Abstract

Objectives

This study aims to identify the sources of funding for investigator-initiated clinical trials (IICTs) in Portugal, and to recommend ways to improve the quality of information collected from clinical trial databases about funding.

Design and methods

A systematic search of trial registrations over the last 13 years—using the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO-ICTRP) and four clinical trials registries (CTRs)—was carried out to identify IICTs in Portugal, used as a case study. Data from the databases were compared with data contained in publications to evaluate the consistency of information on funding sources. The term ‘database’ is used in this study to refer to both the WHO-ICTRP and the CTRs. When mentioned separately, the WHO-ICTRP is referred to as a ‘platform’, while the CTRs are referred to as ‘registries’.

Outcome

Suggestions to improve clinical trials databases to clearly identify the funding sources and data ownership in IICTs.

Results

Two hundred and eighty-two IICTs were identified in Portugal. Twenty per cent of trials were supported by industry with unclear information on the ownership of the results. Inaccuracy was found in the information about sponsors and funders. The information about funding in all resulting publications (77 out of 133 completed studies) was also inconsistent between databases in 35 out of 77 (45%) of the studies. Notably, 23% of the trials funded by non-profit organisations (n=226) received funds from international and/or national funding agencies.

Conclusions

Identification of IICT funding and ownership of results is unclear in the databases used for this study, which may lead to misunderstandings about the independence of the obtained results. Transparency and accuracy are desirable so that public decision makers and strategic partners can accurately evaluate national performance in this particular type of clinical research.

Keywords: clinical trials, interventional clinical studies, investigator-initiated clinical trials, clinical trials registry, clinical trials database

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Provides an analysis of the types of funding of investigator-initiated clinical trials (IICTs) for the first time, promoting discussion on the need for transparency.

Compares information about funding sources contained in clinical trials databases with that provided in publications.

Provides the basis for specific recommendations to increase the quality of the information provided in databases.

As a case study, data on funding sources are limited to studies initiated in Portugal. As such, the study may not be representative of other countries.

The information on IICT funding (in the databases used) is incomplete, which may provide a partial or inaccurate portrait of results.

Introduction

Investigator-initiated clinical trials (IICTs), also referred to as non-commercial, academic or independent clinical trials, are generally sponsored by non-profit organisations. IICTs can also be supported by medicine or device companies, provided that they ensure that: (1) ownership of the results belongs to the sponsor–investigator and (2) no agreement exists limiting publication or allowing the use of data for regulatory or marketing purposes by industry.1 The design, conduct, recording and reporting of the clinical trial should be under the control of the sponsor–investigator.

IICTs attempt to answer relevant questions in clinical practice that may not otherwise be addressed by industry and may provide evidence to improve therapeutic guidelines and support clinical decisions. IICTs might include trials for the paediatric use of medicines authorised for adults, or comparison of commercialised medicines. IICTs may also include pragmatic trials, and repurposing studies for novel indications for registered medicines, including in the field of rare diseases. Besides medicines, IICTs can address medical devices, nutrition, behaviour and surgery procedures to provide evidence on performance or the effect on health and well-being of participants. When compared with trials using medicines, other interventions are less demanding in terms of regulatory and ethical approvals.

In industry clinical trials, the funding source is the sponsor, whereas in non-commercial trials the sponsor might not be the funder. According to the European Regulation for clinical research (Regulation 536/2014EC), the funds for these independent clinical trials might come partly or entirely from public funds or charities2 and the sponsor is generally the organisation that receives the funds. WHO Trial Registration Data Set (TRDS) defines the primary sponsor as the individual, organisation, group or other legal entity which takes responsibility for initiating, managing and/or financing a study, and for properly registering the trial; it may or may not be the main funder. In IICTs, the sponsor has the legal capability to establish contracts with individuals (eg, principal investigator) or other stakeholders to assure the implementation and conduct of a clinical trial. When analysing all clinical trials in one database, during a specific timeframe, most of the trials testing medicines are mainly industry sponsored3 with commercial interests. On the other hand, according to the European Medicines Agency, around 40% of trials registered in Europe are IICTs mainly sponsored by academia.4

The objective of this study was to identify the main funders of IICTs in Portugal (as a case study), and to make recommendations to improve the information collected from databases on the funding sources of these trials.

Methods

We identified past or current IICTs registered and starting in one European country (Portugal) from 1 January 2004 to 31 January 2017 in order to identify the funding source. Previously, we investigated trials that are ongoing in Portugal in only one database (EU Clinical Trials Register; EU-CTR).5 In the current study, we extended the number of databases used and the type of intervention, considering the same country as a pilot.

The selection of clinical trials registries (CTRs) for this study was based on trials registered and recruiting in Portugal. We first screened the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO-ICTRP), a network platform that is directly updated by CTRs that comply with the required 24 quality-based items in the WHO-TRDS. This search enabled us to identify the presence of Portuguese trials in four of the main international registries: ClinicalTrials.gov, EU-CTR, International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry and the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR).6

Search methodology of trials in each database

Step 1

Our initial search in the WHO-ICTRP did not enable us to distinguish between commercial and non-commercial trials. Therefore, a general search was performed using the terms ‘Portugal and Interventional’ from the time period from 1 January 2004 to 31 January 2017.

Step 2

The search in the EU-CTR was performed by year (from 1 January 2004 until 31 January 2017) with the terms ‘Portugal and non-commercial’ in the general search field. The duplicates found in each year were sequentially identified and not considered for the total number.

Step 3

With the ClinicalTrials.gov registry, it was not possible to distinguish between commercial and non-commercial trials. Therefore, an advanced search was performed selecting the options ‘Portugal’ and ‘Interventional studies’, and was limited to the above-mentioned time period.

Step 4

Registrations in the BiomedCentral CTR are associated with ISRCTN. In this CTR, it was not possible to refine the search besides selecting Portugal as the recruiting country. Trials initiated before or after the selected timeframe were discarded.

Step 5

With the ANZCTR, we performed the search in the selected timeframe, using Portugal as the recruiting country. Registrations in this CTR have the initial code ACTRN.

In each of the above-mentioned search steps, all entries were manually screened, and trials sponsored by industry (ie, commercial trials) were not considered. Additionally, registrations were discarded when there were no recruiting sites in Portugal; duplications were detected (with only one of the entries conserved); trials were completed or registered before 2004; there were no patients enrolled; or no intervention was assigned (ie, observational trial) (see figure 1, Steps 1–5).

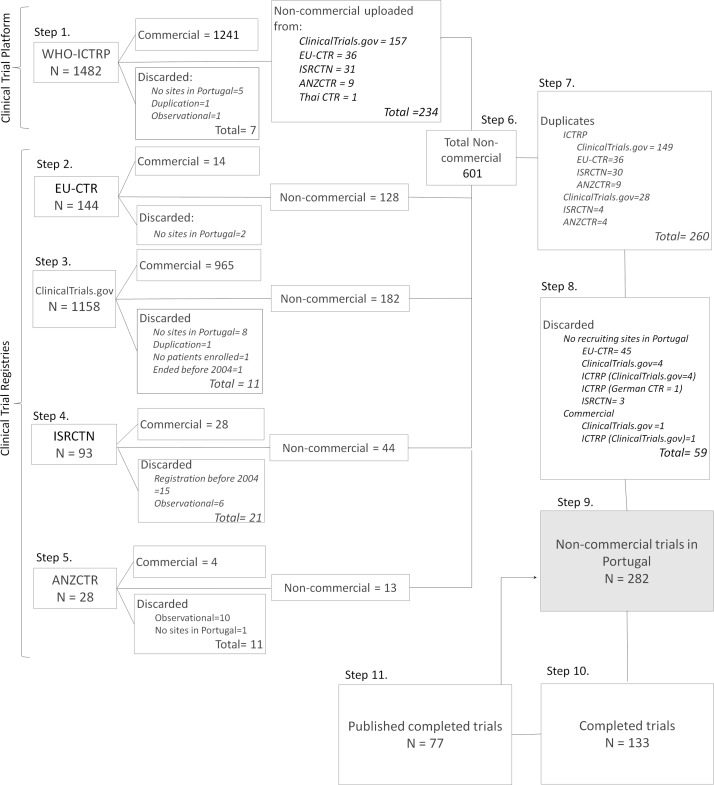

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the systematic search of non-commercial clinical trials (ie, IICTs), involving Portuguese institutions recruiting participants. The search was performed in four clinical trial registries, clinical trials registries (CTRs) (EU Clinical Trials Register [EU-CTR], Clinicaltrials.gov, International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) and Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry [ANZCTR]) and in the trial platform WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO-ICTRP). Studies starting from 1 January 2004 until 31 January 2017 were identified in each of the databases separately (Steps 1–5). After separating discarded and commercial studies, all remaining studies were gathered in one Excel sheet (Step 6). Duplicate studies (Step 7), commercial studies or studies not recruiting in Portugal (Step 8) were not considered. The final number of trials was cleaned and harmonised, and further details were collected from all the databases (Step 9), including the identification of completed studies (Step 10). Publications with results from completed studies were identified (Step 11) and used to compare the information about funding sources provided in the CTRs and the published papers (link to Step 9).

Data extraction

Step 6

Information about trial identification (Trial ID) number—main and secondary, recruitment status, sponsor name and country, and funding source—were extracted manually and independently from the registered records (from 1 February 2017 to 31 March 2017) and organised in Excel sheets. Forty per cent of the records were double-checked by two of the authors (CM and FS).

Sponsors were coded as being university, disease-specific organisation (disease associations or research institutes dedicated to a specific therapeutic area), hospital, research institute (non-specific therapeutic area), foundation and other (eg, international funding agency and private health clinic).

Funders were coded as being (1) a non-profit organisation (eg, public institution, funding agency, disease-specific organisations), (2) a for-profit organisation (ie, private company/industry), (3) both, when funding was provided by industry and non-profit organisation(s) and (4) not indicated, when the informationwas not provided. Information on funder type is indicated in the field entitled ‘sources of monetary support’ in both WHO-ICTRP and EUCTR; in the ‘sponsor and collaborators’ field in ClinicalTrials.gov; and in the ‘funder’ field in ISRCTN and ANZCTR. When only the sponsor was mentioned in the ClinicalTrials.gov registry, we considered it as the funder. Additionally, in this registry, the support of funding agencies was perceived through secondary IDs where the code of the grant agreement is in some cases added. Exclusive funding for PhD or postdoctoral grants was not considered.

Identification of duplicates and complementary information

Step 7

All trials identified as non-commercial were added to the same Excel sheet and organised by sponsor name. Duplicates were identified when secondary IDs were provided or when the sponsor and the title of the study were the same. Information obtained from different CTRs about the same study was gathered in the final record (Step 9) and used for further analysis.

Step 8

A closer look at each registration allowed the identification of more studies with no recruiting sites in Portugal as well as commercial trials.

Step 9

After removing duplicates or discarded trials, the database with the final number of registrations was organised; information about funding was gathered when more than one registration was detected in Step 7.

Search of publications of completed IICTs

Step 10

Publications from the completed IICTs were manually and independently screened. The Trial ID was used to search abstracts of journals indexed in Medline (using PubMed) as well as the four CTRs. Other publications were also found through Google search using the study title or the Trial ID. Using the name of the principal investigator, it was possible to find publications about the study, when no paper was found with the previous strategies. Surprisingly, in some publications, the Trial ID was not included in the abstract, which rendered the search more difficult.

Step 11

Information about the funding source in each publication was manually and independently retrieved and compared with the information obtained from the databases by two of the authors (CM and FS).

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor the public were involved in this study.

Results

A total of 2905 registrations were found in the four registries used (ClinicalTrials.gov, EU-CTR, ISRCTN and ANZCTR) and the WHO-ICTRP. Trials were screened to isolate those with a non-commercial sponsor, recruiting sites in Portugal and a start date between January 2004 and January 2017.

Identification of non-commercial studies

The number of trials identified in each database is shown in figure 1. After discarding industry-sponsored trials, non-interventional studies or those with no recruiting sites in Portugal, 601 non-commercial trials were considered eligible from all the screened databases. From those, 260 duplicates were identified, and 59 trials were discarded (figure 1). The main reason for the high number of discarded trials was that in the EU-CTR, the country is used as a general term. Therefore, registrations with Portugal as (1) a planned country but not yet approved by competent authorities (n=18), (2) the owner of the marketing authorisation or (3) the producer of the medicine (n=27) were also detected.

As expected, a high number of trials was retrieved from the WHO-ICTRP (n=234, figure 1, Step 1) as this platform receives weekly updates of the registrations in each of the CTRs. Of the 234 trials found in the WHO-ICTRP, 224 had also been identified at least in one of the four CTRs; as such, they were considered duplicates (Step 7, figure 1). From the 224 trials in WHO-ICTRP, seven were found to be duplicates as they were registered in different CTRs with no secondary ID, which prevented WHO-ICTRP from considering that they were the same trial (Supplementary information 1 (S.I.1) figure 1, Step 9.2—see registries marked with **). Six of the additional trials found in WHO-ICTRP were not recruiting in Portugal or were commercial in nature, and were consequently discarded (Step 8). The four additional trials that were exclusively found in the WHO-ICTRP were retained for this study (Supplementary S.I.1 figure 1, Step 9.2). Surprisingly, 59 registrations were found in the four CTRs but not in the WHO-ICTRP (Supplementary S.I.1 figure 1). This could be attributed to the methodology used for this study (eg, search terms: ‘Portugal and interventional’) as it is not possible to directly separate commercial from non-commercial trials in the platform.

bmjopen-2018-023394supp001.pdf (800.3KB, pdf)

After separating the duplicated and discarded registrations, 282 trials were further analysed; details are provided in Supplementary information 2 (S.I.2). The separation of the 282 trials registered in one, two or three CTRs (included or not in WHO-ICTRP) is shown in Supplementary S.I.1 figure 1.

bmjopen-2018-023394supp002.xlsx (67.1KB, xlsx)

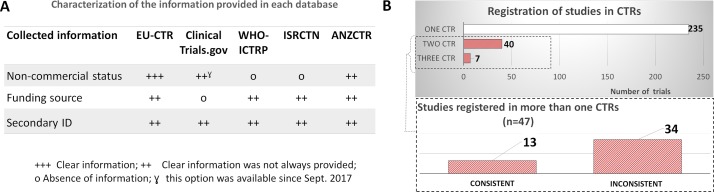

Information available in each database

In this study, we identified 282 IICTs among the nearly 3000 registrations in the four CTRs used and WHO-ICTRP. We had to manually screen the trials to distinguish between commercial trials and non-commercial trials, as this was not a systematic search option in three of them. The ability to filter this information was better with EU-CTR and ANZCTR. In ANZCTR, the search may be performed by sponsor type with eight categories; in EU-CTR, it is possible to consider the option of commercial or non-commercial study (figure 2A). Since September 2017, it has been possible to search trials according to the funder type in ClinicalTrials.gov using the option ‘All others’, which includes non-profit organisations. Other differences in the information available in each database were ranked in terms of clearness according to our user experience. The evaluation is pictured in figure 2A, which clearly shows the need for improvement in the information provided, specifically in regards to non-commercial status, funding source and secondary ID.

Figure 2.

Comparison of information about funding and secondary ID between different clinical trials registries (CTRs) and WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO-ICTRP). (A) Characterisation of information provided in each database; (+++) the information was always explicitly provided, (++) the information was not always clearly provided and incongruences were frequently found, (o) clear and direct information was not provided. (B) Number of trials registered in one or more CTRs (EU Clinical Trials Register [EU-CTR], ClinicalTrials.gov, International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number [ISRCTN], Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry [ANZCTR]). Inset: Consistency of the information about funding being provided by two or three CTRs, in the case where a study was registered in more than one CTR.

Although ISCTRN and ANZCTR have a field where the name of the funder can be added, this information is not mandatory. However, when compared with the other databases, these two clearly distinguish the sponsor from the funder with two separate fields for this purpose, and in 95%–100% of registrations the name of the funder is different from the sponsor (table 1). ClinicalTrials.gov only displays one field named ‘Sponsor and collaborators’ that is not always consistent with the information provided in the EU-CTR when the study is registered in both databases (Supplementary S.I.1 table 1). Collaborators were not indicated in 6% of registrations in ClinicalTrials.gov, and in 51% of cases (where they were indicated), the collaborator was different from the sponsor (table 1). In the other CTRs, a higher percentage of registries had the funder different from the sponsor (68%–100%). The EU-CTR has a field entitled ‘Source(s) of monetary or material support for the clinical trial’, which might be ambiguous regarding the real origin of the financial resources and ownership of the results. For example, when the name of a private company is included in this field, it is not possible to know if this company is providing either financial support, medicines, or both, and who will be the owner of the obtained results: the private company or the investigator. Additionally, in around 52% of registrations in this CTR, no information about the funder was provided (table 1).

Table 1.

Number of clinical trial registrations in each CTR, percentage of those identifying the funder as the sponsor or identifying the funder as different from the sponsor. Number of registrations with inconsistent information between the different CTRs

| Clinical trial registry | EU-CTR | ClinicalTrials.gov | ISRCTN | ANZCTN |

| Name of the field with the funder identification in each CTR | Source of Monetary or Material Support | Sponsor and Collaborators | Funder | Funder |

| Total number of registrations | 86 | 192 | 44 | 13 |

| Registration without indication of Source of Monetary Support, Collaborator or Funder* | 52% | 6% | 5% | 0% |

| Clinical trials with funder/collaborator different from the sponsor* | 68% | 51% | 95% | 100% |

| Registration with inconsistent† information (Supplementary S.I.1 table 1) | 12 out of 29 (41%) |

21 out of 33 (64%) |

1 out of 8 (13%) | 0 out of 3 (0%) |

*Percentages calculated considering the total number of registrations indicated in the first line of the table.

†Inconsistent information means that information about funding source differed (with less information) from the others CTRs used for this study.

ANZCTR, Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry; CTR, clinical trials registry; EU-CTR, EU Clinical Trials Register; ISRCTN, International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number.

The majority of the trials (n=235) were registered in only one CTR (figure 2B), but when registered in different CTRs, the information about the trial was gathered in our records. Databases have a field to add a secondary ID but the information is not always provided (figure 2A) and only 12 out of 47 trials registered in more than 1 CTR include the secondary ID (see Supplementary S.I.1 table 2). The absence of secondary ID for the same trial gave rise to different records in the WHO-ICTRP (resulting in separate entries or duplicates).

Only 28% of trials registered in more than one CTR (13 out of 47) had consistent information about funding (inset of figure 2B) highest percentage (64%) of inconsistencies was detected when trials were registered in both ClinicalTrials.gov and other CTR(s) (table 1). Inconsistencies may arise due to limitations in the fields provided by the registries; in ClinicalTrials.gov, it is not possible to distinguish funders from collaborators (as this is a single field). However, collaborators might not necessarily be funders. This is the case, for instance, with trials funded by the European Commission (eg, NCT01802814), where collaborators are considered the beneficiaries of the EU-funded project.

Funders of non-commercial trials in Portugal

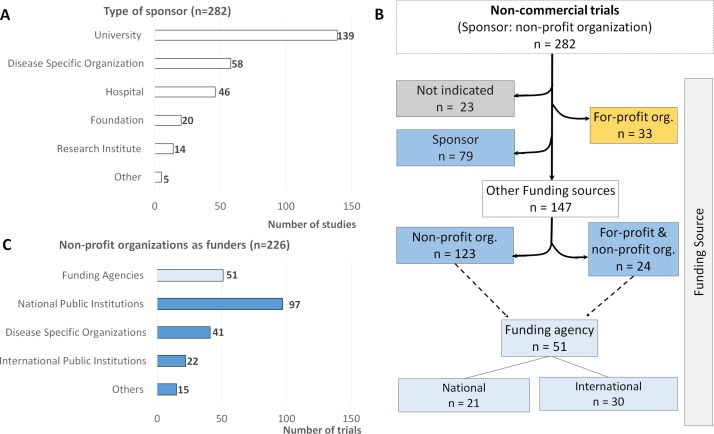

The analysis of sponsor organisation type showed that universities (n=139), disease-specific organisations (n=58) and hospitals (n=46) are the most frequent sponsors of non-commercial trials (figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Number of trials according to the type of sponsor (A), type of funding source (B) and type of non-profit organisation as funder (C). The category ‘Other’ in (A) includes a dental clinic and the National Health & Medical Research Council in Australia; and in (C) the category ‘Other’ includes foundations, private universities, clinics or health institutions.

Industry was identified as the unique funding source in 33 trials, while 24 studies were funded both by industry and non-profit organisations. It was not possible to identify the funder in 23 registered trials and the sponsor was considered as the funder in 79 registrations (mainly from ClinicalTrials.gov). In the end, 123 trials received funds exclusively from non-profit organisations. A more detailed analysis showed that a total of 51 trials received monetary support from national and international funding agencies (figure 3B).

Among non-profit organisations, funding agencies are providing monetary support to 51 trials (23%), alone or together with other non-profit organisations (figure 3C). These trials are being funded by international funding agencies such as the European Commission, the British Medical Research Council and Spanish Carlos III Institute of Health, or by the national funding agency in Portugal: Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT).

Consistency of information provided in databases and publications about funding of non-commercial trials

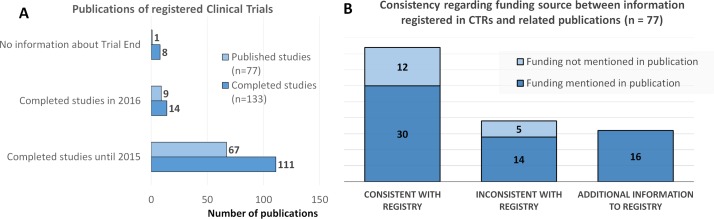

In this study, we identified that a total of 133 trials, corresponding to 47% of the total number of trials, were completed (figure 4A). Only 77 of these trials have already been published. If, however, we consider trials completed by 2015, the percentage of trials published increases to 60% (67 out of 111); this takes into account the 2 year, poststudy timeframe before publication.

Figure 4.

Completed clinical trials. (A) Comparison between the number of completed investigator-initiated clinical trials (n=133) and those that were published (n=77); (B) comparison of the information about funding source collected from publications with the information provided in the relevant database(s).

Information about the funding source was screened in each publication, showing that 78% (60 out of 77) of these publications referred to the source of funds (figure 4B). Additionally, in 55% of the trials, the information collected from the databases was consistent with the information provided in publications (even when no funding was mentioned in both), whereas in 20% of the trials, the publication provided additional information. However, in 25% of the trials (19 out of 77), the publication provided a funding source different from that indicated in the databases (figure 4B).

Discussion

In this study, a systematic analysis of IICTs registered in four CTRs and also in WHO-ICTRP was conducted with the main goal of understanding how these trials are funded in Portugal, used as a case study. The search was not straightforward and several incongruences were found after a laborious and time-consuming process of screening each of the 282 registered non-commercial clinical trials.

Several IICTs (16%; n=47) were registered in different CTRs but secondary IDs were not always provided (Supplementary S.I.1 table 2). Surprisingly, for the same study, information about funding was not consistent in 72% of cases (or 34 out of 47) when trials were registered in more than one CTR (figure 2B and Supplementary table 1). Higher numbers of inconsistencies were found in registrations in ClinicalTrials.gov when compared with the other CTRs (table 1). Even WHO-ICTRP, as previously indicated by others, does not reliably identify trials listed in multiple CTRs, making manual searches necessary.7 8 We cannot explain the fact that some registrations in the screened CTRs were not detected in the WHO-ICTRP search, even though it was a broad search. Moreover, it is also not possible to explain why some registrations found in the CTRs were still not identified in the WHO-ICTRP when the ID number was searched directly (eg, NCT01280929, NCT01281098, NCT00189553, NCT00561054).

Raftery et al showed the number of UK non-commercial trials registered by funding source from 1990 to 2009 and emphasised the fact that the trials registered in Clinicaltrials.gov had an unknown funding source.9 Our findings are fully in line with these authors’ views and herein we reiterate the need to improve the information about the funding source and the ownership of the results in Clinicaltrials.gov. We believe that this is a way to increase the quality of records and the transparency of results of non-commercial trials. The inclusion of the funding source in Clinicaltrials.gov was one of the requirements for the Proposed Rule by Title VIII of the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 200710 and it is mandatory in the TRDS for CTRs that provide information to the WHO-ICTRP. Nevertheless, to date, the clear identification of the funders and independence of results from commercial interests have not been considered as criteria when discussing the need for improvement of the available databases.

Inconsistencies were also found when comparing information about funding sources in CTRs and publications of completed IICTs. Publications are not necessarily listed on trial registries, requiring an extensive manual effort to identify them. In 45% (35 out of 77) of the publications on completed IICTs (figure 4B), the information provided is not consistent with the CTR: a different funding source is referred to and/or additional information is provided. Although some journals already require the full disclosure of funders and their input on the study, a harmonisation of editorial policies concerning this issue should be implemented by all publishers, because in some journals, funding is not even mentioned. In the publication of IICTs, mainly those using medicines or medical devices, a statement of the independence of researchers from industry funders should be mandatory.

In Portugal, although 18% of IICTs (51 out of 282) are being funded by funding agencies, 35% of trials are funded by a national public institution (mainly universities, see figure 3). On the other hand, 20% (57 out of 282) of IICTs have received support from the industry (figure 3B). Even though this support could be money or other type, when the study is funded or supported by a pharmaceutical company it is not clear who will be the owner of the obtained results. If the owner is the private company, the study should not be labelled as an IICT. Currently, through the screened databases, it is not possible to confirm if the ownership of the results belongs to the investigators when the funder is a pharmaceutical company. As suggested by others, public CTRs should ensure adequate monitoring of trial registrations; this would ensure completion of mandatory contact information fields identifying scientific leadership to promote accountability and transparency in clinical trial research.11 In some cases, information about scientific leadershipis only clear when the results are published in scientific journals in which the ownership of the trial design and results is claimed by the clinical investigators involved in the study.12 It would be important to add this information in the registration phase to ensure that questions over funding do not have a negative effect on the use of IICTfindings on the definition of new public health policies and implementation of new therapeutic approaches.

In this study, a systematic analysis of the information provided by the sponsor about the funding source is presented for the first time in order to clearly identify IICTs. When searching the five databases, we faced several limitations and suggest the following strategies for improving the accuracy of clinical trial databases (table 2).

Table 2.

Limitations and recommendations for improving accuracy of clinical trial databases

| Current limitations in the use of databases (CTRs and WHO-ICTRP) for identifying non-commercial trials | Suggested strategies for improvement |

| The identification of non-commercial trials in registries is a laborious and time-consuming task | Create a field in these databases allowing the separation of these trials from commercial trials, following the example of EU-CTR |

| Registration of the same study in different databases provide different information about the funding source (table 1) | Make it a registration requirement in all databases to provide information about the (i) funding source, (ii) the role of the investigator and the funder in the design of the study and (iii) the ownership of the results |

| When industry is the funder it is not possible to have information about the ownership of the results, unless the study is published | |

| With WHO-ICTRP some trials registered in different CTRs are not identified as duplicates7 8 | Improve this platform for detection of duplicates using not only the secondary ID but also the title of the study and the name of the sponsor |

CRTs, clinical trials registries; EU-CTR, EU Clinical Trials Register; WHO-ICRP, WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform.

National competent authorities and/or Ethics Committees might also have a contribution to make to increase transparency in IICTs. This could be achieved by making it mandatory to fully complete the registration of the study before it is approved, including information about the funder and ownership of results.

Conclusions

Although major progress has been made in recent years regarding clinical trial registration, we show here that the most frequently used CTRs are still lacking in completeness and consistency of information. In addition, the process of distinguishing commercial clinical trials from IICTs is not straightforward. Simplifying the identification process of IICTs through the databases would facilitate a direct and clear comparison of performance in each country in terms of the quality of the trials; it would also help to identify the possible funding sources available to investigators.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sabrina Gaber (European Clinical Research Infrastructure Network) for English editing and Joana Batuca (Nova Medical School) for the critical revision of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: ECM and CM conceived and designed the study. CM and FS carried out the search of the registrations and publications independently. Both CM and FS double checked 40% of the information gathered in the registrations and publications. All authors analysed and interpreted data, and drafted and performed a critical review of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or nonprofit sectors. CM and FS were supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT, through the membership fees to ECRIN-ERIC published at Portaria n 237/2014).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All collect registrations (from each database) are available from the corresponding author on request. Details about the analyzed trials are available as Supplementary Information 2 (S.I.2).

Collaborators: Sabrina Gaber; Joana Batuca.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Sabrina Gaber and Joana Batuca

References

- 1. Ross S, Magee L, Walker M, et al. Protecting intellectual property associated with Canadian academic clinical trials--approaches and impact. Trials 2012;13:1–7. 10.1186/1745-6215-13-243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Regulation (EU) Nº 536/2014 of the council parliament and of the council of 16 April 2014 on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use, and replacing Directive 2001/20/EC. https://ec.europa.eu/health/human-use/clinical-trials/regulation

- 3. Roumiantseva D, Carini S, Sim I, et al. Sponsorship and design characteristics of trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov. Contemp Clin Trials 2013;34:348–55. 10.1016/j.cct.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. European Medicines Agency (EMA) Clinical Trials in Human Medicines. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/clinical-trials-human-medicines (Accessed 18 Oct 2018).

- 5. Madeira C, Pais A, Kubiak C, et al. Investigator-initiated clinical trials conducted by the Portuguese Clinical Research Infrastructure Network (PtCRIN). Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2016;4:141–8. 10.1016/j.conctc.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zarin DA, Tse T, Williams RJ, et al. Update on trial registration 11 years after the ICMJE policy was established. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2017;376:383–91. 10.1056/NEJMsr1601330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Munch T, Dufka FL, Greene K, et al. RReACT goes global: Perils and pitfalls of constructing a global open-access database of registered analgesic clinical trials and trial results. Pain 2014;155:1313–7. 10.1016/j.pain.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Valkenhoef G, Loane RF, Zarin DA. Previously unidentified duplicate registrations of clinical trials: an exploratory analysis of registry data worldwide. Syst Rev 2016;5:1–9. 10.1186/s13643-016-0283-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Raftery J, Fairbank E, Douet L, et al. Registration of noncommercial randomised clinical trials: the feasibility of using trial registries to monitor the number of trials. Trials 2012;13:1–6. 10.1186/1745-6215-13-140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zarin DA, Tse T, Sheehan J. The proposed rule for U.S. clinical trial registration and results submission. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2015;372:174–80. 10.1056/NEJMsr1414226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sekeres M, Gold JL, Chan AW, et al. Poor reporting of scientific leadership information in clinical trial registers. PLoS One 2008;3:e1610 10.1371/journal.pone.0001610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wühl E, Trivelli A, Picca S, et al. Strict blood-pressure control and progression of renal failure in children. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1639–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023394supp001.pdf (800.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-023394supp002.xlsx (67.1KB, xlsx)