Abstract

Pancreatic cystic lesions (PCLs) have been increasingly recognized in clinical practice. Although inflammatory cysts (pseudocysts) are the most common PCLs detected by cross-sectional imaging modalities in symptomatic patients in a setting of acute or chronic pancreatitis, incidental pancreatic cysts with no symptoms or history of pancreatitis are usually neoplastic cysts. For these lesions, it is imperative to identify mucinous cysts (intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms) due to the risk of their progression to malignancy. However, no single imaging modality alone is sufficient for a definitive diagnosis of all PCLs. The cyst fluid obtained by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration provides additional information for the differential diagnosis of PCLs. Current recommendations suggest sending cyst fluid for cytology evaluation and measurement of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels. Unfortunately, the sensitivity of cytology is greatly limited, and cyst fluid CEA has demonstrated insufficient accuracy as a predictor of mucinous cysts. More recently, cyst fluid glucose has emerged as an alternative to CEA for distinguishing between mucinous and nonmucinous lesions. Herein, the clinical utility of cyst fluid glucose and CEA for the differential diagnosis of PCLs was evaluated.

Keywords: Carcinoembryonic antigen, Differential diagnosis, Fine-needle biopsy, Glucose, Pancreatic cyst, Tumor marker

Core tip: Incidental pancreatic cysts have been found in far more patients with the improvement of cross-sectional imaging tests. Many of these lesions have malignant potential, especially the mucinous lesions, and imaging alone is not enough to guarantee definitive diagnosis. Cyst fluid carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) has been used as the most important cyst fluid marker to distinguish mucinous from nonmucinous cysts. More recently, glucose has emerged as a useful cyst fluid marker for the identification of pancreatic mucinous cysts with an accuracy similar to or even better than CEA.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cystic lesions (PCLs) have been detected in between 2.4% and 19.6% of the general population during imaging tests [computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)] for unrelated reasons[1,2]. In the absence of previous episodes of acute pancreatitis, which could increase the chance of pseudocysts, most of these lesions are neoplasms, and some of them have significant malignant potential, especially the intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) and mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCN)[3-5].

The accurate diagnosis of PCLs is critical to guarantee the best management for these patients, whether through surgical resection or periodic surveillance[6-8]. Unfortunately, there is no a single test accurate enough to assure a definitive diagnosis for all PCLs, particularly for those that are isolated unilocular cystic lesions, with neither perceptible communication with the main pancreatic duct (MPD) nor previous episodes of pancreatitis[9]. Therefore, a combination of information obtained from demographics, clinical history and imaging, as well as cytopathology and cyst fluid markers obtained by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA), has been used for the differential diagnosis of PCLs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions

| IPMN | MCN | PC | SCN | NET | SPN | |

| Sex | M = F | F > M | M > F | F > M | M = F | F > M |

| Age (yr) | 40-80 | 30-70 | Variable | 50-70 | 20-50 | 8-40 |

| Clinical setting | Asymptomatic Pancreatitis | Asymptomatic Pain/mass | Pancreatitis | Asymptomatic Pain/mass | Asymptomatic Pain/mass | Asymptomatic Pain/mass |

| Appearance | Dilated MPD and/or branch-ducts. Fish- mouth papilla. | Well-circumscribed macrocystic lesion | Unilocular. Thin/thick- walled. Acute/chronic pancreatitis. | Microcystic with central fibrosis/ macrocystic and solid variants are possible | Associated mass | Mixed solid and cystic with well-defined borders. |

| Location | Head | Body/tail | Anywhere | Anywhere | Body/tail | Body/tail |

| Communication with MPD | Yes | Rare | Yes/no | No | No | No |

| Calcification | No | Peripheral | Related to chronic pancreatitis | Central | In necrotic lesions. | In necrotic lesions. |

| Fluid | Clear/viscous | Clear/viscous | Thin/dark | Clear/watery | Thin | Bloody |

| Epithelium | Columnar papillary mucinous. | Columnar/cuboidal mucinous. | No epithelium. Inflammatory cells. | Serous cuboidal. Stain for glycogen. | Endocrine. Stain for synaptophysin, chromogranin | Stain for vimentin, α1-antitrypsin, β-catenin |

| Malignant potential | High | High | None | Rare | Low | Low |

| Cyst fluid CEA | Usually High | High | Low | Very low | Very low | Low |

| Cyst fluid amilase | High | Variable | High | Low | Low | Low |

IPMN: Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm; MCN: Mucinous cystic neoplasm; PC: Pseudocyst; SCN: Serous cystic neoplasm; NET: Neuroendocrine tumor; SPN: Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm; MPD: Main pancreatic duct; CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen.

Recently, a few studies reported on the value of cyst fluid glucose as an addition to the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cysts[10-12]. However, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) has been the most used cyst fluid marker to date. This review aimed to compare the roles of cyst fluid glucose and CEA for the diagnosis of mucinous and nonmucinous PCLs.

IMAGING OF PANCREATIC CYSTIC LESIONS

Noninvasive cross-sectional imaging tests (CT and MRI) are usually responsible for detecting unsuspected PCLs and represent the first diagnostic approach for these lesions. EUS is a complementary tool when the diagnosis is undetermined by clinical and cross-sectional imaging data, when there are worrisome features present, or if surgery is believed to pose a high risk. Regarding the characteristics of mucinous lesions, IPMNs are radiographically classified according to the dilation of the ductal system as main duct-IPMN (MD-IPMN), branch duct-IPMN (BD-IPMN), or mixed type-IPMN. MD-IPMN is characterized by focal or diffuse dilation of the MPD to > 5 mm (Figure 1), and by the frequent presentation of a patulous aspect of the ampullary orifice with mucus secretion. Chronic pancreatitis and ductal adenocarcinoma are the most important differential diagnoses for this type of lesion. BD-IPMN is usually a multifocal disease with normal caliber MPD (Figure 2). Mixed type-IPMN shows a dilation of the MPD and the presence of dilated side branches (Figure 3). The MCN is classically a single macrocystic lesion in the body or tail of the pancreas (Figure 4). For nonmucinous cysts, the pseudocyst is usually a thin- or thick-walled unilocular lesion that almost always occurs in the setting of an episode of acute pancreatitis or pancreatic trauma, as well as in patients with chronic pancreatitis. For serous cystic lesions, numerous microcystic lesions with thin septa are the most common presentation. Central calcified fibrosis is a classic aspect of this type of lesion[13-15].

Figure 1.

Main duct-intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Magnetic resonance imaging of a uniform dilation of the main pancreatic duct.

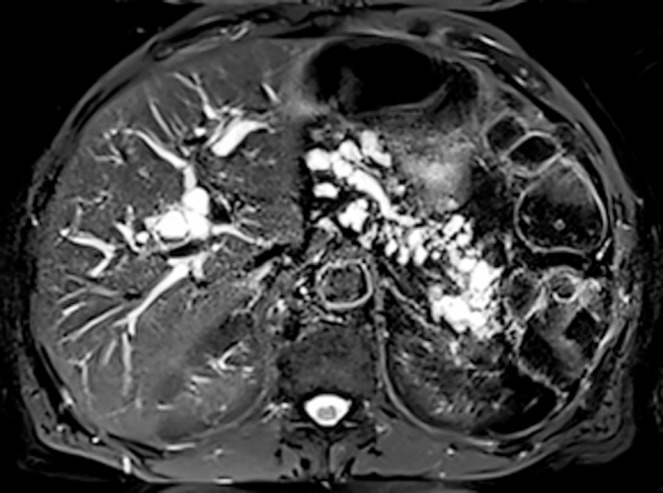

Figure 2.

Branch duct—intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography demonstrating a nondilated main pancreatic duct with multiple cystic dilated side branch ducts.

Figure 3.

Mixed-intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. The main pancreatic duct is markedly dilated in the pancreatic head with multiple dilated side branches throughout the pancreas.

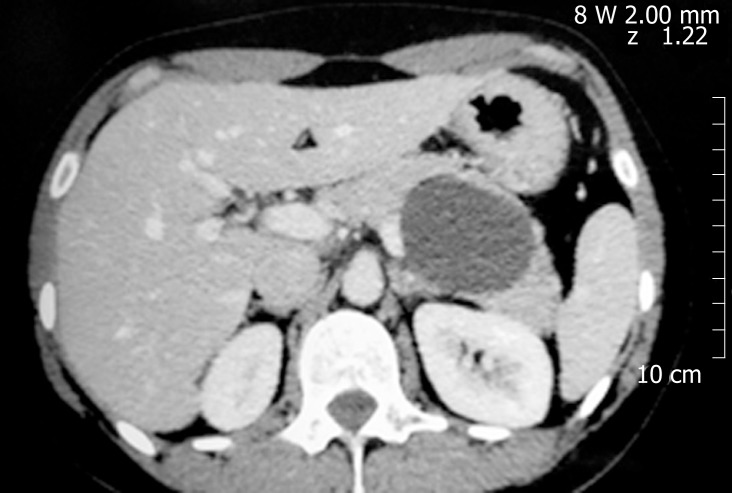

Figure 4.

Mucinous cystic neoplasm. An unilocular cyst with thin walls and homogeneous content on computed tomography in the pancreatic body.

Nevertheless, there is not an ideal imaging modality to guarantee a correct diagnosis for all PCLs. There is a significant imaging overlap for different types of PCLs, and specific cystic lesions do not always disclose their most typical imaging features. The accuracy of CT and MRI/MR cholangiopancreatography in determining a definitive diagnosis is approximately 50%[16-18]. For EUS morphology alone, there is slightly more than chance interobserver agreement among experienced endosonographers for the diagnosis of the specific types of PCLs[19].

Since imaging alone is not sufficient for a definitive diagnosis of many PCLs, EUS-FNA provides additional information that can be helpful in confirming the type of cyst. The aspirated cyst fluid allows cytological analysis, as well as assessment of biochemical and molecular factors and tumor markers.

PANCREATIC CYST FLUID ANALYSES

Cytology

Cytologic diagnosis using cystic fluid relies on the presence of confirmed malignant cells, mucin-containing cells, or glycogen-containing cells. The specificity of cytology in most studies is excellent and approaches 100%, but the sensitivity is usually unsatisfactory, especially due to the paucicellular nature of the samples and the presence of blood and benign epithelial cells from the gastric or duodenal mucosa. In a meta-analysis by Wang et al[20] of 16 studies and 1024 patients, the specificity of malignant cytology was 94%, but the sensitivity was only 51%. These data resemble those from another meta-analysis by Thornton et al[21].

Carcinoembryonic antigen

Given the unsatisfactory sensitivity of cytology for PCLs, the value of tumor markers in the aspirated cyst fluid has been examined. In the well-known multicenter prospective study by Brugge et al[22], a cut-off of 192 ng/mL for CEA demonstrated a sensitivity of 75%, specificity of 84%, and accuracy of 79% for the differential diagnosis between mucinous and nonmucinous cystic lesions. This performance was significantly better when compared to EUS morphology alone (51%) or cytology (59%) (P < 0.05). These results were corroborated in a meta-analysis by Thornton et al[21]. However, a multicenter study demonstrated a misdiagnosis of 40% for mucinous and 17% for nonmucinous lesions by using the same cut-off[23]. Given the risk of misclassification, other studies have used higher CEA thresholds in an attempt to improve the diagnostic accuracy for mucinous lesions, despite compromising the sensitivity of the marker[23-27]. A CEA level of > 800 ng/mL had a specificity ranging between 86% and 98% and a diagnostic accuracy between 58% and 79% for detecting mucinous lesions, but the sensitivity was too low, ranging from 33% to 48%[23,24,26]. On the other hand, similar results have been found with lower thresholds. Gaddam et al[23], using a cut-off value of 105 ng/mL, yielded a sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 63%, albeit 30% of mucinous lesions were misdiagnosed. With an even lower CEA cut-off of only 48.6 ng/mL, Oh et al[28] described a sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for the diagnosis of mucinous cysts of 72.4%, 94.7%, and 81.3%, respectively.

Unlike the high CEA levels and the correlation with mucinous lesions, CEA levels of < 5 ng/mL are highly suggestive of nonmucinous lesions, with sensitivity ranging from 44% to 50%, specificity higher than 95%, and diagnostic accuracy ranging from 67% to 78%[24,26]. Most of these lesions were serous cystic neoplasms in the presence of low levels of amylase. However, in the experiment of Gaddam et al[23], despite median CEA levels for serous cysts having been found to be 1.7 ng/mL, 31% of serous cysts would have been misclassified when using a cut-off of 5 ng/mL.

Thus, cyst fluid CEA alone cannot be regarded as a perfect marker for the differential diagnosis of PCLs at this time. CEA levels have been demonstrated to be insufficiently accurate as a predictor of mucinous cysts, and the optimal cut-off is controversial. The ranges of cyst fluid CEA concentration from mucinous and nonmucinous cysts overlap considerably according to the CEA cut-off used[23,24]. Cysts with viscous fluid and CEA values between 10 ng/mL and 200 ng/mL represent the most important diagnostic challenge. Particularly for IPMNs, Yoon et al[29] demonstrated that cyst fluid CEA levels vary considerably by histologic type, with the gastric and pancreatobiliary types presenting the highest median CEA concentrations (619.8 and 270 ng/mL, respectively), and the intestinal and oncocytic types presenting the lowest median concentrations (83 and 5.1 ng/mL, respectively, P = 0.012). Furthermore, there has not been a significant correlation between the risk of malignancy and cyst fluid CEA levels[28,30,31]. CEA measurement is a laborious technique that requires specific laboratory capabilities that are costly and time-consuming. Commercially available methods for CEA measurement have been validated for the analysis of serum or plasma but not for pancreatic cyst fluid, and there could be significant variation in the results among different methods. Moreover, CEA thresholds are not necessarily transferable between different methods[32].

Molecular markers in pancreatic cyst fluid seem to be promising for the future, especially with the evaluation of GNAS and KRAS[33-35]. However, molecular markers are even more expensive than CEA, the analyses are performed using specialized technologies offered in few referral laboratories, and their results take a long time to be available. Additionally, molecular profiling remains under investigation and is not widely available. Currently, other cyst fluid markers are being sought, and a combination of these markers with CEA seems to be a more reasonable alternative.

Glucose

In 2013, Park et al[10], who were looking for potential cyst fluid markers for pancreatic mucinous cysts, published, for the first time, that glucose levels were significantly lower in mucinous cysts when compared to nonmucinous cysts (5 vs 82 mg/dL, P = 0.002). The best performance for glucose was observed by using a cut-off of 66 mg/dL, with a sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy of 94%, 64%, and 84%, respectively. With this threshold, glucose had an accuracy similar to that of CEA > 192 ng/mL (84% vs 77%). Particularly for serous cystic neoplasms, glucose levels were significantly higher when compared to other cyst types (98 mg/dL vs 7 mg/dL, P = 0.0001). The diagnostic yield for the differentiation of serous cystic neoplasms at the same cut-off of 66 mg/dL had a sensitivity of 88%, a specificity of 89%, and a diagnostic accuracy of 89%. The same group validated these findings with a larger cohort two years later[11]. Sixty-five pancreatic cyst fluid samples with histological correlation were analyzed. Median glucose levels were once again lower in mucinous cysts (20 mg/dL vs 78 mg/dL, P < 0.0001). In this new study, the sensitivity and specificity for the definition of mucinous cysts at a glucose cut-off of ≤ 50 mg/dL were 88% and 78%, respectively. The standard CEA cut-off of 192 ng/mL had a sensitivity and specificity of 73% and 89%, respectively. However, the combination of both markers did not improve the diagnostic accuracy when compared to glucose or CEA alone. Recently, a well-designed study conducted by Carr et al[12] compared the cyst fluid glucose and CEA levels in samples from 153 patients with pathologically confirmed diagnoses. Median glucose levels were lower in mucinous cysts (19 vs 96 mg/dL, P < 0.0001). With the same threshold of ≤ 50 mg/dL, glucose had a sensitivity of 92%, a specificity of 87%, and a diagnostic accuracy of 90% in diagnosing mucinous cysts. All median glucose levels for mucinous cysts fell below 50 mg/dL. In comparison, a CEA threshold of > 192 ng/mL had a sensitivity of 58%, a specificity of 96%, and a diagnostic accuracy of 69% for mucinous cysts. Combining glucose and CEA for differentiating pancreatic mucinous cysts had a sensitivity of 95%, a specificity of 85%, and a diagnostic accuracy of 93% (P = 0.03). However, like CEA, cyst fluid glucose was unable to diagnose malignant disease. These studies have demonstrated that cyst fluid glucose performs similar to or even better than CEA in differentiating mucinous from nonmucinous cysts. Unlike CEA, glucose measurement is simple, rapid, inexpensive, reproducible, and requires only a few drops of cyst fluid.

In our initial experiment comparing cyst fluid glucose and CEA levels in 115 patients, glucose levels were < 50 mg/dL in 33 of 36 (91.6%) samples whose CEA levels were suggestive of mucinous pancreatic cysts at ≥ 192 ng/mL (Table 2). When CEA levels were < 5 ng/mL, suggestive of serous cystic neoplasms, glucose levels were ≥ 50 mg/dL in 48 of 51 (94.1%) samples (Table 3). Our median glucose levels in cysts whose CEA levels were ≥ 192 ng/mL and < 5 ng/mL were 5.5 mg/dL, and 98 mg/dL, respectively. The median glucose levels were 5 mg/dL in two studies evaluating mucinous cystic lesions[10,11]. On the other hand, the median glucose levels ranged between 86 and 103 mg/dL in studies evaluating serous cystic lesions[10-12]. Our findings are completely in line with the literature. Regardless these findings have not been compared to surgical pathology, they could demonstrate an almost perfect correlation between specific glucose and CEA thresholds for different types of PCLs (data not published).

Table 2.

Comparison between cyst fluid carcinoembryonic antigen and glucose levels, using a carcinoembryonic antigen cut-off suggestive of mucinous cystic neoplasms

| Glucose levels CEA levels | < 50 mg/dL | ≥ 50 mg/dL | Total |

| ≥ 192 ng/mL | 33 | 3 | 36a |

| < 192 ng/mL | 25 | 54 | 79 |

| Total | 58 | 57 | 115 |

CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen;

P < 0.0001.

Table 3.

Comparison between cyst fluid carcinoembryonic antigen and glucose levels, using a carcinoembryonic antigen cut-off suggestive of serous cystic neoplasms

| Glucose levels CEA levels | < 50 mg/dL | ≥ 50 mg/dL | Total |

| ≥ 5 ng/mL | 55 | 9 | 64a |

| < 5 ng/mL | 3 | 48 | 51 |

| Total | 58 | 57 | 115 |

CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen;

P < 0.0001.

CONCLUSION

PCLs have the potential to be malignant, and imaging, cytology, and cyst fluid CEA have demonstrated inadequate abilities for accurate diagnosis. In this context, glucose has emerged as a useful cyst fluid marker for distinguishing between mucinous and nonmucinous cysts with accuracy similar to or even better than CEA. Indeed, the initial results are promising, and more high-quality multicenter studies must reproduce these findings to corroborate cyst fluid glucose for routine use in the differential diagnosis of these lesions.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: Author does not have any conflicts of interest.

Peer-review started: January 7, 2019

First decision: March 14, 2019

Article in press: April 19, 2019

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cianci P S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

References

- 1.de Jong K, Nio CY, Hermans JJ, Dijkgraaf MG, Gouma DJ, van Eijck CH, van Heel E, Klass G, Fockens P, Bruno MJ. High prevalence of pancreatic cysts detected by screening magnetic resonance imaging examinations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:806–811. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang XM, Mitchell DG, Dohke M, Holland GA, Parker L. Pancreatic cysts: Depiction on single-shot fast spin-echo MR images. Radiology. 2002;223:547–553. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2232010815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen PJ, D'Angelica M, Gonen M, Jaques DP, Coit DG, Jarnagin WR, DeMatteo R, Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Brennan MF. A selective approach to the resection of cystic lesions of the pancreas: Results from 539 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2006;244:572–582. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000237652.84466.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernández-del Castillo C, Targarona J, Thayer SP, Rattner DW, Brugge WR, Warshaw AL. Incidental pancreatic cysts: Clinicopathologic characteristics and comparison with symptomatic patients. Arch Surg. 2003;138:427–3; discussion 433-4. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimura W, Nagai H, Kuroda A, Muto T, Esaki Y. Analysis of small cystic lesions of the pancreas. Int J Pancreatol. 1995;18:197–206. doi: 10.1007/BF02784942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Study Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas. European evidence-based guidelines on pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Gut. 2018;67:789–804. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ardengh JC, Lopes CV, de Lima-Filho ER, Kemp R, Dos Santos JS. Impact of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration on incidental pancreatic cysts. A prospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:114–120. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.854830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka M, Fernández-del Castillo C, Adsay V, Chari S, Falconi M, Jang JY, Kimura W, Levy P, Pitman MB, Schmidt CM, Shimizu M, Wolfgang CL, Yamaguchi K, Yamao K International Association of Pancreatology. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernández-Esparrach G, Ginès A. The problem of an incidental uniloculated cyst. Minerva Med. 2014;105:437–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park WG, Wu M, Bowen R, Zheng M, Fitch WL, Pai RK, Wodziak D, Visser BC, Poultsides GA, Norton JA, Banerjee S, Chen AM, Friedland S, Scott BA, Pasricha PJ, Lowe AW, Peltz G. Metabolomic-derived novel cyst fluid biomarkers for pancreatic cysts: Glucose and kynurenine. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:295–302.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zikos T, Pham K, Bowen R, Chen AM, Banerjee S, Friedland S, Dua MM, Norton JA, Poultsides GA, Visser BC, Park WG. Cyst Fluid Glucose is Rapidly Feasible and Accurate in Diagnosing Mucinous Pancreatic Cysts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:909–914. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carr RA, Yip-Schneider MT, Simpson RE, Dolejs S, Schneider JG, Wu H, Ceppa EP, Park W, Schmidt CM. Pancreatic cyst fluid glucose: Rapid, inexpensive, and accurate diagnosis of mucinous pancreatic cysts. Surgery. 2018;163:600–605. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeffrey RB. Imaging Pancreatic Cysts with CT and MRI. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1787–1795. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nougaret S, Mannelli L, Pierredon MA, Schembri V, Guiu B. Cystic pancreatic lesions: From increased diagnosis rate to new dilemmas. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2016;97:1275–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2016.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadiyala V, Lee LS. Endosonography in the diagnosis and management of pancreatic cysts. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:213–223. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahani DV, Kambadakone A, Macari M, Takahashi N, Chari S, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Diagnosis and management of cystic pancreatic lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:343–354. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sainani NI, Saokar A, Deshpande V, Fernández-del Castillo C, Hahn P, Sahani DV. Comparative performance of MDCT and MRI with MR cholangiopancreatography in characterizing small pancreatic cysts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:722–731. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Visser BC, Yeh BM, Qayyum A, Way LW, McCulloch CE, Coakley FV. Characterization of cystic pancreatic masses: Relative accuracy of CT and MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:648–656. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmad NA, Kochman ML, Brensinger C, Brugge WR, Faigel DO, Gress FG, Kimmey MB, Nickl NJ, Savides TJ, Wallace MB, Wiersema MJ, Ginsberg GG. Interobserver agreement among endosonographers for the diagnosis of neoplastic versus non-neoplastic pancreatic cystic lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:59–64. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang QX, Xiao J, Orange M, Zhang H, Zhu YQ. EUS-Guided FNA for Diagnosis of Pancreatic Cystic Lesions: A Meta-Analysis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36:1197–1209. doi: 10.1159/000430290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thornton GD, McPhail MJ, Nayagam S, Hewitt MJ, Vlavianos P, Monahan KJ. Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration for the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: A meta-analysis. Pancreatology. 2013;13:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.11.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brugge WR, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E, Centeno BA, Szydlo T, Regan S, del Castillo CF, Warshaw AL. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: A report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1330–1336. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaddam S, Ge PS, Keach JW, Mullady D, Fukami N, Edmundowicz SA, Azar RR, Shah RJ, Murad FM, Kushnir VM, Watson RR, Ghassemi KF, Sedarat A, Komanduri S, Jaiyeola DM, Brauer BC, Yen RD, Amateau SK, Hosford L, Hollander T, Donahue TR, Schulick RD, Edil BH, McCarter M, Gajdos C, Attwell A, Muthusamy VR, Early DS, Wani S. Suboptimal accuracy of carcinoembryonic antigen in differentiation of mucinous and nonmucinous pancreatic cysts: Results of a large multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:1060–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park WG, Mascarenhas R, Palaez-Luna M, Smyrk TC, O'Kane D, Clain JE, Levy MJ, Pearson RK, Petersen BT, Topazian MD, Vege SS, Chari ST. Diagnostic performance of cyst fluid carcinoembryonic antigen and amylase in histologically confirmed pancreatic cysts. Pancreas. 2011;40:42–45. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181f69f36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linder JD, Geenen JE, Catalano MF. Cyst fluid analysis obtained by EUS-guided FNA in the evaluation of discrete cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: A prospective single-center experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Waaij LA, van Dullemen HM, Porte RJ. Cyst fluid analysis in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions: A pooled analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:383–389. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)01581-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frossard JL, Amouyal P, Amouyal G, Palazzo L, Amaris J, Soldan M, Giostra E, Spahr L, Hadengue A, Fabre M. Performance of endosonography-guided fine needle aspiration and biopsy in the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1516–1524. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh SH, Lee JK, Lee KT, Lee KH, Woo YS, Noh DH. The Combination of Cyst Fluid Carcinoembryonic Antigen, Cytology and Viscosity Increases the Diagnostic Accuracy of Mucinous Pancreatic Cysts. Gut Liver. 2017;11:283–289. doi: 10.5009/gnl15650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoon WJ, Daglilar ES, Mino-Kenudson M, Morales-Oyarvide V, Pitman MB, Brugge WR. Characterization of epithelial subtypes of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas with endoscopic ultrasound and cyst fluid analysis. Endoscopy. 2014;46:1071–1077. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ngamruengphong S, Bartel MJ, Raimondo M. Cyst carcinoembryonic antigen in differentiating pancreatic cysts: A meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:920–926. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cizginer S, Turner BG, Bilge AR, Karaca C, Pitman MB, Brugge WR. Cyst fluid carcinoembryonic antigen is an accurate diagnostic marker of pancreatic mucinous cysts. Pancreas. 2011;40:1024–1028. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31821bd62f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boot C. A review of pancreatic cyst fluid analysis in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cyst lesions. Ann Clin Biochem. 2014;51:151–166. doi: 10.1177/0004563213503819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo X, Zhan X, Li Z. Molecular Analyses of Aspirated Cystic Fluid for the Differential Diagnosis of Cystic Lesions of the Pancreas: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:3546085. doi: 10.1155/2016/3546085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JH, Kim Y, Choi JW, Kim YS. KRAS, GNAS, and RNF43 mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: A meta-analysis. Springerplus. 2016;5:1172. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2847-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Springer S, Wang Y, Dal Molin M, Masica DL, Jiao Y, Kinde I, Blackford A, Raman SP, Wolfgang CL, Tomita T, Niknafs N, Douville C, Ptak J, Dobbyn L, Allen PJ, Klimstra DS, Schattner MA, Schmidt CM, Yip-Schneider M, Cummings OW, Brand RE, Zeh HJ, Singhi AD, Scarpa A, Salvia R, Malleo G, Zamboni G, Falconi M, Jang JY, Kim SW, Kwon W, Hong SM, Song KB, Kim SC, Swan N, Murphy J, Geoghegan J, Brugge W, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Mino-Kenudson M, Schulick R, Edil BH, Adsay V, Paulino J, van Hooft J, Yachida S, Nara S, Hiraoka N, Yamao K, Hijioka S, van der Merwe S, Goggins M, Canto MI, Ahuja N, Hirose K, Makary M, Weiss MJ, Cameron J, Pittman M, Eshleman JR, Diaz LA, Jr, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Karchin R, Hruban RH, Vogelstein B, Lennon AM. A combination of molecular markers and clinical features improve the classification of pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1501–1510. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]