.3742 |

| USTR 5: TCTGCATCTCAATCAACCAATC | |||||||

| 2 | USTF 6: AGACATGCACCGTAACAACAAC | (CGG)6 | 180–200 | 2 | 55 | 0.4986 | 0.3743 |

| USTR 6: TACCCTCCATACTCTTGTCCGT | |||||||

| 3 | USTF 7: AAGCATACTCAAGGCAGGGTAA | (CAT)5 | 170–240 | 2 | 54 | 0.4854 | 0.3676 |

| USTR 7: GTTCTCGGATGGTCTCGTCTAC | |||||||

| 4 | USTF 14: AAAAGTCATCCTCGTTTCGGTA | (CCG)6 | 180–230 | 2 | 55 | 0.4926 | 0.3713 |

| USTR 14: AGATAGGGAAGCAAATCATGGA | |||||||

| 5 | USTF 16: GCCTCTTCATCTCTCTCCTCAC | (GAC)6 | 220–270 | 2 | 52 | 0.4948 | 0.3724 |

| USTR 16: TGACTCTTCTGCATCATATCGG | |||||||

| 6 | USTF 17: TCTTGTGGAGTCTGCTGTTGTT | (TGC)5 | 230–250 | 2 | 52 | 0.4991 | 0.3746 |

| USTR 17: GTAGCTTCAGGTCGCATCACTT | |||||||

| 7 | USTF 23: TCGTGAAAACTAACAGAGCCAA | (AAAT)4 | 220–250 | 2 | 52 | 0.498 | 0.374 |

| USTR 23: ACACCTATTTGCGTGAAGGAGT | |||||||

| 8 | USTF 25: TACTTCTCCTCCTCCTCCTCCT | (TATT)5 | 285–300 | 2 | 52 | 0.4997 | 0.3748 |

| USTR 25: GAACTCGCAAAGTGGTTTCTCT | |||||||

| 9 | UST 26: AGAGACCAAGTCGAATCCAAAG | (CAAGG)6 | 294–320 | 2 | 52 | 0.4991 | 0.3746 |

| USTR 26: CCTTGCCTACTTCTCCCTACCT | |||||||

| 10 | USTF 27: CATTTCAGTGTTGGACAAGCAT | (GTGTCA)4 | 250–300 | 2 | 54 | 0.4959 | 0.3729 |

| USTR 27: AGAGAGTTTCGTAGTTGGGCAG | |||||||

| 11 | USTF 30: GGTGATTGGAAGACCACAGAAT | (AAGCCA)5 | 227–250 | 2 | 55 | 0.4988 | 0.3744 |

| USTR 30: GTTTTGAACTCTCTGCTTTGGG | |||||||

| 12 | USTF 31: CACAAACACACACACACACACA | (GCTCCC)4 | 224–750 | 4 | 54 | 0.717 | 0.6632 |

| USTR 31: CTGAACAGTAAAGCCTGAAGGG | |||||||

| 13 | USTF 32: TCCTACATTGGGATGACTGATG | (CAACGG)4 | 217–250 | 2 | 52 | 0.4975 | 0.3737 |

| USTR 32: GACTCGCTTCTTGTTCTTGGTT | |||||||

| 14 | USTF 33: GAAAGAGAGAGGGAGGGAAGAG | (GGAGAA)4 | 230–250 | 2 | 53 | 0.4991 | 0.3746 |

| USTR 33: TGCGTATAGGTATGTGTGGCTT | |||||||

| 15 | USTF 34: GAAGAAAATGCTAGAGCGAAGG | (CA)8 | 216–250 | 2 | 55 | 0.4973 | 0.3737 |

| USTR 34: AGCAGAAGGTGAGAGAGCGTAT | |||||||

| 16 | USTF 36: ATGAGGTCAAGAGTCAGCAACA | (GA)8 | 175–200 | 2 | 54 | 0.4978 | 0.3739 |

| USTR 36: ATTCGTCAAGATGCCTTTCACT |

Population Genetic Diversity

The genetic diversity indices for diverse four UST populations from different wheat growing zones are depicted in Table 4. The number of different alleles (Na), effective alleles (Ne) and expected heterozygosity (He) averaged across all loci ranged from 1.824 to 2.0, 1.695 to 1.721, and 0.373 to 0.406, respectively for the four different populations (CZ, NEPZ, NHZ, and NWPZ). The NWPZ population had the highest Na values (2.000) while the CZ population had the lowest (1.765). Expected heterogyzosity (He) and effective Alleles (Ne) values were lowest in CZ population (He = 0.373; Ne = 1.695) and the highest in NWPZ population (He = 0.406; Ne = 1.729). Similarly, unbiased gene diversity (uHe) was the lowest in NHZ population (uHe = 0.381) and the highest in NWPZ population (uHe = 0.410), with an average of 0.396. The polymorphic loci (%) fell in the range of 88.24% (NHZ and NEPZ) to 100% (NWPZ), with an average of 88.35% (Table 4). However, NHZ and NWPZ population showed the highest number (17) of polymorphic loci. Information index based on the Shannon's Index (I), the highest diversity was recorded in NWPZ (I = 0.589) population, whereas it was lowest in CZ (I = 0.531) population. Of all the analyzed populations, no private allele was found in entire population. The genetic diversity within populations (Hs) ranged from 0.0501 to 0.4943 with an average of 0.3367 (Table S2), and responsible for 91% of the total genetic diversity (HT = 0.3611). The proportion of the total genetic diversity attributable to the population differentiation (Gst) ranged from 0.0029 to 0.391 with an average of 0.0678 over all loci (Table S2).

Table 4.

Summary of the population diversity indices calculated on the basis of SSR markers.

| Zone | N | Na | Ne | I | He | uHe | PL (%) | Number of polymorphic bands | Least common bands (≤5%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CZ | 11 | 1.765 ± 0.136* | 1.695 ± 0.088 | 0.531 ± 0.063 | 0.373 ± 0.045 | 0.391 ± 0.047 | 82.35 | 16 | 16 |

| NEPZ | 12 | 1.824 ± 0.128 | 1.721 ± 0.085 | 0.552 ± 0.056 | 0.387 ± 0.041 | 0.403 ± 0.043 | 88.24 | 16 | 16 |

| NHZ | 33 | 1.882 ± 0.081 | 1.697 ± 0.086 | 0.536 ± 0.060 | 0.375 ± 0.044 | 0.381 ± 0.044 | 88.24 | 17 | 16 |

| NWPZ | 56 | 2.000 ± 0.000 | 1.729 ± 0.064 | 0.589 ± 0.032 | 0.406 ± 0.027 | 0.410 ± 0.027 | 100.00 | 17 | 17 |

| Mean | 1.868 ± 0.051 | 1.710 ± 0.040 | 0.552 ± 0.027 | 0.385 ± 0.020 | 0.396 ± 0.020 | 82.35 |

N, number of isolates; Na, No. of different Alleles; Ne, No. of Effective Alleles = 1/(p2 + q2); I, Shannon's Information Index; He, Expected Heterozygosity = 2 X pX q; uHe, Unbiased Expected heterozygosity = [2N/(2N-1)] X He; PL (%) = Percent Polymorphic Loci.

The values after ± denote the standard errors.

CZ, Central zone; NEPZ, North East Plain zone; NHZ, North Hill zone; NWPZ, North Western Plain zone.

Population Genetic Structure and Gene Flow

The AMOVA analysis comparing the four populations showed that 1% of the total variance was distributed among zones. A relatively higher proportion of the variation (91 %) was distributed within UST isolates (Table 5). Genetic variation among wheat growing zones (Fst = 0.012), isolates (Fis = 0.079) and within isolates (Fit = 0.090) was mentioned in Table 5. Pairwise Fst values of the genetic distance between different populations were low but significant (P < 0.01; Table 6).

Table 5.

Summary of the analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) results for 112 isolates of Ustilago segetum tritici (UST) (n = 112).

| Source | df | SS | MS | Estimated variance | Percentage % | F-Statistics | Value | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among population | 3 | 16.457 | 5.486 | 0.039 | 1% | Fst | 0.012 | 0.606 |

| Among individuals | 108 | 388.048 | 3.593 | 0.263 | 8% | Fis | 0.079 | 0.019 |

| Within individuals | 112 | 343.500 | 3.067 | 3.067 | 91% | Fit | 0.090 | 0.606 |

| Total | 223 | 748.004 | 3.369 | 100% |

Df, degree of freedom; SS, sum of squared observations; MS, mean of squared observations; Fst = AP/(WI + AI + AP) = AP/TOT; Fis, AI/(WI + AI); Fit, (AI + AP)/(WI + AI + AP) = (AI + AP)/TOT; Nm = [(1/Fst)-1]/4] = 21.0. Key: AP , Est. Var. Among zones, AI Estimated variance among isolates, WI = Estimated variance within isolates.

Table 6.

Measure of the pair-wise comparisons of genetic distance (Fst), genetic flow (Nm) and Nei's unbiased genetic identity for Ustilago segetum tritici (UST) isolates collected from the four zones of India.

| Population 1 | Population 2 | Fst | Nm | Nei's unbiased genetic identity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSR loci | RPB2 gene | ||||

| NEPZ | CZ | 0.016 | 0.045 | 14.989 | 0.9358 |

| NEPZ | NWPZ | 0.009 | 0.041 | 4.934 | 0.944 |

| NEPZ | NHZ | 0.037 | 0.045 | 6.499 | 0.9514 |

| CZ | NWPZ | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.9907 |

| CZ | NHZ | 0.048 | 0.000 | 29.131 | 0.9781 |

| NHZ | NWPZ | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.9947 |

CZ, Central zone; NEPZ, North East Plain zone; NHZ, North hill zone; NWPZ, North Western Plain zone.

The average gene flow among populations (Nm) was ranged from 0.00 (between NWPZ and NHZ; between NWPZ and CZ) to 29.131 (between CZ and NHZ). Pairwise estimates of gene flow (Nm) indicated that Nm value was more than 1.0 in most of the population pairs suggesting gene flow between populations, although with different magnitude except NWPZ and NHZ and NWPZ and CZ (Table 6). The highest value was observed among pair of CZ and NHZ populations (Nm = 29.131; Fst = 0.048) followed by CZ and NEPZ pair (Nm = 14.989; Fst = 0.016). When population of NEPZ was compared with other populations for genetic distance (Fst) on the basis of SSR (0.009–0.037) and RPB2 gene loci (0.041–0.045) and gene flow (Nm = 4.934–14.989) indicating these populations are differentiated with low gene flow. Pair wise comparison of NHZ and NWPZ recorded the highest indices of Nei's unbiased genetic identity (0.9947), while CZ and NHZ showed lowest levels of genetic identity (0.9358) (Table 6).

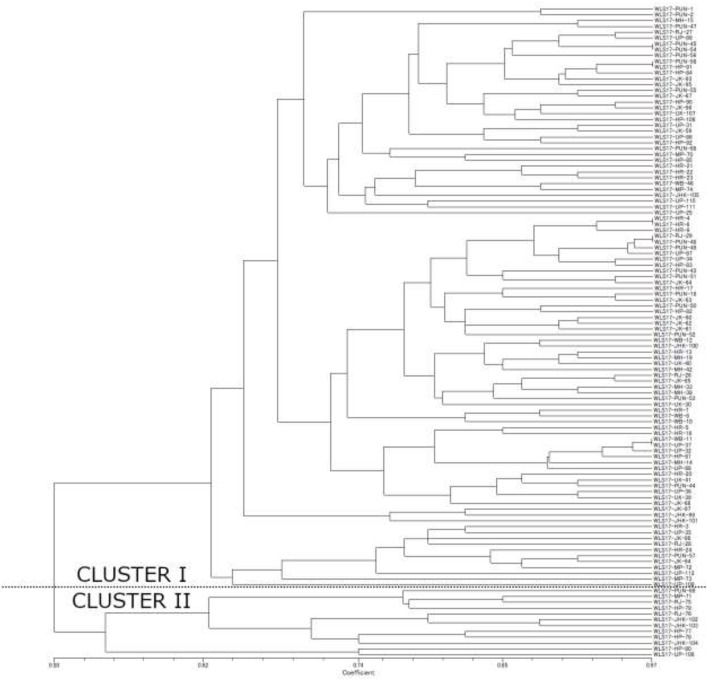

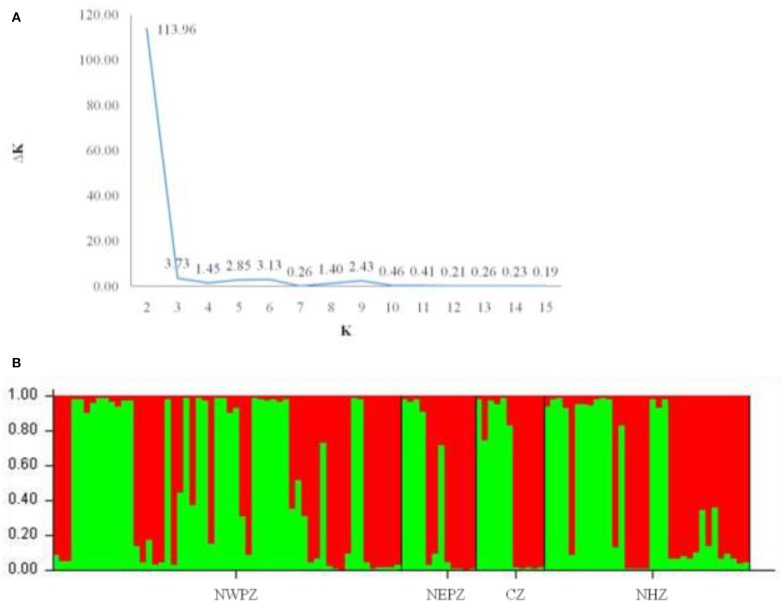

The dendrogram based on unweighted Neighbor-joining method grouped all the 112 isolates representing four populations into two major clusters (Figure 2). Among these, 100 and 12 isolates were grouped in cluster 1 and cluster 2. The grouping by UPGMA using genetic distances do not showed any spatial clustering among the different geographic zones (Figure 2). Several subgroups within cluster 1 were observed irrespective to populations, indicating genetic variability within and among isolates in each population. The similarity coefficient of overall isolates averaged 0.50. The substructure analysis for genetic relationship among UST isolates, excluding loci with null alleles, showed a clear ΔK peak at K = 2 (ΔK = 113.96) (Figure 3A) and K = 2 was the most likely value thus revealed that all individuals grouped into two major clusters (Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

Unweighted Neighbor-joining tree using the simple matching similarity coefficient based on 16 microsatellite markers for the 112 isolates of UST isolated from wheat spikes in India.

Figure 3.

Cluster analyses of UST populations from four different wheat growing zones of India (results from Structure v2.2). (A) Each isolate is represented by a bar, divided into K colors, where K = 2 is the number of clusters assumed. Individuals are sorted according to Q, the inferred clusters; (B) Magnitude of ΔK calculated for each level of K. Maximum ΔK indicates the most likely number of UST populations (K = 2).

Linkage Disequilibrium and Population Expansion

Linkage disequilibrium analysis was performed to infer the reproductive strategy. The values of IA (0.991–2.034) and rbarD indices (0.066–0.134) in the association tests differed significantly from zero in all the UST populations (Table 7). UST isolates sampled from different wheat growing zones rejected the null hypothesis of gametic equilibrium, this shows that isolates in each zone were not under random mating (Table 7).

Table 7.

Estimation of linkage disequilibrium by the index of association (IA) and the unbiased (rd) statistic of Indian Ustilago segetum tritici (UST) isolates.

| Population | IA | rBarD | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CZ | 1.399 | 0.092 | < 0.001 |

| NEPZ | 2.034 | 0.134 | < 0.001 |

| NHZ | 0.991 | 0.066 | < 0.001 |

| NWPZ | 1.281 | 0.082 | < 0.001 |

| Total | 1.169 | 0.075 | < 0.001 |

Index of association (IA) and rBarD, a modified index of association (1); P-values were estimated from 1,000 randomizations and are identical for IA and rBarD.

The results depicted in Table 8 shows that all the UST populations evolved through stepwise mutation method (SMM). The sign tests in Bottleneck revealed a significant H deficit in 1 of the 13 loci under IAM (P = 0.00027), TPM (P = 0.00070) and SMM (P = 0.00132) model of evolution, indicating recent population expansion in CZ. Similarly, in NHZ and NWPZ population, significant H deficit in 1 of the 14 loci under IAM, TPM, and SMM model of evolution were observed (Table 8).

Table 8.

Comparison of observed genotypic diversity (H) and expected genotypic diversity (HEQ) at mutation-drift equilibrium based on the observed number of alleles with infinite number of alleles.

| Zone | Test | Parameter | IAM | TPM | SMM | Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CZ | ST | Number of loci with heterozygosity excess expected | 6.35 | 6.86 | 7.22 | Shifted |

| Loci with heterozygosity deficiency or excess | 1/13 (P = 0.00027) | 1/13 (P = 0.00070) | 1/13 (P = 0.00132) | |||

| SDT | T2 values (Probability) | 4.024 (P = 0.00003) | 3.492 (P = 0.00024) | 3.168 (P = 0.00077) | ||

| WT | One tail for H deficiency | P = 0.99997 | P = 0.99994 | P = 0.99991 | ||

| One tail for H excess: | P = 0.00006 | P = 0.00009 | P = 0.00015 | |||

| Two tails for H excess and deficiency: | P = 0.00012 | P = 0.00018 | P = 0.00031 | |||

| NEPZ | ST | Number of loci with heterozygosity excess expected | 6.53 | 6.82 | 7.22 | Shifted |

| Loci with heterozygosity deficiency or excess | 0/14 (P = 0.00002) | 1/13 (P = 0.00064) | 1/13 (P = 0.00130) | |||

| SDT | T2 values (Probability) | 5.195 (P = 0.00000) | 4.575 (P = 0.00000) | 4.182 (P = 0.00001) | ||

| WT | One tail for H deficiency | P = 1.00000 | P = 0.99997 | P = 0.99997 | ||

| One tail for H excess: | P = 0.00003 | P = 0.00006 | P = 0.00006 | |||

| Two tails for H excess and deficiency | P = 0.00006 | P = 0.00012 | P = 0.00012 | |||

| NHZ | ST | Number of loci with heterozygosity excess expected | 6.32 | 6.75 | 7.10 | Shifted |

| Loci with heterozygosity deficiency or excess | 1/14 (P = 0.00005) | 1/14 (P = 0.00012) | 1/14(P = 0.00024) | |||

| SDT | T2 values (Probability) | 5.158 (P = 0.00000) | 4.635 (P = 0.00000) | 4.197 (P = 0.00001) | ||

| WT | One tail for H deficiency | P = 0.99997 | P = 0.99995 | P = 0.99962 | ||

| One tail for H excess: | P = 0.00005 | P = 0.00008 | P = 0.00050 | |||

| Two tails for H excess and deficiency | P = 0.00009 | P = 0.00015 | P = 0.00101 | |||

| NWPZ | ST | Number of loci with heterozygosity excess expected | 6.01 | 6.44 | 6.81 | Shifted |

| Loci with heterozygosity deficiency or excess | 1/14(P = 0.00003) | 1/14 (P = 0.00006) | 1/14 (P = 0.00014) | |||

| SDT | T2 values (probability) | 5.703 (P = 0.00000) | 5.161 (P = 0.00000) | 4.728 (P = 0.00000) | ||

| WT | One tail for H deficiency | P = 0.99998 | P = 0.99998 | P = 0.99998 | ||

| One tail for H excess: | P = 0.00003 | P = 0.00003 | P = 0.00003 | |||

| Two tails for H excess and deficiency | P = 0.00006 | P = 0.00006 | P = 0.00006 |

CZ, Central zone; NEPZ, North East Plain zone; NHZ, North Hill zone; NWPZ, North Western Plain zone; ST, Sign rank Test; SDT, Standardized Differences Test; WT, Wilcoxon Test; IAM, Infinite allele model; TPM, Two Phase Model; SMM, Stepwise Mutation Model of Evolution.

Probability of deviation from mutation-drift equilibrium (H>HEQ) was determined according to Cornuet and Luikart (1996).

The bottleneck analysis supported for the non-existence of any bottleneck in UST populations in recent past. The concept of heterozygosity excess works on the principle that the observed gene diversity is higher than the expected equilibrium gene diversity (Heq) in a recently bottlenecked population (Table 8). In CZ population, sign rank test under IAM mutation model, expected number of loci with heterozygotic excess was 6.35 while the observed number of loci with heterozygosity excess was 13 (Table 8). The expected and observed loci with heterozygosity excess calculated by using TPM and SMM models were 6.86 and 7.22, respectively. Similarly, the outcome for IAM, TPM, and SMM supported the absence of any bottleneck in CZ population. Similar trends were also observed for NHZ, NEPZ, and NWPZ population using TPM and SMM. Although, one locus with heterozygosity deficiency (P = 0.00002) was also observed in NEPZ population using IAM model. The SDT provided the T2 statistics equal to 4.024, 3.492, and 3.168 for IAM, TPM, and SMM, respectively in CZ population. The probability values were significant for IAM (P = 0.00003), SMM (p = 0.00024), and TPM (P = 0.00077). Thus, null hypothesis was accepted by all the models. The probability values with WT for one tail for H excess under three models IAM (p = 0.00006), TPM (p = 0.00009), and SMM (p = 0.00015) indicated acceptance of null hypothesis under all the models in CZ population. Thus, all the three tests (ST, SDT, and WT) indicated the acceptance of mutation drift equilibrium (P > 0.05) in UST populations under all the mutation models for all CZ, NHZ, NEPZ, and NWPZ populations. Another powerful test of qualitative graphical method based on the allele frequency spectra detected a normal L-shaped curve, where the alleles with the lowest frequencies (0.03–0.3) were found to be most abundant in the entire wheat growing zones (Figure S2).

Discussion

Loose smut is a monocyclic internally seed borne disease. The seed borne inocula leads to long distance rapid spread of the disease across the entire wheat growing zones of India. The Ustilago segetum tritici isolates were collected from four major wheat growing zones (NWPZ, NEPZ, CZ, and NHZ) of India. The genetic structure was analyzed by performing RPB2 gene sequence comparison and fingerprinting with newly developed SSR markers. The degree of nucleotide difference in the RPB2 region in UST populations is low. It may be due to action of concerted evolution leads to homogenizing effect. Furthermore, evidence of recombination (Rm = 0) in entire UST population was not detected.

The low but significant Fst values (< 0.01 and < 0.05) and pair wise population differentiation among UST population from different zones indicate low genetic differentiation in the total populations (Fst = 0.012). The UST populations appear either of common origin or limited distribution, reproduces predominantly by asexual means, or experience substantial gene flow (from CZ to NHZ and NEPZ and later from NEPZ to NWPZ and NHZ) coupled with genetic drift. However in populations where mutation rates are high, Fst tends to fall back to zero (in case of CZ) as novel alleles are added to the population (Onaga et al., 2015). This happened because of negative dependence of Fst on diversity (Charlesworth et al., 1997) and has been reported in several pathogens; even in the absence of asexual reproduction (Couch et al., 2005). To outwit this prejudice due to mutation rates, FST has been compared with other genetic diversity indices. Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) showed that 91% of the total variation was due to differences among isolates within populations and the variation among populations reflected only 1% of the total variation. A low degree of differentiation among UST populations may be due to admixture among isolates from the different geographic regions. These results are also unswerving with the low Shannon's indices (0.531–0.589). The overall Shannon's index (I = 0.552) suggests that more than 50% of the genetic diversity explained by the differences between isolates. Therefore, all these results conclude that most of the genetic variation (91%) was distributed among isolates across the regions. The similar findings have been earlier reports in Ustilago maydis (Valverde et al., 2000), Mycosphaerella graminicola (Boeger et al., 1993), Phytophthora infestans (Goodwin et al., 1994), Rhynchosporium secalis (McDonald et al., 1999), and Rhizoctonia solani (Goswami et al., 2017) while analyzing their populations structure. It is worth mention here that the fungal isolates are mostly similar at the genetic level despite long distances among different wheat growing zones in India.

Haplotype analysis performed in present study provides information on the number of haplotypes (h), their frequency and diversity, and genetic distances within and between RPB2 gene sequence. The Hd can range from zero to 1.0, which means no diversity to high levels of haplotype diversity (Nei and Tajima, 1981). In present study, Hd (0.104–0.473) values indicated low to moderate levels of diversity in different wheat growing zones. NWPZ revealed the maximum diversity based on the number of haplotypes (i.e., 51 haplotypes from 56 UST isolates). Few haplotypes were shared among different populations indicating role of asexual reproduction and long-distance dispersal. Contrary to this, sexual reproduction occurs at the site of infection on the spike, was apparently prevalent in Indian wheat growing areas. Besides this, two other reasons may explain the genetic variability among isolates, first there might be possibility of multiple founder populations that result in the admixture of populations. Secondly, population genetic expansion may took place due to the accumulation of different alleles in UST populations as evident from the total and shared mutations noticed in the presents study. All these are agreeable, as evidenced by the high levels of population admixture identified in Structure analysis. Mutation generates diverse regional populations of UST, creating a pool of mutants from which new, virulent isolates can emerge. Many haplotypes were shared among these populations supports multiple introductions of the same haplotype, which could be due to pronounced asexual reproductive phase, as the case with UST. Furthermore, the analysis revealed that all UST populations are admixed and contain haplotypes from multiple populations within a region or between the regions.

To investigate the role of evolutionary forces on UST population, different neutrality test statistics (Tajima's D, Fu and Li's D* and F*, and Fu's Fs) were performed to examine the RPB2 sequence data for departure from neutrality. Significant and negative Tajima's D test statistics indicated that RPB2 locus is experiencing population bottlenecks, where the population is largely uniform and only a few sequences compose the new population. The biology of UST and its colonization could serve as a source of population bottlenecks. Similarly, significant and negative value of almost all D* and F* test statistics showed strong purifying selection. Overall, the RPB2 gene data displayed genetic divergence in the structure of the population among the four wheat growing zones analyzed and well-supported by the results from microsatellite loci. Moreover, 16 newly developed SSR markers used were polymorphic on all of the UST isolates. These results are comparable to earlier reports on SSR markers developed for other plant pathogens (Yang and Zhong, 2008; Pouzeshimiab et al., 2014). Thus, these SSR markers could be useful tool to study the population biology and genetics of this fungus at global level.

The loose smut fungus is carried as dormant mycelium within healthy appearing seed and is spread by growing infected seed. Moreover, teliospores are easily shaken from the smutted heads and may be carried for long distances by wind, insects, or other agencies (Ram and Singh, 2004). The low differentiation among regions (8% of total variation) detected on the basis of microsatellites can be explained by different ways. Firstly, the level of gene flow (Nm) is sufficient to maintain genetic similarity. The low levels of population differentiation were observed in corresponding high values of Nm. Nm is >1, reveals little differentiation among populations, and under such circumstances migration is more important than genetic drift (McDermott and McDonald, 1993). Theoretically, average gene flow value (Nm = 21) indicates that 21 isolates would need to be exchanged each generation among populations of different regions to achieve current degree of similarity. Highest gene flow was recorded between the CZ and NHZ (Nm = 29.131) populations. Regular gene flow and random mating among isolates from various populations could result in new pathotypes with improved pathological and biological fitness traits (Mishra et al., 2006). Besides this, inbreeding coefficient (Fit = 0.090) indicated little genetic differentiation across UST populations. The corroborating results were also observed in American populations of P. nodorum (Fst = 0.004; Stukenbrock et al., 2006), North American population of Mycosphaerella graminicola (Fst = 0.08) (Zhan et al., 2003) and Septoria musiva populations (Fst = 0.20) in north-central and northeastern North America (Feau et al., 2005). In UST populations, SSR data provided no discrete clustering in different populations on the basis of structure analysis and little among-populations variance (8%) was observed in AMOVA. Therefore, no specific demarcation of genetic grouping was noticed, and results further suggest large and widespread populations with high migration rates facilitated by wind-dispersed teliospores and frequent exchange and long distance transport of infected seed material in different wheat growing zones.

In present study, the plausible reasons leading to the structuration of the regional collection were not elucidated since no clear main direction of gene flow among the sampled sites, and no significant isolation by distance (P = 0.49; > 0.05) were observed. The genetic identities of the four populations evaluated in present study were close to 1. The moderate Gst (−0.0678) values indicated weak genetic differentiation and minimal geographic clustering among the populations from four different zones and yielded average Nm values 6.875 across all loci and populations, suggesting that the level of gene flow was approximately seven times greater than that needed to prevent populations from diverging by genetic drift. Moreover, absence of private alleles in all the four zone population may indicate that the observed migration levels reflect gene flow. The wind direction in India is generally from North West to North East during the wheat cropping season. This may cause migration and gene flow between populations lead to admixture among isolates from the diverse geographic origin as observed in present study. The pathogen is cosmopolitan in distribution, and telisopores are known to be disseminated over long distances by wind (Ram and Singh, 2004). Besides this, long-distance gene flow in UST was man mediated, and subsequent natural gene flow gradually reduced the isolation by distance.

Mutation is the main evolutionary mechanism that generates polymorphisms, and its implications to disease management are well-known (Jolley et al., 2005). For UST, point mutations (4 mutations) in the sequence of the RPB2 gene resulted in the introduced of new alleles in the population. Similar observations have been documented by Lourenço et al. (2009), while studying the molecular diversity and evolutionary processes of Alternaria solani, a seed borne pathogen in Brazil inferred using genealogical and coalescent approaches. However, the relatively low number of singleton mutation estimated in present study for RPB2 locus in different wheat growing zones does not signify low mutation rate in whole genome. Therefore, authors felt that the evaluation of other housekeeping genes or genomic regions should be analyzed for more accurate quantification of mutation occurrence in UST populations. Further, bottleneck analysis based on three models (IAM, TPM and SMM) indicated that the observed heterozygosity excess (He) found less than the expected excess heterozygosity (Hee) in all the four wheat growing zones. Thus, the lower magnitude of He with their respective Hee reflect absence of genetic bottleneck in UST populations. Further, the negative TD-value of the UST population indicates that the UST population is undergoing demographic expansion. Further support for this hypothesis is gained from lack of private alleles in UST populations collected from all wheat growing zones.

The knowledge of population genetic structure of a pathogen provides information on its potential to overcome host genetic resistance (McDonald and Linde, 2002). The results of present study showed that UST have a clonal genetic structure with limited differentiation between populations. It means variability is mainly contributed by mutation and recombination is uncommon. Therefore, wheat disease management measures, such as replacement of infected seed and fungicide-treated seeds, could help to reduce UST severity and limit gene flow. Host resistance is also economical and effective to manage loose smut of wheat (Singh, 2018), and breeding efforts in different wheat growing zones have put emphasis on exploration of more resistance sources and other gene pools to fill this gap. In addition, screening of germplasm and breeding material against genetically diverse isolates needs to be emphasized to develop durable and effective resistance cultivars. In nutshell, the current study presents a first stab to comprehend the genetic variation within and among populations of UST causing loose smut in different wheat growing regions. The results highlight that microsatellite markers can be used to analyze genotypic and genetic diversity of populations of UST.

Author Contributions

The work was conceived and designed by PK and SK. The sampling survey was performed by PK, SK, PJ, and DS. Experiments were conducted by RT, PK, and RK. Data analysis was done by PJ and RT. The manuscript was drafted by PK and SK. The final editing and proofing of manuscript was done by DS and GS. RK and RT contributed equally. The manuscript was approved by all the authors.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are highly thankful to Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) for proving research grant under the institute research project Management of major diseases and insect pests of wheat in an agro-ecological approach under climate change (CRSCIIWBRSIL201500500186). We also grateful to ICAR-National Bureau of Agriculturally Important Microorganisms (NBAIM) for providing necessary financial support under AMAAS project on Development of diagnostic tools for detection of Karnal bunt and loose smut of wheat (Project Code 1002588).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01072/full#supplementary-material

References

- Agapow P. M., Burt A. (2001). Indices of multilocus linkage disequilibrium. Mol. Ecol. Notes 1, 101–102. 10.1046/j.1471-8278.2000.00014.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadpour A., Castell-Miller C., Javan-Nikkhah M., Naghavi M. R., Dehkaei F. P., Leng Y., et al. (2018). Population structure, genetic diversity, and sexual state of the rice brown spot pathogen Bipolaris oryzae from three Asian countries. Plant Pathol. 67, 181–192. 10.1111/ppa.12714 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins I. M., Hansing E. D., Bever W. M. (1943). Reaction of some varieties and strains of winter wheat to artificial inoculation of loose smut. Agron J. 35,197–204. 10.2134/agronj1943.00021962003500030003x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey K. L., Gossen B. D., Gugel R. K., Morrall R. A. (2003). Diseases of Field Crops in Canada. 3rd Edn. Winnipeg: The Canadian Phytopathological Society, 290. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett R. S., Milgroom M. G., Bergstrom G. C. (2005). Population structure of seedborne Phaeosphaeria nodorum on New York wheat. Phytopathology 95, 300–305. 10.1094/PHYTO-95-0300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeger J. M., Chen R. S., McDonald B. A. (1993). Gene flow between populations of Mycosphaerella graminicola (Anamorph Septoria tritici) detected with restriction fragment length polymorphism markers. Phytopathology 83, 1148–1154. 10.1094/Phyto-83-1148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonne C. (1941). A contribution to the control of wheat loose smut: studies on the hot water short disinfection process. Angewandite Botanik 23, 304–341. [Google Scholar]

- Bouajila A., Abang M. M., Haouas S., Udupa S., Rezgui S., Baum M., et al. (2007). Genetic diversity of Rhynchosporium secalis in Tunisia as revealed by pathotype, AFLP, and microsatellite analyses. Mycopathologia 163, 281–294 10.1007/s11046-007-9012-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B., Nordborg M., Charlesworth D. (1997). The effects of local selection, balanced polymorphism and background selection on equilibrium patterns of genetic diversity in subdivided populations. Genet. Res. 70, 155–174. 10.1017/S0016672397002954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornuet J. M., Luikart G. (1996). Description and power analysis of two tests for detecting recent population bottlenecks from allele frequency data. Genetics 144, 2001–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couch B. C., Fudal I., Lebrun M.-H., Tharreau D., Valent B., van Kim P., et al. (2005). Origins of host-specific populations of the blast pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae in crop domestication with subsequent expansion of pandemic clones on rice and weeds of rice. Genetics 170, 613–630. 10.1534/genetics.105.041780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean W. J. (1964). Some effects of temperature and humidity on loose smut of wheat. (PhD thesis). University of Nottingham, Nottingham. [Google Scholar]

- Earl D. A., vonHoldt B. M. (2012). STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 4, 359–361. 10.1007/s12686-011-9548-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellegren H. (2004). Microsatellites: simple sequences with complex evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5, 435–445. 10.1038/nrg1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanno G., Regnaut S., Goudet J. (2005). Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the softwareSTRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 14, 2611–2620. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feau N., Hamelin R. C., Vandecasteele C., Stanosz G. R., Bernier L. (2005). Genetic structure of Mycosphaerella populorum (anamorph Septoria musiva) populations in north-central and northeastern North America. Phytopathology 95, 608–616. 10.1094/PHYTO-95-0608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin S. B., Cohen B. A., Fry W.E. (1994). Pan global distribution of a single clonal lineage of the Irish potato famine fungus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 11591–11595. 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami S. K., Singh V., Kashyap P. L. (2017). Population genetic structure of Rhizoctonia solani AG1IA from rice field in North India. Phytoparasitica 45, 299–316. 10.1007/s12600-017-0600-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green G. J., Nielsen J. J., Cherewick W. J., and D. J., Samborski (1968). The experimental approach in assessing disease losses in cereals: rusts and smuts. Can. Plant Dis. Surv. 48, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Jolley K. A., Wilson D. J., Kriz P., McVean G., Maiden M. C. (2005). The influence of mutation, recombination, population history, and selection on patterns of genetic diversity in Neisseria meningitidi. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 562–569. 10.1093/molbev/msi041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P. (1999). Control of loose smut (Ustilago nuda and U. tritici) infections in barley and wheat by foliar applications of systemic fungicides. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 105, 729–732. 10.1023/A:1008733628282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi L. M., Srivastava K. D., Singh D. V. (1980). Wheat disease newsletter. Indian Agric. Res. Inst. 13,112–113. [Google Scholar]

- Karwasra S. S., Mukherjee A. K., Swain S. C., Mohapatra T., Sharma R. P. (2002). Evaluation of RAPD, ISSR and AFLP markers for characterization of the loose smut fungus Ustilago tritici. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2, 99–103. 10.1007/BF03263143 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap P. L., Rai S., Kumar S., Srivastava A. K. (2016). Genetic diversity, mating types and phylogenetic analysis of Indian races of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris from chickpea. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 49, 533–553. 10.1080/03235408.2016.1243024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap P. L., Rai S., Kumar S., Srivastava A. K., Anandaraj M., Sharma A. K. (2015). Mating type genes and genetic markers to decipher intraspecific variability among Fusarium udum isolates from pigeonpea. J. Basic Microbiol. 55, 846–856. 10.1002/jobm.201400483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassa M. T., Menzies J. G., McCartney C. A. (2015). Mapping of a resistance gene to loose smut (Ustilago tritici) from the Canadian wheat breeding line BW278. Mol. Breed. 35:180 10.1007/s11032-015-0369-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur G., Sharma I., Sharma R. C. (2014). Characterization of Ustilago segetum tritici causing loose smut of wheat in northwestern India. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 36, 360–366. 10.1080/07060661.2014.924559 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. (1980). A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16, 111–120. 10.1007/BF01731581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox R. E., Campbell H. L., Clarke F. R., Menzies J. G., Popovic Z., Procunier J. D., et al. (2014). Quantitative trait loci for resistance in wheat (Triticum aestivum) to Ustilago tritici. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 36, 187–201. 10.1080/07060661.2014.905497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krimitzas A., Pyrri I., Kouvelis V. N., Kapsanaki-Gotsi E., Typas M. A. (2013). A phylogenetic analysis of greek isolates of Aspergillus species based on morphology and nuclear and mitochondrial gene sequences. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013:260395. 10.1155/2013/260395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse J., Mishra B., Choi Y.-J., Sharma R., Thines M. (2017). New smut-specific primers for multilocus genotyping and phylogenetics of Ustilaginaceae. Mycol. Progr. 16, 917–925. 10.1007/s11557-017-1328-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Knox R. E., Singh A. K., DePauw R. M., Campbell H. L., Isidro-Sanchez J., et al. (2018). High-density genetic mapping of a major QTL for resistance to multiple races of loose smut in a tetraploid wheat cross. PLoS ONE 13:0192261. 10.1371/journal.pone.0192261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Rai S., Maurya D. K., Kashyap P. L., Srivastava A. K., Anandaraj M. (2013a). Cross-species transferability of microsatellite markers from Fusarium oxysporum for the assessment of genetic diversity in Fusarium udum. Phytoparasitica 41, 615–622. 10.1007/s12600-013-0324-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Singh R., Kashyap P. L., Srivastava A. K. (2013b). Rapid detection and quantification of Alternaria solani in tomato. Sci. Hort. 151, 184–189. 10.1016/j.scienta.2012.12.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. (2016). MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço V., Jr., Moya A., González-Candelas F., Carbone I., Maffia L. A., Mizubuti E. S., et al. (2009). Molecular diversity and evolutionary processes of Alternaria solani in Brazil inferred using genealogical and coalescent approaches. Phytopathology 99, 765–774. 10.1094/PHYTO-99-6-0765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheny P. B., Wang Z., Binder M., Curtis J. M., Lim Y. W., Nilsson R. H., et al. (2007). Contributions of rpb2 and tef1 to the phylogeny of mushrooms and allies (Basidiomycota, Fungi). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 43, 30–51. 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott J. M., McDonald B. A. (1993). Gene flow in plant pathosystems. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 31, 53–373. 10.1146/annurev.py.31.090193.00203318643761 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald B. A., Zhan J., Burdon J. J. (1999). Genetic Structure of Rhynchosporium secalis in Australia. Phytopathology 89, 639–645. 10.1094/PHYTO.1999.89.8.639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald B. A., Linde C. (2002). Pathogen population genetics evolutionary potential and durable resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 40, 349–379. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.40.120501.101443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies J. G., Turkington T. K., Knox R. E. (2009). Testing for resistance to smut diseases of barley, oats and wheat in western Canada. Can. J. Plant. Pathol. 31, 265–279. 10.1080/07060660909507601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra P. K., Tewari J. P., Clear R. M., Turkington T. K. (2006). Genetic diversity and recombination within populations of Fusarium pseudograminearum from western Canada. Int. Microbiol. 9, 65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M., Tajima F. (1981). Genetic drift and estimation of effective population size. Genetics. 98, 625–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen J., Thomas P. (1996). Loose smut, in Bunt and Smut Diseases of Wheat: Concepts and Methods of Disease Management. eds Wilcoxson RD, Saari EE. Mexico City DF: CIMMYT, 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Onaga G., Wydra K., Koopmann B., Sér,é Y., von Tiedemann A. (2015). Population Structure, pathogenicity, and mating type distribution of Magnaporthe oryzae isolates from East Africa. Phytopathology 105, 1137–1145. 10.1094/PHYTO-10-14-0281-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peakall R., Smouse P. E. (2012). GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research–an update. Bioinformatics 28, 2537–2539. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piry S., Luikart G., Cornuet J. M. (1999). BOTTLENECK: a computer program for detecting recent reductions in the effective population size using allele frequency data. J. Hered. 90, 502–503. 10.1093/jhered/90.4.502 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pouzeshimiab B., Razavi M., Zamanizadeh H. R., Zare R., Rezaee S. (2014). Assessment of genotypic diversity among Fusarium culmorum populations on wheat in Iran. Phytopathol Mediterr. 53, 300–310. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad P., Bhardwaj S. C., Savadi S., Kashyap P. L., Gangwar O. P., Khan H., et al. (2018). Population distribution and differentiation of Puccinia graminis tritici detected in the Indian subcontinent during 2009–2015. Crop Prot. 108, 128–136 10.1016/j.cropro.2018.02.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard J. K., Stephens M., Donnelly P. (2000). Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quijano C. D., Wichmann F., Schlaich T., Fammartino A., et al. (2016). KP4 to control Ustilago tritici in wheat: enhanced greenhouse resistance to loose smut and changes in transcript abundance of pathogen related genes in infected KP4 plants. Biotechnol. Rep. 11, 90–98. 10.1016/j.btre.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raja H. A., Miller A. N., Pearce C. J., Oberlies N. H. (2017). Fungal Identification using molecular tools: a primer for the natural products research community. J. Nat. Prod. 80, 756–770. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b01085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram B., Singh K. P. (2004). Smuts of wheat: a review. Ind. Phytopath 57, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Randhawa H. S., Popovic Z., Menzies J., Knox R., Fox S. (2009). Genetics and identification of molecular markers linked to resistance to loose smut (Ustilago tritici) race T33 in durum wheat. Euphytica 169, 151–157. 10.1007/s10681-009-9903-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf F. J. (2002). Geometric morphometrics and phylogeny, in Morphology, Shape and Phylogeny, 175–193. [Google Scholar]