Abstract

Background:

Diagnosis and treatment of incurable cancer as a life-changing experience evokes difficult existential questions.

Aim:

A structured reflection could improve patients’ quality of life and spiritual well-being. We developed an interview model on life events and ultimate life goals and performed a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effect thereof on quality of life and spiritual well-being.

Design:

The intervention group had two consultations with a spiritual counselor. The control group received care as usual. EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL and the FACIT-sp were administered at baseline and 2 and 4 months after baseline. Linear mixed model analysis was performed to test between-group differences over time.

Participants:

Adult patients with incurable cancer and a life expectancy ⩾6 months were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to the intervention or control group.

Results:

A total of 153 patients from six different hospitals were included: 77 in the intervention group and 76 in the control group. Quality of life and spiritual well-being did not significantly change over time between groups. The experience of Meaning/Peace was found to significantly influence quality of life (β = 0.52, adj. R2 = 0.26) and satisfaction with life (β = 0.61, adj. R2 = 0.37).

Conclusion:

Although our newly developed interview model was well perceived by patients, we were not able to demonstrate a significant difference in quality of life and spiritual well-being between groups. Future interventions by spiritual counselors aimed at improving quality of life, and spiritual well-being should focus on the provision of sources of meaning and peace.

Keywords: Oncology, palliative care, spirituality, spiritual care, spiritual care givers, randomized controlled trials

What is already known about the topic?

Spiritual well-being and quality of life are important to patients with advanced cancer.

What this paper adds?

We developed a new intervention to address life events and life goals in order to improve quality of life and spiritual well-being.

Implications for practice, theory, or policy

The intervention was well perceived by all patients. Our explorative study showed a significant influence of Meaning/Peace on quality of life. Future studies should focus on the provision of sources of meaning and peace.

Introduction

In times of a severe illness, sources of hope, meaning and peace are of extra importance to patients’ well-being.1 Patients with incurable cancer are known to re-evaluate what is important in life and gain a clearer perception on the meaning of life.2,3 The process of seeking and expressing meaning and purpose in life and the experience of connectedness to others, the self, nature, the moment, and a higher being are taken together in the concept of spirituality.4 The importance of spirituality in dealing with a terminal illness is increasingly recognized.5 The definition of palliative care by the World Health Organization includes spirituality, and accordingly, several national palliative care guidelines outline spiritual care as a domain of palliative care.6

Several studies have shown the importance of spiritual care in advanced cancer patients.7–10 Nevertheless, patients’ spirituality is still underappreciated in the palliative, oncological setting and cancer patients were found to have unmet spiritual needs.11 Several ways to provide spiritual care are available, ranging from spiritually focused psychotherapy12 to handling prayer requests.13 However, given the relevance of spiritual care to assist in finding meaning and purpose in life, interventions based on a narrative approach directed at meaning-making may be most promising.14–17 In the process of finding meaning and purpose in life, the concept of life goals is of utmost importance.18–20 Life goals entail people’s ultimate values and interests, and their innermost motivations.21,22

In order to fulfill the need for effective spiritual care, we developed an intervention in which patients’ spirituality is addressed in a structured manner, using a narrative approach directed at meaning-making in search for important life events and ultimate life goals. This model takes into account the experiences people may have when they are confronted with unexpected life events. The way people react to these unexpected events tells us something about their underlying (ultimate) life goals. Here, we investigated the effect of this newly developed spiritual counselor-assisted structured interview on quality of life (QoL) and spiritual well-being (SWB) of cancer patients.23 Importantly, although numerous studies have shown relationships between SWB and QoL, questions pertaining to the nature and direction of this relationship still remain unanswered.24 This randomized controlled trial (RCT) also gives us the opportunity to explore the relationship between SWB and QoL in our study population.

Methods

Study sample

A comprehensive protocol of this study was published previously.23 In brief, patients ⩾18 years of age with advanced cancer not amenable to curative treatment were eligible for participation if they had a life expectancy of ⩾6 months. Exclusion criteria were a Karnofsky Performance Score < 60, insufficient command of the Dutch language, and current psychiatric diseases. Eligible patients were invited by their own oncologist or oncology nurse and asked if the researcher could inform them about the study details. All patients gave written informed consent.

Study protocol

Patients from six different hospitals were recruited, including two academic hospitals and one categorical hospital. The Medical Ethics Review Committee of the Academic Medical Center Amsterdam confirmed that the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) did not apply to our study and therefore an official approval of this study by the committee was not required. After informed consent, a baseline assessment took place including an evaluation of QoL and SWB. Within 2 weeks after baseline assessment, patients were randomized to the intervention or the control group (care as usual). Patients assigned to the intervention group had two consultations at the hospital where they were treated with a spiritual counselor who received a specific training for the interview model. Each spiritual counselor received about the same number of referrals, between 10 and 12 patients. The consultations were audio recorded by the spiritual counselors and send to the research team (R.K. and M.S.-R.). They evaluated the consultations and provided feedback if necessary, ensuring ongoing quality of the intervention. Two and four months after randomization, patients of both groups completed questionnaires regarding QoL, SWB, satisfaction with life (SwL), anxiety, depression, and religion/spirituality.

Randomization

Randomization was performed online via a secure Internet facility in a 1:1 ratio by the TENALEA Clinical Trial Data Management System using randomly permuted blocks with maximum block size 4 within strata formed by seven spiritual counselors.

Intervention

We developed an interview model for an assisted, structured reflection on important life events and life goals, which was supported by an e-application on an iPad.23 The assisted reflection was carried out in two consultations of 1 hour each with a spiritual counselor, based on previous research in life goals and experiences of contingency.25,26 In the first consultation, patients discussed important life events and defined life goals. The spiritual counselor analyzed the consultation for possible tension or coherence between life events and life goals, as described previously21 and discussed the findings with the patient in the second consultation, using the iPad. After the second consultation, patients received a handout with a schematic representation of their life events and life goals. The spiritual counselors were all experienced in the practice of providing spiritual care in a hospital setting (mean years working in a hospital: 12.5). They were extensively trained in using the model as described elsewhere.27

Outcome measures

The main outcome was overall QoL and SWB. Overall QoL was assessed with EORTC QLQ C15-PAL, a shortened version of the EORTC QLQ C30, designed for use in the palliative care setting.28 The one-item scale ranges from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating better QoL. SWB was assessed by the FACIT-sp12 using the subscale Meaning/Peace, ranging from 0 to 32, in which a higher score indicates a better SWB.29 Other outcomes were the subscale Faith from the FACIT-sp12 ranging from 0 to 16, SwL measured by The Satisfaction with Life Scale ranging from 5 to 35 with a score >20 indicating satisfaction.30 Anxiety and Depression were assessed by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, ranging from 0 to 21. A score of ⩾11 indicates a clinical level of anxiety and/or depression.31 After the two consultations, patients’ satisfaction with the intervention was assessed by an evaluation form where the patients could rate their experiences with the spiritual counselor, the consultations themselves, the iPad and the hand-out on a scale from 1 “not satisfied” to 5 “satisfied.” Additional space was provided to elaborate on their answers. At baseline, demographic data, including data on religious/spiritual background, as well as medical data, including tumor type, time since diagnosis, and treatments were collected.

Statistical analyses

The sample size was calculated using the software G*Power with the aim to detect a small clinical significant effect (effect size f = 0.10) on the main outcome overall QoL.32,33 The desired statistical power is 80%, with a two-side significance of 5%, standard deviation of 25.6, mean of 56.3, and the correlation between repeated assessments of r = 0.63.34,35 We expected a drop out of 20%, therefore a sample of 153 patients was needed.36 Descriptive statistics were used to describe participants’ demographics at baseline. Questionnaires were scored according to the respective manuals. Missing data patterns of baseline, post and follow-up were analyzed with the Little’s Missing Completely At Random (MCAR) test to verify if data were missing completely at random. Missing data were imputed if more than 50% of the item responses within a scale was present and only case by case if there was a credible reason to believe that the data could be imputed by the mean of the questionnaire. To examine if the data were normally distributed, we visually inspected histograms and normality Q-Q Plots. To detect differences between the control group and the intervention group in the primary outcome measures over baseline, post- and follow-up measurement, we conducted a linear mixed model analysis. We included only two fixed parameters: time and group, and the covariance structures were set to compound symmetry. Subgroup analyses were performed using the linear mixed model over time between two groups, for men/women, young (18–54 years)/old (⩾55 years), chemo/no-chemo, and reported religious/non-religious status.

To explore which factors were associated with the primary outcomes QoL and SWB in the entire patient population, we selected relevant factors based on the literature: age, gender, education, marital status, cancer type, treatment, anxiety, and depression.37–39 We also examined the association of SWB with QoL in the entire patient population at baseline, to explore unanswered questions pertaining to the nature and direction of this association. SWB was examined using the two subscales of the FACIT-sp: Meaning/Peace and Faith. Faith was explored as an intermediate variable for Meaning/Peace and Meaning/Peace as an independent as well as an intermediate variable for QoL.40–42 To explore the influence of the relevant factors on Meaning/Peace and the influence of Meaning/Peace on QoL, we conducted a multiple linear regression analysis using the enter method. Furthermore, we calculated the most ideal cut-off score of Meaning/Peace using a receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis to discriminate between high and low QoL. The cutoff score was determined at 22.9 for Meaning/Peace on a categorical QoL scale (<56.3 = 1 low QoL, >56.3 = 0 high QoL).38 The area under the curve (AUC) was determined at 0.85, with a sensitivity of 68.5% and specificity of 92.3%, indicating a “good” test.43 Thereafter, we conducted uni- and multivariable logistic regression analyses to determine the magnitude of effect of Meaning/Peace on QoL, adjusted for covariates. IBM SPSS Statistics version 23 was used for all analyses and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Study population

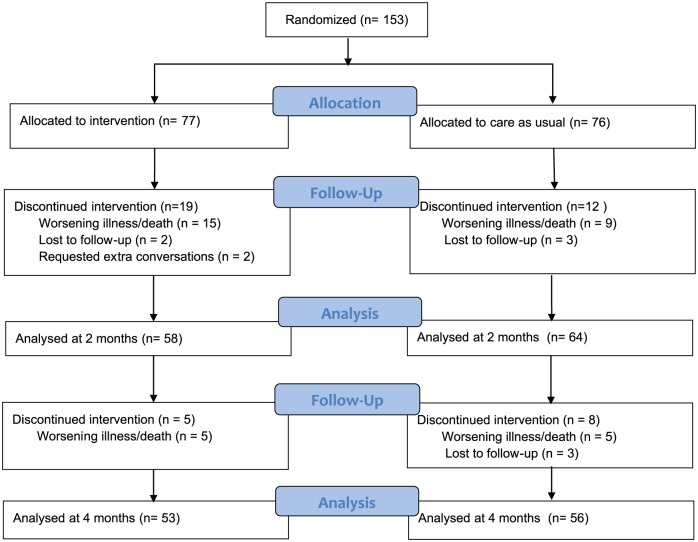

Between July 2014 and March 2016, 153 advanced cancer patients from six different hospitals across The Netherlands were included in the study. In total, 77 patients were randomized to the intervention group and 76 for the control group, respectively. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of the 153 included patients, 77 (50%) were female and the mean age was 62 years (SD = 10.5, range: 24–85), which can be considered representative of the Dutch population with cancer.44 Patient characteristics were well balanced between the control and the intervention group. Baseline measurements were performed in all 153 patients; no patients declined study participation between randomization and the baseline measurement. Two months later at the posttest, 31 patients (20%) dropped-out of the study, mostly because of worsening illness or death. In the intervention group, two patients were excluded from the study because of intervention bias, as they requested extra conversations with the spiritual counselor for severe issues that came up in the first consultation. A total of 109 patients (71%) completed the questionnaire at 4-month follow-up (see Figure 1). The Little’s MCAR test showed that data were missing completely at random. Missing data were imputed with the mean in all questionnaires, except for the questionnaire on images of god, because more than 50% of the item responses within a scale was absent so they remained missing.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Patient characteristics | Intervention group N (%)—77 patients |

Control group N (%)—76 patients |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 35 (46) | 41 (54) |

| Female | 42 (54) | 35 (46) |

| Age | ||

| Mean | 61 | 64 |

| Standard deviation | 11.13 | 9.55 |

| Cancer primary site | ||

| Breast | 21 (27) | 13 (17) |

| Esophagus | 8 (10) | 9 (12) |

| Colorectal | 16 (21) | 20 (26) |

| Brain | 7 (9) | 3 (4) |

| Gynecological | 7 (9) | 4 (6) |

| Prostate | 4 (5) | 10 (13) |

| Gastric | 2 (4) | 4 (5) |

| Pancreatic | 1 (1) | 7 (9) |

| Other | 11 (14) | 6 (8) |

| WHO score | ||

| 0 | 16 (21) | 18 (24) |

| 1 | 51 (66) | 49 (64) |

| 2 | 10 (13) | 9 (12) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 59 (76) | 53 (70) |

| Living alone | 9 (12) | 16 (21) |

| Living with partner | 9 (12) | 7 (9) |

| Education | ||

| Primary school | 2 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Lower vocational | 8 (11) | 12 (16) |

| Secondary school | 14 (18) | 14 (18) |

| Secondary vocational | 17 (21) | 12 (16) |

| Higher general | 9 (12) | 8 (10) |

| Higher vocational | 19 (25) | 21 (28) |

| University | 8 (10) | 8 (11) |

| Employment | ||

| Paid job | 24 (31) | 17 (22) |

| No paid job | 53 (69) | 59 (78) |

| Pensioners | 32 | 36 |

| Disability insurance | 18 | 16 |

| Volunteer/other | 3 | 6 |

| Religious/non-religious | ||

| Religious | 42 (54) | 38 (50) |

| Non-religious | 35 (46) | 38 (50) |

WHO: World Health Organization.

Figure 1.

CONSORT 2010 flow diagram.

Content of the consultations

A total of 760 life events were mentioned by the group of 77 patients who received the intervention (mean = 8.9, SD = 3.66). The life events were related to family including parents/siblings/children (n = 123), (former) spouse (n = 90), and the birth of children (n = 78). Other frequently mentioned life events were related to cancer (n = 120) and education/work (n = 113). The patient’s own death (n = 19) and birth (n = 18) were mentioned with almost equal frequency. In discussing life goals with the spiritual counselor, a total of 297 life goals were formulated, subdivided into direct goals (n = 14), valuable goals (n = 188), and ultimate goals (n = 95). Direct goals referred to travel plans, hobbies, work, and having fun with others. Valuable goals most frequently regarded the family, being a good husband/wife/parent, enjoying time with loved ones, and being healthy. Ultimate goals were phrased as spreading love, making the world a better place and living a more conscious life.

Patients’ satisfaction with the intervention

A total of 54 (70%) patients completed the evaluation form. In total, 82% of these patients would recommend this intervention to others: it is good to look at your life with an “outsider,” it creates insight into one’s life and it helps obtaining a clear vision on one’s values. Patients rated their experiences with the spiritual counselor on a scale from 1 to 5 with a mean score of 4.5 (0.7 SD, range = 3–5). The consultations were rated 4.3 (0.8 SD, range = 3–5), the handout patients received after the two consultations 3.7 (0.9 SD, range = 1–5) and their experiences with the iPad 3.5 (1.2 SD, range = 1–5). The lower scores for the iPad were mainly due to poor Internet connection that hampered the use of the application and therefore disturbed the consultations. Patients’ overall satisfaction with the intervention was similar among the different spiritual counselors (data not shown).

Primary outcomes: quality of life and SWB

At baseline, mean overall QoL was 74.3 (18.2 SD). Baseline SWB had a mean score on the subscale Meaning/Peace of 22.7 (5.4 SD) and Faith of 5.6 (4.7 SD). No statistically significant differences were found in overall QoL, SWB, or SwL between the intervention and the control group over time (Table 2). Neither were statistically significant differences observed between subgroups of men/women, young (18–54 years)/old (⩾55 years), chemo/no-chemo, and religious/non-religious. Also no substantial differences were observed in outcomes per spiritual counselor; however, these groups were too small to submit to statistical analysis (see Table 3). Note that due to space limitation, not all secondary or tertiary outcomes are discussed in this article.

Table 2.

Results of the primary outcomes QoL and SWB between the intervention and control group over time: baseline, 2 months, and 4 months.

| Different constructs | Time | Intervention group |

Control group |

p | Estimated mean difference | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard error | N | Mean | Standard error | N | |||||

| Quality of Life (QoL) EORTC QLQ C-15 PAL Subscale: Overall quality of life |

1 | 73.8 | 2.10 | 77 | 74.5 | 2.15 | 73 | 0.91 | −0.67 | −6.59 to 5.25 |

| 2 | 72.4 | 2.34 | 57 | 73.9 | 2.29 | 61 | −1.58 | −8.02 to 4.87 | ||

| 3 | 74.2 | 2.50 | 47 | 72.4 | 2.40 | 53 | 1.78 | −5.04 to 8.60 | ||

| Spiritual Well-Being (SWB) FACIT-sp Subscale: Meaning/Peace |

1 | 22.5 | 0.60 | 77 | 22.9 | 0.61 | 76 | 0.86 | −0.41 | −2.09 to 1.27 |

| 2 | 22.0 | 0.65 | 58 | 23.1 | 0.63 | 64 | −1.13 | −2.92 to 0.66 | ||

| 3 | 22.4 | 0.67 | 52 | 22.8 | 0.66 | 56 | −0.40 | −2.26 to 1.46 | ||

| Spiritual Well-Being (SWB) FACIT-sp Subscale: Faith |

1 | 5.4 | 0.53 | 77 | 5.9 | 0.54 | 76 | 0.08 | −0.48 | −1.98 to 1.01 |

| 2 | 5.7 | 0.56 | 57 | 5.0 | 0.55 | 63 | 0.73 | −0.83 to 2.28 | ||

| 3 | 5.4 | 0.57 | 52 | 5.0 | 0.56 | 56 | 0.32 | −1.26 to 1.90 | ||

| Satisfaction with life (SwL) Diener |

1 | 25.7 | 0.68 | 76 | 25.8 | 0.68 | 76 | 0.77 | −0.09 | −1.98 to 1.79 |

| 2 | 25.5 | 0.72 | 57 | 26.2 | 0.70 | 64 | −0.73 | −2.72 to 1.26 | ||

| 3 | 26.0 | 0.74 | 52 | 25.5 | 0.73 | 54 | 0.44 | −1.61 to 2.49 | ||

Mixed models linear analysis was used with fixed factors: time and group.

Table 3.

Results of the primary outcomes QoL and SWB within the intervention group subdivided by spiritual counselor.

| Different constructs | Spiritual counselor 1 |

Spiritual counselor 2 |

Spiritual counselor 3 |

Spiritual counselor 4 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard error | N | Mean | Standard error | N | Mean | Standard error | N | Mean | Standard error | N | |

| Overall QoL T1 | 75.00 | 19.46 | 12 | 84.72 | 13.22 | 12 | 76.67 | 16.10 | 10 | 65.15 | 13.85 | 11 |

| Overall QoL T2 | 68.52 | 21.15 | 9 | 81.82 | 15.73 | 11 | 63.33 | 13.94 | 5 | 66.67 | 18.26 | 6 |

| Overall QoL T3 | 77.78 | 22.05 | 9 | 81.25 | 13.91 | 8 | 80.00 | 7.45 | 5 | 56.67 | 27.89 | 5 |

| Meaning/Peace T1 | 22.25 | 3.79 | 12 | 24.83 | 4.11 | 12 | 23.89 | 4.44 | 10 | 20.82 | 5.64 | 11 |

| Meaning/Peace T2 | 21.93 | 5.84 | 9 | 23.55 | 4.48 | 11 | 22.33 | 3.01 | 6 | 20.17 | 7.47 | 6 |

| Meaning/Peace T3 | 20.78 | 6.08 | 9 | 24.33 | 2.35 | 9 | 22.60 | 4.72 | 5 | 21.17 | 7.11 | 5 |

| Age | 56.42 | 16.81 | 12 | 61.33 | 11.16 | 12 | 62.90 | 7.59 | 10 | 58.11 | 10.37 | 11 |

| WHO score | 1.17 | 0.72 | 12 | 0.83 | 0.58 | 12 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 10 | 1.00 | 0.45 | 11 |

| Satisfaction intervention | 4.13 | 0.71 | 9 | 3.75 | 0.83 | 9 | 3.71 | 0.49 | 5 | 4.00 | 1.05 | 5 |

| Different constructs | Spiritual counselor 5 | Spiritual counselor 6 | Spiritual counselor 7 | |||||||||

| Mean | Standard error | N | Mean | Standard error | N | Mean | Standard error | N | ||||

| Overall QoL T1 | 74.07 | 14.70 | 9 | 73.08 | 19.88 | 13 | 65.00 | 21.44 | 10 | |||

| Overall QoL T2 | 76.19 | 13.11 | 7 | 72.22 | 11.79 | 9 | 74.07 | 22.22 | 9 | |||

| Overall QoL T3 | 79.17 | 15.96 | 4 | 78.57 | 18.54 | 7 | 70.37 | 11.11 | 9 | |||

| Meaning/Peace T1 | 24.11 | 4.37 | 9 | 22.38 | 6.16 | 13 | 19.60 | 7.04 | 10 | |||

| Meaning/Peace T2 | 22.29 | 4.64 | 7 | 23.81 | 3.30 | 9 | 20.56 | 6.02 | 9 | |||

| Meaning/Peace T3 | 27.20 | 3.70 | 5 | 22.75 | 4.62 | 8 | 20.56 | 4.77 | 9 | |||

| Age | 58.11 | 10.37 | 9 | 63.54 | 8.61 | 13 | 59.80 | 11.58 | 10 | |||

| WHO score | 1.00 | 0.00 | 9 | 0.92 | 0.64 | 13 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 10 | |||

| Satisfaction intervention | 3.95 | 0.76 | 4 | 4.00 | 0.66 | 7 | 4.28 | 0.54 | 9 | |||

WHO: World Health Organization; QoL: quality of life; SWB: spiritual well-being; CI: confidence interval.

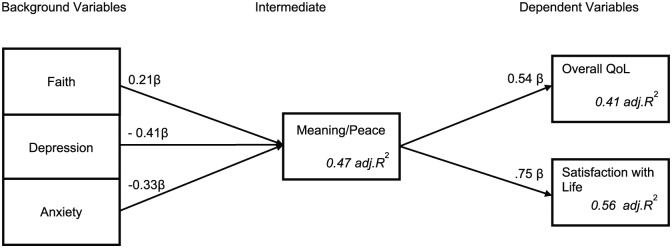

Explorative analysis

Using multiple regression analysis with the enter approach, the post hoc explorative analysis showed direct and indirect effects on the primary outcomes QoL and SWB. The latter was subdivided into two subscales: Meaning/Peace and Faith. Out of all the outcome measures examined, Depression, Anxiety, and Faith were found significantly associated with Meaning/Peace (adj. R2 = 0.47). Meaning/Peace was significantly associated with QoL (adj. R2 = 0.41) and SwL (adj. R2 = 0.56) (see Table 4). To evaluate the magnitude of effect, Cohen’s f2 can be used, that is, 0.02 = small, 0.15 = medium, and 0.35 = large.45,46 For Meaning/Peace, Cohen’s f2 = 0.88, Quality of Life f2 = 0.69, and Satisfaction with Life f2 = 1.26; therefore, all effects can be regarded as strong.

Table 4.

Explorative analysis of the relationship between QoL and SWB and possibly influencing factors.

| Independent variable | Dependent variable | Standardized coefficients betaa | t | Sig. | R | R 2 | Adj. R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| treatment_chemo | Meaning/Peace | 0.077 | 1.037 | 0.302 | 0.726 | 0.527 | 0.468 |

| gender_female | −0.001 | −0.012 | 0.991 | ||||

| age_0-60 | <0.001 | −0.003 | 0.998 | ||||

| education_higher | −0.047 | −0.649 | 0.518 | ||||

| religious_yes | 0.04 | 0.513 | 0.609 | ||||

| anxiety | −0.331 | −4.308 | <0.001 | ||||

| depression | −0.405 | −5.186 | <0.001 | ||||

| religious salience | −0.069 | −0.713 | 0.477 | ||||

| christian | −0.036 | −0.334 | 0.739 | ||||

| world | 0.113 | 1.545 | 0.125 | ||||

| transcendental | −0.09 | −0.87 | 0.386 | ||||

| not transcen. | 0.014 | 0.181 | 0.856 | ||||

| faith | 0.207 | 2.677 | 0.009 | ||||

| treatment | Overall QoL | −0.043 | −0.547 | 0.586 | 0.697 | 0.485 | 0.408 |

| gender | 0.121 | 1.567 | 0.12 | ||||

| age | −0.093 | −1.151 | 0.252 | ||||

| education | −0.051 | −0.655 | 0.514 | ||||

| religious | −0.147 | −1.731 | 0.087 | ||||

| anxiety | −0.003 | −0.033 | 0.974 | ||||

| depression | −0.247 | −2.742 | 0.007 | ||||

| religious salience | 0.123 | 1.191 | 0.237 | ||||

| christian | −0.165 | −1.45 | 0.15 | ||||

| world | 0.02 | 0.257 | 0.798 | ||||

| transcendental | 0.058 | 0.525 | 0.601 | ||||

| not transcen. | −0.034 | −0.398 | 0.691 | ||||

| faith | 0.012 | 0.14 | 0.889 | ||||

| meaning/peace | 0.536 | 5.108 | <0.001 | ||||

| treatment | Satisfaction with Life | −0.058 | −0.844 | 0.401 | 0.784 | 0.614 | 0.558 |

| Gender | 0.029 | 0.449 | 0.654 | ||||

| Age | −0.097 | −1.412 | 0.161 | ||||

| Education | 0.092 | 1.379 | 0.171 | ||||

| Religious | −0.076 | −1.061 | 0.291 | ||||

| Anxiety | −0.019 | −0.243 | 0.808 | ||||

| Depression | −0.06 | −0.74 | 0.461 | ||||

| religious salience | −0.136 | −1.547 | 0.125 | ||||

| Christian | −0.011 | −0.117 | 0.907 | ||||

| World | −0.041 | −0.601 | 0.549 | ||||

| Transcendental | 0.083 | 0.874 | 0.384 | ||||

| not transcen. | 0.047 | 0.641 | 0.523 | ||||

| Faith | 0.025 | 0.335 | 0.738 | ||||

| meaning/peace | 0.753 | 8.167 | <0.001 |

QoL: quality of life; SWB: spiritual well-being.

A multiple regression analysis was used with an enter approach.

The higher the absolute value of the beta, the more influential the independent variable on the dependent variable.

Discussion

This is the first randomized study evaluating the effect of two structured reflections discussing life events and life goals on QoL and SWB in patients with advanced cancer. Contrary to our expectations, we found no differences in QoL and SWB between the intervention and control group. Two main reasons for the lack of efficacy could be identified. First, our intervention involved two 1-h sessions. This time investment may have been too short to evoke a major change in patients’ way of looking at their lives. A spiritual intervention may be more effective when it takes into account the ongoing process of defining and reconstructing one’s life story and this process may not be sufficiently stimulated by a brief intervention.47 This is especially true considering that QoL is also determined by other factors, such as symptoms induced by treatment or the progression of disease which may alter QoL significantly in the course of time. When looking at QoL over time between both groups (see Table 2), the outcomes are quite surprising. Within the control group the overall QoL deteriorates, while the intervention group has a rather high overall QoL at time point three. These changes are mainly due to the drop out of patients who had a poorer QoL to start with. Especially in palliative patients, it is quite hard to establish a meaningful difference in QoL. Although we believe that both QoL and SWB are important concepts to take into account, more focused outcome measures are required that take into account subtle changes in life evaluation.

Second, the interview model of our intervention is aimed at stimulating patients’ own reflection and reconstruction of the life event in accordance with their life view in order to improve well-being. We did not include concrete sources that could have provided patients with meaning. Offering a reflection only may be insufficient to directly improve the well-being of our patient population.5 Of note, reflecting on a life event and successful integrating it into one’s life is, at least in part, determined by one’s worldview.47–50 This worldview functions as a framework in which the meaning-making takes place and sources of meaning are located, varying from commitment to spiritual practices to engagement in volunteer work.51 Considering the relatively low baseline scores for Meaning/Peace and Faith, our patient population may not have had access to a sufficiently broad spectrum of meaningful sources.52,53 As shown in our explorative analysis, the experience of Meaning/Peace is of significant value to patients’ well-being. Therefore, future intervention studies may be improved by including ways to access sources of meaning, for example, by pieces of art, movies, or poems, which may help patients to define and attribute meaning to their lives.54

Importantly, the outcomes of the exploratory regression analyses lead to a new conceptual model for understanding the relationship between QoL and SWB, as shown in Figure 2. A reasonably large group of studies suggests that SWB significantly contributes to QoL by providing meaning and peace.29,55,56 There are, however, also studies suggesting that the association between SWB and QoL is more complex and indirect.41 From our regression analysis, we may conclude that Meaning/Peace is significantly associated with QoL, even after adjustment for covariates. This finding implies that by improving Meaning/Peace also QoL will increase. We have yet to explore which patients will benefit most of an increased experience of Meaning/Peace in order to offer personalized interventions.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of the relationship between QoL, SWB, and relevant variables. Background variables significantly influencing Meaning/Peace are displayed on the left. In the middle, Meaning/Peace is placed as an intermediate factor influencing QoL and SwL. On the right side the two dependent variables as influenced by Meaning/Peace. Linear regression analysis was used for this conceptual model.

Furthermore, despite the lack of statistically significant outcomes for the effect of the intervention, more than 80% of patients from the intervention group would recommend this intervention to people they knew because it gave them insight into their lives and helped them to get a clearer vision on their values. This finding is important while it shows the need for structured spiritual interventions that is currently not provided in the regular healthcare system for palliative cancer patients. Other studies have shown that life reflection can be related to the accumulation of self-insight and personal growth57 and suggests that QoL and SWB might not be the only relevant outcome measures to take into account for our patients.58 We do however believe that both QoL and SWB are important concepts to take into account especially in palliative care. Nevertheless, new outcome measures that are sensitive to spiritual interventions and relevant to healthcare are urgently needed. Finally, it is also worthy to note that the intervention did not cause any harm to the participating patients.

Strengths and limitations

First, the effect of the intervention is largely determined by the quality of the consultations by the spiritual counselor. Therefore, we have put much effort in the training of the spiritual counselors.27 We only started the RCT when both the spiritual counselor and the research team were confident of their ability to perform the intervention. Also, we did not find significant differences in patients’ outcomes among spiritual counselors, nor did we find significant differences in patients’ evaluations of the intervention. Second, our study was carried out in the Netherlands; therefore, the generalization of our study results may be limited by the context of Western Europe. This implies that the effect of our intervention may have been different in, for example, patients from the United States. Recently, we found that although four different modes of relating to contingency that we found in a Dutch study population can also be found in an American advanced cancer patient population, differences were found in the extend by which American patients described the fourth mode of relating to contingency, that is, the “receiving” mode.59,60 This could suggest that American patients could be more open to the intervention that we developed. Furthermore, the generalization of our results may be limited by an overrepresentation in our study population of patients who are willing to talk about their life. Unfortunately, we do not have information on the patients that were asked by the physicians to participate in this study, but declined participation. A strength was the involvement in multiple centers, including academic and non-academic hospitals which improve the generalizability of our results compared to single-center studies. Another strength was the randomization, precluding bias in assigning patients to the intervention or control group. Finally, 50% of our study population was male, and we regard this as a strong point of our study because women are often over-represented in spiritual studies because of their affinity with the subject.61

Conclusion

In conclusion, although the intervention was well perceived by patients and spiritual counselors, no significant difference in QoL and SWB was demonstrated between intervention and control groups. Future interventions by spiritual counselors aimed at improving QoL and SWB should focus on the provision of sources of meaning and peace.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to all the patients who were willing to participate in our study and all oncologists (in training), oncology nurses, and data managers who participated in patient inclusion. We thank Simon Evers and Stephanie Verhoeven for participating in the training, Marianne Snijdewind and Alexandra Calor for their assistance, and Niek de Jonge for helping out with the statistics. H.W.M.V.L., M.S.-R., and J.B.A.M.S. conceived the study and secured funding. R.K., H.W.M.V.L. and M.S.-R. oversaw the study. A.M.W., H.-J.K., C.G., J.S., N.A.W.P.S., F.Y.F.L.D.V., W.G.M., I.D.H., and H.W.M.V.L. included patients in the study. R.K. checked and cleaned the data. R.K., M.S.-R., and M.G.H.V.O. analyzed the data. H.W.M.V.L. provided critical comments and advise in all analysis stages. R.K., H.W.M.V.L., and M.S.-R. wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. R.K. is the guarantor. Trial Registration: The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01830075.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Dutch Cancer Society/Alpe d’HuZes (grant no. UVA 2011–5311), Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies, and an anonymous beneficiary.

ORCID iDs: Renske Kruizinga  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0922-3940

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0922-3940

Michael Scherer-Rath  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7652-8213

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7652-8213

References

- 1. Markowitz AJ, McPhee SJ. Spiritual issues in the care of dying patients: “… it’s okay between me and god.” JAMA 2006; 296(18): 2254–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Salmon P, Manzi F, Valori RM. Measuring the meaning of life for patients with incurable cancer: the Life Evaluation Questionnaire (LEQ). Eur J Cancer 1996; 32A(5): 755–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benzein E, Norberg A, Saveman BI. The meaning of the lived experience of hope in patients with cancer in palliative home care. Palliat Med 2001; 15(2): 117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Puchalski CM, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the consensus conference. J Palliat Med 2009; 12(10): 885–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McClain CS, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W. Effect of spiritual well-being on end-of-life despair in terminally-ill cancer patients. Lancet 2003; 361(9369): 1603–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization. The definition of palliative care, http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (2002, accessed 20 March 2017).

- 7. Lin HR. Searching for meaning: narratives and analysis of US-resident Chinese immigrants with metastatic cancer. Cancer Nurs 2008; 31(3): 250–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Balboni TA, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, et al. Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25(5): 555–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Breitbart W. Spirituality and meaning in supportive care: spirituality-and meaning-centered group psychotherapy interventions in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 2002; 10(4): 272–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Balboni TA, Paulk ME, Balboni MJ, et al. Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28(3): 445–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pearce MJ, Coan AD, Herndon JE, et al. Unmet spiritual care needs impact emotional and spiritual wellbeing in advanced cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2012; 20(10): 2269–2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cole BS. Spiritually-focused psychotherapy for people diagnosed with cancer: a pilot outcome study. Ment Health Rel Cult 2005; 8: 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Taylor EJ, Mamier I. Spiritual care nursing: what cancer patients and family caregivers want. J Adv Nurs 2005; 49(3): 260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kruizinga R, Hartog ID, Jacobs M, et al. The effect of spiritual interventions addressing existential themes using a narrative approach on quality of life of cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology 2016; 25(3): 253–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krauss SE. Research paradigms and meaning making: a primer. Qual Report 2005; 10(4): 758–770. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen CP. On exploring meanings: combining humanistic and career psychology theories in counselling. Couns Psychol Q 2001; 14(4): 317–330. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moadel A, Morgan C, Fatone A, et al. Seeking meaning and hope: self-reported spiritual and existential needs among an ethnically diverse cancer patient population. Psychooncology 1999; 8(5): 378–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schroevers M, Kraaij V, Garnefski N. How do cancer patients manage unattainable personal goals and regulate their emotions. Br J Health Psychol 2008; 13(Pt 3): 551–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Emmons RA. Personal goals, life meaning, and virtue: wellsprings of a positive life. In: Keyes C, Haidt J. (eds) Flourishing, positive psychology and the life well-lived. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2003, pp. 105–128. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Emmons RA. The psychology of ultimate concerns: motivation and spirituality in personality. New York: Guilford Publications, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Scherer-Rath M, van den Brand JAM, van Straten C, et al. Experience of contingency and congruence of interpretation of life-events in clinical psychiatric settings: a qualitative pilot study. J Empir Theol 2012; 25: 127–152. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Westerhof GJ, Bohlmeijer ET. Psychologie van de levenskunst. Amsterdam: Boom, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kruizinga R, Scherer-Rath M, Schilderman JB, et al. The Life in Sight Application Study (LISA): design of a randomized controlled trial to assess the role of an assisted structured reflection on life events and ultimate life goals to improve quality of life of cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2013; 13: 360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sawatzky R, Ratner PA, Chiu L. A meta-analysis of the relationship between spirituality and quality of life. Soc Indic Res 2005; 72(2): 153–188. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Van den Brand JAM, Hermans CAM, Scherer-Rath M, et al. An instrument for reconstructing interpretation of life stories. In: Ganzevoort RR, de Haardt M, Scherer-Rath M. (eds) Religious stories we live by: narrative approaches in theology and religious studies. Leiden: Brill, 2013, pp. 169–182. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scherer-Rath M. Narrative reconstruction as creative contingency. In: Ganzevoort RR, de Haardt M, Scherer-Rath M. (eds) Religious stories we live by: narrative approaches in theology and religious studies. Leiden: Brill, 2013, pp. 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kruizinga R, Helmich E, Schilderman Scherer-Rath M, et al. Professional identity at stake: a phenomenological analysis of spiritual counselors’ experiences working with a structured model to provide care to palliative cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2016; 24(7): 3111–3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Aaronson NK, et al. The development of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL: a shortened questionnaire for cancer patients in palliative care. Eur J Cancer 2006; 42(1): 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, et al. A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psychooncology 1999; 8(5): 417–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, et al. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess 1985; 49: 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PPA, et al. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med 1997; 27(2): 363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A, et al. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007; 39(2): 175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Snyder CF, Blackford AL, Sussman J, et al. Identifying changes in scores on the EORTC-QLQ-C30 representing a change in patients’ supportive care needs. Qual Life Res 2015; 24(5): 1207–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Scott NW, Fayers P, Aaronson NK, et al. EORTC quality of life group. EORTC QLQ-C30 Reference Values Manual, 2008, http://www.eortc.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/02/reference_values_manual2008.pdf

- 35. Nguyen T, Jiang J. Simple estimation of hidden correlation in repeated measures. Stat Med 2011; 30(29): 3403–3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bouca-Machado R, Rosario M, Alarcao J, et al. Clinical trials in palliative care: a systematic review of their methodological characteristics and of the quality of their reporting. BMC Palliat Care 2017; 16(1): 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Parker PA, Baile WF, deMoor CD, et al. Psychosocial and demographic predictors of quality of life in a large sample of cancer patients. Psychooncology 2003; 12(2): 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Frick E, Tyroller M, Panzer M. Anxiety, depression and quality of life of cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy: a cross-sectional study in a community hospital outpatient centre. Eur J Cancer Care 2007; 16(2): 130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. So WK, Marsh G, Ling W, et al. Anxiety, depression and quality of life among Chinese breast cancer patients during adjuvant therapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2010; 14(1): 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Murphy PE, Fitchett G, Stein K. Re-examining the contributions of faith, meaning, and peace to quality of life: a report from the American Cancer Society’s Studies of Cancer Survivors-II (SCS-II). Ann Behav Med 2016; 50(1): 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cotton SP, Levine EG, Fitzpatrick CM, et al. Exploring the relationships among spiritual well-being, quality of life, and psychological adjustment in women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 1999; 8(5): 429–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Levine EG, Yoo GJ, Aviv C. Predictors of quality of life among ethnically diverse breast cancer survivors. Appl Res Qual Life 2016; 12: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mehdi T, Bashardoost N, Ahmadi M. Kernel smoothing for ROC curve and estimation for thyroid stimulating hormone. Int J Public Health Res 2011; 1: 239–242. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Integraal Kankercentrum Nederland. Cijfers over kanker, http://www.cijfersoverkanker.nl/ (2016, accessed 20 March 2017).

- 45. Selya AS, Rose JS, Dierker LC, et al. A practical guide to calculating Cohen’s f2, a measure of local effect size, from PROC MIXED. Front Psychol 2012; 3: 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cohen JE. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988, pp. 473–480. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ganzevoort RR, Bouwer J. Life story methods and care for the elderly: an empirical research project in practical theology. In: Ziebertz HG, Schweitzer F. (eds) Dreaming the land, theologies of resistance and hope. Münster: LIT Verlag, 2007, pp. 140–151. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kraft CH. Worldview for Christian witness. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jenkins RA, Pargament KI. Religion and spirituality as resources for coping with cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol 1995; 13(1–2): 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Koenig HG, Larson DB, Larson SS. Religion and coping with serious medical illness. Ann Pharmacother 2001; 35(3): 352–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schnell T. Individual differences in meaning-making: considering the variety of sources of meaning, their density and diversity. Pers Indiv Differ 2011; 51(5): 667–673. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jansen G, de Graaf ND, Need A. Explaining the breakdown of the religion–vote relationship in The Netherlands, 1971–2006. West Eur Polit 2012; 35(4): 756–783. [Google Scholar]

- 53. De Graaf ND, Te Grotenhuis M. Traditional Christian belief and belief in the supernatural: diverging trends in the Netherlands between1979 and 2005? J Sci Study Relig 2008; 47(4): 585–598. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Visser A, Garssen B, Vingerhoets A. Spirituality and well-being in cancer patients: a review. Psychooncology 2010; 19(6): 565–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fitchett G, Peterman A, Cella D. Spiritual beliefs and quality of life in cancer and HIV patients. In: Paper presented at the 3rd world congress on psycho-oncology, New York, New York, USA, 3–6 October 1996, pp. 439–450. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Riley BB, Perna R, Tate DG, et al. Types of spiritual well-being among persons with chronic illness: their relation to various forms of quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79(3): 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Staudinger UM. Life reflection: a social–cognitive analysis of life review. Rev Gen Psychol 2001; 5(2): 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- 58. van de Geer J, Leget C. How spirituality is integrated systemwide in the Netherlands palliative care national programme. Progr Palliat Care 2012; 20(2): 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kruizinga R, Hartog ID, Scherer-Rath M, et al. Modes of relating to contingency: an exploration of experiences in advanced cancer patients. Palliat Support Care 2017; 15(6): 444–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kruizinga R, Jafari N, Scherer-Rath M, et al. Relating to the experience of contingency in patients with advanced cancer: an interview study in US patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018; 55(3): 913–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wink P, Dillon M. Religiousness, spirituality, and psychosocial functioning in late adulthood: findings from a longitudinal study. Psycholog Relig Spiritual 2008; 1: 102–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]