Abstract

Objectives

Critical and chronic illness in youth such as diabetes can lead to impaired mental health. Despite the potentially traumatic and life-threatening nature of venous thromboembolism (VTE), the long-term mental health of adolescents and young adults with VTE is unclear. We compared the long-term mental health of adolescents and young adults with VTE versus adolescents and young adults with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) using psychotropic drug purchase as proxy for mental health.

Design

Nationwide registry-based cohort study.

Setting

Denmark 1997–2015.

Participants

All patients aged 13–33 years with an incident diagnosis of VTE (n=5065) or IDDM (n=6609).

Exposure

First time primary hospital diagnosis of VTE or IDDM.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Adjusted absolute risk and risk difference at 1 and 5 years follow-up for first psychotropic drug purchase comparing patients with VTE and patients with IDDM.

Results

The absolute 1 year risk of psychotropic drug use was 6.2% among VTE patients versus 3.6% among patients with IDDM, at 5 years this was 19.3%–14.7%, respectively. After adjusting for the effect of sex, age and risk factors for VTE this corresponded to a 1 year risk differences of 1.9% (95 % CI 0.1% to 3.3%). At 5 years follow-up the risk difference was 1.9% (95% CI 0.5% to 3.3%).

Conclusion

One-fifth of adolescents and young adults with incident VTE had claimed a prescription for a psychotropic drug within 5 years, a risk comparable to that of young patients with IDDM.

Keywords: adolescents, diabetes, embolism and thrombosis, psychology, venous thromboembolism, young adult

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study included all patients aged 13–33 years with a first-time hospital diagnosis of venous thromboembolism or insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in Denmark in 1997–2015.

The study had complete long-term follow-up on psychotropic drug purchase.

The study lacked data regarding socioeconomic position, which has been associated with increased mental health problems in these patient groups.

Finally, the study lacked data on duration of psychotropic drug use and other diseases occurring during follow-up, which may have been associated with the need for psychotropic therapy.

Introduction

Mental comorbidity is well established as a prevalent problem in young patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), with documented negative effect on disease management and prognosis.1–3 Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which include deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is not traditionally considered a chronic illness. However, 25%–50% of patients with DVT live with chronic complications in terms of post-thrombotic syndrome, and 0.4%–4.0% of patients with PE develop chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.4 Additionally, adolescents and young adults with VTE have to manage anticoagulant treatment and live with the perpetual risk of recurrent VTE, which may reach an incidence rate of 6.7 per 100 persons years among patients younger than 30 years.5 Thus, from a transition theory perspective, adolescent and young adults with VTE are likely to be similar to IDDM patients in experiencing multiple and simultaneous transitions, making them particularly vulnerable to psychosocial distress.6 In addition to the health-illness transition of VTE, the young patients will face the developmental transition of adolescence and young adulthood marked by intimacy, generativity and career consolidation, which today often continues into the early 30s.7

Younger patients with VTE have been shown to have a decreased quality of life and psychological impairment compared with the general population of same age.8 9

Similar to IDDM patients, symptoms of anxiety and depression among VTE patients have been associated with poor disease management and mortality.10 11 Thus, similar to young chronically ill patients with IDDM, the mental health of adolescents and young adults with VTE could be impaired in long term.

We hypothesised that adolescents and young adults with VTE would have a similar risk of psychotropic drug purchase as chronically ill adolescents and young adults with IDDM. In the present nationwide cohort study, we therefore compared the long-term mental health of adolescents and young adults with VTE to young patients with IDDM. To assess mental health status, we used information about psychotropic drug purchase derived from a Danish registry as a proxy for mental health.

Methods

Registry data sources

We used three nationwide Danish registries in this study12: (1)The Danish National Patient Register, which contains detailed information on 99% of all somatic hospital admissions since 1977 along with diagnoses, coded according to the International Classification of Diseases and surgical procedures coded according to the Danish version of the Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee Classification of Surgical Procedures13; (2) The Danish National Prescription Registry, which contains data on redeemed prescriptions in Denmark since 1995, coded according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System14 and (3) The Danish Civil Registration System, which holds information on gender, date of birth, death and emigration of all Danish residents.15 Data were linked using a unique civil registration number assigned to all Danish residents at birth or immigration and used in all Danish national registries.

Study population

We identified all patients aged 13–33 years with a first-time diagnosis of VTE or IDDM in the period 1 January 1997 to 31 December 2015. Patients with VTE were identified by a first-time primary hospital diagnosis of DVT or PE. If a patient had a diagnosis of both DVT and PE, preference was given to PE. Risk factors for VTE included major surgery, fracture or trauma within 90 days before the VTE diagnosis or a diagnosis of cancer, inflammatory bowel disease or rheumatoid arthritis within 1 year prior to the VTE diagnosis. Patients with IDDM were identified by a first-time hospital diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and a prescription claim for insulin within 30 days after diagnosis and no insulin prescription before 30 days prior to date of diagnosis. The index date for IDDM patients was defined as the date of first insulin prescription purchase after the diabetes diagnosis. The index date for VTE patients was based on day of VTE diagnosis and randomly shifted according to the distribution of time between diabetes diagnosis and insulin prescription purchase in the IDDM cohort. We excluded patients who had not been residents in Denmark for at least 2 years before the date of VTE or IDDM in order to ensure sufficient lookback time for diagnoses and medications, as well as patients who died on the day of diagnosis. To identify new-onset impaired mental health, we further excluded patients with prior psychiatric diagnosis (depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and addiction) and patients who had purchased psychotropic drugs (antidepressants, anxiolytics, sedatives, antipsychotics) within 2 years before the date of VTE or IDDM diagnosis. Further, we excluded patients with gestational diabetes mellitus and pregnancy-related VTE because of the distinct clinical course of pregnancy-related VTE and gestational diabetes, as well the risk of postpartum depression. Online supplementary table 1 provides information on codes used in the study.

bmjopen-2018-026159supp001.pdf (12.7KB, pdf)

Outcome

The primary endpoint was a composite endpoint of psychotropic drug purchase, as a proxy for impaired mental health, recorded in the Danish National Prescription Registry following the index date. The secondary outcome was the specific types of psychotropic drugs: antipsychotics, anxiolytics, sedatives and antidepressants.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive characteristics of the study population at date of diagnosis of VTE or IDDM were presented using means and SD for continuous measures and counts and percentages for categorical measures. Time to first psychotropic drug purchase was measured from index date. Patients were censored at the time of death, emigration or end of study (31 December 2015), whichever came first. Cumulative incidence functions (by means of the Aalen-Johansen estimator), assuming death as competing risks, were used to depict risk of psychotropic drug purchase within 10 years. We used pseudo-value regression approach with identity link function on a risk difference scale to assess the association between diagnosis type (VTE or IDDM) and the risk of a psychotropic drug purchase within 1 and 5 years taking into account the competing risk of death. The pseudo-value regression technique reduces to simple regression on the event status indicator when there is no censoring and accounts for censored observations before 1 and 5 years, respectively.16 To assess to which extent the observed association could be explained by sex, age or recent provocation, we also conducted multivariate regression of pseudovalues, adjusting for the effect of sex (binary), age (continuous) and ‘recent provocation’ (binary). We repeated the analysis with stratification according to sex, age (13–25 or 26–33 years) VTE type (DVT or PE) and VTE-status (provoked or unprovoked).

Stata/MP V.13 was used for the statistical analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not directly involved in the development of the research question and outcome measures or design of this nationwide cohort study.

Results

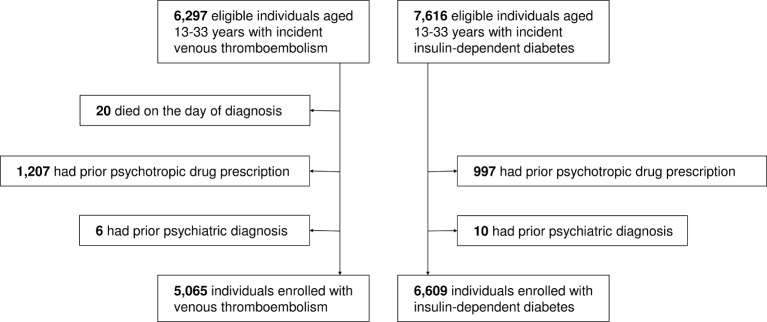

We identified 6297 patients with VTE and 7616 patients with IDDM. After exclusion of patients who died on the day of diagnosis and patients with prior psychiatric diagnoses or a psychotropic drug purchase within 2 years prior to the diagnosis, the study population comprised 5065 VTE patients, of which 76.6% had DVT and 23.4% had PE, and 6609 IDDM patients (figure 1). Patients with VTE were slightly older compared with patients with IDDM (mean age 25.7 years vs 23.7 years), and a substantially higher proportion were females (68.5% vs 38.1%) (table 1). Approximately one-fifth of patients with VTE had an underlying recorded risk factor, such as trauma (12.2%) or major surgery (12.9%). In comparison, only 4.0% of patients with IDDM had a diagnosis of trauma, and 2.4% had major surgery (table 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients included in the final study population.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics

| Variable | VTE | IDDM |

| N | 5065 | 6609 |

| Mean age (SD) | 25.7 (5.2) | 23.7 (6.5) |

| Age group, n (%) | ||

| 13–25 years | 2258 (44.6) | 3627 (54.9) |

| 26–33 years | 2807 (54.4) | 2982 (45.1) |

| Females, n (%) | 3470 (68.5) | 2516 (38.1) |

| Risk factor for VTE, yes, n (%) | 1179 (23.3) | 449 (6.8) |

| Trauma | 618 (12.2) | 267 (4.0) |

| Surgery | 652 (12.9) | 156 (2.4) |

| Cancer | 64 (1.3) | 16 (0.2) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 49 (1.0) | 26 (0.7) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 8 (0.1) | 5 (0.1) |

| DVT, n (%) | 3881 (76.6) | – |

| PE, n (%) | 1184 (23.4) | – |

DVT, deep venous thrombosis; IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

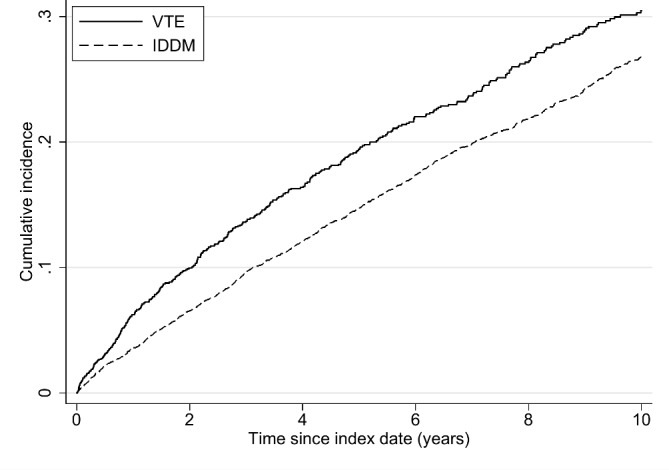

The absolute risk of psychotropic drug use among patients with VTE was 6.2% at 1 year of follow-up and 19.3% after 5 years of follow-up. The cumulative incidence curve revealed a higher risk of psychotropic drugs among patients with VTE compared with patients with IDDM (figure 2). At 1 year follow-up, the crude risk difference was 2.6% (95 % CI 1.3% to 3.9%). Extending follow-up to 5 years did not materially change this conclusion; the crude 5-year risk difference was 4.6% (95% CI 2.3% to 6.9%) (table 2). The finding of a higher psychotropic drug use among patients with VTE compared with IDDM was attenuated when adjusting for the effect of sex, age and risk factors for VTE (1 year risk difference 1.9%, 95% CI 0.1% to 3.3%; 5 year risk difference 1.9%, 95% CI 0.5% to 3.3%). Analyses stratified by sex, age, presence of provoking factors (table 2), also revealed slightly increased 5-year adjusted risk of psychotropic drug purchase among VTE patients compared with IDDM patients, though the risk differences were not statistically significant except for males in whom the long-term risk of psychotropic drugs was significantly higher among the VTE patients (table 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of psychotropic drug purchase in patients with venous thromboembolism and patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Table 2.

Risk of psychotropic drug purchase following a diagnosis of venous thromboembolism or insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in youth or adolescence

| Characteristic | 1-year follow-up | 5-year follow-up | ||||||

| Psychotropic drug purchase (%) | Unadjusted risk difference | Adjusted risk difference* | Psychotropic drug purchase (%) | Unadjusted risk difference | Adjusted risk difference* | |||

| VTE | IDDM | VTE vs IDDM (95% CI) | VTE vs IDDM (95% CI) | VTE | IDDM | VTE vs IDDM (95% CI) | VTE vs IDDM (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 6.2 | 3.6 | 2.6 (1.3 to 3.9) | 1.9 (0.1 to 3.3) | 19.3 | 14.7 | 4.6 (2.3 to 6.9) | 1.9 (0.5 to 3.3) |

| Male | 6.9 | 2.9 | 4.1 (1.8 to 6.4) | 3.0 (0.7 to 5.4) | 18.5 | 11.9 | 6.6 (2.7 to 10.4) | 3.0 (0.7 to 5.4) |

| Female | 5.9 | 4.9 | 1.0 (−0.1 to 2.7) | 0.3 (−1.5 to 2.1) | 19.7 | 19.5 | 0.2 (−2.9 to 3.4) | 0.3 (−0.2 to 2.1) |

| Age 13–25 years | 6.1 | 2.7 | 3.4 (1.5 to 5.2) | 1.7 (0.1 to 3.7) | 17.9 | 12.9 | 5.1 (1.9 to 8.3) | 1.7 (−0.4 to 3.7) |

| Age 26–33 years | 6.4 | 4.8 | 1.5 (−0.3 to 3.4) | 0.7 (−0.1 to 2.8) | 20.4 | 17.1 | 3.4 (0.1 to 6.8) | 0.7 (−0.0 to 2.8) |

| Provoked VTE | 6.3 | 3.6 | 2.4 (−0.2 to 5.0) | 1.1 (−0.2 to 3.9) | 18.8 | 14.7 | 4.1 (−0.7 to 8.9) | 1.1 (−0.6 to 3.9) |

| Unprovoked VTE | 6.0 | 3.6 | 2.7 (1.2 to 4.1) | 1.5 (−0.1 to 3.0) | 19.5 | 14.7 | 4.8 (1.6 to 6.8) | 1.5 (−0.1 to 3.0) |

| DVT | 6.1 | 3.6 | 2.6 (1.2 to 4.1) | 1.2 (−0.1 to 2.7) | 18.9 | 14.7 | 4.1 (1.2 to 4.1) | 1.2 (−0.1 to 2.7) |

| PE | 6.3 | 3.6 | 2.4 (0.1 to 5.0) | 1.0 (−0.2 to 3.6) | 20.8 | 14.7 | 6.1 (1.7 to 10.6) | 0.9 (−0.7 to 3.6) |

*Adjusted for sex, age, recent provocation (trauma, surgery, cancer, inflammatory bowel disease or rheumatoid arthritis) except when stratifying variable.

DVT, deep venous thrombosis; IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Antidepressants were the most frequently purchased drug class in both patient groups (VTE: 48%, IDDM: 58%) followed by sedatives (VTE: 24%, IDDM: 20%), anxiolytics (VTE: 19%, IDDM: 13%), antipsychotics (VTE: 5%, IDDM: 6%) and combined prescription of more than one drug class (VTE: 3% IDDM 3%). The absolute risk and risk difference comparing VTE patients and IDDM patients stratified by psychotropic drug class did not materially change the overall conclusions (data not shown).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the mental health of adolescents and young adults with VTE to that of patients receiving a diagnosis of a chronic disease such as IDDM. Our nationwide cohort study revealed that the long-term mental health of adolescents and young adults with VTE was comparable to that of IDDM patients as evidenced by a slightly higher risk of psychotropic drug use among the VTE patients, which persisted over time and was evident across strata of age and type of VTE.

Our findings extend the results from previous studies, indicating that mental health impairment does not diminish over time among VTE patients.9 17 18 Compared with IDDM patients among whom long-term comorbid mental health problems are well documented,1 3 we noted comparable psychotropic use among patients with VTE. Indeed, our study revealed that one-fifth of adolescents and young adults with VTE claim a prescription for a psychotropic drug within 5 years. This is of major concern, as it is well established that impaired mental health has an effect on outcome as well as disease management in medically ill patients.19 Accordingly, symptoms of depression and anxiety among VTE patients have been associated with both increased mortality and poor disease management.10 11 Thus, impaired mental health possibly plays an important role for disease management and long-term prognosis in a considerable number of young VTE patients as the proportion with impaired mental health was comparable to that of patients with IDDM. These findings indicate a need for further studies to prevent, or at least, to minimise psychological distress in patients with VTE.

At odds with studies from the general population, where higher levels of depression and lower quality of life are found in women than men,20 we found no difference in psychotropic drug use among men and women with VTE. This lack of gender-related differences in mental health following VTE is in accordance with prior observations of mental quality of life following VTE,21–23 and subject to further investigation.

Study limitations

Misclassification of VTE and IDDM diagnoses cannot be ruled out. Danish validation studies have previously found a positive predictive value of the VTE diagnosis of 88% to 90%,24 25 and ascertainment of diabetes mellitus by purchase of insulin in combination with a primary hospital discharge diagnosis has been shown to have a positive predictive value of 95%–97%.26 27 We defined impaired mental health by prescription purchase of psychotropic drugs but do not know whether the patients actually took the medication. However, in the present study, we infer that a prescription for a psychotropic drug would be an indication of impaired mental health. We did not assess the duration of psychotropic drug use and other diseases occurring during follow-up, which may have been associated with the need for psychotropic therapy. We also lacked data on socioeconomic factors. Low socioeconomic position has been associated with increased mental health problems, for example, higher depression rates among young patients with IDDM28 and low health related quality of life in young women with pregnancy-related DVT.29 Given these limitations, it is important to emphasise that based on this observational study we cannot infer a causal interpretation of the observed association between VTE and impaired mental health.

The major strengths of this study are the large sample size and complete coverage in the Danish hospital discharge and prescription purchase registries including all inpatient and outpatients with VTE or IDDM, which enabled a complete long-term follow-up on psychotropic drug purchases.

Conclusion

This nationwide cohort study showed that one-fifth of adolescents and young adults with incident VTE had claimed a prescription for a psychotropic drug within 5 years, indicating an impact on mental health comparable to that of young patients with IDDM.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors designed the study; AAH, LM, MS and TBL obtained and analysed the data; and all authors interpreted the data. AAH drafted the manuscript, and LM, MS, DL, SG, EES and TBL critically revised it.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: DHL has received investigator-initiated educational grants from Boehringer-Ingelheim and Bristol-Myers Squibb, served on speaker bureaus for Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer and has consulted for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim and Daiichi-Sankyo. SG has received research support from BiO2 Medical, Boehringer-Ingelheim, BMS, BTG EKOS, Daiichi, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health, Janssen, Thrombosis Research Institute and served as a consultant for Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, BMS, Daiichi, Janssen, Novartis, Portola, Zafgen. TBL has been an investigator for Janssen Scientific Affairs and Boehringer-Ingelheim, and served on speaker bureaus for AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Roche Diagnostics, Siemens Diagnostics and Takeda. Other authors: none declared.

Ethics approval: In accordance with Danish law, no ethical approval is required for non-biomedical registry studies. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (File No. 2012-41-0633).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Zoffmann V, Vistisen D, Due-Christensen M. A cross-sectional study of glycaemic control, complications and psychosocial functioning among 18- to 35-year-old adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 2014;31:493–9. 10.1111/dme.12363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DeMaso DR, Martini DR, Cahen LA, et al. Practice parameter for the psychiatric assessment and management of physically ill children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009;48:213–33. 10.1097/CHI.0b13e3181908bf4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hislop AL, Fegan PG, Schlaeppi MJ, et al. Prevalence and associations of psychological distress in young adults with Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 2008;25:91–6. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldhaber SZ, Bounameaux H. Pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis. Lancet 2012;379:1835–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61904-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martinez C, Cohen AT, Bamber L, et al. Epidemiology of first and recurrent venous thromboembolism: a population-based cohort study in patients without active cancer. Thromb Haemost 2014;112:255–63. 10.1160/TH13-09-0793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meleis AI, Sawyer LM, Im EO, et al. Experiencing transitions: an emerging middle-range theory. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 2000;23:12–28. 10.1097/00012272-200009000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sigelman CK, Rider EA. Human development across the life span. 7th edn Belmont Calif: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fiandaca D, Bucciarelli P, Martinelli I, et al. Psychological impact of thrombosis in the young. Intern Emerg Med 2006;1:119–26. 10.1007/BF02936536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Højen AA, Gorst-Rasmussen A, Lip GY, et al. Use of psychotropic drugs following venous thromboembolism in youth. A nationwide cohort study. Thromb Res 2015;135:643–7. 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Michal M, Prochaska JH, Keller K, et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety predict mortality in patients undergoing oral anticoagulation: Results from the thrombEVAL study program. Int J Cardiol 2015;187:614–9. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Michal M, Prochaska JH, Ullmann A, et al. Relevance of depression for anticoagulation management in a routine medical care setting: results from the ThrombEVAL study program. J Thromb Haemost 2014;12:2024–33. 10.1111/jth.12743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thygesen LC, Daasnes C, Thaulow I, et al. Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:12–16. 10.1177/1403494811399956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:30–3. 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kildemoes HW, Sørensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:38–41. 10.1177/1403494810394717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:22–5. 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Klein JP, Logan B, Harhoff M, et al. Analyzing survival curves at a fixed point in time. Stat Med 2007;26:4505–19. 10.1002/sim.2864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bennett P, Patterson K, Noble S. Predicting post-traumatic stress and health anxiety following a venous thrombotic embolism. J Health Psychol 2016;21:1–9. 10.1177/1359105314540965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lukas PS, Krummenacher R, Biasiutti FD, et al. Association of fatigue and psychological distress with quality of life in patients with a previous venous thromboembolic event. Thromb Haemost 2009;102:1219–26. 10.1160/TH09-05-0316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shahar G, Lassri D, Luyten P, et al. Depression in chronic physical illness The handbook of behavioral medicine. Oxford, UK: John Wiley, 2014:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Seedat S, Scott KM, Angermeyer MC, et al. Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009;66:785–95. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kahn SR, Shbaklo H, Lamping DL, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life during the 2 years following deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost 2008;6:1105–12. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03002.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kahn SR, Akaberi A, Granton JT, et al. Quality of life, dyspnea, and functional exercise capacity following a first episode of pulmonary embolism: results of the ELOPE cohort study. Am J Med 2017;130:990.e9–990.e21. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lukas PS, Neugebauer A, Schnyder S, et al. Depressive symptoms, perceived social support, and prothrombotic measures in patients with venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res 2012;130:374–80. 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sundbøll J, Adelborg K, Munch T, et al. Positive predictive value of cardiovascular diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry: a validation study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012832 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schmidt M, Cannegieter SC, Johannesdottir SA, et al. Statin use and venous thromboembolism recurrence: a combined nationwide cohort and nested case-control study. J Thromb Haemost 2014;12:1207–15. 10.1111/jth.12604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Green A, Sortsø C, Jensen PB, et al. Validation of the danish national diabetes register. Clin Epidemiol 2015;7:5–15. 10.2147/CLEP.S72768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kristensen JK, Drivsholm TB, Carstensen B, et al. [Validation of methods to identify known diabetes on the basis of health registers]. Ugeskr Laeger 2007;169:1687-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lind T, Waernbaum I, Berhan Y, et al. Socioeconomic factors, rather than diabetes mellitus per se, contribute to an excessive use of antidepressants among young adults with childhood onset type 1 diabetes mellitus: a register-based study. Diabetologia 2012;55:617–24. 10.1007/s00125-011-2405-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wik HS, Enden TR, Jacobsen AF, et al. Long-term quality of life after pregnancy-related deep vein thrombosis and the influence of socioeconomic factors and comorbidity. J Thromb Haemost 2011;9:1931–6. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026159supp001.pdf (12.7KB, pdf)