Abstract

Objective: To highlight potential functional variants and causal genes for ischemic stroke (IS) in genomic loci identified by genome-wide association studies (GWAS).

Methods: We examined the association between m6A-SNPs and IS in large scale GWAS. Furthermore, eQTL analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of m6A-SNPs on gene expression. The top associations between m6A-SNPs and gene expressions were validated in 40 individuals from the Chinese Han population. Besides, we applied differential expression analysis and Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis to detect potential causal genes for IS.

Results: We found 310 (7.39%) m6A-SNPs which were nominally associated with IS. The proportion of m6A-SNPs with P < 0.05 for IS was significantly higher than the non-m6A-SNPs (95%CI: [5.84%, 7.36%], P = 0.02). We found that the IS-associated m6A-SNP rs2013162 was associated with IRF6 expression (P = 6.30 × 10−23), meanwhile IRF6 was differentially expressed between IS cases and controls (P = 6.15 × 10−3) and showed a causal association with IS (P = 3.64 × 10−4). Similar results were found for m6A-SNP rs2273235 in the NDST1 gene which was associated with cardioembolic stroke (P = 8.47 × 10−3). The associations of rs2013162 and rs2273235 with the expression of IRF6 and NDST1 were validated in blood cells (P = 0.0247 and 0.0007), respectively.

Conclusions: This study showed that m6A-SNPs may affect IS risk through altering gene expressions. The results suggested that m6A might play a role in IS etiology and gene expressions that affected by m6A may be causal factors for IS.

Keywords: stroke, m6A, methylation, genome-wide association study, Mendelian randomization

Introduction

Ischemic stroke (IS) is the second leading cause of death worldwide (1). As a complex disease, genetic and epigenetic factors play important roles in IS etiology. Several genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified many loci for IS and specific subtypes, including large artery stroke (LAS), cardioembolic stroke (CES), and small vessel stroke (SVS). A recent large-scale meta-analysis of GWAS in 521,612 individuals confirmed 32 IS-associated loci which offering mechanisms not previously implicated in stroke pathophysiology (2). Although previous GWAS have revolutionized the understanding of the genetic architecture of IS and provided a framework for prioritization of stroke risk variants and genes for further functional and experimental follow-up, identification of functional variants and causal genes in the GWAS loci is not finished but still a major challenge.

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is a pervasive RNA modification that plays critical roles in mRNA stability, protein expression and several other cellular processes (3). Dysregulated m6A has been linked to cell fate during the endothelial-to-hematopoietic transition (4), cardiac homeostasis (5, 6) and brain diseases (7). Genetic variants, i.e., the m6A-associated SNPs (m6A-SNPs), can influence m6A by changing the RNA sequences of the target sites (8). If m6A modification was affected by this kind of variants, the biological process would likely be modified, leading to under-/overexpression of the protein (8).

Evaluation of the effect of genetic variants on m6A modification will increase our understanding of the pathogenic molecular mechanisms and uncover new causal variants. Until now, the relationship between m6A-SNPs and IS has not yet been clearly defined. Besides, determination of the association between m6A and IS in large sample at genome-wide scale in a large sample is hard to achieve nowadays. In this study we investigated the effect of the m6A-SNPs on IS and showed that by using the GWAS identified IS-associated m6A-SNPs as a bridge we can assess the relationship between m6A and IS indirectly. Meanwhile, we highlight some potential causal genetic variants and genes for IS.

Materials and Methods

Identification of m6A-SNPs for IS

In this study, we first investigated the effect of the m6A-SNPs on IS in the published summary data of a large scale GWAS (2). This GWAS comprised 521,612 individuals. Raw data used in the present analysis was the downloaded summary results from the initial GWAS, which included association P values of almost 8 million SNPs and indels for any IS (AIS) and common etiological subtypes of LAS, CES, and SVS. These datasets were available at the MEGASTROKE website (http://megastroke.org/).

To screen out the m6A-SNPs in these 8 million SNPs, we annotated them using a list of m6A-SNPs which were downloaded from the m6AVar database (http://m6avar.renlab.org/). The list contains 13,703 high, 54,222 medium and 284,089 low confidence level m6A-SNPs for human (8). After annotation of the SNPs in the GWAS summary dataset by the list of m6A-SNPs, we identified the m6A-SNPs which were associated with IS. Those m6A-SNPs with P < 0.05 were considered in the following analyses.

Among IS-associated SNPs, we determined if m6A-SNPs were overrepresented compared to what would be expected by chance. We randomly sampled 1,000 sets of non-m6A-SNPs (the same number of m6A-SNPs) from the GWAS datasets for IS as matched background, and then determined if the proportion of m6A-SNPs with P < 0.05 was significantly higher than the proportion of non-m6A-SNPs with P < 0.05 in the 1,000 sets for each trait. Besides, to assure that allele frequency differences between m6A and non-m6A-SNPs are not driving the conclusion that there is overrepresentation of m6A-SNPs in stroke cases, we selected from allele frequency bins of 1–5, 5–10, 11–20, 21–30, 31–40, and 41–50% for each set of non-m6A-SNPs to more precisely mirror the distribution of m6A-SNPs.

eQTL Analysis

The m6A-SNPs may participate in gene expression regulation through exerting influence on RNA modification, thus they may be associated with gene expression level. We carried out the cis-acting eQTL analysis to obtain evidence on associations between the identified m6A-SNPs and gene expressions in HaploReg (https://pubs.broadinstitute.org/mammals/haploreg/haploreg.php). To validate the eQTLs we also tested genotypes and mRNA expression levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of 40 unrelated Chinese Han individuals (age range from 27 to 67) using RT-PCR method to obtain additional evidence to support the top IS-associated m6A-SNPs. PBMCs were isolated from 15 ml peripheral blood by density gradient centrifugation using Lymphoprep (Sigma, life science, USA). Total RNA and DNA were extracted in the same lab according to the instructions recommended by the manufacturer. The study was approved by the ethical committee of Soochow University. The written informed consent was obtained from all of the participants.

Differential Expression Analysis

We further tried to determine if the expression levels of genes which the IS-associated m6A-SNPs showed cis-eQTL effects on were associated with IS based on the expression profile data (GSE22255) available in the GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). GSE22255 contained data of gene expression levels in PBMCs from 20 IS cases to 20 controls (9). Differential expression was tested by comparing mean gene expression signals between cases and controls using t-test. The significance level of P = 0.05 was used for the differential expression analyses.

Mendelian Randomization Analysis

We supposed that the IS-associated m6A-SNPs affect gene expression and consequently cause IS. To obtain additional evidence to support this idea, we conducted a summary data–based Mendelian randomization (SMR) analysis (10). SMR applies the principles of MR (11, 12) to jointly analyze eQTL and GWAS summary statistics in order to test for association between gene expression and a trait due to a shared variant at a locus. A HEIDI (heterogeneity in dependent instruments) test for heterogeneity in the resulting association statistics was performed. PHEIDI > 0.05 means that there was no significant heterogeneity underlying the eQTL signals. The SMR software was downloaded from http://cnsgenomics.com/software/smr/. Genotype data of HapMap r23 CEU was used as a reference panel to calculate the linkage disequilibrium correlation for SMR analysis. The eQTL summary data from four studies were used in our SMR analysis. Westra et al. performed the largest eQTL meta-analysis so far in peripheral blood samples of 5,311 European healthy individuals (13). The genetic architecture of gene expression (GAGE) study detected eQTLs in peripheral blood in 2,765 European individuals (14). The cis-eQTL summary data from the GTEx whole blood (15) and brain (16) were used. Only SNPs within 1 Mb of the transcription start site are available for these two GTEx datasets.

Results

IS-associated m6A-SNPs

We found about 4,000 m6A-SNPs in each the GWAS datasets for AIS, LAS, CES, and SVS. Among these SNPs, 310 (7.39%), 305 (6.72%), 279 (6.18%), and 205 (6.26%) were nominally (P < 0.05) associated with AIS, LAS, CES, and SVS, respectively. The proportion of m6A-SNPs which have GWAS P < 0.05 for AIS was significantly higher than the non-m6A-SNPs (95%CI: [5.84%, 7.36%], P = 0.02). But it's not for LAS (95%CI: [5.55%, 6.94%], P = 0.09), CES (95%CI: [5.45%, 6.82%], P = 0.45), or SVS (95%CI: [5.10%, 6.84%], P = 0.26), which were analyzed in smaller sample than AIS. In the original METASTROKE GWAS, SNPs with minor allele frequencies (MAF) ≥ 0.01 were examined. Therefore, the MAF of SNPs considered in our study was ≥0.01. In fact, the MAF of about 90% of the 321 IS-associated SNPs were >0.05. The distributions of MAF were not different between m6A-SNPs and non-m6A-SNPs with P < 0.05 (goodness-of-fit test P = 0.1551). While selected from allele frequency bins of 1–5% (number of SNPs sampled n = 583), 6–10% (n = 663), 11–20% (n = 1,064), 21–30% (n = 720), 31–40% (n = 628), and 41–50% (n = 539) for each of the 1,000 sets of non-m6A-SNPs to mirror the distribution of m6A-SNPs for AIS, we also found that the proportion of m6A-SNPs with P < 0.05 was significantly higher than the non-m6A-SNPs (95%CI: [5.89%, 7.29%], P = 0.014).

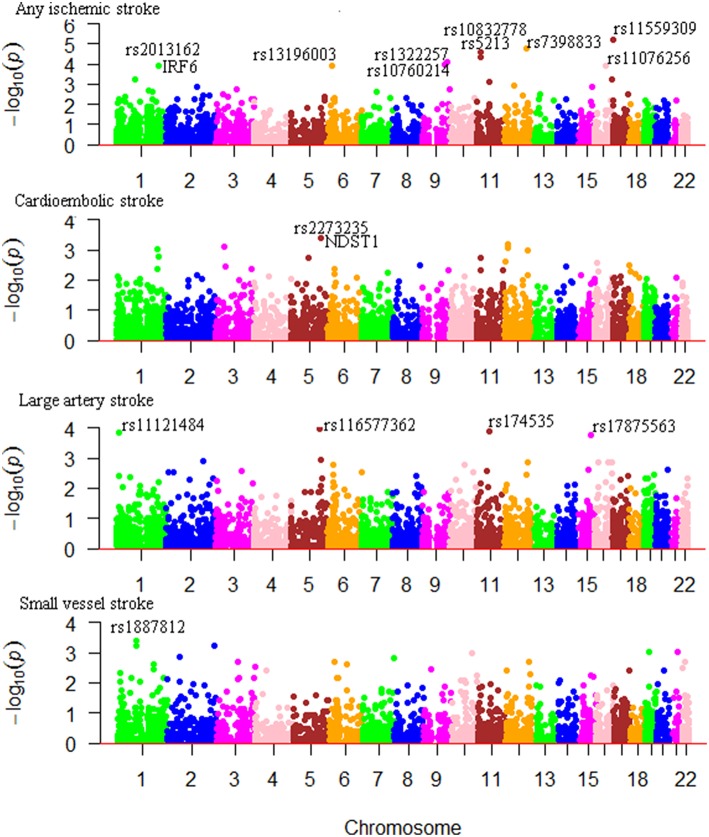

We considered Bonferroni-correction for the results (P < 0.05/4000 for roughly 4000 SNPs). The association between m6A-SNPs rs11559309 (PRPF8, P = 6.18 × 10−6) and AIS reached the significance level of 1.25 × 10−5, followed by rs7398833 (P = 1.78 × 10−5) in CUX2 gene, rs5213 (P = 2.46 × 10−5) in KCNJ11 gene and rs10832778 (P = 4.25 × 10−5) in NCR3LG1 gene. The most significant m6A-SNPs for LAS, CES, and SVS were rs174535 (P = 6.05 × 10−5) in MYRF gene, rs2273235 (P = 3.99 × 10−4) in NDST1 gene and rs1887812 (P = 4.05 × 10−4) in BRDT gene (Table 1; Figure 1), respectively.

Table 1.

The identified m6A-SNPs for ischemic stroke.

| SNP | CHR | SNP position | MAF | Gene | Mutation Type | P-value≠ | m6A_ID | m6A position | m6A function | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRAN | EURO | eQTL | DEG | SMR | |||||||||

| AIS | |||||||||||||

| rs2013162 | 1 | 209968684 | 0.3736 | IRF6 | Syn | 1.27E-04 | 6.73E-04 | 6.30E-23 | 6.15E-03 | 3.64E-04 | m6A_ID_132331 | 209968661 | Loss |

| rs13196003 | 6 | 24535999 | 0.0725 | ALDH5A1 | UTR3 | 1.29E-04 | 3.36E-04 | m6A_ID_189376 | 24535978 | Loss | |||

| rs1322257 | 9 | 114480562 | 0.0112 | C9orf84 | Nonsyn | 1.02E-04 | 8.28E-03 | m6A_ID_226979 | 114480545 | Gain | |||

| rs10760214 | 9 | 125002246 | 0.4763 | RBM18 | UTR3 | 7.54E-05 | 6.38E-04 | 1.29E-35 | 2.44E-03 | m6A_ID_227927 | 125002247 | Loss | |

| rs10832778 | 11 | 17394073 | 0.3885 | NCR3LG1 | UTR3 | 4.25E-05 | 3.97E-04 | 1.18E-17 | m6A_ID_244519 | 17394071 | Gain | ||

| rs5213 | 11 | 17408404 | 0.3615 | KCNJ11 | UTR3 | 2.46E-05 | 4.49E-04 | 7.57E-13 | 7.21E-04 | m6A_ID_27449 | 17408423 | Loss | |

| rs7398833 | 12 | 111786892 | 0.2509 | CUX2 | UTR3 | 1.78E-05 | 2.46E-05 | 1.51E-02 | m6A_ID_265695 | 111786917 | Gain | ||

| rs11076256 | 16 | 58752466 | 0.0818 | GOT2 | Nonsyn | 1.29E-04 | 3.46E-03 | m6A_ID_43360 | 58752472 | Loss | |||

| rs11559309 | 17 | 1556911 | 0.0374 | PRPF8 | Syn | 6.18E-06 | 7.83E-06 | m6A_ID_301320 | 1556907 | Gain | |||

| LAS | |||||||||||||

| rs11121484 | 1 | 9784423 | 0.0769 | PIK3CD | Syn | 1.40E-04 | 1.18E-02 | 4.20E-02 | m6A_ID_112617 | 9784425 | Gain | ||

| rs116577362 | 5 | 140242897 | 0.0215 | PCDHA | Nonsyn | 1.04E-04 | 1.04E-04 | m6A_ID_184329 | 140242899 | Loss | |||

| rs174535 | 11 | 61551356 | 0.3392 | MYRF | Nonsyn | 1.31E-04 | 6.05E-05 | m6A_ID_247771 | 61551331 | Gain | |||

| rs17875563 | 15 | 81604293 | 0.2405 | IL16 | UTR3 | 1.67E-04 | 1.83E-03 | 9.52E-09 | 3.97E-02 | m6A_ID_287576 | 81604291 | Gain | |

| CES | |||||||||||||

| rs2273235 | 5 | 149907533 | 0.4821 | NDST1 | Syn | 3.99E-04 | 1.04E-03 | 3.23E-07 | 2.65E-02 | 8.47E-03 | m6A_ID_185695 | 149907528 | Loss |

| SVS | |||||||||||||

| rs1887812 | 1 | 92414993 | 0.2074 | BRDT | UTR5 | 4.05E-04 | 8.51E-04 | m6A_ID_121270 | 92414991 | Loss | |||

AIS, Any ischemic stroke; CES, Cardioembolic stroke; CHR, Chromosome; DEG, Differential expression gene; eQTL, Expression quantitative trait; LAS, Large artery stroke; MAF, Minor allele frequency (in Europeans); Nonsyn, Nonsynonymous; SMR, Summary data based Mendelian randomization; SNP, Single nucleotide polymorphism; SVS, Small vessel stroke; Syn, Synonymous; UTR, Untranslated region. †Assembly: GRCh37.p13. ≠TRAN: stroke association P values based-on trans ethnic data; EURO, Stroke association P-values based-on European-only data.

Figure 1.

Genome-wide results for the association between m6A-SNPs and IS. The Manhattan plots show –log10P values for the m6A-SNPs associated with IS and subtypes. The data was from the IS GWAS published by the MEGASTROKE consortium at 2018 (2).

eQTL Analysis

To further clarify the possible functional mechanisms underlying the identified m6A-SNPs in association with IS, we investigated whether they were associated with gene expression levels. In total, 6 of the 15 IS-associated m6A-SNPs showed cis-eQTL signals with the 6 local genes in different cells or tissues (Table 1; Table S1). The 5 IS-associated m6A-SNPs (except rs10832778) might alter regulatory motifs (17) (Table S1). Besides, rs7398833 (CUX2) was associated with expression of ALDH2 (P = 1.47 × 10−5), ATXN2 (P = 2.74 × 10−6), FAM109A (P = 3.41 × 10−3) and SH2B3 (P = 1.27 × 10−10), and rs174535 (MYRF) was associated with expression of FADS1 (P = 2.37 × 10−31), FADS2 (P = 6.68 × 10−28), and TMEM258 (P = 1.00 × 10−56).

Differential Expression Analysis

For the genes which were presented in Table 1, we compared mRNA expression signals in an expression study. In this expression dataset, we found that IRF6, CUX2, PIK3CD and NDST1 were differentially expressed in PBMCs (P < 0.05) (Table 1). Among them, the expression levels of IRF6 and NDST1 were affected by rs2013162 (P = 6.30 × 10−23) and rs2273235 (P = 3.23 × 10−7) according to eQTL data from HaploReg, respectively. It means that these 2 m6A-SNPs may affect IS through altering the local gene.

Mendelian Randomization Analysis

The SMR analysis identified several genes as potential causal genes underlying IS GWAS association (PSMR < 5 × 10−6), and there was no significant heterogeneity underlying the eQTL signals (PHEIDI > 0.05) (Table S2). For the 15 genes listed in Table 1, SMR tests (P < 3.33 × 10−3 were considered significant) identified that three genes (IRF6, RBM18 and KCNJ11) were significantly associated with AIS, IL16 was associated with LAS and NDST1 was associated with CES (Table 1). All of these five genes passed the HEIDI tests (PHEIDI > 0.05).

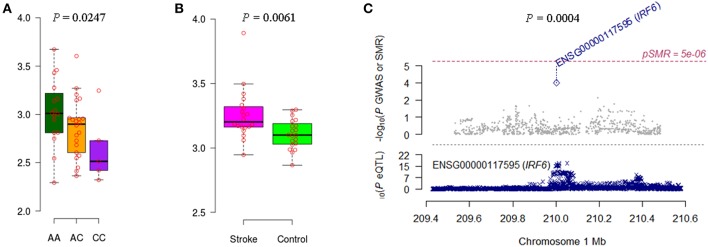

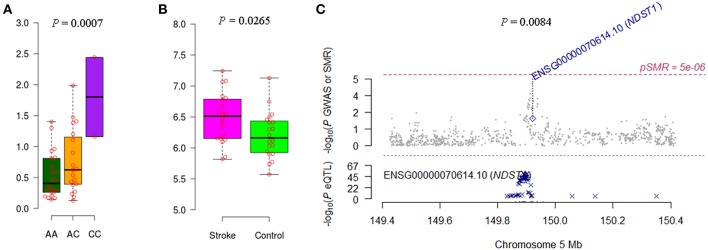

The SNP-Expression-IS Trios

We noticed that IRF6 and NDST1 showed more convincing evidence. For example, the IFR6 SNPs achieved suggestive evidence of association with AIS (P < 5 × 10−5) (Figure S1). The AIS-associated (P = 1.27 × 10−4) m6A-SNP rs2013162 may affect IRF6 expression (P = 6.30 × 10−23), IRF6 was differentially expressed between IS cases and controls (P = 6.15 × 10−3) and showed a causal association with AIS (PSMR = 3.64 × 10−4, PHEIDI = 0.11). The association between NDST1 SNPs and CES did not reach the genome-wide significance level but many SNPs that were in linkage disequilibrium showed suggestive evidence (Figure S2). The CES-associated (P = 3.99 × 10−4) m6A-SNP rs2273235 may affect NDST1 expression (P = 3.23 × 10−7), NDST1 was differentially expressed between IS cases and controls (P = 2.65 × 10−2) and showed a causal association with CES (PSMR = 8.47 × 10−3, PHEIDI = 0.65). So subsequently, we tested the association between rs2013162 and rs2273235 and mRNA expression levels of IRF6 and NDST1, respectively. The MAF for rs2013162 and rs2273235 were 0.3736 and 0.4821 in Europeans (Table 1), and 0.3721 and 0.2674 in the Han Chinese population according to our 40 sample, respectively. These two SNPs were high-frequency variants in both of the European and East Asian populations. We validated that rs2013162 and rs2273235 were significantly associated with IRF6 and NDST1 expression levels in PBMCs from the Chinese Han individuals (linear regression P = 0.0247 and 0.0007) (Figures 2, 3), respectively.

Figure 2.

Association between rs2013162 and IRF6 expression and AIS. (A) The minor allele C carriers of rs2013162 tend to have lower IRF6 gene expression levels in PBMCs of Chinese individuals. (B) IRF6 was differentially expressed between IS cases and controls according to the data of GSE22255. (C) IRF6 expression seems to be causally associated with AIS (PSMR = 3.64 × 10−4, PHEIDI = 0.11).

Figure 3.

Association between rs2273235 and NDST1 expression and CES. (A) The minor allele C carriers of rs2273235 tend to have higher NDST1 gene expression levels in PBMCs of Chinese individuals. (B) NDST1 was differentially expressed between IS cases and controls according to the data of GSE22255. (C) NDST1 expression seems to be causally associated with CES (PSMR = 8.47 × 10−3, PHEIDI = 0.65).

Discussion

This study represents the first effort to identify putative functional variants and causal genes for IS by integrating m6A-SNPs data, gene expression data and genetic association data from large scale GWAS. We found out several m6A-SNPs (e.g., rs2013162 and rs2273235) which may be putative functional variants for IS. Moreover, we also showed that these SNPs have potential to affect transcription regulation and were associated with expressions of the local genes (e.g., IRF6 and NDST1). These genes may be potential causal genes for IS.

It seems that m6A-SNPs may be causally associated with IS by influencing gene expression. Studies have shown that m6A modification plays a pivotal role in the regulation of downstream molecular events such as nuclear export, stability, translatability, splicing, and miRNA processing (18). So one of the functional interpretations for the effect of m6A-SNPs on IS could be their influence on gene expression levels. Then if the m6A-SNP is causal SNP, the affected gene should be causal gene. In this study we detected several potential causal genes for IS based on large data of eQTL and GWAS. For these genes, we validated the association between m6A-SNPs and gene expression (e.g., IRF6 and NDST1) in public and in-house data. This finding supported our hypothesis that m6A-SNPs may be causally associated with IS by influencing gene expression.

The IRF6 gene encodes a member of the IRF family of transcription factors which play roles in cardiovascular diseases (19, 20). IRF6 is likely to promote inflammation to Porphyromonas gingivalis through its regulation of IL-36γ (21), and exhibits tumor suppressor activity in squamous cell carcinomas (22). The RIPK4-IRF6 signaling axis plays a multifaceted role in barrier epithelial homeostasis through its regulation of both keratinocyte inflammation and differentiation (23). IRF6 also contributes to host defense by providing specificity to the regulation of inflammatory chemokine expression by TLR2 in epithelial cells (24). The synonymous m6A-SNP rs2013162 in IRF6 (1q32.2) has been well studied on disease. This SNP was not reported in the original METASTROKE GWAS (2). But by looking up the published GWAS data, we found that rs2013162 was also associated with intracerebral hemorrhage (P = 3.26 × 10−4) (25) and large artery atherosclerosis-related stroke (P = 9.34 × 10−3) (26).

NDST1 encodes a bifunctional GlcNAc N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase with important functions in biosynthesis of heparan sulfate, which play roles in triglyceride-rich lipoprotein clearance (27), stroke (28, 29), and allergic airway inflammation through the regulation of recruitment of inflammatory cells to the airways by mediating interaction of leukocytes with the vascular endothelium (30). Suppression of NDST1 in endothelial cells results in reduced responsiveness to VEGFA (31), which plays important role in cardiovascular diseases. The synonymous m6A-SNP rs2273235 in NDST1 (5q33.1) was associated with CES in two GWAS (2, 32). This SNP has the potential to alter regulatory motifs Evi-1, NF-AT1 and PTF1-beta, and locates in a CpG island (CpG: 19) and near DNase I hypersensitive sites (Figure S3). All in all, the identified m6A-SNPs and genes can be suggested as important candidates for further genetic association and functional studies.

This study has several limitations. First, no genome-wide significant associations between m6A-SNPs and IS was found. The significant associations proposed in this paper were at the borderline level of statistical significance after multiple testing adjustments. Second, the sample size of the differential gene expression study was small, so very few associations between gene expression levels and IS have been identified. Third, only a very small proportion of m6A-SNPs were examined in this study. To fully recognize the impact of m6A-SNPs on IS, we still need to identify more m6A-SNPs (especially the rare variants) and the effects of the large amounts of m6A-SNPs on IS should be evaluated in larger GWAS datasets. Finally, the functionalities of the detected SNPs, especially effects on m6A modification, have not been experimentally validated. Further experiments are needed to determine their functions.

Conclusions

In summary, the present study found out several IS-associated m6A-SNPs, and showed that these SNPs may affect the expressions of the local genes which might be potential causal genes for IS. This study increases our understanding on the regulation patterns of SNP. Although we found supplementary functional information to support the significant findings, further functional studies were needed to elucidate the mechanisms.

Data Availability

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript and/or the Supplementary Files.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of Soochow University with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Soochow University.

Author Contributions

X-BM, S-FL, Y-HZ, and HZ contributed at all stages of manuscript preparation. HZ critically appraised and approved the final manuscript. All authors were involved in data recording and discussed the results.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. The study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (81773508, 81673263), the Key Research Project (Social Development Plan) of Jiangsu Province (BE2016667), the Startup Fund from Soochow University (Q413900313, Q413900412), and a Project of the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions. The MEGASTROKE project received funding from sources specified at http://www.megastroke.org/acknowledgments.html. All MEGASTROKE authors were listed in Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2019.00517/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. (2017) 390:1151–210. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malik R, Chauhan G, Traylor M, Sargurupremraj M, Okada Y, Mishra A, et al. Multiancestry genome-wide association study of 520,000 subjects identifies 32 loci associated with stroke and stroke subtypes. Nat Genet. (2018) 50:524–37. 10.1038/s41588-018-0058-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fu Y, Dominissini D, Rechavi G, He C. Gene expression regulation mediated through reversible m(6)A RNA methylation. Nat Rev Genet. (2014) 15:293–306. 10.1038/nrg3724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang C, Chen Y, Sun B, Wang L, Yang Y, Ma D, et al. m(6)A modulates haematopoietic stem and progenitor cell specification. Nature. (2017) 549:273–6. 10.1038/nature23883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathiyalagan P, Adamiak M, Mayourian J, Sassi Y, Liang Y, Agarwal N, et al. FTO-dependent N(6)-methyladenosine regulates cardiac function during remodeling and repair. Circulation. (2019) 139:518–32. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.033794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorn LE, Lasman L, Chen J, Xu X, Hund TJ, Medvedovic M, et al. The N(6)-methyladenosine mRNA methylase METTL3 controls cardiac homeostasis and hypertrophy. Circulation. (2019) 139:533–45. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hess ME, Hess S, Meyer KD, Verhagen LA, Koch L, Bronneke HS, et al. The fat mass and obesity associated gene (Fto) regulates activity of the dopaminergic midbrain circuitry. Nat Neurosci. (2013) 16:1042–8. 10.1038/nn.3449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng Y, Nie P, Peng D, He Z, Liu M, Xie Y, et al. m6AVar: a database of functional variants involved in m6A modification. Nucleic Acids Res. (2018) 46:D139–D45. 10.1093/nar/gkx895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krug T, Gabriel JP, Taipa R, Fonseca BV, Domingues-Montanari S, Fernandez-Cadenas I, et al. TTC7B emerges as a novel risk factor for ischemic stroke through the convergence of several genome-wide approaches. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. (2012) 32:1061–72. 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu Z, Zhang F, Hu H, Bakshi A, Robinson MR, Powell JE, et al. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat Genet. (2016) 48:481–7. 10.1038/ng.3538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith GD, Ebrahim S. 'Mendelian randomization': can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol. (2003) 32:1–22. 10.1093/ije/dyg070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davey Smith G, Hemani G. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Hum Mol Genet. (2014) 23:R89–98. 10.1093/hmg/ddu328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westra HJ, Peters MJ, Esko T, Yaghootkar H, Schurmann C, Kettunen J, et al. Systematic identification of trans eQTLs as putative drivers of known disease associations. Nat Genet. (2013) 45:1238–43. 10.1038/ng.2756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lloyd-Jones LR, Holloway A, McRae A, Yang J, Small K, Zhao J, et al. The genetic architecture of gene expression in peripheral blood. Am J Hum Genet. (2017) 100:228–37. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Battle A, Brown CD, Engelhardt BE, Montgomery SB. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature. (2017) 550:204–13. 10.1038/nature24277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi T, Wu Y, Zeng J, Zhang F, Xue A, Jiang L, et al. Identifying gene targets for brain-related traits using transcriptomic and methylomic data from blood. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:2282. 10.1038/s41467-018-04558-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kheradpour P, Kellis M. Systematic discovery and characterization of regulatory motifs in ENCODE TF binding experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. (2014) 42:2976–87. 10.1093/nar/gkt1249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Visvanathan A, Somasundaram K. mRNA traffic control reviewed: N6-Methyladenosine (m(6) A) takes the driver's seat. Bioessays. (2018) 40:1700093 10.1002/bies.201700093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo S, Li ZZ, Jiang DS, Lu YY, Liu Y, Gao L, et al. IRF4 is a novel mediator for neuronal survival in ischaemic stroke. Cell Death Differ. (2014) 21:888–903. 10.1038/cdd.2014.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szelag M, Piaszyk-Borychowska A, Plens-Galaska M, Wesoly J, Bluyssen HA. Targeted inhibition of STATs and IRFs as a potential treatment strategy in cardiovascular disease. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:48788–812. 10.18632/oncotarget.9195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huynh J, Scholz GM, Aw J, Kwa MQ, Achuthan A, Hamilton JA, et al. IRF6 regulates the expression of IL-36gamma by human oral epithelial cells in response to Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Immunol. (2016) 196:2230–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.1501263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Botti E, Spallone G, Moretti F, Marinari B, Pinetti V, Galanti S, et al. Developmental factor IRF6 exhibits tumor suppressor activity in squamous cell carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2011) 108:13710–5. 10.1073/pnas.1110931108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwa MQ, Scholz GM, Reynolds EC. RIPK4 activates an IRF6-mediated proinflammatory cytokine response in keratinocytes. Cytokine. (2016) 83:19–26. 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwa MQ, Nguyen T, Huynh J, Ramnath D, De Nardo D, Lam PY, et al. Interferon regulatory factor 6 differentially regulates Toll-like receptor 2-dependent chemokine gene expression in epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. (2014) 289:19758–68. 10.1074/jbc.M114.584540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woo D, Falcone GJ, Devan WJ, Brown WM, Biffi A, Howard TD, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies 1q22 as a susceptibility locus for intracerebral hemorrhage. Am J Hum Genet. (2014) 94:511–21. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.International Stroke Genetics Consortium (ISGC) NSGNS. Loci associated with ischaemic stroke and its subtypes (SiGN): a genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol. (2016) 15:174–84. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00338-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanford KI, Wang L, Castagnola J, Song D, Bishop JR, Brown JR, et al. Heparan sulfate 2-O-sulfotransferase is required for triglyceride-rich lipoprotein clearance. J Biol Chem. (2010) 285:286–94. 10.1074/jbc.M109.063701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khelif Y, Toutain J, Quittet MS, Chantepie S, Laffray X, Valable S, et al. A heparan sulfate-based matrix therapy reduces brain damage and enhances functional recovery following stroke. Theranostics. (2018) 8:5814–27. 10.7150/thno.28252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill JJ, Jin K, Mao XO, Xie L, Greenberg DA. Intracerebral chondroitinase ABC and heparan sulfate proteoglycan glypican improve outcome from chronic stroke in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2012) 109:9155–60. 10.1073/pnas.1205697109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zuberi RI, Ge XN, Jiang S, Bahaie NS, Kang BN, Hosseinkhani RM, et al. Deficiency of endothelial heparan sulfates attenuates allergic airway inflammation. J Immunol. (2009) 183:3971–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kasza Z, Fredlund Fuchs P, Tamm C, Eriksson AS, O'Callaghan P, Heindryckx F, et al. MicroRNA-24 suppression of N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase-1 (NDST1) reduces endothelial cell responsiveness to vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA). J Biol Chem. (2013) 288:25956–63. 10.1074/jbc.M113.484360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malik R, Traylor M, Pulit SL, Bevan S, Hopewell JC, Holliday EG, et al. Low-frequency and common genetic variation in ischemic stroke: the METASTROKE collaboration. Neurology. (2016) 86:1217–26. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript and/or the Supplementary Files.