Microbial competition is most often studied at the genus or species level, but interstrain competition has been less thoroughly examined. Klebsiella pneumoniae is an important pathogen in the context of hospital-acquired pneumonia, and a better understanding of strain competition in the lungs could explain why some strains of this bacterium are more frequently isolated from pneumonia patients than others.

KEYWORDS: Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, competition, pneumonia

ABSTRACT

Microbial competition is most often studied at the genus or species level, but interstrain competition has been less thoroughly examined. Klebsiella pneumoniae is an important pathogen in the context of hospital-acquired pneumonia, and a better understanding of strain competition in the lungs could explain why some strains of this bacterium are more frequently isolated from pneumonia patients than others. We developed a barcode-free method called “StrainSeq” to simultaneously track the abundances of 10 K. pneumoniae strains in a murine pneumonia model. We demonstrate that one strain (KPPR1) repeatedly achieved a marked numerical dominance at 20 h postinoculation during pneumonia but did not exhibit a similar level of dominance in in vitro mixed-growth experiments. The emergence of a single dominant strain was also observed with a second respiratory pathogen, Acinetobacter baumannii, indicating that the phenomenon was not unique to K. pneumoniae. When KPPR1 was removed from the inoculum, a second strain emerged to achieve high numbers in the lungs, and when KPPR1 was introduced into the lungs 1 h after the other nine strains, it no longer exhibited a dominant phenotype. Our findings indicate that certain strains of K. pneumoniae have the ability to outcompete others in the pulmonary environment and cause severe pneumonia and that a similar phenomenon occurs with A. baumannii. In the context of the pulmonary microbiome, interstrain competitive fitness may be another factor that influences the success and spread of certain lineages of these hospital-acquired respiratory pathogens.

INTRODUCTION

Bacteria are ubiquitous, and the success of a bacterial lineage within a given niche frequently depends upon its ability to successfully compete with other microbes that are present. Infection of the human lung in the context of pneumonia is no exception. The lung environment, once thought to be sterile, is now recognized to be an intricate ecosystem balancing the healthy lung microbiome with continuous threats by invading microbial communities through salivary microaspirations and inhalation (1–8). Recent advances in whole-genome sequencing have uncovered dynamic bacterial population shifts in the lung as infection is established (2, 5, 7–9).

Recent molecular studies of the pulmonary microbiome in mechanically ventilated patients have supported an ecological model for the development of ventilator-associated pneumonia (5, 9, 10). Populations of aerobic Gram-negative bacilli and other pathogenic bacteria frequently colonize the upper airways of hospitalized patients (11–13). Upon intubation for mechanical ventilation, these bacteria access the lower respiratory tract (14, 15), and multiple genera of pathogenic bacteria can be observed in the lungs of patients without overt infection (16). Over time, the diversity of the pulmonary microbiome decreases (16) until one particular pathogenic bacterial lineage outcompetes the others to become the dominant member of the population (10). This dysbiosis leads to the signs and symptoms of pneumonia (5, 10, 17). Pathogen population dynamics have most often been examined at the genus or species level (18, 19); however, little is known about competition at the level of individual strains within a species. Accordingly, we developed a genomic method to identify strain population dynamics during mixed-strain pneumonias.

An important pathogen in the context of hospital-acquired pneumonia is Klebsiella pneumoniae. According to the National Healthcare Safety Network of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Klebsiella species are the third most common pathogens reported to cause health care-associated infections (20). Of particular concern are multidrug-resistant strains. Carbapenem-resistant and extended-spectrum-β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing K. pneumoniae strains are listed as urgent and serious threats, respectively, by the CDC (21). In addition, the World Health Organization (WHO) has identified antibiotic-resistant K. pneumoniae as a “priority pathogen” (22). Some K. pneumoniae isolates have even developed resistance to last-line antibiotics such as colistin (23), causing concerns for a “postantibiotic era” in which these bacteria are untreatable (24). A better understanding of how K. pneumoniae establishes itself in the initial stages of infection may allow early interventions that prevent progression to severe and refractory disease.

K. pneumoniae is a genetically diverse species. A recent study found over 150 distinct phylogenetic lineages of this pathogen and suggested that more remain to be identified (25). Many of these lineages can be found within a single hospital (26, 27) and even within an individual patient (28), yet genotyping studies indicate that a relatively small number of lineages are responsible for a disproportionately large number of pneumonia cases (25, 29–31). For example, multilocus sequence typing has indicated that sequence type 11 (ST11), ST14, ST15, ST42, ST43, ST258, ST340, ST416, and ST512 strains are frequent causes of pneumonia over large geographic regions (25). Many factors may contribute to the overrepresentation of these lineages in pneumonia, such as selection resulting from antibiotic resistance (32), an enhanced ability to counteract innate immune defenses in the lungs (33), prolonged survival on inanimate surfaces (34), enhanced transmissibility (35), or relative abundance in environmental and human reservoirs (36, 37). However, another contributing factor may be that some lineages of K. pneumoniae are capable of outcompeting other lineages in the respiratory tract. While microbial competition during infection has been most often examined at the genus or species level (18, 19), interstrain competition (e.g., competition between different lineages of the same species) has been documented with Streptococcus pneumoniae (38) and may also play an important role in dictating which K. pneumoniae lineages emerge to cause overt pneumonia.

Here, we examined the competition between strains of K. pneumoniae during the early stages of infection of the lower respiratory tract. To accomplish this, we developed a genomic method called “StrainSeq,” which obviates the need for barcoding and allows rapid quantification of strain populations during mixed-strain infections in the murine pneumonia model. We employed StrainSeq to examine the population dynamics of 10 K. pneumoniae strains inoculated together into the lungs of mice. We demonstrate that the same single strain of K. pneumoniae consistently emerged from this mixed inoculum to become the dominant strain in the lungs during infection. However, when this strain was excluded from the initial inoculum, dominance was achieved nonstochastically by another strain in the inoculum. We also substantiated our findings with another nosocomial pulmonary pathogen, Acinetobacter baumannii, which exhibited a dominant strain phenotype in mixed inocula comprised of six A. baumannii strains. These findings suggest that interstrain competition may be an important factor in dictating which lineages of K. pneumoniae or A. baumannii emerge to cause pneumonia.

RESULTS

A single strain of K. pneumoniae outcompetes other strains during early pneumonia.

Our goal was to examine the population dynamics of K. pneumoniae strains during early pneumonia. For this purpose, we chose 10 K. pneumoniae strains that had been previously cultured from a variety of body sites (Table 1). Prior to testing mixed-strain infections, we first determined the virulence of the 10 strains individually. We intranasally inoculated each strain by itself in a mouse model of acute pneumonia. The 10 strains varied over 6 logs in the CFU required to cause prelethal illness and exhibited a wide range of bacterial burdens 20 h following inoculation of this number of CFU into mice (Fig. 1). These findings indicated that this cohort contained K. pneumoniae strains with a large range of virulence potentials.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this studyb

| Strain | Relevant characteristic, multilocus sequence type, and source(s) of isolation | Reference or source, ATCC designation or GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|

| K. pneumoniae | ||

| KPPR1 | Laboratory strain, ST493 | 64, ATCC 43816 |

| hvKP1 | Clinical isolate, ST86, blood | 65, AOIZ00000000 |

| hvKP4 | Clinical isolate, UD, blood and liver abscess | 66, QAUY00000000a |

| OC743 | Clinical isolate, ST13, urine | NMH, QBCF00000000a |

| OC951 | Clinical isolate, ST15, sputum | NMH, QBCE00000000a |

| S009 | Clinical isolate, ST3449, blood | NMH, QBCD00000000a |

| Z4147 | Clinical isolate, ST17, blood | NMH, QBCC00000000a |

| Z4149 | Clinical isolate, ST874, rectal swab | NMH, QBCB00000000a |

| Z4157 | Clinical isolate, ST1425, rectal swab | NMH, QBCA00000000a |

| Z4174 | Clinical isolate, ST584, urine | NMH, QBBZ00000000a |

| A. baumannii | ||

| ATCC 17978 | Laboratory strain, ND | 67, ATCC 17978 |

| ABBL004 | Clinical isolate, ND, blood | 68, LLCK00000000 |

| ABBL040 | Clinical isolate, ND, blood | 68, LLDU00000000 |

| ABBL079 | Clinical isolate, ND, blood | 68, LLGJ00000000 |

| ABBL105 | Clinical isolate, ND, blood | 68, LLHE00000000 |

| ABBL110 | Clinical isolate, ND, blood | 68, LLHI00000000 |

| E. coli | ||

| One Shot Top10 | Chemically competent plasmid propagation | Invitrogen |

This whole-genome shotgun project has been deposited at the DDBJ/ENA/GenBank database under accession no. QXXX00000000 (where "XXX" are placeholders). The version described in this manuscript is version QXXX01000000.

NMH, Northwestern Memorial Hospital; UD, undefined; ND, not determined.

FIG 1.

The 10 K. pneumoniae isolates exhibit various degrees of virulence. (A) Mice were infected with various inocula of K. pneumoniae isolates to estimate a dose that caused prelethal illness in ∼50% of mice over 14 days (modified 50% lethal dose [mLD50]). Mouse numbers and data used to calculate mLD50 values are included in Table S1 in the supplemental material. (B) Bacterial burdens in mouse lungs resulting from infections with each K. pneumoniae isolate’s respective mLD50 were enumerated at 20 h postinfection (n = 5 mice per infection group). Statistical significance was determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons (***, P < 0.001).

We next sought to examine competition between bacterial lineages during early pneumonia. To accomplish this, we needed a technique that could distinguish one bacterial strain from another in mouse lungs. Although barcoding has been used successfully for this purpose, the required genetic manipulations are time-consuming, and additional genetic manipulations are needed each time new strains are added to the analysis. To overcome these difficulties, we developed an approach called StrainSeq, in which genomic sequences unique to a particular strain are used as “endogenous barcodes” to distinguish this strain from others in a mixed sample (Fig. 2). In StrainSeq, approximately equal CFU of individual bacterial strains are mixed together and divided into two aliquots. DNA is extracted from the first aliquot to analyze the “input pool.” The second aliquot is inoculated into mice; at a later time point, the mice are euthanized, and the infected organs are removed. DNA is purified from the infected organs and enriched for prokaryotic DNA. This DNA is designated the “output pool.” The input and output pools are sequenced, and the read numbers of the endogenous barcodes are used to estimate the relative abundance of bacteria of each strain within the input and within the output pools. Read numbers are corrected for differences in the size of unique accessory sequences and the depth of the sequencing run (see Materials and Methods for details). The ratio of a strain’s relative abundance in the output pool divided by its relative abundance in the input pool is designated the “StrainSeq index.” Strains that increase in number following infection relative to others in the inoculum will have StrainSeq indices greater than 1; conversely, StrainSeq indices of less than 1 indicate strains that are at a competitive disadvantage during infection relative to others in the inoculum.

FIG 2.

Overview of StrainSeq workflow. (A) Whole-genome strain sequences were aligned, and strain-specific accessory sequences were identified (colored). Each line represents the genome of a different strain. (B) Mixed-strain inocula composed of equal CFU of each strain were intranasally inoculated into mice. (C) Output DNA was extracted from infected mouse lungs and enriched for prokaryotic DNA. (D) Input and output DNA samples were sequenced using an Illumina platform to generate 300-bp sequence reads. (E) Sequence reads were aligned to strain-specific accessory sequences and enumerated in input and output samples. (F) StrainSeq data were represented as the ratio of the proportion of normalized read counts in the output sample to the proportion of normalized read counts in the input sample for each strain to yield a StrainSeq index. Each experimental group is annotated by a species abbreviation (“Kp” for K. pneumoniae), the number of strains in a mixed inoculum (“3”), and a letter to indicate the replicate experiment (“a” or “b,” etc.). (Left) Each experimental result (a or b, etc.) is derived from sequence data pooled from 8 to 10 mice. (Right) In some cases, the means and standard deviations of the results of different experiments (a or b, etc.) are shown. NGS, next-generation sequencing.

We used StrainSeq to examine whether certain K. pneumoniae strains could outcompete others during early pneumonia. The 10 K. pneumoniae strains were pooled and inoculated intranasally into 8 to 10 mice per experiment. At 20 h postinfection, the mice were euthanized, and their lungs were removed. DNA was extracted from the lungs, pooled, processed, and sequenced using an Illumina MiSeq platform. This information was used to calculate a StrainSeq index for each of the 10 strains. Strain KPPR1 exhibited an average StrainSeq index of 8.9 (ranging from 8.56 to 9.27) over three repeat experiments, indicating that it had achieved much higher numbers in the lung than the other nine strains (Fig. 3). The remaining nine strains had average StrainSeq indices of between 0.44 and 0.76, indicating that KPPR1 outcompeted each of these strains to a large degree. These results indicated that KPPR1 outcompeted other K. pneumoniae strains in the lungs during early pneumonia. Here, we refer to the phenomenon in which one bacterial strain achieves a large numerical superiority over others in a mixed infection as “strain dominance.”

FIG 3.

A dominant Klebsiella pneumoniae strain population emerges in vivo. Bacterial DNA was isolated from mice 20 h after infection with mixed inocula of K. pneumoniae strains. Each value was obtained by pooling samples from 8 to 10 mice. Results of three individual experiments are shown to convey experimental reproducibility. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test (****, P < 0.0001).

We next examined whether the in vivo strain dominance was an artifact of the StrainSeq approach. Since StrainSeq is based on numbers of DNA sequences, it is conceivable that it is biased by dead bacteria and does not reflect the true number of viable bacteria in the lungs. To test StrainSeq’s accuracy in enumerating bacterial numbers during infection, we utilized a KPPR1 strain that was tagged with an apramycin (Apra) resistance cassette inserted into a noncoding region near the Tn7 insertion site. We also verified that the remaining nine strains were susceptible to apramycin. Mice were infected with a mixed-strain inoculum identical to that in the StrainSeq experiments described above except that KPPR1 was replaced with apramycin-tagged KPPR1. Bacterial populations were enumerated in the inoculum and in the lungs of infected mice after 20 h of infection by traditional plating methods and concurrent StrainSeq analysis. Both colony-based and StrainSeq results were pooled and normalized in the same manner, as described above for the StrainSeq analyses. Both the StrainSeq and colony enumeration methods indicated equivalent strain dominance by the KPPR1 strain (Fig. 4A). Comparable numbers of KPPR1 bacteria were recovered from the lungs of each infected mouse before pooling (Fig. 4B), indicating that the results were not biased by exceedingly high numbers of KPPR1 bacteria in a few mice. These findings indicated that StrainSeq accurately measured the relative proportions of K. pneumoniae strains in the lungs.

FIG 4.

StrainSeq results are similar to those obtained using a colony-based approach. K. pneumoniae strain KPPR1 was marked with an apramycin resistance cassette to generate KPPR1::Aprar, and relative numbers of KPPR1::Aprar and a group of nine other K. pneumoniae strains in the lungs of mice were determined at 20 h postinfection. (A) For the culture-based approach, lung homogenates were plated on apramycin-containing medium and on nonselective medium to quantify KPPR1::Aprar and total bacterial numbers, respectively. (Left) K. pneumoniae burdens were normalized as the percentage of each bacterial population [KPPR1::Aprar or Kp(9)] in the lung at 20 h postinfection divided by the respective percentage of each bacterial population in the inoculum. (Right) The same samples were evaluated using the StrainSeq approach. (B) Bacterial burdens in the lungs of individual mice from panel A were normalized to the inoculum size. Each symbol represents data for a mouse, and bars represent means. Data represent cumulative results from two experiments, with 8 to 10 mice per experiment.

StrainSeq relies on the stability of accessory genome “barcodes” to enumerate strain populations. It was possible that the high StrainSeq index for KPPR1 was a result of a horizontal transfer of this strain’s endogenous barcodes to a different strain or of an excision from the chromosome of a high-copy-number plasmid, which would cause misleading results. To examine these possibilities, we compared the sequence read numbers per barcode accessory genomic element (AGE) in the output pool to that found in the input pool for each of the 10 strains. Our reasoning was that if a particular AGE was skewing the StrainSeq results, its read numbers should show an aberrant pattern relative to those of the other AGEs present in the same strain over the course of the experiment. Following mixed-strain growth in vitro, each unique AGE increased or decreased in proportion to other barcode AGEs within that strain (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These results suggested that single barcode AGEs were not changing in number relative to other AGEs within a strain during infection, as would be expected if horizontal transfer or plasmid excision events were occurring. We performed a similar analysis on KPPR1 from the above-described mixed infection in mice. The distribution of sequence reads from the output sample correlated with that from the input sample for KPPR1 during in vivo outgrowth with the nine other isolates (Fig. S2), indicating that the KPPR1 strain dominance was not an artifact of an overrepresentation of a single KPPR1-specific AGE during infection.

Dominance of a single strain in early pneumonia also occurs with Acinetobacter baumannii.

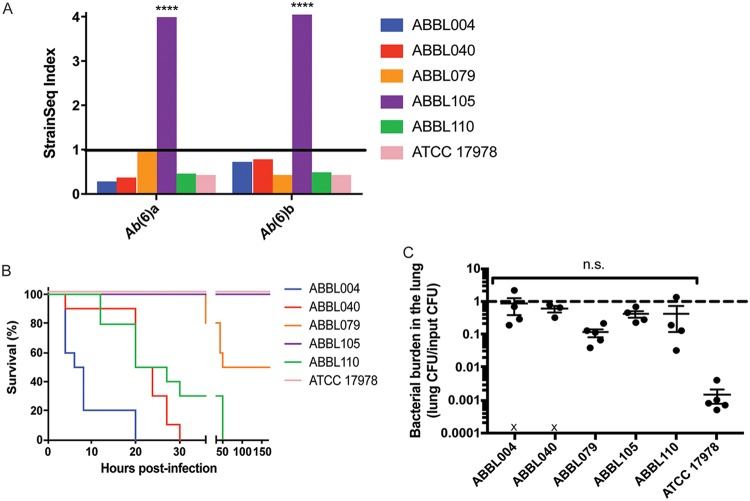

To examine whether the strain dominance phenomenon occurred in bacteria other than K. pneumoniae, mixed-strain infections were performed with another pulmonary pathogen of clinical relevance, A. baumannii. When mice were intranasally inoculated with six distinct strains of A. baumannii, a single strain, ABBL105, exhibited a dominant phenotype in the lungs of infected mice. ABBL105 exhibited an average StrainSeq index of 4.0 (ranging from 3.99 to 4.07) over repeat experiments, while the remaining isolates exhibited average StrainSeq indices of between 0.43 and 0.70 (Fig. 5A). When the six A. baumannii isolates were inoculated individually into mice, ABBL105 was not the most lethal strain (Fig. 5B), and other strains achieved the same bacterial burdens in the lung as ABBL105 after 20 h of infection (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that strain dominance is not unique to K. pneumoniae, and that it is not necessarily associated with strains that are the most virulent in single-strain infections, but that certain strains may exploit other strains in mixed inocula to gain dominance in the lungs.

FIG 5.

A dominant Acinetobacter baumannii strain population emerges in vivo. (A) Bacterial DNA was isolated from mice 20 h after infection with mixed inocula of A. baumannii strains. Each value was obtained by pooling samples from 8 to 10 mice. Results of two individual experiments are shown to convey experimental reproducibility. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test (****, P < 0.0001). (B) Mice were intranasally infected with A. baumannii isolates (4 × 106 CFU), and survival was monitored over 7 days. (C) Bacterial burdens in mouse lungs resulting from infections with A. baumannii strains (1 × 106 CFU) were enumerated at 20 h postinfection (n = 4 to 5 mice per infection group). An “X” indicates mouse mortality. Statistical significance was determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons (ns, not significant).

Dominance of a single strain does not occur in vitro.

We next examined whether in vivo strain dominance could be replicated in vitro. We reasoned that if this phenomenon was caused by direct bacterial interactions (e.g., contact-dependent inhibition or killing caused by type VI secretion), it should occur during growth in medium. We first demonstrated that each strain had similar growth rates when grown individually in rich medium (data not shown). StrainSeq was next performed on mixed cultures grown in rich medium in vitro. Since the total bacterial CFU recovered from a mouse lung after a 20-h StrainSeq experiment were equivalent to eight doublings of the initial inoculum, we allowed the mixed culture to grow in rich medium for 6 h, which is predicted to allow for approximately eight doublings. After this period of time, StrainSeq was performed. A dominant phenotype did not emerge in K. pneumoniae or A. baumannii cocultures, with average StrainSeq indices ranging from 0.51 to 1.16 and 0.64 to 1.19, respectively (Fig. 6A and B). We next extended in vitro growth to 15 generations (12 h). After 15 generations, there was greater variability in strain proportions in K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii cocultures, with StrainSeq indices ranging from 0.20 to 1.80 and 0.29 to 2.27, respectively (Fig. 6C and D). However, the StrainSeq indices of the dominant strains did not approach those observed in vivo. Thus, the strain dominance observed in the lungs was not the result of different growth characteristics in rich medium.

FIG 6.

Dominant strain populations do not emerge in vitro. (A and B) Strains of K. pneumoniae (A) or A. baumannii (B) were grown together in LB broth in vitro for 6 h (approximately 8 doublings), and StrainSeq analysis was performed. (C and D) The experiment was repeated using 12 h of growth (approximately 15 doublings).

KPPR1 achieves dominance after direct deposition in the lung.

KPPR1 may have achieved numerical dominance in the intranasal aspiration model of pneumonia by one of two mechanisms: (i) it may have been more efficiently aspirated from the nose to the lungs following deposition on the nares, such that a higher number of KPPR1 cells was present in the pulmonary space to initiate pneumonia, or (ii) it may have competitively outgrown the other strains after equivalent strain deposition in the lungs. To examine the first possibility, 30-min bacterial burdens were enumerated in single-strain K. pneumoniae infections. Significant differences in pulmonary bacterial burdens were not observed under these conditions (Fig. 7A). However, when mice were infected with mixed-strain K. pneumoniae inocula and StrainSeq analysis was performed at 30 min postinfection, KPPR1 exhibited an average StrainSeq index of 4.2 (Fig. 7B), while the next most prevalent isolate, Z4149, exhibited an average StrainSeq index of only 1.7. These results suggest that KPPR1’s dominance in the lungs at 30 min occurs only in the presence of the other K. pneumoniae strains and that either aspirated KPPR1 bacteria have an enhanced ability to transit from the nose to the lungs in the context of a mixed-strain intranasal infection or they very rapidly begin to outcompete other K. pneumoniae strains once in the lungs.

FIG 7.

KPPR1 emerges as the dominant strain following intranasal or endotracheal inoculation. (A) A total of 1 × 104 CFU of each K. pneumoniae strain was individually inoculated into different groups of mice by the intranasal route. Bacterial burdens in the lungs were enumerated 30 min after infection and plotted as the final burden relative to the initial inoculum. Each symbol represents data for a mouse (n = 5 mice per infection group). Statistical significance was determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons (ns, not statistically significant). (B and C) Mice were inoculated intranasally (B) or endotracheally (C) with the pool of 10 K. pneumoniae strains, and StrainSeq analysis was performed at either 30 min postinfection (mpi) or 20 h postinfection (hpi). Results are based on data from two experiments, each using 6 to 10 mice per time point. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test (****, P < 0.0001).

We next examined whether KPPR1 outcompetes other K. pneumoniae strains after reaching the lungs. To ensure that approximately equivalent CFU of each strain were deposited in the lungs, mice were endotracheally intubated, and the pool of K. pneumoniae strains was inoculated directly into the lungs. StrainSeq was then performed at 30 min and 20 h postinfection. At 30 min postinfection, approximately equal numbers of KPPR1 (StrainSeq index of 0.96) and the other nine strains (StrainSeq indices from 0.65 to 1.10) were present in the lungs (Fig. 7C). However, by 20 h postinfection, KPPR1 showed clear dominance, exhibiting a StrainSeq index of 10.3. The isolate with the next highest index, hvKP4, exhibited a StrainSeq index of only 1.6. These results indicate that while a deposition advantage may influence strain dominance during mixed-strain infections, KPPR1 also outcompetes other K. pneumoniae strains following deposition in the lungs.

Multiple strains are capable of causing strain dominance.

We next examined what occurs when a dominant strain is removed from an inoculum of multiple strains. Mice were infected with the same combination of K. pneumoniae strains except that the dominant KPPR1 strain was excluded from the inoculum. In the absence of KPPR1, both hvKP1 and hvKP4 exhibited dominant phenotypes in the lungs at 20 h postinfection, with average StrainSeq indices of 5.23 and 12.34, respectively (Fig. 8A). In the presence of KPPR1, these same two strains had StrainSeq indices of 0.60 and 0.55, respectively (Fig. 3). We performed similar experiments with A. baumannii. When mice were infected with combinations of A. baumannii strains excluding the dominant strain ABBL105, a second strain, ABBL004, achieved an average StrainSeq index of 2.71 (Fig. 8B). In the presence of ABBL105, this strain had a StrainSeq index of 0.27 (Fig. 5). These results suggest that a hierarchy in strain dominance exists and that a new dominant strain emerges when a formerly dominant strain is removed from the inoculum.

FIG 8.

Removal or delayed inoculation of a dominant strain allows a new dominant strain to emerge. (A and B) StrainSeq analysis was performed 20 h after infection with K. pneumoniae (A) or A. baumannii (B) on mice intranasally infected with mixed-strain inocula lacking a dominant isolate. (C and D) In a second set of experiments, mice were intranasally infected with mixed-strain inocula of K. pneumoniae (C) or A. baumannii (D) that lacked the previously dominant strain and then reinoculated with the dominant strain (§) at 1 h postinfection. StrainSeq analysis was performed 20 h after the initial infection (for all experiments, n = 10 mice per group). All experiments were performed twice. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001).

Dominant strains no longer achieve outgrowth when their inoculation is delayed.

We next examined whether a dominant strain could still achieve numerical superiority when inoculated later than other strains. Mice were initially intranasally infected with a K. pneumoniae mixed-strain inoculum lacking KPPR1. One hour later, the same mice were given a second inoculum consisting of only KPPR1, and StrainSeq was then performed 20 h after the initial infection. Under these conditions, KPPR1 no longer exhibited a dominant phenotype (average StrainSeq index of 0.65), and instead, two other strains, hvKP1 and hvKP4, achieved average StrainSeq indices of 6.6 and 5.2, respectively (Fig. 8C). A similar experiment was performed to examine whether A. baumannii strain dominance was affected in the same way. When the dominant A. baumannii isolate, ABBL105, was excluded from the initial inoculum but introduced at 1 h postinfection, it too could no longer achieve a dominant phenotype at 20 h postinfection (StrainSeq index of 0.60), and instead, strain ABBL004 exhibited a StrainSeq index of 1.8 (Fig. 8D). These findings demonstrate that the relative timing of inoculation is an important variable in dictating whether a strain achieves dominance.

DISCUSSION

The lung is no longer viewed as a sterile site but rather as an organ that harbors a rich microbial community. This realization has led to the emerging concept that pathogens may themselves be part of this microbiome and that pneumonia occurs when a pathogen outcompetes other components of the microbiota to cause a dysbiosis in the lungs (2, 5, 8, 9). While a substantial amount of work has been done to examine species-to-species competition in this context, much less is known regarding how lineages of a single bacterial species compete with each other. We show that the K. pneumoniae strain KPPR1 outcompeted nine other K. pneumoniae strains following inoculation into the lungs of mice to achieve dominance. This strain dominance was specific to the host environment, as it did not occur in vitro. Additionally, strain dominance was not unique to K. pneumoniae but also occurred with another clinically relevant pulmonary pathogen, A. baumannii. Because the same strains reproducibly achieved dominance over repeat experiments, this phenomenon is not the result of a bottleneck or stochastic process but rather is intrinsic to the properties of the bacterial strains. Interestingly, strain dominance could not be predicted based upon an isolate’s in vitro growth characteristics or its virulence potential in single-strain infections, suggesting that it was instead the result of interactions between the dominant strain, the competing strains, and the host milieu. These findings suggest that intraspecies competition could be another factor in determining why some lineages of bacteria are more successful than others in causing pneumonia.

Several mechanisms may account for the ability of KPPR1 to outcompete other K. pneumoniae strains during early pneumonia. Bacteria have evolved both indirect and direct mechanisms to subvert competing bacteria while promoting their own successful outgrowth. Indirect bacterial competition occurs when a particular bacterial lineage alters the environment to make it unfavorable for the outgrowth of competitors. Examples of this are the sequestration of a shared resource such as iron, buildup of waste products, production of specialized metabolites, or induction of an immune response that is effective against some bacteria but not others (18, 19, 39–42). Direct bacterial competition, on the other hand, inhibits the outgrowth of specific bacterial lineages through antagonistic interactions. Examples of direct competition include the use of contact-dependent inhibition systems, type VI secretion systems, bacteriocins, and antibacterial metabolites (18, 43–46). We found that KPPR1 manifested its ability to outcompete other K. pneumoniae strains in the lungs but not in rich medium, which suggests an indirect mechanism. However, it remains possible that KPPR1 utilized a direct mechanism that was induced in the pulmonary environment but not in rich medium.

Phenomena similar to strain dominance have been described in other bacterial pathogens. Specifically, strains of S. pneumoniae with distinct capsular serotypes exhibited a hierarchy of upper airway colonization fitness following mixed-strain inoculations in a mouse model (47). Interestingly, strains with serotypes that were highly prevalent in human populations demonstrated an enhanced ability to outcompete less prevalent strains in colonization of a mouse model. The authors of that study suggested that the metabolic cost of capsule biosynthesis influenced strain dominance during mixed infections. In a second study, highly invasive Listeria monocytogenes strains outgrew moderately invasive strains in vitro in a contact-dependent manner (48). In addition, the presence of moderately invasive strains actually increased the internalization of the highly invasive strains during coincubation with human epithelial Caco2 cells. Likewise, strains of Borrelia burgdorferi differed in their abilities to compete for transmission from Ixodes scapularis ticks to mice (49, 50), and infection outcomes in Danio rerio (zebra fish) were influenced by the composition of mixed-strain Flavobacterium columnare inocula (50). Therefore, aspects of strain dominance may be widespread among bacterial pathogens.

Following inoculation of the upper airway with a mixture of bacterial strains, more efficient transit to the lungs could account for a strain’s dominance in pneumonia. The mixed-strain inocula initially used here were delivered intranasally; as such, a strain might achieve dominance by more efficiently migrating to the lungs than the competing strains. Indeed, StrainSeq analysis at 30 min postinfection showed that KPPR1 was already present in higher numbers in the lungs than the other nine strains, suggesting that it was more efficient in this process. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that KPPR1 had reached the lungs in numbers similar to those of the other nine strains but had already achieved a small degree of dominance over the subsequent 30 min. To more definitely examine KPPR1 strain dominance under conditions that ensured that each strain was deposited in equal numbers into the lungs, mixed-strain inocula were delivered directly to the lungs through endotracheal inoculation. Interestingly, in these experiments, KPPR1 no longer had a relative increase in numbers at 30 min postinoculation, yet strain dominance still occurred at 20 h postinfection. This suggests that KPPR1 may indeed be more efficient in migrating from the nares to the lungs but that if this advantage is removed, KPPR1 is still capable of achieving dominance at later time points.

Strain dominance in the lung was dependent upon both the composition of a mixed inoculum and the timing of inoculation. When KPPR1 was excluded from the initial inoculum but introduced into the lungs at 1 h postinfection, it could no longer effectively compete against the other strains in the lungs. Instead, populations of hvKP1 and hvKP4 emerged to become dominant. In ecology, the ability of a preexisting population to influence the establishment of an incoming population is referred to as a “priority effect” (51–55). Our results indicate that K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii exhibit a priority effect in the lungs. Such priority effects can influence the prevalence of specific microbes at the overall population level (56) and may partially explain why some strains of K. pneumoniae or A. baumannii are much more commonly encountered in patient settings than others. Interestingly, a priority effect was observed with a delay of only 1 h, suggesting that dominant strains rapidly established themselves in the lungs. Additionally, there was an apparent hierarchy in strain dominance when KPPR1 or ABBL105 was completely excluded from mixed-strain infections. Strain hierarchy during mixed infections has also been described for S. pneumoniae (47), and it is likely that additional pathogens exhibit similar hierarchies to facilitate strain dominance during infection. Exploring the microbial interactions that influence the kinetics of strain dominance during disease could provide insights into mechanisms responsible for this phenomenon.

Our findings indicate that the StrainSeq technique is a useful method for determining the relative abundance of bacterial strains in an animal model of pneumonia. One advantage of this approach is that barcoding is not required, making it ideal for studying genetically intractable bacteria or large numbers of strains. However, StrainSeq also has limitations. It requires that the compared strains differ by a substantial amount of genetic material, and it is more expensive than culture-based approaches. In our hands, it also required pooling of samples. We were unable to obtain sufficient amounts of DNA from a single mouse but were able to circumvent this difficulty by pooling DNA samples from six or more mice. We anticipate that further optimization will increase the sensitivity of StrainSeq.

In summary, our data demonstrate that strain dominance occurs by specific strains of K. pneumoniae to cause pneumonia, that the strain dominance phenotype is not stochastic, and that there is a strain hierarchy in establishing dominance during mixed infections. Additionally, strain dominance occurs in a similar manner by another pulmonary pathogen, A. baumannii. Finally, these data show that StrainSeq is an effective approach to examine population dynamics during mixed bacterial infections, and it could be utilized to identify dominant strain phenotypes of other bacterial pathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The sources of the bacterial isolates used in this study are listed in Table 1. K. pneumoniae strains hvKP1 and hvKP4 were generous gifts from Andrew Gulick of the Hauptman-Woodward Medical Research Institute and Thomas Russo from the Veterans Administration Western New York Healthcare System. KPPR1 was a generous gift from Wyndham Lathem of Northwestern University and Virginia Miller of the University of North Carolina.

Bacterial growth conditions.

K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, and Escherichia coli were routinely grown aerobically at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (10 g/liter tryptone, 5 g/liter yeast extract, 10 g/liter sodium chloride) or on LB agar plates (LB broth supplemented with 15 g/liter agar). K. pneumoniae KPPR1 was also grown aerobically at 30°C in low-salt LB broth (10 g/liter tryptone, 5 g/liter yeast extract, and 5 g/liter sodium chloride, adjusted to pH 8.0 with sodium hydroxide) or on low-salt LB agar plates (low-salt LB broth supplemented with 15 g/liter agar) for apramycin (Apra)-tagged strain construction. When appropriate, agar plates and media were supplemented with 50 μg/ml Apra or 100 μg/ml hygromycin B (Hyg). For growth curve experiments, bacteria were grown aerobically in LB medium overnight at 37°C, diluted 1:100 into fresh medium, and grown for an additional 2 h. After subculture, each strain was then adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.01 in fresh medium, which was used as the inoculum for in vitro growth experiments. During each hour of growth beginning at time zero, the OD was recorded for each strain on a microplate reader, and aliquots were serially diluted and plated on LB agar to correlate OD600 readings to CFU at each hour of growth. For pooling of strains for in vitro and in vivo experiments, bacteria were aerobically grown separately in LB broth at 37°C overnight. Cultures were then diluted 1:100 into 800 μl of fresh medium in deep-well 96-well plates and grown separately for an additional 2 h. Each strain was then adjusted to its target OD600 value in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before pooling so that each pooled inoculum contained the same CFU of each bacterial strain.

Mice.

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and housed in the containment ward of the Center for Comparative Medicine at Northwestern University. Mouse age at the beginning of each experiment was 8 to 10 weeks. Pilot experiments showed no significant sex-specific differences, and thus, all experiments were performed with female mice. Mice were euthanized for humane reasons when severe illness developed or when animals reached a predetermined endpoint of an experiment. All experiments involving mice were approved by and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Northwestern University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Murine model of acute pneumonia.

For intranasal infections, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 50 μl of a mixture of 25% ketamine and 5% 5× xylazine in PBS. A total of 50 μl of suspended bacteria was placed on the nares of mice for aspiration into the lungs, and mice were placed on their backs to recover from inoculation. For endotracheal infections, mice were similarly anesthetized and laid on their backs on a 45° inclined plane. The mouth was opened, and the teeth and tongue were separated to visualize the vocal cords. A BD Angiocath Autoguard intravenous (i.v.) catheter (20 gauge, 1 in.; Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) was placed in position using an Arrow wire guide (Arrow International, Inc., Asheboro, NC) and passed between the vocal cords until reaching the lower part of the trachea. Two 25-μl doses of suspended bacteria were delivered through the catheter to the lungs using a flexible Hamilton model 702N SYR injector (Hamilton Robotics, Franklin, MA), and mice were rotated to allow for uniform inoculum deposition. For all experiments, mice recovered on a low-heat pad and were closely monitored following infection until normal breathing was again observed.

Single-strain virulence measurements.

K. pneumoniae strains were grown aerobically in LB broth overnight at 37°C, diluted 1:100 into fresh medium, and grown for an additional 2 h. To calculate modified 50% lethal dose (mLD50) values, groups of mice were intranasally infected with increasing doses of bacteria, and illness severity was monitored over the course of 14 days. Mice were clinically scored based on their respiration, appearance, and activity. Animals meeting predetermined criteria for severe illness were euthanized and scored as dead. The Reed-Muench calculation (57) was used to estimate the dose that would result in approximately 50% survival following 14 days of infection. The number of mice in each infection group, doses, the percentage of mice reaching prelethal illness, and mLD50 values are included in Table S1 in the supplemental material. In other experiments, mice were intranasally infected with doses of bacteria near the mLD50 values to ensure similar degrees of illness in all mice. Mice were euthanized at 20 h postinfection, and their lungs were surgically removed, homogenized in 5 ml PBS, serially diluted in PBS, and plated on LB agar to enumerate CFU. For A. baumannii survival experiments, mice were intranasally inoculated with 4 × 106 CFU/mouse and monitored for severe illness over the subsequent 7 days. A. baumannii bacterial burden experiments were performed as described above for K. pneumoniae except that a constant dose of 1 × 106 CFU/mouse was used for each strain.

StrainSeq infections and DNA extractions.

Bacteria were aerobically grown separately in LB broth at 37°C overnight. Cultures were then diluted 1:100 into 800 μl of fresh medium in deep-well 96-well plates and grown separately for an additional 2 h. For K. pneumoniae, each strain was then adjusted to an OD600 value corresponding to 2 × 106 CFU/ml in PBS, and 0.1 ml of each bacterial preparation was pooled such that each pooled inoculum (1 × 105 CFU total) contained 1 × 104 CFU of each bacterial strain per 50-μl inoculum. For A. baumannii, each strain was adjusted to an OD600 value corresponding to 1.3 × 107 CFU/ml in PBS, and 0.1 ml of each bacterial preparation was pooled so that each pooled inoculum (4 × 106 CFU total) contained 6.7 × 105 CFU of each bacterial strain per 50-μl inoculum, which was used to infect mice (50 μl/mouse). Another 1-ml aliquot of a pooled inoculum was made in the same manner, and approximately 400 μl of this pooled inoculum was set aside for analysis of the “input pool.” In certain experiments, a bacterial strain omitted from the pool was individually inoculated into the mice at 1 h postinfection. At 20 h postinfection, mice were euthanized, and their lungs were surgically removed. In certain experiments, each pair of lungs was homogenized in 5 ml PBS, and an aliquot was serially diluted to determine bacterial outgrowth in the lungs. The remaining homogenate was centrifuged at 11,000 × g for 15 min. The pellet was resuspended in 1.5 ml 1% Triton X-100 in PBS and incubated at room temperature for 5 min to lyse eukaryotic cells. After incubation, the suspension underwent centrifugation at 11,000 × g for 15 min. The pellet was washed twice in 1 ml PBS, followed by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 5 min. The pellet was then resuspended in 400 μl PBS to yield an output sample for each mouse. The input pool and individual output samples were then processed with a Maxwell 16 cell DNA purification kit and instrument (Promega, Madison, WI) for DNA extraction. All output samples from mice infected with the same bacterial inoculum were combined to obtain a single DNA “output pool.”

For in vitro StrainSeq experiments, bacteria were grown and pooled as described above. Pooled cultures were grown in 5 ml LB broth at 37°C with shaking for 6 to 12 h. After growth, an aliquot of the culture was serially diluted and plated onto LB agar to determine bacterial CFU. Input and output pool samples were pelleted and resuspended in 400 μl PBS for DNA extraction using the Maxwell 16 cell DNA purification kit and instrument.

Quality assessment and prokaryotic enrichment of DNA samples.

Input and output pool DNA extractions were quantified fluorometrically at 502-nm excitation and 523-nm emission wavelengths in duplicate on a microplate reader using the Quant-iT double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). DNA quality was also assessed using 260-nm/280-nm and 260-nm/230-nm absorption ratios as measured by using a NanoDrop instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). One microgram of DNA from each in vivo output pool sample was enriched for prokaryotic DNA using the NEBNext microbiome DNA enrichment kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and eluted together into 50 μl elution buffer. Enriched output DNA was quantified in duplicate using the Quant-iT dsDNA assay kit on a microplate reader, and DNA quality was assessed using NanoDrop readings. Input and output DNA samples were stored at −20°C.

StrainSeq library preparation and sequencing.

Sequencing libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT DNA library preparation kit and protocol (Illumina, San Diego, CA). DNA samples were tagmented for 5 min at 55°C and subsequently neutralized for 5 min at room temperature. The indexing primers for each sample were purchased from Illumina. Input DNA samples for each experiment were amplified with the primer set N701 and S502, while output DNA samples were amplified with the primer set N702 and S502. PCR amplifications were purified using the Agencourt AMPure XP bead system (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) and eluted into a final volume of 50 μl in resuspension buffer. Clean DNA libraries were quantified in duplicate using the Quant-iT dsDNA assay kit on a microplate reader, and DNA quality was assessed using NanoDrop readings. Libraries were also visualized on a 1% agarose gel to assess DNA integrity. Aliquots of 5 μl were analyzed by Northwestern University’s NUSeq Core using a DNA LabChip (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) for fragment size. Input and output libraries were stored at −20°C.

DNA molarity for each library was determined by an online calculator using Quant-iT concentrations and average fragment sizes from LabChip analysis. Input-to-output 1:4 molar ratios were pooled to a final concentration of 4 nM. Pooled libraries were denatured with 0.2 N sodium hydroxide for 5 min at room temperature. In vitro StrainSeq libraries were diluted to 12 pM, while in vivo StrainSeq libraries were diluted to 17 pM. A 1% spike-in of 20 pM PhiX control was added to pooled libraries before sequencing on the MiSeq platform with 2-by-300 paired-end reads to generate FastQ sequence read data.

StrainSeq data analysis.

Genome sequences were de novo assembled from Illumina MiSeq reads using SPAdes (58). The core genome sequence of the isolates in mixed infections, defined as genomic sequences with at least 85% similarity and present in all of the isolates, was identified using Spine (59). Any sequences not in the core genome were classified as an accessory genome by the AGEnt software program (59). The ClustAGE software program (60) was used to compare accessory genome sequences between isolates and identify endogenous barcodes, i.e., accessory sequences unique to each strain. The genomic coordinates of AGE barcodes used for K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii are included in Tables S2 and S3, respectively.

The unique accessory sequences were used to determine the relative proportions of the strains in the input and output samples. Following sequencing of the input or output samples, total reads were filtered to remove adapter sequence contamination and low-quality reads using Trimmomatic v0.36 (61) and aligned to the unique accessory sequences of each strain using bwa v0.7.9a (62). Reads with insertions, deletions, partial alignments, or >2 mismatched bases were removed to avoid false alignments. To normalize for the different amounts of unique accessory sequences present in each strain, the total number of reads aligned to unique accessory sequences in a strain was divided by the kilobases of unique accessory sequences in that strain. To account for differences in depth of sequencing between experiments, this value itself was divided by the total number of reads, in thousands, aligning to all unique accessory sequences across all the strains included in the experiment. Thus, the proportion of strain “i” bacteria in a sample of bacteria consisting of strains i, j, and k, etc., is calculated using the following equation: [(reads aligning to unique accessory sequences)i/(kilobases of unique accessory sequences)i]/sum(reads aligned to unique accessory sequences/1,000)i,j,k,… = relative proportion of strain i.

The change in the proportion of strain i in the population over the course of an infection (or following growth in medium) was quantified as the StrainSeq index of strain i, which is defined as the ratio of the relative proportion of strain i after infection (as measured in the output sample) divided by the relative proportion of strain i in the inoculum (as measured in the input sample): (relative proportion of strain i in output sample)/(relative proportion of strain i in input sample) = (StrainSeq index)i.

Construction of apramycin-tagged KPPR1.

To generate a KPPR1 strain carrying a chromosomal copy of the apramycin resistance cassette (KPPR1::Aprar), the lambda red approach described previously by Huang and colleagues (63) was utilized to introduce the apramycin resistance gene [aac(3)IV] adjacent to the neutral attTn7 site. Approximately 500 bp of sequences upstream and downstream of the insertion site were cloned using KPPR1 genomic DNA and the primer sets (i) F-Tn7-up and R-Tn7-up and (ii) F-Tn7-down and R-Tn7-down, respectively. The apramycin resistance gene [aac(3)IV] and flanking FLP recombination target (FRT) sites were PCR amplified using the plasmid template pIJ773 (63) and the primers ApR-F and ApR-R2. The PCR products were purified, pooled, and then joined by overlapping extension PCR using primers F-Tn7-up and R-Tn7-down. The resulting PCR product was transformed into KPPR1 carrying the lambda red plasmid pACBSR-Hyg. Chromosomal integration of the apramycin cassette was confirmed by antibiotic selection on apramycin-containing medium and by colony PCR. Primers used for aac(3)IV integration are listed in Table 2, and plasmids used were pIJ773 [ori(T) FRT Aprar], pACBSR-Hyg [pACBSR ori(p15A) araC Hygr], and pFLP-Hyg [pFLP ori(p15A) flp Hygr] (63).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used to construct KPPR1::Aprar

aAll primers were constructed in this work.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical tests utilized were discussed and confirmed with the Biostatistics Collaboration Center (BCC) at Northwestern University. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 7.0b). Replicate StrainSeq data are either visually shown for each individual experiment or represented as means ± standard deviations. StrainSeq statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, unless otherwise stated. Bacterial burdens are represented as means ± standard errors. These data did not follow a normal distribution, so statistical analyses were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons. Differences for all tests are noted in the figure legends.

Data availability.

Nucleotide sequence data for strains newly determined in this study were deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers: QAUY00000000, QBBZ00000000, QBCA00000000, QBCB00000000, QBCC00000000, QBCD00000000, QBCE00000000, and QBCF00000000. The versions reported here are the first versions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the NUSeq Core at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine for assistance with performance of Illumina whole-genome sequencing. We acknowledge the Biostatistics Collaboration Center and Northwestern University for assistance with StrainSeq statistical analysis. We also thank Thomas Russo and Andrew Gulick for providing strains hvKP1 and hvKP4 and Wyndham Lathem and Virginia Miller for providing strain KPPR1.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers K24 AI104831, R01 AI053674, R01 AI118257, and U19 AI135964 to A.R.H. and T32 AI747620 to M.J.A.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00871-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dickson RP, Erb-Downward JR, Martinez FJ, Huffnagle GB. 2016. The microbiome and the respiratory tract. Annu Rev Physiol 78:481–504. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huffnagle GB, Dickson RP, Lukacs NW. 2017. The respiratory tract microbiome and lung inflammation: a two-way street. Mucosal Immunol 10:299–306. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venkataraman A, Bassis CM, Beck JM, Young VB, Curtis JL, Huffnagle GB, Schmidt TM. 2015. Application of a neutral community model to assess structuring of the human lung microbiome. mBio 6:e02284-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02284-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gleeson K, Eggli DF, Maxwell SL. 1997. Quantitative aspiration during sleep in normal subjects. Chest 111:1266–1272. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.5.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickson RP, Erb-Downward JR, Huffnagle GB. 2014. Towards an ecology of the lung: new conceptual models of pulmonary microbiology and pneumonia pathogenesis. Lancet Respir Med 2:238–246. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70028-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huxley EJ, Viroslav J, Gray WR, Pierce AK. 1978. Pharyngeal aspiration in normal adults and patients with depressed consciousness. Am J Med 64:564–568. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90574-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickson RP, Huffnagle GB. 2015. The lung microbiome: new principles for respiratory bacteriology in health and disease. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004923. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickson RP, Martinez FJ, Huffnagle GB. 2014. The role of the microbiome in exacerbations of chronic lung diseases. Lancet 384:691–702. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61136-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickson RP, Erb-Downward JR, Huffnagle GB. 2015. Homeostasis and its disruption in the lung microbiome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 309:L1047–L1055. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00279.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly BJ, Imai I, Bittinger K, Laughlin A, Fuchs BD, Bushman FD, Collman RG. 2016. Composition and dynamics of the respiratory tract microbiome in intubated patients. Microbiome 4:7. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0151-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diaz E, Rodríguez AH, Rello J. 2005. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: issues related to the artificial airway. Respir Care 50:900–906; discussion 906–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niederman MS. 1990. Gram-negative colonization of the respiratory tract: pathogenesis and clinical consequences. Semin Respir Infect 5:173–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bassis CM, Erb-Downward JR, Dickson RP, Freeman CM, Schmidt TM, Young VB, Beck JM, Curtis JL, Huffnagle GB. 2015. Analysis of the upper respiratory tract microbiotas as the source of the lung and gastric microbiotas in healthy individuals. mBio 6:e00037-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00037-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bahrani-Mougeot FK, Paster BJ, Coleman S, Barbuto S, Brennan MT, Noll J, Kennedy T, Fox PC, Lockhart PB. 2007. Molecular analysis of oral and respiratory bacterial species associated with ventilator-associated pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol 45:1588–1593. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01963-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bousbia S, Papazian L, Saux P, Forel JM, Auffray JP, Martin C, Raoult D, La Scola B. 2012. Repertoire of intensive care unit pneumonia microbiota. PLoS One 7:e32486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mourani PM, Sontag MK. 2017. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill children: a new paradigm. Pediatr Clin North Am 64:1039–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu W, Yu J, Ai Q, Liu D, Song C, Li L. 2014. Increased constituent ratios of Klebsiella sp., Acinetobacter sp., and Streptococcus sp. and a decrease in microflora diversity may be indicators of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a prospective study in the respiratory tracts of neonates. PLoS One 9:e87504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hibbing ME, Fuqua C, Parsek MR, Peterson SB. 2010. Bacterial competition: surviving and thriving in the microbial jungle. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:15–25. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stubbendieck RM, Straight PD. 2016. Multifaceted interfaces of bacterial competition. J Bacteriol 198:2145–2155. doi: 10.1128/JB.00275-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiner LM, Webb AK, Limbago B, Dudeck MA, Patel J, Kallen AJ, Edwards JR, Sievert DM. 2016. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011-2014. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 37:1288–1301. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.CDC. 2013. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States. CDC, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 22.WHO. 2017. Global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tumbarello M, Trecarichi EM, De Rosa FG, Giannella M, Giacobbe DR, Bassetti M, Losito AR, Bartoletti M, Del Bono V, Corcione S, Maiuro G, Tedeschi S, Celani L, Cardellino CS, Spanu T, Marchese A, Ambretti S, Cauda R, Viscoli C, Viale P, Italian Study Group on Resistant Infections of the Società Italiana Terepia Antinfettiva. 2015. Infections caused by KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: differences in therapy and mortality in a multicentre study. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:2133–2143. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO. 2014. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112642/1/9789241564748_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 11 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holt KE, Wertheim H, Zadoks RN, Baker S, Whitehouse CA, Dance D, Jenney A, Connor TR, Hsu LY, Severin J, Brisse S, Cao H, Wilksch J, Gorrie C, Schultz MB, Edwards DJ, Nguyen KV, Nguyen TV, Dao TT, Mensink M, Minh VL, Nhu NTK, Schultsz C, Kuntaman K, Newton PN, Moore CE, Strugnell RA, Thomson NR. 2015. Genomic analysis of diversity, population structure, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae, an urgent threat to public health. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E3574–E3581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501049112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito R, Shindo Y, Kobayashi D, Ando M, Jin W, Wachino J, Yamada K, Kimura K, Yagi T, Hasegawa Y, Arakawa Y. 2015. Molecular epidemiological characteristics of Klebsiella pneumoniae associated with bacteremia among patients with pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol 53:879–886. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03067-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abodakpi H, Chang KT, Sánchez Díaz AM, Cantón R, Lasco TM, Chan K, Sofjan AK, Tam VH. 2018. Prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase and carbapenemase-producing bloodstream isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae in a tertiary care hospital. J Chemother 30:115–119. doi: 10.1080/1120009X.2017.1399233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulvey MR, Haraoui LP, Longtin Y. 2016. Multiple variants of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing carbapenemase in one patient. N Engl J Med 375:2408–2410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1511360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liao CH, Huang YT, Chang CY, Hsu HS, Hsueh PR. 2014. Capsular serotypes and multilocus sequence types of bacteremic Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates associated with different types of infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 33:365–369. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1964-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brisse S, Fevre C, Passet V, Issenhuth-Jeanjean S, Tournebize R, Diancourt L, Grimont P. 2009. Virulent clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae: identification and evolutionary scenario based on genomic and phenotypic characterization. PLoS One 4:e4982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen L, Mathema B, Chavda KD, DeLeo FR, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2014. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: molecular and genetic decoding. Trends Microbiol 22:686–696. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dhar S, Martin ET, Lephart PR, McRoberts JP, Chopra T, Burger TT, Tal-Jasper R, Hayakawa K, Ofer-Friedman H, Lazarovitch T, Zaidenstein R, Perez F, Bonomo RA, Kaye KS, Marchaim D. 2016. Risk factors and outcomes for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolation, stratified by its multilocus sequence typing: ST258 versus non-ST258. Open Forum Infect Dis 3:ofv213. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paczosa MK, Mecsas J. 2016. Klebsiella pneumoniae: going on the offense with a strong defense. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 80:629–661. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00078-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freeman JT, Nimmo J, Gregory E, Tiong A, De Almeida M, McAuliffe GN, Roberts SA. 2014. Predictors of hospital surface contamination with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: patient and organism factors. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 3:5. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snitkin ES, Won S, Pirani A, Lapp Z, Weinstein RA, Lolans K, Hayden MK. 2017. Integrated genomic and interfacility patient-transfer data reveal the transmission pathways of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a regional outbreak. Sci Transl Med 9:eaan0093. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aan0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conlan S, Kong HH, Segre JA. 2012. Species-level analysis of DNA sequence data from the NIH Human Microbiome Project. PLoS One 7:e47075. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorrie CL, Mirceta M, Wick RR, Edwards DJ, Thomson NR, Strugnell RA, Pratt NF, Garlick JS, Watson KM, Pilcher DV, McGloughlin SA, Spelman DW, Jenney AWJ, Holt KE. 2017. Gastrointestinal carriage is a major reservoir of Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in intensive care patients. Clin Infect Dis 65:208–215. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mehtälä J, Antonio M, Kaltoft MS, O’Brien KL, Auranen K. 2013. Competition between Streptococcus pneumoniae strains: implications for vaccine-induced replacement in colonization and disease. Epidemiology 24:522–529. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318294be89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park T. 1954. Experimental studies of interspecies competition. II. Temperature, humidity, and competition in two species of Tribolium. Physiol Zool 27:177–238. doi: 10.1086/physzool.27.3.30152164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harrison F, Paul J, Massey RC, Buckling A. 2008. Interspecific competition and siderophore-mediated cooperation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ISME J 2:49–55. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramsey MM, Whiteley M. 2009. Polymicrobial interactions stimulate resistance to host innate immunity through metabolite perception. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:1578–1583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809533106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stacy A, Abraham N, Jorth P, Whiteley M. 2016. Microbial community composition impacts pathogen iron availability during polymicrobial infection. PLoS Pathog 12:e1006084. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aoki SK, Poole SJ, Hayes CS, Low DA. 2011. Toxin on a stick: modular CDI toxin delivery systems play roles in bacterial competition. Virulence 2:356–359. doi: 10.4161/viru.2.4.16463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Sturtevant D, Krastins B, Sarracino D, Nelson WC, Heidelberg JF, Mekalanos JJ. 2006. Identification of a conserved bacterial protein secretion system in Vibrio cholerae using the Dictyostelium host model system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:1528–1533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510322103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Basler M, Mekalanos JJ. 2012. Type 6 secretion dynamics within and between bacterial cells. Science 337:815. doi: 10.1126/science.1222901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Machan ZA, Taylor GW, Pitt TL, Cole PJ, Wilson R. 1992. 2-Heptyl-4-hydroxyquinoline N-oxide, an antistaphylococcal agent produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother 30:615–623. doi: 10.1093/jac/30.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trzciński K, Li Y, Weinberger DM, Thompson CM, Cordy D, Bessolo A, Malley R, Lipsitch M. 2015. Effect of serotype on pneumococcal competition in a mouse colonization model. mBio 6:e00902-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00902-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zilelidou EA, Rychli K, Manthou E, Ciolacu L, Wagner M, Skandamis PN. 2015. Highly invasive Listeria monocytogenes strains have growth and invasion advantages in strain competition. PLoS One 10:e0141617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rynkiewicz EC, Brown J, Tufts DM, Huang CI, Kampen H, Bent SJ, Fish D, Diuk-Wasser M. 2017. Closely-related Borrelia burgdorferi (sensu stricto) strains exhibit similar fitness in single infections and asymmetric competition in multiple infections. Parasit Vectors 10:64. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1964-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kinnula H, Mappes J, Sundberg LR. 2017. Coinfection outcome in an opportunistic pathogen depends on the inter-strain interactions. BMC Evol Biol 17:77. doi: 10.1186/s12862-017-0922-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Egler F. 1954. Vegetation science concepts. I. Initial floristic composition, a factor in old-field vegetation development. Veg Acta Geobot 4:412–417. doi: 10.1007/BF00275587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Belyea L, Lancaster J. 1999. Assembly rules within a contingent ecology. Oikos 86:402–416. doi: 10.2307/3546646. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Drake J. 1991. Community-assembly mechanics and the structure of an experimental species ensemble. Am Nat 137:1–26. doi: 10.1086/285143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gleason H. 1927. Further views on the succession concept. Ecology 8:299–326. doi: 10.2307/1929332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hodge S, Arthur W, Mitchell P. 1996. Effects of temporal priority on interspecific interactions and community development. Oikos 76:350–358. doi: 10.2307/3546207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clay PA, Cortez MH, Duffy MA, Rudolf VHW. 2019. Priority effects within coinfected hosts can drive unexpected population‐scale patterns of parasite prevalence. Oikos 128:571–583. doi: 10.1111/oik.05937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reed L, Muench H. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am J Epidemiol 27:493–497. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a118408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ozer EA, Allen JP, Hauser AR. 2014. Characterization of the core and accessory genomes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa using bioinformatic tools Spine and AGEnt. BMC Genomics 15:737. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ozer EA. 2018. ClustAGE: a tool for clustering and distribution analysis of bacterial accessory genomic elements. BMC Bioinformatics 19:150. doi: 10.1186/s12859-018-2154-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang TW, Lam I, Chang HY, Tsai SF, Palsson BO, Charusanti P. 2014. Capsule deletion via a λ-Red knockout system perturbs biofilm formation and fimbriae expression in Klebsiella pneumoniae MGH 78578. BMC Res Notes 7:13. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Broberg CA, Wu W, Cavalcoli JD, Miller VL, Bachman MA. 2014. Complete genome sequence of Klebsiella pneumoniae strain ATCC 43816 KPPR1, a rifampin-resistant mutant commonly used in animal, genetic, and molecular biology studies. Genome Announc 2:e00924-14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00924-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pomakova DK, Hsiao CB, Beanan JM, Olson R, MacDonald U, Keynan Y, Russo TA. 2012. Clinical and phenotypic differences between classic and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumonia: an emerging and under-recognized pathogenic variant. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 31:981–989. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1396-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Russo TA, Olson R, Macdonald U, Metzger D, Maltese LM, Drake EJ, Gulick AM. 2014. Aerobactin mediates virulence and accounts for increased siderophore production under iron-limiting conditions by hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Immun 82:2356–2367. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01667-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Piechaud D, Second L. 1951. Etude de 26 souches de Moraxella lwoffi. Ann Inst Pasteur (Paris) 80:97–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fitzpatrick MA, Ozer E, Bolon MK, Hauser AR. 2015. Influence of ACB complex genospecies on clinical outcomes in a U.S. hospital with high rates of multidrug resistance. J Infect 70:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Nucleotide sequence data for strains newly determined in this study were deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers: QAUY00000000, QBBZ00000000, QBCA00000000, QBCB00000000, QBCC00000000, QBCD00000000, QBCE00000000, and QBCF00000000. The versions reported here are the first versions.