Abstract

Objective

To determine acute and long-term clinical, neuropsychological, and return-to-work (RTW) effects of electrical injuries (EIs). This study aims to further contrast sequelae between low-voltage and high-voltage injuries (LVIs and HVIs). We hypothesise that all EIs will result in substantial adverse effects during both phases of management, with HVIs contributing to greater rates of sequelae.

Design

Retrospective cohort study evaluating EI admissions between 1998 and 2015.

Setting

Provincial burn centre and rehabilitation hospital specialising in EI management.

Participants

All EI admissions were reviewed for acute clinical outcomes (n=207). For long-term outcomes, rehabilitation patients, who were referred from the burn centre (n=63) or other burn units across the province (n=65), were screened for inclusion. Six patients were excluded due to pre-existing psychiatric conditions. This cohort (n=122) was assessed for long-term outcomes. Median time to first and last follow-up were 201 (68–766) and 980 (391–1409) days, respectively.

Outcome measures

Acute and long-term clinical, neuropsychological and RTW sequelae.

Results

Acute clinical complications included infections (14%) and amputations (13%). HVIs resulted in greater rates of these complications, including compartment syndrome (16% vs 4%, p=0.007) and rhabdomyolysis (12% vs 0%, p<0.001). Rates of acute neuropsychological sequelae were similar between voltage groups. Long-term outcomes were dominated by insomnia (68%), anxiety (62%), post-traumatic stress disorder (33%) and major depressive disorder (25%). Sleep difficulties (67%) were common following HVIs, while the LVI group most frequently experienced sleep difficulties (70%) and anxiety (70%). Ninety work-related EIs were available for RTW analysis. Sixty-one per cent returned to their preinjury employment and 19% were unable to return to any form of work. RTW rates were similar when compared between voltage groups.

Conclusions

This is the first investigation to determine acute and long-term patient outcomes post-EI as a continuum. Findings highlight substantial rates of neuropsychological and social sequelae, regardless of voltage. Specialised and individualised early interventions, including screening for mental health concerns, are imperative to improvingoutcomes of EI patients.

Keywords: electrical injuries, burns, rehabilitation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study evaluated broad sequelae, including clinical, neuropsychological and return-to-work parameters during acute and long-term intervals, which have not been collectively investigated for electrical injuries in prior studies.

Outcome measures included a comprehensive list of neuropsychological symptoms and diagnoses that have not been contrasted between voltage groups in existing literature.

Due to the longitudinal nature of our outcomes of interest, and the associated loss to follow-up, our findings may underrepresent the long-term neuropsychosocial sequelae within our study cohorts.

Introduction

Electrical injuries (EIs) account for approximately 5% of all annual burn admissions in North America, yet are a leading cause of occupational burns worldwide.1 These injuries result in substantial limitations that impede return-to-work (RTW) and decrease quality of life.2–5 Several studies globally have proposed that EIs are implicated in persistent functional, cognitive and neuropsychological sequelae, including flashbacks, depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3 5–16 However, clinical evidence regarding such effects is limited, as the majority of reported findings are based on case reports or small clinical studies.17

Additionally, uncertainty with EI classification remains. EIs can be classified in various ways and defined as either high or low voltage. Currently, an EI below 1000 V is considered a low-voltage injury (LVI), whereas one of 1000 V or greater is considered a high-voltage injury (HVI). These voltage categories have been defined based on arcing risk.18 Clear classification is necessary as LVIs and HVIs have been suggested to result in different clinical courses. For example, two recent reviews found that HVIs experience longer hospital stays and greater rates of complications relative to LVIs.19–21 Differences between these EI subgroups during the acute and long-term phases of treatment are currently unknown.

Within our provincial healthcare system, a large proportion of EI survivors are treated at a single acute care surgical site, the Ross Tilley Burn Centre (RTBC) at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (SHSC). Typically, patients requiring ongoing inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation services are managed at St. John’s Rehabilitation Hospital (SJRH), which additionally serves as a referral site for other acute care centres and the workplace injury insurance system. Fewer sites allow for the centralisation of services and collection of information for an uncommon diagnosis across multiple phases of care.

There are two primary objectives to this study. First, we aim to determine the effects of EIs on the clinical course of acute hospitalisation and long-term outcomes during rehabilitation. Second, we aim to examine and contrast individual short-term and long-term outcomes by voltage (HVI vs LVI). We hypothesise that EIs result in substantial morbidity during acute hospitalisation and are associated with significant impairments in rehabilitation, RTW and neuropsychology. Additionally, we expect HVIs to be implicated in more adverse clinical sequelae, longer rehabilitation phases and poorer long-term outcomes.

Materials and methods

Study design

We conducted a cohort study of all EI patients admitted to RTBC and SJRH between November 1998, the date of RTBC establishment at SHSC, and December 2015. Patients were defined as HVI (≥1000 V) or LVI (<1000 V), based on the voltage documented at the time of acute admission at RTBC or from existing records at the time of entering rehabilitation at SJRH.

We defined EI sequelae during two phases of treatment: (1) acutely, defined as the initial hospital admission at RTBC and (2) long-term, defined as the period of inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation at SJRH. The long-term cohort included both patients treated at RTBC and those referred from other acute care centres. Patients with pre-existing psychiatric diagnoses, as identified in the admissions note from RTBC or SJRH medical records, were excluded from analysis of neuropsychological and RTW sequelae. Substance misuse was not included in our exclusion criteria (online supplementary figure 1).

bmjopen-2018-025990supp001.pdf (603KB, pdf)

Acute period outcomes

Injury, demographic and clinical outcomes data were obtained through retrospective chart review of RTBC progress and summary notes. Variables collected included mean age, sex, median percentage of the total body surface area (%TBSA), presence of inhalation injury, work-related nature of the injury, voltage (HVI vs LVI) and EI type (flash, contact, both contact and flash, lightning or unspecified).

Clinical outcomes during the acute period that were collected included length of stay (LOS) at RTBC, LOS adjusted for %TBSA (LOS/%TBSA), number of amputations, amputation levels and number of operations. Incidences of mortality, rhabdomyolysis, compartment syndrome, one or more infections, sepsis, multiple organ failure and rehabilitation requirements (inpatient or outpatient) were additionally analysed.

Patients transferred to SJRH for rehabilitation underwent neuropsychological screening by the care team prior to discharge, as part of the required referral documentation. This screen was observational and included the following symptoms: depressed mood, anxiety, flashbacks, avoidance, hypervigilance, hyperarousal, nightmares, sleep difficulties, social withdrawal, suicidal ideations, memory and concentration difficulties, dizziness, headaches and phantom limb pain.

Long-term period outcomes

Injury, demographic and neuropsychological outcomes data for patients in the long-term cohort were obtained through chart review of SJRH documentation. Variables collected included voltage (HVI vs LVI), work-related nature of the EI and occupation. Neuropsychological symptoms identified from rehabilitation records were depressed mood, anxiety, flashbacks, avoidance, hypervigilance, hyperarousal, nightmares, sleep difficulties, social withdrawal, suicidal ideations, memory and concentration difficulties, dizziness, headaches, phantom limb pain and chronic pain. Additionally, we recorded formal diagnoses of PTSD, major depressive disorder (MDD), generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), adjustment disorder and panic disorder, as well as the time to diagnosis postinjury. Treatment by a psychologist or psychiatrist and the need for medications to address these sequelae were also recorded, with rates defined as the proportion of patients requiring these management modalities.

Patients with work-related EIs had information recorded regarding RTW goals: time required to return to preinjury employment or alternative work in the labour market and the form of workplace accommodations (ie, modified scheduling or duties). Patients who did not have documented outcomes regarding their RTW status were excluded from this analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Active patient and public involvement was not incorporated into this study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics V.25.0. Categorical variables are presented as percentages, with group comparisons made using Fisher’s exact test. Normally distributed continuous variables are presented as mean and SD, and compared between groups using the Student’s t-test. Non-parametric data are presented as median and IQR, and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. For all comparisons, p≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Acute period

We identified 207 acute EI admissions between 1998 and 2015 that were eligible for inclusion (online supplementary figure 2). Of these acute patients, 106 were discharged to either inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation at any rehabilitation facility, and therefore had neuropsychological assessment data available for review. Four patients were excluded due to pre-existing psychiatric conditions that were documented on admission in their hospital records. SJRH records were obtained for 59 of these patients who were identified as having received inpatient or outpatient treatment at this facility without a pre-existing psychiatric condition. Health records for patients who were admitted to SJRH prior to the year 2003 were not accessible, therefore, these patients were not included in further analysis.

Demographics

Patients were predominantly male with a mean age of 41±13 years. Median burn size was 4 (1–10) %TBSA and the incidence of inhalation injury was 2%. LVIs were more common than HVIs (59% vs 37%), and the voltage was unspecified for nine patients. The most prevalent mechanism of EI was isolated flash injury, followed by direct contact with electrical current. The majority of injuries were work-related (83%; table 1, online supplementary table 1).

Clinical outcomes

The median LOS and LOS/%TBSA were 9 (3–18) days and 2 (1–4) days/% burn, respectively. Two per cent of patients did not survive to discharge, with coroner reports identifying the following causes: anoxia, ARDS and SIRS, sepsis, and massive burns. (table 1, online supplementary figure 3). The most common complications during acute management were infection, amputation and compartment syndrome. Multiple organ failure occurred in fewer than 1% of patients. While 13% of patients required at least one amputation, 6% required multiple. The most common amputation sites were the digits of the feet and the digits of the hands (36% and 29%, respectively), while the least common was above the elbow (2%). Overall, half of all EI patients required rehabilitation on discharge; of these, 32% and 68% were referred to inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation, respectively (table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical outcomes during the acute phase of management

| All patients* | HVI | LVI | P value | |

| No of patients | 207 | 76 | 122 | |

| LOS, days, median (IQR) | 9 (3–18) | 14 (4–24) | 8 (3–15) | <0.001 |

| LOS/TBSA, days/%, median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) | 3 (1–8) | 2 (1–3) | <0.001 |

| TBSA, %, median (IQR) | 4 (1–10) | 3 (1–15) | 5 (2–9) | 0.44 |

| No of ORs, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | 2 (0–3) | 0 (0–1) | <0.001 |

| Complications, no (%) | ||||

| Rhabdomyolysis | 9 (4) | 9 (12) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Compartment syndrome | 17 (8) | 12 (16) | 5 (4) | 0.007 |

| Infection | 28 (14) | 15 (20) | 11 (9) | 0.05 |

| Sepsis | 11 (5) | 8 (11) | 3 (2) | 0.02 |

| Multiple organ failure | 1 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.38 |

| Amputation | 26 (13) | 21 (28) | 3 (2) | <0.001 |

| Multiple amputations | 13 (6) | 10 (13) | 2 (2) | 0.001 |

| Requiring rehabilitation, no. (%) | 106 (51) | 49 (64) | 54 (44) | 0.008 |

| Discharged to inpatient rehabilitation, no (%)† | 34 (32) | 22 (45) | 10 (19) | 0.005 |

| Discharged to outpatient rehabilitation, no (%)† | 72 (68) | 27 (55) | 44 (81) | 0.005 |

| Mortality, no (%) | 4 (2) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 0.16 |

*Includes patients whose voltage was not otherwise specified (n=9).

†Percentages are calculated based on the total number of patients requiring any form of rehabilitation (all patients, n=106; HVI, n=49; LVI, n=54).

HVI, high-voltage injury; LOS, length of stay; LVI, low-voltage injury; TBSA, total body surface area.

Neuropsychological outcomes

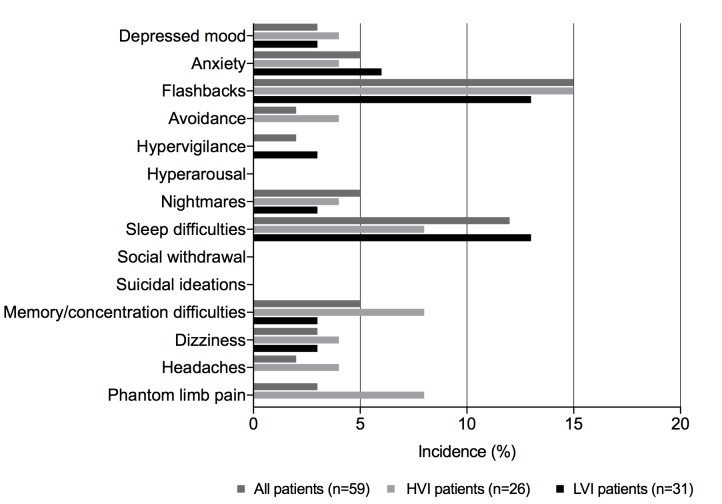

Of the 59 patients with neuropsychological screening, nearly one quarter experienced at least one neuropsychological symptom during the acute period (table 2). The most common symptoms included flashbacks (15%) and sleep difficulties (12%). Suicidal ideations, hyperarousal and social withdrawal did not occur during the acute phase of treatment (figure 1).

Table 2.

Neuropsychological sequelae and management

| All patients* | HVI | LVI | P value | |

| Acute cohort | ||||

| No of patients | 59 | 26 | 31 | |

| Neuropsychological sequelae, no (%) | 14 (24) | 6 (23) | 7 (23) | >0.99 |

| Long-term cohort | ||||

| No of patients | 122 | 51 | 69 | |

| Days to first follow-up, median (IQR)† | 201 (68–766) | 504 (179–1236) | 124 (41–233) | <0.001 |

| Days to last follow-up, median (IQR)† | 980 (391–1409) | 1099 (511–1651) | 773 (315–1218) | 0.02 |

| Neuropsychological sequelae, no (%) | ||||

| <5 years postinjury | 99 (81) | 42 (82) | 56 (81) | >0.99 |

| >5 years postinjury‡ | 20 (27) | 13 (35) | 7 (20) | 0.19 |

| Psychological/ psychiatric treatment, no (%) |

78 (64) | 31 (61) | 47 (68) | 0.44 |

| Medication, no (%) | 78 (64) | 30 (59) | 47 (68) | 0.34 |

Analysis excludes patients with documented pre-existing psychiatric conditions.

*Includes patients whose voltage was not otherwise specified (acute cohort, n=2; long-term cohort, n=2).

†Calculated from the date of injury.

‡Percentages are calculated based on the total number of patients that were available for follow-up at >5 years postinjury (all patients, n=74; HVI, n=37; LVI, n=35).

HVI, high-voltage injury; LVI, low-voltage injury.

Figure 1.

Neuropsychological symptoms of electrical injury patients during the acute phase of treatment. HVI, high-voltage injury; LVI, low-voltage injury.

Acute period, high-voltage versus low-voltage injuries

Demographics

The acute cohort was composed of 76 HVI and 122 LVI patients, with both groups being predominantly male. Both voltage cohorts were similar in mean age, median %TBSA and incidence of inhalation injury. LVIs were more likely of being occupational in nature (p=0.03). HVIs were more frequently a result of combined flash and contact burn aetiology, while LVIs were more commonly associated with isolated flash injuries (p<0.001 for both; online supplementary table 1).

Clinical outcomes

The incidence and severity of clinical outcomes were overall worse in the HVI group. HVI patients experienced a longer LOS (p<0.001) and LOS/%TBSA (p<0.001), and greater incidences of rhabdomyolysis (p<0.001), compartment syndrome (p=0.007), infections (p=0.05), sepsis (p=0.02; table 1) and operations (p<0.001). However, there was no statistical difference in survival between HVIs and LVIs (table 1, online supplementary figure 3). Single and multiple amputations were more common among HVI patients (p<0.001 and p=0.001, respectively). The majority of HVI amputations involved digits (29% hands, 36% feet). Finally, patients with HVIs were more frequently discharged to inpatient rehabilitation relative to LVIs (p=0.005), while initial outpatient rehabilitation was more common in the LVI group (p=0.005; table 1).

Neuropsychological outcomes

Of those screened, HVIs and LVIs were equally as likely of experiencing neuropsychological sequelae during the acute treatment period (p>0.99; table 2). Likewise, there was no significant difference in the incidence of symptoms between voltage groups. Marginally greater rates of the following symptoms were exhibited by the HVI group when contrasted with the LVI group: depressed mood (4% vs 3%, p>0.99), flashbacks (15% vs 13%, p>0.99), dizziness (4% vs 3%, p>0.99), nightmares (4% vs 3%, p>0.99), avoidance (4% vs 0%, p=0.46), memory and concentration impairments (8% vs 3%, p=0.59), headaches (4% vs 0%, p=0.46) and phantom limb pain (8% vs 0%, p=0.20). In contrast, LVIs were associated with slightly greater rates of sleep difficulties (13% vs 8%, p=0.68), anxiety (6% vs 4%, p>0.99) and hypervigilance (3% vs 0%, p>0.99; figure 1).

Long-term period

Demographics

The long-term cohort consisted of 128 patients, with a second screen identifying six patients meeting exclusion criteria due to pre-existing psychiatric conditions. Therefore, 122 patients were available for analysis. Half of these patients had been treated for their acute injury at RTBC, therefore, acute data were available for those patients. The majority of patients in the long-term cohort suffered EIs that were occupational in nature (91%, online supplementary table 2).

Neuropsychological outcomes

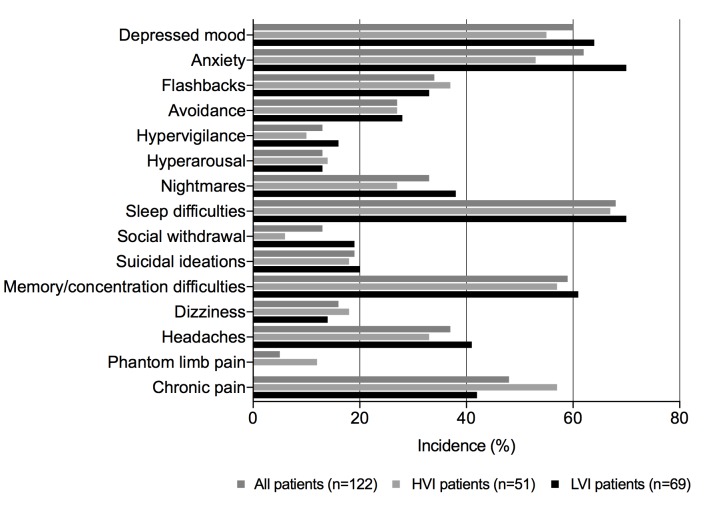

More than half of all patients receiving rehabilitation were diagnosed with at least one psychiatric disorder after their injury, while one-third of patients were diagnosed with two or more. The median time to a psychiatric diagnosis from the date of injury across all six conditions was 315 (117–957) days (online supplementary table 3). PTSD (33%), MDD (25%) and adjustment disorder (20%) were the conditions that occurred most frequently (online supplementary figure 4). Additionally, 81% of the long-term cohort experienced at least one neuropsychological symptom between a median time to first and last follow-up of 201 (68–766) and 980 (391–1409) days postinjury, respectively (table 2). The most common symptoms were sleep difficulties (68%), anxiety (62%), depressed mood (60%) and memory and concentration impairments (59%) (figure 2). More than 60% of the long-term patient cohort exhibited symptoms that were severe enough to warrant psychological/psychiatric treatment or medication. Patients with PTSD most commonly exhibited symptoms of anxiety, sleep difficulties and depressed mood (95%, 93% and 85%, respectively). MDD, GAD and adjustment disorder were frequently associated with symptoms of depressed mood, anxiety, sleep difficulties and memory and concentration impairments (online supplementary table 4).

Figure 2.

Neuropsychological symptoms of electrical injury patients during the long-term phase of treatment. HVI, high-voltage injury; LVI, low-voltage injury.

RTW outcomes

A total of 111 work-related EIs were reviewed; of these, data regarding RTW status were recorded for 90 patients. Electricians made up the predominant occupation group, followed by powerline technicians (online supplementary table 2). Sixty-one per cent of patients were able to return to their preinjury occupation, of which 60% required modified duties and 55% required modified scheduling. Furthermore, 19% of patients sustaining work-related EIs returned to alternative employment through labour market re-entry (LMR), with the median time for returning to any work being 166 (82–414) days from the time of injury. Overall, one-fifth of EI patients were unable to return to any form of employment (table 3).

Table 3.

Return-to-work characteristics of occupational electrical injuries within the long-term cohort

| All patients* | HVI | LVI | P value | |

| No of patients | 90 | 39 | 49 | |

| Return to preinjury occupation, no (%) | 55 (61) | 23 (59) | 30 (61) | >0.99 |

| Modified duties, no (%)† | 33 (60) | 15 (65) | 17 (57) | 0.58 |

| Modified schedule, no (%)† | 30 (55) | 11 (48) | 17 (57) | 0.59 |

| Labour market re-entry, no (%) | 17 (19) | 9 (23) | 8 (16) | 0.80 |

| Time to RTW, days, median (IQR)‡ | 166 (82–414) | 207 (102–548) | 124 (57–348) | 0.12 |

| Unable to RTW, no (%) | 17 (19) | 6 (15) | 11 (22) | 0.43 |

*Includes patients whose voltage was not otherwise specified (n=2).

†Percentages are calculated based on the total number of patients that returned to their preinjury occupation (all patients, n=55; HVI, n=23; LVI, n=30).

‡Calculated from the date of injury.

HVI, high-voltage injury; LVI, low-voltage injury; RTW, return-to-work.

Long-term period, high-voltage versus low-voltage injuries

Neuropsychological outcomes

The distribution of formal diagnoses of individual psychiatric disorders was comparable between HVIs and LVIs (online supplementary figure 4). PTSD and MDD were the most common in both voltage groups (24% vs 41%, p=0.054 and 18% vs 30%, p=0.14, respectively), while panic disorder was the most infrequently diagnosed (0% and 1%, p>0.99). HVIs were most commonly associated with sleep difficulties (67%), memory and concentration impairment (57%) and chronic pain (57%), while LVIs were most commonly associated with sleep difficulties (70%) and anxiety (70%) (figure 2). LVIs exhibited slightly greater rates of depressed mood (64% vs 55%, p=0.35), anxiety (70% vs 53%, p=0.09), nightmares (38% vs 27%, p=0.33), headaches (41% vs 33%, p=0.45) and hypervigilance (16% vs 10%, p=0.42), however, these differences were not statistically significant. HVIs were more likely to exhibit neuropsychological sequelae beyond 5 years postinjury (p=0.05; table 2). Additionally, our LVI cohort experienced greater requirements for management, including medications and psychological/psychiatric treatment, of these symptoms and conditions (p>0.05).

RTW outcomes

LVIs and HVIs had similar rates of return to preinjury occupation. More than half of these patients required workplace accommodation. HVI patients more frequently required modified duties, while LVIs were more commonly associated with modified scheduling. The requirement for LMR for alternative employment was similar between voltage groups, along with the median time for RTW. A comparable inability to return to any form of employment was observed between voltage groups (table 3).

Discussion

Our study identifies and delineates common sequelae that extend beyond acute management. When stratifying by voltage, the acute clinical findings indicate greater rates of complications and operative interventions in the HVI group. Conversely, rates of neuropsychological symptoms in both groups increase overtime during the first 5 years postinjury, after which rates appear to decline. While overall neuropsychological sequelae are statistically comparable between voltage groups, LVIs result in marginally greater rates of depressed mood, anxiety, nightmares, headaches and hypervigilance. They have similarly been associated with greater rates of PTSD, MDD, GAD, adjustment disorder and panic disorder. Finally, both voltage groups are implicated in RTW challenges. HVIs result in marginally more frequent job accommodations and retraining, while LVIs are associated with slightly greater rates of unsuccessful RTW. However, these results are not statistically significant. Therefore, while HVIs result in increased clinical morbidity, LVIs need to be recognised as significant burdens for their effects on neuropsychological and social well-being.

Acute clinical findings are consistent with other studies that have shown increased morbidity in patients who have sustained a HVI.19–25 A recent systematic review evaluated the different injury patterns associated with HVIs and LVIs, with combined data identifying longer hospital stays and greater complication rates with higher voltage.19–21 Comparative data between voltage groups for other common complications implicated in EIs, such as compartment syndrome, rhabdomyolysis and amputations, are lacking in literature.26–28 However, histological and gross structural modifications, along with subsequent muscle and vasculature destruction, have been observed with increasing voltage.29 This further suggests that HVIs may result in increased complication rates, morbidity and mortality.28–33

Hussmann et al observed greater rates of neurological impairments in their EI patient cohort, over a mean follow-up time of 5 years.6 This suggests that our findings may underestimate the true severity of EIs, as continued care beyond 5 years was uncommon in our long-term cohort. Nevertheless, our findings are consistent with other studies that have evaluated the implications of EIs on behaviour and cognitive function.5 6 8–10 14–16 34 Common difficulties identified during recovery include flashbacks, nightmares, MDD and PTSD. The findings of these studies highlight the need for further exploration of neuropsychological sequelae in this burn population. In doing so, we will improve the understanding of specific predispositions post-EI, facilitating symptom monitoring and management.

Current literature regarding neuropsychological sequelae suggests that burn survivors exhibit greater rates of psychiatric illnesses compared to the general population. Meyer et al investigated the prevalence of diagnoses in young adults who had sustained a burn injury of any aetiology prior to the age of 16.35 Relative to our EI cohort, a lower rate of PTSD and greater incidences of MDD and GAD were reported. However, the follow-up time postinjury is greater than that of our study, which may result in an underestimation of diagnosis rates within our cohort. Additionally, differences in cohort characteristics exist, with the mean age of our patient population being twice as high, and a significantly greater representation of males than females. Overall, comparison of our findings to current evidence indicates that EI patients may be more predisposed to certain psychiatric conditions relative to the general burn population.

Finally, our results demonstrate the challenges that EIs elicit with employment reintegration. Noble et al found that a third of their EI cohort was unable to return to any employment.5 In contrast, we observed a lower inability to RTW in both voltage groups. This may indicate improved strategies in EI management and more specialised rehabilitation programmes that enhance work reintegration. However, workplace accommodations remain common among this burn population and should be an area of focus during rehabilitation.

This study provides a regional view into the truly global burden of this burn injury. A recent review of adult EIs identified a total of 41 publications globally in this area of research. Nearly half of all studies originated from outside of North American and did not independently evaluate HVI and LVI outcomes. These studies limited investigations to clinical-based outcomes without addressing rehabilitation and psychological impacts.19 Therefore, to our knowledge, our study is the most comprehensive acute and long-term investigation of EIs to date, providing caregivers with an in-depth understanding of the acute and long-term barriers faced by this burn population. These findings additionally highlight the need for employee safety education and postinjury monitoring for common sequelae with any voltage.17 Additionally, specialised care centres should manage this patient population early on in treatment, with immediate involvement of mental health experts. Overall, the formulation of holistic EI teams (ie, psychologists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, pain specialists, RTW coordinators) may facilitate reintegration to original employment and improve patient outcomes.

Several limitations have been recognised. Data from the acute period were extracted from a single regional burn centre. Therefore, our cohorts consist of patients believed to be more injured than other EI patients, requiring specialised treatment. Long-term data are limited to patients who received rehabilitation services at SJRH. Patients may have sought treatment within their community, limiting identification of more long-term sequelae. Due to this loss to follow-up, our results may underrepresent the long-term neuropsychological and RTW effects of EIs. Furthermore, our study did not incorporate a control group, limiting our ability of identifying definitive causal relationships between EIs and neuropsychological sequelae. Finally, LOS/%TBSA is a commonly used parameter in burns, however, it is not as reflective of EI-associated damage, as the effects on underlying tissues are profound but not accounted for in %TBSA. Therefore, it has served as a minor outcome measure for this study.

In conclusion, EIs are implicated in multifaceted clinical, neuropsychological and social sequelae. Effects exist acutely and long-term, warranting monitoring that extends beyond initial treatment. LVIs are, at minimum, as likely as HVIs of exhibiting complications during recovery. Finally, we have identified these effects as possible barriers for successful employment reintegration. Collectively, these findings indicate a need for focused training and rehabilitation. Future investigations will involve implementing similar studies across broad geographic regions to inform region-specific management of this burn injury.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MGJ was responsible for the study design. NR was responsible for the literature search, data acquisition and drafting of the work. SR and NR conducted statistical analysis of data. NR, SAM, SR, MG and MGJ were responsible for revisions of the work. All authors gave approval for the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM087285-01); CIHR Funds (123336), CFI Leader’s Opportunity Fund (Project #25407). Additionally, this work was generously supported by Alectra, Electrical Safety Authority, Hydro One, Ontario Energy Network, Ontario Power Generation, Power Workers Union and Toronto Hydro.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of SHSC (# 075-2015).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. American Burn Association. National burn repository: 2016 report. 2016. http://ameriburn.org/education/publications/ (Accessed Jun 2017).

- 2. Mancusi-Ungaro HR, Tarbox AR, Wainwright DJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder in electric burn patients. J Burn Care Rehabil 1986;7:521–5. 10.1097/00004630-198611000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Inancsi W, Guidotti TL. Occupation-related burns: five-year experience of an urban burn center. J Occup Med 1987;29:730–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mandelcorn E, Gomez M, Cartotto RC. Work-related burn injuries in Ontario, Canada: has anything changed in the last 10 years? Burns 2003;29:469–72. 10.1016/S0305-4179(03)00063-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Noble J, Gomez M, Fish JS. Quality of life and return to work following electrical burns. Burns 2006;32:159–64. 10.1016/j.burns.2005.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hussmann J, Kucan JO, Russell RC, et al. Electrical injuries--morbidity, outcome and treatment rationale. Burns 1995;21:530–5. 10.1016/0305-4179(95)00037-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Janus TJ, Barrash J. Neurologic and neurobehavioral effects of electric and lightning injuries. J Burn Care Rehabil 1996;17:409–15. 10.1097/00004630-199609000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pliskin NH, Capelli-Schellpfeffer M, Law RT, et al. Neuropsychological symptom presentation after electrical injury. J Trauma 1998;44:709–15. 10.1097/00005373-199804000-00027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kelley KM, Tkachenko TA, Pliskin NH, et al. Life after electrical injury. Risk factors for psychiatric sequelae. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999;888:356–63. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07970.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pliskin NH, Fink J, Malina A, et al. The neuropsychological effects of electrical injury. New insights. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999;888:140–9. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07952.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Muehlberger T, Vogt PM, Munster AM. The long-term consequences of lightning injuries. Burns 2001;27:829–33. 10.1016/S0305-4179(01)00029-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Martin TA, Salvatore NF, Johnstone B. Cognitive decline over time following electrical injury. Brain Inj 2003;17:817–23. 10.1080/0269905031000088604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pliskin NH, Ammar AN, Fink JW, et al. Neuropsychological changes following electrical injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2006;12:17–23. 10.1017/S1355617706060061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ramati A, Rubin LH, Wicklund A, et al. Psychiatric morbidity following electrical injury and its effects on cognitive functioning. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2009;31:360–6. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chudasama S, Goverman J, Donaldson JH, et al. Does voltage predict return to work and neuropsychiatric sequelae following electrical burn injury? Ann Plast Surg 2010;64:522–5. 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181c1ff31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Piotrowski A, Fillet AM, Perez P, et al. Outcome of occupational electrical injuries among French electric company workers: a retrospective report of 311 cases, 1996-2005. Burns 2014;40:480–8. 10.1016/j.burns.2013.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Waldmann V, Narayanan K, Combes N, et al. Electrical cardiac injuries: current concepts and management. Eur Heart J 2018;39:1459–65. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. International Electrotechnical Commission. International standard: IEC standard voltages. IEC 60038:1983+A1:1994+A2. 1997.

- 19. Shih JG, Shahrokhi S, Jeschke MG. Review of adult electrical burn injury outcomes worldwide: an analysis of low-voltage vs high-voltage electrical injury. J Burn Care Res 2017;38:e293–8. 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Latifi N-A, Karimi H. Motahary Burn Hospital, School of Medicine, Burn Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Yasemi Alley, Vali Asr Ave., Tehran 19637, Iran. Acute electrical injury: a systematic review. Journal of Acute Disease 2017;6:93–6. 10.12980/jad.6.2017JADWEB-2016-0055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Karimi H, Momeni M, Vasigh M. Long term outcome and follow up of electrical injury. Journal of Acute Disease 2015;4:107–11. 10.1016/S2221-6189(15)30018-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grube BJ, Heimbach DM, Engrav LH, et al. Neurologic consequences of electrical burns. J Trauma 1990;30:254–8. 10.1097/00005373-199003000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Luz DP, Millan LS, Alessi MS, et al. Electrical burns: a retrospective analysis across a 5-year period. Burns 2009;35:1015–9. 10.1016/j.burns.2009.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gündüz T, Elçioğlu O, Cetin C. Intensity and localization of trauma in non-fatal electrical injuries. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2010;16:237–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Karadaş S, Gönüllü H, Oncü MR, et al. [The effects on complications and myopathy of different voltages in electrical injuries]. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2011;17:349–53. 10.5505/tjtes.2011.15483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holliman CJ, Saffle JR, Kravitz M, et al. Early surgical decompression in the management of electrical injuries. Am J Surg 1982;144:733–9. 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90560-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. American College of Surgeons. Advanced trauma life support program for physicians, Student and Instructor Manual. Chicago: American College of Surgeons, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Price TG, Cooper MA. Electrical and lightning injuries : Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: concepts and clinical practice. 8th edn Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Waldmann V, Narayanan K, Combes N, et al. Electrical injury. BMJ 2017;357:j1418 10.1136/bmj.j1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jaffe RH. Electropathology: a review of the pathologic changes produced by electric currents. Arch Pathol 1928;5:839. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kobernick M. Electrical injuries: pathophysiology and emergency management. Ann Emerg Med 1982;11:633–8. 10.1016/S0196-0644(82)80211-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Püschel K, Brinkmann B, Lieske K. Ultrastructural alterations of skeletal muscles after electric shock. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 1985;6:296–300. 10.1097/00000433-198512000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bongard O, Fagrell B. Delayed arterial thrombosis following an apparently trivial low-voltage electric injury. Vasa 1989;18:162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rosenberg M, Mehta N, Rosenberg L, et al. Immediate and long-term psychological problems for survivors of severe pediatric electrical injury. Burns 2015;41:1823–30. 10.1016/j.burns.2015.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Meyer WJ, Blakeney P, Thomas CR, et al. Prevalence of major psychiatric illness in young adults who were burned as children. Psychosom Med 2007;69:377–82. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180600a2e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-025990supp001.pdf (603KB, pdf)