Abstract

Aging is associated with reduced muscle mass (sarcopenia) and poor bone quality (osteoporosis), which together increase the incidence of falls and bone fractures. It is widely appreciated that aging triggers systemic oxidative stress, which can impair myoblast cell survival and differentiation. We previously reported that arginase plays an important role in oxidative stress-dependent bone loss. We hypothesized that arginase activity is dysregulated with aging in muscles and may be involved in muscle pathophysiology. To investigate this, we analyzed arginase activity and its expression in skeletal muscles of young and aged mice. We found that arginase activity and arginase 1 expression were significantly elevated in aged muscles. We also demonstrated that SOD2, GPx1, and NOX2 increased with age in skeletal muscle. Most importantly, we also demonstrated elevated levels of peroxynitrite formation and uncoupling of eNOS in aged muscles. Our in vitro studies using C2C12 myoblasts showed that the oxidative stress treatment increased arginase activity, decreased cell survival, and increased apoptotic markers. These effects were reversed by treatment with an arginase inhibitor, 2(S)-amino-6-boronohexanoic acid (ABH). Our study provides strong evidence that L-arginine metabolism is altered in aged muscle and that arginase inhibition could be used as a novel therapeutic target for age-related muscle complications.

1. Introduction

Aging is associated with reduced muscle mass (sarcopenia) and strength (dynapenia), which can increase the incidence of falls and bone fractures [1]. As the number of older adults continues to increase, the problem of muscle loss becomes a significant public health concern [1–3]. Falls and fractures in turn lead to prolonged disability, poor quality of life, and significant financial burden [4]. It is widely appreciated that aging triggers systemic oxidative stress, which can impair myoblast differentiation and cell survival, which also leads to muscle loss [5, 6]. Recent studies have shown that elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) have deleterious effects on the musculoskeletal system and are critical in muscle-related pathophysiology [5–10]. At the molecular level, generation of ROS elicits a wide range of effects on cells such as autophagy, cell differentiation and proliferation arrest, DNA damage, and cell death by activation of numerous cell signaling pathways [5, 6]. We previously reported that oxidative stress decreases cell attachment, proliferation, and migration of bone marrow stromal cells and antioxidant supplementation can reverse these effects [11].

We recently reported that bone marrow stromal cells express arginase 1 (ARG1) and its expression is regulated by high glucose [12]. Arginase is an enzyme which metabolizes L-arginine to form urea and L-ornithine in the urea cycle. There are two known arginase isoforms: arginase 1 (ARG1) and arginase 2 (ARG2). ARG1 is a cytosolic enzyme and is expressed most abundantly in the liver where it plays a vital role in the urea cycle, while ARG2 is located in mitochondria of various cell types [13]. Arginine is a semiessential amino acid which is the substrate for both nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and arginase enzyme. ARG1 is known to regulate oxidative stress in various degenerative diseases by modulating nitric oxides (NO) [14–16]. Recent studies indicated that NO is one of the important therapeutic targets for a number of cardiovascular and age-related diseases [17–19]. Our laboratory previously reported that ARG1 expression is elevated in diabetic bone and bone marrow [12]. Furthermore, diabetic bones were osteoporotic in nature. Interestingly, we found that treatment with the ARG1 inhibitor improved the quality of diabetic mice [12]. Based on our previous studies, we speculate that ARG1 becomes dysregulated in aged muscle. Until now, little is known about the role of oxidative stress in ARG1 regulation in aging muscle.

In the present study, we investigated the arginase activity and arginase 1 expression in aged muscles. We also analyzed the expression of important oxidative stress-related signaling molecules in muscles of aged mice. Furthermore, we performed in vitro studies on the myoblast cell line (C2C12) and arginase inhibitor (ABH) to investigate the role of arginase in myoblast pathophysiology. We found elevated levels of ROS accumulation and ARG1 expression/arginase activity and uncoupling of eNOS in aged muscles. Additionally, our in vitro studies showed that the arginase inhibitor prevented the formation of ROS accumulation and NOS uncoupling in myoblasts and improves the physiological health of myoblast cells.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Animal Preparation and Experimental Design

All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Augusta University. Male C57BL/6 mice from 3 months and 22 months of age (10 mice per age group) were obtained from the aged rodent colony at the National Institute on Aging. Animals were housed in a 12 h light/dark cycle and had free access to food and water throughout the study. Mice were sacrificed, and the quadriceps muscle was dissected free from the hindlimb and used for protein isolation for arginase activity, western blot, and RNA isolation.

2.2. Arginase Activity Assay

Muscle homogenate lysates were prepared in Tris buffer (50 mM Tris HCl, 0.1 mmol/L EDTA and EGTA (pH 7.5), containing protease inhibitors) and were used for the arginase activity assay as previously described [12]. Briefly, 25 μL of 10 mM MnCl2 was added to 25 μL of homogenates (cell or tissue) and heated at 57°C for 10 min to activate arginase. Next, 50 μL of 0.5 M L-arginine was then added to the reaction tube and incubated at 37°C for 1 h, and 400 μL of acid mixture (H2SO : H3PO4 : H2O in a ratio of 1 : 3 : 7) was added to stop the reaction. Then, 25 μL of 9% a-isonitrosopropiophenone (in ethanol) was added, and the mixture was heated for 45 min at 100°C and placed in the dark for 10 min to develop color. Arginase activity was measured by loading 200 μL of the reaction mixture in a 96-well plate, and absorbance was read at 540 nm.

2.3. Isolation of RNA, Synthesis of cDNA, and Real-Time PCR

Real-time PCR was performed as per our published method [11, 12]. Total RNA was isolated from the quadriceps muscles of mice. The muscle was homogenized and dissolved in TRIzol. RNA was isolated using the TRIzol method following the manufacturer's instructions, and the quality of the RNA preparations was monitored by absorbance at 260 and 280 nm (Helios Gamma, Thermo Spectronic, Rochester, NY). The RNA was reverse-transcribed into complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) using iScript reagents from Bio-Rad on a programmable thermal cycler (PCR Sprint, Thermo Electron, Milford, MA). The cDNA (50 ng) was amplified by real-time PCR using a Bio-Rad iCycler and ABgene reagents (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and ARG1 primers [12]. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as the internal control for normalization.

2.4. Western Blot Analysis

Protein was extracted from quadriceps muscle and cell culture lysate, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were incubated with a polyclonal antibody against glutathione peroxidase (GPx1), superoxide dismutase (SOD2) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), NOX2, 3-NT, eNOS (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with an appropriate secondary antibody. Proteins were visualized with an ECL western blot detection system (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). For detection of eNOS dimers, we ran a low-temperature SDS-PAGE (LT-PAGE) gel using reported procedures [20] with slight modification. The protein lysates were prepared using 1× Laemmli buffer without 2-mercaptoethanol. The samples were then subjected to SDS-PAGE with 7.5% gel and run at a low temperature by keeping the buffer tank surrounded by ice. The gels were transferred, and the blots were probed as described above.

2.5. Arginase Inhibitor Prevents C2C12 Cells from Oxidative Stress Damage

C2C12 cells were cultured and pretreated with or without the arginase inhibitor ABH (100 μM) for 4 h followed by hydrogen peroxide (100 μM) treatment alone or in combination with ABH for 24 h. Arginase activity, RT-PCR, MTT assay, and staining were performed as described below. Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide levels were detected in culture cells with dihydroethidium (DHE) staining dye as previously described [21, 22]. C2C12 cells were incubated with the DHE dye mentioned above in PBS for 30 min at 37°C. Fluorescence was monitored using a fluorescence microscope at 20x magnification.

2.6. Cell Survival Assay

To investigate the effect of oxidative stress on C2C12 cell survival, the CellTiter 96® AQueous One MTS Cell Assay kit (Promega, G3580) was used as per the published method [23, 24]. After cell culture treatment (as described above), cells were washed twice with PBS and 150 μL of MTS (CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Reagent, Promega) assay buffer was added. Cells were then incubated for 2 h at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Optical density (OD) was read at 490 nm.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism 5 (La Jolla, CA) was utilized to perform one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni pairwise comparison or unpaired t-tests as appropriate. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Elevated Level of Arginase Activity and Expression in Aged Muscles

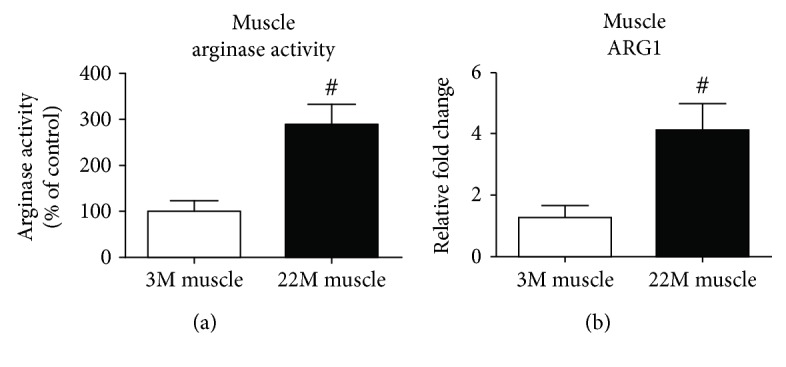

Our published data demonstrated that chronic oxidative stress increased arginase activity in various disease conditions [12, 21, 22]. We hypothesized that arginase expression and activity became dysregulated in aged muscles. Our data showed that this is indeed the case that arginase activity (p value = 0.01) and arginase 1 expression (p value = 0.01) were significantly elevated in 22-month-old aged muscle (Figure 1). Previously, our group reported that muscle mass declined significantly between 18 and 24 months of age [25].

Figure 1.

Aging increases arginase activity and mRNA expression in muscles. (a) Arginase activity was determined using an assay for urea formation in muscle lysates from young and old muscles, and (b) real-time PCR analysis of Arg1 mRNA in young and old mice. Data for each sample were normalized to GAPDH mRNA and represented as the fold change in expression compared to young mice. Results are means ± SD (n = 5-6 #p < 0.01); data were analyzed using an unpaired t-test.

3.2. Elevated Level of Oxidative Stress in Aged Muscle

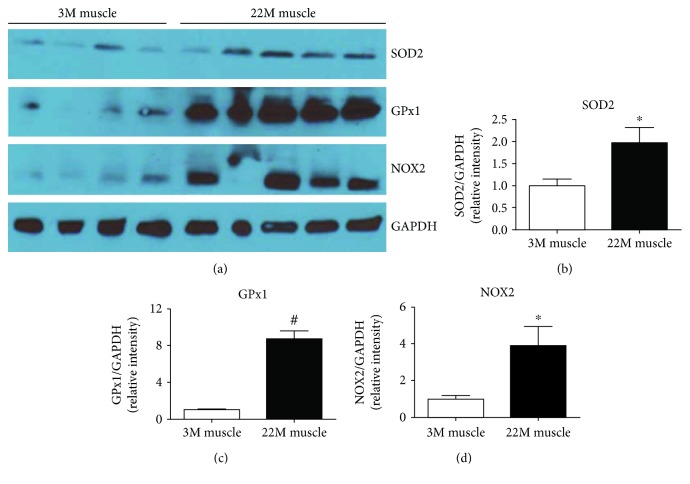

To evaluate the activities of the antioxidant defense system in aged muscles, we determined the level of superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) and glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPx1). SOD2 and GPx1 are antioxidant enzymes that play a vital role in the suppression or prevention of the formation of free radical or reactive species in cells and tissues [26, 27]. Our western blot data showed that SOD2 (p value = 0.05) and GPx1 (p value = 0.001) antioxidant enzymes significantly (p value = 0.04) increased in the muscle from 22-month-old mice compared to 3-month-old young animals [28, 29].

NADPH oxidase is one of the important enzymes known for generation of reactive oxygen species with age [28, 29]. We analyzed NOX2 (gp91-phox) levels in young (3 months) and old (22 months) mouse muscle samples. We found a significant (p value = 0.039) increase in NOX2 level in old muscles compared to young muscles (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Elevated level of oxidative stress in young and old mouse muscles. (a) Representative western blots of protein extracted from young and old muscle samples. Densitometry quantification of (b) SOD2, (c) NOX2, and (d) GPx1. Values are normalized to the expression levels of the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Results are means ± SD (n = 5-6, ∗p < 0.05, #p < 0.01); data were analyzed using an unpaired t-test.

3.3. Increased Peroxynitrite and ROS in Aging Muscles

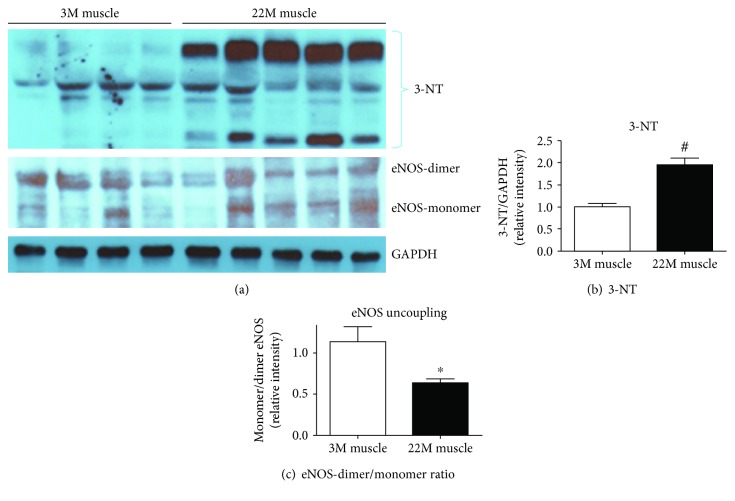

Aging affects the ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) homeostasis, which leads to musculoskeletal-related complications. ROS and RNS play important roles in various age-related diseases including sarcopenia [5, 6, 8–10]. We investigated the RNS status in aged muscle using 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT), a specific marker for reactive nitrogen species [30]. Our data demonstrated that 22-month-old muscles have significantly (p value = 0.0041) higher levels of 3-NT compared to young muscles (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)). Elevated levels of 3-NT in aged muscles suggest activation of the nitrating pathway and production of increased reactive nitrogen intermediate products.

Figure 3.

Elevated level of peroxynitrite (ONOO−) formation and uncoupling of eNOS in aged muscle. (a) Representative western blots of protein extracted from young and old muscle samples for 3-NT and eNOS uncoupling. Densitometry quantification of (b) 3-NT and (c) eNOS uncoupling. Values are normalized to the expression levels of the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Results are means ± SD (n = 5-6, ∗p < 0.05, #p < 0.01); data were analyzed using an unpaired t-test.

3.4. Dysregulation of the Monomer-to-Dimer Ratio (Uncoupling) of eNOS in Aged Mouse Muscles

Previously, eNOS uncoupling is related to several age-related diseases [20, 31–33]. We hypothesized that eNOS might be uncoupled because of the elevated level of oxidative stress in aged muscles. We analyzed the eNOS monomer and dimer in young and old muscles using a low-temperature SDF-PAGE gel. We found significant (p value = 0.04) uncoupling of eNOS in aged muscles (Figures 3(a) and 3(c)). The ratio of eNOS monomer to dimer was significantly higher in aged muscles compared to young muscles (Figures 3(a) and 3(c)).

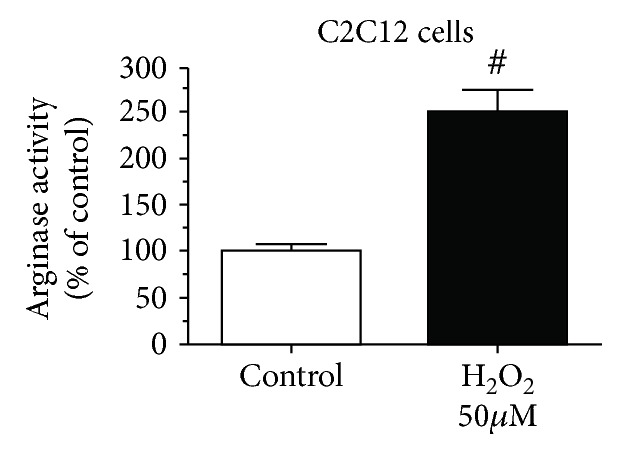

3.5. Oxidative Stress Regulates Arginase Activity in Myoblasts (C2C12 Cells)

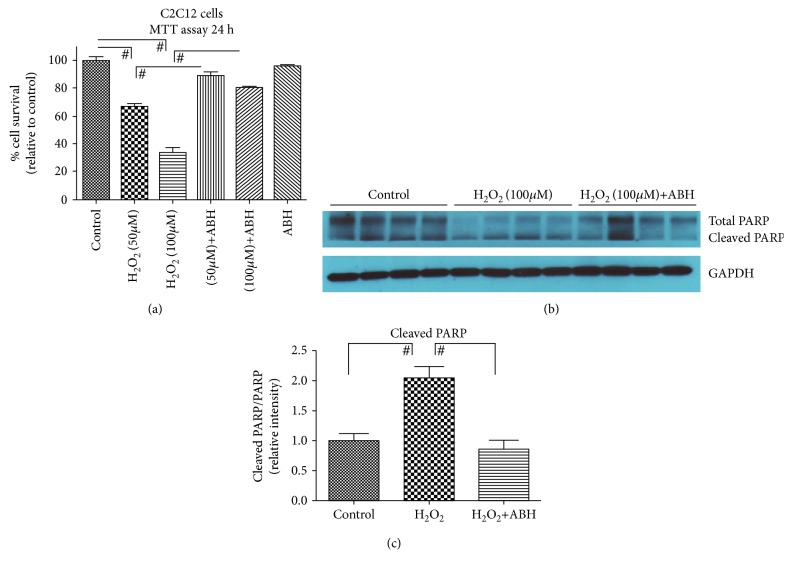

Our data (Figure 1) demonstrates that arginase activity and ARG1 expression are upregulated in muscles with aging. To further demonstrate the role of arginase in oxidative stress-dependent myoblast biology and cell survival, we treated C2C12 cells with hydrogen peroxide (oxidative stress) and estimated arginase activity. We found significantly (p value = 0.01) elevated levels of arginase activity in H2O2-treated cells (Figure 4). Based on this data, we hypothesized that an arginase inhibitor might prevent cells from the harmful effects of oxidative stress. We subjected cells to oxidative stress in the presence or absence of the arginase inhibitor (ABH), performed a cell survival assay, and investigated cell apoptotic markers. The cell survival assay was performed using the MTS assay, in which we found a dose-dependent significant (p value = 0.001) decrease in the C2C12 cell number in oxidative stress samples, and the arginase inhibitor prevents cell death (p value = 0.001) (Figure 5(a)). Western blot analysis of the apoptotic marker (cleaved PARP) showed a significant (p value = 0.01) increase in cleaved PARP in the presence of oxidative stress. Treatment with the arginase inhibitor prevented this effect (Figures 5(b) and 5(c)).

Figure 4.

Effect of oxidative stress on arginase activity on myoblasts. C2C12 cells were incubated in DMEM (2% FBS, 50 mM L-arginine) with and without hydrogen peroxide (50 μM) for 48 h. Arginase activity in cell lysate was determined by the arginase activity assay (#p < 0.01, n = 6).

Figure 5.

Arginase inhibitor prevents C2C12 cells from oxidative stress damage. (a) C2C12 cells were treated with H2O2 (50 and 100 μM) in the presence or absence of ABH (100 μM) for 24 h. MTS analysis was performed after 24 h following treatment. (b) Representative western blots for total PARP and cleaved PARP on C2C12 cells. (c) Densitometry ratio of total PARP and cleaved PARP. Values are normalized to the expression levels of the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test (#p < 0.01, n = 8).

3.6. Arginase Inhibitor Prevents Superoxide Radical Formation in C2C12 Cells

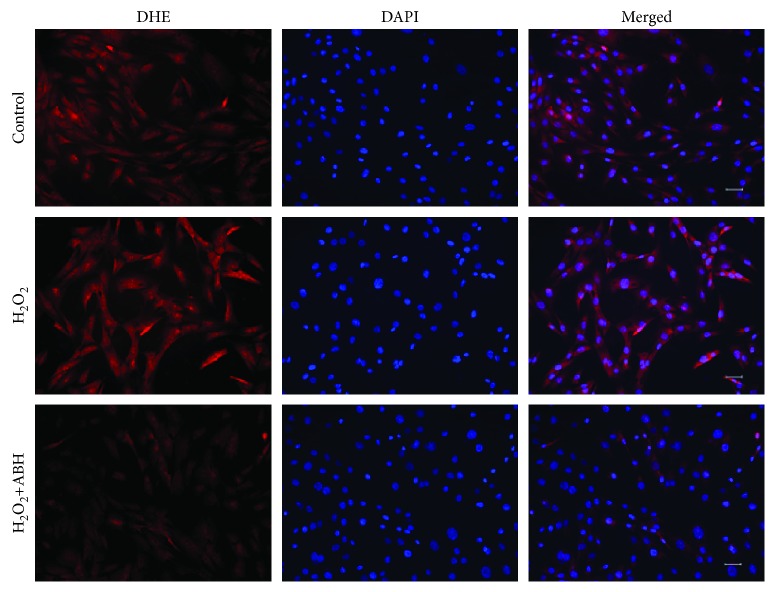

To assess the involvement of arginase in myoblasts during oxidative stress, we performed in vitro studies using C2C12 cells. C2C12 cells were cultured and treated with H2O2 to induce oxidative stress in the presence or absence of the arginase inhibitor (ABH) and stained with DHE staining dye. Dihydroethidium (DHE) is a cell-permeable dye that reacts with a superoxide anion and forms a red fluorescent product [34]. Our data showed increased red fluorescence in oxidative stress-subjected samples. Increased fluorescence of DHE staining in the cells revealed increased superoxide radical formation. Furthermore, treatment with ABH (Figure 6) prevented the increase in DHE fluorescence indicating the prevention of superoxide production in cells.

Figure 6.

Fluorescence microscopy images show that the arginase inhibitor prevents the accumulation of ROS in C2C12 cells. C2C12 cells were treated with H2O2 (50 μM) in the presence or absence of ABH (100 μM) for 24 h. ROS production was detected by DHE staining. Representative fluorescent images show that the arginase inhibitor prevents the accumulation of ROS in C2C12 cells.

4. Discussion

Aging affects the homeostasis of ROS, which is characterized by the increased accumulation of intracellular hydrogen peroxide/RNS and decreased antioxidant properties of cells/tissues. Imbalance (generation and elimination) in the homeostasis of ROS leads to musculoskeletal pathophysiology, such as muscle atrophy and fibrosis [6, 35]. When ROS levels are above the physiologic level, cells respond to stress through compensatory mechanisms by increasing antioxidant signaling to prevent the damaging effects of ROS. In chronic stress conditions, such as aging, ROS levels continue to increase while antioxidant systems become hampered, leading to muscle atrophy and fibrosis. Previously, our group and others have shown accumulation of reactive oxygen species and muscle loss with age [6, 25, 35–38]. We hypothesized that with aging, elevated levels of oxidative stress increase arginase activity and ARG1 expression in muscle.

In this study, we analyzed the expression of arginase 1 and its activity in young and aged muscles. Our study is the first to demonstrate both arginase activity and expression elevation with age in muscles. Recently, we demonstrated the elevated levels of oxidative stress and ARG1 expression in diabetic mouse bone and bone marrow [12]. Furthermore, our group also demonstrated ARG1 dysregulation in various tissues and organs of diabetic and hypertension disease models [12, 21, 22, 39–42].

Previously, our group reported that NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) activation led to elevated ROS and ARG1 expression and activity in diabetic retinal endothelial dysfunction [43]. NADPH oxidase plays an important role in the production of superoxide free radicals to protect cells from foreign microorganisms [44]. Controlled regulation of NADPH oxidase is important to maintain the health level of ROS. Chronic stress continuously elevates NADPH oxidase, which is harmful for cells and induces degenerative effect [43]. We speculate that NADPH oxidase 2 expression might be affected by aging. To investigate this, we assessed the expression of NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2). As expected, we found elevated level of NOX2 expressed in aged muscles compared to young muscles. Whitehead and his group [45] previously reported elevated NADPH oxidase expression in tibialis anterior muscles from dystrophic (mdx) mice. Similar results were also reported by Heymes et al. [46] in the pathophysiology of human congestive heart failure. We hypothesized that aging-induced oxidative stress (e.g., NOX2) elevates arginase expression, thus limiting L-arginine bioavailability and reducing NO production in muscle. Elevated arginase activity can limit the bioavailability of L-arginine to NOS causing its uncoupling, which results in less NO formation and more superoxide (O2·-) production. The NO rapidly reacts with O2·- to produce peroxynitrite (ONOO−), another potent oxidant [47]. It has been well established that peroxynitrite participates in oxidation reactions, which results in the modification of amino acid residue of proteins (protein tyrosine nitration) leading to degenerative changes [48, 49]. We speculate that in aged muscles, peroxynitrite level might be higher than that in young muscles. We analyzed the presence of 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) in young and old muscles, which indirectly measures the presence of peroxynitrite [50]. We found increased level of 3-NT in aged muscle compared to young muscle. Pearson et al. [51] also reported similar findings with ours showing elevated level of 3-NT in gastrocnemius muscles of old mice.

Formation of peroxynitrite and superoxide affects eNOS uncoupling in various age-related diseases [20, 31–33]. In this study, we demonstrated that the eNOS monomer-to-dimer ratio is disturbed in aged muscles. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first study to directly demonstrate eNOS uncoupling in aged muscle. Low-temperature SDF-PAGE gel demonstrated a higher eNOS monomer-to-dimer ratio in aged muscles. For the effective function of eNOS, dimerization of eNOS is required, which catalyzes the L-arginine to generate NO [52]. Our in vitro data further confirm the above findings; we used mouse myoblast (C2C12) cell lines to perform these studies. Subjecting C2C12 cells to oxidative stress resulted in elevated level of ROS and arginase activity, and pretreatment with the arginase inhibitor reversed the effects suggesting the role of arginase in myoblast pathophysiology. We also found that oxidative stress decreases C2C12 cell survival and increases cell apoptosis, while the arginase inhibitor prevented this effect.

Overall, our study showed that aging elevates arginase activity, which contributes to less NO production due to competition for L-arginine and eNOS uncoupling. Further studies are needed to fully understand the mechanism of age-induced increases in arginase activity and its specific role in uncoupling of eNOS. Our study demonstrated that limiting arginase activity in muscle with aging can prevent or slow down the degenerative effect. Further studies are needed to investigate the therapeutic role of the arginase inhibitor in age-related muscle loss/complications. The aging population is at increased risk of falls and fractures due to low muscle mass and strength [1–3]. As the number of older adults continues to increase, the problem of muscle loss becomes a significant public health concern. Our study outcome has a significant translational impact because it suggested that the arginase inhibitor could be used as a novel therapeutic target for age-related muscle loss.

Acknowledgments

This publication is based upon the work supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIA-AG036675—SF, MH, and CS).

Data Availability

The quantitative data used to support the findings of this study will be available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors also declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Curtis E., Litwic A., Cooper C., Dennison E. Determinants of muscle and bone aging. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2015;230(11):2618–2625. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrucci L., Baroni M., Ranchelli A., et al. Interaction between bone and muscle in older persons with mobility limitations. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2014;20(19):3178–3197. doi: 10.2174/13816128113196660690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peel N. M. Epidemiology of falls in older age. Canadian Journal on Aging. 2011;30(1):7–19. doi: 10.1017/S071498081000070X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazur K., Wilczyński K., Szewieczek J. Geriatric falls in the context of a hospital fall prevention program: delirium, low body mass index, and other risk factors. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2016;11:1253–1261. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S115755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espinosa A., Henríquez-Olguín C., Jaimovich E. Reactive oxygen species and calcium signals in skeletal muscle: a crosstalk involved in both normal signaling and disease. Cell Calcium. 2016;60(3):172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozakowska M., Pietraszek-Gremplewicz K., Jozkowicz A., Dulak J. The role of oxidative stress in skeletal muscle injury and regeneration: focus on antioxidant enzymes. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 2015;36(6):377–393. doi: 10.1007/s10974-015-9438-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalle S., Rossmeislova L., Koppo K. The role of inflammation in age-related sarcopenia. Frontiers in Physiology. 2017;8, article 1045 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.01045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nemes R., Koltai E., Taylor A. W., Suzuki K., Gyori F., Radak Z. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species regulate key metabolic, anabolic, and catabolic pathways in skeletal muscle. Antioxidants. 2018;7(7):p. 85. doi: 10.3390/antiox7070085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fougere B., van Kan G. A., Vellas B., Cesari M. Redox systems, antioxidants and sarcopenia. Current Protein & Peptide Science. 2018;19(7):643–648. doi: 10.2174/1389203718666170317120040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossi P., Marzani B., Giardina S., Negro M., Marzatico F. Human skeletal muscle aging and the oxidative system: cellular events. Current Aging Science. 2008;1(3):182–191. doi: 10.2174/1874609810801030182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sangani R., Pandya C. D., Bhattacharyya M. H., et al. Knockdown of SVCT2 impairs in-vitro cell attachment, migration and wound healing in bone marrow stromal cells. Stem Cell Research. 2014;12(2):354–363. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatta A., Sangani R., Kolhe R., et al. Deregulation of arginase induces bone complications in high-fat/high-sucrose diet diabetic mouse model. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2016;422:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narayanan S. P., Rojas M., Suwanpradid J., Toque H. A., Caldwell R. W., Caldwell R. B. Arginase in retinopathy. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2013;36:260–280. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rath M., Müller I., Kropf P., Closs E. I., Munder M. Metabolism via arginase or nitric oxide synthase: two competing arginine pathways in macrophages. Frontiers in Immunology. 2014;5:p. 532. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estévez A. G., Sahawneh M. A., Lange P. S., Bae N., Egea M., Ratan R. R. Arginase 1 regulation of nitric oxide production is key to survival of trophic factor-deprived motor neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(33):8512–8516. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0728-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunt J. B., Nash K. R., Placides D., et al. Sustained arginase 1 expression modulates pathological tau deposits in a mouse model of tauopathy. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2015;35(44):14842–14860. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3959-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pernow J., Jung C. The emerging role of arginase in endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. Current Vascular Pharmacology. 2016;14(2):155–162. doi: 10.2174/1570161114666151202205617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Z., Ming X. F. Arginase: the emerging therapeutic target for vascular oxidative stress and inflammation. Frontiers in Immunology. 2013;4:p. 149. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Z., Ming X. F. Endothelial arginase: a new target in atherosclerosis. Current Hypertension Reports. 2006;8(1):54–59. doi: 10.1007/s11906-006-0041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Y. M., Huang A., Kaley G., Sun D. eNOS uncoupling and endothelial dysfunction in aged vessels. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2009;297(5):H1829–H1836. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00230.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L., Bhatta A., Toque H. A., et al. Arginase inhibition enhances angiogenesis in endothelial cells exposed to hypoxia. Microvascular Research. 2015;98:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suwanpradid J., Rojas M., Behzadian M. A., Caldwell R. W., Caldwell R. B. Arginase 2 deficiency prevents oxidative stress and limits hyperoxia-induced retinal vascular degeneration. PLoS One. 2014;9(11, article e110604) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fulzele S., Arounleut P., Cain M., et al. Role of myostatin (GDF-8) signaling in the human anterior cruciate ligament. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2010;28(8):1113–1118. doi: 10.1002/jor.21112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sangani R., Periyasamy-Thandavan S., Pathania R., et al. The crucial role of vitamin C and its transporter (SVCT2) in bone marrow stromal cell autophagy and apoptosis. Stem Cell Research. 2015;15(2):312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamrick M. W., Ding K. H., Pennington C., et al. Age-related loss of muscle mass and bone strength in mice is associated with a decline in physical activity and serum leptin. Bone. 2006;39(4):845–853. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ighodaro O. M., Akinloye O. A. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alexandria Journal of Medicine. 2018;54(4):287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ajme.2017.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pham-Huy L. A., He H., Pham-Huy C. Free radicals, antioxidants in disease and health. International Journal of Biomedical Science. 2008;4(2):89–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan L. M., Cahill-Smith S., Geng L., Du J., Brooks G., Li J. M. Aging-associated metabolic disorder induces Nox2 activation and oxidative damage of endothelial function. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 2017;108:940–951. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du Z., Yang Q., Liu L., et al. NADPH oxidase 2-dependent oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and apoptosis in the ventral cochlear nucleus of D-galactose-induced aging rats. Neuroscience. 2015;286:281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shu L., Vivekanandan-Giri A., Pennathur S., et al. Establishing 3-nitrotyrosine as a biomarker for the vasculopathy of Fabry disease. Kidney International. 2014;86(1):58–66. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson J. M., Bivalacqua T. J., Lagoda G. A., Burnett A. L., Musicki B. eNOS-uncoupling in age-related erectile dysfunction. International Journal of Impotence Research. 2011;23(2):43–48. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2011.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thum T., Fraccarollo D., Schultheiss M., et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling impairs endothelial progenitor cell mobilization and function in diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56(3):666–674. doi: 10.2337/db06-0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu C., Yu Y., Montani J. P., Ming X. F., Yang Z. Arginase-I enhances vascular endothelial inflammation and senescence through eNOS-uncoupling. BMC Research Notes. 2017;10(1):p. 82. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2399-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Q., Chai Y. C., Mazumder S., et al. The late increase in intracellular free radical oxygen species during apoptosis is associated with cytochrome c release, caspase activation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2003;10(3):323–334. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi M. H., Ow J. R., Yang N. D., Taneja R. Oxidative stress-mediated skeletal muscle degeneration: molecules, mechanisms, and therapies. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2016;2016:13. doi: 10.1155/2016/6842568.6842568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rigamonti E., Touvier T., Clementi E., Manfredi A. A., Brunelli S., Rovere-Querini P. Requirement of inducible nitric oxide synthase for skeletal muscle regeneration after acute damage. Journal of Immunology. 2013;190(4):1767–1777. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bettis T., Kim B. J., Hamrick M. W. Impact of muscle atrophy on bone metabolism and bone strength: implications for muscle-bone crosstalk with aging and disuse. Osteoporosis International. 2018;29(8):1713–1720. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4570-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novotny S. A., Warren G. L., Hamrick M. W. Aging and the muscle-bone relationship. Physiology. 2015;30(1):8–16. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00033.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fouda A. Y., Xu Z., Shosha E., et al. Arginase 1 promotes retinal neurovascular protection from ischemia through suppression of macrophage inflammatory responses. Cell Death & Disease. 2018;9(10):p. 1001. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1051-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shosha E., Xu Z., Narayanan S. P., et al. Mechanisms of diabetes-induced endothelial cell senescence: role of arginase 1. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018;19(4, article 1215) doi: 10.3390/ijms19041215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Toque H. A., Nunes K. P., Rojas M., et al. Arginase 1 mediates increased blood pressure and contributes to vascular endothelial dysfunction in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension. Frontiers in Immunology. 2013;4:p. 219. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao L., Bhatta A., Xu Z., et al. Obesity-induced vascular inflammation involves elevated arginase activity. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2017;313(5):R560–R571. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00529.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rojas M., Lemtalsi T., Toque H. A., et al. NOX2-induced activation of arginase and diabetes-induced retinal endothelial cell senescence. Antioxidants. 2017;6(2):p. 43. doi: 10.3390/antiox6020043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Behe P., Segal A. W. The function of the NADPH oxidase of phagocytes, and its relationship to other NOXs. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2007;35(5):1100–1103. doi: 10.1042/BST0351100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whitehead N. P., Yeung E. W., Froehner S. C., Allen D. G. Skeletal muscle NADPH oxidase is increased and triggers stretch-induced damage in the mdx mouse. PLoS One. 2010;5(12, article e15354) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heymes C., Bendall J. K., Ratajczak P., et al. Increased myocardial NADPH oxidase activity in human heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003;41(12):2164–2171. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00471-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jourd'heuil D., Jourd'heuil F. L., Kutchukian P. S., Musah R. A., Wink D. A., Grisham M. B. Reaction of superoxide and nitric oxide with peroxynitrite. Implications for peroxynitrite-mediated oxidation reactions in vivo. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(31):28799–28805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Radi R. Protein tyrosine nitration: biochemical mechanisms and structural basis of functional effects. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2013;46(2):550–559. doi: 10.1021/ar300234c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feeney M. B., Schöneich C. Tyrosine modifications in aging. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2012;17(11):1571–1579. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ceriello A., Mercuri F., Quagliaro L., et al. Detection of nitrotyrosine in the diabetic plasma: evidence of oxidative stress. Diabetologia. 2001;44(7):834–838. doi: 10.1007/s001250100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pearson T., McArdle A., Jackson M. J. Nitric oxide availability is increased in contracting skeletal muscle from aged mice, but does not differentially decrease muscle superoxide. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 2015;78:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.10.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen W., Xiao H., Rizzo A. N., Zhang W., Mai Y., Ye M. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase dimerization is regulated by heat shock protein 90 rather than by phosphorylation. PLoS One. 2014;9(8, article e105479) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The quantitative data used to support the findings of this study will be available from the corresponding author upon request.