Abstract

Metallic materials have been extensively applied in clinical practice due to their unique mechanical properties and durability. Recent years have witnessed broad interests and advances on surface functionalization of metallic implants for high-performance biofunctions. Calcium phosphates (CaPs) are the major inorganic component of bone tissues, and thus owning inherent biocompatibility and osseointegration properties. As such, they have been widely used in clinical orthopedics and dentistry. The new emergence of surface functionalization on metallic implants with CaP coatings shows promise for a combination of mechanical properties from metals and various biofunctions from CaPs. This review provides a brief summary of state-of-art of surface biofunctionalization on implantable metals by CaP coatings. We first glance over different types of CaPs with their coating methods and in vitro and in vivo performances, and then give insight into the representative biofunctions, i.e. osteointegration, corrosion resistance and biodegradation control, and antibacterial property, provided by CaP coatings for metallic implant materials.

Keywords: Calcium phosphates, Metallic implant materials, Surface biofunctionalization, Osteointegration, Biodegradation

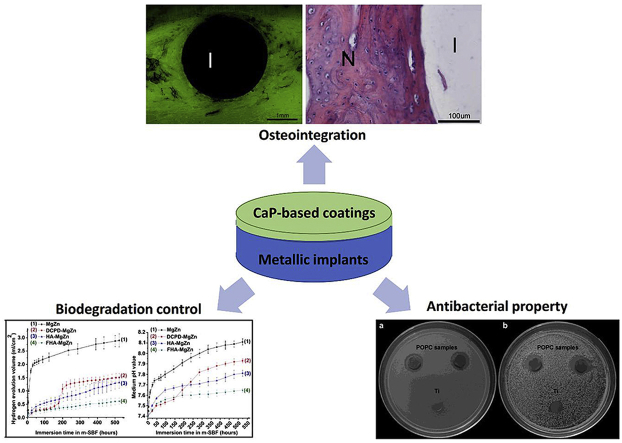

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Discussions on the various biofunctions of CaP coatings.

-

•

Summary of different types of CaPs and their recent development.

-

•

Summary of CaP coating methods and selection criteria.

1. Introduction

Metallic materials have been extensively exploited in the clinical practice as early as 200 A.D. when a wrought iron-based material was used to implant in the human bone [1]. Compared to polymers and ceramics, metallic materials have been applied clinically on account of appropriate physical and mechanical properties [2]. The most common inert metallic implants so far are three types of alloys namely stainless steels, titanium (Ti) alloys, and cobalt-chromium alloys [3], while biodegradable metals, including magnesium (Mg), iron (Fe), and zinc (Zn), have been pursued recently as a new generation of biomaterials for temporary applications [[4], [5], [6], [7], [8]]. However, the bioactivities of all these insert and biodegradable metals are somewhat suboptimal and limited, and thus some functionalities is required for them when applied in specific clinical practice [9].

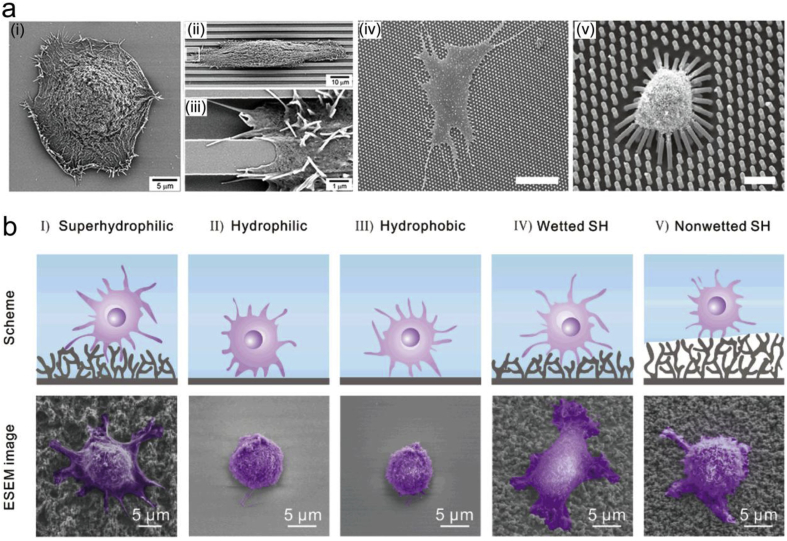

The biomaterials surface properties, including surface morphology and wettability, are critical when implanted in the human body [10,11]. For example, surface morphology has direct and significant effects on the cell capabilities and functions (Fig. 1a) [[12], [13], [14]], while the cell adhesion on the superhydrophilic and wetted superhydrophobic surfaces is stronger than those on the other surfaces, including nonwetted superhydrophobic surface [15], as shown in Fig. 1b. To achieve the biocompatibility and biofunctions on the implant materials, surface biofunctionalization is one of the easiest ways to change the surface properties which can improve the surface bioactivity, eliminate or control the degradation rate, and prevent implant-related infections, etc. [[16], [17], [18], [19]]. For example, surface modification with appropriate coatings can create a favorable surface morphology for the adsorption of proteins in the interactions with biological fluids, and thus promote the cell–extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions and the production of growth factors [20,21]. Different coating phases and the incorporation of various biofunctional ions into the phase lattice should also be considered in the evaluation of cell growth and functions [20].

Fig. 1.

Influence of surface properties of the implant material on the cell behaviors. (a) SEM images show different cell morphology and adhesion behaviors of human corneal epithelial cells cultured on (i) smooth and (ii–iii) groove patterned silicon oxide substrates, and human mesenchymal stem cells on poly(dimethylsiloxane) micropillar of different heights of (iv) 0.97 μm and (v) 12.9 μm. (b) Cell adhesion behaviors of NIH/3T3 cells on surfaces with wettability gradient. The cells displayed extended pseudopodia and adhered firmly on I and IV regions; while the cells showed much lower attachment on II, III and V regions. (Parts (i-iii) in (a) are reproduced with permission from Ref. [12], parts (iv-v) in (a) are reproduced with permission from Ref. [13], and (b) is reproduced with permission from Ref. [15].). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Compared to other treatment technologies, surface modifications and functionalizations provide a possibility to modify the surface properties of biomaterials to be suitable for specific biomedical applications [19,20,22]. As the main inorganic component in bone tissue [23], calcium phosphate (CaP) possesses inherent biocompatibility when applied as biomaterials in human body [24]. Many attentions have been paid to CaP coatings on different metallic substrates. For example, Dorozhkin [25] and Shadanbaz et al. [26] provided excellent overviews of CaP coatings on magnesium alloys, while Paital et al. [27] focused on Ti alloys. There were also some other representative reviews with a specific focus on new bone osteogenesis enhancement [20] or using a specific method, such as sputtering [28] or biomimetic mineralization [29]. Here, we provide a different angle to review and summarize the biofunctionalization of CaP coatings on metallic implants. We first introduce different types of CaPs and their coating techniques and then highlight the featured biofunctions offered from CaP coatings for metallic implants.

2. Different types of calcium phosphates

There are different compounds of CaPs synthesized and applied clinically, and their major properties are summarized and listed in Table 1 [25,26,30,31]. The solubility of CaPs is a significant parameter when considered as implant materials, especially in terms of controlling the cytotoxicity [32] and inflammatory response [33]. The solubility coefficient, stability, and phase transformation of these CaPs are heavily dependent on environmental conditions, as shown in Table 1. Their in vitro cytocompatibility have been studied and proven with several cell lines, including fibroblast cells, pre-osteoblastic cells, bone marrow cells, and mesenchymal stem cells derived from mice, rabbits, and humans, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 1.

| Ca/P | Compound | Formula | Stability (solubility/g l−1 at 25 °C) | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | Monocalcium phosphate monohydrate (MCPM) | Ca(H2PO4)2·H2O | pH 0–2; (∼18) | The most acidic and water-soluble CaP phase; sealer in dentistry; bone cement with β-TCP; |

| 0.5 | Monocalcium phosphate anhydrous (MCPA) | Ca(H2PO4)2 | >100 °C; (∼17) | Slightly inferior solubility and similar properties to MCPM; |

| 1.0 | Dicalcium phosphate dihydrate (DCPD), mineral brushite, | CaHPO4·2H2O | pH 2–6; (∼0.088) | Greater solubility; Higher supplement for Ca2+ and PO43− ions; precursor to DCPA (pH < 6), OCP (pH ≈ 6–7), or HA (pH > 7); |

| 1.0 | Dicalcium phosphate anhydrous (DCPA), mineral monetite, | CaHPO4 | >100 °C and pH 4–5; (∼0.048) | Slightly inferior solubility to DCPD; higher release of Ca2+ and PO43− ions; Precursor to HA; |

| 1.33 | Octacalcium phosphate (OCP) | Ca8(HPO4)2(PO4)4·5H2O | pH 5.5–7.0; (∼0.0081) | Most stable at a physiological pH and temperature; the initial crystalline phase in the in vivo formation of HA; transform to HA at alkali conditions; |

| 1.5 | α-Tricalcium phosphate (α-TCP) | α-Ca3(PO4)2 | Only obtained when sintered at above 1250 °C; (∼0.0025) | Greater solubility than HA; a precursor of OCP or CDHA via hydrolysis in phosphoric acid; quick resorption rate—faster than the formation rate of new bone; common component of CaP cement; |

| 1.5 | β-Tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) | β-Ca3(PO4)2 | Only obtained when sintered at 900–1100 °C; (∼0.0005) | Greater solubility than HA; superior stability to α-TCP; CaP bone cement; dietary food supplement; biphasic bioceramic or coating in combination with HA; |

| 1.2–2.2 | Amorphous calcium phosphates (ACP) | CaxHy(PO4)z·nH2O n = 3–4.5; 15–20% H2O | pH ∼5–12; pH-depending solubility: 25.7 ± 0.1 (pH 7.40) | Glass-like physical properties; a transient precursor phase of other CaPs in aqueous systems; release calcium and phosphate ions in the acidic environment; |

| 1.5–1.67 | Calcium-deficient hydroxyapatite (CDHA or Ca-def HA) | Ca10−x(HPO4)x(PO4)6−x(OH)2−x (0 < x < 1) |

pH 6.5–9.5; (∼0.0094) | Poorly crystalline and of submicron dimensions; convert to β-TCP or HA+β-TCP when heating above 700 °C; a compound of all commercially available CaP cement; |

| 1.67 | Hydroxyapatite (HA, or HAp) | Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2 | pH 9.5–12; thermally stable; (∼0.0003) | Naturally occurring mineral form of calcium apatites; major mineral component of bones and teeth; bioactive and osteoconductive; coating on orthopedic and dental implants; slower resorption rates in vivo; |

| 2 | Tetracalcium phosphate (TTCP, or TetCP) mineral hilgenstockite, | Ca4(PO4)2O | Only obtained when sintered at above 1300 °C without water vapor; (∼0.0007) | Metastable in wet environments and slowly hydrolyzes to HA and calcium hydroxide; combine with other CaPs or polymers to form various self-setting cement and biocomposites. |

Table 2.

In vitro and in vivo studies of CaP ceramics for biomedical applications.

| Compound | Improved in vitro cytocompatibility | Enhanced in vivo bone regeneration |

|---|---|---|

| MCPM | Pure MCPM is not biocompatible with bone due to its acidity [30]; β-TCP/MCPM: pre-osteoblast cell [34]; | β-TCP/MCPM: femoral condyle of rabbits [34]; |

| DCPD | Murine: pre-osteoblastic macrophage cells [35,36], fibroblastic cells [37], mesenchymal stem cells [38]; mouse bone marrow cells [39] | Proximal tibial plateau [39] and bone-tendon interface [40] of rabbits; parietal bones [41] and femora and tibia [42] of sheep; cranial bone repair and augmentation of human [43]. |

| DCPA | Mouse bone marrow cells [39]; human osteoblast cells [44]. | Tibia [39] and femora [45] of rabbits; alveolar sockets of human [46]. |

| OCP | Murine fibroblasts [47]; rat bone marrow cells [48]; human osteoblast cells [49] | Crania [50,51], calvaria and tibia of rats [52,53]; |

| α-TCP | Newborn mouse calvaria-derived osteoblast cells [54]; human: osteoblast-like cells [55], primary osteoblasts, bone marrow mesenchymal cells and non-adherent myelomonocytic cells [56]; | Tibial head of minipigs [57]; cranial bone [58] and calvaria [59] of rabbits; |

| β-TCP | Mouse osteoblast cells [60]; human: osteoblast cells [61,62], fibroblasts and umbilical vein endothelial cells [63]; | Calvaria of Rats [64]; tibia of goats [65,66]. |

| ACP | Mg2+ stabilized nanospheres: mouse osteoblast cells [67]. | Rat aorta arteries [68]. |

| CDHA | Rabbits mesenchymal stem cells [69]; human bone marrow stromal cells [70]; | Ectopic bone of mice [71]; mandible of rabbits [69]; |

| HA | Ovine tibial osteoblast cells [72]; rat bone marrow cells [73]; human keratinocyte cell lines [74]; |

Hemi-mandible of minipigs [75]; femora of rabbits [76]; dorsal muscles of dogs [77]; femora [78] and tibia [79] of sheep; human middle ear [80]; |

| TTCP | Marginal activity of neonatal rabbit osteoclast cells [81]; mouse calvaria-derived MC3T3-E1 cells [54]; calvarial osteogenic cells [82]; | Cement with (NH4)2HPO4 as liquid: cortical and cancellous femur in rabbits [83]; cement with polyacrylic acid/itaconic acid copolymer: crania of rats [84]; |

It has been shown that cell behaviors might be different in vitro from in vivo, so it is vital to inspect and understand the interaction of the implants with tissues in a living system. Different animal models are chosen for various purposes, e.g. rat or mice for subcutaneous examinations, rabbit for surface interaction studies with femoral bone, and large animal models such as sheep and goats to verify in a more realistic clinical situation [85], and the chosen implanting position is usually the femur, tibia, or mandible bones [86]. CaPs has been shown to be osteoconductive, but not osteoinductive [87,88]. The osteoconductive properties depend on several architectural features of CaPs, such as surface geometry, topography, chemistry and charge, porosity, and pore size.

3. Calcium phosphate coating methods

The biomedical development of CaP-based bulk materials is limited by their low ductility due to the weak ionic bonds [89]. Thus, CaPs were developed as bone cement to fill bone gaps in clinical practice and coating materials on the implant materials to enhance the surface biocompatibility and biofunctions [20,[25], [26], [27]]. It have been demonstrated with many previous studies that various CaP coatings could significantly improve the biological performances of metallic implants [20]. Both physical and chemical methods have been developed to obtain CaP coatings on metallic materials. Physical deposition currently can be achieved by plasma spraying, radio frequency magnetron sputtering, pulsed laser deposition (PLD), and ion-beam-assisted deposition (IBAD). Chemical methods include biomimetic precipitation, electrochemical deposition, micro-arc oxidation, electrophoresis, sol-gel, chemical conversion, and hydrothermal deposition. Details of their characters, development, and clinical applications have been reviewed previously [20,[25], [26], [27],85,90].

As the most common method clinically used for CaP coatings, plasma spraying is always the first choice to produce thick coatings on components with regular shapes, especially for the high-temperature CaP phases, such as tricalcium phosphate (TCP) and tetracalcium phosphate (TTCP), as shown in Table 1. However, tensile stresses during the heating and cooling process potentially result in the cracks initiation and film delamination, especially when applied in the long-term clinical applications. This is a common problem for all the high-temperature treatments on the metallic materials surface. To overcome this drawback, radio frequency magnetron sputtering and PLD methods were introduced to produce thin but dense and adhesive coatings. As-deposited amorphous CaP coatings could transfer to crystalline structure and decrease the dissolution after a necessary post-heat treatment [91]. However, it is difficult to control the phase conversion and production in the coating process, and the instruments for both methods are costly, which limits the commercial applications of these two methods.

Compared to the physical deposition techniques, wet-chemical techniques have much lower requirement on the set-up and instruments. Sol-gel method is a straightforward and early developed technique to produce thin hydroxyapatite (HA) coatings on Ti alloys [92,93]. It also requires a sintering process to increase the crystallization, similar to the physical deposition techniques, but it has lower sintering temperatures (200–600 °C) and much higher purity composition [94] and could also act as a bioactive sealing layer for porous coatings [95]. The weaknesses of the sol-gel coating are the low wear-resistance and expensive raw materials. Biomimetic precipitation is a special method to mimic the biomineralization process of natural CaP and thus the coating environment is a simulated physiological environment at low temperature [29]. It usually requires a long immersion time and pre-activating treatment to accelerate the apatite nucleation on the metallic implants. Cathodic electrodeposition and chemical conversion methods of CaP coatings can be carried out in the ambient temperature, mostly in acidic calcium phosphate solutions, and have short coating process and excellent conformability to the complex shape of the substrate [96]. Typically, the as-deposited coating is mainly composed of dicalcium phosphate dihydrate (DCPD), which converts to HA coating after the post alkali treatments [[97], [98], [99]]. A superior characteristic of the chemical conversion deposition is that it does not require the external electrical circuit. The heterogeneity of electrochemical potential between different phases in easily-corroded alloys (e.g., Mg, Zn, Fe alloys) provide the driving force for conversion coatings [[100], [101], [102], [103]].

When choosing the coating method, the substrate metal should be taken into consideration firstly. For example, all the physical and sol-gel methods are generally suitable for the high-melting-point metals and alloys (e.g., Ti, Fe), while it is better to use the wet-chemical methods for low-melting-point metals and alloys (e.g., Mg, Zn). The chemical conversion method can only be applied to easily-corroded alloys (e.g., Mg, Zn and Fe based alloys). The coating thickness is another important factor when choosing the appropriate coating method. Plasma spraying is suitable for thick coatings (30–200 μm), and wet chemical methods like sol-gel, biomimetic immersion, or chemical conversion can only produce lower thicknesses of 1–20 μm, while sputtering or laser methods can produce even thinner coatings of 0.1–5 μm. The coating thickness of electrodeposited coatings can be varied depending on the coating parameters [28,90]. In addition, the coating adhesion, application, and the cost should be considered in the clinic practice [104]. For example, the coating adhesion strength on the bone implants should be higher than hard tissue. The coating on the bone screws should be stiff enough to ensure the implantation process without coating cracking or peeling. Moreover, it is a good trend to apply the combined methods of the above methods and technology and achieve the formation of bio-composites and multilayer coatings [105,106]. This is a potential routine to overcome the drawbacks of the single method and produce CaP-based coatings with novel properties and biological performance.

4. Surface biofunctions with calcium phosphate coatings

The CaP coatings could significantly change the surface morphology and chemistry of metallic implants and thus improve their surface biofunctions, including the osteointegration, corrosion and degradation performance, and antibacterial property.

4.1. Osteointegration

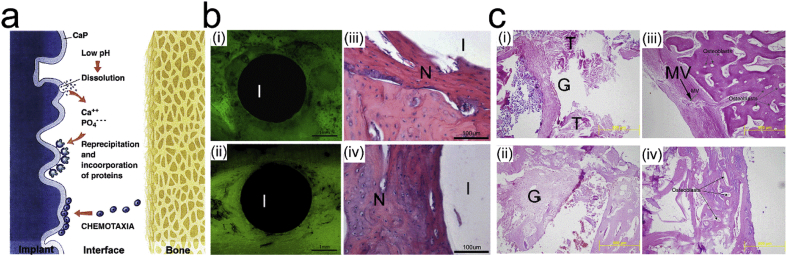

Biocompatibility is an essential and required ability of the biomedical materials to be applied in human body with an appropriate or even beneficial interaction with the surrounding tissues. Specifically, the osteointegration is the biocompatibility for bone application to induce integration and interaction between the implants and surrounding bone tissues [107]. It has generally been accepted that CaP-based ceramics could be able to induce fast biological bonding and thus good clinical performance through the superior osseointegration rate in the initial stage [20,108]. Schematically, the in vivo interaction of orthopedic implants is shown in Fig. 2a [20,108]. The implantation process normally induces a local pH decrease and thus initiate corrosion or dissolution of the metallic substrate and surface coating. The released metallic ions and Ca2+ and PO43− could interact with the surrounding cells and tissues and also possible to reprecipitate in the forms of apatite or composites with collagen. For example, the CaPs could also affect the cell behaviors of osteoblast and osteoclast in the bone formation process [109]. The chemical composition, solubility, and surface topography play significant roles in the above processes [110,111]. CaPs incorporated with some elements (e.g. strontium, silicon) could further enhance the osteoblast activities while inhibiting the osteoclast differentiation [112,113].

Fig. 2.

Enhanced osteointegration of metallic implant materials by CaP coating. (a) Schematic representation of osseointegration induced by CaP coating [108]. (b) (i, ii) Fluoroscopic images and (iii, iv) HE stained pathological images of the cross-section of (i, iii) uncoated and (ii, iv) DCPD coated Mg implant after 4 weeks of implantation. (I: implant; N: newly formed osteoid tissue) (c) HE-stained pathological images of the Ti6A14V screw implant/bone interfaces: (i) uncoated, (ii) micron-HA-coated, (iii) nano-HA-coated, and (iv) polymeric bioabsorbable screw as control. (G: granulation tissue; T: tendons; MV: minimal vascularization). ((a) is reproduced with permission from Ref. [115] (b) is reproduced with permission from Ref. [144].).

Because of the different characteristics as shown in Table 1, CaP coatings with various Ca/P ratios have different in vitro and in vivo performances. Table 3 summarized the in vitro cytocompatibility and in vivo bone regeneration of different CaP coatings on typical metallic implants using various coating methods as discussed above. It is noteworthy that MCPM and TTCP are not suitable to be applied as coating materials on metallic implants. DCPD coating has shown a good biocompatibility in a short implantation period (4–6 weeks) [[115], [116], [117], [118]]. When compared to the OCP, TCP and ACP, different apatite coatings showed superior stability and compatibility and thus were used more widely. Especially, the fluorine incorporation could help to stabilize the apatite structure [114], while the carbonated apatite has a closer chemical composition to the apatite in bone tissue and thus owns an inherent osteoconductivity [142,143].

Table 3.

In vitro and in vivo studies of CaP coatings on metallic implants for osteointegration.

| CaPs | Substrates | Techniques | In vitro and in vivo performances | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCPD | Mg–1.2Mn–1Zn alloy | Chemical conversion | Fibroblast cells: improved cell adhesion, growth, and proliferation; femoral shaft of rabbits: significantly enhanced osteoconductivity and osteogenesis (4 weeks). | [115] |

| Ti–6Al–4V | Electro-deposition | Human fetal osteoblasts cells: supported the osteogenic function and the expression of extracellular matrix. | [116] | |

| Pure Ti | Plasma spray | Distal femur of rabbits: improved in vivo stability and early stage bone formation (6 weeks). | [117] | |

| Porous Ti | Plasma spray | Femur and tibia of sheep: improved cancellous bone ingrowth in the early stage (4 weeks) but decreased mechanical stability (12 weeks). | [118] | |

| OCP | Ti–6Al–4V | Biomimetic | Mouse bone-marrow cell: cell-mediated degradation in osteoclast-enriched cell cultures. | [119] |

| pure Ti | Electro-deposition |

Human osteosarcoma-derived osteoblast-like cells: improved cell attachment and coverage; Femur of rabbits: osteoconductive and improved the bone growth (6 weeks). |

[120] | |

| α-TCP | Pure Ti | Magnetron sputtering | Femur of rabbits: increased bone-implant contact and peri-implant bone volume with increasing coating dissolution: α-TCP > TTCP > HA (6 weeks). | [121] |

| Ti–6Al–4V | Plasma spray | Femur of dogs: similar bone response to TTCP and HA coatings, with a small increase in bone contact and remodeling lacunae after 5 months implantation. | [122] | |

| β-TCP | pure Ti | Electrospray | Subcutaneous implantation in goats: gradual degradation (12 weeks); | [123] |

| α+β-TCP | Ti–6Al–4V | PLD | Rat bone marrow cells: bone matrix formation on remaining porous β-TCP coating with osteoclastic cellular resorption in the potentially osteogenic cell culture. | [124] |

| TCP + HA | Ti alloy | Plasma spray | Human total hip arthroplasty: reduced femoral bone loss after 2 years of implantation. | [125] |

| ACP | Ti–6Al–4V | Biomimetic | Mouse bone-marrow cells: no cell-mediated degradation in osteoclast-enriched cell cultures. | [119] |

| Ti–6Al–4V | PLD | Rat bone marrow cells: bone matrix delaminated in the potentially osteogenic primary cell culture. | [124] | |

| pure Ti | Electrospray | Subcutaneous implantation in goats: gradual degradation (12 weeks). | [123] | |

| CDHA | Ti–6Al–4V scaffolds | Electro-deposition | Human periosteum-derived cells: showed spreading and interactions on the stable coating, with an inverted relationship between the cell viability and the current density applied for coating deposition. | [126] |

| Mg–2.0Zn–0.2Ca | Electro-deposition | Femur of rabbits: coating is valid for 8 weeks and could accelerate the new bone formation and transformation 24 weeks postoperatively. | [127] | |

| HA + OCP | Mg–2.0Zn–0.2Ca | Electro-deposition | Femur of rabbits: induced more new bone formation and faster bone response (18 weeks). | [128] |

| HA | Pure Ti | Plasma spray | Adult human gingiva fibroblasts: lower crystallinity helps cell attachment, while higher medium pH inhibits cell proliferation. | [129] |

| Pure Ti | Magnetron sputtering | Rat femora bone marrow cells: crystalline coatings stimulate cell proliferation and differentiation, while the amorphous coatings showed adverse and negative effects. | [130] | |

| Ti–6Al–4V | PLD | Rat bone marrow cells: osteoconductive and strong bone bonding without osteoclastic cellular resorption in the potentially osteogenic cell culture. | [124] | |

| Pure Ti | Magnetron sputtering | Femur of osteoporotic rats: enhanced bone/implant interface in both osteoporotic and normal conditions (12 weeks). | [131] | |

| Pure Ti | Biomimetic | Femur of rabbits: significantly higher bone-to-implant contact and promoted new bone formation (4 weeks). | [132] | |

| Ti–6Al–4V | Electro-deposition | Canine trabecular bone: induced the mineralized tissue apposition ratio and microstructure, with better mechanical integration (14 days). | [133] | |

| Ti–6Al–4V | Plasma spray | Canine trabecular bone: accelerate early stage (7 days) mineralization of bone tissue formation. | [133] | |

| Ti–13Nb–11Zr | Biomimetic | Rabbit cortical bone: significantly higher bone mineralization index than that of HA-coated Ti6Al4V surface (12 weeks). | [134] | |

| Stainless steel | ASTM F1185 commercial | Wrist of patients: showed not obviously superior clinical performance and not recommended for the external fixation for unstable wrist fractures (5 weeks). | [135] | |

| fluoridated HA (FHA) | Mg–6Zn alloy | Electro-deposition |

Human bone marrow stromal cells: enhanced cellular proliferation and differentiation. Femur of rabbits: better interface contacts with slow degradation (1 month). |

[114] [136] |

| AZ91 | Electro-deposition | Greater trochanter of rabbits: increased new bone formation and decreased inflammation around the implant (2 months). | [137] | |

| Pure Ti | Electro-deposition | MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cell line: improved biological affinity including cell proliferation and alkaline phosphatase activity; higher bonding strength and lower dissolution rate than HA coating. | [138] | |

| Ti–6Al–4V | Sol-gel | Osteoblast-like cells of rabbits: increasing percentage of cells in S period but slightly decreasing cell proliferation rate when increasing F content in the FHA coatings. | [139,140] | |

| Ti–6Al–4V | Plasma spray | Jaws of Dogs: good bone integration and much slower degradation than HA coating (12 months). | [141] | |

| carbonated apatite (CA) | Ti–6Al–4V | Biomimetic | Bone marrow stromal cells of goats: polygonal shape with extending cytoplasmic processes, and better cell attachment than OCP coating and electro-deposited CA coating. | [142] |

| Ti–6Al–4V | Biomimetic | Mouse bone-marrow cell: cell-mediated degradation with numerous resorption lacunae in osteoclast-enriched cell cultures. | [119] | |

| Ti–6Al–4V | Biomimetic | Subcutaneous implantation in rats: calcified after 1 week of implantation. | [143] | |

| Pure Ti | Electrospray | Subcutaneous implantation in goats: gradual degradation (12 weeks). | [123] | |

| Pure Ti scaffolds | Electro-deposition | Dorsal subcutaneous pouches of rats: a mineralized collagen tissue formation around the implants, without new bone formation (4 weeks). | [73] |

Fig. 2 b-c show the implant/bone interfaces for DCPD-coated Mg implants and HA-coated Ti alloy (Ti–6Al–4V) implants, respectively, as compared to the uncoated implants [115,144]. The in vivo implantation test exhibited that bone contact and newly formed osteoid tissue content were significantly higher for CaP-coated implants, indicating that both CaP coatings enhance the bone integration ability. Also, the nano-scale HA coating was shown to promote the formation of minimal vascular granulation tissue around the Ti alloy implants (Fig. 2c) [144].

Inspired by the composition of organic matrix and inorganic CaP (carbonated HA) of bone tissue, the biomolecules–CaP composite coatings have been developed for bone replace or repair applications [23]. It has been indicated that the composite coatings could provide superior mechanical, adhesion and other biological properties. For example, the weak toughness of CaPs could be improved when composited with collagen and other polymer components [145], while the coating adhesion could also be enhanced due to the higher coating toughness on the metallic material surface [146]. The CaP coatings containing growth factors (e.g. bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)) could significantly promote the new bone formation surrounding the coated implants [147,148].

4.2. Corrosion and biodegradation control

A higher corrosion resistance has been pursued for a long period for traditional inert metals [149]. The passive oxide layer on Ti alloys, stainless steels, and cobalt-chrome alloys could provide the superior corrosion resistance than other alloys. Therefore, these alloys have been developed rapidly and commercialized as permanent implant materials applied in many clinic applications. Nevertheless, the chloride ion in physiological environment and the pH variation surrounding the implants could still accelerate the in vivo corrosion of these inert implants. This would deteriorate the mechanical properties and produce harmful metal ions [150]. Therefore, it is still necessary to further enhance the corrosion resistance and decrease the harmful effects of the corrosion products of the permanent implant materials. Plenty of methods have been applied to inhibit or control the corrosion behavior, including alloying, deformation and heat treatments, surface coatings and other modifications [151]. Thus, CaP and its composite coatings could also be applied on the permanent implant materials to increase the corrosion resistance [152].

Biodegradable metals proposed in recent years for temporary implants application are different with the permanent implant materials, and suitable degradation rate and biocompatible degradation products are critical criteria for their clinical applications. Fe materials degrade too slow as temporary implant materials because of the generation of a firm degradation product layer, which is potentially retained in the encapsulating neointima and thus deteriorates the tissue integration and normal arterial function [153,154]. However, the porous structure of bone scaffolds should be another story when talking about the degradation rate. The high surface area would accelerate the in vivo degradation when an appropriate porosity was applied. In addition to the porous structure design, the surface modification is preferred with superior controllability to modulate the degradation rate [155,156]. Moreover, the CaP coating could possibly change the degradation mechanism to reduce the harmful iron phosphate-based components [155,156].

It has been shown in several animal models that the degradation rate of Zn and its alloys is promising to accommodate the clinical requirements [157,158]. One of the concerns is that the released Zn ion is found to be potentially excessive from pure Zn and thus lead to low cytocompatibility of pre-osteoblasts and endothelial cells [159]. Surface coating with CaP could be one of the effective ways to control the Zn ion release and possibly convert the excessive Zn ion to corrosion products with higher cytocompatibility.

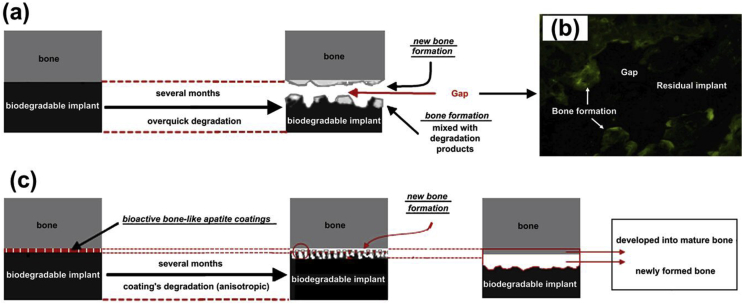

Mg materials possess relatively harmless degradation products, but the too rapid degradation of Mg can affect cell behaviors and functions through high pH and hydrogen gas release [160]. CaP and its composite coatings have been developed on Mg and its alloys for dozens of years with simultaneously improved degradation resistance and surface biofunctions [115,161,162]. A suitable in vivo degradation rate is significant and could help the tissue integration and new bone formation, as indicated by Fig. 3 [114,163,164]. The uniform and well-adhesive CaP coatings greatly reduced degradation rates of the Mg-based implants, especially in the first three months (Fig. 3c), which is the initial stage when the slowly formed bone requires the mechanical support from the complete implants. Therefore, the bone-like apatite coatings can eliminate the interfacial gap between the implant and the new-formed bone (Fig. 3b) through the biodegradation controlling and the osteointegration abilities.

Fig. 3.

Schematic of the biodegradation control performance provided by the CaP coatings. (a) Extremely high degradation rate of the Mg-alloy implant in body fluid may possibly result in a gap between the implant and the new-formed bone. (b) The gap is shown by a typical tetracycline labeling 14 weeks post-operation in the femora of rabbits. (c) The CaP coatings can reduce the degradation rate to eliminate the interfacial gap and enhance the biocompatibility of the implants. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [114].

4.3. Antibacterial property

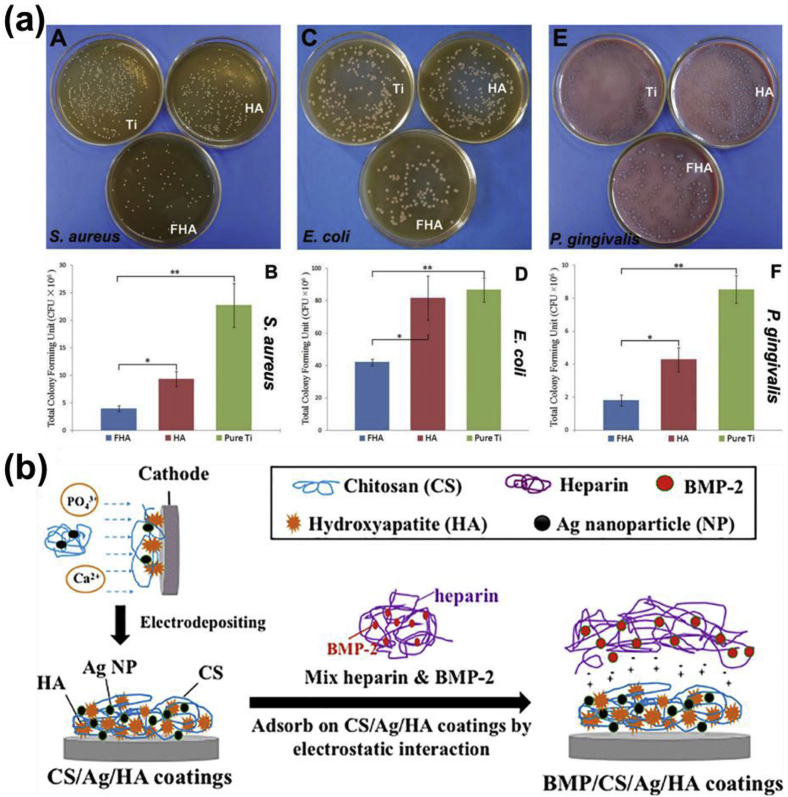

There is a high risk of bacterial contamination and biofilm formation on the implants surface in the initial stage of implantation, which might cause the persistent infection and surgery failure [165]. The traditional method using the local delivery of bactericidal agents would possibly cause the antibiotic resistance and affects the normal tissue growth [166]. It is preferred to produce surface coatings with the biocompatibility and the antibacterial property simultaneously. Although CaP coatings are normally regarded as a carrier for biological molecules to realize the antibacterial and other therapeutic functions [167], some CaP coatings own an inherent antibacterial property due to the unique topography, roughness, and chemical compositions [[168], [169], [170]]. For example, HA coatings have been found to own antibacterial potential on the Ti surface, and fluoridated HA (FHA) coating possessed a significantly higher antibacterial property than the pure HA coating (Fig. 4a) [168]. It could be seen that the pure HA coating could reduce the growth of Staphylococcus aureus and Porphyromonas gingivalis compared to the Ti surface, while the fluorine incorporation in the HA coating further enhanced the antibacterial performance when cultured all the three bacteria. In addition to fluorine, silver, copper, and Zn are also well-known for their antibacterial performance and have been incorporated in the CaP phase to obtain antibacterial CaP coatings [156,169,170].

Fig. 4.

Antibacterial performance of CaP and its composite coating on metallic implant materials. (a) Images and statistics of colony formation units of three kinds of different bacteria after cultured with uncoated, FHA, and HA coated pure Ti surfaces. (b) Schematic of the electrochemical deposition process and immobilization of BMP-2 on HA coatings. ((a) is reproduced with permission from Ref. [168] (b) is reproduced with permission from Ref. [173].).

The CaP coating with porous structures could act as the carrier for antimicrobial biomolecules with good biocompatibility. Antimicrobial peptide (AMP) is one of the qualified biomolecules and has been composited with CaP coatings on Ti surface to ensure the antibacterial property without endangering the surface bioactivity [171]. When acting as the carrier for biomolecules or nanoparticles, the single-layered CaP coating could not ensure the sustained and long-term release of these antibacterial agents. A secondary layer of other protective polymers, such as polydopamine [172] and chitosan [173], has been applied together with a single layer coating to overcome the above problem (Fig. 4b). It has been found that the multilayered composite coatings had a good carrier capacity for the Ag nanoparticles and could also provide a sustained nanoparticle releasing profile, which avoided the nanoparticles agglomeration in the coating process and their burst release [173]. In this composite coating system, a bone growth factor was also incorporated to enhance the bone osseointegration [173]. Therefore, the CaP-based composite coating could also be applied as a carrier for other biofunctional agents in addition to the antibacterial molecules or particles [167,174].

5. Conclusion

Surface functionalization of metallic implants with CaP coatings has been extensively explored in the last decades due to their high-performance on specific functionalities for orthopedic and dental applications. In this review, we focus on the most critical biofunctions benefited from CaP coatings on implantable metallic materials. In summary, the efforts on CaP coated metallic implants have resulted in significant progress in vitro and in vivo, while their clinical application still has a long way to go. Novel coating methods should be explored to combine the benefits and overcome the drawbacks of current technology, especially in terms of controlling the coating structures and degradation rate in gentle coating conditions. These are critical parameters for its biological performance. In addition, the multilayer composite coating system is a future trend to provide multifunction for biomedical implants.

Author contributions

Su Y summarized the relevant literature and prepared the manuscript. Cockerill I participated in the discussion on the literature about recent in vitro and in vivo research. Zheng Y, Tang L, and Qin Y provided many meaningful recommendations. Zhu D advised the original idea, supervised the project, and revised the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health [Grant number R01HL140562]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

References

- 1.Crubezy E. False teeth of the Roman world. Nature. 1998;6662(391):29. doi: 10.1038/34067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park J.B., Lakes R.S., editors. Biomaterials. Springer New York; New York, NY: 2007. Metallic implant materials; pp. 99–137. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niinomi M. Development of new metallic alloys for biomedical applications. Acta Biomater. 2012;11(8):3888–3903. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng Y.F. 2014. Biodegradable Metals, Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports77; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su Y. Zinc-based biomaterials for regeneration and therapy. Trends Biotechnol. 2019;37(4):428–441. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu D. Biological responses and mechanisms of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells to Zn and Mg biomaterials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;33(9):27453–27461. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b06654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J. Long-term clinical study and multiscale analysis of in vivo biodegradation mechanism of Mg alloy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am. 2016;3(113):716–721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518238113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu D. Mechanical strength, biodegradation, and in vitro and in vivo biocompatibility of Zn biomaterials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11(7):6809–6819. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b20634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X. Topological design and additive manufacturing of porous metals for bone scaffolds and orthopaedic implants: a review. Biomaterials. 2016;83:127–141. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nel A.E. Understanding biophysicochemical interactions at the nano-bio interface. Nat. Mater. 2009;7(8):543–557. doi: 10.1038/nmat2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Planell J.A. Advances in Regenerative Medicine: Role of Nanotechnology, and Engineering Principles. Springer; 2010. Materials surface effects on biological interactions; pp. 233–252. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teixeira A.I. Epithelial contact guidance on well-defined micro- and nanostructured substrates. J. Cell Sci. 2003;10(116):1881–1892. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu J. Mechanical regulation of cell function with geometrically modulated elastomeric substrates. Nat. Methods. 2010;9(7):733–736. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Y. Biophysical regulation of cell behavior—cross talk between substrate stiffness and nanotopography. Engineering-Prc. 2017;1(3):36–54. doi: 10.1016/J.ENG.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meng J. Cell adhesive spectra along surface wettability gradient from superhydrophilicity to superhydrophobicity. Sci. China Chem. 2017;5(60):614–620. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su Y. Bioinspired surface functionalization of metallic biomaterials. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. 2018;77:90–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2017.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu G. Engineering and functionalization of biomaterials via surface modification. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2015;10(3):2024–2042. doi: 10.1039/c4tb01934b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su Y. Interfacial zinc phosphate is the key controlling biocompatibility of metallic zinc implants. Adv. Sci. 2019 doi: 10.1002/advs.201900112. (Accepted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su Y. Enhanced cytocompatibility and antibacterial property of zinc phosphate coating on biodegradable zinc materials. Acta Biomater. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.03.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Surmenev R.A. Significance of calcium phosphate coatings for the enhancement of new bone osteogenesis – a review. Acta Biomater. 2014;2(10):557–579. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu X., Leng Y. Comparison of the osteoblast and myoblast behavior on hydroxyapatite microgrooves. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2009;1(90):438–445. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J. Surface modification of magnesium alloys developed for bioabsorbable orthopedic implants: a general review. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2012;6(100B):1691–1701. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.32707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LeGeros R.Z. 1990. Calcium Phosphates in Oral Biology and Medicine, Monographs in Oral Science15) pp. 1–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anselme K. Osteoblast adhesion on biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2000;7(21):667–681. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dorozhkin S.V. Calcium orthophosphate coatings on magnesium and its biodegradable alloys. Acta Biomater. 2014;7(10):2919–2934. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shadanbaz S., Dias G.J. Calcium phosphate coatings on magnesium alloys for biomedical applications: a review. Acta Biomater. 2012;1(8):20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paital S.R., Dahotre N.B. Calcium phosphate coatings for bio-implant applications: materials, performance factors, and methodologies. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2009;1–3(66):1–70. [Google Scholar]

- 28.YANG Y. A review on calcium phosphate coatings produced using a sputtering process?an alternative to plasma spraying. Biomaterials. 2005;3(26):327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliveira A.L. Nature-inspired calcium phosphate coatings: present status and novel advances in the science of mimicry. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2003;4–5(7):309–318. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dorozhkin S.V., Epple M. Biological and medical significance of calcium phosphates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;17(41):3130–3146. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020902)41:17<3130::AID-ANIE3130>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carrodeguas R.G., De Aza S. α-Tricalcium phosphate: synthesis, properties and biomedical applications. Acta Biomater. 2011;10(7):3536–3546. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morimoto S. Comparative study on in vitro biocompatibility of synthetic octacalcium phosphate and calcium phosphate ceramics used clinically. Biomed. Mater. 2012;4(7):45020. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/7/4/045020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walschus U. Morphometric immunohistochemical examination of the inflammatory tissue reaction after implantation of calcium phosphate-coated titanium plates in rats. Acta Biomater. 2009;2(5):776–784. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paul K. In vivo evaluation of injectable calcium phosphate cement composed of Zn‐and Si‐incorporated β‐tricalcium phosphate and monocalcium phosphate monohydrate for a critical sized defect of the rabbit femoral condyle. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2017;2(105):260–271. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia Z. In vitro biodegradation of three brushite calcium phosphate cements by a macrophage cell-line. Biomaterials. 2006;26(27):4557–4565. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li X. Coating electrospun poly (ε-caprolactone) fibers with gelatin and calcium phosphate and their use as biomimetic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Langmuir. 2008;24(24):14145–14150. doi: 10.1021/la802984a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klammert U. Cytocompatibility of brushite and monetite cell culture scaffolds made by three-dimensional powder printing. Acta Biomater. 2009;2(5):727–734. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alge D.L. In vitro degradation and cytocompatibility of dicalcium phosphate dihydrate cements prepared using the monocalcium phosphate monohydrate/hydroxyapatite system reveals rapid conversion to HA as a key mechanism. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2012;3(100B):595–602. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamimi F. The effect of autoclaving on the physical and biological properties of dicalcium phosphate dihydrate bioceramics: brushite vs. monetite. Acta Biomater. 2012;8(8):3161–3169. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wen C. The use of brushite calcium phosphate cement for enhancement of bone-tendon integration in an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rabbit model. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2009;2(89):466–474. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuemmerle J.M. Assessment of the suitability of a new brushite calcium phosphate cement for cranioplasty – an experimental study in sheep. J. Cranio Maxill Surg. 2005;1(33):37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Theiss F. Biocompatibility and resorption of a brushite calcium phosphate cement. Biomaterials. 2005;21(26):4383–4394. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ji C., Ahn J. Clinical experience of the brushite calcium phosphate cement for the repair and augmentation of surgically induced cranial defects following the pterional craniotomy. J. Korean Neurosurg. S. 2010;3(47):180–184. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2010.47.3.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suwanprateeb J. Low temperature preparation of calcium phosphate structure via phosphorization of 3D-printed calcium sulfate hemihydrate based material. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2010;2(21):419–429. doi: 10.1007/s10856-009-3883-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khairoun I. In vitro characterization and in vivo properties of a carbonated apatite bone cement. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2002;4(60):633–642. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tamimi F. Resorption of monetite granules in alveolar bone defects in human patients. Biomaterials. 2010;10(31):2762–2769. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mihailescu I.N. Calcium phosphate thin films synthesized by pulsed laser deposition: physico-chemical characterization and in vitro cell response. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2005;1–4(248):344–348. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Y. Influence of calcium phosphate crystal assemblies on the proliferation and osteogenic gene expression of rat bone marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2007;7(28):1393–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bigi A. Human osteoblast response to pulsed laser deposited calcium phosphate coatings. Biomaterials. 2005;15(26):2381–2389. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kamakura S. Octacalcium phosphate combined with collagen orthotopically enhances bone regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2006;2(79):210–217. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kamakura S. The primacy of octacalcium phosphate collagen composites in bone regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2007;3(83):725–733. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Honda Y. The effect of microstructure of octacalcium phosphate on the bone regenerative property. Tissue Eng. 2009;8(15):1965–1973. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miyatake N. Effect of partial hydrolysis of octacalcium phosphate on its osteoconductive characteristics. Biomaterials. 2009;6(30):1005–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ehara A. Effects of α-TCP and TetCP on MC3T3-E1 proliferation, differentiation and mineralization. Biomaterials. 2003;5(24):831–836. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00411-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mayr-Wohlfart U. Proliferation and differentiation rates of a human osteoblast-like cell line (SaOS-2) in contact with different bone substitute materials. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001;1(57):132–139. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200110)57:1<132::aid-jbm1152>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Herten M. Surface- and nonsurface-dependent in vitro effects of bone substitutes on cell viability. Clin. Oral Investig. 2009;2(13):149–155. doi: 10.1007/s00784-008-0214-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wiltfang J. Degradation characteristics of alpha and beta tri-calcium-phosphate (TCP) in minipigs. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2002;2(63):115–121. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kihara H. Biodegradation process of α‐TCP particles and new bone formation in a rabbit cranial defect model. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2006;2(79):284–291. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamada M. Histological and histomorphometrical comparative study of the degradation and osteoconductive characteristics of α‐and β‐tricalcium phosphate in block grafts. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2007;1(82):139–148. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cai S. Fabrication and biological characteristics of beta-tricalcium phosphate porous ceramic scaffolds reinforced with calcium phosphate glass. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2009;1(20):351–358. doi: 10.1007/s10856-008-3591-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sous M. Cellular biocompatibility and resistance to compression of macroporous beta-tricalcium phosphate ceramics. Biomaterials. 1998;23(19):2147–2153. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu H. β-tricalcium phosphate nanoparticles adhered carbon nanofibrous membrane for human osteoblasts cell culture. Mater. Lett. 2010;6(64):725–728. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen Y. Enhanced effect of β-tricalcium phosphate phase on neovascularization of porous calcium phosphate ceramics: in vitro and in vivo evidence. Acta Biomater. 2015;11:435–448. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shirasu N. Bone formation in a rat calvarial defect model after transplanting autogenous bone marrow with beta-tricalcium phosphate. Acta Histochem. 2010;3(112):270–277. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu G. Repair of goat tibial defects with bone marrow stromal cells and β-tricalcium phosphate. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008;6(19):2367–2376. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bi L. Reconstruction of goat tibial defects using an injectable tricalcium phosphate/chitosan in combination with autologous platelet-rich plasma. Biomaterials. 2010;12(31):3201–3211. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou H., Bhaduri S. Novel microwave synthesis of amorphous calcium phosphate nanospheres. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2012;4(100):1142–1150. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.32681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ma X. In vitro and in vivo degradation of poly(D, L-lactide-co-glycolide)/amorphous calcium phosphate copolymer coated on metal stents. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2011;4(96):632. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.33016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guo H. Biocompatibility and osteogenicity of degradable Ca-deficient hydroxyapatite scaffolds from calcium phosphate cement for bone tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2009;1(5):268–278. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kasten P. Comparison of human bone marrow stromal cells seeded on calcium-deficient hydroxyapatite, β-tricalcium phosphate and demineralized bone matrix. Biomaterials. 2003;15(24):2593–2603. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kasten P. Ectopic bone formation associated with mesenchymal stem cells in a resorbable calcium deficient hydroxyapatite carrier. Biomaterials. 2005;29(26):5879–5889. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vaquette C. Effect of culture conditions and calcium phosphate coating on ectopic bone formation. Biomaterials. 2013;22(34):5538–5551. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lopez-Heredia M.A. Rapid prototyped porous titanium coated with calcium phosphate as a scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;17(29):2608–2615. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sandeman S.R. The in vitro corneal biocompatibility of hydroxyapatite coated carbon mesh. Biomaterials. 2009;18(30):3143–3149. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chu T.M.G. Mechanical and in vivo performance of hydroxyapatite implants with controlled architectures. Biomaterials. 2002;5(23):1283–1293. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Patel N. A comparative study on the in vivo behavior of hydroxyapatite and silicon substituted hydroxyapatite granules. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2002;12(13):1199–1206. doi: 10.1023/a:1021114710076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yuan H. A preliminary study on osteoinduction of two kinds of calcium phosphate ceramics. Biomaterials. 1999;19(20):1799–1806. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Porter A.E. Comparison of in vivo dissolution processes in hydroxyapatite and silicon-substituted hydroxyapatite bioceramics. Biomaterials. 2003;25(24):4609–4620. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00355-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wenisch S. In vivo mechanisms of hydroxyapatite ceramic degradation by osteoclasts: fine structural microscopy. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2003;3(67A):713–718. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van Blitterswijk C.A. The biocompatibility of hydroxyapatite ceramic: a study of retrieved human middle ear implants. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1990;4(24):433–453. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820240403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Doi Y. Osteoclastic responses to various calcium phosphates in cell cultures. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 1999;3(47):424–433. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19991205)47:3<424::aid-jbm19>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yoshimine Y. In vitro interaction between tetracalcium phosphate-based cement and calvarial osteogenic cells. Biomaterials. 1996;23(17):2241–2245. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)00045-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tsai C. Bioresorption behavior of tetracalcium phosphate-derived calcium phosphate cement implanted in femur of rabbits. Biomaterials. 2008;8(29):984–993. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yoshimine Y. Biocompatibility of tetracalcium phosphate cement when used as a bone substitute. Biomaterials. 1993;6(14):403–406. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(93)90141-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Eliaz N., Metoki N. Calcium phosphate bioceramics: a review of their history, structure, properties, coating technologies and biomedical applications. Materials. 2017;4(10):334. doi: 10.3390/ma10040334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cancedda R. A tissue engineering approach to bone repair in large animal models and in clinical practice. Biomaterials. 2007;29(28):4240–4250. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hannink G., Arts J.J.C. 2011. Bioresorbability, porosity and mechanical strength of bone substitutes: what is optimal for bone regeneration? Injury42) pp. S22–S25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Samavedi S. Calcium phosphate ceramics in bone tissue engineering: a review of properties and their influence on cell behavior. Acta Biomater. 2013;9(9):8037–8045. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Suchanek W., Yoshimura M. Processing and properties of hydroxyapatite-based biomaterials for use as hard tissue replacement implants. J. Mater. Res. 1998;1(13):94–117. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Narayanan R. Calcium phosphate-based coatings on titanium and its alloys. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2008;1(85B):279–299. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yang Y. Effect of post-deposition heating temperature and the presence of water vapor during heat treatment on crystallinity of calcium phosphate coatings. Biomaterials. 2003;28(24):5131–5137. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li P. Bonelike hydroxyapatite induction by a gel‐derived titania on a titanium substrate. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1994;5(77):1307–1312. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Asri R.I.M. A review of hydroxyapatite-based coating techniques: sol–gel and electrochemical depositions on biocompatible metals. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. 2016;57:95–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hench L.L. Sol-gel materials for bioceramic applications. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 1997;5(2):604–610. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Su Y. Improving the degradation resistance and surface biomineralization ability of calcium phosphate coatings on a biodegradable magnesium alloy via a sol-gel spin coating method. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018;3(165):C155–C161. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Royer P., Rey C. Calcium phosphate coatings for orthopaedic prosthesis. Surf. Coating. Technol. 1991;1–3(45):171–177. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Song Y.W. Electrodeposition of hydroxyapatite coating on AZ91D magnesium alloy for biomaterial application. Mater. Lett. 2008;17–18(62):3276–3279. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Su Y. Preparation and corrosion behavior of calcium phosphate and hydroxyapatite conversion coatings on AM60 magnesium alloy. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013;11(160):C536–C541. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Su Y. Composite microstructure and formation mechanism of calcium phosphate conversion coating on magnesium alloy. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016;9(163):G138–G143. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chen X.B. A simple route towards a hydroxyapatite–Mg(OH)2 conversion coating for magnesium. Corros. Sci. 2011;6(53):2263–2268. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Song Y. Formation mechanism of phosphate conversion film on Mg–8.8Li alloy. Corros. Sci. 2009;1(51):62–69. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Su Y. A chemical conversion hydroxyapatite coating on AZ60 magnesium alloy and its electrochemical corrosion behaviour. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2012;11(7):11497–11511. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Su Y. Improvement of the biodegradation property and biomineralization ability of magnesium–hydroxyapatite composites with dicalcium phosphate dihydrate and hydroxyapatite coatings. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016;5(2):818–828. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Harun W. A comprehensive review of hydroxyapatite-based coatings adhesion on metallic biomaterials. Ceram. Int. 2018;2(44):1250–1268. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Johnson A.J.W., Herschler B.A. A review of the mechanical behavior of CaP and CaP/polymer composites for applications in bone replacement and repair. Acta Biomater. 2011;1(7):16–30. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhou H. Fabrication aspects of PLA-CaP/PLGA-CaP composites for orthopedic applications: a review. Acta Biomater. 2012;6(8):1999–2016. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hallab N.J., Jacobs J.J. Orthopedic applications. In: Hoffman A.S., Schoen F.J., Lemons J.E., editors. Biomaterials Science: an Introduction to Materials in Medicine. third ed. Academic Press; 2013. pp. 841–882. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cunningham B.W. Bioactive titanium calcium phosphate coating for disc arthroplasty: analysis of 58 vertebral end plates after 6- to 12-month implantation. Spine J. 2009;10(9):836–845. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chai Y.C. Mechanisms of ectopic bone formation by human osteoprogenitor cells on CaP biomaterial carriers. Biomaterials. 2012;11(33):3127–3142. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yamada S. Osteoclastic resorption of calcium phosphate ceramics with different hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate ratios. Biomaterials. 1997;15(18):1037–1041. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Costa D.O. The differential regulation of osteoblast and osteoclast activity by surface topography of hydroxyapatite coatings. Biomaterials. 2013;30(34):7215–7226. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chung C., Long H. Systematic strontium substitution in hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium via micro-arc treatment and their osteoblast/osteoclast responses. Acta Biomater. 2011;11(7):4081–4087. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pietak A.M. Silicon substitution in the calcium phosphate bioceramics. Biomaterials. 2007;28(28):4023–4032. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Li J. In vitro responses of human bone marrow stromal cells to a fluoridated hydroxyapatite coated biodegradable Mg–Zn alloy. Biomaterials. 2010;22(31):5782–5788. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Xu L. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the surface bioactivity of a calcium phosphate coated magnesium alloy. Biomaterials. 2009;8(30):1512–1523. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ince A. In vitro investigation of orthopedic titanium-coated and brushite-coated surfaces using human osteoblasts in the presence of gentamycin. J. Arthroplast. 2008;5(23):762–771. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Simank H. The influence of surface coatings of dicalcium phosphate (DCPD) and growth and differentiation factor-5 (GDF-5) on the stability of titanium implants in vivo. Biomaterials. 2006;21(27):3988–3994. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chen D. Osseointegration of porous titanium implants with and without electrochemically deposited DCPD coating in an ovine model. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2011;1(6):1. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-6-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Leeuwenburgh S. Osteoclastic resorption of biomimetic calcium phosphate coatings in vitro. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001;2(56):208–215. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200108)56:2<208::aid-jbm1085>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kazemzadeh Narbat M. Drug release and bone growth studies of antimicrobial peptide‐loaded calcium phosphate coating on titanium. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2012;5(100):1344–1352. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.32701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Urquia Edreira E.R. Effects of calcium phosphate composition in sputter coatings on in vitro and in vivo performance. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2015;1(103):300–310. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Klein C.P. Long-term in vivo study of plasma-sprayed coatings on titanium alloys of tetracalcium phosphate, hydroxyapatite and alpha-tricalcium phosphate. Biomaterials. 1994;2(15):146–150. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(94)90264-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Leeuwenburgh S.C.G. In vitro and in vivo reactivity of porous, electrosprayed calcium phosphate coatings. Biomaterials. 2006;18(27):3368–3378. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Clèries L. Bone growth on and resorption of calcium phosphate coatings obtained by pulsed laser deposition. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000;1(49):43–52. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200001)49:1<43::aid-jbm6>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Tanzer M. Femoral remodeling after porous-coated total hip arthroplasty with and without hydroxyapatite-tricalcium phosphate coating: a prospective randomized trial. J. Arthroplast. 2001;5(16):552–558. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.23721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Chai Y.C. Perfusion electrodeposition of calcium phosphate on additive manufactured titanium scaffolds for bone engineering. Acta Biomater. 2011;5(7):2310–2319. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wang H. In vivo degradation behavior of Ca-deficient hydroxyapatite coated Mg–Zn–Ca alloy for bone implant application. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 2011;1(88):254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Chen S. In vivo degradation and bone response of a composite coating on Mg–Zn–Ca alloy prepared by microarc oxidation and electrochemical deposition. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2012;2(100B):533–543. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Chou L. Effects of hydroxylapatite coating crystallinity on biosolubility, cell attachment efficiency and proliferation in vitro. Biomaterials. 1999;10(20):977–985. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.ter Brugge P.J. Effect of calcium phosphate coating crystallinity and implant surface roughness on differentiation of rat bone marrow cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2002;1(60):70–78. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Alghamdi H.S. Osteogenicity of titanium implants coated with calcium phosphate or collagen type-I in osteoporotic rats. Biomaterials. 2013;15(34):3747–3757. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Jimbo R. Histological and three-dimensional evaluation of osseointegration to nanostructured calcium phosphate-coated implants. Acta Biomater. 2011;12(7):4229–4234. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Wang H. Early bone apposition in vivo on plasma-sprayed and electrochemically deposited hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium alloy. Biomaterials. 2006;23(27):4192–4203. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Bigi A. The response of bone to nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite-coated Ti13Nb11Zr alloy in an animal model. Biomaterials. 2008;11(29):1730–1736. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Pieske O. Clinical benefit of hydroxyapatite-coated pins compared with stainless steel pins in external fixation at the wrist: a randomised prospective study. Injury. 2010;10(41):1031–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Li J. The in vitro indirect cytotoxicity test and in vivo interface bioactivity evaluation of biodegradable FHA coated Mg–Zn alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng., B. 2011;20(176):1785–1788. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Razavi M. In vivo assessments of bioabsorbable AZ91 magnesium implants coated with nanostructured fluoridated hydroxyapatite by MAO/EPD technique for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015;C48:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Wang J. Fluoridated hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium obtained by electrochemical deposition. Acta Biomater. 2009;5(5):1798–1807. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.CHENG K. In vitro behavior of osteoblast-like cells on fluoridated hydroxyapatite coatings. Biomaterials. 2005;32(26):6288–6295. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kim H. Fluor-hydroxyapatite sol–gel coating on titanium substrate for hard tissue implants. Biomaterials. 2004;17(25):3351–3358. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Gineste L. Degradation of hydroxylapatite, fluorapatite, and fluorhydroxyapatite coatings of dental implants in dogs. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 1999;3(48):224–234. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(1999)48:3<224::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Wang J. Biomimetic and electrolytic calcium phosphate coatings on titanium alloy: physicochemical characteristics and cell attachment. Biomaterials. 2004;4(25):583–592. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00559-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Barrere F. In vitro and in vivo degradation of biomimetic octacalcium phosphate and carbonate apatite coatings on titanium implants. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2003;2(64):378–387. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Aksakal B. Influence of micro- and nano-hydroxyapatite coatings on the osteointegration of metallic (Ti6Al4 V) and bioabsorbable interference screws: an in vivo study. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2014;5(24):813–819. doi: 10.1007/s00590-013-1236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Fan Y. A composite coating by electrolysis-induced collagen self-assembly and calcium phosphate mineralization. Biomaterials. 2005;14(26):1623–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.de Jonge L.T. Organic–inorganic surface modifications for titanium implant surfaces. Pharm. Res.-Dordr. 2008;10(25):2357–2369. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9617-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Alam M.I. Evaluation of ceramics composed of different hydroxyapatite to tricalcium phosphate ratios as carriers for rhBMP-2. Biomaterials. 2001;12(22):1643–1651. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Liu Y. BMP-2 liberated from biomimetic implant coatings induces and sustains direct ossification in an ectopic rat model. Bone. 2005;5(36):745–757. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Dee K.C. John Wiley & Sons; 2003. An Introduction to Tissue-Biomaterial Interactions. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Walczak J. In vivo corrosion of 316L stainless-steel hip implants: morphology and elemental compositions of corrosion products. Biomaterials. 1998;1-3(19):229–237. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Shaw B.A., Kelly R.G. What is corrosion? Interface-Electrochem. Soc. 2006;1(15):24–27. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Asri R. Corrosion and surface modification on biocompatible metals: a review. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017;C77:1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.04.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Peuster M. Long-term biocompatibility of a corrodible peripheral iron stent in the porcine descending aorta. Biomaterials. 2006;28(27):4955–4962. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Hermawan H. Springer; Heidelberg: 2012. Biodegradable Metals: from Concept to Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 155.Ray S. Strontium and bisphosphonate coated iron foam scaffolds for osteoporotic fracture defect healing. Biomaterials. 2018;157:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Su Y. Development and characterization of silver containing calcium phosphate coatings on pure iron foam intended for bone scaffold applications. Mater. Des. 2018:124–134. [Google Scholar]

- 157.Bowen P.K. Zinc exhibits ideal physiological corrosion behavior for bioabsorbable stents. Adv. Mater. 2013;18(25):2577–2582. doi: 10.1002/adma.201300226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Vojtěch D. Mechanical and corrosion properties of newly developed biodegradable Zn-based alloys for bone fixation. Acta Biomater. 2011;9(7):3515–3522. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Shearier E.R. In vitro cytotoxicity, adhesion, and proliferation of human vascular cells exposed to zinc. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016;4(2):634–642. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Kuhlmann J. Fast escape of hydrogen from gas cavities around corroding magnesium implants. Acta Biomater. 2013;10(9):8714–8721. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Su Y. Preparation and corrosion behaviors of calcium phosphate conversion coating on magnesium alloy. Surf. Coating. Technol. 2016:99–108. [Google Scholar]

- 162.Xiao X. In vitro degradation and biocompatibility of Ca-P coated magnesium alloy. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2013;2(29):285–289. [Google Scholar]

- 163.Su Y. Enhancing the corrosion resistance and surface bioactivity of a calcium-phosphate coating on a biodegradable AZ60 magnesium alloy via a simple fluorine post-treatment method. RSC Adv. 2015;69(5):56001–56010. [Google Scholar]

- 164.Zhang S. Research on an Mg–Zn alloy as a degradable biomaterial. Acta Biomater. 2010;2(6):626–640. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Kazemzadeh-Narbat M. Multilayered coating on titanium for controlled release of antimicrobial peptides for the prevention of implant-associated infections. Biomaterials. 2013;24(34):5969–5977. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Zhao L. Antibacterial coatings on titanium implants. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2009;1(91):470–480. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Bose S., Tarafder S. Calcium phosphate ceramic systems in growth factor and drug delivery for bone tissue engineering: a review. Acta Biomater. 2012;4(8):1401–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Ge X. Antibacterial coatings of fluoridated hydroxyapatite for percutaneous implants. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2010;2(95):588–599. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Bir F. Electrochemical depositions of fluorohydroxyapatite doped by Cu 2+, Zn 2+, Ag+ on stainless steel substrates. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012;18(258):7021–7030. [Google Scholar]

- 170.Huang Y. Osteoblastic cell responses and antibacterial efficacy of Cu/Zn co-substituted hydroxyapatite coatings on pure titanium using electrodeposition method. RSC Adv. 2015;22(5):17076–17086. [Google Scholar]

- 171.Kazemzadeh-Narbat M. Antimicrobial peptides on calcium phosphate-coated titanium for the prevention of implant-associated infections. Biomaterials. 2010;36(31):9519–9526. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Saidin S. Polydopamine as an intermediate layer for silver and hydroxyapatite immobilisation on metallic biomaterials surface. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2013;8(33):4715–4724. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2013.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Xie C. Silver nanoparticles and growth factors incorporated hydroxyapatite coatings on metallic implant surfaces for enhancement of osteoinductivity and antibacterial properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014;11(6):8580–8589. doi: 10.1021/am501428e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Verron E. Calcium phosphate biomaterials as bone drug delivery systems: a review. Drug Discov. Today. 2010;13–14(15):547–552. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]